Archived - Evaluation of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy 2012-2013 to 2015-2016

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 867 K, 96 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: 2017-06-13

Prepared by Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

January 2017

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 – Continued Need for the Program

- 4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 – Alignment with Government Priorities

- 4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 – Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 4.4 Performance: Issue #4 – Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

- 4.5 Performance: Issue #5 – Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency

- 5. Conclusions

- Appendix 1 – Logic Model

- Appendix 2 – Summary of Findings

- Appendix 3 – Evaluation Description

- Appendix 4 – Case Studies

List of Tables

- Table 1. Initial Funding by Partner Department/Agency

- Table 2. Partner Department/Agency engaged in each activity area

- Table 3. Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Table 4. Rates of Non-Compliance with Selected Provisions of the Tobacco Act/Regulations and Number of Samples Analyzed – Manufacturing/Importing Sector, 2012-2013 to 2015-2016

- Table 5. Rates of Non-Compliance with Selected Provisions of the Tobacco Act/Regulations and Inspections Conducted – Retail Sector, 2012-2013 to 2015-2016

- Table 6. Reports Reviewed Deemed Incomplete and Letters of Deficiency Issued – Manufacturing/Importing Sector 2012-2013 to 2015-2016

- Table 7. RCMP Seizure Data on Contraband Tobacco

- Table 8. Canada Border Services Agency Seizure Data on Contraband Tobacco

- Table 9. Post-Event Surveys

- Table 10. Allocations and Expenditures

- Table 11. Leveraged funds for PHAC Federal Tobacco Control Stategy projects

List of Figures

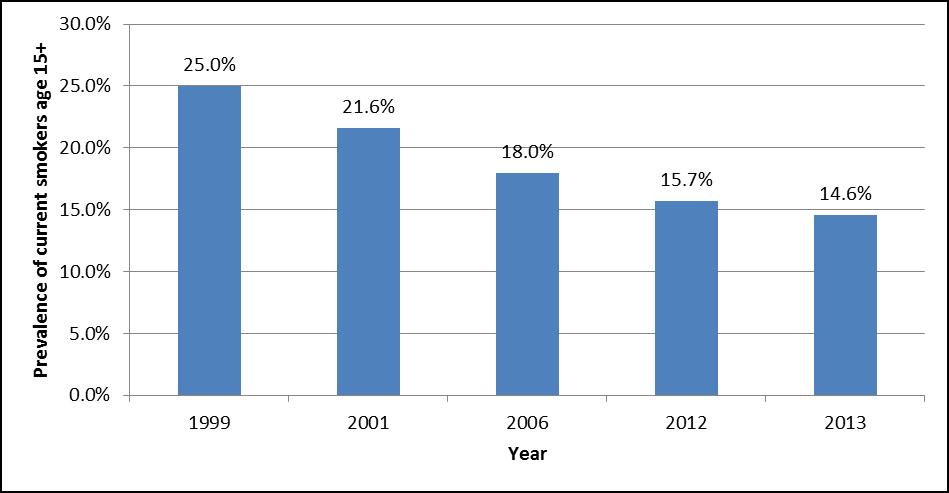

- Figure 1: Smoking Prevalence Rates in Canada

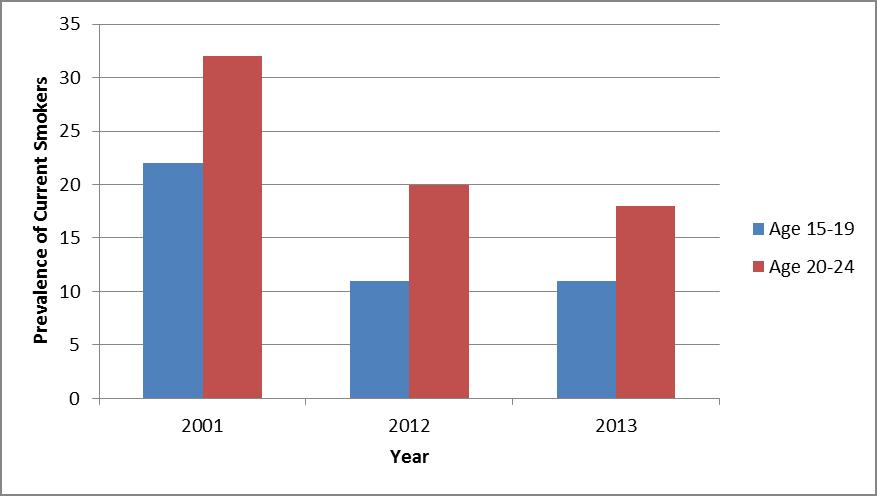

- Figure 2: Smoking prevalence in youth and young adults, 2001, 2012, 2013

- Figure 3: Smoking Prevalence 1999-2013 – Current Smokers Age 15+

List of Acronyms

- AMPS

- Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service

- APS

- Aboriginal Peoples Survey

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CCDP

- Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention

- CIPR

- Cigarette Ignition Propensity Regulations

- COPD

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPAB

- Communications and Public Affairs Branch

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CTADS

- Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey

- CTUMS

- Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey

- FCTC

- Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- FNIC

- First Nations and Inuit Component

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

- FTCS

- Federal Tobacco Control Strategy

- HECSB

- Healthy Environment and Consumer Safety Branch

- IHGP

- International Health Grants Program

- INSPIRE

- Implementing a National Smoking Cessation Program in Respiratory and Diabetes Education Clinics

- MANTRA

- Manitoba Tobacco Reduction Alliance

- MOA

- Memorandum of agreement

- OIA

- Office of International Affairs

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PPSC

- Public Prosecution Services Canada

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RHS

- Regional Health Survey

- RORB

- Regulatory Operations and Regions Branch

- TCD

- Tobacco Control Directorate

- TCLC

- Tobacco Control Liaison Committee

- TCP

- Tobacco Control Program

- TDL

- Tobacco Dealer Licensees

- TEACH

- Training Enhancement in Applied Cessation Counselling and Health

- TFI

- Tobacco Free Initiative

- TPLR

- Tobacco Products Labelling Regulation (Cigarettes and Little Cigars)

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Executive Summary

This evaluation covered the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) for the period from 2012-13 to 2015-16. The evaluation was undertaken in fulfillment of the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Evaluation (2009).

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the FTCS. The evaluation covered the activities of the current federal partners (Health Canada, Public Safety Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Canada Border Services Agency, and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)). The time-limited funding provided to the Public Prosecution Service of Canada in 2012-13 was not covered by this evaluation.

Program Description

The FTCS is a comprehensive horizontal strategy involving a variety of partner departments and agencies across the federal government to address tobacco control. Health Canada, as the lead department, is in charge of the majority of FTCS activities, and as such is responsible for regulating tobacco products, conducting compliance monitoring and enforcement activities with respect to the Tobacco Act, developing policy, conducting research, assisting with the health of First Nations and Inuit peoples, providing litigation support, supporting the pan-Canadian quitline, and ensuring that FTCS activities are aligned with federal health priorities. PHAC's key responsibilities are finding innovative ways to help people stop smoking and the strategic management of international issues. Three organizations within the Public Safety portfolio (Public Safety, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Canada Border Services Agency) are responsible for activities related to the contraband tobacco market and provide information to the Department of Finance. Finally, CRA's key activity is ensuring compliance with the Excise Act, 2001.

Conclusions – Relevance

Continued Need

Our analysis concludes that there continues to be a need for tobacco control across Canada. Although smoking prevalence has declined in Canada, the most recent data from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drug Use Survey (CTADS) 2013 shows that the overall smoking prevalence was 14.6%. This means that in 2013 there were approximately 4.2 million Canadians aged 15 and older who smoke. Higher smoking rates are reported in both Inuit and First Nations communities (on-reserve). In 2010, 43% of adults living in First Nations communities were daily smokers and 13.7% were occasional smokers. Data from the 2012 Aboriginal Peoples Survey indicate that 54.1% of Canada's Inuit population aged 19 years and older smoke daily and 9.1% smoke occasionally. Tobacco use continues to have a health impact on Canadians, with tobacco smoking playing a causal role in over 10 different cancers, cardiovascular disease, stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The economic burden of smoking in Canada was estimated at over $18 billion annually in 2013.

