Discussion Paper: Legislative Review of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

Download in PDF format

(1.02 MB, 21 pages)

Organization: Health Canada or Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2022-03-16

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Discussion Areas

- Protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products

- Protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products

- Protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products

- Prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products

- Enhance public awareness of health hazards

- Conclusion

Introduction

The Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA) came into force on May 23, 2018. It amended the former Tobacco Act, which was originally enacted in 1997. The purpose of the TVPA with respect to tobacco products is the same as the former Act - to provide a legal framework in response to the national public health problem posed by tobacco use. The TVPA also created a new legal framework, in conjunction with other pieces of federal legislation, to respond to the increasing availability of vaping products (with and without nicotine) in Canada and to help ensure that Canadians would be appropriately informed about and protected from the risks associated with these products. While the TVPA still sets out the specific objectives of the Act with respect to tobacco products, its purpose statement was amended in 2018 to include specific objectives with respect to vaping products, and established a link between those vaping products provisions and the overall tobacco control objectives of the Act.

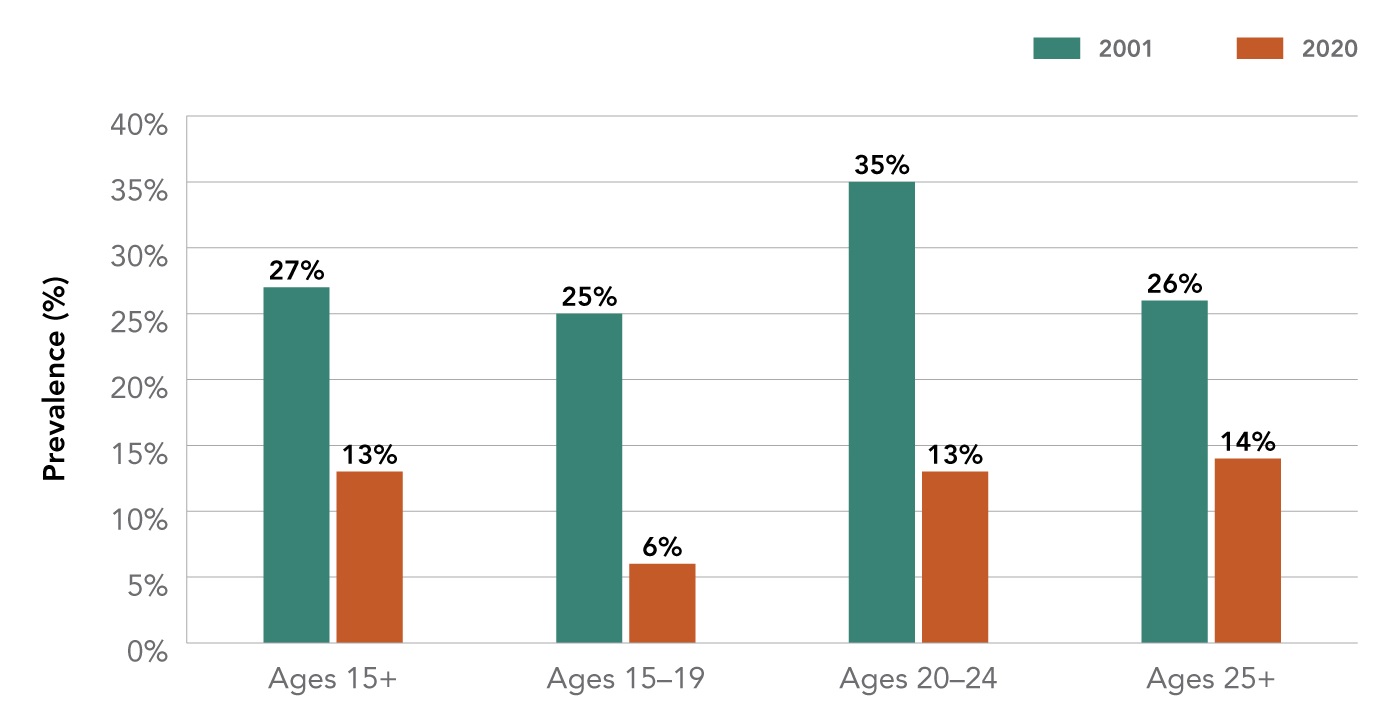

The effective regulation of tobacco and vaping products is a key element of Canada's Tobacco Strategy - one that supports achieving the ambitious target of less than 5 percent tobacco use by 2035. Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death and disease in Canada, with approximately 48,000 people dying from smoking-related illnesses every year. Footnote 1 Decades of tobacco control have resulted in significant progress being made with respect to reducing the number of Canadians who smoke. The smoking rate has seen a steady and continuing decline from 35 percent in 1985 Footnote 2 to 13 percent in 2020, or 4.2 million Canadians who smoke Footnote 3. Reducing rates of tobacco use to reach the goal of less than 5 percent tobacco use by 2035 remains a significant challenge. It was in this context that the TVPA sought to strengthen proven measures that had contributed to a reduction in tobacco use.

