7. Controlling pollution and managing wastes

Nutrients are defined as substances that promote the growth of aquatic vegetation. The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999) provides authority to regulate nutrients in cleaning products and water conditioners that degrade or have a negative impact on an aquatic ecosystem.

In its response to the Parliamentary Standing Committee's review of CEPA 1988, the Government of Canada's five natural resource departments committed to undertake a comprehensive study on nutrients in Canada's environment. The resulting science assessment, Nutrients and Their Impacts on the Canadian Environment, together with its companion report, Nutrients in the Canadian Environment - Reporting on the State of Canada's Environment, and the associated proceedings of the national nutrient workshop, were completed in 2000-01. The report indicates that environmental problems caused by excessive nutrients are less severe in Canada than in many countries. This is in part due to protective measures implemented by governments in the last 30 years. Nonetheless, while successes have been realized, environmental and human health problems related to nutrients are evident across Canada. (The reports were published in July 2001.)

The department also continued research on nutrients in 2000-01:

- Studies by the National Wildlife Research Centre have demonstrated that measuring stable nitrogen isotopes in mallard and other waterfowl feathers has the potential to be used to identify sources of excess nitrogen fertilizers and nitrogenous wastes (e.g., intensive livestock operations). This study is part of a longer-term research project to investigate use of stable isotopes as tools to identify natal origins of migratory birds and sources of environmental contamination.

- A comprehensive assessment of the effects of nutrients from human activities on the Canadian environment conducted by an interdepartmental working group under the leadership of the National Water Research Institute has been completed and is now available to the public. The review paints a clear picture of the extent of the damage to the Canadian environment from nutrients derived from human activities. It shows that there is accelerated eutrophication (excessive algal growth as a result of the abundance of nutrients, resulting in reduction in available oxygen for animal life) of certain rivers, lakes, and wetlands in Canada, resulting in loss of habitat, changes in biodiversity, and loss of recreational potential. In addition, exceedances of drinking water guidelines for nitrate in groundwater are more frequent across Canada.

- The National Water Research Institute is working with water quality managers and researchers in provincial departments, conservation authorities, and universities to gather data on nutrient concentrations, aquatic plant biomass, and related parameters such as water clarity for Ontario streams and rivers. These data will be analyzed and manipulated to propose nutrient guidelines to protect water quality. A similar project is in progress for rivers in western and northern Canada.

This Division provides new authorities to issue non-regulatory objectives, guidelines, and codes of practice to help implement the National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities. These provisions are intended to supplement authority that exists in other federal, provincial, territorial, and aboriginal government laws.

The major threats to the health, productivity, and biodiversity of the marine environment result from human activities on land in coastal areas and further inland. It is widely accepted that some 80% of the pollution in the oceans originates from land-based activities. As part of an international initiative to address major land-based threats in an integrated approach, Canada and 108 other nations adopted the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities in November 1995. It requires participating countries to develop national programs of action.

Canada was the first country to respond to this call for action. In June 2000, Canada released its National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities. Developed by a federal/provincial/territorial committee over the course of four years, Canada's National Programme of Action reflects shared responsibilities and input from two extensive rounds of public consultations.

To help build the capacity of Canadians and to promote Canada's National Programme of Action (it is better known internationally than it is in Canada), an Information Clearinghouse was launched in March 2001. This online tool provides comprehensive resources on marine and coastal activities, expertise relevant to the Programme, and links to community groups, scientists, and government. The clearinghouse also serves as a focal point for the Secretariat, providing news and distributing documents to the public.

In October 2000, Canada agreed to host the first Intergovernmental Review Meeting for the Global Programme of Action, to be held in Montreal in November 2001. This meeting will be a major international event to assess worldwide progress since 1995 on implementing the Programme and will report to the World Summit on Sustainable Development to be held in Johannesburg, South Africa, in September 2002. More than 100 countries are expected to attend, along with numerous intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. Canada is preparing a Country Report on progress under the National Programme of Action for presentation at the meeting. The Intergovernmental Review Meeting was held November 26-30, 2001.

