Wild species 2010: chapter 3

Section 1: Introduction

Context

The year 2010 is the International Year of Biodiversity. This represents a unique opportunity to better understand the diversity of species that surround us, and to protect this diversity to our best. The report Wild Species 2010 perfectly fits within this context, by analyzing the situation for an impressive number of species present in Canada.

Canada is home to over 70 000 wild species including, but by no means limited to, mammals, birds, fishes, vascular plants, butterflies, dragonflies, bees, worms, mosses and mushrooms. These species, and other aspects of nature, are highly valued by Canadians. Canadians recognize that wild species provide a host of resources, such as foods, medicines and materials, as well as services that we often take for granted, such as cleaning the air and water, regulating the climate, generating and conserving soils, pollinating crops, and controlling pests. In addition, Canadians take pride in, and profit internationally from, a reputation for pristine landscapes with abundant wildlife. But perhaps above all else, Canadians value the aesthetic splendour and spiritual nourishment still afforded by the incredible range of wild species living in Canada. For all these reasons, we acknowledge a responsibility to future Canadians and the rest of the world to conserve our nation’s natural heritage, by preventing the loss of species due to human actions.

The first step in preventing the loss of species is to know which species we have, where they occur and how they are doing. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide this overview. The report Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada presents the results of general status assessments for 11 950 species, including most of Canada’s vertebrate species, all of Canada’s vascular plants, macrolichens, mosses and several invertebrate groups. General status assessments integrate the best available information to create a snapshot of each species’ status; their population size and distribution, the threats that each species faces in Canada, and any trends in these factors. General status assessments are used to categorize species into coarse-scaled general status ranks; some species will be ranked secure; some will show early signs of trouble and may need additional monitoring or management, while still others will be prioritized for detailed status assessments. General status ranks also highlight information gaps: for some species, there will not be enough information to assess whether they are secure or already in trouble. Each species receives a general status rank for each province, territory or ocean region in which it occurs, as well as a Canada General Status rank (Canada rank), reflecting the overall status of the species in Canada.

One of the strengths of this approach is that general status ranks are generated for many species in all regions of the country, allowing patterns of declines or threats to emerge across suites of species. In addition, general status ranks are reviewed and updated periodically. This will allow Canadians to begin to track patterns of improvement or decline through time, revealing which species are maintaining or improving their status and which are declining or facing new threats. Such patterns not only give a better indication of the nature and magnitude of a problem, but may also point the way to improved conservation practices.

The 2010 report is the third of the Wild Species series. A report is produced every five years and this one follows the 2005 and 2000 reports. The Wild Species series establishes a comprehensive, common platform for examining the general status of species across their Canadian range, as well as a solid baseline against which future changes in the distribution and abundance of species can be compared.

Assessing this mix of species from all regions of the country presents a considerable challenge - the number of species is large and the area great. The species are distributed across the length and breadth of Canada: 10 million square kilometres of land and fresh water, almost 6 million square kilometres of ocean, and 202 080 kilometres of coast (the longest coastline in the world). Across this massive area, the distribution of species is influenced by the staggering array of topography, soil types and habitats found within our borders including boreal forest, tundra, taiga, bogs, temperate rainforests, grasslands, marshlands, alpine meadows, the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic Ocean coastlines.

Assessing the general status of Canadian species is challenging, but the process is essential. Our resource-based economy and high standard of living have an impact on the natural world: vegetation is cleared, cities expand, resources are extracted, waste is produced and exotic species are introduced. In altering nature for the benefit of Canadians, our goal must be to ensure that our activities do not imperil the very species that we both celebrate and depend upon. The Wild Species series is a tool for all Canadians; a guide indicating where more information is needed, a method of tracking changes in the status of Canada’s species over time, an effective tool for improved conservation, and a testimony to the cooperative will of Canadians to protect wild species.

The species concept

The general status assessment process assigns ranks to species, commonly defined as populations of organisms that do not usually interbreed with other populations, even where they overlap in space and time. Species are the most common and recognizable units of biological classification used in conservation, but they are not the only one. Subspecies (genetically distinct populations that may look and behave differently) and stocks (population divisions of harvested species, that may require different management approaches because they experience different ecological pressures) are examples of divisions below the species level. While these divisions have merit, there tends to be more disagreement over the precise limits and biological significance of differences observed at this finer scale. Moreover, relatively few species have been examined closely enough to distinguish whether or not subspecies or discrete stocks exist. Accordingly, only species were assigned general status ranks.

