Report of the First Legislative Review of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 773 KB, 50 pages)

- Organization: Health Canada

- Date published: 2022-12-09

- Cat.: H149-20/2022E-PDF

- ISBN: 978-0-660-46409-1

- Pub.: 220505

Executive Summary

The Tobacco Act was amended on May 23, 2018 to become the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA). The TVPA, along with other pieces of legislation, created a new legal framework for vaping products. Given that vaping products were relatively new to the market at that time and some scientific uncertainties existed, the TVPA includes a requirement for regular reviews to examine and respond to tobacco and/or vaping-related issues that may emerge over time.

This report represents the results of the first legislative review of the TVPA, following the first three years of its operation. The review focusses on the vaping-related provisions and operation of the TVPA, particularly the provisions to protect young persons, in response to an increase in youth vaping that was observed following the introduction of the TVPA.

The review was informed by available evidence, which included population-level surveys conducted by Health Canada and Statistics Canada, public opinion research carried out by Health Canada and peer-reviewed scientific journal publications. Data and evidence presented in this report is current as of the conclusion of the consultation, April 2022, to correspond with the review period. It was also informed by a broad-based online consultation process, supported by a discussion paper, that elicited 3,092 responses from a range of interested parties. This included people who use vaping products, health professionals and regional health authorities, non-governmental organizations, provinces and territories, academics, industry and members of the general public. The consultations revealed a range of divergent perspectives. Some stakeholders called for increased restrictions on vaping products to further protect youth from potential health hazards, while others felt that the legislation needs to be less restrictive to encourage those who smoke to consider switching to vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine. Others felt that vaping products were sufficiently regulated and that more time and improved enforcement would allow the legislation to realize its full potential. In general, stakeholder positions have remained relatively consistent since the TVPA was introduced.

The review period coincides with a global pandemic that significantly changed activities and behaviours in a myriad of ways. COVID-19 pandemic public health measures placed restrictions on individuals' activities and likely influenced trends throughout this period. These factors were also weighed in the assessment of the operation of the TVPA as they relate to this review.

The analysis undertaken as part of the review, along with the input received from consultations confirms that, in general, the TVPA appears to be making progress towards achieving its vaping-related objectives and that amendments at the level of the Act are not necessary at this time. Analysis has shown that youth vaping rates, which were rising at a rapid pace, have leveled off over the past two years yet remain relatively high. In addition, regulatory actions taken since the TVPA came into force have demonstrated that the TVPA contains sufficient regulatory authority to quickly respond to issues as they emerge. These actions include the implementation of labelling requirements and promotion restrictions in 2020, and restrictions on nicotine content in 2021. Ongoing work on regulatory proposals to further restrict flavours in vaping products and require vaping product manufacturers to submit information to Health Canada about their sales and ingredients is also underway. More time is required to determine the efficacy of these actions.

The review concludes with several observations. The observations highlight concerns around youth access to vaping products, a lack of awareness related to the relative risks of using vaping products, compliance and enforcement issues, and a continuing lack of authoritative scientific knowledge on vaping products. It goes on to identify four areas for potential action:

Examining access to vaping products by youth

The vaping product market has changed significantly since the new legislation was enacted. Because of this, a closer examination of the retail environment, particularly as it relates to youth access, may be required. With respect to online sales, age verification requirements under the current regulatory regime may not be sufficiently responsive. A Federal/Provincial/Territorial working group could be established with a view to assessing current practices to ensure that youth are adequately protected. Access to vaping products in physical stores was also identified as a concern. In light of this, the government could undertake work to examine this issue and identify actions to address these concerns. For example, a range of measures that would restrict retail access to vaping products for youth or restrict access to products that are targeted to youth, could be explored.

Communicating the potential benefits of vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine for people who smoke as well as the health hazards

More sustained public education and awareness efforts could be considered to better inform youth and non-users of tobacco products about the health hazards of vaping. Likewise, the majority of adults who currently smoke are not aware that vaping products are less harmful than using tobacco products. Work could be undertaken to communicate the relative risk of smoking, in comparison to vaping, to people who smoke. These measures could include assessing the merits of developing relative risk statements and requiring the tobacco industry to use prescribed messages in cigarette packages and updating website materials. Such information could assist Canadians in making informed choices about their health.

Strengthening compliance and enforcement

Developing guidance for industry could be explored as a means to promote compliance with current obligations and could improve industry's understanding of the requirements overall. Given evidence of repeated infractions and the limitations of warning letters, the development of additional tools to respond to non-compliance with a progressive enforcement approach could be explored.

Addressing scientific and product uncertainty

Obtaining accurate information on the vaping product market and the content of vaping products remains a challenge. Improving the quality and quantity of information in this area would enhance the Government's ability to effectively regulate these products. Requiring manufacturers to submit information on their ingredients and product sales would address some of the challenges related to better understanding and regulating the vaping product market. In addition, to address scientific uncertainties, a comprehensive assessment of the evidence related to the health hazards of vaping and potential benefits of vaping for people who smoke could be considered.

The next review, which will begin in 2023, will provide an opportunity to examine other dimensions of the TVPA, with a view of ensuring that the legislation is continuing to adequately support the effective regulation of tobacco and vaping products in Canada.

Introduction

Legislative Review

The Tobacco Act was amended on May 23, 2018, to become the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA). The TVPA's overall purpose is to provide a legislative response to a national public health problem of substantial and pressing concern and to protect the health of Canadians in light of conclusive evidence implicating tobacco use in the incidence of numerous debilitating and fatal diseases. A new legal framework was included in the TVPA. This, in conjunction with amendments made to other pieces of federal legislation, were designed to respond to the increasing availability of vaping productsFootnote 1 in Canada and to help ensure that Canadians would be appropriately informed about, and protected from, the risks associated with these products. With respect to vaping, the TVPA aims to prevent vaping product use from leading to the use of tobacco products by young persons and non-users of tobacco products.

During the course of developing and debating the legislation, Parliament took into account that vaping presented the potential to be a less harmful source of nicotine for people who smoke and completely switch to vaping. However, parliamentarians also recognized that these products presented health hazards to youth and non-users of tobacco products and worked to ensure that they were adequately protected. Accordingly, the TVPA included broad regulation-making authorities pertaining to advertising, promotion, labelling, access, flavours, and product attributes to enable the Government of Canada to respond to emerging evidence and fine-tune restrictions as needed.

The TVPA also included a requirement for a legislative review of its provisions and operation three years after coming into force, and every two years thereafter. This was designed to address uncertainty around vaping products and the rapidly changing landscape of tobacco and vaping product usage. The cyclical nature of the reviews provides a means to examine and respond to tobacco and vaping-related issues that may emerge over time. Following the legislative review, the TVPA requires a report to be tabled in both Houses of Parliament. In accordance with these requirements, the Minister of Health and Associate Minister of Health initiated the first review in 2021.

Scope

The first legislative review focusses on the vaping-related provisions and operation of the TVPA, particularly the provisions to protect young persons. A sharp increase in youth vaping rates, which followed the establishment of the new legal framework for vaping products, led to focussing the first review on the vaping-related provisions. The first review assesses the operation of the TVPA, and examines early evidence from the TVPA's first three years to assess whether it is making progress towards achieving its stated vaping-related objectives. Subsequent reviews, which will take place every two years, will present the opportunity to focus on other elements of the TVPA.

Conduct of the Review

In 2021, a dedicated Secretariat within Health Canada was established to conduct the review. The Secretariat's analysis is contained in the following pages and includes an assessment of relevant data and evidence. The review was also informed by extensive consultations to gather the perspectives of Canadians, which are highlighted in this report. This report concludes with observations and proposes areas for potential action.