These provisions prohibit the disposal (and incineration) of wastes in oceans within Canadian jurisdiction, and by Canadian ships in international waters, unless the disposal is done under a permit issued by the Minister. A permit for ocean disposal will be approved only if it is the environmentally preferable and practical option.

CEPA 1999 introduces changes that reflect new international approaches to controlling disposal at sea:

- a minimum waiting period of 30 days from a permit's publication or amendment in the Canada Gazette before disposal operations may begin, to allow anyone with a concern to file a notice of objection unless the permit is necessary to avert an emergency;

- a set of substances (only those listed in Schedule 5 of the act) that may be considered for disposal at sea;

- a formal assessment framework (Schedule 6), which is based on the precautionary principle, for permit applications;

- a prohibition on exporting any substance for disposal at sea; and

- a legal obligation for Environment Canada to monitor disposal sites.

Disposal at sea

Disposal at sea may be considered only for the following substances:

- Dredged material.

- Fish waste and other organic matter resulting from industrial fish processing operations.

- Ships, aircraft, platforms, or other structures from which all material that can create floating debris or other marine pollution has been removed to the maximum extent possible.

- Inert, inorganic geological matter.

- Uncontaminated organic matter of natural origin.

- Bulky substances that are primarily composed of iron, steel, concrete, or other similar matter that does not have a significant adverse effect, other than a physical effect, on the sea or the seabed.

To ensure consistencies with CEPA 1999, Environment Canada published two proposed regulations on February 17, 2001, to replace the Ocean Dumping Regulations, 1988. The Disposal at Sea Regulations comply with the new provisions in CEPA 1999 by codifying existing national policy. The Regulations Respecting Applications for Permits for Disposal at Sea set out the permit application form. The new regulations include the requirements from the previous regulations and now formally include existing policies, which have been in place since 1994. (Both regulations came into force on August 15, 2001.)

CEPA 1999 prohibits the disposal and incineration of wastes in oceans within Canadian jurisdiction, and by Canadian ships in international waters, unless the disposal is done under a permit issued by the Minister. CEPA 1999 takes a precautionary approach by listing, in Schedule 5, the non-hazardous wastes (e.g., dredged material, fish waste) for which a permit can be issued. Everything else is prohibited. A permit for ocean disposal will be approved only if it is the environmentally preferable and practical option, which is assessed according to an environmental assessment framework set out in Section 6 of the act.

In 2000-01, 113 permits were issued in Canada for the disposal of 2.46 million tonnes of wastes and other matter. Most of this was dredged material that was removed from harbours and waterways to keep them safe for navigation. Overall, the quantities permitted in 2000-01 are lower than last year and almost two-thirds lower than the previous 10 years. The number of permits issued has remained relatively stable since 1995. Historically, the quantity permitted has been greater than the actual quantity disposed of at sea (often by 30-50%); however, with the monitoring fee for dredged material and geological matter in place since 1999, the quantities permitted now more closely reflect the actual quantities disposed of.

| Type of material | Permits issued | % of total permits | Quantity permitted (tonnes) |

% of total quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dredged material | 58 | 51 | 2 064 800 | 84 |

| Geological matter | 2 | 2 | 325 000 | 13 |

| Fisheries waste | 52 | 46 | 72 500 | 3 |

| Vessels | 1 | 1 | 192 | <1 |

| Total | 113 | 100 | 2 462 492 | 100 |

| Type of material | Atlantic | Quebec | Pacific and Yukon | Prairie and Northern | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permits issued | Quantity permitted (tonnes) |

Permits issued | Quantity permitted (tonnes) |

Permits issued | Quantity permitted (tonnes) |

Permits issued | Quantity permitted (tonnes) |

|

| Dredged material | 18 | 607 900 | 16 | 117 000 | 23 | 1 112 400 | 1 | 227 500 |

| Geological matter | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 325 000 | 0 | 0 |

| Fisheries waste | 49 | 70 100 | 3 | 2 400 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vessels | 1 | 192 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >0 |

| Total | 68 | 678 192 | 19 | 119 400 | 25 | 1 437 400 | 1 | 227 500 |

CEPA 1999 provisions for a 30-day waiting period caught some permit applicants unprepared, and some acceptable wastes needed to be disposed of before the 30 days had passed to avert an unacceptable risk to the environment or human health. While no formal waiting period was specified under CEPA 1988, in practice, 10 days were usually allowed after a permit's publication before it came into effect. Of the 113 total permits issued, seven were emergency permits issued for dredged material, fisheries wastes, and a vessel. Each emergency permit required consultation with the International Maritime Organization.

