Archived - Evaluation of the eHealth Infostructure Program 2011-2012 to 2015-2016

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1,098 K, 94 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: 2017-07-??

Prepared by Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

March 2017

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1.0 Evaluation Purpose

- 2.0 Program Description

- 3.0 Evaluation Description

- 4.0 Findings

- 4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 – Continued Need for the Program

- 4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 – Alignment with Government Priorities

- 4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 – Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 4.4 Performance: Issue #4 – Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

- 4.5 Performance: Issue #5 – Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

- 5. Conclusions

- 6.0 Recommendations

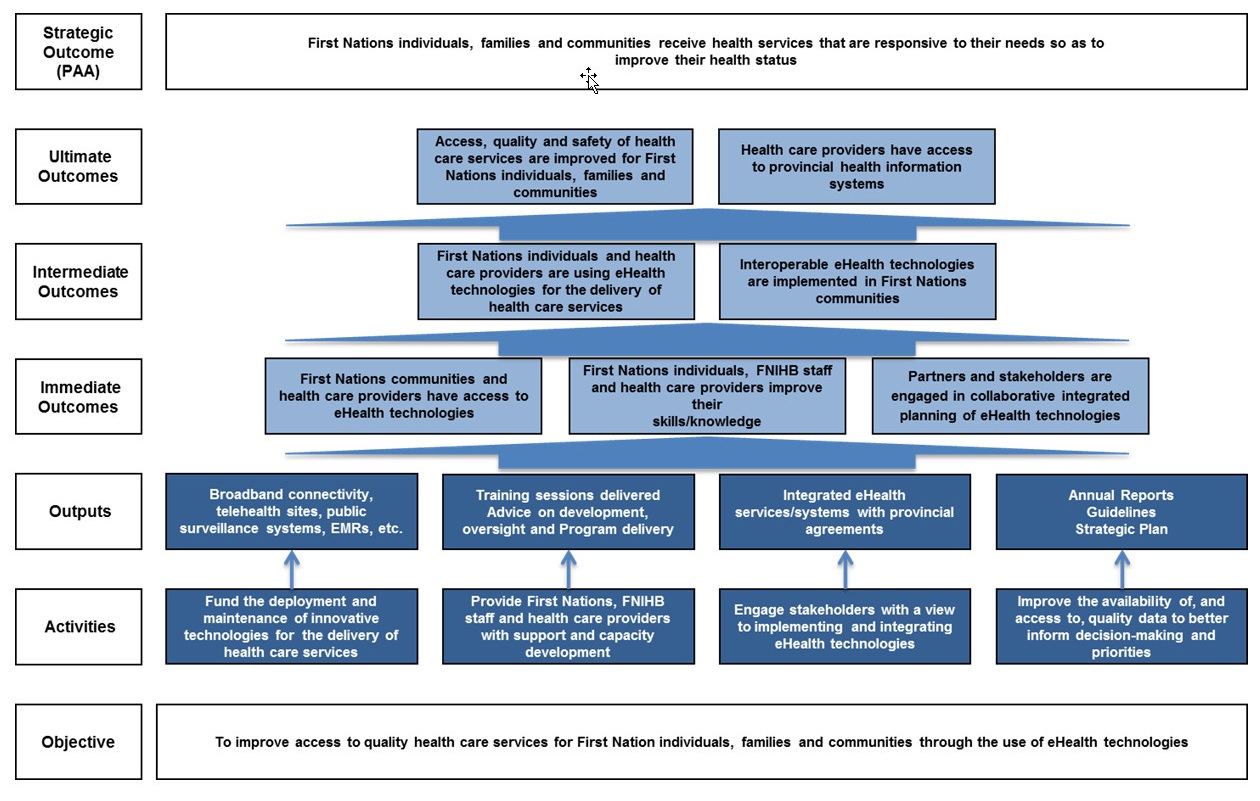

- Appendix 1 – Logic Model: eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP)

- Appendix 2 – Summary of Findings

- Appendix 3 – Evaluation Description

List of Tables

- Table 1. Limitations and mitigation strategies.

- Table 2. Broadband availability among First Nations Bands funded by the eHealth Infostructure Program for Internet connectivity as of March 2016.

- Table 3. Broadband availability amongst First Nations Bands funded by the eHealth Infostructure Program for Internet connectivity with nursing stations as of March 2016.202

- Table 4. Number of First Nations communities with Panorama Public Health Information System.

- Table 5. Number of First Nations communities with a non-Panorama Public Health Information System.

- Table 6. Number of First Nations communities with eHealth Infostructure Program-funded nursing stations with Panorama Public Health Information System.

- Table 7. Number of First Nations communities with eHealth Infostructure Program-funded nursing stations with a non-Panorama Public Health Information System.

- Table 8. Number of First Nations communities with access to Electronic Medical Records.

- Table 9. Number of First Nations communities with access to a provincial Electronic Health Records.

- Table 10. Number of First Nations communities with eHealth Infostructure Program-funded nursing stations with access to Electronic Medical Records.

- Table 11. Number of First Nations communities with eHealth Infostructure Program-funded nursing stations with access to a provincial Electronic Health Records.

- Table 12. Number of telehealth sites funded by the eHealth Infostructure Program in First Nations communities.

- Table 13. Number of telehealth sites funded by the eHealth Infostructure Program in First Nations communities with nursing stations.

- Table 14. Number of telehealth educational sessions.

- Table 15. Number of telehealth administrative sessions.

- Table 16. Number of telehealth clinical sessions.

- Table 17. Annual eHealth Infostructure Program budgets by fiscal year ($).

- Table 18. Annual eHealth Infostructure Program expenditures (actuals) by region by fiscal year ($).

- Table 19. Annual eHealth Infostructure Program expenditures (actuals) by financial code by fiscal year ($).

- Table 20. Cost avoidance of as a result of telehealth clinical sessions – Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario, 2015-2016.

- Table 21. Cost avoidance of medically necessary travel a result of telehealth clinical sessions – Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario, 2015-2016.

List of Figures

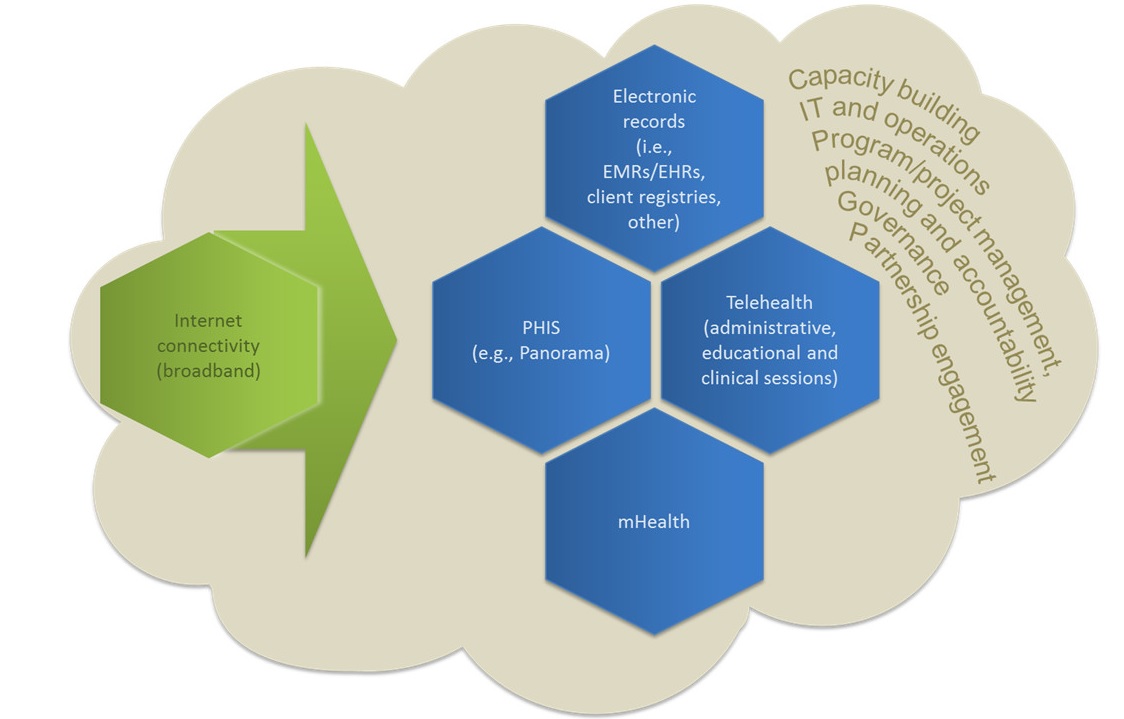

- Figure 1: eHealth components and elements.

