Evaluation of the Grant to Quebec

Research and Evaluation Branch

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

January 2020

Ci4-88/2020E-PDF

978-0-660-34224-5

Ref. No.: E2-2018

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Evaluation of the Quebec Grant ‒ Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Profile of permanent residents in Quebec and the rest of Canada

- 4. Key Findings

- 4.1 Social integration

- 4.2 Economic integration

- 4.3 Interprovincial mobility

- 4.4 Comparison of services

- 4.5 Languages of service

- 4.6 Data collection for the comparative studies

- 4.7 Usefulness of the comparative studies

- 4.8 Management of the Grant

- 4.9 Level of funding in Quebec and the rest of Canada

- 5. Conclusions and recommendation

- Appendix A: Description of available IRCC databases

- Appendix B: Economic performance of newcomers from Quebec and the rest of Canada according to their knowledge of official languages in 2016

List of tables

- Table 1:

- Amounts provided by the Government of Canada for the funding of settlement services in Quebec and the rest of Canada (in million $), fiscal years 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

- Table 2:

- Permanent residents admitted to Canada (all immigration categories) by province and territory, calendar years 2013 to 2018

- Table 3:

- Net interprovincial mobility for newcomers destined to Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec between 2006 and 2015, by knowledge of official languages, 2016 taxation year

- Table 4:

- Dissimilarities between settlement and language training services in Quebec and the rest of Canada

- Table 5a:

- Transfer payments and operating costs for Quebec and the rest of Canada, 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

- Table 5b:

- Number of permanent residents admitted to Quebec and the rest of Canada, 2013-2017

- Table 6:

- Incidence of employment income at one, five and 10 years since admission

- Table 7:

- Median income at one, five and 10 years since admission

- Table 8:

- Proportion of social assistance recipients at one, five and 10 years since admission

List of figures

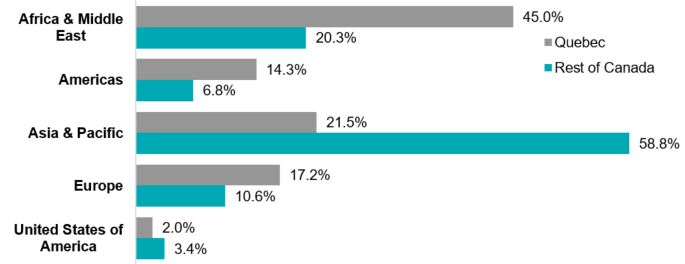

- Figure 1:

- Percentage of total permanent residents from the rest of Canada and Quebec (all immigration categories combined) by region of origin, calendar year 2013 to 2018

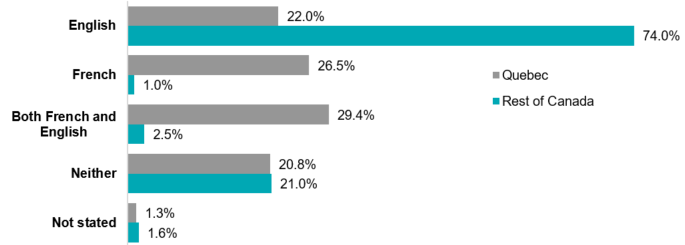

- Figure 2:

- Percentage of permanent residents (all immigration categories) with knowledge of official languages in the rest of Canada and Quebec, calendar years 2013 to 2018

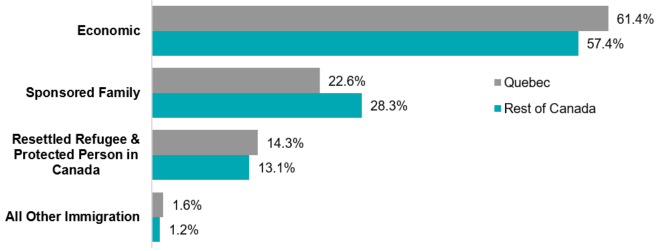

- Figure 3:

- Percentage of permanent residents by immigration category in the rest of Canada and Quebec, calendar years 2013 to 2018

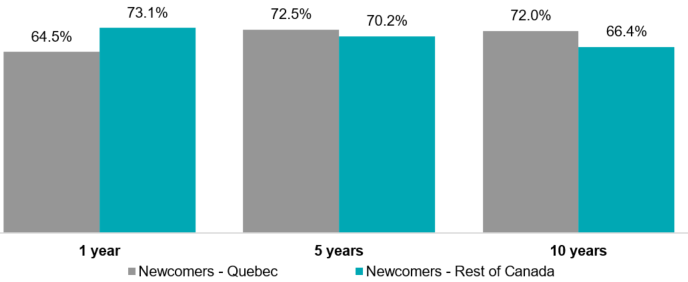

- Figure 4:

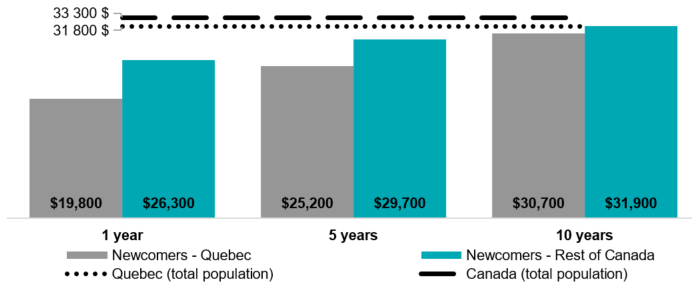

- Incidence of employment earnings of newcomers (all immigration categories combined) to Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission

- Figure 5:

- Median earnings of newcomers in Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission, compared with the median earnings of the total population of Canada and Quebec

- Figure 6:

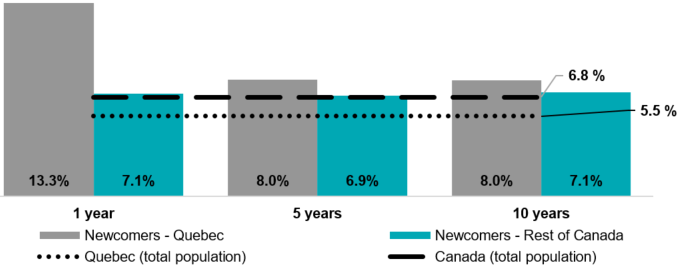

- Proportion of social assistance recipients among newcomers in Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission

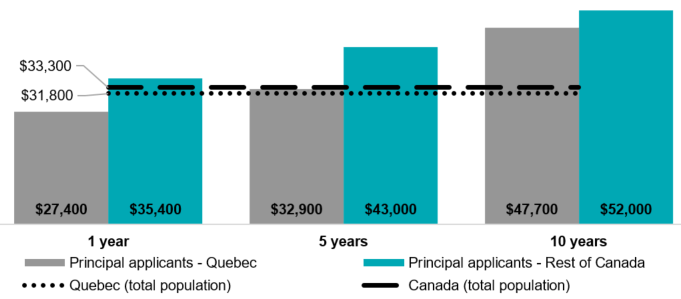

- Figure 7:

