Horizontal Evaluation of the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy: Evaluation Report

Final report

August 2023

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

Table of contents

List of acronyms

- 2SLGBTQIA+

- Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and/or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, and additional sexual orientations and gender identities

- CADS

- Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- BC

- British Columbia

- BSO

- Border services officer

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CCSA

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

- CDSA

- Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

- CDSS

- Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy

- CHIRPP

- Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program

- CIHI

- Canadian Institute for Health Information

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CNS

- Central nervous system

- CND

- UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

- CPADS

- Canadian Postsecondary Education Alcohol and Drug use Survey

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRISM

- Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse

- CSAR

- Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research

- CSC

- Correctional Service Canada

- CTADS

- Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey

- CSTADS

- Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey

- DAS

- Drug Analysis Services

- DG

- Director General

- DTC

- Drug Treatment Court

- DTCFP

- Drug Treatment Court Funding Program

- ETF

- Emergency Treatment Fund

- FASD

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- FINTRAC

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- FP

- Federal Policing

- FPT

- Federal/Provincial/Territorial

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- HC

- Health Canada

- HPFB

- Health Products and Food Branch

- HRF

- Harm Reduction Fund

- IEWG

- Interdepartmental evaluation working group

- iOAT

- Injection opioid agonist treatment

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- JUS

- Department of Justice Canada

- M

- Million

- NADS

- National Anti-Drug Strategy

- OAE

- Office of Audit and Evaluation

- OAT

- Opioid agonist therapy

- OPTIMA

- A Pragmatic Randomized Control Trial Comparing Models of Care in the Management of Prescription Opioid Misuse

- OUD

- Opioid Use Disorder

- PBC

- Parole Board of Canada

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PMERC

- Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Results Committee

- PPDU

- Problematic Prescription Drug Use

- PPSC

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PSPC

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- PT

- Provincial/Territorial

- PWLLE

- Persons with Lived and Living Experience

- PWUDs

- People who use drugs

- QoL

- Quality of Life

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- SCS

- Supervised Consumption Sites

- SDG

- Sustainable Development Goals

- SGBA+

- Sex and Gender Based Analysis Plus

- StatsCan

- Statistics Canada

- STBBI

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- SUAP

- Substance Use and Addictions Program

Executive summary

Profile and evaluation scope

Canada is experiencing an unprecedented rate of substance use-related deaths and harms due to a number of complex, interrelated factors. The Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS), which was first announced in 2016, sets out the federal government's comprehensive, collaborative, compassionate, and evidence-based approach to drug policy that focuses on substance use as a public health issue. The CDSS replaced the National Anti-Drug Strategy (NADS), which was established in 2006, and the lead changed from the Department of Justice to Health Canada. From 2017 to 2022, Health Canada coordinated federal investments and activities across the full spectrum of legal and illegal substances under 4 pillars: prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement. In 2018, the federal government launched the "Addressing the Opioid Crisis" initiative (the Opioid Initiative), a complementary horizontal initiative that received some reallocated funding from the CDSS. The CDSS and the Opioid Initiative are overseen by the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health, as of 2020-21. Health Canada (HC) is the lead department for both initiatives and supported by 15 other federal departments and agencies.

This evaluation looked at all funded partners' activities from 2017-18 to 2021-22 under both horizontal initiatives and focused on progress made toward delivering on Pillar objectives and shared outcomes (see Figure 1), including HC's Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) and PHAC's Harm Reduction Fund activities to address Financial Administration Act requirements. However, activities related to tobacco and cannabis, including SUAP projects for these substances, were excluded from this evaluation as there were separate evaluations assessing activities related to these 2 substances.

Figure 1 - Text description

Executive Summary: This diagram shows four boxes representing each CDSS pillar: prevention, treatment, harm reduction and enforcement. Underneath the four boxes lays a rectangle which represents the evidence-base as supporting the four pillars. The diagram also defines the pillar’s expected outcomes as follows:

- Prevention: Canadians make better-informed choices around substances use and risks to reduce harms

- Treatment: Treatment and recovery services and systems are easily accessible, comprehensive, and appropriately tailored to the needs of individuals.

- Harm Reduction: Reduction in risk-taking behavior among people who use drugs or substances.

- Enforcement: Decreased diversion of drugs away from authorized activities and reduced size and profitability of the illegal drug market.

- Evidence Base: Data and research evidence on drugs, and emerging drug trends, are used by members of the federal Health Portfolio and their partners.

On the right hand side of the four pillar boxes shows a fifth box outlining the Addressing the Opioid Crisis Horizontal Initiative themes.

- Theme 1: Additional prevention and treatment interventions

- Theme 2: Addressing stigma

- Theme 3: Taking action at Canada’s border

- Theme 4: Enhancing the evidence base

What we found

Overall, the CDSS and Opioid Initiative have helped to frame substance use as a public health matter and contributed to expanding access to harm reduction and treatment services across Canada through regulatory actions, the SUAP and other activities funded through ISC's Mental Wellness Program, among others. Despite notable efforts to reduce and minimize opioid-related harms and deaths, the number of substance use-related harms and deaths continue to be alarming. The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated the overdose crisis due to increased substance use in isolation, reduced access to support services, and a more potent and toxic illegal drug supply. Increased feelings of isolation, stress, and anxiety have also played a significant role increasing harms related to alcohol use.

Recognizing that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on substance use trends during the evaluation period, the CDSS quickly adapted its interventions to address the rise in overdoses through various initiatives, including regulatory actions. However, given the urgency of the crisis, prevention activities and collaboration to address the root causes of substance use were limited and much of the Strategy's focus has consequently been on illegal drugs. While the overdose crisis should continue to be a priority, evidence strongly suggests that other substances could be better addressed under the CDSS. Specifically, given the long-term health and economic impacts linked to alcohol, alcohol use was identified as a gap in the Strategy and as an area of risk and need that requires prevention efforts, including targeted approaches for specific populations like youth.

Moreover, the CDSS has supported ongoing efforts to decrease diversion of drugs through regulatory actions like the accelerated scheduling of novel precursor chemicals, compliance promotion, and compliance and enforcement actions in relation to licensed dealers and pharmacies. However, the increasing toxicity of illegal drugs in Canada is an ongoing issue that is not only leading to an increase in overdoses, but also further complicating the federal government's ability to address the crisis through public health and public safety efforts. Specifically, there are challenges with respect to the increasing illegal importation of precursor chemicals used in the production of illegal drugs in Canada and the regulatory regime's capacity to keep pace with the composition of chemicals produced and sold by organized crime groups.

Finally, the federal government has made significant progress in supporting the development of a wide range of evidence-based tools for members of the federal Health Portfolio and their partners, including treatment guidelines for opioid use disorders. However, gaps were identified in surveillance and data monitoring, in particular with respect to disaggregated surveillance data. There is also limited information, such as a lack of baseline data and targets, to effectively measure the Strategy's impact in addressing drug and substance use as a health and social issue.

The evaluation also examined the CDSS governance structure and found that, despite positive collaboration between horizontal partners, there are still challenges within the structure that limit effective coordination. Opportunities for improvement included clarifying the program mandate and roles and responsibilities of each partner, increasing engagement and discussion opportunities for other federal partners and stakeholders to ensure all views are included, and providing meeting materials earlier to allow other government departments to meet their internal briefing needs.

In terms of external engagement, the establishment of the Persons with Lived and Living Experience (PWLLE) Council was a key success. However, greater representation of people along the spectrum of substance use treatment and recovery is needed. Representation of people with more diverse backgrounds is also necessary, including more meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities and partners.

Recommendations

- Address the prevalence of alcohol use and harms [Health Canada and PHAC].

- Enhance prevention and outreach efforts for higher-risk groups to address the root causes of substance use [Health Canada and PHAC].

- Contribute towards addressing evidence gaps to get a more comprehensive national and regional picture of substance use issues and the domestic illegal drug supply, as well as a better understanding of the impact of services and supports [Health Canada and PHAC, in collaboration with all CDSS partners].

- Enhance the performance measurement strategy to align better with the CDSS's outcomes, including a review of performance indicators to focus more on the impacts of activities [Health Canada, in collaboration with all CDSS partners].

- Review the governance structure to clarify roles and responsibilities, and streamline it where possible, while still facilitating ongoing information sharing between partners and all levels of government [Health Canada, in collaboration with all CDSS partners].

