Wild species 2010: chapter 19

Insects: Selected macromoths

Lepidoptera - Order of insects that includes moths and butterflies. They can be distinguished from all other insects by their two pairs of scale-covered wings, which are often brightly coloured. Lepidopterans undergo complete metamorphosis: eggs are laid, from which larvae hatch, and a pupal stage follows, during which the final adult form takes shape. Moths are mostly nocturnal. macromoths

Quick facts

- About 180 000 species of lepidopterans have been described, but hundreds more are discovered each year. The total number of species in the world is probably between 300 000 and 500 000. About 5300 species are known from Canada, 5000 of which are moths. Only 236 species were assessed in this report.

- Moths represent about 90% the lepidopterans (the others are butterfly species). Moths are then much more diverse, but are less well known. In this report, only some selected groups of moths were assessed.

- When excluding species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental, the majority (84%) of selected macromoths in Canada have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of Secure, while 11% have Canada ranks of Sensitive and 5% have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk. One species has a rank of At Risk following a detailed COSEWIC assessment.

- Of the assessed species, seven species in total are Exotic in Canada, including the Asian Silk Moth (Bombyx mori).

- Most adult moths are nocturnal, and are attracted to artificial lights.

- Although moth caterpillars are often blamed for eating woollen clothing, only two out of the many thousands of moth species actually feed on wool.

Background

Moths are usually nocturnal and less brightly coloured than their day-flying cousins, the butterflies. They are so diverse and poorly known that the majority of species have probably not even been discovered and described. The earliest fossils of lepidopterans are about 190 million years old, but most evolutionary radiation in the group occurred at the same time as that of the flowering plants, in the Cretaceous Period, 65 to 145 million years ago. Because the butterfly branch of the lepidopterans is embedded in the midst of the family tree, the moths as a whole are not a formal taxonomic group. For convenience, moths are often divided into macromoths (usually larger species) and micromoths (the primitive side of the family tree; usually very small species). They are formally divided into 118 families. At the species level, many lepidopterans can be identified by their wing patterns; others require examination of the complex structures of the genitalia, which usually have very good distinguishing characters.

Most moth groups are too poorly known to be assigned General Status ranks or even do a species list; however the giant silk moths (Family Saturniidae, 23 species), silk moths (Family Bombycidae, 3 species), sphinx moths (Family Sphingidae, 58 species), tiger moths (Family Erebidae, subfamily Arctiinae, 95 species) and underwings (Family Erebidae, genus Catocala, 57 species) are well enough known that they are dealt with in this report. It is hoped that more moth groups will be included in future versions of this report as they become better known.

Like all other insects, adult lepidopterans have six legs and three major body segments: the head; the thorax, with legs and wings and the muscles to power them; and the abdomen, with the majority of the digestive and reproductive organs. All adult lepidopterans have two pairs of scale-covered wings, which set them apart from all other insects. The differences between moths and butterflies are not always readily apparent. Butterflies have thin, clubbed, or hooked antennae, tend to be brightly coloured and fly during the day, whereas moths often have feathered antennae, and most fly at night and tend to be drably coloured. However, there are many exceptions to this pattern and no single characteristic will always separate all species of moths from all butterflies.

The vast majority of a moth’s life is spent as a larva, or caterpillar. Caterpillars of most species feed on living plant parts, especially leaves, but some feed on flowers, buds, seeds, stems, roots, and bark. Some feed externally; others are miners or borers. A few species stimulate gall formation on their host plants. Many species are host-specific; others feed on a wide variety of plants. The larvae of a few species feed on fungi or detritus, and a few are predators or parasites. Larvae are usually voracious feeders that have to store up most of the food reserves required by the adults to disperse and reproduce. Some adult moths feed on nectar, but many do not feed at all, and most live for only one or two weeks. Adults of most species have a short, specific flight period, but some species have multiple broods and may be found as adults over the whole summer. Most species spend the winter in dormancy as either an egg or a pupa, but some overwinter as larvae or adults.

Moths form an essential part of most terrestrial ecosystems. As herbivores, they help to regulate plant growth and when their population levels are high they can drive plant community succession. Many adult moths are important pollinators. Larvae and adults are major food sources for many other animals, including songbirds, bats, and other insects. A few species of moths are such good competitors with humans that they are considered pests. This category includes pests of food crops, trees and timber, and stored food products. Although only two moth species have larvae that eat silk and wool products, this extremely rare feeding habit is often attributed in error to the whole group. Silk itself comes from human exploitation of the Asian Silk Moth (Bombyx mori).