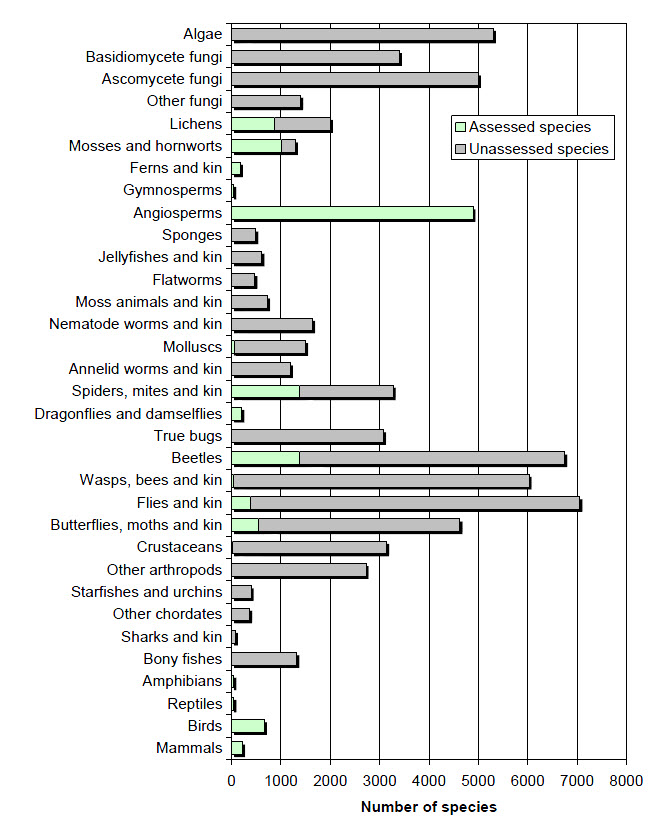

Life is variable at every conceivable scale. From the DNA that makes up an organism’s genes to the composition and behaviour of entire ecosystems, a seemingly endless and complex array of living things surrounds us. The most familiar measure of diversity is the number and type of species, and this report focuses on that perspective of biodiversity (figure 1). However, the species perspective is not the only valuable viewpoint. For example, Canada’s Arctic has relatively few species, but many of the species occurring there have special adaptations to extremes of climate that allow them to persist there and nowhere else. Variety in types of organisms is at least as important as their numbers, because different types of organisms have important, often irreplaceable, functions in nature. For example, certain species of fungi live in association with plant roots and provide the plant with vital minerals. Without their inconspicuous fungal partners, many species of vascular plants could simply not grow!

Long description for Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the diversity of species in Canada (about 70 000 species) and number of species assessed (11 950 species) in the report Wild Species 2010. The bar graph shows the number of species assessed, and the total number of species found in Canada for each taxonomic group. All species were assessed for the following groups: mammals (218), birds (664), reptiles (48), amphibians (47), dragonflies and damselflies (211), angiosperms (4891), gymnosperms (43), and ferns and kin (177). A portion of species were assessed for the following groups: crustaceans (11 species of 3139), butterflies, moths and kin (538 species of 4629), flies and kin (386 species of 7058), wasps, bees and kin (41 species of 6028), beetles (1375 species of 6748), spiders mites and kin (1379 species of 3275), molluscs (54 species of 1500), mosses and hornworts (1006 species of 1293), and lichens (861 species of 2000). The remaining groups have not yet been assessed. These include bony fishes (1323), sharks and kin (78), other chordates (366), starfish and urchins (398), other arthropods (2727), true bugs (3079), annelid worms and kin (1192), nematode worms and kin (1643), moss animals and kin (728), flatworms (472), jellyfish and kin (618), sponges (490), all fungi (9800), and algae (5303).

Why a report on species in Canada?

The Wild Species series on the general status of species in Canada is a requirement of the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, an agreement in principle established in 1996 by provincial, territorial, and federal ministers responsible for wildlife. The goal of the Accord is to prevent species in Canada from becoming extinct or extirpated because of human impact. As part of this goal, parties to the Accord agree to “monitor, assess and report regularly on the status of all wild species” with the objective of identifying those species whose populations are starting to decline, those for which a formal status assessment or additional management attention is necessary, and those for which more information is needed. Each province, territory, and federal agency responsible for wildlife undertakes to assess the species occurring within its jurisdiction.

