What we heard: National conversation on advance requests for medical assistance in dying

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 764 KB, 43 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: 2025-10-29

On this page

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Key themes

- Schedule of roundtables

- Roundtable invitees and participants

- Responses to online questionnaire

- Public opinion research questions

Introduction

The purpose of this report is to share with people in Canada a summary of what was heard during the National Conversation on Advance Requests for Medical Assistance in Dying. This report does not provide recommendations or next steps but highlights the main themes and takeaways from the conversation.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all who participated in this national conversation, whether through the online questionnaire, the public opinion research or the roundtable discussions. The input provided through this process is helpful to better understand the diverse perspectives from across Canada on this complex and sensitive issue. The time and effort that individuals and organizations put into providing insightful feedback on this important issue is truly appreciated.

We also extend our gratitude and deep thanks to the following Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and Traditional Helpers who provided traditional openings and closings during the roundtable sessions:

- Colleen Hele Cardinal, Co-founder of the Sixties Scoop Network, Plains Cree nehiyawiskwew originally from Treaty 6 living as a guest on unceded Anishnabe Algonquin territory

- Elaine Kicknosway, Traditional Helper, Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation, Saskatchewan

- Gail Turner, retired nurse, Nunatsiavut

- Navalik Helen Tologanak, Inuit Elder, Cambridge Bay, Nunavut

- Randi Gage, Knowledge Keeper and Indigenous veteran, Manitoba

- Richard Jackson Jr., Traditional man on a healing journey, retired veteran, Lower Nicola Indian Band, British Columbia

You offered traditional approaches, ancestral knowledge, warmth and spirit to this important and sensitive topic.

Context

In Canada, medical assistance in dying (commonly referred to as MAID) is a health service delivered by provincial and territorial health systems as part of end-of-life care. It is delivered within a federal legal framework that sets out strict criteria around who can receive MAID and under what conditions.

The federal legal framework for MAID is set out in the Criminal Code. It has been carefully designed with stringent criteria and safeguards to affirm and protect the inherent and equal value of every person's life.

MAID can only be provided when the criteria for eligibility are met, including that a person must:

- have a serious and incurable medical condition

- be in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability and

- be experiencing enduring and intolerable suffering

An advance request is a request for MAID made by an individual who still has the capacity to make decisions, but before they are eligible or want to receive it. Their intent is that MAID be provided in the future:

- after they have lost the capacity to consent and

- when they meet the eligibility criteria for receiving MAID

In Canada, the provision of MAID based on an advance request is not allowed. The Criminal Code requires that a person have the capacity to consent to receive MAID immediately before it is provided, except in limited circumstances. The only exception to this rule concerns individuals who are close to death, have been assessed as being eligible for MAID and have a date in place as to when they will receive it.

Hypothetical example of an advance request

Charlie is told that he has Alzheimer's disease. His doctor sits down with him to discuss his health care options and what his future could look like with the disease. Charlie learns that he will likely lose his ability to make decisions about his health care in the future.

Later, after thinking about it further, Charlie decides that should his health decline rapidly and he starts experiencing intolerable suffering after he has lost capacity to make health care decisions, he would like to have MAID provided.

Charlie then works with his health care provider's team to develop an advance request. It sets out the conditions that would constitute enduring and intolerable suffering for him after he has lost capacity. For example, these could include not being able to feed himself, get out of bed and not being able to recognize his children for over a month. In his request, Charlie indicates that if these conditions were to arise, it is his explicit wish that he be provided MAID.

A national conversation on advance requests

Since 2015, some national studies have recommended permitting advance requests for individuals with a serious and incurable medical condition leading to loss of capacity, including the Parliamentary Special Joint Committee on MAID in 2023. In addition, several studies and consultations in Quebec led to Quebec enacting a legislative framework for advance requests in June 2023. It brought this legislative framework into force in October 2024, allowing patients to make advance requests in limited circumstances and according to specific rules.

The Government of Canada has consistently taken a cautious approach to expanding eligibility for MAID under the federal legal framework set out in the Criminal Code.

That is why, in October 2024, the Ministers of Health and Justice announced the launch of a national conversation on this issue, with a view to hearing perspectives on advance requests from:

- health care providers and other medical professionals

- provincial and territorial governments

- stakeholder organizations

- persons with lived experience

- persons with disabilities

- Indigenous Peoples

- the public

The goal of the national conversation was to have an initial discussion with people in Canada on advance requests, to inform them about what advance requests were and gather feedback and insights about the issue.

The national conversation took place from late November 2024 to mid-February 2025. It involved an online public questionnaire, public opinion research and virtual roundtables.

It was the first time people outside of Quebec were consulted on this issue. While the intent was to reach as wide a population as possible during the consultation period, not all those who might have wanted to participate may feel they had the opportunity to do so. As such, the national conversation reflects emerging viewpoints and themes on this complex issue.

The results of this national conversation should be considered with these limitations in mind.

Online questionnaire

Over 46,000 participants completed the online questionnaire, which was available online to all individuals over 18 years of age residing in Canada from December 12, 2024, to February 14, 2025. Individuals residing in Canada who had trouble accessing the questionnaire due to technological constraints were provided with alternative approaches to complete the questionnaire.

Respondents were:

- English-speaking - 90%

- women - 75%

- over the age of 55 - 68%

- from urban areas - 66%

By region, the majority of the respondents were from:

- Ontario - 38%

- British Columbia - 23%

- Alberta - 11%

- Quebec - 7%

- New Brunswick - 6%

The online questionnaire results are not meant to be statistically representative but intended to demonstrate the range of public views of over 46,000 people. A standard research sampling approach was used to analyze the open-text questions in the questionnaire until thematic saturation was reached.

Refer to the list of questions and responses.

Advance requests are different than advance medical directives (sometimes called personal or health care directives).

Depending on the province or territory, an advance medical directive:

- allows a person to specify the type of care and treatment they wish to receive in the event of incapacity

- allows a person to name someone to make medical decisions for them if they cannot do it themselves

Advance medical directives cannot be used for MAID.

If they were legal, an advance request:

- is a request for MAID

- is made by the person while they can still have capacity to make decisions, but before they are eligible or want to receive it

However, the Criminal Code does not permit MAID on the basis of an advance request.

Public opinion research

A random sample of 1,000 Canadians were selected to complete the survey between February 3 to 9, 2025, with a margin of error of ±3.1% (plus or minus), 19 times out of 20. The data have been weighted to ensure that the sample distribution reflects the actual Canadian adult population based on Statistics Canada census data.

Refer to the list of questions and responses.

Virtual roundtables

In total, nearly 200 individuals participated in a number of virtual roundtables, including six regional roundtables and five national roundtables. There was also an in-person meeting with the Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia and a special federal-provincial-territorial health officials meeting.

The regional roundtables had a mix of participants, such as:

- health care providers

- Indigenous representatives

- people with lived experience

- provincial and territorial officials, with some provinces and territories being grouped together with breakout sessions as needed (for example, Atlantic, Prairie provinces and the Territories).

In contrast, the national roundtables targeted specific groups, such as:

- health care providers

- disability organizations

- people with lived experience

- national organizations (for example, Alzheimer's Society, Parkinson's Canada, Huntington's Society)

Several members of the public who wrote in fall 2024 to Health Canada to indicate they wished to contribute to the national conversation were included in these roundtables.

Refer to the schedule of roundtables and the full list of stakeholder invitees and participants:

Quebec's advance request framework

On June 7, 2023, the Quebec National Assembly enacted a provincial framework for advance requests for MAID. Quebec brought the framework into force on October 30, 2024, meaning that patients could make advance requests in Quebec. Despite Quebec's legislation, providing MAID based on an advance request in Quebec is not permitted under the Criminal Code.