Available data and evidence were used to support the analysis. This included population-level surveys conducted by Health Canada and Statistics Canada, public opinion research carried out by Health Canada and peer-reviewed scientific journal publications. Data and evidence presented in this report is current as of the conclusion of the consultation period, April 2022, to correspond with the review period.

Public consultations also played an important role in the data and evidence-gathering effort. The public consultation period ran from March 16, 2022 to April 27, 2022. Canadians were encouraged to provide feedback on a discussion paper (Archived, March 2023), which was prepared by the Secretariat to support the consultation process. The paper examined each of the vaping-related objectives in the TVPA, provided a summary of the current context, and described federal government actions to respond to issues that have emerged since the new legal framework for vaping products was established. Each section of the discussion paper included a list of key questions to assist in providing input.

A total of 3,092 submissions were received from a variety of stakeholders during the consultation period. The vast majority of submissions received were from those who use vaping products. To a lesser extent, those who produce and sell vaping products were also represented amongst the submissions, along with those from other interested parties including health professionals and regional health authorities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Finally, a number of provincial and territorial governments and academics also contributed submissions (see Appendix A for more information). The input received from all of these stakeholders served to inform the final observations and areas for potential action.

In addition to the public consultations, targeted engagements took place with a number of key stakeholders, including the Health Portfolio's Scientific Advisory Board on Vaping Products, who were consulted periodically throughout the review. Given their shared responsibility for regulating vaping products, meetings with provincial and territorial governments were held to discuss the review, and to request their feedback. Discussions were also held with NGOs through Health Canada's NGO Forum, to seek their views and to invite them to respond to the public consultation. Because of the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, digital tools were employed to ensure participation in the review process in a manner that was safe, easy and accessible for all participants.

An evolving context

A comprehensive tobacco control regime has been implemented in Canada to protect the health of Canadians from tobacco-related death and disease. Canada's tobacco control policies have contributed to a significant reduction in tobacco use over time. From 2001 to 2018, the number of people who smoke in Canada decreased by 1.7 million.Footnote 2 Significant declines in the number of young persons who smoke played an important role in declining prevalence rates overall; smoking rates among Canadians aged 15-19 are currently at an all-time low.

The TVPA currently functions in conjunction with multiple federal Acts, such as the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) and the Non-smokers' Health Act (NSHA), effectively constituting the federal legal framework for vaping products in Canada. A number of vaping-related regulations have also been brought forward to complement the TVPA. The Government of Canada has also looked to international approaches to inform the development of policies to protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from the risks associated with vaping products.

Multiple legislative and regulatory measures aimed at reducing tobacco use have been introduced over time in combination with national strategies. In 2018, Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS) was introduced with the objective of reducing tobacco use to less than 5 percent by 2035 (from the 2017 baseline of 18%). Twelve percent (3.8M) of Canadians aged 15 years and older currently smokeFootnote 3 and tobacco use remains a major cause of death and disease, with approximately 48,000 Canadians dying from smoking-related illnesses every year.Footnote 4 The CTS recognizes the potential of harm reduction – helping those who cannot or do not wish to quit using nicotine to identify less harmful options – while continuing to protect young people and those who do not use tobacco from inducements to use nicotine and tobacco. At the same time, with little yet known about the long-term health impacts of vaping, choosing to use these products in the context of harm reduction should be considered a temporary measure to support smoking cessation.

All orders of government have responsibility within their own authorities/jurisdictions for adequately promoting and protecting the health of Canadians from known health hazards, such as tobacco use. For example, municipal, provincial and territorial governments are primarily responsible for restricting smoking and vaping in workplaces and public places, such as restaurants, bars, shopping centres and near schools. In general, provincial and territorial governments are also responsible for monitoring retail compliance with provincial and territorial laws, such as the minimum legal age to access tobacco and vaping products, and restrictions on retail promotion, flavours, labelling requirements and licensing. To further protect the health of Canadians, some municipal governments have also enacted bylaws that further restrict where tobacco and vaping products can be used. This comprehensive effort reflects the shared responsibilities of federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments.

International Perspective

Following the introduction of vaping products to the market, many countries faced the public health challenge of how to effectively handle these novel and rapidly changing products. In general, common concerns included uncertainties about long-term health impacts, their effectiveness in helping people quit smoking and the potential for their use to lead to tobacco use.

To address these challenges, countries have adopted a range of regulatory approaches, which reflect their unique national context. Most countries recognize the importance of protecting young people and non-users of tobacco products from becoming dependent on nicotine or turning to other tobacco products. Some countries are also advancing approaches that consider the potential benefits that vaping products may offer in helping people quit smoking, based on the latest scientific evidence. Those countries are looking at tobacco harm reduction to meet their aggressive tobacco reduction or "smoke-free" goals and are working to adopt regulatory approaches that consider both policy objectives.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that vaping products be regulated to include the objectives of preventing initiation by children and non-users of tobacco products; minimizing potential health risks to consumers; protecting non-users of tobacco products from exposure to emissions; preventing unproven health claims; and protecting public health policies from commercial and other vested interests.Footnote 5 According to the WHO's latest report on the tobacco epidemic, 111 countries regulate vaping products with 32 of those countries banning their sale. The remaining 79 countries having adopted other approachesFootnote 6 including regulating them as consumer products, pharmaceutical products, tobacco products, or as other distinct categories.

Despite different approaches to regulation, many jurisdictions have reported largely similar trends when it comes to the use of vaping products by youth. Although data collection varies and is not always comparable across jurisdictions, a scan of several comparable countries highlights their experience with vaping product use and regulation.

United States

According to the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, vaping product use increased 78 percent among high school students, from 11.7 percent in 2017 to 20.8 percent in 2018,Footnote 7 before falling to 11.3 percent in 2021.Footnote 8 The US responded to what they considered a "youth vaping epidemic" by prioritizing enforcement actions to address products that appeal to youth and by increasing their public education efforts.Footnote 9

Vaping products in the US are defined and regulated as tobacco products and are required to undergo a robust, scientific premarket evaluation for authorization prior to being marketed and sold. Companies with vaping products on the market as of August 2016, were required to file premarket tobacco product applications by September 2020. Until 2021, no vaping products had received marketing authorization despite being increasingly available on the market. However, later that same year, a number of tobacco-flavoured vaping products received marketing authorization as they had demonstrated that the marketing of these products "would be appropriate for the protection of the public health,"Footnote 10 whereas the vast majority have received Marketing Denial Orders.Footnote 11 The US continues to review applications for marketing approval for other vaping products, including some that have flavours other than tobacco. For authorized products, measures are in place to prevent youth uptake. These include access laws that set the minimum age of sale at 21, promotion restrictions, and requirements for health warnings on product packages and advertisements.

Australia

Australia has maintained a highly restrictive regulatory framework that differs from other countries.Footnote 12 The Australian government reported that between 2016 and 2019, young people aged 18-24 years who reported currently using e-cigarettes nearly doubled from 2.8 percent to 5.3 percent.Footnote 13 In Australia, nicotine is classified as a dangerous poison and can only be accessed as a therapeutic product with a prescription (with some exceptions). To stem the increase in the use of nicotine vaping products by young people, Australia was the first country in the world to ban the purchase or import of vaping products unless the consumer has a valid doctor's prescription to do so.

