Digital Preservation Survey: 2011 Preliminary Results

See also: Digital Preservation Toolkit

Executive Summary

In the fall of 2011, CHIN launched a Digital Preservation Survey to collect accurate and timely information about the scope and the state of digital assets held by its member organizations. This report provides an overview of the information received, as well as an analysis of the results, on a question-by-question basis. The data received from survey respondents is rich, and would support additional, more detailed analyses of the current situation.

In all, 307 surveys were included in the analysis, representing a response rate of 22.3%. A number of organizations took the time to emphasize the extensive technical knowledge required to complete the survey. Not all organizations could find the resources to respond to the survey within the time-frame allowed.

Key survey results reveal that:

- Many member institutions don’t have the resources to complete an inventory.

- The number of obsolete carriers is quite low.

- The vast majority of respondents have digital assets, and can prioritize them for preservation.

- Most respondents use a small number of widely installed software packages.

- Many respondents have access to multiple storage locations.

- Some respondents don’t know the temperature and relative humidity in their storage space(s).

- A mechanism needs to be implemented that will guide new member organizations, and new volunteers within those organizations to older training topics such as digitization.

About the Survey

In late 2010 the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) began investigating the current state of digital preservation in the Canadian and international cultural and heritage communities. This was a logical extension of CHIN’s long-standing commitment to, and promotion of, “the preservation and presentation of Canada’s cultural heritage”.Footnote 1

As part of this investigation, in the fall of 2011, CHIN launched a Digital Preservation Survey to collect accurate and timely information about the scope and the state of digital assets held by its member organizations.

This report provides an overview of the information received, as well as an analysis of the results. Reaction to the data and analysis would be most welcome and can be forwarded to pch.RCIP-CHIN.pch@canada.ca.

Survey Methodology and Response Rate

The invitation to participate in the survey was extended to 1,377 organizations, which included all CHIN members for whom we had a valid email address in the fall of 2011. Of these, 158 visitors completed the entire survey, while another 149 visitors submitted partially completed surveys.

The survey contained 20 questions, divided into 3 sections:

- Inventory of Digital Assets

- Identifying Your Organization’s Needs, and

- Organizational Profile.

The questions are included in Appendix A.

The survey was available online for 6 weeks, from September 1 to October 13, 2011. Some organizations chose to return their copies by fax or email.

Though the survey maintained the anonymity of the respondents, they could choose to identify themselves in the final question of the survey. Only 64 organizations chose to do so. Given the small sample size, analysis of the results has been done at a high enough level to maintain the promised anonymity.

In addition to the findings presented in this report, a number of sub-divisions within the Digital Inventory (Section 1) and Organizational Needs (Section 2) data could be further analyzed from either a provincial or a budgetary perspective, though some aggregation of data might be required to protect the identity of survey participants.

A number of organizations, either within the survey or by direct communication with the survey organizers, took the time to emphasize the extensive technical knowledge required to complete the survey and the time required to inventory and report on their digital assets, both requisites to successful completion of the survey. Not all organizations could find the resources to respond to the survey within the time-frame allowed.

Survey Results: Organizational Profiles

First, the Organizational Profile questions (Section 3) were examined to ascertain whether the sample was representative of CHIN’s overall membership.

Provincial Participation

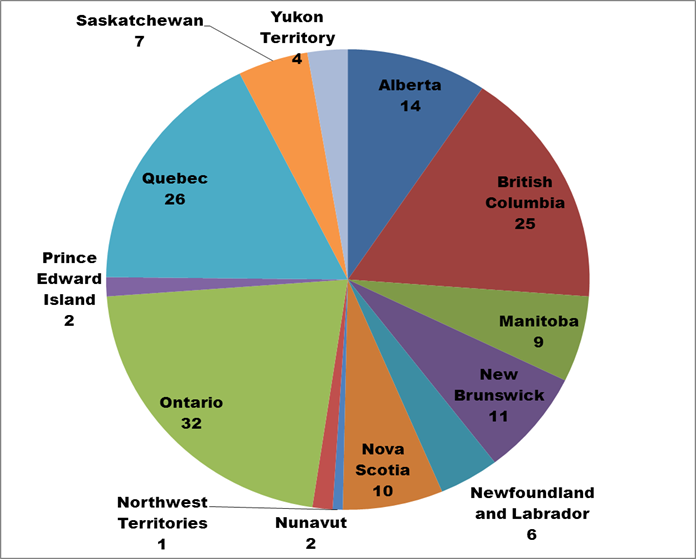

Figure 1. Text description: In which province or territory are you located? (Question 18)

The survey included respondents from all 10 provinces and 3 territories.

The survey results were then compared to CHIN membership rates by province. This comparison showed that all the provinces were slightly under-represented in their survey participation rate when compared to their membership numbers. The territories’ rates were either identical to their membership rates or slightly over-represented, given their smaller membership numbers.

Conclusion: Given the minor nature of the differences between CHIN membership numbers and survey participation numbers, it would appear that the survey attracted a representative sample of respondents, from a geographic perspective.

Budget Ranges

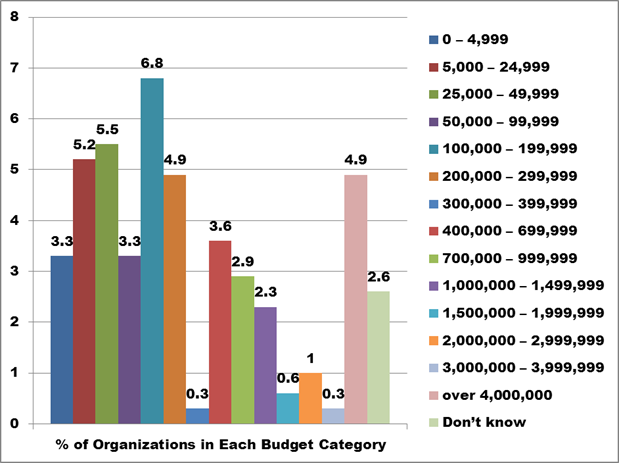

Respondents were asked to indicate their organizational budget within a series of 14 budget categories, ranging from a low of $0-$4,999 per year to a high of over $4,000,000 per year.

Figure 2. Text description: What is your organization’s current annual operating budget? Please provide your best estimate. (Question 19)

The survey included representation from all budget categories.

Conclusion: These results provide the assurance that a sampling of the complete range of organizations, from those with the smallest budgets to those with the largest, and every level in between, responded to the survey and is represented in the survey results.

Inventory of Digital Assets

Existence of Digital Assets

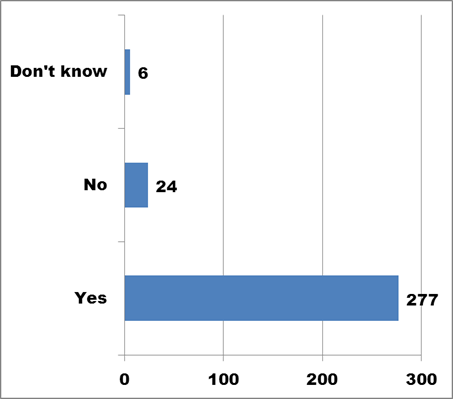

The initial question in the Inventory section asked respondents whether their organization had any digital assets.

Figure 3. Text description: Does your organization possess any digital assets? (Question 1a)

Conclusion: An overwhelming majority answered “Yes” to Question 1a, confirming that most CHIN members now create at least some of their records in digital form.

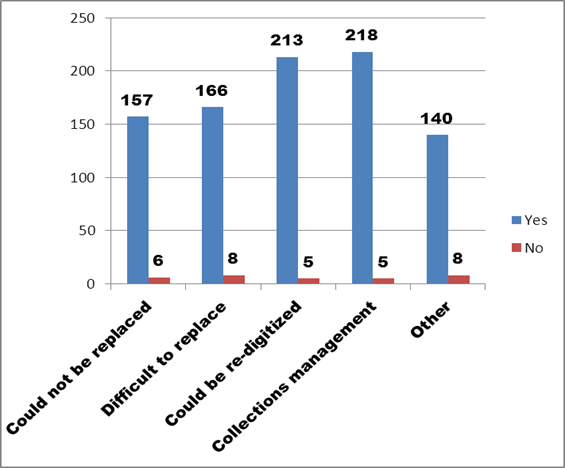

Digital Asset Types

Respondents were then asked to further define their digital assets. Five categories were offered, the first three relating primarily to cultural and heritage materials, while the last two categories included more administrative records, such as collections management systems, and the many types of business documents generated in support of museum activities. The five digital asset types are defined below.

- Digital assets which could not be replaced in case of loss. This category would include:

- artefacts created in digital form

- digital works of art

- virtual exhibits

- digital publications

- documents for which no physical original exists

- digitized copies of physical originals which no longer exist

- Digitized copies where the re-digitization process would be difficult, expensive and/or harmful to the original.

This category would include digitized copies of original physical objects, such as artefacts, works of art, analogue photographs, publications or documents which form part of your collection.

- Digitized copies which could be re-digitized fairly easily from the same source material in case of loss.

This category would include digitized copies of reference materials, such as analogue photographs or microfilm of items in your collection.

- Collections management records

- Other documents related to your collections, which exist only in digital form such as:

- audio guides

- acquisition files

- intellectual property agreements

- contracts

Most respondents identified more than one category of digital asset. The “Don’t know” answer was eliminated from Figure 4, below because it was statistically insignificant.

Digital Assets by Type

Figure 4. Text description: Does your organization possess any of the following types of digital assets? (Question 1b)

The most significant result (column 7, total = 218) identifies organizations that hold some kind of collections inventory in digital form. This finding is consistent with the early introduction of database-type applications, which could be used to list holdings. The preservation of these types of databases and spreadsheets is among the most widely tested and stable, and should not present any significant technical problems.

The second largest grouping (column 5, total = 213) identifies material that could be re-digitized. This data supports the hypothesis that many of the digital assets held in museums are photographs of artefacts.Footnote 2 Carrying obsolete or proprietary technical file formats forward over time can be difficult and expensive; the content of the files can also easily become damaged. As such, it is often easier and cheaper to re-photograph these artefacts instead.

There is a significant drop in numbers for those digital assets identified as Category 1 (“Could not be replaced”, total = 157) and Category 2 (“Difficult to replace”, total = 166). Combined however, they represent the largest category of digital assets identified in the survey (total = 323).

The final category (“Other”) potentially includes audio guides, either as textual scripts or as recorded sound files, as well as significant operational documents, such as acquisition files, intellectual property agreements or contracts. The latter would largely have been created with various brands of “office suite” software.

