Harris’s sparrow (Zonotrichia querula): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2017

Harris’s Sparrow

Special concern

2017

Table of contents

- Table of contents

- COSEWIC assessment summary

- COSEWIC executive summary

- Technical summary

- Wildlife species description and significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population sizes and trends

- Threats and limiting factors

- Protection, status and ranks

- Acknowledgements and authorities contacted

- Information sources

- Biographical summary of report writer(s)

- Collections examined

List of figures

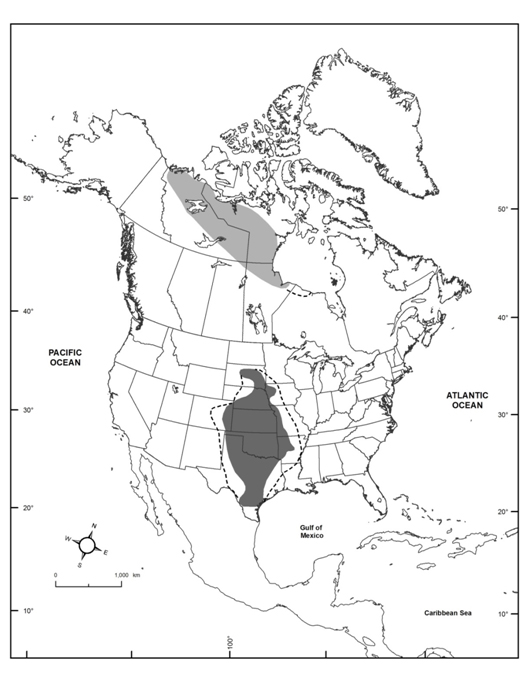

- Figure 1. Global distribution of Harris’s Sparrow during breeding (light gray; adapted from James et al. 1976; Cadman 2007) and wintering (dark gray; adapted from National Audubon Society 2015; eBird 2016; Norment et al. 2016) seasons, including irregular occurrences within dashed lines.

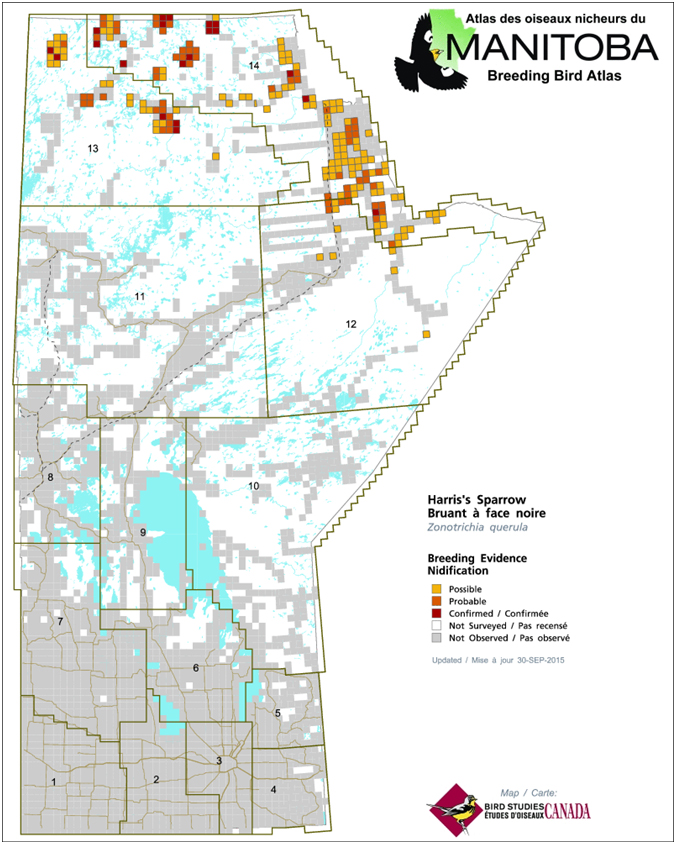

- Figure 2. Harris’s Sparrow breeding evidence during the Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas, 2010-2014 (MBBA 2015).

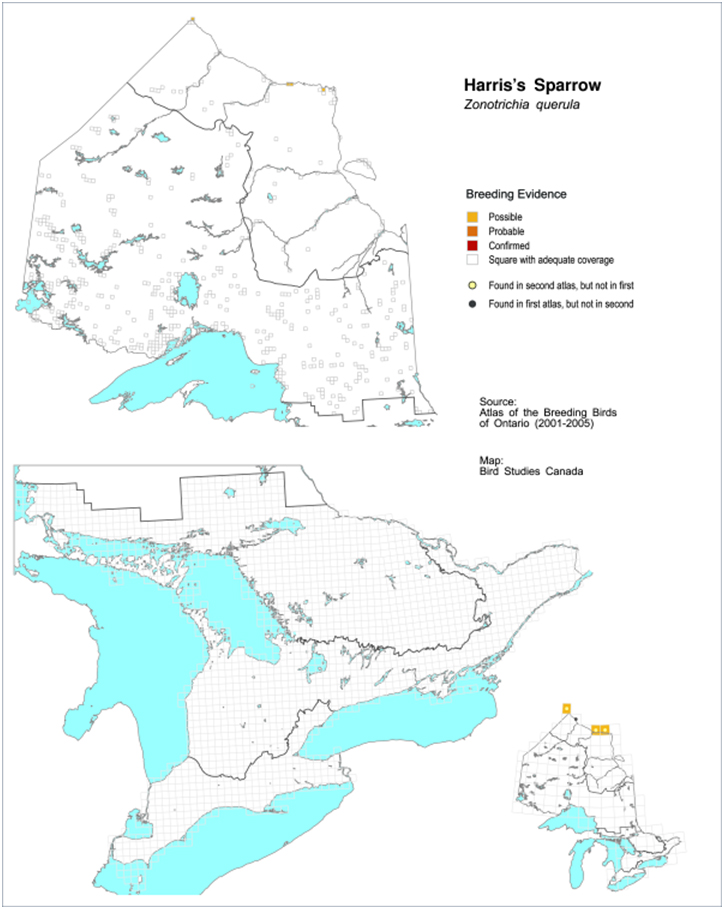

- Figure 3. Harris’s Sparrow breeding evidence during the 2nd (2001-2005) Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas, 2010-2014 (Cadman et al. 1987 and 2007).

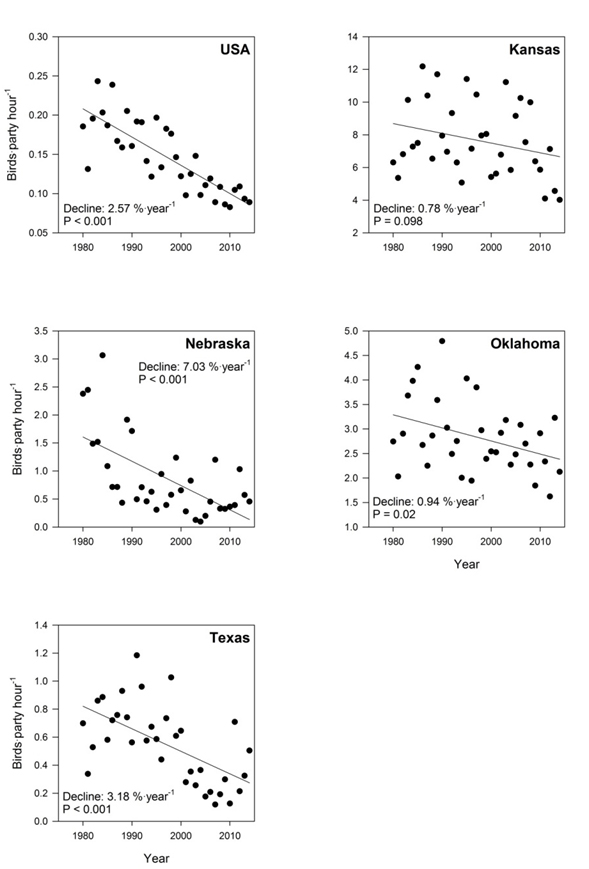

- Figure 4. Annual trends of Harris’s Sparrow observations (1980 – 2014) from the Christmas Bird Count (National Audubon Society 2015), in the USA, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas.

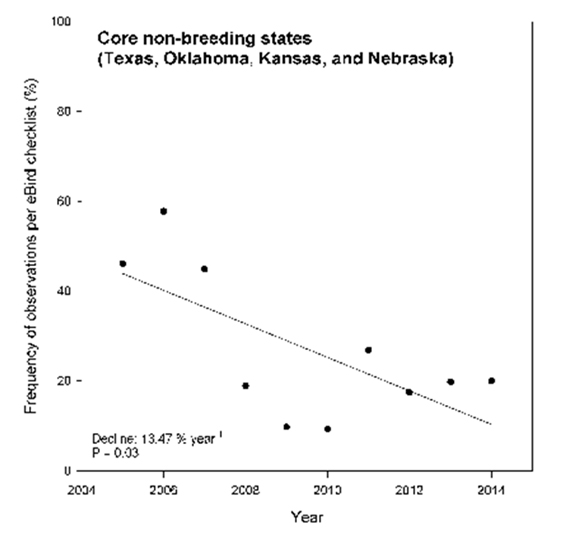

- Figure 5. eBird records (eBird 2016) of Harris’s Sparrow (2004 – 2014), December – February in the core non-breeding states within the USA.

