Evaluation of the Start-Up Visa (SUV) pilot

Research and Evaluation Branch

- Ci4-163/2017E-PDF

- 978-0-660-08008-6

- Ref. No.: E5-2015

Table of contents

- List of acronyms.

- Executive summary

- Evaluation of the Start-Up Visa (SUV) Pilot: Management Response Action Plan.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Findings – Program Management

- 4. Findings – Performance

- 5. Findings - Relevance

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: Logic Model for the Start-Up Visa Pilot

Table of contents

- Table 1.1: Cost of the SUV Pilot (FY 2013/14 – FY 2014/15)

- Table 4.1: Number of SUV Applicants (2013-2016)

- Table 4.2: Number of Landed SUV Immigrants (2013-2016)

- Table 4.3: SUV Application Decisions (Principal Applicants) (2013-2016)

- Table 4.4: Characteristics of SUV Principal Applicants Admitted to Canada

- Table 4.5: Language Ability - SUV Principal Applicant Applications (April 2013 - April 2016) (n=63)

- Table 4.6: Average IRCC processing time for 80% of SUV applications (2013 – 2015)

- Table 4.7: SUV Applicants: Core business activity and industry sector (n=80)

- Table 4.8: Designated Entity Investment Activity (April 2013-April 2016)

List of acronyms

- CABI

- Canadian Acceleration and Business Incubation Association

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CLB

- Canadian Language Benchmark

- CVCA

- Canadian Venture Capital & Private Equity Association

- EN

- Entrepreneur Program

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- NACO

- National Angel Capital Organization

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- IPG

- Integration Program Guidance Branch

- PT

- Province/Territory

- CPC-O

- Case Processing Centre - Ottawa

- SUV

- Start-Up Visa

Executive summary

Purpose of the Evaluation

The evaluation of evaluation of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Start-Up Visa (SUV) pilot was conducted in fulfillment of a departmental commitment to conduct an evaluation of the pilot, with the purpose of assessing its early outcomes. The evaluation covered a three-year period, starting with the launch of the pilot in April 2013, through to the end of April 2016 and used multiple lines of evidence to examine the relevance and performance of the program.

Start-Up Visa Pilot

Launched on April 1, 2013, the Start-Up Visa pilot was the first pilot program implemented through Ministerial Instructions. The Start-Up Visa was designed to attract innovative foreign entrepreneurs who would contribute to the new and innovation needs of the Canadian economy and facilitate entry of innovative entrepreneurs who would actively pursue business ventures in Canada.

There are currently 32 venture capital funds, six angel investor groups and 14 business incubators that have been designated to participate in the Start-Up Visa program. They are represented by their respective industry associations: the Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (CVCA), the National Angel Capital Organization (NACO), and the Canadian Acceleration and Business Incubation Association (CABI). These industry associations recommend entities for designation to the Minister and convene peer review panels to assist IRCC visa officers in case determinations.

Evaluation Findings

Program Management

- Finding #1: The pilot was implemented as intended, in that there were no major deviations in the design and core elements. However, a number of implementation and design challenges were identified that may have an impact on the future success of the pilot.

- Finding #2: Overall, communication and coordination within IRCC and between IRCC and stakeholders was viewed as effective. However, more coordination and collaboration between IRCC, ISED and GAC is necessary to maximize the success of the pilot.

Performance

- Finding #3: While the pilot received fewer applications and admitted fewer foreign entrepreneurs than the previous entrepreneur program, the evaluation found that SUV immigrants brought more human capital to Canada in terms of age, education, and knowledge of official language compared to immigrants under the previous program.

- Finding #4: The SUV pilot successfully facilitated the access to Canada for innovative entrepreneurs who have secured business commitments with designated entities. Timely processing and the availability of the work permit were noted as key elements that have contributed to the success of the pilot.

- Finding #5: Admitted SUV entrepreneurs are actively pursuing innovative business ventures in Canada. To date, positive progress was made by SUV entrepreneurs in either business growth, obtaining additional investment, increasing networks and business connections, or selling their business for a profit.

- Finding #6: In total to date, SUV pilot entrepreneurs received over $3.7M in investment capital from designated entities.

- Finding #7: While the support provided by designated entities was generally viewed as positive, some key informants noted a lack of transparency and delivery of agreed-upon support by some business incubators.

- Finding #8: There were minimal levels of fraud and misuse associated with the SUV pilot and the integrity mechanisms employed were successful in identifying issues. However, there is a potential program integrity gap regarding the monitoring of designated entities’ SUV activities.

- Finding #9: The cost to administer the SUV pilot was less than the previous entrepreneur program. The design of the Pilot, which requires designated entities to select innovative foreign entrepreneurs instead of IRCC visa officers, was advantageous from a cost-efficiency perspective.

Relevance

- Finding #10: There is a need for an entrepreneur immigration program like the SUV pilot to attract and retain innovative entrepreneurs that contribute to the innovation needs of the Canadian economy.

Conclusions and Recommendation

Overall, the findings of this evaluation are positive. IRCC implemented an innovative, low-cost program that has the potential to bring high-value entrepreneurs to Canada to start innovative businesses that contribute to the innovation needs of the Canadian economy. While the pilot was implemented as planned with low levels of reported program misuse, the evaluation found there were a number of implementation and design challenges that need to be addressed if the pilot were to become a Program. Based on these findings, the evaluation made four recommendations:

- Recommendation #1: The Department should implement measures to ensure that: the peer review process is risk-based, transparent and procedurally fair; the department has a clear mechanism for the de-designation of entities and implements a regular review process to ensure designated entities continue to qualify for designation; and, necessary program integrity measures related to industry associations and designated entities are in place.

- Recommendation #2: The Department should revise its current engagement approach with other relevant departments and stakeholders and develop a targeted Start-Up Visa promotion strategy.

- Recommendation #3: The Department should develop and implement a plan to increase awareness of the pilot and the related work permit requirements among frontline staff.

- Recommendation #4: The Department should develop a strategy that enables the consistent collection and reporting of pilot performance.

Evaluation of the Start-Up Visa (SUV) Pilot: Management Response Action Plan

Recommendation #1

IRCC should implement measures to ensure that:

- The peer review process is risk-based, transparent and procedurally fair

- IRCC has a clear mechanism for the de-designation of entities and implements a regular review process to ensure designated entities continue to qualify for designation.

- Necessary program integrity measures related to industry associations and designated entities are in place

Response #1a

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

Some improvements to the peer review process are needed to increase its transparency and procedural fairness.

IRCC also agrees that the process should be risk-based. To this end, in , IRCC removed the requirement that a peer review be conducted for all applications involving a commitment from a business incubator. Now, officers request a peer review if they are of the opinion that such an assessment would assist them in making a case determination (or on a random basis for quality assurance purposes). This matches the process that was already in place for applications involving a commitment from a venture capital fund or angel investor group.

