Draft Guidance on asbestos in drinking water

Document for public comment

Consultation period ends: March 24, 2026

Download in PDF format

(777 KB, 64 pages)

Purpose of consultation

This document has been developed with the intent to provide regulatory authorities and decision-makers with guidance on asbestos in Canadian drinking water supplies.

This document is available for a 60-day consultation period. Please send comments (with rationale, where required) to Health Canada via email to: water-consultations-eau@hc-sc.gc.ca

All comments must be received before March 24, 2026. Comments received as part of this consultation will be shared with members of the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water (CDW), along with the name and affiliation of their author. Authors who do not want their name and affiliation to be shared with CDW should provide a statement to this effect along with their comments.

It should be noted that this guidance document on asbestos will be revised following evaluation of comments received, and a final guidance document will be posted. This document should be considered as a draft for comment only.

Background on guidance document

The main responsibility of the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water (CDW) is to work in collaboration with Health Canada to develop and update the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality (GCDWQ). This role has evolved over the years, and Health Canada and the CDW also develop guidance documents. Guidance documents provide advice on issues related to drinking water quality for substances that do not require a formal Guideline for Canadian Drinking Water Quality.

There are two reasons for which Health Canada, in collaboration with the CDW, may choose to develop guidance documents. The first would be to provide operational or management guidance related to specific drinking water-related issues (such as boil water advisories or corrosion control), in which case the document would provide only limited scientific information or a health risk assessment.

The second reason would be to make risk assessment information available when a guideline is not deemed necessary. Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality are developed specifically for substances that meet all of the following criteria:

- exposure to the substance could lead to adverse health effects

- the substance is frequently detected or could be expected to be found in a large number of drinking water supplies throughout Canada

- the substance is detected, or could be expected to be detected, at a level that is of possible health significance

If a substance of interest does not meet all these criteria, Health Canada, in collaboration with the CDW, may choose not to establish a numerical guideline or develop a guideline technical document. In that case, a guidance document may be developed.

Guidance documents undergo a similar process as guideline technical documents, including public consultations through the Health Canada website. They are offered as information for drinking water authorities, and in some cases to help provide guidance in spill or other emergency situations.

Executive summary

Asbestos can enter drinking water through natural sources (erosion and runoff from soil and rock), emissions from human activities (such as mining), and releases from aging asbestos-cement (A-C) pipes in drinking water distribution systems. Asbestos fibres have no detectable odour or taste, and they do not dissolve in water or evaporate. Canadian data are limited but indicate that there was no asbestos detected in most samples. A maximum acceptable concentration (MAC) for asbestos in drinking water is not recommended since there is no consistent, convincing evidence that oral exposure to asbestos causes adverse effects in humans and animals.

Given public concern with asbestos and the goal of minimizing particle loading in treated drinking water to effectively operate the distribution system, it is recommended to implement best practices to minimize the concentrations of asbestos fibres in drinking water. Monitoring for asbestos can help provide a condition assessment of A-C pipes and inform infrastructure replacement schedules.

Health Canada has completed its review of asbestos in drinking water. This guidance document was prepared in collaboration with the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water (CDW) and assesses the available information on asbestos in the context of exposure from drinking water.

Assessment

The health effects of asbestos related to inhalation exposure are well established and extensively researched. In contrast, oral exposure studies have not clearly demonstrated adverse health outcomes when considering the weight of evidence and the strength of the available studies. This guidance document provides an assessment of the available human and animal studies involving oral exposure to asbestos in drinking water.

The toxicity of asbestos is influenced by many factors including duration and frequency of exposure, tissue-specific dose over time, persistence of the fibres in the tissue (influenced by the absorption, distribution and clearance of fibres), individual susceptibility, and, most importantly, the type and size of the fibres. Another factor influencing toxicity is the physiology of the digestive tract. Stomach acidity aids in the degradation of certain asbestos fibres (chrysotile) to smaller, less toxic fibres, while the intestinal mucosal barrier and cellular tight junctions limit the penetration and uptake of fibres. Studies in animals and humans report that nearly all of the ingested asbestos fibres (greater than 99%) pass through the digestive system and are excreted within 48 hours. Furthermore, the few fibres that do cross the intestinal barrier are generally less than 1 µm in length, a size that is not considered to be carcinogenic.

Standardized methods are available for the analysis of asbestos in source and drinking water. However, there are no accredited laboratories conducting asbestos analysis in drinking water in Canada.

At the municipal scale, conventional coagulation and filtration treatment can effectively remove asbestos fibres from source water. More than 99% of asbestos fibres can be removed by optimizing coagulation and filtration processes. At the residential and small scale, there are certified drinking water treatment devices capable of removing asbestos fibres from drinking water. The technologies certified to the NSF standards include carbon-based filters and reverse osmosis (RO) systems.

Water mains can be composed of A-C. Most A-C mains were installed many decades ago (from the 1940s until the late 1970s, with the use of products containing asbestos prohibited in Canada in 2018) and are at or near the end of their useful life span. The existing A-C mains eventually deteriorate, and the erosion of the pipe material can lead to the release of asbestos fibres, loss of mechanical stability and possibly pipe failure. Corrosion, or dissolution, as well as flow rate (low or high) and water quality (such as low pH, soft water and high sulphate) conditions impact the integrity of A-C pipes and can also lead to the release of asbestos fibres.

A MAC for asbestos in drinking water is not recommended since there is no consistent, convincing evidence that oral exposure to asbestos causes adverse effects in humans and animals. Due to significant limitations in study design and the absence of clear health outcomes, the available data on oral exposure to asbestos are insufficient for deriving a health-based value. Furthermore, asbestos fibres present in drinking water are generally smaller than those considered to be of concern for human health and greater than 99% of fibres in drinking water are excreted following ingestion.

Part A. Guidance on asbestos in drinking water supplies

A.1 Scope and aim

The intent of this document is to provide guidance on the health considerations for exposure to asbestos from drinking water. This document provides information on how people in Canada are exposed to asbestos in drinking water and summarizes the current available health data from human and animal oral ingestion studies. It outlines treatment strategies to remove naturally occurring asbestos. Management strategies to evaluate the release of asbestos fibres from asbestos-cement (A-C) pipes and assess potential exposure, the loss of mechanical stability in these pipes as well as the potential for pipe failure are also addressed in this document.

A.2 Application

A.2.1 Introduction

Asbestos refers to a family of six naturally occurring fibrous silicate minerals falling into either the serpentine or amphibole groups, based on their physical and chemical properties. Chrysotile, the only member of the serpentine group, has fibres that are flexible and curved. Crocidolite, amosite, actinolite, anthophyllite and tremolite are members of the amphibole group that have stiff and straight fibres. Asbestos fibres have no detectable odour or taste, do not dissolve in water and are non-volatile.

People in Canada can be exposed to asbestos mainly from drinking water and air. Asbestos can enter drinking water sources by erosion and runoff from natural deposits in soil and rock in some geological areas or by emissions from human activities. Asbestos fibres can also be present in drinking water as a post-treatment contaminant from degrading A-C water distribution pipes or from disintegrating asbestos roofing materials when rainwater is collected into cisterns. Ambient outdoor air can contain small quantities of asbestos fibres, with urban areas or locations near industrial sources having higher concentrations than rural areas. Indoor air can also contain low levels of asbestos. Historically, the most significant exposures to asbestos have come from chronic inhalation in occupational settings, such as in the mining and milling of asbestos minerals, the manufacture of products containing asbestos, construction and automotive industries and the asbestos-removal industry. Asbestos fibres may be present in foods through contamination with soil particles, dust or other dirt containing asbestos fibres. However, the presence of asbestos fibres in foods has not been well studied.

A.2.2 Health considerations

The toxicity of asbestos fibres is influenced by many factors, including duration and frequency of exposure, tissue-specific dose over time, persistence of the fibres in the tissue (influenced by the absorption, distribution and clearance of fibres), individual susceptibility, and the type and size of the fibres. Fibre size is the most important determinant of carcinogenicity, where fibres longer than 5 µm and thinner than 0.25 µm have been shown to be more toxic. Another factor influencing toxicity is the physiology of the digestive tract. Stomach acidity aids in the degradation of certain asbestos fibres (chrysotile) to smaller, less toxic fibres, while the intestinal mucosal barrier and cellular tight junctions limit penetration and uptake of fibres. Studies in animals and humans report that nearly all of the ingested asbestos fibres (greater than 99%) pass through the digestive system and are excreted within 48 hours. Furthermore, the few fibres that do cross the intestinal barrier are generally less than 1 µm in length, a size that is not considered to be carcinogenic.

