Wild species 2010: chapter 20

Insects: Butterflies

Lepidoptera - Order of insects that includes butterflies and moths. They can be distinguished from all other insects by their two pairs of scale-covered wings, which are often brightly coloured, particularly in many butterflies. Lepidopterans undergo complete metamorphosis: eggs are laid, from which larvae hatch, and a pupal stage follows, during which the final adult form takes shape. Butterflies are slender-bodied (mostly) diurnal insects.

Quick facts

- Butterflies represent one small branch of the lepidopterans, representing about 10% of known species (the others are moth species). Globally, there are about 18 000 butterfly species. Canada is home to 302 resident species of butterflies, although only five are endemic.

- When excluding species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental, the majority (82%) of butterflies in Canada have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of Secure, while 9% have Canada ranks of Sensitive, 7% have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk and 2% have Canada ranks of At Risk.

- One butterfly species, the Frosted Elfin (Callophrys irus), is extirpated from Canada.

- Monarchs (Danaus plexippus) migrate thousands of kilometres to avoid the Canadian winter.

- The Cabbage White (Pieris rapae) and European Skipper (Thymelicus lineola) are the two exotic butterflies in Canada.

Background

With their conspicuous daytime activity, bright colours, and jaunty flight patterns, butterflies tend to invoke the interest and sympathy of the general public. As a result, butterflies have become “flagship” invertebrates. That the Niagara Parks Butterfly Conservatory in Ontario attracted 850 000 visitors during its first full year of operation is one indicator of just how popular these insects have become.

Although butterflies number only about 10% of the order Lepidoptera – with moths comprising the other 90% – butterflies tend to be more eye-catching than moths, which are generally active during the night and are usually somewhat drab in colour. However, all butterflies begin life in a relatively understated form, as a tiny cryptic egg. A key to the survival of each generation lies in a female butterfly’s careful timing and choice of location for laying her eggs. Not only must she set the eggs on the right “host plant,” but she must also secure them to the right part of the plant, since not all plant parts will be equally edible to the caterpillar when it hatches from the egg. Upon hatching, the plant-chomping butterfly caterpillar grows by way of periodic moulting or shedding its skin. The last larval moulting results in the formation of a pupal case or chrysalis, rather than a larger caterpillar. This marks the start of a remarkable change, for, after a period of time, the pupal case splits open, and a fully formed adult winged butterfly emerges.

By undergoing total metamorphosis, butterfly larvae and adults are able to live radically different lifestyles in completely different environments – the former as a slow-crawling homebody with an insatiable appetite for vegetation, the latter as a flighty, wide-ranging sipper of nectar. Methodically munching through life, the larva exists in a tiny leafy world that contrasts greatly with that of the adult, which may be several hectares to several hundred square kilometres in extent. Indeed, Monarchs (Danaus plexippus) are known to undertake migratory flights of thousands of kilometres (adults tagged in Canada in the autumn have been subsequently recaptured in the winter forests of central Mexico). Most butterflies are relatively short-lived; entire cycle from egg to adult may be only a month or two, and adults may live only a week. Many species produce only one generation per year and fly only a few months out of the year.

Throughout most of Canada, where temperatures drop below freezing during part of the winter, at least one stage in a butterfly species’ life cycle must enter a dormant state termed “diapause” in order to resist freezing. Most species that spend the winter months in Canada do so as caterpillars. Others pass the winter as eggs (e.g., hairstreaks) or pupae (elfins and other Callophrys), while a few species, mainly tortoiseshells (Nymphalis) and angelwings (Polygonia), spend the winter as adults, hibernating in holes in trees, crevices in rock, or other shelters, like buildings.

Science now recognizes about 18 000 butterfly species worldwide, and this great variety is thought to relate to the broad diversity of plant species, since larvae typically use only a relatively narrow range of food plants. The North American butterflies of the genus Euphilotes, for instance, feed only on members of the knotweed family (Polygonaceae); the larvae eat the flowers and fruits, and the adults sip the nectar.

