Screening assessment certain organic flame retardants substance grouping benzene, 1,1’-(1,2-ethanediyl)bis [2,3,4,5,6-pentabromo- decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE)

Official title: Screening assessment certain organic flame retardants substance grouping benzene, 1,1’-(1,2-ethanediyl)bis [2,3,4,5,6-pentabromo- Decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE)

Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number 84852-53-9

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Health Canada

May 2019

Cat. No.: En14-370/2019E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-30243-0

Synopsis

Pursuant to section 68 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health have conducted a screening assessment of benzene, 1,1’-(1,2-ethanediyl)bis[2,3,4,5,6-pentabromo-. This substance, commonly known as decabromodiphenyl ethane, or DBDPE, is identified by the Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number (CAS RN) 84852-53-9. This substance is included in the Certain Organic Flame Retardants (OFR) Substance Grouping under Canada’s Chemicals Management Plan, which includes ten organic substances having a similar function: the application to materials to slow the ignition and spread of fire. DBDPE was identified as a priority for assessment on the basis of ecological concerns identified through the CEPA New Substances program. While this substance is not on the Domestic Substances List (DSL), it has been in commerce in Canada since the transitional period between the establishment of the DSL and the coming into force of the New Substances Notification Regulations (Chemicals and Polymers) (January 1, 1987 and July 1, 1994).

On the basis of information gathered from a survey conducted under section 71 of CEPA , as well as data from the New Substances program, DBDPE imports to Canada ranged from 1 000 000 to 10 000 000 kg in 2011, including DBDPE in neat form, in formulations, and in commercial products or products available to consumers. DBDPE is used in Canada as an additive flame retardant in many applications, such as plastic and rubber materials, electrical and electronic equipment, adhesives and sealants.

DBDPE does not occur naturally in the environment. Globally, sources of exposure to DBDPE are primarily from waste streams or effluents of manufacturing and processing plants using DBDPE as an additive flame retardant, but also from releases from products available to consumers or commercial products in service. DBDPE has become commercially important since the early 1990s as a flame retardant in its own right, and more recently as an alternative for the structurally similar flame retardant decabromodiphenyl ether (decaBDE).

Generally, DBDPE is characterized by very low water solubility, low vapour pressure, and a very high organic carbon-water partition coefficient and octanol-water partition coefficient. A close structural analogue, decaBDE, was considered for read-across of certain physical-chemical properties, as well as to predict substance behaviour in the environment. DBDPE has been measured in the Canadian environment, as well as internationally, with highest concentrations near urban and/or industrial areas. When released to the environment, DBDPE is expected to predominantly reside in soil and/or sediment. Particle-bound transport may contribute to long range transport and deposition in remote areas.

Experimental and modelled data indicate that aerobic biodegradation (including in the presence of plants) and anaerobic biodegradation of DBDPE is limited and that DBDPE is expected to be persistent in water, soil, and sediment. Limited DBDPE transformation was also identified in high temperature applications and recycling. Studies report that photodegradation of DBDPE may proceed quickly in solvents, but more slowly in other matrices/substrates, and modelled predictions for atmospheric degradation suggest DBDPE is persistent in air (gas phase half-life greater than 4 days). Although degradation of DBDPE is expected to be slow or limited, there is uncertainty with respect to ultimate transformation products in the environment. Potential DBDPE transformation products were evaluated based on predictions from photodegradation studies, biodegradation/metabolism modelling and considering the analogue decaBDE. DBDPE debromination was expected to continue from nona- and octa-bromo diphenyl ethanes (BDPEs) through the formation of hepta-, hexa-, and pentaBDPEs (similar to decaBDE), or lead to a hydroxylated nonaBDPE pathway. As there are no experimental data, QSAR modelling was conducted to assess the characteristics of these potential DBDPE transformation products. Preliminary modelling indicates DBDPE transformation products can be considered analogues to lower brominated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), and would be persistent, would be bioaccumulative in some cases, and potentially highly toxic to aquatic organisms. The Ecological Screening Assessment on PBDEs (June 2006) concluded that lower brominated PBDEs, namely tetraBDE, pentaBDE and hexaBDE, satisfy the criteria outlined in the Persistence and Bioaccumulation Regulations of CEPA.

There is a limited amount of empirical data on DBDPE accumulation in biota, but these data combined with DBDPE physical and chemical properties indicate a lower potential for bioaccumulation in organisms.

Based on soil chronic toxicity testing, DBDPE has the potential to cause reproductive effects at high concentrations to earthworms as well as effects on plant survival and growth. No effects up to the highest tested dose (5000 mg/kg) were observed for sediment organisms in chronic toxicity tests. A water (pelagic) critical toxicity value (CTV) was not determined for DBDPE in this assessment, based on uncertain aquatic test results. It is considered that sediment and soils are more relevant for assessing exposure to DBDPE due to its high hydrophobicity and expected fate in the environment.

It is expected that DBDPE may be released to the Canadian environment as a result of industrial processing activities. Additive use of DBDPE in products suggests diffuse emissions may occur from commercial products or products available to consumers and, although there are uncertainties, the rate is assumed to be low in comparison to industrial point sources during incorporation of the substance into products. Industrial scenarios (which considered available site information), with DBDPE release to water and predicted partitioning to sediment and releases to soil, were used to estimate exposure. Risk quotient analyses, integrating conservative estimates of exposure with toxicity information, were performed for the sediment and terrestrial compartments (soil and wildlife). These analyses showed that current risks posed by the DBDPE, itself, are low.

A risk quotient analysis for DBDPE transformation products was not conducted given the lack of information on transformation products quantity in Canada. However, the findings of this analysis are consistent with the concerns expressed in the 2010 Ecological State of the Science Report on Decabromodiphenyl Ether in that DBDPE is expected to transform to lower brominated products in a manner similar to decaBDE. Transformation products, which are predicted to be harmful to the environment, are expected to represent a minor fraction relative to parent DBDPE; however, they are similar to predicted/measured fractions of analogue decaBDE debromination products, and if DBDPE levels in the environment continue to increase (e.g., owing to its use as a replacement flame retardant), the pool of potential brominated transformation products could become important.

Considering all available lines of evidence presented in this screening assessment for DBDPE and the potential for persistence, bioaccumulation and inherent toxicity of its transformation products, there is risk of harm to the environment from DBDPE. It is concluded that DBDPE meets the criteria under paragraph 64(a) of CEPA as it is entering or may enter the environment in a quantity or concentration or under conditions that have or may have an immediate or long-term harmful effect on the environment or its biological diversity. However, it is concluded that DBDPE does not meet the criteria under paragraph 64(b) of CEPA as it is not entering the environment in a quantity or concentration or under conditions that constitute or may constitute a danger to the environment on which life depends.

No classifications of the health effects of DBDPE by national or international regulatory agencies were identified. No chronic or carcinogenicity studies using DBDPE were identified. On the basis of the available information regarding genotoxicity, DBDPE is not considered genotoxic. No adverse effects were observed in sub-chronic animal studies. In two separate developmental toxicity studies, no treatment-related maternal or developmental effects were observed in experimental animals exposed to DBDPE via the oral route. Limited biomonitoring data in humans are available.

The highest doses tested in experimental animal studies, with no treatment related effects, are six to seven orders of magnitude higher than the estimates of exposure to DBDPE from environmental media or products available to consumers for the Canadian general population. This margin is considered adequate to account for uncertainties in the health effects and exposure databases. Based on this, it is concluded that DBDPE does not meet the criteria under paragraph 64(c) of CEPA.

Overall conclusion

It is concluded that DBDPE meets one or more of the criteria set out in section 64 of CEPA.

It has also been determined that DBDPE meets the persistence criteria, but not the bioaccumulation criteria as set out in the Persistence and Bioaccumulation Regulations of CEPA. However, DBDPE may contribute to the formation of persistent, bioaccumulative, and inherently toxic transformation products, such as lower brominated BDPEs, in the environment.

1. Introduction

Pursuant to sections 68 or 74 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) (Canada 1999), the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Health conduct screening assessments on one of ten substances, referred to collectively under the Chemicals Management Plan as Organic Flame Retardant Substance Group, to determine whether this one substance present or may present a risk to the environment or to human health.

The Substance Groupings Initiative is a key element of the Government of Canada’s Chemicals Management Plan (CMP). The Organic Flame Retardant (OFR) Substance Grouping consists of ten substances that were identified as priorities for assessment, as they met the categorization criteria under section 73 of CEPA, or were considered as a priority on the basis of ecological or health concerns (Environment Canada and Health Canada 2007). All of these substances have a similar function: the application to materials to slow the ignition and spread of fire. These substances are potential alternatives for other flame retardants which are presently subject to regulatory controls or phase-out in Canada and/or globally. This screening assessment focuses on the substance benzene, 1,1’-(1,2-ethanediyl)bis[2,3,4,5,6-pentabromo-, or decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE) (CAS RN 84852-53-9).

