Framework on Palliative Care in Canada

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 2.9 MB, 62 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: 2018-12-04

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Remarks from Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

- Executive Summary

- PART I - Background

- PART II - The Framework on Palliative Care in Canada

- PART III - Implementation and Next Steps

- Bibliography

- Appendices

Acknowledgements

Developing the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada would have been impossible without the participation and direction-setting provided by key organizations, groups and individuals, including provinces and territories (P/Ts) and other federal government departments. The End-of-Life Care Unit at Health Canada would like to acknowledge the contribution made by many stakeholders, including people living with a life-limiting illness and members of their families, health care providers, caregivers, researchers, as well as other individuals living in Canada. Their input and the deeply personal stories they shared with us online, in paper format and face-to-face, helped shape the Framework. Contributors and stakeholders shared a diversity of opinions and brought insight into hidden issues. For these perspectives, we are very grateful. The following document is a reflection of those insights and opinions.

Finally, this Framework would not have been possible without the close collaboration between the contributors and the End-of-Life Care Unit. The Framework on Palliative Care in Canada is the result of shared values and perspectives. Appendix A contains a list of the main groups and individuals that contributed to the development of this document.

Remarks from Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

Many Canadians find it difficult to discuss death, dying and end-of-life care with their loved ones and health care providers. We tend to avoid these conversations out of fear and pain. Yet, these topics are important to the well-being of dying people and their families. Encouraging Canadians to have honest and informed conversations about death and end-of-life planning can alleviate stress, anxiety and help to ensure that Canadians have the death that they wish.

Over time, our experience of death and dying has evolved alongside changing causes of death, care and supports, and cultural and social customs. The provision of palliative care has also evolved as a practice that seeks to relieve suffering and improve the quality of living and dying for Canadians and their families. However, we know we have more to do to improve person-centred care and equitable access, so that every Canadian has the best possible quality of life right up to the end of their lives.

Over the course of the summer of 2018, officials from Health Canada heard many stories of dedication and commitment about people living with life-limiting illness, caregivers, volunteers, and health care providers. There were, however, also stories pointing to significant gaps in awareness and understanding of, and access to, palliative care across Canada.

The message from these conversations was clear: the wishes and needs of Canadians nearing the end of life must be at the centre of our approaches to care. It is critical that their cultural values and personal preferences be voiced, understood and respected when discussing care plans and treatment options. This message inspired and influenced the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.

Together we can accomplish much by exemplifying compassion, learning from each other, and working collaboratively. It will take a concerted effort from all of us to continue to advance palliative care for Canadians. I invite all those who have a role to play to join in implementing the findings of this Framework.

The Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

Minister of HealthExecutive Summary

In late 2017, the Act providing for the development of a framework on palliative care in Canada was passed by Parliament with all-party support. During the spring and summer of 2018, Health Canada consulted with provincial and territorial governments, other federal departments, and national stakeholders, as well as people living with life-limiting illness, caregivers and Canadians. The findings from that consultation, as well as the requirements outlined in the Act, provided the foundation for the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.

In Part I, the Framework provides an overview of palliative care, setting out the World Health Organization's definition in the Canadian context. The Framework describes how palliative care is provided in Canada, and the roles and responsibilities of the numerous individuals and organizations involved. It lays out the purpose of the Framework as providing a structure and an impetus for collective action to address gaps in access and quality of palliative care across Canada. It also provides a brief description of the consultative process.

Part II, the heart of the Framework, sets out the collective vision for palliative care in Canada: that all Canadians with life-limiting illness live well until the end of life. Key to this vision is a set of Guiding Principles, developed in collaboration with participants of the consultative process. These principles reflect the Canadian context and are considered fundamental to the provision of high-quality palliative care in Canada.

In recognition of the dynamic state of palliative care in Canada, and its multiple players, this section provides a Blueprint to help shape planning, decision making, and organizational change within the current context. It identifies existing efforts and best practices, and sets out goals and a range of priorities for short, medium and long term action to improve each of the four priority areas:

- Palliative care education and training for health care providers and caregivers;

- Measures to support palliative care providers;

- Research and the collection of data on palliative care; and

- Measures to facilitate equitable access to palliative care across Canada, with a closer look at underserviced populations.

In this section, the Framework also lays out how we might recognize success as collective progress is made.

In conclusion, Part III outlines implementation and next steps, proposing a single focal-point to advance the state of palliative care. It concludes with the recognition that advancement of the Framework will require the collective action of parties at all levels, as well as the flexibility to evolve and respond to new ideas and emerging needs over time.

PART I - Background

What Is Palliative Care?

Death and Dying in Canada

- Of the over 270,000 Canadians who die each year, 90% die of chronic illness, such as cancer, heart disease, organ failure, dementia or frailty.

- By 2026, the number of deaths is projected to increase to 330,000, and to 425,000 by 2036.

- Despite Canadians' wishes to die at home, 60% die in hospitals.

Statistics Canada

The term "palliative care" emerged in Canada in the mid-1970's, initially as a medical specialty serving primarily cancer patients in hospitals. However, since then, the scope of palliative care has expanded to include all people living with life-limiting illness. With an aging population, demand for palliative care, delivered by a range of providers, has grown. Palliative care is an approach that aims to reduce suffering and improve the quality of life for people who are living with life-limiting illness through the provision of:

- Pain and symptom management;

- Psychological, social, emotional, spiritual, and practical support; and

- Support for caregivers during the illness and after the death of the person they are caring for.

Palliative care should be person- and familyFootnote 1-centred. This refers to an approach to care that places the person receiving care, and their family, at the centre of decision making. It places their values and wishes at the forefront of treatment considerations. In person- and family-centred care, the voices of people living with life-limiting illness and their families are solicited and respected.

Palliative care can be provided in conjunction with other treatment plans, and is offered in a range of settings by a variety of health care providers, including but not limited to: doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, social workers, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and spiritual counsellors.

For the purposes of this Framework, Health Canada has adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of palliative care.Footnote 2 Recognizing that the WHO definition is meant for a global audience, the Government of Canada, in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, developed a set of Guiding Principles. These principles are defined in Part II of the Framework, and allow for the definition of palliative care to be adapted to the Canadian context.

World Health Organization Definition of Palliative CareFootnote 3

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of persons and their families facing the problem associated with life-limiting illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual. Palliative care:

- Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms;

- Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process;

- Intends neither to hasten or postpone death;

- Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of care;

- Offers a support system to help persons live as actively as possible until death;

- Offers a support system to help the family cope during the person's illness and in their own bereavement;

- Uses a team approach to address the needs of persons and their families, including bereavement counselling, if indicated;

- Will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness;

- Is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

Palliative Care in Canada

Drivers of Change

While the provision of palliative care has improved over the years, a number of reportsFootnote 4 have identified ongoing gaps in access and quality of palliative care across Canada. For example, a 2018 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) noted that:

- While 75% of Canadians would prefer to die at home, only about 15% have access to palliative home care services.

- Recipients of home palliative care services are 2.5 times more likely to die at home, and are less likely to receive care in an emergency department, or intensive care unit.

- Adults aged 45-74 are more likely to receive palliative care than other age groups.

- While about 89% of people with life-limiting illness, such as a progressive neurological illness, organ failure, or frailty could benefit from palliative care, people with end-stage cancer are three times more likely to receive it.