Action #1a(i)

IRCC will send documentation on the process to designated entities (via industry associations) to ensure that they are aware of the criteria that are assessed in the course of a peer review. IRCC will also develop options to increase the transparency of the peer review process for applicants.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Support: Immigration Program Guidance Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Action #1a(ii)

Following changes made to the peer review process for business incubators in , IRCC will monitor the impact of these changes for one year, prepare a report, and determine whether further adjustments are required at that time.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Support: Immigration Program Guidance Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Action #1a(iii)

IRCC will consult with industry associations and designated entities to review all aspects of the peer review process and develop a strategy to ensure that it is procedurally fair for applicants and designated entities. This will include reviewing the criteria that are assessed and the process that industry associations follow when they carry out a peer review.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Support: Immigration Program Guidance Branch/Case Management Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Response #1b

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department recognizes that mechanisms for de-designation must be clarified and a regular review process for designated entities is needed to ensure that only qualified organizations participate in the program. This review will ensure that entities continue to meet the designation criteria that are part of IRCC’s agreements with industry associations. Entities that no longer qualify will have their designation revoked.

Action #1b(i)

IRCC will implement program changes to clarify the Minister’s authority to de-designate entities when warranted.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Support: Legal Services.

- Completion Date: .

Action #1b(ii)

IRCC will implement a formal process for industry associations to review the status of their designated entities on an annual basis.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Response #1c

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC agrees that greater program integrity measures related to industry associations and designated entities are needed.

Action #1c

In consultation with program partners, IRCC will develop program integrity measures that will build on industry standards and lay out clear expectations for the actions of industry associations and designated entities under the program.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Recommendation #2

IRCC should revise its current engagement approach with other relevant departments and stakeholders and develop a targeted SUV promotion strategy.

Response #2

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

A coordinated, targeted promotion and outreach approach would be beneficial for SUV. This will require consultation with Global Affairs Canada and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, as well as industry associations and designated entities.

The strategy will aim to widen designated entities’ networks abroad and potentially provide assistance to designated entities so they can better identify the type of high-value entrepreneurs that the program targets.

Action #2

IRCC, in consultation with partners, will develop a coordinated promotion and recruitment strategy.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Recommendation #3

IRCC should develop and implement a plan to increase awareness of the pilot and the related work permit requirements among frontline staff.

Response #3

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The value of increasing awareness of pilot requirements is recognized, particularly as they relate to work permit issuance, among the department’s network of decision makers.

Action #3

IRCC will review and update its current program delivery instructions and web content, as required, to address the need for further communication or clarification of SUV policies and processes.

In addition, IRCC will make any necessary changes/enhancements to ensure the appropriate placement and content of applicable web pages to optimize the information regarding the SUV program.

- Accountability: Immigration Program Guidance Branch.

- Support: International Network.

- Completion Date: .

Recommendation #4

IRCC should develop a strategy that enables the consistent collection and reporting of pilot performance.

Response #4

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

Administrative data related to SUV should be captured in a more systematic way to assist in performance measurement and program design. Implementation of system changes may require the technical support of the Solutions and Information Management Branch.

Action #4a

IRCC will assess its current data collection practices and develop options, including possible system changes, to address any data gaps in order to ensure that all key information about applicants and their business enterprise is captured consistently in departmental databases.

- Accountability: Immigration Program Guidance Branch.

- Support: Immigration Branch/Solutions and Information Management Branch/Centralized Network/Research and Evaluation Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Action #4b

IRCC will implement the selected option to address data gaps (date of completion may differ based on option selected). The extended timeframe is reflective of the need to create new data fields in GCSM, if required, to ensure consistency in data collection and reporting.

- Accountability: Immigration Program Guidance Branch.

- Support: Immigration Branch/Solutions and Information Management Branch/Centralized Network/Research and Evaluation Branch.

- Completion Date: .

Action #4c

IRCC will update its SUV performance measurement strategy to include performance measures that appropriately capture the desired outcomes, indicators and data sources of the SUV program.

- Accountability: Immigration Branch.

- Support: Research and Evaluation Branch.

- Completion Date: .

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Evaluation

This report presents the results of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Start-Up Visa (SUV) pilot. The evaluation was conducted from January to September 2016, in fulfillment of a departmental commitment to conduct an evaluation of the pilot, with the purpose of assessing its early outcomes.

The evaluation was designed to examine whether the pilot was implemented as planned, any management issues encountered, and to assess early progress towards expected outcomes. This evaluation provides findings and information to assist with decision-making with respect to the future of the pilot.

1.2. Background

1.2.1. Changes to the Immigration Entrepreneur (EN) Program

The Immigration Entrepreneur (EN) Program was one of three Business Immigration Programs operated by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC).Footnote 1 Under this program, applicants were required to have at least two years of business experience; have a minimum net worth of at least $300,000, and meet a number of conditions during the first three years in Canada.Footnote 2

While business immigration is a key component of Canada’s immigration system, the EN program was designed and implemented in 1978 when Canada’s economic priorities were different. The department determined that the EN program as designed was no longer well-aligned with Government priorities and directions. As a result, on July 1, 2011, the department implemented a moratorium on EN applications to limit the growth of the backlog while the program was reviewed; the program was subsequently cancelled in 2014.

Given the challenges with the EN program, the Economic Action Plan 2012 committed the department to building a fast and flexible immigration system including changes to Business Immigration Programs to target more active investment in Canadian growth companies and more innovative entrepreneurs.Footnote 3

In response to that commitment, the Department developed a new immigrant entrepreneur pilot program (the Start-Up Visa pilot) which was intended to better contribute to Government of Canada priorities related to innovation and productivity.

1.2.2. Start-Up Visa Pilot

The Start-Up Visa was designed to attract innovative foreign entrepreneurs who would contribute to the new and innovation needs of the Canadian economy and facilitate entry of innovative entrepreneurs who would actively pursue business ventures in Canada.

Launched on April 1, 2013, the Start-Up Visa pilot was the first pilot program implemented through Ministerial Instructions. The authority to create this program comes from section 14.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which enables the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to issue instructions that set out selection criteria for new, short-term programs under the economic immigration class. Selection criteria for the pilot are as follows:

- Commitment: Before applying to immigrate through Start-Up Visa, immigrant entrepreneurs must secure a commitment from a designated Canadian business incubator, angel investor group or venture capital fund to support their business concept.

- Investment: In the case of a venture capital fund, a $200,000 minimum investment in the entrepreneur’s business is required. For angel investor groups, the minimum investment is $75,000. There is no minimum investment amount for business incubators, but the entrepreneur must be accepted into the business incubation program.

