The second legislative review of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act Discussion Paper

Download in PDF format

(1.44 MB, 40 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: September 2023

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Discussion Themes

- Theme 1: Canada's tobacco landscape

- Theme 2: Addressing inducements to tobacco use.

- Theme 3: Monitoring the tobacco market

- Theme 4: Restricting youth access to tobacco products

- Theme 5: Enhancing awareness and preventing Canadians from being deceived or misled

- Theme 6: Compliance, enforcement and regulated parties

- Theme 7: Engaging with Indigenous Peoples

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: Discussion Questions

- Endnotes

Introduction

Canada has a long history of tobacco control. Tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of premature death in Canada,Footnote 1 with approximately 46,000 people dying from tobacco-related illnesses every year.Footnote 2 While tobacco use has decreased over the years, a significant number of people in Canada are smoking (12% or 3.8M)Footnote 3, and more work remains to be done.

Canada introduced new measures to regulate tobacco and vaping products and a new tobacco control strategy in 2018. The Tobacco Act (TA) of 1997 was amended and renamed the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA) and Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS) was launched to address tobacco use in Canada. Canada's Tobacco Strategy sets an ambitious target to reduce the prevalence of tobacco use to less than 5 percent by 2035, to reduce the staggering death and disease burden of tobacco use.

To achieve this target, CTS aims to prioritize helping Canadians quit tobacco, protect youth and people who do not use tobacco from nicotine addiction, support Indigenous organizations to develop and implement self-led distinct approaches to reducing commercial tobacco use, and strengthen science, surveillance, and partnerships.

Successful implementation of CTS depends on strong collaboration and coordinated efforts between the Government of Canada and a number of partners including Indigenous groups, other orders of government, non-profit organizations, health professionals, and academics. Jurisdiction over health-related matters such as tobacco control is shared between the federal, provincial, and territorial governments in Canada, and therefore, provinces and territories are vital partners. International cooperation is also important to respond to the globalization of the tobacco epidemic, both in Canada and abroad. Canada is a Party to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), which aims to protect present and future generations from the devastating health, social, environmental, and economic consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke. To date, Canada has implemented most of the WHO FCTC's tobacco control measures.

Federal legislation is one of several tools used to advance CTS and protect Canadians from tobacco-related death and disease. The TVPA regulates the manufacture, sale, labelling and promotion of tobacco and vaping products. The TVPA's overall purpose is to provide a legislative response to a national public health problem of substantial and pressing concern and to protect the health of Canadians in light of conclusive evidence implicating tobacco use in the incidence of numerous debilitating and fatal diseases.

The TVPA includes a requirement to review its provisions and operation three years after the day on which it came into force, and every two years after that. The first review, completed in December 2022, focused on the vaping-related provisions of the TVPA. The analysis undertaken as part of the review, along with the input received from consultations confirmed that, in general, the TVPA appeared to be making progress towards achieving its vaping-related objectives, but also identified areas for potential action including: examining access to vaping products by youth; communicating the health hazards of vaping along with the potential benefits as a less harmful source of nicotine for people who smoke and completely stop; strengthening compliance and enforcement; and addressing scientific and product uncertainty to better understand the vaping product market and health impacts of vaping. Complete findings of the first review can be found in the Report of the First Legislative Review of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act.

This review, the second legislative review of the TVPA, will focus on the tobacco-related provisions and operation of the TVPA. Specifically, it will assess whether progress is being made towards achieving the tobacco-related objectives of the TVPA and whether the federal response, from a legislative perspective, is sufficient in addressing tobacco use in Canada. This review will serve to complement the first review on vaping products and together provide a baseline assessment of the TVPA.

The TVPA defines a tobacco product as "a product made in whole or in part of tobacco, including tobacco leaves. It includes papers, tubes and filters intended for use with that product, a device, other than a water pipe, that is necessary for the use of that product and the parts that may be used with the device". Examples of tobacco products include cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, leaf tobacco, pipe tobacco, tobacco sticks, chewing tobacco, snuff, kreteks, bidis, little cigars, cigars, or any product made in whole or in part of tobacco that is intended to be used with a device. While "vaping products" (also known as "e-cigarettes") may contain nicotine, which is naturally occurring in tobacco, they do not contain tobacco. As such, vaping products are not considered "tobacco products" as defined by the TVPA and were considered in the first TVPA review and are not subject to this current review.

Tobacco products are regulated under several pieces of legislation in Canada. Some stakeholders may wish to provide feedback related to the regulation of tobacco or nicotine that falls under other pieces of federal legislation such as the Canadian Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), the Food and Drugs Act, the Excise Act, 2001 and the Non-smoker's Health Act or other key tobacco priorities such as the illicit market. Although these topics will not be examined within the scope of this review, relevant feedback will be shared with the appropriate departments as necessary.

We want to hear from you

A key part of this legislative review is seeking the perspectives of Canadians, experts, and other stakeholders as they relate to the TVPA, with a particular emphasis on how to reduce tobacco use in Canada to help better protect Canadians from tobacco-related illness.

We want to hear your ideas, your experiences, and your perspectives through this public consultation. You are also encouraged to submit any evidence that you may have to support your input. To assist in providing a submission, a list of key questions has also been provided in the discussion paper (Appendix A). This list is not exhaustive and any input relating to tobacco regulation under the TVPA is welcome.

You may participate by sending your written submission by November 17, 2023 to: legislativereviewtvpa.revisionlegislativeltpv@hc-sc.gc.ca

Please note: you must declare any perceived or actual conflicts of interest with the tobacco industry when providing a submission to this consultation. If you are part of the tobacco industry, an affiliated organization or an individual acting on its behalf, you must clearly state so in your submission.

Health Canada is also interested in being made aware of perceived or actual conflicts of interest with the vaping industry or pharmaceutical industry. Therefore, please declare any perceived or actual conflicts of interest, if applicable, when providing input. If you are a member of the vaping industry, pharmaceutical industry, an affiliated organization or an individual acting on their behalf, you are asked to clearly state so in your submission.

Please do not include any personal information when providing your input. Government of Canada will not be retaining your e-mail address or contact information when receiving your submission and will only retain the comments you provide.

Submissions will be summarized in the legislative review's final report, although comments will not be attributed to any specific individual or organization. The final report will be tabled in Parliament and made public on Canada.ca at that time.

Discussion Themes

The TVPA is the federal legislation that protects the health of Canadians from tobacco-related death and disease. The TVPA also supports four specific objectives related to tobacco products, which are:

- to protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them;

- to protect the health of young persons by restricting access to tobacco products;

- to prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using tobacco products

- to enhance public awareness of those hazards.

The TVPA provides, among other things, the authority for Health Canada to regulate the manufacture, sale, labelling, and promotion of tobacco products. Tobacco products are allowed on the Canadian market if they meet the requirements of the TVPA and its regulations, and any other piece of legislation to which tobacco products are subject.

Along with federal laws and regulations, each province and territory also has laws and regulations in place for tobacco control. These work together to protect Canadians from tobacco use. Federal regulations establish the minimum uniform prohibitions and restrictions that apply across Canada, and provinces and territories create laws that are intended for their jurisdiction. Some examples of provincial and territorial regulations include restrictions on sales to youth; tobacco-free schools and school grounds; anti-tobacco social marketing campaigns; and rules for smoke-free spaces.

This legislative review will examine whether the federal legislative response is sufficient in addressing tobacco use in Canada and will assess whether progress is being made towards achieving the TVPA's tobacco-related objectives.

The discussion paper is framed around seven major themes. These themes are:

- Canada's tobacco landscape;

- Addressing inducements to tobacco use;

- Monitoring the tobacco market;

- Restricting youth access to tobacco products;

- Enhancing awareness and preventing Canadians from being deceived or misled;

- Compliance, enforcement and regulated parties; and

- Engaging with Indigenous Peoples

Theme 1 sets out the health effects related to tobacco use and speaks to some of the key priorities and challenges regarding tobacco use in Canada. Themes 2 to 5 relate to tobacco provisions of the TVPA and theme 6 relates to the operation of the TVPA. Theme 7 highlights Canada's commitment to engaging with Indigenous Peoples.

The paper will examine each of the themes listed above and provide a summary of the current context including a description of federal government initiatives. It will also pose questions to solicit input on what is working well and what could be improved in the future.

Theme 1: Canada's tobacco landscape

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of premature death in Canada and kills more than 46,000 Canadians every year; that is about one Canadian every 11 minutes.Footnote 4 Smoking, the most common form of tobacco use, has been linked to a number of diseases and health conditions and is harmful for both the person who smokes and bystanders. Smoking-related diseases include heart disease, stroke, certain types of cancer, lung and respiratory problems such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that includes emphysema, chronic bronchitis and asthmatic bronchitis. It has also been linked to health issues such as infertility, impotence/erectile dysfunction, premature births and having a low birth weightFootnote 5. Tobacco smoke contains over 7,000 chemicals in the form of gases and particles, including more than 70 known carcinogens.Footnote 6 Beyond the physical health effects that come from using tobacco products, people who smoke may also be stigmatized by friends, family, and peers. Stigma has both health and social consequences and can be a barrier for help-seeking and cessation.Footnote 7

The purpose of the TVPA is to protect the health of Canadians in light of conclusive evidence implicating tobacco use in the incidence of numerous debilitating and fatal diseases. The TVPA and its regulations are intended to contribute to addressing Canada's public health problem of tobacco use.