- Work to better understand the domestic illegal drug supply, including its growing toxicity, and the tools that are needed to support more effective law, border, and health responses [RCMP and Public Safety Canada, in collaboration with Health Canada and CBSA.

Evaluation description

Description of the horizontal initiatives

About the Strategy

The Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS), which was announced in December 2016, is the Government of Canada's national and public health-based approach to substance use policy. It replaced the National Anti-Drug Strategy (NADS), which was launched in 2006. Harm reduction was added as a key pillar of the strategy, alongside prevention, treatment, and enforcement. These pillars were also to be supported by a strong evidence base. The CDSS covers a broad range of legal and illegal substances, including cannabis, alcohol, and opioids, among others. In 2018, the federal government launched the "Addressing the Opioid Crisis" initiative (the Opioid Initiative), a complementary horizontal initiative that received some reallocated funding from the CDSS. The CDSS and the Opioid Initiative are overseen by the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health, as of 2020-21. Health Canada (HC) is the lead department for both initiatives and supported by 15 other federal departments and agencies.

Federal partners

- Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

- Canada Revenue Agency (CRA)

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)

- Correctional Service Canada (CSC)

- Justice Canada (JUS)

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC)

- Global Affairs Canada (GAC)

- Indigenous Services Canada (ISC)

- Parole Board of Canada (PBC)

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC)

- Public Safety Canada (PS)

- Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC)

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Statistics Canada (StatsCan)

Strategy context

The evaluation focused on funding allocated to the CDSS from Budget 2017 and the Opioid Initiative from Budget 2018. Between fiscal year 2017-18 and FY 2021-22, approximately $698.20 million was allocated in planned spending across the 2 initiatives. Subsequent federal budgets made further funding commitments to address the overdose crisis, in addition to these initiatives (see Figure 2). In total, between 2017 and 2022, over $800 million was allocated across several federal departments to directly address the overdose crisis, including funding for the CDSS and the Opioid Initiative, as well as for complementary programs and activities.Footnote 1. While these additional funding sources and complementary programs are outside the scope of the evaluation, they directly affect substance use policy, since the CDSS is the guiding framework for the Government of Canada's response to the toxic drug and overdose crisis.

Figure 2 - Text description

This image shows a timeline of federal funding allocated across departments for the overdose crisis between 2017 and 2022, presented from left to right.

- Budget 2017:

- Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy

- Urgent Support to Provinces and Territories

- Budget 2018:

- Addressing the Opioid Crisis

- Emergency Treatment Fund

- Budget 2019:

- Funding for Actions to Protect Canadians and Prevent Overdose Deaths

- 2020 Fall Economic Statement

- Budget 2021:

- Addressing the Opioid Crisis

- Budget 2022

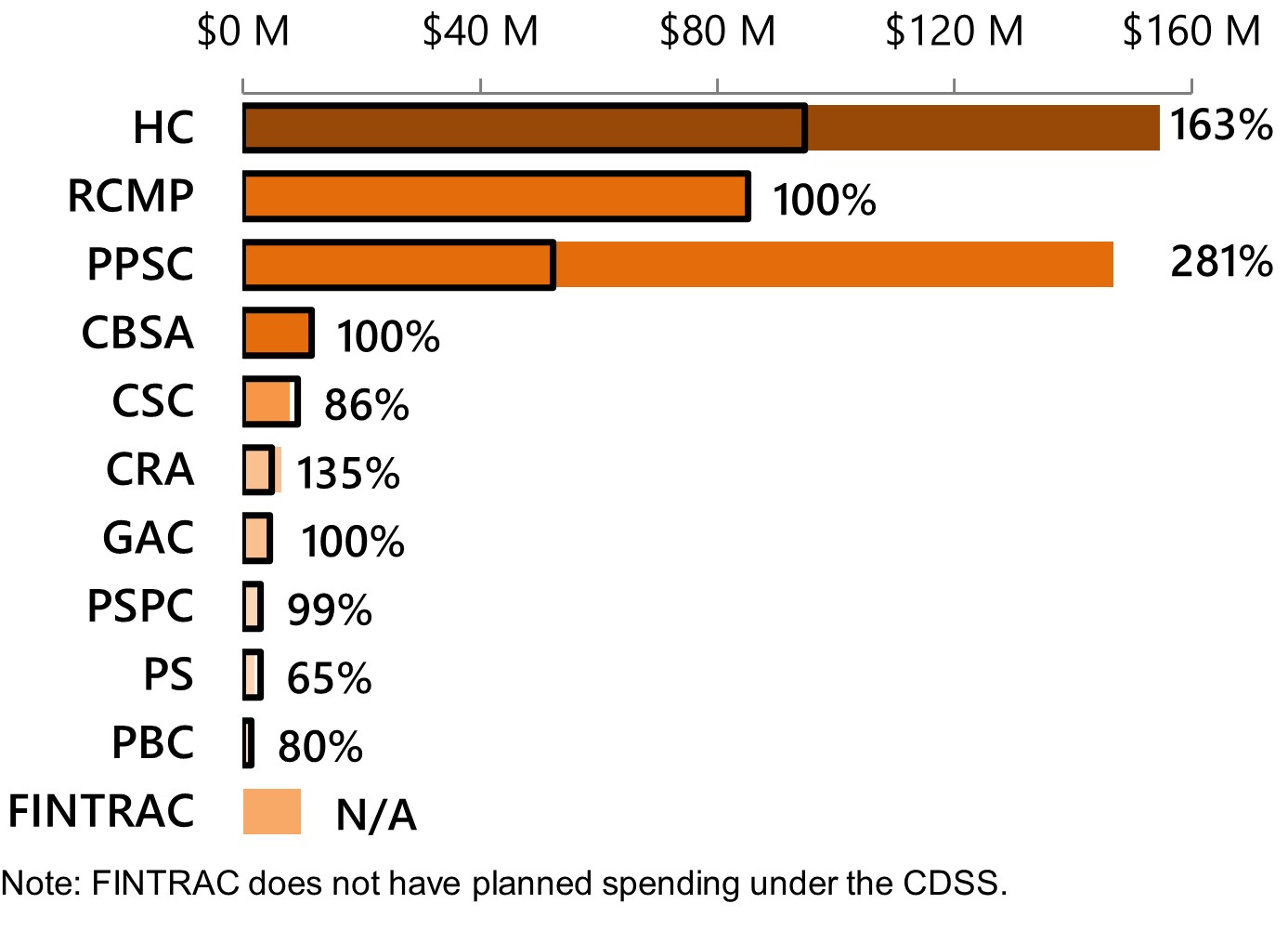

Financial summary

Over the past 5 fiscal years of the CDSS (2017-18 to 2021-22), the Strategy spent a total of $741.66 (120% of planned amount) across all pillars, excluding internal services costs. Over the past 4 fiscal years of the Opioid Initiative (2018-19 to 2021-22), it spent $78.46M (97% of the planned amount) across all themes, excluding internal service costs. See Annex B for a breakdown of planned spending versus actual spending for both horizontal initiatives, by fiscal year and by organization.

Figure 3 - Text description

This graph is a horizontal bar chart showing the CDSS actual spending by pillar. It shows the percentage of total actual spending from fiscal years 2017-18 to 2021-22 by pillar as follows:

| Category | Spending | Percentage of total actual spending | Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enforcement | $432.69 million | 58% | HC, CBSA, CRA, CSC, GAC, FINTRAC, PBC, PPSC, PS, PSPC, RCMP |

| Prevention | $134.18 million | 18% | HC, ISC, RCMP |

| Treatment | $93.06 million | 13% | CIHR, ISC, JUS |

| Harm Reduction | $61.60 million | 8% | HC, ISC, PHAC |

| Evidence Base | $20.14 million | 3% | HC, PHAC, CIHR |

Amounts exclude internal service costs and lead role.

Figure 4 - Text description

This graph is a horizontal bar chart showing the Opioid Initiative actual spending by theme. It shows the percentage of total actual spending from fiscal years 2018-19 to 2021-22 by theme as follows:

| Category | Spending | Percentage of total actual spending | Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addressing prevention and treatment interventions | $25.99 million | 33% | HC |

| Addressing stigma | $19.31 million | 25% | HC, PS |

| Taking action at Canada's borders | $19.30 million | 25% | CBSA, PS |

| Enhancing the evidence base | $13.86 million | 18% | PHAC, Statcan |

Amounts exclude internal service costs and lead role.

