Wild Species 2005: chapter 3

Freshwater mussels

Freshwater mussels: Freshwater mussels are molluscs belonging to the order Unionoida, class Bivalvia. Like other bivalves, freshwater mussels are soft-bodied, non-segmented invertebrates, with a pair of hinged shells and a muscular foot. - Adapted from Metcalfe-Smith et al, 2005.

Quick facts

- Worldwide, there are nearly 1000 species of freshwater mussels, 55 of which have been found in Canada.

- Freshwater mussels live in lakes and rivers throughout Canada where they improve water clarity and quality by filtering algae and bacteria from the water.

- Just over a third (35%) of Canadian freshwater mussels have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of Secure while 27% have Canada ranks of Sensitive, 16% have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk and 15% have Canada ranks of At Risk.

- Over two-thirds of freshwater mussels in the United States have gone extinct or are currently vulnerable to extinction, according to 'Rivers of Life', a NatureServe report that summarizes the status of freshwater species.

- Freshwater mussels have a unique life cycle, during which the larvae must attach to the fins or gills of a host species, usually a fish, before they can mature into adults.

Background

Freshwater mussels (order Unionoida) are fascinating animals with a unique method of reproduction and an important role in maintaining water quality. Freshwater mussels are molluscs belonging to the class Bivalvia; other bivalves include oysters and scallops. Like all bivalves, freshwater mussels are soft-bodied invertebrates living within a shell made of two halves joined by a hinge. Freshwater mussels live in the bottom of streams, rivers and lakes throughout Canada, reaching their greatest diversity in the lower Great Lakes region.

The simple body of a freshwater mussel includes a mantle, which produces the hard, calcareous shell, a muscular foot, used for moving around in the sediment, and gills which are used to obtain oxygen from the water. Freshwater mussels feed on plankton and other organic particles suspended in the water by filtering water through their gills and extracting food particles. Waste is deposited on the sediment around the mussel, providing food for bottom-feeding invertebrates and fishes. By removing algae and bacteria from the water during feeding, freshwater mussels improve the clarity and quality of the water. Freshwater mussels also play important roles in nutrient cycles, food webs and in mechanically oxygenating the sediment in which they live, making them an important component of freshwater ecosystems.

The reproductive cycle of freshwater mussels is unique, firstly because the female broods fertilized eggs within her shell, rather than releasing them to drift on the current, and secondly because the specialized larvae, or glochidia, are parasitic, meaning that they require a vertebrate host to reach maturity. Once the glochidia have hatched and been released by the female, they find a host and clamp onto its gills or fins, forming a small cyst where they will develop into juvenile mussels. When development is complete, the juvenile mussels drop from the host down to the sediment, where they grow and mature into adult mussels. Each species of freshwater mussel has specific host species necessary for completion of its life cycle. For example, the Alewife Floater (Anodonta implicata), found in Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, relies on the Alewife fish (Alosa pseudoharengus) for development of its young. One freshwater mussel, the Salamander Mussel (Simpsonaias ambigua), can only mature on the gills of a Mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus), an aquatic salamander.

Many freshwater mussel species have developed unique strategies to increase the chances of their young finding a suitable host. For example, the female Wavyrayed Lampmussel (Lampsilis fasciola) tempts a potential host close using a lure made of a special flap of tissue that resembles a small fish. Kidneyshell (Ptychobranchus fasciolaris) uses a slightly different kind of lure; the Kidneyshell's glochidia are wrapped in packages that resemble small fish. Each package is released into the water, and when a real fish bites into the package, the glochidia are released to attach to the new host.

Many freshwater mussel species have developed unique strategies to increase the chances of their young finding a suitable host. For example, the female Wavyrayed Lampmussel (Lampsilis fasciola) tempts a potential host close using a lure made of a special flap of tissue that resembles a small fish. When a larger fish tries to bite the lure, the glochidia are released to attach to the host. The Kidneyshell (Ptychobranchus fasciolaris) uses a slightly different kind of lure; the Kidneyshell's glochidia are wrapped in packages that resemble small fish. Each package is released into the water, and when a real fish bites into the package, the glochidia are released to attach to the new host. Freshwater mussels are an important tool for monitoring the health of aquatic systems because they are sensitive to a wide range of environmental factors including the health and diversity of local fish communities and levels of dissolved oxygen in the water. Therefore, a reduction in the diversity or abundance of freshwater mussels, or a shift in the freshwater mussel community towards species that are tolerant of poor water quality can indicate a negative change in the ecosystem. Freshwater mussels have also been used to study contaminants in aquatic systems. For example, the Eastern Elliptio (Elliptio complanata) has been used to examine the spatial patterns of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) contamination in the Detroit River, Ontario.

