Consultation on Amending the List of Species under the Species at Risk Act: Terrestrial Species – January 2016

- Introduction

- Addition of Species to the Species at Risk Act

- The Species at Risk Act Listing Process and Consultation

- Significance of the Addition of a Species to Schedule 1

- The List of Species Eligible for an Amendment to Schedule 1

- The COSEWIC Summaries of Terrestrial Species Eligible for Addition or Reclassification on Schedule 1

- Document Information

- Addition of Species to the Species at Risk Act

- The Species at Risk Act and the List of Wildlife Species at Risk

- COSEWIC and the assessment process for identifying species at risk

- Terms used to define the degree of risk to a species

- Terrestrial and aquatic species eligible for Schedule 1 amendments

- Comments solicited on the proposed amendment of Schedule 1

- Questions to guide your comments

- The Species at Risk Act Listing Process and Consultation

- The purpose of consultations on amendments to the List

- Legislative context of the consultations: the Minister’s recommendation to the Governor in Council

- Figure 1: The species listing process under SARA

- The Minister of the Environment’s response to the COSEWIC assessment: the response statement

- Normal and extended consultation periods

- Who is consulted, and how

- Role and impact of public consultations in the listing process

- Significance of the Addition of a Species to Schedule 1

- The List of Species Eligible for an Amendment to Schedule 1

- Status of the recently assessed species and consultation paths

- Providing comments

- Table 1: Terrestrial species recently assessed by COSEWIC eligible for addition to Schedule 1 or reclassification

- Table 2: Terrestrial species recently reassessed by COSEWIC (no consultations – species status confirmation)

- The COSEWIC Summaries of Terrestrial Species Eligible for Addition or Reclassification on Schedule 1

- Indexes

- Glossary

Please submit your comments by

May 4, 2016, for terrestrial species undergoing normal consultations

and by

October 4, 2016, for terrestrial species undergoing extended consultations.

For a description of the consultation paths these species will undergo, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry (SAR) website.

Please email your comments to the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Comments may also be mailed to:

Director General

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa ON

K1A 0H3

For more information on the Species at Risk Act, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry website.

The Government of Canada is committed to preventing the disappearance of wildlife species at risk from our lands. As part of its strategy for realizing that commitment, on June 5, 2003, the Government of Canada proclaimed the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Attached to the Act is Schedule 1, the list of the species provided for under SARA, also called the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species on Schedule 1 benefit from the protection of prohibitions and recovery planning requirements under SARA. Special Concern species benefit from its management planning requirements. Schedule 1 has grown from the original 233 to 521 wildlife species at risk.

The complete list of species currently on Schedule 1.

Species become eligible for addition to Schedule 1 once they have been assessed as being at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). The decision to add a species to Schedule 1 is made by the Governor in Council further to a recommendation from the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (ECC). The Governor in Council is the formal executive body that gives legal effect to decisions that then have the force of law.

COSEWIC is recognized under SARA as the authority for assessing the status of wildlife species at risk. COSEWIC comprises experts on wildlife species at risk. Its members have backgrounds in the fields of biology, ecology, genetics, Aboriginal traditional knowledge and other relevant fields. They come from various communities, including academia, Aboriginal organizations, governments and non-governmental organizations.

COSEWIC gives priority to those species more likely to become extinct, and then commissions a status report for the evaluation of the species’ status. To be accepted, status reports must be peer-reviewed and approved by a subcommittee of species specialists. In special circumstances, assessments can be done on an emergency basis. When the status report is complete, COSEWIC meets to examine it and discuss the species. COSEWIC then determines whether the species is at risk, and, if so, it then assesses the level of risk and assigns a conservation status.

The conservation status defines the degree of risk to a species. The terms used under SARA are Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened and Special Concern. Extirpated species are wildlife species that no longer occur in the wild in Canada but still exist elsewhere. Endangered species are wildlife species that are likely to soon become extirpated or extinct. Threatened species are likely to become endangered if nothing is done to reverse the factors leading to their extirpation or extinction. The term Special Concern is used for wildlife species that may become threatened or endangered due to a combination of biological characteristics and threats. Once COSEWIC has assessed a species as Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened or Special Concern, it is eligible for inclusion on Schedule 1.

For more information on COSEWIC, visit the COSEWIC website.

On October 6, 2015, COSEWIC sent to the Minister of the ECC its newest assessments of species at risk. Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is now consulting on changes to Schedule 1 to reflect these new designations for these terrestrial species. To see the list of the terrestrial species and their status, please refer to tables 1 and 2.

The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans conducts separate consultations for the aquatic species. For more information on the consultations for aquatic species, visit the Fisheries and Oceans Canada website.

The Minister of the ECC is conducting the consultations for all other species at risk.

Approximately 57% of the recently assessed terrestrial species at risk also occur in national parks or other lands administered by Parks Canada; Parks Canada shares responsibility for these species with ECCC.

The conservation of wildlife is a joint legal responsibility: one that is shared among the governments of Canada. But biodiversity will not be conserved by governments that act alone. The best way to secure the survival of species at risk and their habitats is through the active participation of all those concerned. SARA recognizes this, and that all Aboriginal peoples and Canadians have a role to play in preventing the disappearance of wildlife species from our lands. The Government of Canada is inviting and encouraging you to become involved. One way that you can do so is by sharing your comments concerning the addition or reclassification of these terrestrial species.

Your comments are considered in relation to the potential consequences of whether or not a species is included on Schedule 1, and they are then used to inform the drafting of the Minister’s proposed listing recommendations for each of these species.

The following questions are intended to assist you in providing comments on the proposed amendments to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk (see Table 1 for the list of species under consultation). They are not limiting, and any other comments you may have are welcome. We also encourage you to share descriptions and estimates of costs or benefits to you or your organization where possible, as well as to propose actions that could be taken for the conservation of these species.

Respondent information

Are you responding as an individual or representing a community, business or organization (please specify)?

Species benefit to people or the ecosystem

Do any or all of the species provide benefits to you or Canada’s ecosystems? If yes, explain how. What is the estimated value of these benefits? Values do not need to be monetary.

For example:

- Do any or all of the species provide benefits by supporting your livelihood, for example, through harvesting, subsistence or medicine?

- Do any or all of the species provide cultural or spiritual benefits, for example, recreation, sense of place or tradition? If yes, how?

- Do any or all of the species provide environmental benefits, for example, pollination, pest control or flood control? If yes, how?

Impact of your activities and mitigation

- Do any or all of the species provide benefits by supporting your livelihood, for example, through harvesting, subsistence or medicine?

- Do any or all of the species provide cultural or spiritual benefits, for example, recreation, sense of place or tradition? If yes, how?

- Do any or all of the species provide environmental benefits, for example, pollination, pest control or flood control? If yes, how?

Impacts of amending the List of Wildlife Species at Risk

Based on what you know about SARA and the information presented in this document, do you think that amending the List of Wildlife Species at Risk with the proposed listing (Table 1) would have no impact, a positive impact or a negative impact on your activities or the species? Please provide as much detail as possible.

For example:

- If any of your activities impact a species or its residence, would you have to avoid or adjust these activities to mitigate their impact? What would be the implications of such avoidance or mitigation?

- Do you think that listing the species would have cultural or social cost or benefits to you, your community or your organization?

- Do you think that listing the species would have economic costs or benefits to you, your community or your organization?

- Do you think that listing the species would have costs or benefits to the environment or Canada's ecosystems?

Additional information for small businesses

If you are responding for a small business, please provide the following details to help ECCC gather information to contribute to the required Small Business Lens analysis that forms part of the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement that will accompany any future listing recommendation.

- Are you an enterprise that operates in Canada?

- Do you engage in commercial activities related to the supply of services or property (which includes goods)?

- Are you an organization that engages in activities for a public purpose (e.g., social welfare or civic improvement), such as a provincial or municipal government, school, college/university, hospital or charity?

- Is your enterprise owned by a First Nations community?

- How many employees do you have?

- 0–99

- 100 or more

- What was your annual gross revenue in the last year?

- Less than $30,000

- Between $30,000 and $5 million

- More than $5 million

To ensure that your comments are considered in time, they should be submitted before the following deadlines.

For terrestrial species undergoing normal consultations, comments should be submitted by May 4, 2016.

For terrestrial species undergoing extended consultations, comments should be submitted by October 4, 2016.

To find out which consultation paths these species will undergo (extended or normal), please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Comments received by these deadlines will be considered in the development of the listing proposal.

Please email your comments to the Species at Risk Public Registry.

By regular mail, please address your comments to:

Director General

Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa ON

K1A 0H3

The addition of a wildlife species at risk to Schedule 1 of Species at Risk Act (SARA) facilitates providing for its protection and conservation. To be effective, the listing process must be transparent and open. The species listing process under SARA is summarized in Figure 1.

Long description for Figure 1

This figure explains the various steps of the listing process under the SARA. It is a flowchart. Its content is the following:

- The Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (ECC) receives species assessments from COSEWIC at least once a year.

- The competent departments undertake internal review to determine the extent of public consultation and socio-economic analysis necessary to inform the listing decision.

- Within 90 days of receipt of the species assessments prepared by COSEWIC, the Minister of the ECC publishes a response statement on the SARA Public Registry that indicates how he or she intends to respond to the assessment and, to the extent possible, provides timelines for action.

- Where appropriate, the competent departments undertake consultations and any other relevant analysis needed to prepare the advice for the Minister of the ECC.

- The Minister of the ECC forwards the assessment to the Governor in Council for receipt. This generally occurs within three months of posting the response statement, unless further consultation is necessary

- Within nine months of receiving the assessment, the Governor in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the ECC, may decide whether or not to list the species under Schedule 1 of SARA or refer the assessment back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration.

- Once a species is added to Schedule 1, it benefits from the applicable provisions of SARA.

When COSEWIC assesses a wildlife species, it does so solely on the basis of the best available information relevant to the biological status of the species. COSEWIC then submits the assessment to the Minister of the ECC, who considers it when making the listing recommendation to the Governor in Council. The purpose of these consultations is to provide the Minister with a better understanding of the potential social and economic impacts of the proposed change to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk, and of the potential consequences of not adding a species to the List.

The comments collected during the consultations inform the Governor in Council’s consideration of the Minister’s recommendations for listing species at risk. The Minister must recommend one of three courses of action. These are for the Governor in Council to accept the species assessment and modify Schedule 1 accordingly, not to add the species to Schedule 1, or to refer the species assessment back to COSEWIC for its further consideration (Figure 1).