Evaluation approach

Scope

The evaluation was conducted to assess the impact of CDSS activities from 2017-18 to 2021-22 and Opioid Initiative activities from 2018-19 to 2021-22. It was led by Health Canada and PHAC's Office of Audit and Evaluation, in collaboration with funded partners. The evaluation focused on all pillars covering a range of activities including grants and contributions (G&Cs) programs. In particular, the Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP), and the Harm Reduction Fund were included to address Financial Administration Act requirements. However, activities related to tobacco and cannabis, including SUAP projects for these substances, were excluded from this evaluation as there were separate evaluations assessing activities related to these 2 substances.

Evaluation questions

- What progress has been made towards delivering on prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement objectives?

- Were resources used efficiently and effectively? Are the strategy's resources directed towards the greatest areas of risk and need?

- Is there governance in place to support effective collaboration among horizontal partners in support of the prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement objectives?

- Is there governance in place to support effective collaboration with external partners and stakeholders in support of the prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and enforcement objectives?

Findings in the report are presented by each Pillar's expected outcomes, as defined in the latest available logic model (see Annex C). This is followed by an impact assessment of the shared long-term outcomes and a summary of governance and engagement. Findings related to evidence, resources, and areas of greatest risk and need are discussed throughout.

For evaluation methodology, limitations and related mitigation strategies, and evaluation governance, see Annex A.

Evaluation findings

Prevention

Key takeaways

Over the past 5 fiscal years, Health Canada, under the CDSS and the Opioid Initiative, has raised awareness of substance related harms through national public advertising campaigns, educational engagements, international and national health awareness days or weeks, social media, and community-led projects funded by the SUAP. Still, there is more work to be done to generate behavioural changes among Canadians to prevent substance use-related harms. There are also opportunities to improve Health Canada's collaborative efforts to address the root causes of substance use. Data gaps have impeded assessment of progress for other federal partners funded under the Prevention Pillar.

Short-term outcome 1: Increase knowledge to help Canadians make informed choices and reduce risks and harms of drug and substance use.

Public education campaigns

Health Canada's national public education campaigns on substance use appear to have widespread reach. From fall 2018 to spring 2022, Health Canada ran a 5-phase national advertising campaign focused on 3 topics: opioid awareness, awareness of the harms of substance use stigma, and the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act.

The 2020-21 campaign surpassed its targets, with 98.9 million ad impressions and increased opioid-related web traffic on Canada.ca by 60%.Footnote 2. The 2021-22 campaign had a relatively smaller reach with 42.4 million impressions. Health Canada staff clarified that the lower count was due to that phase of the campaign taking a more targeted focus on young and middle-aged men, particularly men in trades, as surveillance data shows that this is the group experiencing the highest rates of opioid overdoses and substance use in Canada.Footnote 3 However, disaggregated data is not available to describe the reach to subgroups of the Canadian population, such as reach by age group, gender, or other identity factors.

| Survey response | 2021 | 2019 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certain or pretty sure what opioids are | 67% | 69% | 63% |

| Not at all familiar with at least 1 of the opioids listed | 21% | 16% | 18% |

| Very aware of Canada's opioid crisis | 19% | 25% | 28% |

| Felt the opioid crisis is very or somewhat serious in their community | 61% | 70% | 65% |

While these campaigns appeared to be widely distributed, knowledge of drug and substance use risks and harms among people in Canada remains largely unchanged over the past 5 years. Health Canada commissioned a series of public opinion research studies that have shown minimal changes in public opioid awareness since 2017. According to the 2021 follow up study of a representative sample of Canadians aged 13 and older, awareness of opioids and their risks has remained fairly stable, with a slight peak in 2019 (see Table 1).

The surveys in the research studies did not have a question about awareness of federal public education campaigns, although some focus group participants in the 2019 study shared without being prompted that they had seen Government of Canada public education ads about opioids.Footnote 6. While a few external representatives interviewed for the evaluation mentioned seeing federal public awareness campaigns, a similar proportion of interviewees from community and regional organizations or governments did not feel the campaigns were sufficiently visible. Many interviewees, including several Health Canada representatives, flagged gaps in public awareness activities for substances other than opioids, most notably for alcohol.

Finally, several internal and external interviewees identified a need to improve substance use prevention strategies targeting youth and children. However, it should be noted that Health Canada has been running the Know More Opioids Footnote 7 awareness program for youth since April 2018 (see the following section). Additionally, although not funded under the CDSS Prevention Pillar, PHAC developed a set of resources for preventing substance-related harms among Canadian youth through action within school communities. In August 2021, PHAC published a policy paper Footnote 8 that describes issues related to youth substance use from a public health perspective and published a "Blueprint for Action" Footnote 9 that outlines practical approaches for schools and community organizations to prevent substance-related harms among youth.

Public engagement activities

As a federal partner funded under the Prevention Pillar of the CDSS, the RCMP's Federal Policing (FP) program developed education products to increase awareness of drugs and illegal substances among stakeholders, conducted outreach and engagement efforts, and built new partnerships.Footnote 10

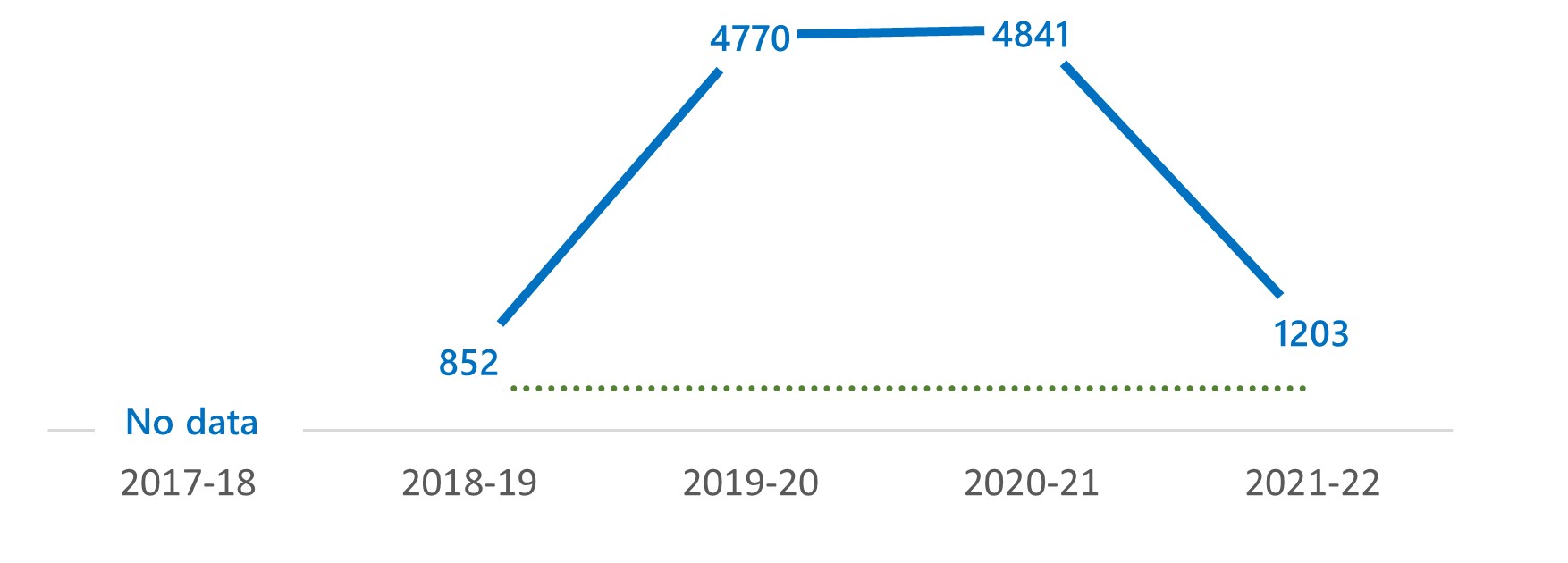

The RCMP committed to meeting 5 performance indicators related to increasing awareness of drugs and illegal substances. For example, in the first 3 years of the evaluation period, the RCMP met its target of 50% with respect to the percentage of partners and stakeholders demonstrating increased awareness of illegal drugs. Moreover, regarding the number of awareness products developed, the RCMP reported meeting its target of 5 products once in the past 5 years, missing their target by only 1 for most years. Despite this, they were still able to produce a total of 20 drug-related awareness products over the evaluation period, including presentations, fact sheets, and news reports on topics such as suspicious chemical precursor transactions, illegal synthetic drug labs, methamphetamine, and fentanyl. Finally, for the indicator of number of stakeholders reached, the RCMP successfully achieved its target every year (see Figure 5). It should be noted that the 2019-20 numbers are much higher than those reported in previous years, given that this sum includes internal website downloads relating to several synthetic drug products. As such the number of downloads does not necessarily represent the unique number of stakeholders reached.

