Indigenous perspectives on end-of-life care, including medical assistance in dying: What we heard

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 963 KB, 36 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: December 2025

On this page

- Introduction

- Key themes from Health Canada's engagement

- Theme 1: Diverse perspectives on end-of-life care, including MAID

- Theme 2: Culturally safe, holistic care

- Theme 3: Access to health and social supports across the lifespan and at end of life

- Theme 4: Access to holistic, plain language education, information and resources

- Theme 5: Meaningful engagement and collaboration

- In their own words

- Conclusion and next steps

- Annex

Introduction

This report shares the major themes and issues from Health Canada's engagement with Indigenous Peoples on medical assistance in dying (MAID). Engagement took place from 2022 to 2025.

MAID and palliative care are health services delivered by provincial and territorial health systems as part of end-of-life care. Provincial and territorial health systems must adhere to the rules in the federal legal framework for MAID. The framework sets out strict criteria around who can receive MAID and under what conditions.

In addition, Indigenous Services Canada funds the delivery of end-of-life care through the First Nations and Inuit Home and Community Care program. Indigenous governments and organizations also may play a role in shaping end-of-life services to be more responsive to the needs of their communities and reflect Indigenous values and traditions.

Health Canada and Indigenous Services Canada have supported First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations and governments to lead their own engagement initiatives on palliative care and MAID, in keeping with the right to self-determination. As well, on MAID specifically, Health Canada hosted engagement activities, an online questionnaire and a national dialogue series in 2023-2024.

This report highlights the results of this engagement. It was prepared by Indigenous and non-Indigenous Health Canada staff located across Canada with experience in Indigenous health policy, nursing, public health and program administration. We are committed to cultural humility as well as continuous learning and training in cultural safety.

The reports of the engagement being done by First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations and governments are expected in 2025 and 2026. These reports will further inform this issue.

Context

MAID raises complex ethical and social questions, especially around balancing personal autonomy with protecting vulnerable individuals.

Many Indigenous Peoples recognize that MAID is a topic to be further explored from diverse Indigenous perspectives. It is acknowledged that for some Indigenous Peoples, discussing the topic of serious illness, death and grief can be difficult or taboo.

When considering Indigenous perspectives on MAID, it's important to understand and recognize the context of individual and collective effects of settler-colonialism on Indigenous Peoples' health and well-being, including on access to end-of-life care services. Historical and ongoing harms continue to shape the health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and to affect trust in health systems. This is well recorded in the series of reports produced by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The reports documented the truth of Survivors (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) of the residential school system and outlined calls to action towards reconciliation.

Canada's residential schools: the final report of the Truth and Recognition Commission of Canada

A culturally safe experience of death and dying is determined by the individual. It often includes the ability to remain at home or in one's community. In this setting, the individual is surrounded by loved ones, where culture and identity are respected and support provided through ceremony, family and community-based approaches to care.

However, access to culturally safe and appropriate care is often limited by systemic and structural barriers. Indigenous Peoples and communities continue to experience social exclusion, geographic and linguistic barriers, jurisdictional gaps and systemic inequities. These barriers further limit access to essential services. This includes primary care, palliative care, hospice care, and mental health and community-based supports that reflect diverse values, traditions and needs of Indigenous Peoples.

Access to this care may be especially limited for urban Indigenous people living away from their home communities, Indigenous people with disabilities and those living in Northern, rural or remote communities. These conditions, rooted in historical and ongoing settler-colonialism, directly impact health outcomes. They also limit access to the resources needed to uphold dignity, autonomy and a culturally grounded end-of-life experience.

For Indigenous Peoples, death and dying are part of a broader understanding of health and deeply connected to culture, identity and Indigenous self-determination. This holistic understanding of health includes:

- kinship networks

- Land-based healing

- revitalizing Indigenous languages

- spiritual, physical, mental and emotional aspects of well-being

- role of families and communities in caregiving and decision-making

- re-connecting with the land, water, people, communities and Ancestors

- engaging in traditional (cultural) teachings, cultural protocols, healing ceremonies, spirituality and knowledge systems

For many, caring for one another includes supporting loved ones through serious illness or death. This is a deeply held value rooted in family, community, respect, cultural values, traditions, teachings and collective well-being.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and deeply thank the following First Nations, Inuit and Métis Elders, Knowledge Carriers and Knowledge Sharers. You brought knowledge, comfort and spirit to this important work, provided traditional openings, closings and reflections during the dialogue sessions or helped review the final report.

- Elder and Knowledge Keeper Albert McLeod, with ancestry from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation and the Métis community of Norway House

- Elder and Knowledge Keeper Geraldine Manson, Snuneymuxw First Nation

- Elder and Knowledge Keeper Jo-Anne Gottfriedson BGS/CED, T'kemlups te Secwepemc

- Elder Evelyn Willier, Sucker Creek First Nation

- Elder Joe Blyan, Buffalo Lake Métis Settlement

- Elder Richard Jackson Jr., Traditional man on a healing journey, Retired Veteran, Lower Nicola Indian Band, British Columbia

- Gail Turner, retired nurse, Nunatsiavut

- Monique Fong-Howe, Knowledge Sharer, Mi'kmaw Native Friendship Centre, Halifax

- Navalik Helen Tologanak, Inuit Elder from Cambridge Bay, Nunavut

- Randi Gage, Knowledge Keeper and Manitoba Indigenous Veteran

- Sage Elder Raymond Gros-Louis, Wendat Nation

We thank the First Nations, Inuit and Métis community members, practitioners and leaders who shared their views, knowledge and experiences in the dialogue and validation sessions.

We also appreciate and honour the many Indigenous organizations and governments that worked with us through this process. You provided input into the design and content of the online questionnaire, the dialogue sessions and the process, and reviewed this final report.

We also thank:

- Mahihkan Management Solutions for coordinating and managing the national dialogue sessions

- Indigenous trauma counsellors for providing mental health supports to participants and care and guidance throughout this process, especially to Alana Gros-Louis, Registered Provisional Psychologist, Indigenous Psychological Services

- Erica Bota from ThinkLink Graphics for bringing the dialogue sessions to life in visual format and for the images used in this report

- Luc Lainé, Marty Landrie, Eva Papigatuk, and Donna Smyl who skillfully led the dialogues with care and grace

- Lisa Weisgerber, for honouring the stories shared by participants, for using a Etuaptmumk-Two-Eyed Seeing approach to review and summarize the perspectives of community members, and for translating stories and emotions into written word

Mental health resources

This report contains information on end of life, death, medical assistance in dying, suicide, colonialism, residential schools and other related topics. We recognize that the content may be sensitive or difficult to deal with emotionally. Please take care while reading.

Learn more about available mental health supports.

Report summary: Findings from Indigenous engagement on MAID

- A diverse range of perspectives on end-of-life care, including on MAID: There was a general recognition and acceptance of death as a natural part of life. The importance of living a good life and having a peaceful, comfortable and dignified death was raised. Some participants were open to MAID. Others were open to MAID only in certain circumstances (for example, only when death was reasonably foreseeable). Some did not support MAID under any circumstances.

- Culturally safe and holistic care: Participants shared that culturally safe care means physical, spiritual, emotional and mental well-being. It begins with acknowledging and addressing past and ongoing harms and addressing anti-Indigenous racism and discrimination in the health care system. It also means upholding key Indigenous health obligations outlined in foundational documents. These include the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada's Calls to Action and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Culturally safe care can be supported by Etuaptmumk-Two-Eyed Seeing. This approach brings together the strengths of Western and Indigenous ways of knowing, creating a more holistic and inclusive perspective.