Reports from the Wild Species series also serve as the basis to fulfill a requirement under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) of Canada. This Act is a key federal government commitment to prevent wildlife species from becoming extinct and secure the necessary actions for their recovery. Section 128 of this law stipulates that “five years after this section comes into force and at the end of each subsequent period of five years, the Minister must prepare a general report on the status of wildlife species” (Government of Canada, 2002). The first of the general report was tabled in Parliament in 2008 and reports from the Wild Species series will thereafter continue to serve as the basis to fulfill this requirement (Environment Canada, 2009).

What this report does

This report summarizes the general status assessments of a large number and variety of wild species occurring in Canada. It focuses on the general status of all species within each of these groups, rather than on the general status of only rare or endangered species. So, for example, one can ask questions like: Are salamanders doing better than frogs in Nova Scotia? Has the general status of salamanders in Nova Scotia changed since 2000? Is this pattern the same in Manitoba, or Canada as a whole? How does the general status of salamanders and frogs compare with that of other groups that are associated with water, like fishes? These and many other questions can be answered because the report draws together information on different types of species, from all provinces and territories and portions of three bordering oceans, and presents general status ranks for species in each region as well as overall Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks).

General status assessments focus on establishing what information and expertise already exist and using these to develop general status ranks for as many species as possible. This allows existing knowledge to be presented to the public rather than delaying a report until complete scientific information is available. There is a large number of species that are undescribed or unrecorded (i.e. species that are new to science or species that are already known to science but that have not yet been documented as occurring in Canada; Mosquin and Whiting, 1992).

The exceptional number and variety of species covered in the Wild Species series requires that it distill detailed information into broad general status categories. Accordingly, while in some cases the report draws upon the information available from initiatives devoted to particular species groups, regions, or functions, it is not a replacement for these efforts, which have a narrower focus and more specific aims. In particular, general status assessments do not replace comprehensive scientific evaluations by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) or provincial and territorial equivalents, which provide in-depth, targeted assessments of individual species that may be at risk. General status assessments also differ in methods and scope from bird conservation plans (e.g. Partners in Flight for landbirds; Canadian Shorebird Conservation Plan for shorebirds; and Wings Over Water for seabirds and colonial waterbirds), which have developed their own priority-setting systems tailored to their unique program objectives.

The following is a summary of some of the achievements of the Wild Species series. This series:

- integrates information on a large number and variety of Canada’s wild species (11 950 species in 20 groups), including most vertebrates and all vascular plants that have been found in Canada. This allows comparison of general status between individual species, as well as comparison within and between groups of species, based on taxonomic or regional boundaries;

- alerts Canadians to species that may require attention to prevent their extinction, before the species reach a “critical condition.” Early warning of a species in trouble increases the success and cost-effectiveness of conservation programs. General status assessments also help to prioritize which species are in most urgent need of a more detailed status assessment, additional management attention, or basic research into population size, distribution, threats or trends;

- updates the general status of the species that were assessed for the first time in the previous reports. This comparison highlights species whose general status is declining or improving, shows where information gaps have been filled, and where further information is still required;

- summarizes the identity and distribution of select non-native wild species (exotic species) across Canada. Few Canadians are aware of fauna and flora that are introduced, or the potential impacts of exotics on native species;

- identifies gaps in our knowledge about wild species in Canada. Directing resources and expertise towards filling these gaps is essential for a more accurate and comprehensive picture of the general status of Canadian wild species;

- establishes or enhances local networks of people with information to share about Canada’s wild species. People identified during this process form part of a coordinated knowledge base critical to this, and future, Wild Species reports;

- shares information with Canadians about the diversity and general status of wild species across the country. Consolidating information about wild species in Canada lets everyone from schoolchildren to resource managers, farmers, and developers know what species are present in Canada and how they are doing.

Users of the reports from the Wild Species series

Users of the reports from the Wild Species series include:

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) – General status ranks are used by some of the Species Specialist Subcommittees (SSCs) to help prioritize species for detailed COSEWIC status assessments.