United Kingdom

The regulatory approach to vaping products in the UK is similar to the approach in Canada. However, the UK has made efforts to communicate the potential benefits of vaping products to people who smoke. Vaping products are subject to legislation in the UK that includes minimum standards of quality and safety under the Tobacco and Related Products Regulations (TRPR). It is illegal to sell or buy vaping products for anyone under 18. Additionally, the law contains product packaging and labelling requirements designed to give consumers the information they need to make educated decisions. Advertising is strictly controlled, and producers must report all the contents of vaping products to the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, which forbids the use of specific ingredients. Medicinally licensed nicotine vaping products are exempt from the TRPR, although currently there is no licensed product in England.Footnote 14

The government set out its ambition to make England smoke-free by 2030, defined as less than 5 percent smoking prevalence. According to a report from Public Health England, smoking remains the largest risk factor for death and health inequalities and suggests that nicotine vaping products could play an important role in reducing harm.Footnote 15 The same 2021 report found that vaping and smoking prevalence among young people in England both appear to have stayed the same in recent years - 6.2 percent of youth 16-19 years currently smoke and 7.7 percent of youth 16-19 years currently vape.Footnote 16

From an international perspective, as in Canada, regulating vaping products is dynamic. It appears that most countries, including Canada, are evaluating new evidence and responding to emerging issues to refine their regulatory approaches.

Assessment of the Act

The first review focusses on assessing whether progress is being made towards achieving the vaping-related objectives in the TVPA. These objectives are to:

- Protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products;

- Protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products;

- Protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products;

- Prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products; and,

- Enhance public awareness of those hazards.

In the following pages, this report will examine these objectives. For each of these, it will set out the current context, describe initiatives that have been undertaken to respond to emerging issues since the new legal framework for vaping products was established, and summarize what was heard from stakeholders during the consultation period. Taking all of this information into account, the report will conclude with observations and areas for potential action.

a) Protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products

The TVPA aims to protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products. As such, the legislation includes prohibitions on the promotion of vaping products, including prohibiting giveaways of vaping products (subject to the regulations) or branded merchandise that are associated with youth or are lifestyle-oriented. It also prohibits the promotion of flavours that are appealing to youth or specific flavour categories listed in Schedule 3 to the TVPA (confectionary, dessert, cannabis, soft drink and energy drink). Likewise, advertising that appeals to youth, lifestyle advertising, testimonials or endorsements and sponsorship promotion are also prohibited. Moreover, the legislation includes authorities to make regulations with respect to the promotion of vaping products to ensure that the government has the flexibility to keep pace with emerging technology and changing practices in the area of vaping product promotion.

Context

In order to assess the progress made towards protecting young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products, it is important to understand who is using these products and why.

Vaping product use in Canada increased overall after the new legal framework came into force in 2018. Some of this can be attributed to the expansion of the market as a result of the introduction of the new legal framework for these products. At the same time, vaping product technology and design was changing rapidly with many new products arriving on the market that were smaller, sleeker and easier to use (e.g., pod-type products and disposable products), contained high concentrations of nicotine and were offered in a variety of flavours. Major international players in the vaping product market also began to introduce new products in Canada. During this same period, television, social media and retail advertising, which could be seen or heard by youth, increased dramatically.

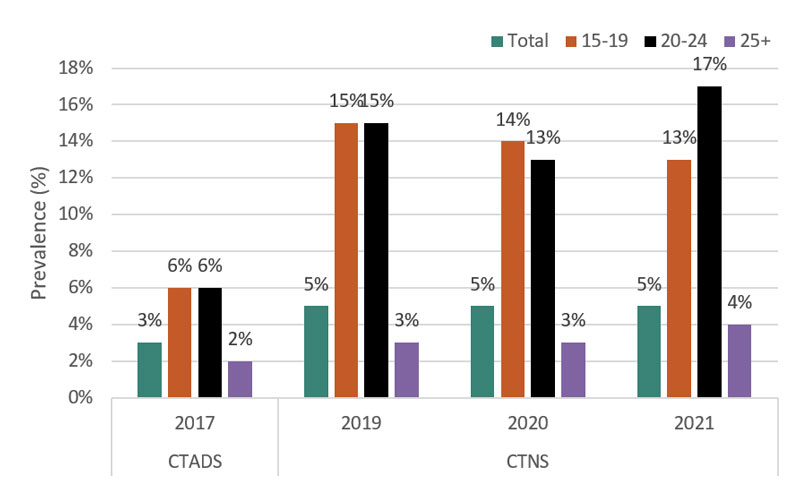

All of these factors played a role in the rise in youth vaping. Surveys have shown that youth vaping rates doubled over a two-year period, increasing from 6 percent (127,000) of 15-19 year olds reporting vaping at least once in the past 30 days in 2017Footnote 17 to 13 percent (262,000) in 2021,Footnote 18 which is unchanged since 2019.

With respect to adult use, there is some evidence that people who smoke are using vaping products as a less harmful source of nicotine than tobacco products. Surveys show that adults are using vaping products to quit smoking. Rates for adults 20 years and older have changed little since 2017.Footnote 19 Data from the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey indicate that vaping products were used by 5 percent (1.4M) of Canadians aged 20 years and older.Footnote 20 Among this group, 76 percent (1.0M) identified themselves as people who currently or formerly smoked and 24 percent (324,000) as people who have never smoked.Footnote 21 Among adults aged 20 years and older who currently smoke and vape, 49 percent (270,000) stated that they are vaping to quit and/or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked.Footnote 22

Figure 1 - Text Description

| Past 30-day vaping prevalence in Canada by age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2017 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| 15-19 | 6% | 15% | 14% | 13% |

| 20-24 | 6% | 15% | 13% | 17% |

| 25 + | 2% | 3% | 3% | 4% |

| Total | 3% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys. |

||||

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys.

Some significant events occurred in the years following the enactment of the new legal framework for vaping products that have likely had an impact on vaping product use in Canada. In 2019, a severe pulmonary illness – Vaping Associated Lung Injury (VALI, as it was referred to in Canada) or E-cigarette or Vaping Product Use Associated Lung Injury (EVALI, as it was referred to in the US) – emerged in North America, with 2,807 cases and 68 deaths in the US and 20 cases and no reported deaths in Canada. Evidence from the US outbreak suggested a strong association with vitamin E acetate, a cutting agent, found in illegal and unregulated cannabis vaping products; however, no definitive cause for the 20 cases seen in Canada could be determined.Footnote 23 The outbreak investigation was closed in August 2021.Footnote 24 Extensive media coverage, including the Government of Canada's advisory, which warned Canadians concerned about health risks related to vaping to consider not vaping, and those who continue to use vaping products to monitor themselves for symptoms and seek medical attention if needed, might have deterred some from using vaping products. Another significant event was the COVID-19 pandemic, where Canada implemented a number of social and economic restrictions that may have altered substance use behaviours. These restrictions resulted in youth spending more time at home and less time socializing in-person, and may have also produced a heightened awareness of health issues.

According to the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, the leading reason reported for why those aged 15-19 vape was to reduce stress, increasing from 21 percent in 2019 to 33 percent (86,000) in 2021. Youth also reported vaping because they enjoy it (28%, 74,000), curiosity (24%, 63,000) and other reasons (12%, 32,000 - moderate sampling variability; interpret with caution).Footnote 25 Evidence emanating from academic literature and public opinion research supports those findings and identifies additional factors, such as taste and flavours, price, the "head rush" some experience from using high nicotine concentration vaping products, the convenience of vaping, peer pressure and the ability to do vape tricks as additional reasons.Footnote 26,Footnote 27,Footnote 28

With respect to why people who do not use tobacco products vape, based on the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, people aged 20 years and older who had never smoked and who had vaped in the past 30 days reported the following reasons for vaping: enjoyment (37%, 119,000), to reduce stress or calm down (28%, 92,000) and curiosity (18%, 58,000 – moderate sampling variability; interpret with caution).Footnote 29

What Has Been Done

A rise in vaping products promotion on television, in social media, at events, on outdoor signs, and in retail locations to which youth and non-users of tobacco products were exposed, followed the coming into force of the new federal legal framework for vaping products in Canada. As a result, in June 2020, the Government of Canada took action to strengthen the existing prohibitions in the TVPA by putting in place the Vaping Products Promotion Regulations (VPPR). The VPPR prohibit the advertising of vaping products or vaping product-related brand elements that can be seen or heard by young persons. For example, advertising in places such as recreational facilities, public transit facilities, on broadcast media, in publications, including online, is prohibited, if the ads can be seen or heard by anyone under eighteen years of age. To limit youth exposure to the promotion of vaping products at points of sale, the VPPR also prohibit the display of vaping products and vaping product-related brand elements that can be seen by young persons.

