Archived - Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch’s Health Planning and Quality Management Activities - 2010-2011 to 2014-2015

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 532 KB, 63 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Type: Audit

Date published: 2017-02-24

Prepared by Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

September 26, 2016

List of Acronyms

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AFN

- Assembly of First Nations

- APS

- Aboriginal Peoples Survey

- CA

- Contribution Agreement

- CBRT

- Community-based Reporting Tool

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CCOH

- Chiefs Committee on Health

- CPMS

- Community Planning and Management System

- DG

- Director General

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FNIGC

- First Nations Information Governance Centre

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- GCIMS

- Grants and Contributions Information Management System

- HPQM

- Health Planning and Quality Management

- INAC

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- ITK

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- MCCS

- Management Contract and Contribution System

- MOU

- Memoranda of Understanding

- NAOs

- National Aboriginal Organizations

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PMF

- Performance Measurement Framework

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RHS

- Regional Health Survey

- SMC

- Senior Management Committee

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan (or Management Response)

- 1.0 Evaluation Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 - Continued Need for the Program

- 4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 - Alignment with Government Priorities

- 4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 - Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 4.4 Performance: Issue #4 - Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

- 4.5 Performance: Issue #5 - Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency

- 5.0 Conclusions

- 6.0 Recommendations

- Appendix 1 - Funding Models

- Appendix 2 - Logic Model

- Appendix 3 - Evaluation Description

- Appendix 4 - Actual Spending by Program Component

- Appendix 5 - Summary of Findings

List of Tables

Executive Summary

This Health Planning and Quality Management (HPQM) Activities evaluation reviewed program activities for the period from April 2010 to March 2015. The evaluation was undertaken in fulfillment of the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016).

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance (effectiveness, economy and efficiency) of the HPQM cluster of activities across four components: health planning (governance), accreditation, health consultation/liaison, and health research. The evaluation findings will support decision-making for policy and program improvements.

A number of other program areas in the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) contribute to increasing health programs and services capacity in First Nations and Inuit communities; however these were out of scope of this evaluation as they will be or have recently been evaluated separately. As well, British Columbia projects were excluded due to the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance. Further, the funding for the Northern Wellness Agreement self-governance and land claims were excluded. The evaluation scope included Inuit under the health consultation/liaison component only.

The methodology used in the evaluation included key informant interviews with FNIHB national and regional staff, representatives from national Aboriginal organizations, staff from federal departments or agencies with linked mandates, and academic issue experts. Surveys were conducted with FNIHB regional liaison staff and First Nations community health leaders. Case studies examined health planning activities in five First Nations on-reserve communities. Data collection also included document and literature reviews, and financial data and performance data reviews.

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) were consulted during the scoping phase and for the development of the evaluation methodology and tools, including the survey questionnaires and key informant interview guides. They were also consulted on preliminary findings and the draft final report.

Program Description

The Health Planning and Quality Management program administers contribution agreements and direct departmental spending to support capacity development for First Nations and Inuit communities. Key services supporting program delivery include: the development and delivery of health programs and services through program planning and management; on-going health system improvement via accreditation; the evaluation of health programs; and, support for community development activities.

The program objective is to increase the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate, and deliver health programs and services.

The HPQM cluster includes the following four components:

- Health planning (governance) - supports on-reserve First Nations communities in the planning and development of health services and program delivery models

- Accreditation - promotes and supports the accreditation of on-reserve health services for ongoing health system improvement

- Health consultation/liaison - increases partnerships of national First Nations and Inuit organizations and governments to improve health outcomes

- Health research - enhances knowledge about First Nations health through funding research projects.

The only activities that addressed capacity for the Inuit were under the health consultation/liaison component though the Inuit have access to programming tools.

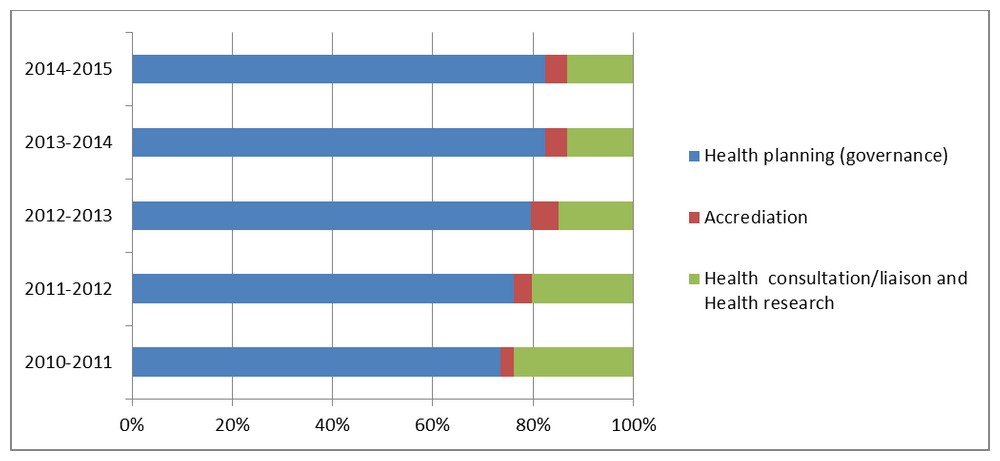

During the period between April 2010 and March 2015, HPQM expenditures totalled approximately $642 million. Of this amount, approximately 80% was expended through contribution agreements for the health planning (governance) in on-reserve First Nations communities, 4% was for contribution agreements for accreditation activities in on-reserve First Nations communities, and about 13% was the combined amount for contracts for health research and a contribution agreement each with AFN and ITK for health consultation/liaison.

Conclusions - relevance

Continued Need

There is a continued need for effective capacity building to reduce health inequalities in First Nations and Inuit communities. Greater ownership and control of health programs and services by First Nations and Inuit organizations and communities can lead to better health outcomes. Increased capacity and control can have a positive impact on First Nations and Inuit community health programs and services in four key areas, in turn leading to enhanced health outcomes. These four areas are: social determinants of health, cultural competency and safety, decentralization, and quality of services.

Alignment with Government Priorities

The HPQM priorities align with the Government of Canada and departmental current priorities and strategic outcomes. Various Government of Canada commitments support health programs and services by collaborating with First Nations and Inuit communities to ensure that health programs and services are accessible, reliable and of quality. Health Canada's departmental objectives and the FNIHB strategic plan support First Nations and Inuit self-determination, community-level action and capacity building, and building stronger stakeholder connections.

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Work in the area of capacity building for First Nations and Inuit organizations and communities is consistent with federal and Health Canada responsibilities outlined in various policies (e.g., Indian Health Policy, Indian Health Transfer Policy) aimed to increase First Nations and Inuit community control and responsibility for health service delivery. There is complementarity across federal-level departments with programs that support capacity building; however, there are opportunities for enhanced coordination of community planning activities.

Conclusions - performance

Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

Health consultation/liaison and health research activities have led to enhanced ownership and control for First Nations and Inuit organizations. Through contribution funding and engagement agreements with both AFN and ITK, there have been enhanced opportunities for national and regional First Nations and Inuit organizations to participate in the design and development of health programs and policies. FNIHB has developed strategic partnerships with federal and First Nations organizations to support various First Nations health related research and surveillance initiatives. The availability and use of evidence-based information has been enhanced. This information has been used to support decision-making both within FNIHB and by First Nations organizations. FNIHB national office and regional staff key informants indicated that further knowledge translation within FNIHB may enhance the use of evidence-based information in policy and program decision-making.