Alignment with Government Priorities

Tobacco control issues are aligned with the federal government's priority to protect the health and safety of Canadians. The Minister of Health's mandate letter (2015) specified tobacco control through plain packaging as one of the top priorities. Tobacco is a risk factor for chronic disease, and as such fits within the PHAC priority of "leadership on health promotion and disease prevention". CRA actively ensures that federal taxes on domestic tobacco products are paid. Public Safety portfolio partners in the FTCS monitor and assess the contraband tobacco market, as it aligns with their priorities to address organized crime and smuggling. As well, Canada has international commitments and obligations, particularly pursuant to the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

A clear federal role pertaining to tobacco control has been established in existing legislation, namely the Tobacco Act and the Excise Act, 2001. There are also roles in tobacco control for other levels of government within their respective jurisdictional mandates. Input from key informants was consistent in noting that stronger federal leadership – particularly on regulatory matters – would serve to enhance uniformity and provide a consistent level of protection across Canada.

Conclusions – Performance

Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

In general, the FTCS is making progress in achieving its expected outcomes. The overall decline in smoking prevalence has slowed down, but the downward trend in prevalence has continued. There was no prevalence target set for the 2012-2017 time period of the FTCS, so it is difficult to measure the success of the strategy in this regard.

Compliance with existing regulations and provisions of the Tobacco Act and the Excise Act, 2001 has increased. This has been accomplished through the continued and consistent monitoring from Health Canada and the CRA.

The support to enhance the quitline cessation services has resulted in an increase in the number of smokers receiving help to quit smoking. As well, early indications from projects addressing cessation show that they are on track for success. However, the reach of these projects remains limited.

Prevention has been addressed through provisions made under the Tobacco Act and its regulations, including prohibiting sales to youth, health-related labelling requirements, tobacco promotion restrictions and flavour restrictions. Stakeholders reported that prevention activities have been undertaken by other levels of government, creating a patchwork of efforts.

Young people have been protected from inducements to take up tobacco use through ongoing monitoring of promotions to youth as well as bans on flavours that may appeal to youth. While flavour restrictions on certain tobacco products have had success in decreasing youth usage, there are some areas of the tobacco environment where the federal government has not appeared as responsive, including the increasing popularity of vaping products.

With regards to contraband tobacco, FTCS efforts are focussed on monitoring and assessing the illicit market. Reported seizures of contraband tobacco products have decreased; however, seizure rates are variable over short time intervals and the reason behind these declines is unclear. There continues to be a demand for a better national understanding of the contraband tobacco market from both governmental and non-governmental sources.

The FTCS has conducted the activities it set out to do within the time period evaluated, and with the funding allocation provided to FTCS partners. Some key informants felt that these activities were not ambitious enough. However, Canada's activities align with the main articles of the WHO FCTC and provide a multi-sectoral national approach to tobacco control.

Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency

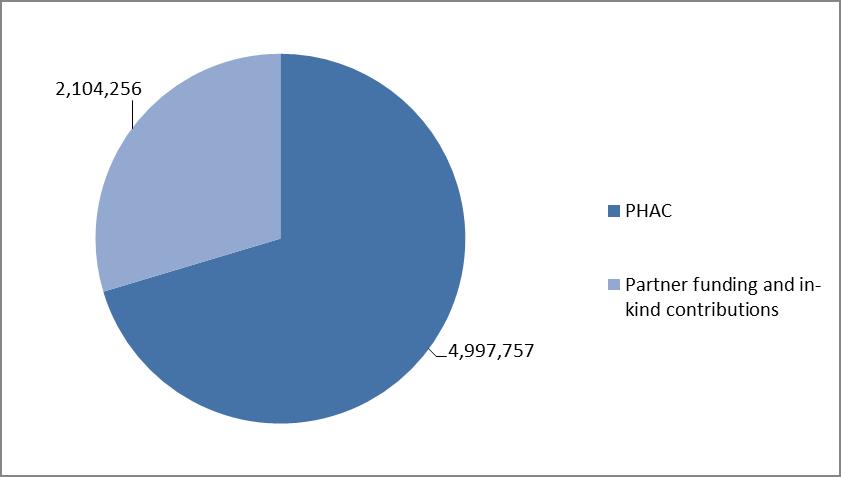

Many activities funded through the FTCS derived success through collaboration and partnerships. In particular, PHAC-funded projects leveraged funds using multi-sectoral partnership. However, further engagement of external organizations and other levels of government would be useful in advancing Canada's tobacco control goals.

FTCS funding was reduced by approximately 35% from the previous 5-year period. Reduced funding and a focus on economy negatively impacted operational efficiency in some areas. This is most apparent in the FTCS's research and surveillance capacity, in which the annual tobacco use survey was changed to a biennial survey covering multiple topics including alcohol and illicit drugs.

Inefficiencies were noted when considering differences among the province and territories for areas of federal interest. Stakeholders reported that provinces and territories developed patchwork legislation respecting emerging issues in the absence of action at the federal level, creating inequity for Canadians. Further, separate funding agreements for quitline service allowed for dissimilar levels of service resulting in confusion for service providers.

All federal partners were aware of their specific areas of responsibilities and did not report duplication of efforts. However, it was not readily apparent that there were linked activities taking place across several strategy partners and the level of engagement of the partners varied. Meetings of the Coordinating Committees were infrequent and concerns were noted regarding delays in approving common reports.

Recommendations

The findings from this evaluation of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy have resulted in the following four recommendations.

Recommendation 1

Explore the setting of targets for the reduction of smoking prevalence rates, both for the general population and populations with higher prevalence rates.

The lack of a reduction target for smoking prevalence in the 2012-2017 FTCS was seen by stakeholders as an impediment in measuring the overall success of the program and in focussing the activities of the FTCS on a unified goal. Canada was successful in reaching the targets set in early versions of the FTCS, and has a current prevalence rate of 14.6%. The WHO voluntary target prevalence is 10.57% for Canadians aged 15 years or older by the year 2025, and based on projections Canada is on track to meet this. Other countries similar to Canada have set specific national tobacco reduction targets that are more ambitious.

There have never been targets set for groups within Canada with higher prevalence rates. These rates have not decreased as quickly as the overall prevalence rates, and may need more directed efforts. Given Health Canada's mandate for health services and benefits for First Nations and Inuit populations, as well as the federal government's overall commitment for a relationship with Indigenous peoples, engage First Nations and Inuit leadership and communities to establish targets that are relevant and appropriate may focus Strategy activities and help define the future direction of the Strategy.

Recommendation 2

Clearly identify and articulate the areas for federal leadership in tobacco control, particularly in light of the existing provincial, territorial and municipal actions.

Tobacco control requires concerted efforts from multiple levels of governments across jurisdictions. Moving forward with the FTCS, it will be important for the federal government, in consultation with stakeholders and other levels of government, to clearly identify and articulate the regulatory and policy areas for federal leadership. This will assist stakeholders and other levels of government in understanding their role in regard to tobacco control.

While there have been calls for more national action in regard to tobacco control, the partner departments will need to examine the areas and populations that may benefit most from these actions. Opportunities for these national actions could be explored within the Strategy where feasible.

Recommendation 3

Options for regulating new and emerging tobacco control issues should be explored.

The tobacco industry is innovative, and often legislation and regulation lags behind new developments. Stakeholders suggested that there is a need for consistent federal regulations, and enforcement of these regulations, to protect the health of Canadians, and in particular youth. Moving forward, the federal government should encourage responsiveness to emerging tobacco products and ensure that the appropriate regulatory framework is in place and communicated to both industry and the public.

As new and emerging issues arise and regulation is required to address them, it will be important to explore innovative funding approaches to address tobacco control. These funding approaches could be based on international models, such as the imposition of a 'tobacco levy'.

Recommendation 4

Examine the feasibility of integrated reporting on aspects related to contraband tobacco to facilitate Canada-wide analysis.

The continued existence of the contraband tobacco market undermines tobacco control efforts across Canada. Multiple federal departments and agencies independently monitor different dimensions of contraband tobacco, as do other levels of governments and law enforcement agencies in Canada. In addition to government efforts, industry-sponsored organizations have also attempted to assess the scope and nature of the contraband tobacco market, in particular how it relates to youth. While the monitoring of contraband tobacco is widespread, there is little consistency on what is reported. It is beneficial for departments and agencies to be able to provide a comprehensive and integrated overview of the tobacco market, including trends. Given that there are multiple departments and agencies involved, each with their own data collection systems and internal reporting requirements, the compilation of contraband data may pose a challenge. At this time, the feasibility for integrating reporting should be explored, and where possible, a streamlined approach to reporting should be undertaken.