- Median earnings among principal economic applicants in Quebec and in the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and ten years since admission

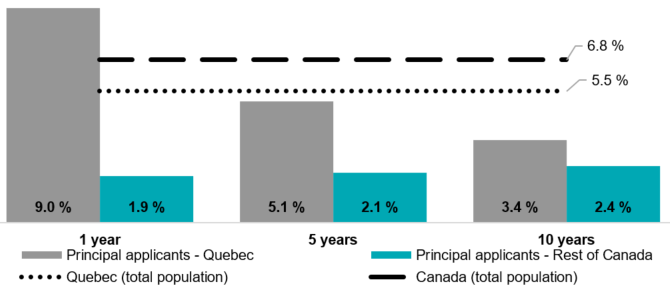

- Figure 8:

- Proportion of social assistance recipients among principal economic applicants in Quebec and in the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and ten years since admission

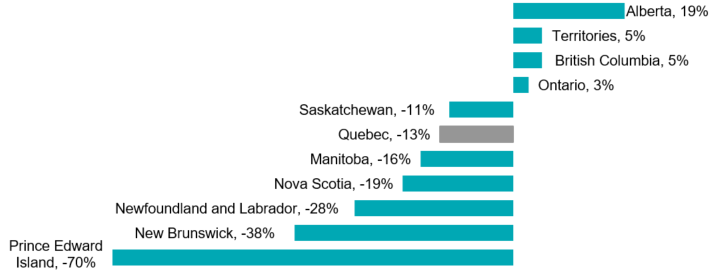

- Figure 9:

- Net gains and losses due to interprovincial mobility by province, 2016 taxation year

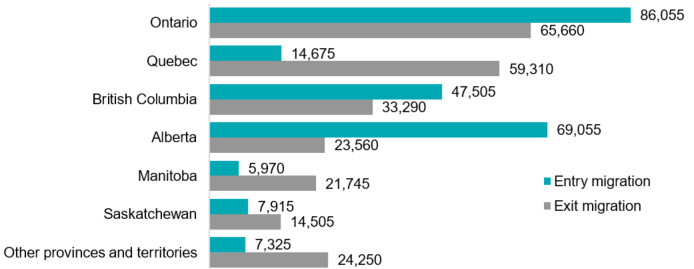

- Figure 10:

- Interprovincial mobility of newcomers admitted between 2006 and 2015, 2016 taxation year

- Figure 11:

- Percentage of newcomers accessing an IRCC-funded service in 2018 by number of years since admission

- Figure 12:

- Amount of funding per permanent resident admitted to Quebec and the rest of Canada, 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

List of acronyms

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- FMC

- Francophone Minority Community

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- MIDI

- Ministère de l’Immigration, de la Diversité et de l’Inclusion

- MIFI

- Ministère de l’Immigration, de la Francisation et de l’Intégration

- SAP

- Enterprise Resource Planning

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- FOSS

- Field Operations Support System

- AGQ

- Auditor General of Quebec

Executive summary

Purpose of the evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of the Grant to Quebec. This evaluation was conducted as per the Treasury Board Policy on Results and as required under section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act. It included fiscal years 2012-2013 to 2017-2018.

The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the extent to which the settlement services supported by the Grant are available to all permanent residents in the province of Quebec and correspond to those available in the rest of Canada.

Overview of the Canada-Quebec Accord and the Grant

The evaluation focused on the administration of the Grant and the services it supports, not on the Canada-Quebec Accord. The Grant is strictly designed to cover the delivery and administration of reception and integration services provided by Quebec. As a result, Canada provides Quebec with funding in the form of a grant to offset the costs associated with the reception and integration services provided by the province. Under section 26 of the Accord, the Grant will be provided as long as the reception and integration services offered by Quebec:

- correspond, when considered in their entirety, to those offered by Canada in the rest of the country; and

- are provided without discrimination to all permanent residents in the province, whether or not they were selected by Quebec.

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, the evaluation found that the reception and integration services provided to newcomers in Quebec generally met the Grant conditions during the period covered by the evaluation, particularly with regards to their:

- correspondence to services offered in the rest of Canada, and

- eligibility, i.e., permanent residents have access to the services whether or not they were selected by Quebec.

However, those conditions are not clearly defined, and there is a lack of common criteria and information needed for a more precise analysis of the extent to which the conditions have been met.

Comparison of services

In general, the evaluation found that the types of reception and integration services in Quebec are generally similar to those offered in the rest of Canada. In addition, the evaluation confirmed that these services are also available to permanent residents who were not selected by the province of Quebec. However, there are several important differences in the way these services are delivered, including the eligibility for services. In particular, the duration of eligibility is shorter in Quebec than in the rest of Canada, which could lead to inequality of access for newcomers who decide to reside in Quebec.

Comparative studies

Furthermore, although the comparative studies carried out by the Joint Committee meet the minimum requirements of the Accord, these requirements are not clearly defined. In addition, the information presented in the studies by the two governments is not consistent, and the information collected on the types of services offered lacks some essential elements, such as the language of services and the quality of the services provided.

This lack of consistency is due to the absence of a framework of common indicators allowing a clear and systematic comparison of services and the development of more rigorous conclusions. Improved indicators and data would allow for more in-depth analysis in the comparative studies, as well as the systematic evaluation of services provided in both jurisdictions in relation to requirements (a) and (b) of the Accord.

Recommendation: IRCC should explore a new methodological approach to make the collection of and access to data on the comparability of settlement services more rigorous, consistent and useful for the comparative studies.

Evaluation of the Quebec Grant ‒ Management Response and Action Plan

Although the comparative studies carried out by the Joint Committee meet the minimum requirements of the Accord, these requirements are not clearly defined. In addition, the information presented in the studies by the two governments is not consistent, and the information collected on the types of services offered lacks some essential elements, such as the languages of services and the quality of the services provided.

This lack of consistency is due to the absence of a framework of common indicators that would allow a clear and systematic comparison of services and the development of more rigorous conclusions. Improved indicators and data would allow for more in-depth analysis in comparative studies, and would make it possible to systematically evaluate the services offered in both jurisdictions in relation to requirements (a) and (b) of the Accord.