Moths are renowned for their sense of smell. The females of most species release complex, species-specific chemical compounds (pheromones), which can be detected by males from great distances. The males locate females by following their scent plumes, often producing their own pheromones, which they use at close range during courtship. Some moths also have a well-developed sense of hearing, which has evolved as a method to detect the sonar of bats, which are important predators of moths. One group, the tiger moths, actually produce sound to interfere with the signals of bats or to advertise the fact that they are unpalatable to predators.

Giant silk moths (Saturniidae) include the largest resident moths in Canada. They typically have stout, furry bodies; small heads with vestigial mouthparts; and large wings, often with brightly coloured spots that mimic the eyes of owls and snakes. Larvae of saturniids usually bear scoli (spiny warts), and some can cause skin irritation. Silk moths (Family Bombycidae) include, among others, the Asian Silk Moth, an Exotic species in Canada. Sphinx moths (Sphingidae) have stout, pointed bodies with elongate forewings and small hindwings. Most larvae of sphinx moths have a characteristic horn at their tail end; when disturbed, some species rear up in a characteristic pose reminiscent of the ancient Egyptian sphinx, hence the common name for this group. Tiger moths (Erebidae: Arctiinae) are medium-sized moths, usually with brightly colored, patterned wings. Many species have warning coloration and possess the ability to produce sound with a specialized structure (the tymbal), which is used to characterize the group. They have historically been treated as a separate family (the Arctiidae), but have recently been placed as a subfamily of the Erebidae. Their larvae are usually densely hairy and include the well-known woolly bear caterpillars. The underwings (Erebidae: genus Catocala) are large moths with cryptically patterned forewings, and usually brightly coloured hindwings. Their larvae are also usually cryptically coloured.

Status of knowledge

Overall, moths are not very well known in Canada; with the state of knowledge being comparable to where our knowledge of birds was some 200 years ago. Even basic species descriptions and occurrence information is scattered among hundreds of obscure scientific publications and museum drawers. Unlike many vertebrate groups, there is no single guide book to all the species that occur here. Good modern works exist for a few groups, including the saturniids and sphingids, but not for the majority of moth families. We do not even have a comprehensive national moth species list; although provincial lists have been produced for British Columbia, Alberta, Quebec, and the Yukon.

For most of the moth species included in the Wild Species 2010 report, the host plants are known and their distributions are reasonably well-known; however, for some species, we still do not know enough about them to assign general status ranks other than Undetermined. This report covers only 236 species out of the approximately 5000 species thought to occur in Canada, all belonging to the better-known macromoth group. Our knowledge of the remaining species is generally rather poor except for a few pest species.

Moths are better known in eastern Canada than in the west and the north, and overall the macromoths are far better known than the micromoths. The efforts of amateur collectors have been especially important in learning what we do know about moths in Canada. Much more inventory work and research is required to fully document the moth fauna, and to better understand their distributions and life cycles. Without this information, many species may be threatened with extirpation from Canada before we even know of their existence.

Richness and diversity in Canada

Approximately 5000 moth species are known from Canada. However, many more remain to be discovered, and the number that actually lives here is thought to be closer to 7000. This report covers only a small percentage of that diversity (5 groups for a total of 236 species). Major hotspots of moth diversity are the eastern deciduous forests with their high plant diversity, and arid habitats in the west. Some species of moths are known in the world only from the unglaciated tundra of Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Alaska.

Species spotlight - Mountain Tiger Moth

The Mountain Tiger Moth (Pararctia yarrowii) is emblematic of Canada’s western cordilleran region, inhabiting lofty peaks and rocky alpine meadows. When Richard Stretch named this species in 1874, he described it as “the most beautiful of the American Arctians [tiger moths]”. Like most tiger moths that occur in the alpine and arctic regions, they are only rarely observed, probably a result of the fact that the larvae (collectively called woolly bears) take multiple years before they are full-grown and ready to pupate – an adaptation that has permitted this species to thrive on low-growing plants during the short alpine summers. Unlike the relatively long-lived larvae, the adult moths live only for several weeks, and do not feed, living on the fat stores accumulated as a larva. Larvae spend winters beneath rocks, and talus slopes and rock fields are therefore important components of this species’ habitat.

