Bluntnose sixgill shark (Hexanchus griseus) COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 8

Population Sizes and Trends

Search effort

In the preparation of this report, the authors approached shark experts and institutions along the west coast of North America. There are no long-term indices of bluntnose sixgill shark abundance or estimates of absolute abundance. Standard fisheries independent surveys using either bottom trawls or setline gear do not capture bluntnose sixgill shark with sufficient regularity to index their populations. We examined the International Pacific Halibut Commission setline survey 1994-2004 (6 records), the National Marine Fisheries Service Triennial bottom trawl survey (1 record from Canadian waters), and several Department of Fisheries and Oceans trawl surveys (1 record). None of these surveys are suitable for indexing trends in abundance or suitable for estimating absolute abundance through expansion.

Abundance

Long-term effective population size has been estimated through genetic techniques to be about 7900 individuals (Larson et al. 2005). This estimate was based on examining genetic diversity using seven microsatellite DNA markers from ~200 individual juvenile animals biopsied in Puget Sound (2001-2004). Given the low number of markers, assumptions about mutation rates, and the limited spatial area from which the samples were drawn (central and southern Puget Sound), this estimate is unlikely to be accurate, and in any event may not reflect recent changes in population abundance. Furthermore, the spatial extent of the breeding population is unknown. If suspected dispersal and movement patterns of bluntnose sixgill shark are correct then the breeding population likely resides along the continental shelf of western North America. The extent of latitudinal migration and dispersal is unknown.

Fluctuations and trends

A video surveillance study occurring on a small shallow rocky reef near Flora Islets (49°30.9′N, 124°34.5′W) in the Strait of Georgia described earlier in this report is the only index of abundance available for bluntnose sixgill sharks in Canadian waters (see section on Dispersal and Movement). Unpublished results from this study have shown a consistent and gradual decline in the frequency of sightings from 2001 to 2005 (Figure 11, Dunbrack pers. comm. 2006). It is important to note that individual sharks are typically not identifiable and therefore the index may not record abundance but rather behaviour at the site. The observed change is also corroborated by a similar decline in encounter rates during recreational SCUBA dives from an average of 1.8 sharks/dive in 1999 to 0.1 sharks/dive in 2005 (Heath pers. comm. 2006; Appendix 5). The dive data has not been standardized to account for actual effort (i.e., time in water, number of divers) and therefore is considered to be anecdotal.

Figure 11. Relative frequency of bluntnose sixgill shark sightings from a permanent video surveillance camera at Flora Islets, Strait of Georgia. Sightings are recorded during daylight hours. Dunbrack pers. comm. (2006) unpublished data.

The Flora Islet study site is globally unique as there are very few places where bluntnose sixgill sharks can be observed regularly in shallow waters. Because of the atypical nature of this site combined with only a single surveillance point, interpretations made from the observed trend must be viewed with caution. There are no obvious explanations, such as the start of a major fishery, for the decline in the encounter rate. The only fishery in the Strait of Georgia known to capture bluntnose sixgill sharks is the spiny dogfish longline fishery. This fishery has operated in the Strait of Georgia for several decades with various levels of landings (Figure 12). Since 2002 spiny dogfish landings have increased in the entire Strait of Georgia. It is unlikely, even under the assumption that mortality to bluntnose sixgill shark has increased that it would be enough to account for the virtual disappearance of bluntnose sixgill sharks from the Flora Islets site.

Figure 12. Landings (t) of spiny dogfish by longline gear in PMFC area 4B: Strait of Georgia. Source: PacHarvHL database.

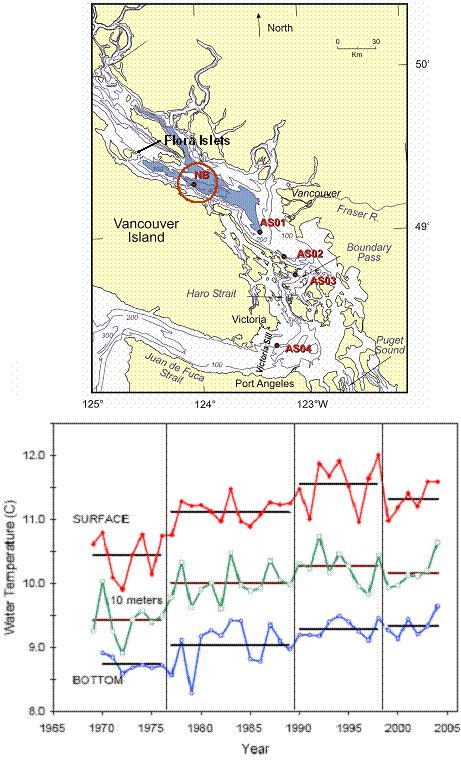

Other plausible explanations include a change in environmental conditions such as water temperature that may influence the depth distribution of the sharks. There has not been reproductive or feeding behaviour of bluntnose sixgill sharks observed at the Flora Islet site. Therefore Dunbrack and Zielinski (2003) suggest that local presence of bluntnose sixgill sharks at the study site might be due to the thermally stable, deep bottom layer of the Strait of Georgia, which is similar to cool continental slope waters (where most bluntnose sixgill shark populations are found). The Navy hydrographic station off Nanoose Bay located in the central Strait of Georgia (~50 km from the study site) has recorded depth-temperature profiles since 1969 (Figure 13). In 2004 the temperature at 10 metres was the second highest annual temperature recorded since 1970 and the bottom layer (395 m) was the warmest on record (Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) 2005b; Figure 13). This warm trend persisted through to 2005 (DFO 2006). It is possible that these observed differences in temperatures extended northwards to the Flora Islet site thereby influencing the video encounter rates of bluntnose sixgill shark at Flora Islet.

Figure 13. Location of Nanoose Bay (NB) hydrographic station and Flora Islet study site (left panel) and annual mean water temperature profiles (surface, 10m and 395 m) for 1969 to 2003 collected at Nanoose Bay hydrographic station (right panel). Sources: DFO 2002; DFO 2005b.

Summary of trends and current status

There are presently no reliable indicators for understanding bluntnose sixgill shark status in Canadian waters. Intensive fishing for this species took place in the late 1930s to mid-1940s and there was a small experimental fishery in the late 1980s to early 1990s, but otherwise catch of this species has been limited to bycatch. The amount of bycatch is unknown but was estimated in this report to range between 12 and 38 t per year of which an unknown percentage is actually killed. The overall impact that bycatch fishing mortality has on the population depends on the size of the population, which at the present time is largely unknown and the demographic of the bycatch itself (i.e., size, sex). A single abundance estimate based on genetic techniques suggests a long-term effective population size in the northeast Pacific of about 8000 individuals (Larson et al. 2005), but the relationship of this value to absolute contemporary abundance is not clear. Encounter rates with immature bluntnose sixgill sharks at a shallow site in the Strait of Georgia have decreased significantly (>90%) over the last five years based on video surveillance and anecdotal diving records (Dunbrack pers. comm. 2006; Heath pers. comm. 2006). Fishing is not likely the cause of this decline. Environmental data, although limited, may offer an explanation for the downward trend.

Rescue effect

At the present time the overall abundance and movement patterns between Canadian and U.S. populations is unknown and therefore the expected rescue effect that the U.S. population may have on the Canadian population is unknown. The abundance of this species in Alaskan waters is unknown, they are rarely caught by commercial fisheries and do not appear in fisheries surveys (Courtney et al. 2004).