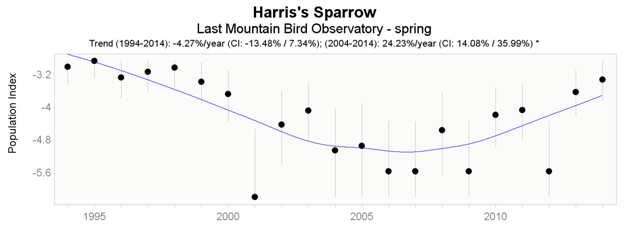

- Figure 6. Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory trends of Harris’s Sparrow (1994 – 2014) in spring.

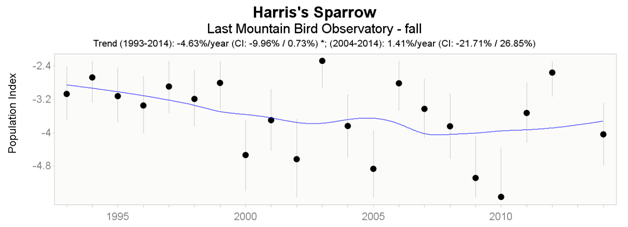

- Figure 7. Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory trends of Harris’s Sparrow (1993 – 2014) in fall.

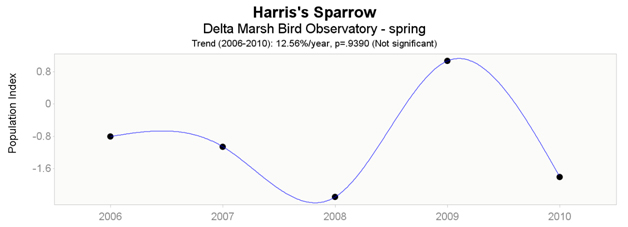

- Figure 8. Delta Marsh Bird Observatory trends of Harris’s Sparrow (2006 – 2010), spring.

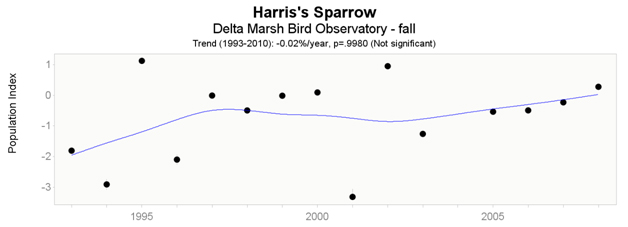

- Figure 9. Delta Marsh Bird Observatory trends of Harris’s Sparrow (1993 – 2010), fall.

List of tables

- Table 1. Summary of Harris’s Sparrow population trends over the past 10 and 35 years, according to the Christmas Bird Count (National Audubon Society 2015).

- Table 2. Summary of Harris’s Sparrow population trends over the past ten years, according to eBird (2016) data adjusted to the frequency of observation during the December 1 – February 28 period of 2004 – 2014.

List of appendices

- Appendix 1. Threats assessment worksheet for Harris’s Sparrow.

Document information

COSEWIC Assessment and status report on the Harris’s Sparrow (Zonotrichia querula) in Canada, 2017

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Canada

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Harris’s Sparrow Zonotrichia querula in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 36 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

Production note:

COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Natural Resource Solutions Inc. (Kenneth Burrell) for writing the status report on Harris’s Sparrow, Zonotrichia querula, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment and Climate Change Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Marcel Gahbauer, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

E-mail: COSEWIC E-mail

Website: COSEWIC

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bruant à face noire (Zonotrichia querula) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Harris’s Sparrow -- photo by Ron Ridout (with permission).

COSEWIC assessment summary

Assessment summary - November 2017

- Common name

- Harris’s Sparrow

- Scientific name

- Zonotrichia querula

- Status

- Special concern

- Reason for designation

- This northern ground-nesting bird is the only songbird that breeds exclusively in Canada. Data from Christmas Bird Counts in the US Midwest wintering grounds show a significant long-term decline of 59% over the past 35 years, including 16% over the past decade. The species may be affected by climate change on the breeding grounds, while threats on the wintering grounds include habitat loss, pesticide use, road mortality, and predation by feral cats.

- Occurrence

- Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario

- Status history

- Designated Special Concern in April 2017.

COSEWIC executive summary

Harris’s Sparrow

Zonotrichia querula

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Harris’s Sparrow is a large sparrow with a distinctive black hood and bib. Both sexes have similar plumage. Non-breeding and first-year birds are similar to each other in plumage, lacking much of the black bib and facial patterning found in breeding individuals. Harris’s Sparrow is the only passerine that breeds exclusively in Canada.

Distribution

Harris’s Sparrow is a long-distance temperate migrant that is found exclusively in North America. The species breeds along the tree-line in northern Canada (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and irregularly Ontario), and winters in the central Midwest region of the United States (regularly in Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and irregularly in Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, and South Dakota). Because of limited accessibility of the breeding range, relatively little is known about the species in Canada.

Habitat

Harris’s Sparrow favours a mosaic of upland and tundra, with scattered lakes. Breeding territories typically include coniferous trees; densities are highest where forest stands are dominated by spruce or tamarack, interspersed with shrubs typically <1 m tall. In winter and during migration, the species frequents a variety of habitats, with riparian thickets, grasslands, woodland edges, hedgerows, and willow thickets commonly used.

Biology

Harris’s Sparrow is a socially monogamous breeder that consumes fruits, seeds, and insects. Throughout the breeding season, the species is initially heavily dependent on fruits, before switching its diet as the breeding season progresses to include more insects and seeds as snow cover disappears. Nests are constructed and incubated by the female and are placed on the ground in densely concealed ground vegetation. Average clutch size is 4.07 eggs, with a range of 3 – 5 eggs. Incubation lasts 12 – 13.5 days and young fledge after 8.5 – 10 days. Research on the Thelon River in Northwest Territories documented a hatching rate of 76%, fledging rate of 62.5%, and overall nest success rate of 47.5%, with 2.07 fledged young per pair.

Population Sizes and Trends

The global population, which breeds exclusively in Canada, is estimated at 500,000 – 5,000,000 individuals, with the most recent estimates indicating ~2,000,000 individuals.

Christmas Bird Count (CBC) data indicate a significant long-term rate of annual decline of -2.58% between 1980 and 2014, amounting to a total population loss of 59% over the last 35 years. Over the most recent 10-year period (2004 to 2014), CBC data show a decline of -1.77% per year amounting to a cumulative loss of 16%.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Throughout the wintering grounds in the Midwestern United States, the conversion of grassland and fringe lands for agricultural purposes is thought to be a factor in the decline of Harris’s Sparrow. Pesticide use throughout the wintering grounds has been linked to declines in Harris’s Sparrow; while the relative influence of this factor is unknown, it is anticipated to be negative and potentially considerable in severity.

Within the breeding range, concerns include habitat loss linked to deforestation near the northern edge of the species’ range associated with forest fires, quarries and mine development, and climate change, which may reduce suitable breeding habitat while allowing ectoparasites and mammalian predators, such as Red Fox, to spread north.

More studies are needed to assess the species throughout its annual life cycle and assess the relative importance of different threats on its breeding and wintering grounds.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Harris’s Sparrow and its nest and eggs are protected in Canada under the Migratory Birds Convention Act. The Act prohibits the sale or possession of migratory birds and their nests, and any activities that are harmful to migratory birds, their eggs, or their nests, except as permitted under the Migratory Birds Regulations. It is protected in the United States under the Migratory Birds Treaty Act.

Harris’s Sparrow is ranked as globally secure by NatureServe. Within Canada the species is ranked as secure nationally, secure in Alberta and Saskatchewan and vulnerable in Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. COSEWIC assessed this species as Special Concern in April 2017.