- Access to health care and social supports across the lifespan and at end of life: Participants highlighted the importance of improving access to health and social services across the lifespan, including at end of life. Participants raised concerns that people might choose MAID if they did not have appropriate access to culturally safe services, including symptom and pain management, specialized care, home care and palliative care. The importance of staying in one's preferred location of care at end of life, including when accessing MAID, was raised. Currently, this is not possible for many First Nations people, Inuit and Métis due to limited access to health care in community.

- Access to holistic, plain language education, information and resources: Participants spoke to the need for plain language information on end-of-life care options, including MAID, available in multiple Indigenous languages. They stressed that these resources must be accurate, up-to-date and developed in collaboration with Indigenous communities.

- Calls for further meaningful engagement: As MAID is a new and evolving health service in Canada, participants voiced their concern that more engagement is necessary. Federal, provincial and territorial governments, as well as health authorities, are encouraged to continue meaningful engagement.

Key themes from Health Canada's engagement

Theme 1: Diverse perspectives on end-of-life care, including MAID

Participants expressed a range of perspectives on MAID that reflect their cultural, spiritual and personal beliefs. These many perspectives illustrate the complex and multifaceted nature of how different communities, families and individuals approach the concept of death and dying, and MAID.

Participants felt that death is an inevitable part of the life journey. Many said that death is not the end, but the start of a new journey, a transition to the Spirit World or after life, or a reunion with the Land and Ancestors. A few said the focus is not on end of life itself but on living a good life and supporting others in their lives.

Many spoke to the need for a peaceful, comfortable and dignified death. Participants stressed that life with dignity must precede any conversation about death and dying. Individuals need to feel valued and respected, and to have access to health care providers who are compassionate, caring, kind, respectful and non-judgmental.

"I think it is important for one to be able to make decisions about both living and dying when having complicated health issues and pain and suffering. Living and dying with dignity is important."

Participants expressed a diverse range of views on MAID. These fell into 3 broad views:

- open to MAID

- open to MAID only in certain circumstances

- opposed to MAID based on cultural, spiritual, ethical or systemic concerns

Participants also shared their lived experiences with MAID. These perspectives reflect both traditional and adaptive worldviews. Some participants described MAID as consistent with values such as personal autonomy and dignity. Others felt that MAID should be approached with caution, rooted in community obligations and the importance of spiritual continuity.

In sharing their lived experiences, participants highlighted how these views are shaped by individual, family and community contexts, as well as broader histories of colonialism and systemic inequities.

Image 1 - Alternative text

A group of people is standing with their arms around each other. One person says, "I may not agree with it, but it's a personal choice."

1. Open to MAID

Many participants said that MAID aligns with their worldviews or values of personal autonomy and dignity. They stressed the right of Indigenous Peoples to practise self-determination and to choose how they wish to die.

Some participants said MAID is a personal decision. It's a way to avoid intolerable pain and suffering and to ease the burden and stress on family or loved ones. It's also an opportunity to die with dignity, at home, surrounded by loved ones with ceremony and connection to the community. Others said it's a way for a person to exercise control over their own bodies and lives, and it requires great courage.

Some participants who had a loved one choose MAID found the process to be peaceful and dignified and that it allowed for a chosen, respectful transition. They stressed the importance of choice and the end of suffering, with one describing the process as "beautiful and peaceful". One participant said that MAID helped their sister, who was in extreme pain, transition to the Spirit World with dignity and respect.

Several participants said that MAID should be an option for those with severe mental illness. They shared concerns that individuals suffering solely with a mental illness may consider taking their own lives since they are not eligible for MAID, and would miss the opportunity to be surrounded by family and loved ones at the time of their death.

Participants also noted that MAID is not always a new concept. Before colonization, some Indigenous cultures engaged in similar practices for people at their end of life.

"I remark on the courage and bravery it would even take for someone to even explore MAID. I try to reflect on the Seven Grandfather Teachings. There is a protocol for MAID. It's not just I want it and I'm going to get it."

"MAID would allow a person their right to choose. During all stages of life, we encourage, support and advocate for our patients' rights. We need to include the right to die with dignity."

2. Open to MAID only in certain circumstances

For some participants, MAID is only acceptable under certain circumstances, once all other options for alleviating suffering had been exhausted.

Other participants said MAID should not be an option for those with mental illness. The emphasis should be on promoting life and mental health care for these individuals. Still others voiced concern that people may choose MAID due to a lack of access to health care and mental health services.

Many participants felt that the distinction between MAID and suicide is not always clear. These sensitive topics require further discussion in a safe and non-judgmental forum. These topics should be approached holistically and incorporate cultural, spiritual and community perspectives.

Participants felt it was important to monitor MAID cases involving mental illness, given these concerns.

"MAID is an option in my opinion. I feel that if someone has a life-limiting disease and they may suffer with uncomfortable symptoms that may be difficult to control, that this is an option. I do have a hard time accepting mental health reasons to choose to use MAID."

3. Opposed to MAID based on cultural, spiritual, ethical or systemic concerns

For some participants, MAID conflicts with their own beliefs and values. They said that an end-of-life decision should not be made by humans and to control it through MAID was to overstep human boundaries. Death should be left in the hands of a Creator, God or higher power.

Others view MAID as a continuation of colonial policies or another way to control and harm Indigenous Peoples. For them, MAID is the same as murder, genocide or a sin and the systematic euthanasia of vulnerable people. Some participants felt that an individual could be coerced into choosing MAID, with one participant saying that Indigenous Peoples may be "bullied into a decision."

"People in situations of vulnerability may be or feel coerced to pursue MAID because of disparities in social determinants of health and a lack of health services."

Some participants feared that MAID might normalize or even encourage suicide. There's an urgent need for accessible, culturally appropriate health care, mental health care and life-promotion initiatives.

"MAID is something that is really new to us and our older generation are still against it. In my community there are people who are Christian and that would not be allowed in that context and then there are people who follow traditional ways and it is something where there are many mixed feelings about it in our community."

"My husband and I are very spiritual. We wonder if the deceased Ancestors know to come when someone receives MAID. Will they know to be there for a MAID death? The Ancestors need to greet the dying person as they pass to the other side, or they are left in limbo. It's like the children in residential school who get left in limbo. This uncertainty has been weighing on my heart."

Theme 2: Culturally safe, holistic care

Participants stressed the importance of culturally safe and holistic care at end of life. Culturally safe care as part of MAID means that the services are respectful and responsive to the cultural identities and needs of Indigenous Peoples.

"Cultural safety is not possible until the larger issues of disparities, discrimination and racism are addressed at a societal level. Canada needs to implement culturally safe and trauma-informed living care before implementing MAID."

We heard that a holistic approach that includes Indigenous health and healing models, ways of knowing and Indigenous cultural traditions was important.

"I believe that Western medicine and Traditional Medicine (in the Indigenous context) can work together to create a holistic approach to death and dying. We all have a role to play and in working together can create a beautiful, culturally safe death."

Participants said that a Two-Eyed Seeing approach (integrating both Western and Indigenous approaches in the delivery of care) was especially important for MAID and integral to dignity in dying.

Cultural safety is defined by the person receiving care. It addresses the physical, mental, emotional and spiritual realms of being. Participants shared that cultural safety at the end of life means:

- a sense of trust and mutual respect

- access to kindness, compassion, empathy, respect, dignity and trust

- freedom from discrimination, racism, judgment, bias and religious interference

- recognition and respect by health care providers for the unique cultural needs and perspectives of individuals

- person and family-centred tailored care that honours collaborative and informed decision-making, self-determination and autonomy

Some participants reinforced the importance of MAID assessors and providers getting to know, listen and learn about Indigenous Peoples and the communities they serve with sensitivity and humility.