- Other: In addition, applicants must demonstrate language proficiency in either English or French at Canadian Language Benchmark (CLB)/Niveau de compétence linguistique canadien (NCLC) level 5, possess a certain ownership share in their business,Footnote 4 and show that they have a sufficient level of fundsFootnote 5 to sustain themselves while in Canada.

There are currently 32 venture capital funds, six angel investor groups and 14 business incubators that have been designated to participate in the Start-Up Visa program. They are represented by their respective industry associations: the Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (CVCA), the National Angel Capital Organization (NACO), and the Canadian Acceleration and Business Incubation Association (CABI). These industry associations recommend entities for designation to the Minister and convene peer review panelsFootnote 6 to assist IRCC visa officers in case determinations. The peer review panel will only verify if the designated entity has performed due diligence according to industry standards, and will not provide an opinion as to the merits or feasibility of the business proposal itself.

Application Process

Before a foreign entrepreneur (or an entrepreneurial team of up to five individuals) applies under Start-up Visa, they must contact and receive support from a designated entity. If a designated entity decides to support their business, it will provide them with a letter of support. The designated entity will also send a commitment certificate directly to IRCC. Once the application package is received, IRCC will assess the application and may submit certain business proposals to an industry association for peer review as needed.

Delivery of the SUV Pilot

The pilot is delivered through the Centralized Processing Centre in Ottawa (CPC-O), Immigration Program Guidance Branch (IPG) and Immigration Branch (IB) within IRCC. CPC-O is responsible for processing SUV applications. IPG is responsible for providing operational direction to CPC-O and SUV stakeholders. IB is responsible for providing policy direction and support to IPG and SUV stakeholders.

Industry associations are responsible for providing support to designated entities and administering the peer review process. Designated entities are responsible for reviewing business proposals and deciding whether to invest in / formulate a business agreement with foreign entrepreneurs.

Industry Canada (now called Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada), provided support in the design and implementation of the SUV pilot.

Resources for the SUV Pilot

According to an analysis of IRCC financial information, the total cost of the pilot was $1.3 million over a two-year period (Table 1.1). Between April 2013 and April 2016, IRCC received 113 applications.

| Budget Item | FY 2013/14 | FY 2014/15 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total full-time equivalents | 2.28 | 4.94 | 7.22 |

| IRCC costsTable note * | $203,723 | $595,098 | $798,820 |

| Employee benefit plan | $91,413 | $104,428 | $195,841 |

| OGDs | $146,320 | $146,900 | $293,220 |

| Total | $441,456 | $846,426 | $1,287,882 |

Current Context

At the time of this report (October 2016), direction for the future of the SUV pilot was being considered. The findings from this evaluation will be used to inform the analysis, discussion and options.

2. Methodology

2.1. Questions and Scope

The evaluation of the pilot was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on ResultsFootnote 7 and examined implementation and issues of relevance and performance. The evaluation covered a three-year period, starting with the launch of the pilot in April 2013, through to the end of April 2016. The evaluation questions follow.

Evaluation Questions for the SUV Pilot

Relevance:

- What need is the Start-Up Visa pilot aiming to address?

Performance:

- Was the Start-Up Visa pilot implemented as intended? Were any management implementation issues encountered?

- To what extent has the pilot facilitated the access of foreign entrepreneurs to pursue business ventures in Canada?

- To what extent has the pilot demonstrated early progress towards expected outcomes?

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation took place between January and August 2016, and included multiple lines of evidence to help ensure the strength of information and data collected.

Lines of Evidence

- Document Review. Relevant program documents were reviewed to gather background and context on the SUV pilot, as well as to assess its relevance and performance. Documents reviewed include: government documents (such as Speeches from the Throne, Budget Speeches, and Reports on Plans and Priorities), documents related to the implementation of the pilot, and documents from Other Government Departments and industry associations.

- Interviews. A total of 47 interviews were conducted with five stakeholder groups, including: IRCC senior management and program officers (7); Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada representatives (2); Industry Association (3) and Designated Entity representatives (14); immigration lawyer (1); and SUV entrepreneurs (admitted to Canada) (20). Due to the small number of interviews in each interview group, a summary approach to the analysis was used to develop key themes.

- Program Data. Available performance data and financial data were used to provide information on the pilot. The Global Case Management System (GCMS) as well as data collected directly from interviews, commitment certificates, and from CPC-O’s SUV Excel database was utilized to determine the profile of SUV immigrants and businesses started. Financial data from IRCC’s Cost Management Model (CMM) were used to examine the cost of the pilot.

2.3. Limitations and Considerations

- Timing of the evaluation. At the time of the evaluation, the pilot had been implemented for three years. Therefore, the results reflect the implementation stages of the pilot and may not reflect longer term outcomes.

- Relatively low number of admitted SUV principal applicants interviewed. Shortly after interviews were completed with key informants, the number of admitted principal applicants doubled. Therefore, the profile of later applicants may be different than those that were interviewed as part of this evaluation.

- Data challenges. The evaluation was unable to provide a complete analysis of certain elements due to administrative data challenges. For example, administrative data related to SUV businesses is not consistently captured or linked to principal applicants in GCMS. Furthermore, information contained in commitment certificates was not consistently entered by designated entities and therefore did not allow for a complete assessment of data elements contained within. To mitigate this challenge, the number of proposed businesses were counted manually by trying to align the names of the applicants, the countries from which they applied and application date.

However, despite the limitations, the use of multiple lines of evidence ensured that the findings can be used with confidence.

3. Findings – Program Management

This section presents the findings of the evaluation, organized by the themes of implementation, performance, and relevance.

3.1. Design and Implementation of the Pilot

The pilot was assessed in terms of whether it was implemented as intended, the nature of any challenges experienced with implementation, and the level of coordination and communication within IRCC and between IRCC and partners.

3.1.1. Planned Versus Actual Implementation

Finding: The pilot was implemented as intended, in that there were no major deviations in the design and core elements. However, a number of implementation and design challenges were identified that may have an impact on the future success of the pilot.

The assessment of the implementation of the pilot was based on foundational documents and information gathered from interviews. The objective of the pilot was to put in place a function where private sector designated entities review business proposals from foreign entrepreneurs, industry associations act as a quality control mechanism, and IRCC processes applications. IRCC was successful in achieving this objective and in putting in place the process that allows foreign entrepreneurs to apply under the SUV pilot.

