COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) in Canada - 2014

List of Figures

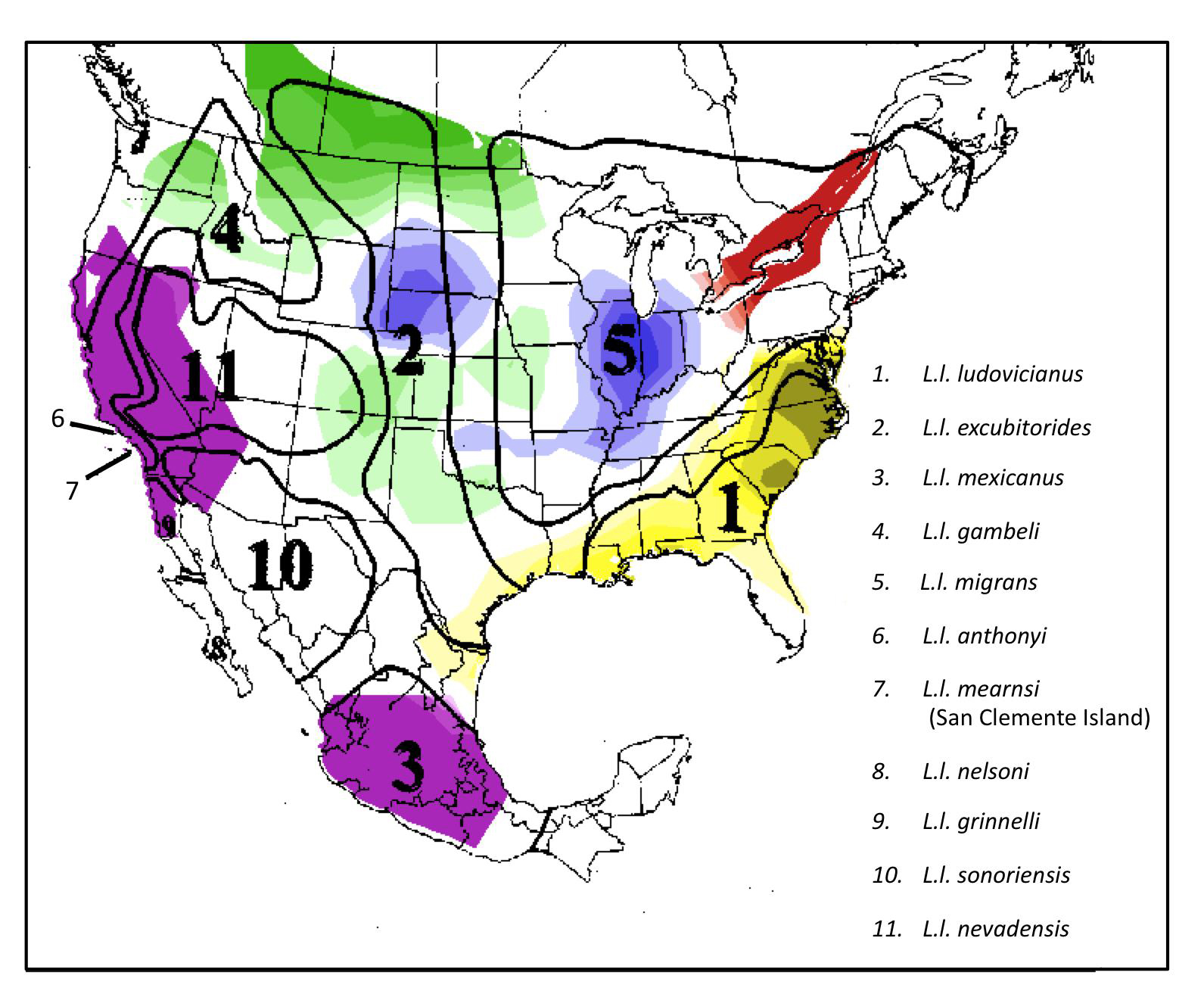

- Figure 1. North American breeding distribution of the different Loggerhead Shrike subspecies. The numbered areas outlined by black lines are based on morphometric differences as delineated by Miller (1931). These are compared to genetic clusters, as denoted by different colours, based on genetic admixture coefficients of birds sampled by Chabot (2011a). Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

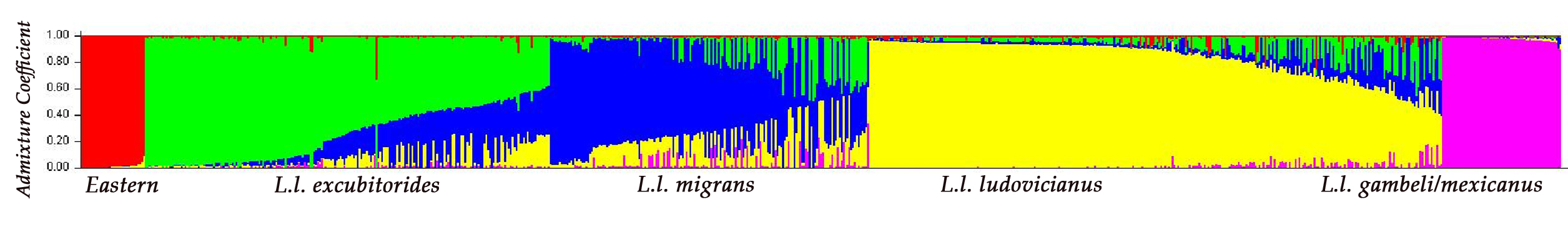

- Figure 2. Estimated genetic population structure in the Loggerhead Shrike in Chabot (2011a). Each individual is represented by a vertical line. Shown are k=5 clusters, each represented by a different colour. Within each, individuals are sorted by their admixture coefficients (Q). Genetic clusters are labeled below the figure with trinomial names corresponding to Miller (1931) and the additional Eastern Loggerhead Shrike genetic cluster. Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

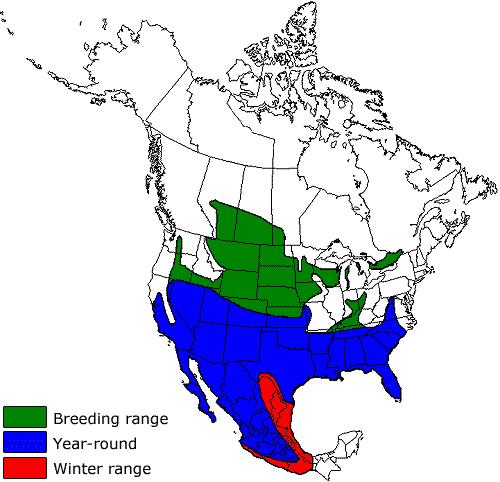

- Figure 3. North American distribution of Loggerhead Shrike in the breeding and wintering seasons, based on Yosef (1996). The Canadian range of the Prairie subspecies includes Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The Canadian range of the Eastern subspecies (southern Ontario and extreme southwestern Quebec) mostly lays within two core breeding areas.

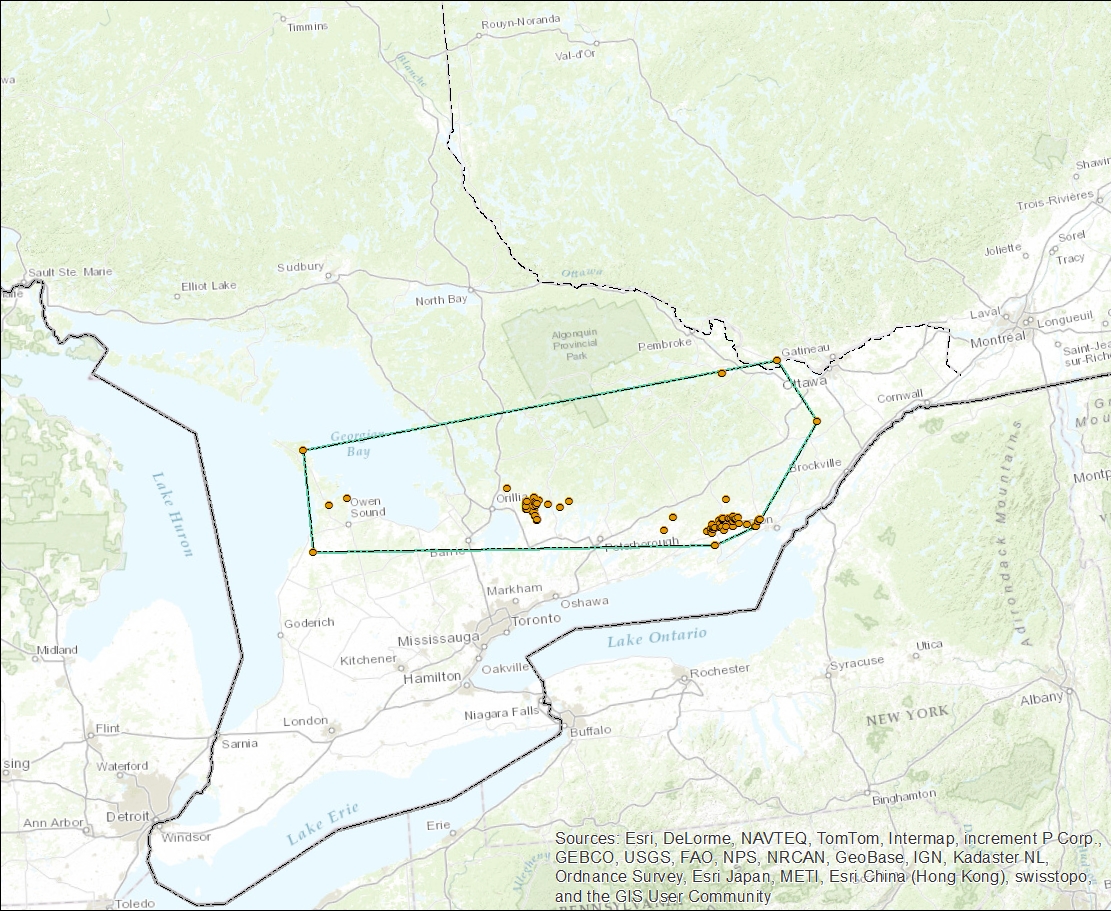

- Figure 4. Canadian breeding range of the Loggerhead Shrike Eastern subspecies, showing the polygon used to calculate Extent of Occurrence (map created by A. Filion).