Status of knowledge

Butterflies are a relatively well studied insect group in Canada thanks in large part to the many professional and amateur specialists who have taken an interest in these unique insects. The considerable number of butterfly articles and books documenting Canadian species are complemented by numerous collections including the Lyman Entomological Museum (Macdonald Campus of McGill University in Montreal), the Royal Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History in Regina and the section on lepidopterans of the Canadian National Collection of insects in Ottawa. A recent publication by Peter W. Hall (2009) on behalf of NatureServe Canada, Sentinels on the Wing: The Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada, provides a comprehensive overview of the status of butterflies in Canada. This publication took into account the data and analyses from several organizations, including the general status results for butterflies developed by the National General Status Working Group and found in this report.

Richness and diversity in Canada

Within Canada, 302 butterfly species are described from coast to coast to coast, with the highest species richness found in the provinces from British Columbia through to Quebec. While many Canadian species are widespread, with the potential to be found in almost any province or territory (for example, Painted Lady - Vanessa cardui, Mourning Cloak - Nymphalis antiopa, Canadian Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio canadensis), a few species appear to be highly restricted in their distribution. For example, although further survey work may eventually describe a more extensive distribution for the species, Johansen’s Sulphur (Colias johanseni) has only been found on a single hillside near Bernard Harbour in Nunavut and in a coastal area near Coppermine. There are two species of Exotic butterflies in Canada. One of them, the European Skipper (Thymelicus lineola) arrived in Ontario in about 1910. Spreading south and west, this species has today become a major pest of Common Timothy (Phleum pratense). Still more “successful” is the now familiar Cabbage White (Pieris rapae), introduced at Quebec City in about 1860 and now found throughout most of North America.

Species spotlight - Maritime Ringlet

The Maritime Ringlet (Coenonympha nipisiquit) lives exclusively in salt marsh habitats in the Chaleur Bay region of Canada’s east coast. It has been found at only six sites. Population size and densities of the Maritime Ringlet are at their highest in habitats where there are large numbers of the host plant of the larva (salt meadow grass) and the source of nectar for the butterfly (sea lavender).

The average wingspan for males is 3.4 cm and 3.6 cm for females. An eyespot is present on about 33% of the males and is more common and better developed in females. Both males and females demonstrate ochre, grey and cream colour patterns. Males tend to darken as they age.

Flooding due to high tides and storm tides threaten all life stages of the Maritime Ringlet. Ice pushed onto their marshland habitats during winter storms can crush the overwintering larvae. The development and draining of marshland habitat are other significant threats. Researchers suspect there are likely other threats that have yet to be identified as there are numerous examples of ideal marshland habitats without populations of the butterfly.

The Maritime Ringlet has a Canada General Status Rank (Canada Rank) of At Risk and was designated Endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in April 2009.

Species spotlight - Monarch

The Monarch (Danaus plexippus) is likely the most recognized of all North American butterflies. Its bright orange wings which span upwards of 93 to 105 mm display a thick black border with two rows of white spots. Additional markings include two highly visible black patches on the hind wings which are found only on males.

The monarch is widely distributed across North America, from southern Canada southwards to Central America, and from the Pacific to the Atlantic coasts. Within Canada, the monarch has been recorded in all ten provinces and in the Northwest Territories. In general, two breeding populations of the Monarch are recognized: western and eastern, with the Rocky Mountains being the dividing point. Each of the two populations has a distinct migratory pattern. Those easts of the Rockies are overwintering in Central Mexico, while those wests of the Rockies are overwintering in California.

Monarchs are wide-ranging and powerful fliers. In the fall, they migrate thousands of kilometres, travelling from Canada to Mexico and California. In Canada, the migrations are best observed in southern Ontario, particularly in Point Pelee National Park and Presqu’île Provincial Park. Monarchs conserve energy during migration by riding currents of rising warm air and will reach altitudes of over one kilometre in order to take advantage of the prevailing winds.

