Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative

In response to the Syrian refugee crisis, Canada resettled more than 40,000 Syrian refugees. This effort was an exceptional and time-limited situation which required additional resources as well as special measures which were temporarily put in place.

Although some things are unique to the Syrian resettlement initiative, they continue to inform our processes as we go forward to help all refugee populations. Learn more.

Evaluation Division

December 21, 2016

Ci4-160/2016E-PDF

978-0-660-07138-1

Reference Number: E1-2016

Download:

- Executive summary: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative (PDF, 342.99KB)

- Complete report: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative (PDF, 726.42KB)

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Immediate and Essential Needs

- 3. Settlement and Integration

- 3.1 Language

- 3.2 Early Economic Establishment

- 3.3 Knowledge and Skills to Live Independently

- 3.4 Development of Social Networks and Connections with Broader Communities

- 3.5 Satisfaction with Life in Canada

- 3.6 Resettlement and Settlement Differences by Gender

- 3.7 Resettlement and Settlement Differences by Age Group

- 4. Ongoing Considerations

- 5. Planning and Coordination

- 6. Lessons Learned

- Appendix A: Impact on Clients - Processing and Arrival

- Appendix B: Methodology

List of tables and figures

- Table 1-1: Socio-Demographic Profile of the Syrian Population (Wave 1)

- Table 1-2: Comparison of Adult Socio-demographic Profiles – Syrian Refugees (Wave 1) Compared to Resettled Refugees (2010-2014), Excluding Quebec

- Table 2-1: iCARE – RAP Services

- Table 2-2: Service/Help Received from a RAP SPO or Sponsor

- Table 2-3: Service/Help Received Mostly or Completely Met Their Immediate Needs

- Table 3-1: Difficulties since Arriving in Canada

- Table 3-2: iCARE - Language Assessment for Syrian Refugees

- Table 3-3: Self-Reported Taking Language Training

- Table 3-4: Reasons for Not Taking Language Classes

- Table 3-5: Currently Working in Canada

- Table 3-6: Seeking Employment

- Table 3-7: Reasons for Not Currently Looking For Work

- Table 3-8: Challenges in Finding Work

- Table 3-9: Knowledge and Skills Gained by Refugees

- Table 3-10: Satisfaction with Life in Canada

- Table 3-11: Sense of Belonging to Canada

- Table 3-12: Percentage of Adult Population who Accessed Settlement Services, by Gender

- Table 3-13: Percentage of Adult Population Who Accessed a Settlement Service and received Care for Newcomer Children, by Gender

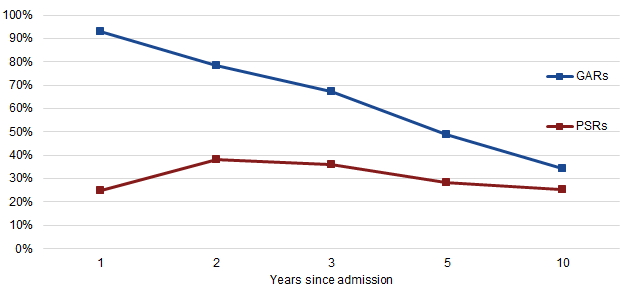

- Figure 4-1: Historical Social Assistance Rates by Category and Years since Admission

- Table 4-1: Paid a Sponsor to Come to Canada

- Table A-1: Satisfaction with Destined City or Town

- Table A-2: Self-reported Secondary Migration

Acronyms

- BVOR

- Blended Visa Office-Referred

- CA

- Contribution Agreement

- CLB

- Canadian Language Benchmark

- CPO-W

- Centralized Processing Office - Winnipeg

- GAR

- Government Assisted Refugee

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IFH

- Interim Federal Health

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- NAT

- Notice of Arrival Transmission

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- PSR

- Privately Sponsored Refugee

- RAP

- Resettlement Assistance Program

- RAP SPO

- Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organization

- RIE

- Rapid Impact Evaluation

- SAH

- Sponsorship Agreement Holder

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- UNHCR

- United Nations Refugee Agency (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees)

Executive summary

A Rapid Impact Evaluation (RIE) was conducted by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to assess the early outcomes of the 2015-16 Syrian Refugee Initiative. The evaluation was targeted in nature, and examined the Syrian refugees who were admitted to Canada between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016 and were a part of the initial 25,000 Syrian refugee commitment.Footnote 1

The evaluation focused on resettlement and early settlement outcomes for the Syrian population who were admitted as Government Assisted Refugees (GAR), Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR), and Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) refugees, as well as lessons learned and areas to monitor in the future. In addition, comparisons were made where possible to previous resettled refugees who arrived in Canada between 2010 and 2014.

Comparison to Previous Resettled Refugees

The evaluation found that adult Syrian GARs tend to be less educated and less knowledgeable of Canadian official languages compared to previous resettled refugee cohorts. Conversely, the adult Syrian PSRs are more educated have more knowledge of Canadian official languages compared to the resettled PSRs admitted between 2010 and 2014. The evaluation also demonstrated that adult Syrian refugees were less likely to be referred to employment services and had gained less knowledge and skills compared to previous resettled refugee cohorts. However, the evaluation found that they were more likely to be referred to language services.

Immediate and Early Resettlement and Settlement Outcomes

Overall, both GARs and PSRs reported that they were happy with their life in Canada. With regards to meeting the immediate and essential needs of Syrian refugees, PSRs were more likely to indicate that their immediate needs were met, and reported receiving more help to resettle compared to GARs. In addition, the evaluation found that due to expedited timelines of the initiative, some challenges occurred. Most notably those challenges included finding permanent housing, lack of consistency in the standards of RAP delivery, the adequacy of RAP income support for GARs and BVOR refugees, and a lack of reporting on RAP services.

Learning an Official Language

With regards to learning an official language, the majority of resettled Syrian refugees had their language assessed, however, fewer PSRs than GARs were enrolled in language training. Syrian GARs indicated that the main reasons for not taking language training were the lack of available lower level classes and lack of childminding spaces. Given GARs’ low language levels compared to other newcomers, many were unable to access employment services until a specific language level had been reached.

Employment

At the time of the survey, half of adult PSRs had found employment, compared to 10% of Syrian GARs. Of those who reported having a job, the most common form of employment for both GARs and PSRs were in the Sales and Service occupations. The vast majority of Syrian refugees who were not working at the time of the survey were looking for work or intended to look for work in the near future. The biggest challenge facing both GARs and PSRs in finding a job was associated with learning an official language.

Ongoing Considerations

Additional considerations were identified in the report regarding potential issues for the Syrian refugees moving forward. Considerations included Canada Child Benefit, transitioning to “month 13”, challenges for Syrian youth, mental health, concerns for family members still overseas, PSRs and BVOR refugees getting support from their sponsors, and the perception of favouritism towards Syrian refugees.

Lessons Learned

While the Syrian Refugee Initiative was a great success in many regards, the evaluation identified a few areas that should be taken into account to help ensure successful resettlement and settlement results.

The need for end-to-end planning for a major initiative

- IRCC should ensure that the resettlement and settlement considerations are fully integrated into the planning phase of future departmental refugee initiatives.

The need for accurate and complete refugee information

- It is essential that accurate and necessary refugee information (profile, destining, arrivals) is provided to IRCC staff, partners and stakeholders in a timely way.

Provision of pre-arrival services

- Providing pre-arrival/orientation to all refugees prior to coming to Canada is essential.

A focal point for stakeholder coordination and communication

- IRCC should consider having a focal point within the Department for future large-scale refugee initiatives to ensure effective and consistent stakeholder coordination.

Administrative information quality

- Full sociodemographic and contact information needs to be accurately captured for populations that arrive in Canada to allow for effective ongoing monitoring and results reporting.