Management Response and Action Plan

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables | Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

| The Strategy should explore the setting of targets for the reduction of smoking prevalence rates, both for the general population and populations with higher prevalence rates. | Agree | Targets will be set for the reduction of smoking prevalence rates in the context of work undertaken for a renewed approach to tobacco control in Canada. | Report on consultations with stakeholders. | May 2017 |

|

|

| Report on sex, gender-based and socioeconomic analysis of tobacco use in Canada. | January 2017 | |||||

| New targets set in the renewed approach to tobacco control. | April 2018 | |||||

| Identify the areas for federal leadership in light of the existing Provincial/Territorial and Municipal actions in the area of tobacco control. | Agree | The Directorate will proceed with an assessment of the current federal role in tobacco control and explore new areas of responsibility and partnership in the context of work undertaken for a renewed approach to tobacco control in Canada. | Report on consultations with stakeholders, including provinces, territories and municipalities. | May 2017 |

|

3 FTEs (existing resources) |

| Federal role delineated in the renewed approach to tobacco control. | April 2018 | |||||

| Explore options for regulating new and emerging tobacco control issues. | Agree | TCD will continue to develop a new vaping regime. | Introduction of the new legislation. | Nov 2016 |

|

2 FTEs (existing resources) |

| Coming into force of a new vaping regime. | TBD | |||||

| Examine the feasibility of integrating reporting on issues related to contraband tobacco to provide a Canada-wide picture. |

|

|

Inventory of what is currently being reported and how. | January 2017 |

|

|

| Inventory of existing reports regarding contraband tobacco. | January 2017 | |||||

| Gap analysis of reporting that exists and what is required. | February 2017 | |||||

| Recommendation on integration of reporting on contraband tobacco. | April 2017 |

1.0 Evaluation Purpose

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the Federal Tobacco Control Strategy (FTCS) for the period of April 2012 to March 2016. The evaluation was undertaken in fulfillment of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Evaluation (2009). The evaluation was conducted by the Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada's Office of Audit and Evaluation in accordance with the Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2015-2016 to 2019-2020.

2.0 Program Description

2.1 Program Context

The FTCS is a horizontal initiative led by Health Canada in partnership with PHAC; Public Safety Canada; the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP); Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA); CRA; and the Public Prosecutions Service of Canada (PPSC). As the activities of the PPSC pertaining to tobacco control involved time-limited funding, they are not included in the scope of the evaluation.

The FTCS was introduced in 2001 as a 10-year, comprehensive, sustained and integrated strategy to achieve significant reductions in disease and death due to tobacco. It built on the progress made under the 1997 Tobacco Control Initiative and the 1994 Tobacco Demand Reduction Strategy. In Budget 2012, the FTCS was renewed for an additional five years (2012-2017) with a goal to preserve the gains of the past decade in continuing the downward trend of smoking prevalence, and to invest in new priorities, including populations with higher smoking rates.

As part of Budget 2012, the FTCS was streamlined and refocussed on new priorities. This included funding new targeted activities, such as the implementation of a pan-Canadian Quitline; a marketing campaign for young adults; First Nations and Inuit initiatives; and, tobacco cessation interventions to support chronic disease prevention. Broad-based contribution funding for non-governmental organizations and provinces and territories ended, as did retail inspections for tobacco sales-to-youth. The drugs, alcohol and annual tobacco surveillance tools were combined into a single biennial survey.

Throughout the evaluation report, tobacco refers to commercial tobacco use. Traditional or sacred tobacco use among First Nations is separate, and the FTCS respects and recognizes traditional forms and uses of tobacco within communities.

All forms of tobacco are regulated under the Tobacco Act. At the time of this report, this does not include e-cigarettes or vaping. Electronic cigarettes that contain nicotine or come with health claims fall within the scope of the Food and Drugs Act and require market authorization by Health Canada prior to being imported, advertised or sold. No vaping devices or electronic cigarettes or other vaping devices with nicotine have been authorized by Health Canada.

2.2 Program Profile

The FTCS is a comprehensive strategy involving a variety of partner departments and agencies across the federal government.

| Partner Department/Agency | Funding (in $000) | Percentage of total 5 year funding (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Health Canada – excluding FNIHB | 160.6 | 70.3 |

| Health Canada – First Nations and Inuit Health Branch | 22 | 9.6 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada – Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch | 10.25 | 4.54 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada – Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio | 1.25 | 0.5 |

| Public Safety | 3 | 1.3 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 8.5 | 3.7 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 18.4 | 8.1 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 4.5 | 2.0 |

| Source: Refocusing the FTCS. Financial data provided by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer | ||

The FTCS funded activities and role of each of the partners is described below.

Health Canada

Health Canada is the lead department for the FTCS and has multiple branches engaged in tobacco control activities.

The Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch (HECSB) is responsible for the regulation of tobacco and promoting initiatives to reduce and prevent the harm caused by tobacco. Within this branch, the Tobacco Control Directorate (TCD) is responsible for activities such as developing policies on tobacco control, developing and maintaining international agreements on tobacco control, developing regulations under the Tobacco Act, monitoring industry compliance with the Act and its regulations and undertaking enforcement activities, surveying, monitoring and analyzing tobacco issues, and supporting the pan-Canadian Quitline. Administrative, financial, and strategic support is also provided to address Health Canada's obligations resulting from tobacco litigation. Compliance monitoring and enforcement activities are done in conjunction with the Regulatory Operations and Regions Branch (RORB).

The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) works in partnership with First Nations, Inuit, provinces, territories and other government departments to improve health outcomes and to improve access to quality health programs and services that are responsive to the needs of First Nations and Inuit individuals, families, and communities. The FNIHB is responsible for a new initiative funded by the FTCS to assist a targeted number of on-reserve First Nations and Inuit communities to develop and implement evidence-based tobacco control projects and strategies that are holistic, culturally appropriate, and focussed on reducing non-traditional tobacco use. The approach is guided by best practices as identified by the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). The approach is organized around the four pillars of leadership, health promotion, cessation, and research and evaluation.

The Communications and Public Affairs Branch (CPAB) ensures that communications and citizen engagement activities are coordinated and align with federal health priorities. CPAB is responsible for Break It Off, a tobacco cessation marketing campaign targeting young adult smokers.

Public Health Agency of Canada

The mission of PHAC focuses on promoting and protecting the health of Canadians. PHAC's role and responsibilities as part of the FTCS centre on supporting innovative ways to help people stop smoking. Through the tobacco stream of the Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease approach, PHAC has provided FTCS funding to organizations that have developed innovative ways to increase smoking cessation. All four of the projects that received funding during the reporting period focus on smoking cessation, including building health professional capacity in cessation training and delivery, integrating cessation into clinical settings and combining smoking cessation at the community level, with an established learn-to-run exercise program.

The Office of International Affairs for the Health Portfolio (OIA) is responsible for the strategic management of international issues within Health Canada and PHAC, and provides advice and support to the Minister of Health. OIA facilitates Canada's membership in the WHO FCTC and provides advice to advance Canada's engagement on international tobacco control issues. OIA pays Canada's voluntary assessed contribution to the WHO FCTC via the International Health Grants Program (IHGP) for the Health Portfolio.Footnote i

Public Safety Canada

Under the FTCS, Public Safety monitors contraband tobacco activity and related crime in support of evidence-based policy development, including information and policy advice to Finance Canada on the state of the contraband tobacco market. Public Safety administers a contribution agreement with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne to enhance capacity for First Nations policing to develop and share intelligence related to criminal activities related to contraband tobacco. FTCS contributions also fund an analyst position within the department for tobacco control activities.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The RCMP is responsible for the enforcement of laws within Canada related to the international movement of goods and has within its investigative mandate the illicit manufacture, distribution, or possession of contraband tobacco. Under the FTCS, the RCMP is responsible for monitoring and assessing the illicit market by way of analyst positions to capture and share intelligence about tobacco seizures and investigations of illicit tobacco activities. Funding is also used to improve border security in order to better detect and monitor illegal border intrusions. The RCMP also prepares an annual report on the contraband tobacco market, including national seizures and related trends, which is submitted to the Department of Finance and Health Canada.