The framework is anchored in the recognition of the principles of respect for the person and self-determination. Under the Act, Quebec created 2 separate categories of eligibility criteria and safeguards that apply for advance requests (each one applies at different points in time):

- when a person makes an advance request

- when MAID is administered (if all the criteria set out in the act are met)

When making an advance request, the individual must:

- be 18 years or older and insured under Quebec's provincial health insurance plan

- be capable of giving consent to care

- have received a diagnosis of a serious and incurable illness leading to incapacity to give consent to care

- make the request for themselves, in a free and informed manner

For MAID to be administered, the individual must be:

- 18 years or older and insured under Quebec's provincial health insurance plan

- incapable of giving consent to care due to their illness

- exhibiting, on a recurring basis, the clinical manifestations related to their illness described in their advance request

- in a medical state of advanced, irreversible decline in capability

- in a medical state that gives a competent professional cause to believe, based on information at their disposal and their clinical judgment, they are experiencing enduring and unbearable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved under conditions considered tolerable

Quebec has also put in place procedural mechanisms to ensure the advance request reflects the true wishes of the individual and can be easily accessed through a province-wide registry. Two additional features of the framework include:

- A patient may designate a trusted third person in their advance request, who is entrusted to notify the patient's care team when they believe the patient:

- should be assessed based on clinical manifestations related to their illness described in their advance request or

- is experiencing enduring and unbearable physical or psychological suffering

- La Commission sur les soins de fin de vie examines matters related to end-of-life care in Quebec, which means it:

- receives and reviews information on the provision of MAID to ensure compliance with legislative requirements

- submits reports to the Minister about the implementation and the status of end-of-life care in Quebec

For further information, refer to the Government of Québec's Advance request for medical aid in dying.

Key themes

Through this national conversation, participants shared their perspectives and heartfelt and compassionate opinions and advice about MAID, advance requests and end-of-life care more generally.

Four main themes emerged:

- The principle of advance requests was generally supported.

- Concern about how advance requests could be implemented safely in practice.

- Supports for patients, families, friends, caregivers and health care providers.

- Greater health system capacity for end of life is needed.

1. The principle of advance requests was generally supported

Throughout the roundtable discussions, a number of participants indicated that people want the option of being able to make advance requests, in keeping with their values around personal autonomy and choice over their health care needs. Health care providers observed that some of their patients have been surprised to learn that advance requests are not already available under the current MAID framework.

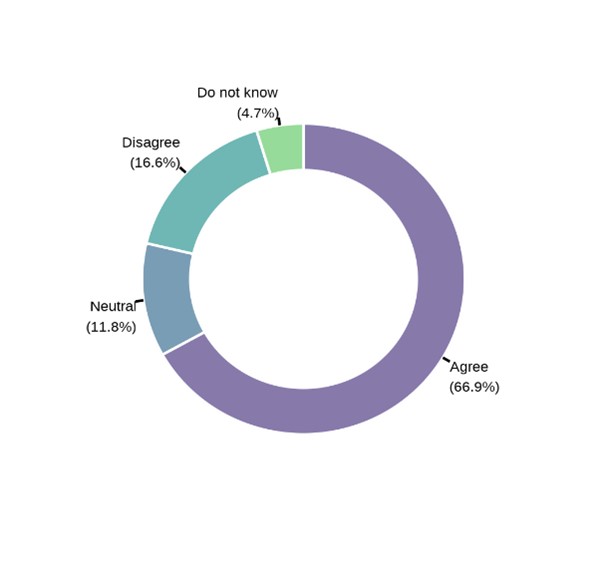

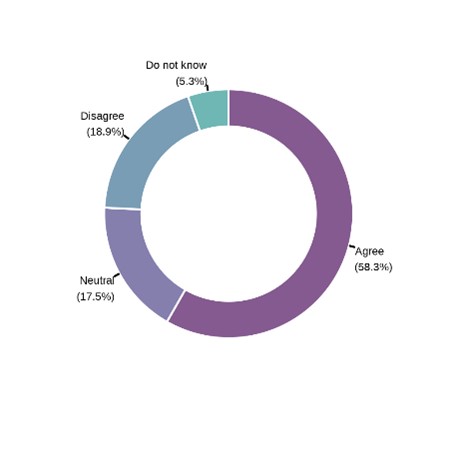

Results from the online questionnaire and public opinion research showed that people in Canada:

- support advance requests for people diagnosed with a serious or incurable condition that will lead to a loss of decision-making capacity (Figure 1):

- respondents to online questionnaire – 69%

- respondents to public opinion research – 67%

- support advance requests for people with a medical condition that could lead to sudden or unexpected loss of capacity to make decisions (for example, high blood pressure that could lead to a severe stroke) (Figure 2):

- online questionnaire respondents – 76%

- public opinion research respondents – 58%

Figure 1 - Alternative text

Donut chart showing support for advance requests for people with an incurable medical condition that will lead to a loss of decision-making capacity.

Text description

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Agree | 66.9 |

| Neutral | 11.8 |

| Disagree | 16.6 |

| Do not know | 4.7 |

Source: Results from public opinion research, February 2025.

Figure 2 - Alternative text

Donut chart showing support for advance requests for people with incurable medical condition that could lead to sudden or unexpected loss of decision-making ability.

Text description

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Agree | 58.3 |

| Neutral | 17.5 |

| Disagree | 18.9 |

| Do not know | 5.3 |

Source: Results from public opinion research, February 2025.

At the roundtables, many persons living with a diagnosis of dementia or other capacity-limiting disease spoke about their desire to:

- make decisions about their future health needs while they are still capable

- have their future care reflect their personal values and life experiences, not those of others

Roundtable participants placed importance on the values of personal agency, autonomy at end of life and person-centred care. Health care providers noted that some of their patients expressed these same views in their care.

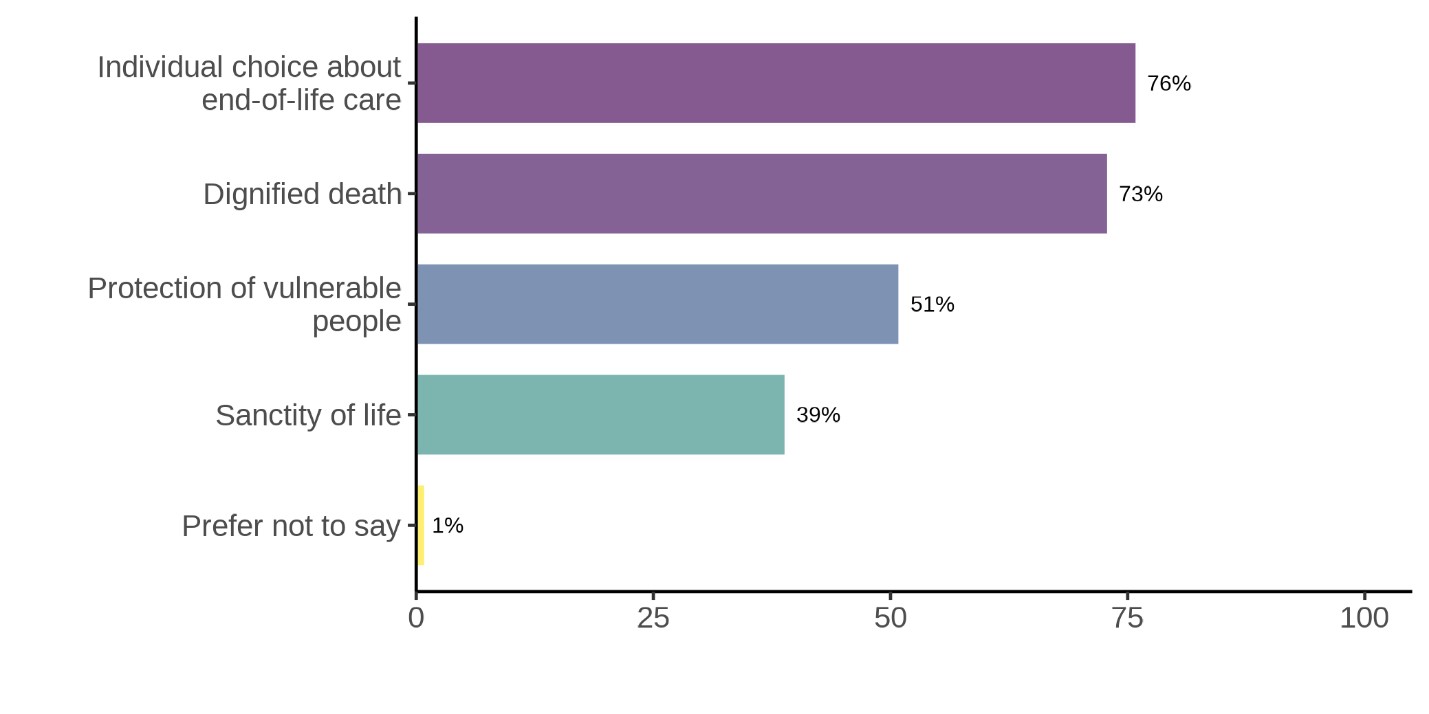

Likewise, 76% of questionnaire respondents said the value that guided them most when thinking about advance requests was "individual choice about end-of-life care", with 73% noting the value of a "dignified death" (Figure 3.).

