Wild species 2010: chapter 21

Crustaceans

There are an estimated number of over 3000 species of crustaceans present in Canada. In this report, only one group of crustaceans, the crayfishes, are assessed.

Crayfishes

Astacoidea - Freshwater crayfishes are a globally common and diverse crustacean group, occurring naturally on all continents except for Africa and Antarctica

Quick facts

- There are more than 540 species of crayfishes worldwide, of which 11 are found in Canada.

- When excluding species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental, the majority (78%) of crayfishes in Canada have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of Secure, while 22% have Canada ranks of Sensitive.

- Two crayfish species have Canada ranks of Exotic, the Rusty Crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) and the Obscure Crayfish (Orconectes obscurus). Both were introduced into Ontario as fish bait and now also occur in Quebec. The Rusty Crayfish has spread rapidly in Ontario and has eliminated native crayfishes from many lakes and rivers. Little is known about the Obscure Crayfish in Canada.

- One-third of native crayfish species in the United States are Endangered or Threatened, according to the American Fisheries Society Endangered Species Committee.

Background

Crayfishes belong to the subphylum Crustacea, together with the crabs, lobsters and shrimps. All crayfishes have a jointed exoskeleton and breathe with gills. Canada’s crayfishes are found in an amazing variety of freshwater habitats including wetlands, wet meadows, stagnant water, ponds, ditches, streams, rivers and lakes. Although all of Canada’s crayfishes are also found in the United States, some Canadian populations show unique life history and ecology patterns compared to more southerly populations. There are two families of crayfishes in Canada, Astacidae and Cambaridae. Astacidae is represented by one species, the Signal Crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus), found in British Columbia. The other 10 species of crayfishes found in Canada all belong to the family Cambaridae.

The crayfishes’ most noticeable feature is the large claws, found on the first of their five pairs of legs. These large claws, also called giant chelipeds, are used in feeding, mating, defence and burrowing. The other four pairs of legs are used for walking and searching for food. Although crayfishes usually walk slowly across the bottom of streams, rivers and lakes, they can escape from predators by flicking their strong tail and zooming backwards out of danger. On the front of their head, crayfishes have a pair of compound eyes, on short, flexible stalks. Crayfishes cannot turn their heads around, but the flexible stalks allow them to see in different directions. Crayfishes also have a pair of long antennae, which are used to sense food and chemicals in the water.

Crayfishes typically live for only a few years, so they must reproduce rapidly and at a high volume to maintain their populations. Most species mate during the fall or early spring. During mating, the male crayfish deposits his sperm in a sperm receptacle on the underside of the female. The female stores the sperm until she is ready to fertilize her eggs in the spring. When she is ready to lay her eggs, the female creates a pocket by curling her tail underneath her abdomen. This pocket is filled with a sticky substance, called glair, which will hold the eggs in place. As eggs are laid, they pass through the sperm receptacle and then down into the glair, where they remain until they are ready to hatch. Once hatched, the young crayfish remain attached to their mother for several weeks, until they have moulted twice. Finally, the young crayfish leave the mother to fend for themselves. In some species, crayfishes are ready to mate within a few months of hatching, whereas other species can take several years to mature.

Crayfishes can be divided into two major types: open-water species and burrowers. Open-water crayfishes rarely or never leave the water and are mainly active at night. During the day, they hide in crevices under rocks or other cover, to escape predation. Burrowers are less dependent on aquatic habitats than open-water species. They live in ditches, wet meadows and other areas where the water table is not far belowground. Burrowers dig tunnels under the ground and live in the moist soil, probably only emerging to hunt for food and to mate. Like other crayfishes, burrowers breathe with gills, but they are able to extract oxygen from moist air as well as from water.

Crayfishes have a diverse diet of aquatic and terrestrial vegetation, dead and decaying plant and animal material, and small aquatic invertebrates. By eating dead and decaying plant and animal matter, crayfishes release trapped energy and nutrients back into the food chain, where they are available to crayfish predators. This makes crayfishes an important link in aquatic food webs. Crayfishes are eaten by a wide range of animals including invertebrates, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. They can also be an important food item for sport fishes, such as sunfishes and basses (family Centrarchidae).