HPQM activities have positively impacted First Nation community capacity, which in turn has enhanced the quality of health programs and services in First Nations communities. There have been enhanced opportunities to exercise and build community ownership and control. The development of health plans and the accreditation process have effectively built capacity in those communities with existing leadership and organizational abilities. First Nations communities with varying levels of capacity require different approaches to maximize their opportunities to exercise ownership and control. Strengthened processes and tools in communities with lower initial levels of capacity are needed - in particular remote and isolated communities, smaller communities, as well as communities in crisis.

Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency

Some HPQM component activities have effectively built upon the expertise and capacity of First Nations organizations to enhance community ownership and control, including leveraging existing First Nations community capacity to undertake the accreditation process and working through the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) to support Regional Health Survey activities. A number of program efficiencies have been demonstrated through the use of funding formulas and work to enhance FNIHB cultural competency.

Efficiencies could be gained by further enhancing collaboration internally across FNIHB First Nation community-based programs and to some degree with other federal government departments. There are opportunities to enhance working relationships through sharing best practices, better integrating processes and tools, and supporting cultural competency.

A refined performance data collection approach may enhance how FNIHB is able to measure increased capacity and control and the quality of service being delivered.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Strengthen processes and tools to improve opportunities for all First Nations communities to develop the capacity to exercise ownership and control, particularly with those First Nations communities with lower initial levels of capacity.

First Nations communities with varying levels of capacity require different approaches to maximize their opportunities to exercise ownership and control. Challenges in terms of capacity are more likely to be found in remote and isolated communities, smaller communities, as well as communities in crisis. These challenges include: limited strategic planning underway, limited access to health planning funding, and difficulty attracting and retaining human resources in many remote and isolated communities. Tailored support to meet these unique capacity needs might include: additional training or tools, leveraging networks (mentoring) and best practices from other communities, partnering with other regional stakeholders, and ongoing community engagement with FNIHB regional liaison staff. A health planning guide was recently launched by FNIHB in order to assist those communities that would benefit most from greater capacity.

Recommendation 2

Enhance information exchange and collaboration on health planning and quality management activities across FNIHB programs and regional offices.

Enhanced collaboration across FNIHB would lead to a more integrated and culturally competent approach to First Nations and Inuit health service delivery across all regions and all community-based programs. For examples, there are opportunities to: integrate accreditation standards into other program guidance documents that support capacity in community programs, such as mental wellness and healthy living; undertake sharing of best practices on capacity building across the Branch, in particular at the working level and across regional offices; and continue to enhance the cultural competency of staff in various capacity building roles.

Recommendation 3

Update HPQM performance measurement strategy to establish methods to measure increased capacity and control and the quality of service being delivered.

An updated performance measurement strategy is needed to establish methods to measure increased capacity and control as well as the quality of services being delivered. Strategies to track and analyse immediate and intermediate outcome indicators (in particular related to ownership and control and the quality of health programs and services) are required.

Management Response and Action Plan (or Management Response)

Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch's Health Planning and Quality Management 2010-2011 to 2014-2015

| Recommendations - Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Response - Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Action Plan - Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Deliverables - Identify key deliverables | Expected Completion Date - Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Accountability - Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Resources - Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthen processes and tools to improve opportunities for all First Nations communities to develop the capacity to exercise ownership and control, particularly with those First Nations communities with lower initial levels of capacity. | Management agrees with the recommendation and continues to work with First Nations to develop tools to increase the capacity of First Nations and Inuit communities to design, manage, and deliver health programs and services.

The Health Planning Guide is a key capacity building tool intended for First Nations, Tribal Councils and other First Nations and Inuit organizations to provide guidance to First Nations communities in undertaking the health planning process or to revise an existing health plan. FNIHB has funded the First Nations Health Managers Association to develop a Health Services Accreditation Toolkit. The toolkit was completed in June 2016 and has been designed and developed with a focus on lower- to mid-capacity health services organizations and nursing stations that want to build capacity, improve the quality of the services they provide, and ultimately pursue the accreditation process. |

Health Canada will work with First Nation partners to review and update the current Health Planning Guide. | Revised Health Planning Guide. | April 2018 | Paula Hadden-Jokiel,Executive Director, CIAD | No additional resources are needed. |

| FNIHB HQ will work with regions to identify 15-20 health services organizations and nursing stations that would benefit most by increasing capacity and entering the accreditation process, and provide them with the Health Services Accreditation Toolkit. | Toolkits delivered to 15-20 First Nations organizations. | Disseminated to community level organizations by March 2017. | Robin Buckland, Executive Director | The cost of this item will be managed within the existing budget. | ||

| Enhance information exchange and collaboration on health planning and quality management activities across FNIHB programs and regional offices. | Management agrees with the recommendation and continues to work toward improving information exchange and collaboration to better support community planning that considers the full range of FNIHB's programs and services. To support this objective, the completion of the revisions to the Health Planning Guide will be completed through a collaborative process that involves First Nations partners, regional FNIHB employees and all programmatic areas of FNIHB. | Engage First Nations, Inuit and Regional partners to revise the Health Planning Guide. | All Terms of Reference, working groups, meeting minutes/record of decisions will be included up to December 2017. | December 2017 | Paula Hadden-Jokiel Executive Director CIAD |

No additional resources required. |

| Orientation materials for FNIHB programs/regions and First Nation stakeholders in the new Guide. | April 2018 | |||||

| Update HPQM performance measurement strategy to establish methods to measure increased capacity and control and quality of service being delivered. | Management agrees with the recommendation and is working towards improving the availability of and access to high quality data to support evidence-based decision making in policy, expenditure management and program improvements. | SPPI in partnership with HPQM representatives will work in collaboration with the Health Canada's Head of Performance Measurement and the Office of Audit and Evaluation to complete a performance information profile. | Completed performance information profile | March 2017 | Mary Kappelus Director General, SPPID |

No additional resources required. |

1.0 Evaluation Purpose

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) health planning and quality management (HPQM) activities, including the following components of this cluster: health planning (governance), accreditation, health consultation/liaison, and health research. The period covered by the evaluation was April 2010 to March 2015.

The evaluation was undertaken in fulfillment of the Financial Administration Act (FAA) and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016), and was conducted by the Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada's (the Agency) Office of Audit and Evaluation in accordance with the Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2015-2016 to 2019-2020. The evaluation will support Health Canada's Deputy Minister and senior management in decision-making for policy and program improvements.

2.0 Program Description

2.1 Program Context

Over the last three decades, federal government policy and programs have supported increasing the responsibility and control of First Nations and Inuit communities over their own health care. In 1979, the Government of Canada introduced its Indian Health Policy with a stated goal "…to achieve an increasing level of health in Indian communities, generated and maintained by the Indian communities themselves." Almost decade later, in 1988, the Health Services Transfer Authority "…facilitated the transfer of resources of Indian programs south of the 60th parallel to Indian control."