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose of the Rapid Impact Evaluation

This Rapid Impact Evaluation (RIE) was conducted by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to assess the early outcomes of the 2015-2016 Syrian Refugee Initiative. The evaluation focused on resettlement and early settlement outcomes for the Syrian refugee population, examined implementation challenges, identified unmet needs, as well as lessons and opportunities.Footnote 2 Given the rapid nature of this evaluation, data collection took place between June and September 2016, and included focus groups with Syrian refugees, surveys with adult Syrian refugees, as well as other key lines of evidence.

The scope of this Rapid Impact Evaluation was targeted in nature, focussing on the commitment of 25,000 Syrian Refugees who arrived in Canada between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016 as Government Assisted Refugees (GAR), Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR) and Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) refugees. Syrian refugees who arrived in Canada prior to or after those dates were out of scope for this evaluation.Footnote 3 As Quebec is responsible for its own resettlement and settlement services, Syrian refugees destined to Quebec were not included in this evaluation, with the exception of the socio-demographic profile.Footnote 4

1.2 Operation Syrian Refugees

In November 2015, the Government of Canada committed to welcoming to Canada 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of February 2016Footnote 5, in a massive resettlement effort that would require collaboration between IRCC and other government departments (i.e., Department of National Defence, Canada Border Services Agency, Global Affairs Canada), international partners, provinces/territories, Service Provider Organizations (SPOs)Footnote 6, Sponsorship Agreement Holders (SAHs)Footnote 7 and community organizations. This whole of government initiative was delivered in five main phases, described below.

Phase I: Identifying Syrian refugees to come to Canada

The Government of Canada worked with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Jordan and Lebanon, and the Turkish Government to identify refugees. Vulnerable refugees who were a low security risk, such as women at risk and complete families, were given priority.Footnote 8 In addition, several thousand applications that were already submitted for PSRs and GARs were processed as part of this initiative.

Phase II: Processing Syrian refugees overseas

Once identified, Syrian refugees were processed overseas, mainly from three dedicated Canadian visa offices in Amman, Beirut and Ankara. Immigration processing, full immigration medical exams and security screenings were conducted overseas. If successful, refugees were given Canadian permanent resident visas.

Phase III: Transportation to Canada

Flights organized by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) brought refugees from the three main visa offices to designated ports of entry (POE) in either Montreal or Toronto.

Phase IV: Welcoming in Canada

Once refugees arrived at Toronto or Montreal airports, they were met by Government of Canada officers in designated Welcome Centres specifically set up for the admission of Syrian refugees. Syrian refugees were processed by border services officers, set up with social insurance numbers, screened for signs of illness, etc. Prior to moving on to their final destination in Canada, refugees then stayed at temporary hotels to rest and allow time for the reception communities to prepare to welcome them.

Phase V: Settlement and community integration

Once Syrian refugees arrived at their final destination across Canada, immediate settlement needs were provided through Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organizations (RAP SPO) or private sponsors. As they settled into their communities, resettlement assistance programming and settlement programming were provided to the Syrian refugees to meet their integration needs. This phase is still ongoing and is the focus of the current study.

1.3 Profiles of the Resettlement and Settlement Programs

Syrian refugees were processed and admitted to Canada via one of the following three resettlement programs.

- Syrian Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR) were referred to Canada by the United Nations Refugee Agency or the Turkish Government. GARs are supported by the Government of Canada who provides initial resettlement services and income support for up to one year.Footnote 9 Since 2002, the GAR program has placed an emphasis on selecting refugees based their need for protection.Footnote 10 As a result, GARs often carry higher needsFootnote 11 than other refugee groups. GARs are also eligible to receive resettlement services provided through a service provider organization that signed a contribution agreement to deliver these services under IRCC’s Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP).

- Syrian Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR) were sponsored by permanent residents or Canadian citizens via one of three streams: Sponsorship Agreement Holder, Group of Five, or Community Sponsors. In each of these PSR streams, sponsors provide financial support or a combination of financial and in-kind support to the PSR for twelve months post arrival in Canada, or until refugees are able to support themselvesFootnote 12, whichever comes first.

- Syrian Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) refugees were referred by the UNHCR and identified by Canadian visa officers for participation in the BVOR program based on specific criteria. The refugees’ profiles were posted to a designated BVOR website where potential sponsorsFootnote 13 can select a refugee case to support. BVOR refugees receive up to six months of RAP income support from the Government of Canada and six months of financial support from their sponsor, plus start-up expenses. Private sponsors are responsible for BVOR refugees’ social and emotional support for the first year after arrival, as BVOR refugees are not eligible for RAP services.

After arrival in Canada, Syrian refugees have access to the following two newcomer resettlement and integration programs.

- Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) funds the provision of immediate and essential services (i.e., reception at port of entry, temporary accommodation, assistance in finding permanent accommodation, basic orientation and links to settlement programming and federal and provincial programs) to GARs and other eligible clients through service provider organizations. Similar to BVOR refugees, GARs also receive monthly income support (based on provincial social assistance rates) which is a financial aid intended to provide monthly income support entitlements for shelter, food and incidentals. In the case of GARs, this income support is provided for up to one year or until they become self-sufficient, whichever comes first.Footnote 14

- Settlement Program aims to support newcomers’ successful settlement and integration so that they may participate and contribute in various aspects of Canadian life. Settlement refers to a short period of mutual adaptation between newcomers and the host society during which the government provides support and services to newcomers, while integration is a two-way process for immigrants to adapt to life in Canada and for Canada to welcome and adapt to new peoples and cultures.Footnote 15 Through the Settlement Program, IRCC funds service provider organizations (SPO) to deliver language learning services to newcomers, community and employment services, path-finding and referral services in support of foreign credential recognition, settlement information and support services that facilitate access to settlement programming.

RAP had to be modified from the traditional method of service offering to adjust for the influx of 25,000 Syrian refugees. Notable key differences included immediate RAP services were provided to Syrian GARs in hotels rather than in the traditional format (e.g., at RAP SPOs facilities) and larger group orientation sessions were provided to Syrian refugees, rather than smaller groups or one-on-one sessions for families.

1.4 Characteristics of Syrian Refugees Admitted in Wave 1 – Adults and Children

The majority of Syrian refugees admitted as part of this initiative were GARs (57.2%), followed by PSRs (34.1%) and BVOR refugees (8.6%). The socio-demographic characteristics of Syrian refugees were not uniform across all three groups, as seen in Table 1.1.

The profile of the PSRs group differ from the other two groups:

- PSRs tend to be older – 7.4% are 60 or older compared to 0.9% for Syrian GAR and BVOR refugees; in addition, 33.1% were less than 18 years old, compared to 60.0% for GARs and 56.6% for BVOR refugees.

- PSRs tend to have smaller family size – 48.9% were single versus 11.7% and 20.6% for GARs and BVOR refugees, respectively. Moreover, there were no PSR cases with family sizes higher than nine, compared to 40 GAR cases and 11 BVOR cases (0% vs 1.2% and 2.1%, respectively).

- PSRs settled in fewer provinces across the country – majority of the PSRs settled in Quebec (43.2%), Ontario (38.7%) and Alberta (11.8%). GARs’ intended provinces of destination were less concentrated, but tended to reside in Ontario (42.2%), Alberta (13.9%) and British Columbia (11.9%). Over half of the BVOR refugees settled in Ontario (53.9%).

- Almost a third of Syrian PSRs arrived in December 2015 with the influx of PSRs being concentrated in December and February, representing 71.6% of all Syrian PSR arrivals. GARs tended to arrive in early 2016, with 83.6% of all Syrian GAR arrivals occurring in January and February. BVOR refugee arrivals were heavily concentrated at the end of the initiative, with over half (51.4%) arriving in February 2016.