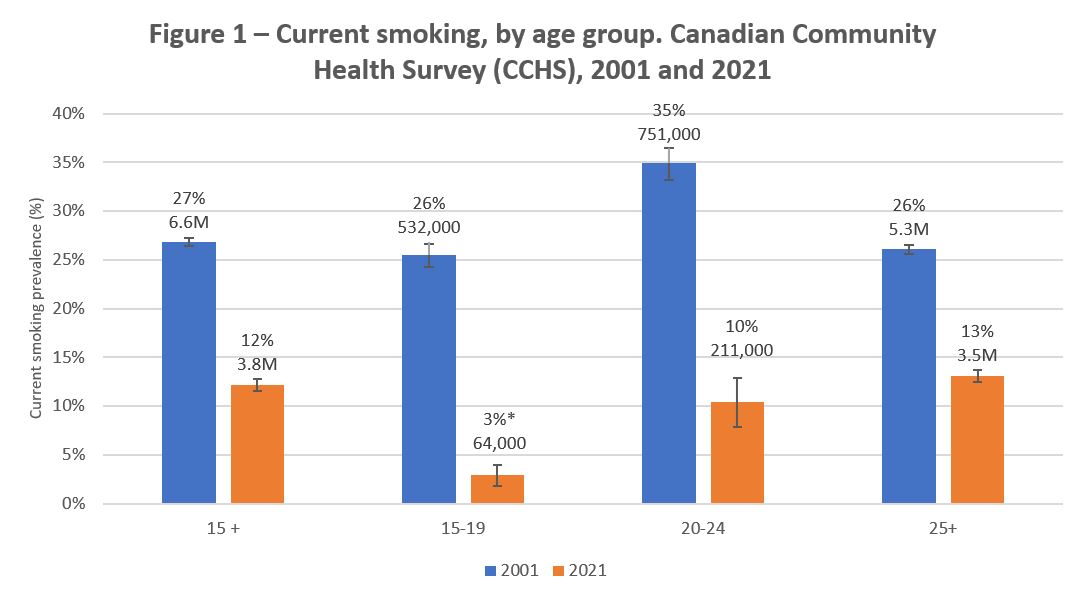

Over the years, surveys have shown large declines in the number of people who use tobacco products in Canada. As shown in Figure 1, smoking rates, which were 27 percent (6.6M) in 2001 are now 12 percent (3.8M) in 2021. While decreases over time have been observed among all age groups, youth smoking rates are at an all-time low.

Figure 1 - Text description

| Current smoking prevalence | 2001 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| 15 years and older | 27% (6.6M) | 12% (3.8M) |

| 15 to 19 years | 26% (532,000) | 3%* (64,000) |

| 20 to 24 years | 35% (751,000) | 10% (211,000) |

| 25 years and older | 26% (5.3M) | 13% (3.5M) |

Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2001 and 2021. (Note: Does not include rates for First Nations People living on reserve, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, the institutionalized population, among other sub-groups)

* Moderate sampling variability, interpret with caution.

However, despite significant declines in smoking prevalence among Canadians, there are still communities and regions which are disproportionately impacted by smoking in Canada. The Canadian Community Health SurveyFootnote 8 shows that some groups of Canadians aged 15 and older have higher smoking rates:

- 58% of those living in Nunavut, 26% of those living in Northwest Territories and 20% of those living in Newfoundland and Labrador (versus 10% in British Columbia and 12% in Ontario)

- 24% of construction workers (versus 9% in educational services)

- 22% of Canadians who identify as homosexual, and 20% who identify as pansexual or bisexual (versus 13% who identify as heterosexual)

- 21% of Canadians who have a mood and/or anxiety disorder (versus 12% of those who do not have a mood nor anxiety disorder)

- 19% of Canadians in the lowest household income quintile (versus 8% of those in the highest household income quintile)

- 18% of Canadians with less than a secondary education (versus 7% of those with a university degree or more)

- 16% of males (versus 11% of females)

Indigenous Peoples, particularly Inuit, have among the highest smoking rates of any population group in Canada. Indigenous-led or Indigenous-specific surveys provide for better representation and demonstrate this disproportionality. For First Nations on-reserve, the First Nations Institute on Governance leads the Regional Health Survey (RHS). This is the first, and only, national First Nations health survey, and it collects wide-ranging information about First Nations people living on-reserve and in northern communities. The Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) is a national survey of First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit aged 15 years and over. These surveys found the following smoking rates:

- 46.5% of First Nations on-reserve aged 18 years and older reported that they did not currently smoke cigarettes, 40.3% reported smoking cigarettes daily, and 13.1% reported smoking occasionally (RHS 2015-16)

- 27.1% of First Nations off-reserve smoke daily, and 9.7% smoke occasionally (APS 2017)

- 66.9% of Inuit in Inuit Nunangat reported smoking daily, and 5.9% smoked occasionally (APS 2017)

- 30% of Métis reported current smoking (APS, 2017)

The discrepancy between overall Canadian smoking rates and that of certain groups of Canadians is longstanding and has been observed for decades. It is important that interventions for commercial tobacco control not only succeed in decreasing smoking prevalence rates, but ideally also be equity-enhancing for those groups with high prevalence of use.

Dependence

Nicotine is the highly addictive substance found in tobacco products. The WHO FCTC states that cigarettes and some other tobacco products are engineered to create and maintain dependence.Footnote 9 Anyone who uses tobacco products is at risk of becoming dependent on nicotine.

Nicotine may cause the user to temporarily feel good, energized, more alert or calm. Over time, the body builds a tolerance to some of the effects of nicotine, resulting in a need to continue to use nicotine to make the effects last. Going without tobacco for more than a few hours may lead to withdrawal symptoms.

When a person smokes, nicotine is absorbed through the lungs and then moves through the bloodstream and into the brain within seconds.Footnote 10Footnote 11 Nicotine can cause heart rate and blood pressure to increase, blood vessels to constrict, alter brain waves and relax muscles.Footnote 12 Long-term exposure to nicotine can lead to changes in the brain and addiction.Footnote 13 Among youth and young adults, nicotine exposure can reduce impulse control, lead to attention and cognitive issues, and increase the risk of mood disorders such as major depressive disorder, panic disorder, or antisocial personality disorder.Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18 Because the brain continues to develop through adolescence and into early adulthood,Footnote 19 youth are especially susceptible to the effects of nicotineFootnote 20 and may become dependent with lower levels of exposure than adults.Footnote 21 Nicotine itself is not known to cause cancer;Footnote 22 it is other chemicals that result from combustion (burning) of tobacco products like tar, benzene and formaldehyde that are largely responsible for health effects.Footnote 23Footnote 24 Still, nicotine is responsible for cravings and withdrawal symptoms, which make quitting tobacco products difficult.Footnote 25

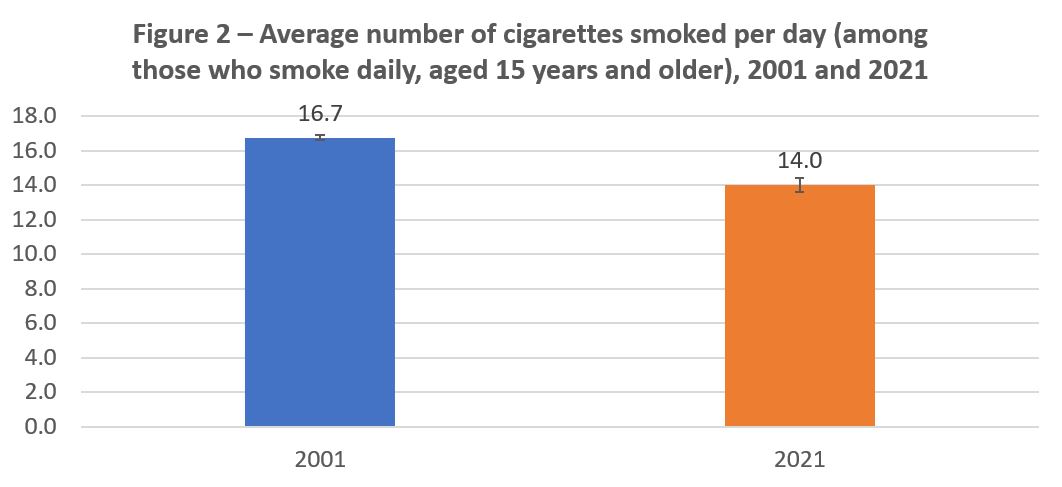

Nicotine dependence is a function of many risk factors, including genetics, environment, existing mental health problems, and existing substance use disorders, as well as the amount and the speed of nicotine delivery.Footnote 26 The most common marker of tobacco or nicotine addiction is the number of cigarettes smoked per day (smoking frequency).Footnote 27 As shown in Figure 2, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day (by those who smoke daily) in 2001 was 16.7 compared to 14 in 2021.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Age | 2001 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| 15 years and older | 16.7 | 14.0 |

Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2001 and 2021.