As DBDPE is not present on the Domestic Substances List (DSL), it is subject to the New Substances Notifications Regulations (Chemicals and Polymers) pursuant to CEPA (Canada 2005). Following New Substances ecological and human health risk assessments, the evaluation indicated ecological concerns and this substance was suspected of being “CEPA toxic.” DBDPE has been in commerce in Canada since the transitional period between the establishment of the DSL and the coming into force of the New Substance Notification Regulations (between January 1, 1987 and July 1, 1994). Risk management measures (i.e., Ministerial Conditions) have been imposed on New Substance notifiers to mitigate potential risks to the environment.

This screening assessment includes consideration of information on chemical properties, environmental fate, hazards, uses and exposure, as well as additional information submitted by stakeholders. Relevant data were identified up to January 2017 for the ecological assessment and the human health assessment. Targeted information was added up to April 2019 for the ecological component of this assessment based on a stakeholder submission. Empirical data from key studies, analogue data, as well as some results from models were used to reach proposed conclusions. When available and relevant, information presented in assessments from other jurisdictions was considered.

This screening assessment was prepared by staff in the CEPA Risk Assessment Program at Health Canada and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and incorporates input from other programs within these departments. The ecological and human health portions of this assessment have undergone external written peer review and/or consultation. Comments on the technical portions relevant to the environment were received from Jon Arnot (Arnot Research and Consulting), John Biesemier (Chemtura), Adrian Covaci (University of Antwerp), Miriam Diamond (University of Toronto), and Marcia Hardy (Albermarle). Comments on the technical portions relevant to human health were received from Michael Jayjock of the LifeLine group, Paul Rumsby of the U.S. National Centre for Environmental Toxicology, and Pam William of E Risk Sciences. Additionally, the draft of this screening assessment was subjected to a 60 day public comment period. While external comments were taken into consideration, the final content and outcome of the screening assessment remain the responsibility of Health Canada and ECCC.

This screening assessment focuses on information critical to determining whether substances meet the criteria as set out in section 64 of CEPA by examining scientific information and incorporating a weight of evidence approach and precautionFootnote 1 . This screening assessment presents the critical information and considerations on which the conclusion is based.

2. Substance identity

Benzene, 1,1’-(1,2-ethanediyl)bis[2,3,4,5,6-pentabromo- or decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE) is an organic flame retardant, grouped with the OFRs under the Substance Grouping Initiative of the CMP. The structural identity of this substance is presented in Table 2-1. Other names for the substance are presented in Appendix A (Table A-1). For this assessment, decabromodiphenyl ethane will be referred to as DBDPE.

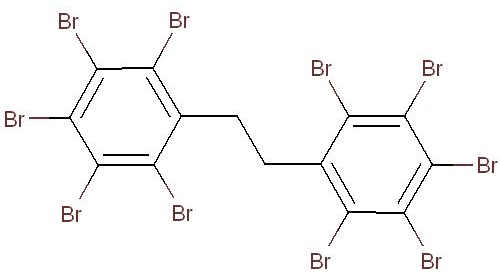

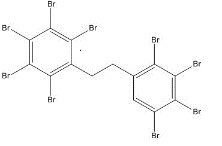

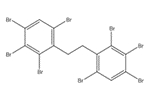

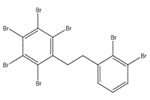

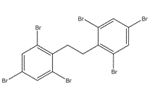

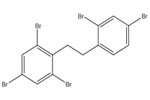

| CAS RN | Chemical structure | Molecular mass (g/mol) | Chemical formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 84852-53-9 |  |

971.23 | C14H4Br10 |

2.1 Selection of analogues and use of (Q)SAR models

Guidance on the use of a read-across approach and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships or (Q)SAR models for filling data gaps has been prepared by various organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These methods have been applied in various regulatory programs including the European Union’s (EU) Existing Substances Programme. In this assessment, data from an analogue and the results of (Q)SAR models, where appropriate, have been used to inform the ecological and human health assessments. An analogue was selected that was structurally similar and functionally similar to DBDPE (e.g. on the basis of physical-chemical properties, and fate), and that had relevant empirical data that could be used to read-across to supplement the DBDPE physical–chemical properties dataset. The applicability of (Q)SAR models was determined on a case-by-case basis. Details of the analogue data and (Q)SAR models chosen to inform the ecological and human health assessments of DBDPE are further discussed in the relevant sections of this report.

The analogue used to inform the ecological assessment is presented in Table 2-2. Decabromodiphenyl ether (decaBDE) represents a close structural analogue (e.g. Dice Similarity index= 85.1% (OECD QSAR Toolbox 2012)), and is considered appropriate for analysis of certain physical-chemical properties (e.g. octanol-water partition coefficient (log Kow), water solubility, vapour pressure) alongside measured and estimated DBDPE data (Appendix B). DecaBDE is discussed throughout the assessment in comparisons of substance behaviour with DBDPE (e.g., degradation, long range transport, bioaccumulation potential, and ecotoxicity). However, it is noted that some differences in molecular makeup, dimensions, and configurations exist between DBDPE and decaBDE that may affect the manner in which these molecules interact with their environment (Albermarle 2016, 2014 manufacturer communication to Environment Canada; unreferenced). In comparing the two substances, DBDPE’s ethane bridge between the aromatic rings (rather than the ether bridge in decaBDE) is expected to make it slightly more hydrophobic than decaBDE, and is expected to introduce more conformational flexibility in the molecule (Covaci et al. 2011). DBDPE requires a higher energy for debromination (a degradation pathway) than decaBDE as reported in Albermarle (2016).

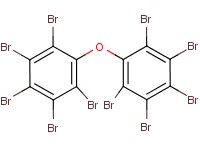

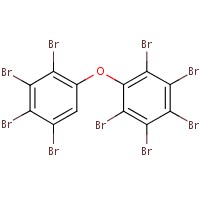

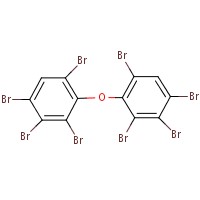

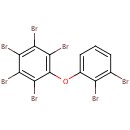

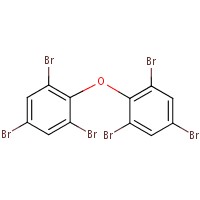

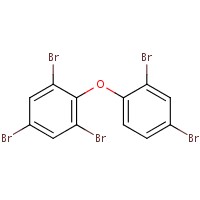

| Substance CAS RN | Substance name | Molecular weight (g/mol) | Empirical structure/molecular formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163-19-5 | decabromodiphenyl ether (decaBDE) | 959.171 |  C12Br10O C12Br10O |

3. Physical and chemical properties

Physical and chemical properties determine the overall characteristics of a substance and are used to determine the suitability of different substances for different types of applications. Such properties also play a critical role in determining the environmental fate of substances (including their potential for long-range transport), as well as their toxicity to humans and non-human organisms. A summary of experimental, modelled, and key values for the physical and chemical properties of DBDPE that are relevant to its environmental fate and ecotoxicity can be found in Table 3-1. A detailed table of physical and chemical properties of DBDPE (empirical and modelled) and a summary of analogue physical and chemical properties can be found in Appendix B.

DBDPE was considered amenable to model prediction of physical-chemical properties using (Q)SARs, as it is within the model domain of applicability (i.e., structural and/or property parameter domains are represented in the training set used for the models).

Physical-chemical properties of DBDPE were checked for internal consistency according to the Least-Squares Adjustment Procedure (LSA) (Schenker et al. 2005). Geometric mean or arithmetic mean (for logarithmic variables) values of the most reliable and independent values found from empirical data, modelling, and analogues were used to determine the inputs to the LSA (Appendix B, Table B-1, B-2). Subcooled adjusted values were input for water solubility, vapour pressure, and octanol solubility (Schenker et al. 2005). In determining internal consistency of the properties, the LSA model also produces predicted values. While experimental based estimates for log Kow, water solubility, and vapour pressure exist for DBDPE, there remains uncertainty with these values, in particular, with the experimental log Kow value of 3.55 (e.g. Stieger 2014). For the purposes of this assessment, the log Kow value 9.89, derived from the LSA method, was selected. To maintain internal consistency of physical-chemical values, the LSA method value for water solubility and vapour pressure were also considered. Final selected values are summarized in Table 3-1.

