Federal Tobacco Control Strategy 2001-2011- Horizontal Evaluation

Final Report

June 2012

Table of Contents

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Background on tobacco control in Canada

- 3.0 Federal Tobacco Control Strategy

- 3.1 FTCS Governance

- 3.2 FTCS Budget History

- 3.3 FTCS Activities

- 4.0 The FTCS Evaluation

- 5.0 Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 6.0 Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 6.1 Overall and Youth Prevalence

- 6.1.1 Smoking Prevalence Trends

- 6.1.2 Overall Prevalence

- 6.1.3 Youth Prevalence

- 6.1.4 Overall and Youth Prevalence Summary

- 6.2 Second-Hand Smoke Exposure

- 6.2.1 Recent Trends

- 6.2.2 Second-Hand Smoke Summary

- 6.3 World Health Organization (WHO) - the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)

- 6.4 The Next Generation of Tobacco Control Policy

- 6.5 Monitor and Assess Contraband Tobacco Activities and Enhance Compliance

- 6.6 Efficiency and Economy

- 6.1 Overall and Youth Prevalence

- 7.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A -- Profile of Grant and Contribution Projects

- Appendix B -- Estimated Average Smoking-attributable Mortality by Difference Underlying Causes

Management Response and Action Plan

The Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) was launched in 2001 and was designed as a comprehensive, integrated and sustained approach to achieving reductions in tobacco usage led by Health Canada, in partnership with Public Safety Canada, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency, Canada Revenue Agency, and the Public Prosecutions Service of Canada.

This ten-year summative evaluation is the fourth evaluation of federal tobacco control efforts. It follows on the evaluations of the Tobacco Demand Reduction Strategy (TDRS - 1994-1997), the Tobacco Control Initiative (TCI - 1997-2001) and the mid-term evaluation of the FTCS (2001-2006).

Policy authority for the FTCS expired March 31, 2012. The Government of Canada is currently exploring new approaches to tobacco control. As such, the findings of this evaluation will be used to inform policy development on the future federal role in tobacco control.

Health Canada has reviewed the evaluation and generally agrees with the findings of the evaluation, however the Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate has expressed concerns about the manner in which the Tobacco Products Information Regulations (TPIR) are characterized, and potentially confusing assertions concerning health warning messages in relation to smoking cessation. The Management Action Plan outlines some actions that Health Canada will take in collaboration with other Federal Partner Departments, and makes general observations with regard to how the TPIR are characterized.

- CBSA Management Response:

The CBSA generally agrees with the findings of the evaluation. The CBSA will continue to work with Health Canada and federal partners to address tobacco control - Public Safety Canada Response:

Public Safety Canada accepts the findings of the evaluation report and supports its recommendations. Public Safety Canada will support Health Canada in implementing its management action plan, where applicable. - Royal Canadian Mounted Police Response:

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) accepts the findings of the evaluation report and supports its recommendations. The RCMP will support Health Canada in implementing its management action plan, where applicable. - Canada Revenue Agency Response:

The CRA generally agrees with the findings of the evaluation and will continue to work with Health Canada and federal partners to address tobacco control. - Public Prosecution Service of Canada Response:

The Public Prosecution Service of Canada generally agrees with the findings of the evaluation and will continue to work with Health Canada and federal partners to address tobacco control where applicable.

| Recommendations | Response & Action | Deliverables | Responsible Manager | Timelines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streamline tobacco activities to focus on administering the Tobacco Act, which contains the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act, and maintaining a leadership role through research and surveillance activities to inform policy and regulation as well as guide the direction of collaborative efforts to deliver a comprehensive and integrated national tobacco control strategy. | HC, in collaboration with the FTCS federal partner departments, are committed to implementing measures to reduce smoking rates and protect the health of Canadians.

The recommendation will be taken into consideration in the policy development process. |

Announcement of new tobacco program

Approval and implementation of a new tobacco program |

Director General of the Controlled Substance and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD), Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch (HECSB), Health Canada (HC) | June 2013 |

| Identify best/promising practices among the G&C projects and ensure this information is shared with relevant partners. | Management agrees with the need to glean as much learning as possible from the G&C projects that were implemented under the FTCS and to share these learnings with stakeholders and partners.

HC will conduct a review of all grants and contributions projects funded under the FTCS to identify promising practices and lessons learned. HC will share the findings from this review with stakeholders and partners. |

Completion of the review of grants and contributions funded projects to identify promising practices and lessons learned. | Director General of the Controlled Substance and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD), Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch (HECSB), Health Canada (HC) | March 2014 |

| Develop a systematic approach to performance measurement concentrating on linking the performance data to the logic model and performance indicators to guide the evaluation and reporting processes. | Management agrees with the need for a strong performance strategy to monitor and report on results, and to provide management with regular information for oversight and to ensure achievement of established objectives, outcomes and activities.

A performance measurement strategy will be developed aligning policy directions and outcomes to the future federal role of tobacco control. Implementation of the performance measurement including collection of identified indicators. |

Performance Measurement Strategy that is approved by Treasury Board Secretariat. | Director General, CSTD, HCSB, HC | October 2013 |

| An evaluation framework will be developed, building on the program performance measurement plan with input from the federal partners. | Evaluation Framework that meets TBS standards | Head of Evaluation, Director General, Evaluation Directorate PHAC | One year after program approval - December 2013 |

General Observations

The Federal Tobacco Control Strategy Horizontal Evaluation is intended to measure the objectives of the FTCS as a whole. One of the stated objectives is smoking cessation.

The Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD) is concerned that the report could be interpreted to suggest that the purpose of tobacco product package labels (required pursuant to the Tobacco Products Information Regulations - TPIR) pertains to smoking cessation.

The TPIR were made under the authority of the Tobacco Act. One of the purposes of this Act, as indicated in its section 4, is to enhance public awareness of the health hazards of using tobacco products. This same objective was mentioned in the regulatory impact analysis statement for the TPIR, published in the July 19, 2000 issue of the Canada Gazette, Part II. However, the report as drafted makes potentially confusing assertions concerning health warning messages in relation to smoking cessation.

In order to ensure that these issues are accurately addressed in future evaluations, CSTD staff will work collaboratively with the Evaluation Directorate to increase awareness and understanding of the Tobacco Act, the TPIR and other regulations.