Cessation

Quitting smoking is the best thing those who smoke can do to improve their health.Footnote 28 Many of the health effects linked to tobacco use can be reversed or reduced after a person quits smoking. The body starts to recover from the effects of smoking as early as the first day of quitting.Footnote 29 There are health benefits from quitting for all people who smoke (regardless of age or sex). Even those already living with a smoking-related chronic health condition like cancer can benefit from quitting and improve their health outcomes and the effectiveness of their treatment.Footnote 30 Quitting also lowers the chance that people around them will have health problems from second-hand smoke.Footnote 31Footnote 32

A Public Opinion Research study conducted in 2022 indicates that among Canadians aged 15 and older who currently smoke, about half reported that quitting was important to them.Footnote 33 Quitting smoking is challenging and often requires multiple attempts. In 2015, Canadians who reported formerly smoking made on average 4.3 quit attempts before quitting cigarette smoking for good.Footnote 34

The Government of Canada has implemented several regulatory initiatives to protect the health of Canadians from the health hazards of using tobacco products. For example, the Government of Canada recently announced amendments to the tobacco labelling requirements, which introduce new measures, such as the requirement for health warnings on individual cigarettes, and consolidate all tobacco product appearance, packaging and labelling requirements into the new Tobacco Products Appearance, Packaging and Labelling Regulations. The regulations require that a pan-Canadian toll-free quitline number and link to a cessation website be displayed with the health warnings on tobacco product packages. They also require the display of health information messages, often found inside some tobacco packages (e.g., cigarettes, little cigars and cigarette tobacco), which highlight the benefits of quitting and provide tips on smoking cessation as well as include the quitline number and cessation website. The display of health warnings on tobacco product packages directly communicates the health hazards of tobacco use to people who use tobacco products while promoting smoking cessation.Footnote 35

Canadians who wish to quit smoking can receive support and information about quitting options from trained specialists by calling the toll-free quitline. By placing this information on and inside tobacco packages, individuals who use the products are reminded of cessation services every time they look at the pack, and the information is readily available when they are thinking about quitting.

Questions:

- What are the factors that lead to tobacco use? Please provide any data or evidence to support your response.

- Are there new measures or adjustments to current measures that the Government of Canada could consider to better support smoking cessation efforts?

- Are there any international approaches that have proven to be successful in cessation efforts that the Government of Canada should be studying and adopting?

- Are there legislative measures that could be considered to address the public health problem posed by tobacco use in groups disproportionately affected by tobacco? If so, how could the legislation better address these disparities?

Theme 2: Addressing inducements to tobacco use

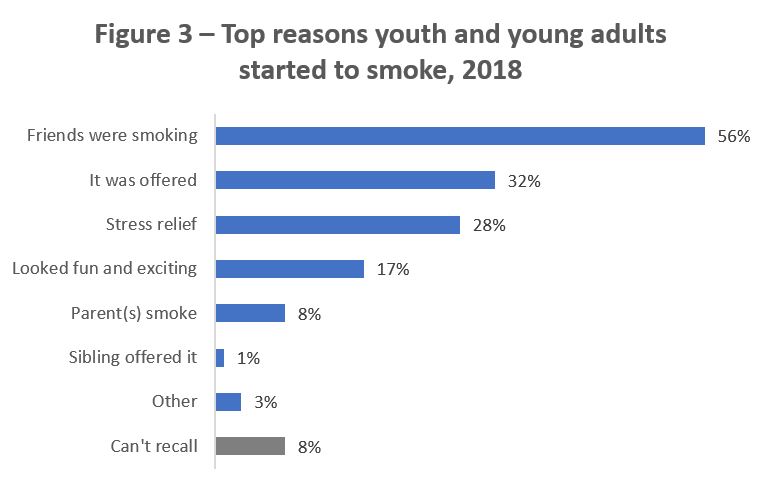

Most tobacco use begins during adolescence. In 2021, 70 percent (2.6 million) of people who currently smoke reported smoking their first whole cigarette before the age of 18, 24 percent (918,000) between the ages of 18 and 24 and 6 percent (222,000) over the age of 25.Footnote 36 Although people typically start smoking during adolescence, much fewer youth (3 percent; 64,000) reported smoking in 2021 compared to 2001 (25 percent; 532,000) (moderate sampling variability, interpret with caution).Footnote 37

A Public Opinion Research study conducted in 2018 provides insight into the reasons a sample (approximately 200) of Canadian youth and young adults aged 13 to 24 reported starting to smoke, with the vast majority indicating that the reason for starting was because their friends were smoking.Footnote 38

Figure 3 - Text description

| Why did you first start smoking cigarettes? | Youth and young adults who smoke (n= 196) |

|---|---|

| Friends were smoking | 56% |

| It was offered | 32% |

| Stress relief | 28% |

| Looked fun and exciting | 17% |

| Parent(s) smoke | 8% |

| Sibling offered it | 1% |

| Other | 3% |

| Can't recall | 8% |

Source: Peer Crowd Analysis and Segmentation for Vaping and Tobacco

Product Promotion

Tobacco product promotions are intended, among other things, to create and maintain the perception that tobacco use is desirable, socially acceptable, healthy and more common in society than it really is. This positive perception of tobacco use through tobacco product promotion reassures people about smoking. That is why the TVPA includes a broad and comprehensive approach to addressing promotional activities that could influence people to begin using tobacco products.

The TVPA sets out a general prohibition on the promotion of tobacco products or tobacco-related brand elements with specific prohibitions and exceptions. This general prohibition is required in order for legislation to keep pace with changing marketing practices in tobacco product promotion.

The following are examples of specific prohibitions dealing with tobacco-related promotional activities under the TVPA:

- Sponsorship promotion of a tobacco product-related brand element or the name of a tobacco product manufacturer. As well as the display of such brand elements or names on a permanent facility used for sports or cultural events or activities.

- Providing any consideration, including a gift, any bonus, premium, cash rebate, right to participate in a game, draw, lottery, etc. to a purchaser of a tobacco product.

- Comparative claims in promotion that suggest a tobacco product or its emissions is less harmful than another or makes claims related to health effects or health hazards.

- Testimonials and endorsements of tobacco products.

- Publishing, broadcasting or otherwise disseminating, on behalf of another person, prohibited promotion, for example, through media; except for imported publication or the retransmission of radio or television broadcasts that originate outside Canada.

- Flavouring additives in, among others, cigarettes, little cigars and blunt wraps, with the following exceptions:

- Cigars that have a wrapper fitted in spiral form and weighing between 1.4 g and 6 g that are port, wine, rum, or whiskey flavoured; and

- Products that are manufactured or sold for export.

- Promotion of a tobacco product by means of advertising, with the exception of information and brand-preference advertising in a publication addressed and sent to an adult who is identified by name or on a sign in a place where young persons are not permitted by law.

Following earlier restrictions on promotional activities and sponsorship, promotion by means of packaging was one of the few remaining channels available for the promotion of tobacco products in Canada and the only promotional outlet for reaching youth. Tobacco packages have a high degree of social visibility as they are frequently on display each time the product is used or shared with others.

In 2019, the Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance)Footnote 39 were brought into force to standardize the appearance of tobacco packages and products to make them less appealing, particularly to youth and young adults. The colour, size and shape of all tobacco product packages are now standardized, bearing only the permitted text displayed in a standard location, font style, colour and size. Tobacco products are also plain in their appearance, bearing only the permitted text in the prescribed location, font style, colour and size. Cigarette dimensions and the diameter of little cigars are also standardized. These regulations were put into place to restrict the use of novel packaging to make tobacco products more appealing to youthFootnote 40 and to create an association with a number of positive attributes, such as glamour, sleekness, and attractiveness.Footnote 41Footnote 42 Youth are considered especially impressionable and more vulnerable to inducements to use tobacco products, such as advertising, as this is the age when brand loyalty and smoking behaviour begin to be established.Footnote 43 The regulations also standardize the appearance of cigarettes, which was also shown to strongly influence smoking initiation.Footnote 44 Industry documents suggest that cigarettes had been modified to appeal to specific segments of the population, including both young adults and women,Footnote 45 ultimately increasing sales and market share.Footnote 46Footnote 47 For example, cigarette appearance was modified to used floral and satin tipping paper to target females.Footnote 48

Finally, to keep pace with changing marketing practices in tobacco product promotion the Tobacco Reporting Regulations require manufacturers to submit information on promotional activities.

Questions:

- Are the prohibitions within the TVPA and requirements in its regulations sufficient to protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them? If not, what more could be done?