"Discussion of advance requests rests upon the bedrock of honouring an individual's values, beliefs and their perspective on quality of life, which is inclusive of what suffering means to them."

"One of the main considerations when evaluating whether to permit advance requests for MAID is the recognition that end-of-life and care-planning decisions are deeply personal and reflect the unique values, experiences and perspectives of each individual. While many people living with dementia may lead long and meaningful lives without considering medically assisted death, others may have a very different journey, shaping their views on end-of-life options."

Figure 3 - Alternative text

Bar graph showing level of support for each value that guides respondents most when thinking about advance requests.

Text description

| Value | Response percentage |

|---|---|

| Individual choice about end-of-life care | 76 |

| Dignified death | 73 |

| Protection of vulnerable people | 51 |

| Sanctity of life | 39 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 |

Source: Results from an online questionnaire, December to February 2025.

Some participants expressed a desire for advance requests to avoid the potential of prolonged suffering after they have lost cognitive capacity. They also expressed a desire to maintain control over their final moments and not have that decision delegated to others. Often, personal experiences with loved ones suffering from dementia or other debilitating illnesses influenced participants' views of advance requests. For example, the emotional toll of declining capacity on a loved one contributed to participant support for advance requests.

At several roundtables, some participants highlighted that individuals are choosing to receive MAID earlier than they want for fear that they would lose capacity and not be able to give final consent later.

"End of life. My body, my choice. No dignity in dying a natural death. Die in a manner of one's choosing. My decision for me only!"

Opposition to advance requests

During the national conversation, some participants said they oppose advance requests:

- For a capacity-limiting condition, 26% of questionnaire respondents and 17% of public opinion research respondents opposed advance requests.

- For a medical condition that could lead to a sudden or unexpected loss of capacity, 23% of questionnaire respondents and 19% of public opinion research respondents opposed advance requests.

Similarly, some roundtable participants indicated that no safeguards would be sufficient to safely permit MAID based on an advance request. They spoke to the critical importance of final consent (to be given immediately before MAID is provided) as an essential guardrail. Without it they said that vulnerable individuals would be at risk.

Others noted that people retain autonomy despite having lost capacity. They raised concerns about the potential of a person's past wishes binding their future selves.

The issue of informed consent was also raised during the roundtables. Some participants questioned whether a person can truly give informed consent when making an advance request given that they do not know for certain what they will be experiencing in the future. Many reported that this was particularly true for conditions like dementia where the trajectory of the disease can differ greatly between individuals.

Still others pointed to bias, discrimination, fear and misinformation related to neurocognitive diseases and aging as possibly influencing the desire of some people to make an advance request.

"You are a different person at the point that MAID would be performed than when you made your advance request. We know most people that aren't disabled think living with disability is worse than death. We also know that given time and support that view changes. I think that's a really critical point that applies not just to disabled people but everybody that this is a substituted judgment. There are no magic tools that doctors or anybody can say, you're at the point you said you wanted to be at. These are all messy, complicated things."

2. Concern about how advance requests could be implemented safely in practice

Throughout the roundtable discussions, participants voiced concerns about how advance requests could be safely implemented.

Health care providers noted the importance of the current requirement for final consent from a patient before MAID is provided. It gives providers significant comfort and allows them to be certain that it is what the person wants. They raised concerns about providing MAID in the absence of final consent from someone who has lost decision-making capacity without having very clear and unambiguous rules to guide them. They also spoke to the challenges providers would face in assessing suffering while relying on the conditions set out in an advance request, which may not fit the person's current circumstances.

Likewise, participants at some roundtables wondered about how to manage circumstances where the person meets the conditions set out in their advance request but appears to refuse MAID after they have lost capacity.

"There might be a whole bunch of system issues we have to figure out, but people are asking for this and want this. So I think we can't lose sight of that as we're working through the challenges and the system issues."

A strong governance framework

At the roundtables, there was significant focus on the requirements that would need to be in place if advance requests were to be considered.

Participants pointed to the importance of a comprehensive governance framework to provide clear and unambiguous legal guardrails (such as eligibility, roles and responsibilities) that would set out the rules for how advance requests would operate. The framework should clearly:

- explain how to develop and store advance requests

- be based on informed consent

- reflect an individual's intent, values and wishes

- be easily accessible to health providers

- define the parameters of who can develop an advance request and when MAID can be provided based on clear procedural rules

- include tools and resources to help guide and support clinical decisions based on an advance request

- explain the importance of third-party support and oversight to help promote a person's wishes

- provide the person, their family and health care provider with an avenue for advice, expertise and a mechanism to assist with disputes

Furthermore, participants said the rules, processes and procedures should be standardized and consistent across provinces and territories, given the interprovincial mobility of individuals in Canada.

Sixty-eight percent (68%) of questionnaire and 82% of public opinion research respondents indicated that it is important that the same minimum eligibility criteria and safeguards permitting advance requests for MAID apply across Canada. Many respondents indicated that advance requests should be pan-Canadian and valid regardless of location.

"The issue of interprovincial movement, especially families who are trying to support each other or patients who might be moving from one place to another, needs to be clear. We need either communication or a national registry or some means for addressing the fact that people move."

Clarity on how to develop and store advance requests

Standardized rules and tools are needed to provide sufficient clarity of a person's intent, values and desires

Throughout the national conversation, participants emphasized the importance of ensuring that, when making an advance request, the individual has all the information needed to give informed consent. They should be aware of the specifics about their diagnosis and health condition, the trajectory of the disease, as well as the full suite of options available in terms of care and supports.

Further, participants highlighted the critical importance of a standardized approach and the need for guidelines and rules for providers so that the advance requests were sufficiently clear, thought through and robust. They spoke to the importance of standardized templates that would help in the development of comprehensive requests that reflect the individual's intent, values and desires (Figure 4). Templates would also ensure that the advance request considers multiple scenarios.

It was felt that such a tool would better represent the individual's wishes after they had lost the capacity to express them, providing needed reassurance to providers, families and loved ones.

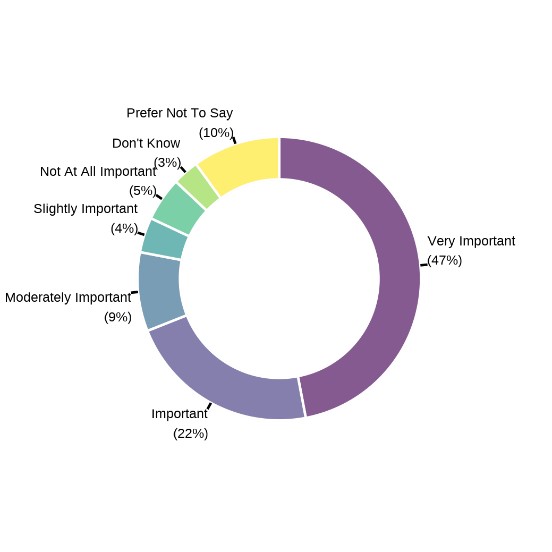

Figure 4 - Alternative text

Donut chart showing level of support for government-designated form for advance requests that's in a person's medical record or a registry.

Text description

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very important | 47 |

| Important | 22 |

| Moderately important | 9 |

| Slightly important | 4 |

| Not at all important | 5 |

| Don't know | 3 |

| Prefer not to say | 10 |

Source: Results from an online questionnaire, December to February 2025.

Participants highlighted the importance of clear, actionable criteria that can guide health care providers as to whether to provide MAID based on an advance request. Health care providers also stressed that the conditions in an advance request that prompt the assessment and provision of MAID must be objectively observable and assessed. This sentiment was also shared by 45% of questionnaire respondents who were concerned about a health care provider having to assess a person based on a vague advance request without clear criteria.

The need for clear rules was also highlighted in instances where an individual appeared to be relatively happy, despite the conditions of their advance request being met, or appeared to be refusing the provision of MAID. Some providers indicated that a refusal could be an automatic response to treatment generally rather than an intentional refusal to receive MAID.

