Summary Report: Consultations on the renewal of the Official Languages Health Program 2023 - 2028

On this page

Context

In January 2022, Health Canada launched a consultation with official language minority communities (OLMCs - Francophones outside Quebec and Anglophones in Quebec) to learn about their personal experiences in accessing health services in the official language (OL) of their choice and to find out about their interests for the 2023-2028 phase of the Official Languages Health Program (OLHP). The information collected was analyzed and is summarized in this report.

The OLHP, launched in 2003, aims to improve access to health services for OLMCs and is part of the Government of Canada Action Plan for Official Languages 2018-2023 - Investing in our future. The Program currently includes the following three mutually reinforcing components:

1 - Training and retention of health professionals

Health Canada provides support to post-secondary training institutions in order to improve the availability of bilingual health service providers across the country and more particularly in regions where the needs of OLMCs are greatest.

-

The Consortium national de formation en santé (CNFS), which includes a national secretariat and 16 post-secondary member-institutions outside Quebec, offers over 100 French-language health programs in eight provinces and works with health facilities to offer internships and placements for its students.

- McGill University offers language training to health providers currently employed in Quebec's health care system, as well as bursaries and internships for integrating bilingual health professionals in regions where there is significant need for English-language health services.

2 - Health Networking

Health networks work with various partners (communities, decision-makers, health managers, health professionals, and post-secondary institutions) to develop concrete solutions to improve access to health services for OLMCs. Targeted recipients for this component are:

- The Société Santé en français (SSF), with its 16 networks across all provinces and territories (except Quebec) for French-speaking minority communities.

- The Community Health and Social Services Network (CHSSN), with its 23 networks across Quebec for English-speaking minority communities.

3 - Health services access projects

Projects under the current funding phase use innovative approaches to improve access to health services for OLMCs.

-

SSF and CHSSN support projects under the following components: integration of health human resources; knowledge development and dissemination (including activities and tools for data collection, needs assessments and research); and improving community health (through increased access to health services).

-

Health Canada launched a call for proposals in winter 2019 to support stakeholders, such as not-for-profit organisations and provinces and territories in the areas of home and community care, mental health and addictions services, palliative care and end-of-life care.

-

As a pilot project during the current funding phase, micro-grants of up to $1000 each were offered to small not-for-profit organisations and individuals to increase access to health services for OLMCs.

The Program is aligned with Health Canada's mandate to help Canadians maintain and improve their health. It also contributes to the Department's obligation to ensure that positive steps are taken to strengthen the vitality of English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada and to support and assist their development, in accordance with the Government of Canada’s commitment under Part VII of the Official Languages Act.

Demographic data

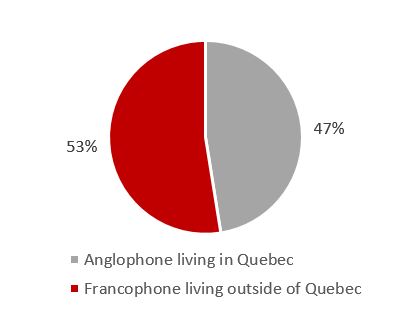

A total of 2001 people from across all Canadian provinces and territories participated in the online consultation. Just over half (53%) of respondents were Francophones in a minority situation, compared to 47% who were Anglophones in a minority situation. See Table 1.1.

| Identity of the official language minority community (OLMC) | OLMC Identity | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Anglophone living in Quebec | 950 | 47% |

| Francophone living outside Quebec | 1051 | 53% |

| Total | 2001 | 100% |

Figure 1 - Text description

The graph shows a proportion of 53% of French-speaking respondents living outside Quebec and 47% of English speaking respondents living in Quebec.