Theme 3: Monitoring the tobacco market

In order to have timely and relevant information about the tobacco market, the TVPA provides the authority to monitor the tobacco market in Canada through regulation. The Tobacco Reporting Regulations (TRR) set out the requirements for the reporting of information on, among other things, the sales data, as well as research and development activities undertaken by tobacco manufacturers. The TRR requires information be submitted for certain types of tobacco product types listed in the regulations such as cigarettes, leaf and cigarette tobacco, little cigars, cigars, pipe tobacco and smokeless tobacco. The TRR does not currently require reports for waterpipe tobacco, heated tobacco products, blunt wraps or for any novel type of tobacco product that could be introduced in the future. It also does not require any sales reports on cigarette papers or filters sold separately to make cigarettes or any devices used to consume tobacco.

Information collected by Health Canada under the TRR has been used to inform various policy decisions and the implementation of effective tobacco control strategies to protect the health of Canadians. A summary of the Canadian market is provided below, using the information collected under the TRR.

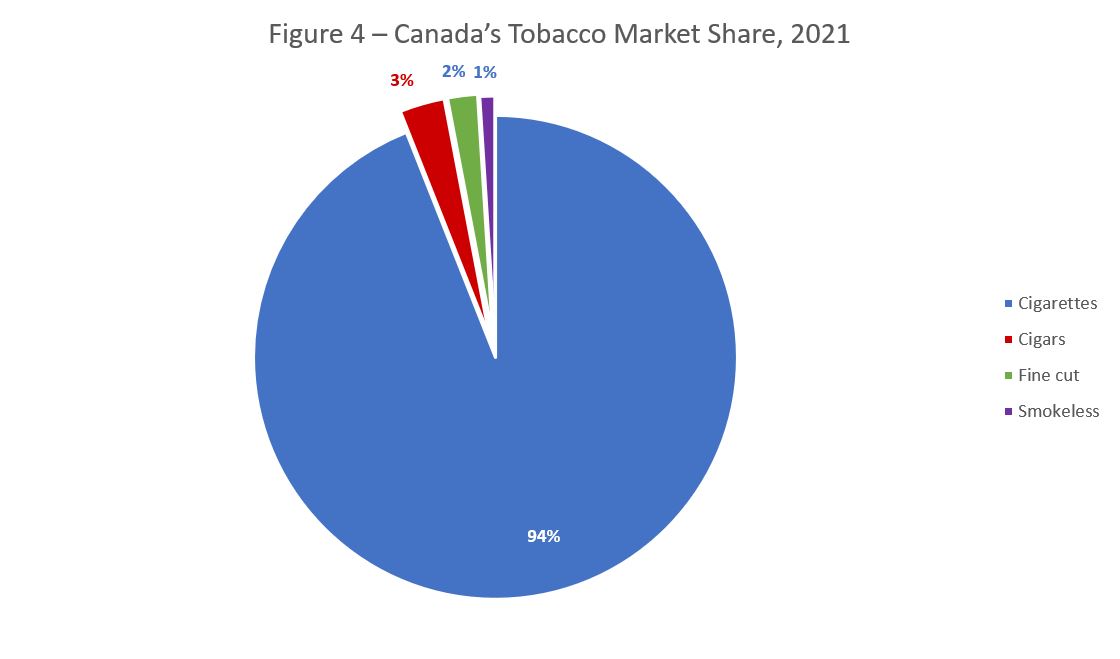

Tobacco Market in Canada

Cigarettes are the most commonly sold tobacco product in Canada. As indicated in Figure 4 below, cigarettes represented 94 percent of the total tobacco market share whereas cigars, fine cut tobacco (e.g., cigarette tobacco to roll your own cigarettes) and smokeless (e.g., chewing tobacco, oral snuff and nasal snuff) accounted for approximately 6 percent of the tobacco market value in 2021.Footnote 49

Figure 4 - Text description

| Cigarettes | 94% |

| Cigars | 3% |

| Fine cut | 2% |

| Smokeless | 1% |

Source: Health Canada, Tobacco Reporting Regulations

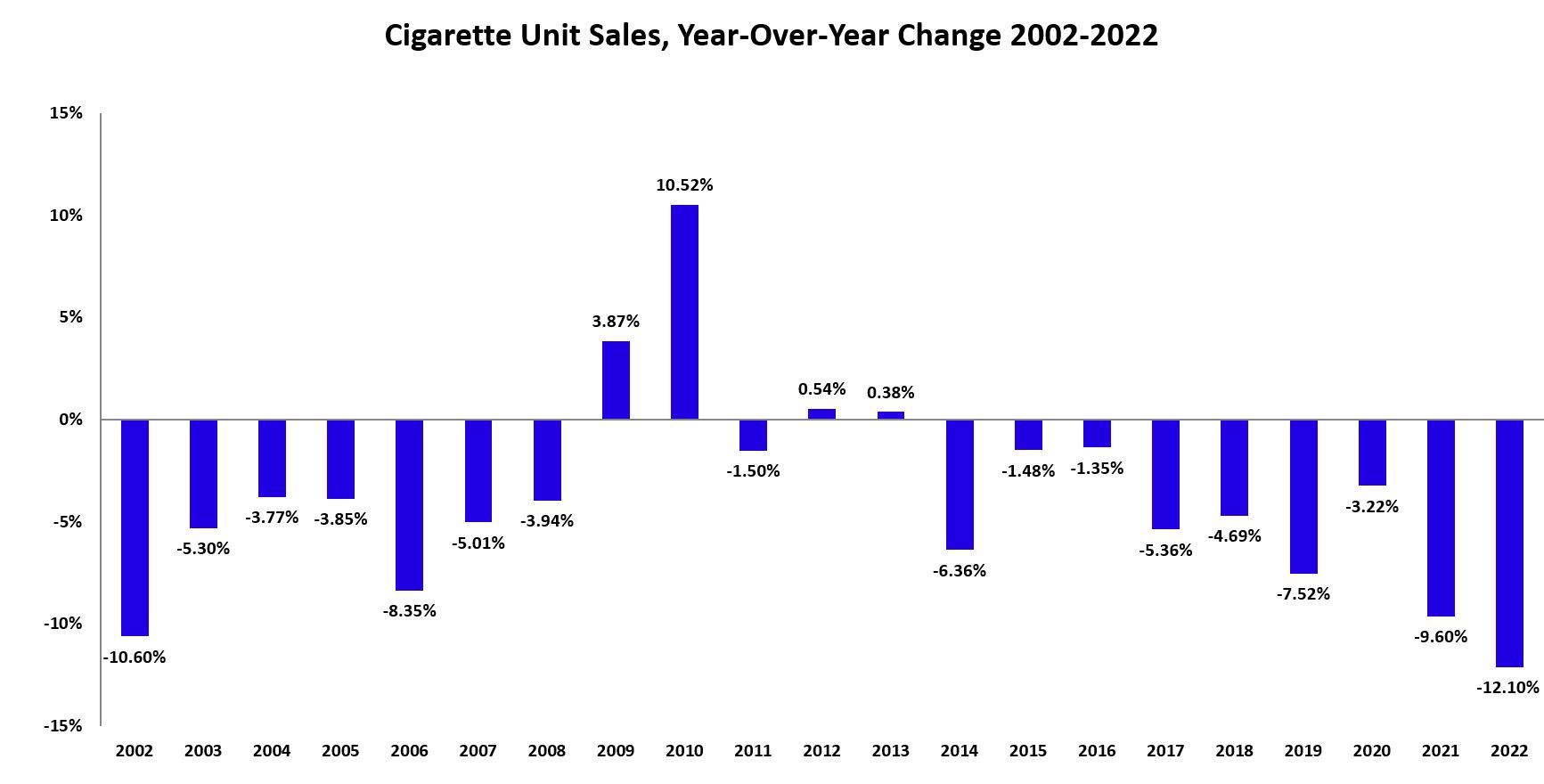

While cigarettes continue to make up most of the market, the number of industry-reported cigarettes sold in Canada declined by almost 42 percent from 2013 to 2022. Two-thirds of that decline occurred since 2018, the year the TVPA was implemented and vaping products with nicotine were legalized in Canada. Moreover, as shown in Figure 5 below, the 2021 (-9.6%) and 2022 (-12.1%) declines were the largest year-over-year declines observed in Canada in more than 20 years. Despite this decline in cigarette sales, industry revenue from tobacco products have increased as a result of tobacco companies voluntarily increasing the prices of cigarettes. As of 2022, tobacco industry revenue for cigarettes was estimated at $4.05 billion, representing a 45 percent increase since 2013.

Figure 5 - Text description

| Years | Percentage | Baseline | Percentage Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | -10.60% | 0% | 15% to -15% |

| 2003 | -5.30% | ||

| 2004 | -3.77% | ||

| 2005 | -3.85% | ||

| 2006 | -8.35% | ||

| 2007 | -5.01% | ||

| 2008 | -3.94% | ||

| 2009 | 3.87% | ||

| 2010 | 10.52% | ||

| 2011 | -1.50% | ||

| 2012 | 0.54% | ||

| 2013 | 0.38% | ||

| 2014 | -6.36% | ||

| 2015 | -1.48% | ||

| 2016 | -1.35% | ||

| 2017 | -5.36% | ||

| 2018 | -4.69% | ||

| 2019 | -7.52% | ||

| 2020 | -3.22% | ||

| 2021 | -9.60% | ||

| 2022 | -12.10% |

Source: Tobacco Reporting Regulations Section 13, Health Canada

There has also been a dramatic decline in sales for cigars, fine-cut tobacco, and pipe tobacco over the last decade. Cigar sales have declined by more than 50 percent since a 2009 high of 650 million, while fine-cut tobacco has seen a 60 percent decline in sales in the last decade. Pipe tobacco sales declined by 47 percent over the last decade. Smokeless tobacco sales have declined at a steadier rate (30%) in the last decade, after having peaked at 333 000 kilograms in 2012.