Monarchs can thrive wherever milkweeds grow, as the larvae (caterpillars) feed exclusively on milkweed leaves. As long as there are healthy milkweed plants, Monarchs will put up with high levels of human disruption and have been known to breed along busy highways and city gardens.

Threats to Monarch populations include environmental conditions such as violent storms, loss of breeding habitat and contaminants such as herbicides (which kills both the milkweed needed by the caterpillars and the nectarproducing wildflowers needed by the adults). A very large threat is the loss of overwintering habitats in Mexico and California. The Monarch has a Canada General Status Rank (Canada Rank) of Sensitive and was designated Special Concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in November 2001.

Results of general status assessment

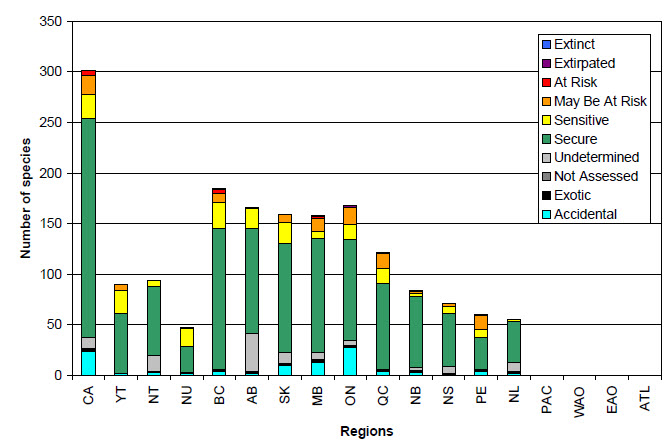

The report Wild Species 2010 marks the second national assessment for butterflies. On the 302 species of butterflies present in Canada, the majority have Canada ranks of Secure (217 species, 72%, figure 20 and table 27). Also, 24 species have Canada ranks of Sensitive (8%), 19 species have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk (6%) and four species are At Risk (2%). One butterfly species, the Frosted Elfin (Callophrys irus), is extirpated from Canada.

Eleven species of butterfly have Canada ranks of Undetermined or Not Assessed (3%). Two species are ranked as Exotic (1%). Finally, a higher number of species (24) have Canada ranks of Accidental (8%), due to the greater mobility of butterflies than some other taxonomic groups.

Long description for Figure 20

Figure 20 shows the results of the general status assessments for butterfly species in Canada in the Wild Species 2010 report. The bar graph shows the number of butterfly species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, At Risk, May Be At Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 302 species occurring in Canada, 1 was ranked as Extirpated, 4 as At Risk, 19 as May Be at Risk, 24 as Sensitive, 217 as Secure, 10 as Undetermined, 1 as Not Assessed, 2 as Exotic and 24 as Accidental. Of the 90 species occurring in the Yukon, 6 were ranked as May Be at Risk, 23 as Sensitive, 59 as Secure, and 2 as Accidental. Of the 94 species occurring in the Northwest Territories, 6 were ranked as Sensitive, 68 as Secure, 16 as Undetermined, 1 as Exotic and 3 as Accidental. Of the 47 species occurring in Nunavut, 1 was ranked as May Be at Risk, 17 as Sensitive, 26 as Secure, 1 as Exotic and 2 as Accidental. Of the 185 species occurring in British Columbia, 1 was ranked as Extirpated, 4 as At Risk, 9 as May Be at Risk, 26 as Sensitive, 139 as Secure, 2 as Exotic and 4 as Accidental. Of the 166 species occurring in Alberta, 1 was ranked as May Be at Risk, 20 as Sensitive, 104 as Secure, 37 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 2 as Accidental. Of the 159 species occurring in Saskatchewan, 8 were ranked as May Be at Risk, 21 as Sensitive, 107 as Secure, 11 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 10 as Accidental. Of the 158 species occurring in Manitoba, 1 was ranked as Extirpated, 2 as At Risk, 13 as May Be at Risk, 7 as Sensitive, 112 as Secure, 7 as Undetermined, 1 as Not Assessed, 2 as Exotic and 13 as Accidental. Of the 168 species assessed occurring in Ontario, 2 were ranked as Extirpated, 17 as May Be at Risk, 15 as Sensitive, 99 as Secure, 5 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 28 as Accidental. Of the 122 species occurring in Quebec, 1 was ranked as Extirpated, 15 as May Be at Risk, 15 as Sensitive, 85 as Secure, 1 as Not Assessed, 1 as Exotic and 4 as Accidental. Of the 84 species occurring in New Brunswick, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 2 as May Be at Risk, 3 as Sensitive, 70 as Secure, 3 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 3 as Accidental. Of the 71 species occurring in Nova Scotia, 3 were ranked as May Be at Risk, 7 as Sensitive, 52 as Secure, 7 as Undetermined and 2 as Exotic. Of the 60 species occurring in Prince Edward Island, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 14 as May Be at Risk, 8 as Sensitive, 31 as Secure, 2 as Exotic and 4 as Accidental. Of the 55 species occurring in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2 were ranked as Sensitive, 40 as Secure, 9 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 2 as Accidental. There were no species listed as occurring in the oceanic regions.

