Arctic Migratory Bird Initiative

Garry Donaldson keenly monitors shorebird work at what is often referred to as the End of the Earth. He and other biologists from Patagonia are closely observing shorebirds in an area that has never before been surveyed. As a biologist and one of the managers with Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Canadian Wildlife Service, he finds it fascinating and rewarding…and ultimately influential. “Based on the information we learned about local birds and the migrants from Canada, the Argentine government recently announced the establishment of the Patagonia National Park to protect them,” says Donaldson. “It doesn’t get much cooler than that.”

This is an example of how scientists and administrators across borders and continents can work together to help save various shorebird species and to address environmental concerns that are broader than most people realize.

As a group, shorebird species have declined by almost half. Most shorebirds migrate very long distances and are being affected by loss and alteration of wetlands, estuaries, deltas and mudflats at all stages of their journey, from their breeding grounds in Canada to stopover sites and wintering grounds throughout the Western Hemisphere. Their health tends to reflect their environment. They are the proverbial ‘global’ canaries in a coal mine.

“When we see problems out there, human beings need to pay attention…because we are affected many of the same factors.” Vicky Johnston, EC biologist and policy analyst.

“We depend on the same basic elements as they do…clean air, clean water, and bountiful land.” Reversing their decline will help us and the planet. Vicky Johnston sits on a steering committee for the Arctic Migratory Birds Initiative (AMBI) along with Donaldson. They’ve recently co-authored a new work plan with their international colleagues.

AMBI

AMBI is a project undertaken by the Arctic Council, through its Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna working group. The overall objective of AMBI is to improve the status and secure the long-term sustainability of declining Arctic breeding migratory bird populations. What makes AMBI new, says Johnston, is that it focuses not inward, but outward. “It takes the world to conserve arctic shorebirds. Effectively conserving them requires the cooperation of people, organizations and governments in many countries. We look not only at what we’re doing, but at what the United States and other countries are doing.”

Single Red Knot migration

Photo: © Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2015

Photo: © Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2015

Long description for Figure

Geolocator map of Red Knot migration showing Mingan, Quebec and Delaware Bay.

A Red Knot was captured on 26 May 2009 in New Jersey. It reached Mingan on 3 June after a 25-hour flight and stayed 2 days. From there it flew to Hudson Bay (short stop) and to the arctic, where he stayed for 43 days. It left the Arctic, made a short stop in Ungava Bay and arrived in Mingan on 3 Aug. It then flew 116 hours nonstop and reached Maranao (Brazil), where it spent the whole winter. The battery died on 31 Jan 2010. After that date, the bird was sighted again in Mingan in Aug 2010. The bird was re-trapped in Delaware Bay on 21 May 2011, when the data logger was retrieved.

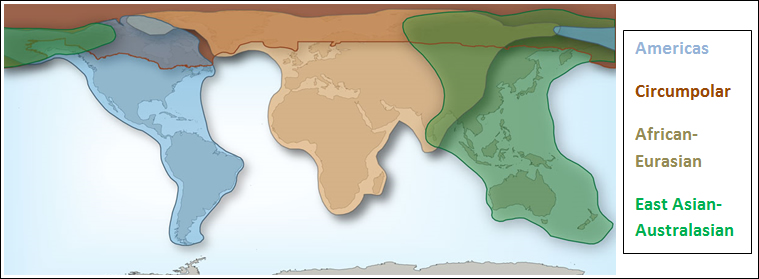

The AMBI steering committee, made up of members from Canada, the United States, Russia and Norway, has developed work plans that consider existing initiatives around the world and are organized around the flyways that Arctic migratory birds traverse throughout their life cycles.

AMBI flyways Each flyway sub-plan identifies high-priority species. Some priority species, like the Spoon-billed Sandpiper in East Asia, are endangered and AMBI is working with partners in China and Southeast Asia to alleviate the stressors on the species (loss of intertidal wintering habitat due to reclamation projects, and unsustainable hunting). For the Americas Flyway, two priority species are the Semipalmated Sandpiper and Red Knot, both of which are showing declines in population. Work to conserve the habitat of these species and to mitigate threats will also benefit dozens of species that share the same habitats.

Photo: © Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2015

Photo: © Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2015

Long description for Figure

Graphic showing AMBI flyways of Americas, Circumpolar, African-Eurasian and East Asian-Austalasian.

“The economies in these numerous countries within the flyways, the engagement of the right people in each, and the need for funding and legislation is a big and complicated puzzle one needs to work on in order to achieve conservation results” says Donaldson. “Thankfully, teasing through this complexity is not an impossible task and we have seen a number of successes over the years.”

The work plan has been welcomed by the Arctic Council Ministers and is now being implemented. You can read the work plan here.

Learn more about Shorebird monitoring in Canada.