Generally, DBDPE is characterized by very low water solubility, low to very low vapour pressure, and a very high organic carbon-water partition coefficient and octanol-water partition coefficient.

| Property | Experimental | Modelled | Selected value for modellingc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical state | (off) white powder | N/A | N/A |

| Melting point (ºC) | 345 - 355 | 259.7 | 345 |

| Boiling point (ºC) | N/A- degrade before boiling | 600.9 | N/A |

| Density (kg/m3) | 868 – 3250 (packed) | N/A | N/A |

| Vapour pressure (Pa) | ~1 x 10-6a – <1 x 10-4 | 2.85 x 10-16 - 5.59 x 10-10 | 5.59 x 10-10 (liquid subcooled 8.21 x 10-7) |

| Henry’s Law constant (Pa·m3/mol) | NA | 2.59 x 10-4 – 6.71 x10-2 | 6.51 x10-3 – 6.71 x10-2 |

| Log Kow (dimensionless) | ~3.55b, 8.7a | 7.86 –13.64 | 9.89 |

| Log Koc (dimensionless) | NA | 6.38 – 8.58 | 8.58 |

| Log Koa (dimensionless) | NA | 14.45– 19.22 | 14.45 |

| Water solubility (mg/L) | <1 x 10-4a – 7.2 x 10-4 | 7.34 x 10-10 – 2.15 x 10-2 | 8.10 x10-6 (liquid subcooled: 1.19 x10-2) |

| pKa | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable. log Kow, octanol-water partition coefficient; log Koc, organic carbon-water partition coefficient; log Koa, octanol-air partition coefficient; pKa, acid dissociation constant; NA, not available.

a Read-across value from analogue decaBDE.

b Experimentally estimated log Kow value (3.55) evaluated to be highly uncertain and therefore not included in mean log Kow for LSA.

c See Appendix B, Table B-2 for detailed physical-chemical property values and references.

4. Sources

There is no reference in the published literature for the natural occurrence of DBDPE in the environment. Sources of exposure to DBDPE are anthropogenic, primarily from waste streams or effluents of manufacturing and processing plants using DBDPE as an additive flame retardant, and release from products available to consumers or commercial products to the environment.

DBDPE has become increasingly important commercially since the 1990s as a flame retardant in its own right and as a replacement for commercial DecaBDE (Kierkegaard et al. 2004, Covaci et al. 2011; EFSA 2012). North American manufacturers of decaBDE have voluntarily phased out the production, import, and sale of DecaBDE by 2012 in cooperation with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and ECCC (BSEF c.2001-2015). There also exist governmental efforts to limit the manufacture, import and use of decaBDE (Environment Canada c.2006-2013). In Canada, risk management of decaBDE is supported by concerns respecting the transformation of decaBDE to lower brominated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), which include tetra-, penta- and hexaBDEs, substances considered to be highly persistent and bioaccumulative (Environment Canada 2010, Canada c.2006-2013).

In Canada, as DBDPE is not present on the DSL, it is subject to the New Substances Notifications Regulations (Chemicals and Polymers) pursuant to CEPA. On the basis of information gathered from a survey conducted under section 71 of CEPA, and the data from New Substances notifications, the total quantity of DBDPE imported into Canada in 2011 was in the range of 1 000 000 – 10 000 000 kg, including DBDPE in some products. No DBDPE was identified as being manufactured in Canada. The total quantity of DBDPE exported out of Canada in 2011 was less than 100 000 kg (Canada 2005; ECCC 2013-2014).

Globally, manufacturing of DBDPE is known to occur in the United States (US) (Covaci et al. 2011, US EPA 2012). In the US, DBDPE is a chemical on the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Inventory, and the substance is subject to a Significant New Use Rule (SNUR). In 2012, the US production/import volume was between 22 720 000 to 45 450 000 kg (50 to 100 million pounds) (US EPA 2012). According to the US EPA 2012 Chemical Data Reporting (CDR), 5 companies were associated with DBDPE as producers or importers in the US.

No manufacturing of DBDPE has been reported to occur in Europe (Environment Agency 2007). Although the substance is listed as a Low Production Volume chemical (under 1 000 000 kg/yr) on the European Chemical Substance Information Systems (ESIS) website (searched March 2014) (ESIS 1995-2012), other sources suggest use in Europe may be higher. For example, use in Europe has been estimated at 2 500 000 kg/year with data trends suggesting increasing consumption (Environment Agency 2007), primarily in Germany (Covaci et al. 2011). A Substances in Preparations in Nordic Countries (SPIN) database (searched April 2014) indicated records of use for 2006, and 2008 through 2011 in Sweden, with substance use ranging between 5000 and 39 000 kg/year (SPIN 2006). The substance is listed as a High Production Volume chemical on the OECD Existing Chemicals Website (searched March 2014).

Recent production (e.g., 2006) of DBDPE in China has been reported to range from 11 000 000 to 12 000 000 kg per year (Shi et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009). Shi et al. (2009) suggests that China has become a significant brominated flame retardant producer during the past decades.

5. Uses

DBDPE is made by the direct bromination of diphenylethane (Weil and Levchik 2009), and marketed globally under different trade names (Appendix A, Table A-1). DBDPE is reported to be a relatively pure substance; the commercial grade is reported to be typically 96 to 98.5% (by weight) pure, with the remainder consisting largely of nonabromodiphenyl ethane congeners (1 to 3% by weight), and octabromodiphenyl ethane congeners of less than 1% by weight (Chemtura 2005; Environment Agency 2007; Albermarle 2008, 2013, 2016).

In Canada, as DBDPE is not present on the DSL, it is subject to the New Substances Notifications Regulations (Chemicals and Polymers) pursuant to CEPA (Canada 2005). Recent risk management measures (i.e., Ministerial Conditions), on the basis of the New Substances ecological risk assessments, have limited the import of the substance for use as a flame retardant component of wire and cable coatings, thermoplastic parts, thermoplastic coatings, thermoset parts and thermoset coatings, as well as placing some restrictions on its release and disposal (Canada 2004, 2011). According to submissions made under section 71 of CEPA (Canada 2013) and submissions under the New Substance Notifications Regulations, (Ministerial Conditions 13228 and 16260) (Canada 2004, 2011), DBDPE is used in Canada as a flame retardant in applications of: plastic and rubber materials such as thermoplastic or thermoset parts and coatings (for use in polymer resins and polymer plastics); electrical and electronics including appliances and wire and cable coatings for the telecommunications industry; automotive, aircraft, and transportation, adhesives and sealants, appliances; and basic organic chemical manufacturing. DBDPE was also reported to be used in the manufacture of automotive airbag textile and generally in motor vehicles (ECCC 2013-2014). It is expected that typical polymer loading rates of DBDPE are similar to those of decaBDE, i.e., 10 to 15% by weight (Environment Agency 2007).

Globally, DBDPE is used as a substitute for decaBDE, and is therefore used in similar applications, such as the manufacture of plastics (including polyester and vinyl ester resins) and rubber products, and as an additive in textiles, such as cotton and polyester (Covaci et al. 2011). The substance is also used in polymers used for electronic and electrical applications, as well as in adhesives and sealants (EFSA 2012). Manufacturer literature indicates DBDPE is suitable for use in systems where mechanical recycling is anticipated, owing to its impressive thermal stability and low blooming characteristics (i.e., additives migrating to the surface of the material over time) in finished resins (Albermarle 2007). This manufacturer also claims that DBDPE's high bromine content allows for a high level of flame retardancy at a relatively lower flame retardant loading than alternative substances, and that it may be found in electronic devices, in wire and cable applications, in buildings where electrical current is present and in a variety of transportation related applications (Albemarle 2016).

Available information from Europe has indicated that the major use of DBDPE in Europe and the United Kingdom (accounting for at least 90% of the tonnage supplied) is as an additive flame retardant for polymers. The remaining consumption is expected to be largely for textiles (Environment Agency 2007). SPIN database records of use for 2006, and 2008 through 2011 for Sweden, indicate that all DBDPE use falls in the category of manufacture of rubber and plastic products (specifically flame retardants and extinguishing agents). For Finland, records note DBDPE use for the manufacture of other transport equipment (specifically adhesives and binding agents).

Currently, DBDPE is the second highest additive brominated flame retardant (BFR) used in China with production increasing at 80% per year (Covaci et al. 2011). This is likely related to the rapid growth of its electrical and electronic industries during the past decades (Shi et al. 2009). In Japan, the use of DBDPE is likely replacing the use of DecaBDE (Watanabe and Sakai 2003, Covaci et al. 2011). The use of DBDPE increased continuously in Japan from 1993 to 2000, whereas the consumption of DecaBDE decreased over the same time period (de Wit et al. 2011).

DBDPE is not listed as an approved food additive in the Lists of Permitted Food Additives, which have been incorporated by reference into their respective Marketing Authorizations issued under the Food and Drugs Act (Health Canada [modified 2017]), nor has it been identified as being used/present in formulations of food packaging materials or incidental additives (August 2013 email from Food Directorate, Health Canada, to Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced). DBDPE is not listed in the Drug Products Database, the Therapeutic Products Directorate’s internal Non-Medicinal Ingredient Database, the Natural Health Products Ingredients Database or the Licensed Natural Health Products Database as a medicinal or non-medicinal ingredient present in final pharmaceutical products, natural health products or veterinary drugs in Canada (DPD [modified 2017]; LNHPD [modified 2016]; NHPID [modified 2017]; July 2013 email from the Therapeutic Products Directorate, Health Canada, to Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced). On the basis of the notifications submitted under the Cosmetic Regulations to Health Canada, DBDPE is not anticipated to be used in cosmetic products in Canada (June 2013 email from the Consumer Product Safety Directorate, Health Canada to the Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced).