Generally, tax and price increases of tobacco products can have a strong impact on tobacco use, particularly youth.Footnote 50 Research shows that significantly increasing tax and price is the single most consistently effective tool for reducing tobacco use; it can lead some to quit or reduce their consumption, or can prevent people from starting to use tobacco altogether.Footnote 51

Questions

- Are there additional sources of information that could be collected to improve monitoring the tobacco market in Canada? If so, what are they?

Theme 4: Restricting youth access to tobacco products

Preventing youth from accessing tobacco products has been a tobacco control priority since the early 1990s. The TVPA prohibits furnishing tobacco products to persons under 18 years of age, establishing the uniform minimum protection for youth across Canada. The Tobacco (Access) Regulations set out the types of documentation that may be used to verify the age of a person wanting to purchase tobacco products. Also, the TVPA does not permit sending or delivering a tobacco product to anyone under 18 years of age. This prohibition addresses online sales and other forms of distance sales that are now available for consumer goods. The TVPA extends the responsibility of taking appropriate measures to restrict youth access to tobacco products to everyone involved in the transaction.

To help strengthen and avoid undermining provincial and territorial tobacco control measures, such as taxation schemes, the TVPA also prohibits sending or delivering tobacco products between provinces, or even advertising and/or offering such a service – although exemptions are made for transactions between manufacturers and retailers. In terms of sales and importations, there are requirements on the minimum number of cigarettes, little cigars or blunt wraps that a package must contain. The higher price associated with the larger package acts as a disincentive to purchase by young persons who have limited funds.

Sale of tobacco products through dispensing devices (i.e., vending machines) are not permitted under the TVPA unless the dispensing device is located in a place where the public does not reasonably have access or is an age-restricted venue such as a bar, tavern or beverage room. Similarly, the sale of tobacco products by means of a self-service display that allow a person to handle a tobacco product before paying for it are also not permitted under the TVPA, except for duty-free shops. These restrictions aim to prevent access to young persons and to allow for age verification.

The protection of health is a shared jurisdiction in Canada. It can therefore be addressed by federal, provincial, or territorial legislation, depending on the nature of the issue in question, such as tobacco. While the TVPA's prohibitions and requirements establish the minimum uniform standards that apply across Canada, provinces and territories may adopt legislation on the same matters. Thus, some provinces have established a minimum legal age to be sold tobacco and vaping products higher than the age of 18 established by the TVPA. Furthermore, all provinces and territories rely on the use of a range of tools to protect youth, including implementing their own tobacco legislation. Depending on the jurisdiction, these tools include restrictions on sales to youth; prohibitions on flavoured tobacco, tobacco display bans; signs displaying the prohibition on sales to youth; tobacco-free school grounds, school and sports-based education programs; programs for at-risk youth and pregnant people; and anti-tobacco social marketing campaigns. All provinces and territories and many municipalities have rules for smoke-free spaces.

Where and how people purchase tobacco products has changed over the decades. Prior to the year 2000, cigarettes were sold just about anywhere – restaurants/food venues, bars, hotels, movie theatres, department stores, corner stores and other retail outlets. Today, due to provincial and territorial laws, they have virtually disappeared from all hospitality venues and from all retail outlets other than convenience stores, grocery stores, gasoline stationsFootnote 52 and specialty shops. The density of tobacco retailers has also fallen over the years, with 383 outlets per 100,000 people in 1976, to 130 outlets per 100,000 Canadians in 2000, to 75 outlets per 100,000 people in 2019.Footnote 53 There are approximately 30,000 to 35,000 retail stores across Canada where cigarettes are available for sale.Footnote 54 Ease of access can have an impact on tobacco use, as many studies have showed that lower levels of retail density and decreased proximity to tobacco retailers are associated with less tobacco use.Footnote 55 It has also been noted that the number of tobacco retailers surrounding a school has been linked to increased odds of youth taking up smoking.Footnote 56 But compared to most countries, Canada has less retail density than others.Footnote 57

Even with federal and provincial/territorial restrictions on product access, most Canadian youth feel it would be easy to get a cigarette if they wanted one.Footnote 58 Social sources are the primary source of youth access to tobacco, with 76 percent (58,000) of Canadian youth (students in grades 7 - 12) who smoked in the past 30 days obtaining their cigarettes from social sources such as friends and family, while 24 percent (18,500) reported obtaining from retail sources.Footnote 59

Questions:

- Are measures in the TVPA sufficient to prevent youth from accessing tobacco products? If not, what more could be done to restrict youth access to these products?

Theme 5: Enhancing awareness and preventing Canadians from being deceived or misled

Informing Canadians

Canadians need accurate information to make informed decisions that could affect their health. One of the guiding principles of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control is that 'every person should be informed of the health consequences, addictive nature and mortal threat posed by tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke … to protect all persons from exposure to tobacco smoke'.Footnote 60

Early concerns around smoking were focused on the impact it had on the social and moral fabric of society,Footnote 61 as long-term health effects such as lung cancer were less understood at the time. Cigarette use grew in popularity between the 1920s and 1950s, and by 1965 smoking was considered a normal part of life with close to 50 percent of Canadians smoking cigarettes.Footnote 62 As research began linking tobacco use to lung cancer in the early 1950s and 1960s, public views towards smoking slowly began to shift and by the late 1990s, smoking became increasingly socially unacceptable. In the 1960s the tobacco industry in Canada voluntarily adopted marketing measures and warning labels on cigarette packages. These measures were not considered effective at communicating the risks of smoking, as the messages often blended into the packaging design. In 1989, Canada was among the first countries in the world to ban tobacco advertising, require health warnings on cigarette packages and require that ingredient information be submitted to government authorities. Just over a decade later, Canada was the first to require pictorial health warnings on packages of cigarettes and other tobacco products. Health Canada has also been involved in developing resources and marketing campaigns to educate youth and adults about the health hazards associated with tobacco use.