Conclusion: The first two categories of digital assets (“Could not be replaced” and “Difficult to replace”) represent the core of the digital preservation challenge for most organizations. The nature and degree of monitoring and intervention required to carry these assets forward through time can be further defined using the data collected in the remainder of the Inventory of Assets section of the survey.

Loss of Digital Assets

Respondents were asked if their organization had ever lost any digital assets, either by being unable to access them physically, or by losing the ability to open the content of the file.

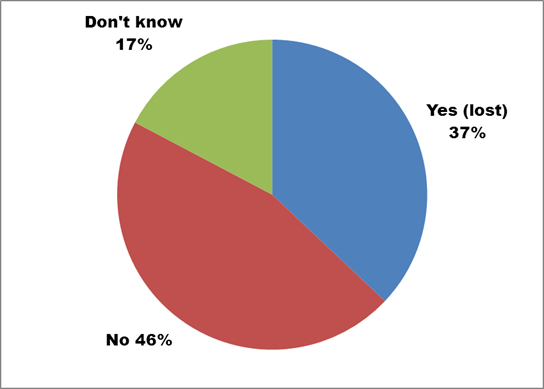

Figure 5. Text description: Has your organization ever physically lost, or lost access to, any digital assets? (Question 11)

Responses to Question 11 confirmed that many organizations have suffered through the difficulties surrounding the loss of digital data. The danger of loss can be exacerbated in an environment where continuity and institutional memory are interrupted by frequent changes in staff, a high reliance on volunteers and students, and a primarily seasonal schedule. The survey did not investigate the importance of the lost files, or how the organization recovered from the loss.

Conclusion: The ability of 83% of respondents to provide a definitive “Yes” or “No” answer to this question (as opposed to answering “Don’t know”) indicates a high level of awareness of the danger of data loss. This factor undoubtedly contributed to the significant number of preventive measures which have been implemented. For example, the regular creation of backup copies has been implemented by 98% of respondents (see Question 9, Digital Preservation Survey 2011: Preliminary Results).

Storage Conditions

The first line of defence in the preservation of digital materials is the provision of appropriate and stable storage conditions. Exact conditions will depend to some extent on the type of storage device being used. CDs and DVDs, for example, are among the most reliable digital carriers marketed to date. They tolerate a wide variety of storage environments, but like all physical carriers, including paper, film and magnetic tape, it is important that temperature and relative humidity do not fluctuate, ensuring a consistent and stable environment.

A second important preservation measure related to storage conditions is the maintenance of a second copy of digital assets in a separate geographic location. This straightforward action protects against localized disasters such as floods, fires, earthquakes, building collapse, etc.

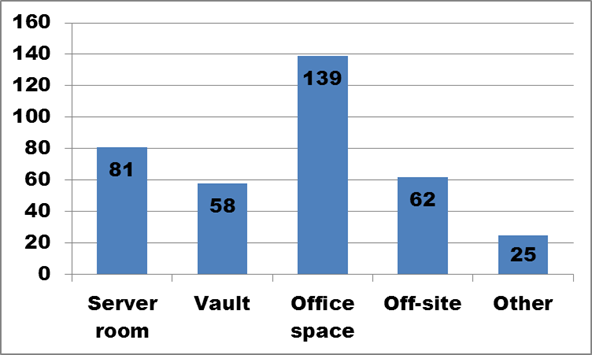

Figure 6. Text description: Please indicate if your organization has the following storage spaces for its digital assets. (Question 3a)

Forty percent of respondents to Question 3 identified more than one storage space. While the majority keeps digital assets in “Office space” (total = 139), just as many have access to specialized environments such as “Server rooms” and “Vaults” (81 + 58 = 139). Some survey respondents provided additional information about their off-site storage environments, identifying locations ranging from individual’s homes, to artefact storage areas, to the cloud.

Conclusion: Many organizations have access to specialized storage space.

Physical Carriers

Question 2 of the survey identified 34 different physical storage devices for digital assets, including magnetic, optical and flash memory devices. One of the unexpected survey results is that respondents use fully 32 of the 34 types identified. The absence of two formats – LTO2 and Blu-Ray-RE – appears to be random and offers no significant finding.

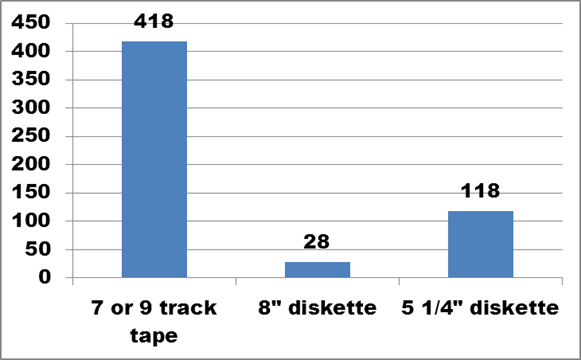

Figure 7. Text description: For the digital assets identified in Question 1, please identify the types and approximate number of physical carriers (that is, physical storage formats) that your organization currently has. (Question 2, partial)

Oldest Carriers

The three oldest formats listed were 7- and 9-track tapes, 8” floppy diskettes and 5 1/4” floppy diskettes. These formats are now obsolete, and attempting to read or extract data from them would undoubtedly prove to be difficult and expensive. Depending on the configuration, 9-track tapes could hold from 20 to 170 MB. These usually contained statistical data, rather than documents, and are unlikely to hold image or audio files. Both diskette formats had a very low storage capacity (360 KB and 1.44 MB respectively), and were introduced when early word processing programs were used almost exclusively to generate the paper copies which were still required to transact business.

As Figure 7 shows, these early formats exist in very small numbers among respondents, ranging from 28 x 8” diskettes to just over 400 x 9-track tapes. A number of respondents indicated that while they knew they held this format, the exact number of units couldn’t be provided until a proper inventory was conducted. Others noted that while they still held units in that format, they had no need to retrieve the data stored on it. Among the 307 respondents, only 11 (3.6%) confirmed holdings in these formats.

Conclusion: While the obsolescence of these three formats would seem to dictate an immediate response to their disposition, the history of the formats and the information provided in the survey strongly suggest that little of the digital content on these carriers needs to be preserved.

More Recent Carriers

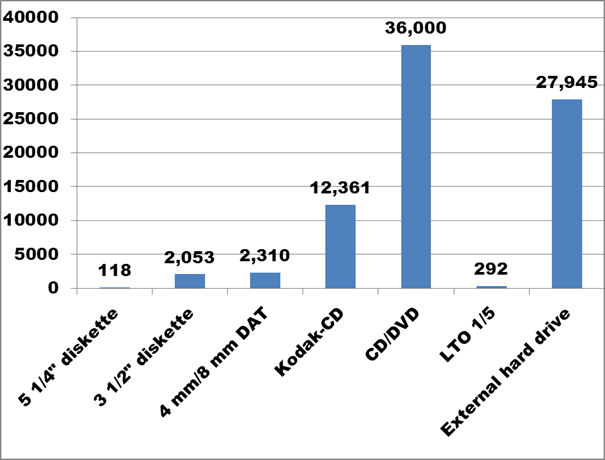

Figure 8 carries over from Figure 7 the 5¼” floppy diskettes in the first column, as a basis for comparison. Its 118 diskettes barely register on the graph, when compared to the larger number of 3½” diskettes and 4 mm and 8 mm Digital Audio Tape (DAT) cassettes.

Figure 8. Text description: For the digital assets identified in Question 1, please identify the types and approximate number of physical carriers (that is, physical storage formats) that your organization currently has. (Question 2)

Among the more recent formats displayed in Figure 8, the widespread adoption of CD/DVD technology, beginning approximately 15 years ago, as well as of external hard drives in the last 5 years or so, are clearly visible. These are the most common removable storage formats identified in the survey, leaving aside internal hard drives and network servers which support day-to-day operations.

While 3½” diskettes and 4 mm and 8 mm DAT cassettes are no longer in production, their withdrawal is quite recent (2005-2009). Today, 3½” diskette drives can still be purchased with a USB connector to permit access from current computers. The rapid obsolescence of Linear Tape Open (LTO) formats was always an overt part of their marketing – the current LTO-5 generation can only read two previous generations (LTO-3 and LTO-4). While the proprietary nature of Kodak-CD does present a technical problem, its large-scale use, at least among survey respondents, appears to be limited to larger organizations.

Conclusion: A significant majority of digital storage formats in use by survey respondents qualify as current technology. While re-copying will be required, there is time to plan for phased projects.

Analogue Formats

The survey also invited respondents to identify any other formats in use by their organization which were not listed in Question 2. Respondents identified an additional 32 formats in this “Other” category. On closer analysis however, over half were analogue audio and video formats which are not part of this study. The bulk of these formats are held by organizations which specialize in audio-visual content. Small numbers of the more widely adopted consumer formats, such as audio cassettes and ½” video cassettes, are present in the holdings of a number of survey respondents.

Conclusion: While not officially part of this survey, obsolete audio-visual formats present a risk of loss similar to that of early digital formats. In considering appropriate preservation actions, the initial requirement is to separate original content from pre-recorded material.

Logical File Formats

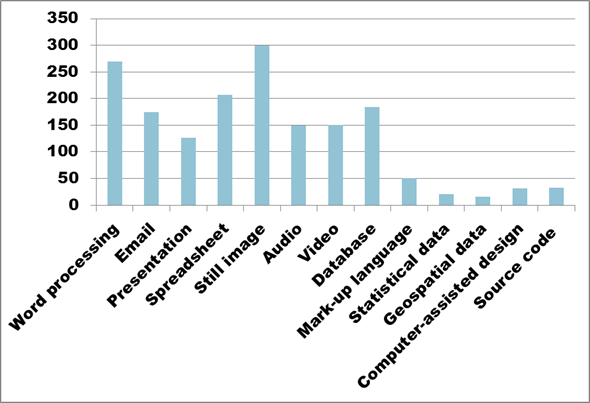

Figure 9. Text description: For the categories of digital assets that you have previously identified, please identify the types of digital file formats you use (Question 4a, partial)

In Question 4, the survey offered 13 digital file types created by specific categories of software, and asked respondents to identify those in use in their organization. Figure 9 confirms that software producing still image files is the most widely used among survey respondents (total = 300), followed closely by word processing (total = 270). Spreadsheet (total = 207) and database (total = 184) software, which are increasingly used interchangeably, represent the third and fourth most widely held file formats.

There is a significant drop in numbers between the eight most common file types and the five least common. The last five columns in Figure 9 represent fairly specialized types of digital files, and appear to be of limited concern to CHIN and its member organizations.