Status of knowledge

Crayfishes are often used as study animals in laboratory experiments and classrooms because they are easy to obtain and maintain, so their basic biology is fairly well known. However, much less is known about crayfishes in the wild. In Ontario, several life history studies have been conducted on native and exotic species, but life history has not been studied extensively in other areas of the country. Similarly, their distribution is fairly well known in Ontario but less well known in the rest of the country. In particular, distributions at the northern edges of crayfishes’ ranges and in areas where exotic species have been introduced need further research. Recent studies are starting to address these information gaps. For example, a recent study in British Columbia showed that the distribution of the Signal Crayfish is much larger than previously thought.

One of the leading concerns of crayfish biologists is the impact of introduced crayfishes on native communities. There are two species of crayfish that have Canada ranks of Exotic; the Rusty Crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) and the Obscure Crayfish (Orconectes obscurus), both of which were probably introduced to Canada as fish bait. The Rusty Crayfish has spread rapidly in Ontario and Quebec. It is a large, aggressive crayfish that can exclude native crayfishes such as the Northern Clearwater Crayfish (Orconectes propinquus) and the Virile Crayfish (Orconectes virilis) through aggressive interactions and higher reproduction rates. The Rusty Crayfish can also reduce the diversity and abundance of aquatic plants and invertebrates, compete with fish for food, and reduce fish reproduction by eating fish eggs. The Obscure Crayfish was also introduced into Ontario. Little is known about the Obscure Crayfish in Canada, but it is thought to exclude native crayfishes through competition. It is also believed to hybridize with Northern Clearwater Crayfish.

Crayfishes are used as biological indicators for several types of pollution. For example, in British Columbia, Signal Crayfish kept in cages at locations downstream of agricultural and residential land use areas showed increased levels of contaminant accumulation in their tissues. In Ontario, crayfishes have been used to study heavy metal contamination and acidification of lakes and streams.

Richness and diversity in Canada

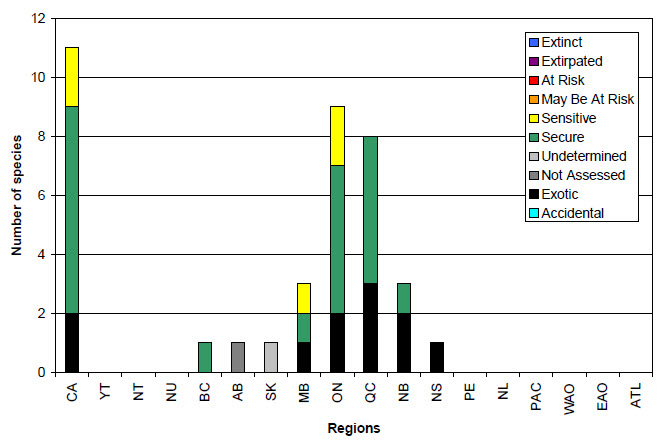

Ontario (nine species) and Quebec (eight species) have the highest species richness of crayfishes in Canada (figure 21). Of the 11 Canadian crayfishes, the only two that do not occur in Ontario are the Spineycheek Crayfish (Orconectes limosus), found in Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and the Signal Crayfish found in British Columbia. Two provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island) as well as the three territories have no crayfishes.

Species spotlight - Chimney Crayfish

The Chimney or Digger Crayfish, Fallicambarus fodiens, (hereafter Chimney Crayfish) is one of two burrowing species found in Ontario. Chimney Crayfish live in wetlands, creek beds, ditches and in dry ground far from permanent surface water. To survive in these habitats, Chimney Crayfish dig burrows into the ground. Burrows usually consist of one to three entrance tunnels connecting with a vertical shaft. The shaft ends below the water table in a flooded chamber where the crayfish spends much of its day. The burrow entrance is marked by a pile (or chimney) of mud pellets, collected during excavation. Chimney Crayfish are thought to be omnivorous; they probably eat any vegetation or invertebrates encountered in their burrows.

Within Canada, Chimney Crayfish are found only in southern Ontario. Recent surveys found small populations as far north as south-eastern Georgian Bay and as far east as the northeast shore of Lake Scugog. This species seems to prefer to build its burrows in clay soil, so the thin soil and hard rock of the Canadian Shield may prevent it from expanding its range northwards. Although the Chimney Crayfish has a wide distribution within southern Ontario, it is never locally common and often lives in small habitat patches within a sea of agriculture or urban development. The highly developed nature of this region means that habitat loss is a major threat to the Chimney Crayfish.