Acronyms

- ADMO

- Assistant Deputy Minister's Office

- AMPS

- Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service

- BI

- Business Intelligence

- CAMH

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CCAT

- Canadian Coalition for Action on Tobacco

- CEPA

- Canadian Environmental Protection Act

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CSTD

- Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate

- CTUMS

- Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey

- DTIP

- Drugs and Tobacco Initiatives Program

- FCTC

- Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- FNITCS

- First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy

- FTCS

- Federal Tobacco Control Strategy

- G&C

- Grant and Contribution

- GST

- Goods and Services Tax

- GTA

- Greater Toronto Area

- HC

- Health Canada

- HECSB

- Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch

- HRSDC

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

- HWMs

- Health Warning Messages

- IAD

- International Affairs Directorate

- MACTC

- Ministerial Advisory Committee on Tobacco

- NAO

- National Aboriginal Organizations

- NAPS

- National Action Plan on Smuggling

- NFFE

- Niagara Falls Fort Erie

- NFRP

- National Fine Recovery Program

- NGOs

- Non-Government Organizations

- NSRTU

- National Strategy to Reduce Tobacco Use

- OPSP

- Office of Policy and Strategic Planning

- ORC

- Office of Regulations and Compliance

- OTRSE

- Office of Tobacco Research, Surveillance and Evaluation

- PAA

- Program Activity Architecture

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PPSC

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- PST

- Provincial Sales Tax

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

- RAPB

- Regions and Programs Branch

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RMAF

- Results-based Management and Accountability Framework

- SAF

- Smoking Attributable Fraction

- SAM

- Smoking-Attributable Morbidity

- SAMMEC

- Smoking-Attributable Morbidity, Mortality and Economic Costs

- SEP

- Safe Environments Program

- TCI

- Tobacco Control Initiative

- TCIMS

- Tobacco Control Information Monitoring System

- TCLC

- Tobacco Control Liaison Committee

- TCLC-WG

- Tobacco Control Liaison Committee Working Group

- TDRS

- Tobacco Demand Reduction Strategy

- TPCA

- Tobacco Products Control Act

- TPCR

- Tobacco Products Control Regulations

- TPIR

- Tobacco Products Information Regulations

- TRR

- Tobacco Reporting Regulations

- WHPSP

- Workplace Health & Public Safety Program

- YPLL

- Years of Potential Life Loss

- YSS

- Youth Smoking Survey

Executive Summary

This evaluation is intended to assess progress made towards the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy's (FTCS) objectives from 2001-2011 with a particular focus on the second half of the FTCS (2007-2011). It examines relevance and performance in order to fulfill accountability requirements outlined in the Government of Canada Policy on Evaluation. The evaluation has also attempted to take into account not only the external factors associated with outcome results but also the complex interactions of contributions from different levels of government where possible.

The FTCS was introduced as a ten-year strategy (2001-2011) intended to reduce tobacco-related disease and death in Canada. The FTCS was designed to be a comprehensive, integrated and sustained tobacco control program based on international best practices, with a focus on building upon previous federal initiatives to reduce tobacco demand.

A key component of Health Canada's (HC) tobacco control effort is the enforcement of the Tobacco Act adopted in 1997, and a range of regulations. The focus of the Tobacco Act is to regulate manufacturing, sale, labelling and promotion of tobacco products in Canada. It aims to protect all Canadians, with a particular focus on youth, from the health consequences of tobacco use.

A number of regulations have been made pursuant to the Tobacco Act, including the Tobacco Products Information Regulations (TPIR) that came into force in 2000, and the Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) that replaced for cigarettes and little cigars the TPIR requirements in 2011. Both require graphic health warning messages on tobacco products packaging. Tobacco products labelling is a key component of the federal's government efforts to inform Canadians on the health risks of tobacco use and the health benefits of quitting.

In 2001, almost $560M was allocated over for the first five years of the FTCS to engage in tobacco control activities including: mass media; development and enforcement of regulations pursuant to the Tobacco Act; research and surveillance; national co-ordination of tobacco control efforts; collaboration with federal partners to monitor contraband tobacco; support for First Nations and Inuit tobacco reduction programs; and funding various activities through Grants and Contributions (G&Cs).

The Terms and Conditions for the FTCS were renewed in 2007. While the monies for federal partners remained the same at approximately $16M annually, a much smaller amount than previous years was allocated to HC's tobacco control activities (approx. $57M annually). Therefore, the total allocation for the second phase of the FTCS was $285M for HC and $80M to federal partners over five years.

The 2006 FTCS summative evaluation noted that almost all of the objectives set in 2001 were met or exceeded by 2005. However, there were limitations in the extent to which this success could be attributed to the FTCS. In the context of having achieved its initial objectives, objectives for the FTCS were revised for its second phase and an overarching goal of reducing Canadian smoking prevalence from 19% to 12% by 2011 was set as a stretch target. Objectives for the FTCS in 2001 and revised specific objectives for the second phase of the FTCS are summarized as follows:

| Phase 1 - 2001 | Phase 2 - 2007 |

|---|---|

| Reduce smoking prevalence to 20% from 25% in 1999 | Reduce overall smoking prevalence from 19% (2006) to 12% by 2011 |

| Reduce the number of cigarettes sold by 30% | Reduce the prevalence of smoking among youth from 15% to 9% |

| Increase retailer compliance regarding youth access to sales from 69% to 80% | Increase the number of adults (including young adults) who quit smoking by 1.5 M |

| Reduce the number of people exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in enclosed public spaces | Reduce the prevalence of Canadians exposed to daily second-hand smoke from 28% to 20% |

| Explore how to mandate changes to tobacco products to reduce hazards to health | Examine the next generation of tobacco control policy in Canada |

| Contribute to the global implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO) - Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) | |

| Monitor and assess contraband tobacco activities and enhance compliance |

The FTCS terms and conditions were renewed in 2007, at which time, HC's functions with respect to surveillance, research, regulations, and compliance remained similar to those described in 2001. However, emphasis on compliance shifted from retailers to manufacturers, and intelligence gathering with respect to the industry. Policy functions also remained similar, but additional focus was placed on international activities and examining the next generation of tobacco control, via the inclusion of objectives reflecting these activities. Mass media was not identified as part of the FTCS in 2007.

Governance

HC was responsible for the overall management and implementation of the FTCS. The Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD) within the Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch (HECSB) of HC was the lead directorate. It relied on other areas within the Department which either provided direct control over various aspects of the FTCS or provided support and expertise.

Between 2008 and 2010 two major changes in the governance structure were undertaken - the creation of the Regions and Programs Branch (RAPB) and the merging of the tobacco and controlled substances programs. The creation of RAPB resulted in the transfer of all functions related to G&Cs as well as other program delivery components to the Drugs and Tobacco Initiatives Program (DTIP) within this Branch. Compliance and enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act in the regions were also transferred to RAPB. Other FTCS activities continued under HECSB.

The objective concerning contraband tobacco as well as the objective with respect to the World Health Organization - Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO-FCTC) relies on many federal departments including Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), Public Safety Canada (PS), Department of Justice (DoJ), Department of Foreign Trade and International Development (DFAIT), Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) as well as Health Canada.

The FTCS places a strong emphasis on partnerships between the federal government and other levels of government. Given that tobacco control is a multi-jurisdictional activity, collaboration is necessary not only with other levels of government but also with many non-government organizations to achieve common goals.

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

The evaluation examined the Government of Canada's core evaluation issues of relevance and performance. The relevance assessment focused on questions related to the continued need for the FTCS, the Strategy's alignment with federal roles and responsibilities as well as alignment with government priorities. Performance was evaluated by examining the achievement of the FTCS objectives and an analysis yielding estimated returns on investment (ROIs).

The methodology for this evaluation of the ten-year FTCS (2001-2011) used multiple lines of evidence including a literature and document review, econometric modeling, secondary data analysis, key informant interviews and a stakeholder survey. It also used both the process and impact evaluations previously conducted to assess the Grant & Contribution (G&C) Program component of the FTCS. These methods were employed to provide quantitative and qualitative data and confirm findings where appropriate. In addition, data collected over the course of the evaluation process was validated through informal interviews with FTCS program personnel.

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

Smoking prevalence rates in Canada have declined significantly over the past decade and are among the lowest in developed countries. There has also been an increased involvement of the provinces and territories in tobacco control. By 2007, all provinces had Acts which enhanced what was once only federal legislation concerning tobacco control. In addition, provincial and territorial expenditures on tobacco control strategies have more than doubled since 2001.

Nonetheless, there still seems to be a perceived need among stakeholders for continued efforts on the part of the federal government to sustain work on tobacco control. Stakeholders believe that the main role for the federal government is a leadership role responsible for coordination at the national and international level which would include developing national frameworks, legislation and regulations.

