Module II - Acquisition and Long-Term Management of Media Art Collections

1. Preamble

While museums first began collecting media artworks in the 1970s, their acquisition did not increase substantially until the 1990s. During this period, standardized approaches to managing media art collections did not yet exist. As a result, museums are revising their documentation methods and establishing long-term conservation strategies.

Artists have their own particular visions of their artwork's longevity and capacity to withstand the passage of time. By engaging in the acquisition process, the artist can help guide the work of curators, archivists, cataloguers and conservators. This enables museums to be autonomous in their ongoing management of the artworks.

Drawing on research efforts, experience and collaboration with DOCAM, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) offers a set of guidelines and case studies on the acquisition and long-term management of media artwork collections.

2. Considerations

2.1. Survey of Museum Management Practices for Media Artworks

In 2005, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) conducted a survey with 43 North American, Australian and European museums to better identify the management practices used for their media art collections. The survey provided an overview of current practices associated with the acquisition and long-term management of media art collections. The survey results clearly demonstrated the importance of developing management tools and methodologies for museums that acquire media artworks. Footnote 1

2.1.1. Acquisition Procedures

The study revealed that some institutions still revert to traditional documentation and conservation procedures when acquiring media artworks. Other institutions have introduced contracts, specialized questionnaires and databases adapted to such artworks.

2.1.2. Cataloguing Terminology

No standardized terminology currently exists among institutions. Media art is classified into different categories that vary per museum. Standardized classification terminology unique to media art and recognized uniformly by museum professionals would facilitate the cataloguing procedures used when new artworks are acquired. This would also benefit the long-term management of these artworks.

2.1.3. Original Artworks and Exhibition Copies

As a rule, museums archive the original content formats of artworks (videotapes, internegatives) and exhibit their copies, which are known as "exhibition copies".

2.1.4. Storage

Most institutions store their media artworks in specially adapted cabinets that are temperature and humidity-controlled (low humidity). Other institutions store their media artworks in the same storage units as paintings, sculptures and other media.

2.1.5. Migration and Emulation

The obsolescence of technological components is a growing concern for museums. In most cases, museum specialists will repair any operating equipment and, if necessary, conduct migrations. Migration consists of upgrading old equipment and materials to newer standards. Museums may also see a possibility to emulate the original technology used. Emulation consists of using a different method to imitate the behaviour of an original artwork. The new components tend to come from technologies developed since the original components were produced. Approval from the artists and their collaborators or successors is essential to the application of these strategies.

2.1.6. Maintenance

Maintaining media artworks requires collaboration between specialists in a museum's conservation and audiovisual departments. In most institutions, responsibility for maintaining equipment in a media artwork falls under audiovisual personnel rather than the curatorial or conservation teams. Ideally, each piece of equipment should have its own log, where the date, time and circumstances surrounding its use and its maintenance work are noted.

2.2. Content Formats and Operating Equipments

The information that constitutes the core of a media artwork is stored in what are known as content formats. These formats are integrated into the equipment that both operates the artwork and allows for the enactment of its behaviours. To adequately conserve the media artwork, the institution must, ideally, obtain and produce various versions of the artwork's content formats.

2.2.1. Content Formats

- Original artwork: As a rule, museums archive the original version (software, DVD - digital video disc, VHS - video home system, etc.).

- Reference copy: The retained content format should offer the best quality available in the format category, including the maximum amount of data stored, material stability, etc.

- Exhibition copy: The museum may make one or more exhibition copies from the reference copy. These might include a DVD format, positive record (film) or any other technology compatible with the era in which the artwork is being exhibited. It is this format that is used to present the artwork. Exhibition copies may use the same medium as the original artwork or another medium that is easier to exhibit, based on technical requirements and available equipment.Footnote 2

2.2.2. Operating Equipment

When a media artwork is acquired by a museum, the equipment needed for the artwork to function (for example, DVD player, CRT - cathode ray tube monitor, video projector) may not always be provided. Depending on the complexity of the artwork, the artist may recommend specific models. Acquisition considerations include technical stability, durability under repeated and prolonged use, ease of maintenance, and ultimately, availability of replacement parts. The possibility of the institution procuring more than one of the same model should also be part of this evaluation.

2.3 Long-Term Management

2.3.1. From Analog to Digital

One method of conserving analog artworks is to migrate the artworks to digital format. Analog technologies, such as CRT monitors and slide projectors, are fast becoming obsolete. Not only will replacement equipment no longer be available in the future, but individual parts also risk becoming scarce. As a result, it seems inevitable that the technology used in certain media artworks created in the 1960s will require migration. To ensure the exhibition of such artworks over the long term, museums may store a number of versions of the original in various formats, providing the artist is in agreement.