"The staff and people who assist families with MAID are responsible for making that process culturally safe."

Participants said that ongoing engagement and conversations with Indigenous communities would ensure that end-of-life care, including MAID, reflects the values and beliefs of the community and honours cultural and spiritual practices.

Acknowledging and addressing past and ongoing harms

Participants said it's important to acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples have experienced and continue to experience colonial violence, cultural assimilation, discrimination and racism in Canada. These historical and ongoing injustices have led to significant social and health disparities and barriers to accessing care, including end-of-life care.

The impact of colonialism has caused a disconnect from and loss of land, culture and language. This has further added to the intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous Peoples, families and communities.

One participant said:

"Indigenous cultures have these systems to care for and ensure proper protocols for everyone are in place. Their traditions have more in place mentally, emotionally, spiritually and physically to make the situation clear safe, loving and caring for all involved. It is the destruction of tradition and culture from colonization and cultural genocide and forcing a colonial view and practice that has left people and families vulnerable, and uncared for, stuck in pain and grief, potentially anxious and angry."

Due to this history of colonial violence and ongoing harm, some participants strongly advocated for the need for Indigenous-led processes and cultural safeguards for MAID. They felt that these measures would help protect individuals from coercion, neglect or further abuse, harm and discrimination.

Participants voiced concerns that systemic racism, medical paternalism, social determinants of health or gaps in care may influence decisions around MAID for reasons other than an individual's personal will or autonomy.

"I had a family member who got MAID and a big barrier was the settler's religion as it applied a lot of pressure. Making the decision for MAID should not come from outsider pressure as this creates issues. I find it extremely sad that some people cannot access MAID, that some people don't have a choice to access it, based on external ideas that are not part of our culture. Outside religion is a barrier."

Some said that community-led oversight mechanisms would ensure MAID is not used as a response to inadequate access to health care, social supports and the social determinants of health.

Addressing racism and discrimination

Participants stressed that ongoing anti-Indigenous racism and discrimination in the health care system must be addressed. Systemic racism and discrimination in health care have led to:

- lack of trust

- fear of being judged

- fear of reaching out for help

"Most FNIM (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) people want nothing to do with the health care system, period."

"First Nations with invisible disabilities experience extreme fear in accessing the health system due to a traumatic history and the idea that the health care system is not designed to help them."

Participants said that racism and discrimination make it difficult to navigate the health system. The system prevents people from seeking necessary care and support. This leads to serious consequences, including physical, psychological, spiritual harm, trauma, under-diagnosis and misdiagnosis, even death.

"We continue to face racism and discrimination in health care settings that bring further harm and trauma to us. Hospitals and health care agencies are built on colonialism. This too impacts a person's decision for MAID."

Within this context, participants stressed the importance of implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada's (TRC) Calls to Action. One person said, "MAID without implementing the TRC recommendations and calls to action is genocide."

They also spoke to the importance of implementing both the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to protect the rights and well-being of Indigenous Peoples. By taking these steps, governments, health systems and health care providers can create a more just and equitable future for Indigenous communities.

Education and training on culturally safe care

Participants spoke about the importance of education and training on trauma-informed and culturally safe care for those providing end-of-life or after-death care. This includes giving practitioners the skills they need to recognize and respond to trauma:

"Trauma-informed end-of-life care could be understanding that people may have significant mistrust, that there needs to be relationship and building of trust, that fulsome explanation of the situation and options for care are given, so the patient and family feel they can trust the care being provided."

Participants said that education and training should be experiential, community-informed and practical. It should use a strengths-based and celebratory lens that values Indigenous Knowledge and cultural practices to encourage more empathetic and holistic care.

Training on MAID must be tailored to the needs of community health nurses, home care teams, paramedics, allied health care providers and other health and social service providers.

"In order for Indigenous people to have any confidence that the MAID process will be culturally safe and trauma-informed there needs to be an extraordinary amount of time, resources, attention and willingness given to creating, training, developing and supporting teams of MAID medical and other professionals to specifically serve Canada's various Indigenous communities."

Some participants felt that support after the clinical assessment was lacking. The process is too medicalized and paternalistic, particularly for Indigenous Peoples:

"The assessor is rarely able to understand Indigenous ways of thinking, knowing and being and could not reflect much in the way of cultural capacity or competence. The process very much reflects the medical model in being treated like a body and is very paternalistic. It is potentially very difficult and damaging for Indigenous Peoples given the medical experimentation that has been done in the past."

Others voiced concerns with the MAID process, citing the following:

- a shortage of available MAID practitioners

- difficulties in qualifying for the procedure

- absence of culturally grounded care providers

- invasive, personal questions that probe into past traumas

- inadequate diagnostic tools that are not culturally appropriate

- a time-consuming application process that may delay access to MAID

- policies that restrict where MAID assessment and provision can occur

- concerns about losing capacity before a decision was rendered on MAID eligibility

- a lack of cultural relevant assessment and provision processes for MAID, including considerations for the social determinants of health and embedding land-based end-of-life care, spiritual and cultural processes into MAID

Indigenous-led end-of-life care

Participants spoke of the need for Indigenous-led navigators, services and facilities in end-of-life care decision-making. Health and social systems are complex, which makes it challenging for people trying to navigate and access these systems.

"Part of my job is service navigation. People just get dropped into the health care system when they arrive south to access services. For example, how do you get a transit card, where do you go grocery shopping, where are the Inuit services?"

Particular emphasis was placed on the role of Elders.

Participants stressed a need for more Indigenous end-of-life guides or doulas, navigators, community liaisons and interpreters.

There was also a strong call to recruit and retain more Indigenous providers in the following professions:

- nurses

- paramedics

- social workers

- palliative care doctors

- cultural support workers

- MAID assessors and providers

"I think an Indigenous doctor (if possible) should be the one doing MAID within the Indigenous communities."

Accessing family doctors and nurse practitioners, including MAID practitioners, is already difficult, even more so for those who are Indigenous.

