Evaluation of the Refugee Resettlement Program

Evaluation Division

Audit and Evaluation Branch

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

August 2024

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response Action Plan (MRAP)

- List of Acronyms

- List of Figures

- Overview of the Refugee Resettlement Program

- Evaluation of Background and Context

- Methodology

- Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

- Profile of Resettled Refugees

- Profile of Resettled Refugees: Socio-Demographic

- Evaluation Findings

- Conclusions and Recommendations

- Annex A: Refugee Resettlement Program Logic Model

- Footnotes

Executive Summary

Background

This report presents the findings of the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) evaluation of the Refugee Resettlement Program. This evaluation was conducted in fulfillment of the requirements under the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results and assessed the relevance, performance, and governance of the program between period of January 2016 to December 2021.

The objective of this evaluation was to assess the performance of the program in meeting its expected outcomes. The evaluation also considered strengths and limitations of program design, as well as program integrity and management, including clarity and appropriateness of roles and responsibilities among program partners.

Summary of Key Findings

The evaluation found that there is a clear and strong rationale for the program and it is well aligned with GOC objectives, in particular around saving lives and offering protection. The program has been leveraged to address humanitarian crises, although this may come at the expense of reduced attention to traditional resettlement objectives. In addition, prioritizing certain groups contributes to potentially inequitable access to timely protection and concerns over the use of public policies. Program governance remains a challenge, with negative impacts on internal coordination and communication and relationships with external stakeholders.

The program is meeting refugees’ immediate and essential needs, however, Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR) experience challenges in having their needs met compared to sponsored refugees, particularly in periods of mass arrivals. Challenges in finding permanent housing has had negative impacts on income support and service delivery, and income support continues to be insufficient to meet refugees’ basic needs. Further, the ultimate outcome of refugees living independently and how the program contributes to this outcome are unclear.

Recommendations

In response to the findings, the evaluation proposes the recommendations below.

- IRCC should review Resettlement Program objectives to clarify and update its performance measurement framework to ensure expected outcomes, indicators and targets are clear, and appropriate for the program’s role.

- IRCC should clarify and communicate internal Resettlement roles and responsibilities, and improve communication and coordination at the working level and with external stakeholders.

- IRCC should develop and implement a strategy to address the impacts of overstays in temporary accommodations that ensures the timely and consistent delivery of Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) services to GARs.

- IRCC should incorporate a strategy to ensure effective and equitable service delivery during periods of mass arrivals in the Crisis Response Framework.

- IRCC should review income support mechanisms more regularly to ensure that rates are aligned with provincial/territorial social assistance, and that they are meeting the basic needs of GARs.

- Taking into consideration sponsor concerns related to program requirements for the Private Sponsorship of Refugees program, IRCC should:

- Develop and implement measures to help mitigate the impact of secondary migration on sponsors; and

- Work with program delivery partners to help address challenges in responding to program requirements and take measures, as appropriate.

Management Response Action Plan (MRAP)

Recommendation 1

The evaluation found that the Resettlement Program’s ultimate outcome of independent living is not clearly defined or agreed upon as it relates to measures like social assistance and settlement service use. Further, the program’s expectations surrounding employment, including which refugees should be employed and on what timeline are unclear.

In addition, the Resettlement Program was noted to rely on the Settlement Program to achieve this ultimate outcome. Interviewees expressed doubt over whether the Resettlement Program had the right mechanisms to influence long-term outcomes, and this reliance on the Settlement Program created confusion about the Resettlement Program’s expected outcomes, pointing to a need to reconfirm those respective objectives.

IRCC should review Resettlement Program objectives to clarify and update its performance measurement framework to ensure expected outcomes, indicators and targets are clear, and appropriate for the program’s role.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

As refugee protection needs reach unprecedented levels and new humanitarian crises unfold around the world, the Resettlement Program will continue to be a key avenue to offer protection to displaced persons in need of a durable solution.

With the ongoing changes in the global protection landscape and increasingly frequent requests to leverage the Resettlement Program to address emerging crises and targeted populations in need/crisis, it is timely to assess the Program and its objectives with a view to ensuring they are clear and remain fit for purpose.

Furthermore, the stated policy objectives of the program focus on the responsiveness of the program to offer protection, while the majority of the outcomes focus on individual client integration outcomes.

In 2024, IRCC developed a new combined logic model for both the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) and the Settlement Program to align objectives with respect to in-Canada supports provided to resettled refugees after landing in Canada. This updated logic model was developed to support the recent RAP and Settlement Call for Proposals (CFP). This work will contribute to distinguishing outcomes related to pre-arrival activities and in-Canada supports, and the development of appropriate performance indicators.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 1A: Taking into account recently revised RAP/Settlement Logic Model, undertake full review of Resettlement Program logic model, including validating foundational program objectives. |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch Support: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch, Settlement and Integration Policy Branch, International Crisis Response – Resettlement Operations, Migration Response Policy |

Q1 2025-26 |

Action 1B: Update Performance Information Profile and seek PMT and PMEC approval. |

Same as Action 1A |

Q2 2025-26 |

Recommendation 2

The evaluation found that internal governance had remained a challenge in the Resettlement Program. Program governance is complex and fragmented across multiple branches and sectors, contributing to a lack of clarity on internal roles and responsibilities and to internal communication and coordination challenges, particularly at the working level. As well, governance challenges were felt to negatively impact IRCC’s engagement with external stakeholders. It should be acknowledged that significant departmental restructuring took place in 2023, which has begun to address governance and coordination issues.

IRCC should clarify and communicate internal Resettlement roles and responsibilities, and improve communication and coordination at the working level and with external stakeholders.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The evaluation findings around program governance reflect a period prior to a major departmental reorganization, which aimed to address those issues. The changes and initiatives outlined below have already taken place and address this recommendation.

As part of the IRCC realignment announced in September 2023, a number of changes were made across the Department with direct impacts on the management of the Resettlement Program. Main highlights include:

- Creation of a new International Affairs and Crisis Response (IACR) Sector.

- Operational and policy functions related to selection and pre-arrival for the Resettlement Program being together under one Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) in a new Asylum and Refugee Resettlement Sector.

A subsequent restructuring brought those same operational and policy functions together under a new Resettlement Program Branch. Combined, these changes served to consolidate senior management responsibilities, while also bringing together working level teams for improved coordination.

In May 2021, Settlement Network (SN) consolidated its resettlement operations under the leadership of the SN-Resettlement Operations Directorate; and, in September 2023, in-Canada policy functions related to Resettlement and Crisis Response were brought together in the Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch. In February 2022, a DG Resettlement Committee was launched and ADM meetings are also convened as needed.

With regard to external stakeholders, in June 2023 a SAH liaison role was developed to better support SAHs on enquiries, assist with complex cases, and other issues.

In order to fully address the recommendation, as a next step, IRCC could more deliberately share information about these organizational changes with key resettlement stakeholder groups.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 2A: IRCC focal points for engagement with key external stakeholders will provide a detailed overview of organizational changes, roles and responsibilities and key contacts at the next meetings for each group (e.g. NGO-GOV meeting with SAH Council, Borders to Belonging, GAR-RAP Working Group). |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch Support: International Crisis Response – Resettlement Operations, Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch, Settlement Network |

Q3 2024-25 |

Recommendation 3

The evaluation found that extended stays in temporary accommodations is a growing concern and may negatively impact support and services for refugees. While internal documents state that refugees are intended to spend 1-3 weeks in temporary housing, evidence suggested that most GARs spend at least one month.

The evaluation found that overstays may limit the overall financial support that GARs receive, and can lead to essential services being delayed, duplicated, or less effective. Concerns were also noted that overstays may delay refugees’ independence or make it more difficult for refugees to adjust to their permanent accommodations.

IRCC should develop and implement a strategy to address the impacts of overstays in temporary accommodations that ensures the timely and consistent delivery of RAP services to GARs.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

GAR admissions have increased substantially in recent years, growing from approximately 10,800 admissions in 2021 to over 23,900 admissions in 2023, primarily in the context of the Afghan resettlement initiative, placing significant strain on service provider organizations (SPOs). This has included pressure on stays in temporary accommodations, and since the COVID-19 pandemic and in the context of mass arrivals, the length of stay in temporary accommodations has risen further. However, GAR admissions are expected to reduce significantly in the next few years based on the Multi-Year Immigration Levels Plan.

Several strategies have been implemented to support and manage arrivals and capacity with SPOs. These include:

- Volumetrics: The Department adjusts community targets annually and looks to continuously improve the alignment of arrivals with SPO and community capacity.

- Capacity: Since 2022 IRCC, has encouraged SPOs to identify specific housing coordinators and has provided support for landlord liaisons in major urban centers where SPOs felt this would be beneficial. In addition, IRCC organized a national landlord event with the RAP SPO Secretariat. IRCC has increased funding for professional development of RAP SPO staff, and there is now a quarterly virtual meeting with staff dedicated to housing search to ensure effective onboarding of new staff and rapid sharing of effective best practices.

- Income Support (IS): The income support made available to RAP clients in a challenging housing market also determines how quickly RAP SPOs can help clients secure permanent accommodations. IRCC has concluded two rate reviews since the evaluation period that has updated federal allowances and aligned with changes to provincial social assistance rates and is shifting to a regular rate review to keep as current as possible.

- IRCC also introduced the housing top up initiative as a time-limited pilot initiative to address the gap between actual lease costs and financial support provided to GARs to use for securing accommodations, and is assessing the outcomes of this initiative.

- Addressing complex cases: IRCC recognized a typology of clients staying for long periods in accommodations beyond volume of arrivals. As a result, in 2022 IRCC created a national complex case team and funded complex case positions at RAP SPOs who had a demonstrated need.

- Finally, IRCC has issued functional guidance and has worked with RAP SPOs to ensure that the program parameters are respected in terms of how many permanent accommodation options are shown to clients while in IRCC-funded temporary accommodations.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 3A: Refine strategy to accurately track pacing and arrivals to best support clients upon arrival to ensure timely move outs and timely access to services. |

Lead: Settlement Network Support: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch, International Crisis Response – Resettlement Operations, Migration Health Branch, Resettlement Program Branch |

Q4 2024-25 |

Action 3B: Undertake review of community capacity surveys. Provide resources for SPOs to best support timely moveouts. |

Same as Action 3A |

Q3 2024-25 |

Action 3C: Develop national service standard dashboard for RAP IS tracking. |

Same as Action 3A |

Q3 2024-25 |

Action 3D: Engage internal partners to develop strategy/framework for addressing complex needs, including development of a standard definition for complex cases. |

Same as Action 3A |

Q4 2024-25 |

Recommendation 4

While IRCC data do not differentiate between mass arrivals and regular arrivals, evidence suggested that GARs arriving during years of mass arrivals are less likely to receive services in their first weeks in Canada, or report that the services they received met their needs. Mass arrivals were found to increase the time spent in temporary accommodations, impacting the timeliness and quality of immediate services for GARs. As well, the evaluation noted concerns related to the equity of service delivery during periods of mass arrivals, as well as impacts on RAP SPO staffing and capacity. Further, it was noted that SPO staff may be too busy to provide tailored support to refugees during these periods.

IRCC should incorporate a strategy to ensure effective and equitable service delivery during periods of mass arrivals in the Crisis Response Framework.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

GAR admissions increased substantially in recent years, growing from approximately 10,800 admissions in 2021 to over 23,900 admissions in 2023, primarily in the context of the Afghan resettlement initiative. This increased client load placed significant strain on service provider organizations delivering immediate and essential RAP services. Developing a strategy for service delivery during potential future periods of mass arrivals will support more effective and equitable RAP service delivery. This strategy could be a tool falling under IRCC’s new Crisis Response Framework (CRF), to support arrivals in times of crisis.

IRCC committed to developing the Crisis Response Framework (CRF) in the October 2023 report, An Immigration System for Canada’s Future, to improve decision-making and promote equity with respect to crises, including by implementing a more predictable process and consistent criteria for assessing emerging situations and tools to guide policy analysis, program design and implementation, evaluation, and ongoing engagement with Provinces/Territories (PT), partners, and stakeholders.

As part of ongoing work on the CRF, IRCC is also exploring the development of new tools to deliver supports and services to individuals arriving in Canada through both Temporary Resident (TR) and Permanent Resident (PR) crisis pathways that are outside of Canada’s existing refugee resettlement pathways, with the aim of helping to reduce the pressures placed on SPOs in the crisis context, which may in turn improve service delivery for clients including crisis arrivals and GARs.

IRCC worked closely with the RAP providers through this period of mass arrivals, supported by an IRCC-funded RAP SPO Secretariat. IRCC intends to maintain support for this Secretariat so that the RAP SPOs are able to retain the lessons learned from this period and the capacity to ramp up as required to address GAR targets.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 4A: Develop a strategy to ensure effective and equitable RAP service delivery for GARs during periods of mass arrivals. |

Lead: Settlement Network Support: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch |

Q4 2024-25 |

Action 4B: Maintain support for a national RAP SPO Secretariat to ensure robust coordination between IRCC and RAP SPOs in periods of mass arrivals through CFP 2024. |

Lead: Settlement Network Support: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch |

Q1 2025-26 |

Action 4C: As part of a new Crisis Response Framework, develop new tools to provide supports and services to individuals arriving in Canada as part of a migration response to a crisis. |

Lead: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch Support: Migration Response Policy Branch, Settlement Network |

Q2 2025-26 |

Recommendation 5

The evaluation found that RAP income support rates continue to be insufficient for meeting refugees’ immediate and essential needs. While income support rates aim to be in accordance with provincial or territorial social assistance rates, they fall below Canada’s official measure of poverty and have not kept up with the cost of living or inflation, particularly related to housing costs. A strong majority of surveyed refugees reported having to work because income support was insufficient to cover their basic needs. The evaluation also found extensive use of food banks among refugees, particularly GARs who rely solely on RAP income support.

In March 2023, IRCC introduced the Housing Top Up Initiative (HTUI) to help address the housing affordability gap and to help refugees secure permanent housing. The HTUI provides a supplementary allowance to refugees to meet housing needs. Building on such innovative efforts as the HTUI:

IRCC should review income support mechanisms more regularly to ensure that rates are aligned with provincial/territorial social assistance, and that they are meeting the basic needs of GARs.

Response: IRCC agrees with the recommendation.

Given the evaluation findings that RAP income support is insufficient for GARs to meet their basic needs, there is a need to explore options for better meeting these needs.

RAP income support includes monthly allowances for housing, food and incidentals. These allowances are required to align with the social assistance rates in the province where the GAR is living, as outlined in the Terms and Conditions of the RAP program. This ensures that GARs receive a level of financial support that is similar to what is received by Canadians in financial need, and also helps to ensure a smooth transition to provincial social assistance (for GARs who need it), once the RAP period ends. When provinces update their social assistance rates, for example due to rising costs of living, IRCC follows suit to ensure parity.

RAP income support also includes national allowances, including a one-time start-up allowances for furniture and household staples, and a monthly housing supplement. IRCC sets these rates independently of provincial social assistance rates, based on an assessment of actual costs.

IRCC has recently completed a review of RAP IS rates. Based on this review rates for most clients were increased on June 1, 2024, based on provincial rates as of December 2022. Changes vary by province and family composition. RAP IS rates were last updated in the fall of 2021. To help better address rising costs of living, IRCC intends to undertake regular RAP IS rate reviews, with the next rate review being initiated in fall 2024 with rate updates taking effect in mid/late 2025.

Given the current housing crisis, and to help GARs with rapidly escalating housing costs, IRCC implemented a pilot program in March 2022, called the Housing Top-Up Initiative (HTUI), to provide GARs an additional exceptional income support allowance to cover actual housing costs. This pilot is set to expire in December 2024. IRCC is currently undertaking analysis of this pilot, to inform options for better addressing the housing needs of GARs once this pilot ends.