DBDPE is not in any registered products regulated under the Pest Control Products Act (May 2012 email from Pest Management Regulatory Agency, Health Canada to the Risk Management Bureau, Health Canada; unreferenced).

With increasing regulation and phasing-out of production of the polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), it is expected that the production and usage of DBDPE will increase (Ricklund et al. 2008).

6. Releases to the environment

Anthropogenic releases to the environment depend upon various losses occurring during the manufacture, industrial use, consumer/commercial use, service life and disposal of a substance. Releases of DBDPE to the Canadian environment, owing to the substance’s use as an additive flame retardant, are expected to be from both point sources (e.g., from processing facilities, product manufacturing) as well as from diffuse sources. Releases may occur in both indoor and outdoor environments.

According to submissions made under section 71 of CEPA and publicly available technical literature, DBDPE is imported into Canada in neat form, as formulations, and in commercial products or products available to consumers (Canada 2013, CCC 2011).

DBDPE release to the environment is most likely to occur during the manufacturing, formulation or industrial use. Releases to the environment are expected to occur primarily through wastewater, with some release to water directly from industrial sites. Canadian effluent and wastewater biosolids data show that publicly owned wastewater treatment systems (WWTS) with higher proportional industrial inputs (e.g., greater than 30%) have higher DBDPE concentrations (e.g., 10X) than those dominated by domestic (non-industrial) influent input (Kim et al. 2014; Melymuk et al. 2014). Release to the soil could occur through the application of wastewater biosolids to agricultural and pasture lands.

In terms of migration from commercial products and products available to consumers, or as an additive brominated flame retardant that is blended with the polymer product (rather than a reactive flame retardant chemical bonded to the polymer product), there is the possibility of release from these products to the environment (Guerra et al. 2011). DBDPE is proposed to be released to air or dust by volatilization or abrasion of product containing the substance (Melymuk et al. 2014), which could result in DBDPE deposition to soil and water release to publicly owned WWTS.

Although DBDPE has low volatility, emissions to air (e.g., from airborne particles, dust or release from products) could result in atmospheric deposition to soil and water. For example, a pattern of increasing pond sediment DBDPE concentrations with proximity to chemical manufacturing facilities has been attributed largely to transport through the movement of air and airborne particles (Wei et al. 2012). When a substance is transferred to land, it may become bound to soil, be washed into the sewer or surface water or transferred by wind or rain to nearby soil.

Finally, while the majority of landfills in Canada treat their leachate through WWTS, landfills that do not collect and treat their leachate may potentially release substances to ground or surface water via leachate or, although unlikely, there is potential for releases of substances to the atmosphere through gas from landfills that do not collect and destroy their landfill gas.

This information and fate in the environment are used to further develop exposure characterization scenarios to estimate resulting environmental concentrations.

7. Measured environmental concentrations

There are challenges to measuring and analyzing very hydrophobic substances like DBDPE in environmental media, including very low solubility in water and organic solvents; tendency to adsorb to particulates and solids (e.g., organisms and/or chamber walls); degradation during clean-up and instrumental analysis; and generally less expertise in the analysis of the substance (Breitholtz et al. 2006; Kierkegaard et al. 2009). DBDPE is a difficult brominated flame retardant to analyze, and uncertainty can reach 40 to 60%, depending on the internal standard used for quantification (2014 communication from A. Covaci to Environment Canada; unreferenced). Most studies to date have analyzed DBDPE using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) using analysis for the bromide ion. Furthermore, as is common for ‘emerging’ chemical substances, established analytical methods to detect, identify, and quantify DBDPE transformation products in environmental matrices are lacking (Dirtu et al. 2014, Lambropoulou and Nollet 2014).

DBDPE has been detected in the Canadian environment, as well as in other countries, generally at low levels. Highest concentrations of DBDPE tend to be found close to urban or industrial areas (Tables 7-1 and 7-2, ECCC, HC 2019).

Few studies have reported the presence of DBDPE in air. Air and precipitation samples were collected every 12 days at five sites near the North American Great Lakes from 2003 to 2011 (inclusive) by the Integrated Atmospheric Deposition Network (IADN). On the basis of IADN data, Ma et al. (2013) reported overall DBDPE average atmospheric concentrations (vapour + particle) of 1.2 to 5.2 pg/m3 for the five sites (detection frequency ranged from 8 to 54%), with the highest concentrations near urban areas (increasing as a function of population). Vernier and Hites (2008) evaluated earlier data from the same sites, and determined a maximum mean concentration of ~ 22 pg/m3 near an urban area (Cleveland) but lower levels in a remote area (Eagle Harbour, Michigan,~ 1 pg/m3, read from graph).

In the Canadian Arctic (Devon Ice Cap, Nunavut), DBDPE was detectable in some horizons of snow pits; however, the concentration patterns did not show clear deposition time trends (Meyer et al. 2012), and the concentrations (Non Detected (ND) – 24 pg/L, detected only twice) were, on average, lower than those reported for the Norwegian Arctic. DBDPE has been measured in precipitation in the Great Lakes area, with mean concentrations of 256 to 1440 pg/L between 2003 and 2009 (Salmova and Hites 2010, 2011).

To date, only one study has detected DBDPE in Canadian surface water (Venier et al. 2014), reporting Great Lake basin wide DBDPE concentrations from an average of 0.25 ± 0.05 pg/L (Lake Huron) to 10.8 pg/L (Lake Ontario). In the same study, 6.7pg/L was the DBDPE concentration observed in Lake Superior, which was influenced by a sampling station near the heavily industrialized urban centre of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Other studies of Canadian surface water, however, have not detected DBDPE (Law et al. 2006; Muir et al. 2011).

While no soil measurements for DBDPE have been reported for Canada or North America, DBDPE has been measured and detected in soil in Asia (e.g., 1.13 (farmland) to 1612 (industrialized land of an e-waste site) ng/g dw for China (Lin et al. 2015).

DBDPE sediment concentrations have been reported for the Great Lakes (0.11 to ~200 ng/g dw) (Kolic et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2012). A recent sediment core study from the Great Lakes (Canada and the United States) reported DBDPE surface sediment concentrations ranging from 0.11 to 2.8 ng/g dw, with the highest concentrations in Lake Michigan (up to 2.5 ng/g dw) and Lake Huron (up to 2.8 ng/g dw) (Yang et al. 2012). DBDPE was the sixth most frequently detected of the 13 BFRs surveyed. Yang et al. 2012 noted that while DBDPE surface sediment concentrations were approximately one order of magnitude lower than those of decaBDE (0.87 to 106 ng/g dw), DBDPE input is increasing rapidly, with sediment concentrations estimated to double every 3 to 5 years in Lake Michigan and approximately every 6 to 7 years in Lake Ontario. In another study, Kolic et al. (2009) presented DBDPE concentrations ranging from approximately 8 to 200 ng/g dw (read from graph) in surface sediment from Lake Ontario and its tributaries. However, DBDPE was not detected in the sediments of Lake Winnipeg during a 2003 sampling program (Law et al. 2006). In an Arctic marine sediment study, Cai et al. (2012) measured DBDPE in sediment from the Canada Basin, Chukchi Sea, and Bering Sea of the western Arctic Ocean (non-detect to 452.6 pg/g dw), with an average of 166.7 pg/g dw. These concentrations were on the same order of magnitude as decaBDE concentrations measured in the same study.

Elsewhere in North America, Wei et al. (2012) reported a pattern of increasing lake or pond sediment DBDPE concentrations with increasing proximity to chemical manufacturing facilities that produce DBDPE (and produced DecaBDE) in Arkansas, USA, including the highest concentration yet reported for DBDPE (up to 2394 ng/g dw). As there are no manufacturing water releases to surface waters (but WWTS water and biosolids input occurred at on site from 1952 to1989), the dominant pathway for transport of DBDPE and decaBDE from the emission sources to the sampling sites was assumed to be through the movement of air and airborne particles.

DBDPE has been widely reported in wastewater effluent and biosolids (a potential route to the surface water and soil environments). In Canada, a recent study of 20 WWTS by Kim et al. (2014) reported mean DBDPE concentrations in final effluent to range from ND to 7.1 ng/L, with 86% of samples having nondetectable levels of DBDPE. Another study of six WWTS in Canada found DBDPE was detected in two of four samples, estimated at ~3 ng/L (value read from graph) (Zhou et al. 2010a). DBDPE estimates for WWTS biosolids vary greatly. Within Canada, measurements from Ontario range from 5.6 ng/g dw (wastewater biosolids) (Konstantinov et al. 2006) to ~100 ng/g dw (Kolic et al. 2009, value read from graph), although the level of treatment was not indicated. A study of 20 WWTS in Canada reported treated biosolids concentrations ranged from non-detect to 220 ng/g dw (Kim et al. 2014).