Under CEPA 1988, routine inspections and investigations were normally carried out to ensure compliance with permits. Monitoring guidelines for dredged material, developed in 1998, are now used in routine disposal site monitoring. With the strengthened requirements in CEPA 1999, the Minister is also mandated to monitor sites that are used for disposal. Disposal site monitoring is used to verify that permit conditions are met and that assumptions made during the permit review and site selection process were correct and sufficient to protect the environment. The new cost recovery approach to monitoring activities (fees of $470 per 1000 cubic metres for dredged material and inert geological matter) enables regional staff to consult with the regulated community.

Each year, monitoring is conducted at representative sites throughout Canada. Monitoring guidelines for dredged material, developed in 1998, are now used in routine disposal site monitoring. With the introduction of the user fee, regional staff are able to consult with the regulated community on monitoring activities. In 2000, field monitoring was conducted at three sites:

- An examination of the seafloor by sonar was carried out at the Black Point disposal site in the Bay of Fundy, which receives dredged material from the Port of Saint John.

- Sediment sampling and chemical analysis were carried out at a disposal site that receives material from a small fishing harbour in Sainte-Thérèse-de-Gaspé.

- A video study of the seafloor and sediment sampling for chemical analysis were carried out at the Point Grey disposal site in the Strait of Georgia, which receives dredged material from the Port of Vancouver.

Further details can be found in the Compendium of Monitoring Activities at Ocean Disposal Sites, which is sent to permittees and submitted to the International Maritime Organization annually.

With CEPA's stronger controls on disposal at sea, Canada was able to sign on to the 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping Wastes and Other Matter, also known as the London Dumping Convention. In May 2000, Canada became the 10th country consenting to be bound by the Protocol, which is expected to come into force in 2002 once 26 countries have consented to it. The Protocol contains stronger international commitments, such as an assessment framework for wastes and other matter (now found in Schedule 6 of CEPA 1999), a ban on incineration at sea, and a ban on the export of waste for disposal at sea.

CEPA 1999 provides the government more flexibility to control fuel qualities. It provides for a performance-based approach to fuel standards and allows for a range of fuel characteristics to be set to address emissions.

Other provisions in CEPA 1999 provide the authority to make regulations distinguishing between different sources of fuels, regarding the place or time of use of the fuel, or where a fuel might affect the operation of emissions control equipment. There are also provisions for a "national fuels mark" that may be used, after authorization by the Minister, to demonstrate that a fuel conforms to specific requirements provided for by regulations.

On February 17, 2001, following broad consultations, the Minister of the Environment published the Federal Agenda on Cleaner Vehicles, Engines and Fuels. It contains several measures aimed at protecting the environment and health of Canadians by improving the quality of diesel fuel. Actions include:

- reducing the level of sulphur by 2006 in all on-road diesel fuel;

- establishing a new limit for sulphur in off-road diesel fuel; and

- establishing a comprehensive database on diesel fuel quality in order to monitor fuel quality.

The plan also details two measures regarding gasoline:

- a study of the effects of gasoline composition on emissions of toxic substances from vehicles; and

- using CEPA 1999 information-gathering authorities to collect information on the use and release into the environment of the gasoline additive methyl tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE).

The plan also proposes to develop measures to reduce the level of sulphur in light fuel oils used for heating homes and for heavy fuel oils used by industrial facilities.

High sulphur levels in fuels increase emissions of a number of pollutants from vehicles and contribute significantly to air pollution. Sulphur occurs naturally in crude oil. Its level in fuel products depends on the source of the crude oil and on the extent to which it is removed during the refining process.