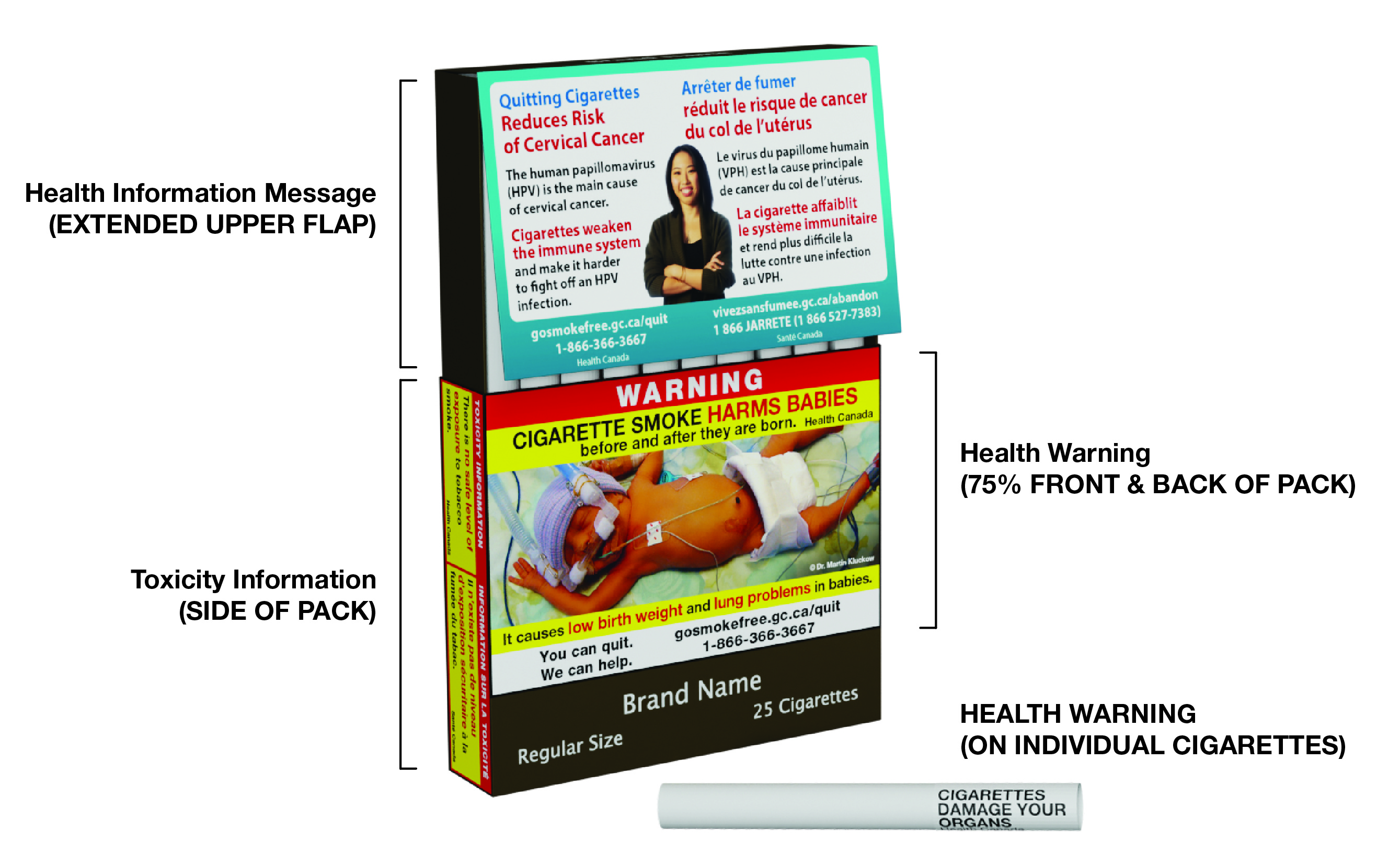

Evidence indicates that displaying health-related messages on tobacco packaging is one of the most effective approaches to inform people of the health hazards of tobacco use.Footnote 63 Messages on tobacco product packages and products have the potential of being seen daily by millions of people, increasing their reach to help Canadians live healthy, tobacco-free lives. To increase noticeability, health warnings should be large enough to be seen, memorable, and impactful. The TVPA prohibits the retail sale of tobacco products unless the product and the package containing it display, the information required by the regulations about the product and its emissions (such as toxicity information), and the health hazards and health effects arising from the use of the product and from its emissions (such as a health warning), as set out in the Tobacco Products Appearance, Packaging and Labelling Regulations. Figure 6 below shows an example of a cigarette package, and a cigarette, displaying the required information once these regulations are fully implemented (see note below). While health warnings are prominently displayed on the outside of packages and address the health hazards and negative effects of tobacco use, health information messages are included inside tobacco packages to address the benefits of quitting and provide smoking cessation tips.

Figure 6 - Text description

On extended upper flap of the cigarette package, a white box with a blue border contains a health information message. At the centre is a woman with arms crossed.

Justified to the left is the following text:

Quitting cigarettes reduces risk of cervical cancer. The human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main cause of cervical cancer. Cigarettes weaken the immune system and make it harder to fight off an HPV infection.

gosmokefree.gc.ca/quit

1-866-366-3667

Health Canada

In the middle of the pack of cigarettes, a health warning on 75 percent of the front of the pack contains an image of a baby.

Centered justified is text:

WARNING

Cigarette Smoke Harms Babies before and after they are born.

It causes low birth weight and lung problems in babies.

You can quit. We can help.

1-866-366-3667

gosmokefree.gc.ca/quit

Health Canada

On the bottom of the cigarette package, a small space is reserved for the brand name, pack size and number of cigarettes it contains.

On side of cigarette package, a yellow rectangular box contains toxicity information.

Justified to the left is the following text:

Tobacco smoke contains more than 70 chemicals than can cause cancer. Health Canada

One cigarette shown lying horizontally with a white filter. Printed on the filter is the health warning: CIGARETTES DAMAGE YOUR ORGANS

Source: Health Canada, 2023.

Note: A transition period is provided for tobacco manufacturers until July 31, 2026 for the implementation of the new placement for Health Information Message on an extended upper slide-flap of slide and shell cigarette packages, as shown in the image above. In the interim, Health Information Messages will continue to be displayed on the inside back slide of cigarette packages.

With respect to awareness, national surveys showed that most Canadians, including youth and adults, are aware that smoking cigarettes is harmful, particularly when used on a regular basis.Footnote 64Footnote 65 A 2022 study showed that smoking tobacco regularly was viewed as having moderate or great risk by the vast majority (95 percent) of Canadians aged 16 years and older; in contrast, fewer Canadians perceived moderate or great risk in regularly using the following substances: e-cigarette with nicotine (89%), drinking alcohol (75%), vaping cannabis (75%), smoking cannabis (73%), and eating cannabis (66%).Footnote 66 A 2020 study showed that most Canadian adults who smoke were aware of the specific diseases and conditions caused by smoking, although the level of awareness did vary by specific health effect. For example, there was high awareness that smoking causes lung cancer and heart disease, but low awareness that smoking causes blindness or bladder cancer.Footnote 67 Furthermore, when Canadians were asked about the social acceptability of using various substances, either on a regular or occasional basis, smoking was the least acceptable compared to alcohol and cannabis products.Footnote 68 Public opinion research conducted in 2022 among youth and young adults (approximately 200 participants) indicates that, overall, cigarettes were rarely used by participants, with many stating that they were not interested in cigarettes and find them disgusting.Footnote 69

To maintain the effectiveness of health-related messages in raising public awareness and ensure that they reflect the latest research and science available, the health warnings and health information messages require regular updating.Footnote 70 Canada updated the required health-related messages for cigarettes and little cigars in 2011 and again in June 2023 for all tobacco products. The 2023 amendments to the Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance) came into force on August 1, 2023. The amended regulations, now named; the Tobacco Products Appearance, Packaging and Labelling Regulations, standardize the minimum health warning size to at least 75 percent of the main display area of the packaging for most tobacco products. The regulations introduce a new location for health information messages for cigarette packages to make these messages more noticeable. It also extends the display of health-related messaging to all tobacco product packaging, which is important to prevent the misperception that products without messages are less harmful. This expansion also captures new tobacco products that enter the market. A mandatory display of health warnings directly on individual cigarettes, little cigars that have tipping paper, and tubes was also introduced in this amendment, making Canada the first country in the world to take this approach. Young persons experimenting with smoking often obtain individual cigarettes through social sources and are not exposed to the health-related messaging on cigarette packaging. Having messages directly on the product themselves allow health warnings to reach and inform youth of the health hazards and health effects of tobacco use and can make the products less appealing.

Preventing Canadians from being deceived or misled

Consumers should have accurate information about the products they purchase or use. The TVPA prohibits promotion of tobacco products "in a manner that is false, misleading or deceptive with respect to, or that is likely to create an erroneous impression about, the characteristics, health effects or health hazards of the tobacco product or its emissions". Removing misleading terminology from tobacco products, packaging, and promotion help protect people from false inferences about product harm and help them make informed choices. For example, cigarettes described as "light" and "mild" could be misperceived as being less harmful, a belief which is not supported by research. To protect the public from misleading and deceptive information on tobacco products the Promotion of Tobacco Products and Accessories Regulations (Prohibited Terms) prohibit the use of the misleading terms "light" and "mild," and variations thereof, on cigarettes, little cigars, bidis, kreteks, cigarette tobacco, tobacco sticks, cigarette papers, filters, and tubes. The prohibition applies to the products, their packaging, advertising, promotions, and to retail displays. The Regulations also apply to tobacco accessories that may be used in the consumption of a tobacco product, including pipes, cigarette holders, cigar clips, lighters, and matches.

Physical characteristics of tobacco products themselves could also be misleading and cause misperceptions of reduced harm. For example, super slim and ultra slim cigarettes could be perceived as less harmful than regular cigarettes because they were noticeably slimmer.Footnote 71 As well, experiments conducted with both people who smoked and those who did not smoke in Canada and the United States of America found that packs with lighter colours were perceived as less harmful than packs in darker colours.Footnote 72Footnote 73Footnote 74 A study in the United States of America found that both "color and product descriptors are associated with false beliefs about risks". Footnote 75 The Tobacco Products Appearance, Packaging and Labelling Regulations standardize the appearance of tobacco packages and products through general requirements applicable to all tobacco products, as well as through specific requirements applicable to individual tobacco product types. For instance, all tobacco product packages must be of the same drab brown colour, bearing only the permitted text displayed in a standard location, font style, colour and size. Tobacco products must be plain in appearance, bearing only the permitted text in the prescribed location, font style, colour, and size. This protects Canadians from misleading information or misperceptions of risk communicated through packaging design featuresFootnote 76 and removes distractions from the informative health warnings on packages.

People can have the misperception that products containing additives associated with health benefits are less harmful than products which do not. To protect people from being misled, the TVPA limits such additives in tobacco products. Additives that are prohibited in tobacco products include substances that create the impression of health benefits or are associated with energy and vitality, such as vitamins, probiotics, and minerals. To monitor tobacco product contents, the Tobacco Reporting Regulations require manufacturers to provide Health Canada information about their tobacco products, such as the ingredients and emissions of their products.Footnote 77

Questions:

- To what extent have tobacco product appearance, packaging and labelling requirements been sufficient to increase public awareness about the health hazards of these products? If not sufficient, what more could be done?

- Are the current product standards and prohibitions on promotion sufficient to prevent the public from being deceived or misled about the health hazards of tobacco products? If not sufficient, what more could be done?