Figure 5 - Text description

Figure 5 is a line graph showing the number of stakeholders reached through RCMP public engagement activities by fiscal year between 2017-18 and 2021-22:

- 2017-18: No data

- 2018-19: 852

- 2019-20: 4770

- 2020-21: 4841

- 2021-22: 1203

- No target

Meanwhile, as part of the Opioid Initiative, Health Canada implemented the "Know More: Opioid public awareness" program targeting Canadian students and youth. Between April 2018 and June 2022, the "Know More" program was involved in 1,148 high school sessions, 68 post-secondary school events, and 43 events and festivals, resulting in over 169,900 participant interactionsFootnote 11. In 2020, the program was adapted for virtual formats in light of pandemic-related public health measures, further expanding its reach of the program.Footnote 12 However, there were no post-event evaluations to measure changes in attitudes or awareness among program participants.

Substance Use and Addictions Program

What is SUAP?

The Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) is a Health Canada G&Cs program that supports the CDSS, the Cannabis Program, and Canada's Tobacco Strategy.

SUAP funds community-led pilot projects to develop evidence or proof of concept for innovative service delivery models to prevent or address substance related harms.

SUAP projects target Canadians at greatest substance use risk or who may face barriers accessing services, including racialized and Indigenous populations, young adults and youth, various gender and 2SLGBTQIA+ populations, and people who face housing insecurity or are street-involved.

From 2017-18 to 2021-22, Health Canada reported spending nearly $96 million for the CDSS and another $26 million for the Opioid Initiative through SUAP G&Cs. The SUAP funds projects across Canada to help prevent, reduce, or treat the harms associated with range of controlled drugs and substances. While SUAP funding is categorized under the Prevention Pillar for reporting purposes, SUAP projects also address outcomes under Treatment and Harm Reduction. SUAP does not allocate or track funding by CDSS pillar as the program is also funded through other initiatives and budget commitments beyond the CDSS.

Currently, in 2023, SUAP funds approximately 290 active projects, with 15% focused on prevention. It should be noted that about 9% of SUAP projects focus on tobacco and cannabis and are out of scope for the evaluation. According to program reporting for fiscal year 2021-22, SUAP's 138 controlled substances projects demonstrated extensive reach and impact on knowledge and awareness among its various target audiences. In the most recent reporting period, SUAP projects developed 59,558 awareness and education products and provided 38,753 learning opportunities, though these included projects related to cannabis and tobacco which were out of scope for this evaluation. Educational products and services were accessed 9.7 million times by people in Canada. Finally, 54% of controlled substances projects met their targets to generate intent among their audiences to use the knowledge and skills they acquired in relation to substance use.

Short-term outcome 2: Increase awareness and collaboration to address the root causes of substance use.

Collaboration with federal partners

Health Canada collaborated with a range of federal organizations, including those not funded under the CDSS, to address root causes and social determinants of health that influence levels of substance use and substance use-related harms, including homelessness, trauma, and mental illness.

For example, housing is an important social determinant of health as rates of addiction and co-occurring mental health challenges are higher among those experiencing chronic homelessness.Footnote 13 Furthermore, people who use substances are at a higher risk of becoming homelessFootnote 14,Footnote 15 due to policies, social norms, and stigma regarding substance use and mental health. To this effect, Health Canada works with Infrastructure Canada, an unfunded CDSS partner, in CDSS working groups and governance committees. Infrastructure Canada oversees a community-based national homelessness strategy that includes considerations for substance use prevention and treatment.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, there appear to be mixed views on the extent to which the CDSS has increased awareness and collaboration to address the root causes of substance use. Many interviewees, including over a third of external interviewees, felt that the CDSS has not advanced this issue.

In interviews with CDSS federal partners, a few interviewees described good interdepartmental collaboration on addressing root causes or social determinants of substance use. However, several internal and external interviews talked about challenges due to conflicting or uncoordinated roles. In a similar vein, a few internal and external interviewees described challenges arising from prevention activities being the purview of provincial, territorial, or municipal governments, not the federal government. See the Governance and Engagement section for further discussion on intergovernmental and external collaborations.

The most cited area for improvement was around collaboration to address homelessness and mental illness. Correspondingly, several interviewees described opportunities to implement prevention interventions using an intersectional approach, such as linking to mental health or counselling programs, or through joint policy initiatives.

Opioid use risk management

Prescription opioids are an important option for management of chronic pain, a health issue that affects an estimated 1 in 5 people in Canada.Footnote 17 However, harmful use of opioids can lead to opioid use disorders (OUD). Personal and social factors, such as trauma and fragmented mental health care, can increase likelihood of development of OUD and worsen opioid-related harms.Footnote 18,Footnote 19,Footnote 20,Footnote 21.

Adverse outcomes of substance use, unintentional overdose, and death resulting from inappropriate prescribing, and harmful use of opioids have emerged as major public health problems. In response to these challenges, Health Canada has conducted a variety of activities to promote and monitor the safety and effectiveness of prescription opioid products, including patient and health care professional education and awareness.

In 2018, Health Canada amended the Food and Drug RegulationsFootnote 22 to prevent and mitigate risks from prescription opioid-related harms through various initiatives, including the requirement for manufacturers to submit a mandatory Canadian Specific Opioid-targeted Risk Management Plan (CSO-tRMP) for prescription opioidsFootnote 23, and the requirement for a warning sticker and patient information handoutFootnote 24 to be provided with prescription opioids at the time of dispensing.

During the evaluation, Health Canada exceeded its CDSS performance indicator target in terms of the percentage of pharmacies inspected that are deemed to be compliant with the CDSA and its regulationsfor all fiscal years except 2018-19 and 2019-20 (see Figure 6). This may be due to compliance framework updates introduced in 2017-18, which meant pharmacies needed time to adjust to the new requirements. Furthermore, the target was not met in 2019-20 due to Health Canada's continued focus on the inspection of pharmacies with a history of non-compliance. This risk-based, targeted inspection approach led to a lower percentage of industry compliance than planned.

Figure 6 - Text description

Figure 6 is a line graph showing the percentage of pharmacies inspected deemed to be compliant with the CDSA and its regulations by fiscal year between 2017-18 and 2021-22:

- 2017-18: 87%

- 2018-19: 75%

- 2019-20: 67%

- 2020-21: 84%

- 2021-22: 83%

- Target: 80%

First Nations and Inuit Mental Wellness Program

ISC used Prevention Pillar funding to support prevention, harm reduction, and treatment activities and services in First Nations and Inuit communities. These include substance use case management supports for prescription drugs, prevention, and training activities. At this time, no information on the performance of the Mental Wellness Program is available since ISC does not have indicators under the Prevention Pillar. Additionally, it should be noted that an evaluation of ISC's Mental Wellness Program is currently underway.

Medium-term outcome 1: Canadians make better informed choices around substance use and risks to reduce harms.

Recent surveillance data shows that rates of substance use were relatively stable until the pandemic, although behaviours associated with higher risks of harms had increased. The 2019 Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS) found that consumption of illegal drugs among people in Canada remains low with only about 4% having used at least 1 illegal drug, though this proportion is relatively unchanged when compared to results from the 2017 Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS).Footnote 25 The 2019 survey also found that alcohol continues to be the most consumed substance in Canada. Meanwhile, rates of higher-risk use of substances and associated harms appear to have increased since 2017, particularly for young adults (see Table 2).