Status of knowledge in Canada

Much of our knowledge of the life cycle of freshwater mussels comes from attempts to propagate mussels for the pearl button industry, which was important in the United States in the early 1900s. While this early research provided an outline of the typical life cycle of freshwater mussels, relatively little is known about the life cycle of specific freshwater mussel species. For example, the host(s) of many Canadian freshwater mussels remain unknown. Also, little is known about the juvenile stage of the life cycle, between the time that the mussel first drops from its host until the time when it reaches sexual maturity.

Recent research into freshwater mussels has focused on the impacts of Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and Quagga Mussels (Dreissena bugensis), on native freshwater mussels.Footnote1 Zebra Mussels and Quagga Mussels are native to Europe, but both species have been accidentally introduced into the Great Lakes in recent years. Zebra Mussels fasten onto the shells of native freshwater mussels, sometimes in huge numbers, interfering with normal functions such as feeding and burrowing. This can eventually lead to the death of the infested mussel. Since the introduction of Zebra Mussels, the abundance and distribution of native freshwater mussel communities in the Great Lakes system has declined rapidly. In fact, Zebra Mussels have seriously undermined the population stability of several native freshwater mussel species including the Northern Riffleshell (Epioblasma torulosa), the Kidneyshell and the Round Pigtoe (Pleurobema sintoxia), all of which have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of At Risk. The Quagga Mussel is thought to adversely affect native freshwater mussels, but less is known about the impacts of the Quagga Mussel than the Zebra Mussel.

Recent concerns over declines in freshwater mussels have stimulated new research into the distribution and abundance of native freshwater mussels, particularly in the Great Lakes region. Historical records of freshwater mussel occurrence within this area have been compiled into a single database to facilitate the comparison of current and historical distribution patterns, while new surveys of mussel habitat in this region have highlighted the critical importance of certain rivers and lakes in supporting populations of At Risk species. For example, the Sydenham River, Ontario, is a major refuge for several freshwater mussel species that are protected under Canada's endangered species legislation, the Species At Risk Act, including the Snuffbox (Epioblasma triquetra), Rayed Bean (Villosa fabalis) and the Salamander Mussel.

Systematic surveys in other parts of the country have also improved our knowledge of freshwater mussel abundance and distribution. For example, a recent survey in southern Manitoba showed evidence of declining diversity and abundance of freshwater mussels in a range of habitats, while surveys of the Saint John River system in New Brunswick in 2001 and 2002 revealed the existence of large populations of the Yellow Lampmussel (Lampsilis cariosa), previously thought to be extirpated from the province.

Richness and diversity in Canada

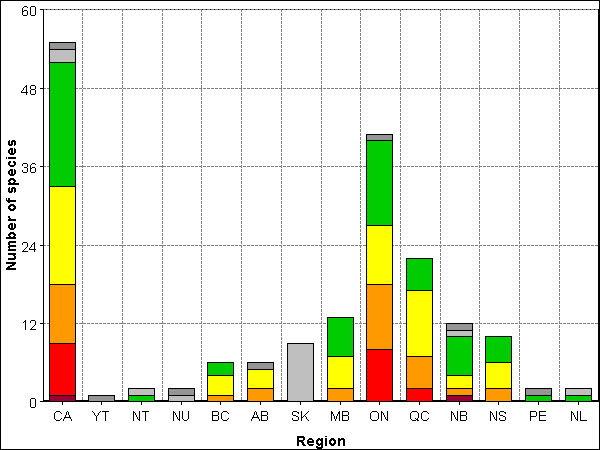

A total of 55 species of freshwater mussels has been found in Canada. Freshwater mussels are found in every province and territory of Canada, but species richness is highest from Manitoba east to Nova Scotia (Figure 2-2-i, Table 2-2-i). Within Canada, 18 species of freshwater mussels are found only in Ontario, including 14 species with Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of At Risk or May Be At Risk. The high diversity of freshwater mussels in Ontario, particularly in the Lake St. Clair and western Lake Erie region, is related to patterns of recolonization since the last period of glaciation.