IRCC is also conducting analysis around the RAP Additional Income Incentive, to ensure that it is acting as an incentive, and not a deterrent, for GARs to access the labour market.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 5A: Undertake a RAP income support rate review on a regular basis, to ensure that parity with provincial social assistance rates is maintained in a timely manner. |

Lead: Mass Arrivals Settlement Branch Support: Settlement Network |

Q4 2024-25, ongoing |

Action 5B: Complete analysis of HTUI effectiveness and impact to inform decision on future of HTUI pilot. |

Same as Action 5A |

Q4 2024-25 |

Action 5C: Complete analysis around the 50% Additional Income Incentive, to inform potential changes to this incentive. |

Same as Action 5A |

Q4 2024-25 |

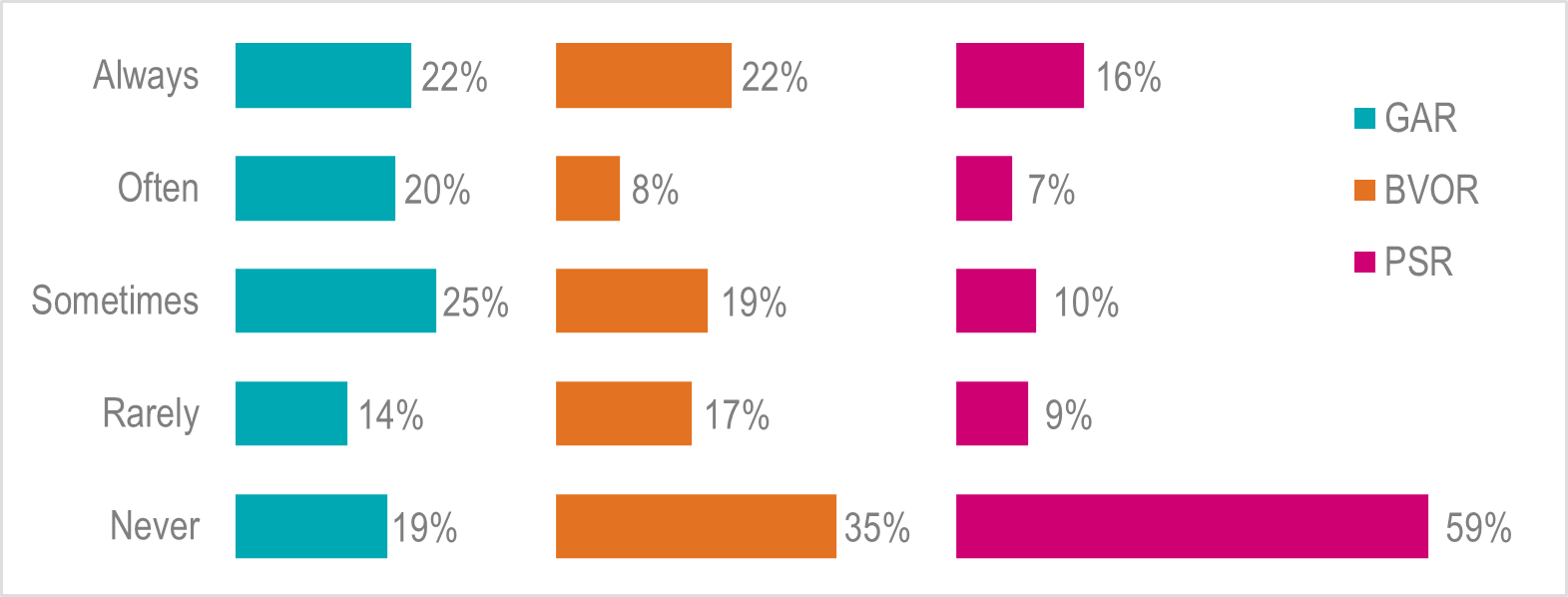

Recommendation 6

The evaluation found that while the Private Sponsorship of refugees was working well overall, there are some challenges for sponsors. Secondary migration of sponsored refugees presents challenges for sponsors, who experience administrative or financial burdens and potential sponsorship penalties as a result.

Further, while the program has improved oversight, the evaluation found that sponsors who sponsor family members may experience challenges in meeting program requirements and demonstrating adequate support.

Taking into consideration sponsor concerns related to program requirements for the Private Sponsorship of Refugees program, IRCC should:

- a) Develop and implement measures to help mitigate the impact of secondary migration on sponsors; and

- b) Work with program delivery partners to help address challenges in responding to program requirements and take measures, as appropriate.

Response: IRCC agrees with the recommendation

6. a) IRCC’s current policies and practices in this area focus on minimizing impacts of secondary migration on sponsors. When secondary migration occurs and sponsors cannot meet new requirements, a non-punitive sponsorship breakdown is declared and there is no assessment of fault if the sponsor can demonstrate they attempted to meet these requirements.

Work is ongoing to respond to concerns raised by sponsors about secondary migration, including through improving the information refugees receive before and upon arrival to Canada about this issue, and through funding a third party provider, the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program (RSTP), to offer supports and guidance for sponsorship groups on how to reduce the likelihood of secondary migration (e.g., setting realistic expectations for settlement both pre- and post-arrival, and facilitating integration into the local community).

The Department will explore if there are other potential mitigations to financial impacts on sponsors resulting from secondary migration.

6. b) There is already a significant amount of flexibility in the case review process for demonstrating that program requirements have been met. However, IRCC understands case monitoring requirements around proofs of support to be a particular area of concern of program delivery partners. Measures to address sponsor concerns will need to be balanced with program objectives for the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. IRCC will work with sponsorship partners to better understand these concerns as part of monitoring the implementation of the Program Integrity Framework and associated measures.

| Action | Accountability | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

Action 6A(1): Update communications/outreach documents to help better inform refugees of the consequences of self-destining and secondary migration. |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch Support: Settlement Network |

Q1 2025-26 |

Action 6A(2): Conduct further analysis on impacts and mitigations for secondary migration and implement any applicable policy changes. |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch Support: Settlement Network |

Q1 2025-26 |

Action 6B(1): In consultation with external program delivery partners, update guidelines for responding to program requirements in case monitoring. |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch |

Q1 2025-26 |

Action 6B(2): Working with SAHs and building on evidence from the evaluation, review challenges around program requirements, particularly with regard to proofs of support, and take measures as appropriate and within program authorities. |

Lead: Resettlement Policy Branch |

Q1 2025-26 |

List of Acronyms

- BVOR

- Blended Visa Office-Referred

- CEEDD

- Canadian Employer Employee Dynamics Database

- CG

- Constituent Group Sponsor

- CCB

- Canada Child Benefit

- CS

- Community Sponsor

- G5

- Group of Five Sponsor

- GAR

- Government-Assisted Refugee

- GBA+

- Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- GOC

- Government of Canada

- HTUI

- Housing Top Up Initiative

- ICARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IFHP

- Interim Federal Health Program

- ILP

- Immigration Loans Program

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- GN

- Global Network

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- LGBTQ2

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit

- MRAP

- Management Response Action Plan

- NAT

- Notice of Arrival Transmission

- OSR

- Operation Syrian Refugees

- PIF

- Program Integrity Framework

- PMEC

- Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee

- POE

- Port of Entry

- PSR

- Privately Sponsored Refugee

- RAP

- Resettlement Assistance Program

- RAP SPO

- Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organization

- RSAT

- Resettlement Services Assurance Team

- RSD

- Refugee Status Determination

- RSTP

- Refugee Sponsorship Training Program

- SAH

- Sponsorship Agreement Holder

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- UNHCR

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

List of Figures

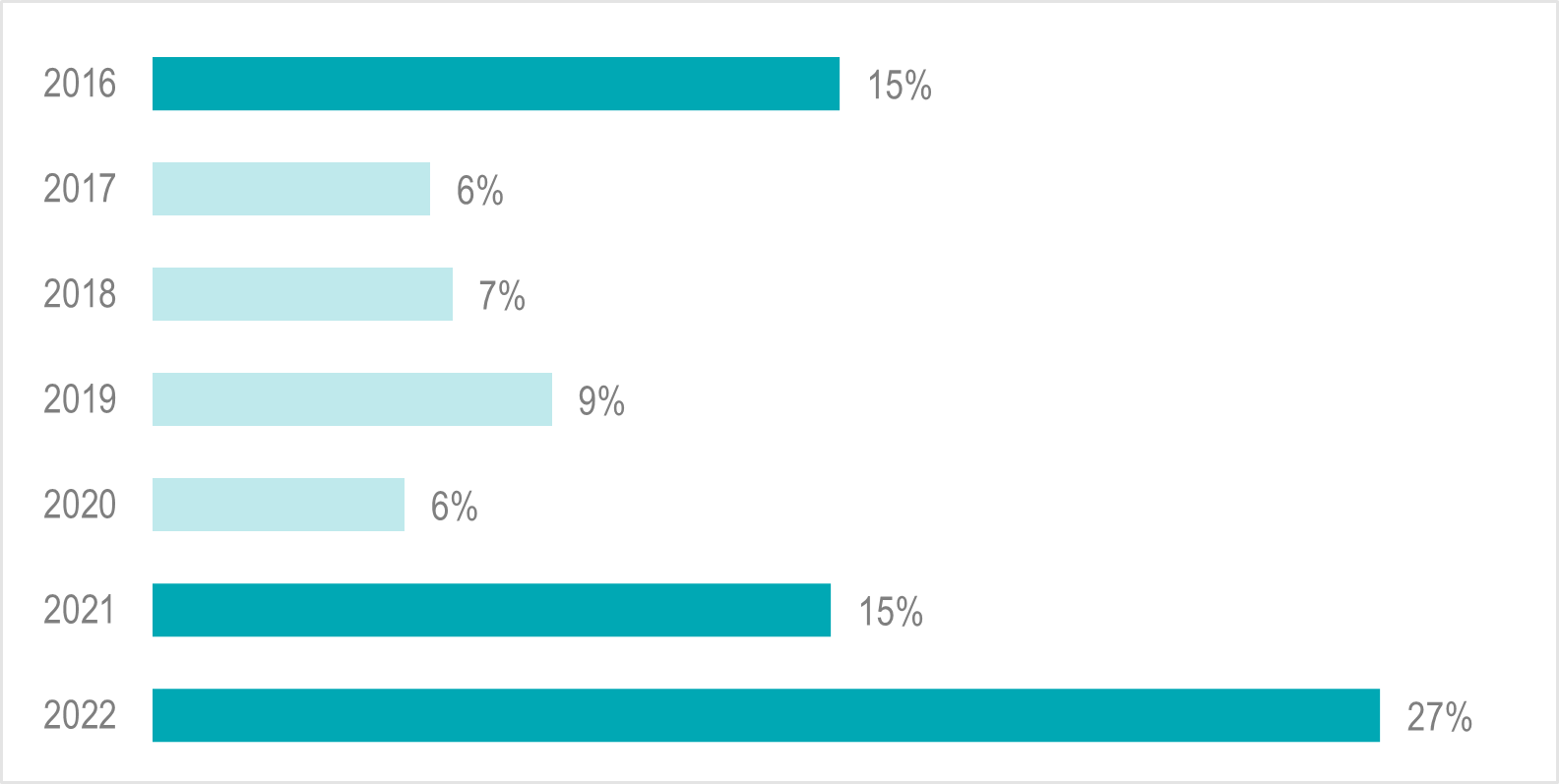

- Figure 1: Refugees Admitted by Stream, 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

- Figure 2: Countries of Birth of Refugees Admitted (GCMS)

- Figure 3: Socio-Demographic Profile of Refugees Admitted 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

- Figure 4: Refugees Resettled vs Global Need for Resettlement (GCMS, UNHCR)

- Figure 5: Refugee Admissions by Stream, 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

- Figure 6: Processing Time of Refugee Applications by Stream, 80th Percentile Decision Period (GCMS)

- Figure 7: Processing Time of Refugee Applications in 2021 by Country of Residence, 80th Percentile Decision Period (GCMS)