FNIHB funding authorities were further consolidated in 2005 and again in 2011 to reflect program complementarities in achieving common objectives (as also reflected in FNIHB's revised Program Alignment Architecture or PAA) and to obtain new flexibilities to better accommodate the delivery of health programs and services in First Nations and Inuit context. These renewed funding authorities included the introduction of new funding models to allow FNIHB to reduce the reporting burden on recipients, and to align contribution agreements with the capacity of the recipient to design, manage and monitor their programs and services to address the needs of their population. (See Appendix 1 for more detail on funding models.)

An evaluation was completed in March 2012 covering health planning (governance) activities conducted between April 2005 and March 2010. The synthesis evaluation found that generally the capacity of First Nations communities in managing and delivering health programs and services had been supported by the program activities.

2.2 Program Profile

The Health Planning and Quality Management program administers contribution agreements and direct departmental spending to support capacity development for First Nations and Inuit communities. Key services supporting program delivery include: the development and delivery of health programs and services through program planning and management; on-going health system improvement via accreditation; the evaluation of health programs; and, support for community development activities. The program objective is to increase the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate, and deliver health programs and services.

FNIHB's health planning and quality management activities are managed by three Directorates as well as the office of the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister (health consultation/liaison). Directorates include: Capacity, Infrastructure and Accountability under the Regional Operations Assistant Deputy Minister (health planning), Primary Health Care under the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister (accreditation), and Strategic Planning, and Policy and Information under the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister (health research).

In close collaboration with Regional Operations, the National Office in Ottawa oversees all HPQM program components. The National Office solely manages the delivery of the health consultation/ liaison and health research components. There are six Regional Offices (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta) responsible for delivering the health planning and accreditation funding through contribution agreements with First Nations community organizations. Each regional office tailors its approach to delivering these components to reflect unique regional contexts.

A brief overview of the four program components and the target audiences for capacity building activities is provided below.

Health Planning (Governance)

The health planning (governance) component supports on-reserve First Nations communities in the planning and development of health services and program delivery models. This component supports recipients in the establishment of a strong, effective and sustainable health planning, administration (governance) and delivery infrastructure at the community level. An established health plan and health infrastructure are two critical conditions for First Nations communities to access the more flexible Block funding model.

Accreditation

The accreditation component promotes and supports the accreditation of on-reserve First Nations health programs and services for ongoing health system improvement. Contribution funding assists First Nations organizations to engage in the accreditation process and uses standards of excellence related to sustainable governance, effective organization, service excellence and positive client experience. The accreditation process supports the full involvement of First Nations health services organizations with community leadership, educational services, provincial health services, medical professionals and community members. FNIHB does not accredit health services but rather supports organizations that are engaged in the process with an accrediting body.

Health Consultation/Liaison

The health consultation/liaison component supports consultation and partnerships between National Aboriginal Organizations (NAOs) and Health Canada to improve health outcomes. Through contribution agreements, with both the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), and engagement protocols, the intent is to establish and maintain productive lines of communication and exchanges of policy, research, evaluation and program delivery information between these national partners and regional stakeholders.

Health Research

Terminated in 2011-2012, the former Aboriginal Health Research and Coordination Projects program enhanced knowledge about First Nations health through funding research projects. Since then, through partnerships with other stakeholders, other research activities of the current Health Information and Policy Coordination Unit have continued to be implemented. These remaining activities support: the improvement of the quality and quantity of First Nations health data, research, and information; the development, advancement, distribution and knowledge translation of health information; and the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to generate and access Indigenous health information.

2.3 Program Narrative

According to Health Canada's 2014-2015 Performance Measurement Framework (PMF), the expected result of the health planning and quality management activities is "to increase the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, evaluate and deliver health programs and services."

The connection between the activity areas and the expected outcomes is depicted in the logic model (see Appendix 2). The activity areas, outputs, and immediate and intermediate outcomes for achieving this long-term outcome are organized around five theme areas of: service provision; capacity building; stakeholder engagement and collaboration; data collection, analysis and surveillance; and policy development and knowledge sharing. Each theme area has related outputs and an identified audience that each output is expected to reach, which are then expected to lead to immediate outcomes. For the purposes of this evaluation, some similar outcomes were collapsed to optimize the cogency of the evaluation questions for the evaluation matrix.

Expected immediate outcomes include the following:

- Supporting sustained harmonized and collaborative policy approaches

- Increased collaboration in program and services planning

- Enhanced First Nation and Inuit opportunity to participate in, and influence design and development of, programs and policies

- Increased awareness by health leaders and care providers of quality planning and management activities

The following intermediate outcomes should then flow from immediate outcomes:

- Evidence-based information to support program and policy decisions

- Increased First Nation and Inuit ownership of health planning and quality improvement strategies based on culturally relevant standards

- Improved quality and delivery of programs and services

The long term expected outcome for the program was improved First Nations and Inuit capacity to influence and/or control (design, deliver, and manage) programs and services.

The evaluation assessed the achievement of the expected outcomes and whether there were any challenges and/or barriers to achieving the expected outcomes over the evaluation time frame.

2.4 Program Alignment and Resources

FNIHB's HPQM activities are part of the PAA 3.3: Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit, sub-activity 3.3.1 First Nations and Inuit Health Systems Capacity, sub-sub-activity 3.3.1.1 Health Planning and Quality Management.

The program components' financial data for the fiscal years 2010-2011 through 2014-2015 are presented below (Table 1). Overall, the four program components had combined actual expenditures of approximately $641,817,566 over the five years.

| Year | Gs & Cs | O&M | Capital | Salary | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-2011 | 127,979,189 | 1,737,805 | 201,956 | 4,355,375 | 134,274,325 |

| 2011-2012 | 141,693,662 | 1,150,495 | 0 | 3,403,955 | 146,248,112 |

| 2012-2013 | 123,952,609 | 1,046,764 | 0 | 3,319,214 | 128,318,587 |

| 2013-2014 | 116,511,640 | 450,712 | 770,704 | 2,472,537 | 120,205,593 |

| 2014-2015 | 107,025,350 | 789,994 | 198,031 | 4,757,574 | 112,770,949 |

| Total | 617,162,450 | 5,175,770 | 1,170,691 | 18,308,655 | 641,817,566 |

| Data Source: Financial data provided by Office of Chief Financial Officer | |||||

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

The scope of the evaluation covered the period from April 2010 to March 2015 and included health planning and quality management activities within FNIHB. Considering the long-standing nature and materiality of the First Nations community-based programs in particular, the focus was on the health planning (governance) component and its related capacity building activities. The evaluation also included the following related capacity building activities: accreditation, health consultation/liaison, and health research.

A number of other program areas in the Branch contribute to increasing health programs and services capacity in First Nations and Inuit communities; however these were out of scope of this evaluation as they will be or have recently been evaluated separately. These programs include: Health Services Integration Fund, Human Resources and e-Health. As well, British Columbia projects were excluded due to the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance (October 1, 2013), which will be evaluated through a separate initiative.

The evaluation scope included Inuit under the health consultation/liaison component only. This component includes contribution funding to ITK and the ITK Health Approach agreement with FNIHB. The other components (including health planning, accreditation, and health research) did not provide funding to Inuit organizations or communities between 2010 and 2015. Further, the funding for the Northern Wellness Agreement, self-governance and land claims were excluded because teasing out the federal role is challenging given the leadership role of the territorial and Indigenous governments in managing resources.