Comparison with previous Wild Species reports

In the report Wild Species 2000, all butterfly species received a Canada Rank of Not Assessed. In 2002, the National General Status Working Group produced updated general status ranks for all wild species of butterflies, including Canada ranks. In 2002, assessments were based on the taxonomy of Layberry et al. (1998). In this report, Wild Species 2010, the taxonomy is very similar to that used in 2002, except for a few changes to bring the species list into accordance with that proposed by Pelham (2008).

In general, the 2010 assessment resulted in fewer species that were identified as May Be At Risk or Sensitive and an increase in the number of species ranked as Secure (table 27). A total of 32 species had a change in their Canada rank since the last assessment. Among these changes, three species had an increased level of risk, 13 species had a reduced level of risk, three species were changed from or to the ranks Undetermined or Accidental, 11 species were added and two species were deleted. In most cases, this is not an indication of a biological change, but of an increase in knowledge or of a taxonomic change (table 28). A total of nine species were added since the assessment of 2000 updated in 2002.

| Canada rank | Years of the Wild Species reports 2000 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2005 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2010 |

Average change between reports |

Total change since first report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Extinct / Extirpated |

1 (0%) |

- | 1 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 1 At Risk | 2 (0%) |

- | 4 (2%) |

- | +2 species |

| 2 May Be At Risk | 23 (8%) |

- | 19 (6%) |

- | -4 species |

| 3 Sensitive | 31 (11%) |

- | 24 (8%) |

- | -7 species |

| 4 Secure | 201 (69%) |

- | 217 (72%) |

- | +16 species |

| 5 Undetermined | 11 (4%) |

- | 10 (3%) |

- | -1 species |

| 6 Not Assessed | 0 (0%) |

- | 1 (0%) |

- | +1 species |

| 7 Exotic | 2 (0%) |

- | 2 (1%) |

- | Stable |

| 8 Accidental | 22 (8%) |

- | 24 (8%) |

- | +2 species |

| Total | 293 (100%) | - | 302 (100%) |

- | +9 species |

| Scientific name | English name | 2000 Canada rank | 2010 Canada rank | Reason for change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocharis stella | Stella Orangetip | 4 | - | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Apodemia mormo | Mormon Metalmark | 3 | 1 | (C) Change due to new COSEWIC assessment (Endangered, May 2003). |

| Asterocampa celtis | Hackberry Emperor | 2 | 3 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Battus philenor | Pipevine Swallowtail | 5 | 8 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Callophrys gryneus | Juniper Hairstreak | 2 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Callophrys gryneus gryneus | Olive Juniper Hairstreak | - | 2 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Callophrys gryneus siva | Siva Juniper Hairstreak | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Celastrina lucia | Northern Spring Azure | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change; was previously included in Celastrina echo. |

