Spotlight on science: The story that must be told - Mark Drever

Profile of Mark Drever, PhD

The story that must be told

The story goes back to October 2016, when the Nathan E. Stewart sank and 110,000 litres of diesel fuel spilled into the Pacific Ocean. During clean-up operations, several phalaropes were found dead on the beach, and Mark Drever was called in to identify the species. While helping study the carcasses, he noticed all the birds he examined had stomachs full of plastic. It was the beginning of a story that had to be told.

A leading expert in data analysis

Mark Drever is originally from South America. Passionate about being outside from an early age, the question that plagued him from the moment he arrived in Canada at 11 years old was, “Could I make a living working in nature?” His career path unfolded as he followed his curiosity: he began his university studies in zoology in Toronto, then did an internship in California on marsh birds and another in Hawaii, where he studied invasive species, such as rats and in bird colonies. His graduate studies led him to specialize in the impacts of climate change on birds and become a leading expert in data analysis. During his career, he has contributed to many scientific articles on numerous wildlife species.

Science that matters

Mark has held a research position at ECCC since 2010. “I love being a government scientist. I feel that I am an important resource not only in developing projects, but also because the scientific research I do with my team is useful and can support decision-making for the conservation of our ecosystems,” says Mark with obvious pride.

His favourite aspect of his work is turning a vague idea into a concrete project and into a scientific article. He takes great satisfaction from the fact that the scientific community can draw on his discoveries and publications as a kind of conservation guide that endures over time.

This is particularly true of his work on shorebirds and their exposure to plastic pollution. He contributed to the publication of an article entitled “Shorebirds Ingest Plastic Too: What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should Do Next”. In this study, Mark and his colleagues catalogued and reviewed available studies across the globe that examined plastic pollution in shorebirds. They then quantified relevant traits of species and their environments, to consider how the birds were being exposed to plastic pollution. After extensive research, they found that 53 percent of the birds had some form of plastic pollution in their body. The results also showed that species migrating across marine areas (either oceanic or coastal) are more affected by plastic pollution than species using continental flyways. Using the results of their analysis, Mark and his colleagues made recommendations on sampling protocols and future areas of research.

Alchemy to protect

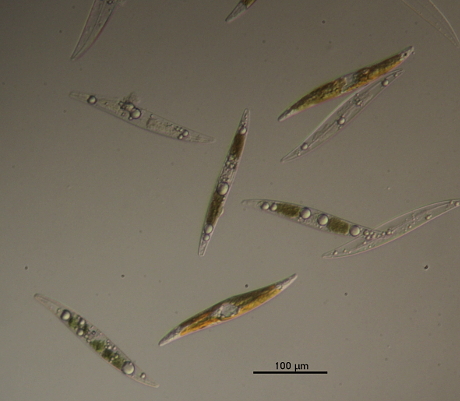

Another story that fascinates the researcher is the Roberts Banks shoreline ecosystem south of Vancouver and its seasonal visitors, the sandpipers. In late April/early May, a perfect alchemy occurs to create an ideal feeding oasis for them: the water becomes less salty due to seasonal snow melt from the mountains, nutrients flow in from the Fraser River, low tides expose the shoreline, temperatures rise, and the number of hours of sunshine increases. All these factors combine to create a rich intertidal biofilm—a thin, sticky, nutritious layer secreted mainly by microalgae at the base of the food chain. The sandpipers feed on this superfood during their spring migration.

It's great timing for this species. This microalgal bloom occurs precisely when sandpipers migrate through British Columbia on their way to their Arctic breeding grounds. But this fuel, full of nutrients essential for migration, could be threatened by how coastal industrial developments change the ways the river flows into the ocean. This is where Mark's research comes into focus. His findings can contribute evidence in the search for solutions, contribute knowledge to direct restoration measures, and help reduce the impacts of human activity on biodiversity.

Safety, research, and fun: a philosophy that is proving its worth

When asked what he likes best about his day-to-day work, Mark replies, “I love my team, having discussions with my colleagues on nitty-gritty subjects, and sharing ideas that take shape, in between our overly intellectual jokes!”

Fun is not the only part of his day; Mark considers it an essential component of his work. “My philosophy at work is, and will remain: safety-research-fun,” says Mark. His work involves a level of risk, as it takes place in environments that are sometimes dangerous. Physical safety is essential, but the researcher also stresses the importance of feeling psychologically and emotionally safe. “It is essential to develop a sense of belonging to our group, and to feel good within it. When we feel safe in these different aspects, we are ready to give our best,” explains Mark.

Scientific research is also at the heart of Mark's priorities. “We have to constantly remind ourselves of our scientific hypotheses and why we do our work. This is what keeps us going on cold, rainy days,” he says.

The third, but by no means least, essential component of daily life is fun. “That's what makes it all work! Work is so much more enjoyable when it's fun. I aim for a balance between these elements in my professional life,” Mark sums up with a laugh. With this philosophy he continues to tell the story that must be told, to achieve a healthy environment and protect the delicate ecological processes that maintain biodiversity around us.