The health hazards associated with inhaled asbestos are well known. Asbestos is a known carcinogen through the inhalation route, causing mesothelioma and other cancers, including lung, laryngeal and ovarian. Inhalation exposure in occupational settings has also been associated with colorectal, stomach and pharyngeal cancers. Oral exposure to asbestos, however, has not been clearly shown to cause adverse effects in humans and animals. Overall, human and animal oral exposure data are insufficient to support a dose-response analysis and the determination of a point of departure for non-cancer or cancer health outcomes due to significant limitations in the design of all available studies as well as an absence of clear health outcomes. In addition, given the physiological differences between the lungs and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which affect the retention and absorption of fibres, extrapolation from inhalation to oral exposure is not recommended.

A.2.3 Management considerations

A maximum acceptable concentration (MAC) for asbestos in drinking water is not recommended for the following reasons:

- the available data on oral exposure to asbestos in both humans and animals are insufficient for deriving a health-based value (HBV) in drinking water due to significant limitations in study design and an absence of clear health outcomes

- historical data indicate that asbestos fibres present in drinking water are generally smaller (less than 1 µm) than those typically associated with adverse health effects in humans

- after ingestion, small fibers present in drinking water are further degraded in the stomach and are largely excreted, since the GI tract serves as an effective barrier to their absorption

As part of its ongoing drinking water guideline/guidance review process, Health Canada will continue to monitor new research on the health outcomes associated with oral exposure to asbestos and recommend any change(s) to this guidance that it deems necessary.

A.2.3.1 Analytical and treatment

Three standardized methods are available for the quantification of asbestos in source and drinking water, based primarily on transmission electron microscopy. However, there are no accredited laboratories conducting asbestos analysis in drinking water in Canada.

At the municipal scale, conventional coagulation and filtration treatment can effectively remove asbestos fibres from source water. Greater than 99% of asbestos fibres can be removed by optimizing coagulation and filtration processes. At the residential and small scale, there are certified drinking water treatment devices capable of removing asbestos fibres from drinking water. The technologies certified to the NSF standards include carbon-based filters and reverse osmosis (RO) systems.

A.2.3.2 Factors affecting A-C pipes

A-C water mains can deteriorate, and the erosion of the pipe material can lead to the release of asbestos fibres, loss of mechanical stability and possibly pipe failure. Corrosion, or dissolution, of A-C pipes is governed by solubility considerations such as soft distributed water (for example, water with low mineral content) and pH levels below 7.5. Very high sulphate and polyphosphate concentrations are especially corrosive to A-C pipes. Pipes experiencing low flow conditions or long residence times can also lead to their deterioration. However, high water flows from main flushing can also lead to high asbestos fibre concentrations in the distributed water due to the mobilization of fibres in dead ends or shear forces on deteriorated A-C pipes.

A.2.3.3 Management strategies

Although a MAC is not recommended, given public concern with asbestos and the goal of minimizing particle loading in treated drinking water to effectively operate the distribution system, it is recommended to implement best practices to minimize the concentrations of asbestos fibres in drinking water. In water sources with high asbestos fibres concentrations, conventional water treatment can be implemented and optimized for asbestos fibre removal. Non-treatment options such as alternative water supplies can also be considered. Where aging A-C pipes are in use, degradation and release of fibres into drinking water should be minimized by controlling water corrosivity or by coating A-C pipes with suitable structural linings.

As A-C pipes reach the end of their useful lifespan and begin to fail or deteriorate significantly, they should be replaced with new asbestos-free materials. The use of products containing asbestos has been prohibited in Canada since 2018. Water treatment facilities may consider monitoring to investigate the presence and contribution of older A-C pipes to numbers, types, size and shape of fibres in drinking water (WHO, 2021). Information from the monitoring of asbestos fibres in drinking water can inform decisions about infrastructure replacement plans as well as support communication with consumers about water quality.

If the effectiveness of asbestos removal is to be assessed, paired samples of source and treated water should be collected to confirm the efficacy of treatment. Measurements of asbestos fibre concentrations obtained from hydrant mains samples in conjunction with water quality results can provide an indication of the integrity and condition of A-C pipes. Structural integrity of water mains can be monitored using destructive and non-destructive testing as well as predictive models based on historical data. Detailed information on management strategies and the monitoring of asbestos fibres and A-C pipe deterioration are found in Part B.5.

Part B. Supporting information

B.1 Exposure considerations

B.1.1 Identity, use, sources and environmental fate

Asbestos (Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number [CAS RN] 1332-21-4) is the generic name for a family of six naturally occurring fibrous silicate minerals that have been used commercially. These fibrous minerals are composed of sheets or chains of fibres that have the silicate tetrahedron (SiO4) as the basic chemical unit, which can be associated with other chemical elements such as magnesium, calcium, aluminum, iron, potassium or sodium. Asbestos fibres are classified into two groups based on their physical and chemical properties: serpentine and amphibole. The serpentine group consists of only one member, chrysotile. Chrysotile is a magnesium silicate with thin and flexible fibres arranged in sheets that curl in a spiral manner. Chrysotile (CAS RN 12001-29-5) has a net positive surface charge, forms a stable suspension in water and degrades in weak acids but is largely resistant to alkali. The amphibole group (crocidolite, amosite, actinolite, anthophyllite and tremolite), however, have stiff, straight, needle-like fibres that do not dissolve, are resistant to acid and have a negative surface charge.

Asbestos fibres have no detectable odour or taste, are not soluble in water, nor do they evaporate. Asbestos-containing minerals occur as organized bundles of parallel fibres that can be separated into thinner strands. The length of fibre bundles can vary from several millimetres to more than 10 cm in length (IPCS, 1986; ATSDR, 2001; Virta, 2011; IARC, 2012). The Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (Canada Labour Code, 1986) defines an asbestos fibre as a particle having a length of greater than 5 µm and an aspect ratio (length to width) equal or greater than 3:1.

Asbestos minerals have been historically used for numerous industrial applications because of their strong, long-lasting properties that are resistant to fire, heat and chemicals. They are also resistant to biodegradation and exhibit low electrical conductivity. Asbestos has been used in construction products (cement and plaster, building insulation, floor and ceiling tiles, house siding), friction materials (car and truck brake pads and transmission components), and anti-fire/heat applications (protective wear, heat, sound and electrical insulation, packing materials) (ATDSR, 2001; IARC, 2012). In Canada, the Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations (2018) under the authority of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) (1999), prohibit the import, sale, and use of asbestos, as well as the manufacture, import, sale and use of products containing asbestos, with some exceptions. Legacy asbestos materials are still present in older buildings and other products and are gradually being replaced with substitute materials or alternative products. Asbestos that is undisturbed or sealed to prevent release into environmental media are not considered a concern to health (ATDSR, 2001; IARC, 2012).

Asbestos fibres in water can come from natural sources, such as soil and rock, or from anthropogenic sources. Mineral fibres may be released into surface water by erosion and runoff of natural deposits and waste piles. They naturally settle out of air and water to deposit in soil or sediment. Fibre migration depends on a variety of factors including site and geographical characteristics in combination with key physico-chemical characteristics such as particle size and morphology, solubility and surface charge (ATDSR, 2001; IARC, 2012). Small fibres (0.1 to 1 µm) can stay suspended in air and water, allowing them to be transported over long distances. Following release into the environment, asbestos degrades very slowly, with leaching of minerals from the fibre surface or breakdown into shorter lengths (U.S. EPA, 2018).

Asbestos fibres can also be present in drinking water from deterioration of A-C water mains or from disintegrating asbestos roofing materials when rainwater is collected into cisterns (ATDSR, 2001; IARC, 2012). In North America, A-C was commonly used for the construction of potable water mains starting in the 1940s. Its use was discontinued in the late 1970s due to health concerns associated with the manufacturing process and it was estimated that A-C pipes made up 16% to 18% of water distribution pipes in the United States (U.S.) and Canada (Hu et al., 2008). Data from the Core Public Infrastructure Survey published by Statistics Canada indicate that in 2022, less than 14,000 km of A-C pipe were in use in Canadian drinking water distribution systems (see Appendix A, Table A1). This accounts for approximately 6% of the total length (in km) of all types of water pipes in use across Canada (Statistics Canada, 2025).