The new legislation sought to regulate vaping products in a way that underscored that these products were harmful for youth and non-users of tobacco products. At the same time, it recognized emerging evidence indicating that, while not harmless, vaping products were a less harmful source of nicotine for an individual who smokes and quits smoking completely. Around the same time that the new legislation was being enacted, vaping products were being used by significantly more people in Canada. In 2017, nearly 900,000 Canadians over the age of 15 had reported past 30-day use Footnote 4 and the design of and market for these products had evolved significantly since they were first introduced in Canada in 2006.

During the course of developing and debating the proposed legislation, protecting young persons and non-users of tobacco products from nicotine addiction and tobacco use emerged as a key objective. At the same time, Parliament recognized that while vaping presented the potential to be a less harmful source of nicotine for persons who smoke and switch completely to vaping, there was uncertainty around the health risks and benefits of using these products. Accordingly, broad regulatory authorities pertaining to elements of the legislation, which included advertising, promotion, labelling, access, flavours, and product attributes, were included in the TVPA to enable the Government of Canada to respond to emerging evidence and fine-tune restrictions as needed. As an added safeguard, the Act also included a requirement for a legislative review of the provisions and operation of the TVPA, three years after coming-into-force, and every two years thereafter.

While the review of the TVPA will focus on the federal legislation and efforts, it is important to recognize that all orders of government share responsibility within their own authorities/jurisdiction for adequately promoting and protecting the health of Canadians from known health hazards such as tobacco use. For example, provincial and territorial governments are primarily responsible for restricting smoking in workplaces and public places, such as restaurants, bars and shopping centres. For more information regarding the tobacco and vaping regulations in a particular province or territory, please consult their individual websites.

The first review of the Act will focus primarily on the vaping-related provisions in the TVPA - in particular the provisions to protect young persons. More specifically, it will assess the operation of the Act, and examine the early evidence from the Act's first three years of existence to assess whether it is making progress towards achieving its stated vaping related objectives. Subsequent reviews, which will take place every two years, will focus on additional elements of the TVPA, including the tobacco-related provisions.

We want to hear from you

A key part of this review is seeking the perspectives of Canadians, experts, and other stakeholders as it relates to the operation of the TVPA, with a particular emphasis on protecting young persons.

You are invited to participate in this consultation by sharing your perspectives. To assist in providing your input, a list of key questions for each vaping-related objective in the Act has been provided. You are also encouraged to submit any evidence that you may have to support your responses.

You may participate by sending your written submission by April 27, 2022 to: legislativereviewtvpa.revisionlegislativeltpv@hc-sc.gc.ca

Please note: you must declare any perceived or actual conflicts of interest with the tobacco industry when providing input to this consultation. If you are part of the tobacco industry, an affiliated organization or an individual acting on its behalf, you must clearly state so in your submission.

Health Canada is also interested in being made aware of perceived or actual conflicts of interest with the vaping and/or pharmaceutical industry. Therefore, please declare any perceived or actual conflicts of interest, if applicable, when providing input. If you are a member of the vaping and/or pharmaceutical industry, an affiliated organization or an individual acting on their behalf, you are asked to clearly state so in your submission.

Please do not include any personal information when providing feedback to Health Canada. The Department will not be retaining your e-mail address or contact information when receiving your feedback and will only retain the comments you provide. Submissions will be summarized in a final report; however, comments will not be attributed to any specific individual or organization. This final report will be tabled in Parliament in 2022 and will be made public on Canada.ca at that time.

Discussion Areas

In the three years since the TVPA was enacted, the vaping product market continues to evolve and additional evidence is emerging. The Act includes an overarching purpose as it relates to vaping products, which is to support the overall tobacco control objectives of the Act and prevent vaping product use from leading to the use of tobacco products by young persons and non-users of tobacco products.

In particular, the Act enumerates five specific vaping-related objectives:

- protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products;

- protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products;

- protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products;

- prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products; and

- enhance public awareness of those hazards.