Some participants felt that when making their advance request, an individual should clearly articulate their wishes for either of those circumstances. Other participants felt that in those circumstances, the provision of MAID should not proceed.

"In the document that is the advance request the person should decide what to do. They should say: if I wish to change my mind after I have lost capacity, don't listen to me, etc. You need to avert the situation that people are afraid about. Well, you feel this way now. What about in the future? Presumably you can revoke it, you can change it, and I'm assuming that the legislative scheme will also have the same language that if by gestures, words or otherwise, even though you're incapable, you were refusing the procedure, that it would not be permitted."

Implementation of a registry

At several roundtables, participants highlighted that implementation of advance requests would require those requests to be easily accessible. Of questionnaire respondents, 69% reported that the advance request should be recorded in a person's medical record or a registry.

Many providers expressed concern about how they would learn that an advance request exists and how they would be able to access it. They specifically noted the current barriers in Canadian health systems around the timely exchange of patient information between health providers and institutions.

To enable the timely access of information, roundtable participants spoke to the importance of a registry for storing advance requests. At a minimum, the registry should be province- or territory-wide. It was recognized that most provincial and territorial health systems do not currently have a mechanism to store such information. Participants said such mechanisms would first need to be set up as part of the system to support advance requests.

Further, when setting up the registries, participants indicated they should be interoperable with those of other jurisdictions, so that the information could be easily accessed in other jurisdictions given that Canadians are mobile within the country.

While some expressed interest in a national registry, many acknowledged that this would be difficult to realize given that provinces and territories are responsible for the delivery of health care services, including MAID.

Clear rules and process for changing or revoking an advance request

While there was little support to include an expiry date in an advance request, 72% of questionnaire respondents and those at roundtables noted the importance of a periodic review or some other mechanism to validate the advance request. This would easily enable individuals to consider, withdraw or modify their advance request while they still had decision-making capacity.

Roundtable participants also pointed to the need to have clear rules on how an individual could easily and in a timely way review, modify or revoke an advance request.

Moreover, a process for ongoing review and validation of an advance request was seen as a way to establish the provider-patient relationship over time and confirm the individual's persistent wishes and values. However, many participants noted that this would be highly resource intensive, and that health systems as currently organized would not be able to meet this requirement.

Clarity on eligibility

Clear parameters for eligibility

Participants spoke to the need for strong legal guardrails that set out the parameters on who can be eligible for developing an advance request and when MAID can be provided based on one.

First, participants pointed to the need to ensure that the person making the advance request is doing so voluntarily:

- 71% of questionnaire respondents said it is "very important or important"

- 41% of respondents were concerned about the person feeling pressured by family or others

Health care providers at the roundtables emphasized that individuals should have a diagnosis of a serious and incurable medical condition that will lead to a loss in capacity before they can make an advance request. Many participants noted that having a diagnosis would facilitate an individual's informed decision-making. It would also allow them to discuss with their health care provider the specifics of the medical condition, its trajectory, impact and the range of health and social supports available.

Some thought that the diagnosis should be limited to neurocognitive diseases. Others at the roundtables (and 76% of questionnaire respondents) thought it could be more widely applied. For example, they cited other medical conditions that might lead to sudden or unexpected loss of decision-making capacity, such as hypertension leading to stroke.

A small minority of roundtable participants indicated support for the idea that persons without any diagnosis or medical condition should be able to make an advance request. They said it's important for personal health planning (for example, a person concerned about sudden or unexpected loss of capacity from an injury or accident).

Roles and responsibilities of health care providers and families in developing and assessing criteria under an advance request

Throughout the national conversation, participants pointed to the need for clear rules around roles and responsibilities for developing an advance request and for assessing and making decisions based on criteria in an advance request.

The role of the health care provider was seen as being central in both the development and the assessment of an advance request. For example, 71% of respondents said it's "very important or important" for an individual to develop an advance request with the assistance of a health care provider. Roundtable participants also noted the value of interprofessional teams to support individuals in the development of their advance requests.

Given the specific skill sets of lawyers, some discussed their role in helping to draft clear and actionable advance requests that reflect the intentions of the individual making the advance request.

Participants indicated that while families and caregivers ideally should be part of the discussions when an individual makes an advance request, it should not be a requirement. Fifty-seven percent (57%) of the questionnaire respondents indicated that they were worried that a person's advance request would not be respected by their family. Others stressed that families and caregivers are also on a journey of acceptance as they listen and learn about the individual's wishes and values. If they are not part of the process of developing an advance request then they might not be prepared for, and might be more resistant to, their loved one receiving MAID.

"Family is often upset about choices made with regard to MAID. It can create a lot of disharmony and confusion. The need for people to talk about their intent for their future is something that needs to be encouraged. Right now, it seems to be very hidden and hush-hush not only in public but also within families."

Robust suite of tools and resources for health care providers

Participants said it was important for health care providers to receive training to assist individuals in developing advance requests. They also indicated it's important to support the development of skills and competencies around other topics, such as navigating difficult family dynamics and cultural sensitivity.

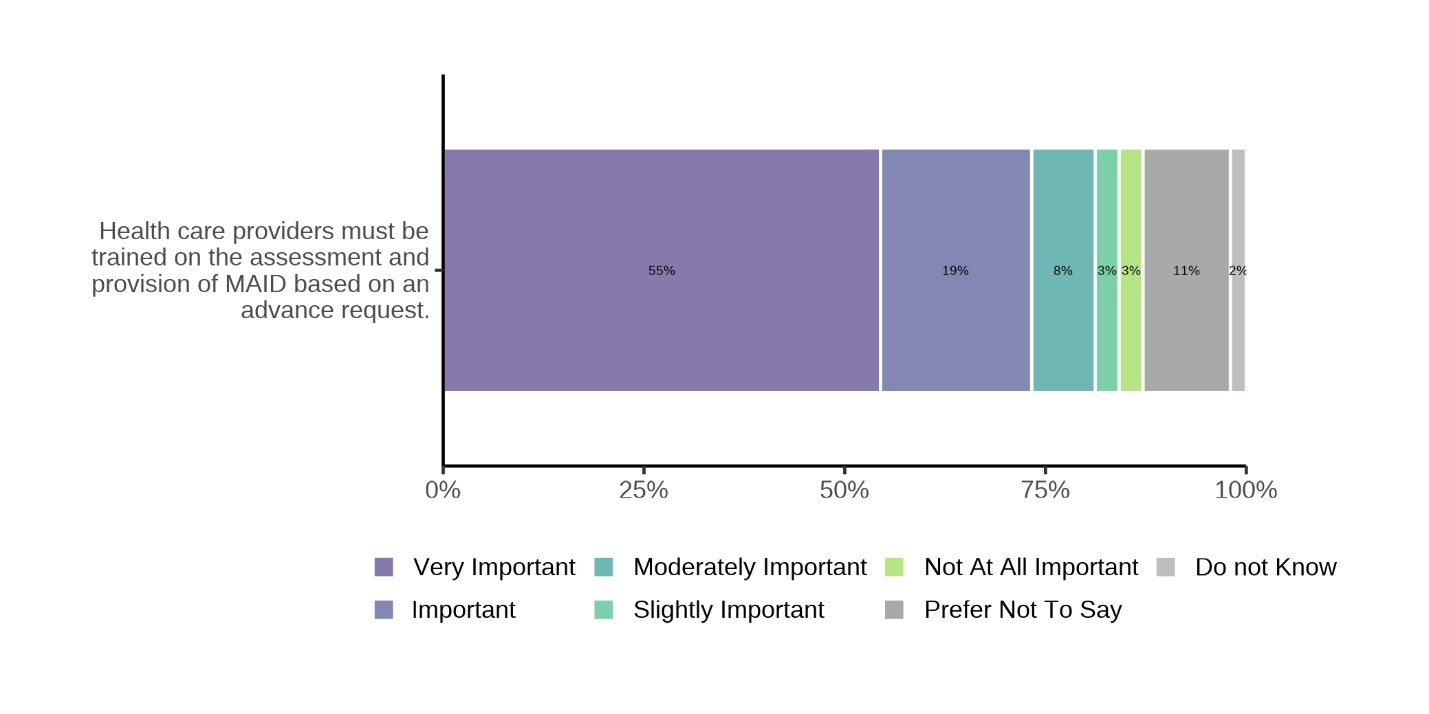

Moreover, given that health care providers would be responsible for administering MAID, it was also recognized that they would need a robust set of tools and resources to effectively make those decisions. Education and training were seen as foundational to effectively supporting health care providers to assess the criteria within advance requests. Seventy-four percent (74%) of respondents reported that it was "very important or important" that health care providers receive specialized MAID training. The training would ensure they have the competencies to make assessments and provide MAID based on the requirements outlined in an individual's advance request (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Alternative text

Bar graph showing level of support for health care providers receiving specialized MAID training.