It is important to note that these surveys predate the COVID-19 pandemic, which posed significant challenges to individuals and to the health care system and led to increased substance use and likely heightened substance-related harms. Recent surveillance data shows that opioid-related hospitalizations and deaths in Canada have increased significantly since 2020.Footnote 26 A 2021 PHAC survey also found that many respondents had increased their substance use during the pandemic.Footnote 27

| Survey question | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Exceeding low-risk drinking guidelines - chronic |

2019 | 2017 |

| Overall population | 17.6% | 16.1% |

| Age 20-24 | 26.2% | 24.1% |

| Problematic use of stimulants | 2019 | 2017 |

| Overall population | 0.8% | 0.3% |

| Age 20-24 | 4.8% | 1.9% |

| Problematic use of any pharmaceuticals | 2019 | 2017 |

| Overall population | 1.6% | 1.2% |

| Age 20-24 | 5.5% | 3.6% |

| Any drug harm to self | 2019 | 2017 |

| Overall population | 4.5% | 4.1% |

| Age 20-24 | 13.8% | 10.1% |

Health Canada-commissioned research studies also found that people have continued to engage in opioid use behaviour that increases risk of harm. In 2021, a third (34%) of study respondents who reported use of non-prescribed opioids said they obtained them from a relative or friend who has a prescription, a 4% decrease from 2017.Footnote 31 Notably, only two-thirds (65%) of respondents in 2021 said they "definitely would no longer take non-prescribed opioids if they discovered they contained fentanyl," a 4% increase since 2017. Other questions related to risk behaviours, such as safe storage of opioids and appropriate medication disposal, also remained relatively stable between 2017 and 2021.

These minimal changes since 2017 to rates of high-risk substance use suggest further prevention efforts are required. Several interviewees, particularly federal partners, described opportunities to increase use of policy measures to change substance use outcomes. They cite the success of tobacco regulations and the opportunity to apply similar measures to reduce harmful consumption of other substances, particularly alcohol. however, challenges in changing substance use outcomes are not unique to the CDSS. Studies increasingly show that an individual's intent and ability to address harmful substance use is affected by inequities and differences in lived experiences. As such, public health interventions tend to be more effective when they focus on changing the physical, material, and social environments, rather than individual behaviour.Footnote 32

Area of risk and need: Harms from alcohol use

Alcohol is the second leading cause of death from substance use in Canada after tobacco. Footnote 33, Footnote 34 Research from 2023 found that, in Canada, alcohol use incurs higher costs and harms than other substances. This includes health care costs, criminal justice system costs, losses in productivity, and other direct costs (see Figure 7). Footnote 35 Yet, interviewees and scientific literature note challenges to preventing alcohol use-related harms due to the normalization of alcohol and the lack of awareness of its harms. Footnote 36

Research and interviews reveal policy opportunities to prevent some of the health and social costs of alcohol use. Participants in a 2018 consultation held by Health Canada made several suggestions, including the following:Footnote 37

- Increasing awareness of alcohol harms, including alcohol-impaired driving;

- Instituting legislative and regulatory changes that control the affordability and availability of alcohol;

- Developing a national alcohol strategy; and

- Restricting alcohol marketing and advertisements, including through social media.

It is important to note that alcohol harms do not have an equal impact on everyone. Alcohol use and related health and psychosocial effects vary by sex, gender, and social determinants of health. For example, research has found women and females assigned at birth are more at risk than men and males assigned at birth to face alcohol-related harms due to biological differences in susceptibility to intoxication and disease, and to alcohol-related violence against women.Footnote 38 Future prevention and awareness efforts need to take into account the differential impacts in the harms associated with alcohol consumption between different populations. Finally, the federal government received a failing grade (37%) in the Canadian Alcohol Policy Evaluation's (CAPE) most recent assessment of the effectiveness of government policies in reducing alcohol-related harms in Canada and identified several recommendations to improve their score, including the development of an alcohol strategy.Footnote 39

Source: Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group (www.csuch.ca/explore-the-data) CNS = Central Nervous System

Figure 7 - Text description

Figure 7 is a stacked bar chart graph that shows the total costs (in billions) related to substance use in Canada from 2007 to 2020, by substance and cost type. Each stacked bar represents a substance, and each stack bar is broken down by cost type. Cost types are labelled by colour and are represented as follows for each substance:

| Substance | Health care costs | Lost productivity costs | Criminal justice costs | Other direct costs | Total cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | $6.27 billion | $7.87 billion | $3.97 billion | $1.57 billion | $19.67 billion (40.09%) |

| Tobacco | $5.43 billion | $5.25 billion | $5.5 million | $471.1 million | $11.15 billion (22.74%) |

| Cannabis | $380.6 million | $490.9 million | $1.07 billion | $443 million | $2.38 billion (4.85%) |

| Opioids | $519.0 million | $5.26 billion | $1.18 billion | $163.2 million | $7.07 billion (14.42%) |

| Other Central Nervous System (CNS) depressants | $240.6 million | $489.6 million | $344.8 million | $294.2 million | $1.37 billion (2.79%) |

| Cocaine | $184.3 million | $1.41 billion | $2.41 billion | $149 million | $4.16 billion (8.48%) |

| Other Central Nervous System (CNS) stimulants | $359.1 million | $1.54 billion | $928.9 million | $200.5 million | $3.03 billion (6.18%) |

| Other substances | $25 million | $57.2 million | $117.3 million | $20.7 million | $0.22 billion (0.45%) |

Treatment

Key takeaways

Overall, evidence shows that the CDSS and Opioid Initiative have expanded access to evidence-based treatment services and systems, though inequities still exist in terms of accessibility to treatment. Specifically, interviews and documents identified a number of barriers to accessing treatment and pointed to a need for more integrated and recovery-focused care.

Short-term outcome 3: Federal actions support the expansion of evidence-based treatment services and systems.

Emergency Treatment Fund

It should be noted that provinces and territories (PT) are primarily responsible for the delivery of treatment services, but that the Government of Canada provides some substance use services and supports to certain federal client populations, including First Nations people living on reserves, Inuit, Canadian Armed Forces members, veterans, and federally incarcerated populations.

Though not funded under the CDSS or Opioid Initiative, the establishment of Health Canada's Emergency Treatment Fund (ETF) contributed towards Treatment Pillar objectives during the evaluation period. The ETF was announced as part of Budget 2018 funding to provide additional support to help address the opioid overdose crisis.

ETF provided 1-time emergency funding of $150M for provinces and territories (PT) to improve access to evidence-based treatment services over 3 years, which when cost-matched by provinces and territories, was expected to result in an investment of over $300M.Footnote 40 Interviewed provincial and territorial representatives noted an appreciation for the funding provided through the ETF, which supported an overall increase in access to treatment services. According to annual reports from PTs, ETF investments have improved access to treatment services across Canada, with reports indicating that progress has been made on the following issues:

- Reducing treatment wait times;

- Increasing the number of treatment beds;

- Increasing Rapid Access Addiction Medicine clinics;

- Improving access to culturally appropriate care for Indigenous communities;

- Expanding access to virtual supports;

- Supporting providers through training opportunities;

- Addressing methamphetamine use; and

- Improving health systems and building community-level capacity.

Substance Use and Addictions Program

Health Canada also helped to increase availability of Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) in communities across Canada through the SUAP. For example, SUAP funding helped open the first injection Opioid Agonist Treatment (iOAT) clinic in New Brunswick and enabled the clinic to double its intake target and capacity within the first year of receiving funding. Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) is a form of therapy for opioid users that consists of injection of lower-potency opioids such as methadone, Suboxone (buprenorphine-naloxone), and Sublocade (injectable buprenorphine).

Interviewees also highlighted how SUAP has expanded access to treatment services at the community level throughout multiple jurisdictions. It should be noted that interviewees often did not distinguish treatment from harm reduction, but rather spoke of their activities and impacts in relation to one another. Among the 92 new SUAP projects in 2021, 9% focused on treatment, which included 3 projects explicitly focused on treatment and 2 OAT projects.

Overall, internal, and external interviewees agreed that federal actions have supported the expansion of evidence-based treatment services and systems through the ETF and SUAP funding, but that the sustainability of services and research activities is largely dependant on federal funding which is time-limited.

Highlight: COVID-19 rapid response

In May 2020, CIHR provided the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse (CRISM) with $1 million to undertake urgent activities to support people who use drugs (PWUDs), decision-makers and care providers in light of COVID-19. This included the creation of 6 national guidance documents and a rapid assessment of the challenges faced by PWUDs during the COVID-19 pandemic to guide future policy decisions

Enhancing the evidence base for treatment

While only a very small proportion of internal and external interviewees spoke about evidence around substance use treatment, a few internal and external interviewees observed successes in expanding such evidence under the CDSS. The most cited examples were tied to work by the CRISM, including their development of national guidelines, large clinical trials, and rapid response evidence documents during the pandemic.