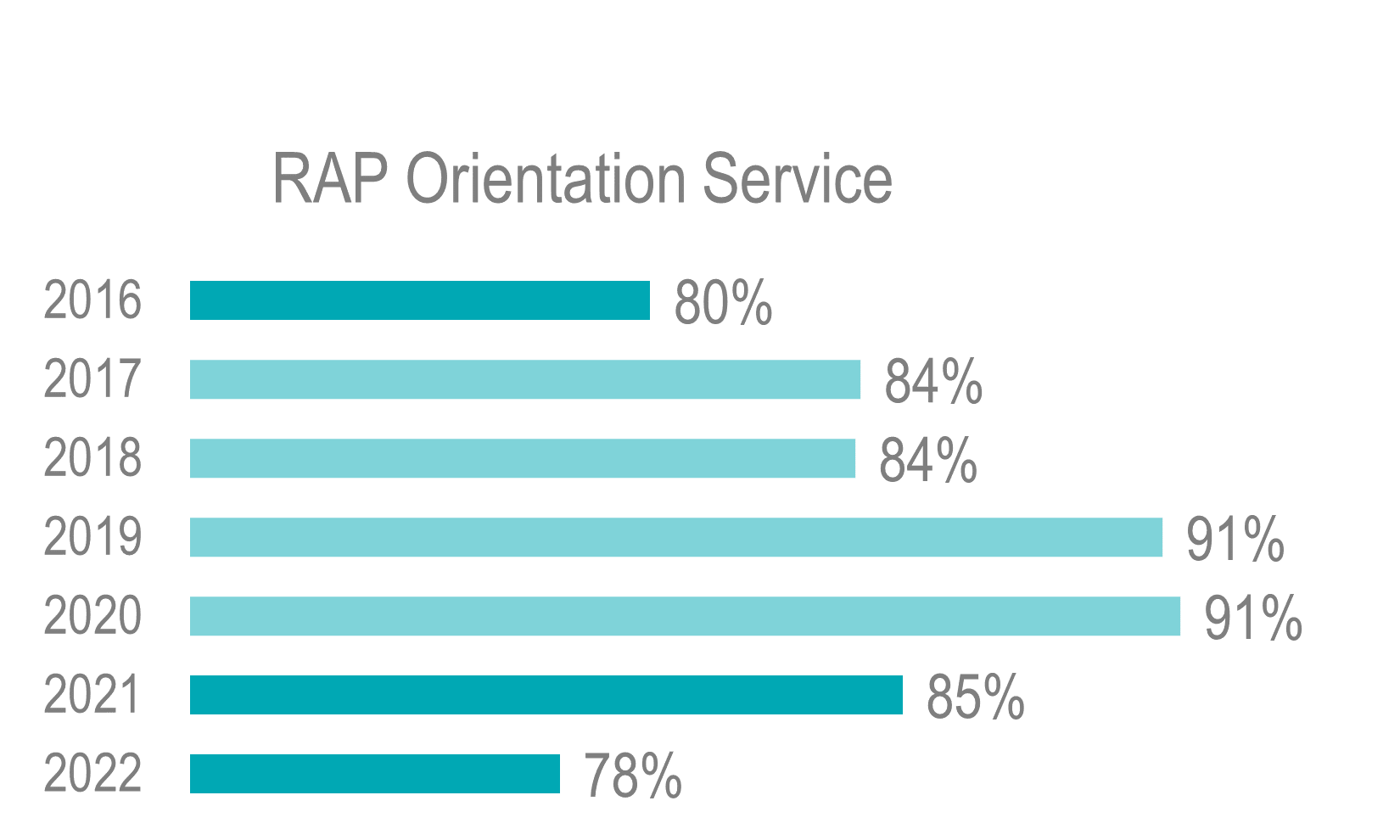

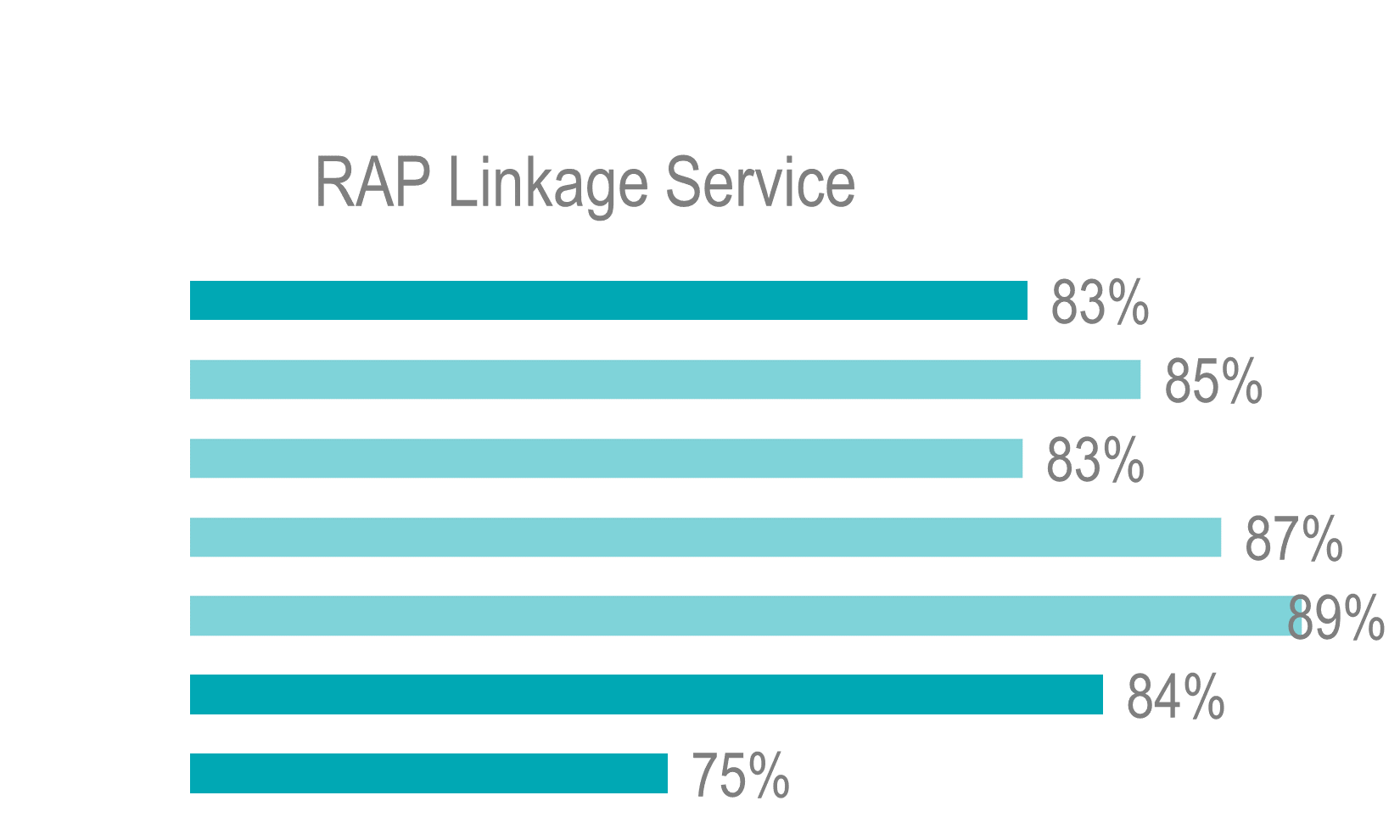

- Figure 8: Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Receiving Start-Up Supports

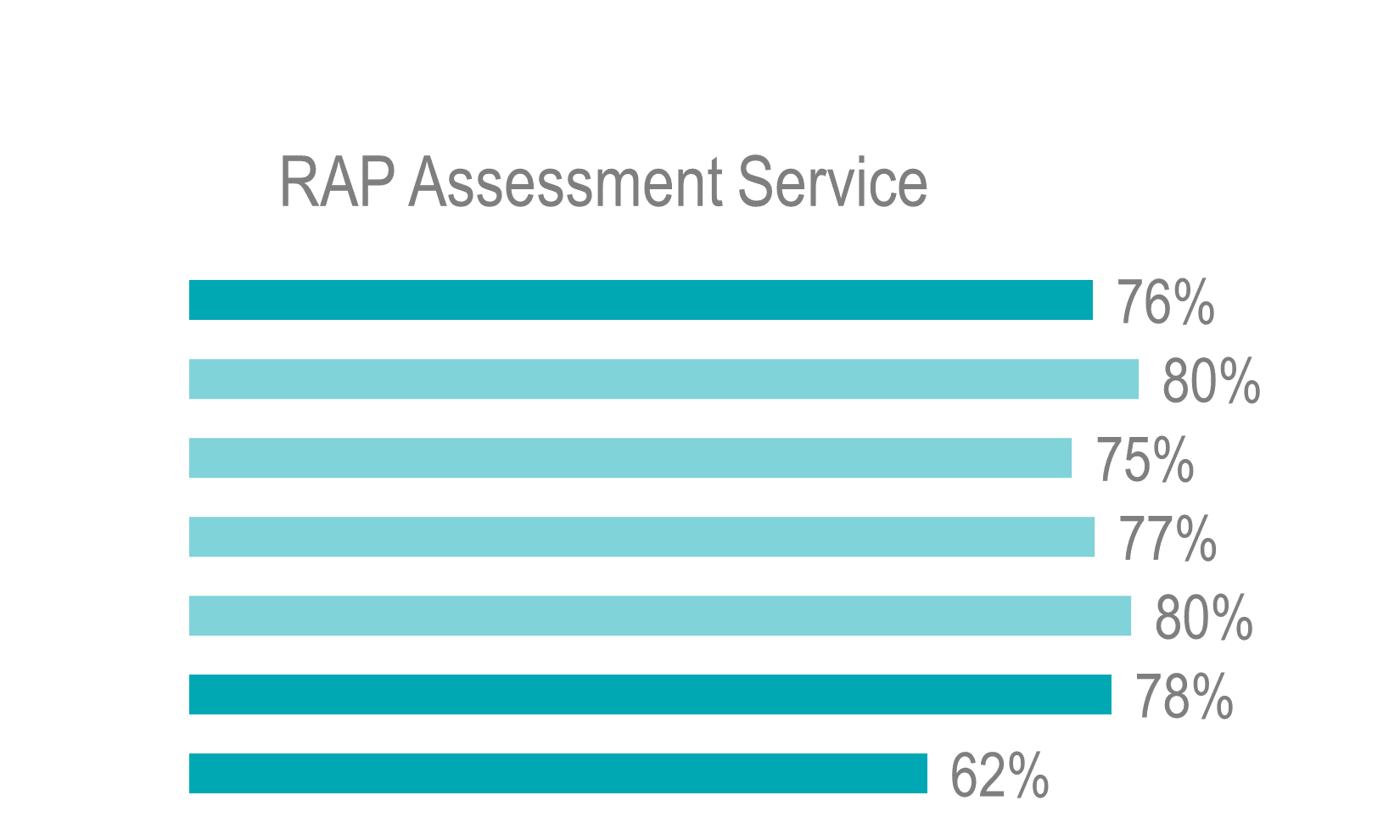

- Figure 9: Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Having “All” or “Most” of Their Start-Up Needs Met

- Figure 10: Share of Surveyed Refugees Across GBA+ Groups Who Reported Experiencing Barriers in Accessing Supports

- Figure 11: Share of Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Receiving the Housing Information They Needed

- Figure 12: Share of GARs Receiving Services Reported (iCARE)

- Figure 13: Share of Refugees in Temporary Housing for More Than Six Weeks (iCARE)

- Figure 14: Interprovincial Outmigration within One Year of Admission, 2009-2019 (IMDB)

- Figure 15: Share of Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Using a Foodbank During Their First Year

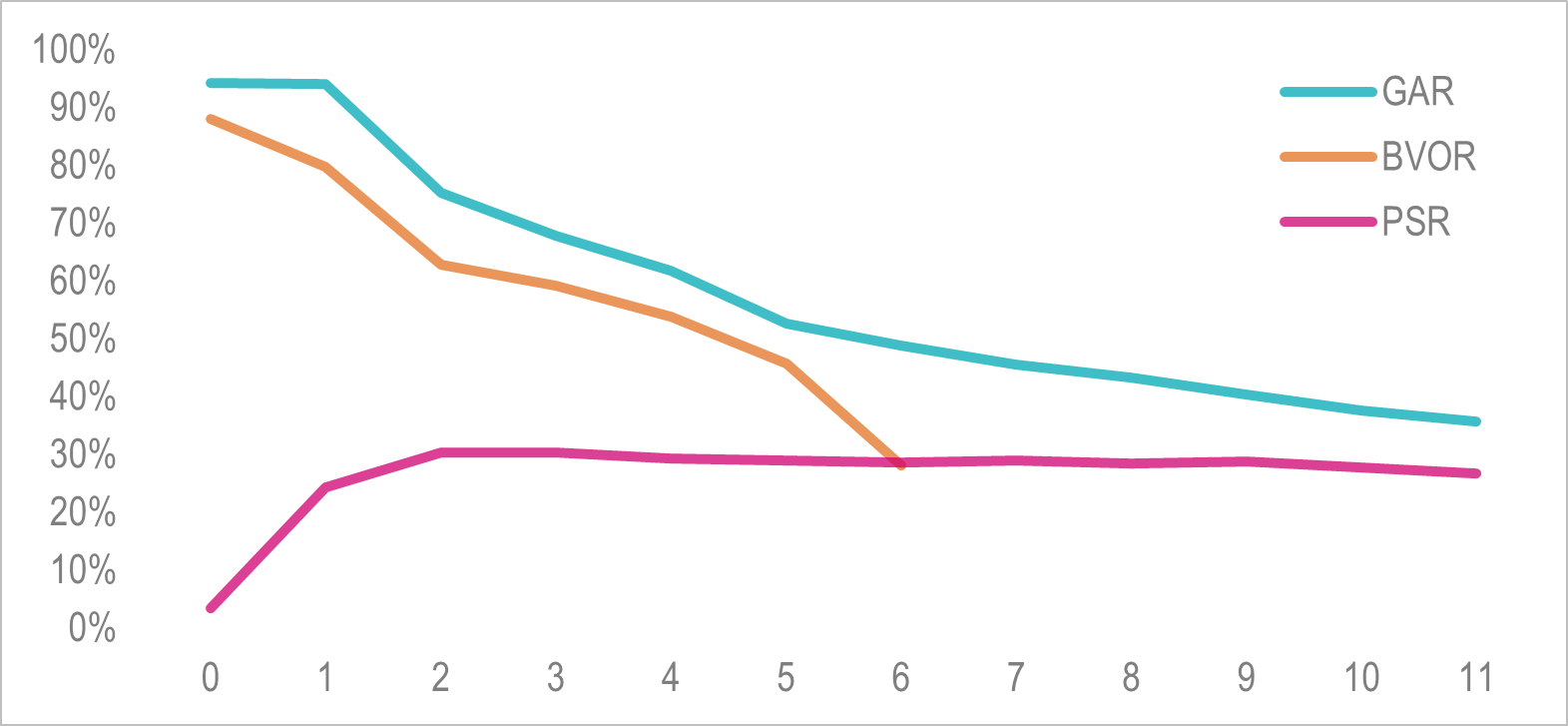

- Figure 16: Social Assistance Use by Years After Admission (IMDB)

- Figure 17: Median Family Income, Years After Admission (IMDB)