Recommendation

IRCC should explore a new methodological approach to make the collection of and access to data on the comparability of settlement services more rigorous, consistent and useful for the comparative studies

Response

IRCC partially agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC wishes to point out that the comparison of services between Canada and Quebec is consistent with the requirements of the Accord: "...to review, at least once a year, the reception and integration services offered by Canada and Quebec" (Appendix "A", sec. II, 3(g)). That being said, the comparison remains useful and relevant for both jurisdictions in order to meet the objectives set out in the Accord.

However, IRCC agrees that the Accord does not specify the methodology for comparing services and is committed to consulting with the MIFI to make the results more comparable.

In the area of settlement, IRCC will continue to collaborate with the MIFI through other established information sharing mechanisms, including the FPT Settlement Working Group (SWG), the National Settlement and Integration Council (NSIC) and the FPT Language Forum (LF). This ongoing collaboration is also expected to better support both organizations in the development and implementation of settlement and integration services for newcomers.

Actions

- Explore with the MIFI a new methodological approach to improve the comparability of settlement services in the two jurisdictions.

- Lead: Settlement and Integration Policy (SIP) Branch.

- Completion date: Q4 2019/20

- Develop an analytical framework, with common indicators, to be used by the working group for comparative studies.

- Lead: SIP Branch

- Support: Research and Evaluation (RE) Branch

- Completion date: Q3 2020/21

- Submit the framework for the comparative studies analysis to the Assistant Deputy Ministers (ADMs) for approval at the teleconference meeting of the Canada-Quebec Accord Joint Committee.

- Lead: Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy and Program

- Completion date: Q3 2020/21

- Complete the comparative study using the new methodology and analysis framework.

- Lead: SIP Branch

- Support: RE Branch

- Completion date: Q3 2021/22

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose of the evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of the Grant to Quebec. This evaluation was conducted as per the Treasury Board Policy on Results and as required under section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the extent to which the settlement services supported by the Grant are available to all permanent residents in the province of Quebec and correspond to those available in the rest of Canada. The evaluation also assessed the management and resources in place to facilitate the administration of the GrantFootnote 1.

1.2 Scope of the Evaluation

This report covers the period since the last evaluation, i.e. from 2012-2013 to 2017-2018. The evaluation focuses on the administration of the Grant and the services it supports, not on the Canada-Quebec Accord. While the Accord sets out the authorities and responsibilities of the province and the federal government regarding the number of newcomers destined for Quebec, as well as the selection, reception and integration of these newcomers, the Grant is strictly designed to cover the delivery and administration of reception and integration services provided by Quebec.

1.3 Overview of the Canada-Quebec Accord and of the Grant

The Canada-Quebec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens (the Accord) was signed on February 5, 1991, and came into force on April 1, 1991.

The Accord sets out two objectives for Quebec: to preserve Quebec’s demographic weight within Canada, and to ensure that newcomers to the province are integrated in a manner that respects the province’s distinct identity.

The Accord gives Quebec exclusive responsibility for the selection, reception and integration of newcomers. Canada also transfers to Quebec the power to administer settlement and resettlement services for newcomers.

However, national immigration requirements and objectives as well as the admission of newcomers remain under federal government jurisdiction.

As a result, Canada provides Quebec with funding in the form of a grant to offset the costs associated with the reception and integration services provided by the province. The amount of the Grant is calculated on an annual basis using a formula set out in Appendix B of the Accord. The Accord stipulates that two conditions must be met in order for the funds to be allocated. The conditions of section 26 of the Accord specify that the Grant will be allocated, provided that the reception and integration services offered by Quebec:

- when considered in their entirety, correspond to the services offered by Canada in the rest of the country; and

- are provided without discrimination to all permanent residents in the province, whether or not they were selected by Quebec.

While the Accord gives Quebec responsibility for providing settlement services to newcomers, the province has an ongoing relationship with IRCC on a variety of issues related to integration and immigration. As a result of the Accord, two bilateral committees were set up to structure the relationship between IRCC and the province:

- Joint Committee: This committee is mandated to promote the harmonization of the economic, demographic and socio-cultural objectives of the two parties in the area of immigration and integration, as well as to coordinate the implementation of the policies of Canada and Quebec related to these objectivesFootnote 2.

- Implementation Committee: This committee has a general mandate to coordinate the implementation of the Accord and to develop the related operational terms and conditions. The Implementation Committee works under the direction of the Joint Committee, which may give it any specific terms of reference it deems appropriateFootnote 3.

1.4 Overview of funding in Quebec and the rest of Canada

The funding formula used to determine funding to the Province of Quebec was negotiated at the time the Accord was drafted in 1991.

The Accord has two formulas. The formula used historically to calculate the amount of the grant varies according to the proportion of non-Francophone newcomers to QuebecFootnote 4. The calculation of the Grant amount awarded to Quebec is done in the fall and is conducted by the Financial Management Branch of IRCC.

For purposes of comparison, the formulas used and the amounts provided by the Government of Canada for the Grant to Quebec and for settlement funding in the rest of Canada are presented below.

Quebec

The formula used historically takes into account the following two conditions in calculating the escalation factor:

- The year over year difference in the number of non-Francophone immigrants to Quebec, plus

- The year over year difference in total federal government expenditures less debt-servicing charges (net federal expenditures)

The result of the calculation is multiplied by the amount of funds paid in the previous year.

Rest of Canada

Settlement funding is determined by the national settlement funding formula, which is based on the following:

- The number of newcomers in each province and territory.

- A weighting factor for the number of refugees.

- Additional amounts are provided for capacity-building.

| 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 319.9 | 340.5 | 345.1 | 378.2 | 490.3 |

| Rest of Canada | 650.8 | 669.6 | 761.9 | 842.4 | 844.5 |

Note: Amounts in the rest of Canada include transfer payments and operating costs for the Settlement Program and the Resettlement Assistance Program.

Note: Data for fiscal year 2018-2019 were not available at the time of writing of the final report.

Source: SAP

2. Methodology

2.1 Evaluation questions

The questions for this evaluation focused on performance. To what extent:

- do the services provided by Quebec correspond to the services offered by the Government of Canada in the rest of the country?

- are the services provided by Quebec offered to all permanent residents of Quebec, whether or not they were selected by the province?

- is the information provided by Quebec useful, and to what extent does this information help IRCC meet its accountability requirements in relation to the Grant? and

- do the management mechanisms and resources in place provide effective support for the administration of the Grant?