Technical summary

- Scientific name:

- Zonotrichia querula

- English name:

- Harris’s Sparrow

- French name:

- Bruant à face noire

- Range of occurrence in Canada:

- Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario

Demographic information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time | 2 to 3 yrs |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | Yes, observed |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations] | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | 16% reduction observed over the most recent 10-year period of data from the Christmas Bird Count |

| [Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown, but long-term decline expected to continue unless threats are identified and addressed. |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown, but long-term decline expected to continue unless threats are identified and addressed. |

| Are the causes of the decline a. clearly reversible and b. understood and c. ceased? | a. Unknown b. No c. No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals | No |

Extent and occupancy information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence Based on a minimum convex polygon provided in Figure 1 | 1,368,784 km2 (breeding range) 1,377,973 km2 (wintering range) |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). |

>2,000 km2 |

| Is the population “severely fragmented” ie. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are (a) smaller than would be required to support a viable population, and (b) separated from other habitat patches by a distance larger than the species can be expected to disperse? | a. No b. No |

| !!!(use plausible range to reflect uncertainty if appropriate) | Unknown, but >10 |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | Unknown |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | Unknown |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? | N/A |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in !!!? | Unknown |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | Unknown |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | N/A |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in !!!? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of mature individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Population | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| blank cell | Crude estimate ranging between 500,000 – 5,000,000 (Blancher et al. 2007); more recent estimate of 2,000,000 based on Rosenberg et al. (2016). |

| Total | 2,000,000 |

Quantitative analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild. | Quantitative analysis not undertaken |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Was a threats calculator completed for this species and if so, by whom? | Yes, on September 26, 2016 by Kenneth Burrell, Dave Fraser, Marcel Gahbauer, Suzanne Carrière, Richard Elliot, Pam Sinclair, Myles Lamont, Chris Norment, Rudolf Koes, Jim Rising, Samuel Hache, Amy Ganton, Joanna James. Overall threat of high-medium, based on:

Habitat conversion for agriculture, renewable energy, fire and fire suppression, and climate change are among the other potential threats that may affect Harris’s Sparrow, but not enough is known to evaluate their effects at this time. |

Rescue effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | N/A. Species’ breeding range is found exclusively in Canada. |

| Is immigration known or possible? | N/A |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | N/A |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | N/A |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? !!! | N/A |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating? !!! | N/A |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink? !!! | N/A |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | N/A |

Data sensitive species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? | No; the species is widely distributed and still relatively common throughout the breeding range in Canada. |

Status history

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| COSEWIC: | Designated Special Concern in April 2017. |

Status and reasons for designation:

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status | Special Concern |

| Alpha-numeric codes | Not applicable |

| Reasons for designation: | This northern ground-nesting bird is the only songbird that breeds exclusively in Canada. Data from Christmas Bird Counts in the US Midwest wintering grounds show a significant long-term decline of 59% over the past 35 years, including 16% over the past decade. The species may be affected by climate change on the breeding grounds, while threats on the wintering grounds include habitat loss, pesticide use, road mortality, and predation by feral cats. |

Applicability of criteria

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals) | Not applicable, as the decline over the past 10 years is ~16%. |

| Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation) | Not applicable, given extensive distribution. |

| Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals) | Not applicable, given population estimate of ~2 million. |

| Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population) | Not applicable, given population estimate of ~2 million. |

| Criterion E (Quantitative Analysis) | Not assessed. |

COSEWIC history

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2016)

- Wildlife species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

-

Special concern (SC)

(Note: Formerly described as “Vulnerable” from 1990 to 1999, or “Rare” prior to 1990.) - A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

-

Not at risk (NAR)

(Note: Formerly described as “Not in any category”, or “No designation required.”) - A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

-

Data deficient (DD)

(Note: Formerly described as “Indeterminate” from 1994 to 1999 or “ISIBD” [insufficient scientific information on which to base a designation] prior to 1994. Definition of the [DD] category revised in 2006.) - A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species’ eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species’ risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife species description and significance

Name and classification

Scientific Name: Zonotrichia querula (Nuttall, 1840)

English Name: Harris’s Sparrow

French Name: Bruant à face noire

Class: Aves

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

Genus: Zonotrichia

Species: Zonotrichia querula

Classification follows the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU 1998; Chesser et al. 2015). No geographic variation or subspecies are recognized (AOU 1998; Norment et al. 2016). Currently there are five species within the genus Zonotrichia (AOU 1998).

Morphological description

Harris’s Sparrow is a large sparrow (body length: 17-20 cm, body mass: 30-45 g) with a distinctive facial and breast pattern. Both sexes have similar plumage. Breeding adults have a well-defined black hood and bib, which includes black throughout the front of the face and the top of the head extending to the nape and upper throat. Black streaking occurs throughout the breast and flanks. The bill and legs are a fleshy pink. The wings are dominated by two white wing bars, while the remainder of the wings and back are mottled brown and gray. Non-breeding and first-year birds are similar to each other in plumage, lacking much of the black bib and facial patterning found on breeding individuals. Variation in the amount of black in the face and bib occurs, with older birds and males typically showing more black, while the face is primarily brown and gray. Vocalizations for the species are similar to other species in the genus, specifically the first part of the White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) song. The song is described as a plaintive whistle by Semple and Sutton (1932) and a one-toned whistled “seeeeeee seeee seeee” by Sibley (2000). Aging of individuals, particularly first-year birds, is possible by examining retained juvenile flight feathers (Pyle 1997; Norment et al. 2016).

Population spatial structure and variability

No evidence exists for population structuring within the species’ population. The species’ population is contiguous throughout the breeding range; no significant barriers to dispersal and movement have been identified. There is a clinal increase in clutch size as latitude increases (Norment 1992a,b).

Designatable units

No subspecies have been recognized for Harris’s Sparrow (AOU 1998; Norment et al. 2016); all Harris’s Sparrows breeding in Canada are within a single population and therefore only one designable unit is considered in this report.

Special significance

Harris’s Sparrow is the only endemic breeding passerine in Canada (Norment et al. 2016). The species is one of the last North American songbird species to have its nests and eggs discovered, in 1931, with relatively little known about its basic breeding ecology until recently (Norment et al. 2016).

No Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge is currently available for this species.

Distribution

Global range

Harris’s Sparrow is a medium-distance temperate migrant that is found exclusively in North America. The species breeds along the treeline in northern Canada (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and irregularly Ontario), and winters in the central Midwest region of the United States (South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa). The core of the winter range includes north-central Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska (Figure 1). Migratory routes are not well understood, but are expected to follow a narrow band between the breeding and wintering grounds. Additionally, the species winters, as a vagrant, in scattered peripheral locations throughout the lower 48 contiguous US states and less so in southern Canada and extreme northern Mexico (National Audubon Society 2015; eBird 2016).

Long description for Figure 1

Map showing the global distribution of the Harris’s Sparrow in North America. The species breeds along the treeline in northern Canada (in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and irregularly Ontario) and winters in the central Midwest region of the United States (in South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa).

Canadian range

Harris’s Sparrow breeds principally near the treeline, in parts of the Southern Arctic, Taiga Plains, Taiga Shield, and Hudson Plains EcoZones, west of Hudson Bay (Government of Canada 2013).

In Manitoba, the species breeds in the Far North, where it is regularly observed along and west of the Nelson River, extending to the far northwestern corner of the province and northeastern Saskatchewan (eBird 2016; Norment et al. 2016; Figure 2). In Nunavut, the species breeds in the Kivalliq and Kitikmeot regions. Within the Kivalliq Region, it is found primarily in the southern two-thirds of the Region, as far north as Rankin Inlet, at which point the breeding range extends northwest from the coastline to an area east of Umingmaktok, in the Kitikmeot Region (eBird 2016; Norment et al. 2016). In Kitikmeot, Harris’s Sparrow is found along the Arctic Ocean coastline, west to Kugluktuk and Clifton Point (eBird 2016; Norment et al. 2016). In the Northwest Territories the species’ range extends west to the Mackenzie River delta, and possibly into extreme northeastern Yukon (Eckert pers. comm. 2015). The southwestern edge of the range extends from the northwestern Northwest Territories across the south of Great Bear Lake, to northeastern Saskatchewan (eBird 2016; Norment et al. 2016).

Data from the Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases (1981-1985 and 2001-2005; Cadman et al. 1987, 2007) and James et al. (1976) indicate that irregular breeding occurs at scattered locations near the Hudson Bay coast (Figure 3).

Long description for Figure 2

Map indicating the breeding range (using grid cells) of the Harris’s Sparrow in Manitoba, based on breeding bird atlas data from 2010 to 2014. The species is observed along and west of the Nelson River, extending to the far northwestern corner of the province.

Long description for Figure 3

Maps indicating the breeding range (using grid cells) of the Harris’s Sparrow in Ontario, based on breeding bird atlas data. The maps show that irregular breeding occurs at scattered locations near the Hudson Bay coast.

Extent of occurrence and area of occupancy

Extent of occurrence is estimated to be 1,368,784 km2 in the breeding range, and 1,377,973 km2 in the wintering range (Figure 1). Distribution within the breeding range is not sufficiently documented to calculate area of occupancy, but it is certainly >2,000 km2.

Search effort

Distributional data for Harris’s Sparrow in Canada predominantly come from the Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas (2015), conducted in 2010-2014, the Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre, and observations from individual observers contacted for the preparation of this status report (see Acknowledgements).

The distribution maps from NatureServe Explorer (2015) and Birds of North America (Norment et al. 2016) are considered the most reliable for the species, and have been corroborated with data from the Northwest Territories/Nunavut Bird Checklist Survey (ECCC 2016) and eBird (2016) for the past 10 years in June and July.

Habitat

Habitat requirements

Breeding habitat

Throughout their breeding range, Harris’s Sparrows favour the forest/upland tundra transition zone. Breeding territories typically include coniferous trees; densities are highest where forest stands are dominated by spruce (Picea sp.) and to a lesser extent Tamarack (Larix laricina), with shrubby understorey vegetation (Harper 1953; Gillespie and Kendeigh 1982; Norment 1992a; Norment et al. 2016). Densities have been observed to decline with decreasing tree and understorey vegetation abundance (Norment et al. 2016). The species infrequently nests in areas where trees are absent; in these cases shrub cover is particularly important for nest placement and concealment (Clarke 1944; Sealy 1967; Norment et al. 2016). Favoured breeding habitat typically has small, isolated forest stands (ranging from a small clump of trees to 12 ha) interspersed throughout the breeding territory (Norment 1992a; Norment et al. 2016).

