Wild species 2010: chapter 24

Birds

Aves - Class of feathered, warm-blooded vertebrates, having a beak and wings, laying eggs and usually able to fly.

Quick facts

- There are approximately 10 000 species of birds worldwide, of which 664 have been found in Canada.

- When excluding species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental, the majority (78%) of birds in Canada have Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of Secure, while 11% have Canada ranks of Sensitive, 8% have Canada ranks of At Risk and 3% have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk.

- Three species of birds that were present in Canada are now extinct from the World, the Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius), the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) and the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), and one species is extirpated from Canada, the Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido).

- Each spring, up to 3 billion birds of more than 300 species migrate north to breed in Canada’s boreal forest!

- Arctic Terns (Sterna paradisaea) make an annual migration from their breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic to their Antarctic wintering grounds, a round-trip of approximately 35 000 km.

- Christmas Bird Counts have been used to survey North American birds since 1900. During the 2008-2009 count, 11 059 Canadian volunteers counted 2.84 million birds of 283 species.

- Since 2000, a total of 25 new bird species have been added to the national list. Most of these species have Canada ranks of Accidental, and many have been recorded from only one province or territory.

Background

From the delicate Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) to the regal Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodius), birds are arguably the best known and most popular group of species covered in this report. Birds show incredible diversity of shape, size, behaviour and ecology, but are united by their adaptations for powered flight. These adaptations have shaped every aspect of the biology of birds, from the modification of forelimbs into wings, to the development of a highly efficient one-way breathing system.

Feathers are as unique to birds as hair is to mammals. Whether feathers originally evolved for use in flight, or to aid with insulating or cooling of the body (thermoregulation), is uncertain. However, in modern birds, feathers are used for a variety of purposes including the creation of a streamlined body shape, flight, insulation, and for display. In addition, many bird species have feathers that are specially adapted for particular purposes, such as producing sound during display flights (e.g. Wilson’s Snipe, Gallinago delicata) and improving hearing. Owls, like the Barn Owl (Tyto alba), have a facial disc of stiff, dense feathers forming a concave surface that channels sound into their ears, enhancing their sensitive hearing and allowing them to accurately locate their prey by sound alone.

Flight gives birds the flexibility of moving over large distances to take advantage of different habitats and resources. Canadian winters are harsh and food is often in short supply, particularly for insect-eating birds, so every fall billions of birds migrate south to take advantage of warmer weather and more abundant food supplies. Most bird species migrating from Canada travel south to the United States, the Caribbean and South America while a very few make their way to Europe, Africa or Asia. Some seabird species show seasonal movements that reflect oceanic rather than continental patterns. Migrant species are diverse, ranging from tiny songbirds, such as the Blackpoll Warbler (Dendroica striata), to waterfowl like the Snow Goose (Chen caerulescens), seabirds like the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) and raptors like the Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni). The most spectacular group of migrants is probably the shorebirds. Some shorebirds, such as the Red Knot (Calidris canutus) regularly breed in the Arctic and migrate as far south as the southern tip of South America! Non-migratory birds, or birds that only move short distances, have adaptations to enable them to survive the winter. For instance, the Gray Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) and the Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) both store food to help avoid shortages. The White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lagopus leucura), found in the Arctic, buries itself under the snow to keep warm at night and during snow storms.

Birds need a large, consistent food supply to fuel their warm-blooded metabolism. They use a wide variety of foods to meet this demand, including seeds, fruit, nectar, tree sap, insects, small reptiles, mammals and other birds. Because the forelimbs of birds are highly adapted to flight, their bills and talons are very important in feeding. The shape of a bird’s bill can tell you much about its diet, from the large sturdy bill of seed-eating finches, to the hooked bill of hawks and owls. Even birds’ tongues vary depending on what they eat. For example, the tongue of a Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus) is sticky and very long – more than 12 cm from base to tip – to allow it to reach into anthills to extract the ants on which it feeds.