A-C is made out of Portland cement, with or without silica, mixed with asbestos fibres (Hu et al., 2008). Portland cement contains calcium silicates, calcium aluminates, iron calcium aluminates and gypsum (Leroy et al., 1996). Asbestos fibres are the aggregate materials that provide stress and pressure resistance and represent about 20% of the pipe by weight (Hu et al., 2008; Leroy et al., 1996). Chrysotile and crocidolite are the two types of asbestos fibres that were used in A-C pipes (Hu et al., 2008), with chrysotile asbestos being the main one used in North America (Cook et al., 1974).

The shedding of fibres from these distribution pipes occurs due to many factors. These include the physical characteristics of the piping (age, size, quality of manufacturing) and the local environment (season, temperature of the water, pH and other water chemistry parameters). A-C pipe degradation is associated with low pH, low alkalinity, increased age, and the presence of any internal pipe coatings. The primary cause of fibre release into drinking water is pipe softening due to calcium leaching from the A-C material as it degrades (Zavasnik et al., 2022).

Natural erosion is another potential source of asbestos fibres. In natural waters, Webber and Covey (1991) reported that levels are generally less than 1 million fibres per litre (MFL). However, in certain regions, like eastern North America, high concentrations of chrysotile have been measured in surface waters in areas of serpentinized bedrock. A study by Monaro et al. (1983) reported concentrations of 1 MFL as part of an investigation to assess the influence of mining on asbestos pollution of the Bécancour river in Quebec. In the analysis of 1 500 water samples in the U.S., chrysotile asbestos was the most commonly found, though some samples contained amphibole asbestos (Millette et al., 1980). The study also suggested that the size distribution of the fibres depends on their source. For example, fibres released from A-C pipes tended to be longer than those resulting from natural erosion, averaging approximately 4 µm and 1 µm, respectively.

B.1.2 Exposure

People in Canada can be exposed to asbestos mainly from drinking water and air. Exposure from drinking water is expected to occur primarily from the oral route. Asbestos fibres are non-volatile. However, they have been shown to transfer to air by aerosolization at very low concentrations. It is possible that inhalation exposure to aerosolized asbestos could occur during showering and bathing with water containing high concentrations of fibres. Since asbestos fibres in drinking water have been shown to be smaller than those considered to be a health concern (less than 1 µm in length, see section B.2.6), adverse health outcomes from this exposure are not expected. Additionally, asbestos fibres are not able to pass through skin; thus, skin contact with asbestos fibres in drinking water is not an expected route of exposure.

B.1.2.1 Water

Limited water monitoring data was available from the provinces and territories (PTs) for the concentration of asbestos fibres in drinking water. Data was obtained from Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. Other PTs as well as the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) did not have any information on the concentration of asbestos fibres in drinking water or in source water (Indigenous Services Canada, 2023; Manitoba Department of Environment and Climate, 2023; Ministère de l'Environnement, de la Lutte contre les changements climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec, 2023; New Brunswick Department of Environment and Local Government, 2023; Northwest Territories Department of Health and Social Services, 2023; Nova Scotia Environment, 2023; Nunavut Department of Health, 2023; Ontario Ministry of the Environment, 2023; Prince Edward Island Department of Environment, 2023). The detection limit used in the analysis of asbestos is defined as the analytical sensitivity (AS).

Overall, the limited data received from the PTs demonstrated a very low detection frequency of asbestos fibres in drinking water. This indicates that either the samples had no detectable asbestos fibres or that concentrations were below the AS. When there is less than 10% detection, the 90th percentile is presented as being below the AS. The range of ASs, number of detects, number of samples, 90th percentile asbestos concentration and maximum asbestos fibres concentration are presented in Table 1 for the provincial data. Overall, for asbestos fibres concentration, the dataset showed that:

- most of the samples were below the AS

- limited information is available concerning asbestos fibre concentration in raw, treated and distributed water.

| Jurisdiction

(AS MFL) |

Water type | No. detects/ samples |

Median (MFL) |

Mean (MFL) |

90th percentile (MFL) |

Max (MFL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador Footnote 1 (0.18–1.9) [2012–2021] |

Not specified; distribution Footnote a |

1/21 | < AS | < AS | < AS | 0.58 |

| Saskatchewan Footnote 2 (0.18–2.11) [2024–2025] |

Not specified; distribution | 0/44 | < AS | < AS | < AS | < AS |

AS – analytical sensitivity; MFL – million fibres per litre. |

||||||

In Saskatchewan, water samples were collected to determine asbestos concentrations in municipal drinking water distribution systems in areas known to have A-C pipes. A total of 102 asbestos samples were collected from 47 communities from November 2024 to February 2025. Samples were collected under both normal operating conditions (n = 95) and following A-C pipe break and repair conditions (n = 7). As noted in Table 1, no asbestos fibres were detected in any of the distribution system water samples.

In British Columbia, testing has been conducted by health authorities. Data from one health authority had values mainly below the AS. One water treatment facility that was conducting regular testing (number of samples and testing frequency were not provided) also found all values were below the AS (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2023).

Additional data were obtained for a small number of water treatment facilities, either through direct communication or in online versions of reports. These are summarized in Table 2. In each case, the facilities reported that the concentrations of asbestos fibres, quantified using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA's) EPA Method 100.2, were below the ASs. The City of Regina, SK sampled water from one location in their distribution system annually from 2016 to 2019. They subsequently increased the sampling to 11 locations from 2020 to 2022. The locations selected were connected to A-C water mains that were installed between 1956 and 1987. The analytical method used in Regina only considers fibres that are greater than 10 µm in length (City of Regina, 2023). The City of Medicine Hat, AB estimated that, in 2022, 32% of underground pipes were A-C pipes (City of Medicine Hat, 2023), and no detectable levels of asbestos fibres were measured in six water samples (ALS Laboratory Group, 2023). Water samples were collected in 2018 and 2023 to evaluate the concentration of asbestos in water in Edmonton, Alberta. Fourteen samples were collected in 2018 (two sources, two treated, and 10 distributed water samples) and 2023 (two treated and 12 distributed water samples). The sampling locations in the distribution system were selected from areas known to have A-C pipes and low water flow/high water age. No asbestos was detected in any sample in both studies (EPCOR, 2018; 2024).

| Jurisdiction (AS MFL) [year sampled] |

Water type | No. detects/ samples |

90th percentile (MFL) |

Max (MFL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regina, Saskatchewan Footnote 1 (0.16 to 0.17) [2016 to 2022] |

Surface; distribution | 0/37 | < AS | < AS |

| Guelph, Ontario Footnote 2 (0.18) [2023] |

Ground; ground/raw | 0/1 | NC | < AS |

| Medicine Hat, Alberta Footnote 3 (0.18) [2023] |

Surface; distribution | 0/6 | NC | < AS |

| Edmonton, Alberta Footnote 4 (0.17) [2018] |

Surface; distribution | 0/14 | NC | < AS |

| Edmonton, Alberta Footnote 5 (0.145) (rounded) [2023] |

Surface; distribution | 0/14 | NC | < AS |

AS – analytical sensitivity; MFL – million fibres per litre; NC – not calculated. |

||||

Historical concentrations of asbestos fibres in Canadian drinking water are reported elsewhere (Bacon et al., 1986; Chatfield and Dillon, 1979; Cunningham and Pontefract, 1971; Toft et al., 1981; Wigle, 1977; Wigle et al., 1986). These concentrations are unlikely to be representative of the current situation as these publications are decades old and the characteristics of the drinking water distribution systems may have changed. Also, sources of asbestos fibres in drinking water distribution systems (that is, the A-C pipes) may have been removed. Sample preparation methods and analysis also differ from current approved methods since the studies took place prior to the establishment of the EPA methods and American Public Health Association (APHA) Standard Method (SM). In discussing sizing of asbestos fibres in these studies, differences in sensitivities can be observed between studies that also influence the results (Millette et al., 1983).

Samples from raw, treated and distributed water were collected in 71 Canadian municipalities during August and September 1977 (Toft et al., 1981). The study by Toft et al. (1981) is based on a national survey published by Chatfield and Dillon (1979). Analytical methods used were similar to EPA Method 100.1 (Chatfield et al., 1978). Chrysotile asbestos was the major type of asbestos found in drinking water, whereas amphibole asbestos was not significant with detectable levels found in 7% of samples (Chatfield and Dillon, 1979; Toft et al., 1981). This study found that 5% of water supplies contained asbestos at concentrations greater than 10 MFL. Concentrations of asbestos fibres were also significantly higher in samples collected from a distribution system than in treated water samples (Toft et al., 1981). In cases where the asbestos concentration was greater than 5 MFL in the distribution water, the median fibre lengths were between 0.5 and 0.8 µm (Toft et al., 1981).