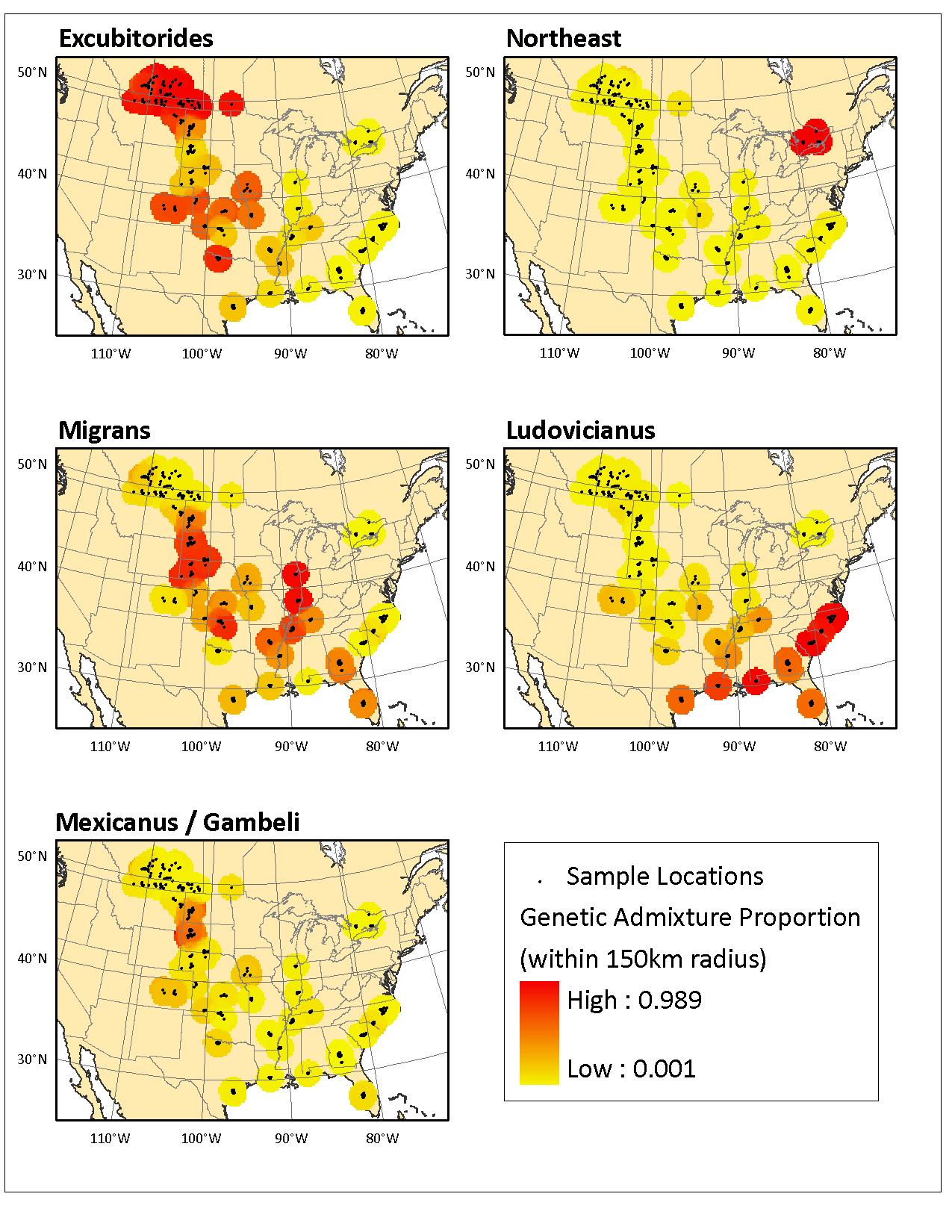

- Figure 5. Geospatial depiction of estimates of genetic relatedness for each genetic cluster for Loggerhead Shrikes sampled by Chabot (2011a). Darker areas indicate lower levels of gene flow among neighbouring sample areas. Lighter areas represent higher levels of gene flow among neighbouring sample areas. Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

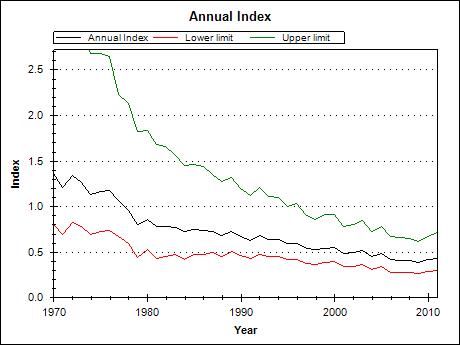

- Figure 6. Annual indices of population change for the Prairie subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike in Canada based on Breeding Bird Survey data, 1970-2011. Reproduced from Environment Canada (2013).

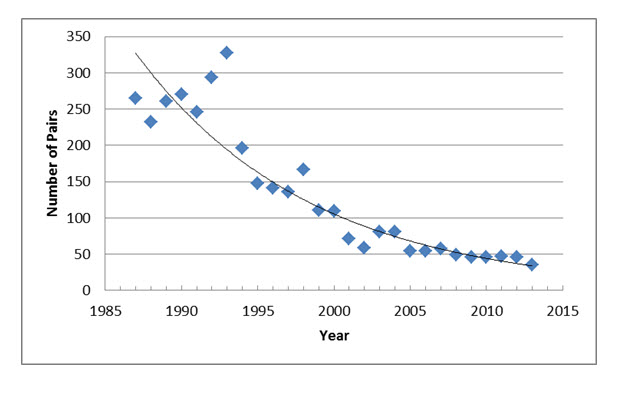

- Figure 7. Number of breeding pairs of Loggerhead Shrike in southwestern Manitoba from 1987 to 2013. The 2013 data point reflects reduced sampling effort, and is excluded from calculations of population trend. Data provided by K. DeSmet, Manitoba Conservation Department.

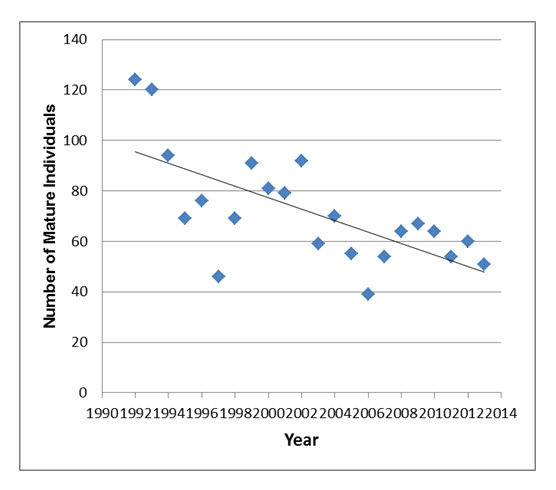

- Figure 8. Number of mature individuals of Loggerhead Shrikes tallied during the breeding season during targeted surveys conducted in Ontario from 1992 to 2013. Surveys include counts of paired birds and unmated adults. Results from the start year (1991) of the survey are underestimates and are not included. Data provided by Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region.

List of Tables

- Table 1. Pairwise estimates of population differentiation derived from nuclear genetic microsatellite data between L. l. excubitorides, L. l. ludovicianus, L. l. migrans and the new subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike in Ontario. PhiPT, an analogue of FST, above diagonal. Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant differences (P values below diagonal). N = 703 with 9999 permutations using routines in GENALEX (Peakall and Smouse 2006). Genetic variation among sub-groups was first measured using PhiPT, an analogue of FST, which calculates population differentiation based on the genotypic variance, where lower levels of gene flow among sub-groups will be indicated by higher values. See Chabot (2011a) for areas sampled.

- Table 2. Estimates of the number of Loggerhead Shrikes (mature individuals) from 1987 to 2013 based on 5-year Loggerhead Shrike surveys conducted in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and on annual surveys conducted in Manitoba.

- Table 3. Breeding Bird Survey trends for Loggerhead Shrikes over the long term and short term in the United States and Canada (Sauer et al. 2011; Environment Canada 2013). Trends are average annual percent change produced in a hierarchical model analysis. 95% confidence intervals represent the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles of the posterior distribution of trend estimates. Bold indicates statistically significant values.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Loggerhead Shrike Eastern subspecies Lanius ludovicianus ssp. and the Prairie subspecies Lanius ludovicianus excubitorides in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 51 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

COSEWIC. 2004. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Loggerhead Shrike excubitorides subspecies, Lanius ludovicianus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 24 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Loggerhead Shrike migrans subspecies, Lanius ludovicianus migrans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. viii + 13 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

James, R.D. 2000. Update COSEWIC status report on the Loggerhead Shrike migrans subspecies, Lanius ludovicianus migrans in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Loggerhead Shrike migrans subspecies, Lanius ludovicianus migrans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-13.

Cadman, M.D. 1991. Update COSEWIC status report on the Loggerhead Shrike (Eastern population) Lanius ludovicianus migrans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 26 pp.

Cadman, M.D. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Loggerhead Shrike Lanius ludovicianus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 100 pp.

COSEWIC acknowledges Amy Chabot for writing the status report on the Loggerhead Shrike (Eastern and Prairie subspecies), Lanius ludovicianus, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Jon McCracken, Co-chair of the Birds Specialist Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-953-3215

Fax: 819-994-3684

COSEWIC E-mail

COSEWIC web site

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Pie-grièche migratrice de la sous-espèce de l’Est (Lanius ludovicianus ssp.) et la sous-espèce des Prairies (Lanius ludovicianus excubitorides) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Loggerhead Shrike - Photo by Larry Kirtley (used with permission).

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014.