The 1999 Sulphur in Liquid Fuels report (PDF 192 KB), based on information provided under the Fuels Information Regulations, No. 1, was released in April 2000. These reports are updated annually. The regulations, adopted in 1977, require reporting of information on additives and sulphur levels of liquid fuels. The report highlights the fact that heavy fuel oil, even though it constitutes only 8.7% by volume of liquid fuels, contains 73.3% of the total sulphur mass. The Atlantic provinces, Quebec, and Ontario account for 89.9% of the total mass of sulphur present in fuel in Canada.

As part of the fuels agenda, Environment Canada is developing new regulations to reduce sulphur in on-road diesel fuel to 15 parts per million in 2006 from today's limit of 500 parts per million, in alignment with fuel requirements recently passed by the United States. During 2000, Environment Canada initiated consultations on the details of draft regulations that are expected to be proposed in winter 2002.

Reducing the level of Sulphur in Canadian On-road Diesel Fuel (PDF, 89 KB)

Vehicle emissions are the largest contributor to Canada's air pollution problem. The strengthened provisions in CEPA 1999 include the authority, formerly in the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, to set emission standards for engines in new on-road vehicles. It also includes new authorities to set emission standards for new off-road vehicles and other engines such as those found in lawnmowers, construction equipment, and hand-held equipment. These sections establish a "national emissions mark" that could be used to require adherence to prescribed standards. Companies would not be permitted to transport within Canada any prescribed vehicles, engines, or equipment that do not have a national emissions mark.

On February 17, 2001, following broad consultations, the Minister of the Environment published the Federal Agenda on Cleaner Vehicles, Engines and Fuels. This 10-year action plan, which will be supported by regulations, guidelines, and studies over the coming years, includes measures for on-road vehicles and engines, in-use vehicles, and off-road vehicles and engines.

The agenda sets out a plan to develop new Canadian emission standards for vehicles and engines, aligned with those of the United States. Regulations under CEPA 1999 and emissions control programs will be developed to reduce emissions from:

- cars, vans, pick-up trucks, and sports utility vehicles, to be phased in beginning with the 2004 model year;

- large trucks and buses, to be phased in beginning with the 2004 model year;

- off-road diesel vehicles and engines, such as those used in the agricultural sector and by the construction industry;

- gasoline utility engines, such as those used in snowblowers, lawnmowers, and chain saws; and

- outboard marine engines and personal watercraft.

Four Memoranda of Understanding were signed in 1999 and 2000 with engine manufacturers and associations. These agreements, which address handheld engines, construction and agricultural equipment, spark-ignition outboard engines, and personal watercraft, represent voluntary commitments by manufacturers to introduce cleaner off-road engines into the Canadian marketplace starting in 2000-01, in advance of future regulatory requirements.

Testing and research continued in 2000-01 to support action on vehicles and fuels:

- To have the capability and capacity to conduct enhanced compliance/ confirmatory exhaust emissions testing, the Environmental Technology Centre initiated an extensive four-year upgrade program involving new test equipment and improved test cell environmental condition controls to measure emissions more accurately from ultra-low-emission vehicles, utility engines, medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, and large outboard marine engines.

- The Environmental Technology Centre conducted an emissions verification test program under the CEPA 1999 Mobile Source Emissions Regulations for 1999 and 2000 model year light-duty vehicles and for latest-model utility engines and outboard marine engines. The program included work on 10 vehicles, 30 utility engines, and seven outboard marine engines. Fuel consumption was also measured and provided to Transport Canada for the National Fuel Consumption Program.

These sections contain authority to address Canadian sources of pollution that contribute to air pollution in another country or violate an international agreement binding on Canada. These sections apply to the release of substances that may not have been determined to be toxic under Part 5, but nevertheless contribute to international air pollution. Before using the powers in this Division, the Minister must first consult with the provincial, territorial, or aboriginal government responsible for the area in which the pollution source is located to determine if that government is willing or able to address the problem.