Table 1-1: Socio-Demographic Profile of the Syrian Population (Wave 1)

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 14,962 | 57.2% | 8,918 | 34.1% | 2,260 | 8.6% | 26,140Footnote ** | 100.0% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minors (less than 18) | 8,977 | 60.0% | 2,951 | 33.1% | 1,280 | 56.6% | 13,208 | 50.5% |

| Adults (18 and over) | 5,985 | 40.0% | 5,967 | 66.9% | 980 | 43.4% | 12,932 | 49.5% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 7,707 | 51.5% | 4,542 | 50.9% | 1,173 | 51.9% | 13,422 | 51.3% |

| Female | 7,255 | 48.5% | 4,376 | 49.1% | 1,087 | 48.1% | 12,718 | 48.7% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 18 | 8,977 | 60.0% | 2,951 | 33.1% | 1,280 | 56.6% | 13,208 | 50.5% |

| 18 to 29 | 1,950 | 13.0% | 1,668 | 18.7% | 340 | 15.0% | 3,958 | 15.1% |

| 30 to 39 | 2,535 | 16.9% | 1,526 | 17.1% | 415 | 18.4% | 4,476 | 17.1% |

| 40 to 49 | 1,076 | 7.2% | 1,307 | 14.7% | 160 | 7.1% | 2,643 | 9.7% |

| 50 to 59 | 289 | 1.9% | 804 | 9.0% | 45 | 2.0% | 1,138 | 4.4% |

| 60 or older | 135 | 0.9% | 662 | 7.4% | 20 | 0.9% | 817 | 3.1% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL | 196 | 1.3% | 15 | 0.2% | 36 | 1.6% | 247 | 0.9% |

| PEI | 106 | 0.7% | 70 | 0.8% | 14 | 0.6% | 190 | 0.7% |

| NS | 676 | 4.5% | 73 | 0.8% | 158 | 7.0% | 907 | 3.5% |

| NB | 1,208 | 8.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 129 | 5.7% | 1,337 | 5.1% |

| QC | 918 | 6.1% | 3,857 | 43.2% | 20 | 0.9% | 4,795 | 18.3% |

| ON | 6,316 | 42.2% | 3,453 | 38.7% | 1,218 | 53.9% | 10,987 | 42.0% |

| MB | 686 | 4.6% | 53 | 0.6% | 133 | 5.9% | 872 | 3.3% |

| SK | 1,004 | 6.7% | 20 | 0.2% | 49 | 2.2% | 1,073 | 4.1% |

| AB | 2,073 | 13.9% | 1,056 | 11.8% | 227 | 10.0% | 3,356 | 12.8% |

| BC | 1,779 | 11.9% | 307 | 3.4% | 260 | 11.5% | 2,346 | 9.0% |

| YK | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | 0.5% | 11 | 0.5% |

| Not Stated | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | 0.2% | 5 | 0.2% | 19 | 0.1% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 4 – 30, 2015 | 51 | 0.3% | 219 | 2.5% | 11 | 0.5% | 281 | 1.1% |

| December 1 – 31, 2015 | 2,353 | 15.7% | 2,937 | 32.9% | 436 | 19.3% | 5,726 | 21.9% |

| January 1 – 31, 2016 | 6,337 | 42.4% | 2,165 | 24.3% | 635 | 28.1% | 9,137 | 35.0% |

| February 1 – 29, 2016 | 6,158 | 41.2% | 3,446 | 38.7% | 1,161 | 51.4% | 10,768 | 41.2% |

| March 1, 2016 | 63 | 0.4% | 148 | 1.7% | 17 | 0.8% | 228 | 0.9% |

| GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | Total # | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 358 | 11.7% | 1,925 | 48.9% | 111 | 20.6% | 2,394 | 31.8% |

| 2-3 | 321 | 10.5% | 988 | 25.1% | 68 | 12.6% | 1,377 | 18.3% |

| 4-6 | 1,705 | 55.8% | 1,009 | 25.6% | 301 | 55.8% | 3,015 | 40.0% |

| 7-9 | 633 | 20.7% | 13 | 0.4% | 48 | 8.9% | 694 | 9.2% |

| 10 and more | 40 | 1.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | 2.1% | 51 | 0.6% |

Source: Global Case Management System.

1.5 Key Differences with the Syrian Adult Population

Finding: Adult Syrian GARs tend to be less educated and less knowledgeable of Canadian official languages compared to adult GARs admitted between 2010 and 2014. Conversely, the adult Syrian PSRs are more educated and have more knowledge of Canadian official languages compared to the resettled PSRs admitted between 2010 and 2014.

1.5.1 Comparing Syrian GAR, PSR and BVOR Refugees

As seen in the table below, when considering the Syrian adult population, PSRs tend to be:

- Older – 10.2% of the adult PSRs were 60 years or older, compared to 2.3% for adult GARs and 2.1% of adult BVOR refugees. Additionally, 56.0% of the adult Syrian PSRs were between the ages of 18 and 39, compared to 74.9% for the adult GARs and 76.8% for the adult BVOR refugees.

- More educated – 31.6% of the adult Syrian PSR had achieved some form of university education, compared to only 5.3% of the adult Syrian GARs and 3.1% of the adult Syrian BVOR refugees. Furthermore, a higher proportion of adult Syrian GARs (81.3%) had secondary education or less, compared to adult Syrian PSR and adult Syrian BVOR refugees (52.7% and 48.3%, respectively).

- More knowledge of Canada’s official languages – 18.2% of the adult Syrian PSRs indicated having no knowledge of English or French compared to 83.6% of the adult Syrian GARs and 51.0% of the adult Syrian BVOR refugees.

While interviewees indicated that the needs of Syrian refugees do not differ greatly from other resettled refugees admitted between 2010 and 2014, there are some characteristics that are unique to Syrian refugees admitted to Canada during the initiative.

1.5.2 Comparing Syrian Refugees to Other Resettled Refugees

The following sub-section compares the Syrian adult refugees to resettled refugees admitted to Canada between 2010 and 2014.

Syrian GARs tend to:

- Have lower education than resettled refugee populations, with 81.3% of GARs reporting secondary or less as their highest level of education. This is in comparison to 56.7% of GARs admitted from 2010 to 2014.

- Have less knowledge of official languages compared to previously resettled GARs, 83.6% of Syrian GARs reported knowing neither English nor French compared to 68.3% for previous cohorts of GARs.

- Have larger families than previous refugee cohorts, with 56.5% being comprised of 4 to 6 family members and 21.7% comprised of a family of 7 or more. In comparison, 23.7% of GAR cases admitted between 2010 and 2014 were comprised of 4 to 6 family members and 4.0% of cases were comprised of 7 or more. Families also were reported by SPOs to be comprised of younger parents.

Syrian PSRs tend to:

- Self-report higher knowledge of English (79.5%) compared to previous resettled refugees. In addition, the Syrian PSRs are the most educated group, compared not only to previous PSR cohorts, but for all GAR/BVOR refugee cohorts as well.

- Have more cases composed of 2 to 6 family members (51.1%), compared to 39.0% for other resettled refugees. Syrian refugees also tend to have fewer cases composed of a single person (48.4%) compared to previous resettled refugees (58.7%).

Syrian BVOR Refugees:

- Prior to the Syrian Refugee Initiative, fewer refugees were admitted to Canada under the BVOR program, making the differences among BVOR refugees difficult to measure given the small population size.Footnote 16 The total of BVOR refugees admitted in 2013 and 2014 (adults and children) was 216 and the Syrian Refugee Initiative represents a 453% increase over previous years (with 968 admissions).