Concentrations of asbestos fibres were measured in the tap water of eight cities located in Quebec and Ontario and one river sample in Ontario. It was found that fibres in most filtered tap waters were less than 1 µm in length. Where water was treated in a municipal drinking water treatment plant (DWTP), concentrations of asbestos fibres in the tap water ranged between 2.0 MFL and 5.9 MFL. The highest concentration was attributed to the source water being located in a small lake within an asbestos mining area (Cunningham and Pontefract, 1971).

Concentrations of asbestos fibres were quantified in southeastern Quebec (the drainage basins of the Richelieu, Yamaska, Magog, Missisquoi [north branch] and Sutton Rivers) where the source water was impacted by asbestos-bearing railway ballast and naturally occurring asbestos deposits (Bacon et al., 1986). No samples from treated drinking water were collected during this study. Detectable levels of asbestos fibres were found in all the source water samples. For groundwater samples (four sampling locations), concentrations ranged between 2.2 MFL and 23.0 MFL. For surface water samples (14 sampling locations), concentrations ranged between 0.6 MFL and 147.8 MFL (Bacon et al., 1986).

Four communities in Quebec (Asbestos, Drummondville, Plessisville and Thetford Mines) either adjacent to asbestos deposits or using rivers that drain from regions with asbestos deposits as their drinking water source were sampled by Wigle (1977). In the four raw water samples, the concentrations varied considerably, with one sample containing 13 MFL while the other three samples ranged between 680 and 1 300 MFL.

In Christchurch, New Zealand, an average of 0.9 MFL was measured for asbestos fibres > 10 µm in length while shorter fibres (> 0.5 µm in length) had an average concentration of 6.2 MFL in 20 samples. Samples were collected at hydrants and were representative of water mains. Household tap samples were also collected and the authors found that long chrysotile fibres were detected in three of 15 household tap samples, averaging 0.3 MFL. Short asbestos fibres were also detected in these same locations, but concentrations were considerably higher with an average of 3.5 MFL. Additional household samples were obtained to determine if results at the tap reflected distribution system samples. However, only two hydrants were able to be paired as a direct supply to household taps. In one set of hydrant samples, concentrations of 1 MFL for short fibres were detected in the hydrant samples, but no fibres were detected in the samples collected from household taps. In the second paired samples, concentrations from the hydrant and at household taps were 4.1 MFL and 2.2 MFL, respectively. The occurrence of positive, high-fibre counts in hydrant samples was significantly greater than observed in household tap samples (Mager et al., 2022). Although tap sampling may inform exposure, the limited results indicate that it may not inform the state of A-C pipe deterioration as well as hydrant sampling.

In the U.S., the typical concentration of asbestos measured in drinking water is less than 1 000 fibres/L, even in areas with asbestos deposits or A-C water supply pipes—although very high concentrations have also been reported (10 to 300 MFL or more) (IARC, 2012). Measured asbestos levels in U.S. drinking water from 2006 to 2011 were reported to range from 0.10 to 6.8 MFL (5th and 95th percentiles, respectively) (U.S. EPA, 2016). Water samples were collected from 538 A-C water distribution systems, located throughout the ten U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regions. Results showed that the average length of chrysotile fibres found in was less that 5 µm (Millette et al., 1980; 1983).

Although asbestos fibres are non-volatile, they have been found in water aerosols generated from contaminated drinking water. Roccaro and Vagliasindi (2018) investigated the release of asbestos fibres from a portable home humidifier and shower. The humidifier was filled with groundwater containing 24 687 asbestos fibres/L. Air samples were found to contain fibres longer than 5 µm with a width less than 3 µm and with a length-to-width ratio greater than 3:1. The authors reported that 0.04% to 0.07% of fibres were transferred from the humidifier to the air. For the shower, the authors reported a transfer of 4.3% to 10.8% of fibres from tap water containing natural levels of 8 229 fibres/L. An earlier study by Hardy et al. (1992) determined a similar release of asbestos-like fibres from a room humidifier where 0.03% to 4.7% of fibres from the water (57 to 280 000 million asbestos structures/L) used to fill the humidifier were transferred to the air. In a controlled experiment designed to simulate the migration of asbestos fibres from water to air during the collapse of bubbles and foams from polluted natural waters, Avataneo et al. (2022) reported that the minimum waterborne asbestos fibre concentration required to release at least one fibre/L (the alarm threshold limit set by the World Health Organization [WHO] for airborne asbestos) into the air is 40 MFL. Avataneo et al. (2022) indicated that the higher migration of fibres in the studies by Hardy et al. (1992) and Roccaro and Vagliasindi (2018) may be due in part to a more effective system to generate fibre migration to air (humidifier/showering versus bubbling), differences in fibre sizes and lower relative humidity in these studies compared to the bubbling study (Avataneo, 2022).

B.1.2.2 Air

Inhalation is the primary route of exposure to asbestos. Ambient outdoor air contains small and highly variable quantities of asbestos fibres, with urban areas or sites in close proximity to industrial sources having higher concentrations (approximately 0.1 fibres/L) than rural locations (approximately 0.001 fibres/L) (ATSDR, 2001; IARC, 2012; U.S. EPA, 2018). Indoor air can also contain low levels of asbestos (IARC, 2012). Historically, most inhalation of asbestos has been shown to occur through chronic occupational exposure, such as in the mining and milling of asbestos minerals, the manufacture of products containing asbestos, construction and automotive industries and the asbestos removal industry (IARC, 2012). With the decline of asbestos manufacture and use, more recent occupational exposures to asbestos mainly occur in the construction industry and associated occupations (for example, carpenters, trades helpers and labourers and electricians). From 2006 to 2016, approximately 235 000 Canadian workers were reported as having been occupationally exposed to asbestos (Fenton et al., 2023).

Some inhaled asbestos fibres can collect in the air passages of the respiratory system and become deposited in the ciliated portion of the airway. These fibres are removed through mucociliary expulsion from the lungs to the throat and are then swallowed. Approximately 28% of inhaled particulate matter, including asbestos, is reportedly transported to the GI tract (Gross et al., 1974).

B.1.2.3 Food

There are no recent data for asbestos fibre levels in food or beverages. Rowe (1983) suggested that foods contaminated with soil particles, dust, or dirt may also contain asbestos fibres, and could be a significant source of exposure to ingested asbestos relative to drinking water. However, due to the lack of a simple and reliable analytical method, asbestos measurement in food has not been well studied.

B.1.3 Climate change considerations

Climate change is projected to have impacts on temperature, precipitation patterns, soil moisture and occurrence of extreme weather events (Olmstead, 2014). Temperature, moisture and precipitation are some of the climatic conditions influencing water main deterioration (Ahmad et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2008).

For example, climate change can have an impact on the moisture content of soils through severe heat waves and drought or by increasing precipitation. This can affect the shrinking and swelling of the soil, which causes stress on pipes and can lead to increases in water main failures (Ahmad et al., 2023). In particular, significant moisture content changes can occur in montmorillonitic clay soils, creating stress on buried infrastructures such as A-C pipes (Hudak et al., 1998; Hu and Hubble, 2007).

The deterioration of the outside surface of the pipe can be influenced by the groundwater and soil surrounding it (Hu et al., 2008). The aggressiveness of the soil towards A-C pipes depends on its pH and the amount of sulphate present (Hu et al., 2008). At least one climate change modelling study suggests that an increase in mean annual air temperature and annual precipitation could increase soil pH in eastern Canada (Houle et al., 2020).

B.2 Health effects

The toxicity of asbestos fibres is dependent on fibre characteristics (such as asbestos type, dimensions, fibre size, surface area and charge) and exposure considerations (such as dose, duration and route of exposure). Asbestos is a known carcinogen through inhalation exposure, causing mesothelioma and cancers of the lung, larynx and ovaries. In occupational settings, colorectal, stomach, liver and pharyngeal cancers have also been reported as being associated with inhalation exposure (IARC, 2012; Brandi and Tavolari, 2020). Non-cancer effects following inhalation exposure include fibrotic lung disease (asbestosis), pleural plaques and thickening of the pleura (ATSDR, 2001). The evidence for health effects from oral exposure in animals and humans, however, is inconsistent. This guidance document presents the available health information associated with oral exposure to asbestos fibres (largely chrysotile fibres) mainly from drinking water (epidemiological studies) and to a lesser extent food (animal studies). A weight of evidence analysis and quality assessment of the available studies has also been conducted.