The evaluation issues covered were aligned with the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Evaluation (2009) and considered the five core issues under the two themes of relevance and performance, as shown in Appendix 3.Footnote i Corresponding to each of the core issues, specific questions were developed based on program considerations and these guided the evaluation process.

An outcome-based evaluation approach was used for the conduct of the evaluation to assess the progress made towards the achievement of the expected outcomes, whether there were any unintended consequences and what lessons were learned. The Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation (2009) also guided the identification of the evaluation design and data collection methods so that the evaluation would meet the objectives and requirements of the policy. A non-experimental design was used based on the evaluation plan, which detailed the evaluation strategy for this program and provided consistency in the collection of data to support the evaluation. As a non-experimental design, the evaluation relied on correlation to demonstrate effect, without implying causation. As such, the evaluation has been designed to demonstrate the likely contributions of the programs to the expected outcomes, rather than demonstrate direct causal links between the programs and outcomes.

The Assembly of First Nations and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami were consulted during the scoping phase and for the development of the evaluation methodology and tools, including the survey questionnaires and key informant interview guides. They were also consulted on preliminary findings and the draft final report.

Data collection started in April 2015 and concluded in November 2015. Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, which were: key internal and external informant interviews, surveys, case studies, document review, literature review, financial data review and performance data review. Performance measurement data collected by the program was analyzed. More specific detail on the data collection and analysis methods is provided in Appendix 3. In addition, data were analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed above. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. The following table outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings can be used with confidence to guide program planning and decision-making.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Key informant interviews are retrospective in nature. | Interviews are retrospective in nature, providing recent perspective on past events. This can impact validity of assessing activities or results. | Triangulated other lines of evidence to substantiate or provide further information on data captured in interviews.

Document review provided corporate knowledge. |

| There was limited scope of case/site sample selection. | There is an inability to extrapolate findings to the entire population of organizations funded through the health planning (governance) and accreditation components. | Selection took into account representation from various regions (West, Ontario, Quebec, Atlantic), different project sizes (small/medium/large) as well as different areas of the country (e.g., rural, remote/isolated) and findings were used in conjunction with information from other sources. |

| Financial data structure is not linked to outputs or outcomes. | There is a limited ability to quantitatively assess efficiency and economy. | Used other lines of evidence, including key informant interviews and document reviews, to qualitatively assess efficiency and economy. |

| There are limitations in performance data to assess impact on participants over time, due in part the difficulty to attribute long-term impacts amidst many other influencing factors. | We are unable to determine influence on program participants compared to non-participants. | The evaluation focussed on assessing the plausibility of impact on participants through "contribution" rather than attribution. Existing performance information provided indications of success in achieving outcomes. Where information was lacking, triangulation of evidence from literature review, document review, survey and key informants helped to validate findings and provide additional evidence of outcome achievement. |

| At the time of the evaluation, the HPQM logic model had not been updated since 2010. | It was not practical to develop an evaluation matrix that covered all outcomes and in the order in which they were presented in the logic model. | Retaining the integrity of the program narrative, we worked with the program to develop evaluation questions that covered the breadth of the program outcomes in a manner was deemed to provide useful analyses for the evaluation. |

| Given a limited scope for this evaluation, consultation with provincial and territorial representatives was not feasible. | We were not able to gain specific insights on the perspectives of provincial and territorial stakeholders for our analyses. | The document review, as well as other interviews and surveys with a range of key stakeholders from across Canada including regional representatives, were used to triangulate findings related to links with provincial and territorial stakeholders. Any findings statements related to provincial/territorial activities were moderated to reflect data limitations. |

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 - Continued Need for the Program

With a view to improving health outcomes, there is a continuing need to increase capacity and control for First Nations and Inuit to design and deliver health programs and services in their communities.

The health status of many First Nations and Inuit peoples in Canada falls below that of the general Canadian population. Obesity in Canada remains higher in Indigenous populations compared with non-Indigenous populations.Footnote 1 In 2011, the incidence rate of active tuberculosis disease reported for the Canadian-born Indigenous population was 34 times higher than for the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population.Footnote 2 First Nations populations' living on-reserve experience between 2% and 14% higher rates of chronic conditions (asthma, arthritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, or multi chronic conditions) than the general Canadian population.Footnote 3

Health disparities are linked to First Nations and Inuit capacity to lead and deliver health programs and services. Literature suggests that there is the potential for capacity building to improve health programs and services and that there is need for support in this area.Footnote 4 Research has demonstrated that initiatives that are developed, led, and managed by First Nations and Inuit have the greatest potential for success in bringing about quality improvements in health care systems.Footnote 5 As First Nations and Inuit assume responsibility for their health programs and services, there continues to be a need for governments to play a role in facilitating and strengthening the First Nations and Inuit capacity to build and sustain the quality of their health programs and services.Footnote 6

The relationship between improving health outcomes through increased First Nations and Inuit capacity and control is complex. There are a number of considerations which may influence First Nations and Inuit capacity to deliver quality health care programs and services, in turn impacting health outcomes for First Nations and Inuit. Geographic, cultural and social considerations present unique challenges for these health programs and services which require unique, culturally appropriate solutions that are developed and implemented by First Nations and Inuit.Footnote 7

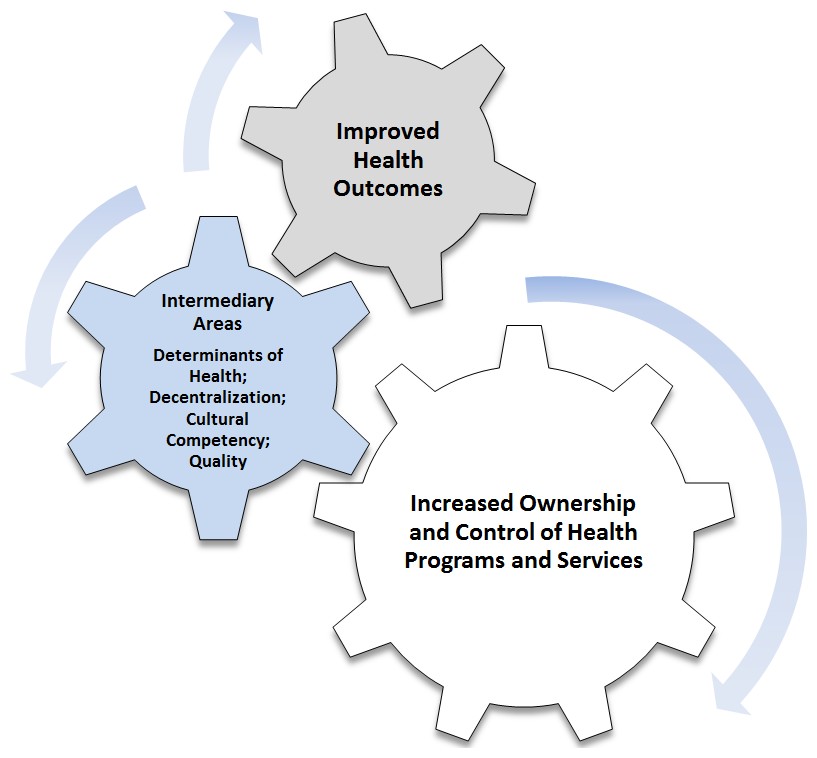

Figure 1. Relationship Between Ownership/Control and Health Outcomes

Text Equivalent

The image in Figure 1 shows three interlocking gears, illustrating the idea that increased First Nations and Inuit ownership and control of health programs and services can lead to positive impacts on community health programs and services affecting four key intermediary areas (or conditions) of social determinants of health, decentralization, cultural competency and safety, and quality of services. This, in turn, can lead to improved health outcomes.