Despite the fact that current federal priorities do not highlight tobacco control as a main federal focus, the Government of Canada still has the responsibility to administer the Tobacco Act (amended in 2009 as part of the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act) and its regulations.

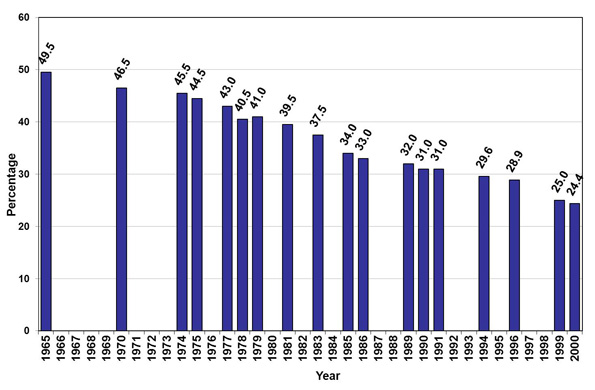

Performance

Overall smoking rates, which have been steadily declining since the 1960s, continued to decline since the introduction of the FTCS in 2001. According to the Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS), overall smoking rates, which include daily and occasional smokers, declined from 21.7% in 2001 to 16.7% in 2010. However, the stretch target of a reduction in overall smoking prevalence to 12% by 2011 was not met. That said, the current daily smoking prevalence rate is 13% and is the lowest of comparable countries. In addition to reaching a new low for adult prevalence, the target of a 9% prevalence rate in the youth population was achieved; however, there has not been a statistically significant change since 2007. Nevertheless, even with these reduced prevalence rates, the rate of decline has slowed considerably since 2007.

The FTCS made a small contribution to the decline in smoking prevalence through its labelling and youth access regulations as well as its support to implement provincial second-hand smoke bans. Even though retailer and manufacturer compliance was reported as high, making statements about the contribution of other FTCS regulations to the declining smoking rates was difficult due to the limitations of the econometric model and the conflicting findings from other lines of evidence. According to the econometric modelling conducted as part of this evaluation, external influences outside of the FTCS (i.e., level of education achieved, followed by provincial and excise tax) were found to be the most significant predictors of both smoking participation and consumption. Retail display bans as well as the legal age in which cigarettes can be purchased were also predictors of smoking participation.

Although some of the contribution cessation projects demonstrated high quit rates in the impact evaluation of G&C projects, due to the limited participation in and reach of these interventions combined with very limited outcome data, generalizations about the effectiveness of these projects in reducing prevalence were not possible. However, other G&C projects that focused on knowledge application were able to demonstrate some influence with respect to policy/legislation development as evidenced by the implementation of provincial second-hand smoke bans, pan-Canadian quitlines and the Canadian Action Network for the Advanced Dissemination and Adoption of Practice informed Tobacco Treatment (CAN-ADAPTT) smoking cessation guidelines. In addition, funded projects related to policy and knowledge exchange were able to support and inform policy at federal, provincial and organizational levels.

The objective of reducing second-hand smoke exposure to Canadians was achieved. HC promoted smoke-free environments through its contribution funding, mass media campaigns as well as its leadership role in the implementation of smoking bans via both informational and monetary resources. The implementation of second-hand smoke bans across most provinces is an illustration of how the federal government can influence change.

Through the FTCS, HC, along with its other partner departments, assisted with fulfilling Canada's commitment to participate in the WHO-FCTC by being a contributor to the development of the FCTC and providing technical advice on both the original Articles and ongoing support for their global implementation. This participation in the FCTC illustrated that international leadership is being provided by the Government of Canada.

Over the course of the FTCS, research and surveillance activities appeared to be active functions and used to inform the development of legislation, regulations and various policies and positions. Furthermore, G&C projects as well as work with stakeholders were important to the advancement of the next generation of tobacco control policy, both federally and provincially.

Knowledge generation and translation was a predominant characteristic of the FTCS. Investments were made to ensure the continued generation of knowledge that will assist with developing additional policy work in the future. Overall, it appeared that knowledge generation and its subsequent application helped to regulate tobacco in Canada, educated jurisdictions in Canada on emerging issues as well as guided the direction of collaborative efforts in tobacco control.

PS, CBSA and RCMP used FTCS funding to monitor and assess contraband tobacco activities which may have contributed to the significant increase in the volume of seizures observed between 2001 and 2009. Also, the evaluation found that there was an increased capacity through additional staffing to conduct intelligence analysis. Given that the objective was to simply monitor and assess the market to inform tax policy, the volume of seizures does indicate that monitoring activity has taken place and information in the form of intelligence reports and departmental meetings was provided to Finance Canada to inform tax policy. CRA demonstrated compliance-related activity through the increased number of audits and reviews while the PPSC demonstrated such activity through increases in fine recoveries, both with increased staffing. How this impacted the availability of legal or illegal tobacco products could not be determined.

The estimated total annual expected economic benefit of all tobacco control measures in place in Canada is $1.8B. The analysis revealed that if the FTCS made a contribution of approximately 5% to reduction in smoking prevalence, then the annual ROI (i.e., return on investment) would be estimated at $17M. On the other hand, if the FTCS contribution was assumed to be higher than 5%, the ROI would also be higher.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While the duration of the FTCS (2001-2011) has seen large declines in smoking prevalence, between 2007 and 2010 prevalence remained relatively stable. The overall prevalence objective for Phase 2 was a stretch target set at 12% in light of the early accomplishment of the original objectives in Phase 1 of the FTCS. Nonetheless, this goal of reducing prevalence to 12% was not met. However the target of reducing youth smoking prevalence to 9% was met.

Overall, the FTCS contributed to the decline in smoking prevalence through its labelling and youth access regulations as well as its support to implement provincial second-hand smoke bans. However, lines of evidence suggested that external measures not funded by the FTCS, such as level of education achieved and taxation, were the main contributors to changes in prevalence with provincially-legislated retail display bans and legal age for purchasing tobacco products following.

Most large-scale environmental changes (i.e., tax and second-hand smoke bans) were implemented between 2001 and 2007 and since that time there was little change in the Canadian tobacco control environment. Changes made by the provinces in tobacco control during this period included restrictions on point of sale advertising via provincial retail display bans, province-wide second-hand smoke bans and provincial smoke-free vehicle legislation. With the increase in action from provinces and territories, many tobacco control issues are now addressed at a provincial/territorial level, and prevention or cessation programming is increasingly conducted at this level.

The only major changes at the federal level were the passage of the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act that amended the Tobacco Act in 2009 and the new health-related labels prescribed under the new Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) made in 2011. The impact of these amendments to the Tobacco Act on prevalence could not be assessed in this evaluation as these amendments did not come into effect until late 2009 for some provisions and mid-2010 for others.

The evaluation illustrated compliance with Tobacco Act and its regulations was stable and high, while smokers' participation in cessation programming provided by G&C projects participating in the G&C Impact Evaluation was limited. Additionally, the data available was not able to determine the overall impact of the cessation projects funded by the G&C projects on prevalence - not surprisingly seeing as many of the cessation projects were aimed at vulnerable populations and were only intended to contribute to a reduction in smoking prevalence rates. Evidence from this evaluation and the stabilizing of prevalence rates, indicates that smoking cessation success in the current smoker population will be limited unless G&C projects are able to improve project participation and reach.

Other G&C projects that focussed on knowledge application demonstrated some influence in providing information which was applied to policy/legislation development. In addition, funded projects related to policy and knowledge exchange were able to support and inform policy at the federal, provincial and organizational levels.