For centuries people have been inspired by the beautiful songs of birds like the Winter Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) and the Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus). Male birds typically use song both to attract a mate (courtship) and to defend their territory from other males. Although song is one of the most important ways that birds attract a mate, it is by no means the only one. For example, many species of duck use visual displays to attract a mate. Studies of Long-tailed Ducks (Clangula hyemalis) have identified at least a dozen distinct displays performed by courting males, including head-shaking, neck-stretching and wing-flapping. Duck courtship displays are usually confined to the water, but some species display in the air. Many people are familiar with the display flight of the American Woodcock (Scolopax minor) at dawn and dusk in early spring. It flies high up into the air in a vertical spiral, while making a twittering sound with its wing feathers. Back on the ground, a repetitive, nasal “peent” sound signals its presence as it prepares for its flight. Other methods of courtship include nest building (e.g. Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris) and providing food (e.g. Osprey, Pandion haliaetus). Because courtship is fundamental to the breeding biology of birds, it has been well studied, leading to many new theories and discoveries, particularly in the areas of evolution and sexual selection (selection based on characteristics such as song, colouration and displays meant especially to attract mates.)

Status of knowledge

Birds are perhaps the best studied group covered in this report largely because they are relatively easy to observe. They are economically important, and popular with scientists, naturalists and the public. In general, the basic biology and physiology of birds are well understood, and the distribution of birds in Canada is probably better understood than for any other group of wildlife in the country. Regular, long-term surveys, such as the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), the Maritime Shorebird Survey and the National Harvest Survey of waterfowl, allow population size and trends to be estimated for a range of bird species. To complement surveys that monitor population sizes and trends, other regional and nationwide surveys, such as nest record schemes and the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program, provide information on the life history and reproductive success of many different bird species.

Although huge progress has been made in studying bird distribution, populations and ecology, some groups of birds have proven difficult to sample adequately. In particular, birds breeding in northern Canada are not well surveyed by important schemes such as the BBS, due to the vast area and difficulty in accessing much of northern Canada. Other programs, such as the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) and the Canadian Migration Monitoring Network, which survey birds in the winter and during migration respectively, help to fill this gap. However, more work is needed to understand the distribution, population sizes and trends of northern birds. Scientists are currently developing new methods to monitor bird populations not well covered by the traditional surveys. In addition, species such as the crossbills (genus Loxia) and the redpolls (genus Acanthis), whose breeding density and patterns of movement are governed by cycles in their food sources, are difficult to survey and monitor. Ongoing work in the field of statistical analysis, efforts to standardize survey methods, and development of Internet tools allowing members of the public to enter data, means that scientists are increasingly able to make use of data collected through a variety of programs relying on volunteers.

Richness and diversity in Canada

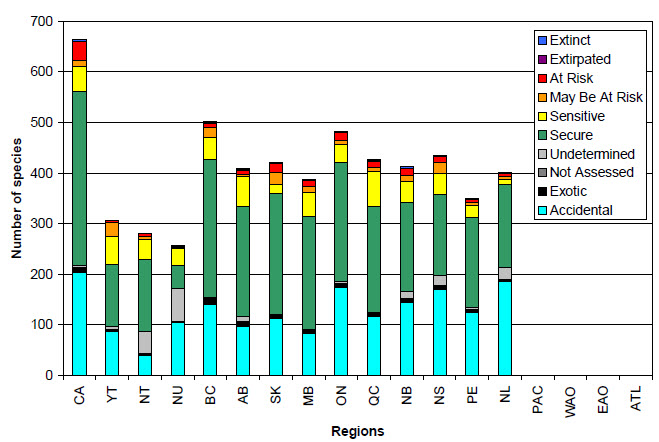

A total of 664 bird species have been found in Canada. Bird species richness is highest in western and central Canada, peaking in British Columbia (502 species) and Ontario (483 species). Species richness is lower in the three northern territories than in the provinces, but the territories provide core breeding habitat for a number of bird species, particularly shorebirds. Compared to the other species groups covered in this report, the proportion of bird species ranked Accidental is high across the country, reflecting the mobile and migratory nature of many species (figure 24). So-called accidental occurrences can result from bad weather conditions that blow migrating birds off-course, or when juvenile birds stray many kilometers from their normal migration routes. The percentage of species ranked Accidental peaks in eastern Canada (35-45%), which receives accidental species from the Americas, Europe and Africa, as well as wandering seabirds.