Species richness of freshwater mussels in the west and northwest is generally low (Figure 2-2-i, Table 2-2-i), but five of the six species of freshwater mussels in British Columbia are found nowhere else in Canada. Similarly, the only freshwater mussel in the Yukon, the Yukon Floater (Anodonta beringiana), is found nowhere else in Canada.

Species spotlight - Yellow Lampmussel

Yellow Lampmussels, Lampsilis cariosa, are recognised by their waxy, egg-shaped, yellow shells. As is typical of many mussel species, the females tend to have fatter, more rounded shells than the males, providing space for the female to brood eggs within her shell. Yellow Lampmussels are found in medium to large rivers along the east coast of North America from Georgia to Nova Scotia. Like other freshwater mussels, they feed on plankton and other organic matter filtered from the water. The host fishes for their parasitic larvae are probably White Perch (Morone americana) and Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens).

Yellow Lampmussels are only known from two river systems in Canada; the Sydney River on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia and the Saint John River drainage system in New Brunswick. Until recently, it was feared that Yellow Lampmussels had been lost from New Brunswick but surveys of the lower Saint John River drainage and its tributaries in 2001 and 2002 found a large, wellestablished population, potentially numbering more than 1 million individuals. The size of this population contrasts sharply with the status of the species elsewhere, as it is listed as Threatened or Endangered throughout much of its range in the United States. Due to its limited occurrence, this species has a Canada rank of Sensitive.

Species spotlight - Round Hickorynut

Round Hickorynuts are medium-sized freshwater mussels, with distinctive round, brown shells. Once widespread in the lower Great Lakes, Round Hickorynuts were probably extirpated from Lake Erie as early as 1950, due to declining water quality. Following the invasion of the Zebra Mussel in the late 1980s, Round Hickorynuts also disappeared from off-shore waters of Lake St. Clair. In 1999, a previously unknown population of Round Hickorynuts was discovered in a shallow-water refuge on the north shore of Lake St. Clair. This refuge harbours 22 species of freshwater mussels, several of which were feared to have been lost from the lake. Zebra Mussel densities in this refuge are relatively low, probably due to the harsh conditions in this shallow area of the lake, where mussels are exposed to fluctuating water levels and ice scour. The only other known Canadian population of Round Hickorynuts is in the Sydenham River, where they exist in very low numbers and are exposed to the negative effects of poor water quality and siltation. In all, Round Hickorynuts have been lost from approximately 90% of their former Canadian range.

The host fish for the Round Hickorynut is suspected to be the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida), although this has not been confirmed. Eastern Sand Darters (Canada rank: At Risk) have declined in number in recent years, due to declining water quality and increased siltation, but still exist in both Lake St. Clair and the Sydenham River.

The long-term prospects for Round Hickorynuts in Canada are uncertain, due to the abundance of Zebra Mussels in Lake St. Clair and the apparent sensitivity of Round Hickorynuts to poor water quality. In addition, further population declines or range reductions of the suspected host fish, the Eastern Sand Darter, may also prove detrimental to the Round Hickorynut. Round Hickorynuts have a Canada rank of At Risk.

Results of general status assessment

A total of 55 freshwater mussels has been found in Canada, of which just over one-third (35%, 19 species) have a Canada rank of Secure (Figures 2-2-i and 2-2-ii, Table 2-2-i). A further 31% have Canada ranks of At Risk (eight species) and May Be At Risk (nine species) and 27% have Canada ranks of Sensitive (15 species). One species, the Dwarf Wedgemussel (Alasmidonta heterodon) has a Canada rank of Extirpated (2%). Finally, 4% have Canada ranks of Undetermined (two species) and 2% have Canada ranks of Not Assessed (one species).