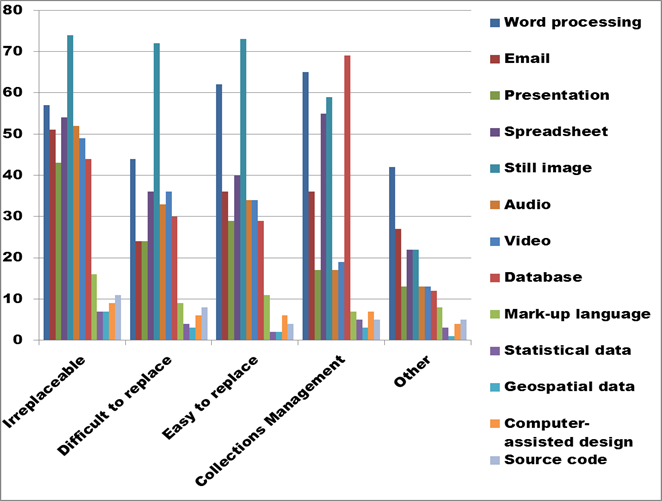

Figure 10. Text description: For the categories of digital assets that you have previously identified, please identify the types of digital file formats you use (Question 4a, partial)

In Figure 10, the five lowest ranked file formats have been eliminated, while the eight most common file formats are assessed against the five Digital Asset types defined in Question 1. The first three categories relate primarily to cultural and heritage materials, while the last two categories include more administrative records, such as collections management systems and the many “Other” types of business documents generated in support of museum activities.

Still image file formats clearly dominate in the “Irreplaceable” and “Difficult to replace” categories, as well as the “Easy to replace” category, with word processing files holding second place. Spreadsheets generally hold third place.

The “Collections management” category shows database files moving to the first position, supported by word processing and image files. The relatively strong showing of spreadsheet formats in this category may reflect the current preference among some users to design simple database applications in spreadsheet rather than database software.

This data is best analyzed in conjunction with the first part of Question 4, which asked respondents to identify the three most widely used software packages in their organization. Microsoft Office or one of its components (Word, Excel or Access) was identified by 40% of respondents. The second most frequently identified software was Adobe Photoshop and related extensions, such as Creative Suite, Elements or InDesign. The third most significant group focuses on museum-specific collections management software such as Past Perfect and Virtual Collections.

The need to salvage digital assets locked in obsolete logical file formats depends largely on the significance of the content of the files. The urgency of the situation is established by several factors, including whether the manufacturer of the software has withdrawn support for it, and whether the creator of the files still has access to the application(s) which were used to create the files. The survey’s file format data can also be linked to the age of the files, and their known readability. This additional analysis could produce as many as 130 tables which could be used to assess the current risk levels for specific file format types.Footnote 3

Conclusion: The uniqueness and importance of the content of the files, as well as the degree of obsolescence of the file formats and the availability of reliable conversion tools should all be used to establish a priority order for preservation efforts.

File Naming Systems

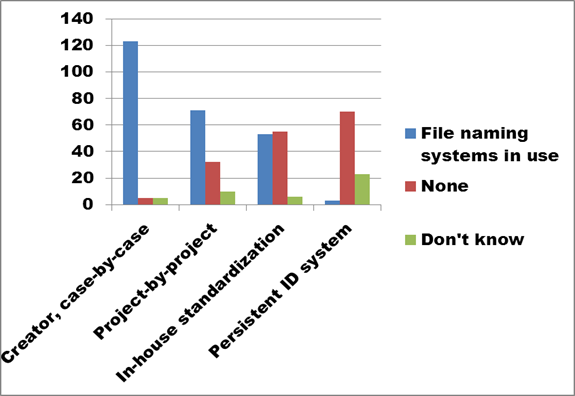

Figure 11. Text description: A file name is assigned to every computer file the first time it is saved. Sometimes, the choice of name is left to the file creator; in other cases, the organization will establish rules governing the naming of files. How are digital file names constructed in your organization? Check all that apply. (Question 5a)

Reponses to Question 5 show that three types of in-house standardization have been adopted by the majority of survey respondents. While the graph suggests positive results, a number of factors indicate the possibility of future problems.

First, the standardization tends to occur at quite a low level, affecting specific file instances, or specific projects, rather than providing a more all-encompassing naming protocol for the whole organization. The logic underlying these small-scale naming protocols can be lost over time, leaving organizations with file names that have lost much of their value in assisting in identification or facilitating access.

Second, most respondents chose more than one option, meaning that the 250 positive responses actually represent only 45% of survey contributors. This means there is frequently a mix of naming systems within an organization, which could exacerbate the loss of continuity suggested above. In fact, the larger-scale “in-house standardization” category is almost evenly matched between “Yes” and “No” responses. Few respondents have adopted persistent identification systems, such as ARK (Archival Resource Key) or DOI (Digital Object Identifier), which can be resource-intensive to maintain and are usually restricted to large organizations.

Finally, while 45% of respondents have adopted a standardized file naming system, fully 55% have not, suggesting the potential for inadequate control over digital assets in a majority of organizations responding to the survey.

Respondents’ comments added a number of important clarifications, with several noting that collections management assets were most likely to be controlled, often using standardized file names provided by the collections management software programs. In the case of operational records such as correspondence, a number of respondents indicated that their organization has a file classification scheme in place. Both file classification schemes and accession numbers can be used as the basis for file names which tie together operational records and collections assets.

Conclusion: Increased standardization in file naming practices in the future would better identify unique digital assets, facilitate retrieval and reduce duplication of preservation activities. However, historical file naming systems within organizations should be maintained. Renaming older files now could overwrite important metadata and separate the files from the history of their creation and maintenance. Intellectual control of older digital assets can best be addressed at aggregate control levels, such as the directory and the sub-directory (see Question 6, below)

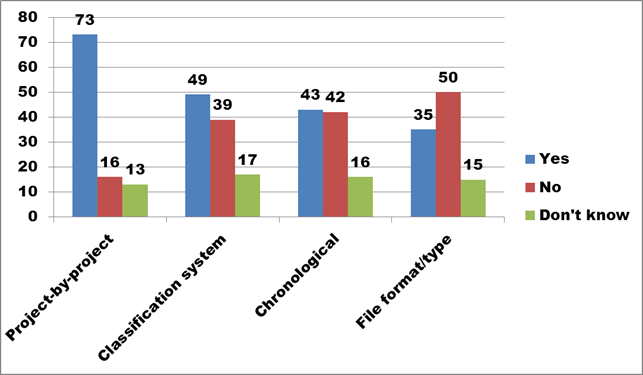

Aggregate Levels of File Organization

Not only do individual files need standardized naming practices, the larger directory and sub-directory structures where they are aggregated also require consistency. Question 6 divided the field into structured and unstructured data, generally representing databases as structured data, and individual computer files as unstructured data. The database structure imposes relationships between the database record and any attached digital objects. Unstructured data requires the intervention of the file creator to define categories and group files within each category.

Unstructured Data

Figure 12. Text description: Computer files are generally organized in directory and sub-directory structures. Sometimes, the organization of this storage system is left to the file creator; in other cases, the hierarchy of directory and sub-directory names is established by the organization. How are digital files organized in your organization? Check all that apply. (Question 6a)

When dealing with unstructured digital files, a majority of respondents (total = 73) develop directory and sub-directory structures on a project-by-project basis. As mentioned with the file naming practices discussed at Question 5 (above), this establishes standardization at a low level within the organization rather than providing a more all-encompassing whole-organization approach. The logic underlying these small-scale naming protocols can be lost over time, leaving organizations with file names that have lost much of their value in assisting in identification or facilitating access.

Directory structures based on an existing file classification system are more likely to tie into a larger organizational perspective, and increase the possibility that the relationship between general operational files and collections management information, dealing for example with the same artefact or the same donor, will be maintained.

Chronological approaches may reduce the volume of assets needing to be searched, but only if someone in the organization can remember the year in question.

Organization by file format can facilitate preservation activity, by grouping together all files in need of conversion at a specific time. However, it is the structure most likely to separate related files, thus fragmenting any overall organizational view of an activity such as an acquisition or an exhibition.

Structured Data

Given the widespread adoption of collections management systems, a great deal of digital information held by survey respondents is actually contained in databases. Related objects such as photographs can be linked to database records, thus maintaining the relationship between the two. A similar type of control can be established using mark-up languages such as XML and linked objects.

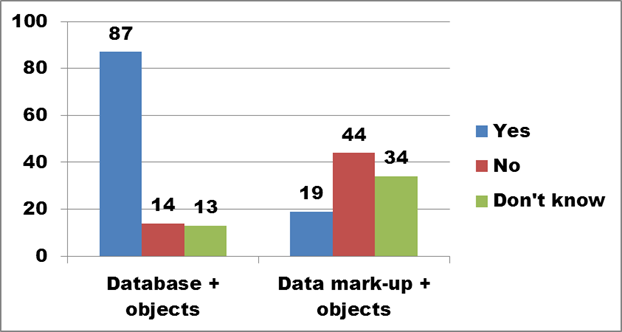

Figure 13. Text description: Computer files are generally organized in directory and sub-directory structures. Sometimes, the organization of this storage system is left to the file creator; in other cases, the hierarchy of directory and sub-directory names is established by the organization. How are digital files organized in your organization? Check all that apply. (Question 6)

Figure 13 shows that the substantial majority of respondents identify traditional databases, with a much smaller group adopting the newer mark-up based approach to structuring data.

In contrast to the responses to Question 5, between 30% and 50% fewer respondents indicated that they used more than one approach to organizing their digital assets. This consistency in establishing directory structures is encouraging, since a strong and consistent organizational structure for the files can impose order where the file names themselves do not.

Conclusion: A focus on unstructured data will provide the most significant increase in control over, and access to, digital assets held in CHIN’s member organizations. An analysis of Questions 5 and 6 together suggests the most straightforward approach would focus on strengthening the existing file organization level, while introducing more consistent file naming protocols for the future.

Security Measures

In Question 7, the survey asked about four types of security:

- physical security relating to the location;

- system security applied to the computing environment;

- specific security mechanisms attached to individual files; and

- security designed to protect digital assets which are being circulated or made accessible.

It is easiest to analyze these different types of security by separating them into several graphs.