Other societal changes and pressures driving the need for a Framework include:

Changing demographics and the increasing impact/pressure on caregivers: With the trend towards smaller family sizes and family members living further apart, the onus of caregiving rests on fewer family members, paid staff, and community. While family and friends provide the majority of care for those who are aging or ill, providing such care can create physical, emotional, and financial pressures. One in three caregivers reports distress and burnout.Footnote 5

Changing expectations for person-centred care: A growing number of Canadians expect to have a more active role in decision making about their care, including treatment choices and care settings.

Gaps in professional training: Few health care providers in Canada specialize in or practice primarily in palliative care. Canadian doctors and nurses report varying levels of training for and comfort in providing palliative careFootnote 6. In order to build broader capacity, there are increasing expectations on all health care providers to know how to deliver basic palliative care services. This translates into increased pressure on curriculum development, and education and training methods targeting those whose primary practice is not palliative care.

Increased public discussion about end-of-life care and decisions: On June 17, 2016, the Government of Canada passed legislation to allow for medical assistance in dying to be provided to eligible CanadiansFootnote 7. Public discussion around this issue included significant focus on the importance of Canadians having access to a range of care options at the end of life, including palliative care. The Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) legislation outlines a commitment to work with provinces, territories (P/Ts) and civil society to facilitate access to palliative and end-of-life care. Further, it commits Parliament to examining the state of palliative care in Canada five years after the coming into force of the MAID law.

To address these changes, governments at all levels, health care providers, stakeholders, caregivers, and communities must work together. The following section describes who is responsible for palliative care in Canada.

Benefits of Palliative Care

Patients with chronic progressive diseases, such as cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and HIV/AIDS, can develop severe physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms before death. There is strong evidence that palliative care is beneficial in reducing much of this suffering in patients, as well as psychosocial and spiritual or existential distress in families.

Journal of Palliative Medicine Special Report

Who is Responsible for Palliative Care?

There are many parties involved in the development, planning and delivery of palliative care in Canada. These parties range from the funders of services by governments and foundations, the planners and coordinators of services in provincial, territorial or sometimes regional and local health departments; researchers and data collection officers who consider all of the complex issues related to palliative care and how to capture information in order to make informed policy and program decisions. On a more personal level, health care providers, either specialist or non-specialist, provide a variety of treatments and pain and symptom management; while counsellors, volunteers and community members provide respite care, spiritual, grief and bereavement supports, among many others. At the centre of all of these parties, are the people receiving care, their families and caregivers. They too have a role and responsibility in the provision of palliative care in Canada.

With so many responsible parties, and individual P/Ts working from their own palliative care strategies or policies, there are differences across the country in how people receive palliative care.

Through consultations with federal departments, P/Ts, and stakeholder organizations, we were able to see what palliative care programs are currently being provided across Canada. (See Appendix B: Overview of Palliative Care in Canada for more information.)

Government of Canada

Over the years, the federal government has taken action to improve access and quality of palliative careFootnote 8. The following federal initiatives supported the action P/Ts and non-governmental organizations are undertaking to improve palliative care in Canada:

Policy Development

- Recommendations from Special Senate Committees examining end-of-life care (1995 and 2000);

- Appointment of Senator Sharon CarstairsFootnote 9 as Minister with Special Responsibility for Palliative and End-of-Life Care (2001-03);

- Canadian Strategy on Palliative and End-of-Life Care (2002-07): coordinated by Health Canada, five working groups included experts from across the country;

- Employment Insurance Compassionate Care Benefits and the Caregiver Benefit, which enable Canadians to take leave from work to be with a family member who is seriously ill (updated 2017);

- Appointment of a Minister of Seniors, who shares responsibility with the Minister of Health for ensuring government investments in home and palliative care have their intended impacts (2018); and

- Revision of Palliative Care Guidelines and increased palliative care competencies for health care providers in correctional institutions by Correctional Services Canada (2018).

Funding Support

- Development of a framework to integrate a palliative approach to care across settings and providers (the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association's (CHPCA's)"The Way Forward initiative"), and a consensus process for determining Canadians' palliative care priorities (Palliative Care Matters);Footnote 10

- Support for development of resources and processes for training health care providers in palliative care (Pallium Canada);

- Support for Pan-Canadian organizations such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI), and Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC), which are working to identify gaps and opportunities for improving access to palliative care in a range of settings, and measurement of outcomes.

Research

- 2004-2009: research funding of $16.5 million through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to expand the volume and types of palliative care research.

- 2012-2017: research funding by CIHR of $494 million to support research on aging - some of which directly impacts palliative care, e.g. $14.8 million on research related to palliative care in cancer. As well other investments indirectly support palliative care, e.g., the Team Grant in Late Life Issues - a four year grant of $2.8 million to build research capacity and provide high-quality evidence to inform health and social care professionals and policy makers.