Long description for Figure 2-2-i

Figure 2-2-i illustrates the total number of freshwater mussel species in Canada and per region, broken down into rank status. In Canada there was 1 extirpated species, 8 at risk, 9 may be at risk, 15 sensitive, 19 secure, 2 undetermined, and 1 not assessed for a total of 55 freshwater mussel species. In the Yukon there was 1 species not assessed, for a total of 1 species. In the Northwest Territories there was 1 secure species and 1 undetermined for a total of 2 species. In Nunavut there was 1 undetermined species, and 1 not assessed for a total of 2 species. In British Columbia there was 1 species that may be at risk, 3 sensitive, and 2 secure for a total of 6 species. In Alberta there were 2 species that may be at risk, 3 sensitive, and 1 not assessed for a total of 6 species. In Saskatchewan there were 9 species that were undetermined for a total of 9 species. In Manitoba there were 2 species that may be at risk, 5 sensitive, and 6 secure, for a total of 13 species. In Ontario there were 8 species at risk, 10 may be at risk, 9 sensitive, 13 secure, and 1 not assessed for a total of 41 species. In Quebec there were 2 species at risk, 5 may be at risk, 10 sensitive, and 5 secure for a total of 22 species. In New Brunswick there was 1 extirpated species, 1 may be at risk, 2 sensitive, 6 secure, 1 undetermined, and 1 not assessed for a total of 12 species. In Nova Scotia there were 2 species that may be at risk, 4 sensitive, and 4 secure for a total of 10 species. In Prince Edward Island there was 1 secure species and 1 not assessed, for a total of 2 species. In Newfoundland and Labrador there was 1 secure species and 1 undetermined for a total of 2 species.

| Rank | CA | YT | NT | NU | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extirpated | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Extinct | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| At risk | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| May be at risk | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sensitive | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Secure | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Undetermined | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Not assessed | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Exotic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Accidental | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 55 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 13 | 41 | 22 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 2 |

Threats to Canadian freshwater mussels

Freshwater mussels are potentially susceptible to a number of threats including habitat destruction, poor water quality, siltation, damming and channelization of streams and rivers, riparian and wetland alterations, and agricultural run-off. These threats may act directly on the mussel population or have an indirect impact through declines in the host fish species that are required to complete the mussel's life cycle.

The introduction of the Zebra Mussel has had a dramatic impact on native freshwater mussel populations in recent years, causing sharp declines in the numbers and diversity of native freshwater mussels in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system and in other rivers and inland lakes that have been colonized by this invasive species. Although the affected drainages represent only a portion of the range of freshwater mussels in Canada, they are nonetheless host to some of the most abundant and diverse assemblages of freshwater mussels in the country. Therefore, although the affected area is small, the negative impact of Zebra Mussels on native freshwater mussels in Canada has been dramatic.

Conclusion

Freshwater Mussels are less well known than many other groups of freshwater animals and there are few Canadian freshwater mussel experts. Nevertheless, recent declines in abundance and diversity have stimulated increased interest and research into Canadian freshwater mussels. New surveys have improved knowledge of the distribution and abundance of freshwater mussels and demonstrated the importance of key lake and river refuges for maintaining the diversity of freshwater mussels in Canada. This is a group containing a high proportion of species with Canada ranks of At Risk, and protecting the diversity of Canadian freshwater mussels will be a major challenge.

Further information

Armstrong, M. 1996. Freshwater mussels. Biodiversity Associates Report No. 4. Biodiversity Convention Office, Environment Canada, Ottawa. 16 pp (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Clarke, A. H. 1981. The freshwater molluscs of Canada. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa. 446 pp

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Freshwater mussels of the Upper Mississippi River system. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Lee, J. S. 2000. Freshwater molluscs. British Columbia Conservation data centre, Victoria, British Columbia. 6 pp (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Master, L. L., Flack, S. R. and Stein, B. A. Eds. 1998. Rivers of life: Critical watersheds for protecting freshwater biodiversity [PDF, 7.26 MB]. The Nature Conservancy, Virginia. 77 pp (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., MacKenzie, A., Carmichael, I. and McGoldrick, D. 2005. Photo field guide to the freshwater mussels of Ontario. St. Thomas Field Naturalist Club Inc., St. Thomas, Ontario. 60 pp

Graf, D. and Cummings, K. 2004. The MUSSEL project. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Canadian Museum of Nature. 2004. The nature of the Rideau River: Native freshwater mussels. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Cummings, K. S. and Mayer, C. A. 1992. Field guide to freshwater mussels of the Midwest. Illinois Natural History Survey Manual 5. 194 pp (Accessed August 24, 2005).

