Eastern foxsnake (Elaphe gloydi) (Carolinian)COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 7

Habitat

Traditionally, the Eastern Foxsnake has been considered a snake closely tied to the marsh ecosystems of Lakes Erie and Huron. However, as demonstrated by several extant populations in Ontario, marshland habitat is not required for persistence, at least not in the short term for southwestern (SW) Ontario populations, and not at all for the Georgian Bay Coast regional population (see below). Although there are similarities among the three regional populations, in terms of habitats used, the differences can be examined more effectively by discussing them separately.

Surveys (Rivard 1976, Freedman and Catling 1978, Willson 2002), focal telemetry studies (Watson 1994, M’Closkey et al. 1995, Brooks et al. 2000, Willson 2000), and general species observations (e.g., Ontario Herpetofaunal Summary (OHS), naturalist’s observations) suggest that foxsnakes throughout most of the Essex-Kent regional population use mainly unforested, early successional (old field, prairie, marsh, dune-shoreline) habitat during the active season. Hedgerows bordering farm fields and riparian zones along drainage canals are regularly used. In some areas of intensive farming, these linear habitat strips likely make up the bulk of habitat available to foxsnakes.

Examination of the OHS records in Essex County shows that foxsnakes are found considerable distances from the Great Lake’s shoreline--and superficially at least, from marsh or other wetland habitats. However, a closer examination of the species’ distribution, taking into account historical land changes, reveals that many of the locations where foxsnakes occur are either currently associated with wetland habitat features (e.g., Hillman Marsh, Pt Pelee National Park), or were likely associated with more extensive wetland features in the recent past. Essex County, as described in Habitat Trends, has experienced drastic reductions in wetland cover over the last 100 years: the “Black Swamp” wetlands formerly extended a considerable distance from the Lake Erie shoreline. Additionally, the majority of the populations (as best as can be determined with the OHS records) that are seemingly extant are actually situated within, or close to, the presumed drainage basins of several of the county’s watersheds (e.g., Big Creek, Cedar Creek, Turkey Creek, Canard River). Finally, within many of these watersheds, drainage features (e.g., ditches, drains) that retain wetland characteristics are still present. Therefore, it is likely that the dryer areas where foxsnakes persist have either retained remnant wetland features, or were formerly wet, and this suggests that wetland attributes were at least important to the initial colonization of these areas by foxsnakes.

For snakes inhabiting northern latitudes, the three most important microhabitat features, in order of importance, are (1) hibernation sites, (2) oviposition and/or gestation sites, and (3) basking-shelter sites (e.g., features that promote ecdysis, digestion). Foxsnakes in this region have been found to hibernate in a variety of both natural and anthropogenic features including limestone bedrock fissures, small mammal burrows (e.g., muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) and possibly eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus); T. Linke pers. obs.), bases of utility poles, canals, wells, cisterns, and building foundations. Many of the hibernacula are used by multiple individuals and species. The largest documented site harboured 33E. gloydi, 22 Northern Watersnakes, and 84 Eastern Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) (Watson 1994, M’Closkey et al. 1995). Yet, single occupancy of hibernacula was noted on Pelee Island (Brooks et al.2000) and in Point Pelee (M’Closkey et al. 1995).

On Pelee Island, sites used for oviposition included rotting cavities within downed trees; decaying leaf, woodchip, and herbaceous vegetation piles; rodent burrows excavated in loamy soil at roadside edges, and hay piles (Porchuk and Brooks 1995, Brookset al. 2000, Willson and Brooks 2006).

Frequently used basking and shelter sites usually have thermal properties (e.g., ideal solar exposure) that permit foxsnakes to maintain body temperatures near the upper end of their preferred range, but at the same time provide protection from predators. Brush piles, table rocks, tree stumps, root systems of downed trees, driftwood, and combinations of these features provide this functionality. Foxsnakes are also often found in, or under, old pieces of tin, wooden planks, abandoned vehicles, car hoods and parts, asphalt, masonry, etc. (Rivard 1976, 1979; Catling and Freedman 1980; Watson 1994; M’Closkey et al. 1995; R. Willson unpubl. data).

Clearly, foxsnakes are somewhat adept at using anthropogenic structures for hibernation, oviposition, and shelter. The use of natural versus anthropogenic microhabitat features seems to vary depending upon the level of landscape modification and, presumably, the availability of natural sites. For example, 12 of 14 foxsnakes radiotracked to hibernacula on Pelee Island used natural limestone fissures (R. Willson unpubl. data), whereas 6 of 10E. gloydi radiotracked in Point Pelee used hibernacula that were clearly associated with anthropogenic habitat structure (e.g., wells and canals; Watson 1994, M’Closkey et al.1995).