Catalogue No. CW69-14/390-2014E-PDF

ISBN 978-1-100-23939-2

Assessment Summary - May 2014

Assessment Summary - May 2014

The Loggerhead Shrike is a medium-sized songbird, about 21-23 cm in length. Males and females are similar in appearance. The top of the head, back and rump are dark grey; the underparts are white to greyish. The wings are largely black but a white wing patch is conspicuous in flight. The tail feathers are black, with some tipped with white. A black facial mask covers the eye and extends over the beak. The Loggerhead Shrike is notable for its raptor-like beak, and predatory and impaling behaviours. It may also be useful as a bio-indicator or ‘flagship’ species for grassland birds of high conservation concern.

The Loggerhead Shrike occurs only in North America. In western Canada, it occurs from southwestern Alberta, through southern Saskatchewan and into southern Manitoba. In eastern Canada, it is now found reliably in only two areas in southern Ontario, and occurs only sporadically in southwestern Québec. The species is a seasonal migrant. The wintering grounds of Canadian birds overlap with those of permanent residents in the U.S.

Two designatable units of Loggerhead Shrike occur in Canada: the ‘Prairie’ subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike (L. l. excubitorides) found in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, and the ‘Eastern’ subspecies found in Ontario and Québec. The latter was hitherto assigned as L. l. migrans, but new genetics information shows that it is actually a unique genetic group representing an as yet unnamed subspecies.

Loggerhead Shrike breeding habitat is characterized by open areas dominated by grasses and/or forbs, interspersed with scattered shrubs or trees and bare ground. Suitable habitat includes pasture, old fields, prairie, savannah, pinyon-juniper woodland, shrub-steppe and alvar. Winter and migration habitat are similar to breeding habitat requirements. Territory size ranges from 2.7 to 47.0 ha, and correlates with the abundance of trees and shrubs – increasing perch density will decrease territory size. Tree and shrub species that are relatively dense and extensively branched are preferred as nest sites.

Loggerhead Shrikes return to Canadian breeding areas as early as late March. Clutch size averages 5-6 eggs. Incubation lasts 16-18 days. Young fledge at 16-20 days after hatch. Site reuse is high but variable, with males more often returning to previously held territories than females. Adult fidelity is greater than natal fidelity. Site fidelity appears to be correlated with nesting success in the previous season.

The Loggerhead Shrike has experienced long-term persistent declines across its breeding range in North America and Canada. Numbering about 55,000 birds, the Prairie subspecies in Canada has been in a state of decline since at least 1970, with losses of about 47% occurring over the past 10 years. The Eastern subspecies has also experienced large declines in population size and breeding range. Fewer than 100 individuals now remain in Ontario, and fewer than 10 occur in Québec. It has been extirpated in New Brunswick since the 1970s.

Habitat loss and degradation on both the breeding and wintering grounds have been correlated with rangewide population declines of Loggerhead Shrike. Road mortality, pesticides, predation and weather extremes have been suggested as additional causes of decline. West Nile virus has also been implicated in the death of shrikes, but the severity of this threat is currently unknown.

The Loggerhead Shrike is protected in Canada, Mexico, and the USA by the Migratory Birds Convention Act. Under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the Prairie subspecies (L. l. excubitorides) is currently listed as Threatened, while the Eastern subspecies (formerly called L. l. migrans) is listed as Endangered. Recovery strategies have been drafted for both units. Provincially, the Loggerhead Shrike is listed as a Sensitive Species and a Species of Special Concern in Alberta. It is Endangered in Manitoba and Ontario, and Threatened in Québec. It is endangered, threatened or a species of special concern in 26 states.

The vast majority of suitable Loggerhead Shrike habitat is under private ownership and thus the adequacy of legal protection is potentially of concern.

Lanius ludovicianus excubitorides

Demographic Information

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Population | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 15,000 |

| Saskatchewan | 39,600 |

| Manitoba | 100-200 |

| Total | 54,700-54,800 |

Quantitative Analysis

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats)

- Loss and degradation of breeding, migration and wintering habitat.

- Pesticides

- Road mortality of adults and fledglings.

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

Status History

COSEWIC: Designated Special Concern in May 2014.

Status and Reasons for Designation:

Applicability of Criteria

Lanius ludovicianus ssp.

Demographic Information

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Population | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| Ontario | 50-100 |

| Québec | 10(maximum) |

| Total | 60-110 |

Quantitative Analysis

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats)

- Loss and degradation of breeding, migration and wintering habitat.

- Pesticides

- Predation leading to reduced nesting success.

- Road mortality of adults and fledglings.

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

Status History

The species was considered a single unit and designated Threatened in April 1986. Split according to subspecies (excubitorides and migrans) in April 1991, and each received separate designations. The migrans subspecies was de-activated in May 2014 in recognition of new genetic information indicating that some of the individuals in southeastern Manitoba should not have been included in the migrans subspecies. Further split into a new unnamed subspecies (Eastern subspecies, Lanius ludovicianus ssp.) in May 2014 and was designated Endangered.

Status and Reasons for Designation:

Applicability of Criteria

During the past decade, research efforts for the Loggerhead Shrike have largely focused on three main areas:

- documenting distribution and population trends;

- assessing population genetic structure; and

- gaining a better understanding of the wintering grounds of the species.

Work has also been done in eastern Canada to assess age structure, site fidelity and immigration rates, based on a long-term colour banding program. Analyses linking occurrence with habitat attributes have been undertaken in Ontario. In Québec, an extensive mapping project was undertaken to identify the most likely sustainable region for the species in the province.

Based on nuclear DNA microsatellites in a broad-scale sample of birds in North America, the Loggerhead Shrike in Ontario now apparently represents a previously undocumented unique genetic cluster, significantly different from L. l. migrans, which it was previously thought to be. Within Canada, there are two designatable units, which are genetically distinct and show limited gene flow. At one time, the subspecies L. l. excubitorides and L. l. migrans likely hybridized in southeastern Manitoba; any remaining birds in that part of the province are likely representative of the Prairie subspecies. It is now thought that the previous COSEWIC status assessment of L. l. migrans probably should not have included birds in southeastern Manitoba.

As part of recovery efforts, habitat stewardship projects, focused on collaboration with private landowners, are ongoing in both western and eastern Canada. In Ontario and Québec, a captive-breeding and release program has shown some limited success.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

The Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) is a medium-sized songbird, averaging about 20 to 22 cm in length and 47 to 48 g (Dunning 1993; Yosef 1996; Chabot unpubl. data). The top of the head, back and rump are dark grey; the underparts are white to greyish. The wings are largely black but the white base of the primary wing feathers shows as a white wing patch most conspicuous in flight. The tail feathers are largely black but some are tipped with white, with the extent of white increasing toward the edge of the tail. The Loggerhead Shrike has a black facial mask extending just above the eyes and continuing as a narrow black line over the base of the bill. This is a diagnostic feature, as the mask does not extend above the eye in the Northern Shrike (Lanius excubitor). The beak is black but can have a lighter hue, most notably on the lower mandible and mainly in females. The beak has a raptor-like hook and tomial tooth on each side (Cade 1995). The large jaw muscles needed to give the beak a powerful bite gives the species its large-headed appearance – hence the name ‘loggerhead’, which also means ‘blockheaded’.

Males and females are similar in appearance. Males tend to have a dark lower mandible during the breeding season and a whiter breast, whereas females often have a pale lower mandible during the breeding season and a tan hue to the breast. Males are generally larger than females (Haas 1987; Collister and Wicklum 1996; Yosef 1996; Chabot unpubl. data).

Juveniles look like adults but have faint barring on their breast prior to the first moult, which occurs in late summer or early fall (Burnside 2006). Juvenile wing and tail feathers are browner in colour than adults (Miller 1928; Burnside 2006; Chabot 2011a).

The spring song of males consists of short trills or a combination of clear notes repeated several times that vary in rhythm, pitch and quality. The territorial song, given by both males and females, is similar but contains more rough notes that resemble the begging calls of young. Males vocalize at a higher rate and longer than females, and demonstrate trill calls, which females do not (Soendjoto 1995). Shrikes give an alarm call that consists of harsh notes when an intruder or predator is seen.

Across the species’ range, Loggerhead Shrikes settle in loose territorial clusters or breeding aggregations (Cade and Woods 1997; Pruitt 2000; Etterson 2003). Woods (1994) reported ‘spatial clumping’ in the distribution of Loggerhead Shrikes nesting in sagebrush habitats. The spatial structure of breeding populations of Loggerhead Shrike has been widely described as ‘patchy’. Thus, in many areas, apparently suitable habitat will be unoccupied, while elsewhere similar habitat will be occupied by isolated groups. The result is that the species tends to exist in spatially isolated local breeding populations, which can be quite small in size.

The Loggerhead Shrike exhibits geographic variation in plumage colouration, including the amount of white in the tail, dorsal colouration, and amount of white in the rump, upper tail coverts and scapulars. Bill measures, tail length, and wing length also vary geographically (Chabot, unpubl. data). Miller (1931) undertook the most extensive taxonomic review of the species based on morphological characteristics, which he partitioned by age class and moult. He suggested 11 subspecies. Later work by Rand (1960) and Phillips and Rea (Phillips 1986) suggested fewer subspecies, but included a subspecies, L. l. miamensis, restricted to southern Florida.

In a study using a ~200 base pair segment of mitochondrial ‘Control region’ and ‘cytochrome b’ sequence, Mundy et al. (1997) found no unique haplotypes among populations of L. l. anthonyi, L. l. mearnsi, L. l. gambeli and L. l. excubitorides, although a different haplotype predominated in each subspecies. A G-test over all populations demonstrated a significant heterogeneity in haplotype frequencies among different sample sites and thus subspecies (Mundy et al. 1997). FST for all five populations was 0.78 (P < 0.05) and all intersubspecific pairs of populations were highly significant (P < 0.01). Recent work using 10 novel nuclear genetic microsatellite markers (Coxon et al. 2011) and a ~250 base pair segment of mtDNA (A. Coxon, pers. comm. 2012) supports the findings of Mundy et al. (1997).