To ensure compliance with the promotion prohibitions under the TVPA and its regulations, Health Canada inspectors undertake proactive compliance promotion activities (e.g., distributing educational materials to regulated parties). They also regularly conduct inspections of vaping product retailers, manufacturers, online stores, and any other place where vaping products are manufactured, tested, stored, transported, furnished or promoted. Regular enforcement actions to address non-compliance include issuing warning letters and seizing non-compliant products or promotional materials. In 2019, Health Canada inspected more than 3,000 specialty vape stores and gas and convenience stores across the country. These inspections resulted in the seizure of more than 80,000 units of non-compliant vaping products. In the same year, Health Canada issued compliance promotion letters to vaping manufacturers and importers to help increase awareness of the promotion prohibitions under the TVPA. In addition, Health Canada conducted inspections at 40 festivals and events, and responded to instances of non-compliance by shutting down prohibited promotional activities. Health Canada also issued letters to vaping manufacturers and importers, outlining the Department's expectations for compliance, including those pertaining to the promotion prohibitions under the TVPA.

In 2020 and 2021, within the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada transitioned from in-person inspections to online and remote inspections. Health Canada conducted virtual inspections of 304 Instagram social media accounts of online retailers, with a focus on promotion restrictions. Non-compliance was observed in 53 percent of inspections and resulted in warning letters being issued to the regulated parties. With respect to the VPPR, virtual inspections of retailers' websites are carried out to verify the presence of an age-gating mechanism to ensure that online advertising of vaping products cannot be seen or heard by young persons. The Department publicly discloses the results of its compliance activities on its website to further promote compliance within the industry and to provide transparency to Canadians.

In addition, recognizing that many flavoured vaping products appeal to youth, in 2021 the Minister of Health proposed to further restrict vaping product flavours to tobacco, mint and menthol, through amendments to Schedules 2 and 3 to the TVPA, and with new regulations. Submissions received through public consultations on this regulatory proposal are currently being reviewed. Studies have found that young people were more likely to initiate vaping with fruit and sweet flavours.Footnote 30 Data from the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey also shows that fruit flavours are the most used flavours (65%) among young people, aged 15-19, and adults 20 years and older (51%) who vaped in the past 30 days.Footnote 31 Moreover, studies have shown that vaping products with flavours other than tobacco are also perceived by youth to be less harmful.Footnote 32 The proposed changes, if adopted, are expected to make these products less appealing to youth and non-users of tobacco products, while maintaining a small number of flavour options for adults who wish to completely switch from smoking cigarettes to vaping as a less harmful source of nicotine. Some provinces and territories have put in place flavour restrictions in their jurisdictions to respond to the increases seen in youth vaping use. For example, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario have restricted where flavoured vaping products can be sold, whereas Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and the Northwest Territories have banned all flavours, other than tobacco.

What We Heard

While the vast majority of respondents acknowledge that youth vaping is a concern, there is no consensus on whether additional regulatory measures are warranted. Some provincial governments, regional health authorities, health professionals and NGOs are in favour of strictly regulating vaping with a strong emphasis on protecting youth and non-users of tobacco products. Those who responded to the consultation were generally of the opinion that the current restrictions are not sufficient to protect youth and non-users of tobacco products. Several submissions raised the need for additional measures such as plain packaging, pictorial health warnings and stricter regulation of vaping products design. The majority of their submissions also reiterated the need to act quickly and ban all flavours for vaping products, including mint and menthol. As an alternative, a few submissions suggested restricting flavours to adult-only or specialty vape stores.

In addition, some members of the general public, many provinces, health professionals and regional health authorities suggested strengthening restrictions on vaping product advertising and promotion, or completely banning vaping product marketing in both social media and print advertisements. They argued that a partial ban that restricts advertisements to adult venues is not sufficient to protect youth from exposure to marketing and advertisements that may be appealing.

On the other hand, many of the participants who use vaping products said that the government has sufficient measures in place to prevent youth vaping, and more time should be allowed for the current regulations to show their impact before moving forward with additional measures. They also voiced their opposition to the proposal to ban flavours in vaping products other than tobacco, mint and menthol. These respondents, in particular, reiterated that further restricting flavours will cause them to return to smoking, or will result in a rapid rise in the illicit market. They also indicated that the government is solely focusing on protecting youth and ignoring the benefits of vaping for people who smoke.

The vaping industry, including manufacturers, speciality vape stores and gas and convenience stores agreed that the TVPA and regulations are adequate to protect both youth and non-users of tobacco products. In their view, the issue is not a failure to adequately regulate but rather a failure to enforce existing measures.

In that regard, almost all those who responded to the consultation identified the need for increased compliance monitoring and enforcement, including stronger penalties for industry, notably for non-compliant promotion on social media platforms that are popular among youth. Some industry stakeholders, NGOs and provinces suggested that vaping products be submitted to Health Canada for a pre-market review in order to reduce the number of non-compliant products on the market, or that a protocol be put in place to verify compliance of product labels and promotional material with Health Canada. NGOs also supported a licensing regime for tobacco and vaping manufacturers and monetary penalties for anyone found to be in contravention of the TVPA.

Industry stakeholders provided feedback on the high number of non-compliant products seized by Health Canada and non-compliant promotion observed online since the new federal legal framework came into force. Vaping product manufacturers and their associations highlighted a need for Health Canada to provide guidance documents to assist in better understanding the promotion prohibitions under the TVPA and its associated regulations.

Furthermore, most industry submissions asserted that additional regulations would serve to prevent people who smoke from achieving harm reduction goals while failing to curb youth vaping. According to many industry stakeholders, the objective of balancing these two goals, which they believe was intended by lawmakers at the inception of the TVPA, has already been jeopardized by recent government policies and the introduction of numerous new regulations. They are critical of the government for solely focussing on protecting youth and ignoring the harm reduction objectives of Canada's Tobacco Strategy.

Likewise, most academics who contributed to the consultation process recommended that Health Canada adopt a harm reduction approach to vaping. They favoured an approach more in-line with the United Kingdom and New Zealand who have implemented proactive public education campaigns to promote switching from cigarettes to vaping products.

As an alternative, an association representing the interests of manufacturers of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products recommended a shift away from the current market where vaping products can be sold as either consumer products or therapeutic products. They suggested solely therapeutic regime, which would require all vaping products to be evaluated for safety, quality, and efficacy under the FDA and receive approval by Health Canada. There was also support from some regional health authorities for regulating vaping products as therapeutic products and restricting sales to pharmacies to protect youth and non-users of tobacco products, while maintaining access for those who wish to use vaping products to help them quit smoking.

b) Protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products

The TVPA is predicated on the notion that the most effective way to protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine is to prevent youth and non-users of tobacco products from ever using vaping products in the first place. It does this primarily by addressing the appeal of, and access to, vaping products. In addition to the measures mentioned in the first objective above, the TVPA restricts access to vaping products to persons over 18 years of age. This recognizes the negative health effects associated with nicotine use, particularly for youth. It also seeks to guard against the risk that nicotine dependence could lead to tobacco use and the resultant serious health hazards. The TVPA also has the authority to make regulations to establish product standards relating to the characteristics of vaping products and their emissions, including the functions and performance of the products, their appearance and the amounts of substances that may be contained in vaping products. Regulatory authorities in the legislation are designed to provide the necessary flexibility to develop requirements that can adapt to the market and respond to industry innovation and emerging evidence related to vaping products.