Highest densities occur where vegetation composition is varied and shrubs are generally taller (i.e., >1m) (Obst pers. comm. 2015), with highest abundances occurring where forests are characterized as 10% Black Spruce (P. mariana) and White Spruce (P. glauca) forest, 27% Dwarf Birch (Betula glandulosa) – Willow (Salix sp.) shrublands, and 63% tundra (Norment 1992b; Norment et al. 2016). Breeding populations have been estimated to range from a low of 0.025 territorial males per ha in lowest density habitats (Harris et al. 1974) to 0.125 – 0.82 breeding pairs per ha in highest density habitats (Gillespie and Kendeigh 1982; Norment 1992b).

Subtle clinal variation occurs throughout the species’ breeding range with respect to vegetation found in their breeding territories (Norment et al. 2016). In the Northwest Territories the species generally nests in shrubby vegetation dominated by Dwarf Birch, alder (Alnus spp.), and willow (Semple and Sutton 1932; Harper 1953; Norment 1992b), while in Churchill, Manitoba the species is most common at the edge of spruce and tamarack forests (Gillespie and Kendeigh 1982), in clearings, and at the edges of burned areas (Semple and Sutton 1932; Norment et al. 2016).

Wintering and migration habitat

The species frequents a variety of habitats throughout the winter and migration periods, with riparian thickets, woodland edges, hedgerows, and willow thickets commonly used (NatureServe 2015). Studies conducted in Kansas (Graul 1967) and Oklahoma (Nice 1929; Bridgwater 1966) indicate the species favours disturbed areas, such as hedgerows, brush piles, and agricultural fields, as well as natural habitats such as secondary succession and riparian corridors (Norment et al. 2016).

Habitat trends

Breeding habitat

Human activities such as mining and road construction occur within the breeding range; the extent to which they affect breeding habitat remains unclear, but overall rate of change to breeding habitat is likely to be low.

Quantitative effects of climate change are not known; however, anecdotal evidence suggests that shifting of the treeline north may affect the species (Obst pers. comm. 2015), potentially both positively (e.g., increased abundance of shrub species beneficial to Harris’s Sparrows for foraging and nesting) and negatively (e.g., reduced suitable habitat at the southern edge of the species’ range; i.e., northern Manitoba). The amount and quality of breeding habitat for this species is not being monitored (trends are not available).

Wintering habitat

The winter range includes the central and southern Great Plains region of the USA, extending from South Dakota to Texas (Norment et al. 2016) where Harris’s Sparrows use open habitats, including riparian thickets, woodland edges, hedgerows, and willow thickets. The conversion of these types of habitat to agriculture and to a lesser extent urban sprawl is identified as a threat to the species, though it is unknown to what extent (NatureServe 2015).

Biology

Few recent studies have been conducted on Harris’s Sparrow in Canada. Past studies conducted by C. Norment in the Thelon River area, Northwest Territories, provide much of what is documented on the species’ breeding biology (e.g., Norment 1992a,b, 1993, 1994, 1995a, b). As a result, much of the information presented below draws on information summarized in the revised Birds of North America species account (Norment et al. 2016).

Life cycle and reproduction

Harris’s Sparrow is a socially monogamous breeder (Norment et al. 2016). Paired birds forage together, with the male following the female, most closely just prior to incubation (Norment et al. 2016). The species forms loose flocks in the late summer, just prior to fall migration (Norment et al. 2016).

Harris’s Sparrows generally arrive on their breeding territories in late May to early June (Norment et al. 2016). Nests are typically initiated in the second and third week in June (i.e., ~14 days after average arrival), or when snow-cover is ≤60% (NatureServe Explorer 2015; Norment et al. 2016). Nests have two layers: an inner layer composed primarily of dry grasses, mosses, and sedges, and an outer layer composed of lichens, mosses, and small twigs (Rees 1973). Females build the nests, incubate, and brood the young (Norment et al. 2016). Both sexes feed the young; however, males tend to do so less frequently, particularly early in the hatching stage (Norment et al. 2016). The species only initiates second broods if the first brood has failed before the eggs have hatched (Norment 1992b; Norment et al. 2016).

Norment (1992b) documented the incubation period as lasting 12 – 13.5 days and the nestling period 8.5 – 10 days. Average clutch size (n = 155) was 4.07 eggs, with a range from 3 – 5 eggs; timing of hatching was noted to be synchronous among nests (Norment 1992b). The hatching rate in Northwest Territories was 76%, fledging rate was 62.5%, and overall nest success (minimum one offspring fledged successfully) was 47.5%, with 2.07 young fledged per pair on average (Norment 1992b; NatureServe Explorer 2015; Norment et al. 2016). Fledgling mortality was noted to be primarily due to predation, with Arctic Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus parryii) and, to a lesser extent, Short-tailed Weasels (Mustela erminea) as the principal predators of young (NatureServe Explorer 2015).

Nests are always located on the ground and usually within dense ground vegetation for cover (Norment 1993). The probability of nest success increased with nest concealment (Norment 1993). Nests are often positioned under shrubs <1 m (NatureServe Explorer 2015; Norment et al. 2016). Plant species used for cover vary by latitude, but most are woody (Norment 1993). In Nunavut, Dwarf Birch (Betula pumila) is most commonly selected (68%; n = 65), while in Manitoba, it is Dwarf Labrador Tea (Rhododendron tomentosum) (32%; n = 26) (Norment 1993). In Northwest Territories, mean nest entrance orientation is at 140.5°, which is 170° away from the direction of prevailing storms (Norment 1993).

The age for birds to first breed is not known; however, it is believed to be one year, as for other Zonotrichia species (Norment 1992a; Chilton et al. 1995). The species has a sex ratio of 1:1 throughout established breeding territories (Norment et al. 2016).

The longevity record is 11 years, 8 months (Norment et al. 2016). Average survival of chicks from eggs to hatching ranged from 63.8% - 90.5% (Norment 1992b). Annual survival data indicate that adult survivorship averaged 38% over a 2-year study in Nunavut (Norment 1992b); the low estimate is likely a reflection of individuals shifting breeding sites. While generation time has not specifically been calculated, it is assumed to be 2-3 years, as for most other small passerines. One recorded hybrid with White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys) was collected at Long Point, Ontario (Payne 1979).

Food

Harris’s Sparrows consume fruits, seeds, and insects; employing similar feeding habits to other Zonotrichia species, feeding on the ground, where they scratch and kick ground refuse (Norment 1992a). They forage in shrubs and trees less frequently than on the ground (Nice 1929; Semple and Sutton 1932; Norment et al. 2016).

Harris’s Sparrows consume a wide variety of plant species, including sedges (Carex spp. and Cyperus spp.), bulrushes (Scirpus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), pigweed (Amaranthus spp.), lamb’s-quarters (Chenopodium spp.), blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), and bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) (Semple and Sutton 1932). Berries are particularly important to Harris’s Sparrow when the birds first reach the breeding grounds and insects have not yet emerged (Norment and Fuller 1997). Norment and Fuller (1997) found that fruits such as Blueberry (Vaccinium sp.), Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), and Bearberry (Arctostaphylus sp.) comprised 82% of stomach contents before birds nested. In the same study, Norment and Fuller (1997) found that arthropods comprised 72.5% of adult Harris’s Sparrows diet during the nestling period and 81.5% of nestling diets.

Physiology and adaptability

Relatively little information on the species’ physiology exists; Norment (1995a) determined optimum temperature for Harris’s Sparrows during incubation was between +10°C and +20°C, allowing females to leave the nest for longer periods to forage and to return less frequently to tend to eggs. The same study (Norment 1995a) found that temperatures above +20°C resulted in adults attending the nest more frequently in an effort to provide shade and to help regulate fledgling body temperature (Norment et al. 2016). Harris’s Sparrows were also found to be poorly adapted to extreme temperatures during nesting, specifically when temperature reached above +30°C and below -10°C (Norment et al. 2016).

During periods of inclement weather, birds abandon newly acquired breeding territories, returning to resume nesting after the inclement weather has passed (Norment et al. 2016). This strategy is beneficial when birds have not initiated egg-laying; however, it is detrimental and can be fatal to young birds or eggs recently laid.

Dispersal and migration

After fledging, juveniles disperse up to 500 m from natal sites; young and some adults may disperse over longer distances within the breeding range but this has not been documented (e.g., there are no banding encounters involving longer distance movements of birds captured or banded within Canada; Brewer et al. 2006; Norment et al. 2016).

Norment (1994) documented a 38% return rate for banded birds in NWT, with no substantial difference by sex. Adults which were unsuccessful nesters returned in subsequent years at much lower rates than successful birds (Norment 1994).

Based on banding and observation data (Brewer et al. 2006; eBird 2016) most birds are expected to migrate north and south through a narrow band between the breeding and wintering grounds. However, single individuals are observed frequently outside the expected wintering grounds and migration corridor.