In Canada, DBDPE has been sampled in the fish tissue of several freshwater species, and concentrations have generally ranged from non-detect to very low (i.e., mean concentration ≤ 1 ng/g lipid weight (lw) (or wet weight (ww)) (Law et al. 2006; Ismail et al. 2006; Kolic et al. 2009; Byer et al. 2010, Byer 2013; Zhou et al. 2010b; Muir et al. 2011; Environment Canada 2014). The exception is a study reporting liver concentrations in 1 of 11 northern pike from the St. Lawrence River area and tributaries of 26.7 ng/g lw (3.78 ng/g ww) (Houde et al. 2014). DBDPE was not detected in mussels and plankton in Lake Winnipeg (2000 to 2002) (Law et al. 2006), nor in zooplankton sampled between 2006 and 2010 in the Great Lakes (Lake Ontario and Lake Erie), nor in a remote Ontario Lake (Lake Opeongo) (Muir et al. 2011).

Avian studies in Canada have occasionally detected DBDPE. DBDPE was not detected in eggs of four gull species (glaucous-winged (Larus glaucescens), California (Larus californicus), ring-billed (Larus delawarensis), and herring gulls (Larus argentatus) collected from 26 colonies across Canada (Atlantic to Pacific) (Chen et al. 2012). DBDPE was detected in 1 of 12 Peregrine Falcon eggs collected from the Great Lakes watershed, at 8.2 ng/g lw (Guerra et al. 2012), but DBDPE was not detected in Bald Eagle plasma collected from birds in the Great Lakes area, despite high levels of decaBDE in the same samples (Venier et al. 2010). Of the pools of eggs from seven Laurentian area Great Lakes colonies of herring gulls (Larus argentatus) collected between 1982 and 2006 (Gauthier et al. 2009), DBDPE was not detected prior to 1996, but was detected (mean concentration up to 11 ng/g ww) in 5 of 63 non-consecutive pools of eggs between 1996 and 2004. In 2005, DBDPE was detected in eggs from 3 of 7 colonies with concentrations up to 288 ng/g ww, and in 2006, eggs from 2 of 7 colonies had DBDPE concentrations up to 44 ng/g ww (Gauthier et al. 2009)

Ringed seal blubber samples from the Canadian Arctic in 2006 did not have measurable levels of DBDPE (de Wit et al. 2011). Polar bear adipose tissue samples from the Canadian Arctic, Alaska, and Svalbard, collected between 2005 and 2008, detected DBDPE in less than 14% of samples (McKinney et al. 2011b).

| Media (units) | Location(s) | Years (not continuous) | Concentration range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air (pg/m3) | Nunavut, Great Lakes | 2005 to 2008 | ND – 22 |

| Surface water (pg/L) | Lake Winnipeg, Great Lakes, Ontario | 2004 to 2012 | ND-10.8 |

| Sediment (ng/g dw) | Lake Winnipeg, Great Lakes, Ontario, Canada Basin (arctic marine) | 2003 to 2008 | ND – 200 |

| Wastewater effluent (ng/L) | Ontario | NS | ND – 7.1 |

| Biosolids (ng/g dw) | Ontario | 2003 to 2010 | ND – 220 |

| Biota – aquatic (ng/g lw) | St. Lawrence, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Great Lakes, Lake Winnipeg | 2000 to 2012 | ND – 26.7 |

| Biota –terrestrial and avian (ng/g lw) | Great Lakes, Canadian Arctic, Southern NWT | 1982 to 2010 | ND – 8.2c |

Abbreviations: ND, not detected; NS, not stated.

a See Supporting Information (ECCC, HC 2019) for references and study details.

b Although wastewater system effluent and biosolids are not “environment,” they represent a direct source to the environment and are included in this table.

c Note the DBDPE range reported for terrestrial and avian organisms in “wet weight” (ww) is ND to 288 ng/g.

| Media (units) | Location(s) | Years (not continuous) | Concentration range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air (pg/m3) | North America, Europe, Asia, Africa | 2003 to 2011 | ND - 3578 |

| Surface water (pg/L) | North America, Europe, Asia | 2003 to 2010 | ND – 38 |

| Soil (ng/g dw) | Asia | 2006 to 2007 | ND – 1612 |

| Sediment (ng/g dw) | North America, Europe, Asia | 2002 to 2009 | ND - 2394 |

| Wastewater, effluent (ng/L) | North America, Europe | 2006 to 2009 | ND – 7.1 (±5.6 SD) |

| Biosolids (ng/g dw) | North America, Australia, Africa, Asia, | 1998 to 2010 | ND – 4820 |

| Biota – aquatic (ng/g lw) | North America, South America, Asia, Europe | 1986 to 2010 | ND - 352 |

| Biota – terrestrial and avian (ng/g lw) | North America, Europe, Asia | 1982 to 2010 | ND – 863 |

a See Supporting Information (ECCC, HC 2019) for references and study details.

b Although wastewater system effluent and biosolids are not “environment,” they are included in this table since they are the pathway via which DBDPE from industrial inputs are expected to be released to the environment.

However, it is also important to consider how DBDPE levels in the environment may increase in future, for example, relative to the OFR it is proposed to replace, decaBDE. Ma et al. (2013) recently determined that DBDPE particle air concentrations in the Great Lakes area were similar to decaBDE air concentrations at most sampling locations, with the exception of Cleveland where manufacturing of decaBDE was expected to occur; the authors suggest the pattern indicates both substances are in use and share similar applications and sources (e.g., including products available to consumers). Goosey et al. (2013) also determined DBDPE dust concentrations in Toronto homes to be similar to those of decaBDE (see Section 10), both likely related to electrical and electronic equipment.

A comparison of DBDPE to decaBDE measurement ratios for WWTS data can provide evidence of where DBDPE use is high or substitution for decaBDE has occurred (Ricklund et al. 2008). Kim et al. (2013; 2014) measured both DBDPE and decaBDE in the same influent and effluent samples from 20 WWTS in Canada, representing populations of 1500 to greater than 1 000 000. The median influent DBDPE concentration was: 3.7 ng/L (maximum= 130 ng/L), while the median decaBDE concentration was 74.8 (and maximum= 433 ng/L), resulting in a median [DBDPE]/[decaBDE] influent ratio of 0.05. Similarly, the median final effluent DBDPE concentration was 0.2 (and maximum=7.1 ng/L), while the median decaBDE concentration was 3.7 (and maximum=59.9 ng/L), resulting in a similar [DBDPE]/[decaBDE] ratio of 0.055. An international survey of DBDPE in wastewater biosolids (Ricklund et al. 2008), showed ratios for Canadian samples of [DBDPE]/[decaBDE] in biosolids that ranged from 0.01 to 0.078. These ratios in both wastewater and biosolids indicate that DBDPE release reaching WWTS (including that from commercial products or products available to consumers) is still lower than that of decaBDE.

8. Environmental fate and behaviour

8.1 Environmental distribution

DBDPE is expected to be released to the environment primarily through wastewater, but may undergo some migration from products to the atmosphere as non-reactive brominated flame retardants have potential for some release from polymers (e.g., PBDEs)(Guerra et al. 2011). DBDPE is likely highly removed by adsorption to biosolids in wastewater treatment plants (Kim et al. 2014) and can be applied to agricultural soils during biosolids amendment. Level III fugacity modelling (Table 8-1) using the updated EQC model (v 1.0, 2012), was applied to describe the fate for these expected modes of entry into the environment. Generally, the results of Level III fugacity modelling show that DBDPE is expected to predominantly reside in soil and/or sediment, depending on the compartment of release.

| Substance released to: | Air (%) | Water (%) | Soil (%) | Sediment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air (100%) | 0.5 | 0.4 | 82.7 | 16.4 |

| Water (100%) | Negligible | 2.5 | Negligible | 97.5 |

| Soil (100%) | Negligible | Negligible | 99.9 | 0.1 |

Very low water solubility (8.10 x 10-6 mg/L), low vapour pressure (5.59 x 10-10 Pa at 25°C), low air–water partition coefficient (log Kaw = -4.57), and very high partition coefficients (log Kow of 9.89, estimated log Koc of 8.58) suggest that DBDPE released into the environment will be less likely to partition into and/or remain in air and water, moving instead to the sediments and soil. If released to air, a small fraction (less than 1%) DBDPE is expected to remain in air, with most of the substance depositing to soil and water with further partitioning to sediment. However, on the basis of predicted rates of degradation (greater than 4 days) and predicted patterns of transport (see description below), the small mass of DBDPE that remains in air has the potential for dispersion.