Species spotlight - Atlantic Puffin

The Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica) is a pigeon-sized seabird easily recognized by its striking black and white plumage and large, colourful bill. As its name suggests, it is found in the northern Atlantic Ocean where it breeds on the east coast of Canada, the northeast coast of the United States and the coasts of Greenland, Europe and Russia. Atlantic Puffins typically breed in dense colonies on grassy slopes or cliff-tops of small islands. Colonies consist of many pairs of puffins, each with its own nesting burrow, which they defend vigorously. Adult puffins dig the burrows with their large bills, strong feet and sharp claws. Burrows may be reused by the same pair for many years. The female lays one egg at the back of the tunnel, then both parents take turns incubating the egg and, eventually, feeding the chick. Once the young birds are independent, Atlantic Puffins leave the land and spend the rest of the year feeding at sea. Atlantic Puffins typically breed for the first time when they are five years old and can live up to about 25 years.

Atlantic Puffins feed on small marine fishes which they pursue under water. Using their short wings as paddles, they “fly” through the water, capturing fish from large schools of Capelin (Mallotus villosus), herring (family Clupeidae) or other small species. In flight, puffins flap their wings extremely quickly (300-400 times per minute!) Wing size for this bird and other diving bird species is a compromise between flight, for which large wings are better, and swimming, for which small wings are better.

Like other seabirds, the Atlantic Puffin has a low rate of reproduction, although long-lived adults may reproduce many times during their lives. In the past, puffins were harvested for food and for their feathers, leading to population declines in North America and Europe, but this pressure has now largely been removed. Today, Atlantic Puffins and other seabirds are vulnerable to pollution (including oil spills and other environmental contamination), reduced food supply, drowning in fishing nets, and predation and competition from gulls. Atlantic Puffins are difficult to monitor, because their breeding grounds are remote and because they nest underground. Atlantic Puffins have a Canada General Status Rank (Canada rank) of Secure.

Species spotlight - Western Screech-Owl

The Western Screech-Owl (Megascops kennicottii) is a small, nocturnal owl with large eyes and ear tufts. It has a diverse diet of insects and small mammals and has even been observed catching and eating crayfish and bats! Like many other owls, the Western Screech-Owl has numerous adaptations to nocturnal hunting. Their excellent eyesight and hearing help them to detect their prey, while the leading edge of their flight feathers is serrated, allowing them to fly silently, so that prey are not aware of their approach. Also, their strong, sharp talons are adapted for grasping and carrying heavy food items. Owls swallow their prey whole, but they can’t digest the bones, fur or feathers. These are separated from the meat, and coughed back up as a pellet. Scientists study the distribution and contents of owl pellets to learn what habitats the owls are using and what they are eating.

Western Screech-Owls do not migrate. Instead they spend the whole year with their mate defending their territory. Western Screech-Owls nest in natural tree cavities, old woodpecker holes or nest-boxes. Males and females share nesting duties; females incubate the eggs and guard the nest, while males bring food for both the female and the young. Like many species of owl, young Western Screech-Owls leave the nest before they can fly so the parents must spend several more weeks feeding them before they are independent. Western Screech-Owls nest in deciduous and mixed-wood forests reaching their highest densities close to rivers or other water sources.

Within Canada, Western Screech-Owls are found primarily in British Columbia, although a few records exist in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The two subspecies of the Western Screech-Owl known to occur in Canada were both were assessed by COSEWIC in 2002. The macfarlanei subspecies (Megascops kennicotti macfarlanei) was assessed as Endangered, and the kennicottii subspecies (Megascops kennicotti kennicottii) was assessed as Special Concern. Western Screech-Owl has a Canada rank of Sensitive, which has changed from Secure in 2000, due to the 2002 COSEWIC reports.