Supporting treatment guideline development

The CDSS also supported the development of treatment guidelines for health care providers, including clinical guidelines for OAT and national treatment guidelines for opioid use disorders, and delivered it to physicians across Canada. The guidelines provide health care professionals with recommendations on managing opioid use and were developed through extensive consultations with experts and people with lived experience.

In addition to CDSS funding, CIHR provided $17 million in new funding in 2022 to support the next phase of CRISM (Phase II) and launched 2 new funding opportunities to support the creation of a Network Coordinating Centre to support and coordinate governance, training, capacity building and knowledge mobilization across CRISM; as well as an Indigenous Engagement Platform to support Indigenous engagement across the CRISM Network.

A Pragmatic Randomized Control Trial Comparing Models of Care in the Management of Prescription Opioid Misuse (OPTIMA)

OPTIMA is the first randomized clinical trial to compare the relative effectiveness of buprenorphine naloxone (flexible take-home doses) versus methadone (daily witnessed ingestion) models of OAT for people who use drugs in real-world clinical settings. Results from the OPTIMA not only provide valuable evidence around treatment effectiveness of OAT for those with prescription opioid use disorders, but resulting publications are expected to generate additional evidence on issues of patient retention in treatment, best practices around administration of OAT, and cover other important areas like mental health, cost effectiveness of OAT, and overdose data related to different treatment options.Footnote 41

Since the completion of the trial in March 2020, the CRISM Network has continued to target key stakeholder groups, including PWLLE who are seeking OAT, health care providers and key stakeholders involved in policy and programs for opioid use disorder care, and community advocacy groups in substance use, for knowledge mobilization and dissemination activities related to the trial findings.

Alcohol policy and intervention research

In March 2022, under the CDSS, the CIHR in partnership with the Canadian Cancer Society, funded 20 research projects to expand the evidence base and to inform practical policies and interventions to reduce alcohol-related harms in Canada. This research is expected to generate data and evidence that will increase the knowledge base on alcohol-related harms and how to prevent and treat them, as well as inform future larger-scale research projects.Footnote 42

Nonetheless, a few academics and subject matter expert interviewees cited the need for enhanced national standards, guidelines, and strategies to guide the use of treatment evidence. A few CDSS federal partners also described gaps in treatment evidence, particularly in research on populations disproportionally affected by substance-related harms.

Medium-term outcome 2: Treatment and recovery services and systems are easily accessible, comprehensive and appropriately tailored to the needs of individuals.

Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs)

DTCs provide an alternative to incarceration by offering the offender an opportunity to participate in a court-monitored and community-based drug treatment program. DTCs are supported under the CDSS and funded under the Justice Canada administered Drug Treatment Court Funding Program (DTCFP). In 2021-22, 69% of participants stayed in federally-funded DTC programs for more than 6 months, exceeding the expected target of 50%. While the expected target was not met in the first 2 years of the CDSS, there was a steady increase in the DTC participant retention rate, indicating that the program is achieving its intended goals under the Strategy to support alternative ways of responding to the causes and consequences of drug-related offenses (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 - Text description

Figure 8 is a line graph showing the drug treatment court participant retention rate (in percentage), by fiscal year between 2017-18 and 2021-22:

- 2017-18: 37%

- 2018-19: 46%

- 2019-20: 58%

- 2020-21: 68%

- 2021-22: 69%

- Target: 50%

However, certain groups, including women, Indigenous, and racialized Canadians, are seen as being underrepresented in DTC programs. A recent evaluation of Justice Canada's DTC Funding Program found that some stakeholders would like to see greater flexibility in the eligibility criteria, as well as increased use of experimentation. These findings led to a recommendation to consider ways to support DTCs in efforts to include groups who may be under-represented or experiencing barriers to access.Footnote 43

While not specifically funded under the CDSS, PPSC is also a key component of DTCs. Specifically, PPSC prosecutors work with judges, defence counsel, treatment providers, and others to collaboratively address the issues raised by the conduct of offenders appearing before these courts. In some cases, PPSC agrees to reduce sentences for traffickers with substance use disorders who have demonstrated that they are addressing their disorder through treatment, as well as the continued option of attending the DTC.Footnote 44

Expanding access to treatment for First Nations and Inuit communities

Indigenous populations in Canada are disproportionately affected by the overdose crisis and the use of opioids and other substances. ISC has been an instrumental partner in supporting the Strategy's treatment objectives as they relate to expanding access to services and supports for First Nations and Inuit communities in Canada.

Specifically, ISC supports a number of ongoing activities including treatment centre accreditation and certification incentive funding for substance use workers. Moreover, the CDSS also provided the initial funding for Mental Wellness Team pilots and continues to provide $2 million in ongoing funding for the Mental Wellness Program. In addition to these activities, ISC also supports OAT wraparound services in First Nations and Inuit communities. Wraparound services work to address underlying or associated issues through counselling and traditional practices. While barriers to accessing treatment still exist, there was a significant increase in the number of sites funded by ISC that offer OAT wraparound services after the first year of CDSS funding, and then a steady increase in subsequent years during the evaluation period (see Figure 9). As indicated by interviewees, this funding was important in leveraging other sources of funding to support wraparound services. Interviews also indicate that funding has been impactful in raising awareness about harm reduction and increasing availability of services. Highlights from interviews include bulk purchases of Naloxone when availability was limited, the launch of OAT wraparound services, and related training for staff.

![Figure 9: Number of sites [funded by ISC] offering OAT wraparound services, 2017-18 to 2020-21](/content/dam/hc-sc/images/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/evaluation/canadian-drugs-substances-strategy/fig9-en.jpg)

Figure 9 - Text description

Figure 9 is a line graph showing the number of sites (funded by Indigenous Services Canada) offering opioid agonist therapy (OAT) wraparound services by fiscal year between 2017-18 and 2021-22:

- 2017-18: 15 sites

- 2018-19: 58 sites

- 2019-20: 68 sites

- 2020-21: 72 sites

- 2021-22: 72 sites

It should be noted that the same indicator related to OAT sites and their results are reported by ISC under the Harm Reduction Pillar, as funding and activities support both Pillars' objectives. Moreover, ISC-supported OAT sites are funded through multiple funding sources in addition to the CDSS, including Budget 2018, provincial funding, and internal regional reallocations. Therefore, the impact of ISC-funded OAT sites cannot be entirely attributed to the CDSS. Indicators and funding for other treatment partners intersect and may support activities under other pillars.

Finally, from 2017 to 2022, Justice Canada's Youth Justice Fund supported numerous projects across the country for youth involved in the youth justice system and who have substance use issues, many of which supported Indigenous organizations and initiatives.

Recovery-oriented care

Several interviewees spoke about the need for more integrated and recovery-oriented care. For example, both internal and external interviewees noted a gap in the Strategy when it comes to recovery, highlighting that federal actions have been more focused on harm reduction than addressing the root causes of substance use. One interviewee noted that "people need to hear stories of hope that recovery is possible". Similarly, many interviewees agreed that there is a need for more integrated care, one that takes mental health and other social determinants of health, such as housing, into consideration. Interviewees also noted the positive linkage between harm reduction and wraparound services as a pathway to treatment and recovery, supporting a continuum of care.

Barriers impeding access to treatment

While activities and results show that progress has been made in making treatment and recovery services more accessible, interviewees and documents noted that regional disparities in the availability of services and supports bring challenges in providing equitable access to treatment services across Canada, especially for marginalized groups.

Recognizing that PTs are primarily responsible for the delivery of treatment services, many interviewees emphasized the need for more resources to address increasing treatment demands, and the need for more medical education focused on substance use and addiction treatment, including recruitment of addiction specialists and counsellors. Several other systemic barriers that create inequitable access to treatment were also identified in the literature and by interviewees, including stigma, location and distance of services, lack of culturally appropriate treatment, long wait times, cost of services. In addition, evidence from interviews and literature show that COVID-19 had significant negative impacts on substance use and access to health care during the pandemic, leading to a combination of increased use and reduced services. In response to treatment challenges brought forward by the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada has implemented a number of regulatory actions that have removed some barriers to accessing drugs for the treatment of opioid use disorders, such as authorizing pharmacists to prescribe controlled substances. Other regulatory actions will be discussed further in the following section on Harm Reduction.

