Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) in Canada: Ontario Populations [Proposed]: Critical Habitat

The identification of critical habitat for species that are listed as Threatened, Endangered or Extirpated on Schedule 1 is a requirement of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Once identified, SARA includes provisions to prevent the destruction of critical habitat. Critical habitat is defined under Section 2(1) of SARA as:

SARA defines habitat for aquatic species at risk as:

For the Eastern Sand Darter in Ontario, critical habitat has been identified to the extent possible, using the best information currently available. The critical habitat identified in this recovery strategy describes the geospatial areas that contain the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of the species. The current areas identified may be insufficient to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the species. As such, a schedule of studies has been included to further refine the description of critical habitat (in terms of its biophysical functions/features/attributes as well as its spatial extent) to support its protection.

Using the best available information, critical habitat has been identified using a bounding box approach for the following areas where the species presently occurs: the Sydenham River, Thames River, Grand River, Big Creek, and Long Point Bay; additional areas of potential critical habitat within the Lake St. Clair/Walpole Island area will be considered in collaboration with Walpole Island First Nation. Using this approach, the box outlines areas in which the species is known to occur (i.e., areas where multiple adults and/or young of the year (YOY) have been captured). It is further refined through the use of essential functions, features and attributes for each life-stage of the Eastern Sand Darter to identify patches of critical habitat within the bounding box. Life stage habitat information was summarized in chart form using available data and studies referred to in Section 1.4.1 (Habitat and biological needs). The bounding box approach was the most appropriate, given the limited information available for the species and the lack of detailed habitat mapping for these areas. Where habitat information was available (e.g., bathymetry data), it was used to inform the identification of critical habitat.

For all river locations, critical habitat was identified based on a bounding box approach and further refined with an ecological classification system, the Aquatic Landscape Inventory System (ALIS). ALIS was developed by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) to define stream segments based on a number of unique characteristics found only within those valley segments. Each valley segment is defined by a collection of landscape variables that are believed to have a controlling effect on the biotic and physical processes within the catchments. Therefore, if a population has been found in one part of the ecological classification, there is no reason to believe that it would not be found in other spatially contiguous areas of the same valley segment. Critical habitat for the Eastern Sand Darter was therefore identified as the reach of rivers that includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present.

For lake locations, critical habitat is currently identified, based on a bounding box approach, and refined using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) bathymetry data.

Any additional detail on the specific methods used to identify critical habitat is provided in the individual critical habitat descriptions (below), when relevant.

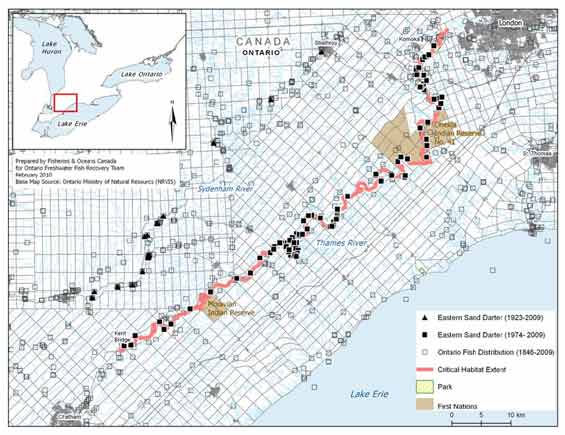

Sydenham River: Sampling data in the river was taken from the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) database for the period from 1927 to 2009. There are only 43 individuals caught in the last 10 years (Bouvier and Mandrak 2010).