Canada Border Services Agency

CBSA and the RCMP carry out the enforcement of the Customs Act and the Excise Act, 2001, which are the main enforcement tools in countering the various aspects of the illicit tobacco trade. With regards to tobacco control, the CBSA is primarily concerned with goods imported into Canada and the possession of products not properly reported, and monitors the domestic and international contraband tobacco market. It prepares regular assessments of the contraband tobacco market for the Department of Finance.

Canada Revenue Agency

CRA's main activity is to ensure compliance with the Excise Act, 2001, which governs federal taxation of tobacco products and regulates activities involving the manufacture, possession and sale of tobacco products in Canada. The agency undertakes regular audits and regulatory reviews of the tobacco manufacturers and tobacco dealers licensed under the Act. Funding from the FTCS has been used to allow for more audits and regulatory reviews, which includes visiting the operating premises of licensees to examine books and records. The CRA also ensures that the stamping and marking requirements of the Act are met.

2.3 Program Narrative

The FTCS provides a comprehensive approach to address tobacco control and aligns with the direction provided by the WHO and the international guidelines developed under the WHO FCTC.

The long-term expected outcome for the FTCS is a reduction in smoking prevalence among Canadians. In previous iterations of the Strategy, specific targets were set. The original goal of the FTCS set in 2001 was to reduce the smoking prevalence from the 1999 level of 25% to 20%. This was achieved by 2006.

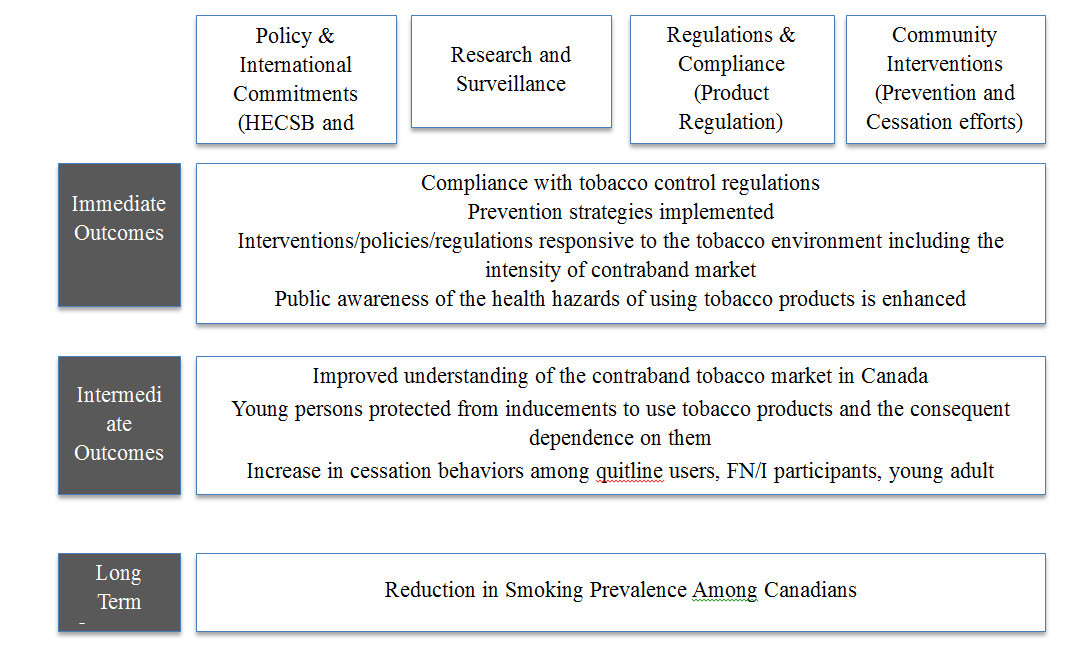

Four main activity areas contribute to the achievement of outcomes: policy and international commitments; research and surveillance; regulations and compliance; and community interventions (prevention and cessation efforts). Partner departments and agencies contribute to different activity areas as outlined in Table 2.

| Activity Area | Partner Department/Agency |

|---|---|

| Policy and International Commitments |

|

| Research and Surveillance |

|

| Regulations and Compliance |

|

| Community Interventions (prevention and cessation efforts) |

|

The immediate outputs and outcomes resulting from these activity areas are: compliance with the Tobacco Act and its regulations; implementation of prevention strategies; development of interventions/policies/regulations responsive to the tobacco environment, including the intensity of contraband market; and enhancement of the public awareness of the health hazards of using tobacco products.

Tobacco control regulations are found in both the Tobacco Act and the Excise Act, 2001. Prevention strategies are focussed on limiting the inducements for youth and others to begin smoking. However, mass media prevention campaigns have not been funded by the FTCS since 2009. Various interventions, policies and regulations have been implemented that support the overall objectives of the FTCS and address the contraband tobacco market.

The intermediate outcomes for the FTCS are: improved understanding of the contraband tobacco market in Canada; young persons and others protected from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them; an increase in cessation behaviors among Quitline users, First Nations and Inuit, young adult smokers, participants of PHAC-funded projects (including health care professionals and tobacco users in clinical and community settings), and the broader population. An improved understanding of the contraband tobacco market will assist the federal government in addressing the concerns raised by access to and availability of contraband tobacco and the impact on legitimate business. Preventing youth from starting to smoke has been a goal of the Strategy for many years. This helps reduce dependency, as well as the health risks, associated with smoking. Along with prevention, cessation is an important aspect of the Strategy. Current smokers require support from a variety of interventions to help users quit smoking and reduce the number of Canadians who smoke.

The intended reach for the Strategy is all Canadians. More recently there has also been a targeted focus on youth, and First Nations and Inuit communities.

The connection between these activity areas and the expected outcomes is depicted in the logic model (see Appendix 1). The evaluation assessed the degree to which the defined outputs and outcomes were being achieved over the evaluation time-frame.

2.4 Program Alignment and Resources

Within Health Canada, the activities of the FTCS are located under the Strategic Objective of "Health risks and benefits associated with food, products, substances, and environmental factors are appropriately managed and communicated to Canadians". The specific sub-program of the Program Alignment Architecture (PAA) is 2.5.1 Tobacco. Activities related to the First Nations and Inuit component align with the Healthy Living sub-sub-program, under sub-program 3.1.1: First Nations and Inuit Health Promotion and Disease Prevention.

From a horizontal perspective, the FTCS is also aligned with:

- Sub-program 1.2.3, Chronic (non-communicable) Disease and Injury Prevention(PHAC's PAA);

- Program 1.3, Countering Crime (Public Safety's PAA);

- Program 1.1, Police Operations (RCMP's PAA);

- Program 1.3, Risk Assessment and Security (CBSA's PAA); and

- Program: Collections, Compliance and Verification (CRA's PAA).

In total, the FTCS had a budget of $230 million over five years.

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

The scope of the evaluation covered the period from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2016, and included all activities of the federal partners, except for the PPSC as these were time-limited activities completed in 2012-13.

The evaluation aligns with the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Evaluation (2009) and considered the five core issues under the two themes of relevance and performance, as shown in Appendix 2. Corresponding to each of the core issues, specific questions were developed based on program considerations and these guided the evaluation process.

An outcome-based evaluation approach was used for the conduct of the evaluation to assess the progress made towards the achievement of the expected outcomes, whether there were any unintended consequences, and what lessons were learned.

The Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation (2009) also guided the identification of the evaluation design and data collection methods, so that the evaluation would meet the objectives and requirements of the policy. A non-experimental design was used based on the Evaluation Framework document, which detailed the evaluation strategy for this program and provided consistency in the collection of data to support the evaluation.