The negotiations were finalized on the Global Convention on POPs under the United Nations Environment Programme in December 2000. The Convention was signed and ratified by over 90 countries, including Canada, on May 23, 2001, at the United Nations meeting in Stockholm, Sweden. Canada was the first country to ratify the agreement. The convention sets out control measures covering the production, import, export, disposal, and use of 12 POPs. It calls on the 122 countries involved in the final negotiations to promote the best available technologies and practices for replacing existing uses of POPs while preventing the development of new POPs. Countries are to draw up national implementation strategies and develop action plans for carrying out their commitments. While most POPs have been banned or restricted in Canada for years, they are transported from foreign sources through the atmosphere into Canada. All of these POPs are targeted for virtual elimination in Canada.

On December 7, 2000, Canada signed an agreement to reduce transboundary smog with the United States through an Ozone Annex under the 1991 Canada-U.S. Air Quality Agreement. Actions under the Annex will reduce air pollution flows from the United States to improve air quality and the health of Canadians living in downwind areas in eastern Canada. The Annex also commits to reducing flows of pollution from areas in Ontario and Quebec into the United States. The Annex commits to actions in these major areas: transportation (new standards for emissions from vehicles and engines and the fuels that power them), industrial sectors (reductions in nitrogen oxide emissions from the electricity sector and volatile organic compounds from industrial sources and products, including paint coatings, degreasing agents, and solvents), monitoring (track progress on commitments made by both countries), and reporting (expand the NPRI).

The "Dirty Dozen"

The Stockholm Convention targets an initial list of 12 POPs, known as the "dirty dozen," in three broad categories:

Pesticides - 1,1,1-trichoro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethane (DDT), chlordane, toxaphene, mirex, aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor

Industrial chemicals - polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), hexachlorobenzene

By-products and contaminants - dioxins and furans

To meet its commitments under the Agreement, the federal government announced new funding of $120.2 million on February 19, 2001. This plan for action focuses on a 10-year regulatory agenda for cleaner vehicles and fuels, initial measures to reduce smog-causing emissions from industrial sectors, improvements to the cross-country network of pollutant monitoring stations, and expansion of the public reporting by industry on pollutant releases.

International Airshed Planning for the Georgia Basin area was initiated in anticipation of a revised Ozone Annex in 2004 and a Particulate Annex in 2005. A meeting of senior officials of Canadian and U.S. federal, provincial, state, regional, and local authorities and First Nations and Tribes took place in Bellingham, Washington, in February 2001. Participants agreed to initiate the process with a common Statement of Intent to protect air quality in the Puget Sound and Georgia Basin Region and to explore a list of early action items, including characterizing the common airshed, identifying issues and solutions, establishing a clearinghouse of best practices, and creating a clean vehicles and fuels corridor.

Reducing smog

Canadian actions under the Ozone Annex are estimated to reduce annual nitrogen oxide emissions in the Canadian transboundary region by 44% in 2010, and annual volatile organic compounds emissions by 36% in 2010.The U.S. commitments will reduce annual nitrogen oxide emissions in the transboundary region by 36% in 2010, and annual volatile organic compounds emissions by 38%in 2010.

Canada has made commitments under the 1991 Canada-U.S. Air Quality Agreement to address transboundary air pollution, including sulphur dioxide emissions. Canada's sulphur emissions are all below the applicable caps of the Air Quality Agreement: an annual cap of 2.3 million tonnes for eastern Canada through December 2000, and a permanent cap of 3.2 million tonnes by 2000. In the Air Quality Agreement 2000 Progress Report, Canada reported that the total Canadian sulphur dioxide emissions were less than 2.7 tonnes. Forecasts from the 1999 Annual Progress Report on the Canada-wide Acid Rain Strategy for Post-2000 indicate that emissions will remain below all applicable caps well into the future. Furthermore, through the Canada-wide Acid Rain Strategy for Post-2000, Environment Canada, in partnership with the provinces and territories, continues to address the remaining acid rain problem in eastern Canada to ensure that new acid rain problems do not occur elsewhere in Canada and to ensure that Canada meets its international commitments on acid rain.