Interspecific interactions

Throughout the breeding grounds the species is socially monogamous and forms loose flocks prior to departing for fall migration (Norment et al. 2016). During spring and fall migration and winter the species joins mixed-species flocks which may include White-crowned Sparrow, American Tree Sparrow (Spizelloides arborea), and Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) (Shuman et al. 1992; Thompson 1994; Robel et al. 1997).

Population sizes and trends

Sampling effort and methods

Harris’s Sparrow is one of the least studied passerines in North America, with only a few programs adequately designed to estimate population size or trends. Due to its remote northern breeding range, the species is not effectively surveyed by the Breeding Bird Survey, which typically provides population trend data for songbirds. Surveys providing relevant data are presented below.

The Christmas Bird Count (CBC)

The Christmas Bird Count originated in 1900 and tracks winter bird populations through annual surveys within fixed 24 km diameter count circles (National Audubon Society 2015). This program provides population and abundance estimates on most wintering landbirds in Canada and the USA, including Harris’s Sparrow. Within each count circle, CBC volunteers record all bird species and individuals on a single day between 14 December and 5 January of a given year. With the breeding grounds of Harris’s Sparrow almost completely unmonitored, the CBC provides the most reliable source of data for analyzing population trends.

CBC coverage in the Harris’s Sparrow’s core non-breeding range (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska) was relatively limited until 1980. Trend analyses were conducted using data from 1980 – 2014, and were analyzed in relation to an adjusted observation value for effort (birds per party hour). The analysis also looked at the entire winter range for the same timeframe, to capture the overall trend and to account for potentially substantial numbers of birds falling outside the core non-breeding range. State-specific analyses were also conducted for five states peripheral to the core non-breeding range; however, sample sizes were sufficient for generating trends only in Missouri and Iowa. Other states (e.g., Colorado, South Dakota, Arkansas) where Harris’s Sparrow occurs with some regularity during winter were reviewed, but sample sizes were too small to provide meaningful results or generate trends, and are therefore not discussed further. Analyses were not conducted for Canada or Mexico, given the small sample size for these regions.

The CBC trend analysis consisted of fitting simple linear regressions through effort-adjusted annual indices (birds per party hour), with trends expressed as geometric mean rates of change between the first year value of the line and the final year value (Smith et al. 2014). Annual indices consisted of single data points for each region-year, calculated as averages of all the CBC count circles per year, as available for download using the historical results by species filter from National Audubon Society (2015). Statistical significance was determined by P-values (P<0.05) describing the slope of the regression line. Data were analyzed using R v.3.2.3 (R Core Team 2015).

Manitoba breeding bird atlas

The Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas (MBBA), provides the first systematic mapping of the province’s breeding birds. Field data were collected over 2010 – 2014 (Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas 2015). Coverage varied, especially in the Far North within the breeding range of Harris’s Sparrow; overall 30% of atlas squares (10 km x 10 km) received at least some coverage, and effort of ≥10 hrs was considered adequate to detect the majority of species occurring in a square (Artuso pers. comm. 2016).

As this is the first breeding bird atlas for the province, data collected were only used to determine occurrence and abundance, but not trends.

eBird

eBird is a real-time, interactive, online checklist program, to which observers submit their observations (eBird 2016). The data can be compiled to summarize distribution and abundance patterns, and can then be used for conservation and educational purposes (eBird 2016). This program is relatively young (created in 2002) and usership has steadily increased since inception (eBird 2016). Although eBird data contain substantial bias in the form of false-positives, it was determined that these data should be presented, given the paucity of other data for Harris’s Sparrow and to compare with CBC data trends.

For the purpose of this status report, data were analyzed from the species’ core non-breeding range in the United States (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska) as well as these states individually, and two peripheral states (Iowa and Missouri) with sufficient quantities of data. Data were compiled for the months of December through February, and were used to generate the mean frequency of observations per checklist, to determine a trend analysis from 2004 – 2014.

Statistical modelling was conducted in the same manner as the CBC data analysis described above, using frequency of checklist observation as the method to calculate year-adjusted trends.

Canadian migration monitoring network (cmmn)

The Canadian Migration Monitoring Network is a joint program, run by individual observatories in collaboration with Bird Studies Canada and the Canadian Wildlife Service, aimed at monitoring landbird populations throughout Canada (Bird Studies Canada 2016). The CMMN includes over 25 monitoring stations throughout Canada that track landbird populations through standardized monitoring programs, such as mist-netting and daily censuses (Bird Studies Canada 2016).

Data were analyzed from the only CMMN sites within the narrow migration corridor of Harris’s Sparrow, Delta Marsh in Manitoba and Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory in Saskatchewan. Data from Delta Marsh Bird Observatory were analyzed from 2006 – 2010 in spring and 1993 – 2010 in fall. Data from Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory were analyzed from 1994 – 2014 in spring and 1993 – 2014 in fall.

Trend analyses were generated by NatureCounts (2016), using the ‘Population Trends’ tool. Statistical modelling was conducted using census and banding totals to calculate year-adjusted trends.

Abundance

Based principally on data extrapolated from the Christmas Bird Count, an estimate by Blancher et al. (2007) suggested that the population was 500,000 – 5,000,000; however, it should be noted that data for this species were limited. Based on more current data, the revised population estimate by Rosenberg et al. (2016) is a population of approximately 2,000,000 individuals. Given that the entire breeding population occurs within Canada, this estimate equates to the Canadian population.

Preliminary results from the Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas suggest that 200 atlas squares (10 x 10 km) recorded breeding evidence for Harris’s Sparrow. Breeding evidence for the species was most commonly recorded as possible (118 squares), with probable (62) and confirmed (20) squares less common (MBBA 2015). In atlas squares where Harris’s Sparrows were observed, the species was observed on 44.4% of all point counts (n = 1,096), with a mean abundance of 0.71 birds per count (n = 2,469). Additional data shared by the Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas indicate that the probability of detection is high (i.e., >70%) within extreme northwestern Manitoba, even along the Hudson Bay coast east of the Nelson River to the Ontario border, despite the scarcity of previous observations there (Artuso pers. comm. 2016, unpubl.).

Studies conducted by Gillespie and Kendleigh (1982) and Norment (1992b) in Manitoba and Northwest Territories suggest that densities range from 0.125 – 0.82 pairs per ha in suitable habitat. However, average density throughout the species’ range remains unknown.

Fluctuations and trends

Christmas bird counts

Data from the Christmas Bird Count (CBC; Table 1; Figure 4) indicate that over 35 years (1980 – 2014), Harris’s Sparrow has experienced a statistically significant long-term decline of -2.58% per year (P <0.001), representing a reduction in the total population through this timeframe of 59%. This rate of decline appears to have lessened in the past 10 years (-1.77% per year, P=0.211), equating to a statistically not significant estimated reduction in the total population of 15% from 2004 to 2014.

CBC data from three of the four core non-breeding states (Texas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska) indicate significant long-term annual rates of decline (-3.18%, -0.94%, -7.03%, respectively), while in the remaining state (Kansas), there has been a statistically significant short-term (10 year) decline (-9.48% per year).

Trends from the peripheral states examined (Missouri and Iowa) were predominantly positive, but not significant. These states account for a small proportion of wintering Harris’s Sparrows and do not reflect the overall trend of the species.

| Region | Period | Annual rate of change (%/year) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 1980 – 2014 | -2.58 | ** |

| USA | 2004 – 2014 | -1.77 | ns |

| Texas | 1980 – 2014 | -3.18 | ** |

| Texas | 2004 – 2014 | +14.17 | ns |

| Oklahoma | 1980 – 2014 | -0.94 | * |

| Oklahoma | 2004 – 2014 | -1.55 | ns |

| Nebraska | 1980 – 2014 | -7.03 | ** |

| Nebraska | 2004 – 2014 | +2.96 | ns |

| Kansas | 1980 – 2014 | -0.78 | ns |

| Kansas | 2004 – 2014 | -9.48 | * |

| Missouri | 1980 – 2014 | +0.33 | ns |

| Missouri | 2004 – 2014 | +11.34 | ns |

| Iowa | 1980 – 2014 | -1.01 | ns |

| Iowa | 2004 – 2014 | +10.66 | ns |

Long description for Figure 4

Charts showing annual trends in observations of the Harris’s Sparrow (birds per party hour) from 1980 to 2014, based on the Christmas Bird Count, for the United States, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas.

The only significant trend over the short-term period was in Kansas (-9.48%; P <0.05). In Texas, a dramatic increase of 14.2% per year has been observed; however, it is not statistically significant at ɑ=0.05 (P = 0.099). Potential explanations for this include concentration of the species in suitable habitat, as a result of habitat losses (due to agricultural conversion) in the northern extent of its wintering range, or harsher winters forcing the species farther south in recent winters. While there appears to be some plasticity in winter distribution from year to year, no consistent change in area of winter occurrence is evident.

eBird

For the purpose of this status report, data from eBird have been compared with data from the CBC. Based on trend analyses for the 2004 – 2014 time period, significant trends were noted for the core non-breeding states overall (-13.47%, P=0.031; Figure 5) as well as Missouri (+11.09%, P=0.035) (Table 2). While the downward trend for the core wintering states as a group is larger than that indicated by the CBC, both programs point to significant overall declines over the short or long term. Non-significant declining trends were noted for Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Iowa, while observations in Nebraska increased.