The demographic data also shows that English-speaking respondents were generally older than French-speaking respondents, which could have had an impact on the perception of the respondents on the health services offered or the categories of service that the respondents considered to be priorities.

| OLMC Identity | Age Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-34 | 35-54 | 55+ | Total | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Anglophone living in Quebec | 116 | 31% | 386 | 42% | 445 | 64% | 950 | 47% |

| Francophone living outside Quebec | 256 | 69% | 539 | 58% | 250 | 36% | 1051 | 53% |

| Total | 372 | 100% | 925 | 100% | 695 | 100% | 2001 | 100% |

| Note: The total column includes respondents who did not select an age group or who selected “I prefer not to answer”. | ||||||||

It is also interesting to note that three quarters of the respondents (1496 out of 2001) were women and that the number of French-speaking men compared to the number of English-speaking men was almost identical, while the number of French-speaking women was slightly higher than the number of English-speaking women.

| OLMC Identity | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Anglophone living in Quebec | 236 | 50% | 703 | 47% | 950 | 47% |

| Francophone living outside Quebec | 238 | 50% | 793 | 53% | 1051 | 53% |

| Total | 474 | 100% | 1496 | 100% | 2001 | 100% |

| Note: The total column includes respondents who did not select a gender identity or who answered 'various gender identities' or 'other'. | ||||||

Regarding the province or territory of residence of French-speaking respondents, 38% came from the western provinces (mainly Alberta) and the territories, 31% came from Ontario and 30% came from the Atlantic provinces (especially New Brunswick and Nova Scotia).

The proportion of immigrant respondents was higher among Francophones (26%) than among Anglophones (16%), while 2% of respondents (both Francophones and Anglophones) reported an Aboriginal identity.

About half of respondents reported an affiliation with institutions that serve or could serve OLMCs, including 269 belonging to a post-secondary institution (students or staff), 142 working for health institutions, 155 working for provincial or territorial governments and 108 working for organizations serving OLMCs.

Consultation Questions

- Respondents were asked if they had any challenges accessing health services in the official language of their choice. The vast majority of respondents, Anglophones and Francophones alike, answered yes to this question.

- Respondents were asked which categories of service were most difficult to access in the official language of their choice and were asked to explain the challenges they encountered.

- Respondents were asked if they had noticed any progress in access to health services in the minority official language over the past few years and to explain their answer.

- Respondents were asked to identify their priorities for access to health services in the official language of choice by 2028.

- Respondents were asked if they believed that a health card that identifies the patient's official language of preference could have a significant impact on the provision of health services in that language.

- Respondents were asked if they knew of any bilingual health professionals in their area and how they were able to find them.

- Respondents were asked if they had any suggestions on possible measures to put patients from OLMCs in contact with bilingual health professionals and who should be responsible.

- Participants were asked whether they believed that telehealth could be an effective (or not) means of serving OLMCs in their language and which services would lend themselves best to this.

- Participants were asked if they had other ideas that could increase access to services in patients' official language of choice.

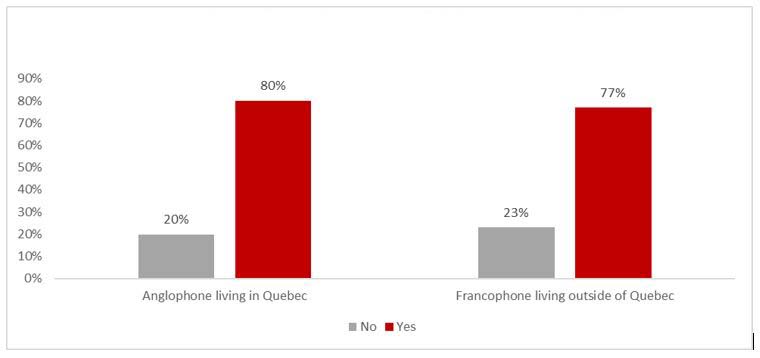

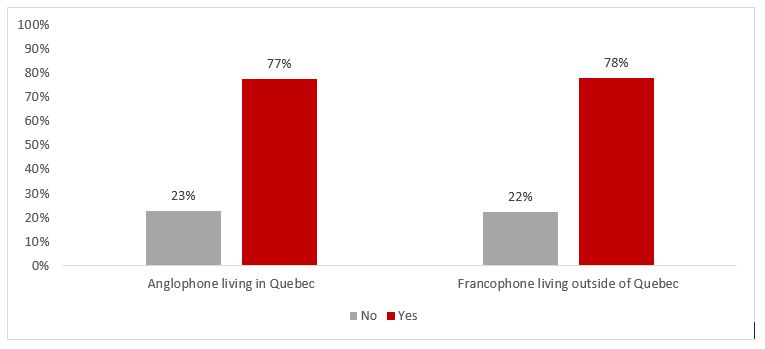

Question 1: Respondents were asked if they had any challenges accessing health services in the official language of their choice. The vast majority of respondents, Anglophones and Francophones alike, answered yes to this question.