Federal leadership was evident throughout the evaluation including HC's role in the WHO-FCTC, the implementation of second-hand smoke bans, the research and surveillance available on smoking in Canada, the research conducted to facilitate the provincial retail display bans, as well as the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act that amended the Tobacco Act. Continued leadership in tobacco control requires continued investment in research and surveillance to identify emerging tobacco issues and to be able to respond to them through stakeholder relations or policy activities.

The objective related to contraband tobacco was to simply monitor and assess the market and to enhance compliance in order to inform policy. Therefore, the increased volume of seizures indicated that monitoring contraband tobacco had taken place and the increased number of audits and regulatory reviews as well as fines recovered indicated that there has been enhanced compliance-related activity.

Considering the findings and conclusions of the evaluation and the current tobacco control environment, the FTCS, as it is presently structured, may need to be streamlined. Nonetheless, there still seems to be a need for sustained efforts on the part of the federal government in tobacco control not only to administer the Tobacco Act and its regulations but also to provide a leadership role responsible for coordination at the national and international level. In order to deliver a comprehensive and integrated national tobacco control strategy, identified as a best practice, the strategic approach of combining federal regulations, policy development, research and surveillance as well as supporting provincial and international tobacco control efforts is necessary.

The evaluation approach for the FTCS used sophisticated simulation modeling as one line of evidence in order to provide quantitative performance data which was intended to be corroborated by a performance measurement system that would provide both qualitative and further quantitative data. However, as mentioned in the methodology section of this report, the performance measurement system was not implemented for various reasons. During the evaluation report writing process, it became evident that data gaps existed. Therefore, an ad-hoc internal document review was performed to try to capture retrospective qualitative data to fill these gaps. Although a substantial amount of information was captured through the internal document review process, there were still some areas where triangulation with multiple lines of evidence was impossible. It also became evident that the FTCS has an abundance of performance data; however, it is not well organized/tracked according to the program outcomes and associated performance indicators. Lastly, other lines of evidence (such as the econometric modelling and literature review) concentrated on tobacco control in Canada more broadly (which would include activities initiated by P/Ts, NGOs and municipalities) instead of specifically on the activities of the FTCS which are the responsibility of the federal government.

Therefore the recommendations stemming from the evaluation are to, under the leadership of HC:

- Streamline tobacco activities to focus on administering the Tobacco Act (as amended as part of the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act) and its regulations, and maintaining a leadership role through research and surveillance activities to inform policy and regulation, as well as guide the direction of collaborative efforts to deliver a comprehensive and integrated national tobacco control strategy.

- Identify best/promising practices amongst the G&C projects and ensure this information is shared with relevant partners.

- Develop a systematic approach to performance measurement, concentrating on linking the performance data to the logic model and performance indicators to guide the evaluation and reporting processes.

1.0 Introduction

A commitment was made for Health Canada (HC) to conduct an evaluation of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) in fiscal year 2010-2011 and to return to Cabinet by the Fall of 2011 to present a path forward for tobacco control using the evaluation results as one line of evidence to inform the Cabinet process. This evaluation is in keeping with the 2009 Government of Canada's Policy on Evaluation by examining all five core issues falling under relevance and performance. Additionally, this report addresses FTCS activities and accomplishments between 2001 and 2011, but with a particular focus on 2007-2010, as a summative evaluation of the Strategy was completed in 2006. Overall conclusions and recommendations are presented in the final section of this report.

2.0 Background on Tobacco Control in Canada

The Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (referred to as either the FTCS or the Strategy throughout the report) was announced in 2001 as a comprehensive tobacco strategy, led by HC, to reduce disease and death due to tobacco use. This Strategy followed a lengthy history of tobacco control activities undertaken by the federal government since the 1960s.

The types of tobacco activities, including interventions by the Government of Canada over different time periods, went through a gradual shift from tobacco-related (mostly research) activities to tobacco control interventions, which became more comprehensive over time. Publicly visible intervention measures began with public education (1963-1964) which later evolved into health promotion or 'social marketing' programming (1980s to 2000s), combined with initially voluntary restrictions on some commercial activities by tobacco companies. These negotiated changes to marketing activities, began briefly in 1971-1972 under the threat of proposed legislation, eventuated in a more concerted policy development process beginning in the early 1980s that culminated in the enactment of the former Tobacco Products Control Act, S.C. 1988 c.20.

The strategic approach combining legislation, regulation and health promotion began in 1986 with the National Strategy to Reduce Tobacco Use (NSRTU roughly 1986-1993), which obtained its funds from internal reallocation from the drug program. This was the first tobacco strategy and was followed by: the Tobacco Demand Reduction Strategy (1994-1997), the Tobacco Control Initiative (1997-2001) which was announced concurrently with the Anti-Smuggling Initiative, then the FTCS (2001-2011).

The Tobacco Demand Reduction Strategy (TDRS) was part of the National Action Plan on Smuggling (NAPS) launched by the federal government on February 8, 1994. The timing of this initiative was designed to correspond to a series of tobacco taxation roll-backs, prompted by increasing prevalence of contraband tobacco. The Strategy was to last until March 31, 1997, and its objective was, through programs, public education and enforcement, to minimize the anticipated negative impact of tax cuts on the consumption of tobacco products, particularly in those groups most likely to initiate or increase tobacco use as a result of lower prices. HC was assigned the responsibility for implementing the Strategy. A total of $104M was spent under the TDRS over the three-year period.

The Tobacco Control Initiative (TCI) was introduced by the federal government in 1997-1998 with a budget of $50M. These resources were allocated over five years ending in March 2002 for work related to regulations and compliance. An ongoing funding stream of $10M per year was added in 1998-1999 for a public education component. A policy case was subsequently made to incorporate the ongoing stream of funding into the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS), which replaced the TCI in 2001.

The FTCS covers the majority of tobacco control activities undertaken by the federal government, but is not representative of all of the activities which affect the use, impact or availability of tobacco products. The following departments undertake activities that are not funded through FTCS but are related to tobacco:

- Department of Finance is responsible for taxation of tobacco products;

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) holds the Non-Smokers Health Act;

- Public Health Agency of Canada conducts some healthy living interventions that may include prevention and cessation messages; and

- Agriculture Canada addresses the farming of tobacco and runs a program to help farmers transition from growing tobacco.

3.0 Federal Tobacco Control Strategy

Following the TCI, the FTCS was introduced as a ten-year strategy (2001-2011, and extended one year) intended to reduce tobacco-related disease and death in Canada. The FTCS was designed to be a comprehensive, integrated and sustained tobacco control program based on international best practices, with a focus on building upon the work of previous federal initiatives.

A key component of HC's tobacco control effort is the enforcement of the Tobacco Act adopted in 1997, and a range of regulations. The focus of the Tobacco Act is to regulate manufacturing, sale, labelling and promotion of tobacco products in Canada. It aims to protect all Canadians, with a particular focus on youth, from the health consequences of tobacco use.

A number of regulations have been made pursuant to the Tobacco Act, including the Tobacco Products Information Regulations (TPIR) that came into force in 2000, and the Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) that replaced for cigarettes and little cigars the TPIR requirements in 2011. Both require graphic health warning messages on tobacco products packaging. Tobacco products labelling is a key component of the federal's government efforts to inform Canadians on the health risks of tobacco use and the health benefits of quitting.