In order to meet these objectives, the Act regulates the manufacture, sale, labelling and promotion of vaping products sold and manufactured in Canada. Vaping products are defined as a distinct set of products that are separate from tobacco products. Measures relating to vaping products contained in the Act are similar to, but not as restrictive as, those that apply to tobacco products. This reflects the scientific evidence available at the time the TVPA was put in place, that vaping products are harmful, but less harmful than tobacco products. As such, the legislation restricts access to vaping products to persons over 18 years of age and also includes significant restrictions on the promotion of vaping products, including prohibiting advertising that appeals to youth, lifestyle advertising, testimonials or endorsements and sponsorship promotion. It also prohibits the promotion of flavours that are appealing to youth or specific flavour categories listed in the Act (confectionary, dessert, cannabis, soft drink and energy drink) and restricts giveaways of vaping products or branded merchandise. The Act also includes regulatory authorities to respond to emerging issues, as required. Over the past three years, the Government of Canada has used these regulatory authorities to implement further restrictions on vaping products to protect youth and non-users of tobacco products.

This discussion paper will examine each of the vaping-related objectives listed above, provide a summary of the current context, and describe federal government actions that have been taken to respond to issues that have emerged since the legislation was enacted. Each section will include a list of key questions to assist in providing your input.

Protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products

Context :

The Act aims to protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products

from inducements to use vaping products. As such, the legislation includes

significant restrictions on the promotion of vaping products, including

restricting giveaways of vaping products or branded merchandise, along with

prohibiting the promotion of flavours that are appealing to youth or

specific flavour categories listed in the Act (confectionary, dessert,

cannabis, soft drink and energy drink). It also prohibits advertising that

appeals to youth, lifestyle advertising, testimonials or endorsements and

sponsorship promotion.

Vaping product usage in Canada increased overall after the TVPA was enacted in 2018. Some of this can be attributed to the expansion of the market as a result of the introduction of a new legal framework for these products. At the same time, vaping product technology and design was changing rapidly with many new products arriving on the market that were smaller, sleeker and easier to use, contained high concentrations of nicotine, and offered in a variety of flavours. Major international players in the vaping product market also began to introduce new products in Canada. During this same period, television, social media and retail advertising which could be seen or heard by youth increased dramatically.