Provincial and Territorial Governments

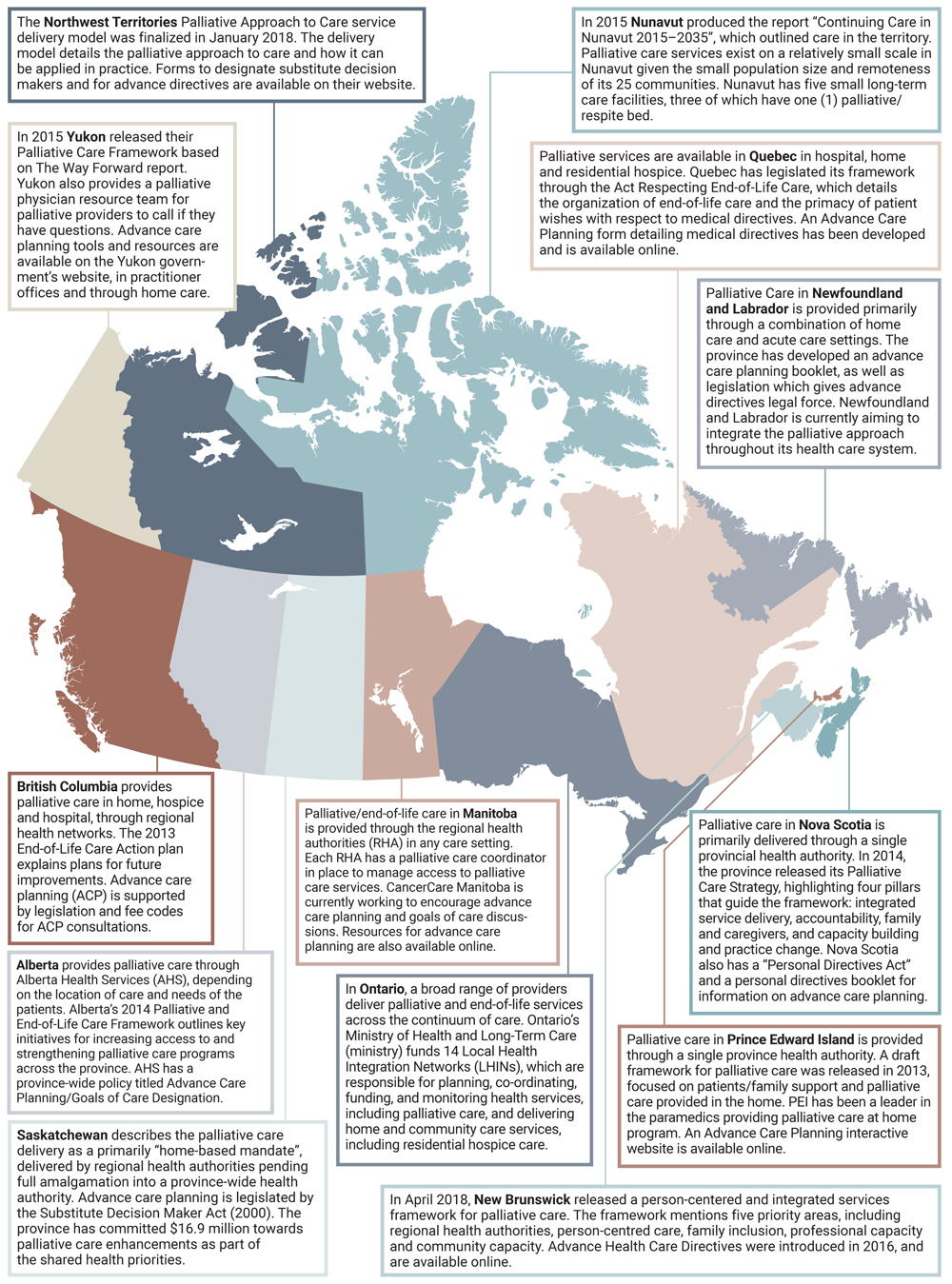

As described in the map that follows, most P/T governments have strategies or policies that address improvements to palliative care. Actions to improve palliative care can draw from and build on best practices from across the country to help identify opportunities and address gaps. More detailed descriptions of provincial and territorial palliative care programs are found in Appendix B, and best practices can be found in Appendix C.

Map of Provincial and Territorial Palliative Care Programs and Policies

Text Description

The image is a map of Canada, with each province and territory highlighted in a different colour. Below the map are brief descriptions of palliative care in each province and territory. These are the descriptions:

The Northwest Territories Palliative Approach to Care service delivery model was finalized in January 2018. The delivery model details the palliative approach to care and how it can be applied in practice. Forms to designate substitute decision makers and for advance directives are available on their website.

In 2015 Yukon released their Palliative Care Framework based on The Way Forward report. Yukon also provides a palliative physician resource team for palliative providers to call if they have questions. Advance care planning tools and resources are available on the Yukon government's website, in practitioner offices and through home care.

In 2015 Nunavut produced the report "Continuing Care in Nunavut 2015-2035", which outlined care in the territory. Palliative care services exist on a relatively small scale in Nunavut given the small population size and remoteness of its 25 communities. Nunavut has five small long-term care facilities, three of which have one (1) palliative/respite bed.

British Columbia provides palliative care in home, hospice and hospital, through regional health networks. The 2013 End-of-Life Care Action plan explains plans for future improvements. Advance care planning (ACP) is supported by legislation and fee codes for ACP consultations.

Alberta provides palliative care through Alberta Health Services (AHS), depending on the location of care and needs of the patients. Alberta's 2014 Palliative and End-of-Life Framework outlines key initiatives for increasing access to and strengthening palliative care programs across the province. AHS has a province-wide policy titled Advance Care Planning / Goals of Care Designation.

Saskatchewan describes the palliative care delivery as a primarily "home-based mandate", delivered by regional health authorities pending full amalgamation into a province-wide health authority. Advance care planning is legislated by the Substitute Decision Maker Act (2000). The province has committed $16.9 million towards palliative care enhancements as part of the Shared Health Priorities.

Palliative/end-of-life care in Manitoba is provided through the regional health authorities (RHA) in any care setting. Each RHA has a palliative care coordinator in place to manage access to palliative care services. CancerCare Manitoba is currently working to encourage advance care planning and goals of care discussions. Resources for advance care planning are also available online.

In Ontario, a broad range of providers deliver palliative and end-of-life services across the continuum of care. Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care funds 14 Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs), which are responsible for planning, co-ordinating, funding, and monitoring health services, including palliative care, and delivering home and community care services, including residential hospice care.

Palliative services are available in Quebec in hospital, home and residential hospice. Quebec has legislated its framework through the Act Respecting End-of-Life Care, which details the organization of end-of-life care and the primacy of patient wishes with respect to medical directives. An Advance Care Planning form detailing medical directives has been developed and is available online.

In April 2018, New Brunswick released a person-centered and integrated services framework for palliative care. The framework mentions five priority areas, including regional health authorities, person-centred care, family inclusion, professional capacity and community capacity. Advance Health Care Directives were introduced in 2016, and are available online.

Palliative care in Prince Edward Island is provided through a single province health authority. A draft framework for palliative care was released in 2013, focused on patients/family support and palliative care provided in the home. PEI has been a leader in the paramedics providing palliative care at home program. An Advance Care Planning interactive website is available online.

Palliative care in Nova Scotia is primarily delivered through a single provincial health authority. In 2014, the province released its Palliative Care Strategy, highlighting four pillars that guide the framework: integrated service delivery, accountability, family and caregivers, and capacity building and practice change. Nova Scotia also has a "Personal Directives Act" and a personal directives booklet for information on advance care planning.

Palliative Care in Newfoundland and Labrador is provided primarily through a combination of home care and acute care settings. The province has developed an advance care planning booklet, as well as legislation which gives advance directives legal force. Newfoundland and Labrador is currently aiming to integrate the palliative approach throughout its health care system.

Palliative Care Stakeholders

Individuals, families and caregivers are the core stakeholders in any discussion about palliative care. However, Canada also has a number of strong national and regional organizationsFootnote 11 with mandates and missions to improve access to palliative care. Many of these organizations are leaders in the field both within Canada and internationally. (See Appendix D for an Overview.) Some of the best practices from these organizations are highlighted throughout the Framework and many more are listed in Appendix C.

Through funding supports listed above, stakeholders improve access to palliative care through various means such as: promoting Compassionate CommunitiesFootnote 12 (CHPCA, Pallium Canada), developing resources and training health care providers in palliative care competencies (Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians (CSPCP), Pallium Canada), promoting advance care planningFootnote 13 (CHPCA), developing digital platforms to share knowledge and resources (Canadian Virtual Hospice (CVH), Carers Canada), supporting and promoting independent studies on palliative care (CIHR, Canadian Frailty Network (CFN)), convening experts and advocating on behalf of those living with life-limiting illness, their families and caregivers (Palliative Care Matters, Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada (QELCCC), CPAC). Many of these organizations have worked closely with all levels of government to provide input and guidance on palliative care programs and activities, as well as on the Framework consultations and development.

Roles and Responsibilities of Key Players

Individuals, Families, and Caregivers

- Promote their own well-being and care for their people (i.e., members of their family and friends)

- Express their perspectives/needs/preferences to guide their own care plans

- Actively participate in their community and broader society through community involvement (i.e., Compassionate Communities) Footnote 14

- Act as change agents in their community and champions of the vision, principles, and outcomes set out in the Framework

Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector

- Effectively represent people living with life-limiting illness and their families

- Act as a bridge between government and the public

- Provide a venue for collaboration and the sharing of knowledge and awareness

- Assist local communities in developing policies and programs appropriate to their needs

- Play a role in convening groups around shared interests and building system capacity

- Champion the vision, principles, and outcomes of the Framework

Health Care Systems/Organizations

- Act as point of first contact for those requiring palliative care

- Prioritize end-of-life care and treatment plans based on the needs and preferences of people and their families

- Tailor care plans so that people and caregivers can access care when and where they need it

- Connect persons and families dealing with a life-limiting illness to community resources

- Where relevant, develop and advance clinical policy, establish best practices and create standards and measurement metrics

- Where applicable, facilitate service delivery and supports (either directly or indirectly)

Compassionate Communities/Organizations

- Listen to the needs of those that they serve and advocate for those with life-limiting illness

- Champion the vision, principles and outcomes of the Framework

Governments

- Local

- Encourage local-level nurturing and spread of Compassionate Communities and Compassionate Organizations

- Champion the vision, principles and outcomes of the Framework

- Provincial/Territorial

- Provide direct or indirect health care services and supports, identify and respond to opportunities and challenges as needed

- Convene groups and facilitate ongoing dialogue

- Encourage and support communities in addressing local needs

- Set standards and legislate to achieve goals

- Where applicable, provide funding and oversight to health system service delivery organizations to deliver palliative care

- Where applicable, fund and administer specific benefit programs (palliative care drug access programs, etc.)