2.2 Data collection methods

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation were conducted between August 2018 and January 2019, and included multiple lines of evidence, listed below:

- Interviews with IRCC staff (n=9) and partners (n=9);

- Document review (e.g., annual reports of the Ministère de l’Immigration, de la Diversité et de l’Inclusion (MIDI);Footnote 5 annual report of the Auditor General of Quebec (VGQ) to the National Assembly (2017-2018), comparative studies of reception and linguistic, cultural and economic integration services, terms and conditions of MIDI programs, and terms and conditions of the IRCC Settlement Program);

- Review of administrative data (e.g., data from the Global Case Management System (GCMS); the Immigration Longitudinal Database (IMDB); and the Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE));Footnote 6

- Review of financial data (SAP); and

- IRCC Settlement Program 2018 Client and Non-Client Survey ResultsFootnote 7. The surveys were sent to all newcomers admitted to Canada in 2011, 2013, 2015 and 2017. The survey questions focused on newcomers’ settlement experience, including their knowledge of official languages, their economic activities in Canada and their community participation.

2.3 Limitations and considerations

In preparation for this evaluation, a letter was sent to representatives of the MIDI and the VGQ to inform them of the evaluation. The purpose of the letter was to solicit their participation in the interviews and to share relevant documentation for a more balanced analysis. Provincial representatives declined to participate in the study. IRCC used only publicly available documents to conduct this evaluation, and no interviews were conducted with any representatives from the government of Quebec.

It should be noted that under the Accord, Quebec is not required to report to the federal government on the use of funds. And since the federal government does not deliver services in Quebec, IRCC does not interact with service providers in the province. To mitigate this lack of direct contact, an interview was conducted and information shared with a representative of an umbrella organization comprised of organizations working with newcomers in Quebec.

While the methodology had some limitations, as described above, the information generated from the available data was sufficient to ensure that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.

3. Profile of permanent residents in Quebec and the rest of Canada

For comparison purposes, the analysis uses data from the GCMS to develop a profile of permanent residents in Quebec and the rest of Canada. The period covered by the data analysis is 2013 to 2018.

3.1 Intended province or territory of destination

Between 2013 and 2018, Quebec was the intended destination for a total of 307,976 newcomers admitted to Canada. This is about 18% of all newcomers admitted to Canada during that period. However, the proportion of newcomers to Quebec decreased from 20% in 2013 to 16% in 2018.

| Province and territories | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.6% |

| Nova Scotia | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.9% | 1.4% |

| New Brunswick | 0.8% | 1.1% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.2% |

| Quebec | 20.1% | 19.3% | 18.0% | 18.0% | 18.3% | 15.9% | 18.3% |

| Ontario | 40.0% | 36.8% | 38.1% | 37.1% | 39.1% | 42.8% | 39.0% |

| Manitoba | 5.1% | 6.2% | 5.5% | 5.7% | 5.1% | 4.7% | 5.4% |

| Saskatchewan | 4.1% | 4.5% | 4.6% | 5.0% | 5.1% | 4.8% | 4.7% |

| Alberta | 14.1% | 16.3% | 17.4% | 16.6% | 14.7% | 13.1% | 15.4% |

| British Columbia | 14.0% | 13.5% | 13.1% | 12.8% | 13.4% | 14.0% | 13.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Nunavut | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Yukon | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Total number of permanent residents admitted | 259,040 | 260,306 | 271,836 | 296,367 | 286,489 | 321,121 | 282,527 |

Source: GCMS (December 31, 2018)

3.2 Regions of origin

During the 2013–2018 period, the regions of origin of permanent residents varied according to their intended destination in Canada. Of these regions of origin, French-speaking countries figure prominently as the home countries of immigrants to Quebec. As indicated in Figure 1, nearly half of newcomers (45%) to Quebec are from African or Middle Eastern countries, while 59% of those whose intended destination was elsewhere in the rest of Canada were mainly from countries in Asia and the Pacific.

Overall, the number of permanent residents from countries in Asia and the Pacific is increasing (62%), while the number of those from the Americas is decreasing (45%).

Text version: Percentage of total permanent residents from the rest of Canada and Quebec (all immigration categories combined) by region of origin, calendar year 2013 to 2018

| Country of Citizenship | Rest of Canada | Quebec |

|---|---|---|

| Africa & Middle East | 20.3% | 45.0% |

| Americas | 6.8% | 14.3% |

| Asia & Pacific | 58.8% | 21.5% |

| Europe | 10.6% | 17.2% |

| United States of America | 3.4% | 2.0% |

Source: GCMS (December 31, 2018)

3.3 Knowledge of official languages

During the 2013–2018 period, the majority of newcomers whose intended destination was elsewhere in Canada (74%) had a knowledge of English only at the time of admission. In Quebec, almost one-third of newcomers (29%) had a knowledge of both official languages, and more than one quarter (27%) had a knowledge of French only (Figure 2).

In Quebec, the number of permanent residents with knowledge of English increased by 69%, while decreases were noted for those with knowledge of French (-28%) and those with knowledge of both official languages (-23%).

Text version: Percentage of permanent residents (all immigration categories) with knowledge of official languages in the rest of Canada and Quebec, calendar years 2013 to 2018

| Official Language Spoken | Rest of Canada | Quebec |

|---|---|---|

| English | 74.0% | 22.0% |

| French | 1.0% | 26.5% |

| Both French and English | 2.5% | 29.4% |

| Neither | 21.0% | 20.8% |

| Not stated | 1.6% | 1.3% |

Source: GCMS (December 31, 2018)

3.4 Immigration categories

From 2013 to 2018, economic immigrants accounted for 61% of all immigrants to Quebec and 57% of those whose intended destination was elsewhere in Canada. Proportionally, the rest of Canada accepted slightly more newcomers sponsored under the family class than Quebec (28% vs. 23%) during the same period; however, the proportion of resettled refugees and protected persons is similar in Quebec and the rest of Canada (Figure 3).

In Quebec, the number of economic immigrants decreased by 16% between 2013 and 2018, while the number of resettled refugees and protected persons doubled. In the rest of Canada, there was a 39% increase in the number of economic immigrants and an 85% increase in the number of resettled refugees and protected persons.

Text version: Percentage of permanent residents by immigration category in the rest of Canada and Quebec, calendar years 2013 to 2018

| Main Category | Rest of Canada | Quebec |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | 57.4% | 61.4% |

| Sponsored Family | 28.3% | 22.6% |

| Resettled Refugee & Protected Person in Canada | 13.1% | 14.3% |

| All Other Immigration | 1.2% | 1.6% |

Source: GCMS (December 31, 2018)

4. Key Findings

4.1 Social integration

Finding #1: In both Quebec and the rest of Canada, the newcomers surveyed had positive views about their inclusion and participation in the community. However, the percentages for volunteering and community participation were lower among newcomers in Quebec.

To examine the inclusion and participation of newcomers in their communities, the evaluation used the results of the most recent survey of Settlement Program clients and non-clients.