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, which included: a literature review, a document review, a financial data review, a performance data review, key informant interviews, three case studies, and a media scan. More specific details on the data collection and analysis methods used are detailed in Appendix 2. In addition, data were analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different methods listed above. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

An Evaluation Working Group comprised of representatives from the FTCS partner departments and agencies and led by Health Canada's Office of Audit and Evaluation, guided the evaluation. These representatives assisted in the data collection, and validation of findings and conclusions.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. The following table outlines the limitations encountered during this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings can be used with confidence to guide program planning and decision making.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Key informant interviews are retrospective in nature. | Interviews are retrospective in nature, providing recent perspective on past events. This can impact validity of assessing activities or results that may have changed over time. |

|

| Financial data structure is not linked to outputs or outcomes. | There is a limited ability to quantitatively assess efficiency and economy. | Used other lines of evidence, including key informant interviews and document reviews, to qualitatively assess efficiency and economy. |

| Most recent prevalence data from 2015 was not available. | Limits the ability to assess smoking prevalence trends for the timespan of the evaluation. | Used most recent data available (2013) which, when triangulated with other lines of evidence, provided the best possible information on smoking prevalence trends. |

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 – Continued Need for the Program

Although smoking prevalence has decreased over time to the 2013 level of 14.6%, the health impacts of tobacco use indicates a continued need for tobacco control to further reductions, particularly among at-risk populations.

Smoking prevalence in Canada has either decreased or remained constant every year it has been measured between 1985 (35%) and 2013 (14.6%).Endnote 1 Although the prevalence is lower than before, there are still 4.2 million Canadians over the age of 15 who report smoking either daily or occasionally. Smoking has considerable health impacts on those who smoke and those who are exposed to smoke, as well as a negative economic impact on all of Canada.

Tobacco use plays a causal role in over 10 different cancers (e.g., lung, mouth, stomach, liver) and is the primary cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – an inflammatory disease where the lungs are obstructed, making it difficult to breathe.Endnote 2 Many people who continue to smoke will die from smoking-related diseases. It is estimated that 23% of all deaths in Canada, and specifically, 31% of cancer-related deaths in 2010 were attributable to tobacco.Endnote 3 The direct costs (i.e., hospital care, drugs, physicians and other health care professionals, health research and other health care expenditures) and indirect costs (i.e., short- and long-term disability and premature mortality) of smoking in 2012 was estimated to be $18.4 billion.Endnote 4

The 2013 CTADS and the 2014-15 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) provide the most recent data available in regard to smoking prevalence in the ten provinces. Neither include data from the three territories. Despite the prohibition on furnishing tobacco to youth found in the Tobacco Act, in 2014-15, 3.4% of students in grades six to 12 (approximately 87,000 students) were current cigarette smokers, with 1.6% smoking daily and 1.9% smoking occasionally. As well, results from the 2013 CTADS indicated that 6.3% of youth between the ages of 15 and 17 reported smoking daily (2.3%) or occasionally (4%). The smoking rate increases to 17.7% for youth between 18 and 19 years of age with 9.6% smoking daily and 8.1% smoking occasionally. It is the change from the younger group to those 18 to 19 years olds that experienced the largest increase for both daily and occasional smokers.

First Nations communities (on-reserve) have a higher smoking rate than the general population of Canada. The most recent comparable data available comes from the 2008-2010 Regional Health Survey (RHS), the 2012 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), the 2009 Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS) and the 2013 CTADS. It should be noted that data from CTUMS and CTADS does not include the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. These regions contain the highest proportion of Canadians who identify as Aboriginal.Endnote 5 The RHS reported that 43% of adults living in First Nations communities were daily smokers and 13.7% were occasional smokers. Younger adults (age 18 to 29) in First Nations communities, however, had the highest proportion of daily smokers (51.5%) and occasional smokers (15.9%). The APS reported that 52.2% of Canada's Inuit population aged 15 years and older smoke daily and 9.4% smoke occasionally. In contrast, the 2009 CTUMS reported that 14% of Canadians aged 15+ were daily smokers and 4% were occasional smokers.

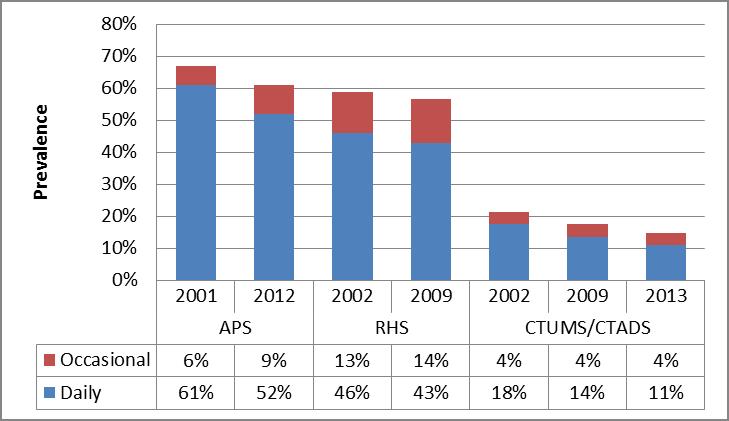

From a health equity perspective, it is concerning that the prevalence rate for the rest of Canada is dropping by a greater degree than that of First Nations communities, as seen in Figure 1. Comparing RHS data from 2002-2003 and CTUMS data from 2002 to the data from 2009, the proportion of daily smokers from First Nations communities dropped from 46% to 43% while the proportion of daily smokers surveyed through CTUMS dropped from 18% to 14%.

Figure 1: Smoking Prevalence Rates in Canada

Figure 1 – Text description

This figure depicts a stacked bar graph showing the percentage of individuals who reported smoking daily and occasionally on the Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) and the Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey or Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTUMS/CTADS).

The following dates are listed along the x-axis: 2001 and 2012 for the APS, 2002 and 2009 for the RHS and 2002, 2009 and 2013 for the CTUMS/CTADS. The y-axis shows smoking prevalence in percentage with a scale from 0% to 80%.

The graph shows the following information for APS respondents. In 2001, 61% reported smoking daily and 6% reported smoking occasionally. In 2012, 52% reported smoking daily and 9% reported smoking occasionally.

The graph shows the following information for RHS respondents. In 2002, 46% reported smoking daily and 13% reported smoking occasionally. In 2009, 43% reported smoking daily and 14% reported smoking occasionally.

The graph shows the following information for CTUMS/CTADS respondents. In 2002, 18% reported smoking daily and 4% reported smoking occasionally. In 2009, 14% reported smoking daily and 4% reported smoking occasionally. In 2013, 11% reported smoking daily and 4% reported smoking occasionally.

Evidence suggests that individuals who stop smoking will improve their health, reduce their risk of chronic disease and increase their life expectancy.Endnote 6 Health Canada has compiled research on the benefits of quitting smoking. These include: within 8 hours of quitting, carbon dioxide levels in the blood return to normal; within 24 hours of quitting, the risk of heart attack is reduced; within 1 to 9 months of quitting, stronger lungs, improved breathing and less coughing occurs; after 1 year of quitting, the risk of coronary heart disease is reduced; and after 5 years of quitting, the risk of stroke is reduced to normal. It is estimated that smokers in Canada between the ages of 35 and 69 who died in 2010 lost an average of 24 years, and smokers over 69 years of age lost an average of 7 years of life.Endnote 7

Along with the health risks associated with tobacco, there are additional concerns related to contraband tobacco. Contraband tobacco has an impact on businesses (e.g., tobacco companies, convenience stores) who suffer the loss of sales of legal cigarettes, as well as a loss of revenue for the Government of Canada and the provinces and territories through taxation. Contraband tobacco is often sold in packaging that contravenes the Tobacco Act and does not provide health warning messages aimed at smokers and at rates that do not include all applicable taxes. The lower cost of contraband tobacco undermines the government approach to "…tax tobacco products at a high and sustainable level to discourage their consumption."Endnote 8 Contraband tobacco has also been linked to other illegal activities.Endnote 9

The general tobacco environment is fluid, with changes stemming from industry and public usage patterns. In addition to the ongoing activities the FTCS undertakes, it also has made efforts to anticipate and address future needs. These activities are necessary to be proactive, rather than reactive to change.

The FTCS has identified and addressed several anticipated needs. For example, PHAC's Grants and Contributions program, the Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease has provided funding to advance evidence-based, innovative projects that target tobacco cessation efforts, demonstrate measurable results and have the potential to be expanded across the country or to other target populations.

In addition, the Tobacco Control Program (TCP) has undertaken a national project-based planning approach to assess industry's business practices, identify areas of non-compliance and means to address changing industrial practices. The TCP has also initiated a program to identify and assess compliance of online retailers and the use of social media and smart phone applications for tobacco promotion.

One specific need identified for potential future involvement by the TCP and interviewees is the compliance and enforcement of vaping products. The TCP notes that in the future, it may be involved pan-regionally with compliance promotion activities and market intelligence gathering. However, at this point, vaping products do not fall under the purview of the FTCS.