2.3.2. Historicity

The term "historicity" is defined as the characteristic of having existed in history. A media artwork may carry many meanings, depending on the period in history during which it is analyzed. Media artists use technologies that are representative of a given historical period, but the obsolescence of these technologies is inevitable. Curators and conservators must work together to ensure that the artwork retains its historicity, i.e. the context in which it was originally created and exhibited.

2.3.3. Historiography

The term "historiography" is defined as the study of the body of historical documents relative to a given historical period.Footnote 3 The creation of a media artwork must be placed within the context of different artistic and technological movements and trends. Writings relating to the history of a media artwork may be based on the study of sources from art critics, art historians and the artists themselves.

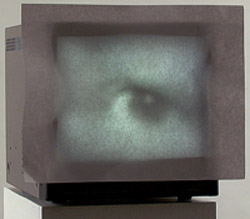

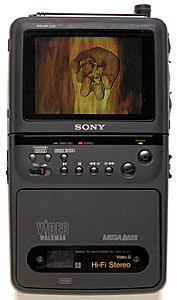

2.3.4. Visible Display Equipment

"Visible display equipment" used in a media artwork often conveys meaning or significance on an aesthetic, historical or conceptual level.Footnote 4 Its removal or replacement with more recent technology may erase or even corrupt the meaning of the artwork as conceived by the artist. For example, for his artwork Unreeling (1997) in the MMFA collection, artist Jacques Perron considers the CRT monitor as intrinsic to the artwork.Footnote 5 Likewise, artist Daniel Dion is very specific about the portable video player used in his artwork The Moment of Truth (1991), also part of the MMFA collection.Footnote 6 The artist's opinion on the type of equipment used can guide curators and conservators in their application of conservation strategies.

Unreeling

Videotape transferred to videodisk, monitor, paper, base, 1/3

154,8 x 22,3 x 33 cm (monitor and base)

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Gift of Jacques Perron

Photo MMFA, Brian Merrett

The Moment of Truth

SONY Video-Walkman video source footage on an 8mm video cassette, rechargeable batteries

14 x 9 x 4.3 cm, length: 100 seconds

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Purchase, Harold Lawson, Marjorie Caverhill, Harry W. Thorpe and Mona Prentice Bequests

Photo MMFA, Brian Merrett

3. Objectives of the DOCAM Case Studies

The DOCAM Research Alliance is collaborating directly with museums to provide assistance in the realisation of case studies of media artworks in their collections. These case studies allow museums to evaluate and improve their tools and long-term management practices. The following case studies were conducted by the Alliance's partner museums, and the findings of these studies are available on the DOCAM Web site:

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (1989), Nam June Paik, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts;

- In Your Dreams (1998), Gisele Amantea, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts;

- Unex Sign Nº 2 (from the Survival Series) (1983-1984), Jenny Holzer, National Gallery of Canada;

- The Table (1984-2001), Max Dean and Rafaello D'Andrea, National Gallery of Canada;

- Machine for Taking Time (2001), David Rokeby, Oakville Galleries; and Machine for Taking Time (Boul. Saint-Laurent), (2007), David Rokeby, Ex-Centris Complex;

- The Sleepers (1992), Bill Viola, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal;

- Dervish (1993-1995), Gary Hill, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal;

- Conspiracy Theory (2002), Janet Cardiff, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal;

- Beats and Butterflies (2006), Jean-Pierre Gauthier, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal;

- Générique (2001), Alexandre Castonguay, Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal;

- Embryological House (1998), Greg Lynn, Canadian Centre for Architecture.

In light of the findings, both the Cataloguing Structure Committee and Conservation and the Preservation Committee are respectively developing a Best Cataloguing Practices Guide for New Media Artworks and a Best Conservation Practices Guide for Artworks with Technological Components (2009) for museum professionals (to be published in 2009).

4. Recommendations

Acquisition and long-term management can require collaboration between many specialists: curators, archivists, cataloguers, conservators, audiovisual technicians, lawyers, etc. The objective of this section is to:

- Help museums assess the feasibility of an acquisition;

- Identify the resources museums need to document, conserve, install and re-exhibit a media artwork;

- Assist museums that already have media artworks in their collections in reviewing their management and conservation methods.

The following seven steps are recommended:

- Assemble and analyze the documentation relating to the artwork;

- Install the artwork;

- Prepare a questionnaire for the artist;

- Develop conservation strategies;

- Organize documentation in database and the artwork's archival file;

- Document future installations of the artwork.