Table 1-2: Comparison of Adult Socio-demographic Profiles – Syrian Refugees (Wave 1) Compared to Resettled Refugees (2010-2014), Excluding Quebec

| Resettled GAR | Syrian GAR | Resettled PSR | PSR Syrian | Resettled BVOR | Syrian BVOR | Resettled Total | Syrian Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Population (Excluding QC) | 16,244 | 5,630 | 15,943 | 3,310 | 216 | 968 | 32,403 | 9,908 |

| Resettled GAR | Syrian GAR | Resettled PSR | PSR Syrian | Resettled BVOR | Syrian BVOR | Resettled Total | Syrian Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 29 | 40.8% | 32.9% | 40.7% | 29.1% | 50.5% | 35.0% | 40.8% | 31.8% |

| 30 to 39 | 26.0% | 42.0% | 28.8% | 26.9% | 30.1% | 41.8% | 27.4% | 36.9% |

| 40 to 49 | 17.2% | 18.0% | 15.8% | 21.4% | 10.6% | 16.5% | 16.5% | 19.0% |

| 50 to 59 | 9.0% | 4.8% | 8.4% | 12.5% | 3.7% | 4.5% | 8.7% | 7.4% |

| 60 or more | 7.1% | 2.3% | 6.2% | 10.2% | 5.1% | 2.1% | 6.6% | 4.9% |

| Resettled GAR | Syrian GAR | Resettled PSR | PSR Syrian | Resettled BVOR | Syrian BVOR | Resettled Total | Syrian Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary or Less | 56.7% | 81.3% | 59.0% | 52.7% | 62.5% | 48.3% | 57.9% | 68.6% |

| Formal Trade Certificate, Non University Certificate | 4.7% | 4.4% | 11.0% | 12.9% | 2.8% | 4.0% | 7.8% | 7.2% |

| Some University and Above | 9.2% | 5.3% | 9.3% | 31.6% | 12.0% | 3.1% | 9.3% | 13.9% |

| None/Not Stated | 29.4% | 9.0% | 20.7% | 2.8% | 22.7% | 44.5% | 25.1% | 10.4% |

| Resettled GAR | Syrian GAR | Resettled PSR | PSR Syrian | Resettled BVOR | Syrian BVOR | Resettled Total | Syrian Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 27.1% | 14.4% | 45.0% | 79.5% | 13.9% | 47.2% | 35.8% | 39.3% |

| French | 2.7% | 0.5% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 2.1% | 0.7% |

| Both | 2.0% | 0.3% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 1.9% | 0.0% | 1.7% | 0.4% |

| Neither | 68.3% | 83.6% | 52.1% | 18.2% | 83.8% | 51.0% | 60.4% | 58.5% |

| Not Stated | -- | 1.3% | -- | 0.2% | -- | 1.3% | -- | 0.9% |

| Resettled GAR | Syrian GAR | Resettled PSR | PSR Syrian | Resettled BVOR | Syrian BVOR | Resettled Total | Syrian Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 51.0% | 11.4% | 58.7% | 48.4% | 57.3% | 20.2% | 54.8% | 26.7% |

| 2-3 | 23.7% | 10.4% | 20.9% | 24.7% | 26.1% | 12.6% | 22.3% | 16.2% |

| 4-6 | 21.3% | 56.5% | 18.1% | 26.4% | 15.9% | 56.1% | 19.7% | 44.7% |

| 7-9 | 3.5% | 20.5% | 2.1% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 9.0% | 2.8% | 11.6% |

| 10 and more | 0.5% | 1.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.1% | 0.3% | 0.8% |

Source: Global Case Management System.

Note: Does not include Syrian refugees destined to Quebec or those who had a Certificat de sélection du Québec.

1.5.3 Other Overall Differences in the Syrian Population

The following is a list of characteristics that are specific to the Syrian population, along with potential challenges for the future.

- Dental Health: Dental health needs were identified by stakeholders as the most pressing and unique needs for the Syrian population. As partial dental coverage is provided under the Interim Federal Health (IFH) program, some provinces and local communities have been providing additional services. For example, the Healthy Smiles Ontario program allows for low-income children to receive dental services at some Community Health Centres.Footnote 17 In addition, due to the strong public engagement, some dentists also offered pro-bono services/treatments.

- High Medical Needs: It was noted during site visits and interviews that vulnerable refugee populations tend to have high medical needs and this has been especially true for Syrians. During this initiative, a pediatrician at the Welcome Centre in Toronto noted health conditions in Syrian children “ranging from seizures to developmental disorders, to blood transfusion dependent thalassemia and childhood cancers.”Footnote 18 Services (e.g., home care services, caregivers for Arabic speakers, etc.) are currently lacking to support specific needs. It was observed in focus groups that lack of support for elderly immigrants with high medical needs (e.g., caregivers for Arabic speakers with Alzheimer’s), could prevent family members from accessing services as they are the sole source of support (given that home care services are generally not available to non-English or French speakers).

- Mental Health: Stakeholders and the literature also identified that mental health issues will become more pressing over time for the Syrian population as they continue to settle and feel safe. Issues likely to emerge over time include effects of post-traumatic stress disorder and mental health issues associated with the effects of war, displacement and loss.Footnote 19

- Family and Gender Differences: Stakeholders noted that that Syrian refugees are community-oriented and maintain strong connections with their cultural and religious communities. Some cultural differences include parenting (relying on the community to take care of the children, disciplining children, etc.), the rights and roles of women and the involvement of girls in society. Given these differences, SPOs indicated the need to build more awareness among the Syrian population about parenting and roles of women and girls in Canadian society.

- Social Media: Unlike any other refugee populations, social media and mobile applications are very commonly used by the Syrian refugees and the population who are actively connected to each other via mobile devices, specifically WhatsApp. However, this also caused some difficulties for SPOs, as refugees were comparing what Syrian friends received in terms of services in other cities and provinces and requested equivalent services and support.

2. Immediate and Essential Needs

The following two sections describe Phase V of the initiative – from departure of temporary accommodations, until the present time in a Syrian refugee’s settlement process.

2.1 Service Provision

Finding: Due to the expedited timelines of the initiative, some challenges occurred in the delivery of RAP services, namely consistency in standards of delivery and gaps in reporting.

Due to the rushed nature of the initiative and the large number of refugees arriving in a compressed time period, RAP orientation information was not always provided in a consistent way.

While all GARs should have received at a minimum one RAP service, a Departmental Lessons Learned report and site visits indicated that RAP SPOs were not able to provide orientation to Canada to the same standard provided to other refugees.Footnote 20 An example during a site visit indicated that the suite of what can be offered through RAP orientation sessions was not being completed by all refugees, as there were too many arriving at once, making it difficult to present on the information.

Some RAP SPOs mentioned that orientation sessions were provided to refugees as they waited at temporary hotels for other community services to be provided (i.e., vaccinations). Focus group participants indicated that the information received was not always adequate, as they could not focus on the presentation due to the distractions (e.g. more people per sessions, parenting at the same time of the sessions, etc.).

According to information reported in the Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE)Footnote 21, 88.8% of adult GARs had received RAP services, including reception at port of entry, temporary accommodations and initial orientation, among other services. While the expectations are that almost all GARs should have received at least one RAP service (at minimum port of entry and temporary accommodations), the most likely explanations for this is that RAP SPOs may not have yet reported all clients in iCARE and that the new RAP SPOs may not have had accessed to the RAP iCARE module.

| Syrian GARs # | Syrian GARs % | |

|---|---|---|

| RAP Services Received | 5,002 | 88.8% |

| Total # of Adult Syrian GARs Admitted (excluding QC) | 5,630 | 100.0% |

Source: IRCC Resettlement/Settlement Client Continuum. October 31, 2016.

Population includes Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1st, 2016, are 18 years of age or older and were initially destined to Quebec.

Note: iCARE does not capture data on Settlement and Resettlement services offered in Quebec.

2.2 Meeting the Needs of Syrian Refugees

Finding: Generally, PSRs reported receiving more help to resettle compared to GARs. PSRs were also more likely to indicate that their immediate needs were met.

Surveyed Syrian refugees were asked whether they had received information or help in different areas. Generally, PSRs reported receiving more help to resettle compared to GARs. The three largest differences were noted in receiving the following information or help:

- find a doctor on their own (GARs 38.8% vs. PSRs 63.9%);

- file tax forms (GARs 30.1% vs. PSRs 48.0%); and

- buy clothes, furniture and other things that refugees need (GARs 54.5% vs. PSRs 72.4%).