CEPA 1999 builds on the federal government's authority to enact regulations governing the export and import of hazardous waste (including hazardous recyclable materials) and includes new authorities to:

- introduce regulations on the import and export of prescribed non-hazardous waste;

- require exporters of hazardous wastes destined for final disposal to submit reduction plans; and

- develop and implement more stringent criteria to assess the environmentally sound management of transboundary wastes and to refuse permits for import or export if criteria are not met.

It also transfers the authority to control the interprovincial/territorial movements of hazardous waste and hazardous recyclable materials from the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act to CEPA 1999.

CEPA 1999 contains provisions that require the Minister to publish notification information (type of waste, company name, and country of origin or destination) for exports, imports, and transits of hazardous waste and hazardous recyclable material.

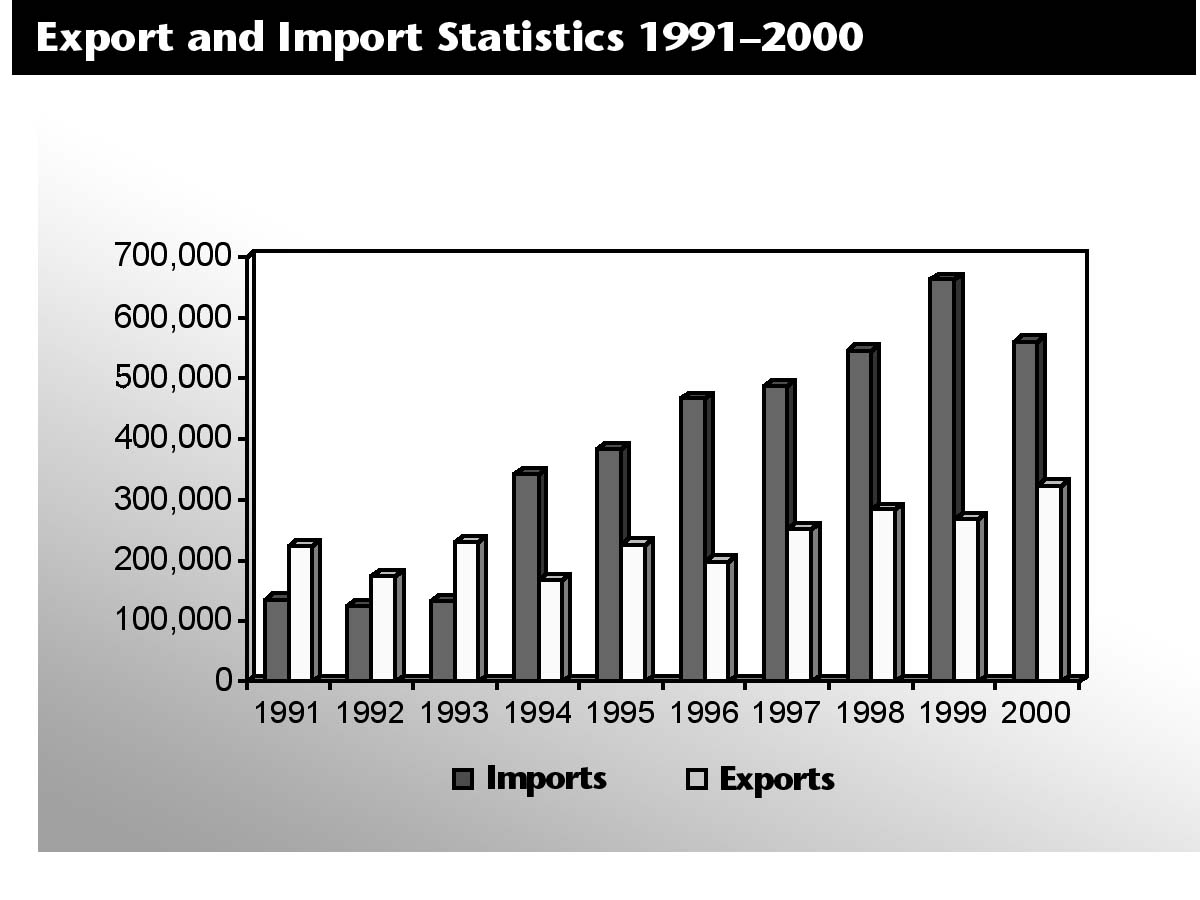

Export and import statistics 1991-2000

The Export and Import of Hazardous Wastes Regulations, which have been in place since 1992, provide a way of tracking the movement of hazardous wastes and hazardous recyclable material into and out of Canada, including transit shipments passing through Canadian territory. These regulations allow Canada to implement its obligations under the Basel Convention on the Control of the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Council Decision on Recycling, and the Canada-U.S. Agreement on the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Waste.

During the 2000 calendar year, 8000 notices were processed for proposed imports, exports, and transits of hazardous wastes and hazardous recyclable materials. During the same period, 47 000 manifests were processed for tracking shipments approved under these notices.

The 2000 Canadian statistics on transboundary movement of hazardous waste show an overall decrease from previous years. In 2000, total imports of hazardous wastes were 560 000 tonnes, down 15% from 663 000 tonnes in 1999. There was a 29% reduction in overall imports for disposal and a 32% reduction in imports destined for landfilling from the 1999 calendar year. Information on imports and exports of hazardous waste is published twice a year in the RESILOG newsletter.

In response to the strengthened authorities under CEPA 1999 to control hazardous wastes, Environment Canada is drafting major amendments to two current regulations:

- Amendments to the Export and Import of Hazardous Wastes Regulations will harmonize definitions and controls with recent domestic and international changes as well as improve regulatory efficiency. Preliminary consultations were held in February and March 2001, with another round planned for early 2002. Proposed regulations are expected in 2002.

- Amendments to the PCB Waste Export Regulations will include parallel controls for the import of PCB wastes and some requirements for low-level PCB wastes. Stakeholder consultations were held in January and February 2001, with proposed regulations expected in 2002.