After COSEWIC has completed its assessment of a species, it provides it to the Minister of the ECC. The Minister of the ECC then has 90 days to post a response on the Species at Risk Public Registry, known as the response statement. The response statement provides information on the scope of any consultations and the timelines for action, to the extent possible. It identifies how long the consultations will be (whether they are “normal” or “extended”) by stating when the Minister will forward the assessment to the Governor in Council. Consultations for a group of species are launched with the posting of their response statements.

Normal consultations meet the consultation needs for the listing of most species at risk. They usually take two to three months to complete, while extended consultations may take one year or more.

The extent of consultations needs to be proportional to the expected impact of a listing decision and the time that may be needed to consult. Under some circumstances, whether or not a species will be included on Schedule 1 could have significant and widespread impacts on the activities of some groups of people. It is essential that such stakeholders have the opportunity to inform the pending decision and, to the extent possible, to provide input on its potential consequences and to share ideas on how best to approach threats to the species. A longer period may also be required to consult appropriately with some groups. For example, consultations can take longer for groups that meet infrequently but that must be engaged on several occasions. For such reasons, extended consultations may be undertaken.

For both normal and extended consultations, once they are complete, the Minister of the ECC forwards the species assessments to the Governor in Council for the government’s formal receipt of the assessment. The Governor in Council then has nine months to come to a listing decision.

The consultation paths (normal or extended) for the terrestrial species listed in Table 1 will be announced when the Minister publishes the response statements. These will be posted by January 4, 2016, on the Species at Risk Public Registry.

No consultations will be undertaken for those species already on Schedule 1 and for which no change in status is being proposed (Table 2).

It is most important to consult with those who would be most affected by the proposed changes. There is protection that is immediately in place when a species that is Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened is added to Schedule 1 (for more details, see below, “Protection for listed Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species”). This immediate protection does not apply to species of Special Concern. The nature of protection depends on the type of species, its conservation status, and where the species is found. Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) takes this into account during the consultations; those who may be affected by the impacts of the automatic protections are contacted directly, others are encouraged to contribute through a variety of approaches.

Aboriginal peoples known to have species at risk on their lands, for which changes to Schedule 1 are being considered, will be contacted. Their engagement is of particular significance, acknowledging their role in the management of the extensive traditional territories and the reserve and settlement lands.

A Wildlife Management Board is a group that has been established under a land claims agreement and is authorized by the agreement to perform functions in respect of wildlife species. Some eligible species at risk are found on lands where existing land claims agreements apply that give specific authority to a Wildlife Management Board. In such cases, the Minister of the ECC will consult with the relevant board.

To encourage others to contribute and make the necessary information readily available, this document is distributed to known stakeholders and posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry. More extensive consultations may also be done through regional or community meetings or through a more targeted approach.

ECCC also sends notice of this consultation to identified concerned groups and individuals who have made their interests known. These include, but are not limited to, industries, resource users, landowners and environmental non-governmental organizations.

In most cases, it is difficult for ECCC to fully examine the potential impacts of recovery actions when species are being considered for listing. Recovery actions for terrestrial species usually have not yet been comprehensively defined at the time of listing, so their impact cannot be fully understood. Once they are better understood, efforts are made to minimize adverse social and economic impacts of listing and to maximize the benefits. SARA requires that recovery measures be prepared in consultation with those considered to be directly affected by them.

In addition to the public, ECCC consults on listing with the governments of the provinces and territories with lead responsibility for the conservation and management of these wildlife species. ECCC also consults with other federal departments and agencies.

The results of the public consultations are of great significance to informing the process of listing species at risk. ECCC carefully reviews the comments it receives to gain a better understanding of the benefits and costs of changing the List.

The comments are then used to inform the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS). The RIAS is a report that summarizes the impact of a proposed regulatory change. It includes a description of the proposed change and an analysis of its expected impact, which takes into account the results of the public consultations. In developing the RIAS, the Government of Canada recognizes that Canada’s natural heritage is an integral part of our national identity and history and that wildlife in all its forms has value in and of itself. The Government of Canada also recognizes that the absence of full scientific certainty is not a reason to postpone decisions to protect the environment.

A draft Order (see Glossary) is then prepared, providing notice that a decision is being taken by the Governor in Council. The draft Order proposing to list all or some of the species under consideration is then published, along with the RIAS, in the Canada Gazette, Part I, for a comment period of 30 days.

The Minister of the ECC will take into consideration comments and any additional information received following publication of the draft Order and the RIAS in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The Minister then makes a final listing recommendation for each species to the Governor in Council. The Governor in Council next decides either to accept the species assessment and amend Schedule 1 accordingly; or not to add the species to Schedule 1; or to refer the species assessment back to COSEWIC for further information or consideration. The final decision is published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, and on the Species at Risk Public Registry. If the Governor in Council decides to list a species, it is at this point that it becomes legally included on Schedule 1.

The protection that comes into effect following the addition of a species to Schedule 1 depends upon a number of factors. These include the species’ status under Species at Risk Act (SARA), the type of species and where it occurs.

Responsibility for the conservation of wildlife is shared among the governments of Canada. SARA establishes legal protection for individuals as soon as a species is listed as Threatened, Endangered or Extirpated, and, in the case of Threatened and Endangered species, for their residences. This applies to species considered federal species or if they are found on federal land.

Federal species include migratory birds, as defined by the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, and aquatic species covered by the Fisheries Act. Federal land means land that belongs to the federal government, and the internal waters and territorial sea of Canada. It also means land set apart for the use and benefit of a band under the Indian Act (such as reserves). In the territories, the protection for species at risk on federal lands applies only where they are on lands under the authority of the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (ECC) or the Parks Canada Agency.

Migratory birds are protected by the Migratory Birds Regulations, under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, which strictly prohibits the harming of migratory birds and the disturbance or destruction of their nests and eggs.

SARA’s protection for individuals makes it an offence to kill, harm, harass, capture or take an individual of a species listed as Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened. It is also an offence to damage or destroy the residence of one or more individuals of an Endangered or Threatened species or an Extirpated species whose reintroduction has been recommended by a recovery strategy. The Act also makes it an offence to possess, collect, buy, sell or trade an individual of a species that is Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened.

Species at risk that are neither aquatic nor protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, nor on federal lands, do not receive immediate protection upon listing under SARA. Instead, in most cases, the protection of terrestrial species on non-federal lands is the responsibility of the provinces and territories where they are found. The application of protections under SARA to a species at risk on non-federal lands requires that the Governor in Council make an order defining those lands. This can only occur when the Minister is of the opinion that the laws of the province or territory do not effectively protect the species. To put such an order in place, the Minister would then need to recommend the order be made to the Governor in Council. If the Governor in Council agrees to make the order, the prohibitions of SARA would then apply to the provincial or territorial lands specified by the order. The federal government would consult before making such an order.

Recovery planning results in the development of recovery strategies and action plans for Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened species. It involves the different levels of government responsible for the management of the species, depending on what type of species it is and where it occurs. These include federal, provincial and territorial governments as well as Wildlife Management Boards. Recovery strategies and action plans are also prepared in cooperation with directly affected Aboriginal organizations. Landowners and other stakeholders directly affected by the recovery strategy are consulted to the extent possible.

Recovery strategies must be prepared for all Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species. They include measures to mitigate the known threats to the species and its habitat and set the population and distribution objectives. Other objectives can be included, such as stewardship, to conserve the species, or education, to increase public awareness. Recovery strategies must include a statement of the time frame for the development of one or more action plans that will state the measures necessary to implement the recovery strategy. To the extent possible, recovery strategies must also identify the critical habitat of the species, which is the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of the species. If there is not enough information available to identify critical habitat, the recovery strategy includes a schedule of studies required for its identification. This schedule outlines what must be done to obtain the necessary information and by when it needs to be done. In such cases, critical habitat can be identified in a subsequent action plan.

Proposed recovery strategies for newly listed species are posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry to provide for public review and comment. For Endangered species, proposed recovery strategies are posted within one year of their addition to Schedule 1, and for Threatened or Extirpated species, within two years.

Once a recovery strategy has been posted as final, one or more action plans based on the recovery strategy must then be prepared. These include measures to address threats and achieve the population and distribution objectives. Action plans also complete the identification of the critical habitat where necessary and, to the extent possible, state measures that are proposed to protect it.

For terrestrial species listed on SARA Schedule 1 as Extirpated, Endangered or Threatened, the Minister of the ECC may authorize exceptions to the Act’s prohibitions, when and where they apply. The Minister can enter into agreements or issue permits only for one of three purposes: for research, for conservation activities, or if the effects to the species are incidental to the activity. Research must relate to the conservation of a species and be conducted by qualified scientists. Conservation activities must benefit a listed species or be required to enhance its chances of survival. All activities, including those that incidentally affect a listed species, its individuals, residences or critical habitat must also meet certain conditions. First, it must be established that all reasonable alternatives to the activity have been considered and the best solution has been adopted. Second, it must also be established that all feasible measures will be taken to minimize the impact of the activity on the listed species. And finally, it must be established that the activity will not jeopardize the survival or recovery of the species. Having issued a permit or agreement, the Minister must then include an explanation on the Species at Risk Public Registry of why the permit or agreement was issued.

While immediate protection under SARA for species listed as Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened does not apply to species listed as Special Concern, any existing protections and prohibitions, such as those provided by the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 or the Canada National Parks Act, continue to be in force.

For species of Special Concern, management plans are to be prepared and made available on the Species at Risk Public Registry within three years of a species’ addition to Schedule 1, allowing for public review and comment. Management plans include appropriate conservation measures for the species and for its habitat. They are prepared in cooperation with the jurisdictions responsible for the management of the species, including directly affected Wildlife Management Boards and Aboriginal organizations. Landowners, lessees and others directly affected by a management plan will also be consulted to the extent possible.

On October 6, 2015, COSEWIC submitted 22 assessments of species at risk to the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change (ECC) for species that are eligible to be added to Schedule 1 of Species at Risk Act (SARA). Nineteen of these are terrestrial species, and 3 are aquatic species. COSEWIC also reviewed the classification of species already on Schedule 1, in some cases changing their status. Two terrestrial species are now being considered for down-listing on SARA (to a lower risk status) and 4 terrestrial species are now being considered for up-listing on SARA (to a higher risk status). In all, 25 terrestrial species that are eligible to be added to Schedule 1 or to have their current status on Schedule 1 changed are included in this consultation (Table 1).

One of these terrestrial species, the Spiked Saxifrage, was originally assessed by COSEWIC as Threatened in May 2013. However, COSEWIC advised the Minister that it must reassess this species, due to new information that was not available at the time of the assessment. This was communicated to Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) when the December 2013 consultation document was already in production and, as a consequence, the Spiked Saxifrage was included in the document, but no consultations were held. COSEWIC reassessed the Spiked Saxifrage in May 2015 as Special Concern, and the species is included in the current consultation document as a terrestrial species eligible for an addition to Schedule 1 of SARA.