Harm reduction

Key takeaways

The CDSS and Opioid Initiative have helped to expand the availability of harm reduction services, including supervised consumption sites and safer supply projects, through funding support and legislative and regulatory activities; however, evidence shows disparities in access to harm reduction services. There appears to be widespread awareness of the negative impacts of stigma on people who use drugs; nonetheless, substance use stigma persists, indicating the need for further education of the public, health care workers, and law enforcement.

Short-term outcome 4: Increase awareness of harm reduction principles and services for a wide variety of drugs and substances.

Some external interviewees spoke about how there is now widespread recognition of and support for harm reduction work in Canada. Many credit the federal government and the CDSS for driving the recent shift toward taking a public health approach to substance use, of which harm reduction is an important pillar. Population-based surveys appear to support this view. A series of public opinion research studies between 2017 and 2021 show a consistently high proportion of the Canadian public view the opioid overdose crisis as a public health issue, with around 3 quarters of survey respondents agreeing.

Naloxone, also called Narcan, is a medication and an evidence-based harm reduction measure that can help prevent death from opioid overdose. In 2021, nearly half (47%) of survey respondents were aware of what naloxone is and what it's used for and about a quarter (26%) knew where to get naloxone, although less than a fifth of respondents (18%) said they knew how to administer naloxone.Footnote 45

Finally, as previously discussed under the Prevention Pillar, Health Canada ran a multi-year digital advertising campaign to raise awareness of harm reduction measures, the negative consequences of substance use stigma, and the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act. These campaigns have reached millions of people in Canada.

Table 3: Key types of harm reduction measures

Safer Supply

This is a general service to prevent overdoses and death by providing people who use drugs with access to pharmaceutical-grade medications as a safer alternative to drugs obtained through the toxic illegal drug supply.Footnote 46 This also includes distribution of sterile drug use equipment to reduce the risk of transmitting bloodborne infections.Footnote 47

Take-Home Naloxone

Naloxone is a life-saving medication that can temporarily reverse the effects of opioid overdoses. Naloxone kits are available at many pharmacies without need for prescription and can be obtained from community-based organizations.Footnote 48

Drug Checking Services

These are services that test drugs and offer people who use drugs information on the composition of drugs in their possession.

Supervised Consumption Site (SCS)

This kind of site provides a safe space for people to bring their own drugs to use in the presence of trained staff to prevent accidental overdoses and reduce the spread of bloodborne infections.Footnote 49 SCSs operate under an exemption at the discretion of the Minister of Health in each province and territory.

Short-term outcome 5: Increase awareness of, and begin to reduce the negative impacts of stigma towards people who use drugs.

Stigmatization of people who use substances continues to be one of the greatest barriers for people to seek help and stay recovered.Footnote 50,Footnote 51Moreover, according to the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's 2019 Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, stigma is an important contributor to social and health inequities.Footnote 52 The evaluation found that federal campaigns and resources to address stigma have broad reach, and that awareness of substance use stigma is generally high. Nonetheless, stigmatizing attitudes persist in Canadian society.

Anti-Stigma Public Education Campaign

Since 2018-19, Health Canada has sought to end stigma against people who use opioids through a widespread and highly visible national advertising campaign. According to public reporting, the digital campaign received more than 167 million views, including incomplete views, between 2018-19 and 2021-22.Footnote 53,Footnote 54,Footnote 55,Footnote 56 In 2020, Health Canada launched the Stigma Gallery, a website that shares stories from people with lived and living experience of substance use, to address stigma around substance use. Reducing stigma was also a key theme in Health Canada's "Know More" substance use education tour for youth and young adults in Canada.

Additionally, Health Canada provided SUAP funding to non-profit organizations to develop and implement public education to address substance use stigma (see Table 4).

| Funding Recipient | Key Activities |

|---|---|

| Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addictions (CCSA) | Stigma Ends with Me Workshops and development of the "Overcoming Stigma through Language Primer". |

| Community Addictions Peer Support Association | Public education and community engagement activities and development of a national public engagement tool. |

| Moms Stop the Harm | In-person and online support workshops and support groups for families with relatives who have a substance use disorder. |

Recent survey evidence reveals that most people in Canada now recognize the negative impacts of substance use stigma. The evaluation following Health Canada's anti-stigma campaign in 2019 found that 57% of respondents believe that stigma creates a barrier to seeking treatment for substance use disorders.Footnote 57Similarly, Health Canada's 2021 public opinion research found that people were generally aware that stigma exists against people who use drugs and that it can limit people from seeking help, though these results were relatively unchanged compared to a previous survey from 2019.Footnote 58 Despite high levels of awareness of stigma, respondents to both the 2019 and 2021 surveys expressed conflicting personal beliefs, with many agreeing with stigmatizing misconceptions that blame substance use disorder on individual behaviour while also agreeing to statements expressing sympathy with people who use opioids. Focus group results revealed that people who held stigmatizing views often had difficulty recognizing that their views perpetuated stigma.Footnote 59

Interviews with representatives of regional and community-based organizations shared concerns about persistent stigmatizing beliefs among the Canadian public. A few people felt that stigma is particularly concentrated among groups that are already at a great disadvantage due to systemic discrimination. For instance,1 interviewee described how those dying from the overdose crisis are being "seen as disposable people and their lives are not valued," which impedes action to help more disadvantaged groups.

Resources and Training for Professional Groups

Substance use stigma can result in health, social, and justice policies and programs that discriminate against people with substance use disorders. This can lead to lower quality of support and care and further marginalization, such as through criminalization and refusal of employment.Footnote 60,Footnote 61,Footnote 62,Footnote 63

Under the CDSS and the Opioid Initiative, the federal government has made progress on addressing substance use stigma among government stakeholders, health care professionals, and law enforcement.

Under the Opioid Initiative, Public Safety Canada (PS) developed and launched a Drug Stigma Awareness Training for law enforcement personnel in Canada. PS collaborated with CCSA to promote this training and raise awareness of the impacts of stigma among law enforcement.Footnote 64However, there is limited information on the impact of these activities on reducing stigma in law enforcement personnel. Public data are available only from 2021-22, where PS reported that 7.9% of Canadian frontline police service members have completed the Drug Stigma Awareness Training. This is significantly less than the completion target of 25%. PS asserts this is largely due to law enforcement being preoccupied with pandemic-related priorities.

Since 2018, PS has hosted the Law Enforcement Roundtable on Drugs involving Canadian and international public safety partners across the country and with invited international guests. At the 2018 Roundtable, attendees and panelists acknowledged the negative impacts of stigma in the medical and law enforcement communities.Footnote 65 Roundtables in subsequent years included discussions of the need for local law enforcement to build relationships with community partners to connect people to health and social services and to ultimately reduce overdose harms, which was seen as an improvement in law enforcement attitudes.Footnote 66,Footnote 67

Although PHAC did not receive funding under the Addressing Stigma theme of the Opioid Initiative, the Agency worked with Health Canada to develop anti-stigma tools and resources for health professionals.Footnote 68 In 2020, PHAC published "A Primer to Reduce Substance Use Stigma in the Canadian Health System" which outlined the impacts of substance use stigma on quality of clinical care and on patient wellbeing. The primer then provided resources to help health care professionals advocate for and adopt non-stigmatizing practices.Footnote 69

Finally, there are examples of recent efforts within federal departments to address stigma in government publications and policies. In 2018, as part of the Drug Stigma Awareness Training, PS established a national law enforcement working group to advise the department on the development and deployment of a national awareness strategy and to identify ways to support de-stigmatization approaches.Footnote 70 As previously noted, progress on this was impeded by law enforcement's focus on supporting government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and, in some jurisdictions, natural disasters. Meanwhile, Health Canada has been updating their communications products to remove stigmatizing language. For example, while initial CDSS documents used terms such as 'problematic substance use' and 'illicit supply,' Health Canada staff now acknowledge these terms as stigmatizing and have removed and replaced the terms in newer publications and communications products relating to substance use.

Medium-term outcome 3: Increased uptake of community-based harm reduction programs and services across Canada.

Federal funding for community-based projects

Substance Use and Addictions Program

Much of the SUAP funding went to community and regional organizations running harm reduction-themed projects to address the opioid overdose crisis and other substance related harms. These projects have increased the availability of and access to important harm reduction services, including for those groups at greatest risk or who may face additional barriers to access.