- Wildlife managers, land-use planning committees and co-management boards – General status ranks used to provide lists of species in a given area, and a guide to species’ status.

- Industry and consultants – General status ranks provide information used to conduct environmental impact assessments.

- Funding programs – General status ranks used to help prioritize which research and conservation projects are funded.

- Research scientists – General status ranks used to obtain lists of exotic species, and distributions of species in Canada.

- General public – General status ranks used to provide lists of species in a given area, as a guide to species’ status, and to provide information used to check the accuracy of environmental impact assessments.

- Educators and students – General status ranks and the reports from the Wild Species series have been used as an educational resource and a research tool.

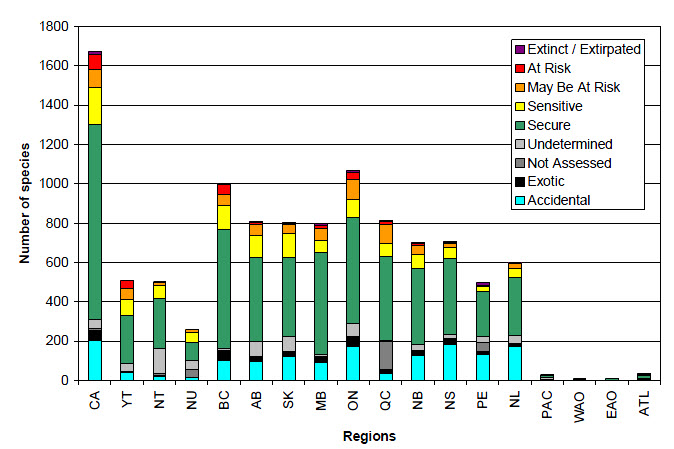

Summary of Wild Species 2000

The Wild Species 2000 report (Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council, 2001) was the first report on the general status of species in Canada, and summarized the provincial/territorial/oceanic region and Canada General Status Ranks (Canada ranks) of species in eight groups: ferns, orchids, butterflies, freshwater fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Birds comprised the largest species group studied. The original 2000 database was updated in 2002 with the addition, among other things, of the completed Canada ranks for freshwater fishes and butterflies. A total of 1670 species were then assessed (figure 2). The majority (74%) of species had Canada ranks of Secure, while 5% had Canada ranks of At Risk and 5% had Canada ranks of May Be At Risk (table 1). Reptiles represented the taxonomic group with the lowest percentage of species ranked as Secure. The report also underlined that exotic species represented a potential problem. As predators, parasites, and competitors of native species, exotic species have the potential to cause ecological disturbance in communities. Importantly, freshwater fishes made up the majority of exotic species recorded in that report.