The evaluation found that there were no major deviations in the design of the program in terms of the core elements: the designation process, the peer review process, the usage of the commitment certificate and processing of immigration applications. However, the evaluation found that there were some minor modifications to the original plan that occurred after early implementation, including, removing the education requirement from the selection criteriaFootnote 8 and the creation of an email mailbox to manage inquiries from SUV stakeholders.Footnote 9

Implementation Challenges

Key informants identified the following pilot implementation key challenges:

- High number and low quality of unsolicited proposals received by designated entities: The majority of designated entity key informants noted that they received a large amountFootnote 10 of unsolicited business proposals after the launch of the SUV pilot, many of which were of low quality. In particular, it was noted that a significant proportion of unsolicited proposals were not realistic or scalable businesses and likely attempts to circumvent normal immigration procedures by applying under this pilot. The evaluation also found that many designated entities did not review all the proposals they received due to resource challenges.Footnote 11 In addition, many designated entities commented that they only review certain proposals referred to them through business networks, which is considered a standard industry practice. Lastly, many designated entities noted challenges undertaking the due diligence process with foreign entrepreneurs due to the lack of availability and reliability of information obtained from other countries.

- Promotion of the pilot: The launch of the SUV pilot was promoted through general promotional strategies (e.g., billboards in California, IRCC’s website, etc.). Overall, key informants were not supportive of these activities, suggesting that promoting the program broadly/generally attracts low-quality unsolicited proposals. Instead, many designated entities and IRCC key informants felt that targeted promotion (e.g., to educational institutions, start-up communities / organizations, and business connections through trade delegates overseas) would result in stronger proposals and would increase the success of the pilot. A potential improvement frequently noted by interviewees related to having trade delegates help designated entities navigate the start-up environment overseas and facilitate business opportunities with foreign entrepreneurs. Key informants from IRCC, ISED and designated entities noted that more could be done from a whole-of-government approach in attracting innovative entrepreneurs. ISED, IRCC, GAC, Provinces/Territories and designated entities could work together to further refine ways to attract innovative talent to Canada.

- IRCC operational awareness: Some IRCC/CBSA frontline staff did not understand SUV operational processes or were not aware that the pilot existed during the launch. This was most frequently noted when referring to the process for obtaining a work permit, which some applicants found difficult to obtain. While some of these knowledge gaps have been subsequently addressed, it is unclear whether all partners involved in the delivery of the pilot are aware of the specific operational guidance.

- Higher level of specialized operational service compared to other economic programs: Some key informants noted the SUV pilot requires more specialized service (“hand holding”) when dealing with stakeholders when compared to other economic immigration programs. This is due to the fact that stakeholders involved with the pilot are unfamiliar with the immigration process. To address stakeholder questions, a dedicated mailboxFootnote 12 was made available for designated entities. However, there was general acknowledgement across all key informant groups that SUV is a unique pilot with different clients/stakeholders (who have different needs) and therefore requires a different policy and operational approach.

Design Challenges

The following design challenges were identified by the Evaluation:

- Success of the program relies heavily on industry associations: The evaluation found that the pilot relies heavily on SUV industry association compliance to operate. This view was supported by some designated entities and IRCC key informants, who indicated that the pilot is at risk if industry associations do not comply with their responsibilities. This concern was mainly directed towards one Industry Association that stopped undertaking the peer review process, causing SUV processing times to increase.

-

Peer review process challenges: A peer review may be initiated by IRCC officers either if they are of the opinion that such an assessment would assist them in making a case determination or on a random basis for quality assurance purposes. Until June 2016, a peer review was also conducted for all applications involving a commitment from a business incubator.

Overall, the peer review function was considered useful to support visa officer decisions and for quality assurance purposes. However, some designated entities and industry associations raised concerns over the peer review process. In particular, the requirement to conduct a peer review for all applicants with a business incubator commitment was felt to be too resource intensive for industry associations and the designated entities conducting the peer review. It was also felt that peer reviews added significant time to the application process. Furthermore, key informants noted a lack of clarity around peer review criteria as well as the lack of ability for the applicant to provide additional information to the visa officer; the applicant is dependent on the designated entities to represent and submit the proper documentation to IRCC. Lastly, some designated entities noted that they were uncomfortable with peers reviewing their business commitments because of the small size of business incubator community and the potential risk if certain entities were to act unethically.

- Transparency concerns and lack of clear mechanism for the de-designation process: Some key informants expressed concerns about the transparency of the designation process with one industry association. In addition, while there are clear guidelines for industry associations relating to the de-designation of entities, IRCC does not have a clear mechanism for the de-designation of entities, which was reported to be a program integrity gap.

3.2. Communication and Coordination

Finding: Overall, communication and coordination within IRCC and between IRCC and stakeholders was viewed as effective. However, more coordination and collaboration between IRCC, ISED and GAC is necessary to maximize the success of the pilot.

3.2.1. Within IRCC

The evaluation found that mechanisms were in place at all levels within IRCC to support the coordination and communication for the pilot. All IRCC key informants felt that there was effective communication and coordination between Immigration Branch, IPG and CPC-O. All IRCC partners communicate regularly when they receive questions from designated entities / industry associations or from SUV applicants.

3.2.2. Between IRCC and Partners

Between IRCC, ISED, and GAC: IRCC and ISED interviewees felt that the communication and coordination between both departments is effective, while ad hoc in nature. It was noted by IRCC interviewees that outreach and engagement with GAC has been lacking from a SUV promotion perspective. Some ad hoc engagement has occurred with trade commissioners in various Canadian missions abroad. It was noted that there was a lack of a coordinated effort regarding the promotion of SUV from a trade perspective, abroad.

Interviewees from IRCC and ISED noted a need for more engagement and interdepartmental outreach between IRCC, ISED and GAC related to the SUV pilot. It was suggested that all relevant departments need to take a whole-of-government approach to the SUV program.

Between IRCC and industry associations: Overall, all IRCC key informants felt that there was a good working relationship with industry associations, although it was noted that the communication was mostly ad hoc from a program delivery perspective. IRCC communicates to designated entities through industry associations. There is varying levels of communication from industry associations depending on their level of capacity (all are non-profit). IRCC relies on industry associations’ expertise regarding designated entity behaviour and the peer review process.

Between IRCC and designated entities: Most communication from Immigration Branch to designated entities is funnelled through industry associations. IRCC has minimal direct communication with designated entities related to overall policy or operational changes; this is channeled through industry associations. IPG deals with SUV applicants and designated entities through an operational email box dedicated to the SUV pilot. Overall, no major issues were noted about the communication between IRCC and designated entities. Many designated entities and SUV applicants felt that they received good support from IRCC throughout the immigration process. Some IRCC and designated entity key informants felt that more direct, formal and regular communication with all designated entities, instead of through industry associations or bilaterally with a few designated entities, would be beneficial.

Between designated entities and industry associations: Overall, many designated entities felt that communication and coordination from industry associations was minimal. Designated entities noted that more information and support could be provided by industry associations.

4. Findings – Performance

4.1. Operational and Socio-Demographic Profile

Finding: While the pilot received fewer applications and admitted fewer foreign entrepreneurs than the previous entrepreneur program, the evaluation found that SUV immigrants brought more human capital to Canada in terms of age, education, and knowledge of official language compared to immigrants under the previous program.