These recommendations are based, among others, on the following DOCAM documents:

- Methodological Report on the Case Studies conducted at the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal et le Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, by Marie-Ève Courchesne, Methodological Report on the Case Studies conducted at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal et le Musée des beaux-arts du Canada (PDF)

- Rapport méthodologique sur les études de cas effectuées au Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, by Émilie Boudrias, Rapport méthodologique sur les études de cas effectuées au Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (PDF) (in French only)

Step 1 : Assemble and Analyze Documentation Relating to the Artwork

Media art has specific needs with respect to documentation, which is often provided by the artist at the time the museum acquires the artwork. Museums that already have media artworks in their collections can conduct an analysis of the accompanying documentation in order to determine whether it is specific enough to ensure effective management of the works. Ideally, the data collected will include the following:

A. History of the Artwork

The history of the artwork details all documentation since the creation of the artwork and any related events. It includes the following information:

- Biography of the artist;

- Iconography of the artwork;

- Publications on the artwork;

- Behaviour of the artwork: performed, networked, interactive, reproduced, duplicated, encoded or contained;Footnote 7

- Acquisition Report (approves the museum's acquisition of the artwork; signed by the Conservation, Curatorial, Administrative and Archive Departments)

- Examination Report (states the condition of the artwork upon its arrival at the museum);

- Conservation Report(s) (describes the current state of the artwork; it is completed when the artwork first enters the museum collection and thereafter if it is exhibited, loaned, requires conservation care, etc.);

- Spatial and volumetric requirements for the artwork's exhibition;

- Types of interactions possible between visitors and the artwork;

- Record of viewers' experiences with the artwork (in text, audio or video format);

- Communications between the artist, his/her commercial representative and museum personnel relating to the artwork (for example, e-mails, faxes, letters).

B. Description of Technological Components and their Operation

In addition to holding a detailed inventory regarding the artwork's components, the museum must, ideally, also specify:

- Component models and manufacturers as well as user manuals;

- Equipment that has not been provided with the artwork and must be furnished by the museum;

- Format of the artwork;

- Transformation of the artwork's structure and any elements added or removed over the years (for example, modifications, deterioration and restoration);

- Condition Report(s) (details the maintenance and transformation of the artwork over time).

C. Contracts between the Museum and Artist

Among other considerations, contracts cover the installation, exhibition, conservation and intellectual property of the artwork. Notably, contracts help to:

- Define the artwork: identify and describe the technological components that the museum is acquiring;

- Detail the long-term conservation strategies for the artwork authorised by the artist;

- Describe the optimal exhibition and installation context for the artwork;

- Mention the artwork's co-authors and collaborators;

- Identify any elements that the artist has appropriated from other artworks to produce this particular artwork;

- Evaluate the feasibility of a limited edition of the artwork;

- Authorize the exhibition of the artwork and archival documents as applicable (for example, ephemeral artworks and performances);

- Allow reproduction of the artwork for teaching, publishing and promotional purposes, which require different authorizations;

- Finalise the Agreement of Sale, Purchase Agreement or Deed of Gift between the museum, artist and, if applicable, the artist's commercial representative;

- Clarify the Copyright License (authorizes the copyright of the artwork from the "copyright holder" to the "owner" of the artwork; permits the owner to, for example, reproduce the artwork in publications and/or for conservation purposes).Footnote 8

D. Installation and Storage

The museum's documentation can also contain technical knowledge relating to the artwork, which is generally assembled by the installation technician, audiovisual technician, computer programmer, conservator, curator, etc. This technical knowledge can include:

- Exhaustive installation instruction manual, including photographs, diagrams, plans, and, as required, videos of the installed artwork and its components;

- Documentation on the technical operation of the artwork;

- Packing instructions and documentation for storing the artwork;

- Record of the artwork's previous installations and exhibition contexts (for example, photographs, floor plans and diagrams).

Step 2: Install the Artwork

When acquiring an artwork and planning its long-term management, museum specialists (installation technician, lighting and audiovisual technician, computer specialist, curator, conservator, etc.) should install the artwork using the installation specifications and guidelines provided by the artist or the owners of the artwork. Despite having these guidelines, it may still be necessary to ask that the artist or artist's collaborators be present for this exercise. During the installation process, museum professionals should:

- Check all documentation provided by the artist and complete it as required;

- Describe, document and analyze each step to facilitate future installations of the artwork;

- Describe, document and analyze the artwork's technological components (models, manufacturers), taking into account their operation and any possible deterioration;

- Define the behaviour of the artwork, specifying whether it is performed, networked, interactive, reproduced, duplicated, encoded or contained;Footnote 9

- Identify the risks of deterioration or obsolescence of the artwork's content format (source codes, internegatives, etc.) or operating equipment (video players, computers, projectors, etc.).