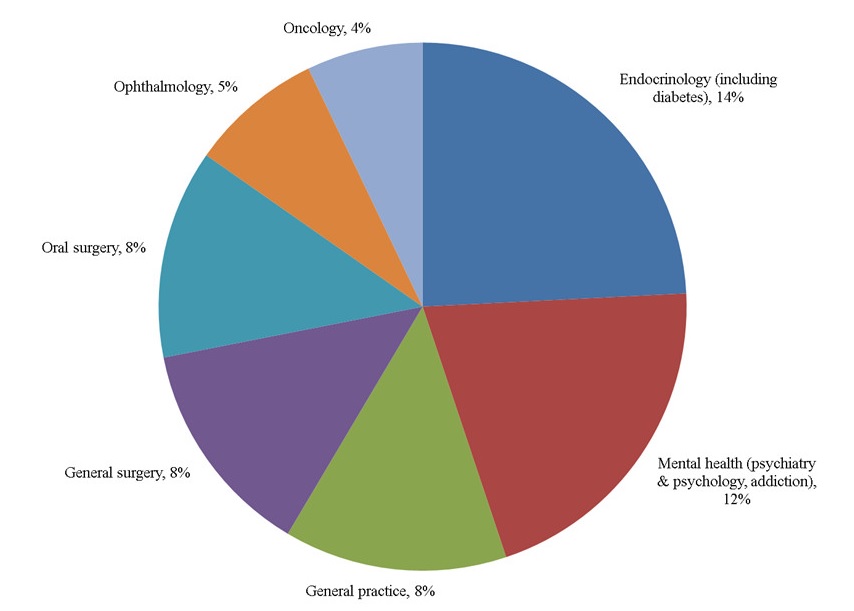

- Figure 2: Top types of telehealth clinical sessions as reported by Keewaytinook Okimakanak eHealth Telemedicine Services for 2015-2016.

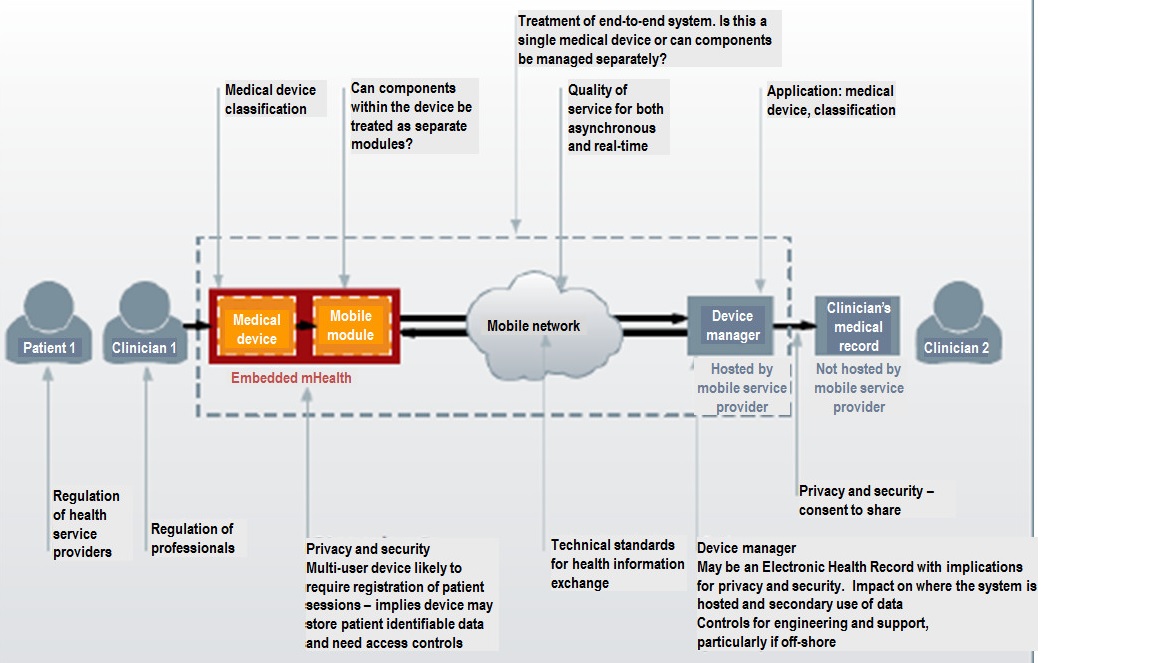

- Figure 3: Policy and regulation that could apply to remote monitoring solutions.

List of Acronyms

- AB

- Alberta

- ACES

- Alaska Clinical Engineering Services

- ACRRM

- Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine

- ADMO

- Assistant Deputy Minister's Office

- AeHN

- Alaska eHealth Network

- AFHCAN

- Alaska Federal Health Care Access Network

- AFN

- Assembly of First Nations

- ANTHC

- Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium

- BC

- British Columbia

- cEMR

- Community EMR

- CFOB

- Chief Financial Officer Branch – Health Canada

- CHIP

- Community Health and Immunization Program

- CSB

- Corporate Services Branch – Health Canada

- eHIP

- eHealth Infostructure Program

- EHR

- Electronic Health Record

- EMR

- Electronic Medical Record

- F/P/T

- Federal/Provincial/Territorial

- FNEC

- First Nations Education Council

- FNHSSM

- Nanaandawewigamig – First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba

- FNIHB

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch – Health Canada

- FNQLHSSC

- First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission

- HCOM

- Health Co-Management

- HFCP

- Health Facilities and Capital Program

- HIE

- Health Information Exchange

- HISAP

- Health Infostructure Strategic Action Plan

- HQ

- Headquarters

- ICTs

- Information and Communications Technologies

- IMSD

- Information Management Services Directorate – Corporate Services Branch

- INAC

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- Infoway

- Canada Health Infoway

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- ISP

- Internet Service Provider

- IT

- Information Technology

- ITK

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- KOeTS

- Keewaytinook Okimakanak eHealth Telemedicine Services

- KRG

- Kativik Regional Government

- LAN

- Local Area Network

- MATC

- Manitoba Adolescent Treatment Centre

- MB

- Manitoba

- mHealth

- Mobile Health

- MOP

- Management Operational Plan

- NB

- New Brunswick

- NIHB

- Non-Insured Health Benefits

- NITHA

- Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority

- NL

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- NLCHI

- Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Health Information

- NS

- Nova Scotia

- OCAP

- Ownership, Control, Access and Possession

- OHIP

- Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- ON

- Ontario

- OTN

- Ontario Telemedicine Network

- PCEHR

- Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record

- PDA

- Personal Digital Assistants

- PEI

- Prince Edward Island

- PHIS

- Public Health Information System

- QC

- Québec

- SK

- Saskatchewan

- SSC

- Shared Services Canada

- SUS

- Unified Health System

- TSAG

- Technical Services Advisory Group

Executive Summary

This evaluation covered the activities of Health Canada's eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP) for the period from 2011-2012 to 2015-2016. The evaluation was required by Section 42.1 (1) of the Financial Administration Act (1985), according to which every department shall conduct a review, every five years, of the relevance and effectiveness of each ongoing program for which it is responsible. The Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) defines such a review as an evaluation.

Based on the evaluation findings, the Program continues to address a fundamental, demonstrable need and is well aligned with government priorities as well as federal roles and responsibilities. The Program has made considerable contributions to increase access to primary care delivery by First Nations communities and has exceeded many of its targets in the deployment of eHealth infostructure technologies and tools. It has enabled First Nations and health care providers to improve their skills and has partnered at multijurisdictional levels to effect the integration of health services. There remain many opportunities for improvement (e.g., in broadband connectivity, IT support, health facility readiness for eHealth technologies, local capacity and awareness, interoperable systems, telehealth utilization, and deployment of mobile health). Recommendations provided by the evaluation are geared towards supporting the Program in its continuing work in these areas.