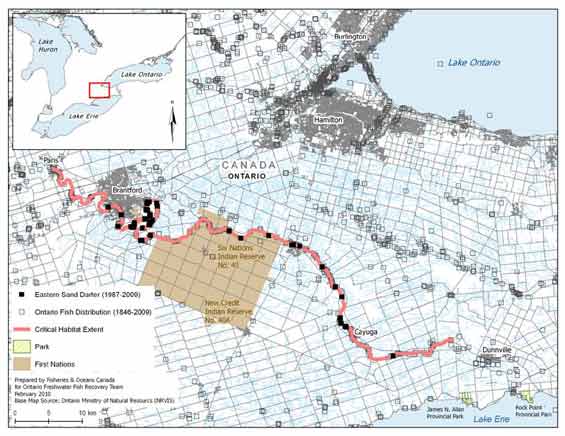

Thames River: Sampling data in the river was taken from the DFO database for the period from 1923 to 2009. There has been extensive targeted sampling for Eastern Sand Darter in the river. This population is considered the largest population of Eastern Sand Darter in Canada with more than 5000 individuals caught in the last 10 years (Bouvier and Mandrak 2010).

Grand River: The first capture of Eastern Sand Darter in the Grand River was in 1987. Since then there have been more than 735 individuals caught through targeted sampling (Bouvier and Mandrak 2010).

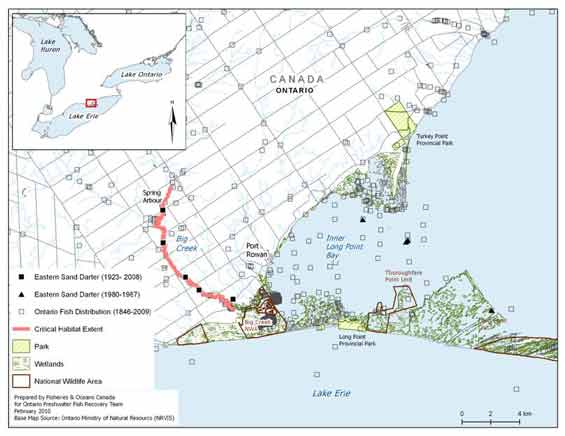

Big Creek (Norfolk County): Eastern Sand Darter were found in 1923 and 1955 (Hubbs and Brown 1929; Holm and Mandrak 1996). This population was thought to be extirpated, but in 2008 three individuals were captured (A. Dextrase, unpublished data; DFO, unpublished data).

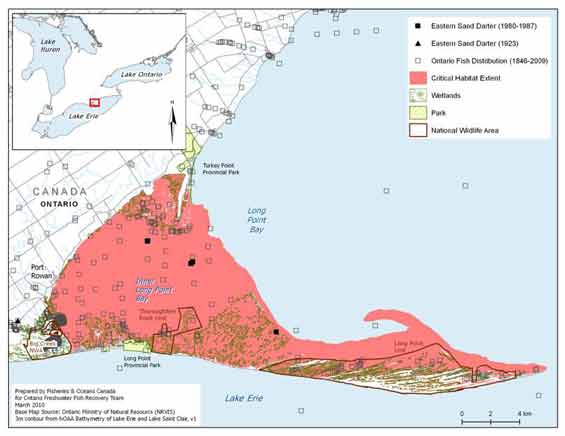

Long Point Bay (Lake Erie): The Eastern Sand Darter has been captured from Inner Long Point Bay at four locations. Index netting trawls by OMNR since 1972 captured Eastern Sand Darter every year between 1979 and 1987 except 1983 (Holm and Mandrak 1996). These locations overlap with the limited sand substrate, as much of the bay has aquatic vegetation. Using available sampling data, critical habitat has currently been identified based on a bounding box approach, and refined using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) bathymetry data.

Population viability

In the absence of catastrophic events, the minimum viable population (MVP) size is predicted to be 323 adults. Inclusion of a 0.05, 0.10 and 0.15 probability of catastrophic decline per generation produced MVP values of 4 224, 52 822 and 595 000 respectively.

The minimum area for population viability (MAPV for Eastern Sand Darter was estimated for Canadian populations. The MAPV is defined as the amount of exclusive and suitable habitat required for a demographically sustainable recovery target based on the concept of a MVP size (Finch et al. 2011). The estimated MVP for Eastern Sand Darter is 52 882 adults with a 0.10 probablility of catastrophic decline per generation. For more information on the MVP and MAPV and associated methodology please refer to Finch et al. (2011).