Text description

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very important | 55 |

| Important | 19 |

| Moderately important | 8 |

| Slightly important | 3 |

| Not at all important | 3 |

| Prefer not to say | 11 |

| Don't know | 2 |

Source: Results from an online questionnaire, December to February 2025.

Roundtable participants also spoke to the importance of clear practice standards and clinical guidelines, so that health care providers could be confident about delivering MAID based on an advance request. Similarly, 68% of questionnaire respondents indicated it's "very important or important" that MAID based on an advance request be provided in accordance with standards developed for health care providers.

Finally, participants also pointed out that health care providers need to be trained to provide culturally appropriate and safe care. In particular, Indigenous participants noted the need for access to culturally appropriate care that was free of racism and discrimination and that respected their traditions.

The role of third parties in the process

The importance of a patient advocate

At the roundtables, participants spoke to the need for a third party who could advocate on behalf of the individual who had made the advance request. While a third party could not request MAID on someone else's behalf, they could serve as the individual's voice to express their wishes as set out in their advance request. Some referred to Quebec's approach of allowing individuals to designate a "trusted third party," which they saw as serving as the individual's advocate.

Roundtable participants said a third-party advocate can:

- inform a health care provider of the existence of an advance request

- prompt the provider to undertake an assessment to confirm whether the conditions in the person's advance request have been met

- communicate with family members, offering insight into the person's values and beliefs

"If we do go forward with advance requests, well somebody is going to have to activate that request at the point. Who is it that brings forward that request? Does the person know what the role is of a trusted third party? Is it going to be a family member who will then say, well, I don't think that dad has recognized me for the past 4 visits and they need constant toileting and spoon feeding. And so this is the point I'm going to trigger it?"

Participants noted that the "trusted third party" would need to be designated by the individual while they still had capacity. This would be a person who the individual felt would best represent their interests after they have lost capacity. Participants also noted that this might not be a family member.

Some also pointed out that not everyone would be in a position to designate a "trusted third party". They suggested that a mechanism would be needed to support these individuals.

Seventy percent (70%) of questionnaire respondents said it's "very important or important" that the advance request designate an individual (such as a family member) who would be aware of the advance request when it was prepared. This person could advise a health care provider of its existence.

Support for providers and families or caregivers through a third-party committee or body

To support providers' assessments and decisions on whether to proceed with MAID based on an advance request, participants noted the need for a mechanism, such as a committee of health care practitioners. This committee would provide guidance for MAID assessors and providers for complex or contentious cases, similar to ethics consultations used in intensive care units.

Others also spoke to such a forum as serving as a mechanism where families and loved ones could seek guidance. It could also help to resolve disputes, such as between families or caregivers over a health care provider's decision related to the advance request.

Some roundtable participants pointed to Ontario's Consent and Capacity Review Board as an example of a successful example for addressing these types of disputes.

"Some type of formal committee or group that if there's a situation or difficulty where things are unclear that people can refer to. You can never know what the absolute truth is in these matters, but sometimes just having a body convened specifically for the purpose of helping you support a decision or clarify a point can be, I think, very reassuring to everybody."

3. Supports for patients, families, caregivers and health care providers

Planning and education

Participants indicated that discussions about an advance request should happen in the context of advance care planning, which is a process by which an individual plans for their future health needs at end of life. During advance care planning, participants noted the importance of individuals being informed of the full range of health care options available to them throughout the trajectory of their disease or condition. This includes all of the health and social supports available to them.

The aim would be to enable a broader conversation about end of life, death and dying. The process of advance care planning can facilitate more robust discussions that lead to a deeper understanding of the person's wishes and values.

"One of the most effective things that advanced care planning in general does for decisions is that it reduces bereavement symptoms, reduces grief symptoms for family members. That's the most powerful effect that it has."

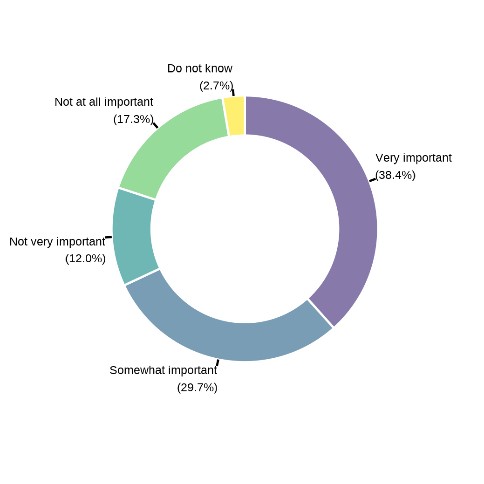

Seventy-one percent (71%) of questionnaire and 68% of public opinion research respondents indicated it's important to have advance requests as an option for future health planning (Figure 6). Further, as part of preparing an advance request, 65% of questionnaire respondents indicated it's "very important or important" that personal health care planning be provided by a health professional or their team. This includes information on living with a capacity-limiting disease, as well as on available care and support.

At some roundtables, participants stressed the importance of rooting advance requests for MAID within the broader continuum of end-of-life care. They called for more holistic approaches that include social and emotional care for the individual.

Figure 6 - Alternative text

Donut graph showing level of support for advance requests as an option for future planning.

Text description

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very important | 38.4 |

| Somewhat important | 29.7 |

| Not very important | 12.0 |

| Not at all important | 17.3 |

| Do not know | 2.7 |

Source: Results from public opinion research, February 2025.

Participants stressed that education is needed to help inform individuals and their loved ones about what to expect over the course of the patient's journey after a diagnosis of a capacity-limiting disease. If the individual wishes, this could also include education about advance requests and MAID. This could cover potential future scenarios for the disease (such as changes that impact an individual's ability to continue their daily activities) and how these could be handled. The aim would be to prepare all parties and reduce:

- potential conflict and disputes among the patient, family members and loved ones, and health care providers

- the guilt that loved ones can experience watching their family member deal with difficult circumstances

It can also help them understand the person's desires as set out in the advance request.

Some roundtable participants also spoke to how, more broadly, education is critical to reducing the stigma associated with aging and dementia, with a view to dispelling fear and bias about capacity-limiting conditions.

There was universal consensus that more support services are currently needed before, during and after an individual's end of life, including counselling, death literacy, grief and bereavement services, and mental health services. Many stressed that these support services were needed for all deaths, not just for those where MAID was administered.

For advance requests, participants noted that the individual making the advance request and their loved ones would need these supports as the individual comes to terms with their diagnosis and as they develop an advance request. Likewise, the need for psychological supports for health care providers was also highlighted, including with respect to delivering MAID. The distress that health care providers might experience when providing MAID to someone who cannot give consent at the time that MAID is administered due to lack of capacity was also noted.

Participants stressed the need for interprofessional team-based care to provide integrated health and social services, with a view to providing individuals with holistic end-of-life care. Many spoke to the important role that social workers and mental health support workers could play as part of a holistic approach to end-of-life care. It was also stressed that they should be part of interprofessional teams delivering end-of-life care, including MAID.

Culturally appropriate and safe care

Participants noted the importance of culturally appropriate supports, including language interpretation. Such supports would ensure the individual and their loved ones understand MAID and that the advance request accurately reflects the circumstances under which the person would want MAID to be provided in the future.

For Indigenous Peoples, participants highlighted the:

- uniqueness of the role of community and family in Indigenous communities at end of life

- importance of respecting community traditions for coming together to provide support

- role of the family, especially when making important decisions such as those related to death and dying

It was also noted that often Indigenous People living in rural and remote communities need to travel elsewhere to receive specialized care. It was strongly emphasized during the national conversation that individuals who must travel away from their community for care must be supported to return to their community at their end of life rather than dying alone in hospital. Participants also identified the critical importance of making a suite of culturally appropriate end-of-life care services, including MAID, available in their communities.