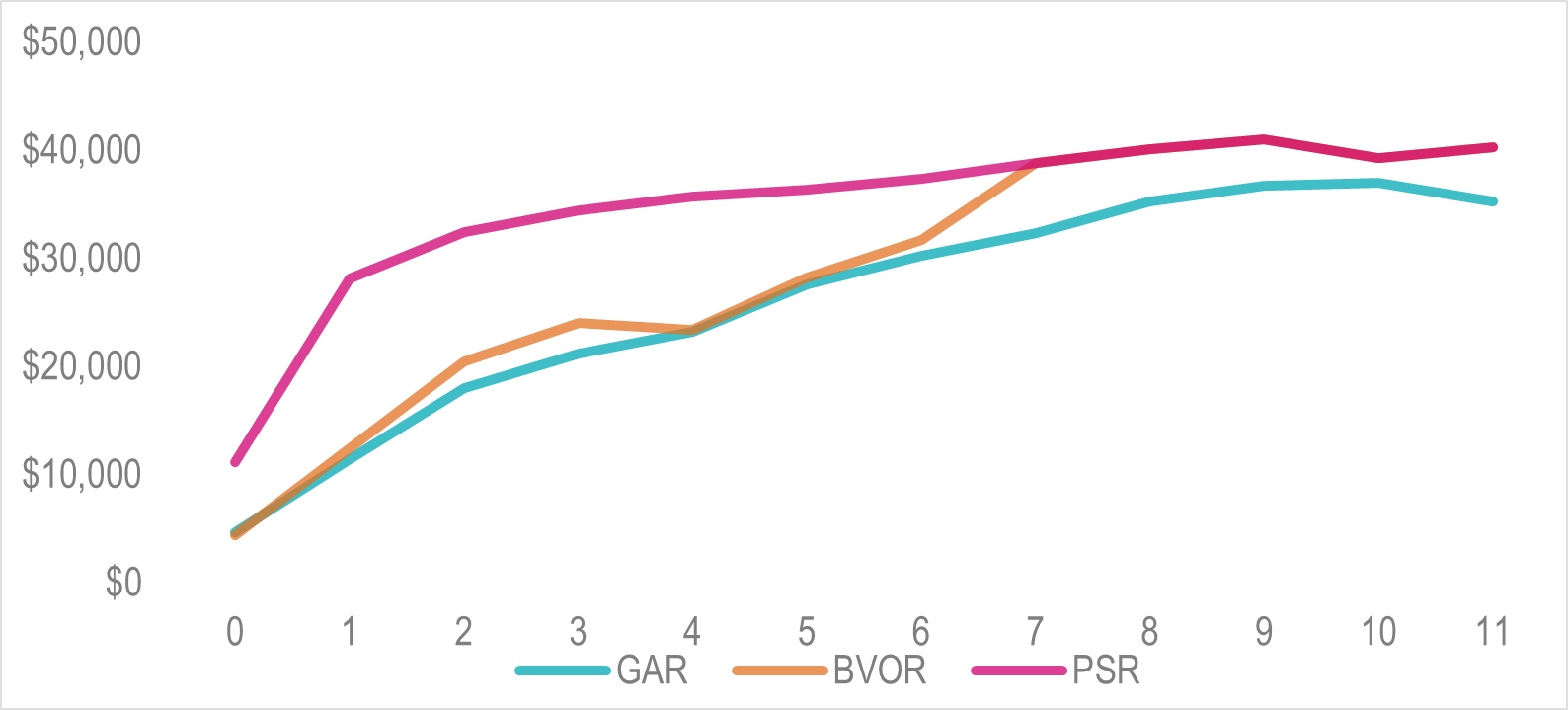

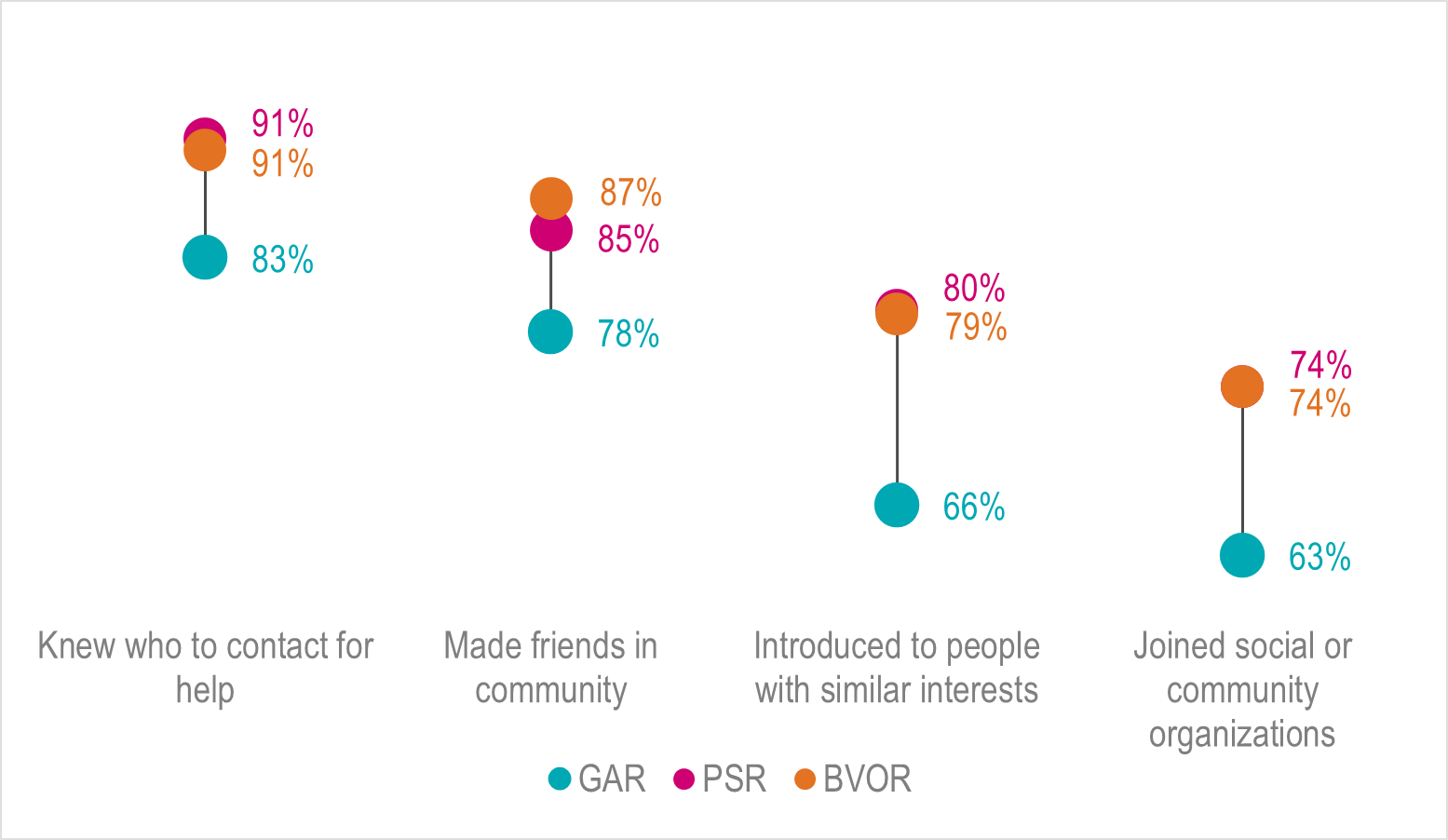

- Figure 18: Share of Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Making Social Connections in Their First Year

Overview of the Refugee Resettlement Program

Background

The Resettlement Program is in the first instance about saving lives and offering protection. The program helps maintain Canada’s humanitarian traditions and obligations by offering permanent residence to refugees and other persons in need of protection when no durable solutions are available.

In accordance with Canada’s Immigration Levels Plan, IRCC facilitates the admission of a targeted number of refugees as permanent residents through the Resettlement Program. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR) provide for the resettlement of both Convention Refugees Abroad and Country of Asylum Classes.

Respectively, eligibility for these two classes is based on well-founded fears of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion or group membership, or having been, and continuing to be, seriously and personally affected by civil war, armed conflict or massive violation of human rights. Refugees must also be outside of their home country or the country where they normally live.

Between 2016 and 2022, Canada admitted 207,060 refugees, including 110,147 Privately Sponsored, 88,838 Government-Assisted, and 8,075 Blended Visa Office-Referred refugees.

Program Streams

Refugees selected for resettlement to Canada are issued visas to travel to Canada via the following Resettlement Program streams:

Government-Assisted Refugee (GAR)

GARs are referred by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or other referral organizations based on vulnerability. GARs receive up to one year of income support from the Government of Canada (GOC), as well as immediate and essential services delivered through IRCC-supported non-governmental agencies, referred to as Service Provider Organizations (SPOs).

Privately Sponsored Refugee (PSR)

PSRs are identified and sponsored by Canadian citizens or PRs, including Sponsorship Agreement Holders (SAH), Constituent Groups (CG), Groups of Five (G5) and Community Sponsors (CS). Sponsors provide financial, emotional, and other support for up to one year.

Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR)

BVORs are referred by the UNHCR or other referral organizations and identified internally as cases to be matched with private sponsors. Sponsors share financial responsibilities with the GOC, with each providing six months of income support. Sponsors also cover one-time start-up costs and immediate and essential supports.

Supporting Service Programs

Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP)

The RAP supports GARs and other eligible recipients upon arrival to Canada. This program includes two components:

- Direct financial support for eligible refugees, including a one-time start-up payment and monthly income support for up to one year (in exceptional circumstances up to 24 months); and

- Funding for RAP SPOs to deliver immediate and essential services for 4 to 6 weeks, including: temporary accommodation and assistance finding permanent housing, orientation to life in Canada, and referrals to services.

Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP)

The IFHP provides pre-departure medical services, temporary health care coverage in Canada until individuals qualify for provincial/territorial health care coverage, and supplemental health care coverage for up to one year.

Immigration Loans Program (ILP)

The ILP provides clients with loans to cover the cost of transportation to Canada, and for assistance with basic needs in Canada.

Evaluation of Background and Context

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of the Resettlement Program. It was conducted by IRCC’s Evaluation Division between July 2022 and December 2023, assessing program performance, as well as providing timely evidence and results to support policy development and program delivery.

This evaluation fulfills requirements under the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results and the Financial Administration Act.

Evaluation Scope

The evaluation covers the period of January 2016 to December 2021, although administrative data were updated to include 2022.

The evaluation scope does not include ongoing special programs for the resettlement of Afghan nationals, nor does it address special objectives related to the ILP, the IFHP or pre-arrival settlement services, as separate evaluations have been recently completed or will be planned for these areas. However, high-level contributions from these areas to the overall objectives of the Resettlement Program are included in the scope.

The evaluation is guided by a Terms of Reference, which was developed with input from program representatives and approved by IRCC’s Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC).

Evaluation Focus

The primary focus was the performance of the program in meeting its expected outcomes, as well as the social and economic outcomes of refugees resettled through the program.

Refugee Resettlement Program Outcomes

- Immediate: Timely protection of resettled refugees, and the immediate and essential needs of resettled refugees met.

- Intermediate: Resettled refugees have tools to live independently in Canadian society.

- Ultimate: Resettled refugees live independently in Canadian society.

The evaluation also considered strengths and limitations of program design, including differences between GARs, PSRs and BVORs, need for and complementarity of the program streams, and program interactions with referral agencies.

To a lesser extent, the evaluation examined program integrity in the PSR program and program management, including clarity and appropriateness of roles and responsibilities among program partners.

Evaluation Questions

- To what extent do different program streams align with the objectives of the program?

- To what extent is the program effectively designed and coordinated among program partners?

- To what extent are PSR sponsors providing an adequate level of support to the refugees they sponsor?

- To what extent does the program provide timely protection to resettled refugees?

- To what extent is the program meeting the immediate and essential needs of refugees?

- To what extent does the program contribute to refugees’ abilities to live independently in Canadian society?

Methodology

The evaluation employed multiple methods, described below.

Document Review

The document review included internal and external documents relevant to the Resettlement Program, including: GOC and departmental documents; academic literature; stakeholder documents; legislative and regulatory documents; program, policy, and monitoring documents; and functional guidance.

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews were conducted with 57 interviewees virtually using Microsoft Teams, and included:

- 42 IRCC program representatives;

- 7 RAP SPO representatives;

- 4 SAH Council and SAH Navigation Unit representatives;

- 2 Refugee Sponsorship Training Program (RSTP) representatives;

- 1 UNHCR representative; and

- 1 International Organization for Migration (IOM) representative.

Administrative Data Analysis

An analysis was conducted on data from IRCC’s Global Case Management System (GCMS) to develop a socio-demographic profile of refugee admissions between 2016 and 2022. Information on processing times and the application inventory were also reviewed.

GCMS data were combined with data from IRCC’s Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE) to develop a profile of Port of Entry (POE) and RAP services provided to refugees.

Data from the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) were used to provide measures of incidence of employment, median employment earnings, and secondary migration over time. Tax files from 2009 to 2020 were examined in aggregate, including T1 Family and T4 Supplementary data for refugees admitted in the same period.

All datasets were also used to contextualize program trends.

Refugee Survey

The survey was administered online and sent to all resettled refugees, admitted to Canada between 2016 and 2022, aged 18-75 and for whom contact information was available (N=94,325). The survey included questions about their first weeks and first year in Canada. The survey was available in English, French, Arabic, Dari, Tigrinya and Pashto, and received 6,391 responses for a response rate of 7%.

Sponsor Survey

The survey was administered online and sent to all individuals who sponsored PSRs and/or BVORs between 2016 and 2022 and for whom contact information was available (N=27,751).Footnote 1 The survey sought perceptions on training/resources, coordination with IRCC, and relationships with and outcomes of refugees. 2,156 responses were received for a response rate of 8%.

RAP SPO Survey

The evaluation leveraged an online survey, administered as part of the IRCC Evaluation of Migration Health Programming, to gather RAP SPO perspectives on supporting GARs. The survey included questions on pre-arrival coordination and immediate/essential service provision over the previous 5 years. 35 RAP SPOs identified by internal stakeholders were included in the distribution list for this survey, and 19 responded.

Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

The evaluation approach used complementary methods, and collected both quantitative and qualitative data.

Data Availability and Quality

iCARE Data Reporting

Stakeholders noted gaps in iCARE reporting owing to the urgency/priority of service delivery, particularly during periods of mass arrivals. In addition, stakeholders acknowledged delays in RAP SPO reporting on service provision. To minimize the impact of reporting delays, the evaluation allowed for a nearly year-long lag before extracting the data (i.e., data on services provided up to December 31, 2022 were extracted in December 2023). Further, evidence from the data analysis was triangulated with results from other lines of evidence, such as refugee, sponsor, and RAP SPO survey responses related to service delivery, as well as interviews and document review.

Mass Arrivals

Impacts of mass arrivals were a consistent theme raised by stakeholders. However, at the time of the evaluation, IRCC did not collect systematic data on whether refugees arrive in Canada as part of mass arrivals. In the absence of a defined measure of mass arrival, the evaluation employed a proxy variable using data available on country of residence (i.e., Syria, Afghanistan) and year of admission (i.e., 2016, 2021-2022). Notably, this measure does not account for potential impacts on service delivery/provision for other refugees arriving through regular pacing concurrent to mass arrivals.

Refugee Coding in GCMS

An error in coding BVOR admissions in GCMS was found after data were extracted for the evaluation. This error resulted in an over-reporting of BVORs in 2022. To mitigate this issue, refugee numbers were adjusted based on internal reporting tools for the 2022 admission year.

Survey Representativeness

Refugee Survey

Compared to the population of refugees admitted in the scope of the evaluation, the survey over-represented refugees admitted to Canada in 2022 (+9.8%), males (+8.9%), refugees with knowledge of English (+7.2%), and refugees holding bachelor’s degrees (+8.0%). Survey results were triangulated with other lines of evidence, including a literature review that gathered information on and perspectives of under-represented groups. In addition, interviews included specific questions on the extent to which different sociodemographic factors influenced program outcomes.

Sponsor Survey

IRCC collects limited information on the characteristics of sponsors, making it difficult to assess sponsor survey representativeness. To mitigate this issue, survey results were triangulated with other lines of evidence where possible, notably interviews with SAH representatives.

RAP SPO Survey

The population of RAP SPOs is small and changes over time. While more than half of RAP SPOs contacted for the survey provided responses, the small sample size precludes results from being generalized to the entire RAP SPO population. To enhance confidence in findings related to RAP SPOs, the evaluation conducted interviews with RAP SPO representatives in addition to the survey. Findings are based on triangulation of results between multiple lines of evidence.