- Support the generation and sharing of information and knowledge

- Provide resources and supports to enhance capacity to deliver palliative care

- Foster the development of a jurisdiction-wide culture that promotes the vision, principles and outcomes of the Framework

- Federal

- Provide fiscal transfers to P/Ts through the Canada Health Transfer

- Administer additional transfer of $6 billion to P/Ts for targeted investments into home, community and palliative care over 10 years (2017 - 2027)

- Support and deliver programs and services (Employment Insurance Compassionate Care Benefit, and the Caregiver Benefit, etc.)

- Provide health care services to mandated populations such as First Nations, Inuit and Métis, veterans, and federal inmates

- Provide support for pan-Canadian organizations with mandates to address improvements to service delivery in targeted areas (Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC), Canada Health Infoway, etc.) and partners (Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH), etc.)

- Develop and implement policies and set standards to achieve goals, within federal role

- Provide cohesion for data collection to improve evidence and policy/program decisions

- Support research through the CIHR, knowledge translation through the CFHI, data and information collection through the CIHI

The Framework can be used by organizations with an interest in palliative care as they develop their policies and programs for the future.

What is the Purpose of the Framework?

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit's 2015 Quality of Death Index,Footnote 15 Canada has slipped from 9th to 11th out of 80 countries based on the availability, affordability and quality of palliative care. While the provision of palliative care has improved since its inception in the 1970's, a number of reports have identified ongoing gaps in access and quality of palliative care across Canada. There is considerable variation and disparity in palliative care services provided across Canada due to the fact that there are 14 different systems in place for providing care (13 P/T jurisdictions, as well as the Federal Government which has responsibility for mandated populations).

Recognizing the dynamic state of palliative care in Canada, the purpose of the Framework is to provide a tool for all parties with a responsibility for palliative care, to help shape decision making, organizational change, and planning within the current context. With the development of a common Framework, the Government of Canada aims to support policy and program decision making to ensure that Canadians are able to access high quality palliative care.

A Word about Policy Frameworks…

Policy frameworks are multipurpose tools. They can guide decision making, set future direction, identify important connections, and support the alignment of policies and practices, both inside and outside an organization. In short, policy frameworks are blueprints for something one wants to build, or roadmaps for where one wants to go.

An Act providing for the development of a framework on palliative care in Canada

In December 2017, Parliament passed into law An Act providing for the development of a framework on palliative care in Canada.Footnote 16 (See Appendix E)

The Act required the Minister of Health to conduct consultations with P/Ts and palliative care providers, to inform the development of a framework. The Government of Canada recognized the complexity of palliative care, and so, in keeping with a person-centred approach, the consultation process was expanded to include people living with life-limiting illness, families and caregivers, underserviced populations, non-governmental organizations, health care providers, and researchers to help shape the Framework.

How the Framework was Developed

In May 2018, the Health Canada launched a broad, multi-pronged consultation process, designed to reach Canadians, health care providers, caregivers, people living with life-limiting illness, and subject matter experts. The process used multiple platforms and networks in order to reach out across the country:

- An on-line discussion platform with moderated discussions covered palliative care definition, person- and family-centred care, advance care planning, access issues for those with unique barriers, caregiver supports, grief and bereavement, and community engagement.

- A Federal/Provincial/Territorial Reference Group shared information on existing and planned palliative care policies and programs across the country.

- An Interdepartmental Working Group of federal departments and agencies with a specific interest in palliative care including the departments of Citizenship, Immigration and Refugees, Correctional Services Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and Veterans Affairs, shared information on programs and services.

- Twenty-four bilateral discussions and focus groups were held with key stakeholders representing specific populations that face challenges accessing palliative care (such as perinatal, infants, children, adolescents and young adults, homeless, members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit, (LGBTQ2) community, etc.); other government departments (particularly those with service delivery mandates); Health Portfolio partners like CIHR; and pan-Canadian organizations, such as CFHI and CPAC.

- Two roundtables with people living with life-limiting illness, and families of children who had received palliative care, were held in September 2018.

- A face-to-face meeting of stakeholders including: people living with life-limiting illness, caregivers, palliative care providers and experts, and representatives from several P/Ts was held to discuss consultation results, and provide input on elements of the Framework in September 2018.

These consultations were vital to shaping the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.

Canada's Indigenous Peoples

Representatives of Canada's Indigenous peoples have been clear about the importance of culturally-appropriate palliative care for their communities. Health Canada and National Indigenous Organizations have started and will continue a discussion about Indigenous-led engagement toward the development of a distinctions-based framework on palliative care for Indigenous peoples, reflecting the specific and unique priorities of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation.

PART II - The Framework on Palliative Care in Canada

The Framework reflects a collective vision for palliative care aiming to ensure Canadians have the best possible quality of life, right up to the end of life.

Vision

All Canadians are touched by end-of-life care issues, either for themselves, or for someone they know. Our vision is for all Canadians with life-limiting illness to experience the highest attainable quality of life until the end of life.

The Framework has three main objectives:

- To clarify what we are trying to achieve, how to get there, and the various roles and responsibilities of those involved;

- To align activities within and between the different levels of government, to harmonize work between governments and other stakeholders, and to ensure there is policy alignment and consistency; and

- To influence and guide the work of governments, health care providers and non-profit organizations to improve palliative care for Canadians, as well as provide overall direction to collective planning and decision making.

The Framework is laid out in the following sections:

- Guiding Principles

- Goals and Priorities related to:

- Palliative care training and education for health care providers and other caregivers

- Measures to support palliative care providers and caregivers

- Research and the collection of data on palliative care

- Measures to facilitate equitable access to palliative care across Canada

- What Success Looks Like

- Framework Blueprint

A good death is an important part of a good life.

Amy Albright

University of Alabama

Psychological Benefits Society

Guiding Principles

In the spirit of bringing greater clarity and consistency to conversations about palliative care in Canada, the Framework sets out ten Guiding Principles. These principles were developed in consultation with people living with life-limiting illness, caregivers, P/Ts, and other stakeholders, and are considered to be fundamental to the provision of high-quality palliative care in Canada. They should be considered and reflected in program and policy design and delivery.

Palliative care is person- and family-centred care

Palliative care is respectful of, and responsive to, the needs, preferences and values of the person receiving care, their family, and other caregivers. It is facilitated by good communication. Individuals and families have personal preferences and varying levels of comfort in discussing, and planning for the dying process and death itself.

Death, dying, grief and bereavement are a part of life

A cultural shift in how we talk about death and dying is required to facilitate acceptance and understanding of what palliative care is and how it can positively impact people's lives. The integration of palliative care at the early stages of life-limiting illness facilitates this culture shift by supporting meaningful discussions among those affected, their families and caregivers regarding care that is consistent with their values and preferences.