The MAPV is a quantitative metric of critical habitat that can assist with the recovery and management of species at risk (Finch et al. 2011). Using the MVP of 52 882 adults as a recovery target would require approximately 0.147 km2 of suitable habitat (Finch et al. 2011). MAPV values are somewhat conservative in that they represent the sum of habitat needs calculated for all life-history stages of the Eastern Sand Darter; these numbers do not take into account the potential for overlap in the habitat of the various life-history stages and may overestimate the area required to support an MVP. However, since many of these populations occur in areas of degraded habitat (MAPV assumes habitat quality is optimal), areas larger than the MAPV may be required to support an MVP. In addition, for many populations, it is likely that only a portion of the habitat within that identified as the area within which critical habitat is found would meet the functional requirements of the species' various life-stages.

There is limited information on the habitat needs for the various life stages of the Eastern Sand Darter. Table 10 summarizes available knowledge on the essential functions, features and attributes for each life-stage. Refer to Section 1.4.1 (Habitat and biological needs) for additional information and full references. Areas identified as critical habitat must support one or more of these functions, feature or attributes.

| Life stage | Habitat requirement (function) |

Feature(s) | Attribute(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spawn to larvae (< 18mm Total Length) |

|

|

|

| Juveniles (> 18mm Total Length) |

|

|

|

| Adult (ages 1 {sexual maturity} to 3 years old) |

|

|

|

*where known or supported by existing data

Studies to further refine knowledge on the functions, features and attributes for various life-stages of the Eastern Sand Darter are described in Section 2.7.5 (Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat).

Using the best available information, critical habitat has been identified for Eastern Sand Darter populations in the following locations:

- Sydenham River,

- Thames River,

- Grand River,

- Big Creek (Norfolk County); and,

- Long Point Bay (Lake Erie).

In the future, with new information, additional areas could be identified and/or additional information may be obtained to allow further clarification about the functional descriptions. Areas of critical habitat identified at some locations may overlap with critical habitat identified for other co-occurring species at risk; however, the specific habitat requirements within these areas may vary by species.

The areas delineated on the following maps (Figures 4-8) represent the area within which critical habitat is found or extent for the above mentioned populations. Using the bounding box approach, critical habitat is not comprised of all areas within the identified boundaries, but only those areas where the specified biophysical features/attributes occur for one or more life stages of the Eastern Sand Darter (refer to Table 10). Note that existing permanent anthropogenic features that may be present within the areas delineated (e.g., marinas) are specifically excluded from the critical habitat description; it is understood that maintenance or replacement of these features may be required at times. Brief explanations for the areas identified as critical habitat are provided below.

Sydenham River: The area within which critical habitat is found in the east branch of the Sydenham River includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present. This represents a stretch of river approximately 155 km long from Strathroy downstream to Walpole Island/Lake St. Clair. However, there may be limited suitable habitat for Eastern Sand Darter downstream of Dawn Mills (Figure 4). The critical habitat geospatial limit extends to the high water mark which is defined as the usual or average level to which a body of water rises at its highest point and remains for sufficient time so as to change the characteristics of the land. In flowing waters (rivers, streams) this refers to the active channel/bankfull which is often the 1:2 year flood flow return level, which plays an essential role in maintaining channel forming flows and clean sand substrates.

Figure 4. Area within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Sand Darter in the Sydenham River

Description of Figure 4

Thames River - The area within which critical habitat is found in the Thames River includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present. This represents a stretch of river approximately 148 km long between Komoka and Kent Bridge (Figure 5). The critical habitat geospatial limit extends to the high water mark which is defined as the usual or average level to which a body of water rises at its highest point and remains for sufficient time so as to change the characteristics of the land. In flowing waters (rivers, streams) this refers to the active channel/bankfull which is often the 1:2 year flood flow return level, which plays an essential role in maintaining channel forming flows and clean sand substrates.