Security Measures – Physical Security

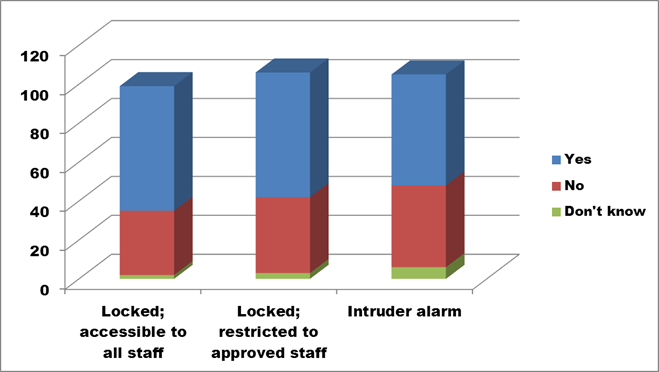

Figure 14. Text description: What security measures are in place to protect the digital assets? Check all that apply. (Question 7, part 1)

A majority of respondents have introduced some level of physical security to protect their digital assets. Those who indicated “No” could be reflecting numerous scenarios, including the organization’s dependence on computer equipment kept in volunteers’ homes, locations small enough that the museum’s building security is deemed adequate to protect everything within it, or reliance on network security (which is addressed in the next section).

Conclusion: The introduction of physical security measures can go hand-in-hand with the establishment of good storage environments (see Question 3, Storage Conditions).

Security Measures – System Security Applied to the Computing Environment

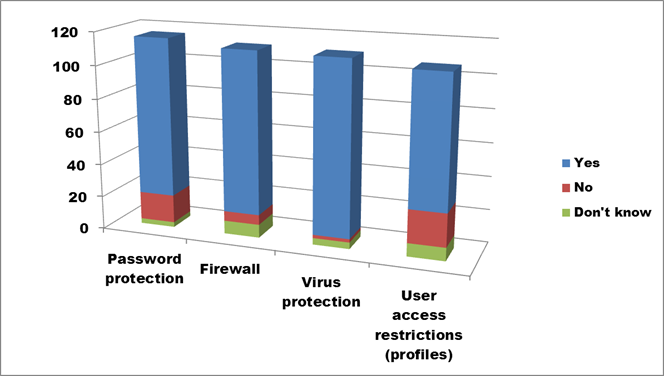

Figure 15. Text description: What security measures are in place to protect the digital assets? Check all that apply. (Question 7, part 2)

Protection at the level of the computing environment is widely implemented, with three of the four measures receiving over 95 “Yes” votes each. Only “User access restrictions” was significantly lower (total = 79), though in at least some cases, this is because the organization, and therefore its computer, is run by a single person. There is also a minor correlation between “No” answers and organizations with budgets below $200,000, reflecting the technical expertise required to implement and maintain these security features.

Security Measures – Security Mechanisms Attached to Individual Files and Security Designed to Protect Digital Assets Which Are Being Circulated or Made Accessible

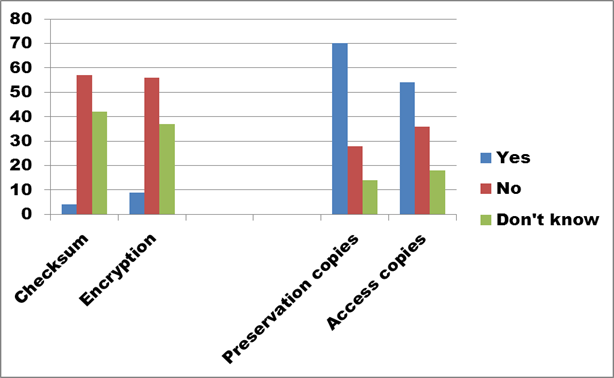

Figure 16. Text description: What security measures are in place to protect the digital assets? Check all that apply. (Question 7, parts 3 and 4)

Survey respondents have largely avoided applying intensive security measures, such as checksums or encryption, at the level of each individual digital asset. There are good reasons for this, as these measures are time consuming to implement and maintain. Loss of the encryption key is a real possibility in an organization depending on volunteers and summer students. While files could be recovered, it would undoubtedly drain the technological resources available to the organization. The adoption of an encryption system including lossy compression would permanently damage the files.

On the other hand, the existence of preservation and access copies offer significant protection to an organization’s digital assets while they are in circulation. Not directly addressed in the survey question is the extent to which computers holding master or preservation copies of digital assets can be accessed from other computers on an organization’s network or by anyone using the Internet itself. The preservation measures included in the survey assume the existence of off-line storage of at least one preservation copy of each digital asset to prevent the possibility of damage being caused by external intruders.

While overall results are excellent for the 112 respondents who answered this question, the picture is less encouraging when these numbers are integrated with the respondents who skipped this question. When combined, the overall existence of preservation and/or access copies drops to under 23% of survey respondents.

Conclusion: The results strongly suggest that survey respondents have focussed their security initiatives on those measures best suited to their organizational structure and resources. Continuing to focus on closing the identified gaps in physical security and circulation measures promises the most significant improvements given available resources.

The Right to Copy or Convert for Preservation Purposes

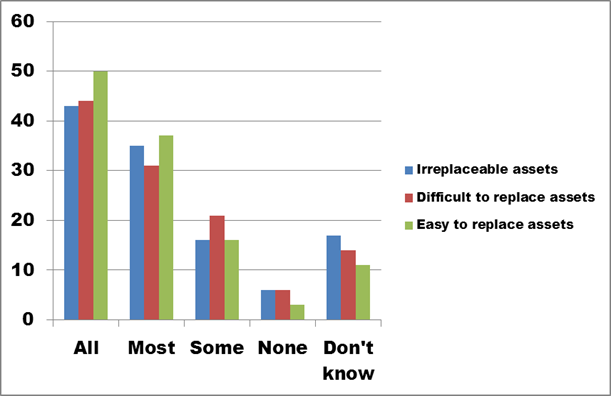

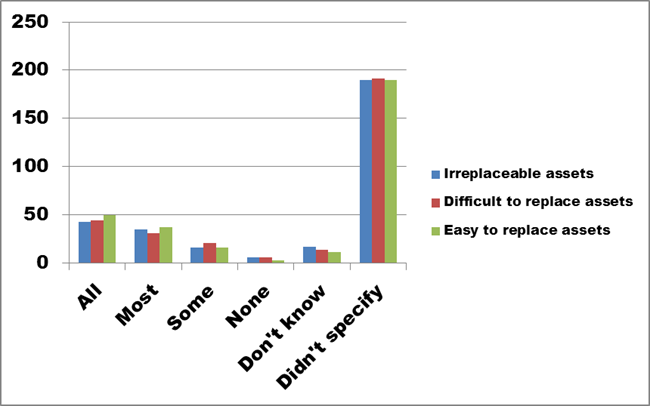

Figure 17. Text description: What proportion of your digital assets do you have the right to copy and/or convert for preservation purposes? (Question 8)

While a number of preservation measures are passive (storage conditions, hardware maintenance, monitoring activities, etc.), at least two activities are intrusive and can be challenged as potentially infringing on a creator’s intellectual property rights. These are the production of multiple copies, and the conversion of computer files from the file format in which they were originally created or acquired to one which the preserving institution considers more sustainable over the long term. In both cases, these actions are most easily pursued when the organization holds intellectual property rights for the digital asset being preserved.

Figure 17 clearly illustrates that survey respondents control intellectual property rights for a significant majority of their digital assets. This is particularly important in the “Irreplaceable” and “Difficult to replace” categories, where preservation activity is most likely to occur. The “None” and the “Don’t know” categories are very small, representing less than 8% of the total.

Figure 18 repeats the data contained in Figure 17, but has been expanded to include an additional category – those survey respondents who did not answer Question 8. This group includes 62% of respondents, or almost two-thirds of all survey participants.

Figure 18. Text description: What proportion of your digital assets do you have the right to copy and/or convert for preservation purposes? (Question 8)

While we might assume that these non-responses mean that respondents didn’t know whether their organization controls the right to copy or convert their digital assets or not, a few took the time to explain that this question could only be answered with a more detailed breakdown of their assets. Organizations conducting a more detailed inventory of their digital assets could include this information in their research.

Conclusion: The number of respondents who did not answer this question suggests that survey respondents do not know if they have the right to undertake preservation activities such as copying or file format conversion on their digital assets. Proceeding with copying and/or conversion activities without having obtained the right to do so, could cause negative reactions from donors and intellectual property right holders.

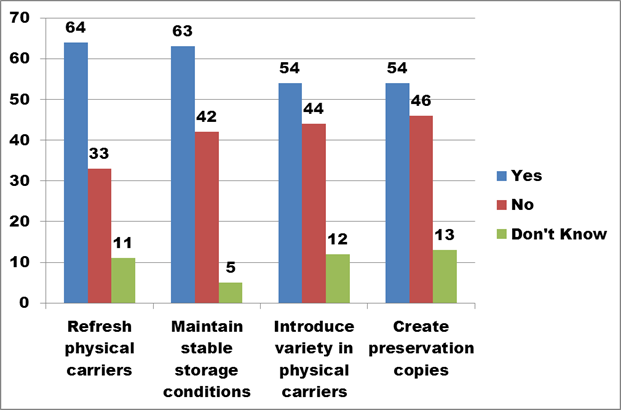

Preservation Measures Currently in Place

Question 9 of the survey listed 11 possible preservation measures and asked respondents whether each had been implemented in their organization. The results have been divided into three graphs to facilitate analysis. The first graph (Figure 19) shows the three most widely adopted preservation measures, while the second (Figure 20) shows the middle four. The final graph (Figure 21) shows the four least implemented preservation measures.

Three Most Widely Adopted Preservation Measures

Figure 19. Text description: Does your organization take any of the following measures to protect the digital assets in your collection? (Question 9)

The regular creation of backup copies is more of a day-to-day operational requirement than a preservation measure, because backup files are created in proprietary file formats and are dependent on the “restore” command of the operating system which originally generated the files. For example, Microsoft’s Windows 7 operating system can restore backup files created on a computer running Windows Vista or Windows 7, but no earlier Microsoft operating systems.Footnote 4 Backup files do provide the most easily implemented first-line of defence against a catastrophic loss of digital assets, and survey results show an 85% implementation rate (total = 98) among survey respondents.

The on-going maintenance of computer hardware, operating systems and software applications protects against the tendency by manufacturers to limit the interoperability among their own computer equipment and products, and with those of competitors. The commitment to maintaining hardware (total = 73) and software (total = 75) may reflect a lack of resources to upgrade as often as the computer industry would like, rather than the adoption of a conscious preservation strategy. However, longer periods of stability do reduce the frequency of copying and conversion cycles, thus reducing costs.

Four Middle-Ranked Preservation Measures

Figure 20. Text description: Does your organization take any of the following measures to protect the digital assets in your collection? (Question 9)

Figure 20 illustrates the extent of implementation of the four closely-related preservation measures which scored in the middle of the survey respondents’ choices.