COSEWIC also submitted the reviews of species already on Schedule 1, confirming their classification. Twenty of these reviews were for terrestrial species. These species are not included in the consultations because there is no regulatory change being proposed (Table 2).

For more information on the consultations for aquatic species, visit the Fisheries and Oceans Canada website at www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca.

The involvement of Canadians is integral to the listing process, as it is to the ultimate protection of Canadian wildlife. Your comments matter and are given serious consideration. ECCC will review all the comments that it receives by the deadlines provided below.

Comments for terrestrial species undergoing normal consultations must be received by May 4, 2016.

Comments for terrestrial species undergoing extended consultations must be received by October 4, 2016.

Most species will be undergoing normal consultations. For the final consultation paths, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry.

after January 4, 2016.

For more details on submitting comments, see the section “Comments solicited on the proposed amendment of Schedule 1” of this document.

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | Eastern Box Turtle | Terrapene carolina | ON |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Plants | Limber Pine | Pinus flexilis | BC AB |

| Vascular Plants | Tall Beakrush | Rhynchospora macrostachya | NS |

| Vascular Plants | Fascicled Ironweed | Vernonia fasciculata | MB |

| Molluscs | Broad-banded Forestsnail | Allogona profunda | ON |

| Molluscs | Proud Globelet | Patera pennsylvanica | ON |

| Birds | Black Swift | Cypseloides niger | BC AB |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lichens | Black-foam Lichen | Anzia colpodes | ON QC NB NS |

| Vascular Plants | Griscom’s Arnica | Arnica griscomii ssp. griscomii | QC NL |

| Arthropods | Sable Island Sweat Bee | Lasioglossum sablense | NS |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

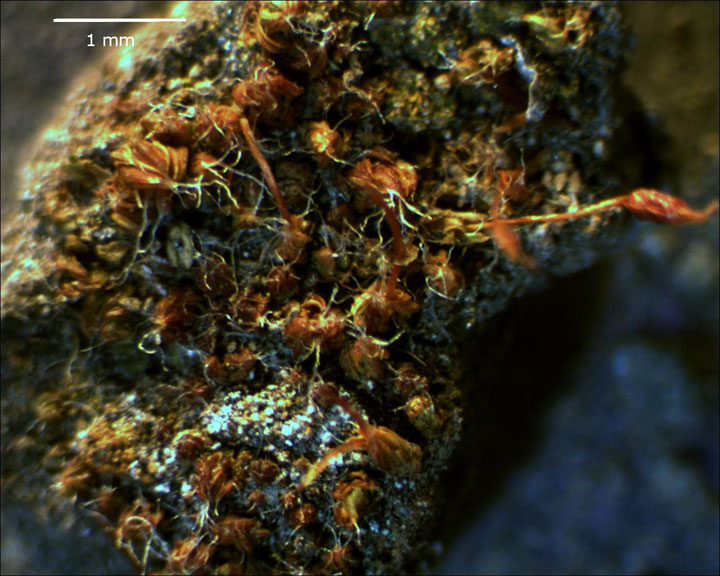

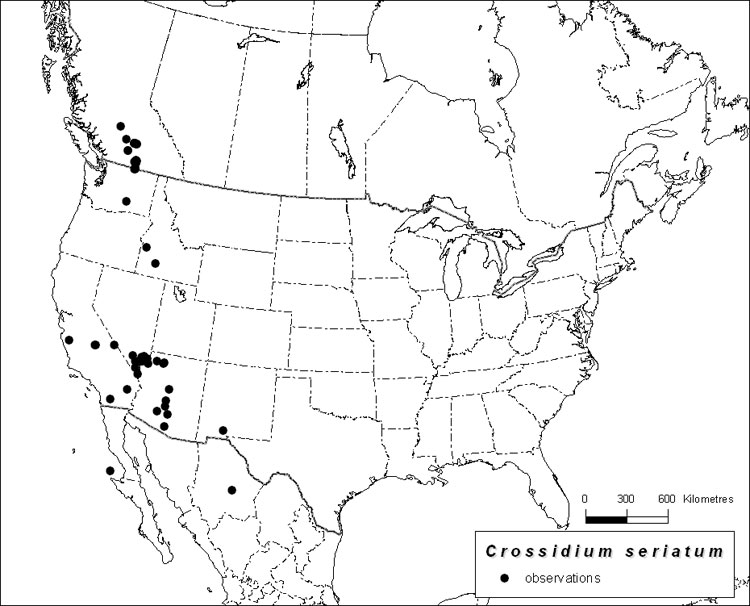

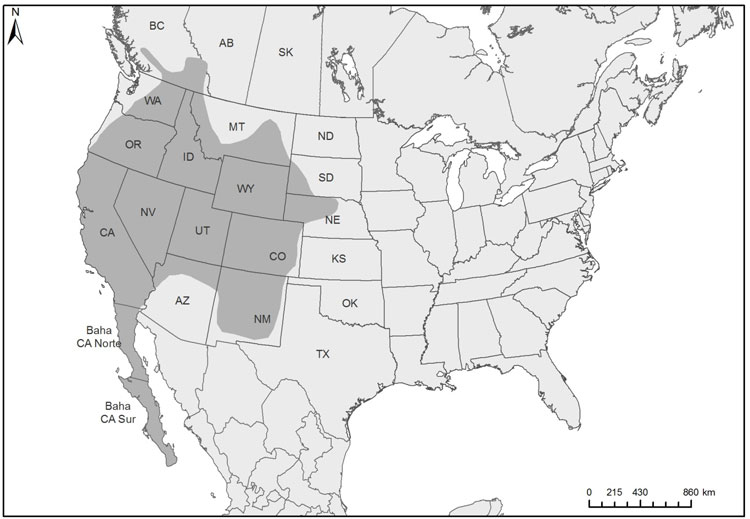

| Mosses | Tiny Tassel | Crossidium seriatum | BC |

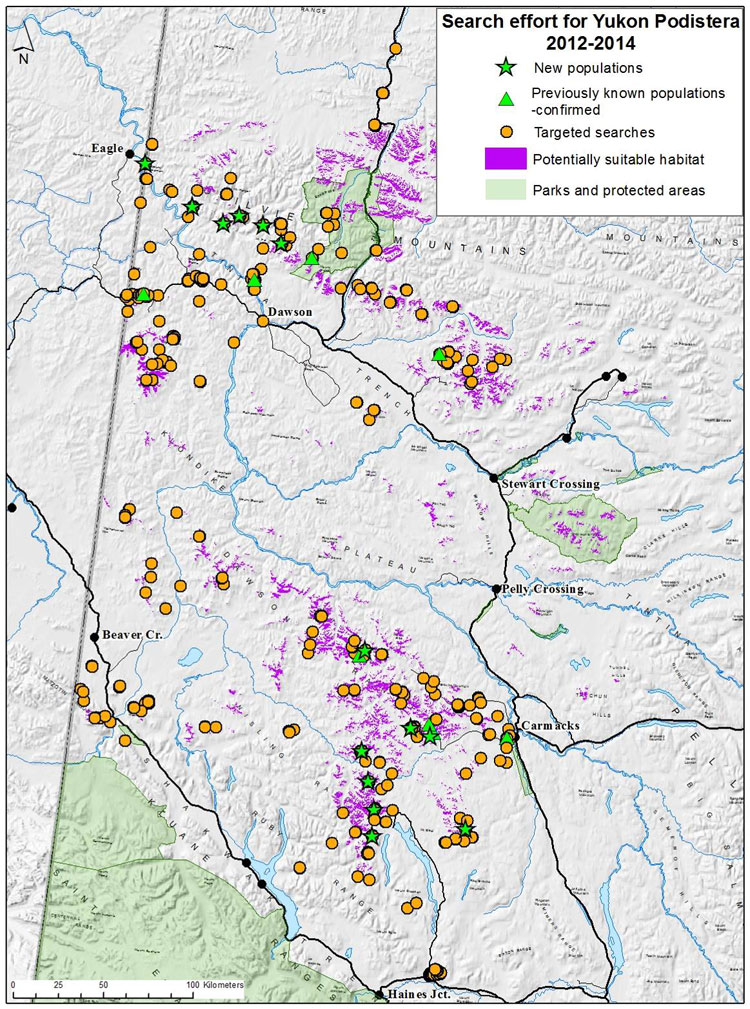

| Vascular Plants | Spiked SaxifrageFootnotea | Micranthes spicata | YT |

| Vascular Plants | Yukon Podistera | Podistera yukonensis | YT |

| Arthropods | Vivid Dancer | Argia vivida | BC AB |

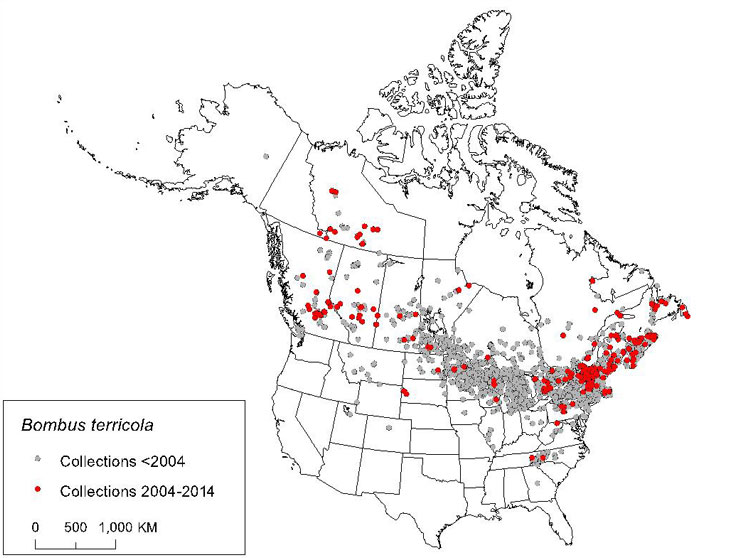

| Arthropods | Yellow-banded Bumble Bee | Bombus terricola | YT NT BC AB SK MB ON QC NB PE NS NL |

| Birds | Cassin's Auklet | Ptychoramphus aleuticus | BC Pacific Ocean |

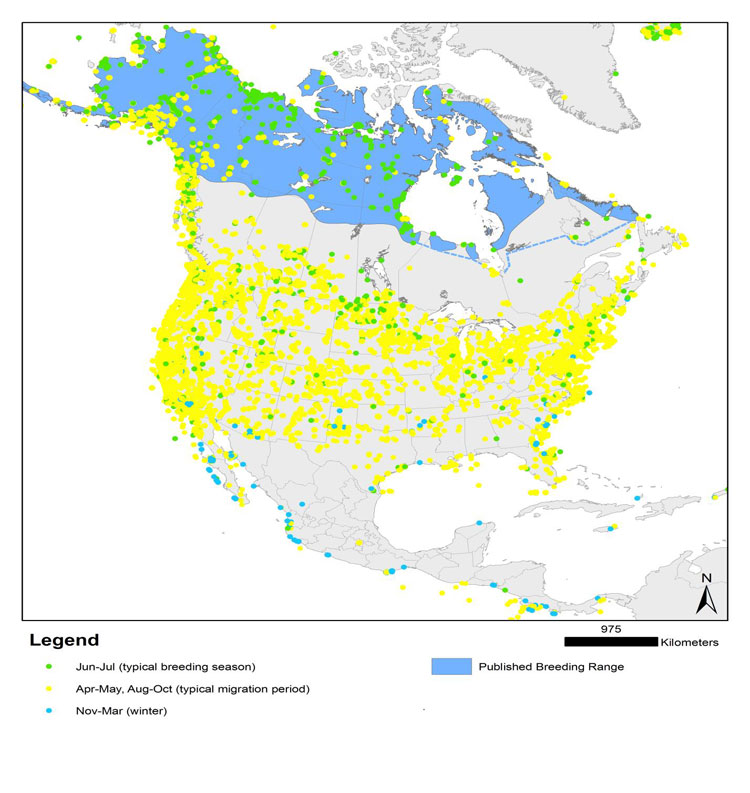

| Birds | Red-necked Phalarope | Phalaropus lobatus | YT NT NU BC AB SK MB ON QC NB PE NS NL Pacific Ocean Arctic Ocean Atlantic Ocean |