Figure 5. Area within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Sand Darter in the Thames River

Description of Figure 5

Grand River - The area within which critical habitat is found in the Grand River includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present. This represents a stretch of river approximately 107 km long.from Paris downstream to upstream of Dunnville (Figure 6). The critical habitat geospatial limit extends to the high water mark which is defined as the usual or average level to which a body of water rises at its highest point and remains for sufficient time so as to change the characteristics of the land. In flowing waters (rivers, streams) this refers to the active channel/bankfull which is often the 1:2 year flood flow return level, which plays an essential role in maintaining channel forming flows and clean sand substrates.

Figure 6. Area within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Sand Darter in the Grand River

Description of Figure 6

Big Creek (Norfolk County) - The area within which critical habitat is found in Big Creek includes all contiguous ALIS segments from the uppermost stream segment with the species present to the lowermost stream segment with the species present. This represents a stretch of river approximately 17 km long from upstream of Spring Arbour, downstream to the start of the wetland at Big Creek National Wildlife Area (Figure 7). The critical habitat geospatial limit extends to the high water mark which is defined as the usual or average level to which a body of water rises at its highest point and remains for sufficient time so as to change the characteristics of the land. In flowing waters (rivers, streams) this refers to the active channel/bankfull which is often the 1:2 year flood flow return level, which plays an essential role in maintaining channel forming flows and clean sand substrates.

Figure 7. Area within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Sand Darter in Big Creek

Description of Figure 7

Long Point Bay (Lake Erie) - The area within which critical habitat is found in Long Point Bay includes the contiguous waters of the Inner Bay and the tip, from the shore down to the 3 m contour (Figure 8). The 3 m contour was used as occupied habitats were found only within this area. This represents a total area of approximately 167 km2 . Critical habitat extends up to the HWM elevation for Lake Erie at 174.62 m above sea level (International Great Lakes Datum, 1985).

Figure 8. Area within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Sand Darter in Long Point Bay (Lake Erie)

Description of Figure 8

These identifications of critical habitat ensure that currently occupied habitat within the Sydenham, Thames, Grand, Big Creek (Norfolk County), and Long Point Bay is protected, until such time as critical habitat for the species is further refined according to the schedule of studies (Section 2.7.5 below). The schedule of studies outlines activities necessary to refine the current critical habitat descriptions at confirmed extant locations, but will also apply to new locations should new locations with established populations be confirmed. Critical habitat descriptions will be refined as additional information becomes available to support or inform the population and distribution objectives.

2.7.4.1 Population viability

Comparisons were made with the extent of critical habitat identified for each population relative to the estimated minimum area for population viability (MAPV); refer to Table 11. It should be noted that for some populations, it is likely that only a portion of the habitat within that identified as the critical habitat extent would meet the functional habitat requirements of the species' various life-stages. In addition, since these populations occur in areas of degraded habitat (MAPV assumes habitat quality is optimal), areas larger than the MAPV may be required to support an MVP. Future studies may help quantify the amount and quality of habitat that meets the function, features or attributes within geospatial areas for all populations; such information, along with the verification of the MAPV model, will allow greater certainty for the determination of population viability. As such, the results below are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution.

| PopulationFootnote 3 | Area within which critical habitat is found | MAPV area | MAPV achieved? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sydenham River | 4.9 km2 (154 km of river) | 0.147 km2 | Yes |

| Thames River | 3.1 km2 (148 km of river) | 0.147 km2 | Yes |

| Grand River | 11.9 km2 (107 km of river) | 0.147 km2 | Yes |

| Big Creek | 0.3 km2 (18 km of river) | 0.147 km2 | Yes |

| Long Point Bay | 167 km2 | 0.147 km2 | Yes |

* The MAPV estimation is based on modeling approaches described above. This table is preliminary as further studies are needed to quantify the amount and quality of habitat within the currently identified critical habitat area.