The enhanced provisions of CEPA 1999 are also being used to develop new regulations concerning the import and export of wastes and recyclable materials:

- Preliminary consultations were held across Canada in September and October 2000 on new regulations governing the interprovincial/territorial movement of hazardous wastes and hazardous recyclable materials. These regulations will ensure that wastes are transported to and received only at authorized facilities for final disposal and recycling operations. Draft regulations are expected in 2002.

- The department consulted with stakeholders in the winter of 2000 and March 2001 on options for regulating the export and import of non-hazardous wastes destined for disposal. These regulations will permit Canada to meet its international commitments under the Basel Convention and implement CEPA 1999 authorities for reduction plans and criteria for environmentally sound management. Draft regulations are expected in 2002.

The mechanism for implementing this new authority was discussed as part of the stakeholder consultations in February and March 2001 on amendments to the Export and Import of Hazardous Wastes Regulations and for regulations on the import and export of the prescribed non-hazardous wastes. The requirements for reduction phase-out plans will be implemented in the 2003 amendment to the Export and Import of Hazardous Wastes Regulations.

In July 2000, the Minister of the Environment called on provinces and territories to help strengthen the standards for all facilities that accept hazardous waste. In the fall of 2000, an action plan to establish a national regime for environmentally sound management was developed in cooperation with the provinces and territories under the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME). A priority goal is to establish new landfill guidelines. An accelerated program was also initiated with Ontario and Quebec, since most major hazardous waste landfills are located in these provinces.

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal is a global convention under the United Nations Environment Programme. Canada ratified the Convention in 1992. The primary goals of the Basel Convention are to control the transboundary movement of hazardous and other wastes and hazardous recyclable materials and to ensure that they are managed in an environmentally sound manner.

In 2000-01, Canada participated on the Basel Bureau, which oversees the direction of the Convention and addresses financial issues between the parties of the Convention. Canada also continued its tradition of active participation in the Technical and Legal Working Groups. Current issues within the Convention include furthering the work on environmentally sound management, developing a mechanism for monitoring parties' compliance with the Convention, and establishing criteria for the reduction and elimination procedures under the related POPs Convention.