The landform-vegetation types available (e.g., beach-dune, extensive marsh) within the foxsnake’s distribution in the Haldimand-Norfolk region, as well as the areas where foxsnakes are regularly encountered by researchers and naturalists, suggests that habitat usage and requirements within this regional population are generally similar to those of Essex-Kent. Habitat types at Long Point and Big Creek Marsh are similar to those used by foxsnakes at Rondeau Provincial Park and Point Pelee. Many sightings in this region are close to Big Creek suggesting that Big Creek is a corridor for the species to move into surrounding slough-swamp-forests (S. Gillingwater pers.comm.) (see Figure 3). However, the extensive dune-slough complex along Long Point is somewhat unique amongst sites where foxsnakes occur in southern Ontario (S. Gillingwater pers. comm.). At this site, large dunes, along with a mosaic of ponds, sloughs, and marsh combine with mixed Carolinian forest to provide a varied habitat for this species. Hedgerows and riparian zone vegetation are also likely used by foxsnakes in this region.

Intensive telemetry-based studies have not been conducted at sites within this region; thus, knowledge of hibernacula is limited to a few locations. Two snakes radiotracked in 1993 hibernated separately in abandoned mammal burrows (M. Gartshore et al. unpubl. data). Whereas these hibernation sites did not appear to be communal, multiple foxsnakes have been observed hibernating in the basement foundation of a house that is currently occupied by humans (S. Gillingwater et al.pers. obs).

Oviposition sites are likely similar to those used in Essex-Kent, as downed Cottonwoods (Populus deltoides) similar to those used on Pelee Island are common (R. Willson pers. obs.), and the agricultural environment would provide for ample composting-type sites (e.g., decaying leaf and woodchip piles). Several nests have been discovered under rotting wood on the beaches of Long Point and along the edges of dune blow-outs where eggs are laid along or within the root systems of dune grasses (S. Gillingwater pers. obs.). At Rondeau, eggs have been found under driftwood, as well as partially buried in sand under the large leaves of broad-leafed plants along the margin of beach and wetland sites (S. Gillingwater pers. obs.).

Basking-shelter sites are likely similar to those used in Essex-Kent given the similar landform-vegetation types and climatic conditions. Juniper shrubs are often used as shelter by foxsnakes in the Long Point area (S.Gillingwater, pers.comm.).

For the most part, the landscape inhabited by Eastern Foxsnakes along the Georgian Bay Coast is considerably different from the areas where they are found in SW Ontario. Open rock barrens with intermittent trees and shrubs such as white pine (Pinus strobus) and common juniper (Juniperus communis) dominate the shoreline of the mainland coast and the numerous islands. Lawson (2005) and MacKinnon (2005) found that foxsnakes use a variety of open habitats (e.g., rock barren, coastal meadow marsh) along the coast for foraging, thermoregulating, and mating. Individuals did not move very far into, nor did they spend a lot of time in, forested habitats. The two most striking results of these investigations were the high affinity Eastern Foxsnakes showed for the shoreline (e.g., 95% of all radiolocations obtained from individuals at their Killbear study site and at their Honey Harbour-Port Severn study site were within 149 m and 94 m of the shoreline respectively: MacKinnon 2005), and the degree to which most individuals used water as the primary medium for locomotion. Indeed, rather than inhibit the movement of this snake which heretofore had been considered terrestrial, water seemed to greatly facilitate and possibly promote movement. For example, radiotagged individuals readily swam considerable distances, up to 10 km, in open water to rocky offshore islands (MacKinnon 2005, Lawson 2005). At least one Eastern Foxsnake population within the Georgian Bay Coast regional population diverges somewhat from the pattern of habitat use described thus far. This population is centred on a regionally rare limestone formation and is at the southernmost extent of the species’ Georgian Bay distribution. Interestingly, individuals radiotracked from this area occupy an agricultural landscape wherein old field habitats reminiscent of the SW Ontario landscape are used in addition to anthropogenic microhabitats around farmsteads (MacKinnon 2005).

Lawson (2005) and MacKinnon (2005) found that the majority of foxsnakes in the Georgian Bay Coast region hibernate in granite or limestone fissures in the bedrock. At least nine hibernacula were documented in the Killbear study area and three were documented in the Honey Harbour-Port Severn study area. All of the hibernacula located thus far have been within 100 m of the waters of Georgian Bay except one: the hibernaculum located within the limestone outlier was ≈900 m from the closest point of Georgian Bay. Furthermore, potential hibernation habitat within this landform exists up to 960 m from the waters of Georgian Bay. Use of communal hibernacula would seem to be more common in the Georgian Bay region, as would the average and maximum number of foxsnakes hibernating at a site. This finding accords well with the predicted pattern of communal hibernacula use in temperate-zone snakes; that is, increasing communalism at these sites as latitude increases (Gregory 1982).