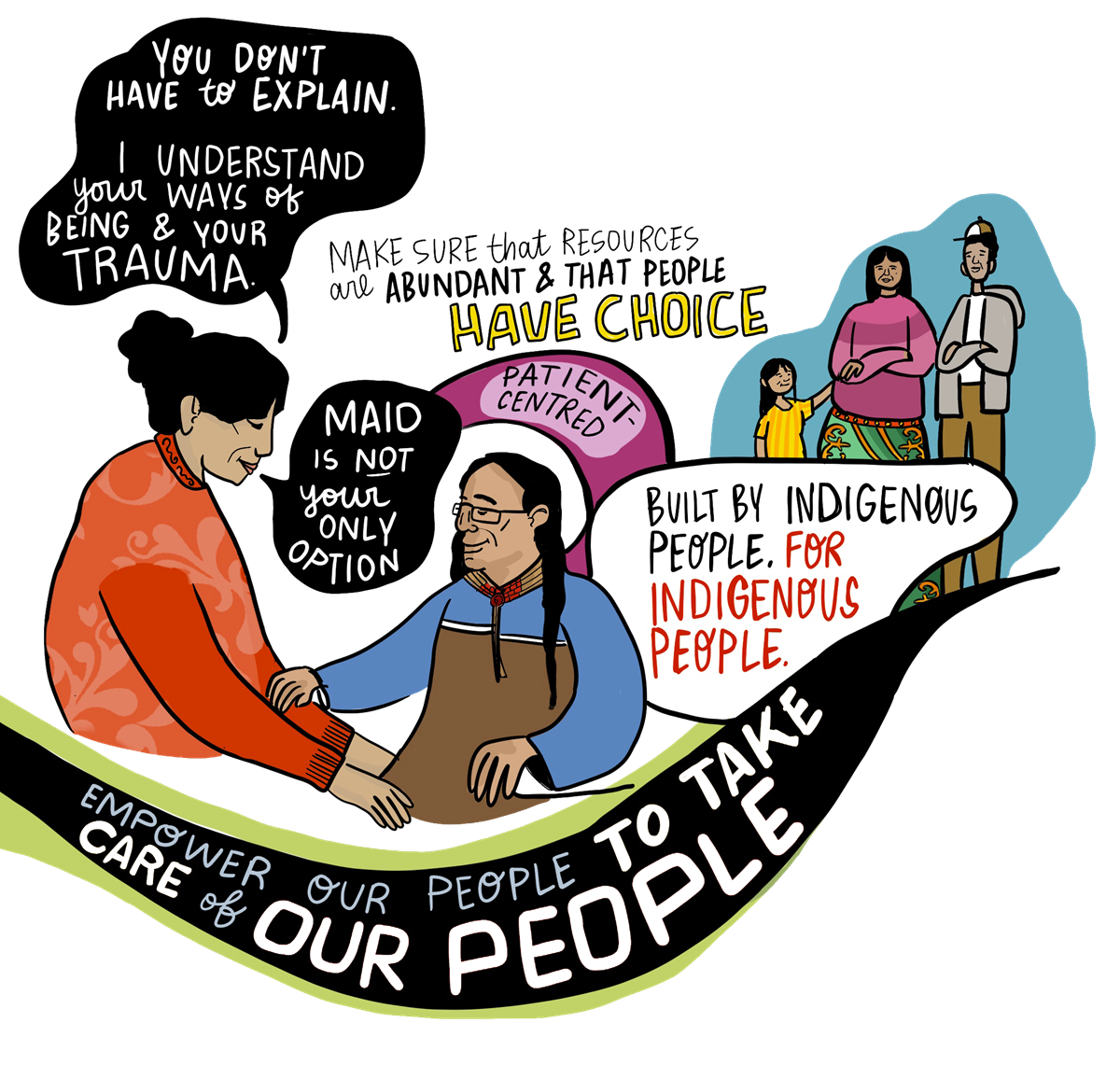

Image 2 - Alternative text

Two images showing a health care provider helping a patient and a small family to highlight the message that Indigenous people have choice.

Long description:

A health care provider is helping a patient. She says, "You don't have to explain. I understand your ways of being and your trauma" and "MAID is not your only option".

There is also an image of a small family above and to the right of the large image. Around it are words that say: "Make sure that resources are abundant and that people have choice." Another saying next to it is "Built by Indigenous People. For Indigenous People."

In small, Northern, rural and remote communities, health care providers face workforce shortages and complex dual roles. These dual roles can raise ethical tensions, particularly when providers are community members. Limited health care services, staffing, training and community infrastructure further compound these challenges.

Participants noted that many Indigenous providers deliver care across the lifespan, from birth to end of life. Care is often provided by just a few individuals.

Care providers, including MAID practitioners, need support to:

- prevent burnout

- navigate relational conflicts and ethical complexities

- cope with grief and loss, fear and stigma associated death and dying and MAID

We also heard it can be difficult to support families and loved ones when protecting patient privacy and confidentiality.

Participants said it's important to include Healers, Medicine People, Elders, Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous end-of-life guides, death doulas and navigators in end-of-life care services. One participant said, "I think Elders should be a part of end-of-life treatment so we can get final guidance and understanding." Another participant said that patients and families need support and guidance from "Elders, Spiritual Leaders, Healers (Grandmothers) from within the loved one's specific cultural community."

Some noted the need for formal recognition, training and financial and travel support to support Elders, Spiritual Leaders and others in their end-of-life services.

We also heard there's a need for Indigenous-led end-of-life care facilities that are grounded in Indigenous Knowledge and cultural practices. These community-based facilities can offer care that truly reflects the needs, values and traditions of Indigenous communities.

"Something that preoccupies me is that as people get older and sickly, they often end up in non-Indigenous hospitals. This is a place where I have seen racism alive and well in a system that has difficulty in understanding Indigenous practices and approaches. I want to have places within our communities where family will surround them, so if someone does make that decision for MAID, they can do that with comfort and with any ceremonies they wish."

Cultural practices and support from clinical counsellors and staff were highlighted as important components of a positive MAID experience. One participant said, for example:

"We had our first MAID process within the last 6 months. The experience was heart-wrenching and beautiful at the same time. The client chose to have cultural practices as a part of her journey. We also ensured we had clinical counsellors and other support staff on-site for the family and friends."

Participants also noted the importance of funding and promoting distinctions-based and tailored approaches to end-of-life care services and policies led by and for First Nations, Inuit and Métis. A distinctions-based approach recognizes that First Nations, Inuit and Métis are distinct Peoples. They have unique cultures, histories, rights, laws and governance, interests, priorities and circumstances.

Participants said that barriers should be removed to access funds to create Indigenous-led programming and content. These initiatives should be developed by a Indigenous-led institution.

Nation sovereignty and self-determination must be respected when developing MAID policy and collecting and interpreting end-of-life care data, including MAID data. Also, First Nations, Inuit and Métis should play a clear role in developing policy on MAID.

Some participants said the term "distinctions-based" does not fully reflect the many intersecting factors that shape the identities and lived experiences of First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Policies, programs, services and legislation around end-of-life care should meet their unique needs and recognize their diverse realities.

Supporting connection to family, community, language, culture and spirituality

"I think that no one should die alone, and be able to do so in a space that they wish. To be surrounded with friends and family and have the choice to practise their traditions as they choose fit."

Many participants said the family and community must be involved at a person's end of life. Community support is crucial in the healing and well-being of Indigenous Peoples. Also important is having a space to gather with family and visitors, prepare and share traditional and country foods, and connect to the land, place, home or community.

Health care facilities should create comfortable and adequately sized spaces to accommodate large families, allow for community visits and encourage the sharing of food. Such spaces would also provide "access to an intergenerational space, bringing together Elders and youth to foster a sense of community, despite being far from home."

Participants noted that culturally safe MAID services should make space for cultural and spiritual practices. These practices are essential to dignity at the end of life and vary among individuals and communities. Examples of practices include:

- singing

- praying

- smudging

- drumming

- storytelling

- Land-based healing

- participating in ceremonies

- harvesting and using medicines

Image 3 - Alternative text

A colourful banner with a tree stresses connection to land, culture, community, family and friends. A blue ribbon highlights "ceremony".

To uphold cultural and spiritual continuity, participants said the right to ceremony, Land-based end-of-life care, and cultural and spiritual practices must be embedded in MAID protocols. Some participants said that access to these supports, along with family and community-based care, may even reduce the desire to pursue MAID.

We also heard that language is often a barrier for Indigenous Peoples, particularly those living in Northern and remote communities. The language barrier can make it difficult to access culturally safe end-of-life services, including MAID.

"There is a lot of medical terminology that don't have words in Inuk languages, so interpreters have to figure out how to translate it in a way that makes the most sense. There should be courses on how people can support Inuit who do not speak English and have supports for interpreters as well."

Supportive decision-making

Participants stressed that supportive, informed decision-making is important in culturally safe end-of-life care. Individuals and families need clear, culturally appropriate and comprehensive information about diagnoses and all care options to help them make informed decisions.

Many participants said that people need time to make decisions about end-of-life care. Others pointed out the need for support for other important aspects around end of life, such as funeral planning, wills and estate planning.