A number of lines of evidence, including a review of the literature on ownership and control leading to better health outcomes, suggest that increased First Nations and Inuit capacity and control can have a positive impact on community health programs and services in four key intermediary areas (or conditions), in turn leading to enhanced health outcomes. As highlighted in Figure 1, the intermediate areas that are necessary to improve health outcomes include: social determinants of health, cultural competency and safety, decentralization, and quality of services. These are the areas much of the literature assumes are impacted as a result of increased self-determination in First Nations and Inuit health programs and services. To varying degrees, the HPQM components reviewed for this evaluation strive to improve health outcomes by increasing the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to have more ownership and control of health programs and services across each of these four intermediary areas.

Social Determinants of Health

Health research shows that poorer health outcomes are due in part to disparities between First Nations and Inuit and the general population in terms of poorer social determinants of health within communities. Health disparities are associated with social, economic, cultural and political inequities that affect individuals, communities and populations.Footnote 8 Among a myriad of factors, communities range in size, level of remoteness, socioeconomic stability, infrastructure, overcrowded and substandard housing, issues with waste water disposal and water pot-ability, internet availability, food shortages, and lack of employment opportunities, all of which may influence the quality of health care services. As stated in the joint Health Canada and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) Community Development and Capacity Building Framework, for communities in crisis, there needs to be a focus on working with other partners to stabilize essential services and build individual capacities, without over burdening with paperwork.Footnote 9

The health planning and accreditation components of the HPQM cluster, in particular, administer their activities with a view to addressing social determinants of health. For example, with the range of flexibility in the funding models and requirements for health planning contributions, there is a differentiated capacity building approach aligned with First Nations community needs. Both health planning and accreditation components are seeking to develop approaches to better address First Nations community needs across the continuum of capacity, with a focus on building on the strengths of communities with lower initial levels of capacity.

Cultural Competency and Safety

In Canada, definitions of culturally competent and safe health care will vary depending on unique individual community characteristics and the specific First Nations and Inuit group. In general, the literature has shown that traditional language knowledge is considered a strong proxy of cultural continuity and capacity. For example, increased language knowledge in Canadian First Nations and Inuit communities was associated with decreased rates of suicide,Footnote 10 as well as lowered prevalence of diabetes.Footnote 11 Past negative experience with discrimination or racism, unfamiliar language and culture, as well as geographic, financial and other barriers can decrease First Nations and Inuit utilization of health programs and services. Therefore, cultural competency and safety is also related to improving utilization ratesFootnote 12 and effectiveness of health programs and services.Footnote 13

In terms of HPQM component activities, cultural competency is built into the program design of various program components. For example, the FNIHB health research program supports the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS). This national survey is grounded in First Nations Principles of OCAP (ownership, control, access, and possession) which means that First Nations control data collection processes in their communities. The RHS Cultural Framework assists "…in achieving a culturally informed interpretation process that can be presented back to communities in a way that is usable and that reinforces their ways of seeing, relating, knowing and being."Footnote 14

Decentralization

Decentralization is the concept of shifting health care control to the community, along with divesting more flexibility and control to Health Canada's regional offices.Footnote 15 Decentralization allows First Nations and Inuit organizations and communities to ensure their priorities are reflected in the health care decision they make.Footnote 16 This concept in integral to the objectives of all HPQM components. Key informant interviews with FNIHB national office and regional staff have indicated that federal health transfer policies have facilitated the ability of some First Nations and Inuit organizations and communities to design health programs, and establish services and allocate funds according to community health priorities. Key informant interviews with FNIHB staff and evaluation surveys (FNIHB regional liaison staff, First Nations community health leaders) also indicate that there is variety in the level of First Nations and Inuit community control exhibited across Canada, depending on the level of community capacity.

The quality of health care in First Nations and Inuit communities may be affected by the capacity and the stability of the health leadership and staff within communities. One of the principles of the Community Development and Capacity Building Framework is leadership in the community - it states that "leaders build hope for the future, and are essential to lead community development."Footnote 17 Key informant interviews and surveys conducted for this evaluation (with FNIHB regional liaison staff and First Nations community leaders) suggest that stable and capable First Nations and Inuit community health leadership is a critical factor for community development of health services and program capacity. It was also suggested that high turnover rates for both leadership and staff are common and the isolation of First Nations and Inuit communities is sometimes an issue in attracting and maintaining capable staff.

Quality of Services

In remote First Nations and Inuit communities, access to primary care is a major issue impacting the health of residents, particularly in rural or isolated communities.Footnote 18 For example, travel costs to access basic services and shipping of medical supplies still present hurdles to providing quality health care in these communities. Key informant interviews with FNIHB national office staff indicated that one of the ways health transfer policies and programs have tried to address these issues is by building First Nations and Inuit community capacity to hire health workers from within the community, as well as increasing salary equity for health care workers to improve retention and recruitment of staff.

Another health care standard important to First Nations and Inuit health is continuity of care. Continuity of care is the cogency with which health service providers at different levels (primary, secondary, tertiary) communicate with one another about shared patients. The remote nature of many First Nations and Inuit communities results in poor continuity of care due to a lack of a consistently accessible doctor, paired with limitations in nearby specialists. This situation creates issues with follow-up between care providers and with accessibility. Although electronic and tele medicine in Canada have helped in improving continuity of care in rural locations, issues still remain. The association between a lack of access to care providers, and continuity between those primary and tertiary health care systems, can lead to poor chronic care outcomes. Footnote 19

Linked to continuity of care is the better integration of First Nations and Inuit health programs and services with the provincial/territorial health care systems which will improve the access and continuity of care received by First Nations and Inuit individuals. Footnote 20 Internal and external key informant interviewees and evaluation surveys (FNIHB regional liaison staff, First Nations community health leaders) suggest that the level of involvement and coordination of other First Nations partners varies across the country and has an effect on the capacity of communities and the quality of health program and services. Regions across Canada vary in terms of the level of involvement and capacity of regional partners. The number of First Nations organizations varies among regions and their varying capacities impact the level and nature of their involvement in communities in terms of building health capacity, therefore improving health outcomes.

Enhancing the quality of health programs and services is a desired outcome of all HPQM components. Impacting the quality of First Nations community health programs and services is a direct objective of community health planning and accreditation activities by embedding quality improvement activities into health programs and services. The quality of health programs and services is also indirectly linked through national and regional consultation/liaison activities (Inuit and First Nations) and enhancing the availability of evidence-based information through health research (First Nations).

4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 - Alignment with Government Priorities

Health planning and quality management activities align with Government of Canada and departmental priorities and strategic outcomes of increasing the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to manage health programs and services and to address health status inequalities affecting communities.