It is worth noting that in 2007, the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Attorney General) v. JTI-Macdonald Corp., [2007] 2 S.C.R. 610, concluded that both the Tobacco Act and the TPIR were constitutional in their entirety.

The government's rationale for increasing its investments in tobacco control was based on the need for comprehensive action to address the diversity of complex issues associated with tobacco use. Evidence from California's Tobacco Control Program and research by the Center for Disease Control in the United States, noted that independent actions, even when well funded, do not work or have little benefit, especially over the long term.

In 2001, almost $560M was allocated for the first five years of the FTCS to engage in tobacco control activities including: mass media; development and enforcement of regulations pursuant to the Tobacco Act; research and surveillance; national co-ordination of tobacco control efforts; collaboration with federal partners to monitor the problem of contraband; support for First Nations and Inuit tobacco reduction programs; and funding various activities through G&Cs.

The FTCS terms and conditions were renewed in 2007 and while the monies for federal partners remained the same at approximately $16M annually, a much smaller amount from previous years was allocated to HC's tobacco control activities ($57M annually). Therefore, the total allocation for the second phase of the FTCS was approximately $285M for HC and $80M to federal partners.

The first formal evaluation of the FTCS, conducted in 2006, noted that almost all of the objectives set in 2001 were met or exceeded by 2005. However, there were limitations in the extent to which this success could be attributed to the FTCS. In the context of having achieved its initial objectives, objectives for the FTCS were revised for the second phase of the FTCS and an overarching goal of reducing Canadian smoking prevalence from 19% to 12% by 2011 was set as a stretch target. Objectives for the FTCS in 2001 and revised specific objectives for the second phase of the FTCS are summarized in the table below:

| Phase 1 - 2001 | Phase 2 - 2007 |

|---|---|

| Reduce smoking prevalence to 20% from 25% in 1999 | Reduce overall smoking prevalence from 19% (2006) to 12% by 2011 |

| Reduce the number of cigarettes sold by 30% | Reduce the prevalence of smoking among youth from 15% to 9% |

| Increase retailer compliance regarding youth access to sales from 69% to 80% | Increase the number of adults (including young adults) who quit smoking by 1.5 M |

| Reduce the number of people exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in enclosed public spaces | Reduce the prevalence of Canadians exposed to daily second-hand smoke from 28% to 20% |

| Explore how to mandate changes to tobacco products to reduce hazards to health | Examine the next generation of tobacco control policy in Canada |

| Contribute to the global implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO) - Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) | |

| Monitor and assess contraband tobacco activities and enhance compliance |

The FTCS terms and conditions were renewed in 2007, at which time HC's functions with respect to surveillance, research, legislation and regulations, and compliance remained similar to those in 2001. However, emphasis in compliance shifted from retailers to manufacturers, and intelligence gathering with respect to the industry. Policy functions also remained similar, but additional focus was placed on international activities and examining the next generation of tobacco control, via the inclusion of objectives reflecting these activities. Mass media was not identified as part of the FTCS in 2007.

Although raising awareness about the health risks associated with tobacco is still a goal for the government, the 2007 Strategy indicated that prevention, cessation and education interventions should be aimed at changing smoking behaviours and determining what interventions are effective in impacting behaviour change. Another important change in activity and funding was the cancellation of the First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy. Further, while not explicitly stated, defence of the Tobacco Act against litigation emerged as a funding pressure.

3.1 FTCS Governance

Health Canada

HC was the lead department in the FTCS and was responsible for the overall management and implementation of the Strategy. There were two Branches within HC that had direct responsibility for the Tobacco Control Strategy; however, they may have relied on other areas within the department for support and expertise in areas of potential overlap. The Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD) within the HECSB was the lead area within HC.

When the FTCS terms and conditions were renewed in 2007, governance structures had largely remained stable within HC. Functions and offices were very similar to those in place in 2001, but after 2007, more substantial change was seen in HC. Between 2008 and 2010 two major changes in the governance structure were undertaken - the creation of the Regions and Programs Branch (RAPB) and the merging of the tobacco and controlled substances programs.

The creation of RAPB resulted in the transfer of all functions related to G&Cs as well as other program delivery components to the Drugs and Tobacco Initiatives Program (DTIP) with this Branch. Compliance and enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act in the regions were also transferred to RAPB. Other FTCS activities continued under the HECSB. FTCS functions were further divided within RAPB, with the G&C activities located in the Programs Directorate, and compliance and enforcement activities in the Regions. HECSB retained governance of compliance and enforcement with RAPB regional delivery of the regional component.

Following the reorganization of HECSB and RAPB, HC made a decision to amalgamate the HC functions that were part of Canada Drug Strategy, and later the National Anti-Drug Strategy with those of the FTCS. In 2009 a new organization was thus created, titled the Controlled Substances and Tobacco Directorate (CSTD). Previously the "Tobacco Control Directorate" was responsible for leading Health Canada's activities, and it was this Directorate that was merged with the Directorate responsible for controlled substances. With these organizational changes the FTCS remained under the Program Activity Architecture (PAA) of "Substance Use and Abuse" and "Tobacco" sub-activity.

The Office of Regulations and Compliance (ORC) of CSTD was responsible for monitoring the compliance and enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act and undertook the modification of existing or development of new regulations under the Act. Also some enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act were transferred from ORC to the Regions group within RAPB.

Partnership under the FTCS was demonstrated through strong linkages not only across federal departments but also between the Government of Canada and provincial, territorial and municipal governments. The Strategy was further strengthened through close collaboration with the private and voluntary sectors and, internationally, with the world community. This approach recognizes that responsibility for tobacco control is shared and that tobacco use remains a significant and ongoing health challenge that requires sustained commitment of resources and attention from all tobacco control partners.

Within HC, there were a number of other partners that supported the FTCS besides CSTD of HECSB and the RAPB in order to continue tobacco control efforts in Aboriginal communities, in the international world, and with provinces and territories. This coordinated effort requires involvement from the following partners:

First Nations Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB)

HECSB and RAPB worked with FNIHB on an ongoing basis in order to ensure coordination and consistency of HC's tobacco control activities. With the cancellation of the First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy in 2006, some G&C projects targeted on-reserve First Nations and Inuit living in Inuit communities. RAPB continued to work closely with FNIHB as well as First Nations and Inuit health organizations to identify priorities in support of tobacco programming.

International Affairs Directorate (IAD)

CSTD and RAPB worked with the International Affairs Directorate of HC to develop Canada's contributions to international tobacco control initiatives - e.g. the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).

Tobacco Control Liaison Committee (TCLC)

The Director General of the CSTD was the co-chair of the TCLC. The Tobacco Control Liaison Committee was a group of federal/provincial/territorial government representatives that met twice a year to fulfill the following mandates:

- Provide a forum for collaboration between federal, provincial and territorial governments on elements of the New Directions for Tobacco Control in Canada - A National Strategy;

- Develop and monitor progress on a work plan for joint action related to elements of the Strategy;

- Bring forward issues of importance and provide advice to the Advisory Committee on Population Health and Health Security (ACPHHS), which advises the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health;

- Integrate tobacco control within the broader population and public health agenda, territorially, provincially and nationally; and

- Facilitate continued collaboration with non-governmental organizations active in tobacco control.

Ministerial Advisory Council on Tobacco Control (MACTC)

The MACTC was active beginning in 2001, but had not met since the fall of 2005. The Council provided advice on the strategies, policies, mechanisms and activities required for the effective implementation of the FTCS and for federal support to the National Strategy endorsed by the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers of Health as well as Non-Government Organizations. The Council also monitored and evaluated tobacco control activities undertaken in Canada and in other jurisdictions.