Context

Nicotine is the key chemical that makes tobacco products addictive and the reason why many Canadians find quitting tobacco use, such as smoking, challenging despite their desire and efforts to do so. Nicotine is found in many products including cigarettes, vaping products and smoking cessation products (e.g., nicotine replacement therapies such as patches and gums). To date, no vaping products have been approved under the Food and Drugs Act for therapeutic use as a smoking cessation aid; however, other nicotine replacement products have been available for a number of years.

The TVPA includes an objective to protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products. The legal framework allows vaping products to be used by people who smoke to transition away from cigarettes. It also puts in place restrictions to prevent youth and non-users of tobacco products from beginning to use nicotine-containing products and developing a dependence on it. The TVPA is based on the premise that young people and people who do not use tobacco products should not use any nicotine products, including vaping products. Following the enactment of the legislation, the availability of high-nicotine concentration vaping products in the Canadian market was identified as an important factor that contributed to the rapid rise in youth vaping. Data from the 2019 Wave 3 International Tobacco Control Youth Tobacco and Vaping SurveyFootnote 33 indicated that for youth in Canada aged 16-19 who had vaped in the past 30 days, using vaping products "for the nicotine" was identified as an important reason. Research with Canadian youth aged 13-19 from the Exploratory Research on Youth Vaping projectFootnote 34 also found that youth using vaping products with higher nicotine levels experienced a "head rush" or "buzz" and described it as by far "the best part about vaping."

Health risks associated with nicotine use that could result from vaping

Vaping products are not harmless and the long-term health effects of vaping products remain unknown. Further research is needed to better understand the impact of vaping on overall health. For those who do not use tobacco products, vaping can increase a person's exposure to potentially harmful chemicals, including nicotine. Nicotine is a highly addictive substance and youth are especially vulnerable. Youth, whose brains continue to develop until the age of 25, can become dependent on nicotine at lower levels of exposure than adults. Moreover, exposure to nicotine during adolescence can harm the developing brain and may have negative long-term effects on cognition.Footnote 35,Footnote 36

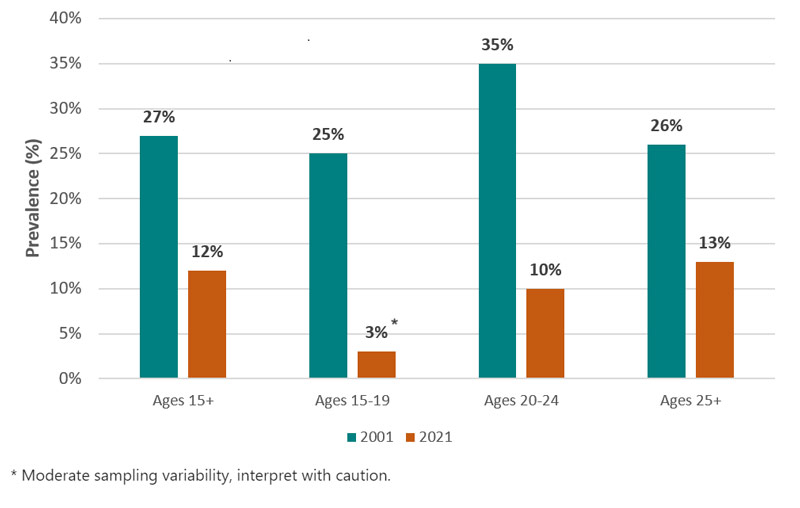

The most significant risk of developing a dependence on nicotine from vaping is the concern that it could lead to the use of combustible tobacco cigarettes. There is some evidence that vaping product use increases the risk of ever using combustible tobacco cigarettes among youth and young adults.Footnote 37,Footnote 38 However, recent data suggests that, thus far, smoking rates, for both youth and adults, continue to decline and are at an all-time low. The smoking prevalence from the 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey indicated that smoking among Canadians was 12 percent.Footnote 39

Figure 2 - Text Description

| Past 30-day smoking prevalence in Canada by age | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 2001 | 2021 |

| 15 + | 27% | 12% |

| 15-19 | 25% | 3%Table 2 Footnote * |

| 20-24 | 35% | 10% |

| 25 + | 26% | 13% |

Dependence and vaping products

There are many risk factors that can influence the development of nicotine dependence. These include both vaping product features (ingredients and delivery methods) that can allow the delivery of higher doses of nicotine, and individual factors such as the environment, age, genetics, existing mental health conditions and other dependencies.Footnote 40,Footnote 41,Footnote 42 Measuring nicotine dependence among those who vape is challenging, as we are still learning how people vape (including how much and how often), and vaping products continue to change. While progress has been made by adapting measures from cigarette smoking to vaping, more work is needed to standardize and interpret measures for nicotine dependence among those who vape.

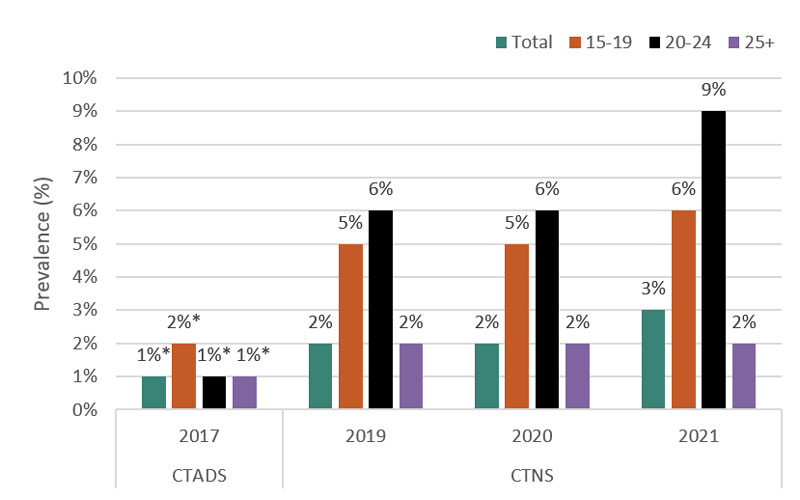

National surveys, academic literature, and public opinion research provide more insight into how dependent young persons and non-users of tobacco products are on vaping products and whether this has changed over time. Those who vape daily are more likely to experience dependence than those who report vaping less frequently, such as once in the past 30 days. Nationally representative surveys show that daily vaping among Canadian youth aged 15-19 increased from 2 percent (32,000 - moderate sampling variability; interpret with caution) in 2017 to 6 percent (120,000) in 2021, unchanged from 2019.Footnote 43 It is important to note that these data do not indicate whether it is the same people vaping each year or whether daily vaping is a behaviour that continues over time. Caution is warranted when comparing results of different surveys given the variability in how each survey is designed.

Figure 3 - Text Description

| Prevalence of daily vaping in Canada by age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2017 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| 15-19 | 2%Table 3 Footnote * | 5% | 5% | 6% |

| 20-24 | 1%Table 3 Footnote * | 6% | 6% | 9% |

| 25 + | 1%Table 3 Footnote * | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Total | 1%Table 3 Footnote * | 2% | 2% | 3% |

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys. |

||||

*Moderate sampling variability, interpret with caution.