The necessity to “Refresh physical carriers” is most often driven by the rapid obsolescence and constant improvement of older physical carriers marketed by the industry. This has tended to mask the fact that physical carriers can fail quite spectacularly due, for example, to problems with environmental storage conditions or with the manufacturing process. Exposure to extremes of heat and humidity can encourage the growth of mould or fungus, or result in the delamination of CDs and DVDs. Chemical de-composition of specific layers in a carrier can damage sections of stored data, or erase data completely. Refreshing physical copies is among the simpler preservation activities, but still requires significant resources, including blank stock, multiple new readers, and the time to create the new copies, perform quality assessments and generate new control records.

The final action on the graph – “Create preservation copies” – focuses on the digital assets themselves, rather than just the carriers on which they are stored. Before preservation copies are made, an organization must select one or more physical and logical formats, and commit to their long-term preservation. The adoption of more than one type and/or brand of physical carrier can protect against exactly the types of unexpected format failure described above. The fact that an organization must maintain two copies of digital assets on different formats increases costs.

“Maintain stable storage conditions” is the best measure available to extend the life of the physical carriers, and to reduce the cost of frequent refreshing cycles. To successfully extend the shelf life of a specific type of physical carrier, the organization must also ensure that the hardware that can read the format, and any software necessary to decipher the encoding used by the format, are kept in working condition.

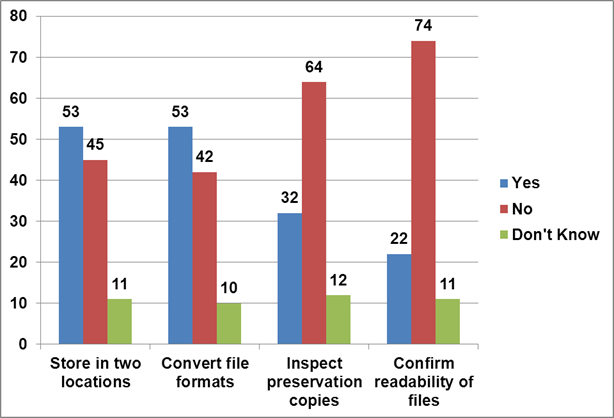

Four Least Implemented Preservation Measures

Figure 21. Text description: Does your organization take any of the following measures to protect the digital assets in your collection? (Question 9)

Figure 21 presents the four preservation measures least implemented by survey respondents. The concept of geographically separated storage locations was discussed in Question 3 relating to storage conditions (see Storage Conditions). Improvements in this area can quickly raise the overall level of digital preservation, and pave the way for possible collaborative storage initiatives, from simple exchanges of copies with other members, to LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe) networks, to the development of Trusted Digital Repositories.

The “No” answers outstrip the “Yes” answers for the last two activities – “Inspect preservation copies” and “Confirm readability of files”. Since only 17.5% of respondents (total = 54) create preservation copies, it is not surprising that even fewer organizations inspect them on a regular basis (total = 32, or 10.4%). Both the physical inspection of copies and the confirmation of readability of files are time-consuming technical activities, but the results may provide an early warning of loss of access to digital assets. This early awareness of impending problems can reduce losses, and control costs by allowing the time to properly research the question and implement the most appropriate solution in the most cost-effective manner. In some cases, damage to the physical carriers may be attributed to storage conditions, and can be slowed by improvements to environmental conditions rather than a full refreshing cycle, while problems with readability may be solved by acquiring an earlier version of a required software package, rather than converting to a different file format.

Conclusion: There is an encouraging amount of activity among CHIN member organizations which responded to the survey. Beyond encouraging individual organizations to implement the preservation measures identified in this survey, CHIN should also investigate the possibility of future regional, provincial or national collaborative ventures, which might offset the frequently substantial costs of digital preservation, and further spread the technical expertise required to implement them among CHIN members.

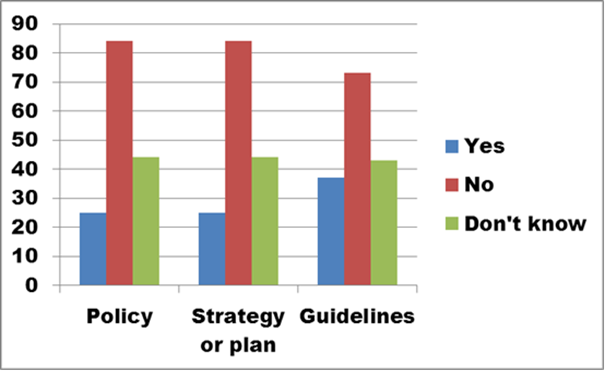

Policy, Strategy or Guideline Documents

Figure 22. Text description: Has your organization developed any of the following types of digital preservation documents? (Question 10)

Responses to Question 10 show a significant absence of policy, strategy and guideline documents within the organizations of survey respondents. The development of these types of guiding documents is a necessary pre-requisite to the implementation of active digital preservation programs. In many cases, the process can be guided by template documents which can be used as the basis for discussion and priority-setting within organizations.

Conclusion: The survey data identifies an area where there is room for significant improvement. These results reinforce the identification of “Preservation Strategies and Tools” in Question 14, In-house Digital Training Capacity as a significant training topic being requested by survey respondents.

Survey Results: Identifying Your Organization’s Needs

Section 2 of the survey included 4 questions about the organizational and training needs of CHIN members.

Organizational Needs to Support Digital Preservation

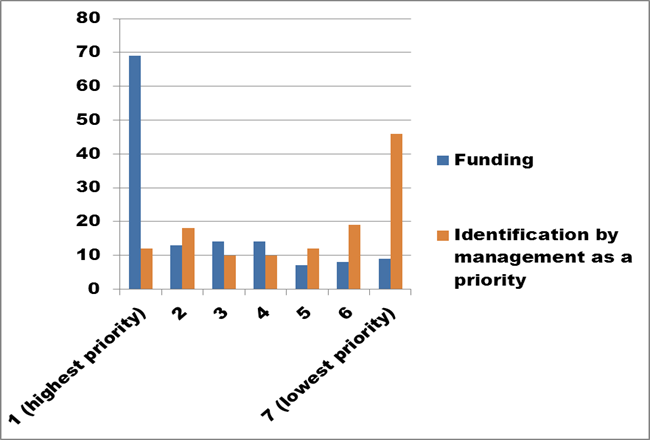

Question 13 offered 7 types of assistance which an organization might need to support a digital preservation program. Each of the suggested needs could be ranked from the highest priority, indicated by a 1, to the lowest priority, indicated by a 7. To analyze the results, the data has been separated into two graphs.

Two Top-Ranked Organizational Needs

Figure 23. Text description: What does your organization need in order to preserve digital assets? Please rank the options in order of priority. (Question 13a)

As an initial snapshot, Figure 23 shows only two categories of assistance – “Funding” and “Identification by management as a priority”. It is no surprise that “Funding” ranked first, outdistancing all other priorities. “Identification by management as a priority” received the lowest rankings among the identified needs. It did, however, receive some votes at every level of priority, and the additional analysis shows a correlation with the size of the organization (based on budget). The larger the organization, the higher this management issue was ranked, but for smaller organizations this need was deemed irrelevant.

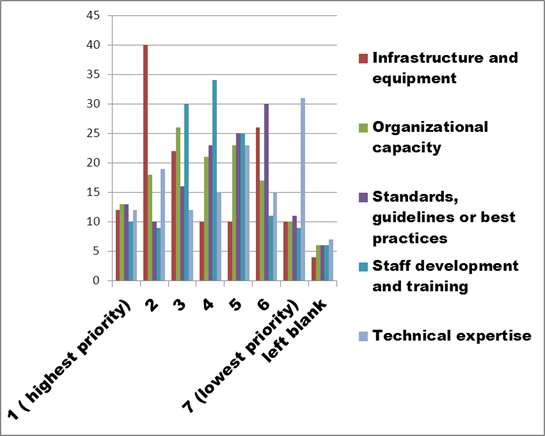

Middle-Ranked Organizational Needs

Figure 24. Text description: What does your organization need in order to preserve digital assets? Please rank the options in order of priority. (Question 13a)

While the vertical axis of Figure 23 covered from 0 to 80 responses, the range in Figure 24 is reduced to 0 to 45 responses due to the elimination of the highest and lowest ranked priorities. In this graph, the relative ranking of the five remaining needs is now more easily discerned and shows “Infrastructure and equipment”, a category strongly related to “Funding”, with a clear ranking as the second most important priority.

“Staff development and training” holds third position overall, based on a combination of high scores under both the third and fourth priority ranking. “Technical expertise” primarily received votes at the low end of the rankings, suggesting that organizations have learned these skills can be acquired in-house, contracted, or obtained from summer students. “Standards, guidelines or best practices” also scores at the low end of priorities, reflecting perhaps the substantial number of such documents already available online. This leaves “Organizational capacity” solidly in the middle.

A number of respondents took the time to identify additional needs, such as building renovations, additional storage space, supplies and additional staff and/or volunteers. Some comments reinforced the importance of topics which also received high rankings, such as funding, while others provided an important reminder of the diversity of needs among member organizations. Basic training, access to technical advice and expertise, and appropriate guidelines and bests practices continue to be required as new volunteers, new members, and new organizations join CHIN’s cultural and heritage network.

Conclusion: The overall ranking of organizational needs suggests that many survey respondents feel ready to move forward with digital preservation activities, if only their organization could assemble very specific and very concrete resources such as funding, the necessary infrastructure and equipment, and some training for staff. In this context, it is probably fair to assume that the training would focus on specific implementation plans and procedures inside the organization.

In-house Digital Training Capacity

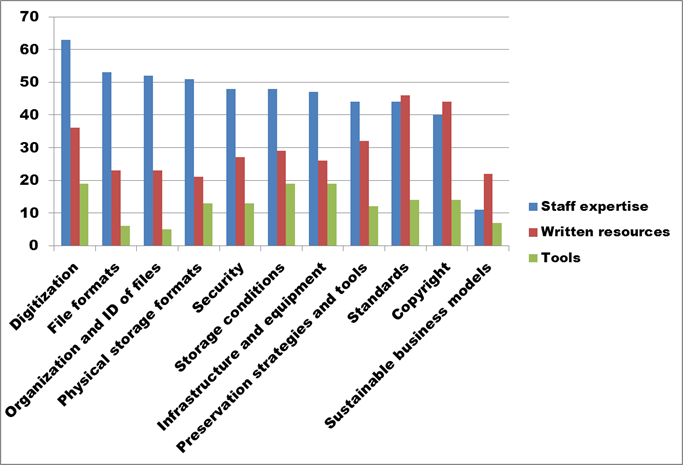

Figure 25. Text description: Does your organization have any in-house digital preservation training capacity in the following areas? Check all that apply. (Question 14a)

Having identified organizational needs in Question 13, Question 14 was designed to expand on the “Staff development and training” category included in that question, but from the perspective of available in-house training capacity which might be shared with other CHIN member organizations. Survey respondents were asked about three types of training capacity – “Staff expertise”, “Written resources, and “Tools” – in 11 subject areas relevant to digital preservation. Many respondents chose more than one topic.