Other Federal Partners

The objective of monitoring and assessing the contraband market and enhanced compliance relied on other federal departments. The monitoring and assessment of the contraband tobacco activities was the responsibility of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Public Safety Canada (PS); whereas the enhanced compliance aspect of this objective was the responsibility of the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) and Canada Revenue Agency (CRA).

Other Jurisdictions

The FTCS placed a strong emphasis on partnerships between the federal government and other levels of government. Given that tobacco control is a multi-jurisdictional activity, collaboration is necessary not only with other levels of government but also with many non-government organizations to achieve common goals.

3.2 FTCS Budget History

In 2001, the FTCS had funding of almost $560M for the first five years. Steady funding of approximately $16M annually was allocated to federal partners for contraband surveillance and monitoring, while the annual budget for HC ramped up from $54.5M a year to $99.2M by 2004-2005. Additionally, $10M in ongoing funding from the previous Tobacco Control Initiative was provided.

In 2007, while the monies for federal partners remained the same at approximately $16M annually, a much smaller amount from previous years ($57M annually) was allocated to HC's tobacco control activities. Therefore, the total allocation for the second phase of the FTCS was approximately $285M for HC and $80M to federal partners.

Health Canada Allocation

The reduction in FTCS monies for HC during the second half of the FTCS was primarily the result of major permanent reductions, and the decision to discontinue the First Nations and Inuit Tobacco Control Strategy as part of the 2006 Expenditure Review (see table below).

| Funds | Total |

|---|---|

| TCI Total | $10,000,000 |

| FTCS Total for HC | $99,800,000 |

| Total For Health Canada | $109,800,000 |

| CEPA | $-13,000,000 |

| PCO Advertising Fund | $-16,488,217 |

| FNIHB reduction | $-12,278,000 |

| Government Reallocations | $-8,224,706 |

| HC Reallocations | $-3,821,570 |

| Collective Agreement Funding | $1,488,483 |

| Technical ARLU Adjustments | $118,721 |

| EBP ARLU Adjustments | $-272,411 |

| Total Remainder for Health Canada | $57,322,300 |

This decrease in funding reduced the HC allocation under the FTCS to approximately $57M annually. Since 2007-2008, HC's FTCS funding experienced further departmental reallocations ($0.2M) and government reductions ($3.3M), resulting in a funding level of $53M by 2011. Other large deductions, transfers and lapses also occurred.

In the first year of the FTCS, there was a $4.3M transfer to the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). In the second year there was a $3.1M transfer to the Safe Environments Program's Water Bureau re-allocation (SEP), an $8.7M lapse in the third year, and a $12.7M branch reallocation in the fourth. Each year major transfers, deductions or lapses occurred and this is not limited to the early years of the FTCS. There were several elections/prorogation that created delays in funding approvals particularly in the second phase of the Strategy causing lapses to occur. In 2008-2009 $6.3M was transferred to FNIHB and $2.5M lapsed in 2009-2010.

In addition to lapses and transfers, a significant proportion of funding was required to support corporate costs. For example, in 2009-2010 "Corporate Branches" were allocated $3.8M, $1M was identified as supporting "Enterprise IT", $0.8M was transferred to cover a series of "Corporate Reductions". An annual permanent reduction of $2.8M was applied to the FTCS to support Branch-level function.

These corporate and departmental deductions of $8.5M impacted the amount of funding available for direct tobacco control activities. Spending on tobacco control activities for 2010-2011 totalled less than $45M, including litigation at $6.3M.

It should be noted that in the second half of the FTCS, litigation emerged as a funding pressure. The Government of Canada was named as a third party by tobacco companies in several court cases, and a number of other cases were identified as potential future risks, thus an Office for Tobacco Litigation Support was created as part of the CSTD. Financial support for litigation activities was initially taken from unspent G&C dollars - a delay in approval for the FTCS terms and conditions in 2007-2008 resulted in a significant surplus of funds that fiscal year. Funding to address litigation costs was approved in 2008-2009, but it was noted that additional funds, of approximately $3M per year would be provided from the FTCS budget to support litigation. In years where litigation costs exceeded this funding allocation and the $3M from the FTCS, additional funds were redirected from the FTCS. For example, in 2010-2011 approximately $6.1M in litigation funding was supported by the FTCS.

Federal Partners Funding

The approximately $16M allocation to federal partners for contraband-related activities did not change in Phase 2 of the FTCS, and was allocated as follows:

| Federal Partners | Allocation |

|---|---|

| PS | $610,000 |

| PPSC | $1,988,000 |

| CRA | $888,910 |

| CBSA | $10,560,800 |

| RCMP | $1,723,480 |

| Total | $15,771,190 |

| Note: There is a small discrepancy in the above numbers and those reported by PPSC | |

FTCS funds allocated to federal partners were identified for enhancing compliance with the federal tobacco tax legislation as well as monitoring and surveillance, but these departments conduct additional activities with respect to tobacco. FTCS allocated dollars are used in combination with departmentally held funds to undertake comprehensive activities related to contraband tobacco and ensure that legal tobacco market complies with federal tobacco tax laws.

3.3 FTCS Activities

Activities in Phase 2 of the Strategy were similar to those undertaken since 2001, with notable exceptions of the removal of mass media, and support for the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). It was noted that the focus of the Strategy would be to concentrate efforts on developing and testing cessation and prevention techniques and approaches and from retail compliance to industry/manufacturer level compliance and enforcement. The various FTCS activities are described in the following sections.

The Tobacco Act and Associated Regulations

Adopted in 1997, the federal Tobacco Act regulates the manufacture, sale, labelling and promotion of tobacco products in Canada. The Tobacco Act aims to protect all Canadians with a particular emphasis on youth from the health consequences of tobacco use.

Section 4 of the Tobacco Act defines the purpose of the Act which serves:

- To protect the health of Canadians in light of conclusive evidence implicating tobacco use in the incidence of numerous debilitating and fatal diseases;

- To protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them;

- To protect the health of young persons by restricting access to tobacco products; and

- To enhance public awareness of the health hazards of using tobacco products.

The Tobacco Act also imposes restrictions and prohibitions and provides authorities to regulate in key areas to support the established purposes:

Tobacco Products, including standards and information reporting

The Tobacco Reporting Regulations (TRR), adopted in June 2000, require manufacturers and importers to submit to the Minister of Health detailed reports on their tobacco products, including information on product composition and their emissions, information on sales, product packaging, research projects undertaken by or on behalf of a manufacturer, among other information.

Prohibition on sales to youth

The Tobacco Act prohibits the sale of tobacco products to persons less than 18 years of age and requires retailers of tobacco products to post signs that inform the public that providing tobacco products to young persons is prohibited by law. The Tobacco (Access) Regulations specify the place, manner, form and content of signs to be posted in retail outlets. The regulations also set out the documentation that may be used to verify the age of the person purchasing tobacco products.

Health-Related Labelling of tobacco products (except for cigarettes and little cigars), including Health Warning Messages

The Tobacco Products Information Regulations (TPIR) made in 2000 under the authority of the Tobacco Act provide the requirements for the health warning messages, health information messages and toxic emissions information that must be displayed on every packages of various tobacco products (except for cigarettes and little cigars since 2011). These health-related labels were made to increase awareness of the health hazards and health effects associated with tobacco use.