Caregivers are both providers and recipients of care

Given their unique role in supporting individuals, family and other caregivers are respected by the health care team for their knowledge of the care preferences and needs of the person with a life-limiting illness. Palliative care encompasses the health and well-being of caregivers, and includes grief and bereavement support.

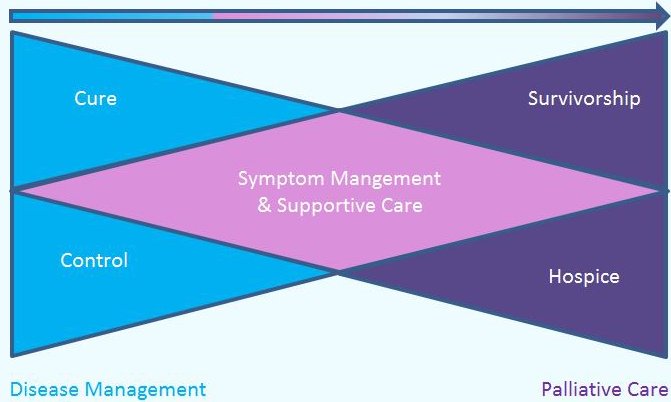

Palliative care is integrated and holistic

Palliative care is integrated with other forms of care (such as chronic illness management) throughout the care trajectory, and across providers. Services are provided in a range of settings (such as homes, long-term and residential care, hospices, hospitals, homeless shelters, community centres, and prisons). It is holistic, addressing a person's and their family's full range of needs - physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and practical - at all stages of a chronic progressive illness. It requires standardized or shared data systems in order to coordinate care during transitions from one setting or provider, to another.

Access to palliative care is equitable

Canadians with a life-limiting illness have equitable access to palliative care, regardless of the setting of care or personal characteristics, including, but not limited to their:

- Illness(es)

- Age

- Canadian Indigenous peoples status

- Religion or spirituality

- Language

- Legal status with respect to citizenship or incarceration

- Sex, sexual orientation or gender identity

- Marital or family status

- Race, culture, ethnicity, or country of origin

- Economic or housing status

- Geographic location

- Level of physical, mental and cognitive ability

A palliative approach to care requires adaptability, flexibility and humility on the part of the health care provider and the health system, in order to reach a shared understanding of the needs of each individual.

Palliative care recognizes and values the diversity of Canada and its peoples

Canada is a diverse country. Our population consists of myriad ethnic backgrounds, languages, cultures and lifestyles. While diversity is a natural characteristic of every society, being inclusive is a choice. Just as we Canadians pride ourselves on embracing our diversity and on being inclusive, palliative care recognizes Canada's diversity and encourages the adoption of inclusiveness, paying special attention to ensure that underserviced populations are taken into consideration as we aspire to universal access to palliative care.

Palliative care services are valued, understood, and adequately resourced

Palliative care helps identify and respond to people's physical, psychosocial, emotional and spiritual needs early, particularly when coupled with advance care planning. It can also avoid costly, ineffective measures that do not contribute to improving an individual's quality of life. The appropriate use of technology, community-engagement models, and public education are integral to delivering palliative care.

Palliative care is high quality and evidence-based

Program and policy decisions on palliative care are informed by evidence and relevant data. As such, research and data collection must be adequately supported to establish and validate an evidence base necessary for policy decisions and program planning.

Palliative care improves quality of life

Palliative care reduces suffering and improves quality of life for people with life-limiting illness and their families. Palliative care is appropriate for persons of all ages, with any life-limiting illness, and at any point in the illness trajectory. It includes support for family and other caregivers, including in their grief and bereavement. A palliative approach to care may be offered by a broad range of care providers and volunteers, in any setting.

Palliative care is a shared responsibility

The delivery of palliative care in Canada is the shared responsibility of all Canadians. This Framework encourages everyone, in their respective capacity, to work together to achieve the goals set out in this Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.

Goals and Priorities

The following goals and priorities were created in consultation with people living with life-limiting illness, their families, caregivers, P/Ts, other federal departments, and stakeholders. They are designed to guide short term (1 - 2 years), medium term (2 - 5 years) and long term (5 - 10 years) action to reach a shared vision on palliative care.

Given the complex, cross-sectoral nature of palliative care, no one party can be responsible for all of these priorities. They belong to all those involved with palliative care, including persons living with life-limiting illness, caregivers, all levels of government, communities, not-for-profit organizations, health care providers, the voluntary sector, and all Canadians.

Different organizations/institutions may choose to implement one or several of the priorities that follow, and will do so according to their own priority setting exercises. The timeframe over which these priorities span is dependent on who/which organization is implementing them.

The four priority areas for action in the Framework are as follows:

- Palliative care training and education for health care providers and other caregivers;

- Measures to support palliative care providers and caregivers;

- Research and the collection of data on palliative care; and

- Measures to facilitate equitable access to palliative care across Canada

Palliative care training and education for health care providers and other caregivers

A robust and skilled health workforce is essential to future sustainable palliative care delivery. There are many opportunities to improve ways in which health care providers, caregivers, and volunteers are trained, with some promising practices that can be expanded to meet this need. The following priorities refer to training and education programs for both health care professionals and informal care providers (caregivers, volunteers).

- Short term goal: training and education needs are identified for health care providers as well as other caregivers

- Medium term goal: palliative care providers have access to training, education and tools to meet the goals of individuals and their caregivers

- Long term goals: all providers have increased capacity to deliver quality care, and caregivers have appropriate supports to perform their roles

Priorities:

- Position individuals and their families and caregivers as central to palliative care training; ensure their cultural diversity is respected in the development of new tools and resources, including consideration of age-specific needs

- Work with Indigenous peoples to develop and disseminate mandatory cultural competency guidelines

- Work with organizations serving underserviced populations to develop and disseminate competency training for the provision of appropriate care for those populations

- Promote existing or establish new national standardized/accredited education for all health disciplines

- Develop national core competencies for palliative care specialists, and all other health care providers, including unregulated providers, such as personal support workers, etc., with a goal of equipping future health care providers with the competencies and skill base to provide palliative care services appropriate to the needs of the population being served

- Support the development of mandatory palliative care courses as part of undergraduate health provider curricula

- Explore best practice models that integrate palliative care training and education for interdisciplinary teams and others (support staff, volunteers, caregivers, etc.), including communication skills, and advocacy training as core competencies

- Ensure all training and education considers the continuum of care across all settings

- Invest in tool and resource development to ensure training programs are accessible and sustainable

- Develop an awareness campaign targeted to all health disciplines to improve awareness and understanding of the benefits of early integration of palliative care into treatment plans

Best Practices in Palliative Care Training and Education for Health Care Providers and Caregivers

Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care (LEAP)

Pallium Canada's LEAP courses, clinical decision and support tools, and toolkits provide learners with the essential, basic competencies of the palliative care approach.

Nursing Curriculum Resources Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing - Palliative and end-of life care teaching and learning resources for nurse educators.

Nova Scotia Palliative Care Competency Framework

Shared and discipline-specific competencies for health professionals and volunteers who care for people with life-limiting conditions and their families in all settings of care.

Just knowing about options is often the biggest barrier to receiving help… Awareness of bereavement supports is (also) really important. - Family Caregiver

Measures to support palliative care providers and caregivers

While many innovative supports exist across Canada, there is often a lack of awareness about them, and how to tap into them. Raising public awareness of these resources and the benefits of palliative care more generally would benefit palliative care providers, as well as their patients, clients, and other elements of the health care system. Improved understanding of existing programs helps to identify gaps and spur innovation to address them.