The high partition coefficients indicate that DBDPE released into surface water from wastewater treatment systems is expected to adsorb to the organic fraction of suspended solids and sediments, with 2.5% remaining in water. Volatilization from surface water to air is not expected. However, as in the case with air, the small fraction remaining is likely persistent and has the potential for some transport (e.g., particle transport). On the basis of its high log Koc, once in the sediment, DBDPE is not expected to be mobile, and may remain in this compartment with limited or slow degradation.

When DBDPE is released to soil as a function of biosolids application to agricultural lands, the majority of the mass fraction is expected to remain adsorbed to soil (99.9%) owing to its very hydrophobic nature. Evaporation from soil into air is not expected because of an extremely low vapour pressure. If released to soil, DBDPE is expected to be immobile based on its high estimated log Koc. In addition, low degradation is expected in soil; DBDPE is therefore likely to remain in this compartment, and the loss process in soil will mainly be driven by soil burial or surface runoff. The results of Level III fugacity modelling (Table 8-1) support the expectation that at steady state DBDPE predominantly distributes in soil or sediment, depending on the compartment of release (New EQC 2012).

8.1.1 Long-range transport potential

Predicted log Koa (14.45) and log Kaw (-4.57) values for DBDPE suggest low potential to reach the Arctic (Wania 2006, Brown and Wania 2008). The substance is identified as highly sorptive, sorbing to particles in atmospheric and aqueous media, and therefore, particle settling is predicted to limit long range transport (Brown and Wania 2008). However, if particle bound transport is more efficient than expected, given low predicted rates of degradation in air (greater than 4 days in gas phase, longer with air particles), there is the possibility that DBDPE could persist and be transported to the Arctic.

DBDPE was measured in horizons of snow pits dug in 2005, 2006 and 2008 in the Canadian Arctic (Devon Ice Cap, Nunavut); however, concentration patterns did not show clear deposition time trends (Meyer et al. 2012). In the Norwegian Arctic, Hermanson et al. (2010) measured DBDPE inputs of approximately 3.6 pg/cm2/yr (~1988) to 3.4 pg/cm2/yr (2005) in the top 34 m of an ice core (representing 1953 to 2005) from the western-most ice sheet of Svalbard; this suggests that either particle phase transport could be more important than expected, and/or that the quantity of the flame retardant used in source areas contributing to the ice sheet affects observations (Hermanson et al. 2010). However, other monitoring data for remote areas suggests that DBDPE does not currently seem to be found widely in the Arctic (e.g., de Wit et al. 2010, McKinney et al. 2011b).

The OECD POPs Screening Model can be used to help identify chemicals with high persistence and long-range transport potential (Scheringer et al. 2006). The Characteristic Travel Distance (CTD) calculated for DBDPE using the OECD model is 2860 km indicating that DBDPE has a significant potential for transport in air (with 99.99% of mass in air partitioned to particles/aerosols), but this is below the boundary (5097 km, CTD of PCB 28) suggested for global pollutants by Klasmeier et al. (2006). The model also calculates an overall persistence (Pov) of 277 days, and the transfer efficiency (TE), which is the percentage of emission flux to air that is deposited to the surface (water and soil) in a remote region. The TE for DBDPE was calculated to be 12.7%, which is above the boundary of 2.248% (PCB-28) established on the basis of the model’s reference substances empirically known to be deposited from air to soil or water. The high TE means that DBDPE might be deposited to Earth’s surface in remote regions.

In general, while DBDPE (considering its physical chemical properties) might not be expected to be a high concern for long-range transport, a high predicted transfer efficiency and some detection of DBDPE in remote areas, suggests the role of particle bound transport allows long-range transport of DBDPE to be possible. As well, it is unknown how susceptible potential DBDPE degradation products (see next section) could be for long-range transport.

8.2 Environmental persistence

On the basis of likely DBDPE releases and partitioning characteristics, environmental persistence is most relevant for the soil and sediment compartments where the majority of the substance is expected to be found. However, owing to the potential particle transport of DBDPE in air and water, all media are considered in this section. Empirical and modelled data were considered in the weight-of-evidence for DBDPE persistence. Data were also compared to the analogue, decaBDE. Relevant transformation processes for DBDPE include photodegradation, biodegradation and biotransformation, as well as combustion/pyrolysis.

Generally, model predictions are consistent with experimental findings that aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of DBDPE is limited and that DBDPE is expected to be persistent in water, soil, and sediment. Photodegradation of DBDPE in solvents (e.g., n-hexane, tetrahydro-furan (THF)) may be fast; however, photodegradation could take much longer in other matrices/substrates (e.g., greater than 224 days in HIPS powder; Kajiwara et al. 2008). Modelled predictions for DBDPE in air suggest a half-life greater than 4 days (gas phase) and or an overall persistence (Pov) of 277 days (OECD POPs model). DBDPE testing under longer-term (e.g., greater than 6 month), environmentally relevant conditions to determine the degradation pathways and transformation products is lacking (possibly influenced by analytical challenges). Nevertheless, potential DBDPE transformation products were evaluated on the basis of predictions from photodegradation studies and biodegradation modeling, and by considering analogue decaBDE transformation products.

Tables 8-2 and 8-3 present empirical and modelled degradation data for DBDPE; a detailed description of studies is found in ECCC, HC (2019).

8.2.1 Abiotic degradation

A summary (2019 Albemarle Europe SPRL summary of information submitted under REACH as lead registrant and provided to Environment and Climate Change Canada in the context of the consultation on the Proposed amendments to the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations: 2018, unreferenced) of a study performed on the degradation of DBDPE at high temperature applications and during multiple recycling cycles is available. In this study, high-impact polystyrene samples treated with flame retardants (12% DBDPE and 4% antimony trioxide) were subjected to 6 recycling cycles at 250°C which the researchers noted approximated worst case conditions for high temperature use processes. The study found no observable degradation to octaBDPEs or lower brominated congeners at 100-200 ppm levels in resin. Approximately 0.2% of DBDPE was identified to debrominate to nonaBDPE during the six recycling cycles.

Kajiwara et al. (2008) observed no degradation of DBDPE in spiked high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) powder exposed to sunlight for 224 days (half-life was estimated at greater than 224 days), while the half-life of decaBDE in the same matrix was estimated at 51 days. Differences between DBDPE and decaBDE were attributed to structural differences in ether (oxygen) bond vs. ethane bond.

Nadjia et al. (2014) measured very rapid photolytic degradation of DBDPE in solvent under artificial UV-visible light: 63.18% degradation within 180 seconds. The degradation process is reported as stepwise reductive debromination.

Wang et al. (2012) studied the photolytic degradation of DBDPE under UV light using a range of matrices and solvents, including methanol/water and humic acid/water (to simulate the aquatic environment) and silica gel (to simulate the soil/sediment environment). These latter matrices are the most relevant to environmental conditions. Photolytic degradation occurred in all solvents/matrices (and none in the dark control), with 33.7 to 99.6% of the DBDPE lost. Degradation rates depended on the solvent used (Table 8-2). All matrices showed debromination and formation of nonaBDPEs, with subsequent degradation to octa-, and heptaBDPE congeners, although the percentage of transformation product relative to parent was not reported in the study. The authors recognize the presence of nona-BDPEs in the original solutions may be a result of impurities of the technical products (purity not reported) and/or degradation during sample injection; however, the concentrations of nona-BDPEs increased continuously from 0 to 45 min, and octaBDPEs (from 4 minutes on) and heptaBDPEs (from 30 minutes on) increased continuously during the experiments. The formation of tetra- to hexaBDPEs with longer exposure times was proposed, but not monitored.

In a preliminary study, Kierkegaard et al. (2009) studied technical DBDPE in n-hexane exposed to a daylight-mimicking fluorescent lamp, and found DBDPE was degraded, producing two nonabrominated congeners, as well as a number of peaks tentatively identified as octabrominated products. The authors also reported that DBDPE degrades to lower (mainly two nona-) brominated congeners during sample preparation/analysis, although it appeared to be less sensitive to thermal degradation than decaBDE (Kierkegaard et al. 2009).

The predicted half-life for atmospheric degradation of DBDPE because of the reaction with the hydroxyl radical is 4.47 days for the fraction of chemical that is in the gas phase (12-hr day, AOPWIN 2010). The results of AEROWIN (2010) predict a high fraction of DBDPE absorption to airborne particles (Phi = 1), and therefore, that the rate of DBDPE photolysis is likely lower than predicted (i.e., half-life longer than predicted 4.47 days). This is consistent with the OECD Pops model which finds 99.9% of DBDPE in air is sorbed to aerosols, and an overall persistence of 277 days for the substance.

On the basis of abiotic degradation modelled data and empirical data for DBDPE, the substance is expected to be persistent in air (Table 8-2). However, fate modelling indicates only a very small proportion of DBDPE released into the environment is expected to partition into air, and atmospheric concentrations of DBDPE are expected to be low. The high Koc of DBDPE suggests that DBDPE released directly into air will likely adsorb to particulates, with subsequent removal to soil or water by wet and dry deposition. Owing to DBDPE’s low water solubility, particle adsorption behaviour, as well as light attenuation by humic materials, photolysis in natural waters, soils, and biosolids is expected to be limited (Environment Agency 2007).