| Celastrina serotina | Cherry Gall Azure | 5 | 4 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Colias occidentalis | Western Sulphur | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Erebia lafontainei | Reddish Alpine | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Erebia mackinleyensis | Mt. Mckinley Alpine | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Erebia pawloskii | Yellow Dotted Alpine | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Erebia youngi | Four-dotted Alpine | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Erora laeta | Early Hairstreak | 2 | 3 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Erynnis baptisiae | Wild Indigo Duskywing | 2 | 3 | (B) This species has been expanding its range. |

| Erynnis martialis | Mottled Duskywing | 5 | 4 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Euphydryas anicia | Anicia Checkerspot | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Euphydryas chalcedona | Variable Checkerspot | 4 | - | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Euphydryas colon colon | Colon Checkerspot | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Euphydryas colon paradoxa | Contrary Checkerspot | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Euphyes dion | Dion Skipper | 3 | 4 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Hesperia colorado | Western Branded Skipper | 2 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Lerema accius | Clouded Skipper | - | 8 | (I) New species in Canada. |

| Megathymus streckeri | Strecker’s Giant Skipper | - | 5 | (I) New species in Canada. |

| Oeneis philipi | Philip’s Arctic | 3 | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Plebejus idas | Northern Blue | - | 4 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Poanes zabulon | Zabulon | - | 5 | (I) New species in Canada, but unsure if a population exists or whether it is purely a vagrant. |

| Polites sabuleti | Sandhill Skipper | 3 | 2 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

| Satyrium caryaevora | Hickory Hairstreak | 3 | 4 | (I) Improved knowledge of the species. |

| Satyrium semiluna | Sooty Hairstreak | 2 | 1 | (C) Change due to new COSEWIC assessment (Endangered, April 2006). |

| Speyeria egleis | Great Basin Fritillary | - | 6 | (T) Taxonomic change. |

Threats to Canadian butterflies

Most experts agree that the modification and elimination of suitable habitat pose the greatest threat to native butterflies across the country. Butterflies associated with highly jeopardized natural communities, like the pine oak barrens and tallgrass prairies of Ontario and the Garry oak woodlands and the Okanagan and Silmilkameen valleys of British Columbia, are particularly susceptible.

Conclusion

Butterflies are flagship species and play an important role in the ecosystems. However, there is a need to better understand the threats that these species are facing. Since the 2002 updates to the Wild Species 2000 ranks for butterflies, two species were assigned a Canada Rank of At Risk (the result of COSEWIC assessments). The 2010 report presented the results of the second assessment of Canada ranks for butterflies by the National General Status Working Group, and this process will hopefully help to gather more information on the ecology of these species.

Further information

Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. 2006. Butterflies of Canada. (Accessed February 11, 2010).

Hall, P. W. 2009. Sentinels on the Wing: The status and conservation of butterflies in Canada. NatureServe Canada, Ottawa, Ontario: 68 pp.

Hinterland Who’s Who. 2003. Insect fact sheets: Monarch. (Accessed February 25, 2010).

Opler, P. A., Lotts, K. and Naberhaus, T. 2010. Butterflies and moths of North America. (Accessed February 26, 2010).

References

COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Maritime Ringlet (coenonympha nipisiquit) in Canada [PDF, 411 KB]. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. (Accessed February 26, 2010).

Environment Canada. 2010. Species at Risk Public Registry. Species Profile: Monarch. (Accessed February 25, 2010).

Layberry, R. A., Hall, P. W. and Lafontaine, J. D. 1989. The butterflies of Canada, University of Toronto Press.

Parks Canada. 2009. Point Pelee National Park of Canada: Monarch migration. (Accessed February 26, 2010).

Pelham, J. P. 2008. A catalogue of the butterflies of the United States and Canada. The Lepidoptera Research Foundation Inc: 672 pp.