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| How to look for a place to live | 61.7% | 76.2% |

| How to rent a place to live (including signing a lease and your rights and responsibilities when renting) | 79.4% | 82.7% |

| How to shop for food | 69.9% | 83.0% |

| How to buy clothes, furniture, etc. | 54.5% | 72.4% |

| How to fill out tax forms | 30.1% | 48.0% |

| How to use public transportation | 78.9% | 77.5% |

| About cultural differences in Canada (e.g., the workplace, women and children’s rights, parenting, etc.) | 68.4% | 62.7% |

| How to find a doctor on your own | 38.8% | 63.9% |

| How to register your children in school | 58.9% | 57.7% |

| How to find child care so you can do other activities, such as work | 28.2% | 32.6% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

Of the surveyed refugees, 63.6% of GARs and 74.9% of PSRs indicated that their overall immediate and essential needs were mostly or completely met soon after their arrival in Canada.

The survey also asked if the information or help received met their needs. The majority of both GARs and PSRs reported that the information or help they received completely or mostly met their needs; however, PSRs were more positive than GARs on every topic. The differences between GARs and PSRs ranged from 10% for how to use public transportation (71.9% of GARs vs. 82.2% of PSRs) to a 29% on how to find a doctor on their own (where 55.7% of GARs indicated the information or help received completely or mostly met their needs vs. 85.5% of PSRs).

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| How to look for a place to live | 61.4% | 82.2% |

| How to rent a place to live (including signing a lease and your rights and responsibilities when renting) | 61.6% | 85.0% |

| How to shop for food | 62.2% | 83.9% |

| How to buy clothes, furniture, etc. | 63.1% | 83.2% |

| How to use public transportation | 71.9% | 82.2% |

| About cultural differences in Canada (e.g., the workplace, women and children’s rights, parenting, etc.) | 70.0% | 84.7% |

| How to find a doctor on your own | 55.7% | 85.5% |

| How to register your children in school | 71.7% | 87.1% |

| How to find child care so you can do other activities, such as work | 62.5% | 82.7% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

2.2.1 Orientation to Life in Canada

Information about life in Canada was provided to the refugees from a variety of sources – orientation at temporary hotels in Montreal or Toronto, information at RAP SPO facilities, occasional pamphlets overseas, etc. Through iCARE, SPOs have reported that a larger proportion of GARs have received information and orientation (95.9%), compared to PSRs and BVOR refugees (76.0% and 80.2%, respectively).

Syrian refugees reported that information sessions were provided in a rushed manner, as the majority of surveyed GARs and PSRs (73.5% and 80.8%, respectively) indicated that the information was provided to them too soon after they arrived in Canada.Footnote 22 A Departmental Lessons Learned report highlighted that some RAP SPOs had information pamphlets but even if they were available in Arabic, it would not have been helpful for those who were illiterate in their mother tongue.

Some refugees commented during focus groups that they had not received sufficient information regarding key settlement aspects, such as how to find a family doctor, how to find jobs, tenants’ rights and responsibilities/employee rights, labour market information (e.g., what does working under the table mean), etc. A few focus group participants explained that they had encountered situations in which they were unaware of the concept of their responsibility associated with a lease; they thought that they could sign a second lease without any penalties on the first one they had rented.

2.2.2 Food and Clothing

Syrian refugees indicated that they obtained help in finding food and clothing from various sources, including sponsors, RAP SPOs, friends, church members, community members and volunteers. These individuals helped refugees find grocery stores, provided advice on which food was halal, etc. Both GARs and PSRs surveyed (93.9% and 96.6%, respectively)Footnote 23 indicated that they understood how to shop for groceries and other necessities.

Food bank usage

It was noted by SPOs that the food allowance is low and that there were instances of refugees accessing food banks. This was supported by survey respondents: GARs were more likely to have accessed a food bank at least once (74.2%) in comparison to PSRs (50.2%). Of those who indicated that they have accessed a food bank, 24.8% of GARs and 23.0% of PSRs have frequently used a food bank (at least seven times since arriving in Canada).

2.2.3 Support Services

Considering that many Syrian refugees have a limited understanding of English/French and have large family sizes, support services for clients are crucial to ensuring that the Syrian refugees are able to access the settlement services they need, specifically the language training. The following support services were specifically highlighted in regards to the Syrian Initiative:

- Childminding: Childminding was identified by local IRCC office staff, SPOs and focus group participants as a critical component in ensuring that Syrian refugees have access to the services that they need. Stakeholders indicated that the wait for language training was longer if there was an additional need for childcare. Given the large family sizes, it was mentioned that four mothers could fill up all the childminding space for one language class. An additional challenge that was noted with support services is the current inability to fund childminding through RAP Terms and Conditions, as RAP SPOs cannot provide childminding services while GARs are accessing RAP services.

- Interpretation Services: Focus group participants also identified the limited interpretation services as an issue, especially for understanding information received from medical practitioners or school representatives. It was noted through some focus groups that it took a long time to get interpretation services, which is a particular issue when accessing specialized medical health services, as medical interpreters are difficult to find.

- Transportation: The issue of transportation allowances was exacerbated by the family size of Syrian GARs and as children are not eligible to receive transportation allowances under RAP funding. Highlighted as an additional financial burden for refugees, transportation costs (e.g., bus passes) are covered for adults under RAP, but not for children. Similar to the issue on childminding, as Syrian GARs have a higher number of children, bus passes for them can become quite costly for a group that already has limited funds.Footnote 24

2.3 Permanent Housing

Finding: While PSRs also had housing issues, finding affordable permanent housing was particularly difficult for GARs due to some specific challenges for this Syrian population.

The influx of Syrian refugees arriving in a short period of time and with a specific income range created challenges for the RAP SPOs to help find affordable housing. Furthermore, some RAP SPOs indicated that given that some landlords apply similar rules regarding subsidized housing, it was also difficult for large families to access to subsidized housing.Footnote 25 Interviewees indicated that the influx of arrivals caused competition for affordable housing among the Syrian population.

Finding affordable permanent housing is a challenge for all resettled refugees including Syrians, as the shelter allowance rateFootnote 26 is linked to provincial social assistance. Rental costs tend to be higher than the shelter allowance (e.g., as reported in the 2016 Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs, for a refugee living in Calgary, RAP allowance for shelter and other basic allowances is $610, while the average rent for a bachelor apartment in Calgary is $902),Footnote 27 thereby making it difficult to find affordable permanent housing.

Various initiatives were undertaken by SPOs, provinces and communities to help meet the housing need for Syrian refugees. Site visit interviewees highlighted that strong relationships developed between provinces, SPOs and landlords as part of the Syrian Refugee Initiative, in which provinces and SPOs made arrangements with landlords in various cities to provide rent to Syrian refugees at reduced prices for the first 12 months.

Provinces also found alternative solutions to help ease the burden of the refugee housing problems. For example, Syrian GARs in Manitoba were able to receive a Rent Supplement where the Province of Manitoba paid the difference between “market rental rates and rent-geared to income paid by the tenant for approved units”.Footnote 28 The province of New Brunswick provided up to 70% discount on the rent cost for the first 12 months.

An added difficulty to the housing situation was incorrect information being communicated directly to the Syrian refugees throughout the resettlement process (from overseas resettlement to arrival in the community). An example of this reported by SPOs and focus group participants was that some Syrians were under the impression that a house would be available to them upon arrival. This created false and unrealistic expectations on the part of the Syrian refugees, with regards to their permanent housing situation.

2.4 Financial Support

2.4.1 Financial Support for Syrian Refugees

Finding: RAP income support levels are inadequate to meet essential needs of Syrian GARs and BVOR refugees.

Several indicators confirmed that the level of RAP income support is inadequate to meet the essential needs of refugees. As the RAP income support rates did not change for the Syrian population, the inadequacy of income support was also reported in three previous evaluations, including the 2016 Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs.Footnote 29

When asked if the financial support received (either by the Government of Canada in the GAR cases or by their sponsor in the PSR cases) was enough to cover their basic necessities, 69.8% of GARs stated that it was not sufficient, compared to 26.1% of PSRs.Footnote 30 This is in contrast to the resettled refugee population, in which 47% of GARs and 13% of PSRs indicated it was not sufficient.

Twelve months of income support was indicated by GARs in focus groups as being not enough time to establish themselves in Canada, given the language barrier and the medical issues they have to overcome prior to accessing the labour market. Syrian refugees felt that their level of English was too low and would require a year at least to learn the language.

BVOR refugees also felt that financial support was insufficient and provided for a too short period of time. Some focus group participants reported having to stop language training and try to find employment because the financial support they received from their sponsors was insufficient or had ended.

Monthly income support entitlements for shelter, food and incidentals are guided by the prevailing provincial/territorial social assistance rates, which vary in each provinceFootnote 31 (e.g., for single adults, $610 per month in Vancouver, $555 per month in Halifax).Footnote 32 Singles and couples received the lowest amount of income support and reported having difficult time making ends meet (e.g., $376 is allocated for rent in Ontario for a single).Footnote 33 Because of the amount being tied to provincial social assistance rates, there is limited flexibility to adapt to the specific needs of the Syrian refugee population (i.e., shelter allowance for Ontario has allocations for up to six people, but yet, 22% of the GAR cases have a family size larger than six).

It was reported by RAP SPOs and Syrian refugees that the money received under the Canadian Child Tax BenefitFootnote 34 was being used to supplement the income received under RAP. The Child Tax Benefit helped provide an additional income for those with children.

Overall, timeliness of income support was perceived positively, with the exception of the initial start-up cheque, which RAP SPOs reported there being a time lag. This was viewed by RAP SPOs as being understandable given the influx of individuals. GARs and BVOR refugees in focus groups were pleased with the timeliness of their income support.

3. Settlement and Integration

Finding: While both GARs and PSRs identified learning an official language and finding a good job as their top difficulties, GARs also had issues with finding permanent housing, whereas PSRs had issues with getting their education/work experience recognized.

When asked what three things they had the most difficulties with since their arrival in Canada, surveyed Syrian GAR top responses were: 1) learning English and/or French and facing language barriers; 2) finding good quality housing; and 3) finding a good job. The Syrian PSR top responses were: 1) finding a good job; 2) getting education or work experience recognized; and 3) learning English and/or French and facing language barriers.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Finding a good job | 34.3% | 62.6% |

| Adapting to a new culture or new values | 12.5% | 12.4% |

| Learning English and/or French and facing language barrier | 55.1% | 32.7% |

| Getting education or work experience recognized | 19.0% | 40.1% |

| Finding good quality housing (e.g., good price, good quality, good neighbourhood) | 37.0% | 19.4% |

| Coping with financial constraints | 24.5% | 12.2% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

3.1 Language

As language barriers can hinder the integration process, language needs were identified as an issue for GARs, as 83.2% had self-reported not knowing either of the official languages. Fewer adult PSRs and adult BVOR refugees self-reported no knowledge of official languages (19.0% and 50.4%, respectively).

When asked in focus groups, the average Canadian Language Benchmark (CLB) was 2.6, which is considered low. Syrian refugees in focus groups highlighted the desire to learn English and a few PSR and BVOR refugees were disappointed that they were not able to pursue their English classes due to the need to work or not enough support from sponsors.

Finding: Although the majority of resettled Syrian refugees had their language assessed, fewer PSRs than GARs were enrolled in language training.

The majority of GARs surveyed (90.3%) reported being referred to language services and 81.4% of PSRs also reported being referred to language services.Footnote 35 More Syrian GARs reported being referred to language services compared to previous refugee populations (86%).Footnote 36

As indicated in Table 3.2, SPOs have reported in iCARE that 5,113 GARs, 2,652 PSRs and 830 BVOR refugees have undergone a language assessment. This represents a high proportion of Syrian refugees receiving a language assessment (90.8%, 80.1% and 85.7% of the GARs, PSRs and BVOR refugees, respectively).

| Adults | GAR # | GAR % | PSR # | PSR % | BVOR # | BVOR % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Assessment | 8,595 | 5,113 | 90.8% | 2,652 | 80.1% | 830 | 85.7% |

| Total # of Adult Syrian GARs Admitted | 9,908 | 5,630 | 100.0% | 3,310 | 100.0% | 968 | 100.0% |

Source: IRCC Resettlement/Settlement Client Continuum. October 31, 2016.

Population includes Syrian refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1st, 2016, are 18 years of age or older. Does not include Syrian refugees destined to Quebec or those who had a Certificat de sélection du Québec.

Note: iCARE data does not include services offered in Quebec.

Of those surveyed refugees, 94.5% of GARs reported having taken language classes compared to 77.6% of the PSRs. The majority of surveyed refugees have indicated enrolling in English language training and very few indicated enrolling in French language trainingFootnote 37.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Taken English Language Classes | 94.0% | 75.3% |

| Taken French Language Classes | 0.5% | 1.5% |

| Taken French and English Language Classes | 0.0% | 0.8% |

| Have Not Taken Language Classes | 6.0% | 22.9% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Due to rounding, totals may not equal 100%.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

Finding: Syrian GARs indicated that the main reasons for not taking language training were the lack of available lower level classes and lack of childminding spaces. For Syrian PSRs, it was that they are currently working or that no language training was needed.

As per Table 3.4, the two most common reasons for not enrolling in English/French classes for PSRs was because they were working (39.3%) or because there was no need to improve their language (38.6%). On the other hand, GARs indicated that the waiting for available language classes (38.5%) and the lack of childcare (23.1%) or distance from home (23.1%) were the main reasons for not taking language classes.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Classes are full, or there is a waitlist | 38.5% | 7.1% |

| No childcare offered | 23.1% | 4.3% |

| Childcare offered, but no spaces | 15.4% | 3.6% |

| I do not need to improve my English/French | 15.4% | 38.6% |

| I do not want to improve my English/French | 0.0% | 4.3% |

| I am too busy taking other courses or classes | 7.7% | 5.7% |

| I am working | 0.0% | 39.3% |

| Classes are too far away from home | 23.1% | 4.3% |

| Classes are not offered at convenient times | 15.4% | 9.3% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

Although language classes were identified by Syrian refugees as a major need, wait lists pose a problem to accessing the classes. Refugees in focus groups indicated waiting months for language classes due to general overflow (i.e., IRCC funded seats are not available, especially for lower level classes) or due to support services not being available (i.e., child minding).Footnote 38

Syrian refugees noted that they are also trying to learn English on their own, while they wait for language classes. For example, some are trying to learn how to communicate by using smartphones and Google Translate.

3.2 Early Economic Establishment

3.2.1 Employment Services

Finding: Although a higher proportion of Syrian PSRs were referred to employment related services compared to their GAR counterparts, fewer Syrian refugees were referred to such services compared to overall resettled refugees.

Surveyed Syrian PSRs (63.2%) are more likely to be referred to employment related services compared to Syrian GARs (27.3%).Footnote 39 In addition, overall Syrian refugees were less likely to be referred to such services compared to other resettled refugees (27.3% of Syrian GARs compared to 44% of resettled GARs; and 63.2% of Syrian PSRs compared to 83% of resettled PSRs).Footnote 40

In addition, GAR focus group participants indicated that they were not provided with enough information from their RAP SPOs regarding how to apply for jobs. As stated earlier, many refugees would have liked more information about employee rights, general labour market information such as what is working under the table, what is the minimum wage, etc.

Finding: Given GARs’ low language levels compared to other newcomers, many were unable to access employment services until a specific CLB level had been reached.

Interviewees indicated that providing settlement services such as employment services to clients with lower levels of English and French is difficult as most of the material is targeted at newcomers with at least some basic knowledge of official languages.

A Departmental Lessons Learned report indicated that a difficulty for Syrian refugees accessing employment services is due to the program requiring CLB 2 in English or French; however, most Syrians have lower language skills than CLB 2.Footnote 41 This prevents Syrian refugees from accessing employment services until they are at a satisfactory language level.

In addition, some Syrian refugees are illiterate in their native languages. Literacy and language classes are important in ensuring that Syrian refugees are able to learn a Canadian official language in order to be able to benefit from other settlement services or other community services.

Some Settlement SPOs have been creative in providing employment related services by creating Syrian specific initiatives, in developing working relationships with employers to develop employment fairs and connections. For example, MOSAIC in British Columbia provides employment services in both English and Arabic to provide employment information regarding training, compensation, regulations, breaks, etc.

3.2.2 Participating in the Labour Market

Currently Working

Finding: Half of adult PSRs had found employment, compared to 10% of Syrian GARs.

Of those surveyed, 9.7% of Syrian GARs and 52.8% of Syrian PSRs indicated they were currently working in Canada.Footnote 42 This finding, that a larger share of PSRs had found employment, was also corroborated by focus group participants.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 9.7% | 52.8% |

| No | 90.3% | 47.2% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

Finding: Of those who reported having a job, the most common form of employment for both GARs and PSRs were in the Sales and Service occupations.

The employment profile of GARs and PSRs are very similar. Almost half of the resettled Syrian refugees have found work in the Sales and Service occupation field (cashier, restaurant worker, grocery store, kitchen helper, cleaner, customer service, cook, etc.). The second highest occupation field was Trades and Transport occupation (construction, carpenter, technicians, welder, etc.) at 18%.

Looking for Work

Finding: The vast majority of Syrian refugees who were not working at the time of the survey were looking for work or intended to look for work in the near future.

When asked if they were currently looking for work, 43.4% of GAR survey respondents and 59.2% of PSR survey respondents indicated that they were currently looking for work.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| I am currently looking for work | 43.4% | 59.2% |

| I am not looking for work right now, but plan to look for work in the future | 54.1% | 31.2% |

| I don’t plan to work in Canada | 2.6% | 9.6% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

However, 54.1% of GARs and 31.2% of PSRs indicated that they intend to look for work, but are not currently looking. Reasons for not currently looking for work vary between GARs and PSRs. GARs top three reasons for not currently working include: taking language classes (84.8%); still receiving services to help learn about Canada (27.6%); and taking care of children (20.0%). The top three reasons for PSRs not currently looking for work, included: taking language classes to improve English/French (64.8%); taking care of children (22.7%); and waiting for credentials to be assessed (17.0%).

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Taking language classes to improve English/French | 84.8% | 64.8% |

| In school for something other than language | 13.3% | 14.8% |

| Still receiving services to help learn about Canada | 27.6% | 10.2% |

| Don’t know how to apply for jobs | 12.4% | 0.0% |

| Medical condition preventing from looking for work | 12.4% | 10.2% |

| Waiting until no longer receiving income support from the Government of Canada | 2.9% | 0.0% |

| Taking care of children | 20.0% | 22.7% |

| Waiting for credentials to be assessed | 4.8% | 17.0% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

Few survey respondents indicated that they do not plan on working, some of the reasons included age, health issues and looking after family members.

An additional difficulty regarding employment is the RAP income support clawback, in which RAP clients are allowed to earn up to 50% of their total monthly RAP income support payment before any deduction is made to the monthly income support. If additional income surpasses 50% of the monthly RAP entitlement, all RAP funds over that amount are clawed back on a dollar-for-dollar basis for each dollar earned over the allotted 50%.Footnote 43 Focus groups and interviewees highlighted that this clawback can be discouraging to finding employment.

Challenges in Finding Work

Finding: The biggest challenge facing both GARs and PSRs in finding a job was associated with learning an official language.

GARs indicated in focus groups that priority was placed on obtaining language prior to receiving employment services. As a result, GARs are not being connected to employment services and potential employment opportunities until later in their integration process. The most common response as to why surveyed refugees were not currently looking for work included taking language classes (82.1% for GARs, 54.8% for PSRs).

PSRs focus group participants indicated that they are having difficulty finding jobs for a variety of reasons, including: a lack of Canadian work experience; and not having their Syrian diplomas/credentials recognized.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| I need to improve my English/French language skills. | 82.1% | 54.8% |

| I am taking a course/training (e.g., school, language training, apprenticeship) to improve my skills. | 39.3% | 16.3% |

| I am still settling/adjusting to life in Canada | 32.1% | 18.1% |

| I have been told I am overqualified for the jobs I’ve applied for. | 2.4% | 6.6% |

| I have been told I don’t have enough Canadian work experience. | 16.7% | 31.9% |

| I’m not sure how to find a job in Canada. | 26.2% | 20.5% |

| I’m doing unpaid work or an internship. | 6.0% | 4.8% |

| I need to have, or am in the process of having my credentials/qualifications assessed. | 15.5% | 24.7% |

| I have not been able to find a job that matches my credentials/qualifications. | 10.7% | 14.5% |

| My qualifications were assessed as not equivalent to Canadian requirements. | 1.2% | 7.8% |

| There are not many jobs available in the area where I live. | 25.0% | 29.5% |

| There is a lot of competition for jobs in the area where I live | 6.0% | 13.9% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

3.3 Knowledge and Skills to Live Independently

All refugees are taught by RAP SPOs or sponsors how to complete a variety of activities associated with life in Canada – how to use public transportation, accessing health care, how to access community services and so forth.

| Resettled GARs | Syrian GARs | Resettled PSRs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Can use public transportation | 93% | 80.1% | 95% | 86.2% |

| Know how to get health care | 86% | 71.0% | 96% | 84.8% |

| Know how to enroll in school or further education | 80% | 55.7% | 89% | 72.1% |

| Know how to budget money | 87% | 62.5% | 93% | 75.0% |

| Know how to get the community services | 79% | 55.6% | 91% | 76.1% |

| Understand rights and freedoms in Canada | 89% | 92.1% | 95% | 96.6% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs; IRCC (2016) Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs.

Percentage of those who indicated agree or strongly agree.

Totals may not equal 100% as multiple options could be selected.

Note: Eligible respondents for both surveys include those who were 18 years of age and above, and residing outside of Quebec. Syrian Refugee Survey included adults who arrived in Canada between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016. Resettlement Refugee Survey included adult resettled refugees who arrived in Canada between 2010 and 2014.

With the exception of GARs’ understanding of rights and freedoms in Canada, all Syrian refugees had a lower level of understanding of Canadian activities than previous refugee populations. For GARs, the most notable difference between Syrian population and the resettled refugee population was around the knowledge of how to enroll in school or further their education and knowledge of how to access community services. For PSRs, the largest difference was in the knowledge of how to budget money.

3.4 Development of Social Networks and Connections with Broader Communities

While it is still early in the integration process, perspectives on whether Syrian refugees are making connections with broader Canadian community was mixed. Some SPO, SAHs and stakeholders indicated that there are instances of Syrian refugees remaining within their communities, while others indicated that Syrian refugees were doing well in connecting with the Canadian community. Common social network connections were through religious and community organizations.

Interviewees indicated that Syrian refugees formed connections through their common experiences – the plane rides to Canada and staying in the Welcome Centre hotels were cited as examples. It was reported that they are a very well connected group as social media use is extremely high (e.g., WhatsApp groups). Some stakeholders reported that due to the size of the refugee population that moved together, they have become linked and tend to network.

Interviewees indicated that children were integrating well and were experiencing few barriers. It was reported through focus groups that children are providing interpretation support to their parents as they are helping them communicate with different members in the community (e.g., teachers, school representatives, doctors, neighbours, etc.).

3.5 Satisfaction with Life in Canada

Finding: Overall, both GARs and PSRs are happy with their life in Canada.

When asked, the majority of Syrian GARs and PSRs (77% for both groups) indicated that they were happy or very happy with their lives in Canada.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Not at all + a little bit happy | 5.6% | 5.5% |

| Somewhat happy | 17.2% | 17.2% |

| Happy | 27.0% | 37.3% |

| Very happy | 50.2% | 39.9% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Totals may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

In addition, 90% of Syrian GARs and PSRs reported having a somewhat strong or very strong sense of belonging to Canada.

| Syrian GARs | Syrian PSRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Very weak | 1.9% | 1.7% |

| Somewhat weak | 4.6% | 3.6% |

| Somewhat strong | 18.1% | 28.1% |

| Very strong | 72.2% | 62.7% |

Source: Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative – Survey of GARs and PSRs.

Note: Surveys were only administered to those Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1, 2016, who were 18 years of age or older and residents outside of Quebec.

3.6 Resettlement and Settlement Differences by Gender

When examining the survey results by gender, minimal difference was observed between male and female clients.Footnote 44 iCARE data also indicates that there are minimal differences between men and women with regards to accessing settlement services.

| Syrian Female | Syrian Male | |

|---|---|---|

| Needs Assessment and Referrals | 84.1% | 86.2% |

| Information and Orientation | 87.8% | 88.5% |

| Language Assessment | 85.8% | 86.9% |

| IRCC Funded Language Training | 64.0% | 68.9% |

| Employment Related Services | 9.2% | 17.0% |

| Community Connections | 41.6% | 43.8% |

| Total Adult Population (Excluding Quebec) | 4,923 | 4,985 |

Source: IRCC Resettlement/Settlement Client Continuum. October 31, 2016.

Population includes Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1st, 2016, are 18 years of age or older and were not destined to Quebec.

Note: iCARE does not capture data on Settlement and Resettlement services offered in Quebec.

As noted in iCARE, 85.8% of Syrian women have had their language assessed and 64.0% are accessing IRCC-funded language training. This is very similar to Syrian men, of who 86.9% have had their language assessed and 68.9% are enrolled in IRCC-funded language training. Of those surveyed women who said they were not taking language training, the top two reasons were that they felt they did not need to improve their English/French, or they were working, compared to surveyed men, who indicated they were working or language classes were not offered at convenient times.

| Syrian Female | Syrian Male | |

|---|---|---|

| Needs Assessment and Referrals | 6.8% | 5.5% |

| Information and Orientation | 18.1% | 16.0% |

| Language Assessment | 3.8% | 2.1% |

| IRCC Funded Language Training | 18.4% | 4.7% |

| Employment Related Services | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Community Connections | 5.7% | 3.2% |

| Total Unique clients who accessed support services | 34.8% | 22.6% |

| Total Adult population (Excluding Quebec) | 4,923 | 4,985 |

Source: IRCC Resettlement/Settlement Client Continuum. October 31, 2016.

Population includes Syrian Refugees who arrived between November 4, 2015 and March 1st, 2016, are 18 years of age or older and were not destined to Quebec.

Note: iCARE does not capture data on Settlement and Resettlement services offered in Quebec.

In the survey, both men and women identified that childminding was a challenge for accessing language training. Surveyed women (8.8%) and men (11.4%) indicated that the reason they have not taken language training is due to no child care offered, or there were no spaces available.

With regards to employment, surveyed women were less likely than men to report that they were currently working in Canada (25.8% compared to 47.5%). Additionally, women were slightly less likely than men to indicate that they were currently looking for work or plan to look for work in the future (89.4% vs. 95.2%, respectively).

When asked what were their greatest difficulties since arriving in Canada, both surveyed men and women indicated finding a good job and learning English/French and facing a language barrier as their top two greatest difficulties. Where men and women differed in their results is in their third answer, as surveyed women were more likely to say that they had difficulty getting used to the weather, while men indicated that getting their education or work experience recognized was a challenge.

3.7 Resettlement and Settlement Differences by Age Group

Similar to gender, when examining the survey results by young adults (aged 18 to 24) and adults (aged 25 and older), overall, there were hardly any differences observed between the two groups.Footnote 45 For example, top three biggest difficulties since arriving in Canada had the same results for both young adults and adults.

One minor difference among results was that surveyed young adults were more likely than adults to have found a job in Canada (46.2% of Syrian young adults, compared to 40.1% of Syrian adults).

With regard to a sense of belonging to Canada, there was no difference between young adults and adults. The majority of surveyed Syrian young adults (91.6%) indicated having a somewhat strong or very strong sense of belonging to Canada, compared to 91.0% of Syrian adults (aged 25 to 64). Satisfaction with life in Canada was higher for surveyed young adults, with 81.2% reporting either being happy or very happy, compared to 77.9% of adults (aged 25 to 64).

4. Ongoing Considerations

The following section presents some of the identified ongoing considerations that are associated with Syrian Refugee Initiative moving forward.

4.1 Additional Financial Support

Canada Child Benefit

As Syrian refugees become permanent residents, they are eligible for the Canada Child Benefit, which is a tax-free monthly payment made to eligible families to help them with the cost of raising children under the age of 18.Footnote 46 Canada Child Benefit payments are calculated by taking into consideration the number of children living with the parent(s), the age of the children, as well as the family net income. As a starting point, for each child under the age of six, the family is entitled to receive annually a total of $6,400 (or $533.33 per month); and for each child between the ages of 6 and 17, the family is entitled to receive annually a total of $5,400 (or $450.00 per month). The payments are reduced proportionally when the family net income is over $30,000.

The following calculations were made based on the assumption that this income threshold was not achieved. Canada will be providing to Syrian families an estimated amount of $76.6M between July 2016 and June 2017 for child benefits.Footnote 47 This amount will fluctuate overtime as the family composition and children age change and as their family net income will augment.

Transition to Month 13

Concerns have been raised by interviewees, SAHs, SPOs and provinces regarding what will happen to Syrian refugees once the 12 months of RAP income support and financial assistance from the sponsors is set to finish. The issue of “month 13” has been raised as some additional supports were generally set up to only be available for one year (e.g., rent supplements, bus passes, etc.).

Only a few focus group participants knew about the social assistance and the majority were worried about month 13, given that they had not found jobs and did not know how they would survive without any support. It was unknown by many focus group participants that if a refugee has not found employment by month 13, a refugee is eligible to apply for provincial social assistance.

Figure 1 shows the historical social assistance rate for resettled refugees in Canada. The vast majority of GARs (93%)Footnote 48 received at least one month of social assistanceFootnote 49 after their first calendar year in Canada. This proportion steadily decreases with each passing year, with 34% reporting social assistance usage after 10 years of being in Canada. Conversely, a relatively small proportion of PSRs (25%) received social assistance following their first year in Canada. This proportion increases in years two and three, though begins to decline thereafter. By year 10, 25% of PSRs had reported social assistance.

Figure 4-1: Historical Social Assistance Rates by Category and Years since Admission

Text version: Figure 4-1: Historical Social Assistance Rates by Category and Years since Admission

Incidence of Social Assistance by category and Years since Admission

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GARs | 93% | 78% | 67% | 49% | 34% |

| PSRs | 25% | 38% | 36% | 28% | 25% |

Source: Longitudinal Immigrant Database (IMDB) 2013.

Incidence of Social Assistance is reported as the percentage of individuals who declared family social assistance income.

RAP income support is included as a social assistance benefit as RAP income support can be extended into year 1 (depending on the arrival date of the refugee within the tax year). The RAP income support is not included in the social assistance benefits after year 1.

Note: Special caution is needed to interpret these results as receiving one month of social assistance or 12 months is recorded in the IMBD in the same way.

Based on these historical trends, the split between GARs and PSRs and the monthly intake over the past years, the expected number of Syrian refugees who may be in need of social assistance can be estimated. This estimate produces a range of how many adults could be expected to apply for provincial social assistance in a given time period. It is expected that this need will peak in March 2017, with approximately 1,890 to 2,005 adults becoming possibly eligible to apply for provincial social assistance at that time.

4.2 Challenges for Syrian Youth