The emphasis in recent years on the digitization of material for use on websites, and as part of virtual exhibits, is reflected in the existence of significant resources on this topic. As with other questions in the survey though, it is important to remember that not all respondents answered all questions. In the case of Question 14, almost 60% of survey respondents did not respond.

The strong showing of staff expertise in most of the components of digital preservation is encouraging, reinforcing the suggestion at Question 10 (see Policy, Strategy or Guideline Documents) that what is lacking is an overall, strategic sense of the issue, and the inter-relatedness of its parts, rather than expertise in specific technical questions.

For wide-ranging and complex issues such as “Standards” and “Copyright”, the responses indicate a strong reliance on written resources as well as staff expertise. The fairly low numbers for “Sustainable business models” reflects its more recent arrival on the scene and the lack of extensive written resources on the topic.

Conclusion: The survey results suggest that opportunities exist for CHIN member organizations to cross-train each other. Responses to Question 16, which are presented below, indicate a strong preference for face-to-face training. Taken together, the data from these two questions raises the question of whether regional coordination might provide new training opportunities.

Digital Preservation Training Needs

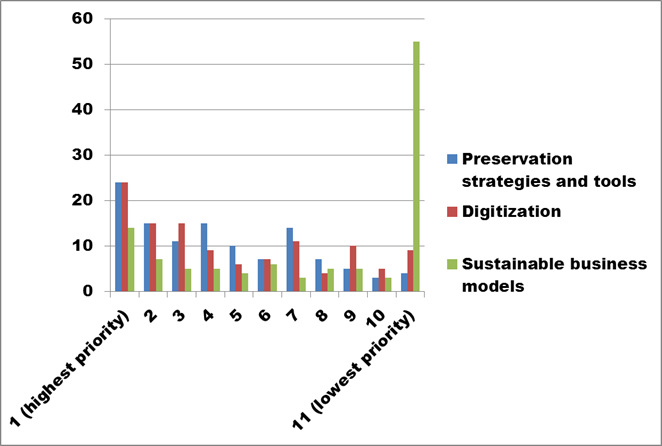

To confirm current training needs, Question 15 offered 11 training topics to be ranked in order of priority, as well as offering the opportunity to suggest other topics not included on the list. The results have been separated into two graphs to allow for a clearer analysis of the data.

Highest and Lowest Ranked Topics

Figure 26. Text description: What digital preservation-related skills training would benefit your organization? Please rank the options in order of priority. (Question 15a)

Figure 26 includes those two topics which were given the highest priority rankings by survey respondents, and the one receiving the lowest. The highest ranked topics received an equal number of votes at both the number one ranking (total = 24 votes each) and the second place ranking (total = 15 votes each).

The importance given to “Preservation strategies and tools” reinforces the earlier suggestion (at Question 10, Policy, Strategy or Guideline Documents, and Question 14, In-house Digital Training Capacity) that survey respondents are fairly knowledgeable about specific components of digital preservation, but would appreciate an overview of the whole field in order to better position their plans and priorities within it. The most emphatic statement is the ranking of “Sustainable business models” as the lowest priority topic.

The importance given to “Digitization” might be considered a surprise, given the amount of development and training work that CHIN did during the Canadian Content Online Strategy (CCOS) period from 2001 to 2010.

Conclusion: While digitization plays only a marginal role in the preservation of analogue materials – primarily by reducing the handling and exposure of original artefacts – this ranking confirms its continuing importance to survey respondents. It also points to the importance of updating CHIN resources to reflect new information, and in particular the growing body of knowledge about digital preservation. Early documents about the adoption of digital technology rarely discussed preservation, suggesting that, as with analogue materials, it could be dealt with later. Experience with digital assets, and ongoing research into its various aspects, has now concluded that the best time to address digital preservation concerns is during the planning process, prior even to the creation of new material.

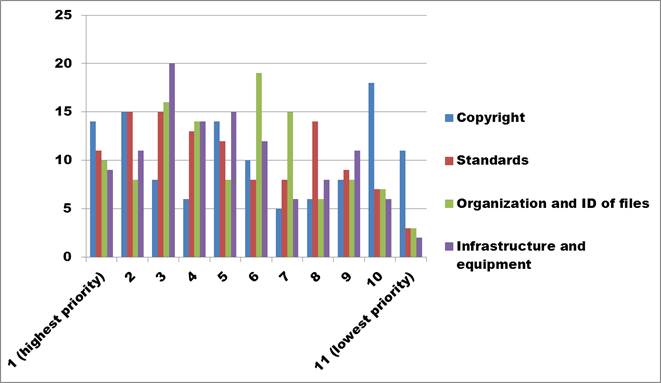

Middle Ranked Topics

Figure 27. Text description: What digital preservation-related skills training would benefit your organization? Please rank the options in order of priority. (Question 15a)

Figure 27 includes the four training topics which ranked in the middle of the priorities, after “Preservation strategies and tools”, “Digitization” and “Sustainable business models” were removed. “Infrastructure and equipment” has a clear lead as the third-ranking priority, while ”Copyright” is most strongly ranked in the top two and the bottom two, suggesting perhaps that it is a topic of ongoing importance with some respondents already well-versed on the subject, while others are just beginning. Both “Standards” and “Organization and ID of files” rank near the middle of the group, with “Standards” holding a slight advantage given the wide-ranging nature of the topic.

Conclusion: As discussed above, CHIN should draw attention to the existence of older resources on the Professional Exchange website, including those on copyright and standards.

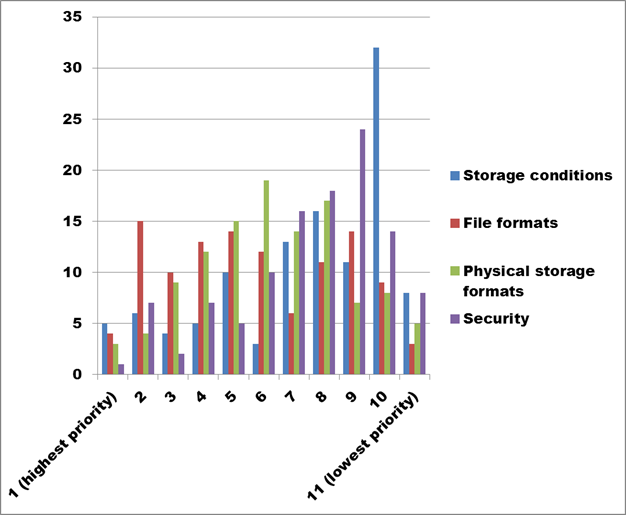

Lowest Ranked Topics

Figure 28. Text description: What digital preservation-related skills training would benefit your organization? Please rank the options in order of priority. (Question 15a)

Those topics ranked as low priorities, as illustrated in Figure 28, all represent fairly straightforward technical topics.

Conclusion: When organizations make decisions relating to such topics as storage conditions or security measures, they generally rely on reports and recommendations provided by research organizations and large institutions working in the cultural and heritage field such as the Canadian Conservation Institute and Library of Congress.

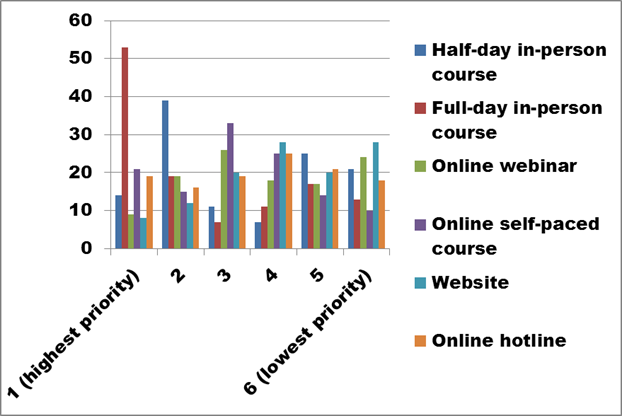

Preferred Delivery Methods for Training

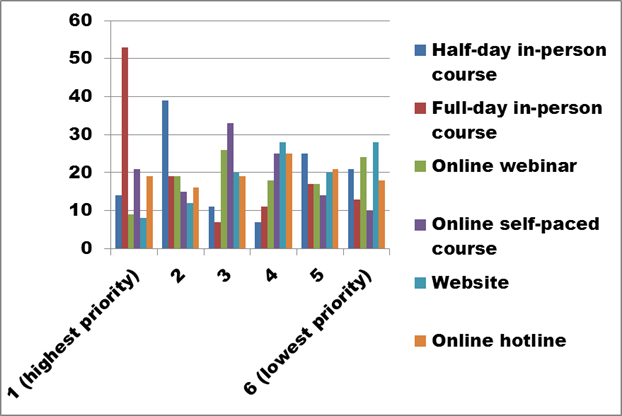

Figure 29. Identify your preferred delivery methods for training. Please rank the options from 1 (highest priority) to 6 (lowest priority). (Question 16a)

Survey respondents indicated a clear preference for in-person courses, ranking the full-day option (total = 53 + 19) and the half-day option (total = 14 + 39) as priorities 1 and 2, or 2 and 1. However, several comments acknowledged the difficulty and expense involved in face-to-face training efforts.

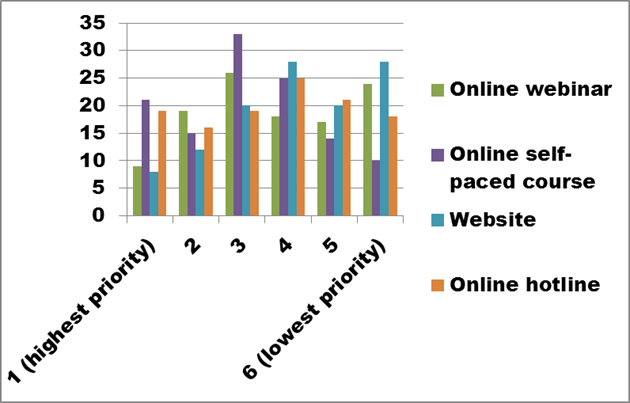

Figure 30 eliminates the top two choices to provide a clearer illustration of the priorities established for the four remaining options.