While some participants supported personal autonomy, others noted the importance of collective decision-making grounded in family, community, cultural traditions and teachings. In some communities, decisions about MAID are not solely made by individuals, but are often approached in relationship with family members, Elders and the broader community.

Indigenous Elders, leaders, scholars and academics who understand MAID should be involved in MAID assessments through community-led decision-making processes.

"I recommend that an Indigenous person be on the assessing committee."

Theme 3: Access to health and social supports across the lifespan and at end of life

Participants stressed the need to improve access to health services, especially in rural, remote and Northern communities. Improved access would ensure MAID is a truly informed and voluntary choice. They also stressed the importance of enabling end-of-life care in preferred locations and called for trauma-informed, culturally relevant grief and bereavement supports for families and caregivers.

Access to health services

Many participants noted that people should have access to MAID regardless of where they live, as access can be challenging in rural, remote or isolated communities. Jurisdictional and geographic barriers must be addressed to support access to MAID services.

"MAID can often be misrepresented, but it is a choice for people if they want it, resulting from advocacy. MAID can be a beautiful choice, and we need to make sure it is an equitable choice in Canada, including being able to access it no matter where you live."

Concern was also voiced that people would choose MAID if they couldn't access health care services such as medical treatment, mental health supports, adequate symptom management and palliative care.

"Before we begin to provide 'death with dignity', we need to provide the opportunity for life with dignity. That is absolutely not possible in this country yet."

We heard from participants that systemic issues could influence some individuals to consider MAID. They cited social isolation, racism and discrimination, housing insecurity, poverty, medical paternalism and gaps in care as systemic issues.

In particular, participants stressed that decisions around MAID must not shaped by unmet needs or structural barriers. Decisions should be fully informed, voluntary and grounded in culturally safe, holistic care.

"The morally distressing question is how can we offer MAID when we don't offer equitable access to any health care to Indigenous Peoples across this country?"

There were concerns that expanding eligibility to MAID without strengthening primary care services and holistic wrap-around supports would worsen health inequities. This is especially critical for people with disabilities and people living in Northern, rural and remote communities.

"I take issue with the framing of MAID as a personal decision, as it is a decision in the context of poverty, unstable housing, concerns about going into hospital and not being able to pay rent, not being able to buy nutritious food to manage disease."

Some participants were concerned that people may choose MAID if they cannot access palliative care or other treatment options.

"If someone does not have access to palliative care or primary care, it is impossible to put safeguards in these particular cases. This is about choice, but context is crucial. If basic needs are not met, how can there be a conversation about MAID?"

Métis participants said that persistent exclusion of Métis from federal health programs directly affects access to mental health services, palliative care and culturally safe supports. Expanding MAID without addressing Métis health inequities and the lack of Métis-specific programming may deepen existing harms and undermine principles of equity.

We also heard that the financial, emotional and social burden of medical transportation is a concern for people who live in Northern, rural and remote areas. It's often challenging for patients and family members to cover the costs of medications, treatments and travel expenses.

"People are driving 4 to 5 hours for dialysis. These inequities might lead to more First Nations and Métis people to choose MAID."

Communities in these areas also face high staff turnover and staff shortages in the health and social sectors. This hinders continuity of end-of-life care and the ability to communicate with health care providers.

Financial supports to cover the costs of accommodation, meals and travel are also needed for patients and families who must travel for treatment and end-of-life care, including MAID.

Image 4 - Alternative text

A rural skyline showing sky and land with the words "rural and remote communities don't have the same access to resources."

Some participants were concerned that people would choose MAID due to a lack of access to adequate mental health resources and services. We also heard about the importance of stable housing, adequate income and connection to family, culture and community.

For MAID to be a truly informed choice, some participants said that more effort was needed to:

- eliminate systemic disparities

- support access to culturally safe, holistic care

- support people in the broader social determinants of heath

- enable access for Métis federal supports, programs and health benefits

- promote access to health services and social supports across the lifespan, especially for persons with disabilities and those living in Northern, rural and remote areas

Participants said:

"I think there is a need for not only Indigenous Peoples but for all people to have access to accessible, affordable housing, affordable food, access to family doctors, social support, mental health and addiction supports so these do not influence someone's choice for MAID."

"Much work needs to be done to provide MAID in a safe society that cares for the vulnerable. Creating a safe society to provide MAID cannot be separated from lack of access to affordable, stable or supported housing, affordable food, access to palliative care, family doctors, mental health and addictions treatment options. Canada's history of genocide, that has caused the physical death of family members, as well as suppressed our languages and taken our land, as well as the ignorance of our accurate history, has impacted Indigenous Peoples' social determinants of health."

Supporting preferred locations for end-of-life care

Participants stressed the importance of helping a person stay in their preferred locations of care at end-of-life, including when accessing MAID. Currently, it's not possible for many First Nations people, Inuit and Métis to stay in their homes and communities at their end of life.

"Our Elders are given a holistic type of care when in the community. At our local hospital our Elders are treated as a 'diagnosis'. There is no human touch factored into their care. Our Elders remain a vital component in our community up until they have journeyed. Their words are always heard."

"As residential school survivors they know all too well they were taken out of their community as children, losing a lifetime with their parents. As Elders, they don't want to be taken out of their community again, to start their journey."

Addressing jurisdictional and geographic barriers is necessary to support continuity of care and access to palliative and end-of-life services, including MAID. This is especially true in Northern, rural and remote communities where people must leave their communities to access care or to care for a loved one.

We heard that being away from home can cause social isolation, emotional, cultural, spiritual distress and be a financial burden.

"Having loved ones, family and community support, particularly during times of illness and end-of-life care, is important. I am concerned about government regulations limiting the number of family members who can visit a hospitalized loved one, especially as many Inuit communities lack hospitals and must travel long distances for medical care. The absence of hospice care and insufficient staff in local health centres exacerbates the issue, forcing Elders and sick individuals to be far from home during critical moments. The emotional and financial burden of distant medical care underscores the desire for family presence and support."

Some participants were concerned about the impact of institutional policies on a person's ability to receive care in their preferred location of care. Since MAID was legalized, several faith-based hospitals, long-term care homes and hospices in Canada have enacted policies that prohibit MAID from taking place on their premises. Thus, someone who requests MAID may have to transfer to another facility, despite the pain and distress this may cause. Some participants said these policies result in people being denied or facing delayed access to MAID, palliative care or hospice services.

Grief support for family and caregivers

Participants said that death can be a sacred and spiritual experience. It can also be complex and traumatic. Witnessing a loved one's suffering, whether in the context of MAID, end-of-life care or other illnesses, can be difficult emotionally.

Participants spoke about the need for holistic wrap-around grief and bereavement resources and mental health services to provide support before and after the loss of a loved one. Some felt that such services, resources and supports should be trauma-informed, culturally relevant and tailored to different age groups (for example, children, youth and Elders).

Participants advocated for culturally safe grief and bereavement supports in Indigenous languages, provided by a trusted source. MAID-specific resources and supports are also important.

"One cannot know what is involved in choosing MAID until one is in the position of considering it or desiring it for themself. Patients and families need support to navigate the grieving process and avoid trauma after the procedure."

Access to culturally appropriate, trauma-informed counselling, mental health supports is crucial for those considering MAID and their families. There should supports for family members, loved ones, caregivers and community members who may face complex emotional, ethical, relational, cultural and spiritual challenges throughout the MAID process. Peer support groups or networks are also important.

In some communities, especially among older generations, there is a taboo or fear around discussing death or dying, which can complicate conversations about MAID. The decision to seek MAID can also elicit grief before and after death. There may also be conflicts and divisions among family members and community members who have different beliefs. Providing grief and bereavement supports and information in a respectful and caring manner can address these concerns.