Figure Q1 - Text description

The graph shows that 80% of Anglophones in Quebec and 77% of Francophones outside Quebec said they had difficulty accessing health services in the official language of their choice.

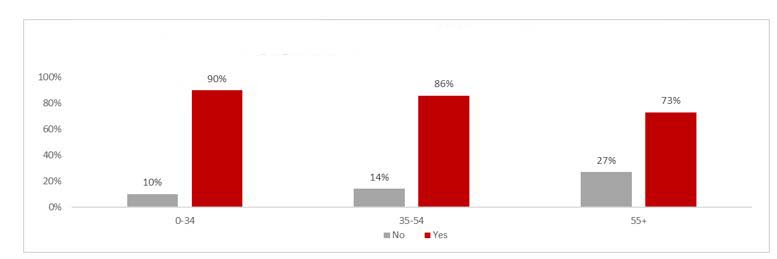

However, it is interesting to note that 90% of Anglophones aged 0 to 34 reported challenges accessing health services in their OL of choice while, among Francophones living in a minority situation, this age group reported the fewest challenges.

Figure Q1-02 - Text description

The graph shows that among English-speaking respondents in Quebec, 90% of those aged 0-34, 86% of those aged 35-54 and 73% of those aged 55 and over said they had difficulty accessing health services in the language official of their choice.

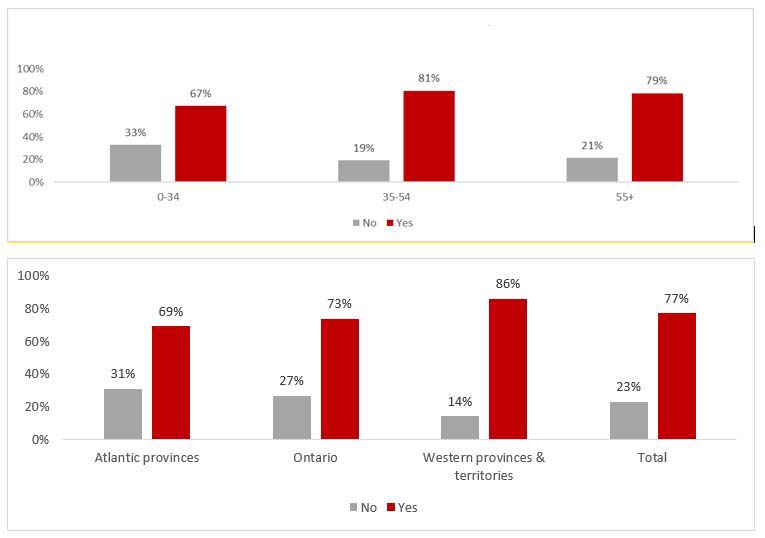

Figure Q1-03 - Text description

First graph shows that among French-speaking respondents outside Quebec, 67% of those aged 0-34, 81% of those aged 35-54 and 79% of those aged 55 and over said they had difficulty accessing health services in the official language of their choice.

Second graph shows regional differences in access to health services in French. The proportion of respondents who said they had difficulty obtaining services in French was 69% in the Atlantic provinces, 73% in Ontario and 86% in the western provinces and the territories.

Among Francophones, accessing health services in the OL of their choice was most challenging in the western provinces and territories (86% reported a challenge in this regard), compared to 73% in Ontario (where the only bilingual hospital west of Quebec exists) and 69% in the Atlantic (where one province, New Brunswick, is officially bilingual).

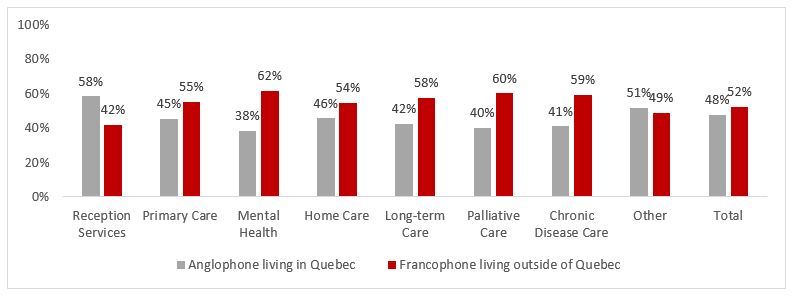

Question 2: Respondents were asked which categories of service were most difficult to access in the official language of their choice and were asked to explain the challenges they encountered.