Long description for Figure 5

Chart showing eBird records (eBird 2016) of the Harris’s Sparrow from 2004 to 2014 (December to February period) in the core non-breeding states within the United States.

| Region | Period | Annual rate of change (%/year) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core non-breeding states | 2004 – 2014 | -13.47 | * |

| Texas | 2004 – 2014 | -1.91 | ns |

| Oklahoma | 2004 – 2014 | -2.39 | ns |

| Nebraska | 2004 – 2014 | +8.16 | ns |

| Kansas | 2004 – 2014 | -1.54 | ns |

| Missouri | 2004 – 2014 | +11.09 | * |

| Iowa | 2004 – 2014 | -4.38 | ns |

Canadian migration monitoring network (cmmn)

Data from the CMMN indicate that significant trends were detected for Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory, Saskatchewan, but not from Delta Marsh Bird Observatory, Manitoba. At Last Mountain Lake, Harris’s Sparrow has undergone a significant decline throughout the fall long-term dataset (1993 – 2014); however, both spring (Figure 6) and fall (Figure 7) datasets indicate a short-term (2004 – 2014) increase (24.23% and 1.41% respectively), with the spring trend being significant.

Long description for Figure 6

Chart illustrating trend in the population of the Harris’s Sparrow recorded at the Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory in spring from 1994 to 2014.

Long description for Figure 7

Chart illustrating trend in the population of the Harris’s Sparrow recorded at the Last Mountain Lake Bird Observatory in fall from 1993 to 2014.

Data from Delta Marsh Bird Observatory indicate non-significant trends for both spring (short-term; Figure 8) and fall (long-term; Figure 9) datasets. Spring data (2004 – 2010) indicate an increase of 12.56% per year, while fall data (1993 – 2010) indicate a decrease of -0.02% per year.

Long description for Figure 8

Chart illustrating trend in the population of the Harris’s Sparrow recorded at the Delta Marsh Bird Observatory in spring from 2006 to 2010.

Long description for Figure 9

Chart illustrating trend in the population of the Harris’s Sparrow recorded at the Delta Marsh Bird Observatory in fall from 1993 to 2010.

Rescue effect

Not applicable. Harris’s Sparrow is an endemic breeding species in Canada; as such there is no potential for rescue from outside populations.

Threats and limiting factors

Threats are described below and summarized in Appendix 1 based on a modified version of the IUCN-CMP (World Conservation Union-Conservation Measures Partnership) unified threats classification system (COSEWIC 2014), which resulted in an overall score for Harris’s Sparrow of high to medium.

Category 9.3: Agricultural and forestry effluents (low to high threat)

Pesticide use throughout the wintering grounds has been linked to declines in grassland birds (Norment pers. comm. 2016). Neonicotinoids in particular have been implicated in widespread declines of a variety of taxa in the last decade (Hallmann et al. 2014; Gibbons et al. 2015). The degree to which pesticides have historically or are currently affecting Harris’s Sparrow is unclear (Norment et al. 2016), but severity is likely slight at minimum, and could be moderate to serious.

Category 1.1: Housing and urban areas (low threat)

Residential and, to a lesser extent, commercial developments may be removing suitable wintering habitat for Harris’s Sparrow (Norment et al. 2016); however, development is largely confined to the fringes of existing urban areas. Window kills may represent the greatest concern with respect to this threat (Bracey et al. 2016); however, no studies have specifically documented the frequency of window kills of Harris’s Sparrow.

Category 4: Transportation and service corridors (low threat)

Most Harris’s Sparrows are exposed to roads on their wintering grounds, and as terrestrially foraging birds, they may be at risk of vehicle collisions (Molhoff 1979), though only a small percentage of individuals are likely to be affected, and the overall effect is likely low. Transmission and distribution lines are unlikely to pose more than a negligible collision risk and may actually be neutral or beneficial to Harris’s Sparrow on the wintering grounds by providing suitable habitat (Norment et al. 2016).

Category 8.1: Invasive non-native/alien species (low threat)

Cat predation is a possible threat on wintering grounds, given the overall extent of this issue and the particular vulnerability of birds that forage terrestrially (Blancher 2013; Loss et al. 2013); while no reports have specifically addressed cat predation on Harris’s Sparrow to date, it is nonetheless likely a credible concern.

Negligible and unknown threats:

Increases in the population of various raptors (e.g., Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus), Cooper’s Hawk (A. cooperii), and Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus)) may be resulting in greater predation risk on Harris’s Sparrow through its annual cycle (Sauer et al. 2014), although it is unclear to what extent, and this threat is currently assessed as unknown.

The conversion of grassland and fringe lands for agricultural purposes in the Midwestern United States could be one of the most important factors in the Harris’s Sparrow’s decline (Norment pers. comm. 2016; Norment et al. 2016). Within the species’ northern wintering range limit (i.e., Nebraska, South Dakota, Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas), approximately 530,000 ha of grass-dominated land cover was converted to cropland between 2006 and 2011 (Wright and Wimberly 2013); similar changes have been documented in the core wintering range in Texas, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma and are negatively affecting a suite of grassland species in this region (Coppedge et al. 2001; Evans and Potts 2015). Clearing of hedgerows and other shelterbelts in association with agricultural intensification and the reduction of fringe lands may be particularly detrimental towards the species (Norment et al. 2016). However, because Harris’s Sparrow uses open habitat and may feed on waste grain, the net effect of agriculture (Threat Category 2) is unknown at this time.

Oil and gas and renewable energy developments (Threat Category 3) may represent potential threats to a wide group of species, including Harris’s Sparrow, given the large areas required for infrastructure placements (Preston and Kim 2016) and potential causes of mortality, especially at wind energy facilities (Zimmerling et al. 2013; Bird Studies Canada et al. 2016). However, these potential impacts have not been studied with respect to Harris’s Sparrow in particular and it has been noted that right-of-way areas may actually be beneficial for the species (Norment pers. comm. 2016); therefore these effects are currently considered negligible to unknown. Effects of mining are considered negligible, since up to 2.8% of the Harris’s Sparrow’s breeding range is within 10 km of mines or exploratory quarries (Fournier and Carrière pers. comm. 2016), but the primary effect of vegetation clearing for mines would be over a smaller area and associated impacts, such as increased vehicle traffic, would be increased.

Within the breeding range, fire has potential to negatively affect nesting success in a given year (Black and Bliss 1980; Arsenault and Payette 1992; Flannigan et al. 2001), but also to positively affect the species through creating habitat openings suitable for nesting. As such, the net effects of fire and fire suppression (Threat Category 7.1) are considered unknown.

Climate change (Threat Category 11) may reduce the forest-tundra zone located along the southern edge of the species’ breeding range and potentially result in a geographic shift northwards (Rizzo 1988; Zoltai 1988; Payette et al. 2001). The species’ response to treeline shifts northward is supported through the change in observations of the species in the Churchill, MB region dating back to the 1930s, when the species was more common, compared to the present day (Jehl and Smith 1970; Jehl 2004; Di Labio pers. comm. 2015). Additionally, climate change may result in more severe weather events which could have negative impacts on survival rates of nestlings (Norment et al. 2016). Range expansions of mammalian predators, such as Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) (Naughton 2012), and flying ectoparasites (e.g., biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) and mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) (Tomás et al. 2008) may result from climate change, and negatively impact nestling Harris’s Sparrows.

Protection, status and ranks

Legal protection and status

In Canada, Harris’s Sparrow and its nest and eggs are protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act (MBCA 1994). The MBCA prohibits the sale or possession of migratory birds and their nests, and any activities that are harmful to migratory birds, their eggs, or their nests, except as permitted under the Migratory Bird Regulations. It is similarly protected in the United States under the Migratory Birds Treaty Act (1918).

Non-legal status and ranks

Harris’s Sparrow is ranked as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List by BirdLife International (2015) and Globally Secure (G5; reviewed 1996) by NatureServe Explorer (2015). In Canada the species is ranked as Secure, Breeding and Nonbreeding (N5B and N5N); within Nunavut the species is not ranked (SNR), in Saskatchewan it is ranked Secure (S5), while in Manitoba and the Northwest Territories the species is listed as Vulnerable (S3; NatureServe Explorer 2015). Within Texas, the species is ranked as Apparently Secure (S4; NatureServe Explorer 2015). The species has not been ranked elsewhere.

Habitat protection and ownership

Harris’s Sparrow is reported to breed in Wapusk National Park in Manitoba and likely also does in Tuktut Nogait National Park in Northwest Territories. Individuals may pass through other protected areas during migration or on the wintering grounds, but overall there is limited legal protection of habitat throughout the Harris’s Sparrow’s annual range.