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 shows the results of the general status assessments for all species in the Wild Species 2000 report in Canada. The analyses include the database updated in 2002 for the freshwater fishes and for the butterflies. The bar graph shows the number of species ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, At Risk, May Be at Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory, and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 1670 species occurring in Canada, 14 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 77 as At Risk, 89 as May Be at Risk, 187 as Sensitive, 992 as Secure, 49 as Undetermined, 6 as Not Assessed, 53 as Exotic, and 203 as Accidental. Of the 608 species occurring in the Yukon, 40 were ranked as At Risk, 54 as Maybe at Risk, 86 as Sensitive, 244 as Secure, 37 as Undetermined, 5 as Not Assessed, 4 as Exotic, and 38 as Accidental. Of the 502 species occurring in the Northwest Territories, 3 were ranked as At Risk, 15 as May Be at Risk, 69 as Sensitive, 255 as Secure, 49 as Undetermined, 12 as Not Assessed, 4 as Exotic, and 21 as Accidental. Of the 258 species occurring in Nunavut, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 11 as May Be at Risk, 55 as Sensitive, 89 as Secure, 49 as Undetermined, 37 as Not Assessed, 2 as Exotic, and 14 as Accidental. Of the 1003 species occurring in British Columbia, 6 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 51 as At Risk, 55 as May Be at Risk, 122 as Sensitive, 607 as Secure, 10 as Undetermined, 6 as Not Assessed, 47 as Exotic, and 99 as Accidental. Of the 809 species occurring in Alberta, 4 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 12 as At Risk, 54 as May Be at Risk, 112 as Sensitive, 432 as Secure, 73 as Undetermined, 6 as Not Assessed, 22 as Exotic, and 94 as Accidental. Of the 803 species occurring in Saskatchewan, 3 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 7 as At Risk, 47 as May Be at Risk, 123 as Sensitive, 402 as Secure, 72 as Undetermined, 3 as Not Assessed, 22 as Exotic, and 124 as Accidental. Of the 798 species occurring in Manitoba, 9 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 16 as At Risk, 60 as May Be at Risk, 63 as Sensitive, 517 as Secure, 11 as Undetermined, 4 as Not Assessed, 27 as Exotic, and 91 as Accidental. Of the 1068 species occurring in Ontario, 13 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 35 as At Risk, 98 as May Be at Risk, 96 as Sensitive, 535 as Secure, 65 as Undetermined, 52 as Exotic, and 174 as Accidental. Of the 815 species occurring in Quebec, 6 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 15 as At Risk, 99 as May Be at Risk, 66 as Sensitive, 426 as Secure, 3 as Undetermined, 147 as Not Assessed, 18 as Exotic, and 35 as Accidental. Of the 700 species occurring in New Brunswick, 6 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 9 as At Risk, 43 as May Be at Risk, 74 as Sensitive, 384 as Secure, 31 as Undetermined, 5 as Not Assessed, 19 as Exotic, and 129 as Accidental. Of the 706 species occurring in Nova Scotia, 6 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 5 as At Risk, 18 as May Be at Risk, 56 as Sensitive, 389 as Secure, 20 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, 27 as Exotic, and 183 as Accidental. Of 496 species occurring in Prince Edward Island, 11 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 1 as At Risk, 8 as May Be at Risk, 21 as Sensitive, 231 as Secure, 32 as Undetermined, 44 as Not Assessed, 17 as Exotic, and 131 as Accidental. Of the 600 species occurring in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 4 as At Risk, 25 as May Be at Risk, 45 as Sensitive, 294 as Secure, 42 as Undetermined, 1 as Not Assessed, 14 as Exotic, and 173 as Accidental. Of the 32 species occurring in the Pacific Ocean region, 4 were ranked as At Risk, 3 as Sensitive, 9 as Secure, 9 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, and 5 as Accidental. Of the 10 occurring in the Western Arctic Ocean region, 1 was ranked as Sensitive, 3 as Secure, 1 as Undetermined, 1 as Not Assessed, and 4 as Accidental. Of the 10 species occurring in the Eastern Arctic Ocean region, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 1 as Sensitive, 6 as Secure, and 2 as Undetermined. Of the 35 species occurring in the Atlantic Ocean region, 3 were ranked as Extinct/Extirpated, 4 as At Risk, 5 as Sensitive, 13 as Secure, 2 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, and 6 as Accidental.

Note: Codes used for the regions are described in the methods.

| Taxonomic group | Number of species | Proportion of Secure* |

|---|---|---|

| Ferns | 122 | 66% |

| Orchids | 78 | 68% |

| Butterflies | 293 | 78% |

| Freshwater fishes | 232 | 68% |

| Amphibians | 45 | 64% |

| Reptiles | 46 | 43% |

| Birds | 639 | 80% |

| Mammals | 215 | 75% |

| Total | 1670 | 74% |

* When excluding species ranked as Extinct / Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental.