"And I can tell you that I think MAID becomes a struggle for folks who are used to making decisions as families. This is very much an individual decision. I think that kind of flies in the face often of the way that Indigenous folks, Métis, First Nations and Inuit address issues that are literally life and death. So I think it's important to be thinking about the cultural implications as we move forward."

4. Greater health system capacity for end-of-life is needed

With an aging population and growing rates of dementia, greater health system capacity is needed for broad end-of-life care, including MAID

Across the national conversation, there was significant concern that health care systems were already struggling to meet current MAID demands. There was a worry that introducing advance requests would further burden provincial and territorial health systems.

Participants pointed to existing inequities in access to MAID and how expanding MAID eligibility to include advance requests could increase these barriers, especially for people who live in remote, rural, northern and Indigenous communities.

Beyond the requirement for legal parameters and procedural rules and tools, participants said a cautious approach would be essential if a decision was taken to move forward with advance requests. This would allow provincial and territorial health systems to build capacity, including to put in place needed health and social supports.

From a health human resources perspective, the current strain on a broad range of health professionals was a major concern, including palliative care providers and MAID assessors and providers. There was general consensus that implementing advance requests would increase workload, with many pointing to the time that would be needed to properly develop advance requests.

Participants also spoke to concerns about increased administrative burden, already a significant challenge for health care providers. Participants also noted that more MAID assessors and providers would be needed, given current capacity constraints and the likely limited number of providers willing to administer MAID based on an advance request.

"I have serious concerns about the capacity of the health care system to provide access to MAID assessments and providers. At present, patients who are eligible for MAID are waiting an extremely long time and MAID providers are overrun and burnt out. Furthermore, most MAID providers do not want to exclusively provide MAID for the entirety of their clinical practice. If eligibility for MAID is going to be increased, first there needs to be significant support and effort put behind increasing capacity of the system to meet these needs in the form of increased MAID assessors and most importantly MAID providers."

Participants also noted that implementation of advance requests would increase demands on other parts of the health system, particularly primary care, which is currently under significant strain. Some roundtable participants suggested that primary care could play an important role in supporting patients seeking an advance request given its role in providing relationship-based, person-centred care. However, they noted that the sector is not currently well-positioned to do this work.

Building greater capacity for end-of-life care, including more providers who are trained to assess and administer MAID, is essential. Without greater capacity, participants indicated that allowing advance requests would only give the illusion of supporting an individual's autonomy over their end of life should they lose capacity. They worried that the provincial or territorial health system would not be able to honour the advance request.

Broader health and social supports for end of life, not just for MAID

At all the roundtables, participants spoke to the need for more health and social services at end-of-life (not just for MAID). These include the need for more palliative care services, home care supports, high quality long-term care, family supports and social services.

Some participants expressed concerns that in the current context, gaps in palliative care, home care, and other needed health and social supports might result in individuals opting for advance requests out of fear. Their decision might be based on the belief that there could be little health or social care provided to them after they had lost capacity to advocate for themselves. Concerns were raised about the potential for advance requests for MAID to become a default option due to these gaps in care.

With an aging population and growing rates of dementia in Canada, people in Canada expect provincial and territorial health systems to adapt and build capacity for services and supports at end of life. This includes a broad range of end-of-life care services, including MAID, to provide them with the care they need in keeping with their personal values and wishes.

Some roundtable participants advocated for seniors' or end-of-life care strategies at the national or provincial and territorial levels that would:

- explore more holistic, integrated approaches to improve access to end-of-life services

- promote better coordination of the range of health and social services that individuals and their loved ones require at end of life

Participants noted that advance requests and MAID generally should be only one small part of the broader strategy.

Schedule of roundtables

- Meeting with Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia: November 28, 2024

- National Disability Organizations Roundtable: December 16, 2024

- Ontario Regional Roundtable: December 18, 2024

- Quebec Administrative Roundtable: January 13, 2025

- Prairies Regional Roundtable (with break-out rooms) - Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba: January 15, 2025

- British Columbia Regional Roundtable: January 16, 2025

- Territories Regional Roundtable: January 21, 2025

- Atlantic Regional Roundtable (with break-out rooms) - New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador: January 23, 2025

- Health Practitioners National Roundtable: January 27, 2025

- People with Lived Experience and Caregivers National Roundtable: January 28, 2025

- Stakeholder Organizations National Roundtable: January 30, 2025

- Indigenous Elders, Knowledge Keepers and Helpers Roundtable: February 4, 2025

Roundtable invitees and participants

The following list shows the organizations that were invited and had representatives who participated in a roundtable. Some individuals from organizations indicated that they did not formally represent views of their organization. Other individuals who were not affiliated with any organization attended the roundtables. Finally some people represented several organizations.

- 2 Spirits in Motion Society

- Alberta Health Services

- ALS Canada

- Alzheimer Society of Alberta and Northwest Territories

- Alzheimer Society of British Columbia

- Alzheimer Society of Canada

- Alzheimer Society of Nova Scotia

- Association Québécoise pour le droit de mourir dans la dignité

- Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat

- Better Access Alliance

- Bridge C-14

- British Columbia Aboriginal Network on Disability Society

- Canada Life and Health Insurance Association

- Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers

- Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology

- Canadian Association of Social Workers

- Canadian Bar Association

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association

- Canadian Medical Protective Association

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Nurses Protective Society

- Canadian Palliative Care Nursing Association

- Canadian Virtual Hospice

- Centre for Education & Research on Aging and Health, Lakehead University

- Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux de l'Outaouais

- College of Nurses of Ontario

- College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta

- College of Physicians & Surgeons of Manitoba

- College of Physicians & Surgeons of Nova Scotia

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan

- College of Registered Nurses & Midwives of Prince Edward Island

- College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba

- College of Registered Nurses of Saskatchewan

- Commission des soins de fin de vie (Québec)

- Council of Yukon First Nations

- Disability Rights Coalition of Nova Scotia

- Dying with Dignity Canada

- Euthanasia Prevention Coalition

- Family Caregivers of British Columbia

- Fraser Health

- Government of Alberta

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Québec

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Yukon

- Hamilton Health Sciences Centre

- Health PEI

- Heart and Stroke Canada

- Horizon Health Network

- Huntington Society of Canada

- Inclusion Canada

- Indigenous Death Doula Collective, Blackbird Medicines

- Interior Health

- Island Health

- Living with Dignity

- MAID Family Support Society

- MAiDHouse

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Medical Society of Prince Edward Island

- Mental Health Commission of Canada

- Métis Nation British Columbia

- Métis Nation Saskatchewan

- Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia

- National Association of Friendship Centres

- Newfoundland and Labrador Health Services

- Northwest Territories Seniors Society

- Nova Scotia College of Nursing

- Nova Scotia Health Authority

- Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated

- Nurse Practitioners' Association of Ontario

- Nurses and Nurse Practitioners of British Columbia

- Nurses Association of New Brunswick

- Ontario Caregiver Organization

- Ontario Health at Home

- Ontario Hospital Association

- Ontario Medical Association

- Otipemisiwak Métis Government (Métis Nation of Alberta)

- Pallium Canada

- Parkinson Canada

- Physicians' Alliance Against Euthanasia

- Provincial Geriatrics Leadership Ontario

- Saskatchewan Health Authority

- Saskatchewan Seniors Mechanism

- Shared Health Manitoba

- Société québécoise de la déficience intellectuelle

- Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

- The College of Family Physicians of Canada

- Toronto Academic Health Sciences Network

- Vancouver Coastal Health

- Vitalité Health Network

- Yukon Medical Association

The following list shows the organizations that were invited to participate in the roundtable discussions but were unable to attend:

- Acho Dene Koe First Nations

- Advocacy Centre for the Elderly

- Alberta First Nations Health Co-Management

- Assembly of First Nations

- Athabasca Health Authority

- Brain Canada

- British Columbia Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres

- British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives

- British Columbia First Nations Health Authority

- Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence

- Canadian Home Care Association

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Medical Association

- Caregivers Alberta

- Caregivers Nova Scotia

- Christian Medical and Dental Association of Canada

- College and Association of Nurses of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Newfoundland and Labrador

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario

- College of Registered Nurses of Alberta

- College of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland & Labrador

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

- Council of Canadians with Disabilities

- Dene Nation

- Disability Justice Network of Ontario

- DisAbled Women's Network of Canada

- Doctors Manitoba

- Doctors of B.C.

- Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities of Canada

- Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations

- First Nations Health Managers Association

- Foundation for Advancing Family Medicine

- Home Hospice Association

- Inclusion Alberta

- Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada

- Inuit Circumpolar Council

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

- K'atl'odeeche First Nation

- Les Femmes Michif Otipemisiwak

- Mawita'mk Society

- Métis National Council

- Métis Nation of Ontario

- Mi'kmaq Confederacy of PEI

- National Circle for Indigenous Medical Education

- Native Women's Association of Canada

- Nisga'a Valley Health Authority

- Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority

- Northwest Territories Medical Association

- Nunatsiavut Government

- Nunavummi Disabilities Makinnasuaqtiit Society

- Nunavut Public Opinion Research Unit

- Ontario College of Family Physicians

- Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres

- Ontario Nurses Association

- Pauktutiit Inuit Women of Canada

- People First of Canada

- Provincial Health Services Authority, British Columbia

- Qaujigiartiit Health Research Centre

- Regional Indigenous Health Authority (Tajikeimik)

- Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

- Saskatchewan College of Pharmacy Professionals

- Silvermark

- Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority

- Six Nations of the Grand River

- Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Tlicho Government

- Toronto Dementia Network

- Wabanaki Council on Disability

- Wabanaki Two-Spirit Alliance

- Weeneebayko Area Health Authority

- Yukon Medical Council

- Yukon Registered Nurses Association

The following list shows the universities that were invited and had representatives who participated in a roundtable.

- Dalhousie University

- McGill University

- Toronto Metropolitan University, School of Disability Studies

- University of Alberta (did not participate)

- University of British Columbia

- University of Manitoba

- University of Northern British Columbia

- University of Ottawa

Responses to online questionnaire

Notes on methodology

Over 46,000 participants responded to the questionnaire which was open to all adults residing in Canada. The questionnaire results are not meant to be statistically representative but intended to demonstrate the range of public views of over 46,000 people. A standard research sampling approach was used to analyze the open-text questions in the questionnaire until thematic saturation was reached.

Note: Due to rounding, the percentages for each question may not always total 100%.

Questions and responses

Under the current federal legal framework, MAID can only be provided when the criteria for eligibility are met. A person must have a serious and incurable medical condition, be in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability, and be experiencing enduring and intolerable suffering caused by their medical condition. Except in very limited situations, the person must be able to consent immediately before MAID is provided. An individual's death does not need to be reasonably foreseeable to be eligible for medical assistance in dying.

1. To what extent do you support or oppose Canada's current MAID law pursuant to these criteria and safeguards?

- 27% – Strongly oppose

- 11% – Oppose

- 4% – Neither oppose nor support

- 19% – Support

- 37% – Strongly support

- 1% – Don't know

- 1% – Prefer not to say

Some medical conditions (such as dementia, including Alzheimer's disease) can cause people to lose decision-making capacity before they meet other eligibility requirements for MAID.

An advance request is a request for MAID made by an individual who still has the capacity to make decisions but before they are eligible or want to receive MAID. Their intent is that MAID be provided in the future after they have lost the capacity to consent and when they meet the other eligibility criteria for MAID as well as the conditions specified in their advance request.

In Canada, the provision of MAID based on an advance request is currently not allowed. That is because the Criminal Code requires that an eligible person have the capacity to consent to receive MAID immediately before it is provided.

The following questions explore your views and opinions about whether advance requests should be permitted and, if so, under what circumstances.

2. To what extent would you support or oppose adults having the option of making an advance request for MAID in the following situations:

a. after a diagnosis of a serious and incurable medical condition that will lead to the loss of capacity to make decisions (for example, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease)?

- 21% – Strongly oppose

- 4% – Oppose

- 4% – Neither oppose nor support

- 15% – Support

- 54% – Strongly support

- 2% – Don't know

- 0% – Prefer not to say

b. while living with a medical condition that could lead to a sudden or unexpected loss of capacity to make decisions (for example, high blood pressure which could lead to a severe stroke)?

- 20% – Strongly oppose

- 3% – Oppose

- 1% – Neither oppose nor support

- 9% – Support

- 67% – Strongly support

- 0% – Don't know

- 0% – Prefer not to say

3. What values guide you when thinking about advance requests for MAID? Check all that apply.

- 73% – Dignified death

- 76% – Individual choice about end-of-life care

- 51% – Protection of vulnerable people

- 39% – Sanctity of life

- 0% – Don't know

- 1% – Prefer not to say

4. If advance requests for MAID were permitted, how important would it be as an option for your formal personal health planning needs?

- 19% – Not important at all

- 2% – Slightly important

- 3% – Moderately Important

- 13% – Important

- 59% – Very important

- 2% – Don't know

- 2% – Prefer not to say

5. The following considerations have been raised about advance requests. Check any of the considerations that are a concern to you.

- 39% – A person could make an advance request before knowing how well they might adapt to (or tolerate) their medical condition with appropriate supports in the future

- 41% – A person could feel pressured by family or others to make an advance request

- 45% – A health care provider having to assess a person based on a vague advance request without clear criteria

- 57% – A person's advance request not being respected by their family

- 58% – A person's advance request not being supported by their physician or nurse practitioner

- 3% – Don't know

- 3% – Prefer not to say

6. Please specify other considerations about advance requests you have without providing personal identifying information (maximum 250 words). The following are the key thematic areas:

- 40% – Values in favour: Prioritizing choice and self-determination (for example, regardless of family or religious wishes) and prioritizing dignity and quality of life over end of life (for example, recognizing the potential for incapacity)

- 16% – Protections at time of request: Develop clear criteria for advance request eligibility, drafting and providing MAID

- 14% – Process: Individual ability to define the circumstances under which they would want MAID

- 10% – MAID is misused: Current rules around MAID should be tightened (for example, current processes are misused)

- 8% – Process: Flexibility in the process to allow for a change to the advance request (for example, as disease progresses or if new treatment emerges)

- 5% – Protections at time of request: Advance requests should consider an individual's mental state or decision-making capacity at the time of the request

- 5% - Supports: Need resources and supports for individuals, families and loved ones (for example, education and awareness)

- 3% – Supports: Need resources and supports for health practitioners (for example, training and capacity development)

- 2% – Obstacles: Concerns that the advance request process will be too complex, restrictive or bureaucratic

- 2% – Mental illnesses: Mental illnesses should not be considered as eligible conditions for advance requests

- 6% – Other

- 6% – Not applicable

There would be 2 steps to providing MAID based on an advance request. The first would be when the person develops the advance request while still having the capacity to make decisions but before being eligible to receive MAID. The second would be when the assessment for MAID is performed and, if the individual is eligible and the conditions in the advance request have been met, the provision of MAID.

7. Please rate the importance for you of the following potential conditions or safeguards when a person is developing their advance request.

A person must wait for a minimum period of time following their diagnosis of a capacity-limiting illness before they can make an advance request.

- 26% – Not important at all

- 13% – Slightly important

- 14% – Moderately important

- 15% – Important

- 19% – Very important

- 4% – Don't know

- 9% – Prefer not to say

The person making the advance request must do so voluntarily and with the assistance of a health care professional who has received training related to the appropriate development of advance requests.

- 5% – Not important at all

- 4% – Slightly important

- 8% – Moderately important

- 21% – Important

- 50% – Very important

- 2% – Don't know

- 10% – Prefer not to say

The person must be provided personal care planning by a health professional or their team, including information on living with a capacity-limiting disease as well as available care and supports, as part of preparing an advance request.

- 7% – Not important at all

- 7% – Slightly important

- 11% – Moderately important

- 23% – Important

- 42% – Very important

- 2% – Don't know

- 9% – Prefer not to say

The advance request must be made using a government-designated form, must be notarized or witnessed and recorded in a person's medical record or a registry.

- 5% – Not important at all

- 4% – Slightly important

- 9% – Moderately important

- 22% – Important

- 47% – Very important

- 3% – Don't know

- 10% – Prefer not to say

The person who makes the request must validate it periodically (such as every 5 years) and can withdraw and modify it at any time while they still have decision-making capacity.