Figure 30. Text description: Identify your preferred delivery methods for training. Please rank the options from 1 (highest priority) to 6 (lowest priority). (Question 16a)

A second logical pairing from the options in the survey includes the “Online webinar” versus the “Online self-paced course”. Online webinars generally occur in real time, and thus require attendance at a specific time. This potential disadvantage is frequently balanced by the fact that participants can ask questions of the instructor. The problems created by the need for real-time participation are made more difficult due to Canada’s multiple time zones, causing early morning starts or late afternoon finishes, while conflicting with lunch hours. Once the initial presentation completed, webinars frequently remain accessible online but no longer allow any interactivity. In contrast, the online self-paced course is always available and can be scheduled to best accommodate a student’s time though there may be no provisions for asking questions of those who prepared the course material. Figure 30 shows a higher rating for the “online self-paced course” option, undoubtedly reflecting scheduling difficulties for staff and volunteers.

The final two options in Question 16, “Websites” and “Online hotline” offer diametrically opposed approaches to assistance. Websites, like online courses, are always available, but information on specific topics may be harder to find and, unlike prepared course material, may not move coherently from introduction to conclusion, or be presented at an appropriate level for all participants. On the other hand, online consultation focuses the assistance specifically on an organization’s situation, improving the chances that the information provided will be appropriate to their specific situation. Overall, the rankings provided in the survey suggest that “Websites” are the lowest priority option, reflecting in part the fact that CHIN members already have access to a website of resource material. CHIN regularly conducts surveys to ascertain levels of satisfaction with the CHIN website in general, and with the Professional Exchange site in particular. These surveys have shown a high level of satisfaction among users.

Finally, the concept of an “Online hotline” drew between 16 and 25 votes at each priority ranking, indicating a consistent, but perhaps lukewarm reception. A number of individual comments referred to mentorship arrangements, on-site visits by advisors, coaching, and site assessments, all suggesting an even more individualized relationship between organization and advisor.

Conclusion: While respondents prefer the focused, interactive nature of traditional face-to-face courses, there is clearly a willingness to test other approaches, especially if it will increase the amount of training available across the country.

Appendix A : Digital Preservation Survey Questionnaire

Inventory of Digital Assets

A digital asset is a single computer file, or group of computer files, the content of which is valuable to your organization. Examples include:

- any artefact originally created and acquired in digital form (such as a digital photograph, digital video or computer game);

- any digital copy of an artefact for which your organization does not hold the original (such as a digitized copy of an analogue photograph);

- a digital copy of an artefact, where your organization holds both the original physical artefact (such as a sculpture or a diary) and the copy ( whether created by scanning or photographing an object with a digital camera);

- a copy of the computer file(s) containing your organization’s collections management system; or

- digital material created by your organization which must be maintained for long periods of time, such as audio guides, acquisition files, intellectual property agreements, contracts or correspondence with donors.

1a. Does your organization possess any digital assets?

Yes / No / Don’t know

1b. Does your organization possess any of the following types of digital assets?

(Answer “Yes”, “No”, or “Don’t know” for each of the following types):

- Digital assets which could not be replaced in case of loss. This category would include:

- artefacts created in digital form

- digital works of art

- virtual exhibits

- digital publications

- documents for which no physical original exists

- digitized copies of physical originals which no longer exist

- Digitized copies where the re-digitization process would be difficult, expensive and/or harmful to the original. This category would include digitized copies of original physical objects, such as artefacts, works of art, analogue photographs, publications or documents which form part of your collection.

- Digitized copies which could be re-digitized fairly easily from the same source material in case of loss. This category would include digitized copies of reference materials, such as analogue photographs or microfilm of items in your collection.

- Collections management records

- Other documents related to your collections, which exist only in digital form such as:

- audio guides

- acquisition files

- intellectual property agreements

- contracts

| Physical carrier (year introduced) | No. of physical items | Approx. size in MB | Approx. age (in years) of carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic storage formats | |||

| 7 or 9 track magnetic tape (1952) | |||

| 8” floppy diskette (1972) | |||

| 5.25” floppy diskette (1976) | |||

| 3.5” diskette (1982) | |||

| 8 mm Digital Audio Tape (DAT) cartridge (1987) | |||

| 4 mm Digital Audio Tape (DAT) cartridge (1987) | |||

| Iomega Zip disk - 100 MB (1995) | |||

| Iomega Zip disk - 250 MB (1998) | |||

| Iomega Zip disk - 750 MB (2002) | |||

| LTO (Linear Tape Open) 1 - 100 GB (2000) | |||

| LTO (Linear Tape Open) 2 - 200 GB (2003) | |||

| LTO (Linear Tape Open) 3 - 400 GB (2004) | |||

| LTO (Linear Tape Open) 4 - 800 GB (2007) | |||

| LTO (Linear Tape Open) 5 - 1.5 TB (2010) | |||

| Optical storage formats | |||

| 10 or 12” optical discs (1979) | |||

| 5.25” magneto-optical discs (1985) | |||

| 3.5” magneto-optical discs (1985) | |||

| Kodak Photo-CD system (1992) | |||

| CD-ROM (containing Read-Only content) (1988) | |||

| CD-R (write-once, produced in-house) (1995) | |||

| CD-RW (multiple write, produced in-house) (1997) | |||

| DVD-ROM (containing Read-Only content) (1997) | |||

| DVD-R (write-once, produced in-house) (1997) | |||

| DVD-RW (multiple write, produced in-house) (1999) | |||

| Blu-Ray BD-ROM (containing Read-Only content) (2006) | |||

| Blu-Ray BD-R (write-once, produced in-house) (2006) | |||

| Blu-Ray BD-RE (multiple write, produced in-house (2006) | |||

| Hard disk drives (HDD) | |||

| internal hard drive (1973) | |||

| external hard drive (1998) | |||

| network space – shared | |||

| network space - personal | |||

| Web server | |||

| Flash-based memory | |||

| USB flash drives (such as ThumbDrive (1998), DiskOnKey (2000), jump drive, pen drive, data key) | |||

| Memory cards (such as PC Cards (1991), CompactFlash (1994), SmartMedia (1995), MultiMediaCard (1997), SDCard (2001), miniSD (2003), Memory Stick (2003), microSD (2005) | |||

| Other (please specify) | |||

3a. Please indicate if your organization has the following storage spaces for its digital assets:

- Network server room (for shared drive, personal drive or Web server space controlled by your organization)

- Dedicated vault or storage space

- Regular office space (stored on computer hard drives, or as items stored on shelves)

- Off-site storage (such as a record centre, cloud storage, trusted digital repository, or other type of institutional repository)

| Storage space available? (Y/N) | Regular office environment | Specialized environment (temperature generally in the vicinity of 17°C to 23°C (+/- 2°C) and a relative humidity of 20% to 30% (+/- 5 %) | Don't know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Network server room (for shared drive, personal drive or Web server space controlled by your organization) | ||||

| 2. Dedicated vault or storage space | ||||

| 3. Regular office space (stored on computer hard drives, or as items stored on shelves) | ||||

| 4. Off-site storage (such as a record centre, cloud storage, trusted digital repository, or other type of institutional repository) |

3c. Please identify any other storage spaces your organization uses for its digital assets and indicate of they offer a regular office environment or a specialized environment.

| Digital file format types | Date range files created | Still readable? |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Word Processing (such as .txt, .doc, .docx, .rtf, .wpd, .odf, .lwp, .pdf, .pdf/a) |

|

|

| 2. Email (such as mime, msg, .pst) |

|

|

| 3. Presentation (such as .ppt, .pptx, .shw, .prz) |

|

|

| 4. Spreadsheet (such as .xls, .xlsx, .123, .wk1, .wk2, .qpw) |

|

|

| 5. Still image (such as jpg, jp2, png, tiff, gif, RAW formats, dng) |

|

|

| 6. Audio (such as .wav, .mp3, sma, mpeg-1, mpeg-2, mpeg-4 AAC, aiff, .wma bwf, MIDI) |

|

|

| 7. Video (such as jpeg2000 MXF, Motion JPEG 2000, avi, mpeg-2, mpeg-4, .mov, .wmv) |

|

|

| 8. Markup language (such as sgml, html, xhtml, xml) |

|

|

| 9. Database (such as dbf, fp7, acc, csv, siard) |

|

|

| 10. Statistical data (such as sas, spss, ddi, DExT, sdmx) |

|

|

| 11. Geospatial data (such as CCOGIF, dem, dig-3, E00, SHP, IHO) |

|

|

| 12. Computer Aided Design (CAD) (such as .dxf, .cgm, .xmi) |

|

|

| 13. Source code and/or executable files (such as .exe) |

|

4b. Please list any other digital formats that you use, the approximate date range when the files were created, and whether the files are still readable.

4c. Of the software packages that your organization uses, please identify the three most frequently used.

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. File names selected by the file creator on a case-by-case basis | |||

| 2. Many naming systems, developed on a project-by-project basis | |||

| 3. Consistent and standardized naming system, developed in-house | |||

| 4. Persistent, formal identifier systems (such as ARK, DOI, PURL and XRI) | |||

| 5. Other (please specify) |

5b. Please indicate any other ways that digital file names are constructed within your organization.

6a. Computer files are generally organized in directory and sub-directory structures. Sometimes, the organization of this storage system is left to the file creator; in other cases, the hierarchy of directory and sub-directory names is established by the organization. How are digital files organized in your organization? Check all that apply.

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Database records with digital objects attached or linked | |||

| 2. Data tagged in a mark-up language (such as XML) with digital objects linked | |||

| 3. Other (please specify) |

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Chronological directory structure, based on date of creation of the digital asset | |||

| 2. Directory structure by file format (for example, word processing, images, audio, etc.) | |||

| 3. Directory structure, developed on a project-by-project basis | |||

| 4. Directory structure based on the organization's file classification system | |||

| 5. Other (please specify) |

6b. Please indicate any other ways that digital files are organized in your organization.