The Tree of Life. 1995. Mollusca. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

References

Barr, D. W. 1996. Freshwater Mollusca (Gastropoda and Bivalvia). In Assessment of species diversity in the mixedwood plains ecozone. Edited by I. M. Smith, Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network, Environment Canada. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Clarke, A. H. 1973. The freshwater molluscs of the Canadian interior basin. Malacologia 13(1- 2):1-509

COSEWIC. 2003. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the kidneyshell Ptychobranchus fasciolaris in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. vi + 32 pp

COSEWIC. 2003. COSEWIC assessment and update status on the round hickorynut Obovaria subrotunda in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. vi + 31 pp

COSEWIC 2004. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the yellow lampmussel Lampsilis cariosa in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. vii + 35 pp

Locke, A., Hanson, J. M., Klassen, G. J., Richardson, S. M. and Aubé, C. I. 2003. The damming of the Petitcodiac River: species, populations and habitats lost. Northeastern Naturalist 10(1):39- 54

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L. and Cudmore-Vokey, B. 2004. National general status assessment of freshwater mussels (Unionacea). NWRI Contribution No. 04-027.

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., Staton, S. K., Mackie G. L. and Lane N. M. 1998. Biodiversity of freshwater mussels in the lower Great Lakes drainage basin. NWRI contribution No.97-90. (Accessed August 24, 2005).

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., Staton, S. K., Mackie, G.L. and West, E. L. 1998. Assessment of the current conservation status of rare species of freshwater mussels in Southern Ontario. NWRI contribution No. 98-019.

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., Staton, S. K., Mackie, G. L. and Lane, N. M. 1998. Changes in the biodiversity of freshwater mussels in the Canadian waters of the lower Great Lakes drainage basin over the past 140 years. Journal of Great Lakes Research 24(4):845-858

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., Staton, S. K., Mackie, G. L. and Lane, N. M. 1998. Selection of candidate species of freshwater mussels (Bivalva: Unionidae) to be considered for national status designation by COSEWIC. Canadian Field-Naturalist 112(3):425-440

Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., Staton, S. K., Mackie, G.L. and Scott, I. M. 1999. Range, population stability and environmental requirements of rare species of freshwater mussels in southern Ontario: a 1998 Endangered Species Recovery Fund Project: final report to the World Wildlife Fund Canada. NWRI Contribution No. 99-058

Nalepa, T. F. and Gauvin, J. M. 1988. Distribution, abundance and biomass of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia:Unionidae) in Lake St. Clair. Journal of Great Lakes Research 14(4):411-419

Nalepa, T. F., Hartson, D. J., Gostenik, G. W., Fanslow, D. L. and Lang, G. A. 1996. Changes in the freshwater mussel community of Lake St. Clair: from Unionidae to Dreissena polymorpha in eight years. Journal of Great Lakes Research 22(2):354-369

Nalepa, T. F., Manny, B. A., Roth, J. C., Mozley, S. C. and Schloesser, D. W. 1991. Long-term decline in freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) of the western basin of Lake Erie. Journal of Great Lakes Research 17(2):214-219

O'Rourke, S. M., Balkwill, K., Haffner, G. D. and Drouillard, K. G. 2003. Using Elliptio complanata to assess bioavailable chemical concentrations of the downstream reaches in the Detroit River system - Canadian and American shorelines compared. Global Threats to Large Lakes: Managing in an Environment of Instability and Unpredictability p181-182

Pip, E. 2000. The decline of freshwater molluscs in southern Manitoba. Canadian Field-Naturalist 114(4):555-560

Zanatta, D. T., Mackie, G. L., Metcalfe-Smith, J. L., and Woolnough, D. A. 2002. A refuge for native freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) from impacts of the exotic zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) in Lake St. Clair. Journal of Great Lakes Research 28(3):479-489