- Short term goal: supports required for palliative care providers and caregivers are identified, taking into account the range of wishes and needs of people with life-limiting illness

- Medium term goals: caregivers and providers are aware of and can access supports to meet the goals of the individual and their caregivers; there is an increased awareness of palliative care, and uptake of advance care planning and advance directives

- Long term goal: Canadians and caregivers understand and plan for palliative care and develop advance care plans

Priorities:

- Include caregiver assessment to understand the unique needs and capacity of each caregiver

- Explore effective models of consistent processes that ensure family members are involved in care planning and relevant care decisions

- Promote the use of technology to enhance communication between specialized palliative care providers and community-based care providers, including caregivers

- Examine how equitable access to bereavement supports and services can be established

- Build greater care capacity in communities (e.g. by fostering the Compassionate Communities movement) to alleviate pressure on health care systems and caregivers

- Ensure supports and services are culturally appropriate and available in both official languages

- Develop local public awareness campaigns in order to inform caregivers of the supports and services available to them

Best Practices in Measures to Support Palliative Care Providers and Caregivers

Canadian Virtual Hospice

Website providing information, an interactive "Ask a Professional" feature, and videos on "Living My Culture", "Indigenous Voices" and caregiving tasks.

MyGrief.ca and KidsGrief.ca

Free online grief and bereavement resources. Developed by a team of national and international grief experts together with people who have experienced significant loss.

Caregiver Compass

Tips and tools to help caregivers manage their responsibilities, including communication and decision making, navigating the health care system, financial and legal matters.

Research and the collection of data on palliative care

Sustained research and data collection is vital for long-term and continuous improvement in palliative care. Evidence is needed to address knowledge gaps, overcome current challenges and drive innovation towards effective practices. Ultimately, improved data collection and research will enhance the quality of life for all Canadians living with life-limiting illness and their families and caregivers, by providing much-needed data and evidence to drive improvements and support new models and approaches to care.

When the state of publicly funded palliative care in Canada is understood, health system planners can identify service gaps and develop strategies for improving care.

Access to Palliative Care in Canada

CIHI, 2018

- Short term goal: existing research and data collection gaps are identified

- Medium term goals: research is undertaken, applied, and promoted; and data collection activities are planned and reported to align with policy goals

- Long term goal: research, data collection, and best practices are implemented to inform and support policy decisions and government directions about palliative care

Research Priorities:

- Develop the evidence base for non-medical aspects of palliative care to promote comprehensive palliative care services, including psychosocial and spiritual supports

- Promote new and existing research networks and other collaborative processes, valuing quantitative and qualitative research

- Develop economic models and methodologies for further integrating palliative care into home and long-term care settings

- Promote models of care where primary health care professionals (e.g. family physicians or nurse practitioners) provide the majority of ongoing care and support, consulting with palliative care specialists only as needed

- Leverage existing work (i.e. Pan-Canadian Framework for Palliative and End-of-Life Care Research and its three main focus areas: Transforming Models of Caring; Patient and Family Centredness; and Ensuring Equity)

- Disseminate new evidence

- Ensure best practices are implemented across health care systems

- Build on current expertise and explore mechanisms to continue developing capacity in all aspects of palliative care research through a multidisciplinary approach that generates new knowledge, addresses gaps and improves care practices.

Data Priorities:

- Develop and promote the use of standardized person- and family-reported outcomes and experience measures, as well as screening and assessment tools across all settings

- Develop precise indicators related to palliative care, including distinctions-based approaches

- Work with national/international survey developers to add palliative care questions, including information on community care and Compassionate Communities (Census, Canadian Community Health Survey, General Social Survey, etc.)

- Use existing big data sources for more than one purpose and link databases to improve efficiencies in data collection and analysis

- Improve data collection on the uptake and consistency of advance care plans, focusing on where, how and by whom they are most used.

Best Practices in Measures to Improve Research and the Collection of Data on Palliative Care

Canadian Institute for Health Information

CIHI's 2018 report, Access to Palliative Care in Canada provides the baseline for what we know about palliative care service provision, across settings, in the last year of life.

Pan-Canadian Framework for Palliative and End-of-Life Care Research (Canadian Cancer Research Alliance, 2017)

This framework aims to build capacity to address unmet needs and broaden the scope of palliative care research for the future.

Improving End-of-Life Care and Advance Care Planning

The Canadian Frailty Network is supporting a program of research on end-of-life care planning and decision making, to improve the care of older adults living with frailty, their families and caregivers.

Measures to facilitate equitable access to palliative care across Canada

A consistent challenge to accessing quality palliative care stems from the lack of specialized palliative care providers in Canada. However, not all people receiving palliative care require highly specialized care. In fact the majority of them can have high quality palliative care provided by their caregivers, family doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, personal support workers, volunteers, and members of the community.

The following figure is a conceptual model of level of need of care for a person living with life-limiting illness, aligned against health care provider involvement. The base of the triangle represents the majority of individuals receiving palliative care, who require minimal specialist care, and whose symptoms can be managed effectively in home and community settings by their primary health care teams, caregivers and through community supports. This majority can benefit from a "palliative approach to care", which integrates core elements of palliative care into the care provided by non-specialists. As the complexity of needs increases, the health care providers become more specialized, but the number of people requiring this level of care is lower. This minority of people at the top of the triangle require the skills of palliative care specialists, often provided in the hospital or hospice setting.

Person's Needs vs. Relative Workforce Involvement

Figure developed by Palliative Care Australia, for the Palliative Care Service Development Guidelines, January 2018. It was kindly shared with Health Canada for the Framework on Palliative Care in Canada.

Text Description

A diagram shows six sets of figures side by side.

On the far left is a vertical arrow pointing upward, divided from bottom to top, in three equal thirds.

To the right of the arrow, is a triangle pointing upward, divided from bottom to top, in equal thirds.

To the right of the triangle is a set of three horizontal arrows pointing to the right, each starting from the middle of each of the thirds of the triangle.

To the right of the three arrows is a set of three rings of different sizes. The largest circle is at the bottom, the middle circle is in the center and the smallest circle is at the top.

Above the triangle is a rectangle and above the circles is another rectangle.

Sixth, at the base of the diagram are two miniature circles, red and one blue. The red circle indicates the predominant use of palliative care specialists. The blue circle indicates the predominant use of other health professionals.

To the far left, the arrow is labeled on the right with the words: "Increasing Complexity of Palliative Care Needs". The arrow is divided into three colours, red to the upper third, royal blue to the central third and dark blue to the lower third.

The triangle, to the right of the arrow, is divided into three colours, pale blue in the upper third, royal blue in the central third and dark blue in the lower third. The three arrows, to the right of the triangle, are pale blue with writing in them. The top arrow is labeled "Complex and Persistent". The center arrow is labeled "Intermediate and variable". The bottom arrow is labeled "Straightforward and predictable".

Each of the three circles to the right of the arrows are divided into two colours, red to the upper portion, royal blue to the lower portion. They differ in colouring with the upper circle being mostly red, the middle being almost equally red and blue, and the bottom circle being mostly blue - representing the intensity of specialist care compared to other health professionals.

Finally the rectangle above the triangle is black. It says "Person’s needs" and the rectangle above the circles is labeled "Relative workforce involvement".