Species spotlight - Red-headed Woodpecker

The Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) is a medium-sized, colourful woodpecker that lives in southeastern Canada, south-central Canada and the eastern United States. This noisy and intriguing species has a varied diet of insects and plant matter including seeds, nuts, corn, berries and fruit. One of the Red-headed Woodpecker’s favourite methods for catching insects is known as “fly-catching” (flying out from a perch to capture insects in mid-air), behaviour usually considered more typical of flycatchers, like the Eastern Kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), than woodpeckers! Red-headed Woodpeckers are one of the few species of woodpecker known to regularly store food, and the only woodpecker species known to cover stored food with wood or bark.

Red-headed Woodpeckers typically nest in open, deciduous forest, with trees widely spaced and plenty of dead trees (snags) for nesting and feeding. Red-headed Woodpeckers are known as primary cavity nesters because they excavate their own nest hole, usually in dead wood. Once they have finished with their cavity, it is often reused by other animals such as squirrels or American Kestrels (Falco sparverius). Red-headed Woodpeckers defend their nest vigorously against members of their own species and other possible competitors like Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) and Red-bellied Woodpeckers (Melanerpes carolinus). In the fall, most Red-headed Woodpeckers migrate south to spend the winter in the United States. Their wintering areas are not fixed, but vary from year to year, depending mainly on the availability of their winter foods (primarily beechnuts and acorns).

Red-headed Woodpeckers have undergone large fluctuations in population size since European settlers first arrived in North America. The small-scale clearing of forests by early settlers created forest edges and clearings, which provided good breeding habitat for Red-headed Woodpeckers. However, as huge tracts of forest in eastern North America were logged, their winter food supply declined, as did the Red-headed Woodpecker. More recently, large-scale die-offs of Elm trees (genus Ulmus) and American Chestnut trees (Castanea dentata) in the middle of the last century left behind numerous large, decaying trees. This probably benefited Red-headed Woodpeckers by providing suitable nesting and feeding sites. Since 1966, Red-headed Woodpecker populations have been tracked across North America by the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). Analysis of BBS trends suggests that Red-headed Woodpeckers have been undergoing significant declines across North America since the beginning of the survey, at a rate of about -2.7% per year. This suggests that the number of Red-headed Woodpeckers in North America may have declined by about 65% since 1966! The primary reason for population declines is thought to be loss of breeding habitat, due to removal of large dead trees.

The Red-headed Woodpecker was first assessed by COSEWIC in 1996 and was designated as Special Concern. This was changed to Threatened in 2007 due to a combination of new information about population size and the high rate of population decline.

Results of general status assessment

More detailed information is available about bird populations than for any other groups of species covered in this report. Anyone looking at the general status ranks for birds should keep in mind that these are by definition highly generalized. General status ranks should be considered together with the findings of the various bird population monitoring programs mentioned earlier and other relevant research. BBS data, in particular, show cases where bird species are undergoing population declines over various time periods, despite appearing to be plentiful or secure in most or all provinces or territories. Population trends based on BBS data for Canadian species can be viewed on the Canadian Bird Trends website.

For all groups covered in this report, national ranks are generally assigned based on the regional rank with the lowest level of risk. For example if the provincial and territorial ranks for a species are a mixture of Sensitive and Secure, the default Canada rank is usually Secure. However, for birds, this is not always the case. With the better knowledge we have on these species, the provincial and territorial ranks can be weighted according to the distribution of the birds when determining the Canada rank. Special considerations in regards to the breeding range of the species in Canada are also taken into account. Therefore, many of the Canada rank changes for birds are due primarily to the different procedures followed in 2000, 2005 and 2010, and are classified as procedural changes. These changes help to ensure that Canada ranks are comparable both within and among species groups.