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The scope of the evaluation covered the period from April 1st, 2011 to March 31st, 2016 and included all the elements and eHealth components of the Program. The one area of exclusion was the assessment of any services transferred to the British Columbia First Nations Health Authority on July 2013 in accordance with the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance and sub-agreements, which will be covered under a separate and forthcoming evaluation.

The evaluation was aligned with the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) and considered core issues under the themes of relevance and performance. Corresponding to each of the core issues, specific questions were developed based on Program considerations and these guided the evaluation process. An outcome-based, non-experimental evaluation approach was used for the conduct of the evaluation to assess the progress made towards the achievement of the expected outcomes, whether there were any unintended consequences and what lessons were learnt.

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, which included a document and literature review, an administrative data review and analysis, key informant interviews, case studies, a review and analysis of eHealth approaches across international jurisdictions, and an examination of available financial data for the Program. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered through these different methods. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended as a way to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

Program Description

eHIP, under the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), works towards the modernization, transformation, improvement and sustainment of health care services in First Nations communities.Footnote i It supports and funds a combination of eHealth information, applications, technology and people to help provide First Nations with: optimal health services delivery; optimal health surveillance; effective health reporting, planning and decision making; and, integration/compatibility with other health services delivery systems. To carry out its mandate, eHIP functions in an environment that includes other federal partners, provinces, First Nations communities and regional organizations to achieve progress on the various dimensions of eHealth.

The implementation of eHIP is a shared responsibility between the national Program headquarters in Ottawa and six regional offices: the Atlantic region (including the provinces of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick), Québec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Conclusions - Relevance

Continued Need for the Program

The Program continues to address a demonstrable, fundamental need to improve the health status of First Nations. Specifically, the Program provides eHealth services to First Nations communities, reduces travel time and costs as well as displacement from family and community. By connecting patients with specialists for diagnostic examinations and follow ups, eHIP helps to narrow the gap in access to health care services for First Nations compared to the general population in the provinces. eHealth also allows for better continuity of care by facilitating information sharing between health care providers on- and off-reserve in support of better care assessment and decision making.

Alignment with Government Priorities

The Program is aligned with government priorities, which include keeping pace with technology and innovation, contributing to address health system challenges and system reform, and building relationships with Indigenous peoples. eHIP's objectives align with Health Canada's priorities and includes FNIHB's strategic objectives, namely, ensuring availability of, and access to, quality health services, supporting greater control of the health system by First Nations and Inuit, and supporting the improvement of First Nations health programs and services through improved integration, harmonization and alignment with federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) health systems.

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The Program is aligned with federal roles and responsibilities. While Health Canada has overall responsibility for the development and implementation of eHIP and ensuring that funding is appropriately allocated and spent according to established criteria and guidelines, FNIHB's role is to integrate F/P health systems for the benefit of First Nations, and to increase First Nations community health services capacity to address their own health needs.

Conclusions – Performance

Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

Immediate outcomes

The evaluation found that First Nations communities and health care providers have access to eHealth technologies. For example, the Program has exceeded its target for broadband connectivity; however, while all eHIP funded First Nations Bands have Internet connectivity, the available bandwidth and connection reliability is variable. The Program has also exceeded its targets on Public Health Information Systems (PHIS) and Electronic Medical Record (EMR)/Electronic Health Record (EHR) implementation. Telehealth continues to grow but its uptake/utilization has been uneven across remote/isolated and isolated communities. Mobile Health (mHealth) appears promising and is in its developmental phase.

eHIP has enabled First Nations, FNIHB staff and health care providers to improve their skills and knowledge by providing opportunities through telehealth education and administrative sessions in various formats. Telehealth educational sessions offered to First Nations individuals and health care providers have allowed them to acquire information and knowledge on a number of health-related areas such as, diabetes education, drug awareness, population health, community health planning, health indicator development and measurement, public health surveillance, health information management, and training on new health equipment. Available information indicates the usefulness and efficiency of telehealth educational sessions among frontline health care workers, staff and communities.

The Program has engaged partners and stakeholders in collaborative, integrated planning of eHealth technologies by using a number of mechanisms for multi-party engagement. In terms of harmonization, eHIP is working with First Nations and F/P representatives in effecting the integration of health services by identifying opportunities and actively engaging in multi-jurisdictional partnerships.

Intermediate outcomes

First Nations and health care providers are using eHealth technologies for the delivery of health care services. Clinical telehealth sessions are delivered in many First Nations communities covering numerous topics. The Program has exceeded its target of providing clinical sessions via telehealth to First Nations communities. These sessions have covered a multitude of clinical specialties.

Opportunities exist for greater collaboration and integration with First Nations regional organizations, the federal family (i.e., Health Canada, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada – INAC, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada – (ISED)) as well as within Health Canada that could result in increased and more stable Internet connectivity and bandwidth thus further enabling clinical telehealth in remote/isolated and isolated First Nations communities. There is also an opportunity for addressing IT-related issues through a client-focused support approach that clearly defines the roles and responsibilities of all partners (i.e., eHIP, the Information Management Services Directorate – (IMSD) of Health Canada's Corporate Services Branch (CSB), and Shared Services Canada – (SSC)). This would support eHealth integration into primary and public health care delivery in First Nations communities.

Furthermore, developing standards and guidelines on network and connectivity/bandwidth requirements linked to each eHealth component would be advantageous as it would be the integrated planning and refurbishing of health facilities to accommodate eHealth and its components

Uptake of telehealth in some remote/isolated and isolated communities could be increased through promotion among First Nations individuals, families and communities as well as health care practitioners in addition to providing enhanced support on the ground (e.g., telehealth coordinators). Further support for mHealth by helping communities address challenges related to connectivity and communications security may aid technology adoption.

Interoperable eHealth technologies have been implemented in First Nations communities. PHIS and electronic records implementation have exceeded targets. Nonetheless, interoperable PHIS and electronic records are at different stages of implementation across provinces and First Nations communities. Despite progress, there is a need to resolve several legislative, jurisdictional and logistical issues that impede uptake in this area, none of which are in the sole purview of the Program. For example: lack of alignment between F/P privacy legislations affecting federal and First Nations nurses' access to patient information on provincial systems, adequate connectivity/bandwidth, proliferation of non-interoperable electronic records systems, clarification of responsibility for physician remuneration as a result of eHealth delivery, and provision of appropriate/ongoing funding.

Although an approach to EMR implementation has been developed by eHIP, interoperability with provincial systems remains a key challenge and largely outside the control of the Program. There is a need for greater collaboration to improve engagement and alignment between F/P governments and First Nations communities. A focus on the alignment of F/P privacy legislation together with the development of a common ground to spur collaboration between all parties would help overcome the barriers.

Strong partnerships with knowledgeable organizations around the principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAP), such as Canada Health Infoway (Infoway), may help to increase awareness and willingness to integrate health data among many remote/isolated and isolated First Nations communities; generally, these communities do not benefit from the leadership provided by strong First Nations regional organizations (e.g., communities in Southern Saskatchewan, those outside Keewaytinook Okimakanak eHealth Telemedicine Services – KOeTS in Ontario, and many in Atlantic Canada).

With respect to opportunities to increase the implementation efficiency of interoperable eHealth technologies, it would be desirable to arrive at commonly agreed F/P goals to assist First Nations in selecting solutions that address their needs while ensuring interoperability with provincial systems. In addition, a systematic, coordinated community assessment process to identify eHealth component readiness, community technical capacity (e.g., human resources), available/needed training and infrastructure would increase implementation success.

Long-term outcomes

Access to and quality of health care services has improved for First Nations individuals, families and communities over the past five years. Across the regions, eHealth components are being made available to federal and First Nations health care providers to enable the provision of timely access to health care services while allowing providers to engage with patients and improve the quality of care. Clinical telehealth is contributing towards improving access and enhancing the number of available health services in First Nations communities. Telehealth educational sessions are viewed as valuable for health care provider training and in health promotion and disease prevention in First Nations communities. While there are many examples to support increased access, quality and safety, there are opportunities to implement systematic surveying, analysis and reporting of user experience with the various eHealth components to allow for routine assessment of levels of satisfaction and identification of areas for improvement.

Planning, surveillance and reporting of health data in First Nations communities have also been enhanced as a result of eHealth, although there are further opportunities for improvement across communities, specifically in terms of the availability of qualified, dedicated personnel for data collection and regular analysis based on a core set of common indicators within and across regions.