All service categories were difficult to access, but Francophones identified mental health (62%), palliative care (60%), chronic care (59%) and long-term care (58%) as particular challenges, while reception services (58%) were chosen by a majority of Anglophones.

Figure Q2 - Text description

The graph shows that French-speaking respondents outside Quebec reported having more difficulty than English-speaking respondents in Quebec in being served in the official language of their choice in mental health, palliative care, chronic disease care, long-term care, primary care and home care, while English-speaking respondents from Quebec reported having more difficulty accessing reception services in English.

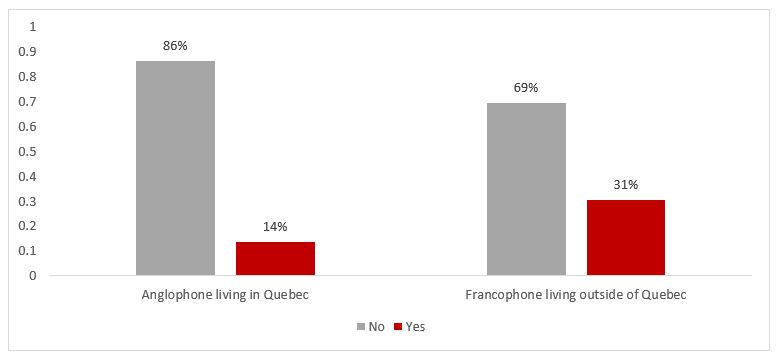

Question 3: Respondents were asked if they had noticed any progress in access to health services in the minority official language over the past few years and to explain their answer.

The majority of respondents said they had seen no significant progress. However, this proportion is much higher among Anglophones. Many commented negatively on Bill 96 proposed by the Government of Quebec to protect the French language. This element, which was highly criticized in the Anglophone media, may have had a negative effect on the perception of Anglophone respondents when they responded to the consultation. Nearly a third of French-speaking respondents, for their part, noticed an improvement.

When accessing health services in a rather English-speaking hospital, I was asked if I would prefer to have someone French present during a medical procedure. This is definitely an improvement! [Translation]

Figure Q3 - Text description

The graph shows that 86% of English-speaking respondents in Quebec and 69% of French-speaking respondents outside Quebec had not seen any progress in accessing health services in the official language of their choice.

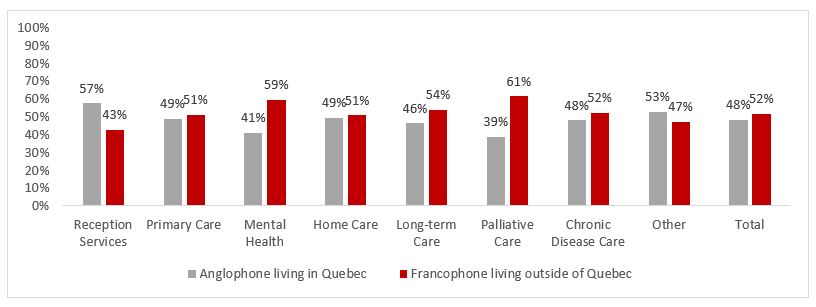

Question 4: Respondents were asked to identify their priorities for access to health services in the official language of choice by 2028.

Respondents' answers aligned fairly well with the categories of services that represented the greatest challenges, as identified in question 2. Again, Anglophones favored reception services, while palliative care and mental health were at the top of the list among Francophones.

Figure Q4 - Text description

The graph shows priority health service categories for French-speaking respondents outside Quebec and English-speaking respondents in Quebec. Palliative care (61%) and mental health (59%) were the highest priority categories for French-speaking respondents outside of Quebec, while reception services (57%) were the highest priority for English-speaking respondents in Quebec.