Summary of Wild Species 2005

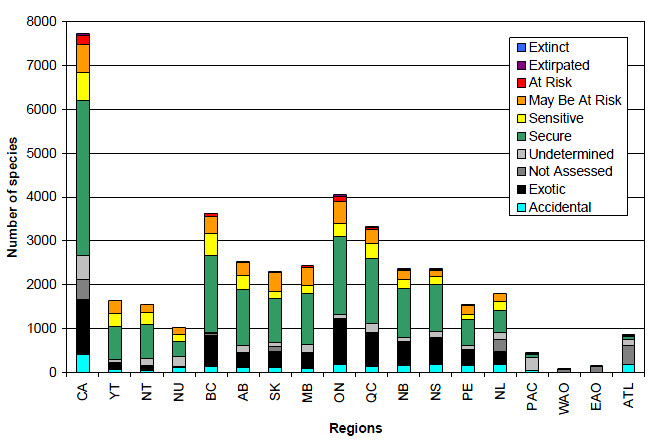

The Wild Species 2005 report (Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council, 2006) was the second report on the general status of species in Canada. A total of 7732 species were assessed from all provinces, territories, and ocean regions (figure 3), representing all of Canada’s vertebrates species (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals), all of Canada’s vascular plants, and four invertebrate groups (freshwater mussels, crayfishes, odonates and tiger beetles). Of the species ranked At Risk, May Be At Risk, Sensitive and Secure, a total of 70% had a Canada General Status Rank (Canada rank) of Secure (table 2). Again, one of the issues highlighted in this report was also the large number of non-native species in Canada. Of the 7732 species assessed in Wild Species 2005, 16% were ranked Exotic at the national level, meaning that these species are not native to Canada, but were introduced by humans. Of the groups covered in this report, the vascular plants (including ferns and orchids) had the highest proportion of Exotic species (24%).

In total, 1330 species that were assessed in the Wild Species 2000 report were reassessed in the Wild Species 2005 report. Of these, 12% have been assessed with a different Canada rank in 2005. However, changes in Canada ranks primarily reflect attempts to provide a more accurate picture of species’ status, and not true biological change (i.e. changes in species population size, distribution or threats) since 2000. In total, 39% of changes involved species moving into a rank with an increased level of risk, 31% of changes involved species moving into a rank with a reduced level of risk, and 30% involved species moving into or out of the Undetermined, Not Assessed, Accidental or Extirpated categories. Considering only the species ranked in both 2000 and 2005, changes in Canada rank have not had a significant impact on the proportion of species in each general status category.

Long description for Figure 3

Figure 3 shows the results of the general status assessments for all species in the Wild Species 2005 report in Canada. The bar graph shows the number of species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, At Risk, May Be at Risk, Sensitive, Secure, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic, and Accidental in Canada, each province and territory and the 4 oceanic regions. Of the 7732 species occurring in Canada, 5 were ranked as Extinct, 30 as Extirpated, 206 as At Risk, 634 as May Be at Risk, 657 as Sensitive, 3541 as Secure, 534 as Undetermined, 465 as Not Assessed, 1254 as Exotic, and 406 as Accidental. Of the 1649 species occurring in the Yukon, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 296 as May Be at Risk, 300 as Sensitive, 757 as Secure, 62 as Undetermined, 22 as Not Assessed, 139 as Exotic, and 72 as Accidental. Of the 1544 species occurring in the Northwest Territories, 4 were ranked as At Risk, 183 as May Be at Risk, 258 as Sensitive, 793 as Secure, 152 as Undetermined, 17 as Not Assessed, 98 as Exotic, and 39 as Accidental. Of the 1022 species occurring in Nunavut, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 2 as At Risk, 149 as May Be at Risk, 168 as Sensitive, 349 as Secure, 221 as Undetermined, 10 as Not Assessed, 15 as Exotic, and 106 as Accidental. Of the 3628 species occurring in British Columbia, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 8 as Extirpated, 64 as At Risk, 382 as May Be at Risk, 515 as Sensitive, 1748 as Secure, 19 as Undetermined, 57 as Not Assessed, 699 as Exotic, and 135 as Accidental. Of the 2535 species occurring in Alberta, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 4 as Extirpated, 24 as At Risk, 286 as May Be at Risk, 326 as Sensitive, 1272 as Secure, 175 as Undetermined, 23 as Not Assessed, 324 as Exotic, and 100 as Accidental. Of the 2308 species occurring in Saskatchewan, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 3 as Extirpated, 34 as At Risk, 418 as May Be at Risk, 157 as Sensitive, 1022 as Secure, 75 as Undetermined, 118 as Not Assessed, 361 as Exotic, and 119 as Accidental. Of the 2440 species occurring in Manitoba, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 6 as Extirpated, 29 as At Risk, 426 as May Be at Risk, 189 as Sensitive, 1155 as Secure, 178 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, 375 as Exotic, and 79 as Accidental. Of the 4052 species occurring in Ontario, 2 were ranked as Extinct, 30 as Extirpated, 109 as At Risk, 511 as May Be at Risk, 291 as Sensitive, 1779 as Secure, 98 as Undetermined, 3 as Not Assessed, 1056 as Exotic, and 173 as Accidental. Of the 3328 species occurring in Quebec, 4 were ranked as Extinct, 14 as Extirpated, 60 as At Risk, 308 as May Be at Risk, 350 as Sensitive, 1486 as Secure, 198 as Undetermined, 7 as Not Assessed, 773 as Exotic, and 128 as Accidental. Of the 2362 species occurring in New Brunswick, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 13 as Extirpated, 17 as At Risk, 200 as May Be at Risk, 206 as Sensitive, 1138 as Secure, 80 as Undetermined, 4 as Not Assessed, 554 as Exotic, and 147 as Accidental. Of the 2362 species occurring in Nova Scotia, 3 were ranked as Extinct, 16 as Extirpated, 18 as At Risk, 143 as May Be at Risk, 183 as Sensitive, 1062 as Secure, 134 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, 622 as Exotic, and 179 as Accidental. Of the 1537 species occurring in Prince Edward Island, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 12 as Extirpated, 3 as At Risk, 208 as May Be at Risk, 99 as Sensitive, 607 as Secure, 80 as Undetermined, 2 as Not Assessed, 375 as Exotic, and 150 as Accidental. Of the 1799 species occurring in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2 were ranked as Extinct, 8 as At Risk, 181 as May Be at Risk, 189 as Sensitive, 521 as Secure, 148 as Undetermined, 281 as Not Assessed, 295 as Exotic, and 174 as Accidental. Of the 457 species occurring in the Pacific Ocean region, 11 were ranked as At Risk, 7 as May Be at Risk, 26 as Sensitive, 83 as Secure, 282 as Undetermined, 3 as Not Assessed, and 45 as Accidental. Of the 81 species occurring in the Western Arctic Ocean region, 1 was ranked as At Risk, 2 as Sensitive, 12 as Secure, 7 as Undetermined, 50 as Not Assessed, and 9 as Accidental. Of the 165 species occurring in the Eastern Arctic Ocean region, 2 were ranked as At Risk, 8 as Sensitive, 10 as Secure, 15 as Undetermined, and 130 as Not Assessed. Of the 871 species occurring in the Atlantic Ocean region, 1 was ranked as Extinct, 1 as Extirpated, 12 as At Risk, 11 as May Be at Risk, 30 as Sensitive, 69 as Secure, 139 as Undetermined, 430 as Not Assessed, and 178 as Accidental.