DBDPE does not contain functional groups expected to undergo hydrolysis.

| Medium | Fate process | Degradation value | Degradation endpoint / units | Methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Impact Polystyrene (HIPS) | Photolysis | > 224 days | half-life/days | Published study | Kajiwara et al. 2008 |

| tetrahydro-furan | Photolysis | 1.89 min | half-life/min | Published study | Nadjia et al. 2014 |

| n-hexane | Photolysis | 16.6 min | half-life/min | Published study | Wang et al. 2012 |

| tetrahydro-furan | Photolysis | 6 min | half-life/min | Published study | Wang et al. 2012 |

| methanol/ water | Photolysis | >240 min | half-life/min | Published study | Wang et al. 2012 |

| humic acid/ water | Photolysis | 30 – 60 min | half-life/min | Published study | Wang et al. 2012 |

| silica gel | Photolysis | 75.9 min | half-life/min | Published study | Wang et al. 2012 |

| Air | Atmospheric oxidation | 4.47 daysb | half-life/days | Model | AOPWIN 2010a |

| Air | Ozone reaction | n/ac | n/ac | Model | AOPWIN 2010a |

| Water | Hydrolysis | n/ac | n/ac | Model | HYDROWIN 2010a |

a EPIsuite (2010-2012).

b AEROWIN (2010) predicts high fraction of DBDPE absorption to airborne particles (Phi = 1), therefore rate of DBDPE photolysis likely lower than predicted (i.e., half-life longer than predicted).

c Model does not provide an estimate for this type of structure.

8.2.2 Biodegradation

Laboratory tests have shown DBDPE is not likely to biodegrade quickly under aerobic conditions. A CITI (1991a) study measuring biodegradation by microorganisms found a range of 1–6 % biodegradation (mean of 2%) over 28 days in a ready-biodegradation test for DBDPE.

An inherent biodegradability study by Schaefer and Carpenter (2010) which followed the Concawe Test (OECD Draft Method 302D), found an average cumulative rate of 2.2% biodegradation after 90 days, indicating that DBDPE is not inherently biodegradable under aerobic conditions. The study indicates that test media were also analyzed for predicted degradation products (using radiolabeled test chambers), and reported no transformation products over the 90 day period, although the percent cut-off for identification was not reported.

The four ultimate biodegradation submodels (BIOWIN 2010; Catalogic 2012) predict that biodegradation is very slow or recalcitrant. In addition, a primary biodegradation model, BIOWIN Sub-model 4 (primary survey model), predicts that the substance is recalcitrant.

The existing data for anaerobic degradation of DBDPE suggests that if the substance degrades, it does so very slowly. An anaerobic biodegradation study that compared radiolabeled DBDPE in biotic and abiotic treatments of anaerobic digester sludge (initial dose of DBDPE 31 mg/L in THF), showed no mineralization or transformation over 63 days (Schaefer and Matthews 2011). Measurements of 14C activity at days 0, 30 and 63, as well as a mass-balance of compartments (solid sludge, extractable, and volatized), reported only the parent DBDPE. Earlier laboratory studies of analogue decaBDE (Gerecke et al. 2005, 2006) have also shown decaBDE to undergo slow anaerobically mediated reductive debromination, with a half-life of up to 700 days.

Recently, three studies examined aerobic and anaerobic DBDPE degradation and transformation in soils and sediments over a 6 month test period (Stenzel and Schaefer 2015a, 2015b, 2015c). These studies evaluated transformation of parent DBDPE from labelled radioactivity measurements over the study period, and reported maximum non-parent radioactivity (i.e. potential transformation product) increases from 1.6% to 9.9% in sediment and from 2.2% to 3.1% in soil (although non-parent radioactivity decreased in some soil tests). While the authors suggest the non-parent labelled radioactivity could be attributed to impurities and conclude that no transformation occurred (i.e. parent DBDPE greater than 91% at end of studies), impurities would not be expected to increase over the test period. Overall these new studies suggest that very limited DBDPE degradation, if any, occurred within the 6 month period of the studies.

In a further study, biotransformation of radiolabelled DBDPE was examined in aerobic soil systems for up to 60-61 days in a greenhouse environment with and without growing plants (2019 Albemarle Europe SPRL summary of information submitted under REACH as lead registrant and provided to Environment and Climate Change Canada in the context of the consultation on the Proposed amendments to the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations: 2018, unreferenced). In this study, four types of soil (sandy loam, loam, silt loam, loamy sand) and six plant species (radish, ryegrass, alfalfa, zucchini, corn and pumpkin) were used. The study found that DBDPE and nonaBDPE moved to a small extent into the roots of rye grass plants (nonaBDPE up to 0.10% of total amount of radioactivity and DBDPE up to 2.89% of the total amount of reactivity) and to a lower or comparable extent to the roots of the other plant species. DBDPE was the predominant analyte in root and soil samples based on HPLC/beta RAM analysis. No root to shoot movement of DBDPE or nonaBDPE was observed for all 6 plant species. The levels of nonaBDPE were either lower or statistically the same as those observed in the dose stock solution/dose mixture used in the tests. No hexa- to octaBDPEs were detected in any of the soil or plant samples, and overall, the study suggested that no DBDPE biodegradation occurred in soil and plant samples. In addition, no related debrominated congeners were identified based on non-target chemical analysis.

These aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation tests, as well as modelling results, indicate that the half-life in water is likely to be long, and that the substance is therefore likely to persist in water (Table 8-3). Using an extrapolation ratio of 1:1:4 for a water: soil: sediment biodegradation half-life (Boethling et al. 1995), DBDPE is expected to be persistent in soil and sediment, and thus is likely to present long-term exposures in these media.

| Medium | Fate process | Degradation value | Degradation endpoint / units | Methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activated sludge | Bio-degradation | 1- 6% (mean 2%) | 28-day Biodegradation BOD/% |

OECD 301C (Modified MITI I test) |

CITI 1991a |

| Mixture of pre-exposed sludge and soil | Enhanced aerobic Bio-degradation | 2.2% | 90-day aerobic Biodegradation IC/TOC/14C-activity |

OECD 302D (CONCAWE test) |

Schaefer and Carpenter 2010 |

| Anaerobic digester sludge | Biotic/ Abiotic Anaerobic mineralization | 0 (biotic) 0 (abiotic) | 63-day anaerobic mineralization /% |

OECD 314C (Anaerobic digester sludge) |

Schaefer and Matthews 2011 |

| Water | Primary Bio-degradation (aerobic) | 0.7743a “recalcitrant” |

NA | QSAR Model | BIOWIN 2010d |

| Water | Bio-degradation (aerobic) | -0.4568a “recalcitrant” |

NA | QSAR Model | BIOWIN 2010e |

| Water | Bio-degradation (aerobic) | -0.6209b “biodegrades slowly” |

NA | QSAR Model | BIOWIN 2010f |

| Water | Bio-degradation (aerobic) | 0.00b “biodegrades slowly” |

NA | QSAR Model | BIOWIN 2010g |

| Water | Bio-degradation (aerobic) | % BOD = 0.41c “biodegrades very slowly” |

ultimate half-life > 10 years | QSAR Model | Catalogic 2012 |

a Output is a numerical score from 0 to 5. NA=not applicable.

b Output is a probability score.

c Some uncertainty associated with model predictions, as substance is less than 60% (42%) covered by structural domain of model.

d Sub-model 4: Expert Survey (qualitative results).

e Sub-model 3: Expert Survey (qualitative results).

f Sub-model 5: MITI linear probability.

g Sub-model 6: MITI non-linear probability.

DBDPE appears to be moderately well covered by the biodegradation models used to estimate degradation. The number of fragments and molecular size covered by the domain of the BIOWIN Submodels 5 and 6 (aerobic biodegradation, MITI) suggest high coverage for DBDPE. The domain covered by BIOWIN Submodels 3 and 4 (aerobic biodegradation, Expert Survey) includes substances with fewer aromatic bromide fragments and smaller molecular weights than DBDPE; however, the degradation predictions are consistent with other modeled results and empirical data. There is some uncertainty associated with the CATALOGIC (2012) model predictions in that there is only 42% coverage of the DBDPE by the structural domain of the Catalogic model (greater than 60% structural coverage is recommended). However, given that the predicted results agree with other model predictions (BIOWIN submodels), and agree with the existing empirical data, it would suggest that the model is extrapolating correctly beyond interpolation space.

Modeling predictions and experimental data indicate very slow and/or limited biodegradation of DBDPE (ECCC, HC 2019). Catalogic model (2012) predictions indicate that when biodegradation occurs, while most of the substance stays as parent, there is a low probability of limited debromination under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, leading to nonaBDPEs and octaBDPEs, hydroxylated nonaBDPEs, and a form of brominated phenyl acid (ECCC, HC 2019).