Over half of all active SUAP projects focus on harm reduction. These include safer supply projects, drug checking services, overdose prevention and response training, distribution of naloxone kits, support for peer first responders and peer networks, and activities to reduce stigma in the health care system.Footnote 71,Footnote 72,Footnote 73,Footnote 74 Additionally, in fiscal year 2021-22, SUAP also funded a National Safer Supply Community of Practice, an initiative with the goal of facilitating "knowledge exchange, skill-sharing, and capacity building to scale up and support safer supply programs and prescribers across Canada."Footnote 75

Clients on the impact of Safer Supply

"Changed my life, otherwise I [would] still be in jail. Can access health system now. Have money to buy Xmas gifts. Health conditions improved. Gained weight, relationships are better. [Provider] saved my life."

"No [more] overdoses, I used to overdose almost every other day."

"…I feel I've genuinely found a way [to] actually be alive again…actually living and having a glimpse of a future. The money I save, the help I get, the fact that I've been able to stay clean from almost every other substance I used to struggle with… grateful I found [this program] when I did…"

Safer supply projects represent an important priority for SUAP, as the majority of CDSS-supported SUAP funding goes to these projects. As of April 2023, SUAP has supported 31 Safer Supply pilot projects across Canada, representing total funding of over $100.8 million since 2017. Currently, SUAP supports 29 Safer Supply pilot projects across Canada, representing a total funding commitment of over $96.4 million. According to the most recent internal program results report from 2021-22, 18 SUAP-funded Safer Supply projects serviced 2,540 clients and developed 938 knowledge and learning products. In 2022-23, SUAP funded an additional 11 new Safer Supply projects.

Evidence is being collected on the impact of SUAP projects in reducing harm. In 2019, CIHR directed CDSS funding to support 14 research teams through the "Evaluation of Interventions to Address the Opioid Crisis" funding opportunity. Their goal is to synthesize evidence of promising health interventions and practices to address the opioid crisis. Research related to the Harm Reduction Pillar focused primarily on the effectiveness of take-home naloxone programs. One research study identified "robust evidence that overdose education and naloxone distribution programs produce long-term knowledge improvement regarding opioid overdose, improve attitudes towards naloxone, provide sufficient training for participants to manage overdoses safely and effectively, and effectively reduce opioid-related mortality in community settings."Footnote 77 Two other studies confirmed the benefits of naloxone distribution programs to avert opioid overdose deaths, though one flagged challenges in accessibility for people in rural areas due to stigma, and the need for complementary services.

In 2020-21, Health Canada contracted a preliminary qualitative assessment of 10 SUAP-funded Safer Supply projects. This assessment found that program clients and staff reported improvements across a number of health and socioeconomic outcomes, such improved health, improved quality of life and stability, and accessing housing and employment.Footnote 78 Qualitative findings emphasized best practices like wraparound care, community and peer involvement, implementation of service processes, and ensuring inclusivity and accessibility. The main challenge appeared to be the limited effect of pharmaceutical alternatives to the highly potent fentanyl to which some participants have become tolerant. This means that the available dosages of safer alternatives may not be effective in managing withdrawal from fentanyl. Programs also cited logistical and capacity challenges due to the high demand for safer supply services relative to the limited availability of medications and staff.

Finally, in 2021, CIHR funded research grants for evaluations of the program implementation and short-term health impacts of SUAP-funded safer supply pilot projects, and 4 regional assessments of the public health impact of supervised consumption sites (SCSs) on clients and the public before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 79 The 2021-22 Supervised Consumption Sites (SCSs) Evaluation's End-of-Grant Virtual Workshop took place in October 2022. The 4 regional projects funded through this initiative evaluated several facets of the dual crises (COVID-19 and the national overdose crisis), including usage and uptake patterns, barriers to access, flexible formats, holistic and integrated care, advocacy, and resourcing. At the end-of-grant workshop, research findings were shared alongside the perspectives and expertise of knowledge users, which provided a comprehensive view of the topic and enhancing the potential impact of the findings. Knowledge shared through this event can be used to support evidence-based decisions to help ensure safe and consistent delivery of SCSs in both regular and adverse public health environments.

Harm Reduction Fund

PHAC has helped expand and increase uptake of services through its Harm Reduction Fund (HRF) G&Cs program. The HRF supports community-based efforts to reduce sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) like hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among people who use and share inhalation or injection equipment to use drugs.

As of 2019-20, HRF projects have provided harm reduction services to over 35,000 people. An initial assessment of the HRF found that 80% of targets set out in project objectives were being met, nearly met or had been exceeded.Footnote 80 These projects were reviewed by a diverse committee of PWLLE including representatives from LGBTQ2+ and Indigenous communities, health professionals, and peer educators.

Legislative and regulatory activities

From October 2017 to end of March 2022, there have been over 3.5 million visits to SCSs in Canada, with over 256,000 unique clients.Footnote 81 Most SCS clientele are male and a third are in the 30-39 age group. Surveillance data has found these are the demographics most likely to use opioids and experience opioid use harms.Footnote 82 Sites reported reversing over 39,000 overdoses and making over 117,000 referrals to health and social services, including mental health support, medical care, and housing. As a result, SCSs have reduced overdose harms and saved thousands of lives in Canada.

In 2017-18, following the launch of the CDSS, Health Canada streamlined applications for exemptions under the CDSA to allow SCSs to operate. These legislative changes have led to a significant increase in availability of SCS services, particularly for populations that need them most. Following this change, the number of SCSs in Canada increased from only 1 in late 2015 to 38 sites offering services as of April 2023. While only 56% of applications for an exemption to operate a SCS received a decision within service standards in 2017-18, this result increased to 91% for the following 2 years, surpassing targets.

Furthermore, SCSs have been established in areas where there are high rates of public drug use to provide important health, social, and treatment services. Health Canada has authorized the operation of various types of SCS to improve reach to different populations, such as stand-alone services, mobile units, and sites co-located in community health centres, inpatient or outpatient hospital settings, homeless shelters, and supportive housing settings.

In addition, in response to the rise in overdose harm and deaths in Canada at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada issued 63 exemptions or exemption extensions under the CDSA.Footnote 83 These exemptions gave PTs greater flexibility in implementing harm reduction activities in response to urgent local needs, such as establishing an Urgent Public Health Need Site (also known as an overdose prevention site) more quickly and in temporary spaces, including shelters.Footnote 84 Furthermore, Health Canada helped ensure access to prescribed controlled substances during stay-at-home orders through an additional exemption under the CDSA that allowed health practitioners to verbally prescribe controlled substances and authorized pharmacists to prescribe, sell, and provide controlled substances in limited circumstances.Footnote 85

While many interviewees supported the increased uptake of harm reduction programming throughout Canada in the past few years, many suggested opportunities for improvement. Several interviewees, mostly CDSS federal partners, called for more evidence to be gathered for federally funded harm reduction interventions in order to better understand what works best and share best practices nationally. However, Health Canada and CIHR are already in the process of collecting and assessing information on the impact of these programs and services.

Specifically, CIHR's SCS Evaluation (2021-22) End-of-Grant Virtual Workshop took place on October 28, 2022. The 4 regional projects funded through this initiative evaluated several facets of the dual crises (COVID-19 and national overdose crisis), including usage and uptake patterns, barriers to access, flexible formats, holistic and integrated care, advocacy, and resourcing. In the end-of-grant workshop, research findings were shared alongside the perspectives and expertise of knowledge users, providing a comprehensive view of the topic and enhancing the potential impact of the findings.Footnote 86

Meanwhile, several internal and external interviewees criticized the piecemeal or incremental approach of pilot projects and felt they were insufficient to reduce harm. These interviewees wanted current interventions, including decriminalization, safer supply, and safe consumption sites, to go further or be expanded considering the urgency of the current opioid overdose crisis in Canada.

Medium-term outcome 4: Stigma is reduced and people who use drugs are increasingly accessing and are supported with appropriate health and social services.

National surveys have found that people in Canada continue to hold stigmatizing beliefs around substance use and substance use disorders (see Short-term Outcome 5). Research and survey evidence show that stigma in the Canadian health care system continues to affect access to services for people who use substances. This was also described by several interviewees, including members of organizations representing people with lived and living experience of substance use. These representatives called for more training for health care providers, including pharmacists, in addressing stigma in the health care system.