ARCHIVED – Evaluation of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

Research and Evaluation Branch

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

April 2018

Ci4-179/2018E-PDF

978-0-660-27129-3

Reference Number: E3-2017

On this page

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Evaluation of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services—Management Response Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Pre-Arrival Services Profile

- 3. Methodology

- 4. Relevance

- 5. Impact of Pre-Arrival Services

- 5.1. Usefulness of Pre-Arrival Services

- 5.2. Alignment of Pre-Arrival Services Information with Specific Client Needs

- 5.3. Clients gain knowledge of life in Canada and the Canadian work environment

- 5.4. Clients make informed decisions about life in Canada

- 5.5. Creating Pathways to Settlement Services and Usage in Canada

- 5.6. Clients Participate in the Canadian Labour Market

- 6. Program Management

- 7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: Detailed List of in-Person Pre-Arrival Service Locations (FY2015/16 – FY 2017/18)

- Appendix B: Detailed Profiles

- Appendix C: Detailed List of Pre-Arrival SPOs (FY2015/16 – FY 2017/18)

- Appendix D: IRCC Settlement Program Logic Model

- Appendix E: List of Evaluation Questions

- Appendix F: Key Survey Frequency Tables

List of tables and figures

- Figure 1: Evolution of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

- Table 1: Profile of Pre-Arrival Services

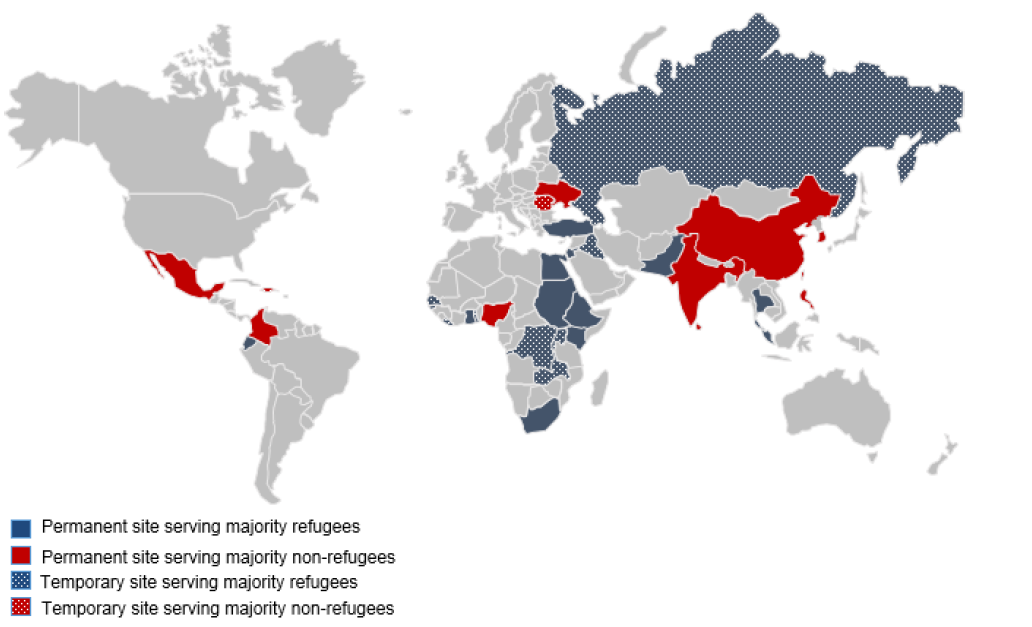

- Figure 2: Location of In-Person Pre-Arrival Services

- Figure 3: SPO Expenditures (April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017)

- Figure 4: Non-Refugee Clients – Time from using Pre-Arrival Service to Admission

- Table 2: Share of non-refugees indicating the information was helpful

- Table 3: Share of non-refugees indicating the information was helpful to prepare to look for job

- Table 4: Share of refugees indicating the information session was helpful

- Table 5: Non-refugees level of information prior to coming to Canada

- Table 6: Non-refugees’ knowledge of life in Canada upon arrival

- Table 7: Non-refugees’ difficulties experienced during the first three months in Canada

- Table 8: Official Uptake of Pre-Arrival Services by Fiscal Year of Admission (April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017)

- Table 9: iCARE-based and Adjusted Uptake of Pre-Arrival Services by Immigration Category (April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017)

- Table 10: Expected Annual Client Target, Pre-Arrival SPOs

- Table 11: Top 10 Refugee Source Countries, Locations of In-Person Pre-Arrival Services and Estimated Uptake, April 1, 2015 – August 31, 2017

- Table 12: Overall Projected vs. Actual Cost per Client – Pre-Arrival SPOs (FY 2015/16 – FY 2017/18)

- Table 13: Projected vs. Actual Cost per Client – Pre-Arrival SPOs (FY 2015/16 – FY 2017/18)

- Table 14: Pre-Arrival SPO Performance by SPO Types

- Table B1: Profile of Pre-Arrival Clients and Non-Clients Admitted to Canada between April 1, 2015 – August 31, 2017

- Table B2: Profile of IRCC-funded Domestic Settlement Service Clients Admitted to Canada between April 1, 2015 – August 31, 2017

- Table F1: Non-Refugees - Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements

- Table F2: Non-Refugees - Please indicate whether or not you had enough information on any of the following topics prior to coming to Canada

- Table F3: Refugee clients - Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements

- Table F4: Non-Refugees - During your first three months in Canada…

List of acronyms

- ACCC

- Association of Canadian Community Colleges

- AEIP

- Active Engagement and Integration Project

- CA

- Contribution Agreement

- CEC

- Canadian Experience Class

- CC

- Community Connections

- CICan

- Colleges and Institutes Canada

- CIIP

- Canadian Immigration Integration Project

- COA

- Canadian Orientation Abroad

- ERS

- Employment-Related Services

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- FSW

- Federal Skilled Worker

- GAR

- Government-Assisted Refugee

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- GCS

- Grants and Contributions System

- I&O

- Information and Orientation Services

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- IS

- Indirect services

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- NARS

- Needs Assessments and Referrals

- PSR

- Privately Sponsored Refugee

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

Executive summary

Purpose of the Evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Pre-Arrival Settlement Services. The evaluation was conducted to inform future program improvements and in fulfillment of requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on Results and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act and covered the period of fiscal (FY) years 2015/16 - 2017/18.

Overview of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

The objective of IRCC’s pre-arrival services is to provide selected Permanent Residents,Footnote 1 including refugees, with accurate, relevant information and supports so that they can make informed decisions about their new life in Canada and begin the settlement process (including preparation for employment) while overseas. It is expected that these services will enable clients to be better prepared upon arrival to Canada to settle and integrate into Canadian society.

Pre-arrival services provide the same types of services as IRCC-funded in-Canada Settlement services, with the exceptions of Language Assessments and Language Training. Through contribution agreements, IRCC funds service provider organizations (SPOs) such as immigrant-serving agencies, industry/employment-specific organizations or educational institutions to provide the following types of pre-arrival services: Needs Assessments and Referrals, Information and Orientation, Employment-Related Services and Community Connections.

Pre-arrival services vary considerably in scope, delivery models and size (e.g., project funding and number of clients targeted). Some focus on providing information and supports to specific immigration categories or sub-sets of newcomers, some target specific sectors or professions while others only support newcomers destined to certain provinces. Most service providers offer services via web-based platforms while a few provide in-person services.

Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations

Pre-arrival services are needed and useful, as they help newcomers prepare for their settlement before they depart for Canada.

One of the primary expected outcomes from pre-arrival services is to provide relevant information and supports so that newcomers can make informed decisions about their new life in Canada and begin the settlement process before arriving. In this regard, all client groups found pre-arrival services to be useful and participants are gaining knowledge of life in Canada and the Canadian labour market at a higher rate than non-clients. For example, a greater share of pre-arrival clients (compared to non-clients) indicated having enough information on how to contact organizations that provide help in settling in Canada, how to have professional credentials and/or qualifications recognized, and to understand Canadian workplace culture and norms. Many pre-arrival clients are also taking actions as a result of pre-arrival services, such as looking for work, changing what they bring to Canada and deciding to further training/education to upgrade their skills. Finally, pre-arrival services have also been effective at providing referrals and linking clients with in-Canada settlement services, and these clients have been accessing IRCC-funded settlement services in Canada at a higher rate than non-users of pre-arrival services.

While clients find pre-arrival services useful, the majority of newcomers are not aware of their existence and uptake remains low for non-refugee immigrants. Ineffective promotion of these services, coupled with the absence of a comprehensive strategy to guide pre-arrival service expansion and a lack of clarity within IRCC regarding roles and responsibilities for the program delivery has resulted in a missed opportunity for the Department to positively impact more newcomers, and also in higher than expected per client costs.

Some areas for program improvements have been identified, and as such, this evaluation report proposes the following recommendations.

Framework and guidance

While there is a need to provide a mix of different services, the approach to service expansion has lacked a clearly defined strategy or framework, including a definition of how the various services were expected to be delivered, to complement one another and align with in-Canada settlement services.

Recommendation 1: IRCC should develop a comprehensive program framework and guidance for pre-arrival services that provides a clear strategic direction for program delivery.

This framework should:

- Articulate the vision for IRCC pre-arrival services, including objectives and expected results

- Consider the appropriate mix of the various delivery models and approaches

- Consider the alignment of service offerings and delivery approaches with the differing profiles and needs of various client types

- Include a strategy to identify and prioritize the optimal locations for the delivery of in-person services

- Consider the cost of services and value for money

Promotion

Despite efforts to expand the availability of pre-arrival services by increasing the number of SPOs in 2015, the absence of an effective promotion strategy from IRCC affected the reach and impact of pre-arrival services. In addition, there are opportunities to actively inform or enroll prospective clients into pre-arrival services at an earlier stage.

Recommendation 2: IRCC should develop and implement a pre-arrival services promotion strategy to significantly increase awareness and uptake.

This strategy should:

- Outline the key activities and guidance needed to improve awareness and increase program participation

- Clarify the roles and responsibilities for IRCC (including Missions abroad) and SPOs with respect to promotion

- Consider earlier opportunities for informing potential clients to help ensure they have sufficient time to access services

Governance

The rapid expansion of partners and stakeholders, coupled with a lack of clarity related to roles and responsibilities made it difficult to ensure a coherent approach to management of pre-arrival services.

Recommendation 3: IRCC should clarify and strengthen its governance to lead and coordinate pre-arrival services by:

- Establishing clear roles and responsibilities among internal IRCC stakeholders, including across NHQ, regions and International Network

- Clarifying the role of Missions in the delivery and monitoring of in-person pre-arrival services and SPOs

Strengthening the Continuum of Settlement Services

While many pre-arrival SPOs have undertaken partnerships and established networks of cross-referrals on their own, there are opportunities for IRCC to take a stronger leadership role to ensure pre-arrival SPOs are connected to one another and to IRCC’s domestic Settlement network, which would ensure more seamless pathways and efficient delivery for pre-arrival clients.

Recommendation 4: IRCC should establish a mechanism to promote collaboration, cross-referrals and sharing of best practices among pre-arrival SPOs and pre-arrival and domestic settlement SPOs.

Performance Measurement

A lack of standardized performance measurement tools and challenges in data collection have affected the ability of the Department to effectively report on pre-arrival services results in an in-depth manner and identify trends and address issues quickly, as they arise.

Recommendation 5: IRCC should strengthen performance measurement and reporting for pre-arrival services, by:

- Developing key indicators and data strategies to support collection of performance information

- Considering developing a targeted Performance Information Profile for pre-arrival services which aligns with IRCC’s Settlement Program and Resettlement Program Performance Information Profiles

Evaluation of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services—Management Response Action Plan

Recommendation #1

IRCC should develop a comprehensive program framework and guidance for pre-arrival services that provides a clear strategic direction for program delivery.

This framework should:

- Articulate the vision for IRCC pre-arrival services, including objectives and expected results

- Consider the appropriate mix of the various delivery models and approaches

- Consider the alignment of service offerings and delivery approaches with the differing profiles and needs of various client types

- Include a strategy to identify and prioritize the optimal locations for the delivery of in-person services

- Consider the cost of services and value for money

Response #1

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC acknowledges the need for a clearly defined and coordinated strategy for pre-arrival programming, to ensure the delivery of high quality services that are client-centred and aligned with our key partners, including provinces and territories.

The Department is developing a program framework that articulates an overall vision and guidance for the delivery of pre-arrival programming, including objectives and expected outcomes. Through a more structured and streamlined service delivery approach, IRCC will ensure that clients are informed of available services and can easily access them; clients will be systematically directed to a small number of service providers for orientation, assessment and referral to tailored pre-arrival and in-Canada services, based on specific needs. Programming will focus on the coordination of services through distinct pathways for refugees, economic and family class, and Francophone immigrants. Consideration will be given to different service offerings to meet the needs of various client types.

Policy and functional guidance that is aligned with the overall vision for the pre-arrival program will be a key part of supporting the framework.

IRCC acknowledges that the rapid expansion of service providers delivering pre-arrival services incurred considerable infrastructure costs, and as such, costs to deliver services and value for money, in addition to client experience, are key considerations in the development of the program framework.

Action #1a

Develop a pre-arrival program framework that includes a vision, objectives and expected outcomes that are aligned with the Settlement and Resettlement Programs (with distinct pathways and services for refugees, economic and family class and Francophone immigrants).

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Settlement Network, Refugee Affairs Branch, International Network, Provinces/Territories

Completion Date: Q1 2018/19

Action #1b

Disseminate program framework to the Settlement Sector via the funding guidelines for the Spring 2018 pre-arrival program intake process.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Completion Date: Q1 2018/19

Action #1c

Integrate the program framework, including value for money considerations, into negotiation of contribution agreements (CAs) with service providers.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #1d

Develop and issue policy guidance for IRCC staff to ensure consistent interpretation of policy requirements.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #1e

Develop and issue functional guidance for service provider organizations (including guidance related to cost of services) to ensure consistent implementation of services.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #1f

Complete a comparative analysis of in-person and online services to ensure optimization of the two delivery models in terms of location, value for money and client experience.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Research & Evaluation, Settlement Network

Completion Date: Q4 2019/20

Recommendation #2

IRCC should develop and implement a pre-arrival services promotion strategy to significantly increase awareness and uptake.

This strategy should:

- Outline the key activities and guidance needed to improve awareness and increase program participation

- Clarify the roles and responsibilities for IRCC (including Missions abroad) and SPOs with respect to promotion

- Consider earlier opportunities for informing potential clients to help ensure they have sufficient time to access services

Response #2

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC acknowledges the need for IRCC leadership to better connect our clients to pre-arrival settlement services prior to their arrival in Canada so that they can begin their settlement journey with realistic expectations and be better prepared.

This whole-of-Department promotion strategy will be client-focused, integrated within the immigration process, and include targeted orientation to refugees overseas. The strategy will be developed in consultation with Provinces and Territories as well as Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC).

Action #2a

Develop a whole-of-Department promotion strategy outlining key activities and timelines. The strategy will identify roles within IRCC, in particular National Headquarters and Missions, and of SPOs in promoting services.

Accountability: Communications Branch

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch, Settlement Network, International Network, Client Experience Branch, Refugee Affairs Branch, Provinces/Territories

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #2b

Implement Promotion Strategy.

Accountability: Communications Branch

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch, Settlement Network, International Network, Client Experience Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #2c

Analyze the timing of pre-arrival client eligibility within the immigration process, and develop options to optimize the length of time available for clients to access services. The options will be presented to Senior Management for consideration.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Client Experience Branch, Settlement Network

Completion Date: Q4 2018/19

Recommendation #3

IRCC should clarify and strengthen its governance to lead and coordinate pre-arrival services by:

- Establishing clear roles and responsibilities among internal IRCC stakeholders, including across NHQ, regions and International Network

- Clarifying the role of Missions in the delivery and monitoring of in-person pre-arrival services and SPOs

Response #3

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department acknowledges the challenges associated with the rapid expansion of pre-arrival services in 2014, including low client awareness and uptake; a lack of coordination; and inconsistent service delivery.

IRCC is committed to improving its internal governance to increase coordination and support improved pre-arrival services.

Action #3a

Establish (via a Director General level table) a structured Accountability Framework for pre-arrival services that clearly identifies roles and responsibilities across IRCC.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Settlement Network, International Network, Communications Branch, Refugee Affairs Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #3b

Develop guidance and tools for Missions to support project monitoring.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: International Network

Completion Date: Q3 2018/19

Action #3c

Finalize and implement Accountability Framework.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Settlement Network, International Network, Communications Branch, Refugee Affairs Branch

Completion Date: Q4 2018/19

Recommendation #4

IRCC should establish a mechanism to promote collaboration, cross-referrals and sharing of best practices among pre-arrival SPOs and between pre-arrival and domestic settlement SPOs.

Response #4

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

In January 2018, IRCC hosted an in-person pre-arrival settlement services meeting, bringing together representatives from pre-arrival settlement service providers, provincial and federal governments, to help strengthen communication and partnerships and consider how to enhance program outcomes.

Building on the successful meeting, IRCC recognizes the need for more formalized coordination among pre-arrival services providers and between service providers and key partners, including provinces and territories and domestic settlement service providers.

Engagement with pre-arrival services providers and across key partners, including domestic settlement service providers, provinces and territories and ESDC, will be key to establishing formalized coordination mechanisms.

Action #4a

Fund a National pre-arrival coordinating body through the Spring 2018 intake process, with a secretariat function to facilitate consultations with the settlement sector, foster learning and exchange and help ensure alignment of programming.

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch, Settlement Sector

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #4b

Establish a pre-arrival working group with pre-arrival service providers and key partners, including domestic service providers, Provinces and Territories and ESDC.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Settlement Network, Settlement Sector, Provinces/Territories, Employment and Social Development Canada

Completion Date: Q3 2018/19

Recommendation #5

IRCC should strengthen performance measurement and reporting for pre-arrival services, by:

- Developing key indicators and data strategies to support collection of performance information

- Considering developing a targeted Performance Information Profile for pre-arrival services which aligns with IRCC's Settlement Program and Resettlement Program Performance Information Profiles

Response #5

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC recognizes that in order to ensure high-quality, client focused and effective and efficient services, pre-arrival programming needs to be measured and analysed on an ongoing basis and will seek to strengthen its approaches to performance measurement and reporting.

Action #5a

Develop and implement a performance measurement and data strategy for pre-arrival that is aligned with IRCC’s Settlement and Resettlement performance information profiles.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Research & Evaluation, Settlement Network, Provinces/Territories, Refugee Affairs Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #5b

Strengthen reporting of pre-arrival services delivered to refugees through a targeted service arrangement with the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Accountability: Settlement Network

Support: Research & Evaluation, International Network, Settlement Network, Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Completion Date: Q2 2018/19

Action #5c

Create management tool (e.g. dashboard) for regular and ongoing tracking of client uptake and profiles, to support responsive programming.

Accountability: Settlement and Integration Policy Branch

Support: Research & Evaluation, Settlement Network

Completion Date: Q3 2018/19

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Pre-Arrival Settlement Services, hereafter referred to as pre-arrival services, for fiscal years (FY) 2015/16 to 2017/18. The evaluation was conducted to inform IRCC’s Intake Process for pre-arrival services in Spring 2018. It is also being conducted in fulfillment of requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on Results and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.Footnote 2

The scope of this evaluation included in-depth analyses using multiple lines of evidence, focusing primarily on the outcomes for both immigrants and refugees that had accessed pre-arrival services. The evaluation also assessed other elements such as the effectiveness of IRCC and Service Provider Organization (SPO) promotion and its impact on uptake, and delivery models (e.g., web-based vs. in-person), and overall program management.

1.2. Pre-Arrival Services Background and Context

The objective of IRCC’s pre-arrival services is to provide selected Permanent Residents,Footnote 3 including refugees, with accurate, relevant information and supports so that they can make informed decisions about their new life in Canada and begin the settlement process (including preparation for employment) while overseas. It is expected that these services will enable clients to be better prepared upon arrival to Canada to settle and integrate into Canadian society.

1.2.1. History and Evolution

The Government of Canada has funded the delivery of pre-arrival services since 1998. While initially only provided to refugees, services were expanded to non-refugee immigrants in 2001 (see Figure 1).

An evaluation of pre-arrival services was completed in July 2012.Footnote 4 This evaluation concluded that while overall clients found pre-arrival services useful, there was no formal articulated common approach or framework in place for the provision of pre-arrival services.

In 2014, IRCC launched a Call for Proposals to expand pre-arrival services and increased funding from $9M in 2014/15 to $24M in 2015/16 and $32M in 2016/17. The intent was to provide more comprehensive tailored in-person, and web-based pre-arrival orientation and supports. This call resulted in funding for 27 SPOs through 28 contribution agreements (CA). Prior to this expansion, only three SPOs delivered these services: Colleges and Institutes Canada (CICan),Footnote 5 SUCCESS, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In FY2014/15, the fiscal year prior to the expansion, these three SPOs provided pre-arrival services to 19,455 clients.Footnote 6

In June 2016, the Department conducted an internal Management Review of the expanded pre-arrival services. Although minimal data was available, the Review highlighted a number of implementation challenges requiring action by the Department (see Section 6.4). To provide the Department and service providers with more time to put in place new operational measures, a decision was made to extend 23 out of 28 CAs for one year to March 31, 2018, for a total value of approximately $27.2M for FY2017/18.Footnote 7

Figure 1: Evolution of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

Source: Internal program documents.

Text version: Figure 1: Evolution of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

| Refugees (in-person) | Economic and Family Class Immigrants (in-person) | Economic and Family Class Immigrants (in-person and online) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 - IRCC begins funding Canadian Orientation Abroad (COA) (only for refugees in countries where IOM involved in refugee processing) | Yes | No | No |

| 2001 - COA expanded to immigrants (Colombia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Turkey | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2005 - Canadian Immigration Integration Project (CIIP) Pilot beginsFootnote * (China, India, Philippines) | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2008 - IRCC begins funding Active Engagement and Integration Project (AEIP) (South Korea, Taiwan) | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2010 - CIIP transferred to IRCC (China, India, Philippines, United Kingdom + mobile sites) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2015 - Expansion to 27 service providers including both in-person and online services (Global online delivery with permanent in-person services in 15+ countries) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2017 - 23 service providers | Yes | Yes | Yes |

1.2.2. Types of Services

Pre-arrival services provide the same types of services as IRCC-funded in-Canada Settlement services, with the exceptions of Language Assessments and Language Training. Support Services such as interpretation and translation, childminding, as well as transportation are also provided by just over one third of pre-arrival SPOs to enable newcomers to access pre-arrival services.Footnote 8 Through contribution agreements, IRCC funds SPOs such as immigrant-serving agencies, industry/employment-specific organizations or educational institutions to provide the following types of pre-arrival services:

- Needs Assessments and Referrals (NARS): NARS are conducted to assess newcomers’ needs and link them to appropriate settlement and community-based services.

- Information and Orientation services (I&O): I&O services are offered to newcomers to provide relevant, accurate, consistent and timely settlement-related information and orientation that is needed to make informed settlement decisions, as well as promoting an understanding of life in Canada. Examples of I&O include settlement and labour market orientation sessions, general life skills development activities, etc.

- Employment-Related Services (ERS): ERS aim to equip newcomers with the skills, connections and support needed to enter into the labour market and contribute to the economy. Examples of ERS include resume screening, interview skills and practice, self-marketing and job-seeking skills, employment networking, pathways to foreign credential recognition, etc.

- Community Connections (CC): CC includes activities to support the two-way process of integration and facilitate adaptation on the part of newcomers and their host communities. Examples of CC include mentoring and matching newcomers with Canadians.

- Indirect Services (IS): IS includes activities that are not provided to newcomers directly but are designed to support the development of partnerships, capacity building and the sharing of best practices among SPOs. For example, indirect projects may focus on: developing new and innovative interventions, updating training content, conducting research, creating new tools as well as curricula, etc.

Pre-arrival services vary considerably in scope, delivery models and size (i.e., project funding and number of clients targeted).

For non-refugees, pre-arrival services are provided by both targeted and generalist SPOs. Targeted SPOs focus on providing information and support to specific sub-sets of newcomers. For example, some targeted SPOs are occupation-specific (i.e., only providing information for specific sectors or professions), regional-specific (i.e., only providing information for newcomers destined to certain provinces or regions), or Francophone SPOs (i.e., serving only Francophone newcomers).

As displayed in Table 1, a few targeted SPOs are both occupation-specific and regional-specific at the same time and a few are Francophone and regional-specific at the same time. Conversely, “generalist” SPOs provide information and services that do not focus on one particular sub-group of newcomers but instead provide pre-arrival services to all eligible newcomers.

Most pre-arrival services for non-refugees offer services via web-based platforms (e.g., information, needs assessment tools, webinars, live one-on-one needs assessments and counselling, virtual job fairs, etc.), while a few projects offer in-person services, primarily in top source countries.Footnote 9 Services to French speaking immigrants are offered by four Francophone SPOs as well as other SPOs who have French language capacity.

In FY2015/16, IRCC also funded 2 projects to provide only indirect services (i.e., projects not directly serving newcomers) including capacity-building and pre-arrival platform development for specific employment sectors.Footnote 10 Table 1 provides further details on the various types of pre-arrival services funded. Additional details regarding the various SPO types are provided in Section 2.2.

Pre-arrival services for refugees are provided via the Canadian Orientation Abroad (COA) Program which is delivered by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and includes a 3 or 5 day in-person orientation session.Footnote 11,Footnote 12

Table 1: Profile of Pre-Arrival Services

| Type of Service | Generalist SPOs | Targeted SPOs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provide in-person services | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Provide only online services | 4 | 13 | 17 |

| Total | 9 | 16 | 25 |

| Targeted SPOs - Specific Sub-Sets of Newcomers | Generalist SPOs |

|---|---|

| Francophone | 2 |

| Occupation-Specific | 6 |

| Regional-Specific | 4 |

| Francophone and Regional-Specific | 2 |

| Occupation-Specific and Regional-Specific | 1 |

| Other (i.e., serving only refugees) | 1 |

| Total | 16 |

Source: GCS, iCARE

1.2.3. Delivery Partners

Several distinct groups within IRCC play a role in the administration and management of pre-arrival services:

- Settlement and Integration Policy Branch is the lead on developing policy regarding pre-arrival services

- Settlement Network is responsible for managing contribution agreements with pre-arrival SPOs and providing functional guidance – some contribution agreements are managed within National Headquarters and some are managed within IRCC’s Regional Offices across Canada

- International Network is responsible for processing PR applications and in some instances has supported promotional efforts to liaise with pre-arrival SPOs and promote pre-arrival services within IRCC Missions/visa offices abroad

- Centralized Network has been involved in developing a standardized invitation letter to inform prospective clients of the availability of pre-arrival services

- Communications Branch has been involved in developing IRCC’s pre-arrival services websiteFootnote 13

In addition to IRCC and pre-arrival SPOs, a variety of stakeholders and partners play key roles in supporting the overall integration process for newcomers.

- Provinces and Territories provide funding (along with IRCC) for settlement services in Canada. Provinces/Territories also provide settlement information support and services (including websites which can be accessed by newcomers prior to their departure for Canada) in areas such as language training, labour market integration, recognition of foreign credentials, business development and youth integration. They also work with the Government of Canada on foreign qualification recognition issues.

- In-Canada Settlement Service Provider Organizations provide information and support to newcomers upon arrival to support newcomers’ settlement and integration. Many pre-arrival SPOs partner with in-Canada SPOs to provide referrals and ensure newcomers have a seamless continuum of settlement services upon arrival in Canada.

- Municipalities have developed websites and online resources which can be accessed by newcomers prior to arrival. Some also provide additional support to newcomers once in Canada (e.g., housing and public transportation).

- Other Federal Departments (e.g., Employment and Social Development Canada, Health Canada, Service Canada and Heritage Canada) fund various initiatives affecting newcomers, such as multiculturalism or foreign credential recognition initiatives and have also developed online resources which have been adopted by pre-arrival SPOs (e.g., Working in Canada Job Bank, National Occupation Classification system).

- Educational institutions offer bridging and training programs to help newcomers upgrade their skills once in Canada.

- Employers and Employer Associations, including Chambers of Commerce, Immigrant Employment Councils and Sector Councils play a role in supporting newcomer employment and the foreign credential recognition process.

- Regulators and Apprenticeship Authorities are responsible for licensure/trade certification and in some cases work with pre-arrival SPOs to provide industry-specific information to newcomers.

1.2.4. Location of Pre-Arrival In-Person Services

Since FY2015/16, eight SPOs have offered in-person pre-arrival services to newcomers either via permanent sites or temporary sitesFootnote 14 overseas. Of these SPOs, 3 provide in-person services in multiple countries, while 5 focus on providing services in only one country.

In-person pre-arrival services are provided in 35 countries

- Permanent sites are located in 23 countries

- Temporary sites are located in 12 countries

- Services are provided to refugees in 25 countries

- Services are provided to non-refugees in 17 countriesFootnote 15

Figure 2 provides a map of countries where in-person pre-arrival services are offered. A full listing of countries is provided in Appendix A.

Figure 2: Location of In-Person Pre-Arrival Services

For map details on locations of pre-arrival services, please see Appendix A

1.2.5. Cost of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

According to IRCC financial data, $61.7Footnote 16 million was expended on pre-arrival services between April 1, 2015 and August 31, 2017.

- $38.7 million (63%) was spent on funding SPOs which provide services in-personFootnote 17

- $23.0 million (37%) was spent on funding SPOs which provide services online only

In terms of IRCC’s Settlement Program components, just over half (55%) of pre-arrival expenditures fell under Information and Orientation, followed by Employment-Related Services (18%), Indirect Services (6%), Needs Assessments and Referral Services (5%) and Community Connections (3%).Footnote 18

As displayed in Figure 3, the largest share of pre-arrival SPO expenditures was spent on salaries and benefits (45%) followed by professional fees, consulting and administration (15%).

Figure 3: SPO Expenditures (April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017)

Source: GCS

Text version: Figure 3: SPO Expenditures (April 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017)

| Expenditures | % of Total |

|---|---|

| Salaries and benefits | 45% |

| Professional Fees and Consulting | 15% |

| Administration | 11% |

| Indirect Costs (e.g., rent, utilities) | 10% |

| Tools and Delivery Assistance | 7% |

| Customer Transport | 5% |

| Travel, accomodation and related costs | 5% |

| Assets | 1% |

| Publicity | 1% |

2. Pre-Arrival Services Profile

2.1. Clients and Non-Clients

iCARE administrative data was used to examine the profile of newcomers who were admitted to Canada between April 1, 2015 and August 31, 2017, including those who had used at least one pre-arrival service (i.e., pre-arrival clients) and those that had not accessed a pre-arrival service (i.e., pre-arrival non-clients). Overall, during this period, 30,163 newcomers (defined as non-refugees and refugees) used at least one-pre-arrival service and 382,733 had not used any pre-arrival services.Footnote 19

In addition, a separate analysis compared the socio-demographic profile of pre-arrival clients with clients of domestic IRCC-funded settlement services.

Overall, non-refugees (both pre-arrival clients and non-clients) have a higher level of education, greater knowledge of English/French than refugees (both pre-arrival clients and non-clients) and access pre-arrival services earlier but at a lower rate (see Section 6.1 for more details on uptake).

Non-Refugees

Key characteristics of the 19,726 non-refugeesFootnote 20 who have received at least one pre-arrival service and were admitted to Canada between April 1, 2015 and August 31, 2017 include the following:

- Immigration category: Most (87%) are economic immigrants and 13% are sponsored family

- Family status: Just over half (55%) are principal applicants and 45% are spouses or dependants

- Gender: Just over half (54%) are male

- Age: Just over three quarters (76%) are between the ages of 25 and 44

- Knowledge of Official Languages: Most (93%) have some knowledge of an official language

- Level of Education: Just over half (55%) have a Bachelor or Master’s degree

- Country of Citizenship: Just under three quarters come from the Philippines (42%), India (15%) or China (15%)

- Intended Province of Destination: Most are destined to Ontario (32%), Alberta (14%) or Quebec (13%)

- Type of Pre-Arrival Services Accessed: Nearly all (97%) access an Information and Orientation while most (83%) access a Needs Assessment and Referral ServiceFootnote 21

- Number of pre-arrival SPOs accessed: Most (78%) access services from 1 pre-arrival SPO

- Time at which services accessed: Around half (53%) access pre-arrival services 5 weeks or more before being admitted to Canada while 39% accessed services either in the same week as their admission to Canada (8%) or 1-4 weeks before being admitted to Canada (31%)

Figure 4: Non-Refugee Clients – Time from using Pre-Arrival Service to Admission

Source: GCMS & iCARE

Text version: Figure 4: Non-Refugee Clients – Time from using Pre-Arrival Service to Admission

| Time from Admission | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 13 weeks and more before admission | 23% |

| 5 to 12 weeks before admission | 30% |

| 1 to 4 weeks before admission | 31% |

| Less than 1 week before admission | 8% |

| After admission in Canada | 8% |

In addition, 75% of non-refugee pre-arrival clients aged 18 and above at time of admission and who have an intended occupation specifiedFootnote 22 intend to work in:

- Managerial occupations (19%)

- Professional occupations (NOC skill level A) (56%)

- Skilled and technical occupations (NOC skill level B) (21%)

- Intermediate and Clerical (3.7%) or Elemental and Labourers (0.3%) (NOC skill level C and D)

When comparing non-refugee pre-arrival clients with non-clients and clients of IRCC-funded domestic Settlement services, a higher proportion of pre-arrival clients:

- were male (54% of clients vs. 47% of non-clients and 45% of domestic clients)

- were between the ages of 25 to 44 (76% of clients vs. 56% of non-clients and 59% of domestic clients)

- were economic immigrants (87% of clients vs. 56% of non-clients and 64% of domestic clients)

- had ability in an official language (93% of clients vs. 80% of non-clients and 81% of domestic clients)

- had a Bachelor Master’s degree (53% of clients vs. 41% of non-clients and 44% of domestic clients)

Refugees

Key characteristics of the 10,437 refugeesFootnote 23 over the age of 10 who have received at least one pre-arrival service and were admitted to Canada between April 1, 2015 and August 31, 2017 include the following:

- Immigration category: PSRs were the largest group (48%) followed by GARs (44%) and BVOR (8%)

- Family status: Just over half (54%) are principal applicants and 46% are spouses or dependants

- Gender: Just over half (52%) are male

- Age: Just under half (48%) are between the ages of 25 and 44 while just over one third (34%) were between the ages of 10 to 24

- Knowledge of Official Languages: Most (63%) have no knowledge of an official language

- Level of Education: A small proportion (9%) have a Bachelor or Master’s degree

- Country of Citizenship: Syria (40%), Iraq (14%) or Eritrea (14%)

- Intended Province of Destination: Most are destined to Ontario (44%), Quebec (15%) or Alberta (12%)

- Type of Pre-Arrival Services Accessed: All (100%) access an Information and Orientation while only a small proportion (2%) access a Needs Assessment and Referral

- Number of pre-arrival SPOs accessed: Nearly all (~100%) access services from only 1 pre-arrival SPO (i.e., International Organization for Migration)Footnote 24

- Time at which services accessed: Most (80%) access pre-arrival services either in the same week as their admission to Canada (43%) or 1-4 weeks before being admitted to Canada

Few differences were observed when comparing refugee pre-arrival clients to non-clients and clients of IRCC-funded domestic Settlement services.

A full profile of pre-arrival service clients, non-clients and domestic IRCC-funded Settlement clients is presented in Appendix B.

2.2. Typology of Pre-Arrival Service Provider Organizations

Pre-arrival services funded by IRCC vary considerably in scope, delivery models and size (i.e., number of targeted clients and project funding).

Of the 27 SPOs that were funded since the beginning of FY 2015/16, 2 were providing indirect services, and 25 were targeted to provide direct services to clients. In terms of the 25 providing direct services to clients, the most common type of pre-arrival service provided by pre-arrival SPOs was Information and Orientation (84%), followed by Employment-related Services (76%), Needs Assessments and Referrals (56%) and Community Connections (32%).Footnote 25

In addition, other characteristics of the 25 pre-arrival SPOs providing direct services between FY 2015/16 and FY 2017/18 were as follows:

- Francophone organizations: 4 (16%) specifically targeted Francophone clients, while 13 (52%) were able to offer services in French

- Service delivery model: 8 (32%) offered services in-person (with some services online), 17 (68%) offered services only online

- Providing services in non-official languages: 9 (36%) offered services in local languages

- Pre and post-expansion organizations: 3 (12%) had been offering services prior to the 2015 expansion while 22 (88%) were added as part of the 2015 expansion

- Temporary sites: 3 (12%) delivered services in temporary delivery sites (in addition to permanent sites)

- Occupation-specific: 7 (28%) targeted specific professions

- Destination-specific: 7 (28%) targeted newcomers destined to specific locations in Canada

- Immigration classes: 10 (40%) targeted only economic immigrants, 1 (4%) targeted only refugees

- Project Funding (3 fiscal years): 5 (20%) under $1,000,000, 10 (40%) between $1,000,001 and $2,000,000, 3 (12%) between $2,000,000 and $3,000,000, 5 (20%) over $3,000,000

- Annual client targets: 7 (28%) target 0-250, 5 (20%) target 251-500, 5 (20%) 501-750, 2 (8%) 751-1,000 and 6 (24%) over 1,000

A full listing of pre-arrival SPOs and the services they provide is included in Appendix C.

3. Methodology

3.1. Evaluation Approach

The evaluation scope and approach were determined during a planning phase, in consultation with the IRCC branches involved in the design, management and delivery of pre-arrival services. The terms of reference for the evaluation were approved by IRCC’s Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee in September 2017, and the evaluation was conducted by the IRCC Evaluation team from September 2017 to January 2018.

3.2. Evaluation Scope

The evaluation focused on the impact of IRCC-funded pre-arrival services since FY 2015/16, and was guided by IRCC’s Settlement Program logic model, which outlines the expected immediate and intermediate outcomes for pre-arrival and domestic IRCC-funded Settlement services (see Appendix D for the logic model).

The primary areas of focus for the evaluation were:

- the extent to which pre-arrival services are providing refugees and other immigrants with accurate, relevant information and supports so that they can better prepare for life in Canada and begin the settlement process (including preparation for employment and foreign credential recognition) while overseas

- the effectiveness of promotion of pre-arrival services by IRCC and pre-arrival SPOs

- the extent to which pre-arrival services are providing refugees and other immigrants with linkages and pathways to accessing settlement services in Canada

- the efficacy of the various pre-arrival delivery models (e.g., web-based vs. in-person)

As a secondary focus, the evaluation also conducted a review of contextual and performance issues of pre-arrival services, and to the extent possible, identified gaps, management and program challenges to inform the continued value of delivering pre-arrival services.

Specific evaluation questions were developed to address these core issues.Footnote 26

3.3. Data Collection Methods

Multiple lines of evidence were used to gather qualitative and quantitative data from a wide range of perspectives, including pre-arrival service clients, stakeholders, and program officials.

Lines of Evidence

Newcomer Client and Non-Client Surveys

Two surveys were developed and administered to newcomers that were admitted to Canada between April 2015 and August 2017 with valid contact information, over the age of 18.

- Survey of non-refugee immigrants – the survey contained 48 questions and covered a variety of topics including awareness and usefulness of pre-arrival services and the extent of difficulties faced by respondents post-arrival in Canada. The survey was administered to newcomers who had accessed at least one IRCC-funded pre-arrival service and included a comparison group of newcomers who had not accessed a pre-arrival service. The survey was administered in English and French. A total of 4,303 non-refugee immigrants completed the survey (2,015Footnote 27 had accessed at least one pre-arrival service and 2,288 had not accessed a service, representing a 12.0% response rate).

- Survey of refugees – the survey contained 21 questions and focused on the awareness and usefulness of pre-arrival services. The survey was administered to refugees that had accessed at least one IRCC-funded pre-arrival service and included a comparison group of refugees that had not accessed a pre-arrival service. The survey was administered in English, French and Arabic. A total of 2,443 refugees completed the survey (1,448Footnote 27 had accessed at least one pre-arrival service and 995 had not accessed a service, representing an 8.7% response rate).

Survey results were weighted to ensure representativeness. With the weights applied, the profile of survey respondents reflects the overall population. The overall margins of error for the non-refugee immigrant and refugee surveys were +/-1.48% and +/-1.89%, respectively, with confidence intervals of 95% for both.

Interviews/questionnaires

Interviews/questionnaires were conducted with key stakeholders, including IRCC National Headquarters staff (15), IRCC Regional staff (20), IRCC International staff (9), SPOs (24) and Provincial/Territorial representatives (6). These key informants provided insight into the relevance and performance of pre-arrival services.

Administrative Data Analysis

Administrative data analysis included examining the socio-demographic characteristics of pre-arrival services clients as well as the specific services they received.

Information on planned SPO activities and targets was derived from IRCC’s Grants and Contributions System (GCS).

Data on client uptake and services received was obtained from IRCC’s Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE) which is a system used by SPOs to report on clients and services as per their Contribution Agreements. Information from iCARE is subsequently linked by IRCC with the socio-demographic client information obtained through immigration files contained in IRCC’s Global Case Management System (GCMS).

Financial Data Analysis

Financial data for pre-arrival services costs were analyzed using IRCC’s SAP financial system.

Document and Literature Review

A targeted review of key documentation was conducted to support an assessment of program relevance and provide context for various delivery models. Documentation sources included IRCC, SPO material, as well as academic literature.

Direct observation of service delivery and focus groups with newcomers post-services

Pre-arrival information sessions/workshops (15) to newcomers delivered by 7 different SPOs (both online and in-person) were observed to support an analysis of various delivery models.

Post-session focus groups were conducted (6) with 72 newcomers (both immigrants and refugees) to gain newcomer perspectives on the awareness and perceived usefulness of pre-arrival services immediately following the receipt of in-person services.

3.4. Considerations and Limitations

Overall, the evaluation design employed numerous qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The different lines of evidence were complementary and reduced information gaps and the results converged towards common and integrated findings.

A few limitations to this evaluation include:

- Only a small number of focus groups were conducted with pre-arrival clients – While insights were gained from conducting focus groups with clients directly following the receipt of pre-arrival services, due to limited number of sessions, focus group results are likely not representative of all immigrants or refugees and should be considered exploratory.

- Known under/over-reporting of pre-arrival clients in iCARE for some SPOs affected the confidence in client counts – iCARE only began to capture information on pre-arrival services in October 2015. As such, services provided during two quarters of the first fiscal year considered for this evaluation were missing. In addition, some SPOs have faced challenges in reporting clients, particularly refugees, in iCARE; this was also confirmed during the evaluation analysis. Despite these challenges, the evaluation was able to effectively estimate client uptake by comparing iCARE records with SPO client records as well by verifying with survey respondents whether they had received pre-arrival services (see Section 6.1).

- Other factors to which non-refugee client outcomes may be attributed – While the evaluation used multivariate regression models to isolate the unique impact of IRCC-funded pre-arrival services and certain socio-demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, country of citizenship, year of admission in Canada, etc.) on influencing client outcomes, it was not possible to control for all contributing factors such as learner motivation or all the different delivery models and curricula used by SPOs. Despite this, statistically significant results were obtained which allowed for robust inferences to be made about the contribution of pre-arrival services.

- Representativeness of the refugee survey – While survey results were weighted to ensure the profile of respondents is aligned to the profile of the targeted refugee population, a potential non-respondent bias remains, as the survey was only conducted online, in English, French and Arabic. As such, survey responses are more likely to represent the views of refugees who are literate in one of these languages and who were able to access the survey online.

Despite these limitations, the triangulation of the multiple lines of evidence, along with the mitigation strategies used in this evaluation were considered sufficient to ensure that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.

4. Relevance

4.1. Continued Need and Relevance for Pre-Arrival Services

Finding: There is a continued need to provide relevant and accurate settlement information and support to newcomers prior to their departure for Canada to accelerate their integration.

Finding: Newcomers’ need for pre-arrival services is influenced by several factors, including their socio-demographic characteristics and the availability of information and support provided by non-IRCC sources.

Both the literature reviewed and an analysis of data from IRCC’s Needs Assessment iCARE module confirmed the existence of gaps in knowledge, as many newcomers face a variety of challenges and have a variety of needs upon arrival (i.e., limited contacts or networks and unfamiliarity with Canadian institutions, how to find work or educational opportunities in Canada and dealing with cultural barriers).Footnote 28 For example, a review of pre-arrival needs assessments revealed that the three needs most frequently identified by non-refugees were to increase knowledge of life in Canada (95%), community and government services (94%) and working in Canada (86%). Some (30%) of non-refugee NARS clients also had non-IRCC needs that were identified, the most frequent being in the areas of education/skills development (26%), and employment (22%).

While literature and several IRCC surveys of newcomersFootnote 29 confirmed that many newcomers utilize multiple sources of information to fill these gaps, including post-arrival settlement services, websites, informal networks of friends or family in Canada, some key informants noted that many newcomers may either not be knowledgeable about or not have access to these sources until they come to Canada.

The main objective of providing settlement services prior to arrival is to further accelerate settlement and integration, as it is expected that by accessing these services newcomers become more informed about the settlement and integration process at an earlier stage and will take steps to better prepare for their eventual settlement and integration in Canada.

In particular, interviewees noted that pre-arrival services are designed to reduce information gaps and allow newcomers to be better prepared upon arrival in Canada by:

- Reducing stress both prior to coming to Canada and post-arrival

- Contributing to more realistic expectations of life in Canada and steps needed to successfully settle and integrate

- Allowing economic immigrants to begin searching for a job and the foreign credential recognition process earlier

While a few interviewees suggested that taking pre-arrival services may reduce the need for in-Canada settlement services, most noted that newcomers will still need support in Canada and explained pre-arrival services should be seen as complementary to post-arrival settlement services as they serve as the first step on the settlement service continuum by providing newcomers with tailored needs assessments and referral information on where to obtain more information and support once in Canada.

A few interviewees also suggested that requiring all newcomers to access at least one pre-arrival service could be beneficial. These interviewees cited the example of IRCC’s Atlantic Immigration Pilot, which currently requires all newcomers to receive a needs assessment from a service provider and develop a personalized settlement plan in order to be processed under the Pilot. These interviewees noted that there is likely an even greater need for non-Atlantic Pilot immigrants to receive a needs assessment and develop a settlement plan as, unlike Atlantic Pilot participants, most are not admitted to Canada with a prior job offer.

Variations in the need for pre-departure orientation

Key informants agreed the need for pre-arrival services differs by socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., immigration category, education, age, sex, country of origin, family status and knowledge of official languages) and stressed the need for flexible and tailored pre-arrival services to serve the unique needs of the newcomers.Footnote 30

Needs of Refugees

The need for pre-arrival services for refugees was noted in IRCC’s 2016 Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative, which found that the lack of pre-arrival services as part of the Syrian Refugee Initiative was a major gap which resulted in many of them “arriving in Canada lacking basic information, having gaps in knowledge, and arriving with assumptions.”Footnote 31

This finding was supported by interviewees, as nearly all indicated that refugees had a need for pre-arrival services to develop a very clear picture of conditions in Canada and of the expectations placed on them, and to help reduce the anxiety felt by refugees in the first weeks in a new country.

However among refugees, key informants suggested that camp-based refugees are more in need of specific information focusing on an overview of Canada, travelling and immigration procedures at the airport, while urban refugees have a greater need for employment-related information. This was supported during focus groups with urban privately-sponsored refugees who all stated they would like more pre-arrival information on the Canadian labour market and how to find a job in Canada.

Needs of Non-Refugees

The majority of interviewees felt that economic immigrants also have a need for pre-arrival services. However, many interviewees highlighted that the type of information needed varies based on a broad variety of factors such as level of education, occupation, country of origin.

Both interviewees and administrative data on services accessed indicate that, when compared with other immigration categories, economic immigrants generally seek more specific employment-related information and services (e.g., resume building, credential recognition, sector-specific labour market information). For instance, analysis of iCARE data indicates that 31% of economic immigrants who accessed pre-arrival services obtained employment-related services compared to 17% for family class immigrants and 0.3% for resettled refugees. In addition, a higher proportion of pre-arrival clients who were principal applicants accessed pre-arrival services as compared to spouses and dependants.Footnote 32 Many economic immigrants are also interested in receiving and benefit from non-employment focused information and orientation services about life in Canada (e.g., weather, culture, healthcare, laws, cost-of-living, etc.) that contribute to more realistic expectations about living in Canada and explaining the steps needed to successfully settle and integrate.

Interviewees were split on the need to provide pre-arrival services to Family Class immigrants. While some interviewees suggested that family class immigrants have a lower level of need for pre-arrival services, because they already have family members in Canada who can provide information and support, others noted that the information provided by family members in Canada is not always accurate or detailed enough to support the specific needs of Family Class immigrants.

Other socio-demographic characteristics

Aside from immigration category, some interviewees mentioned that women may require more specific information around Canadian cultures and gender equality. Similarly, individuals with higher levels of education and/or principal applicants may be more likely to require specific labour market information as opposed to those with lower levels of education or spouses/dependants. Youth was also mentioned as a particular group requiring specific information tailored to them. In terms of countries, some interviewees noted that type and level of needs differ according to the distance between Canadian culture and the culture of origin. For example, while individuals from Western countries also have a need for pre-arrival services related to foreign credential recognition and employment, they may have less of a need for information and orientation on Canadian culture and values.

5. Impact of Pre-Arrival Services

5.1. Usefulness of Pre-Arrival Services

Finding: Both refugee and non-refugee clients reported pre-arrival services to be useful in a number of areas including: preparing for the trip to Canada and knowing where to go to find help in Canada. In addition, non-refugees also found pre-arrival services helpful to prepare to look for a job in Canada.

Both non-refugee and refugee pre-arrival service clients reported a high level of satisfaction with the services they received.

Overall, 79% of non-refugees surveyed indicated that pre-arrival services were useful or very useful.

As indicated in Table 2, when asked about specific topics, the majority of non-refugee clients indicating that pre-arrival services helped them in a number of areas including preparing for the trip to Canada, knowing how to contact organizations that provide help in settling in Canada and understanding their rights, freedoms and responsibilities.

Table 2: Share of non-refugees indicating the information was helpful

| The information and support from pre-arrival services helped me… | Strongly disagree / Disagree | Strongly agree / Agree |

|---|---|---|

| prepare for the trip to Canada (e.g., right documents, clothes) | 8.5% | 91.5% |

| know how to contact organizations that provide help in settling in Canada | 11.7% | 88.3% |

| understand my rights, freedoms and responsibilities | 12.3% | 87.7% |

| meet my initial settlement needs (e.g., housing, transportation, banking, access to community and health services) | 14.1% | 85.9% |

| receive support from a mentor or matching arrangement in Canada (not including family) | 31.0% | 69.0% |

Source: Non-refugee survey

In addition, as indicated in Table 3, non-refugee clients also indicated that pre-arrival services helped them prepare to look for a job in Canada.

Table 3: Share of non-refugees indicating the information was helpful to prepare to look for job

| The information helped me… | Strongly disagree / Disagree | Strongly agree / Agree |

|---|---|---|

| understand job opportunities/prospects in Canada (e.g., types of jobs available, industries, employers) | 9.9% | 90.1% |

| understand the process to get a job (e.g., job search strategies, resume writing, attending interviews) | 10.8% | 89.2% |

| understand Canadian workplace culture and norms (e.g., worker rights and responsibilities, workplace behaviours) | 11.6% | 88.4% |

| know how to have my professional credentials and/or qualifications recognized | 12.1% | 87.9% |

| know how to get a job that matches my skills and experience (e.g., identifying skills, identifying ways to gain Canadian experience) | 14.9% | 85.1% |

| understand how to upgrade my skills to better integrate into the Canadian labour market | 16.5% | 83.5% |

Source: Non-refugee survey

Nearly all refugees surveyed agreed that the information session they attended was helpful: to prepare for the trip, to adjust to life in Canada and Canadian culture and to understand their rights, freedoms and responsibilities as well as other aspects of their resettlement in Canada (see table 4).

Table 4: Share of refugees indicating the information session was helpful

| The information helped me… | Strongly disagree / Disagree | Strongly agree / Agree |

|---|---|---|

| prepare for the trip to Canada (e.g., right documents, clothes) | 5.9% | 94.1% |

| to adjust to life in Canada and Canadian culture | 8.3% | 91.7% |

| understand my rights, freedoms and responsibilities | 9.9% | 90.1% |

| understand what I needed to do during my first few weeks in Canada | 10.6% | 89.4% |

| prepare for the difficulties I might experience when arriving in Canada | 14.8% | 85.2% |

| to have realistic expectations about my life in Canada | 14.8% | 85.2% |

| understand how the health care system works in Canada | 15.1% | 84.9% |

| use transportation in my community (taxi/cab, buses, trains, driver’s licenses, etc.) | 17.4% | 82.6% |

| learn about existing resources available to help me resettle in Canada | 17.5% | 82.5% |

| understand the Canadian school system | 18.5% | 81.5% |

| understand how to find a permanent place to live | 19.3% | 80.7% |

| understand Canadian money and banking | 22.9% | 77.1% |

| know how to contact organizations that provide help in settling in Canada | 24.3% | 75.7% |

| look for work | 24.9% | 75.1% |

| get my skills/training accepted in Canada | 31.4% | 68.6% |

Source: Refugee survey

Finding: Non-refugee clients feel more prepared when they first arrive in Canada compared to those who hadn’t taken pre-arrival services.

As indicated in Table 5, a higher proportion of pre-arrival clients, compared to non-clients, consistently reported having enough information prior to coming to Canada. As indicated in Table 5, the largest differences between pre-arrival clients were regarding: contacting organizations that provide help settling in Canada (27 percentage point difference between clients and non-clients), knowing how to have professional credentials or qualifications recognized (20 percentage point difference between clients and non-clients), and understanding Canadian workplace culture and norms (15 percentage point difference between clients and non-clients).

Table 5: Non-refugees level of information prior to coming to Canada

| Prior to coming to Canada, I had enough information to… | Client Yes |

Client No |

Non-Client Yes |

Non-Client No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| prepare for the trip to Canada (e.g., right documents, clothes) | 88.5% | 11.5% | 85.2% | 14.8% |

| meet my initial settlement needs (e.g., housing, transportation, banking, access to community and health services) | 77.1% | 22.9% | 69.8% | 30.2% |

| understand my rights, freedoms and responsibilities | 71.5% | 28.5% | 65.1% | 34.9% |

| know how to contact organizations that provide help in settling in Canada | 69.9% | 30.1% | 42.9% | 57.1% |

| know how to have my professional credentials and/or qualifications recognized | 62.9% | 37.1% | 42.8% | 57.2% |

| understand the process to get a job (e.g., job search strategies, resume writing, attending interviews) | 59.7% | 40.3% | 45.6% | 54.4% |

| understand Canadian workplace culture and norms (e.g., worker rights and responsibilities, workplace behaviours) | 57.7% | 42.3% | 42.5% | 57.5% |

| understand job opportunities/prospects in Canada (e.g., types of jobs available, industries, employers) | 56.4% | 43.6% | 44.0% | 56.0% |

| understand how to upgrade my skills to better integrate into the Canadian labour market | 51.6% | 48.4% | 38.0% | 62.0% |

| know how to get a job that matches my skills and experience (e.g., identifying skills, identifying ways to gain Canadian experience) | 49.6% | 50.4% | 35.9% | 64.1% |

Source: Non-refugee survey

Of the above topics, when controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, immigration category, level of education, country of citizenship), there were no statistically significant differences between clients and non-clients in terms of having enough information prior to coming to Canada to: prepare for the trip to Canada, meet their initial settlement needs or understand their rights, freedoms and responsibilities. This suggests that the differences between clients and non-clients for these aspects are more related to individual characteristics, than to the pre-arrival services received.

Finding: The majority of non-refugees did not feel they needed additional information from pre-arrival services. However, there are potential opportunities to provide refugees with a more realistic picture of common challenges they will face once in Canada.

Non-refugee clients surveyed were also asked if there were areas where more information or services would have been helpful.

Of the 13% who indicated that additional information about life in Canada would have been helpful, the following areas were most often identified:

- 24% cited employment-related information

- 13% cited information about daily life in Canada

- 9% cited information about regional and local specificities

While many refugees (63%) felt that the amount of information provided to them through the orientation sessions was appropriate,Footnote 33 about one third (31%) also felt they could have benefited from more information, especially in the areas of employment, education and health care. This was confirmed during focus groups with urban refugees as the majority indicated they would have liked to have more pre-arrival employment-related information and support.

Just over half of refugee clients surveyed felt the information provided to them about what to expect in Canada (56%)Footnote 34 and where to find help in Canada (53%) was accurate or very accurate.

Areas where refugee clients felt the information provided to them was less accurate were:

- Jobs in Canada (58% of those indicating the information on what to expect in Canada was not at all accurate or somewhat accurate)

- Cost of living (48% of those indicating the information on what to expect in Canada was not at all accurate or somewhat accurate)

- Financial supports (33% of those indicating the information on what to expect in Canada was not at all accurate or somewhat accurate)

Through observation of an orientation session for refugees, it was noted that the service provider did acknowledge that there will be an adaptation period to adjust to life in Canada, however they did not go into detail in terms of specific challenges that refugees may encounter (e.g., high cost of living, difficulty of finding employment and living on limited income/social assistance, etc.). Not providing more in depth information on these topics may have contributed to refugee perceptions of information not being accurate.

5.2. Alignment of Pre-Arrival Services Information with Specific Client Needs

Finding: Pre-arrival services are well aligned with specific client needs and the majority of client groups found pre-arrival information useful.

In order to measure whether pre-arrival service information was aligned with specific needs, the evaluation examined the extent to which material provided through each pre-arrival service is tailored for specific groups,Footnote 35 as well as whether any particular groups found pre-arrival service information not useful, thus indicating a potential misalignment with specific client needs.

As noted in Section 2.2, more than half (60%) of SPOs are targeted in that they only provide pre-arrival services to certain groups of newcomers (i.e., specific professions, specific destinations) suggesting a high degree of alignment with the needs of one particular newcomer group. Moreover, during interviews, all of the “generalist” SPOs noted that they attempt to provide tailored material or support for particular groups, with some developing specific material for specific source countries, immigration categories, regulated vs. non-regulated professions, etc.

IRCC interviewees noted that in general, pre-arrival services seem to be aligned with specific clients’ needs although there are opportunities to include more tailored services aligned with labour market needs and immigration flows, especially related to employment and labour market information or adapted to local destination. For example, while there are currently pre-arrival services specifically for IT professionals and nurses, there are no specific pre-arrival services for doctors or engineers. Despite this desire for more tailored services, it was also mentioned by several interviewees and observed that SPOs funded with a focus on very specific clientele may face difficulties in attracting clients because the pool of eligible newcomers is reduced.

Overall, few significant differences were observed between various non-refugee subgroups (e.g., gender, immigration category, marital status) in terms of perceived usefulness of pre-arrival services and nearly all subgroups examined found pre-arrival services useful.Footnote 36

In terms of refugees, as indicated in section 5.1, both Government-Assisted Refugees and Privately Sponsored Refugees generally found pre-arrival services helpful with no statistically significant differences observed between the two groups.

5.3. Clients gain knowledge of life in Canada and the Canadian work environment

Finding: Non-refugees that have accessed pre-arrival services reported knowledge of life in Canada at a higher rate than non-refugees that have not accessed pre-arrival services. Employment-related pre-arrival services had a positive impact on clients’ preparedness for the Canadian work environment.

Survey results indicate that non-refugees (both clients and non-clients) report a high level of knowledge of life in Canada upon arrival. However, as indicated in Table 6, a higher proportion of non-refugee pre-arrival clients consistently reported having a higher knowledge compared to non-clients. The largest differences between pre-arrival clients were in terms of knowing where to go for assistance to settle in Canada (22.3 percentage point difference between client and non-clients), being prepared to look for a job (10.0 percentage point difference between client and non-clients) and knowing what to do to settle (7.2 percentage point difference between clients and non-clients).Footnote 37

Table 6: Non-refugees’ knowledge of life in Canada upon arrival

| Knowledge | Client Disagree / Strongly disagree |

Client Agree / Strongly Agree |

Non-client Disagree / Strongly disagree |

Non-client Agree / Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I knew what I needed to do to settle in Canada | 8.2% | 91.8% | 15.4% | 84.6% |

| The information I had obtained about Canada prior to my arrival was accurate | 10.2% | 89.8% | 13.5% | 86.5% |

| My expectations about life in Canada were realistic | 12.6% | 87.4% | 13.7% | 86.3% |

| I knew where to go for assistance to help me settle in Canada | 13.2% | 86.8% | 35.5% | 64.5% |

| I was well prepared to look for a job in Canada | 25.2% | 74.8% | 35.2% | 64.8% |

Source: Non-refugee survey