Vallianatos et al. (2002) examined the genetic structure of central and eastern North American Loggerhead Shrike populations. A 267 base pair segment of mitochondrial control region sequence was examined from samples representing the range of three putative subspecies – L. l. migrans, L. l. ludovicianus, and L. l. excubitorides – and their intergrade zones. Results from Analysis of Molecular Variance showed that a significant amount of the total control region spatial variation was apportioned among the three subspecies (24.4%; P < 0.01). Four management units were proposed, which corresponded with the subspecies designations, but with a split in L. l. migrans, in which populations in Ontario, Québec, and the northeastern U.S. (i.e., an eastern management unit) were considered genetically distinct from those in Manitoba, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota and other western states within the putative western range of L. l. migrans (i.e., a L. l. migrans western management unit; Vallianatos et al. 2002).

Chabot (2011a) later undertook a broad-scale survey of the genetic spatial structure of Loggerhead Shrikes using assays of 15 microsatellite markers, including some of those used by both Mundy et al. (1997) and Coxon et al. (2011). Results again supported Miller’s (1931) designations of L. l. migrans, L. l. gambeli, L. l. excubitorides and L. l. ludovicianus, as well as Vallianatos et al.’s (2002) management units for L. l. migrans (Figure 1). However, these new results suggested that birds from Ontario (and Québec by inference) are actually genetically distinct from L. l. migrans (Figures 1 and 2). Morphometric data also generally supported the molecular findings (Chabot 2011a). Additional analyses of the microsatellite data were undertaken for the purposes of this updated status assessment, using traditional PhiPT statistics (an analogue of FST), in which populations were designated a priori, as required, based on the results of Bayesian clustering analysis (Chabot 2011a). Results suggest that the genetic clusters diagnosed by Chabot (2011a; Figures 1 and 2) are indeed genetically distinct (Table 1; P < 0.001).

Figure 1. North American breeding distribution of the different Loggerhead Shrike subspecies. The numbered areas outlined by black lines are based on morphometric differences as delineated by Miller (1931). These are compared to genetic clusters, as denoted by different colours, based on genetic admixture coefficients of birds sampled by Chabot (2011a). Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

Map: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 1

Map showing the North American breeding distribution of 11 different Loggerhead Shrike subspecies. The map also shows two other types of information: (1) areas where birds are morphometrically similar (based on features delineated by Miller 1931); and (2) areas where there are genetic clusters, based on genetic admixture coefficients of birds sampled by Chabot (2011a). Birds from Ontario (and Quebec by inference) are shown as genetically distinct from L. l. migrans.

Figure 2. Estimated genetic population structure in the Loggerhead Shrike in Chabot (2011a). Each individual is represented by a vertical line. Shown are k=5 clusters, each represented by a different colour. Within each, individuals are sorted by their admixture coefficients (Q). Genetic clusters are labelled below the figure with trinomial names corresponding to Miller (1931) and the additional Eastern Loggerhead Shrike genetic cluster. Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

Chart: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 2

Graph panel illustrating estimated genetic population structure in the Loggerhead Shrike as presented in Chabot (2011a), with admixture coefficient on the y axis and genetic clusters on the x axis. Each individual bird is represented by a vertical line. Shown are k=5 clusters, each represented by a different colour. Within each, individuals are sorted by their admixture coefficients (Q). Genetic clusters are labelled below the graph with trinomial names (L. l. excubitorides, L. l. migrans, L. l. ludovicianus, L. l. gambeli/mexicanus) corresponding to Miller (1931) and the additional Eastern Loggerhead Shrike genetic cluster.

| Genetic cluster | L. l. excubitorides | L. l. ludovicianus | L. l. migrans | Ontario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. l. excubitorides | - | 0.046 | 0.039 | 0.089 |

| L. l. ludovicianus | 0.001 | - | 0.047 | 0.124 |

| L. l. migrans | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | 0.121 |

| Ontario | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - |

Based on the results of Miller (1931), Vallianatos et al. (2002) and Chabot (2011a), two designatable units of Loggerhead Shrike are presently found in Canada. These are the Prairie Loggerhead Shrike (L. l. excubitorides) and an as yet unnamed subspecies found in southern Ontario and Québec. The latter unit was previously believed to be a subpopulation of L. l. migrans (Miller 1931), but it is now considered a remnant of a unique, and as yet unnamed, genetic group (Chabot 2011a). For the purposes of this report, the term “Eastern Loggerhead Shrike” will be used to specify this designatable unit, which is now considered distinct from L. l. migrans.

Vallianatos et al. (2002) recognized southcentral and southeastern Manitoba as an intergrade zone between L. l. excubitorides and L. l. migrans. While the results of Chabot (2011a) suggest that shrikes occurring in southeastern Manitoba in the last decade are identifiable genetically as L. l. excubitorides, this may be an artifact of the species’ recent extirpation from the northcentral United States (Pruitt 2000; Chabot, unpubl. data). While it is possible that southeastern Manitoba once supported a possible third designatable unit consisting of L. l. migrans, this cannot be demonstrated.

In addition to genetic and morphometric differences, the two designatable units identified above occur in distinct ecozones in Canada. The Prairie Loggerhead Shrike occurs primarily in the Prairies Ecozone, though its range formerly extended into the Boreal Plains to the north and to the west to the Montane Cordillera in Alberta (Cadman 1985, 1990). The Eastern Loggerhead Shrike occurs only in the Mixed Woods Plains. The large spatial separation between the current ranges of the two designatable units is sufficient to act as a barrier to movement, preventing genetic interchange.

The Loggerhead Shrike is the only species of Lanius endemic to North America (Lefranc 1997). Being both a passerine and a top-level predator, shrikes occupy a unique position in the food chain. The hooked bill and tomial ‘tooth’ of the shrike are functionally similar to the notched bill of falcons, allowing them to be predators of vertebrates, and set the species apart from other songbirds. Larger prey items are often impaled on sharp objects such as thorns or barbed wire. The impaling behaviour represents a unique adaptation to the problem of eating large prey items without having the stronger feet and talons of raptors. There is sometimes animosity toward the Loggerhead Shrike due to its habit of impaling prey, which is reflected in the species colloquial and Latin name of “butcher bird.”.

Research on habitat associations and requirements in Ontario (Cuddy and Leviton 1996; Glynn-Morris 2010; Chabot and Lagios 2012) suggest that the Loggerhead Shrike may be a suitable ‘flagship’ species, whereby protection of habitat for shrikes will benefit other grassland bird species that are also experiencing widespread declines (Berlanga et al. 2010). The North America Commission on Environmental Cooperation (CEC) has identified the Loggerhead Shrike as one of 11 bird species of common conservation concern in Canada, the United States and Mexico, which are considered as ‘flags of the continental vessel of conservation’ (CEC 2008).

The Loggerhead Shrike is extirpated from the majority of its former range in eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. The Ontario population is the largest and potentially only remaining representative of the Eastern Designatable Unit (Chabot 2011a) and therefore, has a special significance in regard to conservation of genetic diversity within the species.

Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge is not currently available for this species.

The Loggerhead Shrike occurs only in North America. Within this area, it has a wide breeding range across most of Mexico, the United States and southern Canada (Figure 3), although it is unclear whether the species is found on the Gulf Coast region in Mexico during the breeding season (G. Perez pers. comm. 2006). In the northern portions of the range, the species is an obligate migrant. Farther south, generally south of 40° latitude and outside Canada, the species is either a facultative migrant or exhibits some degree of annual residency (Figure 3). The wintering grounds of migrants overlap with those of permanent residents.

Figure 3. North American distribution of Loggerhead Shrike in the breeding and wintering seasons, based on Yosef (1996). The Canadian range of the Prairie subspecies includes Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The Canadian range of the Eastern subspecies (southern Ontario and extreme southwestern Quebec) mostly lies within two core breeding areas.

Map: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 3

Map showing the global range of the Loggerhead Shrike in North America, where it occurs across most of Mexico and the United States and in southern Canada. Breeding range, year-round range, and winter range are distinguished. The Canadian range of the Prairie subspecies (L. l. excubitorides) includes Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. The Canadian range of the Eastern subspecies (L. ludovicianus spp.) covers southern Ontario and extreme southwestern Quebec.

Exact range limits of subspecies cannot be clearly defined as hybridization occurs in contact zones among the various subspecies. Prior to the species decline, which has since limited the species’ occurrence in some previous contact zones, L. l. excubitorides populations intergraded with the putative subspecies L. l. gambeli and L. l. nevadensis in the Rocky Mountain region, with L. l. mexicanus in northern Mexico (Miller 1931; Chabot 2011a) and with L. l. migrans in the Great Plains and Manitoba (Vallianatos et al. 2001; Chabot 2011a).

The breeding range of the Prairie subspecies, L. l. excubitorides, extends from southeastern Alberta through southwestern Manitoba, south through the Great Plains to central Texas and west from northeastern Idaho south to southeastern California, west Texas and into Sonora and northern Durango in Mexico (Figure 1).

It is likely that L. l. migrans formerly bred from southeastern Manitoba south to eastern Texas, central Louisiana, and western North Carolina and Virginia. Its range was believed to extend eastward to the Maritime provinces, but it is likely that northeastern populations were more genetically similar to shrikes in Ontario, herein considered to be the Eastern Designatable Unit. Currently, isolated populations of ‘true’ L. l. migrans now occur only in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Iowa and southward (Figure 1).

Due to mixing of subspecies on the wintering range and weak migratory connectivity (Chabot 2011a), locational matching of discrete breeding and wintering populations is difficult to understand. However, it would appear that populations in western Canada migrate in a southeastern direction, while individuals in eastern Canada migrate to the south, migrating east of the Adirondack Mountains to the Atlantic Coast, or to the southwest (Burnside 1987; Hobson and Wassenaar 1997; Perez 2006; Perez and Hobson 2007; Chabot 2011a).

In Canada, the Prairie Subspecies of the Loggerhead Shrike (L. l. excubitorides) occurs in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba (Figure 3). In Alberta, it was historically found throughout the Central Aspen Parkland (Kiliaan and Prescott 2002) and Prairie regions (Salt and Wilk 1958). It once occurred north to the Peace River region, but disappeared in the 1950s (Salt and Wilk 1958; Prescott and Bjorge 1999). Currently, the core of its range in Alberta is the northern half of the province’s grasslands eastward from Hanna and Brooks (Bjorge and Kiliaan 1997) to the southern Aspen Parkland region east of Stettler (Kiliaan and Prescott 2002; Prescott 2013). Since 1993, populations have declined and the breeding range has retracted (Prescott 2009, 2013).