This recovery strategy includes an identification of critical habitat to the extent possible, based on the best available information. Further studies are required to refine critical habitat identified for the Eastern Sand Darter to support the population and distribution objectives for the species. The activities in Table 12 are not exhaustive and it is likely that the process of investigating these actions will lead to the discovery of further knowledge gaps that need to be addressed.

| Description of activity | Rationale | Approximate timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct studies to determine the habitat requirements for all life-stages. | There is little known about YOY and juvenile habitat requirements and spawning has never been observed in the wild. Determining habitat requirements for each life-stage will ensure that all types of critical habitat for this species will be identified. | 2011-2014 |

| Survey and map habitat quality and quantity within historical and current sites, as well as sites adjacent to currently occupied habitat. | Strengthen confidence in data used to determine if sites meet the criteria to identify critical habitat; monitor current sites for changes in habitat that may result in changes to critical habitat identification; surveying adjacent habitat ensures accuracy of area of occurrence, on which critical habitat is being partly defined.. | 2011-2014 |

| Conduct additional species surveys to fill in distribution gaps, and to aid in determining population connectivity. | Additional populations and corresponding critical habitat may be required to meet the population and distribution objectives. | 2011-2014 |

| Create a population-habitat supply model for each life-stage. | Will aid in developing recovery targets and determining the amount of critical habitat required by each life-stage to meet these targets. | 2014-2016 |

| Based on information gathered, review population and distribution goals. Determine amount and configuration of critical habitat required to achieve goal if adequate information exists. Validate model. | Once the information above is gathered, recovery targets should be reviewed to ensure that they are still achievable and logical. Determining the amount and configuration of critical habitat based on recovery targets will be required for the Action Plan. | 2014-2016 |

Activities identified in this schedule of studies will be carried out through collaboration between DFO, relevant ecosystem recovery teams, and other relevant groups and land managers.

The definition of destruction is interpreted in the following manner:

Under SARA, critical habitat must be legally protected from destruction once it is identified. This will be accomplished through a s.58 Order, which will prohibit the destruction of the identified critical habitat.

Activities that ultimately increase siltation/turbidity levels and/or result in the decrease of water quality or cause direct habitat modification can negatively impact Eastern Sand Darter habitat.Without appropriate mitigation, direct destruction of habitat may result from work or activities such as those identified in Table 13.

The activities described in this table are neither exhaustive nor exclusive and have been guided by the threats described in Section 1.5. The inclusion of an activity does not result in its automatic prohibition since it is destruction of critical habitat that is prohibited. Furthermore, the exclusion of an activity does not preclude, or fetter the department's ability to regulate it pursuant to SARA. Since habitat use is often temporal in nature, every activity is assessed on a case-by-case basis and site-specific mitigation is applied where it is reliable and available. In every case, where information is available, thresholds and limits are associated with attributes to better inform management and regulatory decision-making. However, in many cases the knowledge of a species and its critical habitat may be lacking and in particular, information associated with a species or habitats thresholds of tolerance to disturbance from human activities, is lacking and must be acquired.

| Activity | Affect- pathway | Function affected | Feature affected | Attribute affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat modifications: Dredging Grading Excavation Placement of material or structures in water (e.g., groynes, piers, infilling, partial infills, jetties, etc.) Shoreline hardening |

Changes in bathymetry and shoreline morphology caused by dredging and near-shore grading and excavation can remove (or cover) preferred substrates, change water depths, change flow patterns potentially affecting nutrient levels and water temperatures. Placing material or structures in water reduces habitat availability (e.g., the footprint of the infill or structure is lost). Placing of fill can cover preferred substrates. Changing shoreline morphology can result in altered flow patterns, change sediment depositional areas, reduce oxygenation of substrates, cause erosion and alter turbidity levels. These changes can promote aquatic plant growth and cause changes to nutrient levels. Hardening of shorelines can reduce organic inputs into the water and alter water temperatures potentially affecting the availability of prey for this species. |

Spawning Nursery Feeding Cover (fossorial behaviour) |

Reaches of streams and rivers with sand substrates Sandy shoals, bars and beaches in lakes Shallow pools and bays |

|

| Habitat modifications: Water extraction Change in timing, duration and frequency of flow |

Water extraction can affect surface water levels and flow and groundwater inputs into streams and rivers affecting habitat availability, the oxygenation of substrates and prey abundance. Altered flow patterns can affect sediment deposition (e.g., changing preferred substrates), oxygenation of substrates and prey abundance. |