B.2.1 Effects in humans

A systematic review of the available epidemiological data examined the associations between ingesting asbestos-contaminated drinking water and the risk of adverse health outcomes (Go et al., 2024). From an initial total of 7 044 references identified in the published literature, 25 references (assessing 17 studies) were retained while the rest of the studies were not relevant for risk assessment for drinking water exposure. Fourteen studies were of ecological design, two were case-control studies, and one was a cohort study. The main sources of asbestos fibres in drinking water in these studies were from A-C distribution pipes, A-C roofs from which drinking water was collected, lakes contaminated by industrial waste containing asbestos or from natural water sources. When reported, the concentration of asbestos fibres ranged from below the limit of detection to 7.1 x 103 MFL.

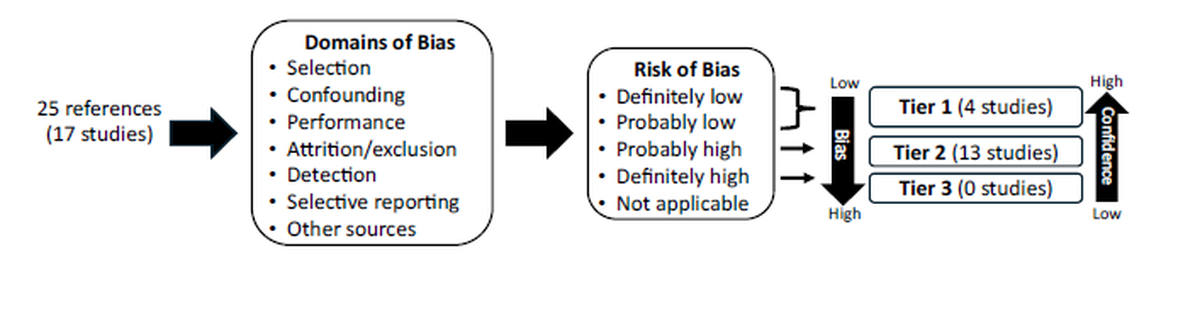

Tables 3a and 3b provide a summary of the relevant information on study design, exposure information and health outcomes reported in each of the studies retained for review. An assessment of confidence in the data from these studies was conducted using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating (ROB) Tool, developed by the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NTP, 2015). The outcome of these bias assessments were used to rank the studies into three Tiers (see Figure 1) (Go et al., 2024).

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure illustrates the assessment of confidence of 25 references that assessed 17 studies. Individual studies were assessed using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation Risk of Bias Tool.

The assessment considers the following 7 domains of bias:

- selection

- confounding

- performance

- attrition/exclusion

- detection

- selective reporting

- other sources of bias

The assessment of each study results in a risk of bias rating of:

- definitely low

- probably low

- probably high

- definitely high

- not applicable

Based on their risk of bias rating, studies are categorized into tiers:

- Tier 1 studies have a low risk of bias or probably a low risk of bias indicating the highest confidence

- Tier 2 studies have a probable high risk of bias indicating a low confidence

- Tier 3 studies have a high risk of bias indicating a very low confidence [KH1]

Individual studies were assessed using the Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating (ROB) Tool (NTP, 2015). Studies are ranked by tier based on evaluating seven domains of bias. Tier 1 studies have a low risk of bias or probably a low risk of bias (highest confidence), Tier 2 studies have a probable high risk of bias (low confidence) and Tier 3 studies have a high risk of bias (very low confidence).

| Reference | Study design; location (country, region) | Sample size | Source | Asbestos fibre type; asbestos fibre concentration (fibres/L) | Health outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanarek et al. (1980); Conforti et al. (1981); Conforti (1983) | Ecological study; United States, San Francisco, Oakland, California |

Approximately 3 000 000 people | Naturally occurring | Chrysotile; 25 x 103 to 36 x 106 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the digestive tract (M/F), esophagus (M/F), pancreas (M/F), stomach (M/F), large intestine (M), rectum (F), respiratory system (F), lung (M), trachea/bronchus/lung/pleura (F), breast (F), prostate (M), retroperitoneum (F) |

| Polissar et al. (1982) | Ecological study; United States, Western Washington, Puget Sound Region |

Major cities: 3 Water sources: 5 Water samples: 95 |

Sultan River Cedar River Tolt River Green River Lakewood wells |

Chrysotile: Sultan River: 206.5 x 104 Other areas: 7.3 x 104 |

Significant positive association with mortality from cancer of genital (F), multiple myeloma (F) Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the prostate (M), multiple myeloma (M), eye (M) and soft tissue (M) |

| Millette et al. (1983) | Ecological study; United States, Escambia County, Florida |

Potential high exposure: 46 123 people Low exposure: 86 897 people No exposure: 51 378 people |

A-C pipes | Amphibole, chrysotile; Amphibole (range): 0.1 to 0.5 x 106 Chrysotile (range): 0.1 to 0.5 x 106 |

No significant positive associations with mortality from cancer of the bladder, kidneys, pancreas, liver, lungs, and GI tract (esophagus, stomach, intestines, colon, rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, peritoneum) |

| Polissar et al. (1983a, 1983b, 1984) | Case-control study; United States, Everette, Washington |

Cases: 382 people Controls: 462 people |

Sultan River | Chrysotile; Approximately 200 000 000 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the stomach (M) and pharynx (M) |

A-C – asbestos-cement; F – females; GI – gastrointestinal; M – males. |

|||||

| Reference | Study design; location (country, region) |

Sample size | Source | Asbestos fibre type; asbestos fibre concentration (fibres/L) |

Health outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masson et al. (1974) | Ecological study; United States, Duluth, Minnesota, Hennepin County |

Duluth: 105 759 people Minnesota: 3 371 603 people Hennepin County: 825 986 people |

Industrial waste | NR; NR |

Significant positive association with mortality from cancer of the digestive tract (M/F), esophagus (M), stomach (M/F), pancreas (F), liver (F), large intestine (F), rectum (M/F) and lung (M) |

| Wigle (1977) | Ecological study; Canada, Quebec |

(Municipalities; Population) Group 1 (2; 31 714 people) Group 2 (6; 93 620 people) Group 3 (14; 294 396 people) |

Industrial waste | Chrysotile; Asbestos: Raw: 1 200 x 106 Filtered: 200 x 106 Thetford Mines: Raw: 172 x 106 Raw: 1 300 x 106 Drummondville: Raw: 680 x 106 Filtered: 1.1 x 106 Plessisville: Raw: 13 x 106 |

Significant positive association with mortality from cancer of the upper GI tract (F), stomach (M), pancreas (F), colorectal (M), large intestine (F), lung (M), uterus (F), prostate (M), kidney (F), lymphoma (F), brain (M) Significant positive association with mortality from non-cancer diseases (disease types not specified) (M/F) |

| Harrington et al. (1978); Harrington and Craun (1979) | Ecological study; United States, Connecticut |

Approximately 576 800 people | A-C pipes | Chrysotile; Less than LOD to 7 x 105 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the large intestine (M/F), stomach (M/F) and rectum (M/F) |

| Meigs et al. (1980) | Ecological study; United States, Connecticut |

Group 1: 82 towns Group 2: 11 towns Group 3: 76 towns |

Group 1: A-C pipes Group 2: Naturally occurring Group 3: N/A |

Chrysotile; Group 1: less than 0.1 x 106 Group 2: NR Group 3: approximately 0.005 x 106 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the pancreas (M) and lung (M) |

| Levy et al. (1976); Sigurdson et al. (1981); Sigurdson (1983) | Ecological study; United States, Duluth, Minnesota |

100 578 people | Industrial waste | Amphibole; 1 to 30 x 106 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the stomach (M), large intestine (M/F), corpus uteri (F), prostate (M), peritoneum/ retroperitoneum (M) Significant positive association with mortality Footnote 1 from cancer of the GI (F), stomach (M/F), pancreas (F), small intestine (M/F) and rectum (M/F) |

| Toft et al. (1981) | Ecological study; Canada |

71 municipalities | Naturally occurring Industrial waste A-C pipes |

Chrysotile (major type), amphibole (minor type); Amphibole: 13 x 106 (max) Chrysotile: greater than 10 x 106 in approximately 5% of population receiving water; greater than 100 x 106in approximately 0.6% of population receiving water; 1800 x 106(max) |