The majority of Canada’s bird species are migratory, using different habitats at different latitudes throughout the year. This exposes them to an array of threats at different times during their life cycle. When Canada ranks were created for migratory birds, particular attention was paid to each species’ status on its breeding grounds. For example, within Canada, the Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres) breeds primarily on the tundra in northern Nunavut. There it is ranked Sensitive due to population declines. However, the species is a common migrant in suitable habitat in parts of southern Canada, and is ranked Secure in every province. Nevertheless, Ruddy Turnstone received a Canada rank of Sensitive due to concerns within its breeding range. This kind of exception was applied to approximately 16 bird species and is documented in the comments section of the general status database.

Just over half of the bird species found in Canada are ranked as Secure (52%, 344 species; figure 24 and table 34). However, nearly a third of bird species have Canada ranks of Accidental (30%, 203 species), the highest percentage of Accidental species of any group covered in this report. In addition, 7% of bird species have Canada ranks of Sensitive (49 species), 6% have Canada ranks of At Risk (37 species), 2% have Canada ranks of May Be At Risk (12 species) and less than 1% have ranks of Extinct (three species) or Extirpated (one species). According to our data, exotic species account for 2% of bird species (11 species) and less than 1% have Canada ranks of Undetermined (four species). No species are in the Not Assessed category.

Long description for Figure 24

Figure 24 shows results of the general status assessments for bird species in Canada in the Wild Species 2010 report. The bar graph shows the number of bird species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, At Risk, May Be At Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 664 species occurring in Canada, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 37 as At Risk, 12 as May Be at Risk, 49 as Sensitive, 344 as Secure, 4 as Undetermined, 11 as Exotic and 203 as Accidental. Of the 306 species occurring in the Yukon, 3 were ranked as At Risk, 28 as May Be at Risk, 56 as Sensitive, 122 as Secure, 7 as Undetermined, 3 as Exotic and 87 as Accidental. Of the 281 species occurring in the Northwest Territories, 6 were ranked as At Risk, 7 as May Be at Risk, 39 as Sensitive, 142 as Secure, 44 as Undetermined, 3 as Exotic and 40 as Accidental. Of the 256 species occurring in Nunavut, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 4 as At Risk, 33 as Sensitive, 46 as Secure, 64 as Undetermined, 2 as Exotic and 105 as Accidental. Of the 502 species occurring in British Columbia, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 2 as Extirpated, 9 as At Risk, 20 as May Be at Risk, 43 as Sensitive, 272 as Secure, 2 as Undetermined, 12 as Exotic and 141 as Accidental. Of the 409 species occurring in Alberta, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 2 as Extirpated, 9 as At Risk, 3 as May Be at Risk, 59 as Sensitive, 218 as Secure, 11 as Undetermined, 9 as Exotic and 97 as Accidental. Of the 421 species occurring in Saskatchewan, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 17 as At Risk, 25 as May Be at Risk, 18 as Sensitive, 238 as Secure, 9 as Exotic and 112 as Accidental. Of the 388 species occurring in Manitoba, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 2 as Extirpated, 11 as At Risk, 12 as May Be at Risk, 47 as Sensitive, 224 as Secure, 9 as Exotic and 82 as Accidental. Of the 483 species occurring in Ontario, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 17 as At Risk, 7 as May Be at Risk, 36 as Sensitive, 235 as Secure, 4 as Undetermined, 9 as Exotic and 173 as Accidental. Of the 427 species occurring in Quebec, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 11 as At Risk, 8 as May Be at Risk, 70 as Sensitive, 210 as Secure, 8 as Exotic and 116 as Accidental. Of the 413 species occurring in New Brunswick, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 14 as At Risk, 13 as May Be at Risk, 41 as Sensitive, 176 as Secure, 13 as Undetermined, 8 as Exotic and 145 as Accidental. Of the 435 species occurring in Nova Scotia, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 11 as At Risk, 21 as May Be at Risk, 43 as Sensitive, 160 as Secure, 20 as Undetermined, 8 as Exotic and 169 as Accidental. Of the 349 species occurring in Prince Edward Island, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 5 as At Risk, 6 as May Be at Risk, 23 as Sensitive, 178 as Secure, 4 as Undetermined, 7 as Exotic and 124 as Accidental. Of the 402 species occurring in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2 were ranked as Extinct, 6 as At Risk, 6 as May Be at Risk, 11 as Sensitive, 163 as Secure, 24 as Undetermined, 4 as Exotic and 186 as Accidental. There were no species listed as occurring in the oceanic regions.