The federal government has several on-going obligations related to tobacco control that they must continue to fulfill. Areas of core federal responsibility include the provision of health services and benefits to First Nations and Inuit populations, as well as addressing contraband and illicit trade. Surveillance, monitoring and enforcement of illicit tobacco activity are shared responsibilities between the federal agencies of the CBSA and the RCMP. The CBSA is responsible for all ports of entry and the RCMP is responsible for activity between the ports of entry and domestically. The federal government has a goal of achieving an increased level of health in Indigenous communities as outlined in the Federal Indian Health Policy (1979), and thus it is particularly concerned with the disproportionally high rate of smoking for First Nations and Inuit communities. The federal government is committed to providing financial resources to the provinces and territories to meet the additional demand for quitline services as a result of certain tobacco product packages featuring health warning messages that include a pan-Canadian Quitline phone number and web address as per the Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars).

Finally, the federal government is obligated to undertake tobacco control activities as Party to the WHO FCTC, which Canada ratified in 2004. Countries that have ratified the WHO FCTC have committed to implementing strong tobacco control policies as a means of protecting the health of their populations. To advance the FCTC, the WHO has introduced a package of technical measures and resources to reflect and support the demand reduction provisions of the Framework. These measures include: monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies; protecting people from tobacco smoke; offering to help quit tobacco use; warning of the dangers to tobacco; enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; maintaining effective tax rates on tobacco; and protecting public health policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry. As Party to the WHO FCTC, Canada also participates in governing body meetings (i.e., Conferences of the Parties), reports biennially on compliance, and is a financial contributor through the Voluntary Assessed Contributions.

4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 – Alignment with Government Priorities

The objectives of the FTCS are aligned with the priorities of the FTCS federal partners and the broader federal government.

Since the renewal of the Federal Tobacco Control StrategyEndnote 10 in 2012, the strategy's objectives have been:

- preventing children and youth from starting to smoke;

- helping people to quit smoking;

- helping Canadians protect themselves from second-hand smoke; and,

- regulating the manufacture, sale, labeling and promotion of tobacco products by administering the Tobacco Act.

Federal budgets have included a focus on various aspects of tobacco control. For example:

- Budget 2014, Implementation of the RCMP Anti-Contraband Tobacco Force funded through internal reallocation.Endnote 11,Endnote 12,Endnote 13

- Budget 2014, Increase in tobacco rates to eliminate lower rate for domestic tobacco products for sale in duty free shop market.Endnote 14

- Budget 2013, Excise duty rate on "other manufactured tobacco" increased to be more consistent with the rate for cigarettes.Endnote 15

- Budget 2013, Enhancing the ability to combat contraband tobacco by providing funding to Public Safety for First Nations police services.Endnote 16

In 2015, the Prime Minister's Office's statement on National Non-Smoking Week noted the Government of Canada's commitment to "helping Canadians become and stay smoke-free" and that they are working with a range of partners to "educate Canadians about the dangers of smoking, help smokers quit, and discourage Canadians, especially young people, from starting to smoke".Endnote 17

The commitment to discourage Canadians from taking up smoking and to encourage smokers to quit was reinforced as a top priority in the Minister of Health Mandate Letter,Endnote 18 which instructed the Minister of Health to "introduce plain packaging requirements for tobacco products, similar to those in Australia and the United Kingdom." Further to this, the Minister of Health announced the launch of public consultations on tobacco plain packaging on May 31, 2016, which coincided with the WHO's World No Tobacco Day.Endnote 19,Endnote 20

One of the targets for the WHO's Sustainable Development Goals (Health) is to "strengthen the implementation of the WHO FCTC in all countries, as appropriate."Endnote 21 Meeting the goals of the FCTC and reporting to the Conference of the Parties have been key international commitments and obligations since Canada ratified the convention in 2004. Canada played a leadership role in the development of the Protocol on Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products in 2012 (the Protocol is not yet in force)Endnote 22 and in FCTC Guidelines for Implementation in 2014 (Articles 9 and 10 on the Regulation of Tobacco Products)Endnote 23 and recommendations (i.e., sustainable measures to strengthen the implementation of the Convention) developed under the FCTC.

Tobacco control related issues (e.g., plain packaging, health professional access to information, contraband tobacco, taxation) are a priority for all of the partner departments and agencies of the FTCS.

One of Health Canada's priorities is to "strengthen openness and transparency as modernization of health protection legislation, regulation and delivery continues"Endnote 24, and one of its strategic outcomes is that "health risks and benefits associated with food, products, substances, and environmental factors are appropriately managed and communicated to Canadians".Endnote 25 Health Canada also has Tobacco as one of the sub-programs in its PAA.

PHAC's strategic priority to provide "leadership on health promotion and disease prevention,"Endnote 26 is foundational to its focus on addressing risk factors, such as smoking, which have been shown to increase the potential for disease.Endnote 27 The Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Promote Healthy Living and Prevent Chronic Disease approach is captured under the Agency's Chronic (non-communicable) Disease and Injury sub-program. The multi-sectoral partnerships administer funding from sources including the FTCS and features population health approaches that address common risk and protective factors for chronic diseases, including smoking cessation. The multi-sectoral partnerships are based on the premise that no one sector alone can meaningfully address the causes of chronic disease, and that a wide range of partners are required to identify and generate sustainable solutions to improve the health of the population.Endnote 28

The CRA does not have a direct priority regarding tobacco; however, it is active in ensuring that taxes imposed on tobacco products under the Excise Act, 2001 are paid. The CRA also conducts compliance activities on domestic tobacco manufacturers, as per the Excise Tax Act, 2001Endnote 29 and works with stakeholders to ensure that tobacco control measures are effective.

Organizations within the Public Safety portfolio do not have priorities specific to tobacco, however, the Public Safety's strategic outcome is "A Safe and Resilient Canada"Endnote 30 which includes the sub-sub-program of Serious and Organized Crime. One of the foci of this sub-sub-program is contraband tobacco, a topic the former Minister of Public Safety raised in a number of news releases.Endnote 31,Endnote 32 As part of the Public Safety portfolio; the RCMP includes a focus on organized crime, as found in its organizational priority of Serious and Organized Crime,Endnote 33 and has an Anti-Contraband Force.Endnote 34 While the RCMP does not focus specifically on any commodity, the Federal Policing program targets organized crime groups and networks, which may be involved in the contraband tobacco market. Similarly, the CBSA priority of Secure the Border StrategicallyEndnote 35 includes a focus on the risk of contraband entering Canada. This risk is addressed by the CBSA's Intelligence sub-program which collects, analyses and shares intelligence with law enforcement partners, including intelligence on organized crime and smuggling.

4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 – Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Tobacco control is a responsibility of the federal government, as well as other levels of government.

All levels of government play a role in tobacco control. The policy authority for the FTCS was renewed in 2012 for a period of five years (2012-2017), and aligns federal roles and responsibilities along four core functions: policy development and international commitments, research and surveillance, regulations and compliance, and community interventions (Appendix 1).

The FTCS funds activities that relate to the administration of the federal Tobacco Act, which emphasizes that "the health of Canadians needs to be protected in light of conclusive evidence implicating tobacco use in the incidence of numerous debilitating and fatal diseases." Among other considerations, this details a role for the federal government "to protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them; to protect the health of young persons by restricting access to tobacco products; and, to enhance public awareness of the health hazards of using tobacco products."Endnote 36 The FTCS also funds activities that align with the federal Excise Act, 2001, which imposes federal excise duty on tobacco products and regulates the issuance of tobacco licenses to tobacco manufacturers and dealers; the stamping and marking of tobacco products; and, restrictions on the possession of tobacco products that are not stamped. In addition, the FTCS specifically funds the RCMP and CBSA to monitor the contraband tobacco products they seize as a result of exercising their role in enforcing federal laws, which is funded by monies outside of the FTCS.