4.1.1. Number of SUV Applicants

In the first three years of the pilot (April 2013-April 2016), IRCC received 113 applications for permanent residency under the SUV pilot. As seen in Table 4.1, the number of applications increased each year. In total, this represents 113 principal applicants and 285 applicants including spouses and dependants since the launch of the pilot.

| 2013 (Apr. – Dec.) |

2014 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2015 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2016 (Jan. – Apr) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of SUV Principal Applicants | 2 | 32 | 61 | 18 | 113 |

| Number of SUV Principal Applicants + spouses and dependants | 3 | 76 | 160 | 46 | 285 |

4.1.2. Number of Admitted SUV Immigrants

As observed in Table 4.2, the number of principal applicant admissions increased from 0 in 2013 to 26 in 2015, with signs of a similar increase for 2016. In total, this represents 47 principal applicants and 107 including spouses and dependants since the launch of the pilot. These admitted principal applicants represent 32 businesses in Canada.

Compared to the previous EN program, which admitted on average approximately 313 principal applicants to Canada per year between 2007 and 2011, the SUV pilot has admitted fewer immigrants to date. As such, many key informants stated that the number of foreign entrepreneurs admitted under the SUV pilot was lower than anticipated. However, the SUV pilot targets a different calibre of entrepreneur than the previous EN program. While key informants felt that the program could be bringing in more entrepreneurs than it is currently, it was also recognized that the pilot should not be considered high volumeFootnote 13 and instead should focus on the quality of the entrepreneur and their business idea.

| 2013 (Apr. – Dec.) |

2014 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2015 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2016 (Jan. – Apr) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of admitted SUV immigrants | 0 | 4 | 26 | 17 | 47 |

| Number of admitted SUV immigrants + spouses and dependants | 0 | 9 | 62 | 36 | 107 |

4.1.3. Number of SUV Principal Applicants Approved and Refused

Between April 2013 and April 2016, the majority of principal applicants who obtained a commitment certificate from a designated entity applied to IRCC and received a decision under the SUV pilot were approved. As observed in Table 4.3, below, 80% of all principal applicants were approved and 20% were refused.

| 2013 (Apr. – Dec.) |

2014 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2015 (Jan. – Dec.) |

2016 (Jan. – Apr) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved | 2 | 23 | 26 | 0 | 51 (80%) |

| Refused | 0 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 13 (20%) |

| Pending DecisionTable note ** | 0 | 2 | 29 | 18 | 49 |

| Total Received | 2 | 32 | 61 | 18 | 113 |

4.1.4. SUV Immigrant Characteristics

Table 4.4 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of SUV entrepreneurs arriving in Canada from April 2013 to April 2016. A comparison of entrepreneurs admitted under previous EN program is also provided.

Administrative data indicate that SUV immigrants tend to be younger, between 25 and 44 years of age at admission (77%). In addition, SUV entrepreneurs have more post-secondary education (74%) and report having a greater knowledge of English or French at the time of admission compared to the previous EN program. Also, more SUV immigrants intended to settle in an Atlantic province (27%) than the previous EN program.

Although the previous program required applicants to have business experience and the SUV pilot does not explicitly have criteria,Footnote 14 many admitted SUV immigrantsFootnote 15 (90%) who were interviewed had previous business experience before coming to Canada, either by operating their own business or working for a business in a managerial or senior role.

| Age | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 4% | 0.1% |

| 25-44 | 77% | 35% |

| 45-64 | 19% | 63% |

| 65+ | 0% | 2% |

| Gender | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 89% | 86% |

| Female | 11% | 14% |

| Education Level | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Bachelor’s degree | 47% | 26% |

| Master’s degree | 21% | 6% |

| Doctorate | 6% | 2% |

| Non-university diploma / secondary or less | 26% | 66% |

| Country / region of birth (top 10) | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| India | 28% | 8% |

| China | 13% | 20% |

| Iran | 9% | 18% |

| UK | 11% | 3% |

| Korea | Table note *** | 7% |

| Romania | 6% | Table note *** |

| Pakistan | Table note *** | 5% |

| USSR | 6% | Table note *** |

| Australia | 4% | Table note *** |

| United Arab Emirates | Table note *** | 4% |

| Costa Rica | 4% | Table note *** |

| Egypt | 4% | Table note *** |

| United States | Table note *** | 4% |

| Kuwait | Table note *** | 3% |

| Ukraine | 4% | Table note *** |

| Hong Kong | Table note *** | 3% |

| Other | 11% | 25% |

| Knowledge of official language | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| English | 96% | 65% |

| Bilingual | 4% | 3% |

| French | 0 | 0.3% |

| Neither | 0 | 32% |

| Marital Status | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Married/Common Law | 64% | 92% |

| Single | 36% | 8% |

| Intended province of destination | SUV pilot (2013 – Apr. 2016) (n=47) |

Entrepreneur Program (EN) (2007-2011) |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 49% | 60% |

| British Columbia | 23% | 33% |

| Alberta | 4% | 5% |

| Atlantic | 23% | 1.4% |

| Other | 0 | 0.6% |

The evaluation assessed SUV applicants’ language ability based on the CLB level obtained as part of the application process (Table 4.5). All applicants obtained at least intermediate CLB levels across all language elements.Footnote 16 Of which, 23% obtained advanced CLB levels in reading; 26% in listening; 19% in speaking; and 9% in writing.

| Listening | Speaking | Reading | Writing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic CLB 1 - 4 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Intermediate CLB 5 - 8 | 74% | 81% | 77% | 91% |

| Advanced CLB 9 - 12 | 26% | 19% | 23% | 9% |

4.2. Facilitating the Access of Entrepreneurs to Canada

Finding: The SUV pilot successfully facilitated the access to Canada for innovative entrepreneurs who have secured business commitments with designated entities. Timely processing and the availability of the work permit were noted as key elements that have contributed to the success of the pilot.

The majority of key informants across all groups felt that the SUV pilot facilitated the access of innovative entrepreneurs to Canada. It was noted that the small size of the SUV pilot enabled IRCC to provide responsive service to designated entities and applicants. Expedited processing times and the availability of a work permit were two major components deemed important to SUV entrepreneurs and contributed to the success of the pilot.

Many admitted entrepreneurs also stated that a main reason to establish a business in Canada was the fact that the pilot was more facilitative compared to other countries’ entrepreneur immigration programs. In particular, the American immigration system was viewed by key informants as difficult to navigate whereas the Canadian system was seen as an alternative means to break into the North American market. SUV entrepreneurs also frequently mentioned the social and environmental benefits of Canada (social services, cultural sensitivity, safe environment, etc.) as significant pull factors.