Acknowledgements and authorities contacted

Many people responded to a general request for information on Harris’s Sparrow in Canada and the USA, including the following people: Ken Abraham, Christian Artuso, Bruce Bennett, David Britton, Dick Cannings, Syd Cannings, Suzanne Carrière, Vanessa Charlwood, Mike Chutter, Bruce Di Labio, Kiel Drake, Cameron Eckert, Bonnie Fournier, Marcel Gahbauer, Samuel Hache, Audrey Heagy, Reid Hildebrandt, Rudolf Koes, Tom Jung, Bruce MacDonald, Scott MacDougall-Shackleton, Stuart Mackenzie, Jon McCracken, Patrick Nantel, Chris Norment, Joachim Obst, Rhiannon Pankratz, Lisa Pirie-Dominix, Jennie Rausch, James Rising, Rich Russell, Pamela Sinclair, Sonia Schnobb, Don Sutherland, Doug Tate, Phil Taylor, Doug Tozer, and Ken Tuininga. In addition to those who all provided information, the report writer would like to thank the appropriate Conservation Data Centres, Natural Heritage Information Centres, and the Parks Canada Agency for input on the species.

This report was greatly aided by comments received from the following people: Mike Burrell, Richard Elliot, Marcel Gahbauer, Elaine Gosnell, Lillian Knopf, Nathan Miller, and David Stephenson.

Doug Tozer kindly helped with the statistical analysis of the Christmas Bird Count data, which was integral to this status report. Lillian Knopf created Figures 4 and 5. Gerry Schaus created Figure 1 and completed the EOO calculation, per guidance from Jenny Wu.

Information sources

American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). 1998. Check-list of North American birds: the species of birds of North America from the Arctic through Panama, including the West Indies and Hawaiian Islands. Seventh edition, American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

Arsenault, D., and S. Payette. 1992. A post-fire shift from lichen-spruce to lichen-tundra vegetation at tree line. Ecology 73:1007-1018.

Artuso, C., pers. comm. 2016. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. January 2016. Manitoba Projects Manager, Bird Studies Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

BirdLife International. 2015. Species factsheet: Zonotrichia querula. Web site: http://www.birdlife.org [accessed December 2015].

Bird Studies Canada. 2016. About the Canadian Migration Monitoring Network. Web site: http://www.birdscanada.org/volunteer/cmmn/index.jsp?targetpg=about [accessed October 2016].

Bird Studies Canada, Canadian Wind Energy Association, Environment Canada, and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2016. Wind energy bird and bat monitoring database summary of the findings from post-construction monitoring reports. July 2016. 47pp. Web site: http://www.bsc-eoc.org/birdmon/wind/resources.jsp?dir=reports [accessed October 2016].

Black, R.A., and L.C. Bliss. 1980. Reproductive ecology of Picea mariana (Mill.) BSP, at tree line near Inuvik, Northwest Territories, Canada. Ecological Monographs 50:331-354.

Blancher, P.J., K.V. Rosenberg, A.O. Panjabi, B. Altman, J. Bart, C.J. Beardmore, G.S. Butcher, D. Demarest, R. Dettmers, E.H. Dunn, W. Easton, W.C. Hunter, E.E. Iñigo-Elias, D.N. Pashley, C.J. Ralph, T.D. Rich, C.M. Rustay, J.M. Ruth, and T.C. Will. 2007. Guide to the Partners in Flight Population Estimates Database. Version: North American Landbird Conservation Plan 2004. Partners in Flight Technical Series No 5.

Blancher, P.J. 2013. Estimated number of birds killed by house cats (Felis catus) in Canada. Avian Conservation and Ecology 8(2): 3.

Bracey, A.M., M.A. Etterson, G.J. Niemi, and R.F. Green. 2016. Variation in bird-window collision mortality and scavenging rates within an urban landscape. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128:355-367.

Brewer, D., A. Diamond, E.J. Woodsworth, B.T. Collins, and E.H. Dunn. 2006. Canadian Atlas of Bird Banding. Volume 1: Doves, Cuckoos, and Hummingbirds through Passerines, 1921-1995, 2nd edition. Web site: http://www.ec.gc.ca/aobc-cabb/index.aspx?lang=En [accessed November 2015].

Bridgwater, D.D. 1966. Winter movements and habitat use by Harris' sparrow, Zonotrichia querula (Nuttall). Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 46:53-59.

Cadman, M.D., P.F.J. Eagles, and F.M. Helleiner (eds.). 1987. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario. University of Waterloo Press, Waterloo, Ontario. 617 pp.

Cadman, M.D., D.A. Sutherland, G.G. Beck, D. Lepage, and A.R. Couturier, eds. 2007. Atlas of the Breeding Birds Of Ontario, 2001-2005. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists’, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ontario Nature, Toronto, Ontario. xxii + 706 pp.

Cadman, M.D. 2007. Harris’s Sparrow, pp. 568-569 in Cadman, M.D., D.A. Sutherland, G.G. Beck, D. Lepage, and A.R. Couturier, eds. Atlas of the Breeding Birds Of Ontario, 2001-2005. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists’, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ontario Nature, Toronto, Ontario. xxii + 706 pp.

Carrière, S., pers. comm. 2016. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. September 2016. Wildlife Biologist, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.

Chesser, R.T., R.C. Banks, K.J. Burns, C. Cicero, J.L. Dunn, A.W. Kratter, I.J. Lovette, A.G. Navarro-Sigüenza, P.C. Rasmussen, J.V. Remsen, Jr., J.D. Rising, D.F. Stotze, and K. Winker. 2015. Fifty-sixth Supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds. Auk 132:748-764.

Chilton, G., M.C. Baker, C.D. Barrentine, and M.A. Cunningham. 1995. White-crowned Sparrow (Zontotrichia leucophrys), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Web site: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/183 [accessed October 2016].

Clarke, C.H.D. 1944. Notes on the status and distribution of certain mammals and birds in the Mackenzie River and western arctic area in 1942 and 1943. Canadian Field-Naturalist 58:97-103.

Coppedge, B.R., D.M. Engle, R.E. Masters, and M.S. Gregory 2001. Avian response to landscape change in fragmented southern Great Plains grasslands. Ecological Applications 11:47-59.

Di Labio, B., pers. comm. 2015. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. July 2015. Bird Guide, Di Labio Birding, Ottawa, Ontario.

eBird. 2016. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Web site: http://www.eBird.org [accessed August 2016].

Eckert, C., pers. comm. 2015. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. July 2015. Conservation Biologist, Government of the Yukon, Whitehorse, Yukon.

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). 2016. eBird Canada (Northwest Territories/Nunavut). Web site: https://www.ec.gc.ca/reom-mbs/default.asp?lang=En&n=60E48D07-1 [accessed October 2016]..

Evans, S.G., and M.D. Potts. 2015. Effect of agricultural commodity prices on species abundance of US grassland birds. Environmental and Resource Economics 62:549-565.

Flannigan, M., I. Campbell, M. Wotton, and C. Carcaillet. 2001. Future fire in Canada's boreal forest: paleoecology results and general circulation model - regional climate model simulations. Canadian Journal of Forest Research-Revue Canadienne De Recherche Forestière 31:854-864.

Gibbons, D., C. Morrissey, and P. Mineau. 2015. A review of the direct and indirect effects of neonicotinoids and fipronil on vertebrate wildlife. Environmental Science and Pollution Resources 22:103-118.

Gillespie, W.L., and S.C. Kendeigh. 1982. Breeding bird populations of northern Manitoba. Canadian Field-Naturalist 96:272-281.

Government of Canada. 2013. EcoZones, EcoRegions, and EcoDistricts. Web site: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/nsdb/ecostrat/hierarchy.html [accessed December 2015].

Graul, W.D. 1967. Population movements of the Harris’s Sparrow and tree sparrow in eastern Kansas. Southwestern Naturalist 12:303-310.

Hallmann, C.A., R.P.B. Foppen, C.A.M. van Turnhout, H. de Kroon, and E. Jongejans. 2014. Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentrations. Nature 511:341-343.

Harris, W.C., E.A. Johnson, S.J.B. Johnson, and K.M. Traynor. 1974. Upland lichen woodland. American Birds 28:1048-1049.

Harper, F. 1953. Birds of the Nueltin Lake expedition. American Midland Naturalist 49:1-116.

James, R.D., P.L. McLaren, and J.C. Barlow. 1976. Annotated checklist of the birds of Ontario. Life Science Miscellaneous Publications, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario.

Jehl, J.R., and B.A. Smith. 1970. Birds of the Churchill Region, Manitoba. Manitoba Museum of Nature, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Jehl, J. 2004. Birdlife of the Churchill Region: status, history, biology. Manitoba Special Conservation Fund and Churchill Northern Studies Center, Churchill, Manitoba.

Loss, S.R., T. Will, and P.P. Marra. 2013. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife in the United States. Nature Communications 4(1396) (doi:10.1038/ncomms2380).

Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas (MBBA). 2015. Welcome to the Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas. Web site: http://www.birdatlas.mb.ca/ [accessed December 2015].

Migratory Birds Convention Act (MBCA). 1994. Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994. Web site: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/M-8.01/ [accessed December 2015]..

Mollhoff, W. 1979. Tower kills. Nebraska Bird Review 47:58.

National Audubon Society. 2015. The Christmas Bird Count Historical Results. Web site: http://www.christmasbirdcount.org [accessed November 2015].