Health-Related Labelling of Cigarettes and Little Cigars, including Health Warning Messages

The Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars), made in 2011, replace the labelling requirements for cigarettes and little cigars that were previously enshrined in the Tobacco Products Information Regulations (TPIR) by new messages that are more memorable, noticeable and engaging. These Regulations also include a pan-Canadian toll-free quitline number and cessation Website portal to be displayed on all health warning messages and on some health information messages. These Regulations build on the achievements of the TPIR while aiming to improve its overall effectiveness. However, they were not examined as part of this evaluation as they have only come into effect recently and therefore effectiveness cannot be assessed.

Promotion, Prohibited Terms

The Promotion of Tobacco Products and Accessories Regulations (Prohibited Terms), made in 2011, prohibit the use of the terms "light" and "mild", and variations thereof, from various tobacco products, their packaging, promotions, retail displays, as well as from tobacco accessories. Again, given that this regulation was put into place in 2011, it will not be examined as part of this evaluation.

Promotion, including at retail and other forms of promotion

Advertising tobacco products is permitted under the Tobacco Act only if it is "information" or "brand-preference" advertising that is in a publication provided by mail and addressed to an adult or in signs in a place where young persons are not permitted by law. In this regard, the restrictions on promotion of tobacco products are aimed at limiting exposure of individuals and youth to tobacco advertising, strictly restricting "lifestyle" or "appealing to young persons" type of advertising. With some exceptions, foreign publications and broadcasts are exempt from these restrictions to disseminate promotion that is prohibited by the Tobacco Act.

Seizure of tobacco products

The Tobacco Act contains enforcement powers that can be employed by designated inspectors. Where an inspector seizes a tobacco product or other product, its owner may apply to a court for a restoration of the seized product. The restoration procedure under the Tobacco Act is outlined in the Seizure and Restoration Regulations.

As part of the FTCS, the Office of Regulations and Compliance (ORC) was responsible for managing compliance and enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act and its regulations, undertaking some compliance and enforcement actions, as well as developing new regulations or updating existing regulations under the Act. Also some enforcement activities related to the Tobacco Act were transferred from ORC to the Regions group within RAPB.

Research

The Office of Tobacco Research, Surveillance and Evaluation (OTRSE) in HECSB was directly linked to the functional activity area of Research and Policy Development. Most of the work done in this Office contributed to the objective of examining the future of tobacco control. The major activities of OTRSE were divided across three portfolios: surveillance, evaluation and research, and business intelligence.

Surveillance (CTUMS, YSS)

OTRSE undertook a number of monitoring and surveillance activities in support of the FTCS which included surveillance of the smoking behaviour of Canadians, retailer compliance with youth access regulations, and public opinions. More specifically, surveillance activities include (while not being limited to) the annual Canadian Tobacco Monitoring Survey (CTUMS) and the bi-annual Youth Smoking Survey (YSS) (more detail is provided in the methodology section under secondary data analysis).

Evaluation and Research (Bio-Monitoring)

The OTRSE conducted scientific research related to smoking and tobacco to support the development of regulations, policies and programs, and the dissemination of information. The bulk of this work involved bio-monitoring projects as well as additional research related to tobacco product science.

Business Intelligence

As per Phase 2 of the Strategy, the OTRSE established a Business Intelligence (BI) unit in November 2008. The primary focus of the unit was to ensure a thorough analysis of information submitted by the industry to HC.

Policy

The Office of Policy and Strategic Planning (OPSP), HECSB led the policy development for the FTCS and was identified as the Office of Primary Interest for the Government of Canada planning and reporting requirements for the FTCS. Between 2007 and 2010, the main functions of the tobacco policy group involved: policy development, international work on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), and stakeholders relations.

Policy Development

The key activities of OPSP since 2007 have been the development of the amendments to the Tobacco Act as part of the Cracking Down on Tobacco Marketing Aimed at Youth Act; support for the renewal of the Health Warning Messages (the new Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) made in 2011); the evaluation of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy; and the development of options for the future federal role in tobacco control.

International Activities on the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)

The FCTC is an international tobacco control instrument under the World Health Organization (WHO) which was developed in response to the globalization of the tobacco epidemic and asserts the importance of demand reduction strategies as well as supply issues. A number of federal partners and other departments were involved in the interdepartmental coordination and preparation of negotiating positions, including: Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency, and Canada Revenue Agency. HC was involved given the health focus of the FCTC and concern over the public health impact of contraband tobacco products.

Stakeholder Relations

HC had many partners under the FTCS, including federal partners, provinces and territories, and non-governmental organizations. HC was responsible for managing relationships with these groups and chairing a number of working groups held as part of the FTCS.

Programming

G&Cs

G&Cs under the FTCS were funding mechanisms through which the federal government supported non-government organizations and other levels of government in conducting tobacco control activities.

Under the FTCS, funding for G&C projects was available under three broad categories:

- Knowledge Development Projects - smaller projects aimed at researching, designing and testing a service where the focus of the evaluation was on measuring project outcomes.

- Knowledge Application Projects - the majority of G&C funded projects were expected to be Knowledge Application Projects. The objective of these projects was to change the smoking behaviour of Canadians by increasing the number of people who quit or try to quit smoking, reducing the number of people who start smoking, and increasing action on second-hand smoke.

- Knowledge Transfer Projects - the focus of these projects was to accelerate the transfer and adoption of the service by other government or non-governmental organizations that are better positioned to impact behaviour.

Appendix A is a summary of the G&C projects that were funded by the FTCS. Many of these projects focused on "knowledge application", in particular smoking cessation. Consistent with the emphasis on cessation, 72% of the projects targeted smokers. Of that smoker community, many projects targeted sub-groups identified as vulnerable populations such as, mental health clients, youth and the Aboriginal community (both on and off reserve). Projects also targeted other populations, such as: health practitioners (36% of projects); the tobacco control community, e.g., policy makers, researchers, (22%); non-smokers (18%); or other groups (e.g., families, employers) (12%). Twenty-eight percent of the contribution projects had a client group consisting of aboriginal on-reserve and 26% of funding allocated was for aboriginal off-reserve groups. Projects were rolled out to experiment with different or new interventions or test techniques on new target groups.

Public Education

RAPB provided a comprehensive range of information and resources on tobacco use, cessation, prevention and protection to various audiences such as youth, adults, workplaces, pregnant women as well as the First Nations and Inuit population.

Contraband Tobacco

Activities related to the FTCS objective concerning the monitoring and assessment of contraband tobacco were the responsibility of several partner departments - i.e. Public Safety Canada (PS); Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA); and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Whereas the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) and Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) were responsible for enhancing compliance to ensure that the legal tobacco market complies with federal tobacco tax laws thereby ensuring that there is no diversion to the contraband market. FTCS funding was used to increase departments' capacity, mainly through increased staffing to conduct intelligence analysis and inform policy-makers.

National Mass Media

In 2001, resources were sought for mass media in the amounts of $30M in 2001-2002, $40M in 2002-2003 and 2003-2004, and $50 M annually thereafter. These amounts were reduced significantly and during the second half of the FTCS (2007 to 2011), mass media campaigns were discontinued. To date, national mass media campaigns have utilized a budget of $100.8M for media, research and production purposes since fiscal 2001-2002. Additionally, a regional mass media contribution funding program was in place in 2001 and then reallocated by 2007.

First Nations Tobacco Control Program

In addition to the main objectives of the first half of the FTCS (2001-2006), a major focus of the FTCS was to target First Nations on-reserve communities south of 60°, and Inuit and all First Nations communities north of 60° where smoking prevalence was high. The First Nations Tobacco Control Program was discontinued by HC in 2007.