The trend in Saskatchewan mirrors that of Alberta, with population declines being registered (see Fluctuations and Trends), together with a retraction of the species’ breeding range southward (A. Didiuk, pers. comm. 2012). The species is currently widely distributed in Parkland and Grassland areas, but it no longer breeds in most areas of central Saskatchewan (Meadow Lake, Nipawin, Somme areas; Smith 1996). Populations are patchily distributed within southern Saskatchewan, with the loss of many local populations in southeastern Saskatchewan in the past 10 years (A. Didiuk, pers. comm. 2012).

Historically, L. l. excubitorides overlapped and intergraded with L. l. migrans somewhere in eastern Manitoba (Miller 1931; Vallianatos et al. 2001). Loggerhead Shrikes currently only occur reliably in the southwestern portion of the province, which consists of the L. l. excubitorides subspecies. Targeted annual surveys focused on previous breeding sites over the past 10 years indicate that the species’ range has been retracting south and westward (K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2012). The species is now largely absent as a breeder in southeastern Manitoba.

The Loggerhead Shrike was historically a sporadic breeding bird in the Maritimes; no breeding activity has been reported there since 1972 (Erskine 1992). The Eastern subspecies is now confined to southern Ontario and extreme southwestern Québec (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Canadian breeding range of the Loggerhead Shrike Eastern subspecies, showing the polygon used to calculate extent of occurrence (map created by A. Filion).

Map: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 4

Map of the Great Lakes region indicating the Canadian breeding range of the Eastern subspecies of the Loggerhead Shrike (L. ludovicianus spp.) in Ontario and extreme southwestern Quebec (see text for details). The range is estimated using a minimum convex polygon containing sites where the subspecies has been observed.

In Ontario, from 1981 to 1985, during the first Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas, Loggerhead Shrikes were reported in 145 10 km x 10 km squares (Cadman et al. 1987). Several of the squares were estimated to have held between 2 and 10 pairs. Results from the late 1980s, collected by the Ontario Rare Breeding Bird Program and the subsequent Ontario Birds at Risk Program, indicated that shrikes had largely disappeared from the province, being found mainly in three core breeding areas associated with limestone plains in areas around Carden, Napanee and Smiths Falls. During the second Breeding Bird Atlas (2001-05), shrikes were recorded in only 38 10 km x 10 km squares (Cadman et al. 2007). The species is now found only sporadically in the Smiths Falls area and has declined to fewer than 10 breeding pairs annually in the Napanee area (Imlay and Lapierre 2012). While not a large population (20 pairs at most), the species is still found reliably in the Carden limestone plain area (Imlay and Lapierre 2012).

The Loggerhead Shrike went from being a fairly common breeding species in Québec in the early part of the 1900s, to rare by the late 1970s. During the first breeding bird atlas in Québec between 1984 and 1989, the species was recorded in 30 10 km x 10 km squares in the southwestern part of the province. In the second atlas currently underway, it has been found at only 1 site. Prior to that, two pairs were reported breeding in 1992 and one in 1993 (Grenier et al. 1999). In 1995, breeding evidence was found in three locations – one close to Montréal and two in the Outaouais region in southwestern Québec (SOS-POP 2011; F. Shaffer, pers. comm. 2014). No other evidence of breeding was found between 1996 and 2009, despite surveys at former breeding sites and despite releases of 101 captive bred young in the Outaouais region from 2004 to 2009 (F. Shaffer, pers. comm. 2012). One captive-bred bird released in Québec in 2008 was subsequently located breeding in the Carden area of Ontario in 2009. In 2010, one breeding pair (including a bird that had been released in Ontario) was found nesting in the Outaouais region.

Extent of occurrence (EO) for the Prairie subspecies, based on the minimum convex polygon method, is estimated to be 375,100 km2. An index of area of occupancy (IAO), based on the 2 x 2 km square grid-method, for this population is not possible to calculate at this time owing to lack of information on specific localities. However, the population size and the scattered breeding sites across a large area would yield an IAO that is >2000 km2.

EO for the Eastern subspecies, based on the minimum convex polygon method, is estimated to be 49,310 km2. IAO, based on the 2 x 2 km square grid-method, is estimated to be < 200 km2, assuming that the maximum population size consists of 55 pairs and that not every pair occurs in a separate 2 x 2 km grid cell, which is true.

Search effort and methodology for surveying Loggerhead Shrike varies by province. On a North American scale, the species is monitored by the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), which provides the only standardized measure of population trends across large geographic regions (see Robbins et al. 1986; Peterjohn and Sauer 1995). However, the accuracy of the BBS for estimating abundance for Loggerhead Shrike is questionable (Smith 1990; Peterjohn and Sauer 1995). The species’ propensity for ‘spatial patchiness’ (Etterson 2003; Chabot, unpubl. data; CWS .unpubl. data) and low population density confound efforts to estimate population statistics using the BBS methodology.

A variety of surveys have been conducted for the Loggerhead Shrike in Alberta over the years (Telfer et al. 1989; Bjorge and Prescott 1996; Collins 1996; Bjorge and Kiliaan 1997; Kiliaan and Prescott 2002; Prescott 2003, 2004). The most useful survey for monitoring large-scale population trends in western Canada has been the roadside survey conducted at 5-year intervals since 1987 in Alberta and Saskatchewan. These surveys have covered thousands of kilometres of roadside habitat annually. The most recent such surveys were conducted in 2013 (Prescott 2013; Didiuk et al. 2014). Because the first year of the survey (1987) resulted in erroneously low estimates (Prescott 2013), this year should not be included for the purposes of calculating population trends in Alberta or Saskatchewan. In addition, the 5-year Loggerhead Shrike survey was not carried out in Alberta in 1993, but it was in Saskatchewan. Hence, comparable results for Saskatchewan and Alberta are available only from 1998 to 2013.

Unlike the two other Prairie provinces, which have had 5-year surveys, targeted surveys have been undertaken in southwestern Manitoba annually by Manitoba Conservation since 1987 as part of a large-scale grassland bird monitoring project (K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2014). Methodology changed in the early 1990s, but in general it has been standardized, being focused on assessing occupancy at recent and historically occupied breeding sites (K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2012). Loggerhead Shrike occurrence is also being documented in Manitoba’s current breeding bird atlas project, which extends from 2010 through 2014. The current breeding bird atlassing efforts detracted from targeted shrike surveys in 2013 (K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2014), so this year was excluded from population trend estimates calculated in this report.

The second Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas was undertaken from 2001 to 2005, providing both a province-wide survey for the species and the means to compare occurrence probability in the 20 years since the first atlas was conducted in 1981 to 1985 (Cadman et al. 2007). In Ontario, the Canadian Wildlife Service has also supported the conduct of targeted surveys annually over the last 20 years in most of the core breeding areas (Imlay and Lapierre 2012). Targeted survey work has been more limited in the Smiths Falls area, Grey-Bruce counties and on Manitoulin Island. Survey methodology has been standardized during the last 10 years and focuses on recent and historically occupied sites (Imlay and Lapierre 2012). Areas of suitable habitat have been mapped and are surveyed to the degree possible in each core breeding area in addition to surveys of historically used sites.

The Canadian Wildlife Service mapped suitable habitat in Québec in the late 1990s. This analysis showed that the greatest extent of habitat remained in the Outaouais region, adjacent to the Pembroke and Renfrew areas of eastern Ontario, which are still periodically occupied by shrikes (Jobin et al. 2005). Surveys in the Outaouais region were undertaken from 2004 to 2010. No directed surveys have been conducted for the species since then. The province’s second breeding bird atlas effort was initiated in 2010. In that year, one pair was found (Chabot 2011b), and a single bird was seen at the same location again in 2011 (F. Shaffer, pers. comm. 2012).

Loggerhead Shrikes are associated with a variety of grassland and shrubland habitats. Breeding territories typically include the following habitat features:

- nesting substrate (small trees or shrubs);

- elevated perches for hunting, pair maintenance and territory advertisement (fence posts, shrubs and trees, utility wires);

- food cache sites (thorny shrubs, barbed wire or finely branched trees); and

- foraging areas, generally in the form of open short grass areas with scattered perches and some bare ground.

These habitat features can be met in a wide variety of habitats. Thus, shrikes occupy habitats that include pastures (both cultivated and native grassland), old fields, prairie, savannah, pinyon-juniper woodland, shrub-steppe, and alvar (Brownell and Riley 2000; Pruitt 2000; Prescott 2013).

In many areas, specific micro-habitat features have shifted over time. For example, there has been a transition from hawthorn (Cratageus sp.) to Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana)-dominated habitat in the Napanee plain in Ontario. Additionally, in some regions Loggerhead Shrikes are now found in habitats that have been created by human activities such as airports and cemeteries (Temple 1995; K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2012; Chabot, unpubl. data).

While hedgerows are frequently used for nesting, especially in areas where other habitat types are limited, nests along treed or shrubby fence lines and in hedgerows have low reproductive success due to increased susceptibility to predation that occurs along mammalian travel corridors (Yosef 1994; Esley and Bollinger 2001).

Mean territory sizes of L. l. excubitorides in two studies in Alberta ranged from 8.5 ha to 13.4 ha (Collister 1994; Collister and Wilson 2007a). In Ontario, territory size ranged from 2.7 to 47.0 ha in Carden and 2.9 to 11.7 ha in Napanee in 2009 (Glynn-Morris 2010). No statistically significant difference was found in territory size between Carden (mean 15.45 ± 12.99 ha, n=12) and Napanee (mean 6.86 ± 3.52 ha, n=6). Territory size was significantly larger during the fledgling stage (12.97 ± 13.90 ha) than in all other reproductive stages (1.55 ± 1.43 ha to 3.33 ± 2.49 ha) and appeared to be independent of habitat patch size.

In other areas of North America, territory size ranges from 0.8 to 17.6 ha (reviewed in Yosef 1996 and Pruitt 2000). Territory size has been shown to correlate with the abundance of trees and shrubs – increasing perch density will decrease territory size (Miller 1951; Yosef 1996), which may account for differences in average territory size among areas. Further, territory size appears to vary over the course of the reproductive season, increasing to a maximum size after young have fledged but are still dependent upon their parents (Glynn-Morris 2010).