Participants said it's important to provide holistic support to family and caregivers, including healers and care providers, to prevent burnout. Caring for people who are both seriously ill and seeking MAID is emotionally challenging. These supports should be available before and after death.

"There should be federal funding to uplift the Helpers in a community."

Theme 4: Access to holistic, plain language education, information and resources

There is a significant knowledge gap for families and caregivers on end-of-life care options. Participants cited the lack of information on advance care planning, home care, palliative care, pain and symptom management, community supports, and MAID.

Many participants said they didn't fully understand all of their end-of-life options. For example, they didn't know how to access palliative care, what MAID was and who could access it under what circumstances. They shared personal stories about how MAID may have prevented a community member's prolonged pain and suffering prior to death, had they been aware of the option.

Participants also spoke about intersecting stigmas related to speaking about death, dying and suicide. Stigmas can make it challenging to access information on MAID, which may further contribute to fear and stigma.

"With the suicide rates of people in our communities who have a terminal illness, I would say that there is not enough information reaching our communities to inform them that this is a possibility."

Some participants said that MAID is a "dark secret" for many individuals and communities. Other participants were concerned about the influence of religion on MAID perspectives. For example, one participant said "a barrier I see is that there's a lot of Catholic or faith-based taboos in talking about MAID."

Many participants said that greater public awareness, dialogue and education are needed.

"We need to be able to openly, safely and truthfully discuss these things without facing religious judgment or it being taboo. We need to talk about MAID and have safe and non-judgmental spaces to do that, because currently these topics are taboo."

Resources on end-of-life care options, including MAID, in multiple Indigenous languages can address information gaps and reduce stigma. Resources should be holistic, visually appealing and written clearly. Some participants said such resources should be developed through community engagement and conversations.

"We need culturally appropriate education about MAID, made available throughout numerous platforms, in numerous Indigenous languages and utilizing Indigenous Peoples to provide this information."

"We are tackling a lack of awareness and are missing resources and information to make decisions. What are my options?"

To support informed decision-making and culturally safe care, participants said it's important that information be shared in ways that are accessible, respectful and community-driven.

Information on end-of-life care options is best provided by someone who is trustworthy, knowledgeable and can deliver it in a respectful and culturally appropriate manner. Participants cited community leaders, Elders, Knowledge Carriers and Helpers, and Indigenous care providers. Another suggestion was for Indigenous-specific teams of practitioners and support staff to provide community-based education, knowledge, guidance and support around end-of-life care in Indigenous communities.

We also heard that community health nurses, home care teams, paramedics and other health and social service providers require training and resources on MAID tailored to their needs. For example, frontline staff need tools and guidance to know how to:

- talk about MAID respectfully

- make referrals for MAID, if requested, or

- deal with grief and loss specific to MAID

Theme 5: Meaningful engagement and collaboration

Some participants felt strongly that they should have been engaged sooner on the topic of MAID. They said policy and services on end-of-life care should be driven by and reflect the community perspective. Collaborating with a community can repair the mistrust that many Indigenous Peoples have of the federal government and health systems.

"A good place to start would be to talk to Elders and seniors and what they would recommend going forward."

Participants noted that engagement was needed "with different age groups, so that people aren't afraid to speak due to intergenerational differences in opinion."

More consultation is also needed before the eligibility exclusion for persons with mental illness as a sole medical condition expires in March 2027.

Participants spoke about the importance of continued meaningful engagement by federal, provincial and territorial governments, and health authorities in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples.

In their own words

This section emphasizes the diverse perspectives and views that were shared during the dialogue sessions. It demonstrates that values and priorities vary across and among distinct identities and according to lived experiences. It does not imply that these perspectives are exclusive to these groups or that all Indigenous Peoples share their views.

We have used participants' own words as much as possible.

Elders and Knowledge Keepers

- Ask the Elders what is needed. The voices of Elders and Knowledge Keepers must be incorporated into MAID, including creating a forum of Elders to support these consultations.

- We need to reclaim our death and end-of-life processes.

- When our loved ones die, we should have the right to bring them home.

- I fear losing the ability to decide for myself.

- It is concerning that there is a lot of misinformation about MAID.

- Elders and Elders-in-training should be leaders in educating youth in the community about Indigenous practices of death and dying.

- Health care and funeral home staff should be required to take Indigenous end-of-life training, including the importance of protocol, customs, ceremonies, traditions and after-death care.

- There is uncertainty if deceased Ancestors know to come when someone receives MAID. Ancestors need to greet the dying person as they pass to the other side so they are not left in limbo.

- There needs to be more consultation with Indigenous Peoples, including to have the authority to choose the details of sacred spaces within health care areas and space for families. These details include things such as wall colour, what protocols are in the room and ensuring the ability to see the sky, mountains and birds.

First Nations

- MAID currently comes across as very medical and needs to be decolonized.

- Validate and honour individual choices and autonomy.

- There needs to be cultural safety training for practitioners providing MAID and accountability.

- We don't talk about death, dying or suicide. Shame makes conversations about MAID difficult.

- We need standards of care and tools to support Indigenous Peoples.

- There should be a mental health support team to guide the families through the MAID process, not just a physician. It is especially important to support those who do not agree with the choice. The system should take a holistic approach.

- We need to incorporate our Elders, Traditional Healers, Helpers and Indigenous end-of-life guides and navigators in MAID and end-of-life care processes. They need support and training as well.

- Rural and remote communities do not have access to the same resources.

- A barrier to care is a crisis in misdiagnosis. We aren't using culturally valid assessment tools.

- Not enough funding for cultural supports.

- A lot of healers were survivors first and there is a shortage of them. They need to be supported because the work is taxing, but important.

- There should be more outreach in the future to better educate First Nations and other Indigenous communities on MAID to ensure people know that it is an option.

- Collaborate with Indigenous governments and organizations, Elders and Knowledge Keepers to build trust, share information and resources, and facilitate discussions

- Due to land matters and housing shortages, there should be a process in place that ensures individuals accessing MAID complete a will and that any property is transferred to a family or band member so that there is no additional conflict.

- There should be training available for community health nurses and home care teams who wish to be instructed on culturally safe practices and Land-based healing.

- There are many Indigenous organizations that can work with communities to bridge the mistrust between the government and Indigenous Peoples. Going forward, there should be more incorporation of Indigenous organizations to help facilitate discussions.

Métis

- Connection and interconnectedness to community, to one another, the Land, spiritual well-being and one's spiritual world are important cultural strengths at end of life.

- Our biggest battle as Métis is mental health and poverty. Consider if additional legislative safeguards are necessary. Colonial trauma may push people towards MAID.

- Conversations need to take place with local Métis governments about all options, such as treatment and palliative care.

- We need access to health care services, palliative and primary care in the community and address the lack of Métis health benefits. First Nations and Inuit receive these health benefits, but Métis have been excluded.

- Choice and control are a relief for some people. Some people will choose MAID because they don't want to be a burden.

- I need to know and understand my end-of-life options, not just MAID.

- It would be helpful to have peer support groups for family members and loved ones where they can share experiences and difficulties. It is also important to seek counselling, if needed, to develop a self-care plan because to be supportive for their loved one, they must also take care of themselves.

- Seniors should be surrounded by loved ones at the end of their lives, not removed to facilities.

- Support for all involved in MAID (individuals, families, communities, providers).

- More after-care, peer support, caregiver cafés, Elders trained in MAID, spiritual care, counselling and support for families. Resources and support should be available in multiple languages, formats and for a variety of ages.

- Support Métis death doulas.

- Resources are needed to educate Métis communities on MAID. This should be done by offering education sessions and culturally relevant resources on MAID, such as pamphlets that guide discussions, in collaboration with Métis organizations and communities.