Wei et al.(2012) measured two unknown brominated compounds in pond sediments near a DBDPE manufacturing plant in Arkansas, USA (a former WWTS biosolids pond), which were further identified as two nonabromodiphenyl ethanes (nonaBDPEs) when matched to photolytic debromination peaks in hexane. The nonaBDPE concentration increased towards the surface, with a ratio of 1.3 nona/DBDPE compared to ~0.7 nona/DBDPE in standards or other pond sediments. The increased nonaBDPE presence was attributed to DBDPE debromination in the upper sediment of one of the ponds. This pond also demonstrated PBDE debromination, which was attributed to a complex process likely involving physical and biological influences (ECCC, HC 2019).

Recently, very slow debromination of analogue decaBDE has been measured in sediment microcosms in a remote lake on the Canadian Shield under natural conditions over 1 month (Orihel et al. 2016). Although only a small loss of 13C-decaBDE was measured, octa- and nonaBDEs were formed from 13C-decaBDE in littoral and profundal sediments, and trace amounts of di- to heptaBDEs were detected in some samples. Degree of debromination was determined not to be influenced by light or dark conditions, although more nona- and octaBDEs were formed under oxic conditions than under anoxic conditions.

8.2.3 Metabolic biotransformation

Empirical metabolic biotransformation studies that discuss potential for DBDPE degradation pathways and transformation products are described in the Potential for Bioaccumulation section.

8.2.4 Combustion and pyrolysis

Thermal degradation for DBDPE in fires is identified as a potential source of degradation products. DBDPE may be susceptible to the formation of bromotoluenes, via cleavage of the ethane bridge (Eljarrat and Barceló 2011; Dirtu et al. 2014). Jakab et al. (2003) reported, under pyrolysis conditions, DBDPE in high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) samples, produces a relatively high yield of brominated toluenes including the major product pentabromotoluene (PBT) along with other lower brominated toluenes. This pathway differs from that of decaBDE, which can decompose to produce brominated dibenzofurans under pyrolysis conditions (Jakab et al. 2003); the formation of brominated dibenzofurans is not generally observed for DBDPE. Various industry reports were reviewed for analytical determinations of polybrominated di-benzo-p-dioxins (PBDDs) and dibenzofurans (PBDFs) in relation to DBDPE commercial products, and polymers containing DBDPE (2019 Albemarle Europe SPRL summary of information submitted under REACH as lead registrant and provided to Environment and Climate Change Canada in the context of the consultation on the Proposed amendments to the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations: 2018, unreferenced). The reports noted that thermal degradation and incineration of DBDPE results predominantly in polybrominated toluenes rather than PBDFs or PBDDs. The review concluded that the flame retardant, the polymer containing the flame retardant, and the polymer containing the flame retardant after simulated recycling did not contain PBDDs/PBDFs and were generally below the limits of quantification of the respective methods.

8.2.5 Persistence of transformation products

A summary of potential DBDPE transformation is found in the Supporting Information document (ECCC, HC 2019). Laboratory photodegradation studies (largely conducted with solvents) described in the section above report DBDPE debromination (Nadjia et al. 2014) to nona-, octa- and heptaBDPEs (Wang et al. 2012, Dirtu et al. 2014). Sediment studies have measured nonaBDPEs in the environment (Wei et al. 2012, He et al. 2012). Catalogic model (2012) predictions indicate that biodegradation may lead to limited debromination under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, leading to nonaBDPEs and octaBDPEs, hydroxylated nonaBDPEs, and a form of brominated phenyl acid. These predicted transformation products are expected to represent a minor fraction relative to parent DBDPE; however, they are similar to predicted/measured fractions of analogue decaBDE debromination products. Within the CPOPs model, the Bmax model (CPOPs 2012) uses rat metabolism data to predict DBDPE transformation to hydroxylated DBDPE and hydroxylated nonaBDPE. Considering DBDPE’s close analogue decaBDE, a substance that debrominates to lower brominated PBDEs (i.e., nonaBDEs through tetraBDEs) under specific conditions (e.g., photodegradation, aerobic biodegradation and metabolism) (Environment Canada 2010), it is reasonable to expect that DBDPE may also debrominate to lower BDPE transformation products (e.g., nona, octa, hepta-, hexa, and pentaBDPEs) following the pathway of debromination established for decaBDE (Appendix C, Table C-1).

Recently, three studies of aerobic and anaerobic DBDPE degradation and transformation in soils and sediments over a six month test period were conducted (Stenzel and Schaefer 2015a, 2015b, 2015c). These studies evaluated transformation of parent DBDPE from labelled radioactivity measurements over the study period, and reported maximum non-parent radioactivity (e.g. potential transformation product) increases ranging from 1.6% to 9.9% in sediment and from 2.2% to 3.1% in soil (although non-parent radioactivity decreased in some soil tests). The authors suggest the non-parent labelled radioactivity could be attributed to impurities; however, impurities would not be expected to increase over the test period. Other uncertainties with these studies relate to analytical difficulties for DBDPE measurements. Given that transformation product formation is expected to represent a small percentage of parent DBDPE, accurate measurement of DBDPE and non-parent concentrations is critical to understanding the transformation process. While these new studies suggest very limited, if any, DBDPE degradation occurs during the 6 month period of the studies (e.g. parent DBDPE remains greater than 91%), this result is not unexpected given the assessment estimates the half-life of DBDPE in soil and sediment to be in the range of many months to years, and transformation products are predicted to represent a small (but important) fraction relative to parent DBDPE.

Owing to the lack of experimental data on the transformation products, (Q)SAR modelling was conducted to assess their persistence, biodegradation and toxicity characteristics. See Appendix C for a description of transformation product (Q)SAR modeling and physical chemical properties (Table C-2).

To evaluate persistence of potential transformation products, a (Q)SAR-based degradation modelling approach was used. Results of BIOWIN (2010) sub-models suggest that all potential transformation products (nona- through pentaBDPEs, hydroxylated DBDPE and nonaBDPE, and brominated phenyl acids) demonstrate biodegradation is very slow or recalcitrant in water (Appendix C, Table C-3).

The predicted transformation products do not contain functional groups expected to undergo hydrolysis, with the exception of brominated phenyl acids, which are recognized to have acyl halides. HYDROWIN (2010) predicts acyl halides react readily with water to yield the parent acid and hydrogen halide, with a half-life less than 10 minutes (or faster) (Table C-3).

The predicted half-life for atmospheric degradation of nona- through pentaBDPEs, hydroxylated DBDPE and nonaBDPE because of their reaction with the hydroxyl radical ranges from ~2 days to greater than 4 days (12-hr day, AOPWIN 2010) (Table C-3). AOPWIN (2010) also identifies the brominated phenyl acids to undergo ozone reaction, and predicts a half-life of 79.3 days.

Therefore, considering all model results, there is evidence that the predicted degradation of the debrominated BDPEs (penta through nonaBDPEs) and hydroxylated nonaBDPE, is slow and that the substances are persistent in water and air. Using an extrapolation ratio of 1:1:4 for a water: soil: sediment biodegradation half-life (Boethling et al. 1995), it is expected that nona- through pentaBDPEs, hydroxylated DBDPE and nonaBDPE, and brominated phenyl acids are also very persistent in soil and sediment.

8.3 Potential for bioaccumulation

Properties of the substance (i.e., log Kow, log Koa, molecular size and cross-sectional diameters) as well as empirical data (bioconcentration factor (BCF), biomagnification factor (BMF), trophic magnification factor (TMF) and bioaccumulation factor (BAF)) were considered for evaluation of DBDPE bioaccumulation potential.

Kelly et al. (2004) demonstrated that the absorption of ingested chemical in fish (and other wildlife) decreases with increasing log Kow starting at ~ 7 to 7.5 because the diffusion of hydrophobic substances across an unstirred water layer to the luminal membrane (i.e., gastrointestinal tract) of an organism is rate limiting for substances like DBDPE which have very high log Kow and low water solubility. Although Arnot and Gobas (2003a, 2004, 2006) do state that the log Kow domain of their model ranges from 1-9, there is considered to be insufficient empirical field evidence (i.e., BAFs) to support model estimates beyond log Kow~ 8.2. Therefore, the log Kow of 9.89 for DBDPE is considered out of the model domain for the mass-balance three trophic level BCFBAF model (Arnot and Gobas 2003a) and the (Q)SAR based Dimitrov et al. (2005) model. Importantly, lack of empirical BCF and BAF data for chemicals with log Kow greater than 8.2 does not allow for benchmarking of predicted results. Consequently, bioaccumulation of DBDPE was not modelled in this assessment. However, empirical analogue decaBDE was considered in the discussion, owing to its similar structure and physical-chemical properties.