Health care providers have access to and use provincial health information systems in First Nations communities. Where implemented, users see these systems as helpful in planning and in managing the health care of First Nations individuals, families and communities. For example, where deployed, nurses see immunization and vaccine inventory modules as enabling them to provide improved patient care. PHIS and electronic records are allowing for better case management, improved patient safety and informed decision-making by health care providers.

Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

There is evidence to indicate that the Program's utilization of resources in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes is efficient and economical. Program goals are actively communicated while alignment between projects, eHealth components and regional needs and priorities are ensured.

Efficiency

Despite efforts to remain aligned, due to the rapidly changing eHealth context, it is challenging for eHIP to track regional status and overall national situation; hence, there is a need to conduct community and technology environmental scans on an ongoing basis to inform Program guidelines. Also, when decisions are made with respect to bandwidth or solutions for interoperability of systems between First Nations and provinces, regional and sub-regional contextual factors should be examined in order to attain a better fit for the communities. In this context, there may be a need to re-examine the Health Infostructure Strategic Action Plan (HISAP) to ensure it reflects a grassroots approach.

Currently, regions employ a variety of project plans and readiness assessment templates. While, in principle, a thorough assessment is being made through the use of ad hoc criteria, check lists and committees, opportunities exist for a more cohesive, planned approach to project assessment that would assist in greater efficiencies and economies of scale.

Economy

Program expenditures over the five years of the evaluation ranged between $22 and $25 million annually, with the exception being 2012-2013 when the highest expenditure of $30 million was incurred. Cost avoidance for the Program as a result of all telehealth clinical sessions delivered in four regions (for which data was available) in 2015-2016 was estimated at approximately $11.7 million. Cost avoidance as a result of those telehealth clinical sessions that would have been considered medically necessary by the Supplementary Health Benefits (Non-Insured Health Benefits) Program delivered in the same regions and during the same fiscal year was estimated at approximately $6.5 million.

Evidence suggests the need for a three- to five-year funding horizon to realize efficiencies from a longer-term implementation of the various technology-based eHealth components. Current year-to-year funding management may be creating efficiency gaps as a result of piecemeal, short term implementation (e.g., equipment purchased but not used). The longer-term plan should be based on a robust analysis of which communities would be supported first for basic needs like Internet connectivity and capacity training, and how the progression will be made with respect to eHIP component growth (e.g., electronic records, PHIS, telehealth and mHealth). The plan would also have room for funding innovation and for evergreening equipment.

Another aspect of planning and funding would involve engaging partners at multilateral tables to identify parallel funding sources (e.g., from other federal departments or provincial support). Examples include involvement of Infoway in some First Nations eHIP component implementation, use of the Health Services Integration Fund (HSIF), partnering with INAC to share connectivity with schools or fibre build, etc. This approach could be expanded to support innovation. There is also a need to develop a plan on how to address those communities that do not have a strong champion or regional leadership (such as the Technical Services Advisory Group – (TSAG), the Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority – ( NITHA), the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba – (FNHSSM), the First Nations of Québec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission – (FNQLHSSC), Atlantic Canada's First Nation Help Desk, and KOeTS) and may be falling behind on eHealth.

Performance measurement

Data collection and reporting has improved during the period of the evaluation, particularly in the last three years. Opportunities exist for consistent and timely data collection and reporting across all regions, communities and health facilities. Applying clear data definitions and focusing on Program-funded communities would help data quality.

There are many advantages to be realized by systematically collecting and analyzing performance data at timely intervals. It is understood that some communities, First Nations regional organizations and even regional Program offices may lack on the ground capacity to perform these activities. One of the key considerations in setting up a performance measurement system is to look at the feasibility of the required data given the capacity on the ground. The evaluation has suggested a number of indicators, some of which are already being used by the Program, around which data collection and analysis could be enhanced to lend support for future Program decisions, including funding needs.

Recommendations

The incremental work of the Program in the various eHealth areas has contributed to the achievement of its outcomes. While the Program has met or exceeded most of its key targets, the following recommendations identify areas where continuing work will help the Program further its work with a long term view towards deploying, maintaining and realizing the benefits of digital infrastructure for First Nations individuals, families and communities.

Recommendation 1. Enhance partnership, collaboration and integration with partners and stakeholders to continue to improve Internet connectivity to provide equitable access to underserved First Nations communities.

Broadband connectivity

Applying a coordinated and community-focused effort with Program partners and stakeholders, such as First Nations regional organizations, INAC, ISED, provincial governments and private industry, would allow eHIP to derive benefits from existing/planned activities, foster standardization in enabling appropriate bandwidth for eHealth components, and identify First Nations communities' broadband needs and available funding from various sources to address Internet connectivity challenges.

eHealth component requirements

Identifying and defining broadband requirements for eHealth components would allow the Program to ascertain service gaps. These requirements should be based on standardized technical guidelines for each eHealth component (e.g., electronic records, PHIS, telehealth) in alignment with provincial standards, if any. Assessing health facility readiness for eHealth based on these and other infrastructure requirements (e.g., plug-ins for telehealth equipment in emergency rooms, room acoustics/privacy considerations, Local Area Network and related equipment condition, etc.) would allow the Program to identify any needed enhancements.

Recommendation 2. Advance work with partners, to address IT- and health facility-related issues to enable health care practitioners (nurses) to integrate eHealth tools into primary and public health care delivery.

Roles and responsibilities for IT support and health facility infrastructure

Clarifying the roles and responsibilities of partners within and outside Health Canada (e.g., First Nations regional organizations, eHIP, the Health Facilities and Capital Program, IMSD, SSC), and establishing client-focused mechanisms to ensure that IT issues experienced by health care workers (e.g., nurses) are addressed in a timely manner, would help further eHealth adoption and integration into primary and public health care delivery. The current efforts between FNIHB and IMSD on improving IT support for FNIHB employees in remote/isolated and isolated communities should continue in order to address roles and responsibilities and, potentially, health facility infrastructure issues. In addition, the gap in IT infrastructure and support for transferred First Nation health facilities should be assessed periodically for sustained use of eHealth applications.

Recommendation 3. Work closely with provincial governments, federal partners (e.g., Infoway), First Nations regional organizations and communities to further integrate approaches to render electronic records and PHIS interoperable, effective and efficient by removing jurisdictional, legislative and logistical hurdles.

F/P privacy legislations

Collaboration among F/P partners should focus on identifying information sharing solutions to address issues surrounding federal and First Nations nurses and their access to patient data on provincially connected PHIS and electronic records. This is an area of high priority requiring resolution across most provinces.

Data sharing agreements

Successful implementation of data sharing agreements requires extensive engagement with First Nations, provincial and federal partners to address challenges with interoperable systems. Further engagement would help advance work on alignment with provincial systems and privacy issues as well as widespread integration of OCAP principles in data sharing agreements to ensure health data can be exchanged in a way that meets the needs of all parties. Resolving data privacy/sharing issues would not only contribute to the provision of seamless care on- and off-reserve but also to address issues related to health care practitioner billing.

F/P vision alignment

Defining a coordinated vision and partnership on eHealth systems with First Nations communities and provincial governments would help achieve commonly agreed goals for new technologies based on a common ground. This, in turn, would help establish realistic timelines for eHealth component implementation that would make optimal use of limited resources while ensuring implementation satisfaction.

Recommendation 4. Continue to engage First Nations communities to enhance knowledge, capacity and control over their health care service delivery and use of health data for evidence-based decision making.

Promotion

eHealth capacity and adoption would benefit from promoting best practices and success stories in the implementation of the various eHealth components (i.e., electronic records, PHIS, telehealth and mHealth). Further benefits would be accrued by sharing the positive results of partnerships with First Nations regional organizations such as FNHSSM, the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission, NITHA, TSAG, KOeTS and Atlantic Canada's First Nation Help Desk. First Nations communities with low awareness of eHIP or that lack a strong regional champion/leader may require support/encouragement to pool together and work with a First Nations regional organization to lead eHealth on their behalf.

Readiness assessments

In partnership with First Nations regional organizations and communities, developing and applying a systematic, coordinated, cohesive community assessment process to identify eHealth component readiness and community technical capacity (e.g., IT workers, data infrastructure staff, nursing staff, telehealth coordinators, data specialists) would help in identifying the required training and infrastructure to build capacity and successfully implement and maintain eHealth components.