It should be noted that the evaluation was not able to link the survey results to clients who accessed IRCC- or MIDI-funded services. Therefore, the results cannot be attributed to services funded by both jurisdictions.

The results of this survey showed that:

- Welcoming community: 89% of Quebec respondents believed that their community was welcoming to newcomers. The results were similar in the rest of Canada.

- Sense of belonging: In Quebec, 89% of respondents said they had a sense of belonging to Canada. The results were similar in the rest of Canada.

- Volunteering: 25% of respondents in Quebec said that they had volunteered with an organization. The results were higher in the rest of Canada, where 34% of respondents volunteeredFootnote 8.

- Community participation: In 2018, 42% of respondents in Quebec said that they were members of a group, organization or association, while in the rest of Canada, the proportion was 51%Footnote 9.

4.2 Economic integration

Finding #2: Based on median earnings and the proportion of newcomers receiving social assistance, the economic performance of newcomers in Quebec was lower than that of newcomers in the rest of Canada, but their performance improved over time.

In order to study the economic outcomes of newcomers in Quebec and the rest of Canada, the evaluation conducted an analysis using IMDB data. The analysis examined the incidence of employment earnings, median earnings and the incidence of social assistance, using data on newcomers (all immigration categories) who were admitted in Canada between 2006 and 2015 and who filed a tax return in 2016.

The results of the analysis are presented in the following subsectionsFootnote 10.

4.2.1 Economic integration of newcomers (all immigration categories combined)Footnote 11

Incidence of employment earningsFootnote 12

As shown in Figure 4, one year after admission in Canada, the incidence of employment earnings among newcomers was higher in the rest of Canada, compared to Quebec. After 5 and 10 years, however, the trend was the opposite, and the incidence of employment earnings was slightly higher among newcomers in Quebec.

Text version: Incidence of employment earnings of newcomers (all immigration categories combined) to Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newcomers - Quebec | 64.5% | 72.5% | 72.0% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 73.1% | 70.2% | 66.4% |

Source: IMDB (2016)

Median earnings

During the first five years in Canada, the median earnings were lower for newcomers in Quebec than for newcomers in the rest of Canada (See Figure 5). Median earnings of Quebec’s immigrant population were also lower than the median earnings of the total populations of Quebec ($31,800) and Canada ($33,300); however, the income gap narrowed over time.

Text version: Median earnings of newcomers in Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission, compared with the median earnings of the total population of Canada and Quebec

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newcomers - Quebec | $19,800 | $25,200 | $30,700 |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | $26,300 | $29,700 | $31,900 |

| Canada (average population) | $33,300 | $33,300 | $33,300 |

| Quebec (average population) | $31,800 | $31,800 | $31,800 |

Source: IMDB (2016) and StatCan – Canadian Income Survey (2016)

Proportion of social assistance recipients

As shown in Figure 6 below, the proportion of social assistance recipients was higher among newcomers in Quebec than in the rest of Canada (all immigration categories combined), mainly during the first five years in the country. The proportion of social assistance recipients in Quebec’s newcomer population was also lower than the proportions in the total populations of Quebec (5.5%) and Canada (6.8%); however, the proportion decreased over time. The difference in the first year was due in part to a higher percentage of sponsored newcomersFootnote 13 under the family class in the rest of Canada (28%), compared to Quebec (23%).

Text version: Proportion of social assistance recipients among newcomers in Quebec and the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and 10 years since admission

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newcomers - Quebec | 13.3 % | 8.0 % | 8.0 % |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 7.1 % | 6.9 % | 7.1 % |

| Canada (average population) | 6.8 % | 6.8 % | 6.8 % |

| Quebec (average population) | 5.5 % | 5.5 % | 5.5 % |

Source: IMDB (2016) and StatCan – Canadian Income Survey (2016)

4.2.2 Economic integration according to official languages (all immigration categories combined)

IMDB data were analyzed to compare the economic outcomes of newcomers (all immigration categories combined) according to their knowledge of official languages at the time of admission to Canada. The analysis included the following three elements:

- Incidence of employment earnings: After 10 years, the gap in the incidence of employment earnings was virtually non-existent among newcomers, regardless of their language profile.

- Median earnings: In Quebec, as in the rest of Canada, earnings were higher for newcomers with knowledge of both official languages.

- Proportion of social assistance recipients: Bilingual newcomers in the rest of Canada, as well as in Quebec, made less use of social assistance than newcomers from other language groups.

The analysis of the data is presented in Appendix B.

4.2.3 Economic integration of economic newcomers (principal applicants)

Median earnings

Specifically in terms of economic immigration, data shows that there is a gap in median earnings between principal applicants destined to Quebec and those destined elsewhere in Canada (see Figure 7). It should be noted that in the first year, principal applicants in the rest of Canada had median incomes that were higher than the median for the Canadian population as a whole. In Quebec, it was in the fifth year that principal applicants had a median income that was higher than the median for the Quebec population.

Text version: Median earnings among principal economic applicants in Quebec and in the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and ten years since admission

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal applicants - Quebec | $27,400 | $32,900 | $47,700 |

| Principal applicants - Rest of Canada | $35,400 | $43,000 | $52,000 |

| Canada (average population) | $33,300 | $33,300 | $33,300 |

| Quebec (average population) | $31,800 | $31,800 | $31,800 |

Source: IMDB (2016) and StatCan – Canadian Income Survey (2016)

Proportion of social assistance recipients

As shown in Figure 8 below, the proportion of social assistance recipients was higher among principal applicants in Quebec than in the rest of Canada, especially during the first five years in the country. For principal applicants in the rest of Canada, the proportion of social assistance recipients was stable and below the Canadian average.

Text version: Proportion of social assistance recipients among principal economic applicants in Quebec and in the rest of Canada in 2016 at one, five and ten years since admission

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal applicants - Quebec | 9.0 % | 5.1 % | 3.4 % |

| Principal applicants - Rest of Canada | 1.9 % | 2.1 % | 2.4 % |

| Canada (average population) | 6.8 % | 6.8 % | 6.8 % |

| Quebec (average population) | 5.5 % | 5.5 % | 5.5 % |

Source: IMDB (2016) and StatCan – Canadian Income Survey (2016)

4.3 Interprovincial mobility

Finding #3: Quebec had a high retention rate, compared with other provinces. However, there was a net loss from interprovincial mobility to other provinces, particularly to Ontario.

In order to better understand retention in Quebec and in the rest of Canada, the evaluation conducted an analysis of interprovincial mobility of newcomers (all immigration categories combined) who were admitted to Canada between 2006 and 2015, and filed a tax return in 2016. The analysis focused on newcomers who arrived in Canada during this period and who filed a tax return in 2016 in a province other than their original province of destination.