Documented oviposition sites along the Georgian Bay coast include rock crevices and composting vegetation piles (MacKinnon 2005, Lawson 2005). Whereas compost piles are similarly used as oviposition sites in SW Ontario, oviposition in rock crevices appears to be unique to this region.

Not surprisingly, basking-shelter sites along the Georgian Bay coast are predominantly rock-based: either table rocks with suitable rock-substrate gaps, or fissures in the bedrock that provide analogous structure (e.g., overlying rock of a thickness that promotes temperature regimes preferred by the snakes). Brush piles, root systems of living and downed trees, and common junipers also provide basking-shelter sites.

The current distribution of marshland along the lower Great Lakes is a minor remnant of the previous extent of this habitat type. Greater than 90% of the original wetlands (possibly greater than 95% in Essex County and the municipality of Chatham-Kent) have been converted to other uses--primarily drained for agriculture and waste disposal (Snell 1987). Some of these changes have occurred relatively recently. For example, although 95% of the original wetlands present in Essex County in the early 1800s had been lost by 1967, a further loss of 15.8% of the remaining 5% occurred between 1967 and 1982 (Snell 1987). Further wetland loss of this scale is not likely to occur in SW Ontario given the limited occurrence of remaining wetlands, and the focus of conservation authorities on natural watershed preservation and enhancement.

The agricultural landscape that replaced the vast network of wetlands in SW Ontario was almost certainly lesser quality habitat for the Eastern Foxsnake. Yet, because of the relatively low human density in those rural environments, as well as the vestiges of natural features occasionally left by farmers (e.g., hedgerows, small fields and woodlots), the Eastern Foxsnake has persisted in several highly modified (by agriculture) areas (Figure 6). However, ongoing removal of these features, in some areas, to facilitate larger cropped fields or residential developments may lead to further disappearance of these remnant populations.

In the Georgian Bay Coast, a similar situation exists in the Port Severn area where low intensity agriculture and low density residences are being replaced with high density developments (MacKinnon et al. 2005) and this area is growing faster than any other in Ontario (Watters, 2003). More important, because the foxsnake is largely confined to habitats < 100m from the Georgian Bay shoreline, its habitat throughout the region is succumbing to cottage and other recreational development (See Figure 7, for example).

Within protected areas, the loss of important microhabitats occurs when erosion and flood control structures along shorelines eliminate natural treefall, an important source of oviposition and shelter sites. Outside of protected areas, loss of important microhabitats along shorelines occurs with steady frequency as the majority of lots are “cleaned up”: i.e., downed trees, woody debris, and native herbaceous vegetation is removed. Although the destruction of these potentially important microhabitats is strongly discouraged by responsible ecological consultants (e.g., in site plans that restrict the ways a property can be modified), many landowners have a sense of entitlement that trumps environmental concerns and enforcement of site plan agreements is currently lacking.

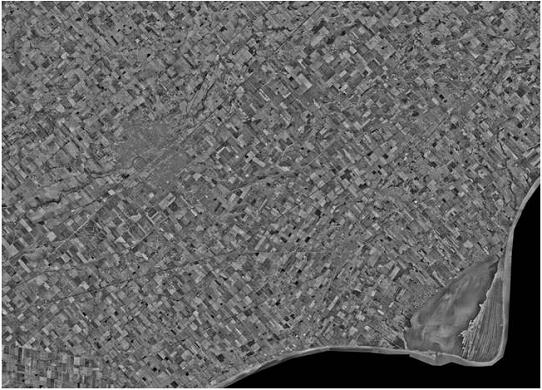

Figure 6: Area Surrounding Rondeau Provincial Park (peninsula on extreme lower right) Showing the Park’s Isolation by Agriculture and Housing and How Close these Activities are to the Park and Lake Erie Shoreline