Some testimonials in this regard:

- Reception: They are the first point of contact and give important information about what a person needs to bring with them to the appointment and are the one who can help access the doctor when needed

- Mental health is one of the areas of health where interpretation is not an adequate solution. Expressing emotions and experiences cannot be done easily with an interpreter. Moreover, it is a very personal field and it is difficult to accept a third party in the professional-patient relationship. [Translation]

Even when it was not a matter of mental health per se, we can perceive, from the answers of several respondents, the importance of the psychological aspect, and that the offer (or absence) of services in the minority official language can have:

- To be able to initiate in English, through "Reception Services" contact with a health professional or establishment, would alleviate stress, anxiety and the risk of mis-information

- I have cancer with metastases and I live with a lot of heartbreaking anxiety. I am vulnerable and worried about my state of health as I will have to receive chemotherapy treatments every 28 days for the rest of my life. As I am getting to the reception with my vulnerability, I would like to be treated as a person, with respect and dignity, which could give me hope to live the necessary care until the last day of my existence. [Translation]

- When you have health issues, you are already anxious about what is going on within you. You need a friendly voice and a calm professional to ease your anxiety. You don't need to feel like you have to fight the system that should be caring for you. Trust is so important to a person who is not feeling well.

- I worry when I get sick and need long term care that I will not want to stay here where my children live. I will have to move back to an English speaking province so I can feel more comfortable in my native tongue.

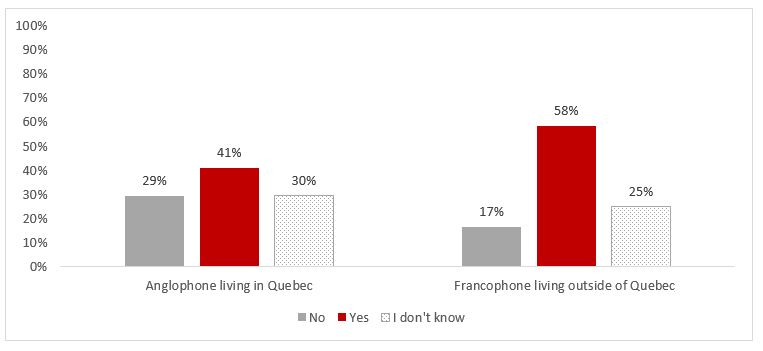

Question 5: Respondents were asked if they believed that a health card that identifies the patient's official language of preference could have a significant impact on the provision of health services in that language.

This concept, implemented in Prince Edward Island, seemed better known and generated much more enthusiasm among French-speaking respondents (58% support) than English-speaking respondents (41% support).

Figure Q5 - Text description

The graph shows that 41% of English-speaking respondents in Quebec supported the idea of a health card that identifies the patient's official language, while 29% and 30% did not support or were undecided about this proposal. Among Francophone respondents outside Quebec, 58% supported this initiative, compared to 17% who did not support it and 25% who were undecided.

Several respondents, especially Francophones, highlighted the positive aspects of a card that would capture the patient's preferred official language, including better planning of services based on data collected on patients' preferred language and the active offer of services in the minority official language:

- A provincial health card that identifies the language would allow better data collection on the health status of Francophones. Organizations and boards can then plan the distribution of French-speaking human resources to the departments and areas most in demand. In addition, the identification of Francophones would improve the active offer of health services in French and act as a reminder to health workers to provide service in French or an interpretation service. [Translation]

- The variable is imperative for service planning because there are always providers who do not think they have French-speaking clients. [Translation]

- A great idea if it could be included in a medical record. The patient already weakened by his health issue should not waste energy asking to receive service in his mother tongue. It should be automatically offered given the mention in the medical file. [Translation]

Another positive aspect would be to reduce ambiguity when the person's name does not correspond to the patient's preferred language:

- My maiden name is French, but I do not speak enough French

- Working in Healthcare myself in Montreal, I usually speak both French and English to my clients when first meeting them. I've had a few surprises, some people names look French or English, e.g.: John Smith and then the patient will tell me he doesn't speak English. I would naturally switch to French. But just starting out, if I knew at first their language preference I would offer it immediately.