Little is known about the life history of the Chimney Crayfish in Canada, but it is thought to breed in May and June and live for three to four years. Although further study into the life history of the Chimney Crayfish is needed, it has been suggested that Canadian populations have unique life history patterns, compared to more southerly populations.

Although the Chimney Crayfish is never locally common and is negatively impacted by habitat loss, there are many occurrences of this species in southern Ontario. Therefore Chimney Crayfish has a Canada General Status Rank (Canada rank) of Sensitive.

Species spotlight - Virile Crayfish

The Virile Crayfish, Orconectes virilis, is an open-water crayfish found from Alberta, east to New Brunswick, and is the most widely distributed crayfish in Canada. Although it is frequently found in rivers or streams with a rocky substrate, it is also found on mud or silt substrates, and in lakes. The Virile Crayfish spends the day sheltering in a shallow excavation under a rock. At night, it ventures out to feed on aquatic plants, algae and aquatic invertebrates.

The Virile Crayfish is widespread and common in most of its range. However, in Ontario and Quebec, the Virile Crayfish faces competition from the exotic Rusty Crayfish. The Rusty Crayfish, which is native to Ohio, Kentucky, Michigan and Indiana, has eliminated the Virile Crayfish from many aquatic systems in Ontario due to its superior competitive abilities and faster reproductive cycle. However, the Virile Crayfish is not likely to face immediate widespread population declines, as it still has many stable populations in areas where the Rusty Crayfish has not yet been introduced.

Several studies in Ontario have shown declining populations of Virile Crayfishes in lakes on the Canadian Shield. These population declines have been linked to acid rain, since increased acidity of the water can lead to reduced reproductive success in Virile Crayfishes. The situation is quite different in the western part of the Virile Crayfish’s range. In Alberta, the Virile Crayfish is native to the Beaver River drainage, but has been introduced into other Alberta rivers, probably as fish bait. The rivers into which it has been introduced have no native crayfishes, so the Virile Crayfish faces little competition and has the potential to spread rapidly. Experiments have shown that the Virile Crayfish could alter aquatic systems in Alberta by reducing the abundance of native aquatic plants and invertebrates.

Although the Virile Crayfish is facing population declines and local extirpation in some parts of its range, it is a common, widespread species, with many occurrences in Canada. Therefore it has a Canada rank of Secure.

Results of general status assessment

Seven species (64%) of crayfishes have Canada ranks of Secure and two species (18%) have Canada ranks of Sensitive (figure 21 and table 29). In addition, two species (18%) of crayfishes have Canada ranks of Exotic.

Long description for Figure 21

Figure 21 shows the results of the general status assessments for crayfish species in Canada in the Wild Species 2010 report. The bar graph showing the number of crayfish species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, At Risk, May Be At Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 11 species occurring in Canada, 2 were ranked as Sensitive, 7 as Secure and 2 as Exotic. Only 1 species was listed as occurring in British Columbia and was ranked as Secure. Only 1 species was listed as occurring in Alberta and was ranked as Not Assessed. Only 1 species was listed as occurring in Saskatchewan and was ranked as Undetermined. Of the 3 species occurring in Manitoba, 1 was ranked as Sensitive, 1 as Secure and 1 as Exotic. Of the 9 species occurring in Ontario, 2 were ranked as Sensitive, 5 as Secure and 2 as Exotic. Of the 8 species occurring in Quebec, 5 were ranked as Secure and 3 as Exotic. Of the 3 species occurring in New Brunswick, 1 was ranked as Secure and 2 as Exotic. Only 1 species was listed as occurring in Nova Scotia and was ranked as Exotic. There were no species listed as occurring in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the oceanic regions.