Comparison with previous Wild Species reports

The total number of bird species ranked in Canada has changed from 639 in 2000 to 653 in 2005 to 664 in 2010 (table 34). Since 2000, a total of 25 new bird species have been added to the national list. Most of these species have Canada ranks of Accidental, and many have been recorded from only one province or territory. Some taxonomic changes also have resulted in the appearance of new species names in the 2010 Canada list. The Blue Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) is now considered to be two species: Dusky Grouse (D. obscurus) and Sooty Grouse (D. fuliginosus). Also, the accidental species Bean Goose (Anser fabalis) has been split into two species. Occurrences of the now-split Bean Goose have been attributed to Tundra Bean-Goose (Anser serrirostris). Several species have had changes to the genus or species part of their scientific name, and there have been some changes to species names related to naming conventions and taxonomic decisions, but these do not affect the species’ status.

A total of 41 species had a change in their Canada rank since the last assessment. Among these changes, 23 species had an increased level of risk, one species had a reduced level of risk, four species were changed from or to the ranks Undetermined or Accidental, 12 species were added and one species was deleted. The changes were mostly due to new or updated COSEWIC assessments, to biological changes in the distribution of the species, and to procedural changes (table 35). Over both time spans, the number of species ranked as At Risk and Accidental had the highest increases.

| Canada rank | Years of the Wild Species reports 2000 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2005 |

Years of the Wild Species reports 2010 |

Average change between reports | Total change since first report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Extinct / Extirpated | 4 (1%) |

4 (0%) |

4 (0%) |

Stable | Stable |

| 1 At Risk | 21 (3%) |

27 (4%) |

37 (6%) |

+8 species | +16 species |

| 2 May Be At Risk | 11 (2%) |

12 (2%) |

12 (2%) |

+1 species | +1 species |

| 3 Sensitive | 53 (8%) |

41 (6%) |

49 (7%) |

-2 species | -4 species |

| 4 Secure | 345 (54%) |

358 (55%) |

344 (52%) |

-1 species | -1 species |

| 5 Undetermined | 17 (3%) |

5 (1%) |

4 (1%) |

-7 species | -13 species |

| 6 Not Assessed | 2 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

-1 species | -2 species |

| 7 Exotic | 13 (2%) |

11 (2%) |

11 (2%) |

-1 species | -2 species |

| 8 Accidental | 173 (27%) |

195 (30%) |

203 (30%) |

+15 species | +30 species |

| Total | 639 (100%) |

653 (100%) |

664 (100%) |

+13 species | +25 species |

| Scientific name | English name | 2005 Canada rank | 2010 Canada rank | Reason for change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aethia pusilla | Least Auklet | - | 8 | (I) This species was added to the Wild Species database in 2010 due to new information about an old accidental record for the Northwest Territories (AOU, 1998). |

| Alle alle | Dovekie | 4 | 3 | (P) The change is due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Anas fulvigula | Mottled Duck | - | 8 | (B) Added to the Wild Species database in 2010 due to a new accidental record in Ontario. |

| Anser anser | Graylag Goose | - | 8 | (B) New occurrence in Canada. |

| Ardea cinerea | Gray Heron | - | 8 | (B) New accidental record from Newfoundland and Labrador. |

| Buteo regalis | Ferruginous Hawk | 2 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Butorides striatus | Green-backed heron | 8 | - | (E) Error in previous rank, this species never occured in Canada. |