4.2.1. Processing Times

The majority of designated entities and admitted SUV immigrants were very positive about IRCC’s support through the immigration process and felt that processing times were reasonably fast. The importance of timely processing for this client group was frequently highlighted by key informants, with the majority stating that the success of a business (especially those in mobile technology) often depends on how fast it can be launched.

SUV applications were processed by IRCC in a timely manner: on average, 80% within 158 days (5.3 months) on average across 2013 to 2015.Footnote 17 Compared to the previous entrepreneur program, SUV applications are being processed in approximately one-tenth of the time. According to departmental data, the processing time for 80% of previous entrepreneur program applications ranged from 69 to 81 months between 2007 and 2011.

| Year of application | Days (average) | Months (average) |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 201 | 6.7 |

| 2014 | 216 | 7 |

| 2015 | 124 | 4.1 |

| Total Average | 158 | 5.3 |

4.2.2. Work Permits

Between April 2013 and April 2016, the majority of SUV principal applicants (80% or 38 of 47) who were admitted to Canada obtained work permitsFootnote 18 prior to obtaining permanent residency. The vast majority of key informants, across all interview groups, strongly supported the work permit optionFootnote 19 as part of the SUV pilot. They suggested that work permits allow entrepreneurs to start their business faster, which is generally a requirement by designated entities. Without the work permit, key informants noted that businesses had a higher risk of failure as there is often a short window for business growth once the concept has been established. While a work permit assists the entrepreneur to start the business quickly, timely attainment of permanent residency affords entrepreneurs with greater credibility in the eyes of investors, as it can show investors they are serious about operating a business in Canada.

4.2.3. Selection Criteria

Overall, most key informants felt that the selection criteria under the SUV pilot were appropriate and relevant. In particular, many designated entities and admitted SUV immigrants felt that the language requirement was particularly important due to the necessity to conduct business in one of Canada’s official languages. It was noted by a few designated entities that the language requirement was problematic in a very few of instances where applicants did not have the minimum language ability and therefore were not eligible. Designated entities were supportive of the removal of the education requirement in 2014 as they noted that this requirement may not have a direct correlation with business success.

4.3. Initial Performance of SUV Entrepreneurs

Finding: Admitted SUV entrepreneurs are actively pursuing innovative business ventures in Canada. To date, positive progress was made by SUV entrepreneurs in either business growth, obtaining additional investment, increasing networks and business connections, or selling their business for a profit.

Overall, all SUV entrepreneur key informants stated that they were actively pursuing business ventures in Canada at the time of the interview. The vast majority were pursuing the same business venture that they committed to with their designated entity. Those that were not pursuing the same business venture reported to have changed direction or adjusted their business idea (pivoted) to better suit the needs of the market, or have sold their business due to early success and have launched other ventures.

4.3.1. Business Success

When asked to assess their current business success, many SUV key informants reported that there was positive progress in either obtaining additional investment, increasing their networks and business connections, generating revenue, hiring Canadian employees or selling their businesses for a profit. Designated entities corroborated this view, by stating that most of the businesses they have incubated or invested in through the SUV pilot have demonstrated early success.

4.3.2. Type of Business

An expected outcome of the SUV pilot was to attract innovative entrepreneurs to contribute to the innovation needs of the Canadian economy. To assess this outcome, the evaluation examined the business description included in the commitment certificates to determine what industry sector and business activity are associated with each business. The evaluation also examined the information provided by admitted SUV entrepreneur key informants. From this information, the evaluation assessed whether the proposed businesses broadly fit the definition of “innovation”.Footnote 20

The evaluation found that the majority of proposed businesses and businesses started in Canada to date fit the broad definition of innovation. As seen in Table 4.7, the majority of applicants who submitted commitment certificates proposed businesses activities related to software development / sales (74%), followed by product manufacturing / sales (non-software related) (24%). Overall, the majority of proposed businesses could be classified in the following industry sectors: business technology, education, consumer products, finance, energy / clean technology, real estate, tourism, medical health, and arts. Similarly, interview information from admitted SUV immigrants corroborated that the majority of businesses started were related to software development (in education, finance, and social media) as well as other technology.

| Core Business Activity | SUV entrepreneurs # |

SUV entrepreneurs % |

Industry Sector(s) Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software development / sales | 59 | 74% | Education, medical, finance, real estate, social media, etc. |

| Product manufacturing / sales (non-software related) | 19 | 24% | Food/drink, medical devices, consumer products, environment, energy technology, etc. |

| Service – Other | 2 | 2% | Construction and business service. |

4.4. Designated Entity Activity

When the pilot was launched in 2013, 28 entities were designated by the Minister of IRCC, which included 25 venture capital funds and three angel investor groups. As of April 2016, this has grown to 52 designated entities, including 32 venture capital funds, six angel investor groups and 14 business incubators.

The evaluation found that the majority of designated entities had not submitted a commitment certificate (58%). As of April 2016, 22 of the 52 (42%) designated entities have submitted at least one commitment certificate during the period of the evaluation. Key informants felt that this level of activity was not necessarily negative, suggesting that the pilot is used differently by various designated entities. For example, some designated entities viewed SUV as a tool to supplement their other investments (with Canadians), only engaging foreign entrepreneurs when a quality proposal is referred to them through an industry contact or network. Only a few designated entities actively review all unsolicited proposals and seek foreign entrepreneurs overseas.

Finding: In total to date, SUV pilot entrepreneurs received over $3.7M in investment capital from designated entities.

4.4.1. Investment Activity

The evaluation also assessed the extent to which designated entities had invested capital into SUV businesses. As previously noted, venture capital fund designated entities are required to invest a minimum of $200,000 in the entrepreneur’s business. Angel investor group designated entities have a minimum investment of $75,000. There is no minimum investment amount for business incubators, but the entrepreneur must be accepted into the business incubation program.

An examination of the commitment certificates submitted to IRCC from April 2013 to April 2016 indicates that 36 businesses (of 80) received investment capital from designated entities, representing over $3.7M.

In addition to the minimum investment amount required by angel investors and venture capital funds, five business incubators made 24 investments during this time period for a total of $1.7M. See Table 4.8 for more information.

| Designated Entity Group | # of businesses indicating investments | Investment amount range | # of designated entities that contributed to the investments | Investment total ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Incubators | 24 (of 68 commitment certificates) | $10,000 - $300,000 | Five business incubators contributed to the 24 noted investments. | $1.7M |

| Venture Capital Funds | 9 | 200000 | Four venture capital funds contributed to the nine noted investments. | $1.8M |

| Angel Investors | 3 | 75000 | One angel contributed to the three noted investments. | $225K |

| Grand Total | 36 | $10,000 - 300,000 | 10 | $3.725M |

Business incubators follow differing business models; all provide services to entrepreneurs (such as mentorship, office space, access to networks of investors) to help them grow their business but in return, some invest and take an equity stake in these businesses while others charge business incubation fees instead. Some industry associations and designated entities felt that the business incubation stream was subject to potential abuse due to the lack of a required minimum investment. It was suggested that without this requirement, certain business incubators may have alternative motivations regarding the pilot (e.g. incentive to accept many foreign entrepreneurs in order collect rent for office space and fees for business incubation services). However, it was noted by a few interviewees that business incubators who do not take an equity stake should be considered legitimate if operating appropriately and according to the intent of the pilot.