At the international level, Canada is Party to the WHO FCTC.Endnote 37 The FTCS fully addresses Article 5 of the FCTC which mandates that "each Party shall develop, implement, periodically update and review comprehensive multi-sectoral national tobacco control strategies, plans and programmes in accordance with this Convention and the protocols to which it is a Party."Endnote 38 According to Health Canada's most current report to the Conference of the Parties on its implementation of the FCTC (April 2016), nearly all of the roles expected of Canada in controlling tobacco in a comprehensive manner have been implemented. However, a review of Health Canada's submitted reports shows that some specific FCTC-related expectations do remain unfulfilled. For example, a self-assessment revealed that Canada does not earmark any percentage of taxation income for funding the FTCS or tobacco control; does not prohibit the sales of tobacco products by minors; and does not prohibit the sale of tobacco products from vending machines.Endnote 39,Endnote 40 In support of Article 5.3, Health Canada's engagement with the tobacco industry is limited to instances where it is necessary to effectively regulate the industry and tobacco products. However, in a shadow report prepared by the Global Tobacco Forum, concerns were raised about the engagement of other departments, agencies or semi/quasi-public institutions with the tobacco industry. Instances of tobacco companies' donations to events and the inclusion of tobacco stocks into broader pension government of Canada do not align with the guideline recommendations of the FCTC.

Canada supports the Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI) under the Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health cluster of the WHO. The TFI strives to provide global policy leadership by encouraging mobilization at all levels of society. Canada has provided financial and technical expertise to activities carried out under this initiative.

Provincial, territorial and municipal governments continue to play an increasingly important role in advancing tobacco control. Stronger federal leadership would enhance uniformity and efficiency.

Provincial and municipal governments play an ever important role in advancing tobacco control.Endnote 41 All provinces and territories have tobacco control statutes in force, as well as strategies that vary in approach and focus to address smoking prevention, cessation, and to protect the public from the effects of second-hand smoke. Input from key informants was consistent in noting that stronger federal leadership – particularly on regulatory matters – would serve to enhance uniformity and provide a consistent level of protection across Canada. For example, some provincial health ministers, have noted that the lack of federal leadership on addressing menthol flavours in tobacco,Endnote 42,Endnote 43 and emerging issues such as vaping products, has led to a legislative patchwork of provincial actions. This was echoed by the majority of key informants. Since 2012, several provinces have passed and/or amended tobacco control laws to address matters that the federal government has not covered. The provinces of Alberta, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Québec and Ontario have amended their laws to add menthol to a list of banned flavours for tobacco products; meanwhile, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island have started to address emerging issues like water pipes and vaping products. In some cases, the tobacco industry in Canada has taken issue with the provinces building upon gaps in federal legislation, and has filed lawsuits alleging in court documents that banning menthol in tobacco is outside a province's jurisdiction.Endnote 44,Endnote 45 In addition, the provinces continue to expand their legislative focus on defining smoke-free places to address matters related to second-hand smoke (e.g., patios, public housing and private motor vehicles with children present).

Provinces and Territories are also actively engaged in contraband tobacco issues. For over 30 years, the annual Interprovincial and Territorial Investigations Council Tobacco Workshop has brought together Provincial/Territorial and Federal partners involved in the enforcement of tobacco and tobacco products. The purpose of this workshop is to facilitate cooperation and the exchange of information necessary to combat contraband with a focus on interprovincial and international tax avoidance. The 2016 Workshop is co-hosted by the Ontario Ministry of Finance.

Building upon provincial legislationEndnote 46 and best practices,Endnote 47 municipalities in Ontario are attempting to further control tobacco and recover the cost of enforcement inspections through "Tobacco Retail Dealer's Permits". For example, the City of Ottawa administers a "Tobacco Vendor Licence" that is required for any business selling tobacco products, and the cost of this licence in 2016 is approximately $861 annually.Endnote 48 As one measure of impact, some merchants in Ottawa have publically noted that that the need for such a licence (as well as their increasing fees over time) is prompting them to reconsider the value of selling tobacco on their store shelves next to other alternatives.Endnote 49 Accordingly, the City of Ottawa has seen a significant reduction in the number of tobacco vendors, decreasing from approximately 800 in 2008 to 495 in 2016. The licensing fees collected by the City of Ottawa cannot yield any profits for the city, and are used to support the funding of necessary public health inspections, as well as to investigate tobacco control issues raised by the general public.

With funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, Canada's Non-Smokers Rights Association has developed and maintains a publically accessible database of smoke-free laws across Canada. A review of this database shows that between January 1, 2012 and April 30, 2016, approximately 115 municipalities across Canada passed and/or amended smoke-free restrictions at the local level. Furthermore, approximately 33% of these municipalities have passed and/or amended their by-laws to include a focus on vaping products.Endnote 50

4.4 Performance: Issue #4 – Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

4.4.1 To what extent have the immediate outcomes been achieved?

Immediate outcome #1: Compliance with tobacco control regulations

Across Canada, the tobacco market has decreased its non-compliance with the provisions of both the Tobacco Act and the Excise Act, 2001. Continued and consistent monitoring from Health Canada and CRA has ensured low non-compliance.

The Tobacco Act regulates the manufacture, sale, labelling and promotion of tobacco products. Health Canada undertakes compliance promotion, compliance monitoring and enforcement in support of the Tobacco Act and its regulations. These compliance and enforcement activities address the manufacturing/importing sector, the retail sector and industry reporting. Overall, key informants felt that the constant and on-going monitoring was the main reason for the relatively low non-compliance rates with the Tobacco Act and its regulations.

In Canada, there are approximately 60 manufacturers and importers actively involved in the sale of tobacco products, with the majority located in Ontario and Quebec. For these manufacturers and importers the following measures are monitored for compliance:

- The cigarette ignition propensity standard, as set out in the Cigarette Ignition Propensity Regulations (CIPR);

- The prohibition on the use of certain additives in cigarettes, little cigars and blunt wraps, as per sections 5.1 and 5.2 of the Tobacco Act (Prohibited additives);

- The prohibition on promoting, by means of cigarette, little cigar and blunt wrap packaging, the presence of additives that cannot be in used in said products, as per section 23.1 of the Tobacco Act (Prohibition of Promotion of Banned Additives on Packaging);

- The minimum packaging requirements for cigarettes, little cigars and blunt wrapsFootnote ii, as per section 10.1 of the Tobacco Act (Minimum Packaging); and,

- The labelling requirements (specifically, health warnings, toxic emissions statements, and health information messages) as set out in the Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) (TPLR).

- The reporting requirements (information on tobacco products including manufacturing procedures, sales, ingredients, research activities, emissions, constituents and promotional activities) as set out under the Tobacco Reporting Regulations.

Overall, the rate of non-compliance is very low, and there has been decreased non-compliance since 2012-13. The TPLR is the most recent regulation; it was adopted in September 2011. It was noted by internal key informants, that it generally takes two years for full compliance once new regulations come into force. In 2015-16, the compliance assessment of the Minimum Packaging regulations was targeted at little cigar packaging. The minimum packaging requirement for cigarettes has been in effect since 1997, and compliance was consistently at 100%.

| Provisions | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Samples Analyzed | Non-Compliance Rate (%) | Number of Samples Analyzed | Non-Compliance Rate (%) | Number of Samples Analyzed | Non-Compliance Rate (%) | Number of Samples Analyzed | Non-Compliance Rate (%) | |

| Cigarette Ignition Propensity Regulations | 108 | 0% | 20 | 0% | 20 | 0% | 20 | 0% |

| Prohibited Additives | 60 | 0% | 318 | 0% | 197 | 0% | 100 | 0% |

| Prohibition of Promotion of Banned Additives on Packaging | 200 | 5% | 468 | 3% | 436 | 0% | 110 | 0% |

| Minimum Packaging | 200 | 5% | 262 | 3% | 247 | 0% | 79Table 4 note a | 0% |

| Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars) | 211 | 35% | 488 | 21% | 457 | 9% | 382 | 4% |

Source: Annual Report on Compliance and Enforcement Activities (Tobacco Control) Table 4 notes

|

||||||||

In 2014-15, 20 warning letters were issued to manufacturers or importers. The most common reason for warning letters was alleged violations to labelling requirements. The increase in non-compliance with regards to promotion of banned additives on packaging is most likely due to the coming into force of new requirements for certain other types of cigars.

For retailers of tobacco products, Health Canada monitors the compliance with the following measures:

- Minimum packaging requirements;

- Prohibition of promotion of banned additives on packaging;

- Labelling requirements; and

- Prohibited promotional activities.