All (same as above) | reaches of streams and rivers with sand substrates |

|

| Habitat modifications: Unfettered livestock access to waterbodies Grazing of livestock and ploughing to water's edge |

Resulting damage to shorelines, banks and watercourse bottoms from unfettered access by livestock can cause increased erosion and sedimentation, affecting substrate oxygenation and water temperatures. Such access can also increase organic nutrient inputs into the water causing nutrient loading and potentially promoting algal blooms and decreasing prey abundance. |

All (same as above) | reaches of streams and rivers with sand substrates |

|

| Toxic compounds: Over application or misuse of herbicides and pesticides Release of urban and industrial pollution into habitat |

Introduction of toxic compounds into habitat used by this species can change water chemistry affecting habitat availability or use and cause increased aquatic plant growth affecting spawning and recruitment success. | Spawning Nursery Feeding |

All (same as above) |

|

| Nutrient loadings: Over-application of fertilizer and improper nutrient management (e.g., organic debris management, wastewater management, animal waste, septic systems and municipal sewage) |

Improper nutrient management can cause nutrient loading of nearby waterbodies. Elevated nutrient levels can cause increased aquatic plant growth changing water temperatures and slowly change preferred flows and substrates. Oxygen levels in substrates can also be negatively affected. | Spawning Nursery Feeding Cover (fossorial behaviour |

All (same as above) |

|

| Siltation and turbidity: Altered flow regimes causing erosion and changing sediment transport (e.g., tiling of agricultural drainage systems, removal of riparian zones, etc.) Work in or around water with improper sediment and erosion control (e.g., overland runoff from ploughed fields, use of industrial equipment, cleaning or maintenance of bridges or other structures, etc.) |

Improper sediment and erosion control or mitigation can cause increased turbidity levels, changing preferred substrates and their oxygen levels, potentially reducing feeding success or prey availability, impacting the growth of aquatic vegetation and possibly excluding fish from habitat due to physiological impacts of sediment in the water (e.g., gill irritation). Also see: Habitat Modifications: Change in timing, duration and frequency of flow. |

All (same as above) | All (same as above) |

|

| Riparian vegetation removal: mechanical removal |

Removal of riparian vegetation can cause erosion and increase turbidity, ultimately affecting preferred substrates and oxygenation of substrates. Water temperatures can also be negatively affected by removal of riparian vegetation and water velocities can be increased during high water events. | All (same as above) | All (same as above) |

|

As set out in subsection 83(4) of SARA, a person can engage in an otherwise prohibited activity if the activity is permitted by a recovery strategy and the person is authorized under an Act of Parliament to engage in that activity. Section 83(4) can be used as an exemption to allow activities, which have been determined to not jeopardize the survival or recovery of the species.

Continuation of limited commercial baitfish harvesting

Commercial baitfish harvesting is regulated by the Province of Ontario through the Ontario Fishery Regulations of the Fisheries Act. Eastern Sand Darter is not a legal baitfish. As outlined in the threats section (Section 1.5), under incidental harvest, commercial baitfish harvesting exploitation activities are unlikely to affect Eastern Sand Darter populations and have been determined to be eligible for an exemption as per s83(4). The management of Eastern Sand Darter recovery could include limited fishing mortality as the threat to Eastern Sand Darter by baitfish harvest is low. Although exempt from SARA, provincial legislation still applies. Baitfish harvesters must also comply with conditions of their baitfish licence.

Under s. 83(4) of SARA, this recovery strategy allows fishers to engage in the activities of commercial and sportfishing for baitfish that incidentally kill, harm, harass, capture or take Eastern Sand Darter, subject to the following two conditions:

- The fishing activities are conducted under licenses issued under the Ontario Fishery Regulations, 2007.

- All Eastern Sand Darter caught are to be released immediately and returned to the place from where taken in a manner that causes them the least harm.