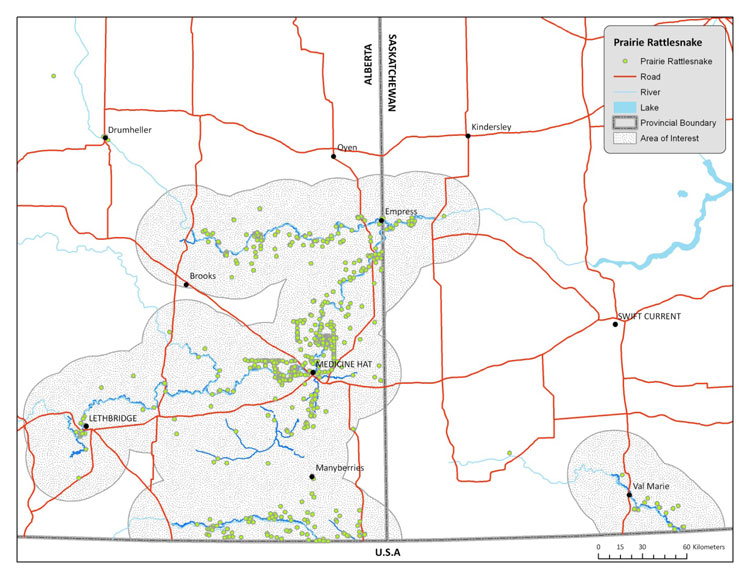

| Reptiles | Prairie Rattlesnake | Crotalus viridis | AB SK |

| Mammals | Caribou (Newfoundland population) | Rangifer tarandus | NL |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Plants | Phantom Orchid | Cephalanthera austiniae | BC |

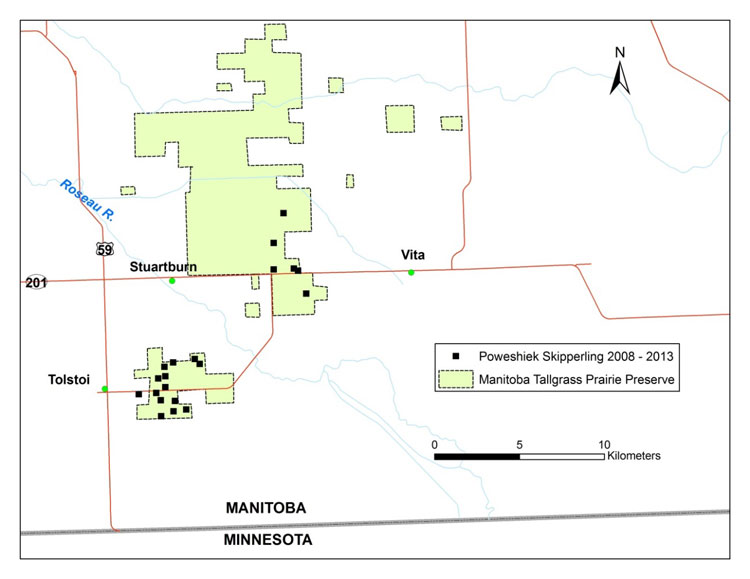

| Arthropods | Poweshiek Skipperling | Oarisma poweshiek | MB |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Plants | Blue Ash | Fraxinus quadrangulata | ON |

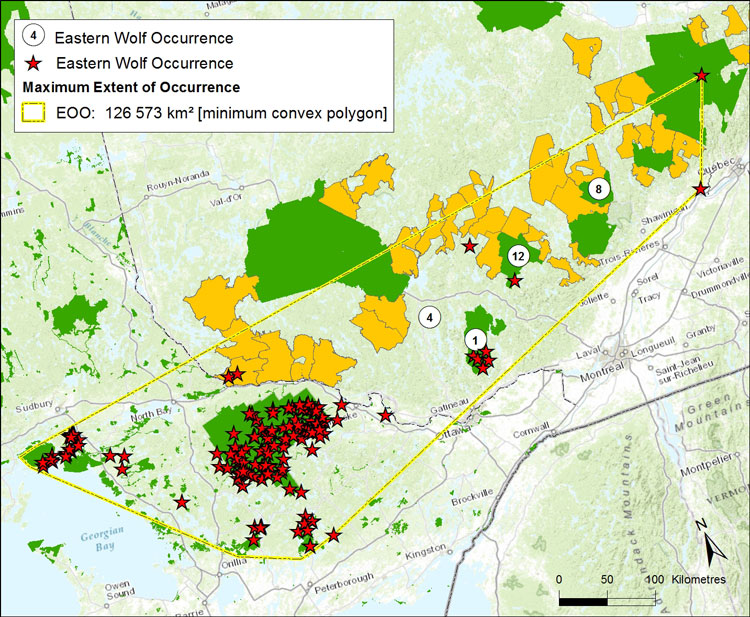

| Mammal | Eastern Wolf | Canis sp. cf. lycaon | ON QC |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular Plants | Small White Lady's-slipper | Cypripedium candidum | MB ON |

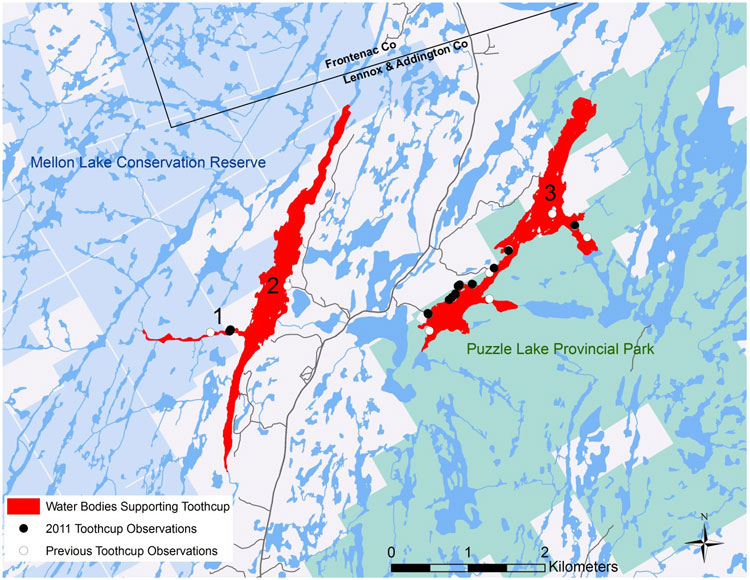

| Vascular Plants | Toothcup (Great Lakes Plains population)Footnoteb | Rotala ramosior | ON |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lichens | Boreal Felt Lichen (Atlantic population) | Erioderma pedicellatum | NB NS |

| Vascular Plants | Red Mulberry | Morus rubra | ON |

| Vascular Plants | Toothcup (Southern Mountain population)Footnotec | Rotala ramosior | BC |

| Arthropods | White Flower Moth | Schinia bimatris | MB |

| Arthropods | Ottoe Skipper | Hesperia ottoe | MB |

| Reptiles | Spotted Turtle | Clemmys guttata | ON QC |

| Mammals | Townsend's Mole | Scapanus townsendii | BC |

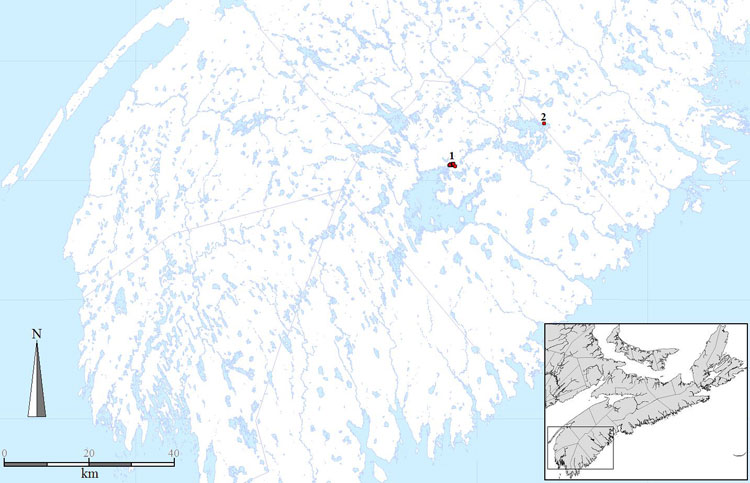

| Mammals | Caribou (Atlantic-Gaspésie population) | Rangifer tarandus | QC |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | Western Rattlesnake | Crotalus oreganus | BC |

| Mammals | Caribou (Boreal population) | Rangifer tarandus | YT NT BC AB SK MB ON QC NL |

| Mammals | Ermine haidarum subspecies | Mustela erminea haidarum | BC |

| Taxon | Species | Scientific Name | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lichens | Boreal Felt Lichen (Boreal population) | Erioderma pedicellatum | NL |

| Lichens | Frosted Glass-whiskers (Atlantic population) | Sclerophora peronella | NS |

| Mosses | Banded Cord-moss | Entosthodon fascicularis | BC |

| Mosses | Columbian Carpet Moss | Bryoerythrophyllum columbianum | BC |

| Mosses | Twisted Oak Moss | Syntrichia laevipila | BC |

| Amphibians | Northern Red-legged Frog | Rana aurora | BC |

| Reptiles | Western Skink | Plestiodon skiltonianus | BC |

| Birds | Ancient Murrelet | Synthliboramphus antiquus | BC Pacific Ocean |

| Mammals | Spotted Bat | Euderma maculatum | BC |

The following section presents a brief summary of the reasons for the COSEWIC status designation of individual species, and their biology, threats, distribution and other information. For a more comprehensive explanation of the conservation status of an individual species, please refer to the COSEWIC status report for that species, also available on the Species at Risk Public Registry.

or contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa ON

K1A 0H3

Photo: © Terry Gray

Long description for Figure 1

Long Description: Photo of a Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) on its nest. The plumage is almost entirely black.