Comparison with previous Wild Species reports

Even though some provincial ranks changed, the Canada ranks of crayfish species have not changed since the last assessment in 2005 (table 29).

| Canada rank | Years of the Wild Species reports 2000 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2005 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2010 |

Average change between reports | Total change since first report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Extinct / Extirpated | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 1 At Risk | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 2 May Be At Risk | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 3 Sensitive | - | 2 (18%) |

2 (18%) |

- | Stable |

| 4 Secure | - | 7 (64%) |

7 (64%) |

- | Stable |

| 5 Undetermined | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 6 Not Assessed | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| 7 Exotic | - | 2 (18%) |

2 (18%) |

- | Stable |

| 8 Accidental | - | 0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

- | Stable |

| Total | - | 11 (100%) |

11 (100%) |

- | Stable |

Threats to Canadian crayfishes

The two major threats to Canadian crayfishes are competition from exotic crayfishes and habitat loss. Exotic crayfishes have already caused local extirpation of native crayfishes in Ontario, but no native crayfishes are currently in danger of extirpation at a provincial or national level, due to the widespread distribution of the affected species. Habitat destruction due to damming and channelling, wetland loss, siltation and development of riparian habitat can all impact crayfishes. Habitat loss may have a greater impact on burrowing species, which occur in low densities in isolated habitat patches. In addition, air and water pollution, including acidification of lakes and rivers due to acid rain, can all impact crayfishes.

Conclusion

There remains much to be learned about Canadian crayfishes, including the limits of crayfish distribution, life histories in all regions of the country, and the impacts of introduced crayfishes on aquatic communities. Monitoring of crayfish populations, especially to document the spread of Exotic species, will be important in determining future status changes. Canada’s crayfishes play an integral role in the freshwater systems in which they occur naturally and have the potential to alter systems into which they are introduced. Increasing our knowledge of crayfishes will help preserve healthy freshwater ecosystems throughout southern Canada.

Further information

Crandall, K. A. and Fetzner, J. W. 2006. Crayfish home page. (Accessed February 16, 2010).

Crandall, K. A. and Fetzner, J. W. Jr. 1995. Astacidea, freshwater crayfishes. (Accessed February 16, 2010).

Crocker, D. W. and Barr, D. W. 1968. Handbook of the crayfishes of Ontario. Life Sciences Miscellaneous Publications, Royal Ontario Museum, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario: 158 pp.

Fetzner, J. W. Jr. 2005. Global crayfish resources. (Accessed February 16, 2010).

Hamr, P. 1998. Conservation status of Canadian freshwater crayfishes. World Wildlife Fund Canada and the Canadian Nature Federation, Toronto: 87 pp.

Hamr, P. 2003. Conservation status of burrowing crayfishes in Canada. Upper Canada College, Toronto: 35 pp.

Royal, D., Thoma., R., Lukhaup, C., Aniceto, E., De Almeida, A. O., Doran, N., McCullogh, C. and Royal, J. Y. 2005. Crayfish world. (Accessed February 16, 2010).

References

Berrill, M. 1978. Distribution and ecology of crayfish in the Kawartha Lakes region of southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 56: 166-177.

Bondar, C. A., Zhang, Y., Richardson, J. S. and Jesson, D. 2005. The conservation status of the freshwater crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus, in British Columbia. British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. Fisheries Management Report No. 117.

Butler, R. S., DiStefano, R. J. and Schuster, G. A. 2003. Crayfish: An overlooked fauna. Endangered Species Bulletin XXVIII: 10-12.

Garvey, J. E., Stein, R. A. and Thomas, H. M. 1994. Assessing how fish predation and interspecific prey competition influence a crayfish assemblage. Ecology 75: 532-547.

Hamr, P. and Berrill, M. 1985. The life histories of north-temperate populations of the crayfish Cambarus robustus and Cambarus bartoni. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63: 2313-2322.

Lodge, D. M., Taylor, C. A., Holdich, D. M. and Skurdal, J. 2000. Nonindigenous crayfishes threaten North American freshwater biodiversity: lessons from Europe. Fisheries 25: 7-20.

Taylor, C. A., Warren, M. L., Fitzpatrick, J. F., Hobbs III, H. H., Jezerinac, R. F., Pflieger, W. L. and Robinson, H. W. 1996. Conservation status of crayfishes of the United States and Canada. Fisheries 21: 25-30.

Williams, D. D., Williams, N. E. and Hynes, H. B. N. 1974. Observations on the life history and burrow construction of the crayfish Cambarus fodiens (Cottle) in a temporary stream in southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 52: 365-370.