However, not all respondents were convinced that a health card that captures the language preference of the patient would be a positive thing. Some respondents, especially Anglophones, highlighted their fear of discrimination. Moreover, contrary to the Francophone respondents who would like services in French to correspond to the demographic weight of Francophone communities in the regions, the opposite was raised among the Anglophones, where there is fear of a drop in service if these were based on more accurate demographic data:

- It creates an us and them situation. Not good at all.

- This seems like a way to quantify the minority so that services can only be doled out in proportion to the % of minorities per region. Staff should be bilingual just like they are expected to be in many many other industries.

Some Francophone respondents, generally in favour of the measure, worried that Francophones would not identify as such and that services would be reduced accordingly:

- Care should be taken, however, not to force people to choose. Many people I know are fully bilingual and would be hesitant to indicate French as their language of preference if they know that access to service would be easier if they choose "Bilingual or English/French" as their preference. [Translation]

- Linguistic insecurity in my region will mean that many people will not identify as Francophones and this will allow service providers to reduce their efforts even further. [Translation]

Question 6: Respondents were asked if they knew of any bilingual health professionals in their area and how they were able to find them.

Although the majority of respondents indicated having problems accessing health services in their official language, a large majority of them nevertheless indicated that they knew at least one bilingual health professional in their region. The results were very similar between Francophones and Anglophones:

Figure Q6-01 - Text description

The graph shows that 77% of English-speaking respondents in Quebec know at least one bilingual health professional in their region.

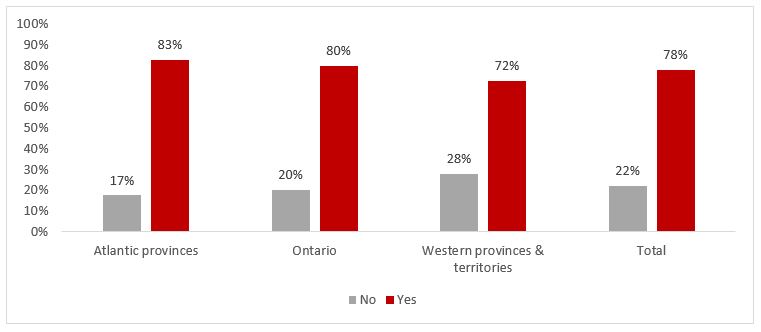

However, a certain disparity can be observed between the regions of the country. In fact, the proportion of respondents from the western provinces and territories were less likely to know bilingual health professionals in their region (72% compared to 80% in Ontario and 83% in the Atlantic).

Figure Q6-02 - Text description

The graph shows that 78% of French-speaking respondents outside Quebec knew at least one bilingual health professional and that this proportion is 83% in the Atlantic provinces, 80% in Ontario and 72% in the western provinces and the territories.

Participants' comments allow us to further nuance these findings. Indeed, several English-speaking respondents living in Montreal stated that it was very easy for them to find services in their language, while respondents from other regions of Quebec said that they had to travel to Montreal to obtain services in their official language, when they lived nearby (e.g. Montérégie). In other regions in Quebec, many services in English were not available at all. The same type of situation was described by respondents from New Brunswick, where it would be quite easy to find services in French in Moncton and in the more French-speaking regions of the province, but more difficult to find bilingual professionals in the more English-speaking regions.

In terms of finding these bilingual professionals, it seems that the networks of the Société Santé en français and the Community Health and Social Services Network are very useful to OLMCs, in particular by offering directories of bilingual health professionals on their websites. Referrals from family physicians and word of mouth also play an important role for many respondents.

Question 7: Respondents were asked if they had any suggestions on possible measures to put patients from OLMCs in contact with bilingual health professionals and who should be responsible.

Many suggestions were made, which can be grouped into five broad categories:

Identification of supply and demand for health services in the minority official language

A very large number of respondents suggested creating and continuously updating databases/directories of bilingual health professionals that should be accessible online. Although several similar resources already exist, these are often the creation of small community organizations such as the networks of the Société Santé en français and the Community Health and Social Services Network. Several respondents instead said they would like these directories to be the responsibility of provincial, territorial or regional health authorities. Many also highlighted the potential role of health institutions and professional orders in keeping these databases and directories up to date. In addition to making this data public on a website, it was also suggested to use geolocation to allow patients to find health professionals locally. However, some respondents stressed that it was important to ensure that the professionals identified have a real and functional mastery of the minority official language and that they are truly willing to serve OLMCs in their language. Inside health establishments, it was also suggested that the bilingual status of professionals be highlighted using posters and buttons/badges.