4.4.2. Method of Contact

Out of all the commitment certificates reviewed during the evaluation time period (80), at least 37% (30/80) indicated that designated entities came into contact with foreign entrepreneurs through business networks or business engagements (e.g., conference and events, etc.); 43% (34/80) indicated that designated entities came into contact with foreign entrepreneurs online through unsolicited proposals and 20% were unspecified.

4.4.3. Designated Entity Support

Finding: While the support provided by designated entities was generally viewed as positive, some key informants noted a lack of transparency and delivery of agreed-upon support by some business incubators.

SUV key informants noted that they received a range of support from designated entities, which include: mentoring, office space, financial investment, administrative support and networking. Overall, the majority of admitted SUV key informants did not raise many concerns and were generally positive about the support received from their designated entity. However, some informants, from the business incubation stream, raised concerns about how forthcoming/ transparent designated entities were regarding business term sheets/client agreements and the services/terms they were committing to. It was noted by a few key informants that they received a business term sheet after the commitment certificate was sent to IRCC, or late in the process. It was also noted by some key informants that they did not have a complete understanding of the process before signing the commitment with the business incubator. Furthermore, some key informants noted that the support provided by certain business incubators was lacking or less than originally agreed. For example, some admitted SUV entrepreneurs felt that the quality and frequency of the mentoring they received was lacking and not reflective of their agreement.

4.5. Program Integrity

Finding: There were minimal levels of fraud and misuse associated with the SUV pilot and the integrity mechanisms employed were successful in identifying issues. However, there is a potential program integrity gap regarding the monitoring of designated entities’ SUV activities.

Many IRCC key informants felt that the SUV pilot was successful in identifying issues related to fraud and program misuse. Because the pilot was small in size, IRCC was able to monitor stakeholder and applicants’ activities closely. It was also noted that the peer review process was a useful tool to check whether the business commitment was legitimate and whether due diligence was completed. While it was generally felt that there were low levels of fraud, some key informants mentioned that there was some potential for misuse. For example, some suggested that certain family members included in the core business team may not actually be part of the business, but were included in order to gain entry to Canada.

The evaluation found no significant gaps in IRCC’s ability to identify fraud from an application perspective. However, some key informants noted a potential program integrity vulnerability in the pilot, suggesting that IRCC has no formal mechanism to regularly review designated entities’ practices regarding the SUV pilot in order to introduce consequences if fraud or misuse were detected (e.g., suspension or de-designation).

4.6. Resource Utilization

Finding: The cost to administer the SUV pilot was less than the previous entrepreneur program. The design of the Pilot, which requires designated entities to select innovative foreign entrepreneurs instead of IRCC visa officers, was advantageous from a cost-efficiency perspective.

According to an analysis of departmental financial information, the total IRCC cost of the pilot was approximately $644,000 on average per year ($441,456 in 2013/14 and $846,426 in 2014/15). While not directly comparable,Footnote 21 the previous entrepreneur program was estimated to cost approximately $5.2MFootnote 22 on average per year between 2006/07 and 2011/12.

Many key informants noted that one of the main advantages of the SUV pilot was its low cost and resource requirement (on average between two and five FTEs per year). Unlike the previous program where visa officers assessed business proposals, the current pilot leverages the experience and expertise of designated entities to select innovative foreign entrepreneurs, which represents a major shift in the department’s approach to processing entrepreneurs. Key informants felt the benefit of this approach was that designated entities were better placed to select innovative foreign entrepreneurs with viable businesses than visa officers.

4.7. Alternative Approaches

The majority of key informants were not able to identify an alternative approach that would better address the need for innovative entrepreneurs in Canada than the SUV program. The SUV pilot is considered a good replacement of the old entrepreneur program and that government officials reviewing business proposals based on the previous program criteria was not the most effective approach.

5. Findings - Relevance

5.1. Need for the Pilot

Finding: There is a need for an entrepreneur immigration program like the SUV pilot to attract and retain innovative entrepreneurs that contribute to the innovation needs of the Canadian economy.

The evaluation of the department’s Business Immigration Programs, published in June 2014, noted that there was a need for Canada to have an entrepreneur program in order to contribute to the Canadian economy. The previous Entrepreneur Program, however, was determined to no longer be meeting the current needs of the Canadian economy and stopped accepting applications in 2011 and was cancelled in 2014.

The majority of key informants felt that there was a strong need to have a program like SUV to attract and retain innovative immigrants and start-ups. Most key informants across all groups felt that if the pilot did not exist, Canada would be missing out on economic innovation opportunities and entrepreneurial talent. Some key informants noted that other countries are trying to cultivate similar programs and that Canada’s program was viewed as very progressive and innovative. They noted that it was important for Canada to leverage the fact that other similar countries are not yet implementing similar programs to attract these individuals. Lastly, it was suggested by interviewees that the SUV pilot has helped turn Canada into a destination of choice for foreign entrepreneurs. Most interviewees stressed the need for Canada to take advantage of attracting entrepreneurs in an area where there is increased competition from other countries.

While some key informants felt that the pilot is currently not fulfilling the need because of the low number of successful applicants, many other key informants felt that the relatively low number was not an issue because the program was meant to be small and focus on attracting high value entrepreneurs. It was felt that the value in the program should not be viewed the number of entrepreneurs admitted to Canada, but the quality of the entrepreneur and the potential future success of a handful of businesses. In general, most key informants were positive about the pilot but noted that it is too early to measure its long-term success.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

IRCC implemented an innovative, low-cost program that has the potential to bring high-value entrepreneurs to Canada to start innovative businesses that contribute to the innovation needs of the Canadian economy.

Performance – Human Capital and Initial Success

The SUV pilot was implemented to replace the previous entrepreneur program that was no longer meeting its objectives. Compared to the previous program, early evidence suggests that the SUV pilot is meeting its objectives by admitting innovative entrepreneurs with greater human capital, who are actively pursuing innovative businesses in Canada. The evaluation also found that SUV entrepreneurs are demonstrating early success in terms of their ability to grow a business in Canada. While there were mixed views on the low number of SUV applications compared to the previous program, it was felt that, while the number of applications will likely increase over time, the pilot was never intended to be a mass immigration program.