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys.

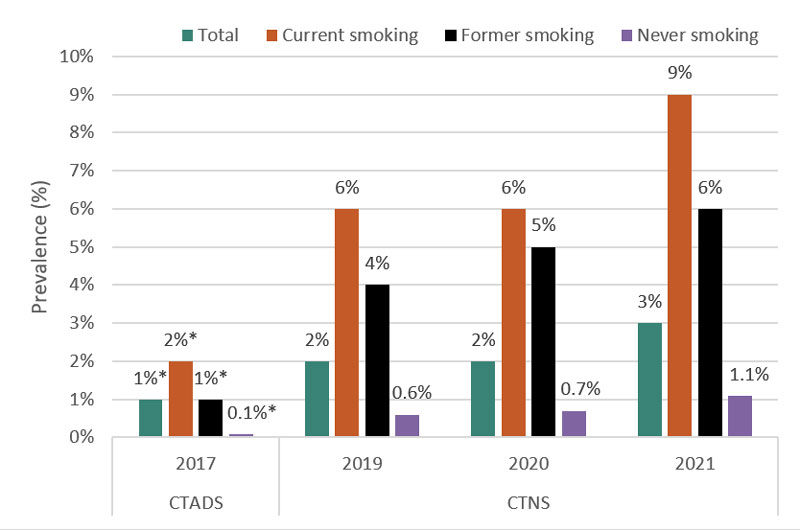

It is also important to look at the data with respect to those who smoke and those who do not smoke. Recent evidence suggests that, for those who smoke, daily vaping is associated with a greater likelihood of making a smoking quit attempt and abstaining from smoking, whereas less frequent vaping was not.Footnote 44 On the other hand, for those who have never smoked, daily vaping could indicate a dependence on nicotine that was not otherwise present.Footnote 45,Footnote 46 As indicated in Figure 4 below, among those who have never smoked,Footnote 47 the prevalence of daily vaping was reported as 0.1 percent (15,000 - moderate sampling variability; interpret with caution) in 2017, 0.6 percent (121,000) in 2019, 0.7 percent (136,000) in 2020, and 1.1 percent (218,000) in 2021.Footnote 48

Figure 4 - Text Description

| Prevalence of daily vaping among Canadians aged 15 years and older by smoking status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | 2017 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Current smoking | 2%Table 4 Footnote * | 6% | 6% | 9% |

| Former smoking | 1%Table 4 Footnote * | 4% | 5% | 6% |

| Never smoking | 0.1%Table 4 Footnote * | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.1% |

| Total | 1%Table 4 Footnote * | 2% | 2% | 3% |

|

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys. |

||||

*Moderate sampling variability, interpret with caution.

Note: Caution is warranted when comparing results from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey and the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, given the differences in the sampling frames, data collection modes and timeframes, and sample sizes of the surveys.

Evidence from academic literature and public opinion research indicates that many youth consider themselves addicted to vaping and want to stop. Findings from the 2019 International Tobacco Control (ITC) study suggest that approximately half of Canadian youth who vaped in the past 30 days considered themselves at least a little addicted and one third had strong urges to vape at least most days, an increase from 2018.Footnote 49 Youth using vaping products with higher nicotine strengths, reporting daily vaping, and reporting vaping for more than a year were more likely to report higher levels of perceived addiction.Footnote 50

Vaping Cessation

The current state of evidence as it relates to quitting vaping was also examined. To date, there is limited evidence available to determine how difficult it is for youth and non-users of tobacco products to quit vaping once they develop a dependenceFootnote 51 and which tools they might use to quit. However, the 2019 ITC, found that almost one in three youth who vape reported trying to quit in the past year.Footnote 52 It is unclear how many were successful but reasons for quitting included loss of interest or enjoyment, concerns about addiction or possible health risks, and reducing expenses.Footnote 53,Footnote 54

What Has Been Done

Since the legislation was enacted in 2018, the Government of Canada has undertaken a number of initiatives to protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products.

The Government of Canada responded to the rise in youth vaping by putting in place regulations to enhance awareness of the health hazards of using vaping products and protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to, and dependence on, nicotine that could result from their use. The Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations (VPLPR) made under the TVPA, which came into force in July 2020, require all vaping products that contain nicotine to display a nicotine concentration statement and a health warning on the products, and/or packaging, about the addictiveness of nicotine.

In addition to enhancing awareness of health hazards, the government also took action to reduce the availability of high nicotine concentration vaping products in the Canadian market, which were shown to be appealing to youth. The Nicotine Concentration in Vaping Products Regulations (NCVPR), which came into force in July 2021, set a maximum nicotine concentration of 20mg/mL to make them less appealing, especially to youth, with the goal of lessening youth exposure to nicotine. In 2021-2022, Health Canada resumed on-site inspections to monitor compliance with these regulations and the promotion prohibitions under the TVPA. Enforcement actions in response to observed instances of non-compliance include warning letters and seizures of vaping products.

The Government of Canada has also implemented new surveillance tools to provide timely data on vaping and tobacco use, including the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey,Footnote 55 and invested in a new national vaping module to the Canadian Community Health Survey.Footnote 56 These tools have produced nationally representative data to monitor smoking and vaping prevalence across Canada. The Government of Canada has acknowledged that youth vaping rates, while having leveled off, remain relatively high.The departmental response to the 2021 Evaluation of the Health Portfolio Tobacco and Vaping Activities (Management Response and Action Plan), committed to establishing interim targets on vaping prevalence among youth by April 2023. These targets will define concrete goals against which progress towards meeting the objectives of the legislation can be measured going forward. In addition, the Government has committed $14 million over five years in grants and contributions funding through the Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) to provinces, territories, non-governmental organizations, Indigenous organizations and individuals. This funding will contribute to efforts to protect Canadians from the harms of smoking and nicotine addiction, including supporting youth with tobacco and vaping cessation tools. SUAP also funded the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) to develop national evidence-based Lower-Risk Nicotine Use Guidelines, which compared the benefits and harms of using alternative nicotine delivery products, including vaping products.Footnote 57

What We Heard

While the vast majority of all respondents supported the Nicotine Concentration in Vaping Product Regulations, there was no consensus on whether additional regulatory measures are required to protect youth and non-users of tobacco products from nicotine dependence.

Most provinces, regional health authorities, health professionals and NGOs who participated in the consultation were in agreement that the current restrictions go some way towards protecting youth and non-users of tobacco products from nicotine exposure. They were also generally of the opinion that additional measures are needed, although there were varying levels of agreement about which measures should be employed and to what degree. These groups also advocated for a ban on the use of nicotine salts, which may make vaping liquids more appealing to youth due to their potential higher nicotine content. They also recommended prohibiting vaping devices that allow for high power or heat and prohibiting the use of additives, which facilitate inhalation and absorption of nicotine. In addition, they proposed implementing vaping product design standards to ensure uniform dosing of nicotine content. Finally, some NGOs emphasized that the restrictions in place should be continually reviewed and adapted based on emerging evidence and to ensure that the industry is not using new techniques to get around restrictions.

Conversely, there was consensus among the vaping industry that the current restrictions on nicotine concentrations are adequate to protect both youth and non-users of tobacco products and that no additional measures should be imposed. Instead, a few manufacturers and specialty vape stores raised concerns regarding the lack of specific safety regulations for vaping products. They recommended regulating product manufacturing to improve the quality and safety of vaping products sold in Canada. Members of the general public and those who use vaping products also agreed that the current restriction on nicotine concentration is adequate and asserted that more time is needed to assess the impact of this restriction prior to introducing additional measures. Moreover, some respondents who use vaping products reported that using products with a reduced nicotine concentration has caused them to return to smoking cigarettes since the amount of nicotine in vaping products is no longer satisfying enough.