Significant positive association with mortality from cancer of the digestive system (M), stomach (M) and lung (M) Significant positive association with mortality from respiratory system disease (non-cancer) (M) |

| Sadler et al. (1984) | Ecological study; United States, Utah |

Exposed: 14 communities Non-exposed: 27 communities |

A-C pipes | NR Less than LOD |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the gall bladder (F), kidney (M) and leukemia (M/F) |

| Wigle et al. (1986) | Ecological study; Canada |

71 cities | Sherbrooke: Naturally occurring Other cities: NR |

Chrysotile; Filtered: Raw: 0.7 to 83.0 x 106 Distribution system: 0.03 to 3.0 x 106 Unfiltered: Raw: 0.3 to 280 x 106 Distribution system: 1.9 to 153 x 106 |

No significant positive association with mortality from cancer of the tongue, mouth, and pharynx, esophagus, stomach, large intestine except rectum, large intestine including rectum, rectum, liver, pancreas, total GI tract, breast, ovary, prostate, bladder, kidney, and brain |

| Howe et al. (1989) | Ecological study; United States, Woodstock, New York |

2 679 people | A-C pipes | Chrysotile, crocidolite; 3.2 to 304.5 x 106 Fibres greater than10 µm (1-10%): 0.9 to 15.1 x 106 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the buccal cavity (M) and prostate (M) |

| Andersen et al. (1993); Kjaerheim et al. (2005) | Cohort study; Rural regions in Norway |

726 people | A-C tiles | Chrysotile (92%), amphibole (8%); 1.8 x 109 to 7.1 x 1010 |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the GI tract (M), stomach (M) and large intestine (M) |

| Browne et al. (2005) | Ecological study; United States, Woodstock, New York |

Exposed: 1 852 people All cohort: 2 936 people | A-C pipes | Greater than 90% chrysotile: Greater than 10 x 106 in 4/5 samples |

Significant positive association with incidence of cancer of the pancreas (M) |

| Fiorenzuolo et al. (2013) | Ecological study; Italy, Senigallia |

NR | A-C pipes | Amosite; 3/20 samples had asbestos concentrations less than 2 680 |

No significant positive association with incidence of and mortality from cancer of the GI tract |

| Mi et al. (2015) | Case-control study; China, Dayao County |

Cases: 54 people Controls: 108 people |

Naturally occurring | Crocidolite; Well water: 8.6 x 106 Surface water: 1.37 x 108 |

Significant positive association with mortality from cancer of the GI tract (sex not indicated) |

A-C – asbestos-cement; F – females; GI – gastrointestinal; LOD – limit of detection; M – males; N/A – not available; NR – not reported; OHAT ROB – Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Risk of Bias Rating (ROB). |

|||||

The OHAT framework was also used to evaluate the confidence in the epidemiological data for cancer outcomes for 15 organ systems as well as the data for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (non-cancer outcomes). The organ systems assessed were the upper aerodigestive tract, digestive tract, digestive organs, mesothelium, abdominal cavity, respiratory system, kidney, urothelium, nervous system and eye, female breast, reproductive system and tract, male reproductive system, endocrine system, lymphoid and hematopoietic system, skin and connective tissues. The results of the organ system confidence analysis are summarized in Go et al., 2024. Twelve of the 17 studies were of ecological design that carry a low level of confidence in the reported health outcomes, whereas 5 of the 17 studies were cohort and case-control design that have a moderate confidence in the reported health outcomes. With further evaluation of the factors that can increase (large magnitude of response, dose response, low residual confounding, consistency across populations) or decrease (risk of bias, unexplained inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) confidence, the final confidence ratings across all organ systems are largely considered as very low (see Go et al., 2024). Overall, all organ systems examined either displayed very low confidence levels or lacked sufficient evidence indicating a health outcome.

Of note, 15 of the 17 studies (Tables 3a and 3b) assessed stomach cancer with eight studies reporting at least one statistically significant positive association for mortality or incidence. The case-control and cohort studies by Polissar et al. (1984) and Kjaerheim et al. (2005) reported increased stomach cancer incidence among males with an odds ratio of 1.78 (95% confidence interval lower bound of 1.04) and a standardized incidence ratio of 1.6 (95% confidence interval of 1.0 to 2.3), respectively. Additionally, Kjaerheim et al. (2005) reported an increased standardized incidence ratio of 1.7 (95% confidence interval of 1.1 to 2.7) among male lighthouse keepers who were exposed for over 20 years. The remaining 13 ecological studies are considered as providing insufficient evidence for stomach cancer. Given that only two moderately strong studies indicate a potential for stomach cancer, the weight of evidence is considered insufficient to assess whether oral exposure to asbestos fibres in drinking water causes stomach cancer.

Limitations in the current epidemiological evidence for cancer and non-cancer outcomes have also been discussed by agencies and organizations in other countries, including the U.S. (ATSDR, 2001; OEHHA, 2003) and France (ANSES, 2021) as well as in another weight of evidence review by Cheng et al. (2021). These limitations are:

- ecological-design studies are not effective in demonstrating associations between exposure and health impacts since the duration and levels of exposure are not precisely determined. Therefore, without a dose-response relationship, determining causality between asbestos exposure and health outcomes is not feasible

- there is a lack of consistency in the reporting of asbestos exposures (numbers versus mass of fibres), and for most studies, fibre size was not measured or discussed

- potential confounding factors such as occupational exposures to asbestos, co-exposure to other carcinogens, ethnicity, employment, socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors (such as smoking, alcohol consumption and diet) are often not considered

- the use of cancer death certificates to identify cancer outcomes can lead to non-differential bias due to poor coding and different definitions of cancer sites

- often these studies cover a time period that is insufficient for investigating cancer outcomes

- many of the studies use different statistical methods, lack statistical power or do not report p-values or confidence intervals which further limits any interpretations of health outcomes

In summary, the epidemiological data for both cancer and non-cancer health outcomes following oral exposure to asbestos are considered insufficient for establishing a point of departure for risk assessment:

- the majority of the reported associations between health outcomes and oral exposure do not show a large magnitude of effect

- there are no clear dose-response relationships over multiple levels of exposure or exposure durations

- none of the studies accounted for all of the important potential confounders

- higher degrees of bias in most studies lead to an overall low confidence in the reported health outcomes

- there was no clear evidence of associations across different populations and locations for any of the health outcomes

B.2.2 Effects on experimental animals

Health Canada searched current scientific literature for studies of non-human mammals that were orally exposed to asbestos, published up to June 2023. Details of the screening approach are in Go et al., 2024. A total of 34 publications were determined to be relevant for further review. These publications were dated between 1974 and 2008, and covered 60 different types of asbestos oral exposure experiments. The systematic review is discussed in greater detail in Go et al., 2024.

Oral exposure to asbestos did not impact body weights, survival rates or mortality in chronic studies with doses ranging from 10 to 360 mg/week by gavage, 45 to 13 000 MFL in water and 20 to 300 mg/day (and 0.003% to 10%) in food. No observed systemic, reproductive, developmental, or neurological effects from oral exposure to different asbestos fibre types and sizes were reported in several large chronic exposure studies in rats and hamsters conducted by the U.S. NTP (NTP, 1983; 1985; 1988; 1990a; 1990b; 1990c). A lack of adverse reproductive and developmental outcomes from chrysotile ingestion was also reported by Schneider and Maurer (1977), Rita and Reddy (1986) and Haque et al. (2001), further supporting the NTP study findings.