Numerous Speeches from the Throne over the last five years have highlighted the Government of Canada's commitment to recognizing the rights of First Nations and Inuit and the continued development and improvement of communities. The 2011 Speech recognizes that First Nations and Inuit are central to Canada's history and contains a call to action to address barriers to social and economic participation. The 2013 Speech committed to continue dialogue on treaty relationships/land claims and to continue to work with First Nations and Inuit to create healthy, prosperous, and self-sufficient communities. Going forward, the current Government through both the Mandate Letter to the Minister of Health and the 2015 Speech from the Throne has committed to renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with the First Nations and Inuit based on rights, respect, cooperation and partnership.

Through various Budget speeches, the Government of Canada has also made financial commitments to supporting health programs and services to First Nations and Inuit communities. A financial commitment to capacity development at the community level was also established. The 2010 Budget committed to assist First Nations and Inuit communities, including the support of child and family services. The 2011 Budget committed to working through First Nations Land Management Act regimes to allow First Nations to become more self-sufficient and have increased decision-making and management capacity over reserve lands. The 2013 Budget committed to assistance to First Nations and Inuit communities become more self-sufficient and ensures that health care services are accessible, reliable, and of quality for all communities and families across Canada. It also committed to helping these communities prosper. The 2016 Budget highlighted that strong families and communities are fundamental to the success of Indigenous peoples. The Government will work in partnership with First Nations and Inuit to break down the barriers that have for too long held back individuals and communities from reaching their full potential.

The outcomes for this program cluster of activities align with Health Canada's Strategic Outcome #3 as detailed in the 2015-2016 Health Canada Program Alignment Architecture: "First Nations and Inuit communities and individuals receive health services and benefits that are responsive to their needs so as to improve their health status."

Capacity building for health programs and services aligns with the Health Canada strategic outcomes as stated in recent departmental reports on plans and priorities. The 2014-2015 Report on Plans and Priorities states, "…The program objective is to improve the delivery of health programs and services to First Nations and Inuit by enhancing First Nations and Inuit capacity to plan and manage their programs and infrastructure." The 2011-2012 Report on Plans and Priorities states that this cluster of activities "…underpins the long-term vision of an integrated health system with greater First Nations and Inuit control by enhancing the capacity of First Nations and Inuit to design, manage, deliver and evaluate quality health programs and services."

At the Branch level, many of the objectives outlined in the First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan (2012) are reflected in the activities of this health planning and quality management program cluster.

- Health planning and accreditation activities are reflected in the objective to "support First Nations and Inuit in their aim to influence, manage and/or control health programs and services that affect them." These last activities specifically address the need to "…advance aggregated models of health services governance led by First Nations with appropriate capacity to support groups of communities in the management and delivery of programs and services, …and support First Nations and Inuit to achieve strong governance models for health programs and services."

- Health consultation/liaison activities are linked to the stated objective to "…strengthen mechanisms for First Nations and Inuit representatives to influence decision-making at the national and regional senior management levels."

- Health research activities are directly linked to FNIHB objective to "…improve availability of, and access to, high quality data for better decisions from planning to point of care."

4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 - Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The federal government's role in First Nations and Inuit community capacity building has been established through multiple policies, including the federal Indian Health Policy and the Indian Health Transfer Policy.

In Canada, the delivery and support of health care is a shared responsibility between federal and provincial governments. Provinces and territories provide universal insured health programs and services (physician and hospital services) to all residents, including Indigenous peoples. The federal government's role, with respect to the provision and support of health care services for First Nations and Inuit, is based on government policy and involves supplementing programs and services provided by provincial and territorial governments.

Although there is no statutory framework for the provision of health care programs and services to First Nations and Inuit by the federal government, the following policies do outline the goals of the federal government with respect to Indigenous health.

- Consistent with the Indian Health Policy (1979), Health Canada through FNIHB provides or funds health programs and services to First Nations and Inuit. This policy outlines a federal responsibility for the fostering capacity leading to ownership and control for First Nations and Inuit communities with the stated goal "…to achieve an increasing level of health in Indian communities, generated and maintained by Indian communities themselves." This goal is consistent with this program cluster's desired long-term outcome of improved First Nations and Inuit capacity to influence and control (design, deliver and manage) quality health programs and services.

- The Indian Health Transfer Policy (1988) has "…facilitated the transfer of resources of Indian programs south of the 60th parallel to Indian control." It provides a framework for the assumption of control of health programs and services by First Nations and Inuit and set forth a developmental approach to health funding transfer centred on the concept of self-determination in health. It reflects the federal responsibility to build community capacity to support First Nations and Inuit communities in all aspects of health service programming including planning, decision-making, delivery, and potential control of health programs and services. Subsequent funding authorities (2005, 2011) have included the introduction of new funding models to allow FNIHB to reduce reporting burden on recipients, and align contribution agreements with the capacity of recipients to design, manage and monitor their programs and services to address the needs of their own communities.

While there is no duplication, there are opportunities for greater coordination and integration at the federal level.

At the federal level, there is complementarity among the roles of Government of Canada departments that support capacity building in First Nations and Inuit communities.

- INAC addresses social determinants of health on and off reserve as they relate to their broader scope for community development including: land management for economic development, development of community plans, supporting Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFIs) for business development, community planning, and infrastructure improvement. INAC also leads the Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) in collaboration with its partners. There are agreements and Memoranda of Understandings (MoUs) between Health Canada and INAC at the Ministerial, Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) and Director General (DG) levels that reflects collaboration across these two departments.

- Public Safety Canada supports emergency planning to maintain a strong and safe community so that the other health promotion elements (e.g., health planning, health service delivery/quality improvements) can be supported. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police's (RCMP's) public safety role is similar in its provision of direct policing services, particularly in rural and remote First Nations and Inuit communities, and crisis response functions (including suicide monitoring).

- The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) have a mandate to support culturally relevant research on Indigenous peoples health. Health Canada supports the CIHR, in particular by providing advice and direction on the Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal Peoples project. This project aims at understanding how to implement multilevel and scalable interventions to reduce health inequities for Indigenous peoples.

- Other departments that have complementary roles to that of Health Canada include: the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Canada (housing), Employment and Social Development Canada (employment and training), and Statistics Canada (survey data and analyses, specifically through the Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division).

While it appears that the mandates of federal departments and their programs are distinct, there is still a need for a more holistic approach across departments to support capacity building in First Nations and Inuit communities. Key informant interviewees with the federal government and NAOs, and survey respondents (FNIHB regional liaison staff, First Nations community health leaders), indicated that there is a need for clearer communication, coordination and collaboration among federal departments.

4.4 Performance: Issue #4 - Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

4.4.1 To what extent has evidence-based information to support program and policy decisions been made more accessible?

The FNIHB Surveillance Health Information Policy and Coordination Unit has contributed to the availability and use of evidence-based information on First Nations health.

The Surveillance Health Information Policy and Coordination Unit (SHIPCU) is the focal point for the development and dissemination of evidence-based information within FNIHB. While the Unit does not undertake primary research activities in-house, in particular since the termination of the Aboriginal Health Research and Coordination Projects funding in 2011-2012, it facilitates the generation of evidence-based information through effectively leveraging and influencing the research agendas and initiatives of other federal government organizations and partnering with First Nations organizations.