4.0 The FTCS Evaluation

4.1 Purpose of the Evaluation, Scope and Considerations

This evaluation planned to assess progress made towards the FTCS objectives. It addressed the core issues of relevance and performance in order to fulfill accountability requirements outlined in the Government of Canada Policy on Evaluation. The evaluation questions related to the core issues of relevance and performance are outlined in the table below.

A previous evaluation of the FTCS was conducted in 2006. Therefore, this current evaluation examined the ten years of the Strategy from 2001-2011 but had a specific focus on the second half of the FTCS (2007-2011). The evaluation also attempted to take into account not only the external factors associated with outcome results but also the complex interactions, of or contributions from, different levels of government where possible. Additionally, the evaluation was intended to be used as one line of evidence in the program renewal process.

| Evaluation Issue | Evaluation Questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance | |

| Is there a continued need for the FTCS? | |

| Are the FTCS activities and objectives aligned with the federal roles and responsibilities? | |

| Is the FTCS aligned with government priorities? | |

| Performance | |

| Effectiveness | To what extent has the FTCS been able to meet its objectives? |

| Which activities have had the greatest impact? | |

| Efficiency and Economy | What are the economic impact of smoking and the benefits of reducing smoking? |

| What is the return on investment for the FTCS? | |

Evaluation Approach

The Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF) developed in 2007, called for a four step evaluation approach intended to provide an analysis of relevance and performance.

The 2007 RMAF also referred to the development of a model which was expected to be used to determine value for money. This would have provided decision makers with precise quantitative estimates on long-term health and economic benefits directly attributable to the FTCS. Two research streams were necessary to support the simulation:

- An econometric model was required to examine the impact of various social, demographic and economic variables as well as the impact of various interventions which could be or not funded under the FTCS. Additional details will be provided later on in the methods section; and

- A micro level analysis of the effectiveness of the FTCS interventions (including FTCS G&C funded projects and legislation/regulations) was also required to support the simulation approach.

Cumulatively the results from these two streams were needed to assess with more accuracy the effectiveness of the FTCS. Limited progress in addressing existing data gaps prevented the population-level simulation modelling from providing the precise quantitative estimates on long-term health and economic benefits directly attributable to the FTCS that were hoped to be achieved.

To address the evaluation questions identified in the RMAF as well as support the evaluation core issues as required under the current Government of Canada Policy on Evaluation, the current evaluation strategy focused primarily on macro-level econometric and population-level modeling, supported by micro-level data from evaluation reports of Grant and Contribution projects, public opinion research and interviews with key stakeholders as well as validation interviews.

4.2 Methodology

This section describes the methods used in the evaluation of the FTCS (2001-2011). Multiple lines of evidence including a literature and document review, econometric modeling, secondary data analysis, key informant interviews and a stakeholder survey were employed to provide quantitative and qualitative data and confirm findings where appropriate. In addition, data collected over the course of the evaluation process was validated through informal interviews with FTCS Program personnel. The following is a description of the key lines of evidence.

Econometric Modeling

The purpose of the Econometric Modeling study was to provide an econometric analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies in Canada on smoking prevalence and quantity smoked. The model assessed the impact of both federal (FTCS and non-FTCS policy tools) and provincial, territorial and municipal interventions including: taxes on tobacco products (Department of Finance); second-hand smoke bans (P/Ts); retail display bans (P/Ts); retailer compliance with bans on sales to minors (FTCS); health warning messages (FTCS); legal age for smoking (FTCS and P/Ts); HC tobacco control expenditures. In addition to tobacco control policy variables, the model also included demographic variables (e.g., level of education, income, marital status).

Following Gagné and Gagné and TeddsFootnote 1, a two-part model using CTUMS data was selected for the analysis and modeling. This two-part model consisted of estimating:

- participation was defined as the probability that an individual smokes; and

- consumption was defined as the number of cigarettes a smoker smokes in a given period of time.

Separate participation and consumption (for smokers) estimates were generated for youth, for adults, and for workers, with youth being defined as those who have not reached legal age for smoking in their province.

This two part model is an easily implementable model that has been used in previous researchFootnote 2 and that does not rely on exclusion restrictions to adjust for potential selection bias because the consumption equation focuses on smokers rather than on the whole population.Footnote 3

For both youth and adults, estimates were generated for three different models which will later in the report be referred to as:

- Model I – Includes observations from 1999 to 2009. This model does not control for provinces and time, therefore unlike Model II, this model does not account for the influence of unobserved variables.

- Model II – Controls are included for provinces and time so this model accounts for unobserved heterogeneity however, it is more likely to represent short- rather than long-term effects, which is problematic in the context of an addiction.

- Model III – Same as Model I but only includes observations for 2001 to 2009. As for Model I, this model does not account for the influence of unobserved variables.

Review of Documents

A number of documents were reviewed to provide background information on the FTCS activities, the governance structure as well as contribute to the evaluation findings sections on relevance and performance. This included internal documents such as government documents, annual reports, internal memos and the 2006 summative evaluation of the FTCS. Additional documents were reviewed as part of efforts to assess FTCS relevance. These documents included major government priority setting documents: Speeches from the Throne and the Budgets (including the Budget Speeches and Budget Plans). Additionally, a review of communications from the Prime Minister of Canada was conducted.

Process Evaluation of Grant and Contribution Projects (2011)

Results from the 2011 Process Evaluation of G&C Projects were used as a line of evidence in the current evaluation of the FTCS. The process evaluation was conducted to examine G&C project roll-out, challenges and barriers, progress accomplished and lessons learned. Expected results as described in project proposals and Quarterly Progress Reports for all G&C projects funded by the FTCS were analyzed and summarized. Based on a review of the expected results and descriptions of the projects, the contribution projects were organized according to seven categories or project clusters: Helplines, Ottawa Model, Counselling, Policy and Knowledge Exchange, Training, Workplace-based, and School-based. Analysing projects by cluster facilitated the identification of lessons learned, best practices and challenges specific to each cluster of projects. The process evaluation examined the key objectives, activities and planned outputs; the financial status; the partnerships; the successes; and the challenges and barriers associated with the 104 G&C funded projects. The conduct of the process evaluation entailed a detailed content analysis of project proposals, project progress reports and final project reports completed by March 2011.

Impact Evaluation of Grant and Contribution Projects (2010)

This study was intended to evaluate the effectiveness of a sample of G&C projects launched by FTCS for fiscal years 2007-2008 to 2009-2010 that could be evaluated through an experimental design (i.e., through the use of a comparison group) which proved not to be possible and thus, a quasi-experimental design was implemented instead. The number of participants (n= 655 of 1051 at baseline) were drawn from a total of 17 funded projects. Because the number of participants in projects was much lower than expected, a census survey of project participants consenting to the Impact Evaluation, was conducted (not a sample as originally envisioned). This also explains why an experimental design approach could not be implemented for the 2010 Impact Evaluation of G&C Projects.

The design of the survey instruments was based on the objectives of the impact evaluation, and drew heavily from existing questionnaires on tobacco behaviour (e.g., CTUMS). The baseline survey was designed to be administered primarily by interviewers over the telephone and was approximately 20 minutes in length. The survey was re-administered to each participant at 3-months, 6-months and 12-months after completion of the baseline survey. The questionnaireFootnote 4 addressed issues such as:

- smoking history (e.g., age started smoking);

- current smoking behaviour (e.g., smoking behaviour in last seven days, last 30 days);

- household smoking restrictions;

- prior quit attempts;