Reason for designation

Canada is home to about 80% of the North American population of this bird species. It nests in cliff-side habitats (often associated with waterfalls) in British Columbia and western Alberta. Like many other birds that specialize on a diet of flying insects, this species has experienced a large population decline over recent decades. The causes of the decline are not well understood, but are believed to be related to changes in food supply that may be occurring at one or more points in its life cycle. The magnitude and geographic extent of the decline are causes for conservation concern.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Black Swift is the largest swift in North America. Canada is home to over 80% of the population. It has an almost entirely blackish plumage, has long, pointed wings and is the only North American swift with a notched tail. As well as having many unusual life history traits compared to other landbird species (single egg clutch, extended maturation, remote waterfall and cave-nesting sites), the Black Swift may be a sensitive indicator for climate change. This is because its waterfall nesting sites are likely to be impacted by decreased snow pack and glacial melt. The Black Swift feeds exclusively on flying insects.

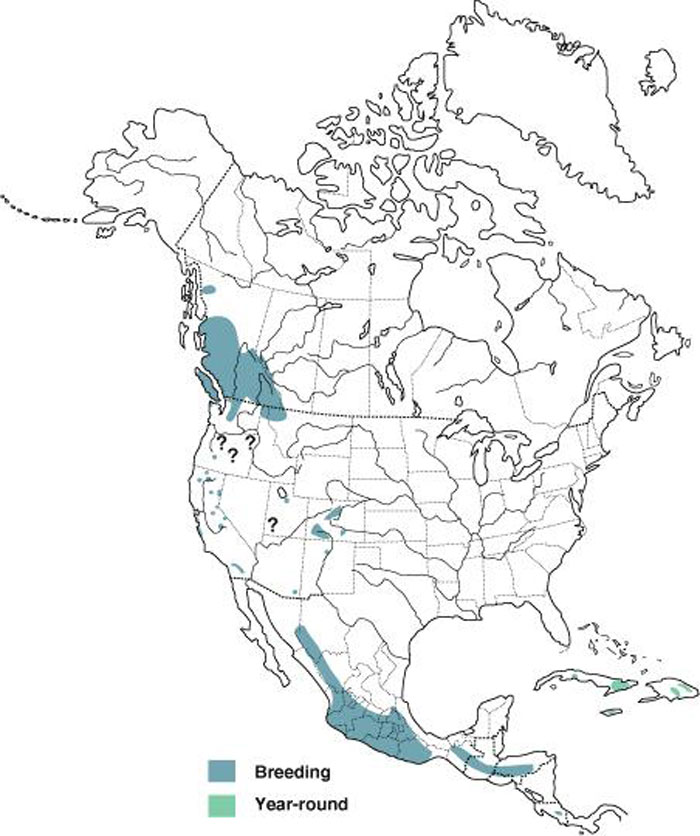

Distribution

The global breeding range of the subspecies that occurs in Canada shows a disjunct distribution: a northern range (from southeastern Alaska, northwestern British Columbia and southwestern Alberta, south through northwestern Montana, northern Idaho, and northern Washington), and scattered populations south of this (in Oregon, California, Utah, Colorado, northern New Mexico, southeastern Arizona). This subspecies also breeds in Mexico as far south as Oaxaca and Veracruz and possibly other areas in Mexico. Other subspecies occur elsewhere in Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America.

Source: Map courtesy of “Birds of North America Online", maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY.

Long description for Map 1

Map illustrating the breeding and non-breeding range of the Black Swift in North America, Central America, and the Caribbean. The map shows a disjunct distribution, with a large breeding range in British Columbia and Alberta (extending into adjacent U.S. states), scattered subpopulations south of this, and then a continuous large range in Mexico, and through Central America, with scattered permanent localized resident populations in the West Indies.

Habitat

Often foraging at high altitude, Black Swifts fly over open country and forests in mountainous areas and lowlands, pursuing aerial insects. They nest near or behind waterfalls and in caves, located in canyons and sometimes on sea cliffs. Their nest sites are characterized by presence of flowing water, high relief, inaccessibility, darkness, and an unobstructed flight path.

Biology

Little is known about the biology of the Black Swift. The species is believed to be monogamous and long-lived. The oldest known individual was 16 years old. Age at first breeding is unknown but, given other life history characteristics, may be from 3-5 years. It is one of only two landbirds in Canada to lay a single egg clutch, and has an extremely long fledgling period (7 weeks). Canadian birds migrate south, likely to spend the winter in South America. However, the precise winter range of Canadian birds is unknown.

Population Sizes and Trends

The population size of the borealis subspecies in Canada is hard to determine, but is estimated at 15,000 to 60,000 mature individuals. Canada is believed to harbour about 81% of the North American population, the vast majority of which occurs in British Columbia. Less than 0.1% of the North American population occurs in Alberta.

Across their range in Canada and the United States, Black Swifts are showing negative population trends. The Canadian population appears to have declined by more than 50% over the 40-year period between 1973 and 2012. A generation time ranging between 6.25 and 16.5 years yields a cumulative population loss of -72% to -96% over three generations, with expert opinion suggesting that the value is most likely around -89% (average annual trend of -6.5% over 33 years). The rate of decline has lessened in recent years; the 10-year short-term trend (2002-2012) estimate was -4.6% per year, which is equivalent to an overall decline of about 38% over the most recent decade. During this period, there was a 25% probability that the population declined by >50%, and a 45% probability that it declined by 25-50%.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The most important threats to the Black Swift are largely unknown but are believed to

be: 1) airborne pollutants that reduce aerial insect food availability and/or potentially cause reproductive failure in swifts; and 2) climate change that could reduce stream flow at nest sites or lead to temporal mismatches between aerial arthropod phenology and the swift’s breeding cycle. Other threats such as problematic native species, logging, annual and perennial non-timber crops, livestock farming and ranching, hydroelectric dams and water management, and recreational activities were considered as being negligible.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

The Black Swift is considered a continental Watch List species by Partners in Flight and is listed as Special Concern by many bird conservation region and state bird conservation plans. IUCN lists the species as Least Concern and it is a bird of conservation concern in the United States. According to NatureServe, it is considered apparently secure globally and apparently nationally secure in Canada and the United States, but these assessments are dated. It is listed as critically imperilled, imperilled or vulnerable in some states, but apparently secure in British Columbia and unranked in Alberta.

Photo: © David Richardson

Long description for Figure 2

Photo of a patch of the Black-foam lichen (Anzia colpodes), a foliose lichen with thalli that form greenish-grey rosettes. The solid thallus lobes rest on a dense, thick spongy cushion of black fungal filaments (the hypothallus). Stout but sparse rhizines grow from the lower cortex to the substrate, through the spongy hypothallus.

Reason for designation

In Canada, this lichen is at the northern edge of its range, and is known from Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. It appears to be extirpated from Ontario and Quebec and has not been seen in New Brunswick for about a decade. It occurs on sites dominated by mature deciduous trees with high humidity and moderate light. In Nova Scotia, this lichen is widespread but not common. The reasons for its decline are not clear. The main current threat is deforestation. Additional threats may include grazing by molluscs and climate change.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Black-foam Lichen, Anzia colpodes, is a leafy lichen that grows as greenish grey rosettes up to 20 cm across on the trunks of deciduous trees. The 1-2 mm wide solid lobes rest on a thick spongy black tissue made of fungal filaments. The reddish-brown fruit bodies on the upper surface contain sacks that are unusual in containing a large number of tiny spores that provide its only means of reproduction.

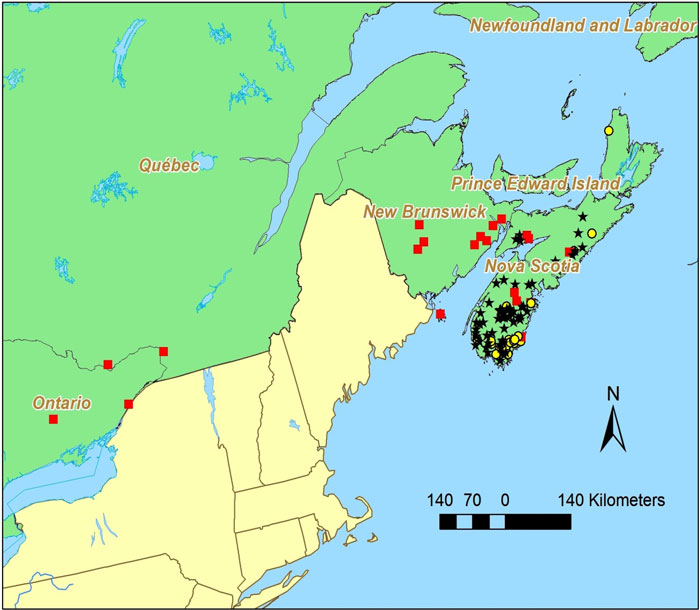

Distribution

The Black-foam Lichen is thought to be endemic to North America, although there is one report of its being found in eastern Russia. In the USA, it has been collected in the Appalachian Mountains from Georgia to Maine, but also on the Ozark Plateau and in Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan. In Canada, this lichen is growing at the northern end of its distribution range and has been found in Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Recent surveys indicate that the Black-foam Lichen no longer occurs in the first two of these provinces and has not been recorded in New Brunswick in the last decade. This lichen is widespread but not common in Nova Scotia.

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Black-foam Lichen in Canada.

Long description for Map 2

Map of the distribution of Anzia colpodes in Canada, where the species is known historically from four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The map indicates occurrences currently known to be extant from fieldwork carried out for this report, occurrences that were found before 1995 and were not revisited, and revisited occurrences where the lichen was absent.

Habitat

The Black-foam Lichen grows on the trunks of mature deciduous trees growing on level or sloped land where high humidity is supplied by nearby wetlands, lakes or streams. The most common host is Red Maple but it also occurs on White Ash, Sugar Maple, Red Oak and very occasionally on other species.