Performance – Facilitation

The initial success of the pilot is, in part, due to its design. Unlike the previous program where visa officers assessed business proposals, the current pilot leverages the experience of designated entities to select innovative foreign entrepreneurs. The success of the pilot can also be attributed to IRCC’s efforts to facilitate the access of foreign entrepreneurs to Canada. The evaluation found that the SUV pilot was very facilitative to applicants, processing applications within 5.3 months on average and providing them the option to obtain a work permit to start the business before obtaining permanent residency.

Design and Implementation

While the pilot was implemented as planned with low levels of reported program misuse, the evaluation found there were a number of implementation and design challenges that need to be addressed if the pilot were to become a Program.

In particular, the evaluation found the business incubator stream encountered a number of challenges related to the peer review process, the reliance on industry associations to communicate with and to designate business entities, lack of a clear IRCC mechanism to de-designate a designated entity, and lack of transparency and delivery of agreed-upon support by some business incubators to the SUV entrepreneurs. The requirement to conduct a peer review for 100% of applicants was felt to be too resource intensive. Key informants noted a lack of clarity around peer review criteria as well as the lack of ability for the applicant to provide additional information to the visa officer.

Recommendation 1: IRCC should implement measures to ensure that:

- The peer review process is risk-based, transparent and procedurally fair;

- IRCC has a clear mechanism for the de-designation of entities and implements a regular review process to ensure designated entities continue to qualify for designation; and

- Necessary program integrity measures related to industry associations and designated entities are in place.

Promotion and engagement

Current promotional activities (i.e. promoting the program broadly/generally), while reaching a wider audience, was also felt to attract large numbers of low-quality unsolicited proposals. Instead, many designated entities and IRCC key informants felt that targeted promotion (e.g., to educational institutions, start-up communities / organizations, and business connections through trade delegates overseas) would result in better proposals and would increase the program’s success.

The evaluation found that outreach and engagement between IRCC, ISED and GAC was lacking from a SUV promotion perspective. Key informants from IRCC, ISED and designated entities noted that a whole-of-government approach in attracting innovative entrepreneurs does not currently exist, suggesting that the program would be stronger if relevant stakeholders work together to develop strategic ways to attract innovative talent to Canada.

Recommendation 2: IRCC should revise its current engagement approach with other relevant departments and stakeholders and develop a targeted SUV promotion strategy.

Awareness of the pilot

There was a lack of awareness by IRCC/CBSA frontline staff regarding SUV pilot, in particular, regarding the issuance of work permits, which some applicants found difficult to obtain.

Recommendation 3: IRCC should develop and implement a plan to increase awareness of the pilot and the related work permit requirements among frontline staff.

Data availability and consistency

In the course of the evaluation, there were challenges in the measurement of certain SUV data elements as a result of the unavailability of data in IRCC systems. Administrative data related to SUV businesses was not consistently captured or linked to principal applicants in GCMS. Furthermore, information contained in commitment certificates was not consistently entered in each form by designated entities and therefore did not allow for a complete assessment of data elements contained within.

Recommendation 4: IRCC should develop a strategy that enables the consistent collection and reporting of pilot performance.

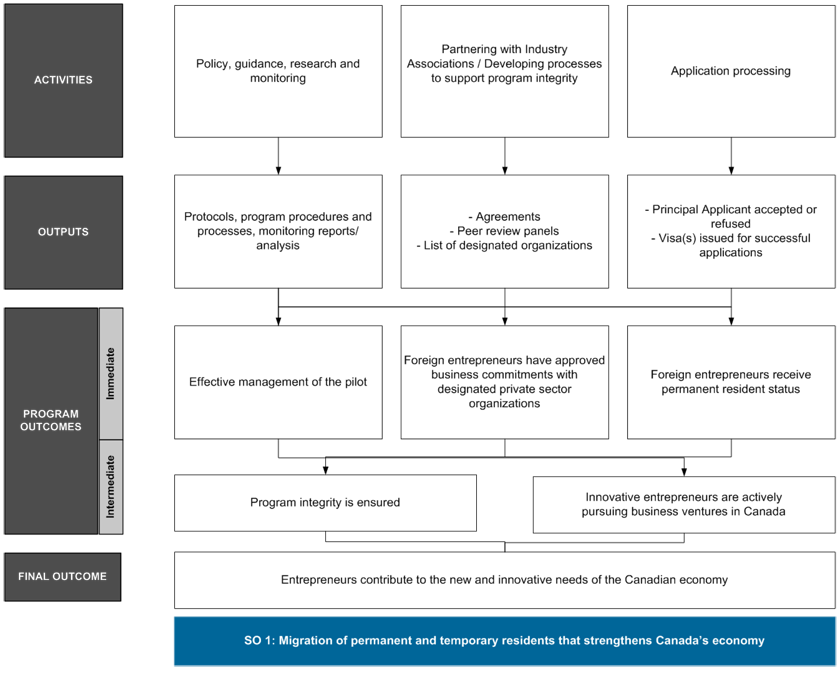

Appendix A: Logic Model for the Start-Up Visa Pilot

Appendix A illustrates the logic model for the Start-Up Visa Pilot at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, which serves as a visual representation of the activities, outputs and intended outcomes of the Pilot.

Program Activities:

There are three main program activities expected to lead to outputs for the Start-Up Visa Pilot.

- Program Activity 1) Policy, guidance, research and monitoring

- Program Activity 2) Partnering with Industry Associations/Developing processes to support program integrity

- Program Activity 3) Application Processing

Program Outputs

These program sub-activities are expected to lead to the following program outputs.

- Output 1) Protocols, program procedures and processes, monitoring reports/analysis

- Output 2) Agreements, peer review panels, list of designated organizations

- Output 3) Principal applicant accepted or refused, Visa(s) issued for successful applications

Immediate Outcomes

These activities and outputs are expected to lead to a number of immediate outcomes.

Program outputs 1, 2, and 3 lead to the following immediate outcomes:

- Immediate Outcome 1: Effective management of the pilot

- Immediate Outcome 2: Foreign entrepreneurs have approved business commitments with designated private sector organizations

- Immediate Outcomes 3: Foreign entrepreneurs receive permanent resident status

Intermediate Outcomes

These immediate outcomes are expected to lead to the following Intermediate Outcomes.

- Intermediate Outcome 1: Program integrity is ensured

- Intermediate Outcome 2: Innovative entrepreneurs are actively pursuing business ventures in Canada

Ultimate Outcomes

Together, these immediate and intermediate program outcomes lead to a Final Outcome:

- Entrepreneurs contribute to the new and innovative needs of the Canadian economy.

This final outcome feeds into the following strategic outcomes:

- Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy

Page details

- Date modified: