Evaluation of Migration Health Programming

Evaluation Division

October 2024

Executive Summary

Background

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Migration Health Programs. The evaluation was conducted in fulfillment of the requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on Results and covered the fiscal years (FY) 2015/16 to 2022/23.

The objective of the evaluation was to assess the performance of IRCC’s migration health programs, as well as contributions towards the achievement of associated program outcomes.

IRCC’s health programming consist of three primary health programs: health screening, medical surveillance and notification and the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP). Together the three programs aim to facilitate the entry of newcomers while protecting the health, safety and security of Canadians.

Summary of Findings

The evaluation found that there was a continued need to screen migrants for communicable diseases, to monitor those who have latent tuberculosis (LTBI) and provide healthcare coverage for refugees and asylum seekers. Overall, the programs were effectively managed and delivered and were flexible and adaptable. However, governance suffered from some gaps in communication and coordination between MHB and some internal and external health partners.

The health screening program operated efficiently, however there are opportunities to streamline the Immigration Medical Exam (IME) and to increase the screening for LTBI. Challenges in data sharing and communication between Provinces/Territories (P/Ts) and MHB hindered the tracking of program outcomes and the assessment of the surveillance and notification program's effectiveness. IFHP met its objectives, however clients experienced challenges in accessing some services.

Recommendations

In response to the findings, and in support of the continued improvement of the program, the following recommendations are proposed:

- 1) IRCC should identify specific areas with internal and external partners where communication can be strengthened and implement strategies/processes where applicable.

- 2A) IRCC should develop and confirm the definition, objectives, and role of continuity of care within migration health programming;

- 2B) Contingent on recommendation 2A, IRCC should develop an approach to enable monitoring and reporting on continuity of care-related activities and outcomes.

- 3A) IRCC should develop key measures to monitor the impact of IRCC’s Surveillance and Notification Program.

- 3B) IRCC should identify and implement means to strengthen surveillance program collaboration and information-sharing with P/Ts.

- 4) IRCC should complete a review of the benefits and risks of streamlined IMEs and protocols for LTBI screening and implement applicable changes.

Management Response Action Plan (MRAP)

Recommendation 1: IRCC should identify specific areas with internal and external partners where communication can be strengthened and implement strategies/processes where applicable.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation

IRCC recognizes the value of formal communication and has been focusing efforts to support stakeholder engagement on operational aspects of migration health programming to strengthen partner communications. In support of these efforts, IRCC will conduct an inventory of current engagement to identify communication gaps, and determine the most efficient processes for engagement while ensuring reciprocity.

| Actions | Accountability | Completion date |

|---|---|---|

IRCC will conduct an inventory of current engagements to identify gaps and efficiencies for improved collaboration with federal and P/T partners and stakeholders. |

MHB | Q2 2025-2026 |

Recommendation 2:

- IRCC should develop and confirm the definition, objectives, and role of continuity of care within migration health programming;

- Contingent on recommendation 2a, IRCC should develop an approach to enable monitoring and reporting on continuity of care-related activities and outcomes.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation

In recent years, IRCC has been exploring ways to improve client service, health outcomes and integration into the healthcare system. Further to these efforts, IRCC will articulate how the concept of continuity of care can be integrated into migration health programming. Contingent on the agreed upon definition, IRCC will outline an approach for reporting on activities and outcomes related to continuity of care.

| Actions | Accountability | Completion date |

|---|---|---|

| IRCC will further define continuity of care within the current legal and regulatory framework, and identify authorities needed to consider expanding activities in future. | Lead: MHB Support: LSU, APMB, SIP, MASB, RPB |

Q4 2025-2026 |

| Contingent on agreed upon definition and authorities needed for continuity of care, IRCC will report on qualitative/quantitative outcomes of IFHP. | MHB | Q4 2026-2027 |

Recommendation 3:

- IRCC should develop key measures to monitor the impact of IRCC’s Surveillance and Notification Program.

- IRCC should identify and implement means to strengthen surveillance program collaboration and information-sharing with P/Ts.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation

To track key operational and outcome indicators, IRCC will develop an Indicator Framework to monitor TB surveillance and to support consistent reporting against indicators. IRCC will review outcomes from ongoing analysis of LTBI screening protocols to gauge impact across the cascade of care. Furthermore, IRCC will collaborate with P/Ts to implement changes which will optimize surveillance referral processes and increase efficiency of information-sharing with P/Ts.

| Actions | Accountability | Completion date |

|---|---|---|

| IRCC will develop an Indicator Framework to monitor TB surveillance volumes and trends and to support routine reporting against indicators. | MHB | Q2 2025-2026 |

| IRCC will review outcomes from ongoing analysis of enhanced LTBI screening protocols. | MHB | Q2 2025-2026 |

| IRCC will collaborate with P/Ts to optimize surveillance referral processes and to increase efficiency of information-sharing with P/Ts. | Lead: MHB Support: IGRE, LSU, APMB, IOB, HIOB, IP, CSE |

Q4 2025-2026 |

Recommendation 4: IRCC should complete a review of the benefits and risks of streamlined IMEs and protocols for LTBI screening and implement applicable changes.

Response: IRCC agrees with this recommendation

IRCC launched the streamlined Immigration Medical Exam (IME) in 2023 as a lighter-touch screening option during certain urgent operational situations (e.g., humanitarian crisis). IRCC will assess the impact of the implementation of the streamlined IME, from which benefits and risks identified will be used to inform applicable changes to subsequent phases of screening modernization.

As health screening is a key component of Canada’s immigration process, IRCC acknowledges that identifying LTBI and preventing TB reactivation is important. IRCC will collaborate with P/Ts and M5 partners to review the risks, benefits, feasibility and capacity for enhanced LTBI screening.

| Actions | Accountability | Completion date |

|---|---|---|

| IRCC will assess the impact of the implementation of the Streamlined IME and will make course corrections as indicated for implementation of subsequent phases of screening modernization. | MHB | Q2 2025-2026 |

| IRCC will continue to engage with M5 partners to review the risks and benefits of existing enhanced LTBI screening protocols. IRCC will also engage internally and with P/Ts to determine healthcare capacity and feasibility for implementation. | MHB | Q2 2026-2027 |

List of Acronyms

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- HC

- Health Canada

- HIV

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IFHP

- Interim Federal Health Program

- IGRA

- Interferon Gamma Release Assay

- IME

- Immigration Medical Exam

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- LTBI

- Latent Tuberculosis Infection

- M5

- Migration Five

- MHB

- Migration Health Branch

- MRAP

- Management Response Action Plan

- PDMS

- Pre-Departure Medical Services

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PR

- Permanent Resident

- P/T

- Province/Territory

- RAP

- Resettlement Assistance Program

- RMO

- Regional Medical Office

- RPB

- Resettlement Policy Branch

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- TB

- Tuberculosis

- TR

- Temporary Resident

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response Action Plan (MRAP)

- List of Acronyms

- List of Tables and Figures

- Evaluation Background and Context

- Methodology

- Methodological Considerations, Limitations and Mitigations

- Program Profile

- Need for Migration Health Programming: Health Screening

- Need for Migration Health Programming: Surveillance and Notification Program

- Need for Migration Health Programming: Interim Federal Health Program

- Governance and Management with International and Canadian Health Partners

- Governance and Management with Internal Partners

- Program Effectiveness: Health Screening

- Program Effectiveness: Health Screening

- Program Effectiveness: Surveillance and Notification Program

- Program Effectiveness: Interim Federal Health Program

- Program Effectiveness: Pre-Departure Medical Services

- Program Flexibility

- Considerations for Continuity of Care

- Recommendations

- Annex A: Roles and Responsibilities of Migration Health Partners

List of Tables and Figures

- Figure 1: Number of IMEs assessed by RMO

- Figure 2: Proportion of IMEs conducted by age group

- Figure 3: Proportion of IMEs requiring surveillance by age

- Figure 4: Proportion of IMEs indicating a surveillance requirement

- Figure 5: Number of IFHP eligible population compared to IFHP users

- Figure 6: IFHP expenditures for In-Canada resettled refugees, asylum seekers and PDMS

- Figure 7: Proportion of IFHP costs between the fiscal years 2015/16 and 2021/22

- Figure 8: Proportion of IFHP services uptake among asylum seekers and refugees

- Figure 9: Canada TB rates (2020)

- Figure 10: Competing perspectives on the purpose of IFHP

- Figure 11: Summary of International and Canadian Health Partners Communication Mechanisms and Gaps

- Figure 12: Average number of days to submit IMEs after initial exams

- Figure 13: Average number of days to assess admissible IMEs

- Figure 14: Average number of days to assess inadmissible IMEs

- Figure 15: Percentage of IMEs yield of cases deemed inadmissible on health grounds between the fiscal years 2015/16 and 2021/22

- Figure 16: Distribution of potential surveillance cases by intended province of destination between the fiscal years 2015/16 and 2021/22

- Figure 17: In-Canada IFHP registered health care providers' perspectives on program and client outcomes 18

- Figure 18: Percentage of refugees who received support with IFHP

- Figure 19: Overseas IFHP registered providers' perspectives on program and client outcomes

- Figure 20: Global events impacting migration health during the evaluation period

Evaluation Background and Context

Overview

The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of IRCC’s Migration Health Programming. This evaluation was conducted to provide timely evidence, results and information to support the Migration Health Branch (MHB) mandate refresh and program development.

Evaluation Scope

The evaluation examined the three primary Migration Health Programming streams: the Immigration Medical Exam (IME), Medical Surveillance and Notification, and The IFHP.

While the evaluation reviewed the period between 2015 and 2022, an emphasis was placed on recent years.

Migration Health Programming was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, both in terms of delivery and realization of program outcomes. Efforts were made to examine the impact of the pandemic on the program, ensuring that it is portrayed in the appropriate context.

Evaluation Focus

The evaluation had three primary areas of focus:

- Governance: The evaluation examined the role within IRCC and among federal partners in the governance of Migration Health Programming and the effectiveness of governance structure and information-sharing practices.

- Program Effectiveness: The evaluation assessed to what extent Migration Health Programming streams supported clients’ health needs, department priorities and policy requirements, including a summary assessment of IFHP given the reinstatement of the program and its expansion in recent years.

- Flexibility: The evaluation examined the flexibility and responsiveness of the health programming streams to emerging humanitarian and public health crises and the extent to which IRCC program outcomes were met in light of these crises.

In addition, the evaluation took into account various Gender Based Analysis Plus considerations for the program, in accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat’s Directive on Results.

Evaluation Questions

- To what extent is IRCC health programming fulfilling a public health and immigration need?

- To what extent is IRCC health programming aligned with other Canadian health partner responsibilities and objectives?

- To what extent does management and governance of IRCC health programming effectively support departmental program delivery?

- To what extent is IRCC health programming operating effectively?

- To what extent is IRCC health programming reducing the burden of migration on health and social services in Canada?

- To what extent is IRCC health programming protecting the health, safety and security of Canadians?

Methodology

Data collection and analysis took place from September 2022 to December 2023. The evaluation included multiple lines of qualitative and quantitative evidence.

Surveys

Four surveys were undertaken with key stakeholders, including medical professionals, resettled refugees, and settlement service providers. Surveys examined experiences and gathered information on health screening, IFHP and a variety of supports and services.

- Surveys of Panel Physicians and Radiologists: A survey was sent to 1,448 panel physicians to examine the IME process, with 376 completes (response rate of 26%). In addition, 1,287 panel radiologists were administered a separate survey to provide input on the IME process and 115 completions were received (response rate of 9%).

- IFHP Registered Provider Surveys: A survey was sent to 56,520 IFHP registered providers in-Canada to examine the IFHP, with 3,391 completions (response rate of 4%). A separate survey to explore the PDMS was sent to 2,253 IFHP registered providers outside of Canada and received 135 completions (response rate of 6%).

- Survey of Resettled Refugees: The survey was sent to 94,325 resettled refugees admitted between 2016 and 2022 between the ages of 18 and 75 at landing, who had a valid email. The survey collected perspectives on a variety of supports/services received, including healthcare supports and the IFHP with 6,602 completions received (response rate of 7%).

- Survey of Service Providers: The survey assessed experiences with assisting clients in accessing and navigating the Canadian healthcare system and migration health programming. It was sent to a sample of 57 Service Providers (including 35 Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP), 21 Settlement Service Provider Organization (SPO), and 1 umbrella organization) and 32 completions were received (response rate of 56%).

Key Informant Interviews

Fifty-four semi-structured interviews were conducted with 71 key informants and an additional 7 participants provided feedback on Migration Health Programing during two focus groups. Key informants included 35 representatives from IRCC (MHB, Regional Medical Office (RMO)s, other internal staff), 7 participants from other government departments, and 29 key external stakeholders (P/Ts, provincial public health officials, Migration Five (M5) countries, Medavie Blue Cross, academics, etc.).

Administrative Data Review

Analysis was undertaken by examining administrative data from the following sources:

- Global Case Management System (GCMS): client health data including socio-demographic characteristics and IME processing times, IFHP coverage data, etc.

- Medavie Blue Cross Data: claims and reimbursement statistics from the Medavie Blue Cross database, the third-party claims administrator.

Document Review

The document review examined over 100 internal and external documents relevant to Migration Health, including: Government of Canada (GoC) and departmental documents; academic literature; legislative and regulatory documents; program, policy and monitoring information, and functional guidance.

Methodological Considerations, Limitations and Mitigations

Overall, the evaluation used complementary quantitative and qualitative data to reduce gaps and create integrated findings based on multiple lines of evidence. While the methodology had a number of strengths, some limitations were identified.

Surveys

IRCC could not survey all active IFHP providers as their contact information was not collected systematically by either IRCC or Medavie Blue Cross. The available contact information was not up-to-date and in some cases included the email addresses of administrative personnel or billing companies rather than the email addresses of IFHP providers themselves. To ensure an accurate sampling of IFHP providers, duplicate email addresses and those associated with billing companies were removed from the survey population. The results from this survey should be considered exploratory in nature.

The contact information of IFHP clients could not be shared with the evaluation team due to privacy considerations. As a result, the evaluation relied on self-reporting to gather information on their experiences with the IFHP; this was achieved through the refugee survey questions about supports clients needed and received in their first weeks and year in Canada. Similarly, the IFHP provider survey asked about challenges serving IFHP-eligible beneficiaries. The evaluation also added a survey for select SPOs, including those involved in the RAP, to collect perspectives on needs and barriers. As asylum claimants were not surveyed for the evaluation, findings related to their challenges are drawn from the IFHP provider survey, interviews, and document review.

Lastly, survey respondents were not entirely representative of the survey populations. Specifically, the refugee survey over-represented 2022 admissions (+10%), males (+9%), refugees with knowledge of English (+7%) and refugees holding bachelor’s degrees (+8%). Additionally, the service provider survey included mostly RAP SPOs as well as a convenience sample of SPOs. It was not possible to assess the representativeness of the panel physician and radiologist surveys as limited administrative data is collected on these physicians. However, based on reporting RMOs, the survey of panel physicians was representative (within 2%), whereas the radiologist survey over-represents radiologists reporting to Manila (+7%) and under-represents Ottawa (-9%).

Key Informant Interviews

Key stakeholders across P/T jurisdictions were contacted to participate in the evaluation. However, many declined or did not respond to interview requests. To address this gap, multiple attempts were made to contact these stakeholders and to request contact information of other stakeholders. Despite these efforts, it was not possible to interview all P/T representatives. As a result, some findings related to geographic and regional differences were derived from those who agreed to participate.

Despite the limitations, triangulation of multiple lines of evidence, along with the mitigation strategies ensured that evidence and results presented in the evaluation are considered robust and that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.

Program Profile

Overview

Migrant health is a cross-cutting issue that spans almost all IRCC programs and focuses on facilitating the entry and re/settlement of newcomers while protecting the health, safety and security of Canadians, refugees and those in need of protection.

Migration Health Programs

Migration health programming is composed of three primary health programs spanning the migration continuum from application to settlement.

Health Screening Program

Certain foreign nationals are required to have their health assessed via an IME performed by IRCC-designated panel physicians. IRCC uses the IME results to determine whether an applicant is inadmissible to Canada based on three health grounds: danger to public health, danger to public safety and excessive demand on health or social services. In generalFootnote 1, permanent residents (PR) require IMEs, as do their family members, including non-accompanying members. Temporary residents (TR) need medical exams if they plan to stay for more than six months and:

- have lived for more than six months in a prescribed country;

- work in specific fields in which public health must be protected (e.g., health care, childcare); or

- are applying for a supervisa.

Between April 1, 2015 and November 30, 2022, 6,580,986 IMEs were assessed at RMOs (see Figure 1). Although administrative data show the majority of IMEs are assessed by RMOs in Ottawa and New Delhi, it should be noted that IMEs are sometimes assessed by an RMO on behalf of another.Footnote 2

Figure 1: Number of IMEs assessed by RMO

Figure 1

The figure presents a vertical bar chart showing the number of Immigration Medical Exams assessed by the Regional Medical Offices. The figure presents the following data points: 2,276,580 IMEs were assessed in Ottawa, 2,045,811 were assessed in New Delhi, 1,186,747 were assessed in Manila, 1,061,479 were assessed in London, and 10,368 were assessed in the Centralized Medical Admissibility Unit.Of cases that reached admissibility decisions in the same timeframe, 49% were applying for PR, 40% were applying for TR, and 11% were upfront medicals. In general, the proportion of IMEs conducted in support of PR applications decreased over time, from 64% of IMEs conducted in FY 2015/16 to 40% of IMEs conducted in FY 2021/22.

Additionally, IMEs were conducted for an approximately equal proportion of male (52%) and females (48%) and less than 1% for other genders. With regards to age, the majority of IMEs were for individuals aged 19-44 (67%) at the time of the assessment (see Figure 2), while the highest portion of IMEs with a surveillance requirement were for individuals over 65 years of age (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Proportion of IMEs conducted by age group

Figure 2

The figure presents a vertical bar chart showing the proportion of Immigration Medical Exams conducted by age group. The figure presents the following data points: 2% for 0-2 years age group, 3% for the 3-5 years age group, 7% for the 6-12 years age group, 9% for the 13-18 years age group, 67% for the 19-44 years age group, 9% for the 45-64 age group, 4% for the over 65 age group, and for 0.01% of Immigration Medical Exams the age group was unknown.Figure 3: Proportion of IMEs requiring surveillance by age

Figure 3

The figure presents a vertical bar chart showing the proportion of Immigration Medical Exams that had a surveillance requirement by age group. The figure presents the following data points: 0.1% for the 0-2 years age group, 0.8% for the 3-5 years age group, 1.3% for the 6-12 years age group, 0.3% for the 13-18 years age group, 4.2% for the 19-44 years age group, 0.7% for the 45-64 age group, 9.7% for the over 65 age group, and for 1.1% of surveillance requirements the age group was unknown. The figure also includes a horizontal line indicating that the average proportion of Immigration Medical Exams requiring surveillance is 1.7%.Medical Surveillance and Notification Program

Foreign nationals found to have a medical condition of public health significance during their IME are required to report to the provincial or territorial public health authorities to undergo medical surveillance as a condition of admission to Canada. Although it can be requested for other medical conditions of public health significance, inactive tuberculosis (TB) is the only medical condition for which medical surveillance is currently required. P/T public health authorities are responsible for contacting clients and conducting any medical follow-up according to their own respective P/T protocols.

Between April 1, 2015 and November 30, 2022, 114,141 IMEs included a surveillance requirement. In general, the number of IMEs indicating a surveillance requirement increased over time, from 10, 590 in FY 2015/16 to 17,951 FY 2022/23. However, the proportion of IME cases indicating a surveillance requirement has remained relatively stable averaging 1.73% with a range of 1.61% and 1.94% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Proportion of IMEs indicating a surveillance requirement

* Note that the data is up to November 2022.

Figure 4

The figure presents a line graph showing the proportion of Immigration Medical Exams that had a surveillance requirement, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2022/23. The figure presents the following data points: 2015/16 1.76%, 2016/17 1.82%, 2017/18 1.63%, 2018/19 1.61%, 2019/20 1.88%, 2020/21 1.94%, 2021/22 1.63%, and 2022/23 1.72%.Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP)

The IFHP primarily provides limited and temporary healthcare coverage to resettled refugees and asylum claimants, IRPA detainees, and specified groups of foreign nationals designated by the Minister. IFHP has two components – coverage for services overseas (pre-departure medical services; PDMS) and in-Canada services. Medavie Blue Cross is the claims administrator under contract with IRCC to support healthcare providers and clients seeking financial reimbursement during the period of the evaluation.

IFHP provides basic coverage similar to health care coverage provided by P/T health insurance plans, supplemental coverage similar to the coverage provided to social assistance recipients by provincial and territorial governments, prescription drug coverage and also covers the cost of one IME and IME-related diagnostic tests required under the IRPA.

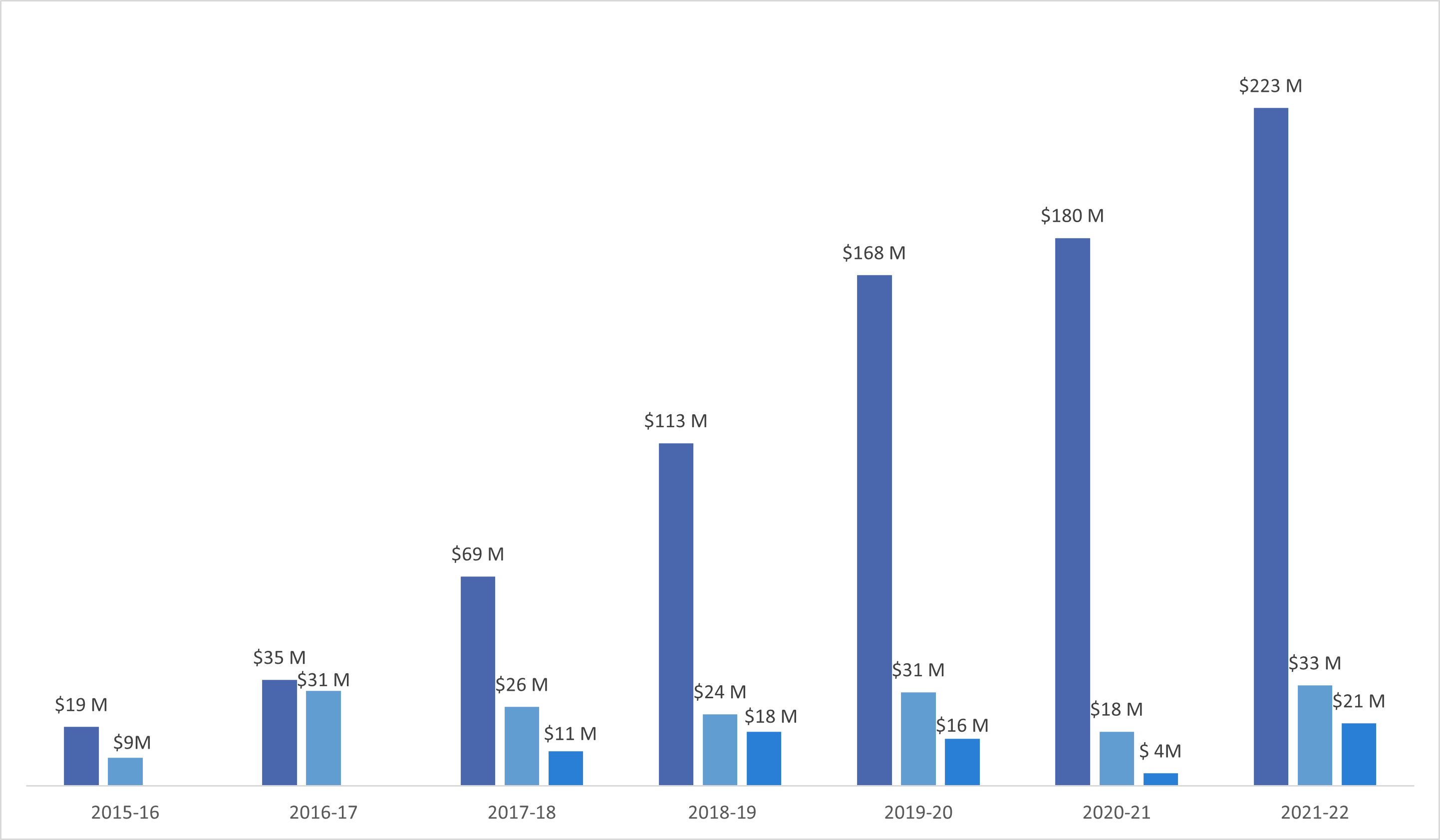

Between April 1, 2015 and November 30, 2022, both the IFHP eligible population and IFHP users (i.e., eligible beneficiaries who make at least one claim) have increased considerably (see figure 6).

Figure 5: Number of IFHP eligible population compared to IFHP users

*Note that health providers typically have up to 6 months to submit invoices for reimbursement to Medavie Blue Cross. Thus, the data relevant to FY 2021-22 in the following tables should be considered as being only preliminary.

Figure 5

This figure presents a clustered bar chart comparing the eligible Interim Federal Health Program population with the Interim Federal Health Program users, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2021/22. The figure presents the following data: 90,328 eligible population and 51,551 users in 2015/16, 130,340 eligible population and 84,401 users in 2016/17, 177,068 eligible population and 127,097 users in 2017/18, 218,972 eligible population and 160,690 users in 2018/19, 280,323 eligible population and 195,909 users in 2019/20, 198,775 eligible population and 122,766 users in 2020/21, and 245,438 eligible population and 171,974 users in 2021/22.Figure 6: IFHP expenditures for In-Canada resettled refugees, asylum seekers and PDMS

Figure 6

The figure presents a clustered bar chart comparing Interim Federal Health Program expenditures for resettled refugees in Canada, asylum seekers, and pre-departure medical services, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2021/22. The figure presents the following data for asylum seekers: 2015/16 $19 million, 2016/17 $35 million, 2017/18 $69 million, 2018/19 $113 million, 2019/20 $168 million, 2020/21 $180 million, 2021/22 $223 million. The figure presents the following data for resettled refugees in Canada: 2015/16 $9 million, 2016/17 $31 million, 2017/18 $26 million, 2018/19 $24 million, 2019/20 $31 million, 2020/21 $18 million, 2021/22 $33 million. The figure presents the following data for pre-departure medical services: 2017/18 $11 million, 2018/19 $18 million, 2019/20 $16 million, 2020/21 $4 million, 2021/22 $21 million.In 2022, in Canada IFHP providers largely provided basic coverage such as medical services (57%), followed by supplemental care such as dental (14%), paramedical (13%), pharmacy (8%), vision services (5%) and other (4%). Similarly, between FY 15/16 and 21/22 basic care (43%) and supplemental care (46%) made up the majority of the 1.05 billion dollars of IFHP cost (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Proportion of IFHP costs between FY 2015/16 and 2021/22

* Note that health providers typically have up to 6 months to submit invoices for reimbursement to Medavie Blue Cross. Thus, the data relevant to FY 2021-22 in the following tables should be considered as being only preliminary.

Figure 7

The figure presents a pie chart showing the proportions of Interim Federal Health Program costs spent on basic care, supplemental care, pre-departure medical services, and Immigration Medical Exams. The figure presents the following data: basic care 46%, supplemental care 43%, pre-departure medical services 7%, Immigration Medical Exams 5%.With the exception of FY 2016/17, asylum seekers accounted for more than half of IFHP users (with a range of 47% to 77%) and the uptake of services among asylum seekers has increased over time with a peak in FY2017/18. The program has seen a fluctuation in the proportion of services used by refugees (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Proportion of IFHP services uptake among asylum seekers and refugees

Figure 8

The figure presents a line graph showing two trends: the uptake of Interim Federal Health Program services by asylum seekers and the uptake of Interim Federal Health Program services by refugees, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2021/22. The figure presents the following data for asylum seekers: 2015/16 55%, 2016/17 63%, 2017/18 75%, 2018/19 70%, 2019/20 68%, 2020/21 63%, 2021/22 64%. The figure presents the following data for resettled refugees: 2015/16 60%, 2016/17 66%, 2017/18 56%, 2018/19 53%, 2019/20 55%, 2020/21 45%, 2021/22 61%.IFHP has also experienced a large growth in providers participating in the Program over time - the number of in-Canada IFHP providers increased four-fold over the reporting period, from 25,190 to 105,448. As of November 2022, services overseas were provided in 89 countries, reflecting a substantial global presence. Notably, between December 2017 and December 2022, the number of PDMS providers more than doubled, from 369 to 812.

Need for Migration Health Programming: Health Screening

Finding 1: There is a continued need to examine and assess migrants’ health status before admission to limit communicable diseases/conditions of concern from entering Canada and to prevent unnecessary burden on the Canadian healthcare system.

The evaluation found a clear rationale to continue to assess the health status of migrants in order to prevent importation of diseases of concern based on Canadian immigration policy, the protection and safety of Canadians and GoC commitments related to TB.

Canadian Immigration Policy

As per the Immigration Refugee and Protection Act (IRPA), a health assessment is required to determine the admissibility of a foreign national on the basis of their health condition and the extent to which their condition poses a danger to public health, public safety, or may cause excessive demand on health and social services in Canada.

Specifically, applicants are found to be a danger to public health if the health screening reveals an active TB infection or untreated syphilis infection. Applicants are inadmissible until they receive treatment for their active illness. Applicants can be found to be a danger to public safety if they have been diagnosed with severe mental health conditions (e.g., an untreated psychotic disorders with a history of violence). Applicants can also be deemed inadmissible if treatment of their condition(s) would surpass three times the average Canadian per capita cost for health and social servicesFootnote 3 and in turn would impact wait lists, the rate of mortality and morbidity in Canada and thus increase the burden on health and social services in Canada.Footnote 4

Health Risk and Immigration

Reviewed literature and interviews stated that there is a health risk associated with migration due to increased global health inequities and the movement of people from regions where certain conditions of public health concern are more likely. Therefore, as Canada is an immigrant receiving country, migration may pose a risk to the health and safety of Canadians including importation of communicable diseases that may seed outbreaks. For example, in 2020 foreign-born individuals accounted for 73.5% of reported cases of active TB in Canada, posing a public health risk of a potential outbreak that would place burden on the Canadian healthcare system.

Interviewed stakeholders reinforced that IMEs screen for several diseases of concern such as active TB, untreated syphilis, and hepatitis B and C, and reinforced that screening is the primary mechanism that Canada has to prevent the importation of these diseases. The majority of surveyed panel physicians reported that the Health Screening program supported:

- outcomes that reduced the risk of infectious disease including facilitating the treatment of active transmissible diseases (89.6%),

- preventing communicable diseases/illnesses from being transmitted in communities (96.3%)

- and protecting the health and safety of Canadians (94.9%).

Government of Canada Tuberculosis Commitments

Interviews and document review found that in addition to the health risks associated with the importation of active TB, IRCC’s health screening program supported Canada’s efforts and international commitments to combat TB through identifying active TB prior to immigration, supporting access to treatment when active TB is identified and decreasing migration-related introduction of TB in Canada to minimise the risk of disease spread.

Need for Migration Health Programming: Surveillance and Notification Program

Finding 2: Based on the prevalence of TB and potential LTBI in foreign-born populations, there is a continued need for IRCC’s Surveillance and Notification Program as part of Canada’s commitment to eliminating TB.

IRCC has an important role in decreasing the introduction of new active TB cases in Canada through the Health Screening program, however many key informants and document review demonstrated that individuals entering Canada with latent TB infections (LTBI) may also contribute to the proliferation of the disease within Canada (Figure 9). Therefore, IRCC’s role in TB Surveillance and Notification is essential to reduce the spread of TB among foreign-born populations.

Figure 9: Canada TB rates (2020)

Figure 9

The figure shows the rate of active tuberculosis in Canada. In 2020, the rate of active tuberculosis was 4.7 per 100,000 in Canada and it was 14.3 per 100,000 for persons born outside of Canada.Identifying Latent Tuberculosis Infection and Surveillance

Health Screening includes a chest x-ray for all applicants 11 years of age or older. Those found to have active pulmonary or laryngeal TB must be treated prior to arrival to ensure that they are no longer infectious, directly contributing to reducing rates of active TB in foreign-born individuals in Canada.

However, due to the nature of the disease, individuals with LTBI can become ill with active TB, months or years after their migration. Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) estimates that 5% of LTBI cases will become active and an additional study suggests that the incubation period of TB is typically several months to two years, and after that, reactivation of the disease is relatively infrequent. Because of this measured risk, individuals arriving in Canada at risk for LTBI are required to report to local public health authorities for further follow-up and surveillance.

Based on the document review and interviews, there is continued need to identify potential LTBI cases and require follow-ups to reduce the TB rates caused by reactivation of the disease in foreign-born populations in Canada. Stakeholders caveated that provincial and territory TB surveillance programs vary across regions and the impact of individual programs is largely unknown. Nevertheless, IRCC’s Surveillance and Notification Program continues to be well-positioned to assess LTBI risk based on IME results and share information with key surveillance stakeholders (e.g., public health authorities) in an effort to reduce and limit the potential spread of TB.

Government of Canada Tuberculosis Commitments

The World Health Organization’s International End TB Strategy serves as a blueprint for countries to reduce TB incidence by 80%, TB deaths by 90%, and to eliminate catastrophic costs for TB-affected households by 2030. The GoC committed to eliminating TB by 2035 across the country, and by 2030 across Inuit Nunangat. Elimination is defined as less than 1 case per 100,000 people. Stakeholders highlighted that Canada's primary method for meeting its TB commitments is the continued identification and treatment of LTBI cases through the Surveillance and Notification Program.

Need for Migration Health Programming: Interim Federal Health Program

Finding 3: There is a continued need for the IFHP to support eligible clients in their health needs; however, its role within IRCC health and broader resettlement programming was unclear

The IFHP provides a critical service for vulnerable migrants (e.g., refugees and asylum claimants) in their early resettlement to Canada. Documents, interviews and surveyed stakeholders confirmed the program contributes to an obligation to support eligible clients in accessing health care. Program data illustrated the continuous growth and use of the program, which also suggests a continued need.

Federal Mandates and Obligations

In 2012, the federal government reduced the coverage of IFHP to only urgent and essential health needs, removing coverage for preventative care and medications. After much criticism, the Supreme Court of Canada found the cuts to be discriminatory and in violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Following the Supreme Court of Canada ruling, the program was reinstated in 2016 and expanded in 2017 to include PDMS to better meet obligations for vulnerable migrants.

Access to Health Care

Nearly all migrants and refugees arrive in Canada with health needs to some degree and interviewed stakeholders emphasized the importance of the program in offering refugees and other eligible clients health care such as access to providers, vaccinations, covering IME costs, dental and vision care, and medication. Furthermore, most surveyed IFHP providers (67.4%) reported the program is supporting the treatment of illness in the client population and addressing client needs by facilitating care until clients are able to transition to provincial or territorial health care (68.5%).

Program Growth

The need for the program is further evidenced by its widespread use. Between 2016 and 2022 there has been an increase in the uptake of the program among refugees and asylum claimants, with the number of people accessing the program increasing by nearly threefold to 171,974 individuals by 2022.

Role of IFHP in Continuity of Care

Despite clear articulation of need for the IFHP, the purpose of the current IFHP and the program’s intended outcomes were unevenly understood, socialized and varied depending on the stakeholder group consulted (Figure 10). A clear example of these divergent views surfaced with the degree to which the program is meant to support the continuity of care from pre-arrival to settlement.

Figure 10: Competing perspectives on the purpose of IFHP

Figure 10

The figure presents a Venn diagram displaying the competing perspectives of stakeholders on the purpose of the Interim Federal Health Program. The figure shows that there are two competing perspectives, with some stakeholder believing that the Interim Federal Health Program offered limited and temporary coverage of health care while others believed that the Program facilitates continuity of care.Despite varied perspectives of program purpose during interviews, document review noted that updated objectives for the IFHP were presented and approved at EXCOM in FY2021/22. Updated objectives included a re-focus of the IFHP on a service delivery model that is more sustainable, flexible and more responsive to client needs, including a “smooth transition to the healthcare system”.

Governance and Management with International and Canadian Health Partners

Finding 4: The roles and responsibilities of international and Canadian health partners are documented, understood and aligned with IRCC’s health programs. However, efforts were isolated and governance suffered from gaps in communication and coordination.

The administration of Migration Health Programming involves several internal and external partners, including partners across federal departments such as PHAC, Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), and Health Canada (HC), as well as partners across P/Ts and international partners (see Figure 11). For example, health screening involves efforts from panel physicians and radiologists who conduct the IME, International Organization for Migration (IOM) staff who coordinate the transportation of refugees to IME appointments, and Medavie Blue Cross, which coordinates the reimbursement of IME costs.

The majority of health partners understood their own role clearly and agreed that the right international, federal, P/T, and local partners participated in migrant health programming (see Annex A: Roles and Responsibilities of Migration Health Partners). However, health partners had difficulty speaking to overarching strategy or program roles in which they were not directly involved as there were limited formalized mechanisms for communication and collaboration. Specifically, information sharing and communication was only reported between certain partners (denoted by arrows in Figure 11), and sometimes only occurred from one health partner to another without an opportunity for feedback (e.g., the relationship between IRCC and CBSA and IRCC and P/Ts).

Figure 11: Summary of International and Canadian Health Partners Communication Mechanisms and Gaps

Figure 11

The figure illustrates the communication and collaboration between various stakeholders in the context of Migration Health Programming. The stakeholders include the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, Canada Border Services Agency, provinces and territories, local public health authorities, Migration Five partners, the International Organization for Migration, panel physicians and radiologists, Interim Federal Health Program registered health care providers, and Medavie Blue Cross. The figure also depicts the flow of information from Migration Health Programming to the various stakeholders, with information flowing bidirectionally between Migration Health Programming and Medavie Blue Cross, panel physicians and radiologists, the International Organization for Migration, and Migration Five partners, while it flows in one direction from Migration Health Programming to the Canada Border Services Agency and the provinces and territories. Collaboration also occurs between the International Organization for Migration and panel physicians and radiologists, and between Medavie Blue Cross and Interim Federal Health Program registered health care providers.Gaps in Partner Communication and Info-Sharing

Internal documents revealed that there are numerous working groups and committees that collaborate on migration health. For example, the Canadian TB Elimination Network brings together TB practitioners, policy specialists from PHAC, Indigenous Services Canada and IRCC as well as other representatives from service organizations and from each of the National Indigenous Organizations to discuss emerging evidence and efforts and policies to eliminate TB. However, the evaluation did not find recent evidence of the activities produced by these committees and working groups, nor on the effectiveness of the information-sharing or decisions made. Further, health partners noted that communication channels across Federal partners were limited and that they primarily relied on their existing relationships with key stakeholders and partners rather than established networks.

Additionally, P/Ts and local partners reported having no formal communication with IRCC to discuss migration health program issues, to request additional health information on IMEs and track program outcomes. Furthermore, IRCC does not have health information sharing memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with all P/Ts.

Interviews indicated that there were strong relationships and information-sharing between international partners (M5, IOM and Panel Physicians and Radiologists) and IRCC, and that communication and coordination between Medavie Blue Cross and IRCC worked well. Medavie Blue Cross’ IFHP processes such as registration, claim submission and eligibility were generally clear; however, surveyed IFHP registered providers noted that the audit policies and processes and trainings were not fully clear.

Governance and Management with Internal Partners

Finding 5: Overall, IRCC health programming is effectively managed and delivered. However, collaboration between connected and supporting IRCC programs is not formalized.

In addition to the external partnerships mentioned earlier, the management of Migration Health Programming also involves internal IRCC partners, including staff across the three migration health programs and staff across the Settlement and Resettlement branches.

Day-to-Day Operations

Internal interviews confirmed that day-to-day operations of migration health programming are generally delivered effectively, with clear internal roles and responsibilities. However, many internal staff expressed concerns regarding antiquated information technology systems (e.g., Excel-based processes, GCMS challenges), which are serious barriers to working efficiently and limit their abilities in daily tasks, as well as their capacity to respond effectively in times of crises (i.e., limited use of relevant technology for forecasting and tracking communicable outbreaks).

Management, communication and coordination

Stakeholders generally expressed satisfaction with the management, communication, and coordination between internal partners. However, it was commonly noted that current mechanisms for collaboration rely heavily on relationships rather than structured frameworks. This relationship-based collaboration leaves management and governance structures vulnerable to organizational changes and staff turnover. Stakeholders raised concerns about MHB being inadvertently excluded from decisions that impact migrant health programming. For example, stakeholders felt that they were often not consulted before new programs or initiatives that had migrant health implications were developed. As a result they have had to expedite processing or create the capacity needed for the impacts of such programs on migration health programming (e.g., to accommodate for an increase in the volume of IMEs that will be conducted and assessed as part of these new programs). Stakeholders also recalled not being consulted in situations where IME requirements had to be waived to accommodate new programming.

Collaboration with Resettlement Policy Branch

Another concern that stakeholders raised was that communication regarding the IFHP between the Resettlement Policy Branch (RPB) and MHB was ad-hoc and informal, which was seen as problematic given the interdependent nature of the roles and responsibilities of MHB and RPB around health navigation and facilitating healthcare for migrants. Refugees are key users of the IFHP, which is managed by MHB, but settlement and resettlement teams are responsible for ensuring that migrants’ health needs are being met. Stakeholders involved in resettlement felt that the IFHP could benefit from formalized mechanisms for communication, collaboration, and pathways to share relevant programmatic decisions between these branches.

Program Effectiveness: Health Screening

Finding 6: The Health Screening program is operating efficiently, however, there is evidence that IMEs expire for some clients before their applications can be processed.

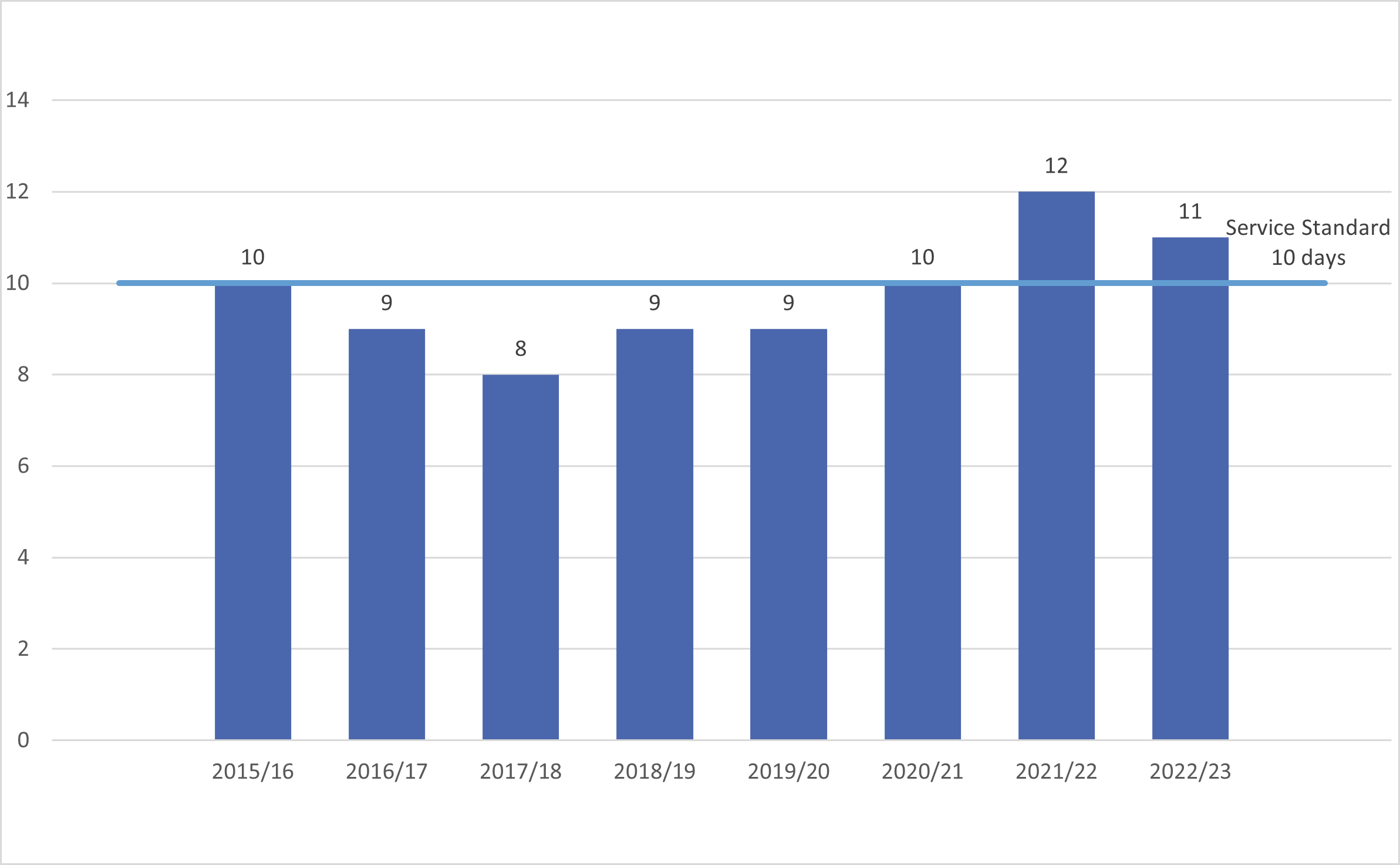

The efficiency of the IME process is integral to timeliness of application processing and the assessment of a foreign national’s admissibility in Canada. The evaluation found that IME screening is being carried out efficiently and mostly meeting its service standards. Specifically, panel physicians met the service standard of submitting IMEs within 10 days of the initial exam in all FYs except for 2021/22 and 2022/23 (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Average number of days to submit IMEs after initial exams

Figure 12

The figure presents a vertical bar chart displaying the average time taken by panel physicians to submit the results of Immigration Medical Exams, from the date of examination, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2022/23. The figure presents the following data: 2015/16 10 days, 2016/17 9 days, 2017/18 8 days, 2018/19 9 days, 2019/20 9 days, 2020/21 10 days, 2021/22 12 days, 2022/23 11 days. The figure also shows that the service standard for submission of Immigration Medical Exam results is 10 days.In addition, 80% of admissible IMEs were assessed within 2 days (Figure 13). Conversely, for inadmissible IMEs, 80% were not assessed within the 90 day service standard between 2015/16 and 2018/19 but were met in more recent years (Figure 14).

Figure 13: Average number of days to assess admissible IMEs

Figure 13

The figure presents a vertical bar chart displaying the average time taken to assess admissible Immigration Medical Exams, from the date of examination, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2022/23. The figure presents the following data: 2015/16 2 days, 2016/17 2 days, 2017/18 1 day, 2018/19 2 days, 2019/20 2 days, 2020/21 2 days, 2021/22 1 day, 2022/23 2 days. The figure also shows that the service standard to assess admissible Immigration Medical Exam is 4 days.Figure 14: Average number of days to assess inadmissible IMEs

Figure 14

The figure presents a vertical bar chart displaying the average time taken to assess inadmissible Immigration Medical Exams, from the date of examination, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2022/23. The figure presents the following data: 2015/16 119 days, 2016/17 224 days, 2017/18 186 day, 2018/19 146 days, 2019/20 76 days, 2020/21 20 days, 2021/22 13 day, 2022/23 37 days. The figure also shows that the service standard to assess inadmissible Immigration Medical Exam is 90 days.However, interviewed stakeholders identified that IME results often expire before decisions are made on immigration applications. Document review confirms that the average application processing time across PR streams exceeds the 12 months of IME validity. The disconnect between processing time and IME validity has often resulted in clients needing to repeat their IMEs and, in some cases, causes delays in application processing. Overall, this has various negative impacts on clients, including the financial cost, stress and time needed to repeat the IME.

IRCC has been working to address this issue for low risk clients in Canada through a temporary public policy that exempts eligible foreign nationals from having to complete a subsequent IME if they have completed one within the 5 years previous to submitting their application. However, the need for repeating IMEs continues for some applicants residing outside of Canada.

Program Effectiveness: Health Screening

Finding 7: The Health Screening program is operating effectively and meeting its objectives, however there are opportunities to increase its facilitative role.

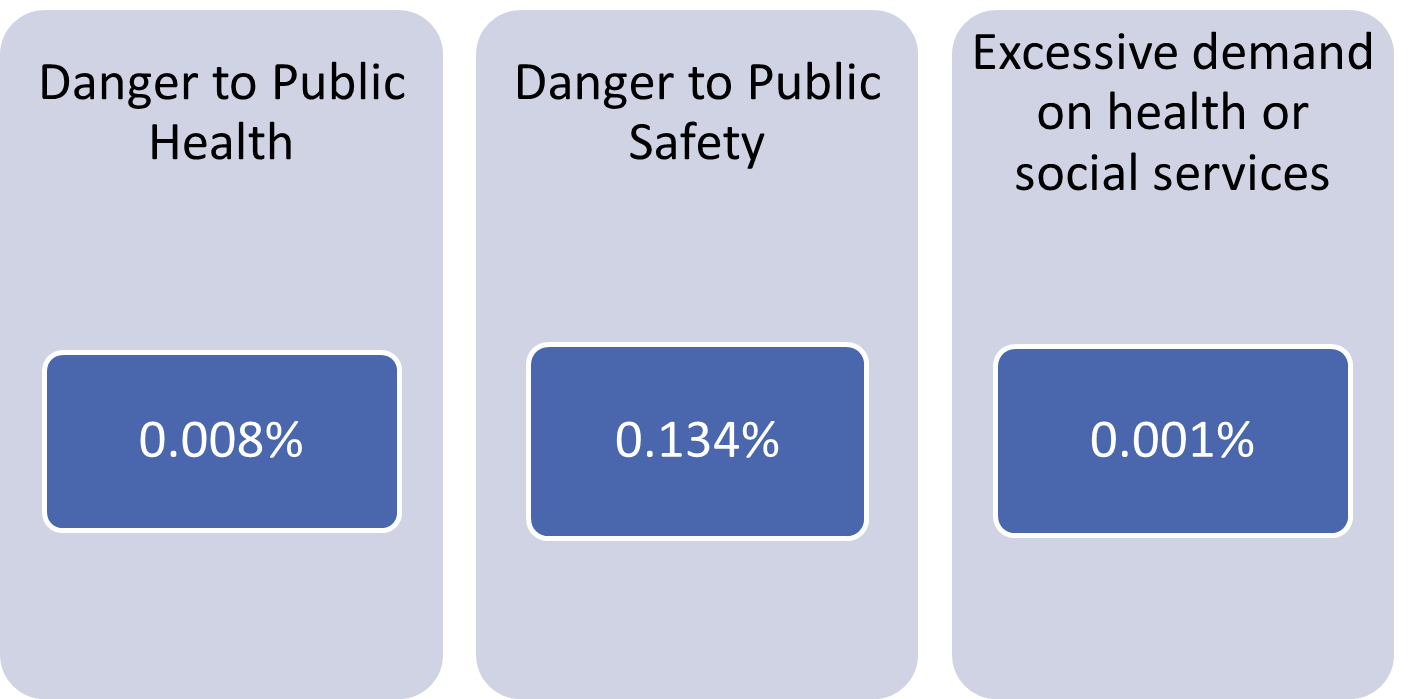

Per IRPA 38(1), inadmissibility can be based on foreign national’s health condition under the following categories:

- Danger to Public Health

- Excessive Demand

- Danger to Public Safety

By identifying such cases, IMEs are effectively meeting its primary objective of admissibility screening within the IRPA (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Percentage of IMEs yield of cases deemed inadmissible on health grounds between FY 2015/16 and 2021/22Footnote 5

Figure 15

The figure shows the percentage of Immigration Medical Exams deemed inadmissible per the Immigration Refugee Protection Act criteria, by fiscal year, from 2015/16 to 2021/22. The figure presents the following data: Danger to Public Health 0.008%, Danger to Public Safety 0.134%, Excessive Demand on Health or Social Services 0.001%.An additional purpose of admissibility health screening is to identify clients with conditions of public health concern for surveillance. Between 2020/21 and 2022/23, the evaluation found that the IME identified between 1.5%-1.7% of TRs for surveillance, and between 1.8%-2.3% of PRs.

Opportunities for Adjustments

Many stakeholders and documents noted that while IMEs are being conducted in an effective manner, there are opportunities to improve the facilitative role of the screening program by exploring protocols for LTBI screening and streamlining IMEs.

LTBI Screening

Interviews, surveys and document review suggested that current TB testing is an effective tool to identify active TB. Symptom screens and chest radiography are appropriate primary screening tools for the identification of active TB. Nearly all panel physicians (98%) reported that IMEs mitigate the high incidence of active TB among migrants and interviewed stakeholders agreed that TB screening during IMEs are necessary to identify and prevent the spread of active TB.

However, reviewed documents and interviews illustrated that the majority of TB in foreign-born populations occurs outside of pre-immigration screening as a result of reactivation of LTBI, therefore identifying LTBI and preventing reactivation is critical. Although the majority of surveyed panel physicians (85%) believed that IMEs adequately screen for LTBI through patient history, symptom screens and chest radiography, interviewed medical experts disagreed and noted that other testing (e.g., IGRA, QuantiFERON testing) may be needed to more robustly and accurately screen for LTBI.

IRCC medical screening protocol does include the use of Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) testing (or Tuberculin Skin Test if IGRA is not available) but only for high risk groups.Footnote 6 Despite agreement for additional LTBI testing, there was no consensus among the medical experts consulted nor in the literature on whether expanding protocols to include this advanced LTBI testing for all IMEs would be ethical given that such testing may not be accessible or affordable to all migrants.

Streamlining IMEs

The majority of stakeholders noted that IMEs could be more streamlined to reduce burden on clients (e.g., time and cost of exam) and based on specific health risks and context. For example, some informants explained that IMEs conducted for PR applicants from low TB incidence countries and those applying for PR from within Canada incur high cost without showing substantial public health benefit. Some noted the importance of TB testing but suggested the removal of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Syphilis testing.

Document review confirmed that streamlining IMEs aligns with the internal IRCC documentsFootnote 7 with respect to enhancing the flexibility of health screening processes and implementing improved risk tolerance.

Furthermore, MHB has been piloting streamlining IMEs for cases of urgent processing (e.g., humanitarian movements, urgent refugee protection and ministerial direction) to include only a chest x-ray and shortened medical history exam rather than the full suite of assessments. Additionally, temporary public policies have been used to allow select populations to undertake a medical diagnostic test, rather than an IME, for example in relation to Ukraine.

While stakeholders generally supported MHB’s implementation of flexible measures during crises, not all stakeholders felt comfortable with the increased risk tolerance and explained that streamlined IMEs and temporary public policies presented risks such as the importation of multi-drug resistant TB that is present in Ukraine.

Program Effectiveness: Surveillance and Notification Program

Finding 8: Lack of clear, consistent communication and coordination between P/Ts and IRCC as well as challenges around sharing medical information have negatively impacted the effectiveness of TB surveillance.

Despite under 2% of IMEs requiring medical surveillance, all stakeholders interviewed from provincial TB surveillance programs noted that it is difficult for P/T public health units to manage the volume of referred surveillance cases. Additionally, internal and external stakeholders noted that gaps in data, communication and coordination negatively impact the overall effectiveness of the surveillance program.

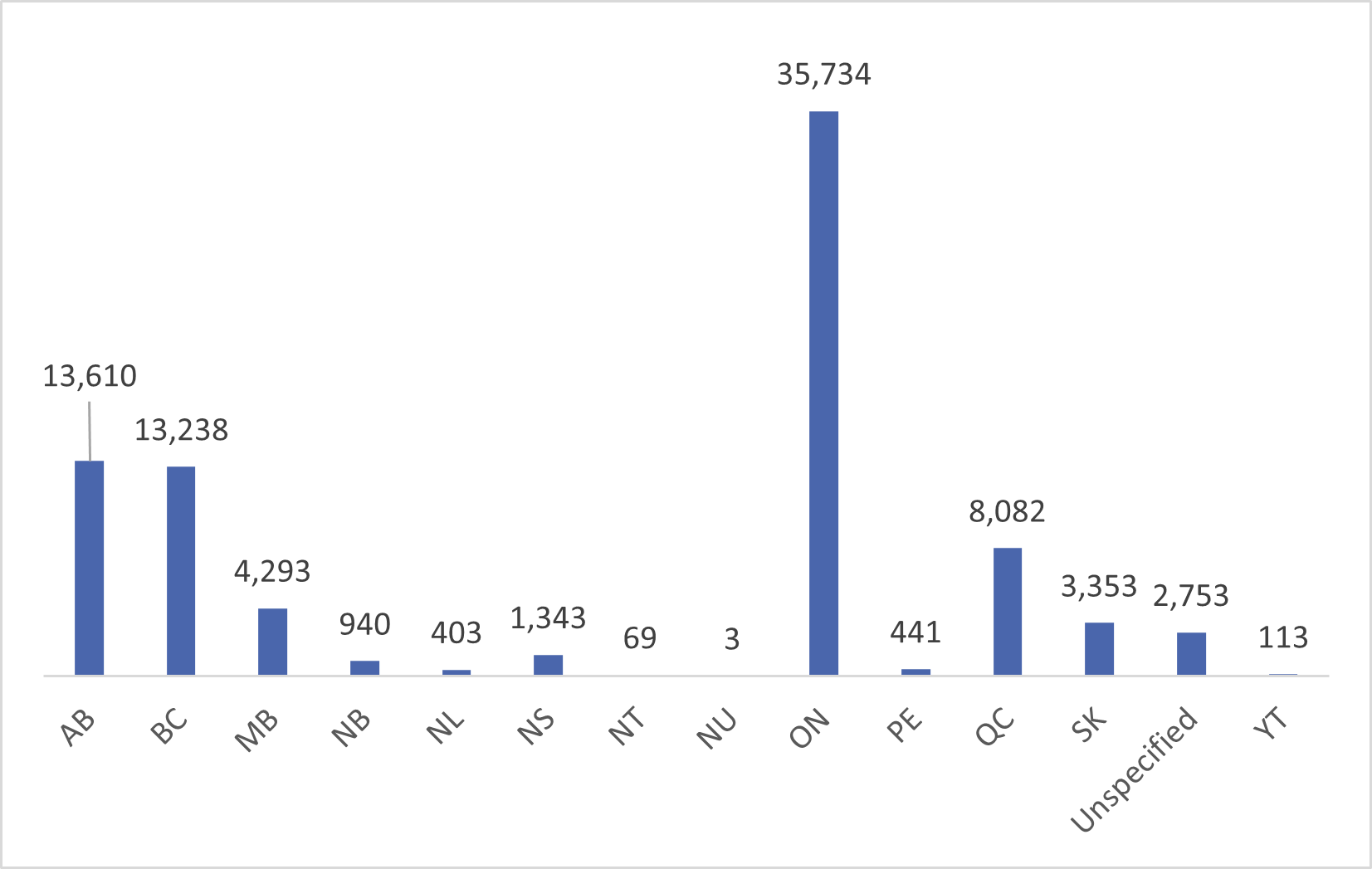

Almost three quarters of IMEs with medical surveillance requirements are for applicants who intend to go to three P/Ts: Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta (Figure 16). Focus groups with Ontario public health officials conveyed a high burden of administering the TB surveillance program due to volume. Focus group participants suggested that IRCC unnecessarily refers clients with low risk of TB reactivation and estimated that very few clients who are referred for surveillance had a high risk for LTBI reactivation. While P/T stakeholders suggested revisiting the surveillance requirement criteria, internal program stakeholders and documents noted that MHB has started identifying high risk groups for TB reactivation in recent program protocols.

Internal stakeholders explained that it is difficult to quantify the true volume of surveillance referrals to P/Ts. The available data indicate the number of IMEs with surveillance requirements, but there is currently no way to systematically measure what proportion of these individuals arrive in Canada.

Figure 16: Distribution of potential surveillance cases by intended province of destination between FY 2015/16 and 2021/22

Figure 16

The figure presents a vertical bar chart showing the distribution of surveillance cases by intended province of destination. The figure presents the following data: Alberta 13,610 cases, British Columbia 13,238 cases, Manitoba 4,293 cases, New Brunswick 940 cases, Newfoundland and Labrador 406 cases, Nova Scotia 1,343 cases, Northwest Territories 69 cases, Nunavut 3 cases, Ontario 35,734 cases, Prince Edward Island 441 cases, Quebec 8,082 cases, Saskatchewan 3,353 cases, Yukon 113 cases, and 2,753 cases did not have a specified province/territory.IME Data Sharing

Interviews and focus groups reported that surveillance referrals based on data from IMEs can often be unclear for receiving agencies. That is, based on the information and test results provided, it is sometimes unclear why the client was flagged for surveillance. Stakeholders from local public health authorities noted that there is no clear mechanism to request additional health information from IMEs, verify test results or connect with IRCC regarding surveillance referrals. Due to gaps in data sharing and limited information, receiving agencies described administering repeat testing, such as chest x-rays, creating inefficiencies and increasing the burden of program delivery.

Tracking Program Outcomes

Internal and external interview participants commented on the lack of formal mechanisms to track whether referrals to surveillance programs contribute to the prevention of TB and some noted concerns that the program is not meeting the perceived purpose of identifying and treating reactivation of TB.

Some, but not all, P/Ts have signed data-sharing MOUs with IRCC regarding the Surveillance and Notification Program. The MOUs outline the client and medical information IRCC provides to the P/T as well as P/T requirement for reporting data to IRCC. However, based on interviews and consultations, the extent to which P/Ts are reporting and how reported data is used at IRCC is unclear to stakeholders.

Communication and Collaboration with Program Stakeholders

Interviews and document review suggested that communication is ad- hoc and lacks standardization between IRCC, federal health partners and P/Ts with regards to TB surveillance and TB in general. A primary example of a gap in communication was the disbandment of the Canadian TB Committee in 2011, which ended formal communication and collaboration between TB experts, Federal and P/T representatives and federal health partners. The committee provided scientific advice to PHAC on strategies and priorities with respect to TB prevention and control. A recent evaluation of PHAC TB Activities (2023) highlighted poor coordination across national TB activities and recommended developing a governance structure to ensure TB activities are better coordinated across Canada to achieve elimination goals.

Program Effectiveness: Interim Federal Health Program

Finding 9: The IFHP effectively provides temporary and limited services to eligible clients. However, several barriers impede the use of the program.

The IFHP is operating effectively, offering resettled refugees, refugee claimants and protected persons who are not yet eligible for P/T health insurance with temporary, ‘last resort’ coverage that is equivalent to basic health care coverage available to Canadians. Such coverage is provided until they qualify for P/T health insurance. Additionally, IFHP offers supplemental coverage for urgent dental care, limited vision care, prescription medications, assistive devices and medical equipment (e.g., hearing aids, prosthetics) and services from allied health care professionals (e.g., psychotherapy and counselling), equivalent to that provided by P/Ts to residents who qualify for social assistance.

Access to Health Care

Most IFHP registered health care providers in Canada as well as SPOs reported that the IFHP is supporting clients in receiving the health care treatment they need. For instance, 71% of providers agreed that IFHP clients are covered for health products and services and 67% agreed that IFHP coverage facilitates the treatment of medical illnesses (see Figure 17). Furthermore, 86% of surveyed SPOs believed that the IFHP supported their clients’ settlement and integration needs. In terms of access to care, 61% of surveyed IFHP providers agreed that IFHP clients have adequate access to their provincial health care services (see Figure 17). This finding is supported by refugees, with 86% of surveyed refugees reporting that they received the general health care information they needed (e.g., finding a doctor), and 85% reporting that they received health care information and support for their urgent medical needs in their first weeks in Canada.

Figure 17: In-Canada IFHP registered health care providers' perspectives on program and client outcomes

Figure 17

The figure presents a stacked horizontal bar chart showing the perspectives of the in-Canada Interim Federal Health Program registered health care providers on the Interim Federal Health Program and client outcomes. The figure presents providers’ level of agreement with five statements, the data is as follows: 21% strongly agreed and 47% agreed that the Interim Federal Health Program facilitates care to clients until they transition to provincial or territorial health care; 20% strongly agreed and 47% agreed that the Interim Federal Health Program coverage facilitates the treatment of medical illnesses; 16% strongly agreed and 38% agreed that the Interim Federal Health Program facilitates the prevention of medical illnesses; 18% strongly agreed and 43% agreed that the Interim Federal Health Program clients have adequate access to their provincial health care system; and 19% strongly agreed and 51% agreed that the Interim Federal Health Program clients are covered for health products and services.However, survey results revealed that the majority of clients required support to access IFHP services and are dependent on others to facilitate access to, and use of, the IFHP. Specifically, refugees most commonly reported needing support to access services by family doctors (83%), dentists (73%), pharmacists (70%) and optometrists (60%) in their first year in Canada. SPOs provided such support, with 90% of surveyed SPOs reported helping their clients navigate the IFHP. SPOs and RAP SPOs shared that they supported clients with understanding the IFHP (e.g. understanding what is covered and the length of coverage; 97%) as well as with finding IFHP providers in their community (97%). Additionally, they provided support booking appointments (93%), responding to questions (90%), and finding translation services (87%). Overall, the majority of refugees reported receiving the information and support they needed with various aspects of the IFHP (see Figure 18).

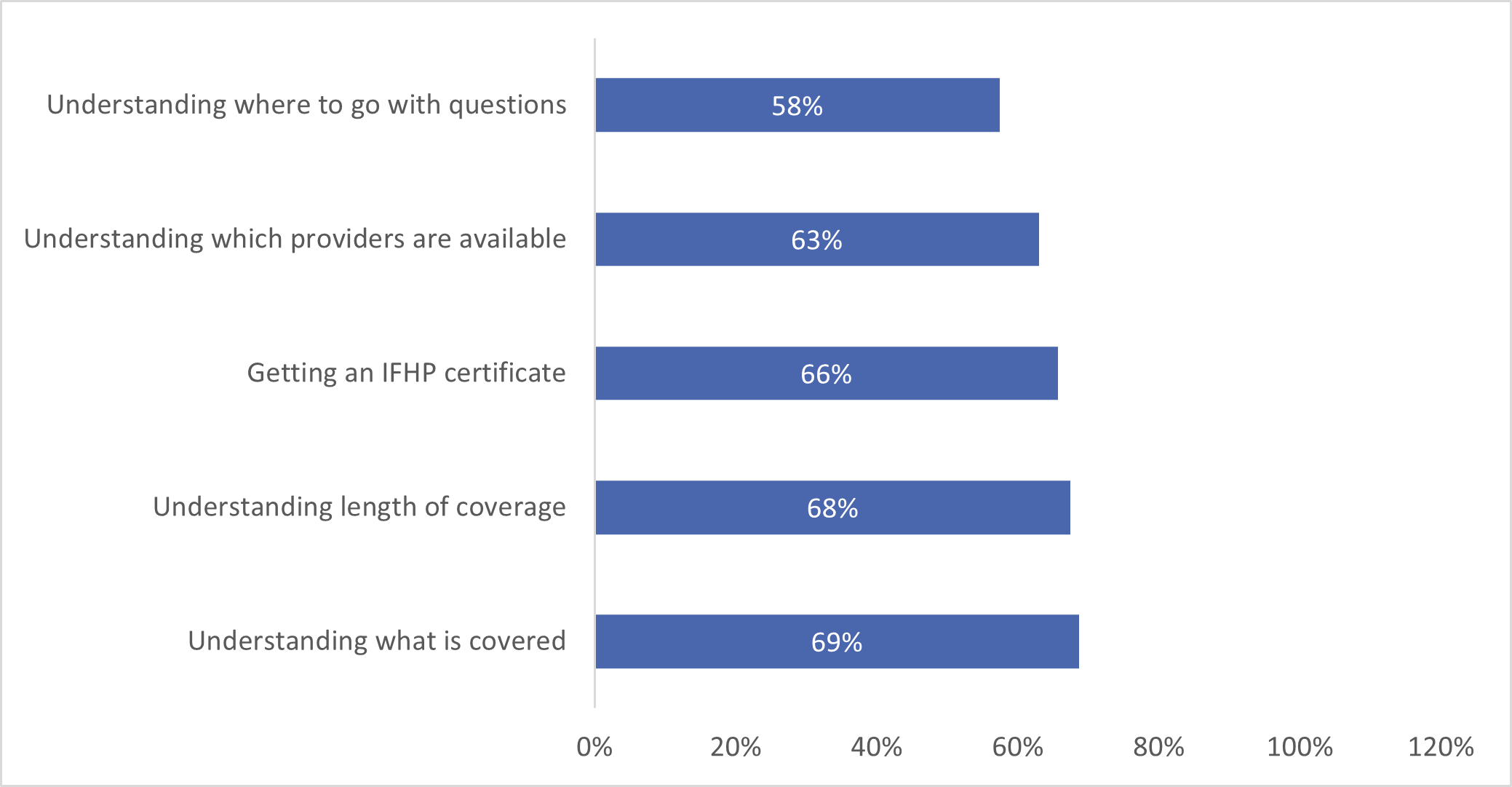

Figure 18: Percentage of refugees who received support with the IFHP

Figure 18

The figure presents a horizontal bar graph showing the percentage of refugees who received support with the Interim Federal Health Program as well as the type of support received. The figure presents the following data: understanding what is covered 69%, understanding the length of coverage 68%, getting an Interim Federal Health Program certificate 66%, understanding which providers are available 63%, understanding where to go with questions 58%.Barriers and Challenges

Awareness and understanding of the program

Interviewed stakeholders believed that awareness and understanding of the program was limited among health care providers and reported poor understanding of IFHP coverages. Document review noted that lack of awareness of the program can contribute to low IFHP provider registration rates. While administrative data showed that there has been progress in registering additional providers between 2016 and 2022, with the number of registered IFHP health care providers increasing by fourfold during this period, half of surveyed SPOs and 39% of surveyed refugee sponsors reported gaps in the availability of specialized health services (e.g., mental health services, pediatrics).

A quarter of IFHP providers surveyed (24%) noted that clients experienced difficulty accessing and understanding information about IFHP coverage. Additionally, SPOs who offer support to clients using the IFHP expressed concerns over the lack of transparency on denials of services noting that denials did not include any reasoning or explanation.

Translation and Interpretation Services

Document review, surveys and interviews noted that access to translation and interpretation services was a primary barrier for clients. In particular, 38% of surveyed IFHP health care providers in Canada and 69% of surveyed SPOs listed language as the primary barrier for clients seeking access to health care services. Nearly half of surveyed refugees expressed the need for support related to translation and interpretation services and approximately 11% did not receive the necessary support to meet their needs or received inadequate support. Additionally, surveyed SPOs reported challenges with getting approval from Medavie Blue Cross for translation and interpretation services for clients. Interviews also revealed that access to translation and interpretation services varied by P/T. As a result, SPOs noted that clients in certain P/Ts faced difficulty understanding and communicating with their health care providers.

Furthermore, surveyed SPOs reported experiencing challenges when advocating for clients whose needs were not being met. Specifically, some SPOs noted that Medavie Blue Cross would only speak to the client and would not respond to SPOs, even in situations where clients could not speak either of Canada’s official languages.

Vulnerable Client Groups

Surveys and interviews also suggested that the IFHP could not address the needs of certain client populations, namely the detainee population and clients with complex medical needs.

Specifically, interviews indicated that IFHP services and claim reimbursement were not designed to support detainee populations. For example, IFHP does not cover all the costs associated with medications (e.g., dispensing fee for methadone). As a result, CBSA often covers the dispensing fee for individuals who do not have the necessary funds. Additionally, stakeholders explained that the reimbursement structure and billing processes led to service providers discontinuing their relationship with the program (e.g., stakeholders noted that some pharmacies refused to serve detainees under the IFHP due to lengthy billing procedures).

Interviews also suggested that coverage is sometimes insufficient for clients with complex medical needs or those who require specialized services. For example, stakeholders noted that the 12-month mental health coverage through IFHP is insufficient to support mental health needs of resettled refugees who require time to settle and meet their physical needs before they are able to seek mental health support. Stakeholders also explained that the needs of refugees are vastly different than those of the average Canadians, and as a result IFHP cannot meet the needs of that population so long as it is based on basic Canadian health coverage.

Program Effectiveness: Pre-Departure Medical Services

Finding 10: While the IFHP effectively offers limited PDMS for refugees destined for Canada, there are challenges with the current funding model that limits program partners’ ability to respond to emerging needs.

The IFHP effectively provides limited PDMS for refugees destined for Canada, covering the treatment of active medical conditions that would make an individual inadmissible to Canada (i.e., active TB or untreated syphilis), immunization costs, treatment of outbreaks in refugee camps, medical support during travel, and the cost of the IME. These PDMS are delivered primarily by the IOM, with IMEs being completed by IRCC panel physicians and radiologists, and health services being provided by IFHP overseas registered providers. Administrative data revealed that the most common reimbursed PDMS services provided between 2017 and 2022 were IMEs and related tests, outbreak response, and, in later years, COVID-19 related services.

Interviews and survey results demonstrated that PDMS supported the achievement of various migration health outcomes. Over 85% of registered IFHP providers overseas agreed that PDMS facilitates appropriate treatment for clients, the identification of diseases that can be a danger to public health and safety, and the prevention of medical illnesses and spread of communicable diseases to Canada. Almost all registered IFHP providers agreed that PDMS supports clients' ability to transition to the Canadian healthcare system (see

Figure 19). Interviews confirmed the survey results, with stakeholders emphasizing that PDMS has been vital in stabilizing refugees before travel. They also added that PDMS coverage was critical in managing outbreaks, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, interviews identified some challenges with the PDMS, noting that the grid model for reimbursement of IFHP services is more appropriate for post-arrival services than pre-arrival services. Stakeholders explained that other countries rely on the IOM to identify and provide PDMS within a total budget, thus allowing them flexibility in providing emergency services they deem necessary. In contrast, Canada's reimbursement model confines IOM to the services listed in the IFHP coverage grid and requires the submission of requests for any services not included in the grid. Stakeholders clarified that they often have to seek external funding for services outside of the IFHP grid when their requests for additional funding from IFHP are rejected (e.g., applying for funding through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and non-governmental organizations). Stakeholders added that coverage is often not sufficient for certain diagnostic tests (e.g., echocardiogram), specialist consultations, or emergency surgeries needed to stabilize patients before travel.

Figure 19: Overseas IFHP registered providers' perspectives on program and client outcomes

Figure 19

The figure presents a stacked horizontal bar chart showing the perspectives of the overseas Interim Federal Health Program registered health care providers on pre-departure medical services and client outcomes. The figure presents providers’ level of agreement with five statements, the data is as follows: 68% strongly agreed and 45% agreed that the pre-departure medical services facilitate appropriate treatment for clients; 66% strongly agreed and 52% agreed that the pre-departure medical services facilitate the prevention of medical illnesses; 74% strongly agreed and 49% agreed that the pre-departure medical services are effective in preventing the spread of diseases threatening to Canadian health; 74% strongly agreed and 50% agreed that the medical screening is effective in identifying diseases hat can be a danger to public health and safety; and 69% strongly agreed and 48% agreed that the pre-departure medical service coverage for resettled refugees support client’ ability to transition to the Canadian health care system.Program Flexibility

Finding 11: MHB health programming is flexible and adaptable in the face of humanitarian and public health crises, as it facilitates the protection of refugees during humanitarian movements.

Flexibility in migration health programming is key to adapting to the constantly evolving migration and health landscapes. During the evaluation period alone, several global events and health crises have impacted migration health programming (see Figure 20), increasing the volume of IMEs conducted and the speed with which they are assessed, changing quarantine requirements and restrictions on global movements, and increasing the demand for health services.

Figure 20: Global events impacting migration health during the evaluation

Figure 20

The figure lists several global events that impacted Migration Health Programming during the evaluation period. In 2015, the Government of Canada committed to resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees by December 31st, 2015. In 2019, the World Health Organization declared the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo a public health emergency of international concern. In 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 global pandemic and implemented temporary measures for those affected by the situation in Afghanistan. In 2022, the Government of Canada implemented temporary measures to support Ukrainian nationals and their family members overseas and in Canada.The evaluation found migration health programming to be flexible and responsive to emerging humanitarian and public health crises. For instance, in response to humanitarian crises and the urgency with which admissibility needs to be assessed, migration health programming introduced streamlined IMEs. Streamlined IMEs are more limited in scope than regular IMEs and, therefore, can be conducted more quickly by panel physicians and with fewer resources. Stakeholders believed that streamlined IMEs supported expedited processing for clients and facilitated the protection and rapid movement of refugees. Furthermore, 88% of surveyed panel physicians reported that IMEs moderately enhanced the ability to adapt to emerging public health events and only 5% of surveyed panel physicians felt that service standard timelines were not sufficiently flexible for adhering to COVID-19 requirements. Stakeholders were also in support of temporary policies that waived IME requirements or allowed IMEs to be completed in Canada in situations where refugees could not safely attend an IME appointment or get diagnostic tests completed before travel (e.g., urgent movements such as Afghanistan and Ukraine). Although stakeholders noted that this approach bears risk of disease importation, they believed it can be facilitative during urgent movements.

Migration health programming was also responsive to the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it increased the number of services and total funding through PDMS for outbreak management, with an additional $3,700,597 being spent on, and 36,720 services being reimbursed for, COVID-19 related expenses in 2021-22. Additionally, stakeholders cited the administration of COVID-19 vaccinations during IME appointments as evidence of the program’s adaptability to emerging public health crises and believed that this measure facilitated the protection of the health and safety of migrants and Canadians.

Stakeholders credited migration health programming flexibility to the strong collaboration between IRCC and international and federal partners, including the IOM, PHAC, and CBSA. For example, they noted that IRCC and IOM worked closely during the Ebola outbreak to assess public health risks and adjust programming to support quarantine measures (e.g., delaying travel of migrants to align with the isolation requirements set by PHAC).

Considerations for Continuity of Care