- In terms of other federal collaborations, the Unit works closely with the CIHR, in particular the Institute for Aboriginal Peoples Health. It participates in advisory meetings for the "Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal Peoples" initiative which is designed to increase the understanding of the implementation of multilevel and scalable interventions for Indigenous peoples. These interventions help to address issues such as tuberculosis, diabetes, mental health and suicide, and children's oral health. It collaborates with Public Health Agency of Canada to support their work on surveillance plans for communicable diseases on-reserve. The Unit also liaises with and supports INAC and Statistics Canada with respect to the health supplement of the Aboriginal Peoples Survey and on-reserve data collection.

- A significant research partnership over the last number of years has been with the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). Through this partnership, the Surveillance Health Information Policy and Coordination Unit has been a primary financial contributor, advisor and promoter for the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) - the only First Nations governed national health survey in Canada. Incorporated in 2012, the mission of the FNIGC is to build capacity and provide credible and relevant information on First Nations using the highest standards of data research practices, while respecting the rights of First Nations self-determination for research and information management. The RHS collects information about on-reserve and northern First Nations communities based on both Western and traditional understandings of health and well-being.

Evidence-based research and analyses that has been leveraged and generated by the Unit helps to support management decision-making and reporting within FNIHB. Internal FNIHB key informant interviews indicated that the Unit provides evidence-based information for senior management briefings and presentations within FNIHB, including RHS information, to support: program management (including some outcome tracking), corporate planning and reporting, and program funding renewal.

Through FNIHB, support to the Regional Health Survey has been enhanced.

The Assembly of First Nations Chiefs in Assembly, the Chiefs Committee on Health (CCOH) and First Nations Regions across the country have mandated the FNIGC to provide oversight and governance over the RHS at the national level. Activities include preparing reports, serving as the data steward, and engaging in partnerships. Ten independent regional partners coordinate the RHS in their respective regions. The FNIGC and regional partners collaborate on collective issues as well as share ideas and knowledge. The FNIGC is mandated and authorized to report on national level statistics while each regional partner is completely independent and responsible for their own respective regional databases and reporting. The FNIGC and regional partners have completed and published national and regional reports for two first two RHS phases (2002-2003, 2008-2010). The data collection for the third phase began in March 2015.

The RHS process has been a factor in the creation of the First Nations Principles of OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access and Possession). This approach is unlike other Canadian survey and research approach as the data produced through the RHS is the property of First Nations peoples. The RHS has led the way for First Nations to exercise jurisdiction over their research information and is the first national survey implemented explicitly to respect the First Nations Principles of OCAP. The RHS also follows a special code of research ethics and cultural framework which allow First Nations perspectives to be respected in the process. Internal and external key informants indicated that these principles have helped to build trust with First Nations communities and create greater buy-in to research and data collection processes as a whole.

The RHS information is used at both the national and regional levels. External key informants indicated that at the national level the Assembly of First Nations uses RHS information to make resolutions, which are important in setting the agenda of the organization. The FNIGC liaises regularly with the AFN about common data and research needs. The RHS information is used to complement regional data collection efforts to create a more fulsome picture of First Nation health within regions. It has helped to support First Nations managed regional data hubs where this data is stored and reports are published. For example, in the Quebec region, La Commission de la Santé et des Services Sociaux des Première Nations du Québec et du Labrador houses the Quebec RHS information and publishes the Quebec RHS report. According to key informant interviewees with FNIHB Quebec regional staff, these efforts have helped to develop capacity for data analysis and dissemination at the regional level for First Nations organizations in Quebec.

Further knowledge translation would increase use within FNIHB and externally at the regional and community levels.

FNIHB national office and regional staff key informants indicated that further knowledge translation within FNIHB may enhance the use of evidence-based information in policy and program decision-making.Footnote ii Further uses for knowledge translation that were suggested included: corporate reporting, informing and targeting programming, informing and validating interventions, and publications. It was suggested that the level and quality of use of data could be improved with more dedicated resources to analyze data for policy purposes.

FNIHB national office and regional staff, and representatives from NAOs including the FNIGC, related that the regional capacity for information collection, analysis and dissemination vary greatly between regional hubs. Results from both surveys (FNIHB regional liaison staff and First Nations community health leaders) suggest that, at both the regional and community levels, there are gaps in knowledge about the availability and accessibility of data and information that has been generated. The survey respondents also suggested that the majority of First Nations communities are unaware that there are published studies available or data and statistics collected that provides insight on health needs. A variety of key informants suggested that when provided with this material, even fewer First Nations communities have the capacity to use the information in a practical application for their health plans or within the health programs themselves.

4.4.2 Have opportunities for First Nation and Inuit to participate in, and influence design and development of, programs and policies been enhanced? In what ways?

Progress has been made in strengthening the mechanisms available to First Nations and Inuit representatives to influence decision-making at the national and regional senior management levels.

Contribution agreements with both the AFN and ITK were in place to increase opportunities for First Nations and Inuit to participate in and influence national health policy, health systems and programs/services development in all health related areas. Annual reports and evaluation reports completed by both national Aboriginal organizations reflect that these agreements led to an increased capacity to plan and conduct work around First Nations and Inuit specific health priorities over the last five years. The flexible and multi-year nature of these Contribution Agreements was associated with many positive process improvements, including: the ability to respond to region-driven priorities, the ability to engage in long-term planning, the development of long-term partnerships, and the ability to address emerging priorities. For example, ITK Annual Report 2014-15 states that representatives of the FNIHB have done extensive work outlining health data priorities and have consistently communicated and coordinated these priorities to align with ITK's interests to the extent possible.

A significant development took place in 2014 when FNIHB senior management and two national First Nations and Inuit representative organizations formalized engagement protocols.

- The first of these agreements is the Assembly of First Nations Engagement Protocol. The Engagement Protocol was created to strengthen the collaborative relationship between AFN and FNIHB and is the result of years working together to establish a culture of transparency and reciprocal accountability. The Engagement Protocol outlines how AFN and FNIHB will engage at national and regional levels and how the two groups will work together to ensure First Nations regional representatives and communities are engaged in the advancement of the First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan. Additional objectives of the Protocol include to: map out how the First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan and the AFN First Nations Health Foundational Plan complement each other; respect existing and ongoing national, regional and community-level collaboration; and provide a map for a process of FNIHB engagement with the AFN, as well as engagement with other partners of mutual interest.

- The second agreement is the Inuit Tapirit Kanatami Health Approach. The Health Approach is a commitment for FNIHB to work with ITK to develop an approach to Inuit health that informs planning within Health Canada. It seeks compatibility between the First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan and the National Inuit Committee on Health (NICoH) Strategic Framework. The specific objectives of the Health Approach are to: promote awareness among all FNIHB employees of the unique features of Inuit health, and contexts of the four Inuit regions and ensure that the Inuit Health Approach is a cornerstone of the Branch's policy and program frameworks; clarify the appropriate engagement process of FNIHB with Inuit at the national and regional levels; and ensure that FNIHB respects the principles and processes established in the Land Claim Agreements in its relationship with Inuit.