Biology

Fruit bodies are frequent on the Black-foam Lichen and provide the only means of reproduction. The spores ejected from the fruit bodies need to land on a host tree trunk and encounter a compatible green alga. The algae become enveloped by fungal strands and eventually these grow into visible lichen. The generation time for this lichen is probably around 17 years. Unlike many other leafy lichens which grow on tree trunks, the Black-foam Lichen has no specialized vegetative propagules to provide a means of asexual reproduction.

Population Sizes and Trends

The Black-foam Lichen seems always to have been less common in Ontario and Québec and in the adjacent US states than in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. In the first two provinces there are only four records for this lichen; all the sites were revisited, but it was not found. In New Brunswick there are 12 records for this lichen, and it was not found again during searches at six of these sites done in 2013.

In Nova Scotia, the Black-foam Lichen is not common, but it is widespread. Thirty-five occurrences have been documented in the province since 1995. The population was enumerated at the nine occurrences where the Black-foam Lichen was found during the fieldwork for this status report. On the basis of the enumeration, it is estimated that the total population of this lichen in Canada could be as high as 3,700 individuals, with almost all being in Nova Scotia. In addition, the lichen was no longer present at three of the seven post-2006 revisited occurrences, indicating a ~40% decline over the last ten years.

Threats and Limiting Factors

In Ontario and Québec, the main threat to the Black-foam Lichen appears to be habitat disturbance. The few sites where it was recorded historically have been subject to the spread of suburbia, building sites, highways and trails that have removed the forest where this lichen was once found. Other likely threats in these provinces are air pollution and changing weather patterns. The cause of the disappearance of the Blackfoam Lichen from these provinces is uncertain, but it is significant that declines have also been observed in adjacent states of the USA.

In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, the main current threat is harvesting of older hardwood forests. The grazing impact of introduced molluscs is another threat with an unknown impact. The Black-foam Lichen with its low content of secondary substances lacks anti-herbivory effectiveness. Changing weather patterns are thought to have enhanced the spread and impact of grazing molluscs and may have affected the ability of this lichen to reproduce. Its tiny spores have little stored energy to provide the fungal germ tube with the means to search extensively for a compatible algal partner, a process required at every generation. Furthermore, its stout but sparse holdfasts which fasten small thalli firmly to the tree bark loosen as the lichen grows, making it vulnerable to removal by wind, rain or animals.

Over the longer term, climate change and alterations of weather pattern are predicted to result in reduced precipitation or enhanced evaporation. These are likely to affect the survival of the Black-foam Lichen as this species requires the right combination of climate and forest stand features. It is largely limited to growing on trees close to water bodies that include swamps, swamp margins, lakes and streams.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

The Black-foam Lichen is listed by NatureServe Global Status as G3 (vulnerable)/ G5 (secure). The Rounded Global Status is G4 - Apparently secure. In the USA it has a national status of NNR (unranked). In Michigan, North Carolina and Pennsylvania it is SNR (not yet assessed), but in Wisconsin it is SX (presumed extirpated) and is also thought to be extirpated in Ohio. In Canada, the Black-foam Lichen is ranked by NatureServe as NNR (unranked). In Ontario it is SH (possibly extirpated) and in Québec it is SNR (not yet assessed).

Currently the Black-foam Lichen has no legal protection or status in Canada, although a number of occurrences in Nova Scotia are protected as they occur in provincially protected wilderness areas or National Parks.

Photo: © John D. Ambrose

Long description for Figure 3

Photograph of Blue Ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata) trees on a rocky cliffside. The trunk of the Blue Ash can be straight or irregular, and the crown is narrow, small and rounded. The bark is light-coloured, reddish-grey or tan-grey, and scaly. The leaves are compound and opposite with seven leaflets, and the twigs have square sides with four distinctive corky ridges or wings.

Reason for designation

This tree has a restricted distribution in the Carolinian forests of southwestern Ontario. Small total population size in a fragmented landscape, combined with increasing potential impact from browsing by White-tailed Deer and infestation by the invasive Emerald Ash Borer, place the species at risk of further declines at most sites. In addition, mature trees on Middle Island are threatened by impacts of nesting Double-crested Cormorants. These factors resulted in a change in status from Special Concern to Threatened.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Blue Ash is a medium-sized tree, roughly 20 m in height and up to 80 cm in diameter, and is one of six ash species native to Canada. The trunk can be straight or irregular and the crown is narrow, small and rounded. Trees have light-coloured, reddish-grey or tan-grey, scaly bark. The leaves are compound and opposite with seven (5-11) leaflets and the twigs have square sides with four distinctive corky ridges or wings (hence the scientific epithet quadrangulata). Clusters of small flowers that lack petals are produced in spring, as new leaves are expanding. The fruits are single-seeded samaras that are usually twisted, with a notch in the broad wing. A distinctive feature is the retention of dead lower branches, giving the tree an untidy appearance. The inner bark contains a sticky substance that turns blue upon exposure to air (hence the species’ common name).

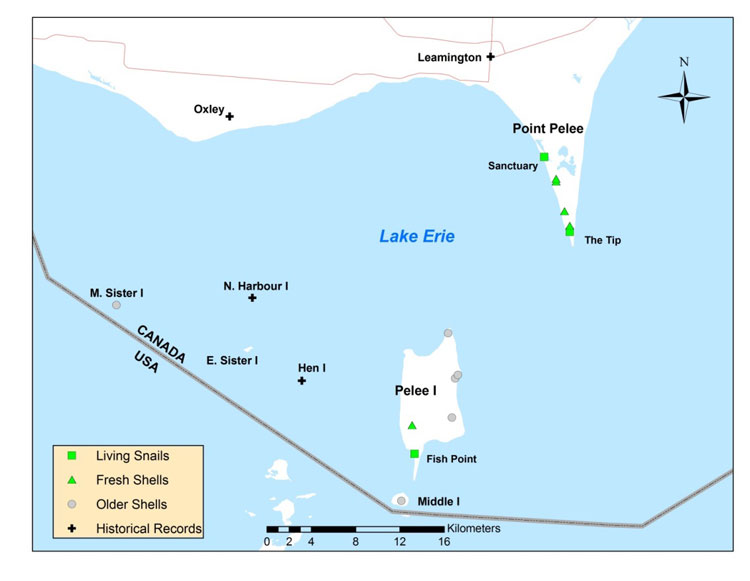

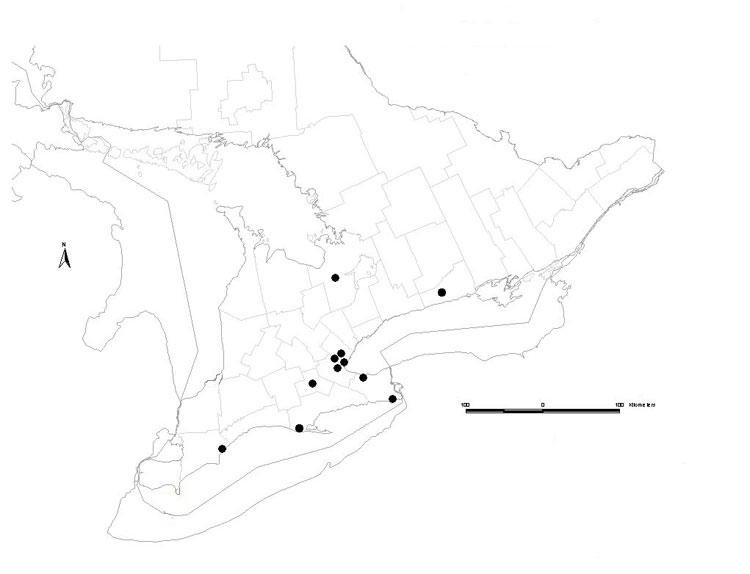

Distribution

Blue Ash has a restricted distribution in Canada and occurs only in southwestern Ontario in the counties and municipalities of Elgin, Middlesex, Lambton, Chatham-Kent and Essex. It is found at Point Pelee, Peche Island at the mouth of the Detroit River, and the Erie Islands, as well as in river valleys along the Thames River, Sydenham River, and Catfish Creek. Blue Ash is more widely distributed in the United States, and ranges from Ohio south into Alabama, Georgia and Arkansas and west to Wisconsin, Oklahoma and Kansas.

Source: COSEWIC 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Blue Ash in Canada.

Long description for Map 3

Map of the distribution of extant Blue Ash subpopulations in Ontario. The Blue Ash occurs at Point Pelee, Peche Island, the islands in Lake Erie, and valleys along the Thames River, Sydenham River, and Catfish Creek.

Habitat

Blue Ash grows in a variety of habitats and soil types. In Ontario, it is found in three distinctive habitat types. They include floodplains and river valleys where Blue Ash grows in rich soils in association with a variety of other tree species; shallow soils on alvar and limestone on the Lake Erie Islands; and stabilized beaches at Point Pelee National Park, and Fish Point on Pelee Island. All of these habitats have declined in area and quality over the last 100 years. While the effects of habitat fragmentation on Blue Ash have not been assessed, it is expected that fragmentation will result in ecological degradation and perhaps genetic degradation over a longer timeframe, which may contribute to decreasing the likelihood of persistence of subpopulations.

Biology

Unlike other ash species, flowers of Blue Ash include both male and female reproductive structures. The species reproduces by seed and there is no evidence of clonal spread. Blue Ash trees can live up to 300 years (typically 150 to 200 years) and age of maturity (fruiting age) is approximately 25 years. Seed crops are produced every 3-4 years and seeds are dispersed by wind. Most seeds likely disperse within 10 m of the parental tree, but a small number of seeds may travel up to 200 m. Seeds may be dispersed over larger distances by water or animal transport.