Profile of Resettled Refugees

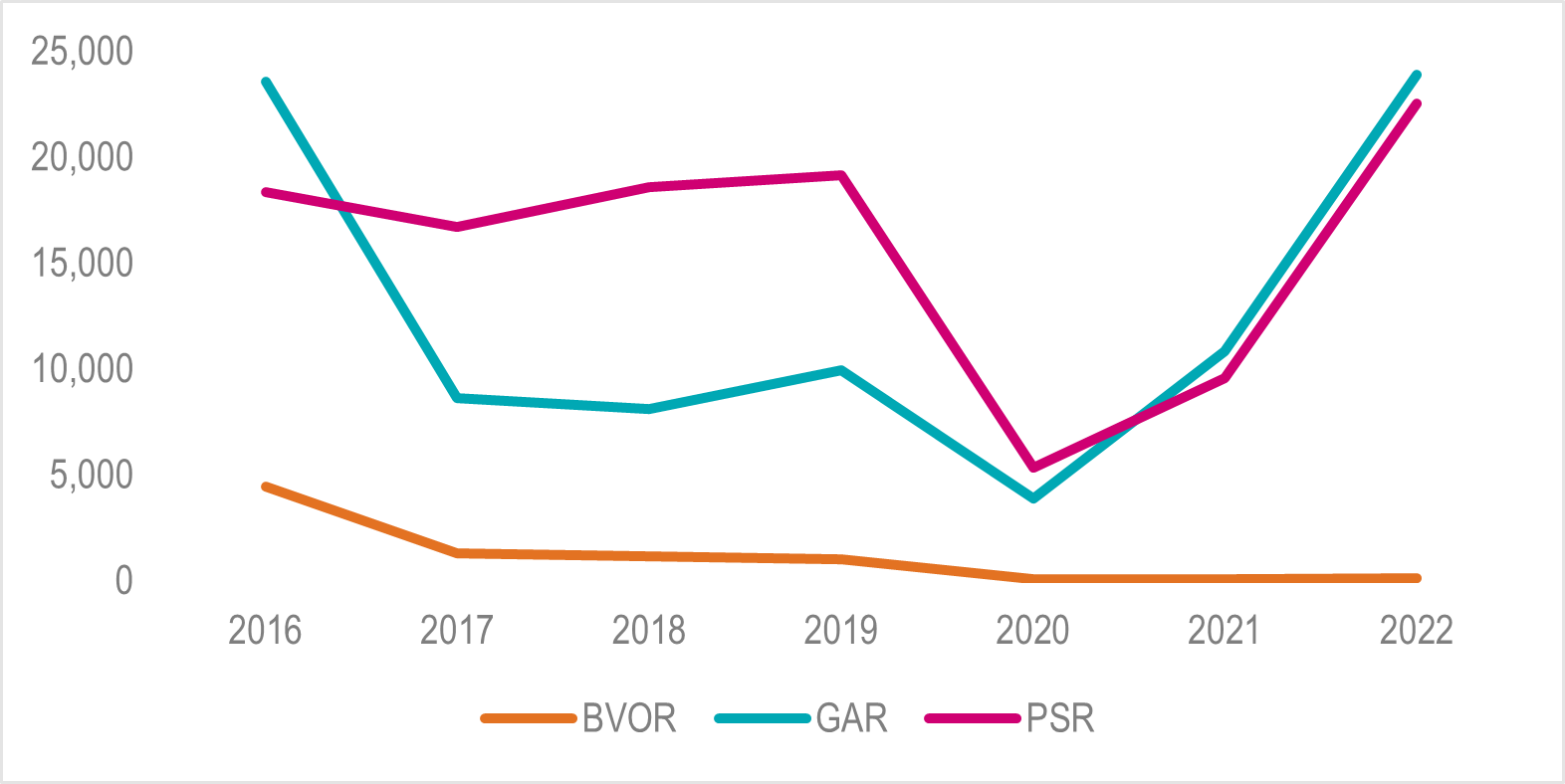

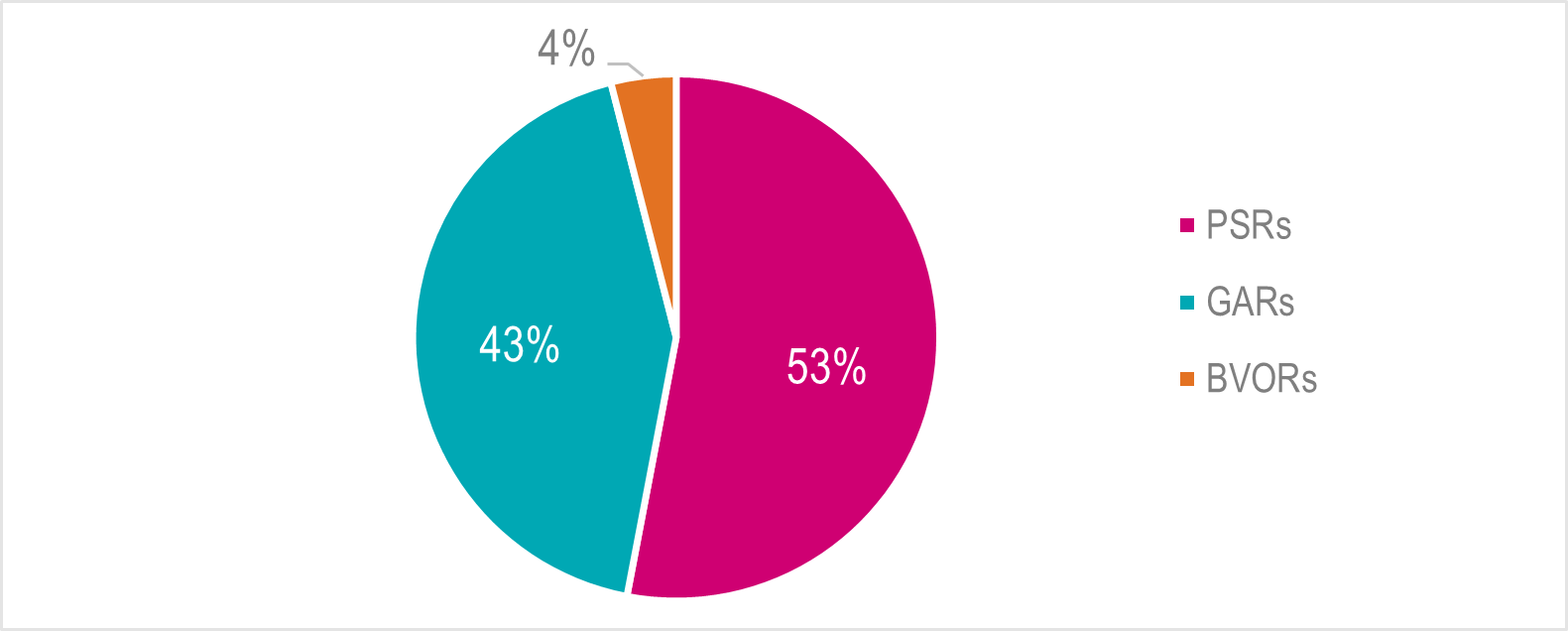

Between 2016 and 2022, 207,060 refugees were admitted to Canada, including 110,147 PSRs (53%); 88,838 GARs (43%) and 8,075 BVORs (4%).The number of refugees admitted to Canada varied by year. Admissions were highest during years of country-specific mass arrivals (namely Operation Syrian Refugee and the Afghan Commitment), and lowest during years of the COVID-19 pandemic and corresponding travel restrictions. In terms of admissions by stream:

- PSR admissions remained relatively steady over time, with the exception of years with COVID-19 restrictions.

- Between 2017 and 2019, the number of GARs admitted was consistently below half of 2016 levels.

- The number of BVORs admitted decreased over time, with more arriving in 2016 (4,420) as arrived in all subsequent years (3,655).

Figure 1: Refugees Admitted by Stream, 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

Figure 1

The figure depicts a line chart showing the number of refugees admitted by stream, by year, between 2016 and 2022. The figure shows the following data points for BVORs: 2016: 4,420; 2017: 1,285; 2018: 1,149; 2019: 993; 2020: 52; 2021: 76; 2022: 100. The figure shows the following data points for GARs: 2016: 23,560; 2017: 8,638; 2018: 8,093; 2019: 9,952; 2020:3,871; 2021: 10,812; 2022: 23,912. The figure shows the following data points for PSRs: 2016: 18,361; 2017: 16,698; 2018: 18,568; 2019: 19,143; 2020: 5,313 2021: 9,543; 2022: 22,521.

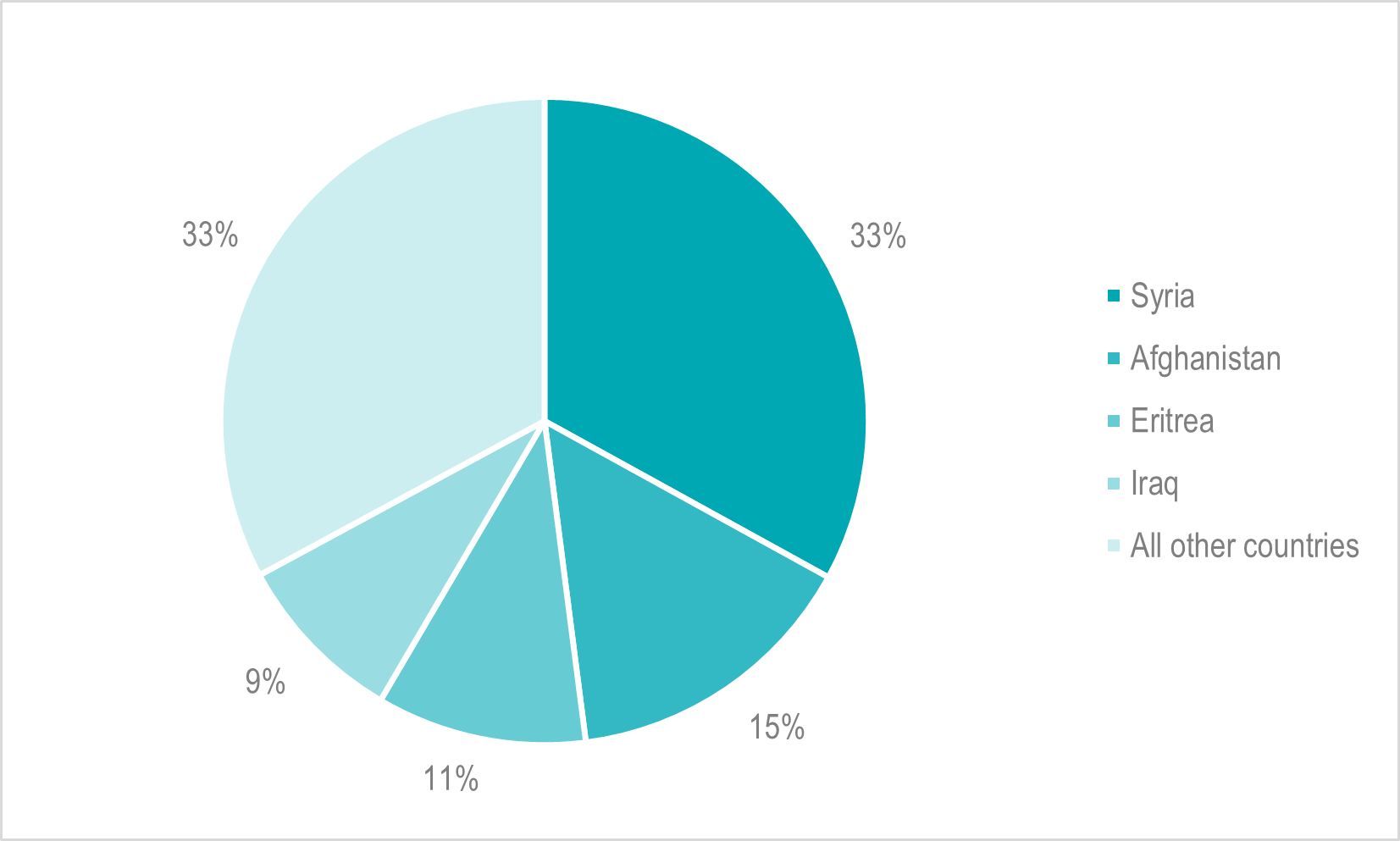

Trends in Country of Birth

Overall, nearly half of refugees admitted between 2016 and 2022 were born in Syria (33%) or Afghanistan (15%). The distribution of countries of birth varied by year; for example, Syrians accounted for 66% of admissions in 2016, but 13% in 2022. Afghans made up 2% of admissions in 2016, but 41% of admissions in 2022.

Figure 2: Countries of Birth of Refugees Admitted (GCMS)

Figure 2

The figure depicts a pie chart showing the most common countries of birth among refugees admitted to Canada between 2016 and 2022. The figure shows the following data points: Syria: 33%; Afghanistan: 15%; Eritrea: 11%; Iraq: 9%; All other countries: 33%.

The top countries of birth reflect public commitments made by the GOC in response to global humanitarian crises:

Operation Syrian Refugees (OSR)

In late 2015 and early 2016, the GOC made several commitments to resettle Syrian refugees in Canada, including to resettle at least 25,000 Syrian refugees in 2016.Footnote 2

Commitment to Afghan Nationals

In August 2021, the GOC committed to resettling 40,000 Afghans. Those arriving through the humanitarian program stream of this commitment fall under the GAR and PSR program streams.Footnote 3

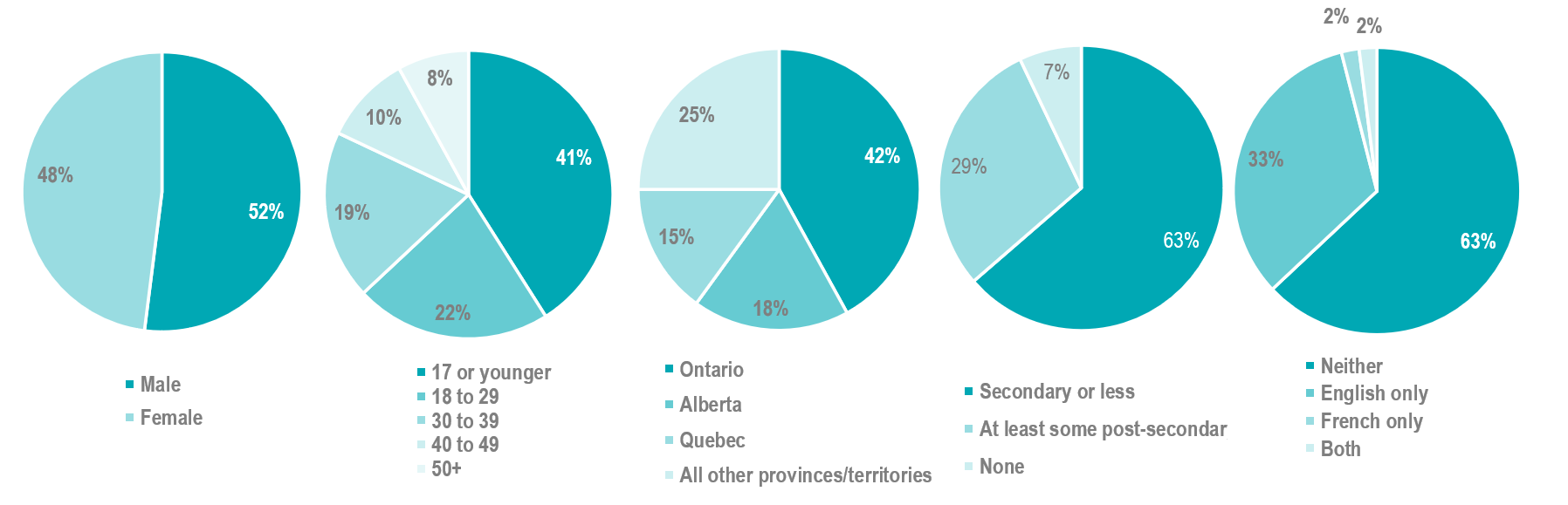

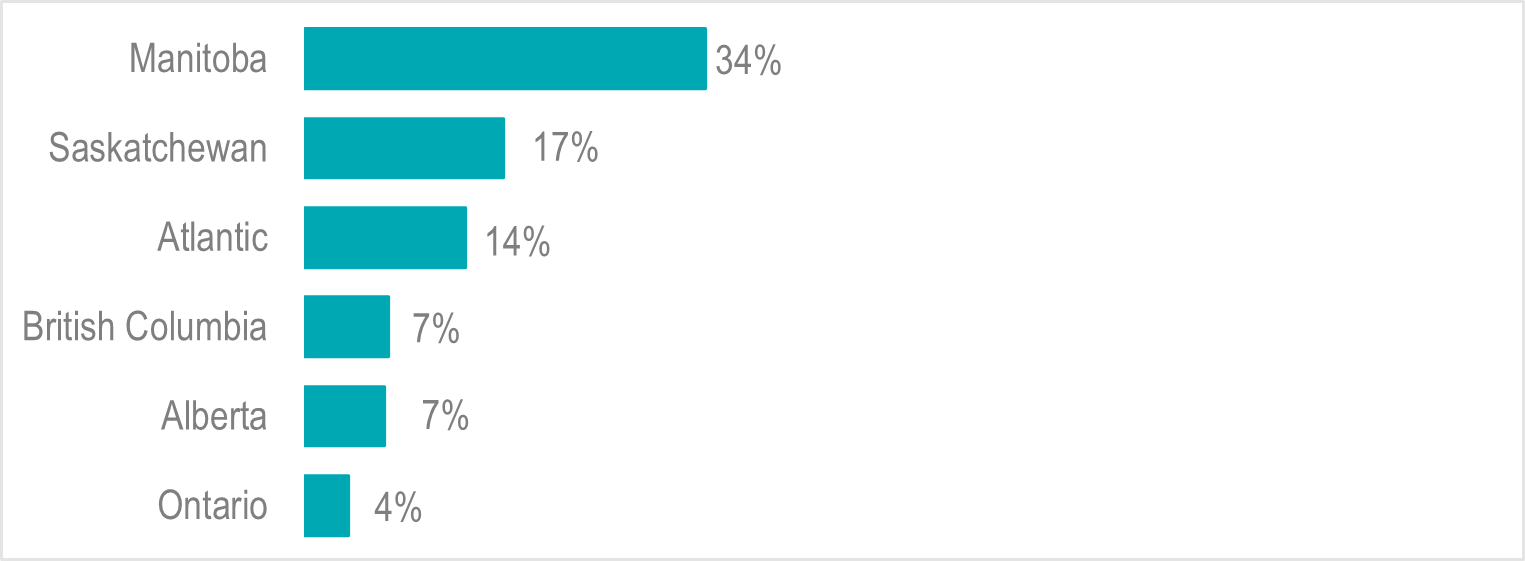

Profile of Resettled Refugees: Socio-Demographic

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Administrative data provides a profile of resettled refugees at admission, including the refugees’ gender, age, intended destination, education levelFootnote 4, and knowledge of official languages reported at their admission to Canada.Footnote 5

Figure 3: Socio-Demographic Profile of Refugees Admitted 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

Figure 3

Figure three presents five pie charts covering the sociodemographic profile of refugees admitted between 2016 to 2022, including distribution of gender, age, province/territory, education, and official language capacity. The chart for gender presents the following data points: Male: 52%; Female: 48%. The chart for age presents the following data points: 17 or younger: 41%; 18 to 29: 22%; 30 to 39: 19%; 40 to 49: 10%; 50+: 8%. The chart for provinces/territories presents the following data points: Ontario: 42%; Alberta: 18%; Quebec: 15%; All other provinces/territories: 25%. The chart for education presents the following data points: Secondary or less: 63%; At least some post-secondary: 29%; None: 7%. The chart for official language presents the following data points: Neither English nor French: 63%; English only: 33%; French only: 2%; Both French and English: 2%.

Differences by Program Stream

The evaluation found some differences in the characteristics of refugees admitted by Resettlement Program stream. In general:

- A greater share of PSRs (54%) had at least some official language capacity at admission, compared to 17% of GARs and 20% of BVORs.