NatureCounts. 2016. Canadian Migration Monitoring Network: Population trends and seasonal abundance. Web site: http://www.bsc-eoc.org/birdmon/cmmn/popindices.jsp [accessed October 2016].

NatureServe Explorer. 2015. Harris’s Sparrow Zonotrichia querula. Web site: http://explorer.natureserve.org/servlet/NatureServe?searchName=Zonotrichia%20querula [accessed December 2015].

Naughton, D. 2012. The natural history of Canadian mammals. Canadian Museum of Nature. Ottawa, Ontario. 824pp.

Nice, M.M. 1929. The Harris' sparrow in central Oklahoma. Condor 31:57-61.

Norment, C.J. 1992a. The comparative breeding ecology of the Harris's Sparrow (Zonotrichia querula) and White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys) in the Northwest Territtories, Canada. PhD Thesis. University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

Norment, C.J. 1992b. Comparative breeding biology of Harris's Sparrows (Zonotrichia querula) and Gambel's White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii) in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Condor 94:955-975.

Norment, C.J. 1993. Nest-site characteristics and nest predation in Harris's Sparrows and White-crowned Sparrows in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Auk 110:769-777.

Norment, C.J. 1994. Breeding site fidelity in Harris' Sparrows, Zonotrichia querula, in the Northwest Territories. Canadian Field-Naturalist 108:234-236.

Norment, C.J. 1995a. Incubation patterns in Harris’ Sparrows and White-Crowned Sparrows in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Journal of Field Ornithology 66:553-563.

Norment, C.J. 1995b. Prebasic (postnuptial) molt in free-ranging Harris’s Sparrows, Zonotrichia querula, in the Northwest Territories, Canada. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 109:470-475.

Norment, C.J. 2003. Patterns of nestling feeding in Harris's Sparrows, Zonotrichia querula and White-crowned Sparrows, Z. leucophrys, in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 117:203-208.

Norment, C., pers. comm. 2016. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. September 2016. Professor and Chair, Dept. of Environmental Science and Biology, The College at Brockport, State University of New York, Brockport, New York.

Norment, C.J. and M.E. Fuller. 1997. Breeding-season frugivory by Harris's sparrows (Zonotrichia querula) and white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) in a low-arctic ecosystem. Canadian Journal of Zoology 75:670-679.

Norment, C.J., S.A. Shackleton, D.J. Watt, P. Pyle, and M.A. Patten. 2016. Harris's Sparrow (Zonotrichia querula), The Birds of North America (P.G. Rodewald, Ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Web site: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/harspa [accessed October 2016].

Obst, J., pers. comm. 2015. Email correspondence to K.G.D. Burrell. September 2015. Field Technician, Daring Lake Natural Heritage Study, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.

Payette, S., M.J. Fortin, and I. Gamache. 2001. The subarctic forest-tundra: the structure of a biome in a changing climate. Bioscience 51:709-718.

Payne, R.B. 1979. Two apparent hybrid Zonotrichia sparrows. Auk 96:595-599.

Preston, T.M., and K. Kim. 2016. Land cover changes associated with recent energy development in the Williston Basin; Northern Great Plains, USA. Science of the Total Environment 566-567:1511-1518.

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification guide to North American birds: Columbidae to Ploceidae. Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, California.

Rees, W.R. 1973. Comparative ecology of three sympatric species of Zonotrichia. PhD Thesis. University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Rizzo, B. 1988. The sensitivity of Canada's ecosystems to climatic change. Canadian Community Ecological Land Classification Newsletter 17:10-12.

Robel, R.J., J.F. Keating, J.L. Zimmerman, K.C. Behnke, and K.E. Kemp. 1997. Consumption of coloured and flavored food morsels by Harris’s and American Tree Sparrows. Wilson Bulletin 109:218-225.

Rosenberg, K.V., J.A. Kennedy, R. Dettmers, R.P. Ford, D. Reynolds, J.D. Alexander, C.J. Beardmore, P.J. Blancher, R.E. Bogart, G.S. Butcher, A. F. Camfield, A. Couturier, D.W. Demarest, W.E. Easton, J.J. Giocomo, R.H. Keller, A.E. Mini, A.O. Panjabi, D.N. Pashley, T.D. Rich, J.M. Ruth, H. Stabins, J. Stanton, and T. Will. 2016. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan: 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States. Partners in Flight Science Committee.

R Core Team. 2015. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Web site: http://www.R-project.org/ [accessed December 2015].

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2014. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966-2013. Version 01. 30.2015. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland.

Sealy, S.G. 1967. Range extension of the Harris's Sparrow. Canadian Field-Naturalist 81:152-153.

Semple, J.B., and G.M. Sutton. 1932. Nesting of Harris's Sparrow Zonotrichia querula at Churchill, Manitoba. Auk 49:166-183.

Shuman, T.W., R.J. Robel, J.L. Zimmerman, and K.E. Kemp. 1992. Time budgets of confined Northern Cardinals and Harris's Sparrows in flocks of different size and composition. Journal of Field Ornithology 63:129-137.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. National Audubon Society, NY.

Smith, A.C. M.R. Hudson, C. Downes, and C.M. Francis. 2014. Estimating breeding bird survey trends and annual indices for Canada: how do the new hierarchical Bayesian estimates differ from previous estimates? Canadian Field-Naturalist 128:119-134.

Thompson, F.R., III. 1994. Temporal and spatial patterns of breeding brown-headed cowbirds in the midwestern United States. Auk 111:979-990.

Tomás, G., S. Merino, J. Martínez-de la Puente, J. Moreno, J. Morales, and E. Lobato. 2008. Determinants of abundance and effects of blood-sucking flying insects in the nest of a hole-nesting bird. Oecologia 156:305-312.

Wright, C.K., and M.C. Wimberly. 2013. Recent land use change in the Western Corn Belt threatens grasslands and wetlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110:4134-4139.

Zimmerling, J.R., A.C. Pomeroy, M.V. d’Entremont, and C.M. Francis. 2013. Canadian estimate of bird mortality due to collisions and direct habitat loss associated with wind turbine developments. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 8(2):10.

Zoltai, S.C. 1988. Ecoclimatic provinces of Canada and man-induced climatic change. Canadian Community Ecological Land Classification Newsletter 17:12-15.

Biographical summary of report writer(s)

Kenneth Burrell is a biologist with Natural Resource Solutions Inc. (NRSI), an environmental consulting firm, located in Waterloo, Ontario. At NRSI, Kenneth serves as the lead ornithological consultant and specializes in natural resource inventories and evaluations, research and impact studies. Kenneth is actively involved in the Ontario birding community, including eBird and the Ontario Field Ornitholgoists, serving on the Board of Directors since 2014 and the Ontario Bird Records Committee since 2011. Since completion of his MSc in 2013, Kenneth has published papers covering a range of topics in field ornithology, including spring reorientation flights in the Pelee region, hybrid warblers, eBird and its applications, and most recently on the assignment of stable isotopes in determining species origins.

Collections examined

No collections were examined.

Appendix 1. Threats assessment worksheet for Harris’s Sparrow.

Threats assessment worksheet

- Species or ecosystem scientific name:

- Harris's Sparrow

- Elcode

- ABPBXA405

- Date:

- 26/09/2016

- Assessor(s):

- Kenneth Burrell, Dave Fraser, Marcel Gahbauer, Suzanne Carrière, Richard Elliot, Pam Sinclair, Myles Lamont, Chris Norment, Rudolf Koes, Jim Rising, Samuel Hache, Amy Ganton, Joanna James

| Threat impact | Threat impact (descriptions) | Level 1 Threat impact counts: high range |

Level 1 Threat impact counts: low range |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Very high | 0 | 0 |

| B | High | 1 | 0 |

| C | Medium | 0 | 0 |

| D | Low | 3 | 4 |

| - | Calculated overall threat impact: | High | Medium |

- Assigned overall threat impact:

- BC = High - Medium

- Overall threat comments

- Several categories are unknown, and trend data are more limited than for some other birds. However, the range of medium-high is likely appropriate given the best available information.

| Threat | Threat | Impact (calculated) | Impact (calculated) | Scope (next 10 Yrs) | Severity (10 Yrs or 3 Gen.) | Timing | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Residential & commercial development | D | Low | Large (31-70%) | Slight (1-10%) | High (Continuing) | Overall low human population within the breeding grounds, not expected to affect the species. Within wintering range, development may be displacing suitable habitat, but largely limited to fringes of existing urban areas. Window kills may be the greatest concern with respect to this threat, but magnitude has not been documented for this species in particular. |

| 1.1 | Housing & urban areas | D | Low | Large (31-70%) | Slight (1-10%) | High (Continuing) | The focus for this threat is an increase in housing in the wintering range, with a specific focus on window kills and the effects of housing in urban areas. However, urban expansion within the wintering range is generally not rapid. While the species frequents backyard feeders and may therefore have some tolerance to suburban expansion, this also increases risk of window collisions. This may also be a risk along parts of the migratory route, although specific evidence is lacking. |

| 1.2 | Commercial & industrial areas | blank cell | Negligible | Negligible (<1%) | Unknown | High (Continuing) | blank cell |