Blue shark (Atlantic and Pacific populations) COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 8

Biology

- Life Cycle and Reproduction

- Predation

- Physiology

- Dispersal/Migration

- Interspecific Interactions

- Adaptability

In Canada’s Atlantic waters, there has been some effort to collect biological information including length/frequencies by sex, diet, age and patterns of movement. There has been insufficient biological research done on blue sharks in Canada’s Pacific waters to derive any meaningful conclusions. The global occurrence of this species along with known large migration patterns suggests that biological information derived from outside of Canada is applicable to sharks utilizing Canada’s waters.

Mating and Parturition

Blue sharks are viviparous with an average litter size of 25.6 (Range 1-62, n=600) in the North Pacific (Nakano 1994). In the northwest Atlantic, litter size has not been well investigated. Bigelow and Schroeder (1948) report an average of 41 based on a sample size of two individuals. In European waters, a mean litter size of 36.6 was derived based on eleven individuals. Although there is considerable individual variation, average litter size is likely between 25 and 50. The sex ratio of embryos is on average 1:1. There is a positive correlation between female length and litter size (Nakano and Seki 2002).

Mating appears to be most frequent in the spring to early summer season. After copulation, there is evidence that females may store spermatozoa for periods of months or years waiting for ovulation (Pratt 1979). After fertilization, gestation is between 9-12 months. Birth has been observed over a wide seasonal range from spring to fall suggesting considerable variation amongst individuals. Pratt (1979) estimated that blue sharks off New England produce a litter about every two years.

Growth and Maturity

Length of newborn pups is typically considered to be 40-50 cm, although a range of 35 to 60 cm has been reported in the literature (Nakano and Seki 2002). Several growth models have been published from around the world with similar results. Models from the Atlantic predict a slightly faster and larger growth when compared to Pacific populations but none of these models is considered to provide precise age estimates. Two recent growth models from the northwest Atlantic using vertebral sections (Skomal and Natanson 2003) and whole vertebrae (MacNeil and Campana 2003) to estimate age showed similar trends in length at age for the first four years of age but then varied after that age. The whole vertebrae technique predicts faster growth (~15-20%) than does the sectioned vertebrae technique. The differences in the models have implications for understanding the mortality rates (see Mortality and Productivity section) since a faster growth rate translates into a higher estimated total mortality rate (Z).

Length at maturity has been examined in numerous studies in various regions reviewed in Nakano and Seki (2002). In the North Pacific, length at 50% maturity for males and females respectively is 203 cm (total length) and 186-212 cm (TL) which corresponds to the ages of 4-5 years and 5-6 years respectively (Nakano 1994). Campana et al. (2004) estimated length at maturity for male sharks caught in Atlantic Canadian waters to be between 193 to 210 cm (fork length) and Pratt (1979) reports maturity for females in the North Atlantic to be between 145 to 185 cm (FL). Age of maturity is between 4 to 6 years. Maximum age is between 16 to 20 years (Skomal and Natanson 2003).

Natural mortality has never been directly estimated in blue sharks. There are various published estimates of natural mortality (M) reported in the literature, which vary from as low as 0.07 to a high of 0.48 with a mean of 0.23 (i.e., approximately 23% of the population is dying from natural causes each year) (Campana et al. 2004).

Intrinsic rate of population growth at maximum sustained yield (r2M) for Pacific populations was estimated by Smith et al. (1998) to be 0.061. Compared to other elasmobranchs, blue sharks are productive. Campana et al. (2004), using data from the North Atlantic, found the intrinsic population growth rate to be 0.36, which translates into an annual increase in the population (i.e., growth rate) of ~43%. Such high population growth rates may help explain why blue sharks have been slow to decline in the face of what appears to be very high overall catch mortality.

Campana et al. (2004) estimated that the generation time of blue sharks in the North Atlantic is 8.1 years using life table analysis. Overall, blue sharks have a high natural mortality and high intrinsic population growth rate in comparison to other sharks.

There are no known predators of adult blue sharks (Nakano and Seki 2002). Sub-adults and juveniles are taken by both shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) and white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). In addition, California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are reported to eat blue sharks (Lowry et al. 1990, Froese and Pauly 2004). The high level of natural mortality (described above) suggests that predation on juveniles must be high but the nature of the predation is poorly understood. Blue sharks are the most heavily fished species of shark in the world, and given there are no known predators of adult blue sharks, humans are likely the most significant predator.

Blue sharks can tolerate a wide range of temperatures 5.6-28º C but prefer temperatures in the middle of this range (8-16º C). This tolerance range allows for a wide distribution assuming that temperature is the primary factor affecting distribution.