- A greater share of PSRs (36%) had at least some post-secondary education, compared to 19% of GARs and 14% of BVORs.

- BVORs and GARs tended to be younger with 71% of BVORs and 70% of GARs under 30 years old at the time of admission, compared to 57% of PSRs.

Evaluation Findings

Need and Rationale

Finding 1: There is a clear and strong rationale for the Resettlement Program as it provides immediate protection and a durable solution for refugees and helps Canada meet its international obligations.

Refugee Protection

The UNHCR recognizes refugees as “people who have fled their countries to escape conflict, violence, or persecution and have sought safety in another country.”Footnote 6 International obligations in refugee protection are grounded in the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, as well as the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees. Signatory countries, including Canada, have a responsibility to provide protection and durable solutions through one of three solutions:

- Voluntary repatriation (refugees voluntarily return to their home country once conditions are safe);

- Local integration (integrating into the country where refugees have sought asylum); or

- Third-country resettlement (refugees are selected from their country of asylum to be transferred to a third country). Resettlement is often used as a solution of last resort.

According to the UNHCR, refugee resettlement is intended to be a protection tool to meet refugees’ needs, to offer a long-term solution to refugees, and to be a responsibility-sharing mechanism between countries hosting refugees.

Canada’s International Obligations

Document review and interviews found a clear and strong rationale for the Resettlement Program in responding to Canada’s international obligations, as Canada meets its obligations in refugee protection and responsibility-sharing primarily through the Resettlement Program.

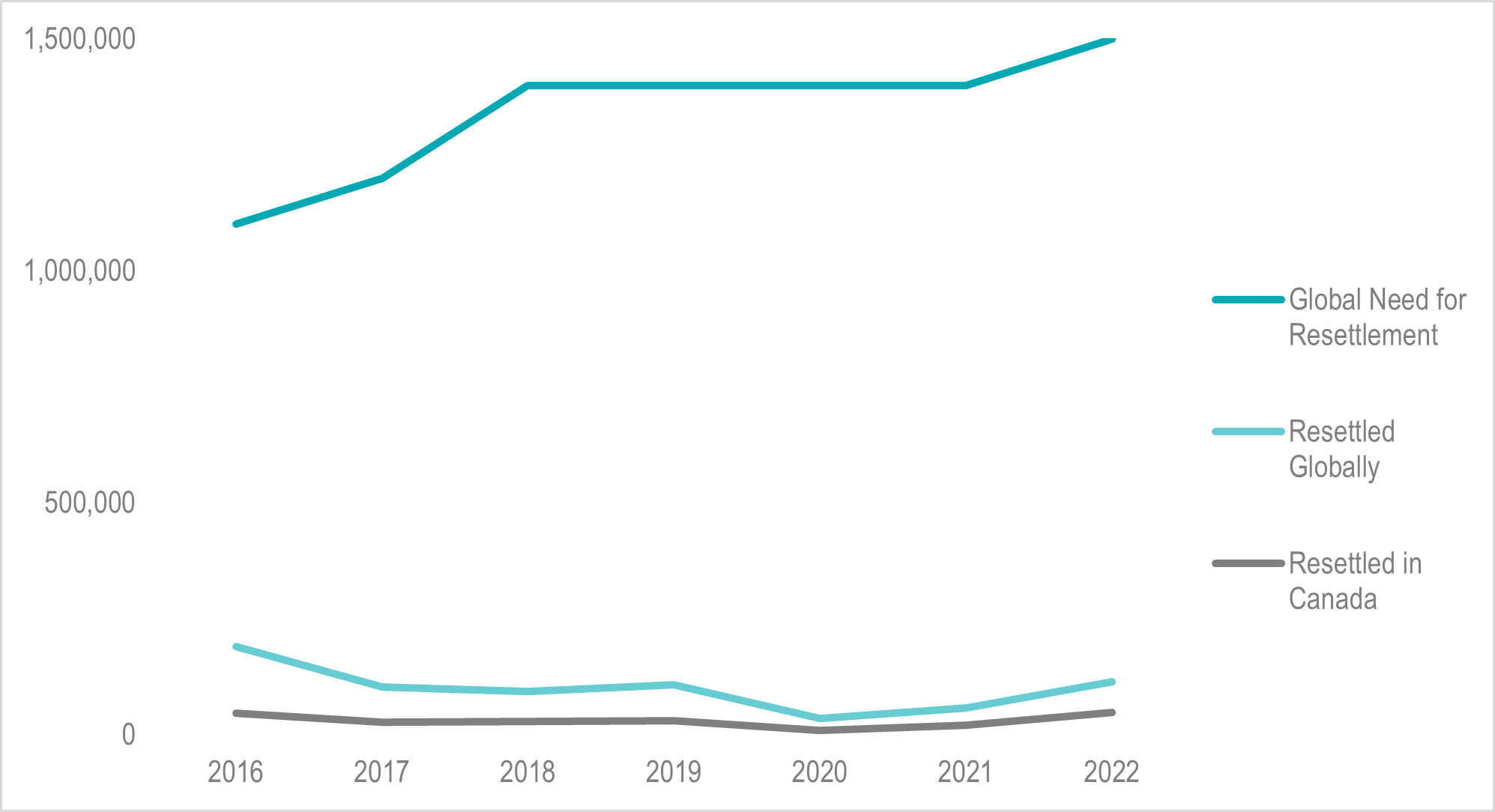

Some interviewees noted Canada is a global leader in resettlement. Between 2016 and 2022, Canada received the most or the second-most resettled refugees of all countries each year, representing between 25% to 42% of all resettled refugees globally annually. It was also highlighted that Canada receives a large number of high-needs refugees and has a strong relationship with the UNHCR.

Global Need for Resettlement

Document review and interviewees noted that the Resettlement Program is needed to address growing global resettlement needs. The UNHCR estimated that in 2022, there were 35.3 million refugees worldwide, of which 1.5 million were in need of resettlement, a large increase from 1.1 million in need of resettlement in 2016.Footnote 7 Despite the growing need, only about 5% of those in need of resettlement are resettled each year.

Figure 4: Refugees Resettled vs Global Need for Resettlement (GCMS, UNHCR)

Figure 4

The figure presents a line graph depicting three trends in absolute numbers between 2016 and 2022; the global need for resettlement, the number of refugees resettled globally, and the number of refugees resettled in Canada. The figure presents the following data points for global need for resettlement: 2016: 1,100,000; 2017: 1,200,000; 2018: 1,400,000; 2019: 1,400,000; 2020: 1,400,000; 2021: 1,400,000; 2022: 1,500,000. The figure presents the following data points for the number of refugees resettled globally: 2016: 189,300; 2017: 102,800; 2018: 92,400; 2019: 107,800; 2020: 34,400; 2021: 57,500; 2022: 114,300. The figure presents the following data points for the number or refugees resettled in Canada: 2016: 46,700; 2017: 26,600; 2018: 28,100; 2019: 30,100; 2020: 9,200; 2021: 20,400; 2022: 47,600.

Rationale for Program Streams

Interviewees felt that all program streams (GAR, PSR, and BVOR) were valuable and contributed to the overall objectives of the Resettlement Program, with some describing the streams as having different but complementary priorities.

GAR Stream

Document review and interviewees highlighted that the GAR stream prioritized the most vulnerable refugees, as identified by the UNHCR or other referral organizations. Interviewees described the GAR stream as Canada’s ‘conventional’ resettlement stream, and felt that the stream was strongly aligned with both the UNHCR and IRPA mandates.

PSR Stream

Document review and interviewees highlighted that in addition to providing protection, the PSR stream contributed to better settlement outcomes and family reunification, as sponsorships are often family-linked and can provide wider support networks for refugees. Document review and interviewees noted that private sponsorship also allows Canadians to become directly involved in refugee resettlement and increases the number of protection spaces.

Some interviewees highlighted that Canada’s PSR model was being emulated in other countries and that Canada plays an important role in global capacity-building for private sponsorship through the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative (GRSI). Interviewees felt that the PSR stream was valuable in promoting and increasing refugee protection globally, as well as within Canada.

BVOR Stream

The BVOR stream was introduced in 2013 as a cost-saving initiative to retain protection spaces while decreasing the cost to the GOC in supporting GARs. Consistent with the findings of the BVOR evaluation (2021), the objectives of the BVOR stream were found to evolve over time to allow the most vulnerable refugees to benefit from tailored sponsorship supports, and allow sponsors to more easily respond to global refugee crises.Footnote 8

While some interviewees felt that the BVOR stream nicely combined the benefits of the GAR and PSR streams, document review and some interviewees highlighted challenges – noting, for example, that BVOR has had low uptake and some felt it no longer saved costs as designed. IRCC has implemented multiple incentive initiatives to increase BVOR uptake, to mixed success.

BVOR uptake remained low in 2022, and some interviewees felt there was a need to review the BVOR stream objectives to enhance the number of protection spaces used.

Figure 5: Refugee Admissions by Stream, 2016 – 2022 (GCMS)

Figure 5

The figure presents a pie chart showing the distribution of refugee admissions by stream, over the period of 2016 to 2022. The figure presents the following data points: PSRs: 53%; GARs: 43%; BVORs: 4%.

Program Objectives

Finding 2: The Resettlement Program is being used to address evolving humanitarian objectives. While public policies support IRCC’s ability to respond to crises, this has come at the expense of traditional resettlement objectives.

Traditional Refugee Resettlement

To be resettled in Canada as a refugee, individuals must be referred by either a referral organization (e.g., UNHCR) or a private sponsorship group, and fall into one of Canada’s two refugee classes:

Convention Refugees Abroad Class

- Are outside their home country; and

- Cannot return there due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on: race, religion, political opinion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group.

Country of Asylum Class

- Are outside their home country, of the country where they normally live; and

- Have been seriously affected by civil war or armed conflict, or massive violation of human rights on an ongoing basis.

Evolving Humanitarian Objectives

However, IRPA s25.2(1) allows the Minister to grant permanent residence status or exemptions from eligibility criteria, for example, by waiving traditional resettlement criteria through public policies.Footnote 9

Document review and interviewees noted that public policies have been used more frequently in recent years for populations that do not meet Canada’s resettlement requirements, for example, by waiving the requirement that populations be outside their home country. This exemption has allowed GOC to grant protection to populations that have been unable to leave their home country due to unfolding humanitarian crises, such as in the Survivors of Daesh initiative. As well, the program contributed to resettling over 40,000 Afghans between 2021 and 2023, meeting a GOC humanitarian commitment.

Interviewees felt that, while public policies allow Canada to respond to emerging humanitarian crises and foreign policy objectives, their use comes at the expense of traditional resettlement objectives.

Public Policy Challenges

Challenges with Objectives

Some interviewees felt that the Resettlement Program was being used to achieve objectives for which it was not designed, creating confusion over who is eligible for refugee resettlement and services. Interviewees also noted that using public policies in refugee resettlement was resource-intensive.

Some felt that the use of public policies indicated misalignment between the refugee definition outlined in IRPA and Canada’s public commitments on humanitarian crises, expressing either that the refugee criteria in IRPA is too restrictive to accommodate evolving objectives or that public commitments are not aligned with regulations.

Interviewees expressed that there is a need to respond to evolving humanitarian crises while also protecting traditional resettlement programs and inventories. As of 2024, work on a Crisis Response Framework was underway at IRCCFootnote 10 .

Challenges with Equity

Document review and interviewees noted perceived inequity in waiving criteria for only certain populations and that these populations benefit from more timely processing and protection at the expense of the existing resettlement inventory.

This inequity was noted to negatively impact engagement with external stakeholders, who expressed concern that some populations may receive preferential treatment through the use of public policies.

Governance

Finding 3: The complex governance structure and a lack of clarity of internal roles and responsibilities have complicated coordination in the Resettlement Program and have negatively impacted relationships with external stakeholders.

Complex Governance

Over the years, internal evaluations, audits, stocktakes and memos have consistently highlighted challenges related to governance of the Resettlement Program. Despite efforts to improve governance in 2021, such as creating new branches and an internal governance board, half of interviewees felt that governance remained a key challenge.

Interviewees noted that the Resettlement Program governance is fragmented across multiple IRCC sectors and numerous IRCC branches, creating a lack of coordination between internal stakeholders. In particular, document review and interviewees noted the following governance challenges:

- Some interviewees felt there was a lack of coordination between policy and operations branches;

- Document review and interviewees noted that the creation of the Afghanistan Sector and corresponding Afghan branches further fragmented resettlement governance;

- Some interviewees expressed that the 2021 departmental re-organization only increased complexity; and

- Some interviewees felt there was a lack of cohesion and coordination between Resettlement branches and Settlement branches.

Internal Roles and Responsibilities

A lack of clarity on roles stemming from complex governance was cited by interviewees. who expressed confusion on responsibilities for functional guidance, policy implementation, stakeholder engagement, and the RAP.

Document review also found a similar lack of clarity, with internal documents often showing inaccurate, outdated, or contradictory information on roles and responsibilities. Due to the complexity of and frequent changes to the Resettlement Program governance, the evaluation was unable to determine a comprehensive timeline of changes to roles and responsibilities. For example, authority over the RAP was transferred between branches multiple times within the scope period, and document review and interviewees held conflicting views of who held authority over the RAP at the time of the evaluation.

Interviewees also described internal coordination challenges resulting from complex governance and unclear roles, including:

- A lack of working-level communication between branches, despite greater coordination at the senior management level;

- Delayed or erred communication between stakeholders, including on Notice of Arrival Transmissions (NATs), refugee documents, and internal inquiries; and

- Data reporting issues, including on sponsorship allocations.

In particular, coordination challenges with Global Network (GN) migration offices were noted.

External Engagement

In addition to negatively impacting internal coordination, interviewees felt that governance challenges had negatively affected IRCC’s engagement with external stakeholders, and with sponsors in particular. It was noted that internal coordination issues hindered IRCC’s ability to communicate the number of available sponsorship allocation spaces to SAHs, putting them at risk for under- or over-submitting cases, potentially leading to penalties for the SAH, as well as loss of resettlement spaces.

Interviewees also noted that the program relies heavily on external partners, but that frequent changes to Resettlement Program governance made it more difficult for external partners to contact and coordinate with IRCC, for example, when a point of contact is moved.

Timeliness of Protection

Finding 4: The resettlement program offers timely protection to refugees when cases are prioritized; however, prioritization of certain groups contributes to inequitable access overall.

Processing Efficiency

Interviewees felt that processing was efficient, citing that targets are met consistently as per levels planning. Administrative data showed that targets have been met, with the exception of years impacted by COVID-19 travel restrictions. However, document review and interviewees highlighted some processing challenges, including:

- Lack of intake management on PSR applications for CS and G5 sponsors, as applications received outpace annual levels space, resulting in growing inventory and wait times;

- Lack of information technology investment for the digital intake of application referrals and a reliance on paper-based files and email, as this was noted to be time-consuming and raise privacy concerns for application information;

- Mission-specific processing, as applications processed at under-resourced missions were subject to much longer processing times; and

- Errors with processing some PSR applications, including some sponsorship applications being received but not provided an IRCC file number.

At the time of the evaluation, work was underway to increase processing efficiency, including the implementation of digital intake.

Processing Timeliness

To date there are no service standards for processing refugees. However, nearly half of interviewees felt the program does not provide timely protection overall.

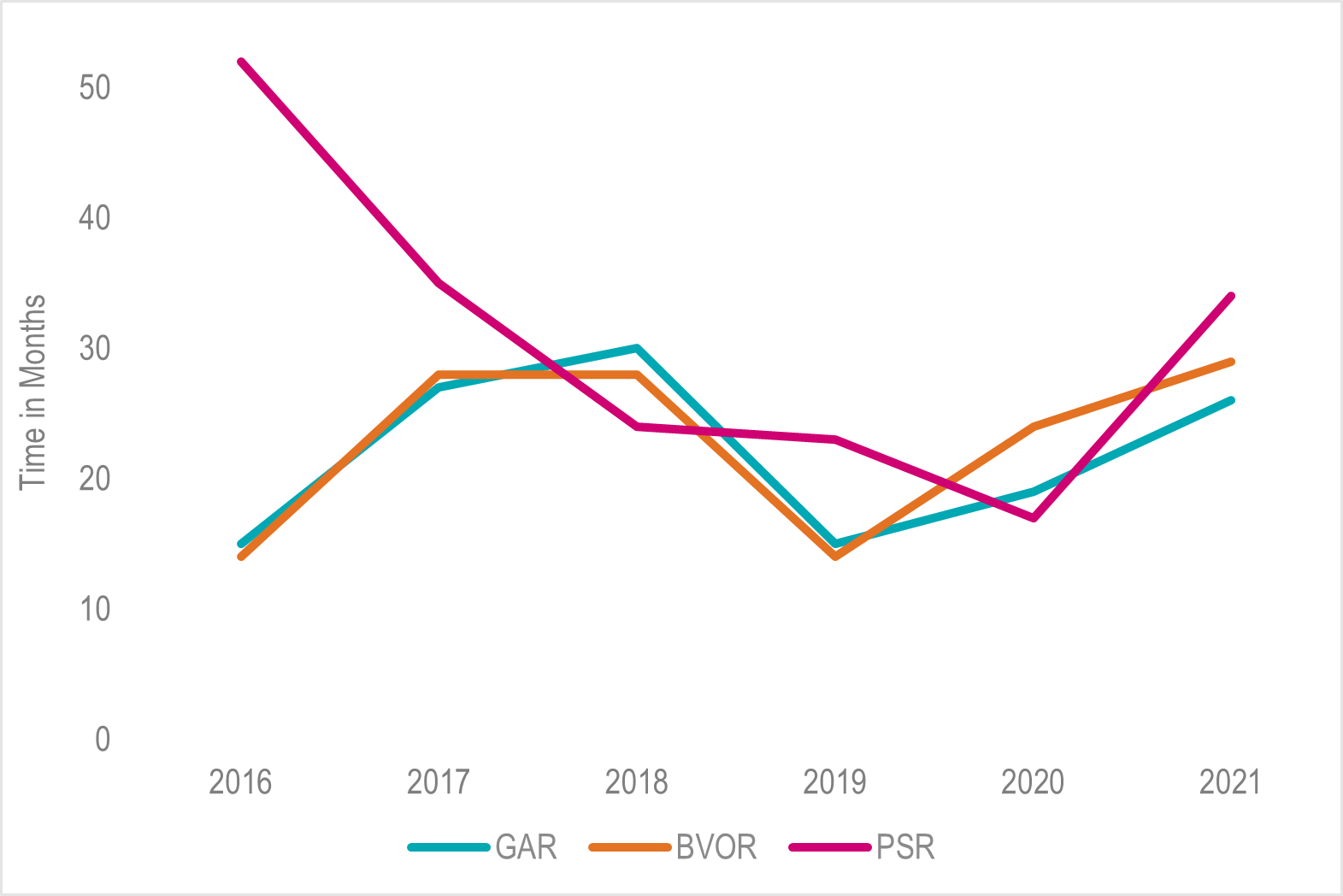

IRCC uses an “80th percentile decision period” to report on refugee processing time, representing the time it takes for 80% of applications to be finalized, from receipt to final decision, expressed in months. From 2016 to 2021, the 80th percentile decision period ranged from 18 to 32 months.

As of July 22, 2022, there were 103,968 refugee applications in the application inventory, of which two thirds were PSRs (69%). Only 3% were received before 2018, indicating that wait times exceeding five years are rare.

Figure 6: Processing Time of Refugee Applications by Stream, 80th Percentile Decision Period (GCMS)

Figure 6

The figure depicts a line graph showing the 80th percentile decision period processing time of refugee applications in month by stream and by year, from 2016 to 2021. The figure presents the following data points for BVORs: 2016: 14 months; 2017: 28 months; 2018: 28 months; 2019: 14 months; 2020: 24 months; 2021: 29 months The figure presents the following data points for GARs: 2016: 15 months; 2017: 27 months; 2018: 30 months; 2019: 15 months; 2020: 19 months; 2021: 26 months. The figure presents the following data points for PSRs: 2016: 52 months; 2017: 35 months; 2018: 24 months; 2019: 23 months; 2020: 17 months; 2021: 34 months..

Inequitable Processing

Resettlement applications are intended to be processed in a first-in-first-out basis, following the immigration levels plan. However, processing for certain groups may be prioritized based on Ministerial commitments (e.g., public policies), vulnerability as identified by migration offices (e.g., Women at Risk), or partner recommendations (e.g., UNHCR emergency referrals).

Document review and GCMS data showed that prioritized processing allows the GOC to offer timely protection and meet humanitarian objectives. For instance, prioritized processing during OSR and the humanitarian program for Afghan nationals granted Syrian and Afghan refugees more timely protection:Footnote 11

- Syrian refugees waited sixteen months in 2016 during OSR, but more than five years in 2021; and

- In 2021, processing time for Afghan refugees was reduced to one month, compared to between five and seven years from 2016 to 2019.

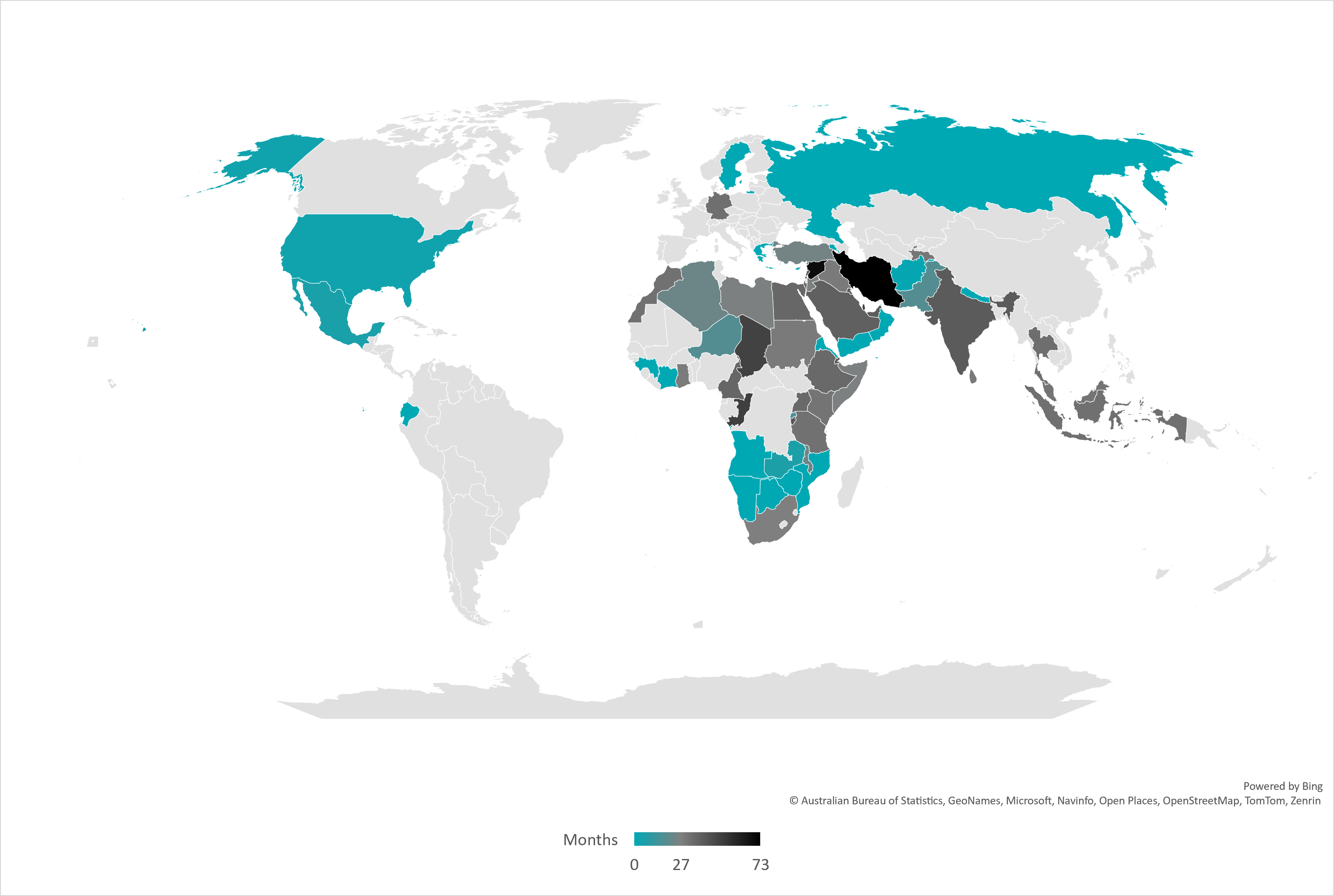

Conversely, non-prioritized groups often wait significantly longer. In some countries, the 80th percentile decision period exceeded nine years during the evaluation period.

Academic literature noted that prolonged displacement has negative impacts on refugees’ mental health and ability to adapt or recover from stressful and traumatic events, suggesting that lengthy processing times will have negative impacts on the longer-term independence and integration goals of the Resettlement Program. Notably, IRCC processing times do not include the time that refugees spend journeying to their country of asylum or waiting to receive their Refugee Status Determination (RSD) or referral.

Figure 7: Processing Time of Refugee Applications in 2021 by Country of Residence, 80th Percentile Decision Period (GCMS)Footnote 12

Figure 7

The figure presents 2021 processing time in months, by country of residence, using the 80th percentile decision period. The figure presents the following data: Afghanistan: 1 months; Algeria: 23 months; Angola: 0 months; Armenia: 0 months; Botswana: 0 months; Burundi: 42 months; Cameroon: 36 months; Chad: 49 months; Cyprus: 0 months; Djibouti: 39 months; Ecuador: 0 months; Egypt: 36 months; Eritrea: 0 months; Ethiopia: 35 months; Germany: 33 months; Ghana: 28 months; Greece: 0 months; Guinea: 0 months; India: 40 months; Indonesia: 32 months; Iran: 73 months; Iraq: 29 months; Israel: 35 months; Ivory Coast: 0 months; Jordan: 27 months; Kenya: 31 months; Kuwait: 42 months; Lebanon: 44 months; Libya: 26 months; Malawi: 24 months; Malaysia: 31 months; Mexico: 5 months; Morocco: 32 months; Mozambique: 0 months; Namibia: 0 months; Nepal: 0 months; Niger: 18 months; Oman: 0 months; Pakistan: 18 months; Qatar: 49 months; Republic of the Congo: 50 months; Russia: 0 months; Rwanda: 16 months; Saudi Arabia: 38 months; Somalia: 27 months; South Africa: 27 months; Sri Lanka: 29 months; Sudan: 29 months; Sweden: 0 months; Syria: 69 months; Tajikistan: 30 months; Tanzania: 32 months; Thailand: 33 months; Turkey: 25 months; Uganda: 35 months; United Arab Emirates: 40 months; United States: 3 months; Yemen: 0 months; Zambia: 6 months; Zimbabwe: 0 months.

Interviewees noted that public policies and mass arrivals of refugees negatively impact application processing and inventory, as they divert resources from traditional refugees. For example, document review found that the 2021 Afghan commitment was expected to delay one year’s worth of processing for the regular inventory, or about 13,500 refugee cases, over three years.

Some key informants felt this diversion of resources hurts IRCC’s engagement with sponsors, refugees and the general public.

Supports and Meeting Needs

Finding 5: Overall, the Resettlement Program is meeting refugees’ immediate and essential needs; however GARs, LGBTQ2 refugees, and individuals with disabilities experience challenges in having their needs met.

Notice of Arrival Transmissions (NAT)

After the refugee’s application has been approved, GN sends a NAT to the POE SPO and the local IRCC office. The NAT includes information about the refugee’s expected arrival and any special needs that may require additional attention upon arrival. NATs should be sent at least 10 business days before the expected arrival.

Interviewees highlighted challenges with the comprehensiveness and timeliness of NATs. In particular, it was noted that as a result of privacy concerns, NATs often do not include refugees’ medical information, resulting in some refugees arriving in Canada with serious and unknown medical issues. Some interviewees felt that not providing this information in advance hindered RAP SPOs and sponsors from meeting refugees’ immediate and essential needs.

While acknowledging that refugee travel-readiness can be unpredictable due to external factors, some interviewees expressed that the 10 business day service standard for NATs does not give sponsors enough time to prepare. Document review and interviewees noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, a ‘pre-NAT’ would be sent to sponsors months in advance of arrival, but that this process was no longer being used.

Port of Entry Supports

Once a refugee arrives in Canada, the POE SPO is responsible for meeting the refugee at the airport, assisting with immigration and customs procedures, and ensuring that the refugee is transported to their final destination or met by a RAP SPO or sponsor at the airport. Between October 15 and April 15, POE SPOs must also provide GARs with winter clothing.

Between 2016 and 2022, 147,498 unique POE services were provided. Survey results suggested the almost all refugees were met at the airport (95%) by somebody who was able to communicate with them (93%) and were provided transportation to temporary accommodations (89%). While some refugees felt they needed winter clothing at the POE but did not receive them (30%), internal policies advise that clothing allowances may be provided instead.

Start-Up Supports

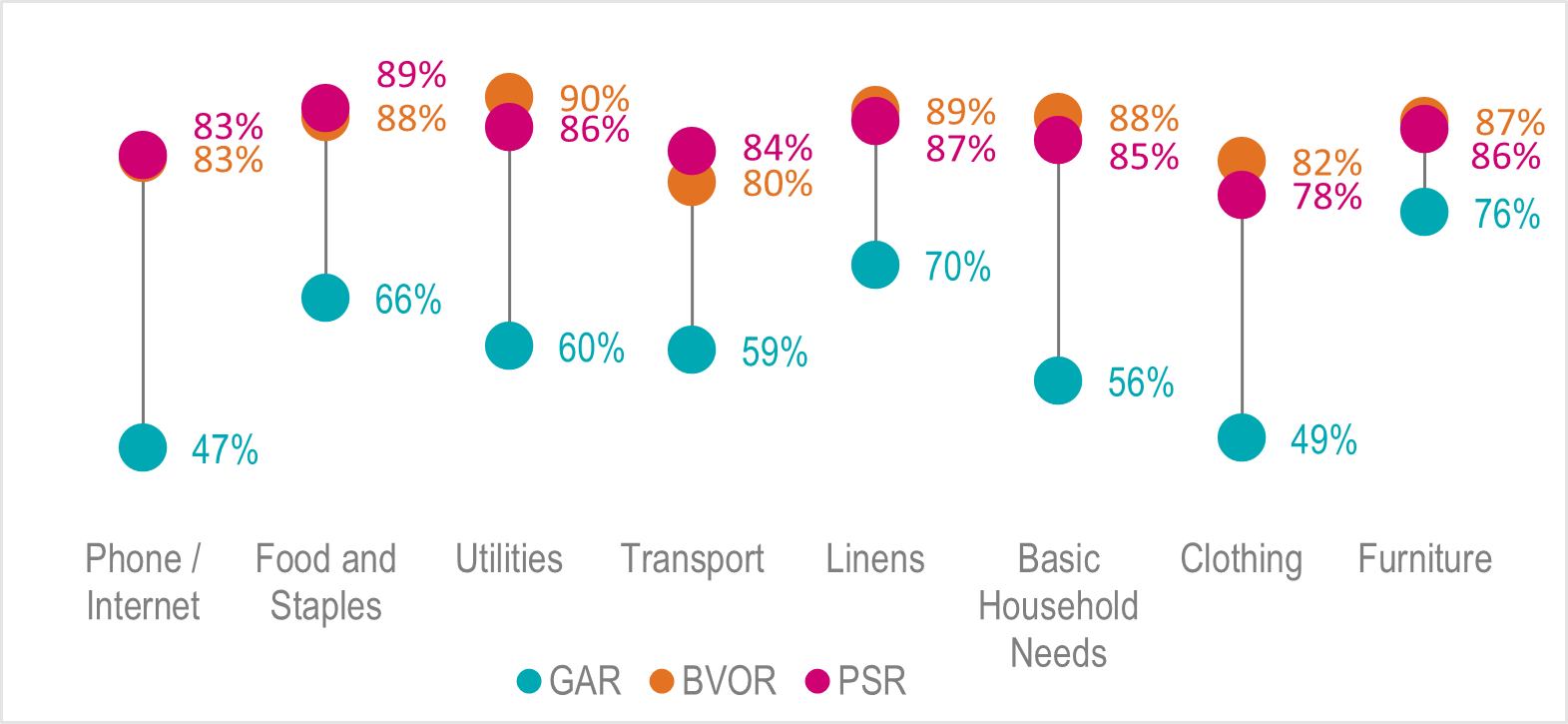

After arriving in Canada, once in permanent accommodation, refugees receive in-kind or financial supports to cover start-up needs like linens, clothing, furniture, and utilities. RAP SPOs are responsible for teaching refugees about start-up supports and for ensuring that various immediate and essential supports are received. Sponsors are responsible for ensuring that BVOR and PSR needs are met.

The majority of surveyed refugees reported they received supports in their first weeks and that their needs were met by these supports, across different categories. A smaller share of GARs said they received start-up supports compared to sponsored refugees. Stakeholders noted that as GARs do not receive some start-up supports until after finding permanent accommodations, the disparity between government-assisted and sponsored refugees may indicate delays in GARs receiving supports.

Figure 8: Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Receiving Start-Up Supports

Figure 8

The figure presents a lollipop chart depicting the proportion of surveyed refugees who reported having received start-up supports, by support type and by refugee type. In general, the figure shows a deficit between the proportion of GARs to report having received supports, compared to BVORs and PSRs. The figure presents the following data points for GARs: Phone/Internet: 47%; Food and Staples: 66%; Utilities: 60%; Transport: 59%; Linens; 70%; Basic Household Needs: 56%; Clothing: 49%; Furniture: 76%. The figure presents the following data points for BVORs: Phone/Internet: 83%; Food and Staples: 88%; Utilities: 90%; Transport: 80%; Linens; 89%; Basic Household Needs: 88%; Clothing: 82%; Furniture: 87%. The figure presents the following data points for PSRs: Phone/Internet: 83%; Food and Staples: 89%; Utilities: 86%; Transport: 84%; Linens; 87%; Basic Household Needs: 85%; Clothing: 78%; Furniture: 86%.

Among refugees who did report receiving start-up supports in their first weeks, GARs had less positive views of how well these supports met their needs compared to PSRs and BVORs, suggesting that a lower share of GARs have their needs met in their first weeks even when accounting for delays in service provision.

Figure 9: Surveyed Refugees Who Reported Having “All” or “Most” of Their Start-Up Needs Met

Figure 9

The figure presents a lollipop chart depicting the proportion of surveyed refugees who reported having “all” or “most” of their start-up needs met, by support type and by refugee type. In general, the figure shows a deficit between the proportion of GARs to report having “all” or “most” of their needs met compared to BVORs and PSRs. The figure presents the following data points for GARs: Phone/Internet: 78%; Food and Staples: 76%; Utilities: 75%; Transport: 74%; Linens: 67%; Basic Household Needs: 65%; Clothing: 62%; Furniture: 60%. The figure presents the following data points for BVORs: Phone/Internet: 92%; Food and Staples: 92%; Utilities: 91%; Transport: 92%; Linens: 91%; Basic Household Needs: 91%; Clothing: 86%; Furniture: 92%. The figure presents the following data points for PSRs: Phone/Internet: 95%; Food and Staples: 95%; Utilities: 95%; Transport: 94%; Linens: 94%; Basic Household Needs: 93%; Clothing: 93%; Furniture: 92%.

Timeliness and Responsiveness

Nearly all refugees felt that the services they received in their first weeks, whether from a SPO or a sponsor, were timely, responsive and tailored to their needs and situation, and available for as long as they were needed. Likewise, most surveyed RAP SPOs and sponsors reported no major issues supporting refugees’ immediate and essential needs. For example, few RAP SPOs reported any challenges delivering needs assessments, providing referrals (e.g., to language training, case management), orientation services, or making connections to federal/provincial programs.

Informational Needs and Supports

RAP SPOs and sponsors provide information to help refugees understand what they need to know in their first weeks in Canada, including such topics as their community/city, finance, employment, schools and healthcare.

Most surveyed refugees reported needing help with these topics, and need for support was highest among GARs (63%) and BVORs (62%) compared to PSRs (53%).Footnote 13 Most surveyed refugees who reported needing these supports received them, and felt the supports met their needs. However, the share of GARs who reported services met their needs was lower than that of sponsored refugees.

As part of immediate and essential orientation, RAP SPOs are asked to teach clients about different social and cultural topics, such as linguistic duality, human rights and multiculturalism. In these subjects, a smaller share of PSRs (who do not receive RAP services) reported having learned about these subjects.

Settlement Services

Beyond meeting immediate needs, RAP SPOs and sponsors must also assist refugees with learning about and accessing settlement services, such as language training, client support services, and other longer-term supports.

The refugee survey found that, while awareness of language training classes was high, awareness of other settlement services was relatively low. A greater share of GARs (51%) and BVORs (57%) were aware of services compared to PSRs (43%).Footnote 14 Literature review and interviewees also highlighted concerns that awareness of settlement supports may be lower among PSRs.

Despite not all refugees being aware of the breadth of available services, the majority reported receiving the services they needed. The most common services that were needed but not received were for help searching for and finding jobs (57%) and linkages to other community services (53%). The most common barriers to accessing services were not knowing where/how to get services (33%), needing to work (25%), and lack of transportation (22%). These barriers were likewise identified in the academic literature.

Challenges and GBA+ Groups

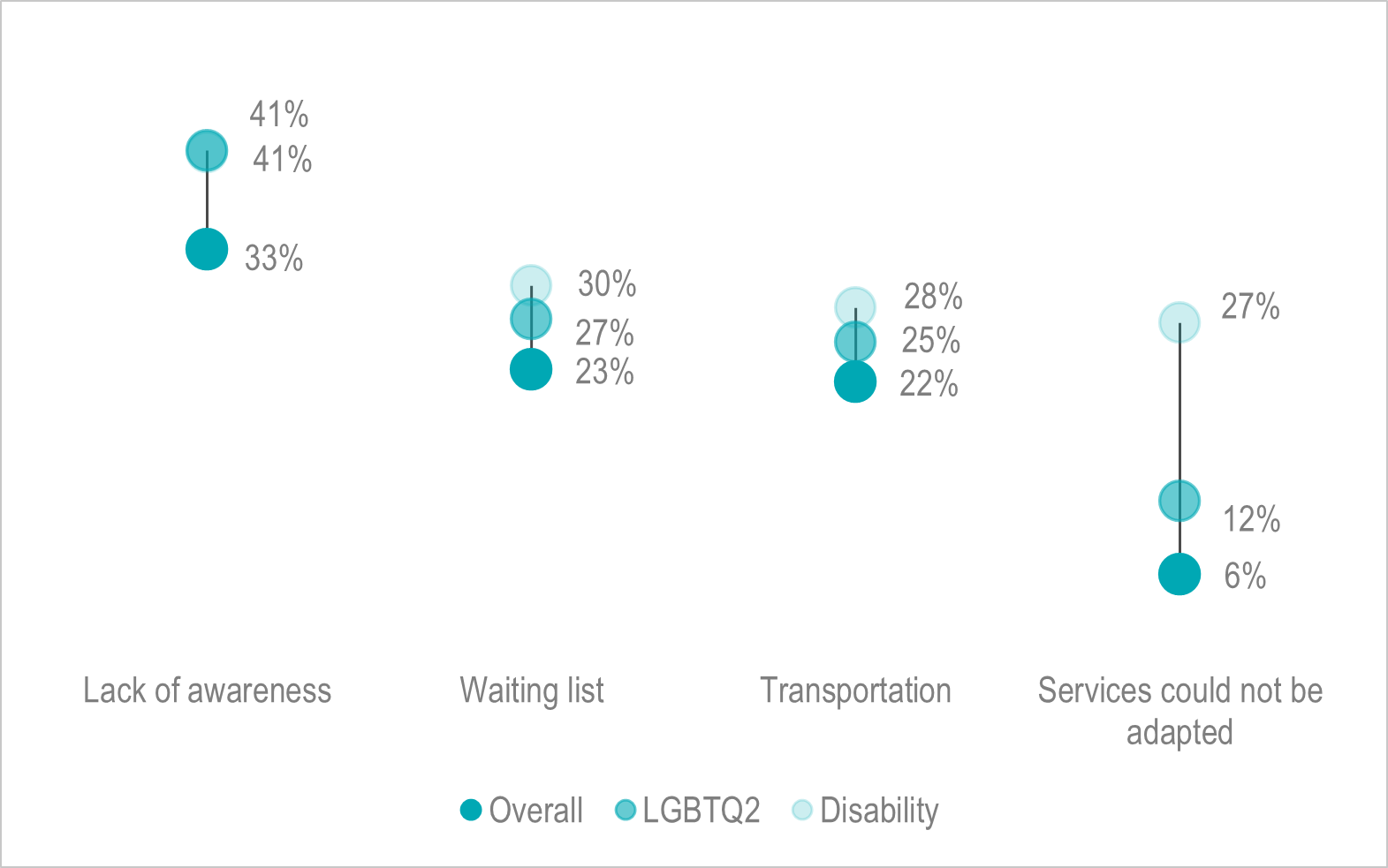

The evaluation found that certain groups of refugees, including Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2) refugees; refugees with disabilities; and to a lesser extent, women, experience challenges in having their immediate needs met.

Document review and interviews noted that women may face additional barriers to accessing settlement services and employment due to childcare responsibilities and gender norms. The refugee survey found no major differences between self-identified women and men across all needs. However, refugees who identified with more than one gender had more need for services, less access to services, and less needs met overall.

Literature review suggested LGBTQ2 refugees face barriers based on discrimination, including challenges in accessing information related to LGBTQ2 services and communities in Canada, as well as social isolation. Interviewees noted that LGBTQ2 refugees may face discrimination in accessing services, and may experience barriers in building wider support networks.

Document review and interviews also identified barriers to addressing needs of refugees with disabilities, for example, SPOs and sponsors may lack capacity to meet specialized information needs, or to provide referrals for specialized services (e.g., healthcare). Lack of accessible transport was also stressed as a key barrier for those with disabilities, which further impeded access to other services.

In general, the refugee survey found that although access to services was similar overall, a greater share LGBTQ2 refugees and of refugees with disabilities reported facing challenges in accessing services in their initial weeks in Canada.

Figure 10: Share of Surveyed Refugees Across GBA+ Groups Who Reported Experiencing Barriers in Accessing Supports

Figure 10

The figure presents a lollipop chart depicting the proportion of surveyed refugees to report having experienced barriers in accessing supports, by support type, broken down by refugees overall, LGBTQ2 refugees and refugees who reported having a disability. In general, the chart shows a deficit between LGBTQ2 refugees and refugees who reported having a disability, compared to refugees overall. The figure presents the following data points for refugees overall: Lack of awareness: 33%; Waiting list: 23%; Transportation: 22%; Services could not be adapted: 6%. The figure presents the following data points for LGBTQ2 refugees: Lack of awareness: 41%; Waiting list: 27%; Transportation: 25%; Services could not be adapted: 12%. The figure presents the following data points for refugees who reported having a disability: Lack of awareness: 41%; Waiting list: 30%; Transportation: 28%; Services could not be adapted: 27%.

Housing

Finding 6: Lack of availability of permanent housing and extended stays in temporary housing are primary challenges for timely and consistent delivery of RAP services and supports.

Temporary Housing

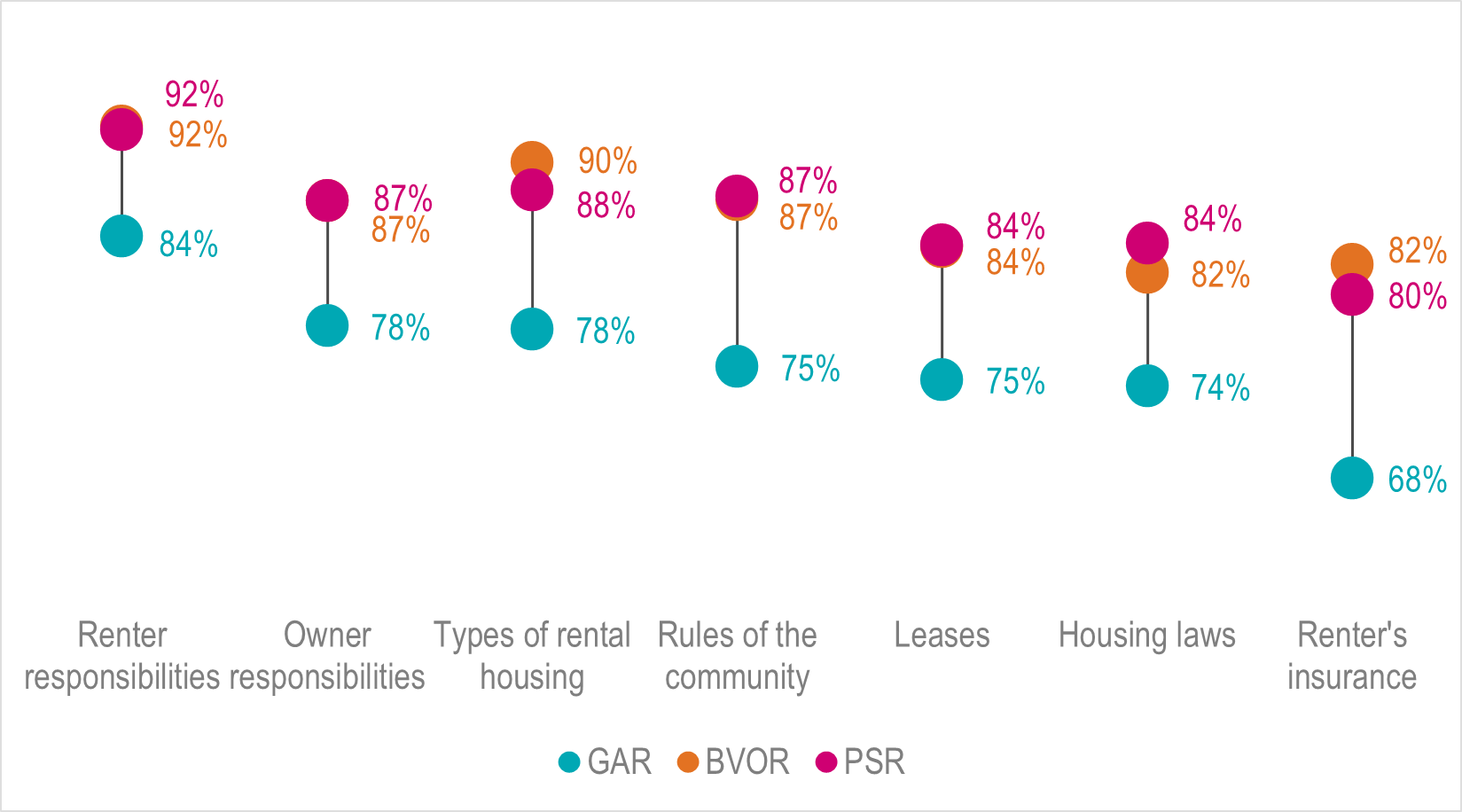

Once a refugee arrives in Canada, the RAP SPO or sponsor is responsible for providing temporary accommodations until permanent housing is secured. Temporary accommodations may include a reception house, hotel, rented or other housing, and should be centrally located (e.g., easy access to public transportation, SPO premises, grocery stores). In addition, the RAP SPO or sponsor should provide the refugee with information on housing, such as information on renting, leases, and paying utilities.