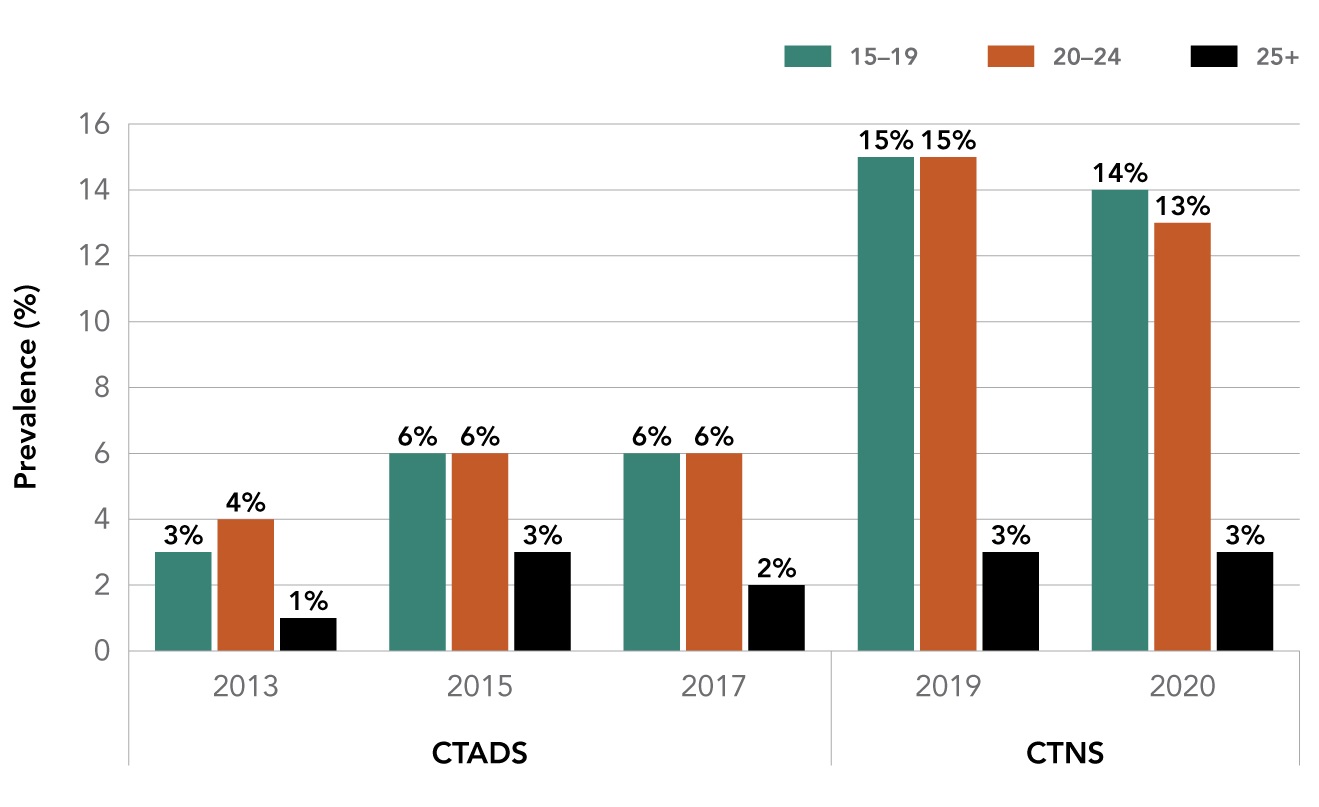

All of these factors played a role in the rise in youth vaping. Surveys have shown that youth vaping rates doubled over the two-year period since 2017, increasing from 6 percent (127,000) in 2017Footnote 5 to 14 percent (291,000) in 2020, unchanged from 2019.Footnote 6 While the most recent available data, released in March 2021 by Statistics Canada, revealed that the concerning trend of rising youth vaping rates may be levelling off, additional data is needed to reliably assess trends, especially in light of the social and economic restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Daily use of vaping products by youth aged 15-19 years of age was 5 percent (107,000) in 2020.

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

Source: Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) 2013, 2015, 2017 / Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2019, 2020.

| Prevalence of past-30-day use of vaping products in Canada by age (2013 - 2020) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | 2020 |

| 15-19 | 3% | 6% | 6% | 15% | 14% |

| 20-24 | 4% | 6% | 6% | 15% | 13% |

| 25 + | 1% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 3% |

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys

There have also been concerns that an increase in youth vaping may lead to increases in youth smoking rates in Canada. However, recent data, presented below, suggests that, thus far, this has not been the case. Smoking rates, for both youth and adults, continue to decline and are at an all-time low. The prevalence of daily smoking among youth aged 15 to 19 years was so low (small sample size) that it was considered to be 'unreportable' in 2020.

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

Source: Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2001, 2020.

| Prevalence of past 30-day smoking in Canada by age (2001 - 2020) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 2001 | 2020 |

| 15 and + | 27% | 13% |

| 15-19 | 25% | 6% |

| 20-24 | 35% | 13% |

| 25 + | 26% | 14% |

With respect to adult use, there is some evidence that adults who smoke are using vaping products as a less harmful source of nicotine. Surveys also show that vaping rates for adults 25 years and older have changed little since 2015.Footnote 7 Data from the 2020 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey indicate that vaping products were used by 3 percent (854,000) of Canadians aged 25 years and older.Footnote 8 Among this group, 94 percent (799,000) identified themselves as current or former smokers.Footnote 9 Among those who currently smoke and vape, 49 percent (192,000) stated that they are vaping to quit and/or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.Footnote 10

Given the rise in vaping products promotion following the introduction of the Act, to which youth were exposed on television, in social media, at events, on outdoor signs, and in retail locations, the Government took action to strengthen the existing restrictions on promotions by putting in place the Vaping Products Promotion Regulations (VPPR) in July 2020. The VPPR prohibit the advertising of vaping products that can be seen or heard by young persons. For example, advertising in places such as recreational facilities, public transit facilities, on broadcast media, in publications, including those online, is prohibited, if the ads can be seen or heard by anyone under eighteen years of age. To limit youth exposure to the promotion of vaping products at points of sale, the VPPR also prohibit the display of vaping products and vaping product-related brand elements that can be seen by young persons.

To ensure compliance with the Act and its regulations, Health Canada undertakes proactive compliance promotion activities (e.g. distributing educational materials) to raise awareness within the vaping industry of their obligations under the TVPA and its regulations. Health Canada inspectors regularly perform inspections of vaping product retailers, specialty vaping establishments, manufacturers, online-based points of sale, and any other establishments where vaping products are sold, promoted, manufactured or labelled. Regular enforcement actions to address non-compliance include issuing warning letters and seizing products. For example, Health Canada inspectors visited more than 3,000 specialty vape shops and convenience stores across the country between July and December 2019. These inspections resulted in the seizure of more than 80,000 units of non-compliant vaping products. In 2020 and 2021, within the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada conducted virtual inspections of 304 Instagram accounts of online retailers, particularly as it relates to promotion restrictions. Non-compliance was observed in 53 percent of inspections and resulted in warning letters being issued to the regulated parties. Health Canada continues to monitor to ensure compliance.

Since the new legislation was enacted in 2018, inspection activities carried out at retail establishments and online have revealed a range of non-compliance issues related to promotions aimed at youth. Health Canada has responded to these instances of non-compliance by issuing warning letters, seizing vaping products and by shutting down prohibited promotions in public places. Health Canada also engaged with vaping industry associations to urge them to take measures with their members to stop the continued, widespread non-compliance in the vaping market. The Department also publicly discloses the results of its compliance efforts on its website to further promote compliance within the industry and to provide transparency for Canadians.