Habitat of the Eastern Sand Darter receives general protection from the harmful consequences of works or undertakings under the habitat provisions of the federal Fisheries Act. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) also considers the impacts of projects on all listed wildlife species and their critical habitat. During the CEAA review of a project, all adverse effects of the project on a listed species and its critical habitat must be identified. If the project is carried out, measures must be taken that are consistent with applicable recovery strategies or action plans to avoid or lessen those effects (mitigation measures) and to monitor those effects. Once identified, SARA includes provisions to prevent the destruction of critical habitat of the Eastern Sand Darter.

Provincially, the Eastern Sand Darter is currently listed as Endangered under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007. The species was reassessed and listed as Endangered in 2010 and the habitat of the Eastern Sand Darter is also protected. Protection is also afforded under the Planning Act. Planning authorities are required to be “consistent with” the provincial Policy Statement under Section 3 of Ontario's Planning Act which prohibits development and site alteration in the habitat of Endangered and Threatened species. The Conservation Authority Act requires review of projects which could result in the development, interference with wetlands and alterations to shorelines and watercourses. A majority of the land adjacent to the rivers inhabited by the Eastern Sand Darter is privately owned; however, the river bottom is generally owned by the Crown. Under the Public Lands Act, a permit may be required for work in the water and along the shore.

The recovery team will continue to review priorities and direct efforts to improve and protect habitat through the recommended recovery approaches.

Eastern Sand Darter habitat is shared by many other species, including multiple species at risk. These include not only aquatic species but also a number of amphibians, turtles and birds. Specifically, the Round Hickorynut may benefit directly as the Eastern Sand Darter is a potential fish host for its glochidia (Clarke 1981). The distribution of Eastern Sand Darter overlaps with the Threatened Spiny Softshell Turtle in Ontario. Nesting habitats of these turtles have been found to occur on the inside of river bends, downstream of eroding slopes (Dextrase et al. 2003). Therefore, improvements to Eastern Sand Darter habitat will likely benefit the Spiny Softshell Turtle. Some of the proposed recovery activities will benefit the environment in general and are expected to positively affect other sympatric native species. There could be consequences to those species whose requirements may differ from those of Eastern Sand Darter. Consequently, it is important that habitat management activities for the Eastern Sand Darter be considered from an ecosystem perspective through the development, with input from responsible jurisdictions, of multi-species plans, ecosystem-based recovery programs or area management plans that take into account the needs of multiple species, including other species at risk.

Many of the stewardship and habitat improvement activities to benefit the Eastern Sand Darter may be implemented through existing ecosystem-based recovery programs that have already taken into account the needs of other species at risk.

The recovery team recommends a dual approach to recovery implementation that combines an ecosystem-based approach with a single-species focus. This will be accomplished by working closely with existing ecosystem recovery teams to combine efficiencies and share knowledge on recovery initiatives. There are currently four aquatic ecosystem-based recovery strategies (Thames River, Sydenham River, Grand River and Essex-Erie region) being implemented that address several populations of Eastern Sand Darter. Eastern Sand Darter populations that occur outside the boundaries of existing ecosystem-based recovery programs can use a single-species approach to recovery that will facilitate implementation of recovery actions within these watersheds through partnerships with local watershed management and stewardship agencies. If ecosystem-based recovery initiatives are developed in the future for these watersheds, the present single-species strategy will provide a strong foundation to build upon.

Action plans are documents that describe the activities designed to achieve the recovery goals and objectives identified in recovery strategies. Under SARA, an action plan provides the detailed recovery planning that supports the strategic direction set out in the recovery strategy for the species. The plan outlines what needs to be done to achieve the recovery goals and objectives identified in the recovery strategy, including the measures to be taken to address the threats and monitor the recovery of the species, as well as the measures to protect critical habitat. Action plans offer an opportunity to involve many interests in working together to find creative solutions to recovery challenges. As such, they may also include recommendations on individuals and groups that should be involved in carrying out the proposed activities.

One or more actions plans relating to this recovery strategy for Ontario populations will be produced within 5 years of the final recovery strategy being posted to the SARA registry. These may include multi-species or ecosystem based action plans.