Like many alpine moths, the Mountain Tiger has evolved to fly during the daytime, since most nights are too cold for flight. Females spend considerably less time flying than males; immediately following emergence from the pupa, females seek higher ground, such as the top of a boulder, from which to perch while emitting mating pheromones. These pheromones are produced from the tip of the abdomen, and any males on their patrol flights will soon narrow in on the calling female to mate. The life history is still incompletely known, but eggs are probably laid indiscriminately among low-growing plants, which provide food for the young larvae.

The Mountain Tiger Moth is found from Yukon southward through the Rocky Mountains to northern Utah, and in the west portion of British Columbia and the Washington Coast Ranges. Known localities are few, and this beautiful moth still remains to be documented in many of western Canada’s mountain ranges. It is ranked as Secure in Canada.

Species spotlight - Western Poplar Sphinx

The Western Poplar Sphinx (Pachysphinx occidentalis) found in Canada only in the wooded parts of the arid grasslands region of southern Alberta and western Saskatchewan, is an enigmatic moth for a number of reasons. Until recently, they were thought to be a pale population of the common and widespread Big Poplar Sphinx (Pachysphinx modesta). However, DNA data indicates that these are two different species, and preliminary rearing studies support this. It still remains to be determined whether or not this Canadian prairie moth is the same species as the southern (USA) species Pachysphinx occidentalis, or an undescribed species needing an entirely new name. Much remains to be learned about our moths, even ones as large and showy as this one! Above all else, the Western Poplar Sphinx is simply one of our most impressive and beautiful insects. For the moment, it is ranked as Secure in Canada.

The Western Poplar Sphinx may also be the largest insect in Alberta, in terms of mass, and perhaps the largest in all of Canada. The mature larvae are huge green “hornworms”, so-called because of the short spine-like “tail” on the rear of the larva, and found on the larvae of most species of sphinx moths. The mature larvae are also decorated with a series of oblique white lines along the flanks. Although large and voracious, they are harmless, and neither sting with their “horn” nor occur in large enough numbers to cause damage to trees. These larvae are rarely encountered until they mature in late summer, at which time they stop feeding, leave the trees where they have spent the summer and wander about the ground looking for a suitable place to burrow, pupate and spend the winter. They re-appear in spring as adult moths once the cottonwood trees leaf out. The adults are active only at night, and are most often encountered in the morning, resting near the lights that attracted them the night before. Adult Western Poplar Sphinx have poorly developed and apparently non-functional mouthparts, and thus are unable to feed. They must live on whatever resources they were able to store as fat during the larval stage, and are thus short-lived, living only long enough to find a mate and start the cycle anew.

Results of general status assessment

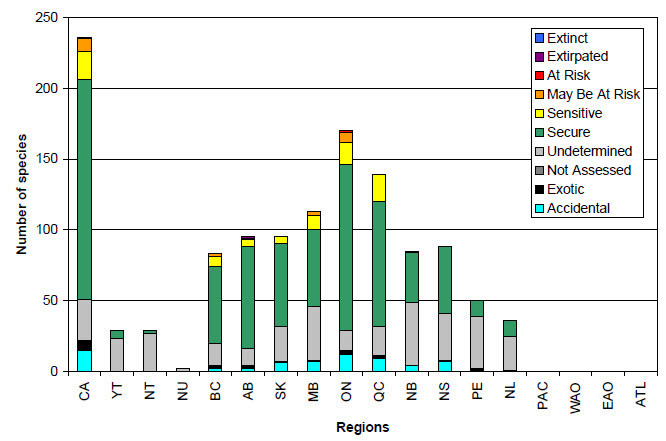

The Wild Species 2010 report marks the first assessment for any moth species. These rankings were completed in March 2010, and reflect the classification and available knowledge at that time. Among the 236 species that were assessed, 155 species were ranked as Secure (66%, figure 19 and table 26), 20 species were ranked as Sensitive (8%), nine species were ranked as May Be At Risk (4%). One species in ranked as At Risk following a detailed COSEWIC assessment of Endangered, namely the Bogbean Buckmoth (Hemileuca sp.), a new species that still does have an official scientific name.

A total of 29 species (12%) were Undetermined, while 15 species (6%) where Accidental. Also, seven species (3%) are Exotic in Canada. The vast majority of Canadian moth species remain unranked, pending better knowledge of the group.