Population Sizes and Trends

In 1983, 14 sites with Blue Ash trees were reported within four regions of southwestern Ontario. By 2000, additional searches resulted in recognition of a total of 37 extant subpopulations. In 2001, an additional 19 sites were documented; combining with the 37 subpopulations above this gives a total of 56 sites. The total Canadian population was estimated at fewer than 1000 mature trees in 2001. Fieldwork conducted during 2012/2013 suggests that Blue Ash is more abundant than previously documented. Information on about half of the known sites was collated (n=26) and 1806 trees were counted. Of these trees, 708 (39%) were considered mature (capable of bearing seed). Large numbers of seedlings and saplings were observed at some sites, especially at Point Pelee National Park, and the McAlpine Tract on the Sydenham River.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Since the last status assessment, the potential for deer browsing to impact recruitment and establishment of Blue Ash has emerged as a greater concern than previously noted. Although a few surveyed sites had very large numbers of seedlings and young trees, at many surveyed sites there was little evidence of regeneration suggesting that deer browsing could be preventing establishment of young trees. In addition, the invasive alien beetle Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) has emerged as a new threat to native ash species, including Blue Ash. First detected in North America in 2002, EAB has since spread rapidly. During surveys in 2012/2013, signs of EAB were found at 45.8% (11 out of 26) of the sites and in 70 (3.7%) Blue Ash trees. Although few Blue Ash trees appear to have been killed so far by EAB (0.26% of surveyed trees) and they appear to show resistance, it is unknown whether the impact of EAB will increase in the future. Additional threats to Blue Ash include forest management practices that may include direct cutting of Blue Ash trees because of misidentification by landowners, or authorities – either deliberately or because of EAB related management; alteration to natural disturbance regimes through fire suppression and water management; impacts of livestock farming and ranching including grazing and trampling in riparian habitats; recreational activities (e.g., all-terrain vehicles in local areas), which could impact regeneration through trampling; and, at Middle Island, nitrification of soils and damage to trees from Double-crested Cormorant guano and nesting activities.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

COSEWIC first assessed Blue Ash as Special Concern in April 1983, confirmed same status in November 2000, and the wildlife species was last assessed Threatened in November 2014. Blue Ash is listed as ‘Special Concern’ under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, 2003 and under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. Although Blue Ash is considered globally secure (G5) and nationally secure in the United States (N5), it is considered vulnerable (N3) in Canada and is not ranked in Ontario (S3?). Blue Ash is listed as critically imperiled (S1) in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Iowa, as imperiled (S2) in Kansas and Mississippi, and vulnerable (S3) in Virginia. It is listed as critically imperiled to imperiled (S1S2) in Georgia and as imperiled to vulnerable (S2S3) in Oklahoma. It is not ranked (SNR) in all other states where it occurs.

Photo: © Allan Harris

Long description for Figure 4

Photo of a Broad-banded Forestsnail, Allogona profunda, shell showing the low spire. The shell is pale yellow with pale brown bands, and the surface is sculptured with fine grooves oriented across the whorls.

Reason for designation

In Canada, this large terrestrial snail is known to exist only in Point Pelee National Park and on Pelee Island. An overabundance of nesting Double-crested Cormorants has most likely led to the loss of subpopulations on some small Lake Erie islands since the early 1980s; historical losses of woodlands and forests also occurred on the mainland and Pelee Island. Major continuing threats are from recreational activities and shoreline erosion. A possible threat is predation by introduced Wild Turkeys, which are rapidly increasing in numbers.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Broad-banded Forestsnail is a large (about 30 mm in diameter) terrestrial snail. Shells usually have a distinctive low tooth inside the lower lip of the aperture (shell opening) and a large open umbilicus (hole at the central part of the underside of the shell). The lip of the aperture is white and flares outward. The shell is pale yellow, often with pale brown bands, and the surface is sculptured with fine grooves. Canadian populations of Broad-banded Forestsnail may be genetically isolated from other populations and have significance for conservation.

Distribution

Broad-banded Forestsnail is distributed from southern Ontario and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan south to northern Alabama and east to Pennsylvania and North Carolina. Fossil shells along the Mississippi River as far south as Louisiana represented its southern range limit during the Pleistocene. In Canada, Broad-banded Forestsnail is restricted to the Carolinian Forest region of Ontario on the north shore and islands of Lake Erie. Known subpopulations are presently restricted to Point Pelee and Pelee Island, but there are historical records from the smaller Lake Erie islands and several mainland sites.

Source: COSEWIC 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Broad-banded Forestsnail in Canada.

Long description for Map 4

Map showing the distribution of Broad-banded Forestsnail records at Point Pelee and the Lake Erie islands in 2013. Living and fresh shells are shown at Point Pelee and Pelee Island. There are historical records of the species from Middle Island, Middle Sister Island, East Sister Island, North Harbour Island, Hen Island, Leamington, and Oxley.

Habitat

Broad-banded Forestsnail habitat consists of deciduous forest. In Ontario, extant subpopulations are found primarily in forest and woodland on sandy soil. Empty snail shells were found at some sites extending into wooded alvars (shallow soils over limestone) and shrubby vegetation on sandy soil adjacent to deciduous forest.

Biology

Little information is available about Broad-banded Forestsnail biology. It is an air-breathing, terrestrial snail. Individuals have both male and female reproductive parts (hermaphroditic) and both members of a mating pair exchange sperm and produce eggs. Broad-banded Forestsnail may reach maturity as early as one year, and can live for at least four years. Hibernation occurs buried 5 – 10 cm under the soil or in shallow depressions in the forest floor where leaf litter provides insulation. Broad-banded Forestsnails are active both day and night, but often retire to shelter under leaf litter from mid-morning until late afternoon. Foraging usually takes place on the ground. Green plants and fungus growing on decaying logs are apparently important food sources. Terrestrial snails require damp habitat to feed, move, and reproduce and most species are restricted to forested or wooded habitats that provide shade and retain moisture in the soil and leaf litter. Individuals probably move only a few metres over the course of their lives. Eggs and immature stages are not known to be dispersed by the wind or water.

Population Sizes and Trends

The Canadian population probably declined in the early 1800s, when most of the historical Canadian range was cleared for agriculture. More recently, the number of extant sites has decreased with the apparent loss of subpopulations on Middle Sister, East Sister and Middle islands. The population size is unknown.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Historical and recent threats included forest clearing and Double-crested Cormorants. Most of the forest cover within the mainland range of Broad-banded Forestsnail was cleared decades ago and extant populations are within protected areas where further forest clearing is a negligible threat. Double-crested Cormorant nesting colonies have increased dramatically on the smaller Lake Erie islands since the early 1980s. Associated habitat changes from vegetation dieback and altered soil chemistry probably contributed to the extirpation of snails on these islands. Cormorants prefer to nest on uninhabited islands and are unlikely to colonize Point Pelee and Pelee Island.

Present threats are less well understood. Trampling from recreational use of trails probably kills snails at Point Pelee and Pelee Island. Snails also may be killed in prescribed burns. Altered shoreline processes caused by climate change and shoreline development are causing substantial erosion at Point Pelee and Fish Point. Invasive plants and earthworms occur throughout southern Ontario and may have altered forest ecosystems and snail habitat. Introduced Wild Turkeys and Ring-necked Pheasants may be additional sources of predation.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

Broad-banded Forestsnail is not protected by any Canadian legislation, regulations, customs or conditions except as indicated below. It is not listed under the US Endangered Species Act or under any state or provincial acts. It is not listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The species and its habitat are protected in Point Pelee National Park and Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve by federal and provincial park regulations, but threats from invasive species, accidental trampling from recreational use, and similar activities can still occur.

The Global Rank is G5 (Secure) and Subnational Rank in Ontario is S1 (Critically Imperilled). It is not ranked in most states where it occurs.

Photo: © Mike McGrath

Long description for Figure 5a

Photograph of the Caribou, Rangifer tarandus. The photo shows one animal from the Newfoundland population (NP).

Reason for designation

This population was last assessed as Not at Risk in 2002 when the population was 85,000. This population has fluctuated in abundance over the last 100 years and presently has declined by approximately 60% over the last 3 caribou generations. The decline was due to limited forage when the population was at high density, harvest, and predation. Various indices suggest that the population is improving but there is concern that Eastern Coyote, which has recently arrived to Newfoundland, may become a significant predator and influence recruitment such that the population continues to decline.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) are a medium-sized member of the deer family with relatively long legs and large hooves, which facilitate survival in northern environments. Caribou are central to the culture, spirituality, and subsistence lifestyles of many Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities across Canada. Caribou exhibit tremendous variability in morphology, ecology, and behaviour across their circumpolar range. In 2011, COSEWIC recognized 12 designatable units (DUs); this report assesses three DUs: Newfoundland population (NP; DU5); Atlantic-Gaspésie population (GP; DU11); and Boreal population (BP; DU6).

Distribution

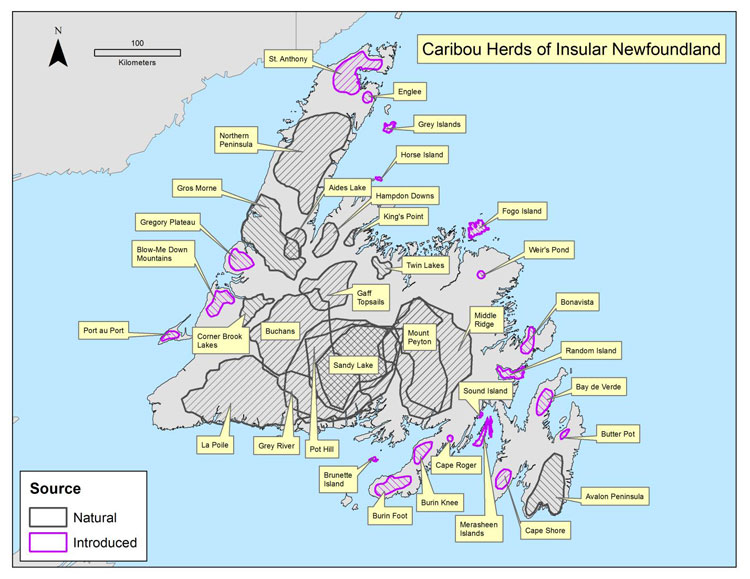

Caribou originally inhabited the entire island of Newfoundland, although three areas of higher abundance were identified in the early 20th century: the Humber River Valley; the central portion of the island south of the railway; and the Avalon Peninsula (Prichard 1910, cited in Banfield 1961). Twelve Caribou sub-populations were present before additional sub-populations were established through a series of relocations made in the 1960s-70s (Mercer et al. 1985). Up to 36 sub-populations have existed (Figure 1) but there appear to be approximately 14 sub-populations presently (Pardy Moores pers. comm.). Shifts in Caribou occupancy have been observed in some sub-populations; anecdotal evidence suggests that a small number of Caribou have begun to reoccupy areas (NLDEC, unpubl. data 2013).

Source: COSEWIC 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Caribou, Newfoundland population, Atlantic-Gaspésie population and Boreal population, in Canada.

Long description for Map 5

Map showing the distribution of 36 Caribou subpopulations throughout the island of Newfoundland during the 1990s. Areas containing naturally occurring subpopulations are distinguished from areas with introduced populations.

Habitat

NP Caribou use coniferous forests, barren lands, shrub lands, and wetland complexes. Selection of closed-canopy conifer forests by Caribou generally becomes stronger with increasing disturbance levels. Anthropogenic disturbance tends to lead to the functional loss of residual habitat.

Biology

Typical longevity in Caribou is < 10 years in males and < 15 years in females. Females ≥ 3 years old give birth to a single calf annually, resulting in an overall lower reproductive rate when compared to other North American deer species. Generation time is estimated at 6 years. Reproductive success is closely linked to forage availability.