The figure demonstrates that simple and predictable care requires about 25% of specialized palliative care providers and 75% of other health professionals. Intermediate and variable care requires an equal distribution of specialized palliative care providers and other health professionals. Complex and persistent care requires 75% of specialized palliative care providers and 25% of other health professionals.

This modelFootnote 17 requires non-specialist health care providers to have basic palliative care competencies and the ability to access specialists for advice, consultation, and referral when necessary. This aligns with the models of care already provided in Canada where primary care providers and specialists work together in areas such as cardiac or cancer care.

Shoring up these skills among non-specialist care providers would allow for more Canadians to have access to palliative care at the primary care level. This approach also allows for more active involvement of community, family and caregivers. Combining this model with movements such as Compassionate Communities, would be a significant step in providing full coverage and access to supports to improve quality of life through to the end of life. Furthermore, it provides for a more effective use of health resources, and allows the person living with a life-limiting illness to remain in the setting of their choice for as long as possible (e.g., home or community care).

Access issues are complex and occur in all settings, whether in dense urban settings or rural and remote regions of Canada. Many Canadians have difficulty accessing high quality palliative care due to system capacity issues, lack of understanding of the benefits of palliative care among health care professionals and the public, geography and demographic diversity (e.g., age, gender, culture, etc.).

- Short term goal: best practices and barriers to consistent access to palliative care are identified

- Medium term goals: mechanisms to facilitate consistent access are advanced and barriers are addressed; and action aligned with the Framework is taken at multiple levels (e.g., governments, stakeholders, caregivers, and communities) to improve palliative care and achieve the goals of individuals with life-limiting illness

- Long term goals: all individuals with life-limiting illness and their caregivers benefit from a palliative approach to care with all players cooperating to help achieve the goals of individuals throughout the continuum of care.

Priorities:

- Explore models of "patient (and caregiver) navigators" to promote the adoption of a single point of contact for individuals, their families, and caregivers when accessing the health care system - this is particularly important for those with cognitive impairments (e.g., Alzheimer's) as their illness gradually impacts their ability to navigate the health care system independently

- Promote access to telephone and electronic consultations (available 24/7) with interdisciplinary palliative care teams for individuals, families and caregivers to reduce hospital visits and support personal preferences to remain at home as long as possible

- Map national and local palliative care services and supports to highlight what is available but not well known, and where gaps exist

- Undertake awareness campaigns to promote existing services identified above, and more generally, the benefits of early integration of palliative care to improve quality of life for those suffering life-limiting illness and their families and caregivers

- Introduce discussions about death and dying in non-medical settings (such as schools, workplaces, etc.) to increase comfort in the subject and integrate the concept into daily life

- Increase the number of clinical and non-clinical service providers who are skilled in assisting individuals and their families and caregivers to have culturally sensitive discussions on end-of-life care including the development of advance care plans

- Define palliative care integration strategies within health care systems and regional health authorities, to implement across care settings and in the community, always through a culturally sensitive, age-appropriate lens

- Develop partnerships and linkages between health care providers, volunteers and community organizations to build inter-professional teams that deliver distinctions-basedFootnote 18 palliative care

- Recognize and ensure the continued inclusion of lay and spiritual counsellor positions in inter-professional health care teams to increase access to non-medical aspects of palliative care

- Invest in community-based initiatives to scale up and spread innovative models designed to improve access to palliative care services where and when they are needed, particularly for underserviced populationsFootnote 19

- Promote uptake of Compassionate Communities across Canada

- Develop services related to anticipatory grief and adjustment to losses before death to complement existing bereavement services.

All of the priorities identified above will have a positive impact on underserviced populationsFootnote 20; however, the following are more specific to their unique needs:

- Focus concerted efforts on increasing and improving remote consultation capacity

- Scale up and spread successfully proven models designed to increase community capacity in rural and remote areas, (e.g., Kelley Model for Developing Palliative Care Capacity, see Appendix C)

- Explore community-based approaches to specific illness or frailty, e.g., dementia friendly communities, Age-Friendly Communities, and Ontario's Schlegel Villages as holistic health care villages

- Increase support for non-medical care models, such as recreational therapy proven to improve communication in non-verbal children to express values and desires, ultimately improving quality of life

- Develop palliative care policies, programs, and services that are inclusive and considerate of all ages, sex and gender, and cultural diversity.

Best Practices in Measures to facilitate equitable access to palliative care

Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH)

PEACH aims to meet the needs of homeless and vulnerably-housed patients with life-limiting illness via a "trailblazing" mobile unit, providing attentive care on the streets, in shelters, and with community-based services.

British Columbia Centre for Palliative Care (BCCPC) Micro-Grants

Every year, the BCCPC gives small grants to 25 hospice societies and other non-profit organizations from across B.C., to help improve access to compassionate palliative care closer to home and empower people to have a voice in their own care through advance care planning.

Paramedics Providing Palliative Care at Home Program

Health authorities, cancer agencies and emergency medical services in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island collaborated with the CPAC and Pallium Canada to train all paramedics to support palliative patients at home. An interim analysis has revealed that paramedics are able to keep patients with palliative goals of care at home 55% of the time, when previously, nearly all would have been transferred to hospital. A similar program was implemented in Alberta.

With the adoption of the actions laid out in the priority areas, and concerted effort at all levels, we will see improvements in access to palliative care across Canada. The following table outlines some of the shifts in policy and programming we can bring about through this work:

What Success Looks Like - Shifts in Palliative Care Policies and Programming

| Less of… | More of…. |

|---|---|

| Palliative care treatment plans are focused primarily on controlling physical symptoms such as pain. | Palliative care is holistic, addressing the physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and practical concerns of the person and their family. An inter-professional team is mobilized, where possible, to support the full range of concerns, as needed. |

| Palliative care treatment plans are decided by the health care provider(s). | Palliative care is developed in partnership with the person living with life-limiting illness and their family, and respects their values, culture and preferences. |

| Palliative care is offered almost exclusively in last weeks of life. | Palliative care at appropriate levels is offered as early as diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. |

| Palliative care is discussed only after all other medical interventions are exhausted. | Palliative care is provided in conjunction with other medical interventions. Treatment plans are designed to improve quality of life through to the end of life. |

| Palliative care is only provided by specialists. | All health care providers (regulated or not) have foundational skills to provide a palliative approach to care, supported by specialists as needed. |

| Palliative care is delivered predominantly in hospitals. | Palliative care is available in the home setting or other setting of choice. |

| Access to palliative care is uneven across the country both by location and population. | Innovations and technology are used to ensure that palliative care supports and services are available to those who need them, regardless of where they live or their personal characteristics. |

| Caregivers are on the periphery of the health professional team, but may not be a part of the decision making or care planning. | Caregivers are central to the treatment planning process, respected and consulted as knowledgeable members of the care team, and provided with appropriate training and respite care. |

| There are no national standards for data collection or use, and few person-centred outcome or experience measures. There is insufficient support for research specific to palliative care. | Data are standardized or linkable across care settings and providers, and include measures of the outcomes and experiences of persons with life-limiting illness and their families. There are ongoing and sufficient financial and infrastructure resources to support data systems and research which provide the evidence base for improvements in palliative care. |

Following is a Blueprint - a summary of the Vision, Definition, Guiding Principles, and Short, Medium and Long Term Goals identified through the consultation on palliative care. This Blueprint is a tool that can be used to find common understanding and focus for policy makers and planners in the Canadian palliative care context.