Step 3: Prepare a Questionnaire for the Artist

A questionnaire or interview with the artist allows the museum to gather missing information that is vital to understanding, operating and conserving the artwork. Interviews also allow artists to share their long-term vision of the artwork.

Focusing on the artwork's concept and potential problems, the questionnaire is given to artists, their successors, collaborators or galleries as applicable. Galleries can be contacted if the artist is not available to answer the questions during the ongoing management of the artwork. The questionnaire can cover the following aspects:

A. Concept

Describe the artist's creative process, as well as the concept, meaning and signification of the artwork within both an historical context and one specific to the artist's body of work. Identify and detail the components of the artwork and their operation in order to guide curators, conservators, archivists and technicians.

B. Exhibition

Define the optimal installation conditions for the artwork, and include references to previous presentations. These should focus on the characteristics of the architectural space, materials used, lighting and acoustics, and the best angle from which to physically approach the artwork. The ideal level of interaction and ideal exhibition layout should also be defined in order to help the museum recreate these conditions during subsequent exhibitions and ensure that the artwork is encountered as the artist intended.

C. Conservation

Identify the deterioration risks, such as breakdowns associated with the artwork's operation, wear and tear, repeated use, and the potential obsolescence of equipment. When acquiring the artwork, the museum should also take into account any technical transformations the artwork has undergone since its creation.

D. Intellectual Property

Define the conservation strategies that can be applied to respect the artwork's integrity and the artist's moral rights. The artist should also identify any co-authors involved in the artwork as well as anyone who collaborated in its creation and who may hold the copyright to any components (software, source code, etc.). In addition, the artist should specify whether any elements from other artworks were used in the artwork and whether other versions of the artwork exist or if it is part of a limited edition.

Step 4: Develop Conservation Strategies

The museum's various departments must work together to plan the conservation of the artwork. Each department should develop a plan based on the answers obtained via the questionnaire. It is necessary to:

- Define the authenticity and integrity of the artwork;

- Describe in detail the artwork's components, including their importance accorded by the artist with respect to the meaning and operation of the artwork;

- Target any potential conservation problems;

- Identify preventive conservation strategies, ensuring that deterioration, obsolescence and technological evolution are all taken into account.

Step 5: Organize Documentation in Database and the Artwork's Archival File

The documentation gathered during the acquisition process should be incorporated into the museum's database. Over time, as part of the long-term management of the artwork, the museum should include any new information in its database. Ideally, the database should be designed to enable continual updating. The terminology used in the database should be uniform, accepted, and used by all museums. These standardized terms should be drawn from glossaries, thesauruses and ontologies that have been developed by various recognized research groups, such as DOCAM, the Variable Media Network, and V2_: Institute for the Unstable Media.

The incorporation of data should include the following elements:

- History of the artwork and its presentations;

- Instructions and photos of the packing process;

- Instructions and photos of the installation and dismantling of the artwork;

- Video/audio of the artwork in an exhibition setting;

- Specific information about the equipment;

- Identification and photos of each of the artwork's components;

- Conservation strategies and actions;

- Comments (via a video or audio interview or a questionnaire) from the artist, collaborators on the artwork, and technicians, as applicable.

Various research groups are developing a standardized terminology that can be used by all museum institutions. The following resources are available for consultation online:

- Categories for the Description of Works of Art, The Getty Research Institute (English). (Consulted on August 22, 2008);

- Variable Media Glossary (PDF) (English and French). (Consulted on August 22, 2008);

- Glossary, Capturing Unstable Media, V2, Institute for the Unstable Media (English). (Consulted on August 22, 2008);

- Terminological resources for the media arts: glossary, thesaurus and ontology, DOCAM Research Alliance.

Step 6: Document Future Installations of the Artwork

Numerous museum departments should work together to document each installation, exhibition and dismantling of an artwork. A museum that loans an artwork should monitor the installation of these exhibitions in order to record any changes to the presentation (particularly if the artist and his or her collaborators are present when the artwork is installed). This continuous process is facilitated by the presence of a representative from the lending institution who is knowledgeable about the artwork's requirements. Specialists at the borrowing museum should be able to identify any changes made by comparing the artwork to the specifications that accompanied it.

Museums may also plan for the possibility of producing a pre-authorized audio or video recording of the visitors' experience. Certain media artworks require public participation or interaction. It may therefore be helpful to include descriptions of the visitor/user experience in the media artwork documentation.

Contact information for this web page

This resource was published by the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN). For comments or questions regarding this content, please contact CHIN directly. To find other online resources for museum professionals, visit the CHIN homepage or the Museology and conservation topic page on Canada.ca.