Theme 6: Compliance, enforcement and regulated parties

To achieve the TVPA's purpose of providing a legislative response to address tobacco use, the provisions include compliance and enforcement mechanisms. The Government of Canada is also exploring requiring tobacco manufacturers to pay for the cost of federal public health investments in tobacco control. Further, the Government of Canada is under international obligations to protect public health policies from commercial and other interests of the tobacco industry.

Compliance and Enforcement:

The TVPA provides a range of powers to designated inspectors to verify compliance with its provisions, as well as take enforcement actions. Inspectors are authorized to enter any place where they believe on reasonable grounds a tobacco product is manufactured, tested, stored, promoted, transported, or furnished to, among other activities, examine, sample, or test a tobacco product to verify compliance with the TVPA. The TVPA further provides inspectors with powers to seize any thing, including a tobacco product, that was used in the contravention of the TVPA and associated regulations.Footnote 78

Health Canada proactively engages in compliance promotion activities with industry, the public, and other stakeholders, to inform and encourage regulated parties' compliance with requirements under the TVPA. Health Canada inspectors provide informational tools and documents such as copies of applicable regulations, information letters, facts sheets, and toolkits. Health Canada monitors and verifies industry compliance through regular inspections of tobacco product manufacturers and retailers, which entail sampling, technical examination, and laboratory analysis of tobacco products. If non-compliance is identified, Health Canada may pursue enforcement action in the form of issuing warning letters, negotiating compliance, seizing non-compliant products or promotions, and/or pursuing prosecution.Footnote 79

Since 2018, Health Canada's compliance and enforcement activities have been directed primarily at packaging and labelling, promotion, and prohibited additives in tobacco products. In 2019-2020, Health Canada conducted 691 tobacco retail inspections and two tobacco manufacturer inspections. These inspections resulted in enforcement action in the form of 22 warning letters, 13 negotiated compliances, and 60 seizures (including 2,078 packages and 36,414 individual tobacco product units). In the context of constraints due to the pandemic in 2020-2021, Health Canada also conducted 10 remote inspections to assess tobacco manufacturers' compliance with the new product and packaging requirements pursuant to the Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance).Footnote 80 During the 2021-2022 fiscal year, Health Canada conducted inspections at three manufacturers and over 1,300 retail establishments to assess compliance with provisions under the Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance) and Tobacco Products Labelling Regulations (Cigarettes and Little Cigars).Footnote 81 The observed rate of non-compliance was 100 percent at tobacco product manufacturers, while fewer than 6 percent of tobacco product retailers were found carrying non-compliant products. In the most recent fiscal year, 2022-23, Health Canada conducted 21 manufacturing inspections and over 2000 retail inspections to assess compliance with the packaging and labelling requirements. 2022-23 was the first fiscal year that the complete Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance) was in force, including the slide and shell requirements. The observed rate of non-compliance remained high at manufacturing, at 70 percent, and the rate of non-compliance at retail rose to over 18%. Most non-compliances observed at retail were related to the new slide and shell requirements.

Recovering the costs of federal tobacco control activities:

The Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health's 2021 mandate letter included a commitment to "require tobacco manufacturers to pay for the cost of federal public health investments in tobacco control." This priority was reiterated in Budget 2023. Health Canada is working with partners within the federal government to examine options and determine next steps.

Article 5.3 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control:

Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) must act to protect their public health policies, with regards to tobacco control, from commercial and other interests of the tobacco industry. Article 5.3 Guidelines highlight the fundamental conflict between the tobacco industry's interests and public health policy interests. This means, among other things, that Canada should only interact with the tobacco industry to the extent necessary to effectively regulate the industry and its products while ensuring transparency of the interactions that occur.

The Government of Canada's engagement with industry members is subject to its WHO FCTC commitments. Thus, engagement with the tobacco industry is limited to instances where it is necessary to regulate the industry and tobacco products effectively. In support of transparency, information on industry meetings that take place with the department are regularly posted on Health Canada's public record of meetings. Canada has also implemented other WHO FCTC recommendations such as avoiding conflicts of interest for government officials and employees.

Questions:

- Could compliance and enforcement be further strengthened to address current and future issues regarding tobacco control? If so, how?

- What are the opportunities and challenges you anticipate with requiring tobacco manufacturers to pay for the cost of federal public health investments in tobacco control?

- Could the Government of Canada improve the implementation of FCTC Article 5.3? If so, how?

Theme 7: Engaging with Indigenous Peoples

The Government of Canada recognizes the sacred and ceremonial role that traditional tobacco has for many First Nations and Métis Peoples. Many First Nations have been using traditional or sacred tobacco for thousands of years in ceremonial or sacred rituals for various purposes, including healing and purifying.Footnote 82 Under Canada's Tobacco Strategy, First Nations, Inuit and Métis are supported to develop and implement their own self-led, distinct approaches to reducing commercial tobacco use in their communities, based on their own needs and priorities. This supports Indigenous self-determination and control over culturally appropriate service design and delivery.

Canada has fully endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act came into force, which provides a roadmap for the Government of Canada and First Nations, Inuit and Métis to work together to implement the Declaration based on lasting reconciliation, healing, and cooperative relations. All federal departments will have important roles to play in implementing the Declaration, including Health Canada. As relationships and collaboration between the Government and First Nations, Inuit and Métis continue to develop and strengthen, the Government of Canada remains committed to understanding their unique needs and priorities on tobacco matters. Many areas of co-operation remain open, such as determining through the legislative review process the impact the TVPA and its regulations has had on First Nations, Inuit and Métis and their communities. Gathering the perspectives, knowing and supporting the priorities, and protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples is the starting point for putting the United Nations Declaration into action.

Questions:

- What are the key commercial tobacco-related priorities from a First Nations, Inuit or Métis perspective? Could the TVPA be strengthened to support these priorities? If so, how?

- From a First Nations, Inuit or Métis perspective, what are your main concerns related to the regulation of tobacco in Canada?

- What elements do you consider essential to reducing commercial tobacco use in First Nations, Inuit or Métis communities?

Conclusion

The TVPA is one of the key tools in addressing tobacco use in Canada. With respect to tobacco products, the TVPA aims specifically to protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them; to protect the health of young persons by restricting access to tobacco products; to prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using tobacco products; and to enhance public awareness of those hazards. All of these key objectives are addressed in the various themes of this discussion paper.

In the context of this review of the TVPA, Canadians are invited to provide their views on whether progress is being made towards achieving the stated tobacco-related objectives and whether the TVPA is sufficient in addressing tobacco use in Canada.

In addition to the questions posed throughout the paper, Canadians are also welcome to provide their views on these four questions about the legislation and the tobacco provisions therein:

- Is there anything else that you would like to add as it relates to any of the topics covered in this discussion paper?

- Do you think the TVPA works as intended and if not, what would you improve?

- What key issues remain, that if successfully addressed, would result in a further strengthening of the TVPA?

- Do you have suggestions for what could be included in future legislative reviews of the TVPA?

Appendix A: Discussion Questions

- What are the factors that lead to tobacco use? Please provide any data or evidence to support your response.

- Are there new measures or adjustments to current measures that the Government of Canada could consider to better support smoking cessation efforts?

- Are there any international approaches that have proven to be successful in cessation efforts that the Government of Canada should be studying and adopting?

- Are there legislative measures that could be considered to address the public health problem posed by tobacco use in groups disproportionately affected by tobacco? If so, how could the legislation better address these disparities?

- Are the prohibitions within the TVPA and requirements in its regulations sufficient to protect young persons and others from inducements to use tobacco products and the consequent dependence on them? If not, what more could be done?

- Are there additional sources of information that could be collected to improve monitoring the tobacco market in Canada? If so, what are they?

- Are measures in the TVPA sufficient to prevent youth from accessing tobacco products? If not, what more could be done to restrict youth access to these products?

- To what extent have tobacco product appearance, packaging and labelling requirements been sufficient to increase public awareness about the health hazards of these products? If not sufficient, what more could be done?

- Are the current product standards and prohibitions on promotion sufficient to prevent the public from being deceived or misled about the health hazards of tobacco products? If not sufficient, what more could be done?

- Could compliance and enforcement be further strengthened to address current and future issues regarding tobacco control? If so, how?

- What are the opportunities and challenges you anticipate with requiring tobacco manufacturers to pay for the cost of federal public health investments in tobacco control?

- Could the Government of Canada improve the implementation of FCTC Article 5.3? If so, how?

- What are the key commercial tobacco-related priorities from a First Nations, Inuit or Métis perspective? Could the TVPA be strengthened to support these priorities? If so, how?

- From a First Nations, Inuit or Métis perspective, what are your main concerns related to the regulation of tobacco in Canada?

- What elements do you consider essential to reducing commercial tobacco use in First Nations, Inuit or Métis communities?

- Is there anything else that you would like to add as it relates to any of the topics covered in this discussion paper?

- Do you believe the TVPA works as intended and if not, what would you improve?

- What key issues remain, that if successfully addressed, would result in a further strengthening of the TVPA?