Framework on Palliative Care in Canada - Blueprint

Guiding Principles

- Palliative Care is Person- and Family-Centred

- Death, Dying, Grief and Bereavement are Part of Life

- Caregivers are Both Providers and Recipients of Care

- Palliative Care is Integrated and Holistic

- Access to Palliative Care is Equitable

- Palliative Care Recognizes and Values the Diversity of Canada and its Peoples

- Palliative Care Services are Valued, Understood, and Adequately Resourced

- Palliative Care is High Quality and Evidence-Based

- Palliative Care Improves Quality of Life

- Palliative Care is a Shared Responsibility

Vision: All Canadians with life-limiting illness live well until the end of life

- Long Term Goals 5-10 Years

- Canadians and caregivers understand and plan for palliative care, and develop Advance Care Plans

- All providers have increased capacity to deliver quality care, and caregivers have appropriate supports to perform their roles

- All Canadians and caregivers have consistent access to an integrated palliative approach to care

- Research, data collection and best practices support and inform policy decisions and government directions about palliative care

- Governments, stakeholders, caregivers and communities cooperate to help achieve the goals of Canadians during the entire period of care

- Medium Term Goals 2-5 Years

- There is an increased awareness of palliative care, and greater understanding and uptake of advance care planning and advance care directives

- Palliative care providers have access to training, education, and tools to meet the goals of individuals and their caregivers

- Caregivers and providers are aware of and can access supports to meet the goals of the individual and their caregivers

- Mechanisms to facilitate consistent access are advanced, and barriers are addressed

- Research is undertaken, applied, and promoted, and data collection activities are planned and reported to align with policy goals

- Action aligned with the Framework is taken at multiple levels (governments, stakeholders, caregivers, and communities) to improve palliative care and achieve the goals of individuals with life-limiting illness

- Short Term Goals

- The range of wishes and needs of people with life-limiting illness are identified

- Training and education needs are identified for health care providers and caregivers

- Supports required for palliative care providers and caregivers are identified

- Best practices and barriers to consistent access to palliative care are identified

- Existing research and data collection gaps are identified

- A common framework is developed to guide action and improve access to palliative care in Canada

Palliative Care Definition: An approach to care that improves the quality of life of people of all ages who are facing problems associated with life-limiting illness, and their families. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.

PART III - Implementation and Next Steps

The goals and priorities laid out in this Framework were identified through consultation with people living with life limiting illness, caregivers, stakeholders and P/Ts; they include possible actions for all parties.

Moving forward, the federal government will collaborate with interested parties to develop a plan to implement those elements of the Framework that fall under federal responsibility. Although the timeframe of the Framework development process did not allow for a thorough engagement process with Indigenous peoples around palliative care, ongoing work will include discussions between Health Canada and National Indigenous Organizations about Indigenous-led engagement processes toward the development of a distinctions-based palliative care framework for Indigenous Peoples. This framework would respect the specific unique priorities of First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation. The implementation plan will also include the creation of an Office of Palliative Care, which is laid out in more detail below.

The Office of Palliative Care

The Framework on Palliative Care in Canada Act requires the Minister of Health to evaluate the advisability of re-establishing Health Canada's Secretariat for Palliative and End-of-Life Care. From 2001 to 2003, the Government of Canada appointed a Minister with Special Responsibility for Palliative Care (the Honourable Sharon Carstairs). A Strategy on Palliative and End-of-Life Care was implemented from 2002 to 2007. In order to support this Minister and coordinate efforts on the Strategy, Health Canada established a time-limited Secretariat. While the Secretariat ended in 2007, federal initiatives on palliative care continued.

Given the inter-jurisdictional, cross-sectoral nature of the issues identified in the development of the Framework, a single focal point is needed to help connect and facilitate activities at various levels seeking to improve access to palliative care in Canada. As such, Health Canada will establish the Office of Palliative Care (OPC) to provide high level coordination of activities going forward. The OPC will be resourced internally through existing funds within Health Canada.

In order to support the implementation of the Framework, the new OPC could:

- Coordinate implementation of the Framework;

- Connect governments and stakeholders and palliative care activities across Canada;

- Serve as a knowledge centre from which best practices can be compiled and shared;

- Align activities and messaging to support public awareness raising across Canada; and

- Work with stakeholders to facilitate consistency of standards in palliative care.

Health Canada will continue to work with jurisdictions and key stakeholders to more clearly define the OPC's roles and responsibilities, and will consider existing models and networks for format and function to leverage resources and avoid duplication. Creation of the OPC will coincide with the development of the Framework implementation plan.

Conclusion

This Framework outlines the vision, goals and priorities expressed by consultation participants to improve palliative care in Canada. The priorities are complex and require the collaboration of all interested parties, including persons with life-limiting illness and caregivers, academia, health care delivery organizations, health professional groups, community organizations, and all levels of government - we all have a role to play.

Throughout Health Canada's consultations, participants not only shared their lived-experiences and wisdom, but also their innovative ideas and leadership. The resulting Framework is a tool that any level of government or health care or academic organization can use for decision making, to guide organizational change, to inform health care training and education, and for workforce planning. The Framework can be used by people living with a life-limiting illness and their families to facilitate end-of-life discussions with their primary care teams, to learn about best practices, and to explore what supports exist where they live.

Health care systems are not static - they evolve to respond to pressures and meet the needs of citizens. This Framework will also continue to evolve over time and will be revisited by those who contributed to it, in order to ensure it reflects the current state of palliative care in Canada; roles will continue to be clarified and definitions will evolve with increased data collection and research. This is a living document - designed to be a starting place for continuous open dialogue as we address challenges and culture shifts together.

Bibliography

- Aged Care Guide. (n.d.). Care Plan. Accessed from: https://www.agedcareguide.com.au/terms/care-plan

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017).National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. 2nd ed. Sydney: ACSQHC.(https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/search/quality+health+service+standards)

- Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. (March 2002). A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care: Based on National Principles and Norms of Practice. Ottawa, ON. Accessed from: (http://www.chpca.net/media/7422/a-model-to-guide-hospice-palliative-care-2002-urlupdate-august2005.pdf)

- Canadian Medical Association (2014-2015). Palliative Care - Canadian Medical Association's National Call to Action: Examples of innovative care delivery models, training opportunities and physician leaders in palliative care. Accessed from: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/palliative-care-report-online-e.pdf

- Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians. (2017). Palliative Care Lexicon. Accessed from: http://www.cspcp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Palliative-Care-Lexicon-Nov-2016.pdf http://www.chpca.net/media/7763/LTAHPC_Lexicon_of_Commonly_Used_Terms.pdf

- Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary. (2012). End-of-Life. Accessed from: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/end-of-life

- Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary. (2012). Provider. Accessed from: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/provider

- International Association for the Study of Pain. (2018). Pain. Accessed from: http://www.iasp-pain.org/terminology?navItemNumber=576#Pain

- Journal of Palliative Medicine Special Report: PAL-LIFE White Paper for Global Palliative Care Advocacy is published by the « Journal of Palliative Medicine » (September 2018), in English and Spanish: (https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jpm.2018.0248)

- Palliative Care Australia. (2005). Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care for all Australians. PCA, World Health Organization Definition of Palliative Care. Accessed from: (http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/)

- Palliative Care Australia. (2008). Palliative and End-of-Life Care - Glossary of Terms, Ed 1, PCA, Canberra: (http://files.mccn.edu/courses/nurs/nurs490r/MaurerBaack/PowerpointFiles/Mod.%206%20End%20of%20Life%20Care/Palliative%20and%20end%20of%20life%20care%20glossary%20of%20terms.pdf)