Most academics who participated in the consultations focussed some attention on the "gateway effect" associated with vaping products. Most do not agree that youth who use vaping products are more likely to transition to smoking cigarettes. By way of example, some point to the increase in vaping since 2017, which, if vaping were a gateway, should have produced an associated increase in the rate of smoking among youth and young adults at the population level. Instead, they note that youth smoking rates are at an all-time low in Canada and the US. Some have concluded that the "gateway effect" has not been validated by evidence and that vaping products are reducing smoking at accelerated rates beyond predicted trends.

c) Protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products

A key objective of the TVPA is protecting the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products. The TVPA prohibits any person from furnishing a vaping product to a young person in a public place or in a place to which the public has access, including online-based retailers. Moreover, the TVPA prohibits sending and delivering of a vaping product to a young person.

The Tobacco (Access) Regulations (TAR) specify the documentation that may be used by retailers for the purpose of verifying age and identity for the sale of vaping products. The TVPA includes broader regulation-making authority, not yet in force, to set out the requirements for verifying age and identity of the person for vaping product sales.

The TVPA also includes regulation-making authority to prescribe the number or quantity of vaping devices (e.g., the number of vaping devices or the amount of vaping liquid) that must be contained in a package. Given that products sold in small quantities can be offered at low prices, specifying the permitted quantity or number of products per package may help prevent enticing youth with lower priced vaping products.

The prohibitions under the TVPA establish minimum standards that apply to youth across Canada. However, provincial and territorial legislation can establish higher standards, for example by setting the minimum legal age to access vaping and tobacco products above the federal legal age of 18 years old. Provinces and territories can also put restrictions on where vaping products can be sold in their jurisdiction.

Context

Before the new federal legal framework was enacted in 2018, vaping products with nicotine were not legally available for sale in Canada unless they had been evaluated for safety, quality, and efficacy under the FDA, and had received approval by Health Canada. To date, no vaping products have been authorized for sale under the FDA. Despite this, vaping products with nicotine were gaining popularity and being sold illegally, primarily through specialty vape stores.

Following the introduction of the new federal legal framework, vaping products with and without nicotine were legally permitted to be sold in Canada without prior approval under the FDA regime and are now sold in specialty vape stores, gas and convenience stores and by online retailers. The availability of vaping products at gas and convenience stores represented a major shift in the Canadian vaping product marketplace — one that substantially increased the availability of vaping products in many easily accessible locations across Canada.

In 2016, prior to the establishment of the new legal framework, the vaping market in Canada was estimated to be worth $500 million, with gas and convenience stores accounting for $7 million (1%) of vaping sales.Footnote 58 In 2021, three years after the new legal framework for vaping products was established and nicotine-containing vaping products began to appear in gas and convenience stores, the vaping market in Canada was estimated at $2.04 billion, with gas and convenience stores accounting for $631 million (31%) of vaping product sales.Footnote 59 Online sales of vaping products represented an estimated 21 percent of the market, valued at approximately $436 million. There are an estimated 1,489 vape shops and 25,000 convenience and gas stores selling vaping products in Canada.Footnote 60

In order to assess progress made towards protecting young persons by restricting access to vaping products, it is important to understand where young persons who use vaping products obtain them. In the 2021 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS),Footnote 61 respondents who had reported vaping at least once in the past 30 days were asked about their acquisition of vaping products. Among those aged 15-19 years, 52 percent (137,000) reported getting their vaping devices from social sources (which include buying from a friend or family member, asking someone else to buy vaping products for you, and having a friend or family member give or lend them to you). The remaining 47 percent (123,000) reported usually getting their vaping devices from retailers (specialty vape stores, convenience or gas, supermarkets, grocery stores, drug stores and online stores). Similar results have been reported for vaping liquids. The 2021 results are comparable to those from 2020.Footnote 62

In addition, the CTNS results reveal that the sources of acquisition of vaping products vary by age group. Young persons in the age group between 15 and 19 years rely more on social sources to acquire vaping products (52%, 137,000) than those age 20 years old and older (14%, 188,000).Footnote 63 It also suggests that some portion of the 47 percent of young people who vape, aged 15-19 years, are obtaining their vaping devices from retail sources despite being below the legal age. Health Canada conducted a survey of retail establishments in Canadian cities in 2019, to determine the willingness of retailers to sell vaping products to youth (15-17 years old) and found that 88 percent of retailers refused to sell vaping products to youth at retail locations across the country.Footnote 64

Public opinion research conducted in 2019, 2020 and 2021Footnote 65,Footnote 66,Footnote 67,Footnote 68 provided more insight into sources of acquisition for those who vape regularly (at least once a week for the past 4 weeks) compared to those who vape occasionally. Youth who occasionally vape are more likely to rely on social sources to get their products and do not own their own device. In contrast, those who vape regularly use social sources less, with specialty vape stores and gas station and convenience stores being the most common source for all age groups. Moreover, youth reported that it would be very easy if they needed to get a device tomorrow. They reported that they would try buying it from a local retailer not asking for ID, using false ID, asking an older friend or a student at school, waiting outside and ask a stranger to purchase a product for them, or buying it at school, online or on social media. This suggests that it may not be difficult for young persons to obtain vaping products from retail sources, despite both federal and provincial access restrictions being in place.

As for online sales, results from the 2021 CTNS showed that for Canadians aged 15 years and older, 10 percent (155,000) of those who vaped in the past 30 days were getting vaping products through online retailers (moderate sampling variability; interpret with caution).Footnote 69 To date, there is no estimate specifically for youth who may be purchasing vaping products online.

What Has Been Done

Prohibiting sales to minors has proven to be effective as a component of comprehensive tobacco control programs.Footnote 70 This approach has been used to limit access to tobacco products by both the Government of Canada and provinces and territories. Many provinces and territories have focused their tobacco and vaping control efforts on restricting retail access and have taken action to go beyond the minimum requirements in the TVPA. For example, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Northwest Territories, have increased the minimum age of sale to 19, and Prince Edward Island was the first to increase the minimum age to 21, in 2019.

Most provinces and territories have implemented either licensing, registration, or notification requirements for retailers. For example, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador have implemented provincial licensing of vaping product retailers and/or wholesalers. British Columbia has a notification requirement where age-restricted stores need to provide the province with notice of intent to sell and report product and manufacturing information prior to selling a vaping product. They must also report on their sales annually. A licence is not required to sell vaping products in Ontario, but registration with the local public health unit is necessary to sell flavoured vaping products other than tobacco, mint or menthol flavours in specialty vape stores where only those aged 19 and over have access. In Quebec, vaping retailers who wish to display their products at their retail outlet must submit a written notice to the provincial Minister of Health & Social Services. In addition, Quebec is the only province with a ban on online sales of vaping products. Finally, some provinces (British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador) have imposed a tax on vaping products and devices with a view to curbing youth access, while other provinces have stated that a vaping tax is forthcoming. The Government of Canada announced the introduction of a new excise duty framework for vaping products in Budget 2022, with implementation scheduled for vaping products manufactured on or after October 1, 2022.

In response to the rise in youth vaping, the Minister of Health sent a letter to retail associations in June 2019, to request that they remind their members of their responsibilities under the TVPA, including the prohibition on furnishing vaping products to young persons. In addition to education efforts, federal compliance and enforcement measures are in place to address complaints regarding access to vaping products, in collaboration with the provinces and territories. Provincial and territorial governments also have enforcement provisions in place and have conducted compliance verification and enforcement activities related to access to tobacco and vaping products at retail locations. Health Canada has also implemented compliance measures to monitor and inspect vaping product promotion accessible to youth online.