Many respondents, mostly Francophones, also wanted the language preference of patients to be documented by the province or territory and added to a database in order to better plan services in the minority official language and to actively offer them in health institutions.

Training and retention of bilingual health professionalsSeveral respondents pointed out that to put patients from OLMCs in contact with bilingual health professionals, it was first necessary to ensure that there are bilingual health professionals available. This is why the theme of training came up regularly.

Several respondents, especially Francophones, said they would like the provinces and territories to train more new bilingual health professionals to serve OLMCs. Some also deplored that Francophone immigrants are unable to practice in OLMCs because of foreign credential recognition issues.

Learning and knowledge of the minority official language was also the subject of several comments. Several Francophone respondents insisted that proficiency in the minority official language should be recognized as a skill by professional orders and should be compensated accordingly. Among English-speaking respondents, a large number rather said that they would like all health professionals in Quebec to be bilingual. According to them, bilingualism should be an essential condition for obtaining a health diploma as well as for hiring in any health establishment in Quebec.

Active offer of services in the minority official language

The active offer of health services in the minority official language was noted by several respondents as a way to ensure that patients can be automatically put in contact with bilingual health professionals. Among Anglophones, the concept of active offer is not expressed in quite the same way, but respondents nevertheless said that they would like reception services to be available in English and then ensure triage so that subsequent follow-ups with the patient are done in English.

Telemedecine

Telemedicine was also mentioned. Respondents highlighted the positive effects of telemedicine, particularly in remote areas. Some said they wanted a national strategy (federal-provincial-territorial) to offer virtual care across the country. In this way, health professionals from a given province could serve OLMCs from another province, for example.

Community health centers

Finally, some Francophone respondents said they would like to see the establishment of community health centers or bilingual health clinics, whose primary mission would be to provide health services in French for Francophone minority communities. Respondents, however, did not note who would be in charge of these centers or clinics and where their funding would come from.

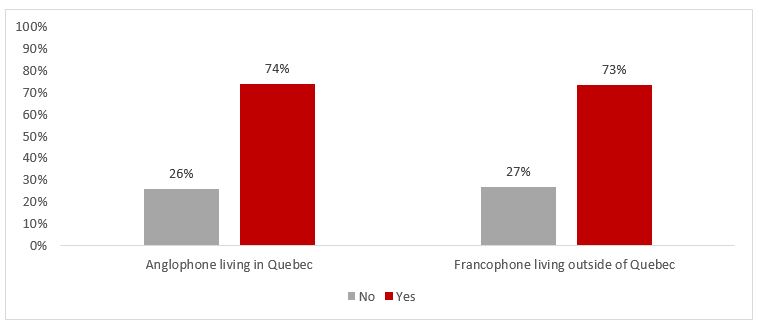

Question 8: Participants were asked whether they believed that telehealth could be an effective (or not) means of serving OLMCs in their language and which services would lend themselves best to this.

About three-quarters of respondents, whether Francophone or Anglophone, were in favor of telehealth services as a means of improving access to health services in the minority official language.

Figure Q8 - Text description

The graph shows that 74% of English-speaking respondents in Quebec and 73% of French-speaking respondents outside Quebec were in favor of telehealth to improve access to health services in the minority official language.

This proportion was the same for all age groups, genders and regions of residence. According to several respondents, telehealth would even be a considerable advantage for rural and remote communities:

- We have to travel five hours to Rimouski just for the doctor to tell us what is happening with our health. This would help community members a lot. Just the fact of not having to travel out of region for sometimes a five-minute result.

Some also suggested that it would be interesting to be able to access health professionals from other provinces to expand the pool of bilingual health professionals who can serve OLMCs.

However, several respondents nuanced their support for telehealth by stating that these services should not become the norm and replace all in-person services:- This service can certainly help, but it must not become the only service to serve OLMCs. [Translation]

- Yes, but with limitations, some services are not meant to be offered over the phone. Nor should we create a second-class system for minorities. [Translation]

Other potential challenges were also raised, such as access to technology and the cultural sensitivity of a professional from another region:

- It takes someone who understands the talk from here. Seniors in many of our communities don't have back pain, they have spine pain, for example. [Translation]

In terms of service categories that would lend themselves best to telehealth, many mentioned mental health, medical test results, routine follow-ups for chronic illnesses, prescription renewals and primary health services that do not require an in-person examination.