In terms of providing opportunities to influence decision-making at the national level, both the Engagement Protocol and Health Approach have ensured that First Nations and Inuit representatives have a seat at FNIHB's National Senior Management Committee (SMC) Table. The mandate of the SMC is to: provide overall policy direction for the Branch, consistent with the goals and principles of the First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan; monitor and provide direction for the Plan's implementation, including collaboration and partnership initiatives; review, approve and provide direction on policy issues and approaches; and review and approve proposals for modernizing policies and programs. In addition, the Engagement Protocol and Health Approach have ensured that First Nations and Inuit representatives have a seat on FNIHB's SMC Policy and Planning Subcommittee. The mandate of the SMC Policy and Planning Subcommittee, among other things, is to develop an engagement approach including all relevant partners, and to define the initial scope of a new proposal or terms of reference for policy/program development or modernization.

Representation on internal FNIHB senior management committees is intended to develop quality engagement and participation and increase opportunities for these organizations to influence decision-making at the national level. Key informant interviewees, FNIHB national office and regional staff and representatives from NAOs, indicated that both AFN and ITK are engaged at the national level as a result of the Engagement Protocol and the Health Approach. Although it is too early to determine whether First Nations and Inuit representatives have been able to influence decision-making in a meaningful way through these engagement protocols, the development of these two agreements demonstrates progress in strengthening the mechanisms available to First Nations and Inuit representatives to influence national-level decisions moving forward.

4.4.3 Has First Nation and Inuit collaboration (consultation and partnerships) with partners and other stakeholders in program and services planning increased? In what ways?

Opportunities have increased for First Nation and Inuit representatives to collaborate and participate in the design and development of programs and policies at the national, regional and community levels.

Several lines of evidence (i.e., key informant interviews, evaluation surveys, case studies and document review) identified that through health planning and quality management activities, there were increased opportunities for consultation and partnerships at various levels for First Nations and Inuit representatives, resulting in increased opportunities to participate in the design and development of programs and services.

As mentioned previously, the AFN Engagement Protocol and ITK Health Approach are formal mechanisms that have increased opportunities for First Nations and Inuit representatives to influence decision-making at the national level. The Engagement Protocol specifies that FNIHB regional offices will maintain direct engagement with First Nations communities on matters that affect them, and engagement with other partners of mutual interest. Similarly, the Health Approach specifies that FNIHB will "work with Inuit, territorial and provincial governments and other federal partners to develop an approach to Inuit health that informs planning within Health Canada." The document review and key informant interviews (FNIHB national office and regional staff, representatives of NAOs) indicated that the Engagement Protocol and Health Approach have increased opportunities for First Nations and Inuit representatives to collaborate with representatives at different levels (national, regional, community) to influence program design and services development. Regionally, FNIHB regional offices engage directly with First Nations organizations on Regional Health Plans and other regional matters.

Beyond these formal mechanisms, these key informants also indicated that there is a trend toward greater FNIHB regional collaboration with First Nations and Inuit representatives. FNIHB Regional Executives and other FNIHB representatives: participated in a number of trilateral tables in which First Nation representatives participate/influence in the design of programs or policies along with provincial governments; liaised with First Nations umbrella organizations; and collaborated with Chiefs and participated in the development of working groups with Tribal Councils. The FNIHB regional liaison staff and First Nations community health leaders surveys indicated that consultation is occurring more often between FNIHB and provincial government representatives on issues related to First Nations and Inuit health programs and services. These examples of increased engagement have the potential to lead to opportunities for First Nations and Inuit representatives to influence the design and development of programs and services.

In terms of health planning and accreditation activities in First Nations communities, respondents to the FNIHB regional liaison staff and First Nations community health leaders surveys, and the case studies, indicated that these activities have supported consultation and collaboration at regional and community levels - leading to a direct impact on program decision making by First Nations communities. Health planning and accreditation have facilitated a greater awareness by First Nations communities of the importance of partnerships and collaborations at all levels. Survey respondents also indicated that longer term contribution agreements have increased the opportunity for First Nations representatives to collaborate with partners in programs and services planning. Longer term contribution agreements, accompanied with their relative flexibility, allow more time to form meaningful partnerships at all levels.

4.4.4 What types of supports or activities are effective in supporting transition to more flexible funding models? Are there any barriers or challenges?

Funding models broadly reflect levels of community capacity to take ownership and control over delivery and management of health services on-reserve.

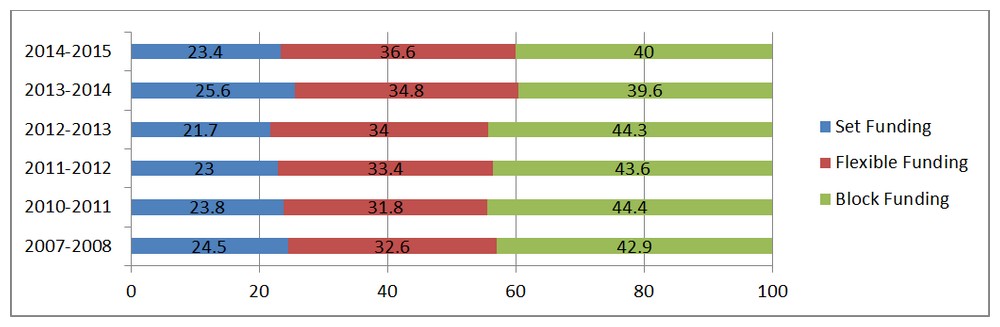

The distribution of First Nations communities' contribution agreements in Set, Flexible, and Block funding models has not significantly changed since 2010 (see Table 3). Data from the Management Contract and Contribution System (MCCS) indicates that as of March 31, 2015 a majority of communities have signed contribution agreements in a Flexible (37%) or Block (40%) funding model. There were also 23% in the Set funding model.Footnote iii

Table 3: Funding Models for First Nations Communities 2007-2015

Source: Data provided by the program from MCCS as of March 31, 2015.

Note: In 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 First Nations communities in British Columbia were removed from the list due to an agreement with First Nations Health Authority (FNHA).

Text Equivalent

Table 4 shows the percentage distribution of First Nations communities' contribution agreements between the three available funding models, Set, Flexible, and Block funding, over six fiscal years. The data was extracted by the program from the Management Contract and Contribution System and was current as of March 31, 2015. Note: in 2013-2014 and 2014-2015, First Nations communities in British Columbia were removed from the list due to an agreement with the First Nations Health Authority with is now responsible for delivering FNIHB activities in that province.

In 2007-2008, 24.5% of recipient First Nations communities had set funding contribution agreements, 32.6% had flexible funding agreements and 42.9% had block funding agreements.

In 2010-2011, 23.8% of recipient First Nations communities had set funding contribution agreements, 31.8% had flexible funding agreements and 44.4% had block funding agreements.

In 2011-2012, 23% of recipient First Nations communities had set funding contribution agreements, 33.4% had flexible funding agreements and 43.6% had block funding agreements.

In 2012-2013, 21.7% of recipient First Nations communities had set funding contribution agreements, 34% had flexible funding agreements and 44.3% had block funding agreements.

In 2013-2014, 25.6% of recipient First Nations communities had set funding contribution agreements, 34.8% had flexible funding agreements and 39.6% had block funding agreements.