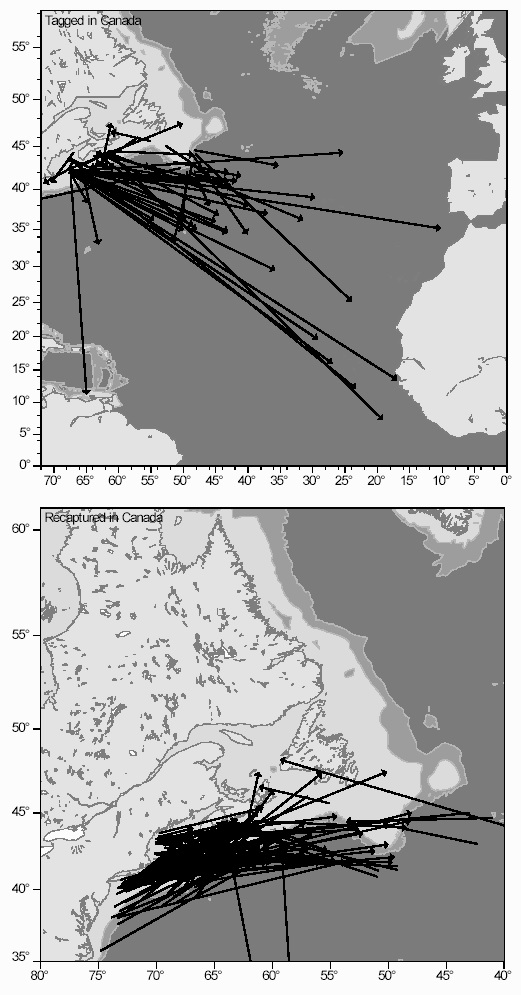

Blue sharks actively move throughout North Atlantic and Pacific waters as indicated from tagging. There are two tagging studies applicable to populations in Canada’s North Atlantic waters. A Canadian study carried out between 1961 and 1980 tagged 2 017 individuals of which 17 were recaptured. This study indicated that the blue sharks move in and out of Canadian waters as well as exhibit movement between offshore and inshore habitats (Burnett et al. 1987). The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) conducted a long-term tagging study (1971-2002) where thousands of blue sharks (n=60 856) were tagged in U.S, international, and Canadian waters. Of the sharks tagged in Canada (n=916), most were recaptured in the central and eastern Atlantic, but some were captured off western Africa (Figure 9A). Blue sharks tagged in the NMFS tagging program outside of Canada (U.S. and international waters) between 1974-2002 resulted in 188 recaptures in Canadian waters (Figure 9B, Campana et al. 2004). There was no obvious difference in migration pattern between males and females, or between small and large blue sharks. In the northeast Atlantic, tag recapture information suggests a seasonal migration between 30-50° N with some gender and size differences in movement (Stevens 1976). The Central Fisheries Board of Ireland monitors a volunteer-based tagging program (Central Fisheries Board). The starting year of the program is not reported. By the end of 1998 15 037 blue sharks around the Irish coast had been tagged of which 490 have been returned (3.25%). Several of the recaptures were from the western North Atlantic with two records from waters south of Newfoundland. Most recaptures were from the northeastern Atlantic around the Azores.

There have been no tags applied to blue sharks in Canada’s Pacific waters. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has tagged 7925 blue sharks off California of which 141 have been recaptured (CDFG 2003). The overall results of the tagging program have not been published but at least three of these sharks were caught near the coast of Japan between 1.5 and 2 years after tagging (CDFG 2003). Nakano and Seki (2002) suggest a large scale, sex and size segregated Pacific migration described in the ‘Habitat’ section of this report.

Figure 9: Movements of Blue Sharks A.) Tagged in Canada or B.) Recaptured in Canada Between 1971-2002 Under the NMFS Tagging Program

From Campana et al. (2004).

In September of 1991 a private company conducted the only blue shark research done in Canada’s Pacific waters (IEC Collaborative Marine Research and Development Limited 1992). The four-day longlining trip was conducted off the west coast of Vancouver Island with the intention of capturing blue sharks. In this period 134 sharks were captured, all immature with an average length of 147 cm and with pronounced sex segregation (124 females and 10 males), which is consistent with Nakano’s model described earlier (see Habitat section). Two separate samples in an experimental Canadian high seas driftnet fishery in the eastern North Pacific (1987) found significantly more males in one sample (males 26, females 13) and significantly more females in another (males 7, females 34-none with pups) (McKinnell and Seki 1998).

Overall, the tagging studies are consistent the view that blue sharks are highly migratory, with no evidence of extended residency in Canadian waters. The observation that few of the sharks tagged off Atlantic Canada were later recaptured in U.S. waters supports the hypothesis that many blue sharks migrate in a clockwise gyre across the North Atlantic.

The hemispheric distribution of blue shark, their apparent migration through Canadian waters, the absence of reproduction occurring in Canadian waters (i.e., few mature individuals), the low fishing mortality in Canadian waters relative to the entire Atlantic population, and the composition of the Canadian catch (mostly immature individuals (Figure 8)) all suggest that blue shark abundance in Canadian waters is dependent entirely on the abundance of the hemispheric populations.

Blue sharks have been reported to eat a wide variety of prey consisting of an assortment of bony fishes, squid, birds, and marine mammal carrion. They are capable of pursuing and capturing numerous prey sources and are generally considered to be opportunistic feeders. There has been only one diet study in Canadian waters (McCord and Campana 2003). This study was undertaken on ‘derby-caught’ blue sharks off Nova Scotia in August and September (1999-2001). Pelagic and demersal teleost (bony) fish comprised the primary prey sources but an assortment of other prey sources was also found. There were also differences observed depending on size and sex of the sharks which is likely a reflection of either depth segregation and/or size selectivity of prey depending on the shark size. Overall, blue sharks eat a wide variety of prey and are capable of prey switching to take advantage of locally and seasonally abundant prey. The abundance and distribution of this species is not considered to be limited by caloric or nutrient intake.

Blue sharks are the most widely distributed and most abundant pelagic shark species in the world (Nakano and Seki 2002) which, combined with their wide prey base, lack of known fine scale population structure, a huge habitat (all temperate and tropical oceans), and no known dependence on other ecosystem components that may themselves be at risk, suggests that blue sharks would be resilient to many natural changes.