Capacity development

Increasing the ground level capacity of health care practitioners and health facility staff on the use of eHealth tools may enhance primary and public health care delivery (e.g., continue to train nurses in the use of telehealth equipment). Moreover, continuing to grow the number of eHealth/telehealth coordinators would contribute to support and promote telehealth and other eHealth components (e.g., electronic records, PHIS and mHealth).

Collaborative strategy

Conducting regular community and technology environmental scans, within regional and sub-regional contexts, would help inform Program guidelines affecting all eHealth components. Reassessing HISAP in collaboration with First Nations communities and regional organizations would make it the product of a balanced, bottom-up (grassroots) and top-down process.

Recommendation 5. Improve performance data collection and analysis across regions and over time on key performance indicators by setting up a Program performance measurement system that takes into consideration the capacity on the ground.

Identifying key indicators, such as those reported by the evaluation, and establishing consistent definitions across regions and data collection entities would help improve data collection. Ensuring clarity of definitions and establishing a data reporting cycle would help accurate and regular analysis to inform timely decision-making.

Recommendation 6. Develop a long-term plan that is sufficiently flexible to accommodate technology innovation and a commensurate funding strategy for e-HIP.

Providing a long-term plan and funding view, in concert with technology-based projects, that fully supports all aspects of implementation and sustainability, including capacity, training and bandwidth, would contribute to the long-term vision of the Program. Part of this exercise should include identifying which communities would be supported first for basic needs like Internet connectivity and capacity training, and how the progression will be made with respect to eHIP component growth (e.g., electronic records, PHIS, telehealth, mHealth).

Incorporating innovation allocations would allow the plan to grow together with technology advancements, such as wireless connectivity, bandwidth and data security; technology development in mHealth and personal telehealth (e.g., via laptops and iPads); storage and streaming technologies for educational sessions; and, evergreening of equipment.

Management Response and Action Plan (or Management Response)

| Recommendations | Response | Action Plan | Deliverables | Expected Completion Date | Accountability | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation as stated in the evaluation report | Identify whether program management agrees, agrees with conditions, or disagrees with the recommendation, and why | Identify what action(s) program management will take to address the recommendation | Identify key deliverables | Identify timeline for implementation of each deliverable | Identify Senior Management and Executive (DG and ADM level) accountable for the implementation of each deliverable | Describe the human and/or financial resources required to complete recommendation, including the source of resources (additional vs. existing budget) |

Recommendation 1 Enhance partnership, collaboration and integration with partners and stakeholders to continue to improve Internet connectivity to provide equitable access to underserved First Nations communities. |

Management agrees with the recommendation. | The eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP) works together with its partners and stakeholders to improve broadband connectivity for First Nations communities. | 1.1 Site profiles for all in-scope facilities. | 1.1 September 2017 | Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB | Existing budget |

|

In recognition of the importance of partnership, FNIHB has started the Connectivity for First Nation Health Facilities project to provide a clear understanding of connectivity needs for on-reserve health facilities in 6 regions (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta). The project links key partners, eHIP national office, eHIP regions, Internal Client Services and Transition Directorate, FNIHB, Health Facilities Program, FNIHB, Information Management and Systems Directorate, Corporate Services Branch (CSB), Real Property and Security Directorate, CSB, and Shared Services Canada. The project will identify current state connectivity by:

|

1.2 Connectivity Gaps Analysis Report. | 1.2 November 2017 | ||||

|

Recommendation 2 Advance work with partners, to address IT- and health facility-related issues to enable health care practitioners (nurses) to integrate eHealth tools into primary care delivery. |

Management agrees with the recommendation |

eHIP works with partners across Health Canada and Shared Services Canada toward greater collaboration with a view to improved delivery of primary care through the use of eHealth tools. Specifically, the program participates actively in the IT Support for FNIHB Nurses Working Group, led jointly by Information Management and Services Directorate, CSB, and Internal Client Services and Transition Directorate, FNIHB in support of incrementally addressing IT infrastructure and support for nurses working in remote and isolated locations where primary care services are provided by FNIHB employees. |

2.1 Development of model that will provide simpler service desk support to nurses. | 2.1 March 2018 |

Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB Executive Director, ICST, FNIHB |

Existing budget |

|

Recommendation 3 Work closely with provincial governments, federal partners, (e.g., Infoway), First Nations regional organizations and communities to further integrate approaches to render electronic records and Public Health Information Systems interoperable, effective and efficient by removing jurisdictional, legislative and logistical hurdles. |

Management agrees with the recommendation | FNIHB has undertaken a region-by-region approach with provincial government partners, as appropriate, to identify information sharing solutions appropriate for the provincial context. Joint work on the development of action plans is in its early stages, and FNIHB will work together with provincial governments where there are willing partners. Resolving the information-sharing issues will translate to greater uptake of electronic medical records and public-health information systems. | 3.1 Joint action plans with provincial partners to address privacy issues. | 3.1 March 2019 |

Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB Regional Executives, FNIHB |

Existing budget |

| eHIP regions are working with First Nations partners such as the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and regional First Nations organizations to identify community-driven priorities and approaches , and with other partners, including Canada Health Infoway, in support of these priorities and approaches. | 3.2 Rollup of regional priorities regarding implementation of digital health technologies. | 3.2 March 2018 | ||||

|

Recommendation 4 Continue to engage First Nations communities to enhance knowledge, capacity and control over their health care service delivery and use of health data for evidence-based decision making. |

Management agrees with the recommendation |

FNIHB work with its national and regional First Nations partners to build capacity to support eHIP expansion in First Nations communities. As part of these efforts, eHIP will engage the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and First Nations regional partners on expanding the existing readiness assessment tool used for eHealth project management. |

4.1 Revised readiness assessment tool, expanded in collaboration with AFN and regional First Nations organizations. | 4.1 September 2017 | Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB | Existing budget |

|

The eHIP program already disseminates information about its work with the assistance of FNIHB regions and eHIP partners such as Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and the Assembly of First Nations, and regional First Nations partners. The current approach for dissemination services across all the regions does not always leverage existing vehicles. FNIHB will develop a national marketing plan with First Nations to provide a clear sense of eHIP's role in support of improved health outcomes. The information included in the plan will flow from the Program's Health Infostructure Strategic Action Plan and Guidelines, overarching policy documents which set the strategic program policy framework and direction. |

4.2 National marketing plan for eHealth. | 4.2 March 2018 | ||||

|

Recommendation 5 Improve performance data collection and analysis across regions and over time on key performance indicators by setting up a Program performance measurement system that takes into consideration the capacity on the ground. |

Management agrees with the recommendation | Recognizing that the delivery of electronic services is not driven by the technology but rather the health services providers, Health Canada as a result has limited authority to standardize reporting protocol among partners. | 5.1 Criteria for standardized annual reporting on eHealth initiatives. | 5.1 March 2019 | Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB | Existing budget |

|

The eHIP national office in collaboration with the regions and the First Nations Information Governance Centre, will explore the use of tools for annual reporting to improve data collection across the program. This would be achieved by:

|

5.2 Annual report based on new criteria. | 5.2 Fall 2019 | ||||

|

Recommendation 6 Develop a long-term plan that is sufficiently flexible to accommodate technology innovation and a commensurate funding strategy for eHIP. |

Management agrees with the recommendation |

The Program will continue to maintain current eHealth tools while looking ahead at sustainability of eHealth components and flexibility to adapt to new innovations in technology that are central to the work of the eHIP. eHIP will develop a five-year plan toward an enriched digital health infrastructure, based on the current Health Infostructure Strategic Action Plan and Guidelines. The plan will take into account these key factors, in alignment with the FNIHB Strategic Plan. |

6.1 Five-year plan to build on and sustain the digital health infrastructure for First Nations communities from 2018 to 2023. | 6.1 March 2018 | Executive Director, CIAD, FNIHB | Existing budget |

1.0 Evaluation Purpose

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of Health Canada's eHealth Infostructure Program (eHIP) for the period of 2011-2012 to 2015-2016.