7. What security measures are in place to protect the digital assets? Check all that apply.

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. area locked, but accessible to all staff | |||

| 2. area locked and access restricted to approved staff only | |||

| 3. intruder alarm | |||

| 4. other (please specify) |

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. password protection | |||

| 2. firewall | |||

| 3. virus protection | |||

| 4. user access restrictions (profiles) | |||

| 5. other (please specify) |

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. calculation of checksum

A checksum is the result of a mathematical calculation based on the content of a computer file. Any subsequent change in the value of the checksum indicates that the content of the file has been altered. |

|||

| 2. encryption | |||

| 3. other (please specify) |

| Yes | No | Don’t know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. you control circulation of preservation copies outside the storage area

A preservation copy is a computer file(s) in a digital format stored on a physical carrier, which together provide the highest quality, most complete and most reliable version of the digital asset. |

|||

| 2. you allow consultation only through access copies

An access copy is a computer file in a digital format and on a physical carrier which was selected to facilitate access by a researcher. |

|||

| 3. other (please specify) |

1. Digital assets which could not be replaced in case of loss. This category would include:

|

|

|---|---|

| 2. Digitized copies where the re-digitization process would be difficult, expensive and/or harmful to the original. This category would include digitized copies of original physical objects, such as artefacts, works of art, analogue photographs, publications or documents which form part of your collection. |

|

| 3. Digitized copies which could be re-digitized fairly easily from the same source in case of loss. This category would include digitized copies of reference materials, such as analogue photographs or microfilm of items in your collection. |

|

| Preservation measures | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Make backup copies on a regular basis (files made using some type of backup utility, and paired with a restore function). | |||

| 2. Make preservation copies, in addition to or instead of, backup copies. | |||

| 3. Use more than one type and/or brand of physical storage format to protect against format failure. | |||

| 4. Maintain stable storage conditions, allowing only minor variations in temperature and relative humidity (see also Question 3). | |||

| 5. Store preservation copies in two geographically separate storage locations, in case of fire, flood, earthquake, etc. | |||

| 6. Maintain the computer hardware required to read each type of physical carrier storing your digital assets. | |||

| 7. Maintain operating software (O/S) and programs (such as MS Word, or Corel WordPerfect) necessary to read all the file formats represented in your digital assets. | |||

| 8. Inspect preservation copies at regular intervals to verify physical condition. | |||

| 9. Read preservation copies at regular intervals to confirm their continued readability. | |||

| 10. Update the physical carrier to maintain access on current equipment. | |||

| 11. Convert the file format to maintain access using current operating systems and/or software (such as a WordPerfect format (.wpd) to a Portable Document format (.pdf)). | |||

| 12. Other (please specify). |

9b. Please list any other actions your organization takes to protect the digital assets in your collection.

| Yes | No | Don't know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Policy | |||

| 2. Strategy or plan | |||

| 3. Guidelines or procedures |

11. Has your organization ever physically lost, or lost access to, any digital assets?

Yes / No / Don’t know

12. Please provide any additional information about your organization’s digital assets and their preservation needs that were not addressed by the survey.

Identifying Your Organization’s Needs

13a. What does your organization need in order to preserve digital assets? Please rank the options in order of priority from 1 (highest priority) to 7 (lowest priority).

Organizational need - Order of priority (1 to 7)

- Funding

- Infrastructure and equipment

- Organizational capacity

- Standards, guidelines or best practices

- Staff development and training

- Identification by management as a priority

- Technical expertise

13b. Please specify any other digital preservation needs which apply to your organization, but which are not listed above.

| Training capacity | Staff expertise | Written resources | Tools (such as videos, online courses, etc.) | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Copyright | ||||

| 2. Digitization | ||||

| 3. File formats | ||||

| 4. Infrastructure and equipment | ||||

| 5. Organization and identification of files | ||||

| 6. Physical storage formats | ||||

| 7. Preservation strategies and tools | ||||

| 8. Security | ||||

| 9. Standards | ||||

| 10. Storage conditions | ||||

| 11. Sustainable business models |

14b. Please specify any other digital preservation training capacity which exists in your organization, but which is not listed above.

15a. What digital preservation-related skills training would benefit your organization? Please rank the options in order of priority from 1 (highest priority) to 11 lowest priority).

Training needs - Order of priority (1 to 11)

- Copyright

- Digitization

- File formats

- Infrastructure and equipment

- Organization and identification of files

- Physical storage formats

- Preservation strategies and tools

- Security

- Standards

- Storage conditions

- Sustainable business models

15b. Please specify any other digital preservation training needs which would benefit your organization, but which are not listed above.

16a. Identify your preferred delivery methods for training. Please rank the options from 1 (highest priority) to 6 (lowest priority).

Training method - Order of priority (1 to 6)

- Half-day in-person course

- Full-day in-person course

- Online webinar

- Online self-paced course

- Website

- Ongoing online service to answer your digital preservation questions

16b. Please specify any other training delivery methods which would be appropriate for your organization, but which are not listed above.

17. Please provide any additional information about your organization’s digital training needs that were not addressed by the survey.

Organizational Profile

18. In which province or territory are you located?

- Alberta

- British Columbia

- Manitoba

- New Brunswick

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- Northwest Territories

- Nova Scotia

- Nunavut

- Ontario

- Prince Edward Island

- Quebec

- Saskatchewan

- Yukon

19. What is your organization’s current annual operating budget? Please provide your best estimate.

- $0 - $4,999

- $5,000 - $24,999

- $25,000 - $49,999

- $50,000 - $99,999

- $100,000 - $199,999

- $200,000 - $399,999

- $400,000 - $699,999

- $700,000 - $999,999

- $1,000,000 - $1,499,999

- $1,500,000 - $1,999,999

- $2,000,000 - $2,999,999

- $3,000,000 - $3,999,999

- Over $4,000,000

- Don’t know

Name of organization (optional):

Alternate Text For Graphs and Diagrams

Figure 1

| Province | Survey Participation by Province |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 14 |

| British Columbia | 25 |

| Manitoba | 9 |

| New Brunswick | 11 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6 |

| Nova Scotia | 10 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 |

| Nunavut | 2 |

| Ontario | 32 |

| Prince Edward Is. | 2 |

| Québec | 26 |

| Saskatchewan | 7 |

| Yukon | 4 |

Figure 2

| Budget ($) | % of Organizations in Each Budget Category |

|---|---|

| 0 – 4,999 | 3.3 |

| 5,000 – 24,999 | 5.2 |

| 25,000 – 49,999 | 5.5 |

| 50,000 – 99,999 | 3.3 |

| 100,000 – 199,999 | 6.8 |

| 200,000 – 299,999 | 4.9 |

| 300,000 – 399,999 | 0.3 |

| 400,000 – 699,999 | 3.6 |

| 700,000 – 999,999 | 2.9 |

| 1,000,000 – 1,499,999 | 2.3 |

| 1,500,000 – 1,999,999 | 0.6 |

| 2,000,000 – 2,999,999 | 1 |

| 3,000,000 – 3,999,999 | 0.3 |

| over 4,000,000 | 4.9 |

| Don't know | 2.6 |

Figure 3

| Response | Number of Organizations |

|---|---|

| Yes | 277 |

| No | 24 |

| Don't Know | 6 |

Figure 4

| Digital Asset Type | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Could not be replaced | 157 | 6 |

| Difficult to replace | 166 | 8 |

| Could be re-digitized | 213 | 5 |

| Collections management | 218 | 5 |

| Other | 140 | 8 |

Figure 5

| Response | % |

|---|---|

| Yes (lost) | 37 |

| No | 46 |

| Don't know | 17 |

Figure 6

| Storage Space | Number of Organizations |

|---|---|

| Server room | 81 |

| Vault | 58 |

| Office space | 139 |

| Off-site | 62 |

| Other | 25 |

Figure 7

| Type of Physical Carrier | Number of Physical Carriers |

|---|---|

| 7 or 9 track tape | 418 |

| 8" diskette | 28 |

| 5 1/4" diskette | 118 |

Figure 8

| Type of Physical Carrier | Number of Physical Carriers |

|---|---|

| 5 1/4" diskette | 118 |

| 3 1/2" diskette | 2,053 |

| 4 mm/8 mm DAT | 2,310 |

| Kodak-CD | 12,361 |

| CD/DVD | 36,000 |

| LTO 1/5 | 292 |

| External hard drive | 27,945 |

Figure 9

| Digital Asset Category | Number of Organizations |

|---|---|

| Word processing | 270 |

| 174 | |

| Presentation | 126 |

| Spreadsheet | 207 |

| Still image | 300 |

| Audio | 149 |

| Video | 151 |

| Database | 184 |

| Mark-up language | 51 |

| Statistical data | 21 |

| Geospatial data | 16 |

| Computer-assisted design | 32 |

| Source code | 33 |

Figure 10

| Type of Digital Asset | Irreplaceable | Difficult to replace | Easy to replace | Collections Management | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word processing | 57 | 44 | 62 | 65 | 42 |

| 51 | 24 | 36 | 36 | 27 | |

| Presentation | 43 | 24 | 29 | 17 | 13 |

| Spreadsheet | 54 | 36 | 40 | 55 | 22 |

| Still image | 74 | 72 | 73 | 59 | 22 |

| Audio | 52 | 33 | 34 | 17 | 13 |

| Video | 49 | 36 | 34 | 19 | 13 |

| Database | 44 | 30 | 29 | 69 | 12 |

| Mark-up language | 16 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 8 |

| Statistical data | 7 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Geospatial data | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Computer-assisted design | 9 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| Source code | 11 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

Figure 11

| How Digital File Names Are Constructed | Naming systems in use | None | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creator, case-by-case | 123 | 5 | 5 |

| Project-by-project | 71 | 32 | 10 |

| In-house standardization | 53 | 55 | 6 |

| Persistent ID system | 3 | 70 | 23 |

Figure 12

| How Digital Files Are Organized | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project-by-project | 73 | 16 | 13 |

| Classification system | 49 | 39 | 17 |

| Chronological | 43 | 42 | 16 |

| File format/type | 35 | 50 | 15 |

Figure 13

| How Digital Files Are Organized | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database + objects | 87 | 14 | 13 |

| Data mark-up + objects | 19 | 44 | 34 |

Figure 14

| Security Measure | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locked; accessible to all staff | 64 | 33 | 2 |

| Locked; restricted to approved staff | 64 | 39 | 3 |

| Intruder alarm | 57 | 42 | 6 |

Figure 15

| Security Measure | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Password protection | 96 | 17 | 3 |

| Firewall | 98 | 6 | 8 |

| Virus protection | 105 | 2 | 4 |

| User access restrictions (profiles) | 79 | 20 | 8 |

Figure 16

| Security Measure | Yes | No | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Checksum | 4 | 57 | 42 |

| Encryption | 9 | 56 | 37 |

| Preservation copies | 70 | 28 | 14 |

| Access copies | 54 | 36 | 18 |

Figure 17

| Type of Digital Asset | All | Most | Some | None | Don't know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irreplaceable assets | 43 | 35 | 16 | 6 | 17 |

| Difficult to replace assets | 44 | 31 | 21 | 6 | 14 |

| Easy to replace assets | 50 | 37 | 16 | 3 | 11 |

Figure 18

| Type of Digital Asset | All | Most | Some | None | Don't know | Didn't specify |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irreplaceable assets | 43 | 35 | 16 | 6 | 17 | 190 |

| Difficult to replace assets | 44 | 31 | 21 | 6 | 14 | 191 |