Note: Codes used for the regions are described in the methods.

| Taxonomic group | Number of species | Proportion of Secure* |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular plants (including ferns and orchids) | 5074 | 70% |

| Freshwater mussels | 55 | 37% |

| Crayfishes | 11 | 78% |

| Odonates | 209 | 73% |

| Tiger beetles | 30 | 72% |

| Fishes | 1389 | 69% |

| Amphibians | 46 | 65% |

| Reptiles | 47 | 31% |

| Birds | 653 | 82% |

| Mammals | 218 | 74% |

| Total | 7732 | 70% |

* When excluding species ranked as Extinct, Extirpated, Undetermined, Not Assessed, Exotic or Accidental.

Further information

Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. (Accessed February 23, 2010).

Canadian Biodiversity Information Facility. (Accessed December 30, 2009).

Canadian shorebird conservation plan. (Accessed May 5, 2010).

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). (Accessed February 23, 2010).

Partners in Flight - Canadian landbird conservation plan. (Accessed May 5, 2010).

Species at Risk Public Registry. (Accessed February 23, 2010).

Tree of Life. (Accessed February 23, 2010).

Wild Species, the General Status of Species in Canada. (Accessed December 30, 2009).

Wings Over Water. Canada’s Waterbird Conservation Plan. (Accessed May 5, 2010).

References

Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2001. Wild Species 2000: The General Status of Species in Canada. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa: 48 pp.

Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2006. Wild Species 2005: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 141 pp.

Environment Canada. 2009. The status of wild species in Canada. Species at risk act general status report, overview document 2003-2008. Government of Canada, Ottawa: 12 pp.

Government of Canada. 2002. Species at Risk Act. Department of Justice Canada, Ottawa: 91 pp.

Mosquin, T. and P. G. Whiting. 1992. Canada country study of diversity: taxonomic and ecological census, economic benefits, conservation costs and unmet needs. Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa: 282 pp.