Small trees and shrubs are used as nest sites (Peck and James 1987; Yosef 1996; Pruitt 2000; Chabot et al. 2001a). A variety of species are used across the species’ range and local preferences are apparent. Species that are relatively dense, and thus likely protective, are preferred (Porter et al. 1975; Chabot et al. 2001b; Glynn-Morris 2010). Overall, shrikes choose the local tree or shrub species that best meet these conditions. The Prairie subspecies nests in Caragena shelter belts and in other shrubs, like choke cherry (Prunus virginiana), willow and Thorny Buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea; Collister and Wilson 2007a; A. Didiuk pers. comm. 2014). In Ontario, hawthorn (Cratageus sp.) is preferred (Peck and James 1987), though Red Cedar, which has displaced hawthorn in some regions, is now the most common nest tree species (Chabot et al. 2001a).

The suitability of shorter versus taller herbaceous vegetation height as preferred foraging substrate is in debate. It is possible that it varies across the species’ range and/or is correlated with other factors that influence habitat selection. In the eastern United States and Ontario, shrikes appear to prefer areas with relatively short grass, in which they may have greater foraging success (Gawlik and Bildstein 1993; Chabot et al. 2001b; Glynn-Morris 2010) or where they can forage with more energetic efficiency (Yosef and Grubb 1993). In western Canada, Prescott and Collister (1993) found that shrikes breeding in Alberta preferred arid-land with medium (15-35 cm) and tall (> 35 cm) grasses. The structure of the herbaceous vegetation (i.e., homogenous or heterogenous) is important, with heterogenous herbaceous ground cover, interspersed with bare ground, being preferred (Michaels and Cully 1998). Historically, grazing or fire likely helped to maintain the open habitat preferred by the species and promoted a heterogeneous structure (Cuddy 1995).

In many areas, occurrence of shrikes correlates with the proportion of suitable habitat in the landscape (Brooks and Temple 1990a; Bjorge and Prescott 1996; Cuddy and Leviton 1996; Yosef 1996; Chabot et al. 2001a; Glynn-Morris 2010), with home ranges or territories usually being only a proportion of a suitable habitat patch (Glynn-Morris 2010), which may facilitate the loosely colonial nature of the species. Cuddy and Leviton (1996) suggested that a threshold level of suitable habitat may be required at the landscape level before the species occupies a particular area.

Bjorge and Prescott (1996) found that the density of breeding shrikes in southeastern Alberta was positively correlated with the density of trees/shrubs, farmyards, shelterbelts and rights-of-way. The core breeding areas in Ontario are associated with limestone plains where cattle grazing on unimproved pasture accounts for the majority of the land use.

A landscape-level analysis of habitat patch attributes within each core area was undertaken for the Carden, Napanee and Smiths Falls regions of Ontario using shrike occurrence data from 1991 to 2010 (Chabot and Lagois 2012). Analyses assessed attributes within 0.5, 5 and 15 km radius of sites, which corresponds generally with territory size and average dispersal distance of returning breeders and young, respectively. Analysis of patch, class and landscape metrics revealed statistically significant differences among most metrics between occupied and suitable but unoccupied habitat, and occupied and randomly chosen habitat patches (Chabot and Lagois 2012), suggesting that landscape level effects are important elements of habitat suitability.

Generally, winter habitat requirements do not appear to differ markedly from breeding habitat requirements (Bartgis 1992; Collins 1996; Yosef 1996; Chabot, unpubl. data). In the southern portion of the North American range, territories can be occupied year-round by the same individuals (Miller 1931; Chabot unpubl. data), but there may be changes in habitat use within the territory. For example, territory size can increase during winter (Blumton 1989; Collins 1996) and some habitat types, such as forested areas, can be used more frequently in winter than during breeding (Blumton 1989; Bartgis 1992; Gawlik and Bildstein 1993; Chabot unpubl. data).

Due to difficulty distinguishing among subspecies in the field, little is known about competition between migratory and resident individuals on the wintering grounds. It has been suggested that residents can out-compete migrants during the winter, forcing them into sub-optimal habitat. However, Perez and Hobson (2009) found that migrant and permanent resident shrikes partitioned habitat in Mexico. On the Gulf Coast of Texas, habitat also appears to be partitioned among age classes, with older birds occupying coastal habitat and younger birds occupying inland (Craig and Chabot 2012).

Little is known about habitat requirements of the species during migration (Yosef 1996). However, given that broad breeding and wintering habitat requirements are similar, it is likely that migration habitat requirements are similar too (Yosef 1996).

Breeding habitat has declined and continues to decline throughout the species’ range (e.g., Telfer 1992; Yosef 1996; Cade and Woods 1997). However, there is also a general consensus that much apparently suitable habitat is not occupied (Brooks and Temple 1990a; K. DeSmet pers. comm. 2012; A. Didiuk; pers. comm. 2012; A. Chabot, pers. obs.; CWS unpubl. data). While Prescott and Collister (1993) tentatively concluded that the population of Loggerhead Shrike in Alberta was limited by the availability of high-quality habitat, they did not discount the possibility that the population was limited by other factors as well. In Ontario, a habitat supply analysis indicated that there was enough habitat to support 500 pairs (Cuddy and Leviton 1996), whereas fewer than 50 pairs were known in the province at that time. A similar analysis in Québec suggested that the Outaouais region should have habitat adequate to support a viable population (Jobin et al. 2005), which also is clearly not being realized. To date, the majority of habitat availability studies have not addressed the impact of fragmentation or other landscape-level effects on habitat suitability.

In western Canada, loss of breeding habitat appears to occur primarily through conversion of grasslands to agricultural crops, and as a result of grassland areas along the northern periphery of the breeding range reverting to forest (Cadman 1985). In the Canadian Prairies ‘unimproved’ pasturage declined 39% between 1946 and 1986 in areas where the largest shrike population declines were noted, but only 12% where substantial numbers of birds persisted (Telfer 1992). While extensive areas of pasture still occur in Manitoba, much of it is ‘improved’ and thus lacking nest trees and perches.

In recent decades, the primary loss of habitat in eastern Canada has resulted from natural succession stemming from the abandonment of pastureland (Cadman et al. 2007). Pastureland in Ontario dropped from about 2.7 million hectares in 1921 to about 660,000 hectares in 2011 – a 75% decline. These declines are continuing (e.g., a 12.3% decline from 2006 to 2011). In the Smiths Falls area, succession has often been linked to rural residential development, but habitat has also been lost to reforestation projects (D. Cuddy, pers. comm. 2012). Aggregate extraction has had a local impact in Ontario, in particular in the Carden area (Cadman 1990). Solar farm development is becoming an increasing issue in the Napanee and Carden areas.

Prior to European settlement in eastern North America, grassland birds, including Loggerhead Shrike, nested in native grasslands, composed of prairies, savannahs, beaver meadows, burned areas, areas cleared for agriculture by First Nations, and alvars (Askins et al. 2007; Catling 2008). Most such habitat was destroyed following European settlement (Askins et al. 2007). Only 2.4% of northern tallgrass prairie remains in North America (Samson et al. 2004) and less than 1% remains in Ontario (Bakowsky and Riley 1994; Catling and Brownell 1999; Catling 2008). In Ontario, while the exact amount of loss of alvar grasslands and savannahs is hard to estimate, a significant portion has been lost and much of the remaining area degraded through modification by agriculture and other human uses (Reschke et al. 1999; Brownell and Riley 2000).

In Québec, there was an 85% decline in pasture between 1941 and 1990 (Cadman 1990). Aerial photographs taken from the 1960s and 1980s in southern Québec were interpreted to evaluate changes in the rural landscape of the St. Lawrence Lowland (Jobin et al. 1996). Changes in the rural landscape were caused mainly by abandonment of marginally productive farms and subsequent forest regeneration, plantations, urban sprawl and an increase in intensive farming. In a more recent study, Jobin et al. (2010) examined Landsat images covering the St. Lawrence Lowland and Appalachian ecoregions of southern Québec for the years 1993 and 2001. A shift in major agricultural classes was noted in the St. Lawrence Lowlands, where perennial forage crops had been converted to annual crops and landscapes dominated by intensive agriculture expanded (Jobin et al. 2010), indicating a likely loss of suitable breeding habitat for the Loggerhead Shrike.

In the northern United States, habitat loss has also been implicated as a cause of population decline. For example, 70% of sage-steppe habitat has been converted to agriculture in Idaho; strip mining has destroyed much habitat in Indiana; and farmland declined from 74% to 30% in New York between 1900 and 1982 due to abandonment and forest succession (Yosef 1996).

Migration and wintering habitat has declined (Telfer 1992; Yosef 1996; Cade and Woods 1997). Given the pervasive loss of grassland habitat throughout North America, it is likely that habitat loss has had a significant negative impact on both eastern and western Canadian Loggerhead Shrike populations on their wintering grounds.

Loggerhead Shrikes start to arrive on their northern breeding grounds in late March or early April and migrate south by September, thus spending only about 5 months of the year in Canada.

Most studies report that the species is monogamous (Yosef 1996). However, evidence from nuclear DNA analysis of clutches in Ontario indicate a low occurrence of both extra-pair copulation and, more frequently, multiple maternity (e.g., brood parasitism/egg dumping) within individual nests (Chabot and Lougheed 2005). Banding work also supports the finding of multiple females at a nest site and of ‘helper’ birds of either sex at nests in Ontario (Chabot 2009, 2010, 2011b). Still, Etterson (2004) found only 4% of offspring or 14% of families had young sired by extra-pair fertilizations in Oklahoma and no cases of multiple maternity. Nonetheless, polygyny (i.e., the practice of a male having two or more mates) has been reported (Yosef 1992).

Loggerhead Shrikes generally breed as 1-year olds in the first spring after hatching (Miller 1931). The species is usually single-brooded but is considered to be a persistent renester after a failed nesting attempt (Miller 1931; Yosef 1996). Although double brooding occurs occasionally in northern latitudes, it is most common in the south (Yosef 1996).