The evaluation was required by Section 42.1 (1) of the Financial Administration Act (1985), according to which every department shall conduct a review, every five years, of the relevance and effectiveness of each ongoing program for which it is responsible. The Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) defines such a review as an evaluation. The evaluation has been conducted to inform "decision making, improvements, innovation and accountability"Footnote 126 by providing Health Canada's senior management, central agencies, Ministers, Parliamentarians and Canadians with a credible and neutral assessment of the ongoing relevance and performance (defined in terms of effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of eHIP.

2.0 Program Description

2.1 Program Context

In Canada, federal, provincial (F/P) and First Nation governments are focusing on ways to implement innovative information and communication technologies (ICTs) to modernize, transform and improve the way health services are delivered, contain costs and better manage health information for greater accountability and evidence-based decision making. eHealth Infostructure is the development and adoption of modern ICT systems for the purposes of defining, collecting, communicating, managing, disseminating and using data to enable better access, quality and productivity in the health and health care of First Nations.Footnote 36,Footnote 44

Within this context, eHIP works towards the modernization, transformation, improvement and sustainment of health care services in First Nations communities. It supports the combination of information, electronic health applications, technology and people with the intent to provide:Footnote 36

- Optimal health services delivery;

- Optimal health surveillance;

- Effective health reporting, planning and decision making; and,

- Integration/compatibility with other health services delivery systems.

The Program has evolved since the mid-1990s out of the need to align with First Nations' eHealth strategies, health plans and policy directions as well as the movement by provinces and the health industry towards increased use of ICTs to support health service delivery and public health surveillance.Footnote 36,Footnote 44

In April of 2010, Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) approved the Health Infostructure Strategic Action Plan (HISAP), which provides the road map for eHIP and FNIHB information/health information management activities and lays out a long-term strategic framework. HISAP is centred on four key goals:Footnote 36

- An Electronic Health Record (EHR) capacity and capability for all First Nations people by 2020;

- Seamless integration of First Nations infostructures with provincial EHR systems;

- Meaningful, standardized information for decision support available to First Nations, regions and FNIHB; and,

- Collaborative and sustainable partnerships between First Nations, provinces and the federal government.

Since eHIP's mandate is to develop the use of ICTs to support health service delivery in First Nations communities, it needs to function in an environment that includes First Nations communities and regional organizations, other federal partners and provinces, to achieve progress on the different parts of eHealth. This environment combined with technological developments, testing and acceptance by all partners and stakeholders requires long term planning in multiple phases. The current phase of eHealth is still on deploying suitable technologies to support health service delivery in First Nations.

2.2 Program Profile

The implementation of eHIP is a shared responsibility between the national Program headquarters (HQ) in Ottawa and six regional offices: the Atlantic region (ATL, including the provinces of Nova Scotia – (NS), Prince Edward Island – (PEI), Newfoundland and Labrador – (NL) and New Brunswick – (NB)), Québec (QC), Ontario (ON), Manitoba (MB), Saskatchewan (SK) and Alberta (AB).Footnote ii Program HQ sets the strategic Program policy framework and direction. Regional offices engage and work with First Nations regional organizations and communities in eHealth strategic planning, implementation and sustainment. The Program provides funding only to First Nations communities south of 60°.Footnote iii In order to achieve its mandate and goals, eHIP is focused on three principal areas of activity:Footnote 36

- Building the foundation elements that reflect the base requirements of eHIP, without which eHealth components will not operate;

- Implementing components that reflect the key application areas; and,

- Supportive services that provide good governance and management of eHIP.

According to the Program's Guidelines (2012), and as depicted in Figure 1, the Program's foundation elements include:Footnote 36

- Broadband connectivity to connect all on-reserve health facilities to either broadband or high speed Internet services, including connection of the health facility to a central broadband/Internet point within the community, maintenance of the connectivity and related costs.

- Capacity building in three main areas: human resources, infrastructure and governance, to assist with coordinating certain eHealth-related training for health care providers working in First Nations communities, community health workers as well as administrative and support staff.

- Information technology and operations to support the purchase and implementation of the Information Technology (IT) infrastructure, work with First Nations to harmonize community IT policy, support strategies and leverage approaches and resources for efficient community level IT services support, including coordination with other federal departments such as Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC).

- Program/project management, planning and accountability, including the development, support and implementation of effective project management practices related to appropriate and effective resource and activity monitoring and control systems; risk management; change management; project reporting mechanisms; and, effective financial and project planning.

eHealth components include:Footnote 36

- Public Health Information Systems (PHIS), such as Panorama and other systems, through which FNIHB works to include or align national and regional public health surveillance systems for First Nations communities with those being implemented by the provinces.

- Electronic records, including Electronic Medical Records (EMRs), EHRs, client registries and other electronic systems that provide access to an individual's health information. EHRs are a secure and comprehensive electronic record of a person's critical health history that can be accessed by authorized health care providers in the community, province, and eventually across the country. An EMR provides physicians and their patient care team, including nurses and office support staff, with local electronic access to vital patient health information, decision support, billing and office administration tools. A client registry is a data repository that provides, according to Canada Health Infoway (Infoway) an "accurate patient identification to ensure the right health records are associated with the right patient."

- Telehealth to provide access to health care providers and patients to education and clinical sessions and to support community staff by enabling administrative sessions. This component includes the procurement of equipment, integration of the solution into regular service delivery, staff training, and facilitating change management.

- Mobile health (mHealth) or medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices (e.g., mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, Personal Digital Assistants – PDAs). mHealth applications include the use of mobile devices in collecting community and clinical health data, delivery of health care information to practitioners, researchers, and patients, real-time monitoring of patient vital signs and direct provision of care.

Supportive elements include the governance of the Program (strategic oversight, direction and guidance at both the national and regional levels) and partnerships with First Nations regional organizations and communities, other federal organizations, such as Infoway, other federal departments, such as INAC and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), and provincial ministries of health to collaboratively plan, implement and advance the different Program foundation elements and eHealth components.Footnote 36

Figure 1. eHealth components and elements.

Figure 1: eHealth components and elements - Text Description

Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the key eHealth components and elements. The primary eHealth component given emphasis is internet connectivity (also referred to as broadband), followed by: Electronic Records (including electronic medical records, electronic health records, client registries); Public Health Information Systems (including Panorama); Telehealth (including administrative, educational and clinical telehealth sessions); and mobile health, which is also sometimes referred to as mHealth. The key elements of eHealth programming include: capacity building, information technology and operations; program and project management; planning and accountability; governance and partnership engagement.

2.3 Program Narrative

The objective of the Program is to improve access to quality health care services for First Nations individuals, families and communities through the use of eHealth technologies. In order to realize this objective, the Program's activities centre on four key areas, namely:

- Fund the deployment and maintenance of innovative technologies for the delivery of health care services;

- Provide First Nations, FNIHB staff and health care providers with support and capacity development to implement and maintain these innovative technologies;

- Engage stakeholders with a view to implementing and integrating eHealth technologies; and,

- Improve the availability of, and access to, quality data to better inform decision-making and priorities.

These activities lead to several outputs that are expected to contribute to the following immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes:

Immediate

- First Nations communities and health care providers have access to eHealth technologies;

- First Nations individuals, FNIHB staff and health care providers improve their skills/knowledge; and,

- Partners and stakeholders are engaged in collaborative, integrated planning of eHealth technologies.

Intermediate

- First Nations individuals and health care providers are using eHealth technologies for the delivery of health care services; and,

- Interoperable eHealth technologies are implemented in First Nations communities.

Ultimate

- Access, quality and safety of health care services are improved for First Nations individuals, families and communities; and,

- Health care providers have access to provincial health information systems.

The connection between the activity areas and expected outcomes is depicted in the logic model (see Appendix 1 ).Footnote iv The evaluation assessed the degree to which the defined outputs were being produced and outcomes were being achieved over the evaluation time frame.

2.4 Program Alignment and Resources

eHIP is part of Health Canada's Program Alignment Architecture under Strategic Outcome 3: First Nations and Inuit communities and individuals receive health services and benefits that are responsive to their needs so as to improve their health status, Program 3.3: Health Infrastructure Support for First Nations and Inuit, Sub-Program 3.3.2: First Nations and Inuit Health System Transformation.