Dark colour on bottom right is Lake Erie. Photo courtesy of S. Gillingwater

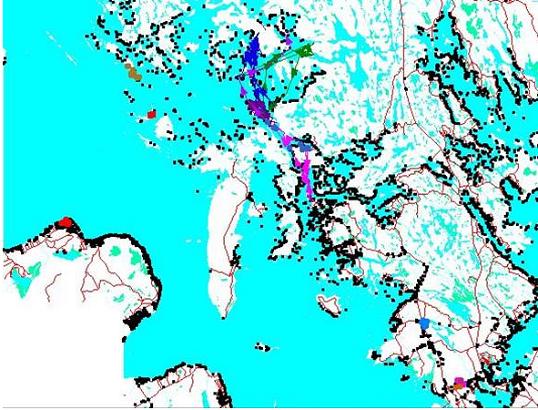

Figure 7: Cottage Development in Southern Georgian Bay in the Southern Part of the Range of the Eastern Foxsnake on the Georgian Bay Coast

Black dots are cottages/buildings and turquoise is water. Purple and dark blue are ranges of radiotracked Eastern Foxsnakes. Map courtesy of C. MacKinnon.

Measures to protect the habitat of the Eastern Foxsnake are in place for both public and private lands, although it must be noted that Critical Habitat for the Eastern Foxsnake has not yet been identified under the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Eastern Foxsnakes are known to occur in two National Parks (Point Pelee and Georgian Bay Islands; hereafter GBI), several Provincial Parks, and several National Wildlife Areas (e.g., Long Point, Big Creek, St. Clair) and conservation areas (e.g., Hillman Marsh). Protection of important habitat (micro and macro) within the two national parks should be strong because of measures in both the Canada National Parks Act (2000) and the federal Species at Risk Act (2002): specific to SARA, “residence” habitat features and “critical habitat” are to be protected on federal lands (see http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/showtdm/cs/S-15.3). Although the area encompassed by the two national parks is small relative to the species’ area of occupancy, both parks engage in efforts to expand protection to the greater park ecosystem outside of their boundaries (e.g., land stewardship agreements). The provincial Planning Act also provides protection for those wetlands that are deemed provincially significant and threatened by planning applications. Ultimately, however, although much is being done to protect habitat, this protection occurs at the scale of the fragments which are themselves under threat. The historic loss of connectivity and subsequent isolation of habitats and populations (Figure 6, 7 and 11) is not being addressed.

Within the Provincial Parks and Reserves where E. gloydi is found, the degree of habitat protection varies considerably, depending on both park classifications and management. Provincial Nature Reserves have the highest protection mandate and are relatively free from large-scale habitat disturbance. However, destruction of important microhabitats may occur due to unregulated use of motor vehicles (e.g., ATVs) and lack of enforcement. Provincial Parks with a “Recreation” designation provide the least protection of habitat because mandates for environmental protection are secondary to human use. Roads and trails in parks also contribute to mortality of snakes from both cars and bicycles. An example of conflicting land uses is the removal, for aesthetic reasons, of downed trees that could provide oviposition sites for foxsnakes.

Several conservation reserves along the Georgian Bay Coast harbour foxsnake populations. These reserves and Crown land in the region are managed by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Applications for development or potentially damaging activities on these lands require a comparatively rigorous environmental assessment.

On private lands, proposals or actions that invoke the Planning Act (e.g., lot severance, zoning change) set into motion a process whereby Ontario’s Provincial Policy Statement (PPS, Ontario 2005) issued under Section 3 of the Planning Act is supposed to provide for the protection of habitat for species of concern. Section 2.1.2 states that the diversity and connectivity of natural features in an area, and the long-term ecological function and biodiversity of natural heritage systems, should be maintained, restored or, where possible, improved, recognizing linkages between and among natural heritage features and areas, surface water features and ground water features. Section 2.1.3 states that development and site alteration shall not be permitted in…significant habitat of endangered species and threatened species. Section 2.1.4 states that development and site alternation shall not be permitted in…significant wildlife habitat … unless it has been demonstrated that there will be no negative impacts on the natural features or their ecological functions. Section 2.1.6 states that development and site alteration shall not be permitted on adjacent lands to the natural heritage features and areas, unless the ecological function of the adjacent lands has been evaluated and it has been demonstrated that there will be no negative impactson the natural features or on their ecological functions.

When triggered and properly implemented, the habitat protection measures of the PPS can provide for effective protection of important habitat for endangered and threatened species. Additionally, many site alterations detrimental to habitat do not invoke the Planning Act (e.g., road building on private land), and thus no evaluation of potential impacts is required. Moreover, many municipalities do not have site alteration by-laws thereby limiting the effectiveness of the PPS. Encouragingly, an updated Endangered Species Act (Ontario 2007) that mandates protection of habitat for both endangered and threatened species received Royal Assent 17 May 07. The habitat protection measures within the act are seemingly robust, and should be more effective than either the PPS or the previous Endangered Species Act.