Question 9: Participants were asked if they had other ideas that could increase access to services in patients' official language of choice.

Many respondents reiterated suggestions discussed in previous questions:

- directories of bilingual health professionals;

- training of more bilingual health professionals;

- training/awareness of active offer in the minority official language;

- health card that captures the patient's preferred official language; and

- telehealth.

However, some original suggestions surfaced:

- Recognition of the credentials of foreign-trained bilingual health professionals. Although this is a complex file involving several players in the health system, there could be positive potential for OLMCs;

- The use of mobile primary health care teams, which could travel to small centers to provide in-person services. This solution could be studied, but its limits should be clearly defined from the start so as not to create too high expectations on the part of communities; and

- The use of new technologies to enable instantaneous translation between healthcare professionals and patients. This solution, however, could be controversial, given the limitations of already known translation and interpretation services.

It should be noted that some suggestions went beyond the mandate of the OLHP such as the creation of bilingualism bonuses. It should also be noted that the initiatives put forward by Health Canada within the framework of the OLHP must respect the areas of jurisdiction of the provinces and territories as well as the legislative powers of the federal government.

Other suggestions went beyond the constitutional jurisdiction of the federal government, such as the unilateral imposition of official language clauses in agreements between the federal government and the provinces and territories or, as desired by certain Anglophones in a minority situation, the abolition of laws aimed at protecting French in Quebec. That being said, as part of the negotiation of agreements between the two levels of government, considerations for OLMCs could be included upon agreement of the parties involved in respect with the distribution of legislative powers.

Conclusion and Next Steps

The online consultation with OLMCs on the renewal of the OLHP made it possible to collect the testimony of 2001 people, which is a remarkable increase compared to the last online consultation held in 2016, which reached approximately 150 people. The proportion of Francophone (53%) and Anglophone (47%) respondents also made it possible to identify more balanced and nuanced findings for each of the linguistic communities. Anglophone respondents were, however, on average, older than Francophone respondents, while women were overrepresented for both language groups, at around 75%. This last finding is not surprising given that women often have a more prominent role in maintaining family health and/or the fact that a certain proportion of the respondents worked in the health sector in which women are historically overrepresented.

A large majority of respondents (80% Francophone and 77% Anglophone) agreed that they had challenges accessing health services. Although this reality is the same for all services, the priorities were slightly different for the two linguistic groups. While mental health and palliative care were, among other things, favored by Francophones, reception services were the most important for Anglophones, in order to better direct services afterwards. Most respondents, however, said they knew at least one health professional capable of serving them in their language, but this proportion was lower in Western Canada.

The concept of a health card that captures the language preference of the patient did not meet with consensus between Francophones and Anglophones in a minority situation either. Many Francophones were enthusiastic about the idea, in order to collect data for planning services and encourage more active offer of services in French, while many Anglophones were rather worried that such a card could generate more discrimination against them and that they lose services.

Telehealth was a popular concept for both language groups, with support from approximately 75% of respondents. Several, however, pointed out that this way of doing things should not become the norm for serving OLMCs and that human contact was still very important in many cases.

In terms of suggestions for improving access to health care professionals and services in the minority official language, five main categories emerged:

- Identification of supply (bilingual health professionals available) and demand (patients from OLMCs), through databases updated by the provinces (and certain other partners) in order to find a balance in the planning of services and simplify the search for available resources for patients;

- The training and retention of bilingual health professionals, through post-secondary training in the minority official language and through language training;

- Encourage the active offer of health services in the minority official language;

- The offer of telemedicine services, including between provinces and territories; and

- The creation and maintenance of community health centers capable of offering health services in the minority official language.

This consultation report will be part of a set of documents (including a consultation report with stakeholders, the evaluation report of the Action Plan for Official Languages, a public opinion research report, various research papers, etc.) that will be used to inform Health Canada's thoughts on the future of the OLHP and more specifically the Program's priorities for its next phase in 2023-2028.