- 5% – Not important at all

- 4% – Slightly important

- 8% – Moderately important

- 21% – Important

- 51% – Very important

- 1% – Don't know

- 9% – Prefer not to say

The advance request must include designation of another person (such as a family member) who is aware of the advance request as it is prepared and can advise health care providers of its existence.

- 5% – Not important at all

- 4% – Slightly important

- 8% – Moderately important

- 20% – Important

- 50% – Very important

- 3% – Don't know

- 10% – Prefer not to say

8. Please rate the importance for you of the following potential conditions or safeguards when the individual is assessed for MAID and MAID is provided based on an advance request.

There must be a minimum assessment period during which the health care provider must evaluate and confirm the patient is demonstrating the conditions described in their advance request on a recurring basis and that they otherwise meet the eligibility criteria for MAID.

- 8% – Not important at all

- 8% – Slightly important

- 12% – Moderately important

- 25% – Important

- 34% – Very important

- 3% – Don't know

- 10% – Prefer not to say

Health care providers must be trained on the assessment and provision of MAID based on an advance request.

- 3% – Not important at all

- 3% – Slightly important

- 8% – Moderately important

- 19% – Important

- 55% – Very important

- 2% – Don't know

- 11% – Prefer not to say

Any provision of MAID based on an advance request must be provided in accordance with standards developed for health care professionals.

- 4% – Not important at all

- 4% – Slightly important

- 10% – Moderately important

- 22% – Important

- 46% – Very important

- 4% – Don't know

- 11% – Prefer not to say

9. Do you have any comments about other potential conditions and safeguards you think are needed for advance requests? To protect your confidentiality, do not provide information that could be used to identify yourself or others (maximum 250 words). The following are the key thematic areas:

- 23% – General support for MAID, focusing on dignity, autonomy and closure for families and loved ones

- 21% – Protections at time of request: Develop clear criteria for advance request eligibility, drafting and providing MAID

- 12% – Protections at time of request: Safeguards should depend on the health condition, with particular considerations for dementia, Alzheimer's or mental illnesses

- 9% – General opposition to MAID, focusing on sanctity of life and risk of exploitation

- 7% – Obstacles: Safeguards should not create greater obstacles to avail of MAID

- 7% – Supports: Need resources and supports for individuals, families and loved ones (for example, education and awareness)

- 7% – Supports: Consider the potentially helpful or harmful role of families, caregivers and loved ones

- 4% – Supports: Need for resources and supports for health practitioners

- 4% – Obstacles: Challenges with individuals expressing wishes and communicating consent at time of providing MAID for advance requests

- 3% – Health system limitations: Implementation of any conditions and safeguards is hindered by health system strain

- 3% – Feedback on questionnaire or consultation process

- 11% – No further comments

- 3% – Other

- 2% – Not applicable

10. In addition to no longer having capacity to make decisions, do you think a person should be demonstrating another serious physical or psychological limitation (such as loss of ability to communicate or loss of ability to perform activities of daily living, like eating or dressing) to be eligible to receive MAID based on their advance request?

- 28% – Yes

- 46% – No

- 14% – Don't know

- 12% – Prefer not to say

11. After a person has lost capacity to make decisions, should a person other than the person who made the advance request (such as a member of the family) have the authority to withdraw or modify the person's advance request?

- 13% – Yes

- 70% – No

- 9% – Don't know

- 9% – Prefer not to say

12. Consider a person who no longer has the capacity to make decisions and meets all of the conditions outlined in their advance request that describe enduring and intolerable suffering and advance decline in capability, and yet they appear to be content. Select the statement that best describes what you think should happen next:

- 59% – The person should receive MAID because all of the conditions set out in their advance request have been met as this is in keeping with their express wishes.

- 22% – The person should not receive MAID despite meeting all of the conditions in their advance request but should be reassessed at a later time when they no longer appear to be content.

- 9% – Don't know

- 10% – Prefer not to say

13. How important would it be to have the same minimum eligibility criteria and safeguards permitting advance requests for MAID apply across every province and territory in Canada?

- 7% – Not important at all

- 3% – Slightly important

- 9% – Moderately important

- 21% – Important

- 47% – Very important

- 4% – Don't know

- 9% – Prefer not to say

Demographic questions

1. What is your gender?

- 21% – Man

- 75% – Woman

- 0% – Non-binary person

- 3% – Prefer not to answer

- 0% – Other

2. What is your age?

- 1% – 18 to 24

- 5% – 25 to 34

- 9% – 35 to 44

- 13% – 45 to 54

- 21% – 55 to 64

- 29% – 65 to 74

- 16% – 75 to 84

- 2% – 85+

- 4% – Prefer not to say

3. Are you participating in this questionnaire as an individual or as a representative of an organization? Select 1 response.

- 98% – Individual

- 1% – Representative of an organization

- 1% – Prefer not to say

4. If an organization: What service or population group does your organization serve? Select all that apply. Represents a sample base of 260 respondents.

- 14% – Members of First Nations, Inuit or Métis communities

- 23% – Persons with disabilities

- 37% – Frontline health care service

- 10% – Veterans

- 12% – None of the above

- 2% – Not applicable

- 14% – Prefer not to say

- 33% – Other

5. Do you self-identify with any of the following groups? Select all that apply.

- 2% – First Nations, Inuit or Métis

- 10% – A person with a disability

- 9% – A person living with a condition that could lead to a loss in decision-making capacity

- 14 – Caregiver

- 11% – Health care provider

- 1% – Veteran

- 47% – None of the above

- 4% – Not applicable

- 6% – Prefer not to say

- 6% – Other

6. Province or territory:

- 38% – Ontario

- 23% – British Columbia

- 7% – Quebec

- 6% – New Brunswick

- 11% – Alberta

- 4% – Nova Scotia

- 3% – Manitoba

- 4% – Saskatchewan

- 1% – Newfoundland and Labrador

- 1% – Prince Edward Island

- 0% – Yukon

- 0% – Northwest Territories

- 0% – Nunavut

- 3% – Prefer not to say

7. Language

- 90% – English

- 10% – French

8. Region

- 66% – Urban

- 29% – Rural

- 5% – Prefer not to say

Public opinion research questions

Methodology

We conducted a survey on MAID with a random sample of 1,000 Canadians between February 3 and February 9, 2025. The data have been weighted to ensure that the sample distribution reflects the actual Canadian adult population according to Statistics Canada census data.

A sample of this size (n = 1,000) has a margin of error of about 3.1%, 19 times out of 20. Due to rounding, the percentages for each question may not always total 100%.

Questions

1. Have you seen, read or heard anything recently about medical assistance in dying?

- 46.4% – Yes

- 52.9% – No

- 0.6% - Don't know

2. If yes, what have you seen, read or heard?

- 25.8% – Personal experience with MAID through friends and family

- 25.1% – MAID is being made available, an accessible option

- 12.0% – MAID is under review, policies are being adjusted

- 9.3% – Hearing arguments in opposition to MAID

- 9.2% – General controversy surrounding MAID, controversial topic

- 6.8% – Hearing about MAID in the media (TV, radio, newspaper, social media)

- 5.0% – Hearing about MAID from friends and family, word of mouth

- 5.0% – Hearing both sides of the issue, arguments for and against MAID

- 4.7% – Hearing arguments in support of MAID (general)

- 2.7% – Hearing examples of people who would benefit MAID

- 2.5% – MAID is legal at a provincial level (for example, Quebec or Alberta)

- 2.4% – Details about MAID are vague, need more information

- 2.1% – Hearing cases of people receiving MAID

- 1.4% – MAID is legal in Canada, people have the right to MAID

- 5.7% – Don't know

3. To what extent do you support or oppose MAID on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 means "strongly disagree" and 10 means "strongly agree"?

- 40.0% – (10) Strongly support

- 8.0% – (9)

- 12.5% – (8)

- 6.8% – (7)

- 2.9% – (6)

- 11.2% – (5)

- 0.7% – (4)

- 1.6% – (3)

- 1.5% – (2)

- 10.0% – (1) Strongly oppose

- 4.8% – Don't know

4. On a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means "strongly oppose" and 10 means "strongly support" to what extent do you agree or disagree with allowing advance requests for medical assistance in dying for: