Draft technical document guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality - Antimony: Health considerations, derivation of health-based value

On this page

- Kinetics

- Health effects

- Mode of action

- Selected key study

- Derivation of the health-based value (HBV)

Kinetics

Absorption

Gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of antimony has been shown in humans and several animal species (Environment Canada and Health Canada, 2010; Borborema et al., 2013). The current scientific literature indicates GI absorption of antimony is low and dependant on the solubility and chemical form (oxidation state) (WHO, 2003; OEHHA 2016; ATSDR, 2019). GI absorption of the relatively insoluble ATO in humans is reported as approximately 1% (EU, 2008). From acute intoxication (poisoning) data for 4 individuals exposed to antimony potassium tartrate (APT), a highly water soluble form of antimony, 5% absorption was reported (Iffland and Bösche 1987; Lauwers et al. 1990). The International Commission on Radiological Protection recommends the use of a 10% absorption factor for the dietary intake of antimony and due to variability in the absorption data available, an absorption of 5% is recommended for situations where specific information is not available (ICRP, 1981; 1995; 2017). Data on the dermal absorption of antimony is limited. The low water/lipid solubilities of antimony and its compounds suggest that dermal exposure is not a significant route of exposure (OEHHA, 2016). In a study by Roper and Stupart (2006), skin samples from the abdomen (1 sample) and breast (5 samples) of women were exposed in vitro to 100 μg/cm2 and 300 μg/cm2 of diantimony trioxide resulting in total estimated dermal absorptions of 0.26% and 0.14%, respectively, after a 24-hour exposure period.

Distribution

Once absorbed, ingested antimony is distributed mainly to the liver, spleen and bone and, to a lesser extent, the gall bladder, kidneys, nails, ovaries, testes, thyroid and hair (DFG, 2007; Tylenda et al., 2015; Kip et al., 2017; Sztajnkrycer, 2017). Studies in humans (Gerhardsson et al., 1982, 1988; Kip et al., 2017), rhesus monkeys (Friedrich et al., 2012) and rats (Poon et al., 1998; Coelho et al., 2014a) using radioactively labelled (Sb124) sodium antimony mercapto-succinate, meglumine antimoniate and APT, respectively, indicate that accumulation is dose-dependent. A study by Sunagawa (1981) in rats found that exposure to metallic antimony resulted in similar antimony concentrations in the liver and blood, however, exposure to antimony trioxide resulted in a 10-fold higher antimony concentration in the blood compared to the liver. The distribution of the different oxidation states (for example, +3, +5) following oral exposure to antimony is not known (ECCC and Health Canada, 2020). In the blood, pentavalent antimony is primarily found in the serum (Felicetti et al., 1974; Edel et al., 1983; Ribeiro et al., 2010) and trivalent antimony is primarily found in the hemoglobin fraction of red blood cells (Lippincott et al., 1947; Edel et al., 1983; Newton et al. 1994; Poon et al. 1998; Kobayashi and Ogra, 2009). However, both trivalent and pentavalent antimony have been shown to enter red blood cells (Quiroz et al. 2013; Lopez et al. 2015; Barrera et al. 2016). In vitro studies have found that pentavalent antimony can enter erythrocytes via protein channels (Quiroz et al. 2013; Barrera et al. 2016).

Trans-placental and mammary gland (via maternal milk) transfers of antimony have been reported in humans and animals (Miranda et al., 2006; Coelho et al., 2014a; NTP, 2018; Li et al., 2019).

Metabolism

In vitro evidence of the metabolism of ingested antimony in mammals shows intracellular interconversion between both the Sb(III) and Sb(V) valence states (NTP, 2018). For ingested antimony, there is a reduction of Sb(V) into Sb(III) which is dose-dependent and promoted by acidic pH and elevated temperature (25oC to 37oC) (Frezard et al., 2001; DFG, 2007; NTP, 2018). This reduction is followed by the conjugation of Sb(III) with reduced glutathione (GSH), and the subsequent enterohepatic recycling of the Sb(III)-GSH complex (Bailly et al., 1991; DFG, 2007).

There is no convincing evidence for methylation of antimony in mammals although methylated forms of antimony have been reported in the environment (Filella and Williams, 2010; Herath et al., 2017; Sztajnkrycer, 2017).

Elimination

Ingested antimony is primarily excreted through the feces and to a lesser extent the urine (Environment Canada and Health Canada, 2010; Borborema et al., 2013; OEHHA, 2016). Sb(V) is preferentially excreted in the urine, whereas Sb(III) is excreted in the feces (Friedrich et al., 2012; Sztajnkrycer, 2017). Evidence from human pharmacokinetic studies indicates that the pharmacokinetics of antimony is age-dependent with young children eliminating more of the chemical than adults (Cruz et al., 2007). In patients treated with meglumine antimoniate (5 mg Sb/kg bw per day by intramuscular injection) for 30 days, half-lives for elimination were reported to range from 24 to 72 hours for the rapid excretion phase and a half-life of > 50 days for the slow elimination phase (Miekeley et al., 2002).

Health effects

The information on the toxicity of ingested antimony and its compounds has been described elsewhere in more detail (OEHHA, 2016; NTP, 2018; ATSDR, 2019). This assessment focuses on oral exposure data which is most relevant for exposure from drinking water. According to the available data, oral exposure to antimony may induce adverse effects mainly on the GI tract (for example, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea) and the liver. Kidney, cardiovascular, metabolic (for example, decreased serum glucose levels) and developmental adverse effects have also been reported (Lauwers et al., 1990; Hepburn et al., 1993; WHO, 2003; Alvarez et al., 2005; OEHHA, 2016; Scinicariello and Buser, 2016; Sztajnkrycer, 2017; NTP, 2018; ATSDR, 2019).

Health effects in humans

There are limited data on the toxicological effects of antimony in humans. The majority of the human data in the literature come from the reported side effects observed during therapeutic applications of antimony-based drugs (antimonials). Side effects observed following therapeutic-level doses include GI tract distress, cardiotoxicity, pancreatitis, hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity (Hepburn et al., 1994; Oliveira et al., 2009, 2011; Mlika et al., 2012; Wise et al., 2012). Although these studies provide useful insight into the potential effects following antimony exposure, the relevance of these reported effects following environmental exposures is uncertain due to the poor absorption of antimony compounds.

Hepatotoxicity

In humans exposed to antimony for the treatment of leishmaniasis (a parasitic disease), hepatocellular damage and impaired liver metabolism has been demonstrated (OEHHA, 2016). Patients treated for cutaneous leishmaniasis have been shown to have alterations in liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase and glutathione S-transferase B1, which indicate potential liver damage and impairment of liver metabolism (Hepburn et al., 1993, 1994; Andersen et al., 2005; Oliveira et al., 2011). In the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis, impaired peroxisomal function, hepatitis, and hepatic failure were observed in patients (Gupta et al., 2009; Oliveira et al., 2009). Patients treated for mucosal leishmaniasis also showed increased liver enzymes (Franke et al., 1990; Saenz et al., 1991).

Gastrointestinal effects

Antimony has long been known for its emetic properties (ATSDR, 2019). Although rarely reported some cases of poisoning have occurred after accidental ingestion of beverages or food contaminated with antimony. The most frequently reported effects from ingested antimony poisoning include GI disturbances (for example, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea). Exposure to levels between 0.4 and 0.9 mg Sb/kg bw has been reported to induce vomiting in adults (Lauwers et al., 1990; Health Canada, 1997; Cooper and Harrison, 2009; Sundar and Chakravarty, 2010; Tylenda et al., 2015; Sztajnkrycer, 2017; NTP, 2018).

Reproductive and developmental effects

Data from retrospective and prospective studies in pregnant women treated for visceral leishmaniasis with therapeutic doses of antimony (that is, 20 mg/kg sodium stibogluconate, i.m., once daily for 30 days) suggest an association between antimony and developmental toxicity (that is, spontaneous abortions) (Mueller et al., 2006; Adam et al., 2009). Moreover, this effect appears to be specific to the first (Mueller et al., 2006; Adam et al., 2009; Forns et al., 2014) and possibly second trimesters of pregnancy (Mueller et al., 2006). As previously mentioned, given the poor absorption of antimony compounds, the relevance of such effects following environmental exposures is uncertain. A recent study investigated the impact of a mixture of metals on fetal size during mid-pregnancy in a largely Hispanic cohort in Los Angeles (Howe et al., 2021). The authors found an association between urinary antimony (as a component of a mixture of urinary metals including total arsenic, barium, cadmium, mercury, molybdenum, tin, cobalt, nickel and thallium) and reduced fetal weight. It was concluded that the analysis identified antimony as a potential element of concern due to its inverse association with fetal size and more investigation of antimony exposure within this specific study population is required.

To assess the relationship between prenatal blood levels of metals and spontaneous abortion (SA) risk, Vigeh et al. (2021) compared blood concentrations of some heavy metals in samples taken from apparently healthy mothers recruited in the Tehran Environment and Neurodevelopmental Defects (TEND) study who subsequently experienced SA with mothers whose pregnancy ended in live births. During early gestation, 206 women were enrolled and followed until fetal abortion or successful deliveries occurred. The mean blood levels of lead, antimony and nickel were higher in SA mothers than mothers with ongoing pregnancy. However, the difference was not statistically significant. When adjusted for covariates, a significant association between maternal age and the risk of SA in all regression models was observed. Only antimony had a noticeable positive relation with the risk of SA (odds ratio: 1.65, 95% confidence interval: 1.08 to 2.52, P value: 0.02) compared to the other metals. Pearson's correlation coefficient showed significant (P < 0.05) positive correlations among prenatal blood metals levels, except for nickel. The authors concluded that although the study did not provide strong evidence for metal-induced effects on the occurrence of SA at relatively low-levels, these metals should be avoided in women who plan pregnancy and/or during the early stages of gestation to prevent the potential for adverse effects.

Other endpoints

Data from human antimonials therapy and chronic inhalation of antimony-containing dusts in the workplace indicate that antimony may also induce nephrotoxicity, cardiotoxicity as well as effects on the musculoskeletal system, pancreas and nervous system (Hepburn et al., 1993; Hepburn et al., 1994; Health Canada, 1997; WHO, 2003; OEHHA, 2016; ATSDR, 2019).

Health effects in experimental animals

Antimony is acutely toxic to experimental animals, as indicated by the oral median lethal dose (LD50) values reported in the literature including 115 and 600 mg/kg bw for APT in rabbits/rats and mice, respectively (Omura et al., 2002; WHO, 2003). Oral LD50 values higher than 2,000 mg/kg bw have been reported for sodium hexahydroxoantimonate (ECHA, 2014) and above 20,000 mg/kg bw for ATO (WHO, 2003).

Similar to humans, data on the toxic effects of antimony following oral exposure in experimental animals is limited but indicate that exposure may result in a number of adverse health effects. Acute oral exposure to Sb(III) and Sb(V) has been shown to affect the GI tract (NTP, 1992; Tylenda et al., 2015). Subchronic and chronic oral exposures (mostly to ATO, APT, antimony trichloride) have been shown to impact the liver, thyroid and kidneys (Sunagawa, 1981; NTP, 1992; Poon et al., 1998; Hext et al., 1999; NTP, 2018), as well as potentially induce adverse developmental effects (Imai and Nakamura, 2006; Chen et al., 2010; ECHA, 2014, Khosravi et al., 2018). These effects have also been demonstrated in animal injection studies (Paumgartten and Chahoud, 2001; Omura et al., 2002; Grimaldi et al., 2010; Coelho et al., 2014b; Kato et al., 2014), however, given this route of exposure is not applicable to the drinking water exposure context, these studies will not be discussed further in this risk assessment. Other reported effects include altered blood glucose (Schroeder et al., 1970; Poon et al., 1998) and lipid levels (Schroeder et al., 1970; Poon et al., 1998; Hext et al., 1999) following subchronic and chronic exposures of rats to Sb(III) (that is, APT or ATO) via drinking water or food. The results from antimonial studies also suggest the potential for cardiotoxicity and nephrotoxicity of antimony (NTP, 1992; Tirmenstein et al., 1995; Poon et al., 1998; Tylenda et al., 2015) as well as its oestrogenic potential (Choe et al., 2003; Darbre, 2006). Table 4 provides a summary of the relevant animal toxicity studies available for antimony.

| Species, number | Exposure duration | Compound and dose(s) (as mg Sb/kg bw per day) | POD (mg Sb/kg bw per day) | Critical effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6C3F1 mice (10/sex/dose) | 14 days (ad libitum) | APT in drinking water: 0, 21, 36, 63, 99, 150 | NOAEL = 99 | Forestomach lesions in the high dose group. Dose-related increases in relative liver weight; lesions in the liver of most mice in the high dose group. | NTP (1992) |

| F344/N rats (10/sex/dose) | 14 days (ad libitum) | APT in drinking water: 0, 5.8, 10, 21, 34, 61 | NOAEL = 61 | Increase in relative liver weight in the high dose group. | NTP (1992) |

| Sprague-Dawley rats (15/sex/dose) | 13 weeks (and 4 week recovery for high dose animals) | APT in drinking water: males: 0.06, 0.56, 5.58, and 42.17; females: 0.06, 0.64, 6.13 and 45.69 | NOAEL = 0.06 | Dose-related increases in liver anisokaryosis reaching moderate severity in the high dose group. Dose-dependent decreased serum glucose levels in females reaching statistical significance in the three highest dose groups. Dose-related accumulation of antimony in red blood cells and the spleen with marked accumulation beginning in the second lowest dose group and persistence of antimony in the spleen beyond recovery. | Poon et al. (1998) |

| Wistar rats (Alpk:APSD strain; 12/sex/dose) | 90 days | ATO by diet: males: 0, 70, 353, 1 408; females: 0, 81, 413, 1 570 | NOAEL = 1 408 | Small increase in liver weight, small decrease in plasma alkaline phosphatase activity and small increase in plasma aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels in the high dose group. No histological effects on liver. | Hext et al. (1999) |

| Wistar rats (male; 5/dose) | 24 weeks | ATO by diet: 0, 418, 836 | LOEL = 418 | Liver histopathological changes and increased aspartate transaminase (AST) activity. | Sunagawa (1981) |

| SD rats, female (20/dose) | GD 6 to 19 | Sodium hexahydroxoantimonate via gavage: 0, 49, 148, 493 | NOAEL = 49 | Increased (non-significant) incidence in delayed skeletal development in the mid and high dose groups. Most values were only slightly above historical control data. When considering skeletal malformations overall, incidence was observed in 99.3% to 100% of fetuses and 100% of litters including controls. No reproductive toxicity, embryotoxicity or fetotoxicity. | ECHA (2014) |

| Long-Evans rats (50 to 60/sex/dose) | Lifetime | APT: 0 and 0.43 in drinking water; dose estimated by the U.S. EPA (1992) | LOAEL = 0.43 | Reduced survival rate in males and females. At the median life spans, survival was reduced by 106 and 107 days for males and females, respectively, compared to controls. Non-fasting serum glucose levels were reduced by 28% to 30% in the dosed animals. | Schroeder et al. (1970) |

APT – antimony potassium tartrate; ATO – antimony trioxide; GD – gestational day; LOAEL – lowest observed adverse effect level; LOEL – lowest observed effect level; NOAEL – no observed adverse effect level; POD – point of departure; SD – Sprague-Dawley

Genotoxicity and carcinogenicity

Both the genotoxicity and the carcinogenicity of antimony and its compounds have been previously reviewed (WHO, 2003; Porquet and Filella, 2007; NTP, 2018; ATSDR, 2019). For genotoxicity, overall, in vivo studies for antimony trioxide were negative for clastogenicity and bone marrow aberrations, and chromosomal aberrations and micronuclei formation were negative for in vivo assays. Occupational studies were also negative for micronuclei formation and sister chromatid exchange. In vitro assays were generally negative for gene mutations. However, some positive responses for antimony trichloride and pentachloride (highly soluble antimony substances) in chromosomal aberration and micronuclei formation assays were observed. Overall, there is low concern for genotoxicity for the antimony substances in the group (ECCC and Health Canada, 2020).

IARC classified antimony trioxide as a group 2B carcinogen (IARC 1989, 2014) by the inhalation route. The European Commission classified antimony trioxide as a Category 2 carcinogen (suspected human carcinogen) under the regulation on classification, labeling and packaging (CLP-Regulation (CE) No 1272/2008) (EU, 2008a). According to a European Union risk assessment report, antimony trioxide is classified as a Category 3 carcinogen (Annex 1, Directive 67/548/EEC) based on limited evidence of a carcinogenic effect (EU, 2008). The EU (2008) further indicated that there is no evidence of tumours following oral exposure to antimony. Cancer incidence was not increased in chronic studies where mice and rats were orally exposed to APT (ATSDR 2019).

Mode of action

The mode of action for antimony-induced toxicity in mammals has not been fully elucidated. However, the current evidence indicates that treatment-related hepatotoxicity likely involves oxidative stress (NTP, 2018) which is preceded by the reduction of Sb(V) (the form most prevalent in drinking water) to its Sb(III) form. Both the in vitro reduction of Sb(V) to Sb(III) (which is dose-dependent, and favoured at acidic pH and high temperature) and the involvement of Sb(III) in hepatotoxicity have been demonstrated (Frezard et al., 2001; DFG, 2007; Kato et al., 2014). Thiol homeostasis imbalance has also been demonstrated through depletion of intracellular glutathione and inhibition of thiol-containing enzyme systems by Sb(III) (for example, APT) (Lauwers et al., 1990; DFG, 2007; Kato et al., 2014). These processes result in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress, and the induction of peroxidase activity and apoptosis (Lecureur et al., 2002b; Kato et al., 2014).

Hashemzaei et al. (2015) observed that the antimony-induced lysis of isolated rat hepatocytes was mediated by ROS formation, lipid peroxidation and a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential. Increased oxidative stress was also observed in the liver of mice and rats treated with Sb(V) antimonials (for example, meglumine antimoniate) (Dzamitika et al., 2006; Frezard et al., 2009; Bento et al., 2013). The acute treatment of mice with meglumine antimoniate also induced oxidative stress as evidenced by increased lipoperoxidation and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in the liver. An imbalance between SOD and catalase activities in heart, liver, spleen and brain tissue was also reported (Bento et al., 2013).

Finally, the cytotoxicity of APT, as evidenced by APT induced apoptosis, was observed in various lymphoid cell lines, including the HL60 acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. There was also an association between the underlying apoptosis and increased cellular production of ROS, as well as loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Lecureur et al., 2002a, 2002b). Increased levels of ROS and deleterious effects on mitochondria by ATO were also reported (NTP, 2018).

Wan et al. (2021) investigated the nephrotoxicity induced by arsenic and/or antimony exposure via the induction of autophagy and pyroptosis in vivo and in vitro. In vivo, mice were dosed with 4 mg/kg arsenic trioxide or/and 15 mg/kg antimony trichloride by intragastric intubation for 60 days. In vitro, renal tubular epithelial (TCMK-1) cells were treated with arsenic trioxide (12.5 μM) and/or antimony trichloride (25 μM) for 24 hours. The in vivo results showed the potential for arsenic and/or antimony exposure to induce histopathological changes in the kidneys as indicated by elevated levels of creatinine and carbamine (which serve as indicators of nephrotoxicity). Additionally, arsenic and/or antimony exposure induced oxidative stress activating autophagy and pyroptosis processes (2 types of programmed cell death) via increasing/decreasing anti-autophagy/pyroptosis gene expression. In vitro, arsenic and/or antimony increased reactive oxygen species generation and decreased mitochondrial membrane potential in TCMK cells.

Selected key study

The adverse health effects of antimony have been evaluated in several subchronic studies with rats and mice. The available data from humans are not suitable for deriving a health-based value (HBV) due to study weaknesses including the route of administration of antimony (that is, intravenous and intramuscular injection) as well as exposure to high doses via poisoning events or therapeutic applications of antimony-based drugs. Thus, animal data are considered the most appropriate for risk assessment.