Long description for Figure 19

Figure 19 shows the results of the general status assessments for selected macromoth species in Canada in the Wild Species 2010 report. The bar graph shows the number of macromoth species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, At Risk, May Be At Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 236 species occurring in Canada, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 9 as May Be at Risk, 20 as Sensitive, 155 as Secure, 29 as Undetermined, 7 as Exotic and 15 as Accidental. Of the 29 species occurring in the Yukon, 6 were ranked as Secure and 23 as Undetermined. Of the 29 species occurring in the Northwest Territories, 2 were ranked as Secure and 27 as Undetermined. Of the 2 species occurring in Nunavut, both were ranked as Undetermined. Of the 83 species occurring in British Columbia, 2 were ranked as May Be at Risk, 7 as Sensitive, 54 as Secure, 16 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 2 as Accidental. Of the 95 species occurring in Alberta, 1 was ranked as Extirpated, 1 as May Be at Risk, 5 as Sensitive, 72 as Secure, 12 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 2 as Accidental. Of the 95 species occurring in Saskatchewan, 5 were ranked as Sensitive, 58 as Secure, 25 as Undetermined, 1 as Exotic and 6 as Accidental. Of the 113 species occurring in Manitoba, 3 were ranked as May Be at Risk, 10 as Sensitive, 54 as Secure, 38 as Undetermined, 1 as Exotic and 7 as Accidental. Of the 170 species occurring in Ontario, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 7 as May Be at Risk, 16 as Sensitive, 117 as Secure, 14 as Undetermined, 3 as Exotic and 12 as Accidental. Of the 139 species occurring in Quebec, 19 were ranked as Sensitive, 88 as Secure, 21 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 9 as Accidental. Of the 85 species assessed in New Brunswick, 1 was ranked as Sensitive, 35 as Secure, 45 as Undetermined and 4 as Accidental. Of the 88 species occurring in Nova Scotia, 47 were ranked as Secure, 33 as Undetermined, 1 as Exotic and 7 as Accidental. Of the 50 species occurring in Prince Edward Island, 11 were ranked as Secure, 37 as Undetermined, 1 as Exotic and 1 as Accidental. Of the 36 species occurring in Newfoundland and Labrador, 11 were ranked as Secure, 24 as Undetermined and 1 as Exotic. There were no species listed as occurring in the oceanic regions.

| Canada rank | Number and percentage of species in each rank category |

|---|---|

| 0.2 Extinct | 0 (0%) |

| 0.1 Extirpated | 0 (0%) |

| 1 At Risk | 1 (1%) |

| 2 May Be At Risk | 9 (4%) |

| 3 Sensitive | 20 (8%) |

| 4 Secure | 155 (66%) |

| 5 Undetermined | 29 (12%) |

| 6 Not Assessed | 0 (0%) |

| 7 Exotic | 7 (3%) |

| 8 Accidental | 15 (6%) |

| Total | 236 (100%) |

Threats to Canadian macromoths

By far the greatest threat to moths is habitat destruction from agriculture, forestry, mining and other industrial activities, urbanization, and climate change. Other threats, of varying severity, are pesticide use, pollution, artificial lighting, and the spread of non-native species. The abundance and distribution of most moth species in North America is not well enough known to allow measurement of declines. However, threats can be anticipated for species particularly dependent on rare host plants, and for those associated with seriously threatened habitats such as sand dunes, the Garry Oak and semi-desert ecosystems of southern British Columbia, and the oak savanna and Carolinian ecosystems of southern Ontario.

The effect of insect collectors has sometimes been raised as a potential threat to moth populations, but there are no documented cases of moth species in Canada being adversely affected by such activities. In fact, the overwhelming opinion of informed environmentalists is that responsible collecting does far more benefit, in terms of providing information, than harm. The only way that collectors could possibly exert enough pressure to threaten an insect population would be if the population was already so small that it was in serious trouble from other factors.

Conclusion

Moths are a major component of biodiversity, so they form an important part of the natural environment. They have a huge capacity for reproduction, so most species are relatively resilient to population fluctuations. However, the vast majority of species are too poorly known to allow an assessment of how they are affected by human activities, and what might be done to mitigate the damage that humans cause. In most cases, the best that can be done at this time is to attempt to conserve their habitats and hope that most species living there will continue to thrive.

Further information

Barnes, W. and McDunnough, J. H. 1918. Illustrations of the North American species of the genus Catocala. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, New Series 3: 47 pp.

Cannings, R. A. and Scudder, G. G. E. 2007. Checklist: order Lepidoptera in British Columbia [PDF, 141 KB]. (Accessed November 10, 2009).

Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. 2003. The moths of Canada. (Accessed July 22, 2009).

Covell, C. V. Jr. 1984. A field guide to moths of eastern North America. Peterson Field Guide Series No. 30, Houghton Mifflin, Boston: 496 pp.

Ferguson, D. C. 1971. Bombycoidea: Saturniidae. Fasc. 20.2A. In The moths of America north of Mexico (R. B. Dominick, D. C. Ferguson, J. G. Franclemont, R. W. Hodges and E. G. Munroe, editors). Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Washington: 1-154.

Ferguson, D. C. 1972. Bombycoidea: Saturniidae. Fasc. 20.2B. In The moths of America north of Mexico (R. B. Dominick, D. C. Ferguson, J. G. Franclemont, R. W. Hodges and E. G. Munroe, editors). Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Washington: 155-277.

Handfield, L. 1999. Le guide des papillons du Québec, version scientifique. Broquet, Boucherville: 982 pp.

Handfield, L. 2002. Additions, corrections et radiations à la liste des Lépidoptères du Québec. Fabreries 27: 1-46.

Handfield, L., Landry, J.-F., Landry, B. and Lafontaine, J. D. 1997. Liste des Lépidoptères du Québec et du Labrador. Fabreries Supplement 7: 1-155.

Hodges, R. W. 1971. Sphingoidea; hawkmoths. Fasc. 21. In The moths of America north of Mexico (R. B. Dominick, D. C. Ferguson, J. G. Franclemont, R. W. Hodges and E. G. Munroe, editors). Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Washington: 158 pp.

Holland, W. J. 1903. The moth book. Doubleday Page, Garden City: 479 pp.

Lafontaine, J. D. and Schmidt, B. C. 2010. Annotated check list of the Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera) of North America north of Mexico. ZooKeys 40, Special Issue: 1-240.

Lafontaine, J. D. and Wood, D. M. 1997. Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) of the Yukon. In Insects of the Yukon (H. V. Danks and J. A. Downes, editors). Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods), Ottawa: 723-785.

Lepidopterists’ Society website. (Accessed July 22, 2009).

Marshall, S. A. 2006. Insects, their natural history and diversity, with a photographic guide to insects of eastern North America. Firefly Books, Richmond Hill: 718 pp.

Miller, J. C. and Hammond, P. C. 2003. Lepidoptera of the Pacific Northwest: caterpillars and adults. United States Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Morgantown: 324 pp.

Museums and Collections Services (2001–2008), University of Alberta, E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum, Virtual Museum. (Accessed July 22, 2009).

North American Moth Photographers Group. (Accessed July 22, 2009).

Pohl, G. R., Anweiler, G. G., Schmidt, B. C. and Kondla, N. G. 2010. Annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada. ZooKeys 38: 1-549.

Powell, J. A. and Opler, P. A. 2009. Moths of western North America. University of California, Berkeley: 383 pp.

Rockburn, E. W. and Lafontaine, J. D. 1976. The cutworm moths of Ontario and Quebec. Canada Dept. of Agriculture, Publication No. 1593: 164 pp.

Schmidt, B. C. and Opler, P. A. 2008. Revised checklist of the tiger moths of the continental United States and Canada. Zootaxa 1677: 1-23.

Stehr, F. W. (coordinator). 1987. Order Lepidoptera. In Immature insects, volume 1 (F. W. Stehr, editor). Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co., Dubuque: 288-596.

Wagner, D. L. 2005. Caterpillars of eastern North America: a guide to identification and natural history. Princeton University Press, Princeton: 512 pp.

Winter, W. D. 2000. Basic techniques for observing and studying moths and butterflies. The Lepidopterists’ Society Memoirs 5: 1-444.

References

COSEWIC. 2009. Canadian wildlife species at risk. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa: 96 pp.

Kristensen, N. P., Scoble, M. J. and Karsholt, O. 2007. Lepidoptera phylogeny and systematics: the state of inventorying moth and butterfly diversity. Zootaxa 1668: 699-747.

New, T. R. 2004. Moths (Insect: Lepidoptera) and conservation: background and perspective. Journal of Insect Conservation 8: 79-94.

Pohl, G. R. 2009. Why we kill bugs – the case for collecting insects. Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada (Terrestrial Arthropods) 28: 10-17.

Scoble, M. J. 1995. The Lepidoptera: form, function, and diversity. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 404 pp.

Tuskes, P. M., Tuttle, J. P. and Collins, M. M. 1996. The wild silkmoths of North America: a natural history of the Saturniidae of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, Ithaca: 250 pp.

Tuttle, J. P. 2007. The hawk moths of North America. Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Washington: 253 pp.

Young, M. 1997. The natural history of moths. T. & A. D. Poyser Ltd., London: 271 pp.