In 2016, Quebec ranked fourth in terms of its retention rate (83.1%)Footnote 14.

- Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia had higher retention rates: 91.4%, 89.9% and 88.2%, respectively.

- The Atlantic Provinces had the lowest retention rates at 25.2% in Prince Edward Island, 50.5% in New Brunswick, 52.2% in Newfoundland and Labrador, and 62.8% in Nova Scotia.

As shown in Figure 9, many provinces lost newcomers during the 2006–2015 period. Almost all provinces, with the exception of Alberta, the Territories, British Columbia and Ontario, had a net loss resulting from interprovincial mobility. Quebec’s net loss from interprovincial mobility was 13% during this period.

Text version: Net gains and losses due to interprovincial mobility by province, 2016 taxation year

| Province | +/- Migration |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 19% |

| Territories | 5% |

| British Columbia | 5% |

| Ontario | 3% |

| Saskatchewan | -11% |

| Quebec | -13% |

| Manitoba | -16% |

| Nova Scotia | -19% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | -28% |

| New Brunswick | -38% |

| Prince Edward Island | -70% |

Source: IMDB (2016)

Data shows that, between 2006 and 2015, out-migration from Quebec was more than 59,000 and in-migration was nearly 15,000 (see Figure 10), placing the province second in terms of out-migration and fourth in terms of in-migration.

More than half (57%) of the newcomers admitted to Canada and destined for Quebec who moved during this period did so to Ontario in 2016. In addition, 28% moved to British Columbia and 19% to Alberta.

Text version: Interprovincial mobility of newcomers admitted between 2006 and 2015, 2016 taxation year

| Provinces | Exit migration | Entry migration |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 65,660 | 86,055 |

| Quebec | 59,310 | 14,675 |

| British Columbia | 33,290 | 47,505 |

| Alberta | 23,560 | 69,055 |

| Manitoba | 21,745 | 5,970 |

| Saskatchewan | 14,505 | 7,915 |

| Other provinces and territories | 24,250 | 7,325 |

Source: IMDB (2016)

The interprovincial mobility of newcomers was also analyzed according to their knowledge of official languages at the time of admission to Quebec. The data showed that Quebec posted a net loss for each language group, while Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia posted increases.

| Language | Alberta | British Columbia | Ontario | Quebec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 16% | 3% | < 0% | -18% |

| French | 83% | 30% | 14% | -4% |

| French and English | 73% | 33% | 34% | -13% |

| Neither French nor English | 22% | 7% | 5% | -21% |

Source: IMDB (2016)

4.4 Comparison of services

Finding #4: The Government of Quebec funds language training, settlement and resettlement services that are generally similar to those funded by the Government of Canada. However, there are significant dissimilarities, particularly with regards to eligibility for services, which could lead to unequal access.

The Accord does not provide much guidance on how to assess the extent to which the services offered in Quebec correspond to those offered by Canada in the rest of the country. The Accord provides only a list of programs that the federal government would cease to deliver in the Province of QuebecFootnote 15, and requires that the services provided by the province:

- when considered in their entirety, correspond to the services offered by Canada in the rest of the country; and

- are provided without discrimination to all permanent residents in the province, whether or not they were selected by QuebecFootnote 16.

The evaluation considered these two requirements when comparing the services offered by the two jurisdictions.

Dissimilarities

To fully appreciate the settlement and language training services in Quebec and the rest of Canada, the following analysis focused on the dissimilarities between the two models. The document reviewFootnote 17 and interviews revealed that, overall, the types of services offered are comparable, but that there are some notable differences:

- Clients eligible for services: Quebec serves naturalized Canadian citizens and temporary residents (who hold a certificat d’acceptation du Quebec [CAQ]), including international students, temporary workers and refugee claimants. The other provinces must use their own resources to fund services to these groups. However, eligibility for the federal Settlement Program is limited to permanent residents of Canada and persons selected (who have been informed by a letter from IRCC) for permanent residence.

- Eligibility criteria: During the period covered by the evaluation, eligibility was different in terms of age and duration for permanent residents.

- Service delivery models: Quebec has a hybrid service delivery model. In other words, the provincial government and service providers are responsible for the delivery of settlement services. The provincial government is responsible for language training, while service providers are responsible for the delivery of individual and group settlement services.

- Funding models: Funding models differ for service providers. In Quebec, the budget allocated to service providers depends on the number of first interventions (target) that the MIDI allocates annually to each agency. The target is calculated based on the previous year’s target, which can be adjusted by the department.

- Language training: Quebec funds pre-arrival language training and provides financial incentives for taking language training.

- Pre-arrival services: The Government of Canada funds pre-arrival services that are available to permanent residents selected by Quebec (e.g., information and orientation, needs assessment, employment-related services, etc.).

Additional information on the dissimilarities between the services offered in the two jurisdictions is provided in Table 4.

| Comparison Elements | Quebec | Rest of Canada |

|---|---|---|

| Settlement Services | ||

| Eligibility ‒ Minimum age | 14 or 18 years, depending on service | No minimum age to access services |

| Eligibility ‒ Duration | 5 years, from the date of first status that makes a person eligibleTable note * | Permanent residents have access to services until they become Canadian citizens |

| Eligibility ‒ Immigration Status | Permanent residents, Temporary residents (who hold a CAQ), and Naturalized Canadian citizens | Permanent residents |

| Pre-Arrival Settlement Services | Online integration service (SIEL) is available prior to arrival | Pre-arrival services are available to all permanent residents, including those selected by Quebec (e.g., information and orientation, needs assessment, employment-related services, etc.). |

| Funding | Budget is calculated annually and is based on the previous year’s target (number of “first interventions "). | Cyclical tendering process and multi-year contribution agreements |

| Language Training | ||

| Eligibility - DurationTable note * | Full-time: 5 years, and Part-time: 10 years | Permanent residents have access to services until they become Canadian citizens. |

| Eligibility - Immigration Status | Permanent residents, Temporary residents (who hold a CAQ), and Naturalized Canadian citizens | Permanent residents |

| Pre-Arrival Language Training Services | Online francization service can be accessed abroad and in Quebec, and funding for French courses taken abroad | No language training service prior to arrival |

| Support Services | Clients reimbursed directly for childcare and transportation costs, and Financial incentives for participation | Some service providers are funded to provide the following services:

|

| Service Delivery Manager | Provincial Government | Service providers |

Eligibility

The document review revealed that permanent residents selected outside Quebec are eligible for the same settlement services funded by the Government of Quebec as those selected by Quebec. While the analysis of administrative data showed that some newcomers destined for other parts of Canada moved to Quebec during the period covered by the evaluation, it was not possible to determine the extent to which they accessed the services offered by that province.

However, although they have access to the same services, the duration of eligibility for services during the period covered by the evaluation was different in Quebec, compared to the rest of Canada. In Quebec, the duration is five years from the date of obtaining permanent residence, whereas, in the rest of Canada, permanent residents have access to services until they become Canadian citizens. Since newcomers are not required to obtain citizenship, there are fewer restrictions on the length of eligibility in the rest of Canada, allowing permanent residents more time to access services if they need them.

As shown in Figure 11, an analysis of iCARE data for newcomers accessing IRCC-funded settlement services in 2018 revealed that 29% of clients had been in Canada for more than five years. Given that the duration of eligibility in Quebec was a maximum of five years, it is possible that newcomers in Quebec may have needed to access settlement services, but were no longer eligible. As a result, this could have resulted in unequal access for newcomers who decided to settle in Quebec during the period covered by the evaluation.

Text version: Percentage of newcomers accessing an IRCC-funded service in 2018 by number of years since admission

| More than 10 years | 8% |

|---|---|

| 5 to 10 years | 21% |

| 5 years | 71% |

Source: iCARE (December 31, 2018)

It should be noted that the Government of Quebec has recently made changes to the eligibility criteria for settlement services. As of July 1, 2019, newcomers can now access services regardless of their year of arrival.

4.5 Languages of service

Finding #5: In accordance with the objectives set out in the Accord, Quebec funds services that are offered mainly in French to immigrants. Although other languages of service are available from community organizations in Quebec, the evaluation was unable to determine the extent to which service delivery reflects clients’ linguistic profile.

The document review and interviews indicated that clients in Quebec have access to individual settlement services (e.g., settlement and integration support) in languages other than French, including Arabic, Mandarin, Tagalog, Hindi and FarsiFootnote 18. However, group settlement services (e.g., French courses, first steps in settling in) are offered only in French.

However, the interviews revealed that Quebec does not systematically collect data on the languages used for service delivery. Given the lack of information on languages of service in Quebec, this makes it difficult to assess the extent to which Anglophone or allophone newcomers can access services in another language that could facilitate their access to services.

In the rest of Canada:

- Service providers are required to offer services in at least one of the two official languages. Of the service providers funded by IRCC, 47 are designated as Francophone organizations.

- In addition, for the past several years, the Government of Canada has had an initiative in place to promote and support immigration and the integration of newcomers into Francophone minority communities (FMCs).

- An analysis of iCARE data showed that in 2018, settlement services were accessed in 196 different languages, the most common being English, French, Arabic, Mandarin, Persian, Punjabi and Tagalog.

However, the literature review suggested that not all newcomers have access to settlement services. In fact, services are not always available in the official language of their choice, and these issues seem to affect both Francophone newcomers outside Quebec and Anglophone newcomers in QuebecFootnote 19. In addition, newcomers may need to access other services in their community, including provincial and municipal services, preferably in the official language of their choice. Once again, barriers to accessing services affect Francophone newcomers outside Quebec and Anglophone newcomers to Quebec.

4.6 Data collection for the comparative studies

Finding #6: The information collected as part of the comparative studies is limited to a detailed description of the types of services funded and is not based on a common indicator framework. As a result, the information provided by the two governments is not presented in a consistent manner, which makes it difficult to systematically compare and assess the quality of funded services.

IRCC began conducting comparative studies in 2013-14, following a recommendation from the 2012 evaluationFootnote 20 and in accordance with the requirements of the Accord. At the time of the evaluation, four studies had been completed.

In general, the comparative studies provide information on elements related to services funded by Canada and Quebec:

- Programs and types of services funded;

- Eligibility criteria for services (including details on who is eligible for services and the duration of their eligibility);

- The authorities responsible for the delivery of services; and

- Some statistical data on clients accessing services.

However, analysis of the information gathered from documents and interviews revealed challenges and gaps with regards to the comparative studies. In particular, the studies:

- lack consistency in the information provided in terms of the level of detail and data elements;

- lack of information in relation to programs and clients served, particularly in relation to outcomes;

- are not based on a framework with common indicators that allow for a clear, systematic and thorough comparison of similarities and dissimilarities between programs in the two jurisdictions. As a result, it is not possible to definitively conclude the extent to which services in Quebec correspond to those in the rest of CanadaFootnote 21.

In the fall of 2017, a report prepared by the VGQ noted several challenges in collecting MIDI data on settlement and francization services funded in Quebec. For example, the report noted that the MIDI had never completed an evaluation of the Réussir l’intégration Program and did not systematically collect data for performance measurement purposes.

However, IRCC has conducted evaluations of its Settlement Program and collects performance measurement data from its iCARE system and its survey of Settlement Program clients and non-clients.

4.7 Usefulness of the comparative studies

Finding #7: While the comparative studies meet the Accord’s requirements, the requirements are not clearly defined, providing only an overview of the funded services without any conclusions that could be used to assess the relevance and effectiveness of the services. Consequently, the studies are of limited usefulness to IRCC.

The document review and interviews revealed that the studies comparing services funded by the Government of Quebec and those funded by the Government of Canada meet the requirements of the Accord. However, the requirements of the Accord are unclear. The requirement for comparative studies, found in Annex A of the Accord, stipulates that the Joint Committee is mandated “to study, at least once a year, the reception and integration services provided by Canada and Quebec.” Thus, there is a lack of clarity and precision on the content and structure of the studies.

The study is currently able to identify dissimilarities and similarities between services, but is unable to analyze differences in outcomes of funded services. In fact, comparative studies state that services are equivalent overall. However, there are no indicators that clearly define what is meant by “equivalent”.

Interviews found that there is currently an under-utilization of the comparative studies and suggested ways to improve the studies and make them more useful:

- Given the lack of information on the outcomes and effectiveness of services, conduct, to the extent possible, effectiveness and performance measurement evaluations of funded services;

- Compare the objectives and innovative approaches of the two jurisdictions.

4.8 Management of the Grant

Finding #8: The governance structure in place at IRCC deals primarily with operational issues, and few resources are devoted to managing the Grant. However, no challenges have been identified with regard to its management.

IRCC has a limited role at the institutional level in Quebec and little attention is given by IRCC senior management to issues related to the Grant and the services it funds. In fact, documents and interviews confirmed that the Joint Committee and the Implementation Committee are in place for information sharing between Canada and Quebec, but they are used primarily to deal with immigration issues and not issues related to the Grant.

Interviews indicated that current resources are sufficient to support Grant-related work, which primarily involves calculating the Grant amount, disbursing funds and conducting the comparative studies. However, it should be noted that the frequency of comparative studies is now on a bi-annual rather than annual basis. This change was made in response to the workload associated with producing the study. The change in the frequency of the studies was accepted by the MIDI.

The evaluation found that the allocation of resources corresponds to the level of authority of IRCC over settlement in Quebec, but does not correspond to the amounts of money disbursed. Overall, due diligence measures employed by IRCC in relation to the Grant are limited. Although an evaluation of the Grant was conducted in 2012, there have been no recent audits of the Grant to Quebec. In comparison, over the past five years, the Department has conducted several evaluations of Settlement Program componentsFootnote 22 as well as two audits of the management and administration of its grant and contribution programs.

4.9 Level of funding in Quebec and the rest of Canada

Finding #9: The amount of the Grant has increased significantly and more rapidly than the funding provided by the federal government for the rest of Canada. This has widened the gap in funding per permanent resident between the two jurisdictions.

The evaluation conducted a cost-per-permanent-resident analysis by comparing the amount of funding provided for settlement services and the number of permanent residents admitted. Two sources of data were examined:

- GCMS data were used to analyze the number of permanent residents admitted to Canada between 2013 and 2018 who were destined to Quebec and to the rest of the country.

- SAP data were used to analyze financial data related to the Settlement Program and the Resettlement Assistance Program.

As shown in Figure 12, the results of the analysis indicated that:

- Between 2013-2014 and 2017-2018, the Grant amount increased from $320 million to $490 million, an increase of 53%. During the same period, operating costs and transfer payments for the Settlement and Resettlement Assistance Programs increased from $651 million to $845 million, an increase of 30%.

- The funding per permanent resident admitted to Quebec increased from $6,155 in 2013-2014 to $9,356 in 2017-2018, an increase of 52%. During the same period, funding per permanent resident admitted to the rest of Canada increased from $3,143 to $3,608, an increase of 15%.

- It should be noted that the analysis is based on the number of permanent residents admitted in each calendar year and does not take into account the total number of permanent residents in Quebec and the rest of Canada, who would also be eligible for funded services.

Text version: Amount of funding per permanent resident admitted to Quebec and the rest of Canada, 2013-2014 to 2017-2018

| 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | $6,155 | $6,776 | $7,046 | $7,103 | $9,356 |

| Rest of Canada | $3,143 | $3,188 | $3,420 | $3,466 | $3,608 |

Note: Amounts include transfer payments and operating costs for the Settlement Program and the Resettlement Assistance Program.

Sources: GCMS and SAP

| Transfer payments and operating costs ($ million)Table note * | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 319.9 | 340.5 | 345.1 | 378.2 | 490.3 |

| Rest of CanadaTable note * | 650.8 | 669.6 | 761.9 | 842.4 | 844.5 |

Sources: GCMS and SAP

| Number of permanent residents admitted | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 51,981 | 50,260 | 48,975 | 53,247 | 52,398 |

| Rest of Canada | 207,058 | 210,025 | 222,782 | 243,067 | 234,052 |

Sources: GCMS and SAP

5. Conclusions and recommendation

Overall, the evaluation found that the reception and integration services provided to newcomers in Quebec generally met the conditions of the Grant during the period covered by the evaluation, particularly with regards to:

- correspondence to services offered in the rest of Canada, and

- eligibility, i.e., permanent residents have access to the services whether or not they were selected by Quebec.

However, these conditions are not clearly defined, and there is a lack of common criteria and information needed for a more accurate analysis of the extent to which the conditions have been met.

Comparison of services

In general, the evaluation found that the types of reception and integration services in Quebec are generally similar to those offered in the rest of Canada. The evaluation also confirmed that these services are available to permanent residents who were not selected by the province of Quebec. However, there are several important dissimilarities in the way these services are delivered, including the eligibility for services. In particular, the duration of eligibility was shorter in Quebec relative to the rest of Canada during the period covered by the evaluation, which could have resulted in unequal access for newcomers who decide to reside in Quebec.

Comparative studies

Furthermore, although the comparative studies carried out by the Joint Committee meet the minimum requirements of the Accord, these requirements are not clearly defined. In addition, the information presented in the studies by the two governments is not consistent, and the information collected on the types of services offered lacks some essential elements, such as the language of services and the quality of the services provided.

This lack of consistency is due to the absence of a framework of common indicators allowing a clear and systematic comparison of services and the development of more rigorous conclusions. Improved indicators and data would allow for more in-depth analysis in the comparative studies, as well as the systematic evaluation of services provided in both jurisdictions in relation to requirements (a) and (b) of the Accord.

Recommendation: IRCC should explore a new methodological approach to make the collection of and access to data on the comparability of settlement services more rigorous, consistent and useful for the comparative studies.

Appendix A: Description of available IRCC databases

IMDB: The IMDB links IRCC immigration records with Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) tax records. The database provides data on the economic situation of newcomers who file a Canadian income tax return.

GCMS: GCMS is an integrated Web-based system that is used by IRCC to process immigration, citizenship and passport applications around the world.

iCARE: iCARE is a Web-based, performance measurement data collection system designed to collect information on clients and services in the context of settlement and resettlement programs offered by funding recipient organizations (recipients) to eligible newcomers.

Appendix B: Economic performance of newcomers from Quebec and the rest of Canada according to their knowledge of official languages in 2016

| Employment income | 1 year | 5 years | 10 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 61.1% | 67.3% | 67.5% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 78.4% | 74.6% | 69.6% |

| French | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 66.9% | 74.6% | 71.8% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 65.1% | 73.2% | 71.7% |

| French and English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 72.2% | 76.8% | 77.8% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 73.7% | 76.1% | 76.3% |

| Neither French nor English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 44.4% | 54.3% | 64.8% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 48.1% | 52.8% | 59.2% |

| Median income | 1 year | 5 years | 10 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | $18,400 | $21,800 | $25,900 |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | $27,931 | $32,486 | $37,464 |

| French | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | $17,300 | $21,600 | $28,500 |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | $15,556 | $22,079 | $30,673 |

| French and English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | $25,400 | $32,100 | $43,100 |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | $30,008 | $38,603 | $53,290 |

| Neither French nor English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | $14,400 | $15,000 | $15,100 |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | $16,203 | $16,579 | $20,490 |

| Proportion of social assistance recipients | 1 year | 5 years | 10 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 7.7% | 9.6% | 9.0% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 4.2% | 5.8% | 6.3% |

| French | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 17.1% | 9.0% | 8.9% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 19.5% | 11.4% | 11.5% |

| French and English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 8.6% | 5.3% | 3.8% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 8.1% | 5.6% | 3.5% |

| Neither French nor English | |||

| Newcomers - Quebec | 25.6% | 14.5% | 14.1% |

| Newcomers - Rest of Canada | 19.3% | 10.9% | 9.2% |