Both sexes are involved in choosing the nest site and nest building (A. Chabot, pers. obs.). The nest is an open cup, made with small twigs and usually lined with feathers or fur. Clutch size increases with latitude and tends to be larger in western populations (Yosef 1996). It averages 5 to 6 eggs (Yosef 1996; Chabot et al. 2001a; Collister and Wilson 2007b). The incubation period lasts 15 to 17 days (Lohrer 1974; Collister and Wilson 2007b). The nestling period lasts from 16 to 20 days (Yosef 1996; Collister and Wilson 2007b). Both parents continue to feed the young for up to a month post-fledging, but they often move to different areas of the territory, with each parent caring for part of the brood. Young begin to show impaling behaviour at 20 to 25 days of age and can successfully impale by day 35 (Smith 1972).

Nest success is highly variable from year to year and among areas (Pruitt 2000). Average nesting success (nests in which ≥1 young fledge) was 56% among studies (reviewed in Yosef 1996), but more recent studies show even lower estimates. For example, in southeastern Alberta, Collister and Wilson (2007b) reported average daily survival of Loggerhead Shrike nests to be 0.973 (95% CI: 0.967, 0.978), which when raised to the length of the nest cycle gives a nest success estimate of 35% (95% CI: 28 – 43%; S. Wilson, pers. comm. 2014). Other estimates using analysis methods based on exposure days include 40% in Oregon (Nur et al. 2004), 43% in Oklahoma (Etterson et al. 2007) and as low as 26% in Illinois (Walk et al. 2006).

Brood parasitism by cowbirds is rare (DeGues and Best 1991). However, nest predation can significantly decrease productivity, for example in Manitoba (K. DeSmet, pers. comm. 2012), Ontario (CWS unpubl. data) and Illinois (e.g., Walk et al. 2006), all of which support small populations of shrikes.

Juvenile mortality following fledging is apparently high, with 33-46% mortality in the first 7-10 days after fledging, most often attributed to predation (Yosef 1996; Chabot et al. 2001a). However, some other studies (e.g., Blumton 1989) have shown relatively high fledgling survival. In Ontario, results from a radio-telemetry study of older fledglings that had survived to reach independence indicated a fairly high survival rate to fall migration (Imlay et al. 2010).

The longevity record for a wild Loggerhead Shrike is 12 years, and captive birds can live up to 15 years (T. Imlay, pers. comm. 2012). More commonly, based on banding data from Ontario, it would appear that the average age of Loggerhead Shrike in the wild is 2 to 4 years. Based on estimating α + [S/(1-S)], where α is the typical age at first breeding for females and S is adult survival, an estimated range of adult survival from 0.5 to 0.7 would yield a generation time ranging from 2 to 3.3 years. As such, a generation time of 3 years is used in this assessment.

Age structure data have not been collected recently from shrikes in the Prairies, but have been recorded as part of the banding work in Ontario and Illinois (Chabot 2009, 2010, 2011b). In Ontario, the majority of breeders are After Second Year (ASY) birds that are at least 2 years old. While the ratio of Second Year (SY) to ASY birds varies significantly year to year, in general more SY females than males are found annually both in Illinois and Ontario. As reproductive success is similar among regions (Chabot 2011b), over-wintering mortality of first-year birds is likely a key factor influencing age structure.

The Loggerhead Shrike is an opportunistic forager, adjusting to exploit the available prey base (Miller 1931; Craig 1978; Scott and Morrison 1995). Although it feeds primarily on insects during the breeding season, vertebrates make up an increasing proportion of the diet during winter. The species’ behaviour of caching food is believed to be used as a food storage system and may help to improve nesting success, especially during inclement weather (Yosef 1996). However, brood reduction has been observed in harsh weather and is likely related to food supplies (A. Chabot, pers. obs; K, DeSmet, pers. comm. 2012).

Although Loggerhead Shrikes are fairly tolerant of human activity around the nest site (Luukkonen 1987; Brooks 1988; Bartgis 1989), there is conflicting evidence as to how frequently they desert the nest in response to human disturbance (Porter et al. 1975; Siegel 1980). Shrikes appear less disturbed by mechanical disturbance, such as that caused by tractors, than by human presence (A. Chabot pers. obs.).

Shrikes nesting in eastern Manitoba in the early 1990s were often associated with anthropogenic habitat (e.g., cemeteries, airports, rural residential housing.), and the species can be found nesting in similar habitat in other parts of its range (Chabot, unpubl. data). While this suggests that the species can successfully ‘transition’ to these habitat types, it does not appear to be true range-wide (Jones and Bock 2002). Only one study has assessed reproductive success in urban habitats (Boal et al. 2003). Results suggest that while reproductive success is similar between urban and rural habitats, breeding territories had lower proportions of residential and commercial development and greater proportions of open areas with low-growing vegetation than randomly available (Boal et al. 2003). Further, the use of urban habitat may be associated with a concurrent loss of natural habitat (Boal et al. 2003). Therefore, it is unknown if the species’ ability to adapt to habitat change and loss actually contributes to long-term viability.

The Loggerhead Shrike is migratory in the northern half of its breeding range, which includes all of its Canadian range. Farther south, as described by Miller (1931), migration is an “irregular and variable habit” in the species. Even in primarily migratory populations, some individuals in the United States overwinter on their breeding grounds (Figure 3).

Results of spatial autocorrelation analysis of genetic versus geographic distance among individuals suggest that gene flow (a result of successful dispersal that leads to reproduction) occurs at great distances. Positive spatial genetic structure (i.e., genetic similarity among individuals) occurs up to 500 km in the species (Chabot 2011a). Results of spatial autocorrelation suggest a pattern of Isolation By Distance (Wright 1943), in which gene flow (i.e., dispersal) is greater over shorter distance and decreases with increasing distance (Figure 5). Females and young prior to their first breeding season disperse farther than males and ASY breeders (Chabot 2011a). Migratory individuals of all cohorts disperse significantly farther than their non-migratory resident conspecifics. Gene flow estimates indicate that dispersal occurs more commonly on a north-south axis than an east-west axis (Figure 5; Chabot 2011a). However, gene flow is reduced in areas where the species is resident year-round and at the northern periphery of the species’ range, specifically western Canada and Ontario.

Figure 5. Geospatial depiction of estimates of genetic relatedness for each genetic cluster for Loggerhead Shrikes sampled by Chabot (2011a). Darker areas indicate lower levels of gene flow among neighbouring sample areas. Lighter areas represent higher levels of gene flow among neighbouring sample areas. Figure recreated with permission of A. Chabot.

Map: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 5

Five map panels providing a geospatial depiction of estimates of genetic relatedness for each genetic cluster of Loggerhead Shrike sampled by Chabot (2011a). These panels are labelled “Excubitorides,” “Northeast,” “Migrans,” “Ludovicianus,” and ‘Mexicanus / Gambeli.” Sample localities are indicated. The degree of genetic admixture is indicated within a 150-kilometre radius of each locality. Genetic admixture appears to decrease with increasing distance between sample localities and to occur more commonly on a north-south axis than an east-west axis.

The apparent return rate of young shrikes to their natal area is low. Collister and DeSmet (1997) resighted 1.2% of juveniles in Alberta and 0.8% of juveniles in Manitoba in the year following banding. In Ontario, the return rate for nestlings ranged from 3.1% to 12% (Okines and McCracken 2003, 2005). In the United States, return rates of young birds is also low: 3.6% in Virginia (Luukkonen 1987); 2.4% in Indiana (Burton and Whitehead 1990); 1.7% in Virginia (Blumton 1989); 1.1% in Missouri (Kridelbaugh 1982); 0.8% in North Dakota; and 0.0% in Minnesota (Brooks and Temple 1990b).

In Alberta, juveniles dispersed 12.4 km on average and up to 70 km from their natal site (Collister 1994). In Manitoba, natal dispersal averaged 15.4 km. In Ontario, nestlings have been found to return, in general, to within 44 km of their natal site, although larger movements (150+ km) have been observed (Okines and McCracken 2003; Chabot 2011b). Nestlings moved 9.9 to 15.0 km on average in Ontario (Okines and McCracken 2003). However, measures of dispersal distance based on banding studies largely reflect search effort and search distance, and should not be taken too literally.

In Ontario, return rates of banded adults have ranged from 11% to 28% (Okines and McCracken 2003, 2005). In Alberta, 32% of adults were resighted in the following year, while only 16% of adults were resighted in Manitoba (Collister and De Smet 1997; Collister 2013). Elsewhere, return rates vary among areas: 47% in Missouri (Kridelbaugh 1982), 41% in Indiana (Burton and Whitehead 2002), 30% in Idaho (Woods 1994), and 14% in North Dakota (Haas and Sloane 1989). Because return rates reflect apparent adult survivorship, Collister (2013) suggested that the values noted above for Loggerhead Shrikes were generally lower than those for other songbirds, suggesting that the species exhibits relatively poor adult survivorship in many regions.

In North Dakota, nest site fidelity rates of 28% for adult males and 5% for females were observed (Haas and Sloane 1989). In southern Idaho, 30% of all banded adults returned the following year to their prior territories (Woods 1994). In Missouri, 47% of males and 0% of females returned to their previous nesting area.

Collister and De Smet (1997) found that the mean distance moved by adults between successive years was 1.9 km in Alberta and 3.1 km in Manitoba and suggested that 95% of adults can be expected to return to within 4.7 km of their previous year’s nest site. Dispersal distance was greater among females in both Alberta and Manitoba. In Ontario, adults returned to within 47 km of their original banding location (mean 18.6 km; Okines and McCracken 2003).

Throughout the species’ range, it would appear that territory and habitat patch reuse rates are higher than nest site fidelity rates (Yosef 1996; Pruitt 2000). Site reuse and site fidelity in Ontario appear to be positively correlated with successful reproduction (Glynn-Morris 2010). Breeding site fidelity in Manitoba also appeared to be positively affected by breeding success (Collister and DeSmet 1997).

Shrikes interact with a wide variety of birds, presumably in defence of foraging areas (Cadman 1985; Smith 1991; Collister 1994; Woods 1994; Yosef 1996). Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos), Burrowing Owls (Athene cunicularia; Yosef 1996) and American Kestrels (Falco sparverius) have been observed engaging in klepto-parasitism at shrike caches (A. Chabot pers. obs.). Northern Mockingbirds and Brown Thrashers (Toxostoma rufum) appear to cause shrikes to abandon territories and nest sites, even during incubation (Chabot unpubl. data). Fledgling shrikes have been observed being attacked or harassed by a number of species of passerine birds (Smith 1991). Interspecific competition with species like American Kestrel, European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) and Red Fire Ant (Solenipsis invicta) can appear to be contributing factors to local population demography (Cadman 1985; Lymn and Temple 1991; A. Chabot, pers. obs.), but there are no indications that interspecific competition has contributed to range-wide population changes of Loggerhead Shrikes.

A detailed synopsis of sampling effort and methodology can be found in the Search Effort section. The Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) provides the longest-term data set for the species across its range. However, BBS suffers from several limitations, and the credibility of regional results for Loggerhead Shrikes is considered to be low to moderate in Canada (Environment Canada 2013; A. Didiuk, pers. comm. 2014). Detection rates by BBS are low, because the species is very locally distributed, and its behaviour makes it difficult to detect with brief roadside visits. Targeted roadside surveys aimed at optimizing the detection of shrikes provide more reliable estimates of regional population sizes and trends than BBS (A. Didiuk, pers. comm. 2014). Survey methodology is standardized in Alberta and Saskatchewan, where targeted shrike surveys have been conducted using the same methodology every 5 years since 1987, most recently in 2013. However, the first year of the surveys in Alberta and Saskatchewan (1987) should not be included in trend analysis because of relatively poor sampling effort and observer inexperience (Prescott 2013; A. Didiuk, pers. comm. 2014). In Manitoba, Ontario and Québec, targeted annual surveys have largely focused on assessing occupancy of historical breeding sites and, to a lesser degree, apparently suitable habitat.

The Loggerhead Shrike’s global population (all subspecies combined) is estimated to be between 3.7 and 4.2 million birds, based on BBS data.

The Prairie subspecies of Loggerhead Shrikes consists of about 54,700 mature individuals, of which about 15,000 occur in Alberta, 39,600 occur in Saskatchewan, and 100-200 occur in Manitoba.

Adjusting for detectability, extrapolation of roadside observations in Alberta suggests a total provincial population of 7508 shrike pairs (~15,000 mature individuals) in 2013 (Prescott 2013). Abundances vary regionally, with the highest estimates occurring in the central-eastern portion of the province, followed by the southeast. No shrikes were found in the southwestern quadrant of Alberta.

Saskatchewan supports more Loggerhead Shrikes than Alberta. Using the same estimating technique as was used in Alberta, the most recent population estimate for Saskatchewan was about 39,600 shrikes in 2013 (Didiuk et al. 2014).

In Manitoba, annual counts of Loggerhead Shrike have been carried out since 1987. As of 2012, the population there is estimated to consist of about 50 pairs (100 mature individuals), though some birds likely went undetected. In the provincial Breeding Bird Atlas project now underway, breeding evidence had been reported in 36 10 x10 km squares up until the end of the 2013 breeding season.

In Ontario, a “reintroduction” program has been going on annually since 2001, using birds that were sourced as nestlings from Ontario. The reintroduction program has achieved some measure of success, as evidenced by the subsequent return of captive-bred birds that have successfully bred with wild mates (Imlay and Lapierre 2012). From 2004-2013, 698 captive-born birds were released to the wild in Ontario, from which 35 (5%) returned (Wildlife Preservation Canada pers. comm. 2014). Out of the 35 returns, 14 successfully bred (12 in Carden, 1 in Grey-Bruce, and 1 in Quebec), 10 were single birds (not paired), and 11 paired but failed to nest successfully.

While the Eastern subspecies is strongly dominated by wild birds (Chabot 2009, 2010, 2011b), the release program is considered to be an important measure to sustain the wild population (Tischendorf 2009). As such, captive-released adults are included in the population estimate. However, as per COSEWIC’s guidelines on manipulated populations, the shrikes that are retained in captivity do not effectively contribute to the wild population and are excluded from the population estimate.

In Ontario, targeted surveys for Loggerhead Shrike were begun in 1992, focusing on the Smiths Falls, Napanee and Carden core breeding areas, and to a lesser extent Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. About 50 breeding pairs were located in 1992, but the population has declined fairly steadily since then. Over the most recent 10 year-period from 2003 to 2013, the known number of breeding pairs in the province has ranged from 18 to 31 pairs (CWS unpubl. data 2014). Including unmated birds, the Ontario population likely stands at 50 to 100 adults, and is probably at the lower end of this estimate (see below).

Until 2003, the majority of the breeding pairs in Ontario occurred in the Napanee core area. However, the number of breeding pairs in this area has declined steadily, to only 5 pairs in 2012. Conversely, the number of breeding pairs in the Carden Plain has increased from ~5 pairs in the early 1990s to a high of 18 pairs in 2009. The increase may be due to captive breeding and release efforts initiated in 2003 in that area (Tischendorf 2009). However, while captive bred birds are found annually as part of the breeding population in this area, the majority of the breeding population is still composed of wild-source birds (Chabot 2009, 2010, 2011b).

No Loggerhead Shrikes were found breeding in the Smiths Falls limestone plain between 2000 and 2008, but up to three pairs have been recorded annually since 2009 (CWS unpubl. data). Despite captive breeding and release work near Dyer’s Bay on the Bruce Peninsula, shrikes have been located only sporadically on Manitoulin Island and in the Grey-Bruce core area over the past decade.

From 1980 to 1990, there were only 14 breeding records in Québec. During the first breeding bird atlas period (1984 to 1989), only 30 sightings were recorded, which included 7 confirmed breeding pairs (Gauthier and Aubry 1996). A broad-scale survey of all former breeding areas was undertaken in 1990, and only 1 pair was found (Cadman 1990), with an optimistic estimate of 10 breeding pairs (Robert and Laporte 1991). Two pairs were reported breeding in Québec in 1992 and 1 in 1993 (Grenier et al. 1999). Breeding evidence was found at three sites in 1995 (SOS-POP 2011). No other evidence of breeding was found between 1996 and 2009, despite surveys at former breeding sites and despite releases of 101 captive bred young in the Outaouais region from 2004 to 2009. One captive-bred bird released in Québec was subsequently located in the Carden core area in Ontario. In 2010, one breeding pair was found near the region where releases had been undertaken. This pair was composed of a wild male and a captive-bred female released from the Carden area in Ontario in 2009. The pair successfully fledged young, but only one bird was seen at this site in 2011 (F. Shaffer, pers. comm. 2012).

In summary, the Eastern subspecies of Loggerhead Shrikes (excluding birds held in captivity) is currently estimated to consist of no more than 110 mature individuals, with fewer than 100 in Ontario and fewer than 10 in Québec.

The Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) provides range-wide population trend information. Large-scale declines in the species likely began before the inception of the BBS (Cade and Woods 1997), and thus population trends estimated by BBS are likely conservative figures for overall declines over the past century. The Loggerhead Shrike has been declining at an average rate of -3.2% per year survey-wide (U.S. and Canada combined) from 1966 to 2011, and -1.7% per year for the 10-year period from 2001 to 2011 (see Table 3, which also includes confidence intervals on these estimates).

| Region | 1987 Tablenote3 | 1993 | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | 67,048 | 116,135 | 93,617 | 86,697 | 35,582 | 39,579 |

| Alberta Tablenote2 | 5,650 | Na | 23,428 | 16,654 | 15,442 | 15,016 |

| Manitoba | 530 | 654 | 332 | 162 | 98 | 70 Tablenote4 |

| Region | N of routes | 1970 Tablenote1.1-2011 Trend |

1970-2011 95% CI |

2001-2011 Trend |

2001-2011 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | 2011 | -3.2 | -3.6, -2.9 | -1.7 | -2.5, -0.9 |

| United States | 1870 | -3.2 | -3.6, -2.9 | -1.7 | -2.5, -0.9 |

| Canada | 123 | -2.9 | -4.9, -1.3 | -1.4 | -4.6, 3.07 |

| Alberta | 40 | 0.3 | -1.7, 2.4 | 1.3 | -1.8, 8.1 |

| Saskatchewan | 49 | -3.6 | -5.5, -1.6 | -3.0 | -7.3, 4.0 |

| Manitoba | 16 | -5.1 | -9.5, -1.1 | -5.2 | -11.3, 0.2 |

| Prairie Potholes (AB, SK, MB) | 105 | -2.8 | -4.8, -1.2 | -1.3 | -4.6, 3.1 |

| Ontario | 18 | -12.4 | -17.6, -7.9 | -12.2 | -20.8, -3.3 |

BBS results for the Loggerhead Shrike in the United States show mean annual declines of 3.2% from 1966 to 2011 and 1.7% for the 10-year period from 2001 to 2011 (Table 3). Across its Canadian range, BBS data (mostly reflecting the Prairie subspecies) indicate a mean annual decline of 2.9% from 1970 to 2011, and -1.3% from 2001 to 2011, though the latter trend is not statistically significant (see Table 3). Details for each designatable unit are presented below.

It is again important to point out that the BBS provides one estimate of population trend for the Prairie subspecies, and that its limitations give it a reliability rating that ranges between low and medium (Environment Canada 2013). Based on BBS, there was a statistically significant decline of 2.8% per year for the period 1970-2011 (equivalent to a loss of 69% over the period), and a non-significant decline of 1.3% per year for the 10-year period from 2001-2011 (equivalent to -13% over the period; Table 3; Figure 6). If the BBS long-term trend estimate (-2.8%/year) is used to infer the most recent 10-year trend, which probably gives a better representation than the short-term trend, then BBS indicates an overall loss of 24.7% of the Prairie subspecies over 10 years.

Figure 6. Annual indices of population change for the Prairie subspecies of Loggerhead Shrike in Canada based on Breeding Bird Survey data, 1970-2011. Reproduced from Environment Canada (2013).

Chart: © Environment Canada

Long description for Figure 6