The Program's financial data for the years 2011-2012 through 2015-2016 are presented in Section 4.5 , Table 17, Table 18 and Table 19. The Program had expenditures of approximately $124 million over five years (2011-2012 to 2015-2016). In 2013, the Program received approximately $100 million from Treasury Board in additional funding over five years to maintain investments and expand eHIP to the remaining 25% of remote/isolated and isolated communities without telehealth (based on feasibility and readiness), and then to other communities. Funding was provided to sustain and increase the number of telehealth sites, sustain and increase connectivity, continue the roll out of PHIS, implement EMRs/EHRs, and support the implementation of mHealth technologies.

3.0 Evaluation Description

3.1 Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

The scope of the evaluation covered the period from April 1st, 2011 to March 31st, 2016 and included all the elements and eHealth components of the Program. The one area of exclusion was the assessment of any services transferred to the British Columbia (BC) First Nations Health Authority on July 2013 in accordance with the British Columbia Tripartite Framework Agreement on First Nation Health Governance and sub-agreements, which will be covered under a separate and forthcoming evaluation.

The evaluation was aligned with the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Results (2016) and considered core issues under the themes of relevance and performance, as shown in Appendix 2. Corresponding to each of the core issues, specific questions were developed based on Program considerations and these guided the evaluation process.

An outcome-based evaluation approach was used for the conduct of the evaluation to assess the progress made towards the achievement of the expected outcomes, whether there were any unintended consequences and what lessons were learnt.

A non-experimental design was used based on the Evaluation Matrix developed during the planning phase of the evaluation, which detailed the evaluation strategy for this Program. The evaluation followed the Agreement for FNIHB Departmental Evaluations developed between the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), FNIHB and the Evaluation Directorate (now the Office of Audit and Evaluation), Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada, regarding the evaluation of FNIHB programming. This included consulting with AFN during the development of the evaluation methodology and providing AFN with the opportunity to review and comment on the instruments used in First Nations communities, the preliminary findings and the evaluation report. Consultation was not conducted with ITK as eHIP does not fund any communities north of 60°.

Data for the evaluation was collected using various methods, which included a document and literature review, an administrative data review and analysis, key informant interviews, case studies, a review and analysis of eHealth approaches across international jurisdictions, and an examination of available financial data for the Program. Details on the data collection and analysis methods are provided in Appendix 3. Data was analyzed by triangulating information gathered through these different methods. The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation were intended as a way to increase the reliability and credibility of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

For the purposes of the evaluation, the terms "partners" and "stakeholders" are used as follows: partners are organizations that assist in the implementation of the Program or that have parallel programs that deal with elements and eHealth components (e.g., provincial governments, federal organizations such as Infoway and departments such as INAC, National Indigenous Organizations such as AFN); stakeholders receive the benefits or the effects of the Program (i.e., health care providers, community health and administrative staff, etc.).

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may have implications for the validity and reliability of evaluation findings and conclusions. Table 1 outlines the limitations encountered during the implementation of the selected methods for this evaluation. Also noted are the mitigation strategies put in place to ensure that the evaluation findings can be used with confidence to guide Program planning and decision making.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation strategy |

| A stakeholder survey of health facility personnel (including Health Directors, Programming Coordinators, nurses and physicians) could not be conducted as it was not possible to obtain a list with a sufficient number of contacts or sufficient contact information. | First hand perspectives of users of the different eHealth technologies were limited, in particular that of health care providers. | The approach to the key informant interviews was revised to gather additional information. The total number of interviews was also increased (from 16 to 40 interviews) to incorporate a larger number of stakeholders. Finally, the number of case studies was also increased (from four to seven) to obtain more detailed regional information. |

| The revised target of 40 interviews to compensate for the stakeholder survey was not achieved. | Limited; interviews with some partners and an additional expert could not be completed. | While the original approach was to use a combination of group and individual interviews, most individual interviews evolved into group interviews due to the multiple eHealth components explored and their inherent complexities (16 individual and 17 group interviews with 75 total participants). |

| The revised target of seven case studies (four site visits and three document reviews) was not achieved. | Limited; an in-depth look at one of the Program's regions was not conducted and an examination of a community not funded by the Program was not conducted. | Five case studies were conducted (four site visits and one document review). The five case studies covered five of the six Program regions. Additional efforts were made through the document and literature review to compensate. In the case of a community not funded by the Program to use as a point of comparison, additional comparison information was gathered through the review and analysis of international jurisdictions. |

| Performance data collected by the Program showed inconsistencies across years, regions and eHealth components. | Performance data reported in the tables shows a number of gaps. | Evaluators worked with Program representatives, both at HQ and the regions, to understand and validate the data analysis. The resulting data was completed and enhanced with information gathered through the document and literature review, key informant interviews and case studies. |

4.0 Findings

4.1 Relevance: Issue #1 – Continued Need for the Program

The Program continues to address a demonstrable need and is responding to the needs of its client population. The needs addressed by the Program are fundamental to improving the health status of First Nations.

The health status of First Nations individuals, families and communities, their access to health care service delivery, and the availability of related health data are behind that of the general Canadian population.Footnote 37 To address this inequity, there is a strong need to enable a First Nations health infostructure capability in line with those of the provinces.

eHIP, through its multipronged approach to increase social capital via connected networks of First Nations community-based health infostructures, aims at bridging this inequity. Many of the partners and stakeholders engaged through interviews and case studies acknowledged the needs addressed by the Program as being fundamental to improving the health status of First Nations. Specifically, the Program provides eHealth services to First Nations communities, reduces travel time and costs as well as displacement from family and community. eHIP helps to connect patients with specialists for diagnostic examinations and follow ups. eHealth also allows for better continuity of care by facilitating information sharing between health care providers on- and off-reserve in support of better care assessment and decision making.

4.2 Relevance: Issue #2 – Alignment with Government Priorities

The Program is aligned with government priorities. These include keeping pace with technology and innovation, contributing to address health system challenges and system reform, and building relationships with Indigenous peoples.

eHIP is aligned with the broader Government of Canada priority to "keep pace" with technology and to renew the relationship with Indigenous peoples. This priority has been highlighted in a number of previous Speeches from the Throne. In 2010, the Government of Canada committed to innovation and keeping pace with technology.Footnote 23 While not specific to eHealth, the 2015 Speech from the Throne underscored the Government's priority to renew relationships between Canada and Indigenous peoples based on co-operation and partnership.Footnote 108

The commitment to technology innovation and collaboration has also been highlighted in the Prime Minister's mandate letter to the Minister of Health in 2015 "advance pan-Canadian collaboration on health innovation to encourage the adoption of new digital health technology to improve access, increase efficiency and improve outcomes for patients".Footnote 35

The priority to "keep pace" with eHealth technology is also demonstrated through a variety of federal budget commitments, including Budget 2013, which allocated $99.8 million to eHIP over five years to maintain progress to date in implementing health technologies (e.g., telehealth/videoconferencing, EMRs, PHIS, broadband connectivity).Footnote 38 Furthermore, through the federal government has invested up to $500 million in Infoway to support continued work on EHRs for Canadians.Footnote 109 Funding was renewed in the 2013 budget to maintain existing investments and expand electronic health services in remote/isolated and isolated First Nation communities and other communities.Footnote 68,Footnote 84

eHIP is also aligned with the Government of Canada's aim to address some health system challenges and to assist in system reform. Through Infoway, the Government of Canada supports provincial and territorial efforts of implementing an interoperable EHR infrastructure (i.e., PHIS, EMRs) by providing funding, and collaboratively developing inter-jurisdictional standards, interoperability requirements and national strategies.Footnote 36

FNIHB has identified addressing eHealth infostructure as a key priority in many corporate planning documents over the past five years. Departmental Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPPs), within the scope of this evaluation, highlight how Health Canada works to support and sustain the use and adoption of appropriate health technologies that enable front line care providers to better deliver health services in First Nations and Inuit communities. RPPs also identify plans to support this priority by funding collaborative efforts with provinces on the expansion of eHealth technology, and through the expansion of telehealth sites, while continuing to support existing health centres with EMRs, and deploying Panorama.Footnote 83,Footnote 84,Footnote 85,Footnote 86 The plan to "improve the efficiency of health care delivery to First Nations and Inuit individuals, families, and communities through the use of eHealth technologies" is also emphasized.Footnote 87

eHIP's objectives align with Health Canada's priorities as outlined in its First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan 2012, which includes ensuring access to quality health services as a key strategic goal for FNIHB. The First Nations and Inuit Health Strategic Plan 2012 sets out strategic objectives such as strengthening access, quality and safety of health services across the continuum of care for First Nations individuals,Footnote v families and communities.Footnote 45

Health Canada's HISAP identifies the following as FNIHB's strategic objectives: ensuring availability of, and access to, quality health services; supporting greater control of the health system by First Nations and Inuit; and, supporting the improvement of First Nations health programs and services through improved integration, harmonization and alignment with federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) health systems.Footnote 44

4.3 Relevance: Issue #3 – Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The Program is well aligned with federal roles and responsibilities.

The Program is well aligned with federal roles and responsibilities. Improving the health of Indigenous people is a shared responsibility between F/P/T governments and Indigenous partners. The federal government's role in the provision or funding of health programs and services to First Nations and Inuit is based on policy and is consistent with the Indian Health Policy 1979, and subsequent departmental mission or mandate statements, rather than legislations or rights.Footnote 40,Footnote 45 The basis for the authority to provide or fund First Nations and Inuit health programs and services is found in the following: 1) section 4 of the Department of Health Act, which provides that the Minister of Health's powers include all matters over which Parliament has jurisdiction relating to the promotion and preservation of the health of the people of Canada not by law assigned to any other department, board or agency of the Government of Canada; 2) votes under the Appropriation Act which authorize Health Canada's spending on FNIHB's programs and services; and, 3) authority from Treasury Board for specific program activities.

Health Canada has overall responsibility for the development and implementation of eHIP and ensuring that funding is appropriately allocated and spent according to established criteria and guidelines.Footnote 36 FNIHB's role is to integrate F/P health systems for the benefit of First Nations, and to increase First Nations community health services capacity to address their own health needs.

4.4 Performance: Issue #4 – Achievement of Expected Outcomes (Effectiveness)

4.4.1 To what extent have the immediate outcomes been achieved?

Immediate outcome #1: First Nations communities and health care providers have access to eHealth technologies

The Program has exceeded its target for broadband connectivity; however, while all eHIP funded First Nations Bands have Internet connectivity, the available bandwidth and connection reliability is variable. The Program has also exceeded targets on PHIS and EMR/EHR implementation. Telehealth continues to grow but its uptake/utilization has been uneven across remote/isolated and isolated communities. mHealth appears promising and is in its developmental phase.

Level of Internet connectivity

For the purposes of eHIP, "connectivity" is defined as the ability of on-reserve health facilities to access the infrastructure required to send and receive health information (e.g., administrative, educational, clinical) using communication technologies (e.g., videoconferencing equipment connected to medical devices and software) and telecommunications services (e.g., broadband Internet). Program activities, therefore, include a focus on providing funding support to connect health facilities to a central broadband/Internet point within the community, which is further connected to external existing networks. Currently, First Nations Bands across the Program's regions have access to some degree of Internet connectivity. Table 2 shows the number of First Nations Bands that are supported by eHIP for connectivity charges. It should be noted that eHIP provides connectivity funding to First Nations communities who use telehealth. According to Program targets, 120 communities should have high-speed broadband connectivity by 2017-2018. Based on available data at the Band level, this target has been exceeded. 0 indicates the number First Nations Bands with nursing stations that receive support from eHIP for Internet connectivity.

| Region | Number of First Nations Bands funded by eHIP by bandwidth/technology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite | < 5 Mbps | > 5 Mbps Total | Total | |

| Atlantic | - | - | 22 | 22 |

| Québec | 6 | 2 | 19 | 27 |

| Ontario | 1 | 6 | 18 | 25 |

| Manitoba | 1 | 24 | 14 | 39 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 6 | 2 | 9 |

| Alberta | - | 10 | 37 | 47 |

| Total | 9 | 48 | 112 | 169 |

|

||||

| Region | Number of First Nations Bands nursing stations funded eHIP by bandwidth/technology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite | < 5 Mbps | > 5 Mbps Total | TotalFootnote vi | |

| Québec | 6 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Ontario | 1 | 5 | 12 | 18 |

| Manitoba | - | 17 | 5 | 22 |

| Saskatchewan | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Alberta | - | 3 | - | 3 |

| Total | 7 | 28 | 21 | 56 |

|

||||

According to partners and stakeholders, in the last five years, broadband connectivity has improved considerably in some communities. Optimal connectivity appears to have been achieved in Alberta, where connectivity is not deemed an issue due to SuperNet's high speed, scalable connectivity. In Saskatchewan, the last mile project to improve bandwidth in rural and remote areas has been a success.Footnote 29 Fibre expansion has also been reported in the Atlantic Region, which is expected to have 29 out of 33 First Nation health centres connected to fibre by the end of 2017-2018. In Québec 30 communities have been working with the First Nations Education Council (FNEC) to enhance bandwidth for eHealth. Connectivity in eastern Ontario has been reported as a success, and the Northwestern Ontario Broadband Expansion Initiative between Bell Aliant and the F/P governments was an extensive project for the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (Internet parity for the northern First Nations).

The health facilities served by satellite communications in Ontario, Manitoba and Québec have less than optimal bandwidth and reliability (due to weather and power outages). In these cases, there is a pressing need to examine alternative technologies since C-band satellite will soon be obsolete. The Manitoba First Nations Technology Council (MFNTC) has announced plans for a project to connect all 63 communities by fibre in 10 years.Footnote 114

Access to/use of provincially integrated/interoperable Public Health Information Systems

PHIS involve secure databases that are accessible by authorized users to enter, extract and analyze health information. The information, typically at the individual level, such as immunization record, is used to better understand the health risks and status of communities as well as to plan interventions to address pressing issues. First Nations are mainly collaborating on implementing the immunization management and vaccine inventory modules of PanoramaFootnote vii or other provincially selected PHIS.

In general, progress to date on the implementation of PHIS has been achieved by prioritizing the implementation of the immunization management and vaccine inventory modules firstFootnote 19 in order to improve supply management, decrease wastage and accurately gauge coverage.Footnote 105 Nonetheless, each province, and First Nations communities within each province, is at different stages of implementation.Footnote 104 The number of First Nations communities that have implemented Panorama and a non-Panorama PHIS in the eHIP regions is shown in Table 4 and Table 5, respectively. According to Program targets, 24 communities should have implemented Panorama or an equivalent provincial integrated PHIS by the end of 2015-2016. Based on available data, this target has been exceeded.

| Region | Fiscal year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

| Atlantic | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Québec | - | 5 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Ontario | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Manitoba | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | - | - | 0 | 25 | 25 |

| Alberta | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | - | 5 | 11 | 37 | 37 |

| Region | Fiscal year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

| Atlantic | - | - | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Québec | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ontario | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Manitoba | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | - | - | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Alberta | - | - | 29 | 38 | 44 |

| Total | - | - | 43 | 41 | 47 |

Table 6 and Table 7 show the number of communities with nursing stations that have access to Panorama and non-Panorama PHIS, respectively.

| Region | Fiscal year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

| Atlantic | - | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Québec | - | - | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Ontario | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Manitoba | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | - | - | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Alberta | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | - | - | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| N/A = The Atlantic region does not have nursing stations. | |||||

| Region | Fiscal year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

| Atlantic | - | - | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Québec | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ontario | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Manitoba | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | - | - | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Alberta | - | - | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | - | - | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| N/A = The Atlantic region does not have nursing stations. | |||||

In the Atlantic region, it has been difficult to achieve integration as each of the four provinces has moved towards different solutions. Newfoundland and Labrador has selected the Client Referral Management System (CRMS), Nova Scotia the Application for Notifiable Disease Surveillance (ANDS) system, New Brunswick the Client Service Delivery System (CSDS), and Prince Edward Island the IMS/immunization System. Provincial integration has been accomplished in two First Nations communities in Prince Edward Island and one in Newfoundland and Labrador.

In Québec, Panorama has been provincially deployed and is only used for vaccination; eHIP supports First Nations communities' Panorama implementation through the First Nations of Québec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission (FNQLHSSC). Eleven communities have implemented Panorama's vaccination module, while other communities are waiting for a simplified version of Panorama. This lightweight version is being developed by the provincial government and deployment is planned for 2018. There is also a Health surveillance portal, sponsored by FNQLHSSC, which collects health data available from the communities.