Photo: © John Blake, Newfoundland Wildlife Division

Population Sizes and Trends

The NP has experienced dramatic fluctuations, at least since the early 1900s; after a peak estimate of 100,000 individuals in the 1900s, the population declined approximately 85% to 10,000-15,000 individuals between 1925 and 1935, then increased approximately 84% over four decades, and reached 94,000 individuals by the mid-1990s. By 2002, the NP declined to 68,000 individuals, and continued to decline, to approximately 32,000 in 2013. The three generation (18 year; 1996-2013) trend is – 62%. The decline is believed to be due to limited forage that reduced juvenile productivity and survival, excessive hunting during the decline phase and, possibly, additive predation. The present decline appears to be part of natural population fluctuations and recently several indices on health and calf survival suggest that the population will increase.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The primary threat to Caribou persistence is habitat loss and excessive mortality rates, factors which often interact because predation increases in disturbed areas. Cumulative anthropogenic (e.g. natural resource extraction and development, roads), and natural disturbances (e.g. forest fire, blowdown) are associated with avoidance behaviour, and decreased recruitment because of increased predation rates. Forest-clearing activities (e.g. forestry, oil and gas development) increases the abundance of alternate prey (e.g. Moose, deer), which can cause increased mortality rates on Caribou. Predation is considered a major proximate threat to Caribou in developed regions of the BP, and in all of GP, and of unknown, but likely lower, significance in the NP. In NP, disturbance appears less significant because fires are rare and much of the range has relatively minimal forestry or mining activity. […] Natural factors, such as climate change and environmental disturbance, can impact Caribou habitat. The NP, BP, and GP are all associated to varying extents with mature - old coniferous stands, which are subject to fire events that are likely to increase in the future, particularly in the BP range. Disease impacts are less well known but there are concerns over spread of brainworm in parts of BP range and several pathogens in BP and GP range. A threats assessment concluded that the overall threat is High-Medium for the NP, Very High-Very High for the GP, and Very High-High for the BP.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

COSEWIC assessed the conservation status of NP in 1984, 2000, and 2002, and recommended that this population was Not at Risk. The NP was ranked as S4 in 2012 at the provincial level. In NP, large areas exist which are of marginal timber value and are not in imminent danger of being disturbed by industrial activity. […] Forest management plans have been modified to assist Caribou in parts of all three DUs, but implementation is variable and efficacy unknown to date. Predator control has been applied annually since 2001 in the GP, and in parts of the BP. In the NP, hunting of Black Bear and Coyote occurs but direct predator control is not applied.

Photo: © Carita Bergman

Long description for Figure 6a

Photo of a Cassin's Auklet, Ptychoramphus aleuticus, from above. The image shows a compact seabird with short wings. The plumage is dark grey and there is a small white crescent above the eye. The irides are white.

Reason for designation

About 75% of the world population of this ground-nesting seabird occurs in British Columbia. Overall, the Canadian population is thought to be declining, but population monitoring has been insufficient to determine size and trends. The species faces threats from mammalian predators that have been introduced to its breeding islands. While predators have been removed from some breeding colonies, it is likely that ongoing predator management is going to be needed to maintain the species. The species also faces other threats when it forages at sea, including large-scale climate change effects on its oceanic prey, and risks from oiling.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Cassin’s Auklet is a small grey seabird in the Family Alcidae. About 75-80% of the global population breeds in British Columbia. This species comprises almost half of all seabirds nesting in British Columbia.

Two subspecies are recognized, Ptychoramphus aleuticus aleuticus and P. a. australis. Only the former subspecies is found in Canada.

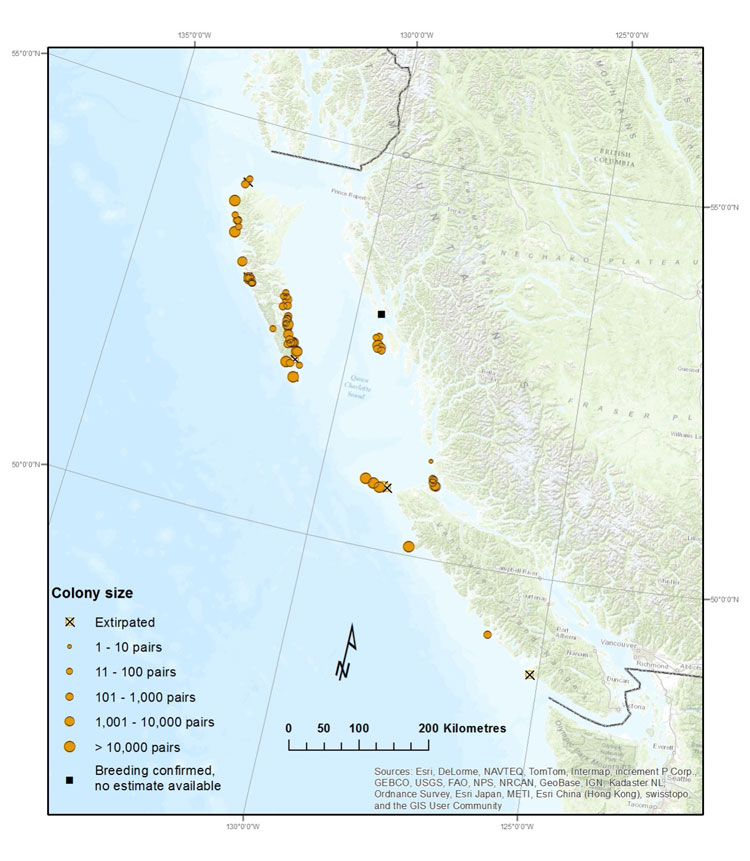

Distribution

Cassin’s Auklets are found along the Pacific coast of North America. They spend most of their lives at sea and come to land only to breed. Most nest in colonies on coastal islands from the western Aleutian Islands in Alaska to central Baja California; they occasionally nest in Siberia and on the Kuril(e) Islands in Japan/Russia. During the non-breeding season, the birds are found mainly from southeast Alaska through Baja California, with concentrations off California.

Source: COSEWIC 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Cassin’s Auklet in Canada.

Long description for Map 6

Map showing locations and relative sizes (by number of pairs) of colonies of Cassin's Auklets in British Columbia. Cassin's Auklets nest on 62 islands or island groups along coastal Haida Gwaii, the north and west coasts of Vancouver Island and the northern mainland coast.

Habitat

Cassin’s Auklets nest on islands that are free of native mammalian predators, such as raccoons and mink. In British Columbia, the vast majority nest in burrows in forested or treeless habitats. Most burrows are within 100 m of the shoreline. The amount of suitable nesting habitat has declined over the past 75 years due to introductions of mammalian predators to colony islands. Changes to vegetation have also decreased the amount of high-quality nesting habitat on some islands since the 1980s.

At sea, the Cassin’s Auklet inhabits two oceanographic domains: the California Current System, which extends from the northern tip of Vancouver Island through Mexico, and the Alaska Current System farther north. The birds’ marine habitat is highly variable over multiple temporal scales. Atmospheric/oceanographic processes that elevate ocean temperatures (e.g., warm water phases of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation) are associated with reduced Cassin’s Auklet reproductive performance while those that cause extreme climate events (e.g., El Niño events) can lower adult survival rates.

Photo: © Carita Bergman

Long description for Figure 6b

Photo of a Cassin's Auklet, Ptychoramphus aleuticus, in water

Biology

Cassin’s Auklets lay a single-egg clutch, which is incubated by both parents on alternating days for about 38 days. After the egg hatches, parents return to the burrow at night to feed the nestling for about 45 days. The young are independent at fledging.

In the California Current System, Cassin’s Auklet reproductive success and fecundity are reduced during warm water years due to declines in food availability. Reduced reproductive success is attributed to a temporal mismatch between the nestling provisioning period and the birds’ critical zooplankton prey, which peaks in abundance earlier and for a shorter duration during warm water years. In addition, adult survival is reduced during extreme climate events. In contrast, Cassin’s Auklets in the Alaska Current System show reduced survival during El Niño events, but no effects on reproductive performance.

Population Sizes and Trends

The global population of Cassin’s Auklet is estimated at 3.57 million breeding individuals, of which about 2.69 million (75%) nest in Canada. Triangle Island is the world’s largest Cassin’s Auklet colony and alone supports about 55% of the global population. Over the last 75 years, colonies have been extirpated by introduced predators: rats, raccoons and mink. The magnitude of decline is largely unknown because population data are available for fewer than 30 years.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The main threats are climate change, introduced predators and oil spills. Climate change is expected to result in warmer ocean temperatures and more frequent El Niños, both of which have negative consequences for Cassin’s Auklet reproduction and survival. The impacts are expected to be most severe and immediate in the California Current System. Rats, raccoons and mink cause notable destruction to, and possibly extirpations of, colonies. The threat of oil contamination from chronic or catastrophic spills is ongoing and expected to increase if offshore vessel traffic increases.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

Cassin’s Auklet is categorized as a species of “Least Concern” according to the IUCN Red List and its global status is “Apparently Secure”. Nationally and provincially, the breeding population is considered vulnerable to imperilled, whereas the non-breeding population is considered apparently secure. Cassin’s Auklet has been placed on the British Columbia Blue List as a species of Special Concern. It is an Identified Species under the province’s Identified Wildlife Management Strategy in the Forest Range and Practices Act. Only one breeding colony (supporting less than 1% of the population) does not have formal protection in British Columbia.

Photo: © Scott Gillingwater

Long description for Figure 7

Photo of an Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina, on sparsely vegetated ground, showing side and front of carapace and side of head. The carapace is slightly keeled, high-domed, and brown to black with yellow patterning.

Reason for designation

This turtle occurred historically in Ontario based on archeological evidence and Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge. Habitat modification has been extensive and the species is no longer extant. Considerable search effort has documented fewer than 10 individuals in Ontario, but these individuals all represent released captive individuals from unknown sources and are not considered part of the former Canadian population.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) is a small terrestrial turtle rarely exceeding 16 cm in straight carapace length. It has a slightly keeled, high-domed carapace, which is usually brown to black with variable yellow to orange patterning. The plastron has a hinge, allowing the two lobes to completely close against the underside of the carapace. The Eastern Box Turtle has special cultural significance to the Iroquois. It is also the largest known freeze-tolerant animal in the world.

Distribution

The Eastern Box Turtle is found across much of eastern North America. It occurs from central Michigan to southern Maine in the north and from eastern Texas to Florida in the south. Disjunct populations occur in two areas of Mexico. No current native populations of the Eastern Box Turtle are known to exist in Canada. The remains of Eastern Box Turtles have been found at 12 archeological sites from Ontario. COSEWIC has previously assessed the Eastern Box Turtle as native to Canada (Ontario).

Source: COSEWIC 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Box Turtle in Canada.

Long description for Map 7