| Calcarius ornatus | Chestnut-collared Longspur | 4 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Calidris alpina | Dunlin | 4 | 3 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Calidris canutus | Red Knot | 2 | 1 | (C) The rufa subspecies of this species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Endangered, the roselaari subspecies is recognized as Threatened, and the islandica subspecies is recognized as Special Concern. |

| Caprimulgus vociferus | Whip-poor-will | 4 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Catharus bicknelli | Bicknell’s Thrush | 3 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Chaetura pelagica | Chimney Swift | 3 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Charadrius alexandrinus | Snowy Plover | 8 | 2 | (P) The change is due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). The species is known to breed in Saskatchewan. This was known in 2005. |

| Chordeiles minor | Common Nighthawk | 4 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Chroicocephalus ridibundus | Black-headed Gull | 4 | 3 | (P) The change is due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Contopus cooperi | Olive-sided Flycatcher | 4 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Dendragapus fuliginosus | Sooty Grouse | - | 3 | (T) This species was added to the Canada list in 2010 due to a taxonomic split. It used to be considered conspecific with Dusky Grouse, under the name of Blue Grouse (AOU, 2006). |

| Egretta gularis | Western Reef-Heron | - | 8 | (B) New accidental records in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador. |

| Falco peregrinus | Peregrine Falcon | 4 | 3 | (P) The change is due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Fulmarus glacialis | Northern Fulmar | 4 | 3 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Haematopus palliatus | American Oystercatcher | 8 | 5 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats (the species have been found to breed in Nova Scotia). |

| Hydrocoloeus minutus | Little Gull | 3 | 2 | (P) Change due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Larus thayeri | Thayer’s Gull | 4 | 3 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Leucophaeus atricilla | Laughing Gull | 4 | 3 | (P) Change due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Melanerpes erythrocephalus | Red-headed Woodpecker | 2 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

| Melanerpes lewis | Lewis’s Woodpecker | 3 | 2 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Myiarchus tyrannulus | Brown-crested Flycatcher | - | 8 | (B) Added to the Canada list in 2010 due to a new accidental record for British Columbia. |

| Oceanodroma homochroa | Ashy Storm-petrel | - | 8 | (B) Biological change. |

| Phalaenoptilus nuttallii | Common Poorwill | 4 | 3 | (P) Change due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Phoebastria immutabilis | Laysan Albatross | 5 | 3 | (I) Change due to improved knowledge of the species. |

| Phoebastria nigripes | Black-footed Albatross | 4 | 3 | (I) Change due to improved knowledge of the species. |

| Progne subis | Purple Martin | 4 | 3 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Pterodroma cookie | Cook’s Petrel | - | 8 | (B) Added to the Canada list in 2010 due to a new accidental record for British Columbia. |

| Puffinus puffinus | Manx Shearwater | 4 | 3 | (P) Change due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Spinus spinus | Eurasian Siskin | - | 8 | (B) This species was added to the Wild Species database for 2010 due to an accidental record from Newfoundland and Labrador. |

| Stercorarius skua | Great Skua | 5 | 4 | (P) Change due to a procedural change (different way of assessing the same information). |

| Sterna forsteri | Forster’s Tern | 3 | 4 | (B) Change due to change in species’ population size, distribution or threats. |

| Vermivora luciae | Lucy’s Warbler | - | 8 | (B) New accidental record in Alberta. |

| Vireo flavoviridis | Yellow-green Vireo | - | 8 | (B) New accidental record for Quebec. |

| Wilsonia canadensis | Canada Warbler | 4 | 1 | (C) This species is now recognized by COSEWIC as Threatened. |

Threats to Canadian birds

The major threats to Canadian birds are well known and include habitat loss and fragmentation; pollution and contamination; predation and brood parasitism; disease; over-exploitation; competition from invasive or exotic species; other forms of human-caused mortality (e.g. building and tower strikes and, road traffic); and natural and anthropogenic climate and weather variation. Threats in migratory stopover and wintering sites complicate the situation. Therefore, many bird population research and monitoring programs involve international co-operation to study the same species in different locations and at different points in the life cycle.