In April 2019, the Government of Canada consulted on potential regulatory measures to reduce youth access to, and appeal of, vaping products. Over half of the respondents were supportive of further restrictions to prevent youth from accessing vaping products online. Respondents provided suggestions on how to strengthen federal access requirements.Footnote 71 The current TAR contain provisions to verify the age of consumers. However, the TAR, which were enacted in 1999, were developed prior to online sales of tobacco and vaping products, that have come to play a more important role in retailing. Consideration is also being given to whether additional measures are needed to ensure that youth are not able to access prohibited products in this way.Footnote 72

What We Heard

All stakeholder groups supported restricting access to youth. A range of suggestions aimed at further limiting youth access were proposed by NGOs, provincial and territorial governments, health professionals and regional health authorities. This included raising the national minimum age for access to vaping products to 21, regulating the proximity between specialty vape stores and schools and prohibiting the sale of vaping products in all stores except specialty vape stores or adult-only vaping stores. Imposing a federal excise tax on vaping products was also recommended by provinces and regional health authorities as a way to curb youth vaping.

Specialty vape store owners recommended limiting sales to adult-only stores as the most effective way to minimize youth uptake. However, a convenience store association reported that their members have the experience and required training for selling various age-restricted products.

Other industry respondents suggested that the problem with youth access to vaping products lies with insufficient enforcement of existing prohibitions and that more needs to be done on this front before implementing new restrictions. Most submissions from industry stakeholders asserted that Health Canada should focus its enforcement resources on sales to minors, improve its collaboration with provincial authorities, and issue stronger penalties for any person caught furnishing vaping products to young persons.

There is consensus amongst all stakeholder groups that more needs to be done about online sales of vaping products. Industry stakeholders, provinces and NGOs argued in favour of strict online sales regulation, including the implementation of a third-party age verification process before accepting any online orders. Industry stakeholders requested guidance from Health Canada on how to verify the age of those who visit websites and social media pages. Some NGOs and provinces supported an outright ban on online sales of vaping products, as was recently done in Quebec.

d) Prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products

To ensure that the public has access to accurate information in order to make well-informed decisions about vaping products, the TVPA prohibits the promotion of vaping products that could cause a person to believe that their use may provide a health benefit or that compares the health effects of using a vaping product versus a tobacco product. However, the TVPA provides the authority to make regulations setting out exceptions, which would allow for the use of permitted statements that convey the health benefits of using vaping products or that compare the health effects of using vaping products to those associated with tobacco product use. This could allow manufacturers and retailers to use prescribed statements regarding the potential health benefits that vaping may offer in helping people quit smoking and comparison statements that align with evolving scientific knowledge.

The TVPA also prohibits the manufacture and sale of products containing certain ingredients that could give the impression that they have positive health effects or are associated with vitality or energy, which might make them attractive to youth and non-users of tobacco products. The use of these ingredients in manufacturing, including vitamins, mineral nutrients, amino acids, and caffeine (as listed in Schedule 2 to the TVPA) are prohibited, except in prescription vaping products. The promotion and sale of vaping products marketed as containing ingredients listed in Schedule 2 are prohibited. Other ingredients, which could also contribute to making vaping liquids appealing to youth, like colouring agents, were also banned. The legislation also includes regulatory authority to amend ingredient lists, and place restrictions on the promotion of products, should future evidence indicate that such ingredients act as inducements for young persons or non-users of tobacco to use vaping products. The use of flavour ingredients were not restricted under the TVPA, but the promotion of certain flavours listed in Schedule 3 to the TVPA (dessert, cannabis, confectionary, energy drink and soft drink flavours), including by means of the packaging, was banned.

The TVPA also provides the authority to make regulations to collect information from industry about vaping products, their emissions and any research and development (e.g., sales data and information on market research, product composition, ingredients, materials, health effects, hazardous properties and brand elements), and promotional activities. This would provide the Government with timely access to relevant information, especially information that is not publicly available, about the vaping product market and vaping product contents to better understand the impact of their use on the health of Canadians.

Context

The health hazards of vaping and potential health benefits that vaping may offer in helping people quit smoking have been researched and debated among scientists, policymakers and the health community for the past decade. While there have been advances and consensus reached in certain important areas, scientific uncertainties that were present in 2018 remain. Although scientific knowledge continues to evolve, there is sufficient evidence of harm to justify efforts to prevent the use of vaping products by youth and those who do not use tobacco products.

While vaping products are not harmless, there is also strong evidence to suggest that for people who smoke, completely switching to vaping is a source of nicotine that is less harmful than smoking cigarettes.Footnote 73 A recent systematic review examined the effectiveness of e-cigarettes; it found that vaping nicotine products do help people to stop smoking for at least six months and does so at a higher rate than traditional NRT use.Footnote 74

The vaping product market is constantly changing with the introduction of new vaping product technologies and novel product characteristics such as new ingredients, new flavours, and new devices for delivering the product. Moreover, unlike cigarettes, where products are virtually identical, vaping products are highly variable with variations that may introduce different risks. We are still learning about how such a diverse range of products affects health and what might be the long-term health impacts.

The review examined national surveys and found that the majority of Canadians hold misconceptions about the relative harm of vaping compared to cigarette smoking. A recent survey conducted in 2021 showed that only 17 percent of adults 20 and over who smoke and do not vape understood that vaping is less harmful than smoking cigarettes.Footnote 75 Not understanding the relative risks associated with vaping versus smoking could lead Canadians to make uninformed decisions about hazards to their health.

What Has Been Done

To prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products, along with restricting promotion that can be seen or heard by young persons, in June 2020, the Government introduced requirements under Part 2 of the VPPR that prohibit vaping products from being advertised without conveying a health warning. To further protect youth, the VPPR only allow advertisement in age-restricted places that youth cannot access.

To help ensure that Canadians are aware of the health hazards of vaping product use and nicotine addiction, in July 2020, provisions under Part 1 of the VPLPR came into force requiring all vaping products to display important health information. Products containing nicotine must display a nicotine concentration statement and a health warning about the addictiveness of nicotine. In addition, to allow consumers to make informed choices regarding the products they choose to use, all vaping substances must display a list of ingredients, regardless of nicotine content under Part 2 of the VPLPR made under the CCPSA.

On June 18, 2022, the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health, proposed the Vaping Products Reporting Regulations (VPRR) that would require vaping product manufacturers to submit information to Health Canada about sales and ingredients used in vaping products. These proposed regulations have been identified as a first step in a gradual approach to introducing vaping product reporting requirements, which could be expanded in future to support the Government in keeping pace with the rapidly evolving market and fulfilling its role as an effective regulator.

What We Heard

Provinces, regional health authorities and many NGOs believe that the current measures are not adequately protecting the public from being misled or deceived with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products. According to some of the above, positioning vaping as a product with potential health benefits when compared to smoking creates mixed messaging for the public. In addition, some of them asserted that industry tactics to label and package their products in attractive and deceiving ways create confusion about the health risks of vaping. Several submissions from provinces, regional health authorities and NGOs recommended adopting plain packaging, strengthening health warnings and establishing stricter advertising and promotion restrictions.

Some members of the general public and the majority of industry submissions asked that regulations be established to set out a selection of authorized statements about the relative risks of vaping products. Their request was supported by some academics. However, some industry stakeholders believe that they should not be limited to the use of only authorized statements and consequently they asked for broader permissions in communicating with consumers. Conversely, some NGOs and provinces continue to maintain that the long-term health consequences of vaping products are still unknown and therefore, cannot be presumed to be safer than combustible cigarettes.