There are between 30,000 to 35,000 points of sale for tobacco products across Canada. Internal stakeholders noted that there are challenges with retail inspections in remote and rural areas, as the inspectors are based at the regional offices in urban centres. Inspections are conducted using a retail inspection model that incorporates several parameters, including number of retailers per region, relative distribution of urban versus rural retail locations, and a cyclical enforcement schedule of five to six years. In recent years, the number of inspections conducted at the retail level has declined. Some key informants reported concern that the current level of retail inspection coverage adequately covers the points of sale.

Monitoring of retailers on First Nations and Inuit communities is not consistently done across regions. However, inspectors are reaching out to retailers within First Nations and Inuit communities to increase awareness of, and compliance with, these regulations. Communities that are involved with the First Nations and Inuit component of the FTCS are supporting this through their own activities. Some communities are conducting their own monitoring activities and developing their own materials to support retailers in complying with the Tobacco Act. Details on inspections within First Nations and Inuit communities are not available at this time, and are not included in the calculation of compliance rates.

A retailer is identified as non-compliant if at least one case of non-compliance with a key measure is noted during an inspection. In 2014-15, enforcement actions included seizures at retail (216) and the issuing of warning letters (8). Letters may have made reference to a number of instances and/or type of non-compliance.

| Fiscal Year | Number of Inspections | Non-compliance Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 9782 | 16% |

| 2013-14 | 7724 | 14% |

| 2014-15 | 6774 | 12% |

| 2015-16 | 6719 | 13% |

| Source: Annual Report on Compliance and Enforcement Activities (Tobacco Control) | ||

It is important to note that in fiscal year 2012-2013, Health Canada eliminated its retail inspections for the federal tobacco sales-to-youth provisions and financial support to 7 of the 10 provinces for similar activities. In a study published in 2014, Health Canada found that 85% of retailers refused to sell cigarettes to underage Canadians. This finding was statistically unchanged from 2009 (84%). Provincial key informants expressed disappointment that the federal government no longer conducts this inspection as it is a federal law. However, legal age for tobacco sales is also regulated at the provincial level. In 6 out of 10 provinces, the legal age is higher than the federal minimum age of 18.

The Tobacco Reporting Regulations requires tobacco manufacturers and importers to submit regular reports to the Minister of Health Canada that include sales data, manufacturing information, information on the ingredients used in their products, constituents and emissions information, as well as information on their research and promotional activities. The percentage of incomplete reports has declined since 2012-2013. In fiscal year 2015-2016, Health Canada reviewed 1485 reports from manufacturers and importers. Of the reports reviewed, 131 (8.8%) were determined to be incomplete, and a total of 58 letters of deficiency were issued. In a number of cases, one letter referred to more than one deficiency. Some cases are transferred to RORB for further enforcement actions.

| Fiscal Year | Number of reports reviewed | Number and Percentage of Reports Deemed Incomplete | Number of Letters of Deficiency sent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-2013 | 1490 | 213 (14%) | 107 |

| 2013-2014 | 1186 | 139 (12%) | 108 |

| 2014-2015 | 1607 | 172 (11%) | 81 |

| 2015-2016 | 1485 | 131 (8.8%) | 58 |

| Source: Annual Report on Compliance and Enforcement Activities (Tobacco Control) | |||

Under the Excise Act, 2001, tobacco manufacturers and tobacco dealers are licensed by the CRA. Between 2012-13 and 2015-16 the number of tobacco manufacturer licensees across Canada has remained consistent at approximately 24. The number of tobacco dealer licensees (TDL) doubled from 5 TDL's in 2012-13 to 10 in 2015-16 and authorized premises for both tobacco manufacturers and dealers has increased from 45 to 48. CRA officials have unlimited and unannounced access to operating premises as a requirement of the tobacco license. CRA conducts both audits and regulatory reviews on an ongoing basis. In 2015-16, 13 audits and 208 regulatory reviews were completed with FTCS funding. This has maintained full coverage of licensees with an increased focus on specific regulations.

CRA conducts compliance activities on each tobacco licensee operating location numerous times a year (as a result of increased funding through the FTCS to the inspection program), and is permitted unfettered access as a condition of the license. There is a high rate of compliance amongst tobacco licensees with the provisions of the Excise Act, 2001. There were no reported instances of licenses being revoked between 2012-13 and 2015-16. Compliance activities have resulted in audit assessments and administrative penalties, but this has also declined from a high of 6 audit assessments totalling and $1.5 million in 2013-14. In 2015-16, compliance activities resulted in three audit assessments totaling $11,427. Frequent monitoring ensures that issues or concerns are caught and rectified quickly. Privacy provisions have limited the sharing of information on tobacco licensees between Health Canada and the CRA. This has not impacted the CRA inspections, but has created some barriers for Health Canada as the latter is not always aware of the status of tobacco licensees.

Tobacco sales create significant revenue for the federal government. Excise duty revenues from domestically manufactured tobacco products were $1.8B in 2014-15. This has increased by $300M since 2012-13, despite similar or lower actual sales. The increase was attributed to the increase in the rate of excise duty on cigarettes through Budget 2014.

Immediate outcome #2: Prevention strategies implemented

Prevention has been addressed through the Tobacco Act prohibiting sales to youth; prohibiting select additives; restricting tobacco promotion; and health warning labelling. Many stakeholders felt that prevention activities that have been undertaken by other levels of government have created a patchwork of efforts.

As most smokers begin smoking by age 19, the FTCS has focussed on the prevention of smoking initiation by youth.Endnote 51 Research has shown that it is more effective to prevent people from starting to smoke, rather than helping them to quit smoking, given the challenges with cessation and addiction.Endnote 52 This perspective was also supported by external stakeholders.

Specific prohibitions set out in the Tobacco Act and its regulations aim to prevent smoking initiation for youth by lessening the appeal of smoking. These include the restrictions of certain additives, such as flavours that make tobacco products more appealing to youth; the prohibition on the promotion of tobacco products that can be appealing to young persons, such as lifestyle advertising; the inclusion of pictorial health warnings that raise awareness of the risks of smoking; and, the prohibition on sales of tobacco products to young persons.

As mentioned previously, Health Canada no longer actively conducts retail inspections for the federal tobacco sales-to-youth provisions. A retail behavior study from 2014 showed that 85% of retailers refused to sell cigarettes to underage Canadians. In contrast, 34% of youth smokers who were too young to purchase cigarettes legally in their province of residence reported that they had purchased cigarettes from a regular legal source, such as a store.Endnote 53 Thirty-two percent of youth smokers obtained their cigarettes from a family member or friend.Endnote 54 Many key informants believe that youth begin smoking in their homes, and more prevention needs to be focussed on this area.

One of the six essential elements of the First Nations and Inuit component of the FTCS is prevention, which falls under the health promotion pillar. Under the essential element of prevention, communities are initiating activities with a strong focus on youth, including training youth as peer counsellors. Social marketing campaigns are aimed at preventing commercial tobacco use and misuse. Another common component of the prevention essential element is the support for smoke-free by-laws and the reduction of commercial tobacco use in homes (e.g., blue light competitions to identify smoke free spaces).

The majority of external stakeholders felt that the FTCS was not conducting any prevention strategies, and that the original iteration of the strategy (2001-2006) had been much more active in this regard. The prevention strategy examples provided by stakeholders were mass media focussed; they did not recognize the prevention efforts in regulations and legislation. It was felt that Canada was no longer a leader in national mass media prevention campaigns. The external stakeholders also felt that by limiting the prevention activities to regulations and legislation, there were no attempts to address the inequities in smoking prevalence across Canada. There was some concern that marginalized groups were not being impacted by prevention strategies. The original proposal for the marketing campaign within this round of the FTCS included youth prevention, along with cessation. However, due to limited funding, youth cessation became the sole objective of the campaign.

Other levels of governments have addressed smoking prevention through various strategies, such as the "Smoking, suffering, dying" awareness campaign in Quebec, and Smoke-Free Ontario. As these strategies are not consistent across the country, there is seen to be a patchwork of efforts that is causing inequity and inefficiencies.

Immediate outcome #3: Interventions/policies/regulations responsive to the tobacco environment including the intensity of contraband market

Partner departments and agencies, mainly Health Canada and Public Safety, have developed interventions, policies and regulations that are responsive to the tobacco environment. However, there are some areas of the tobacco environment, such as the increasing popularity of vaping products, where the federal government has not been as responsive as other levels of government to date.