Conclusion

Canada provides important breeding habitat for many species of North American birds, and many Canadians appreciate the diversity and abundance of birds that spend all, or part of the year here. For these reasons, and many others, it is important to update general status ranks for birds regularly. This update allows Canada ranks to be adjusted to the actual situation, ensures that ranks are comparable within and among species groups, and allows the national list to be updated with species new to Canada. Although birds are generally better studied than other groups covered in this report, it is still important to improve our knowledge of bird populations, particularly for species breeding in northern Canada and other remote locations, and for species not adequately covered by current surveys.

Further information

Bird Studies Canada. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Brooke, M. and Birkhead, T. (editors). 1991. The Cambridge encyclopaedia of ornithology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 362 pp.

Canadian Bird Trends. (Accessed April 8, 2010).

Canadian Migration Monitoring Network. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Canadian Wildlife Service - Nature. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Cannings, R. J. and Angell, T. 2001. Western Screech-Owl (Otus kennicottii). In The birds of North America, No. 597 (A. Poole and F. Gill, editors). The Birds of North America Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Chardine, J. W. 1999. Population status and trend of the Atlantic Puffin in North America. Bird Trends 7: 15-17.

Christmas Bird Count in Canada. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Western Screech-owl Otus kennicottii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa: 31 pp.

Ehrlich, P. R., Dobkin, D. S. and Wheye, D. 1988. The birder’s handbook. A field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster Inc, New York: 785 pp.

Faaborg, J. 1988. Ornithology, an ecological approach. Prentice Hall, New Jersey: 470 pp.

Fundy shorebirds. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Lowther, P. E., Diamond, A. W., Kress, S. W., Robertson, G. J. and Russell, K. 2002. Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica). In The birds of North America, No. 709 (A. Poole and F. Gill, editors). The Birds of North America Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) program. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

North American Breeding Bird Survey. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Poole, A. (editor). 2010. The birds of North American online: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. (Accessed March 31, 20010).

Sauer, J. R., Hines, J. E. and Fallon, J. 2005. The North American breeding bird survey, results and analysis 1966-2004. Version 2005.2. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD. (Accessed March 31, 2010).

Smith, K. G., Withgott, J. H. and Rodewald, P. G. 2000. Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus). In The birds of North America, No. 518 (A. Poole and F. Gill, editors). The Birds of North America Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

References

American Ornithologists’ Union. 1998. Checklist of North American birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. (and supplements to 2009).

Barber, K. (editor). 1998. The Canadian Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Toronto, Oxford, New York: 1707 pp.

Cannings, D. 2009. The 109th Christmas bird count: cross-Canada report. Birdwatch Canada 48: 12-19.

Robertson, G. J., Wilhelm, S. I. and Taylor, P. A. 2004. Population size and trends of seabirds breeding on Gull and Great Islands, Witless Bay Islands Ecological Reserve, Newfoundland, up to 2003. Canadian Wildlife Service technical report series No. 418, Atlantic Region: 45 pp.

Robertson, G. J. and Elliot, R. D. 2002. Population size and trends of seabirds breeding in the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Canadian Wildlife Service technical report series No. 393, Atlantic Region: 36 pp.

Robertson, G. J., Elliot, R. D. and Chaulk, K. G. 2002. Breeding seabird population in Groswater Bay, Labrador, 1978 and 2002. Canadian Wildlife Service technical report series No. 394, Atlantic Region: 31 pp.

Robertson, G. J. and Elliot, R. D. 2002. Changes in seabird populations breeding on Small Island, Wadham Islands, Newfoundland. Canadian Wildlife Service technical report series No. 381, Atlantic Region: 26 pp.

Rodway, M. S., Regher, H. M. and Chardine, J. W. 2003. Status of the largest breeding concentration of Atlantic Puffins Fratercula arctica, in North America. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 117: 70-75.