The focus of the animal data presented below is on cancer outcomes, specifically in the GI tract. Guidance from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2018; Guideline #451) dictates that animal carcinogenicity studies should include large groups of more than 50 rodents per sex and administer a minimum of 18 to 24 months of duration of exposure with three test doses and a concurrent control. Of the 34 chronic carcinogenicity publications identified in the systematic review, 10 studies met the criteria for animal number and exposure length. Table 4 presents the key information from these studies and provides an indication as to whether the findings support carcinogenicity from oral exposure. For the 24 chronic carcinogenicity publications excluded for not meeting the OECD guidance, 19 studies showed no effects, two showed benign tumour and non-precursor outcomes, and the remaining two publications showed possible cancer outcomes. It is difficult to draw meaningful interpretations from the 19 studies that showed no effect due to significant weaknesses in their experimental designs, including small samples sizes, often single-dose exposures as well as inadequate latency periods for determining cancer outcomes.

| Reference | Exposure | Asbestos characteristics | Results | Support for carcinogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donham et al. (1980) | Chrysotile, 10% in food pellets (rat, N = 189) | UICC "B", not washed or treated | No significant differences in the number of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of any one type in the colon compared to controls; authors observed 4 tumours in asbestos-dosed animals and 5 tumours in control animals | Negative |

| NTP (1983) | Amosite, 1% in food (hamster, N = 252 M / 254 F) | S-33 (Transvaal), single milled median length: 4.37 μm; range 0.85 to 995 μm; 24.6% greater than 100 μm long; many greater than 1 000 μm |

No increase in the incidence of GI tumours or tumours in any other site | Negative |

| NTP (1985) | Chrysotile, 1% in food, SR length of fibres | SR: COF-25 median length: 0.66 μm; range: 0.88 to 51.1 μm; 98% less than 10 μm |

No neoplastic or nonneoplastic disease was associated with exposure to SR fibres | Negative |

| NTP (1985) | Chrysotile, 1% in food, IR length of fibres (rat 88 to 250 M / 88 to 250 F) |

IR: Plastobest-20 median length: 0.82 μm; Range: 0.104 to 783.4 μm; 65% greater than 10 μm; 14% greater than 100 μm |

IR chrysotile significantly increased the incidence of benign epithelial neoplasms (adenomatous polyps) in the large intestine of males (9/250) when compared to pooled NTP asbestos study controls, but not when compared to concurrent controls; authors noted that this finding was of biological importance | Positive |

| NTP (1988) | Crocidolite, 1% in food (rat, N = 250 M / 250 F) | ML-6, milled twice; mean length: 10 μm |

Crocidolite did not increase the incidence of neoplastic or nonneoplastic disease | Negative |

| NTP (1990a) | Amosite, 1% in food (rat, N = 200 to 250 M / 250 to 400 F) | S-33 (Transvaal), single milled; median length: 4.37 μm; range 0.85 to 995 μm; 24.6% greater than 100 μm; many greater than 1 000 μm | Amosite was not carcinogenic at this concentration | Negative |

| NTP (1990b) | Chrysotile, 1% in food, SR length of fibres (hamster, N = 253 M / 252 F) Chrysotile, 1% in food, IR length of fibres (hamster, N = 251 M / 252 F) |

SR: COF-25 median length: 0.66 μm; range: 0.88 to 51.1 μm; 98% less than 10 μm IR: Plastobest-20 median length: 0.82 μm; range: 0.104 to 783.4 μm; 65% greater than 10 μm; 14% greater than 100 μm |

Significant increase in adrenal cortical adenomas in males exposed to SR and IR chrysotile, and in females receiving IR chrysotile, compared to pooled NTP study controls, but not significant when compared with concurrent controls Authors noted that the biological importance of this finding was questionable |

Negative |

| NTP (1990c) | Tremolite, 1% in food (rat, N = F0: 70 M / 140F; F1: 250 M / 250 F) | Governeur Talc Company, crushed and milled; 72% tremolite, 25% serpentine, 3% other; 93.6% less than 10 μm; 75% less than 4 μm |

No increase in the incidence of tumours | Negative |

| Smith et al. (1980) | Amosite: 0.5, 5, 50 mg/L in water (130, 1 300, 13 000 MFL), (hamster, N = 30 M / 30 F) | UICC, untreated; mean length 2.4μm; 91.5% less than 5 μm; 97.8% less than 10 μm; 2.6% greater than 10 μm | No Treatment-related increases in the incidence of tumours | Negative |

| Smith et al. (1980) | Taconite ore tailings: 0.5, 5, 50 mg/L in water (45, 450, 4 500 MFL) (hamster, N = 30 M / 30 F) | Mean length 2.1 μm; 95.8% less than 5 μm; 99.7% less than 10 μm; 0.3% greater than 10 μm | No significant increase in tumours | Negative |

| Truhaut and Chouroulinkov (1989) | Chrysotile, 10, 60, 360 mg/day in palm oil (rat, N = 70 M / 70 F) |

UICC | No differences in tumour frequency with respect to localization, type of fibre, dose and sex | Negative |

| Truhaut and Chouroulinkov (1989) | Chrysotile/ Crocidolite (75%/25%), 10, 60, 360 mg/day in palm oil (rat, N = 70 M / 70 F) |

UICC | No evidence of carcinogenic effects | Negative |

F – female; GI – gastrointestinal; IR – intermediate range; M – male; MFL – million fibres per litre; N – number; NTP – National Toxicology Program; SR – short range; UICC – Union for International Cancer Control (asbestos standard). |

||||

Limitations of the available animal oral carcinogenicity studies have also been identified by international risk assessment organizations (OEHHA, 2003; ANSES, 2021). These limitations include:

- the majority of studies available in the literature exposed small groups of animals, which make it difficult to determine the statistical significance of digestive system tumour development in rats, which is a rare event; the NTP studies, however, with sufficient group sizes, are considered the most informative of all available studies

- the majority of studies implemented a low number of doses (often a single dose), which limits any interpretation of dose-response relationships

- the use of different exposure media (water versus food) limits the comparison of results given their influence on the availability and residence time of asbestos in the GI tract

- in some studies, the latency period is inadequate for determining cancer outcomes

- the NTP studies use different control groups (some comparisons were made with experimental controls whereas other comparisons were made with controls combined over several experiments), which can influence the statistical significance and interpretation of the observed results

In summary, there are a limited number of animal studies providing quality data on the health outcomes from oral exposure to asbestos. Several NTP chronic toxicity studies in rats and hamsters did not report any health outcomes of biological significance following oral exposure to high doses of amosite, chrysotile, crocidolite, or tremolite fibres. Although benign adenomatous polyps were observed in the colon of male rats only that ingested intermediate length chrysotile fibres at a concentration of 1% in food (NTP, 1985), a higher dose of chrysotile (10%) did not cause an increase in cancerous lesions in the rat colon (Donham et al., 1980); therefore, the evidence for this health outcome is inconclusive. The authors of the NTP (1985) study noted that there was no indication of progression from benign adenomatous polyps to cancer over the lifetime length of the study and that there was no incidence of malignant epithelial neoplasms in the large intestine. In a similar study (NTP, 1990b), neither intermediate nor short range chrysotile fibres were found to be carcinogenic in hamsters. Overall, the lifetime animal studies do not provide consistent and conclusive evidence that oral exposure to asbestos fibres causes cancer in any specific digestive organs.

B.2.3 Effects in vitro

In vitro studies can aid in understanding how toxicity can occur at the cellular level. However, they do not serve as an appropriate indicator of the potential health effects from drinking water exposure. The design of such studies does not accurately reflect the complex human physiological environment, given that cells are directly and continuously exposed, cells or tissues are studied in isolation and the physiological processes that metabolize or remove the contaminant are absent.

The limited available in vitro evidence shows that fibre size, type and morphology can impact inflammatory, oxidative and immune responses. Hong and Choi (1997) treated Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts (V79 cells) with crocidolite and chrysotile at doses ranging from 0.16 to 20 µg/ml for 72 hours. They observed that the fibres were cytotoxic after phagocytosis induced multinucleate giant cell formation by interfering with mitosis. The authors also reported that, at higher doses, chrysotile was more potent at inducing multinucleate giant cells than crocidolite. Duncan et al. (2010) demonstrated that inflammatory marker expression (IL-8 and COX-2) in human bronchial epithelial cells was equally induced by 24-hour exposure to two different unfractionated amphibole fibre types (Libby-type versus amosite). However, when exposed to smaller-sized fibres (less than 2.5 um), the small-sized amosite was four times more potent than the Libby-type. Khaliullin et al. (2020) investigated asbestos fibre morphology and its influence on cytotoxicity, cytokine secretion, and transcriptional changes in murine alveolar macrophages (MPI cells) following exposure to asbestos and non-asbestos riebeckite or tremolite mineral particles for 24 hours. The dosage was based on mass, surface area, and particle number equivalent concentrations. Asbestos particles were observed to be more cytotoxic; however, both asbestos and non-asbestos particles of equal surface area or particle number induced similar lactate dehydrogenase leakage and impaired cell viability. All treatments increased chemokines, but not pro-inflammatory cytokines. Gene expression dysregulation patterns for several genes were also evaluated and found to differ (upregulation versus downregulation as well as degree of effect) depending on the asbestos mineral type.

B.2.4 Absorption, metabolism, distribution and excretion

B.2.4.1 Absorption

The absorption of ingested asbestos fibres has been demonstrated as being very low. Cook (1983) analyzed exposures from several laboratory animal and human environmental exposure studies and reported that only a small fraction of ingested fibres are likely to penetrate the GI tract; Millette et al. (1981) estimated absorption across the GI tract at approximately one in 1 000 fibres (0.1%). Factors that may influence the passage and uptake of asbestos fibres in the GI tract include total exposure time, the type of foods or fluids present with the asbestos fibres, the permeability of the GI mucosa, the presence of mucosal abnormalities, altered intestinal motility and the intestinal tract microbiota present (Cook, 1983; Pambianchi et al., 2022). In addition, the GI tract serves as a strong barrier against the absorption of asbestos fibres due to its robust structure consisting of mucin-covered, tightly packed columnar epithelial cells, sub-mucosal connective tissue and muscular layers. Following a review of animal and human studies on intestinal transport of macromolecules in food, Weiner (1988) proposed four mechanisms by which macromolecules ranging from 0.2 to 20 µm in size could be transported through the intestinal barrier. The mechanisms are: uptake into specialized epithelial cells (with fewer microvilli) and/or macrophages of the Peyer's patches or gut-associated lymphoid tissue; endocytosis of particles less than 2 µm in length into columnar epithelial cells by membrane-bound vesicles; possible uptake into goblet cells; and paracellular transport through "leaky" tight junctions between the cells (persorption) for larger particles like asbestos.

Dermal absorption of asbestos fibres is expected to be negligible (OEHHA, 2003).

B.2.4.2 Distribution

Ingested fibres, once absorbed, can be transported to various organs. Once past the cells lining the stomach or intestine, absorbed fibres reach the bloodstream or lymphatic system, which can carry them to other tissues where they are deposited or cleared. The fibres found beyond the GI tract are generally shorter in length than those originally ingested. It has been suggested that fibres shorter than 1 µm can cross the intestinal barrier by persorption (para-cellular passage); fibres of this size, according to the available mode of action data, are unlikely to be a health concern.

In mice exposed to asbestos in drinking water, fibres were detected in the stomach, intestines, blood and liver (Zheng et al., 2019). Hasanoglu et al. (2008) provided evidence that ingested asbestos fibres migrated to internal organs and caused histopathological changes. In rats that drank water containing chrysotile fibres (1.5 and 3.0 g/L) for 6, 9 or 12 months, fibres were found in the spleen and lung, likely reaching these organs through the lymphohematological route. There is limited evidence available on placental transfer of asbestos following oral exposure. Haque et al. (2001) investigated placental transfer in pregnant mice exposed (by gavage) to chrysotile asbestos at a concentration of 50 µg/0.2 ml of saline. The authors reported that the lungs of pups were found to contain a mean fibre count of 780 fibres/g, and the mean fibre count in the liver was 214 fibres/g.

B.2.4.3 Metabolism

Asbestos fibres are not metabolized. However, certain fibre types can be altered or degraded by the acidity of digestive fluids and physical processes of the GI tract, which can serve as a mechanism for reducing toxicity. Seshan (1983) showed that exposure of chrysotile fibres to strong acids and simulated gastric juices caused physical and chemical alterations such as changes in crystal structure, magnesium loss and changes in surface charge (from positive to negative); however, crocidolite (an amphibole type) was unchanged with acid exposure. The alteration or degradation of asbestos fibres by GI mechanisms supports the observation of shorter fibres in tissues (compared to the exposure media) analyzed following oral exposures (ANSES, 2021).

B.2.4.4 Excretion

Nearly all fibres pass through the digestive system within a few days and are excreted in the feces after approximately 48 hours following oral ingestion in rats (ATSDR, 2001). An estimated 0.1% of fibres in drinking water containing an unspecified high asbestos content were eliminated through urine in a human ingestion study (Cook and Olson, 1979). The eliminated fibres were less than 1 µm in length.

B.2.5 Genotoxicity and carcinogenicity

Asbestos is a known carcinogen through the inhalation route and has been assessed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a Group 1 carcinogen (carcinogenic to humans). It causes mesothelioma as well as other cancers including lung, laryngeal and ovarian. Colorectal, stomach and pharynx cancers have also been shown to be positively associated with inhalation exposure in occupationally exposed workers (IARC, 2012). The genotoxicity of inhaled fibres has been reported in occupational and non-occupational populations exposed to different types of asbestos fibres (ATSDR, 2001); however, no population studies have investigated the genotoxicity of asbestos following ingestion.

A limited number of in vivo studies in animal models have reported no increased genotoxicity following oral exposure to asbestos. Lavappa et al. (1975) observed no increased frequency of micronuclei in bone marrow from mice gavaged with 4 to 400 mg/kg of chrysotile as well as no increase in the number of chromosomal aberrations in the bone marrow of monkeys gavaged with 100 or 500 mg/kg of chrysotile. Rats administered 50 mg/kg of anthophyllite or crocidolite showed no increased frequency of sister chromatid exchange in bone marrow cells 24 hours following a single gavage dose (Varga et al., 1996a; 1996b).

Evidence from in vitro studies shows that genotoxic or mutagenic changes can vary depending on the target cell. Chromosomal aberrations have been demonstrated in human mesothelial cells, lymphocytes, and amniotic fluid cells following exposure to chrysotile fibres (Valerio et al., 1980; Olofsson and Mark, 1989; Emerit et al., 1991; Korkina et al., 1992; Pelin et al., 1995; Dopp et al., 1997; Dopp and Schiffmann, 1998; Takeuchi et al., 1999), but not in fibroblasts or promyelocytic leukemia cells (Sincock et al., 1982; Takeuchi et al., 1999). Mutagenicity is dependent on differences in phagocytic activity of the cell (Both et al., 1994; 1995) with human phagocytic cells, such as mesothelioma cells, being more susceptible to asbestos injury than non-phagocytic cells like lymphocytes (Takeuchi et al., 1999). Amount of exposure is also important whereby a threshold concentration must be exceeded before chromosomal aberrations are observed (DiPaolo et al., 1983; Oshimura et al., 1984; Jaurand et al., 1986; Palekar et al., 1988). Although genotoxic and mutagenic changes are indirect effects of asbestos toxicity (see section B.2.6), fibres have also been shown to physically interfere with chromosome segregation during mitosis and cause clastogenic effects (ATSDR, 2001; IARC, 2012). Asbestos exposure has led to chromosomal aberrations such as aneuploidy, fragmentation, breaks, rearrangements, gaps, dicentrics, inversions and rings in Chinese hamster ovary cells and Syrian hamster embryo cells, as well as rat and human mesothelial cells, lymphocytes and amniotic fluid cells. It was suggested that asbestos fibres physically interfere with chromosome segregation during mitosis to cause clastogenic effects (ATSDR, 2001; IARC, 2012).

Finally, dose-response studies have shown that a threshold concentration (ranging from 7 to 40 µg/ml) must be attained before chromosomal aberrations are seen (Dipaolo et al., 1983; Jurand et al., 1986; Oshimura et al., 1984; Palekar et al., 1988).

B.2.6 Mode of action

The toxicity of asbestos exposure is influenced by many factors, including duration and frequency of exposure, tissue-specific dose over time, persistence of the fibres in the tissue (influenced by the absorption, distribution and clearance of fibres), individual susceptibility, and the type and size of the fibres. The mechanisms associated with inhaled asbestos toxicity are influenced by two key fibre features: physical attributes—such as length, width, aspect ratio and surface area—and surface chemical composition and reactivity (Aust et al., 2011).

Pepelko (1991) evaluated animal data comparing the effectiveness of oral versus inhalation exposure and the risk of cancer. Of the 29 known carcinogens evaluated, three insoluble forms of particulate matter (including asbestos) showed an increased risk of cancer only through the inhalation route, while the other 26 chemicals showed similar cancer risks from both the oral and inhalation routes of exposure. Furthermore, in the case of asbestos, inhalation exposure was estimated as 100 times more potent than exposure via the oral route. It is important to note that the oral exposure study used for comparison (Donham et al., 1980) reported tumours in the colons of four dosed animals and five control animals, therefore providing inconclusive evidence of cancer following oral exposure. Nonetheless, Pepelko (1991) showed that, for asbestos, inhalation exposure is more hazardous than oral exposure, which is likely due to deposition and longer retention of fibres in the lung tissue compared to the GI tract where asbestos fibres are rapidly eliminated.