Questions:

- Are the current restrictions on advertising and promotional activities adequately protecting youth?

- Are the restrictions within the Act and its regulations sufficient to address potential inducements to use these products by youth and non-users of tobacco products?

- Are there other measures that the Government could employ to protect youth and non-users from inducements to use vaping products?

- Does the TVPA contain the appropriate authorities to effectively address a rapidly evolving product market and emerging issues such as the observed increase in youth vaping?

- Has scientific evidence emerged in this area since the legislation was enacted in 2018 that points to the need for additional action or further restrictions?

Protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products

Context:

A key objective of the TVPA is protecting the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products. To support this, the TVPA restricts access to vaping products to persons over 18 years of age. This recognizes the negative health effects associated with nicotine use, and seeks to guard against the risk that nicotine dependence could lead to tobacco use and the resultant serious health hazards.

When the legislation was enacted, vaping products were relatively new to the market and there was limited scientific evidence on their long-term health impacts. While scientific knowledge continues to evolve, there is a general consensus in the scientific community that for people who smoke, switching completely to vaping is less harmful than smoking conventional cigarettes. In that context, potential public health benefits associated with reducing tobacco-related disease and death might be realized if adult tobacco users either quit or switched completely to vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine.

However, it is important to recognize that vaping products are not harmless. Vaping can increase a person's exposure to potentially harmful chemicals, including nicotine, which is found in most vaping products sold in Canada. Nicotine is highly addictive and youth can become dependent on nicotine at lower levels of exposure than adults. Moreover, exposure to nicotine during adolescence can negatively alter brain development and may have negative long-term effects on cognition.

Vaping products have evolved tremendously in the relatively short period of time since they were first introduced in Canada. New product formulations, and delivery mechanisms, some of which simplify usage and increase exposure to nicotine and other chemicals, have resulted in changing behaviours and preferences amongst users, particularly among youth.

In July 2020, the Government of Canada responded to these changes in the market by putting in place regulations to enhance awareness of the health hazards of using vaping products and protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on nicotine that could result from their use. The Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations (VPLPR) require all vaping products that contain nicotine to display a nicotine concentration statement and a health warning on the products and/or packaging about the addictiveness of nicotine.

In addition to enhancing awareness of health hazards, the government also took action to reduce the availability of high nicotine concentration vaping products in the Canadian market, which were shown to be appealing to youth. The Nicotine Concentration in Vaping Products Regulations (NCVPR), which came into force in July 2021, set a maximum nicotine concentration of 20mg/mL to make them less appealing, especially to youth, thereby lessening youth exposure to nicotine, which can result in dependence, increased risk of tobacco use and adverse health effects.

The Government of Canada has also implemented new surveillance tools to provide timely data on vaping and tobacco use, including the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey Footnote 11, and invested in a new national vaping module to the Canadian Community Health Survey.Footnote 12 These tools have produced nationally representative data to monitor smoking and vaping prevalence across Canada. In addition, the Government has committed $14 million over five years in grants and contributions funding through the Substance Use and Addictions Program to provinces, territories, non-governmental organizations, Indigenous organizations and individuals, to contribute to efforts to protect Canadians from the harms of smoking and nicotine addiction. For example, the Government of Canada contributed more than $1.1 million over 36 months to the University of Waterloo to support research on vaping use and cessation in youth (aged 16 to 19). The Government of Canada has also provided more than $670,000 over 21 months to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health to develop national evidence-based Low-Risk Nicotine Use Guidelines comparing the benefits and harms of using alternate nicotine delivery devices, including vaping products.

Questions:

- Are the current restrictions in the Act and its regulations sufficient to protect the health of young persons from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products?

- Are the new restrictions on nicotine concentration levels sufficient to protect youth and non-users of tobacco products from nicotine exposure? If not, what additional measures are needed?

- Are there other measures that the Government could employ to protect the health of young persons from exposure to and dependence on nicotine from vaping products?

- Has scientific evidence emerged in this area since the legislation was enacted in 2018 that points to the need for additional action or further restrictions?

Protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products

Context

Before the TVPA was put in place in 2018, vaping products with nicotine

were not legally available for sale in Canada unless they had been

evaluated for safety, quality, and efficacy under the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) and had received approval by Health

Canada. No products were authorized for sale under the FDA. Despite this

fact, vaping products were gaining in popularity and being sold in an

unregulated market, primarily through specialty vape shops.

Once the TVPA was enacted, vaping products with and without nicotine were legally permitted to be sold in Canada and are now sold in specialty vape stores, gas and convenience stores and by online retailers. The availability of vaping products at gas and convenience stores represented a major shift in the Canadian vaping product marketplace - one that substantially increased the availability of vaping products in many easily accessible locations across Canada. In 2016, prior to the TVPA, the vaping market in Canada was estimated to be worth $500 million, and gas and convenience stores accounted for $5 million (1 percent) of vaping sales. Footnote 13 In 2019, after the TVPA was enacted and nicotine-containing vaping products began to appear in gas and convenience stores, the vaping market in Canada was estimated at $1.3 billion and gas and convenience stores accounted for $400 million (30 percent) of vaping product sales. Footnote 14

Prohibiting sales to minors has proven to be effective in comprehensive tobacco control programs. This approach has been used both by the Government of Canada and provinces and territories to limit access to tobacco products. The TVPA put measures in place to protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products. Similar to restrictions on tobacco in the Act, the TVPA includes a ban on selling, sending or delivering vaping products to young persons under the age of 18.

Many provinces and territories have focused their tobacco and vaping control efforts on retail access and have taken action to go beyond the minimum requirements in the TVPA. For example, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Northwest Territories, have increased the minimum age of sale to 19, and Prince Edward Island was the first to increase the minimum age to 21, in 2019. British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario limit sales of flavoured vaping products with exceptions for some flavours to specialty stores, whereas some provinces have banned flavoured vaping products, with the exception of tobacco flavour (Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island). Finally, certain provinces (British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, Quebec, Nova Scotia) have implemented an e-cigarette retail licensing system or have guidelines for retailers in order to prevent sales to minors (Alberta, British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan). In 2019, Health Canada conducted a survey of retail establishments in Canadian cities to determine the willingness of retailers to sell vaping products to youth (15-17 years old). The survey found that 88 percent of retailers refused to sell vaping products to youth at retail locations across the country. Footnote 15

Despite the restrictions currently in place, young persons are still accessing and using vaping products. Studies suggest that many students in grades 7 to 12 (Secondary I to V in Quebec) believe that accessing vaping products would be easy. Footnote 16 Among young people, aged 15 to 19 years, who vaped in the past 30 days, the majority (57 percent) reported usually getting their vaping devices from social sources (friends or family).Footnote 17 However, despite having both federal and provincial access restrictions in place, some portion of the remaining 43 percent of young people, aged 15 to 19 years, who vape are obtaining their vaping devices from retail sources (vape shops, convenience or gas, supermarkets, grocery stores, drug stores, and online sales) despite being prohibited by legislation.Footnote 18

In April 2019, the Government of Canada consulted on potential regulatory measures to reduce youth access to, and appeal of, vaping products. Over half of the respondents were supportive of further restrictions to limit youth from accessing vaping products online. Respondents provided suggestions on how to strengthen federal access requirements. A summary of what we heard can be found here.

Building on these consultations, additional regulatory measures have been put in place, or are under development, to control flavours, online sales and nicotine content in vaping products. In response to the rise in youth vaping, the Minister of Health sent a letter to retail associations in June 2019, to remind their members of their responsibilities under the TVPA, including the prohibition on furnishing vaping products to young persons. In addition to education efforts, compliance and enforcement measures are in place to address complaints regarding access to vaping products, in collaboration with the provinces and territories. Provincial and territorial governments also have regulations in place that prohibit sales to young persons, which include enforcement provisions, and have conducted compliance verification and enforcement on access to tobacco and vaping products at retail locations. Health Canada has also implemented compliance measures to monitor and inspect youth access to vaping products and promotions online.

Questions

- Are measures in the Act sufficient to prevent youth from accessing vaping products? If not, what more could be done to restrict youth access to vaping products?

- Are there other measures that the Government could employ to protect youth from accessing vaping products?

- Has scientific evidence emerged in this area since the legislation was enacted in 2018 that points to the need for additional action or further restrictions?

Prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products

Context

As noted earlier in this document, the vaping product market has changed

significantly following the enactment of the TVPA and the entry into the

market of large multinational tobacco companies. A new generation of vaping

products that are more user-friendly (i.e. closed pod systems), smaller and

easier to conceal, contain high concentrations of nicotine, and a wide

variety of flavours quickly dominated sales. There was also a dramatic

increase in marketing on television, social media and in retail locations

to which youth were exposed.

To ensure that the public had access to accurate information in order to

make well informed decisions about vaping products, the TVPA prohibited the

promotion of vaping products that suggests that its use may provide a

health benefit or that compares the health effects of using a vaping

product versus a tobacco product. However, the Act provides the authority

to make regulations to set out permitted statements related to the health

benefits of vaping products or relative health risks of vaping products to

tobacco products. This authority would allow manufacturers and retailers to

use prescribed statements regarding the potential health benefits and

comparison statements that align with evolving scientific knowledge.

The TVPA also prohibited the manufacture, promotion and sale of products

containing ingredients that could give the impression that they have

positive health effects or were associated with vitality or energy, which

might make them attractive to youth and non-users of tobacco products.

These ingredients, including vitamins, mineral nutrients, amino acids, and

caffeine (as listed in Schedule 2 of the Act) were prohibited, except in

certain vaping products such as prescription vaping products. Other

ingredients, which could also contribute to making vaping liquids appealing

to youth, like colouring agents, were also banned. The legislation also

included regulatory authority to amend ingredient lists, and place

restrictions on the promotion of products, should future evidence indicate

that such ingredients act as inducements for young persons or non-users of

tobacco to use vaping products. The use of flavour ingredients, on the

other hand, were not restricted under the Act, but the promotion of certain

flavours (dessert, cannabis, confectionary, energy drink and soft drink

flavours), including by means of the packaging, was banned.

To prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of vaping products, along with restricting promotions that can be seen or heard by young persons, in July 2020, the government introduced requirements under Part 2 of the Vaping Products Promotion Regulations (VPPR) that prohibited vaping products from being advertised without conveying a health warning. To further protect youth, the VPPR only allows advertisement in age-restricted places that youth cannot access.

In addition, recognizing that many flavoured vaping products appeal to youth, Health Canada has proposed regulations that would restrict vaping product flavours to tobacco, mint and menthol only, through amendments to Schedules 2 and 3 of the TVPA. Several studies have found that young people, especially those who do not smoke, were more likely to initiate vaping with fruit and sweet flavours. This is aligned with data from the 2020 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey which indicates that fruit flavours are the most used flavours (64 percent) among young people, aged 15-19, who vaped in the past 30 days. Moreover, studies have shown that vaping products with flavours other than tobacco are also perceived as less harmful among youth. Consultations on the proposed regulations closed in September 2021, and feedback received is being considered. The proposed changes, if adopted, are expected to make these products less appealing to youth and non-users, while allowing some options for adults who smoke and who wish to quit and switch completely to vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine.

Finally, the TVPA provides the authority to make regulations to collect information from industry about vaping products, their emissions and any research and development (e.g., sales data and information on market research, product composition, ingredients, materials, health effects, hazardous properties and brand elements). Health Canada is currently developing proposed regulations in this area. Footnote 19

Questions

- Are the current measures in place sufficient to prevent the public from being deceived or misled about the health hazards of vaping products?

- What additional measures would help reduce the misconceptions about the health hazards of vaping products?

- Has scientific evidence emerged in this area since the legislation was enacted in 2018 that points to the need for additional action or further restrictions?

Enhance public awareness of health hazards

Context:

The TVPA includes an objective to enhance public awareness of the health hazards of vaping products so that Canadians can make informed decisions about the use of these products. In particular, the Act recognizes that vaping products present a risk to youth and those who do not use tobacco products.

Studies have linked youth vaping with known and potential health hazards associated with nicotine use and other chemicals present in vaping products. Nicotine is highly addictive and youth are especially susceptible to its negative effects, as it can alter their brain development and can affect memory and concentration. It can also lead to an addiction and physical dependence, which may occur more rapidly among children and youth than adults.

Studies suggest that there is public awareness of health hazards associated with vaping, whereas other studies point to potential knowledge gaps. Evidence suggests that most Canadian youth and non-users of tobacco are aware that there are risks associated with using vaping products containing nicotine. According to a recent survey, 42 percent of Canadian students (grades 7-12) (Secondary I to V in Quebec) indicated that using nicotine vaping products on a regular basis posed a "great risk" of harm, while 32 percent believed it posed a moderate risk.Footnote 20 Another recent survey showed that 81 percent of adult non-users of tobacco believe that nicotine vaping is moderately, very or extremely harmful.Footnote 21 For adults who smoke, there appears to be a lack of awareness that vaping products are a less harmful source of nicotine for those who currently smoke and switch completely to vaping. A 2020 survey found that only 22 percent of current smokers recognized that vaping is less harmful than smoking cigarettes.Footnote 22

To help ensure that Canadians are aware of the risks of vaping product use and nicotine addiction, in July 2020, provisions under the Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations (VPLPR) came into force requiring all vaping products to display important health and safety information. Those products containing nicotine must display the nicotine concentration and a health warning about the addictiveness of nicotine. All vaping substances must display a list of ingredients, regardless of nicotine content.

The Government of Canada has also intensified its public education and awareness efforts. Since 2018, more than $13 million has been invested in a national public education campaign called Consider the Consequences of Vaping, which was designed to educate teens and parents about the health impacts of using vaping products . The campaign targets teens aged 13-18 as well as parents of youth aged 9-18 through various media channels (Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat and others) and in a variety of public spaces (cinemas, malls, transit stations). An evaluation of the advertising campaign found that 26 percent of teens who reported having seen the ads decided not to try vaping as a result. Health Canada also launched an experiential tour of schools and community events across Canada where additional information on the health impacts of vaping could be shared with youth, either in person or virtually.

To better understand youth vaping trends and the reasons for use, the Government of Canada has invested $7.1 million since 2018 in research and surveillance activities, including market, science and public opinion research with a view to better targeting its vaping prevention and cessation interventions for youth.

Questions

- Have public awareness efforts been effective at educating Canadians about the health risks of vaping products?

- What more could be done to educate Canadians about the health risks of vaping products?

- Are there still knowledge gaps to fill with regard to the health risks of vaping products? If so, what areas should research focus on?

- What approach should be taken to close the gap between scientific evidence and public perception so that youth and non-users of tobacco products are aware of the health risks of using vaping products, while adults who smoke are aware that they are a less harmful alternative to tobacco if they switch completely to vaping?

Conclusion

The vaping products market in Canada has changed significantly over the three years that the TVPA has been in force. This review represents an opportunity to examine the legislation and assess progress in meeting its objectives. This includes whether the authorities under the TVPA are sufficient to address any issues and concerns as they arise, such as the rise in youth vaping. For these reasons, the focus of the first review of the TVPA are on the vaping provisions of the Act.

As this paper details, since the TVPA was implemented, the government has responded to the rise in youth vaping by exercising regulatory authorities, which were included in the legislation, that were designed to address challenges that might arise in the context of an emerging product and rapidly evolving market, and about which there was limited scientific evidence. In particular, the government has taken action to strengthen controls on access, restrict advertising, and place restrictions on the composition of the product as it relates to nicotine and flavours.

This first review of the TVPA is being undertaken after only three years of operation, in the context of limited new data, compounded by the unusual circumstances brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. A full assessment of whether the measures taken since the legislation was introduced in 2018 have been effective in responding to the rise in youth vaping will benefit from more time and data. Subsequent reviews will continue to monitor youth use along with other dimensions of the Act.

In closing, Canadians are also welcome to provide their views on these three questions about the legislation and the review provisions therein:

- Is there anything else that you would like to add as it relates to any of the topics covered in this discussion paper?

- Are there any gaps in the authorities under the operation of the Act, or the vaping-related provisions, that you believe should be addressed?

- Do you have suggestions for what could be included in future reviews of the TVPA?

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Scientific Working Group. (2020). Canadian substance use costs and harms 2015-2017. (Prepared by the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.) Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

- Footnote 2

-

General Social Survey (GSS) 1985. Statistics Canada.

- Footnote 3

-

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2020. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0096-10 Smokers, by age group. The survey can be accessed here: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009601

- Footnote 4

-

Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) 2017. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html

- Footnote 5

-

Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) 2017. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html

- Footnote 6

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2019. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2019-summary.html

- Footnote 7

-

Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) 2013, 2015, 2017 / Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey 2019, 2020

- Footnote 8

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2020.

- Footnote 9

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2020.

- Footnote 10

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2020.

- Footnote 11

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) results can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey.html

- Footnote 12

-

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) results can be accessed here: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210917/dq210917e-eng.htm

- Footnote 13

-

Euromonitor International. Study of the Market Size and Growth Trends of Nicotine-based Vaping Products Market in Canada 2017. A custom report compiled for Health Canada.

- Footnote 14

-

Euromonitor International. Study of the Market Size, Characteristics and Growth Trends of the Vaping Products Market in Canada 2020. A custom report compiled for Health Canada.

- Footnote 15

-

Ipsos LP, We Check. Retailer Behaviour re: Youth Access to Electronic Cigarettes and Promotion Report 2019. A custom report compiled for Health Canada.

- Footnote 16

-

Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) 2018-19. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2018-2019-summary.html

- Footnote 17

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2019. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2019-summary.html

- Footnote 18

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2019. The survey can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-nicotine-survey/2019-summary.html

- Footnote 19

-

Health Canada's Forward Regulatory Plan 2021-2023: Vaping Products Reporting Regulations. The regulations can be accessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/legislation-guidelines/acts-regulations/forward-regulatory-plan/plan/vaping-reporting.html

- Footnote 20

-

Health Canada, Summary of results for the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey 2018-19, Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2018-2019-summary.html

- Footnote 21

-

Earnscliffe Strategy Group (2020), Social Values and Psychographic Segmentation of Tobacco and Nicotine, Retrieved from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/sc-hc/H14-345-2020-1-eng.pdf

- Footnote 22

-

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) 2020.