- There should be resources and support for those who are involved with MAID or who have a family member going through MAID. These should be available for a variety of age groups, including children and youth, both on and offline. A lot of Elders and Knowledge Keepers in rural and remote communities do not have access to computers, so information must be provided in alternate ways.

- A website should be developed that showcases culturally sensitive perspectives (like the Métis perspective) that has links to relevant resources related to MAID.

- Information on MAID needs to be presented in languages beyond English and French, such as Michif and Cree.

- Information on MAID should be provided to friendship centres or other community spaces upon request, rather than it being pushed on them. It would be helpful to provide opportunities for Métis people to share information, such as caregiver cafés.

Inuit living outside of Inuit Nunangat

- Culturally appropriate care, as well as access to Elders, country food and services in one's own language are vitally important and should be prioritized. Connection to ceremony and culture provides comfort and support during medical treatment.

- There have been incidents where patients did not understand the extent of their illness due to language barriers. The current gaps in communication should be addressed, specifically when family members are sent away to receive health care, as often they cannot be reached by friends and family back home.

- There is a lot of medical terminology that does not exist in Inuit languages, so interpreters have to figure out how to translate it in a way that makes the most sense. There should be terminology developed to explain MAID in Inuktut.

- Fly-in and fly-out practitioners do not give the same level of care as a longer-term primary care doctor. There is less continuity of care. Patients constantly need new tests and to retell their medical history, often with linguistic barriers.

- We want to be surrounded by loved ones, ceremony and want to be home.

- When someone must leave their community to access health care, there should be more financial supports available for them, their friends and family. Especially in Northern Inuit communities, where a significant amount of people live below the poverty line and are unable to easily travel or cover additional costs such as hotels and restaurants.

- People seem to just get dropped into the health care system (when accessing care in urban centres) and are not always given information on how to access Inuit resources or other services.

- There should be more supports and resources available to Northern communities, as many are grappling with people moving away to larger urban centres due to the lack of housing, resources and services.

- There should be more Inuit working within MAID and offering end-of-life care services. Training programs should be offered to facilitate the utilization of the local Inuit workforce, especially in areas with high unemployment.

- Many Inuit still hold strong objections to MAID and do not wish to discuss it, as they consider it a form of suicide and feel that it clashes with traditional Inuit beliefs and principles. At the same time, many Inuit regard MAID as an empowering option at end of life.

- A barrier to receiving useful and culturally relevant information is that there are colonial impacts that are still heavily felt. There is a lot of resulting pain, fear and distrust.

- Some Elders will not be okay with MAID. It goes against our Inuit values.

Two-Spirit, LGBTQI+ and gender-diverse Indigenous Peoples

- Honour patient pronouns and names. They should be consistently used by the medical team during end-of-life care, including MAID.

- It can be draining to be around relatives who are still coming to terms with the person's 2SLGBTQIA+ identity. This can cause tension, which does not need to be part of a person's end-of-life journey.

- There should be flexibility in who is considered family, as some patients may have "chosen family" or want close friends by their side, rather than blood relatives.

- It is important to have Indigenous navigators available for patients and their loved ones. Talking circles are also important for end-of-life care and MAID because it helps to lighten the burden for people as they prepare for death.

- MAID must not be abused in the context of mental illness and addiction. People need to be properly educated on it.

- MAID should be an option at all hospitals regardless of religious affiliation.

- I need to know that MAID is not another form of genocide.

Indigenous Peoples with disabilities

- The decision about whether to seek MAID or not can be political. Some believe that "existence is resistance" and that it is important to stay alive.

- To even explore MAID as an option takes courage and bravery.

- Bias from providers can make Indigenous People not want to access health services. This could lead them to consider MAID (for instance, so they do not have to continue going to the hospital). Health care should be led by Indigenous communities where people are more comfortable.

- It is important to know that cultural protocols will be respected. There needs to be an Indigenous person at the hospital who is empowered to enact appropriate cultural protocols.

- There should be Indigenous representation on the assessing committee.

- Have an Indigenous support person there while assessing eligibility for MAID.

- There is uncertainty about the efficacy of current safeguards. It is felt that MAID could be too easily accessible for mental health reasons.

- Community support should not just be based on the disability but should also include support for family or friends to ensure they can always provide care and love for those with disabilities.

Indigenous health professionals and academics

- There is a power imbalance between Indigenous Peoples and health care providers. A great amount of humility is required.

- Implement a Two-Eyed Seeing approach, bringing culture and worldview together with Western palliative care.

- Seek guidance from Elders and Knowledge Keepers on how to talk about MAID.

- All the information is needed to make an informed decision about MAID. This includes the difference between palliative care, pain management and MAID in a relatable and culturally sensitive way.

- MAID may be difficult for our Elders to accept.

- There needs to be someone in the larger palliative support network who understands cultural context and it cannot be an unpaid position.

- The financial burden needs to stop being on the community to do all the work and the system needs to be built from the ground up using this approach.

- There should be social media awareness campaigns funded by the government, in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples and communities.

- It must be a priority to support Indigenous People at end of life. If a person's end-of-life care plan includes MAID, appropriate supports should be provided before, during and to their loved ones after receiving MAID.

- The government should fund some cultural sensitivity training sessions for MAID providers.

Conclusion and next steps

End-of-life care, including MAID, is a highly complex issue.

Over the course of this engagement process, Health Canada met with and listened to many First Nations people, Inuit and Métis. They generously shared words of advice, perspectives, knowledge, pain and sorrow, and hopes for how we can take action together to improve end-of-life experiences for Indigenous Peoples.

We are profoundly grateful to everyone who took the time to join in these discussions.

Health Canada respects the self-determination of First Nations people, Inuit and Métis. We are committed to working in partnership to address challenges and improve access to culturally appropriate end-of-life care services, including MAID. Ongoing engagement ensures these services are shaped by Indigenous voices and delivered in ways that honour and reflect Indigenous cultures, values and ways of knowing. This work is part of a broader effort toward systemic change to ensure care is equitable, respectful and responsive to the diverse needs of Indigenous Peoples.

Provincial and territorial governments are responsible for the management and delivery of health care services, including end-of-life services such as MAID. Indigenous Services Canada also funds the delivery of health care services for First Nations and Inuit, including palliative care. The federal government will continue to work with provincial and territorial governments to support greater partnership with Indigenous Peoples to reduce inequities in accessing health and social services.

As a start, we hope that this report will help to inform the work of many partners and stakeholders who play a role in end-of-life care, including MAID and palliative care. These partners and stakeholders include:

- health authorities

- health care providers

- MAID assessors and providers

- provincial and territorial governments

- Indigenous organizations and governments

- federal departments such as Indigenous Services Canada, Justice Canada and Corrections Canada

Annex

Engagement approach

Indigenous-led engagement and knowledge exchange

Since 2022, Health Canada and Indigenous Services Canada have provided funding to 14 Indigenous organizations and governments to support their priorities on palliative and end-of-life care, and MAID.

These organizations are:

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

- Dilico Anishinabek Family Centre

- First Nations Health Authority of British Columbia

- Les Femmes Michif Otipemisiwak

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Mawi Ta'mk Society

- Métis Nation of British Columbia

- Métis National Council

- National Association of Friendship Centres

- Native Women's Association of Canada

- Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services

- Peguis First Nation

- Six Nations of the Grand River

Organizations chose to lead community engagement or build organizational and community capacity based on their priorities, or both. Many organizations took a holistic approach, engaging on both palliative care and MAID.