- Do you have suggestions for what could be included in future legislative reviews of the TVPA?

Endnotes:

- Footnote 1

-

Statistics Canada. Current Smoking Trends. Health at a Glance. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2012001/article/11676-eng.pdf?st=wDqqRWTv

- Footnote 2

-

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms. 2023. Can be assessed here: https://csuch.ca/documents/reports/english/Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-and-Harms-Report-2023-en.pdf?_cldee=8uPMv0K93rNcHishHRhr7tA7XfJvF_ZHNkCjPFI70b8BPLtPpKaKGXNcadCt2D-p&recipientid=contact-66dfe5925e63e8118145480fcff4b5b1-2b1aa57329714146a59ce192d976ddac&esid=1d1b0e51-8ecd-ed11-a7c6-000d3a09c3d2

- Footnote 3

-

Canadian Community Health Survey, 2001 and 2021.

- Footnote 4

-

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms. 2023. Can be assessed here: https://csuch.ca/documents/reports/english/Canadian-Substance-Use-Costs-and-Harms-Report-2023-en.pdf?_cldee=8uPMv0K93rNcHishHRhr7tA7XfJvF_ZHNkCjPFI70b8BPLtPpKaKGXNcadCt2D-p&recipientid=contact-66dfe5925e63e8118145480fcff4b5b1-2b1aa57329714146a59ce192d976ddac&esid=1d1b0e51-8ecd-ed11-a7c6-000d3a09c3d2

- Footnote 5

-

Government of Canada. Risks of smoking. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/effects-smoking/smoking-your-body/risks-smoking.html

- Footnote 6

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- Footnote 7

-

Government of Canada. Stigma: Why Words Matter. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/stigma-why-words-matter-fact-sheet.html

- Footnote 8

-

Canadian Community Health Survey. 2020.

- Footnote 9

-

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Can be accessed here: https://fctc.who.int/publications/i/item/9241591013

- Footnote 10

-

Benowitz N. Pharmacology of nicotine: Addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:57–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094742.

- Footnote 11

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Tobacco Addiction. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIDA Research Report Series. NIH Publication Number 09-4342 Printed July 1998, Revised June 2009.

- Footnote 12

-

Government of Canada. Nicotine addiction. 2013. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/health-effects-smoking-second-hand-smoke/nicotine-addiction.html

- Footnote 13

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Tobacco Addiction. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIDA Research Report Series. NIH Publication Number 09-4342 Printed July 1998, Revised June 2009.

- Footnote 14

-

U.S. Department Of Health And Human Services Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. 2016. E-cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General.

- Footnote 15

-

Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF. 1996. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1996;35(12):1602–1610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00011.

- Footnote 16

-

Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):322–330. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018.

- Footnote 17

-

Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11): 1039–1044. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039.

- Footnote 18

-

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284(18):2348–2351. Doi:10.1001/jama.284.18.2348.

- Footnote 19

-

US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

- Footnote 20

-

Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, Sandhu R, Sharma S. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449-61

- Footnote 21

-

USSG 2016. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2016.

- Footnote 22

-

International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. Personal Habits and Indoor Combustions. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 100E. Retrieved from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Personal-Habits-And-Indoor-Combustions-2012.

- Footnote 23

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010.

- Footnote 24

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Printed with corrections, January 2014.

- Footnote 25

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, Eaton, D. L., Kwan, L. Y., & Stratton, K. (Eds.)., 2018. Public Health Consequences of ECigarettes. National Academies Press (US).

- Footnote 26

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010.

- Footnote 27

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Surgeon General. (2010). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK53017.pdf

- Footnote 28

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Benefits of smoking cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Diseases Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1990, preface, p.xi. Accessed from: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/C/V/_/nnbbcv.pdf.

- Footnote 29

-

Government of Canada. Benefits of quitting smoking. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/quit-smoking/benefits-quitting.html

- Footnote 30

-

Fact sheet about health benefits of smoking cessation, World Health Organization Tobacco Free Initiative, https://www.who.int/tobacco/quitting/benefits/en/

- Footnote 31

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.

- Footnote 32

-

Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking, IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 83, IARC, 2004 (https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Tobacco-Smoke-And-Involuntary-Smoking-2004)

- Footnote 33

-

Environics Research, 2022. Smokers Panel Baseline Survey 2022 Final Report. A report commissioned by Health Canada. Retrieved from: https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/pwgsc-tpsgc/por-ef/health/2022/096-21-e/index.html

- Footnote 34

-

Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, 2015.

- Footnote 35

-

Hammond, D. (2011). Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tobacco control, 20(5), 327-337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630.

- Footnote 36

-

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey. 2021. Can be accessed here: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1314175.

- Footnote 37

-

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey. 2021.

- Footnote 38

-

Government of Canada. Public Opinion Research reports. (POR 074-17). Can be accessed here: https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/government-canada/public-opinion-research/search-report/pages/search-report-result.aspx?titlekeyword=vaping.

- Footnote 39

-

The Tobacco Products Regulations (Plain and Standardized Appearance) have since been repealed and consolidated into the Tobacco Products Appearance, Packaging and Labelling Regulations.

- Footnote 40

-

Wakefield, M., Morley, C., Horan, J. K., & Cummings, K. M. (2002). The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tobacco Control, 11 (Suppl 1), I73-80. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73

- Footnote 41

-

Doxey, J., & Hammond, D. (2011). Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tobacco Control, 20(5), 353-60. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038315

- Footnote 42

-

Hammond, D., Doxey, J., Daniel, S., & Bansal-Travers, M. (2011). Impact of female-oriented cigarette packaging in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13(7), 579–588. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr045

- Footnote 43

-

DiFranza, J. R., Eddy, J. J., Brown, L. F., Ryan, J. L., & Bogojavlensky, A. (1994). Tobacco acquisition and cigarette brand selection among youth. Tobacco Control, 3(4), 334

- Footnote 44

-

Moodie, C., A. M. MacKintosh, K. Gallopel-Morvan, G. Hastings, A. Ford. (2016). Adolescents' perceptions of an on cigarette health warning. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 1-6. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntw165

- Footnote 45

-

Analytic Insight Inc. (1986). Capri: the consumer acclimation process and reactions to proposed packaging. Prepared for Brown & Williamson. bates: 465902929-465902991

- Footnote 46

-

Carpenter C., Wayne G. & Connolly G. (2005). Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 100(6), 837–851. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x

- Footnote 47

-

RJR (1988). Review of female targeted brands. RJ Reynolds. bates: 507124752-4797

- Footnote 48

-

RJR (1988). Review of female targeted brands. RJ Reynolds. bates: 507124752-4797.

- Footnote 49

-

Government of Canada. Tobacco Reporting Regulations (SOR/2000-273), Section 13 (last amended March 4, 2019).

- Footnote 50

-

U.S. National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 21. NIH Publication No. 16-CA-8029A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Footnote 51

-

U.S. National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 21. NIH Publication No. 16-CA-8029A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; and Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Footnote 52

-

Physicians for a smoke-free Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.smoke-free.ca/SUAP/2020/Generalbackgroundonretail.pdf

- Footnote 53

-

Physicians for a smoke-free Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.smoke-free.ca/SUAP/2020/Generalbackgroundonretail.pdf

- Footnote 54

-

Health Canada. Annual Report on Compliance and Enforcement Activities (Tobacco Control). Can be accessed here: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/sc-hc/h246-1-2017-eng.pdf

- Footnote 55

-

Lee JGL, Kong AY, Sewell KB, et al. Tob Control 2021;0:1-12.doi:10.1136/ tobaccocontrol-2021-056717

- Footnote 56

-

Chan, W.C and Leatherdale, S.T. 2011. Tobacco retailer density surrounding schools and youth smoking behaviour: a multi-level analysis. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 9:9.

- Footnote 57

-

Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada (2020), Tobacco Retail: A scan of available regulatory approaches. Retrieved from: https://www.smoke-free.ca/SUAP/2020/Generalbackgroundonretail.pdf

- Footnote 58

-

Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) 2021-22.

- Footnote 59

-

Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) 2021-22.

- Footnote 60

-

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Article 4.1, pg 5. Retrieved from: https://fctc.who.int/.

- Footnote 61

-

National Library of Medicine. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Can be accessed here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK294310/

- Footnote 62

-

University of Waterloo. Tobacco Use In Canada. Historical trends in smoking prevalence. Retrieved from: https://uwaterloo.ca/tobacco-use-canada/adult-tobacco-use/smoking-canada/historical-trends-smoking-prevalence

- Footnote 63

-

Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review Tobacco Control 2011;20:327-337.

- Footnote 64

-

CTADS 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-alcohol-drugs-survey/2017-summary.html

- Footnote 65

-

CTADS 2021-2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2021-2022-summary.html

- Footnote 66

-

Canadian Cannabis Survey (CCS) 2022. The survey can be assessed here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2022-summary.html

- Footnote 67

-

International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC). 2022 Can be accessed here: https://itcproject.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/documents/ITC_Health_Warnings_in_Canada_en_v6_FINAL_1.pdf

- Footnote 68

-