For the derivation of a HBV for drinking water, the study by Poon et al. (1998) is chosen as the critical study because it used an adequate number of animals, administered antimony by drinking water over multiple doses, assessed numerous health outcomes and reports the lowest NOAEL in the animal toxicity database. Sprague-Dawley rats (15/sex/dose) were given 0, 0.5, 5, 50 and 500 ppm APT (0.06, 0.56, 5.58, 42.17 mg Sb/kg bw per day males; 0.06, 0.64, 6.13, 45.69 mg Sb/kg bw per day females) in drinking water for 13 weeks. Ten additional animals per sex were included in each of the control and the highest dose groups and were given tap water for a further 4-week recovery period.

The authors observed no mortalities or clinical signs of toxicity and several of the observed histological changes in the internal organs assessed were considered as adaptive. Histological changes observed in the liver were anisokaryosis (that is, variation in size and shape) and hyperchromicity (increased optical density) of the liver nuclei, as well as increased portal density and perivenous homogeneity in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Anisokaryosis occurred with a dose-related increased incidence and severity in both sexes with persistence observed through the recovery period in the high dose animals indicating that these effects were not readily reversible. According to the authors, all of the high dose group animals had a moderate severity of anisokaryosis and most animals in the lower dose groups showed low to minimal severity of anisokaryosis. Hyperchromicity was observed in the high-dose males which also persisted through the recovery period. Increased hepatocyte portal density and perivenous homogeneity was observed in all treated rats (which persisted through recovery) but were considered adaptive and were less prominent in females. Other reported effects include:

- mild histological changes in the thyroid observed in all treated animals progressing in severity with increasing dose

- dose-related decreases in serum glucose in females starting in the second lowest dose group with statistical significance reached in the highest dose group

- decreased red blood cell and platelet counts with increased mean corpuscular volume in the high dose males

- dose-related accumulation of antimony in red blood cells starting in the second lowest dose group animals and

- dose-related increased accumulation of antimony in the spleen starting in the lowest dose group with persistence in the high dose group animals through recovery

Poon and colleagues identified a NOAEL of 0.06 mg/kg bw per day based on histological changes in the liver and thyroid, biochemical changes (namely decreased serum glucose levels in females), and accumulation of antimony in red blood cells and the spleen.

In a review of the Poon et al. (1998) study by Lynch et al. (1999), Lynch and colleagues conclude that the observed histological effects in the liver were not necessarily indicative of overt toxicity and thus proposed an alternative NOAEL of 6 mg Sb/kg bw per day. Poon and colleagues, however, responded in a later publication indicating that while the liver histological changes were considered as adaptive, these effects should be considered along with the changes in serum biochemistry, which together indicate a change in liver function (Valli et al., 2000). In conclusion, Poon and colleagues maintain that the identified NOAEL of 0.06 mg Sb/kg bw per day is appropriate.

Other recent assessments by OEHHA (2016) and ATSDR (2019) have also used data from Poon et al. (1998) for developing their health advice on antimony. In developing the public health goal for antimony in drinking water, the OEHHA (2016) identified liver anisokaryosis in males as the key health endpoint for risk assessment and derived a point of departure (POD) of 0.14 mg Sb/kg bw per day (10% benchmark dose level, BMDL10) for the basis of the public health goal. OEHHA indicates that the choice of the key health endpoint is supported by evidence of liver damage in humans exposed to antimony for the treatment of leishmaniasis and in animals in repeated dose studies, and that liver anisokaryosis has been documented as a toxic response following exposure to other xenobiotic compounds such as hydroquinone and toxaphene. ATSDR (2019), in developing its intermediate minimal risk level for antimony, also used the NOAEL of 0.06 mg/kg bw per day as identified by Poon et al. (1998), however, based on changes in serum glucose levels which ATSDR identifies as one of the most sensitive health endpoints in the animal toxicity database.

Under the Chemicals Management Plan, the risks to human health and the environment posed by a group of 11 antimony-containing substances have been previously evaluated (ECCC and Health Canada, 2020). Using a screening assessment approach, a POD of 49 mg Sb/kg bw per day for fetal skeletal effects reported by ECHA (2014) was used for characterizing the risks associated with exposure to antimony-containing substances from environmental media, food, drinking water and consumer products. The ECHA (2014) study administered a less soluble form of antimony (sodium hexahydroxoantimonate) via gavage yielding a higher POD than that identified by Poon et al. (1988) which administered APT via drinking water. ECCC and Health Canada (2020) did not consider studies administering APT or antimony trichloride for risk characterization since it was deemed that exposure to these forms of antimony from environmental media, food, drinking water and consumer products is not anticipated.

For the derivation of a HBV for antimony in drinking water, a POD of 0.06 mg Sb/kg bw per day from Poon et al. (1998) for changes in liver histology (anisokaryosis) along with the changes in serum biochemistry (which together are indicative of a change in liver function) is chosen. The choice of liver impacts as the key health endpoint is supported by evidence of liver damage in humans exposed to antimony during the treatment of leishmaniasis, and in animal repeated dose studies. Since the form of antimony used in the Poon et al. (1998) study (APT) is more soluble than other forms of antimony that may be present in drinking water, the HBV is expected to be protective of all forms of antimony in drinking water.

Derivation of the health-based value (HBV)

A NOAEL of 0.06 mg Sb/kg bw per day based on histopathological changes (anisokaryosis) in the liver and changes in serum biochemistry that are indicative of liver effects, as reported by Poon et al. (1998), is chosen as the POD for deriving the HBV for antimony in drinking water.

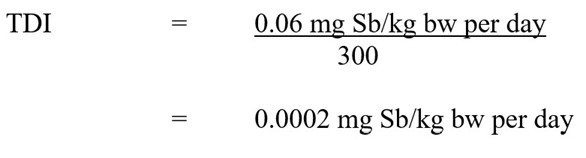

Using the NOAEL of 0.06 mg Sb/kg bw per day, a tolerable daily intake (TDI) for total antimony is calculated as follows:

Figure 1 - Text description

The tolerable daily intake (TDI) of antimony is 0.0002 mg Sb/kg body weight per day. This is calculated by dividing the NOAEL of 0.06 mg Sb/kg body weight per day by the uncertainty factor of 300.

where:

- 0.06 mg Sb/kg bw per day is the NOAEL identified from Poon et al. (1998), based on histopathological changes (anisokaryosis) in the liver and changes in serum biochemistry indicative of liver effects and

- 300 is the uncertainty factor, accounting for interspecies variation (×10), intraspecies variation (×10), and the use of a subchronic study (×3)

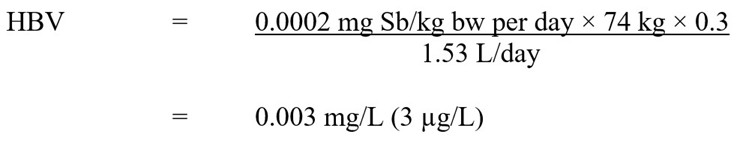

Using this TDI, the HBV for total antimony in drinking water is derived as follows:

Figure 2 - Text description

The health-based value (HBV) for antimony in drinking water is 0.003 mg/L. This is calculated by multiplying the antimony TDI of 0.0002 mg Sb/kg body weight per day by the average adult body weight of 74 kg by the allocation factor for drinking water of 0.3. The result is divided by 1.53 L/day, which is the drinking water intake rate for an adult.

where:

- 0.0002 mg Sb/kg bw per day is the TDI derived above

- 74 kg is the average body weight for an adult (Health Canada, in preparation)

- 0.3 is the drinking water allocation factor based on the upper bound of the estimated intake for drinking water (refer to the section on exposure)

- 1.53 L/day is the drinking water intake rate for a Canadian adult (Health Canada, in preparation)

- Due to its low volatility and low dermal absorption (OEHHA, 2016), exposure to antimony from showering or bathing is unlikely to be significant. Consequently, a multi-route exposure assessment, as outlined by Krishnan and Carrier (2008), was not performed.