To date, the following organizations have completed reports:

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

- Les Femmes Michif Otipemisiwak

- Native Women's Association of Canada

- Métis National Council (internal report)

- Six Nations of the Grand River (internal report)

The following organizations are wrapping up engagement sessions and are expected to produce reports in 2025-26:

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Métis Nation of British Columbia

- National Association of Friendship Centres

- Mawi Ta'mk Society in collaboration with the Wabanaki Council on Disability

Organizations such as the Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services have recently begun to hold engagement sessions. Other organizations are developing end-of-life care training, education and resources for frontline workers and community members. These include Peguis First Nation, the Dilico Anishinabek Family Centre and the First Nations Health Authority of British Columbia.

Health Canada and Indigenous Services Canada funded a national Indigenous knowledge exchange on palliative and end-of-life care, including MAID, on February 6-8, 2024. The event was called Advancing Indigenous Policy and Practice: Supporting The Journey Home When Seriously Ill. It was organized by the SE Health First Nations, Inuit and Métis Program and Lakehead University's Centre for Education and Research on Aging and Health. Over 350 people attended, including Elders and Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous health professionals, policy leaders, community members and government officials.

Learn more:

- Advancing Indigenous Policy & Practice: Supporting the Journey Home when Seriously Ill - Companion Courses & Resources (event videos)

- Advancing Indigenous Policy & Practice: Supporting the Journey Home when Seriously Ill - Companion Courses & Resources (PDF)

Health Canada-led engagement

Health Canada hosted dialogue sessions and an online questionnaire to support inclusive and culturally safe conversations. A broad range of First Nations, Inuit outside of Inuit Nunangat, and Métis took part, including Indigenous:

- women

- 2SLGBTQIA+ individuals

- individuals living with disabilities

- individuals living in urban areas, off-reserve or away from their home communities

Participants were informed of the purpose of the engagement and that:

- their views would help Health Canada influence MAID policy and develop a "what we heard" report

- Indigenous organizations and governments would be interpreting and reviewing the report

We also shared information on:

- MAID

- mental health support and resources

- the protection of personal rights and information in accordance with federal privacy policy and legislation

Learn more:

- Privacy Act

- Directive on Privacy Practices

- Personal information collected during outreach activities

We compared key themes and messages identified through the dialogue sessions and the online questionnaire. They are reflected in this report.

To honour community and Indigenous voices, we asked Indigenous partners to review, provide feedback and validate the key findings.

Online questionnaire

Health Canada developed an online questionnaire in collaboration with Indigenous organizations and Indigenous Services Canada. The questionnaire was designed to ask Indigenous people to share their knowledge and experience about end-of-life care, including MAID.

The questionnaire was available online from August 17, 2023, to June 30, 2024.

We also distributed the survey:

- by email to subscribers of federal government updates and to online networks of Indigenous organizations, Indigenous Services Canada, and provincial and territorial governments

- in invitations sent to individuals and organizations to encourage participation in the national dialogues

The questionnaire was qualitative and included several open-ended questions. Participants were invited to share their perspectives on end of life, cultural safety, trauma-informed care and MAID.

A total of 252 individuals completed the questionnaire. Of these, we:

- excluded 50 who identified as "not Indigenous"

- included the remaining 202 who identified as Indigenous

For the analysis, we:

- used a Two-Eyed Seeing approach to build on the strengths of Indigenous and Western ways of knowing

- applied a strength- and desire-based approach to honour the strengths, hopes, priorities and vision of communities

We used thematic analysis to review participant responses line by line. This approach helped us identify key recurring themes that arose from participants' shared stories, knowledge and experiences.

We compared these findings from the thematic analysis with an artificial intelligence (AI) data analysis process, using Copilot, NVivo, Power BI and ChatGPT software on an internal federal government server.

National dialogue sessions

We held 23 national dialogue sessions from February to May 2024:

- 7 virtual sessions

- 14 hybrid (in-person and virtual) sessions

- 2 virtual validation sessions

The hybrid sessions took place in communities across Canada, either close to First Nations communities or in urban areas with large Inuit populations and Métis settlement areas.

More than 470 participants from 94 different Indigenous Nations, governments and organizations attended the sessions.

Learn more about the session locations, types of participants and focus audiences.

It was important to create a culturally safe space for the national dialogue sessions.

Sixteen First Nations, Métis and Inuit Elders, Knowledge Carriers and Sharers from across Canada provided support. Many of these individuals had specific knowledge on end-of-life care and a range of life experiences.

Indigenous trauma counsellors offered one-on-one counselling during each session (in a separate private virtual or physical room). Participants were also able to reach a counsellor following each session.

Indigenous Elders, counsellors and facilitators guided the sessions, where the focus was on maintaining emotional safety and promoting self-care due to the difficult subject matter. Mental health resources were also shared before, during and after each session.

Participants who did not wish to participate in a session were given the opportunity to provide their feedback in other ways (such as through the online survey).

All sessions were graphically recorded by ThinkLink Graphics, who listened, interpreted and illustrated the content in real time. Graphic recordings are live visual summaries that capture key ideas from discussions or presentations through text and imagery. The graphic recordings were shared with participants during and following the dialogues for further input.

Sessions were offered in English and French and in Indigenous languages by request. Participants were asked ahead of time to indicate if they needed any accessibility accommodations. We offered Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART), American Sign Language (ASL) and la langue des signes québécoise (LSQ).

Food stipends, honorariums and reimbursements for travel and other expenses were offered to encourage participation and reduce barriers. Participants could leave a session at any time without impacting these reimbursements.

Mahihkan Management Solutions was hired to summarize participants' knowledge and perspectives into themes. The Indigenous-owned firm also organized and facilitated the sessions, developed summaries, validated the findings and wrote a detailed report.

Those who attended a dialogue session were invited to take part in either one or both virtual validation sessions. At these sessions, participants were asked to provide feedback on the proposed key themes.

Session details and participant demographics

Details on engagement dates, locations and focus audiences are provided in Table 1.

| Date in 2024 | Focus audienceFootnote a | LocationFootnote b |

|---|---|---|

| February 29 | First Nations | Virtual only |

| March 4 | First Nations | Halifax, NS |

| March 4 | Indigenous Peoples | Halifax, NS |

| March 11 | Indigenous Peoples | Whitehorse, YT |

| March 12 | Indigenous Peoples (special session as part of the Yukon First Nations Health and Wellness Summit)Footnote c | Whitehorse, YT |

| March 14 | Elders and Knowledge Keepers | Merritt, BC |

| March 14 | First Nations | Merritt, BC |

| March 19 | 2SLGBTQIA+ people | Virtual only |

| March 25 | MétisFootnote d | Edmonton, AB |

| March 25 | Urban InuitFootnote e | Edmonton, AB |

| March 25 | First Nations | Edmonton, AB |

| March 27 | MétisFootnote d | Prince Albert, SK |

| March 27 | Indigenous Peoples | Prince Albert, SK |

| April 3 | Inuit (national dialogue) | Virtual only |

| April 4 | Persons with disabilities | Virtual only |

| April 9 | First Nations | Wendake, QC |

| April 11 | First Nations | Ottawa, ON |

| April 11 | Urban InuitFootnote e | Ottawa, ON |

| April 16 | MétisFootnote d | Virtual only |

| April 17 | Health professionals, academics, legal and ethical professionals | Virtual only |

| May 23 | Validation session with Indigenous Peoples | Virtual only |

| May 28 | Validation session with Indigenous Peoples | Virtual only |

|

||

Table 2 gives the number of participants by Indigenous identity.

| Indigenous identity | Count |

|---|---|

| First Nations | 324 |

| Métis | 185 |

| Inuit | 78 |

| Other | 34 |

| Did not disclose | 52 |