The labour market within Francophone minority communities: Comparative experiences of the international student population and the Canadian-born student population

By Mariève Forest, Guillaume Deschênes-Thériault from Sociopol.

Associated research team: Halimatou Ba, Université de Saint-Boniface; Judith Patouma, Université Sainte-Anne; Christophe Traisnel, Université de Moncton; Luisa Veronis, University of Ottawa

July 18, 2025

This project was funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Summary

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Literature review

- International student population: a way to stimulate the economy and increase immigration

- International student population: a shared priority to support Francophone immigration

- International student population in a Francophone minority setting

- International student population: economic integration

- Francophone immigrant population: economic integration

- Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Gaps between needs and services offered for the school-to-work transition

- Profile of student graduate populations who participated in the survey

- Job search during and after studies

- Use of the Internet

- Canadian cultural codes

- Opening up employers to ethnocultural diversity

- English proficiency

- Networking

- Canadian experience and recognition of prior learning

- Specific aspects of searching for internships

- Temporary resident status

- Distance and accessibility

- Range of services offered by postsecondary institutions

- Employment assistance services provided by the community

- Labour shortage

- Portrait of economic integration

- Reception at a new job

- Working conditions

- Treatment in the workplace

- Impact of the pandemic on the professional situation

- Transition to permanent residency

- Economic and social integration within a Francophone community

- Analysis and conclusion

- Recommendations

- Bibliography

- Appendix I – Supplementary Table

- Appendix II – Research Participation Consent Form

- Appendix III – Interview guides

Acronyms

- CBSP

- Canadian-born student population

- CCNB

- Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick

- CLC

- Collège La Cité

- CSJ

- Campus Saint-Jean

- Francophone communities

- Francophone minority communities

- ISP

- International student population

- UM

- Université de Moncton

- UO

- University of Ottawa

- USA

- Université Sainte-Anne

- USB

- Université de Saint-Boniface

Summary

Like elsewhere in Canada (Usher, 2021), an increasing proportion of the student population in Francophone minority postsecondary institutions are international students. Francophone minority communities are interested in this international student population (ISP), particularly because it appears that it can actively contribute to their demographic, economic, social, and cultural vitality. However, the literature notes that this population is disadvantaged when it comes to their economic integration, which could reduce their retention within Francophone communities.

The main objective of this study is therefore to describe, analyze, and compare the school-to-work transition conditions of members of the ISP and the Canadian-born student population (CBSP) who have studied in French between 2015 and 2021 at seven specific Francophone minority postsecondary institutions. More specifically, it aims to identify the success factors for the school-to-work transition of international students during and after their studies, as well as the obstacles that hinder this transition and how the international student population can have more positive experiences in terms of employment integration.

The methodology used for this study includes a literature review, an online survey and interviews with members of the student population, stakeholders, and employers. The student populations targeted by the survey and interviews studied in French and obtained a degree between 2015 and 2022. The postsecondary institutions included in the study are as follows: Université Sainte-Anne, Université de Moncton, Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick, University of Ottawa, Collège La Cité, Université de Saint-Boniface, and Campus Saint-Jean (University of Alberta).

Literature review

The literature on the retention of the ISP highlights the fact that a majority of these individuals show an interest in staying in Canada for a longer term after obtaining a degree. For example, 91% of Francophone ISP members who participated in the DPMR (Díaz Pinsent Mercier Research) study (2020) said that they intended to look for a job in Canada after their studies. The literature also shows that, compared with immigrants trained abroad, members of the ISP have various advantages for successful school-to-work transitions. These advantages include receiving a Canadian degree, acquiring work experience in the country and attaining degrees in higher education at a greater rate. In addition, these individuals face less significant challenges related to the recognition of their diplomas (Lu and Hou, 2017; Traisnel et al., 2016; Skuterud and Chen, 2018).

Obtaining employment that meets the person’s expectations—especially in terms of qualifications, work experience and working conditions—has a significant impact on ISP retention after graduation (Chira, 2011; Traisnel et al., 2020; DPMR, 2020). The crucial importance of access to employment justifies the necessity to examine the factors that limit the ISP’s ability to integrate the labour market within Francophone communities.

The six limiting factors most commonly cited in the literature are:

- The need to be fluent in English to integrate the labour market;

- Absence of well-established networks in communities;

- Acquisition of Canadian work experience;

- Experiences of discrimination;

- Reluctance on the part of some employers to hire individuals born outside Canada;

- Access to information and administrative issues.

Another issue is the ISP’s ineligibility for federally funded settlement services, employment assistance, and language training. There seems to be a persistent gap between the governmental and community intent to promote the sustainable settlement of the ISP and the resources available to properly prepare these individuals to integrate the Canadian labour market after graduating and to face the obstacles to success that were highlighted in the literature (Chira and Belkhodja, 2013; Traisnel et al., 2019; Lowe, 2011; Chira, 2011).

Analysis of results

First, the online survey was used to gather the perspectives of 340 individuals who graduated from one of the targeted institutions. The ISP diploma holders made up just under half of this sample. We then conducted 21 interviews with CBSP graduates and 34 interviews with ISP graduates for a total of 55 interviews. Lastly, we interviewed 13 individuals who were either employers or stakeholders.

In terms of job searching, during their studies and the year following graduation, ISP members spent a longer time actively looking for work compared with CBSP. It is only for the job held during the survey that this gap narrows. Among the essential components of job search success, we noted knowledge of various Canadian cultural codes, English proficiency, good networking, and having Canadian work experience. Access to services offered by postsecondary institutions or in the community is also considered an advantage.

However, despite effective job search strategies, some employers have unfavourable biases towards certain people. Given the current labour shortage, a lack of openness or knowledge on the part of employers towards culturally diverse individuals appears not only to reduce their likelihood of being hired but also to further reduce the likelihood of being hired based on their skills. Conversely, when companies looking for highly skilled individuals develop an organizational culture that values cultural diversity in the workplace, this can be a factor that helps ISP graduates obtain employment that matches their skills.

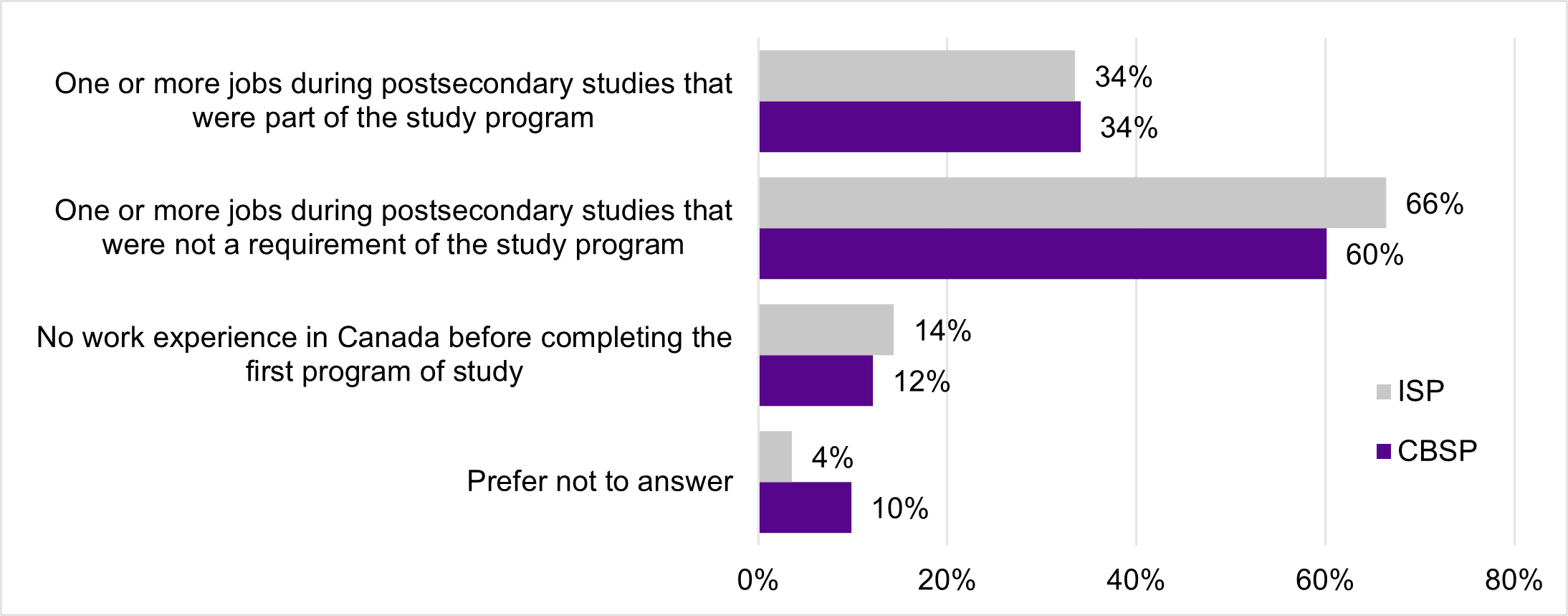

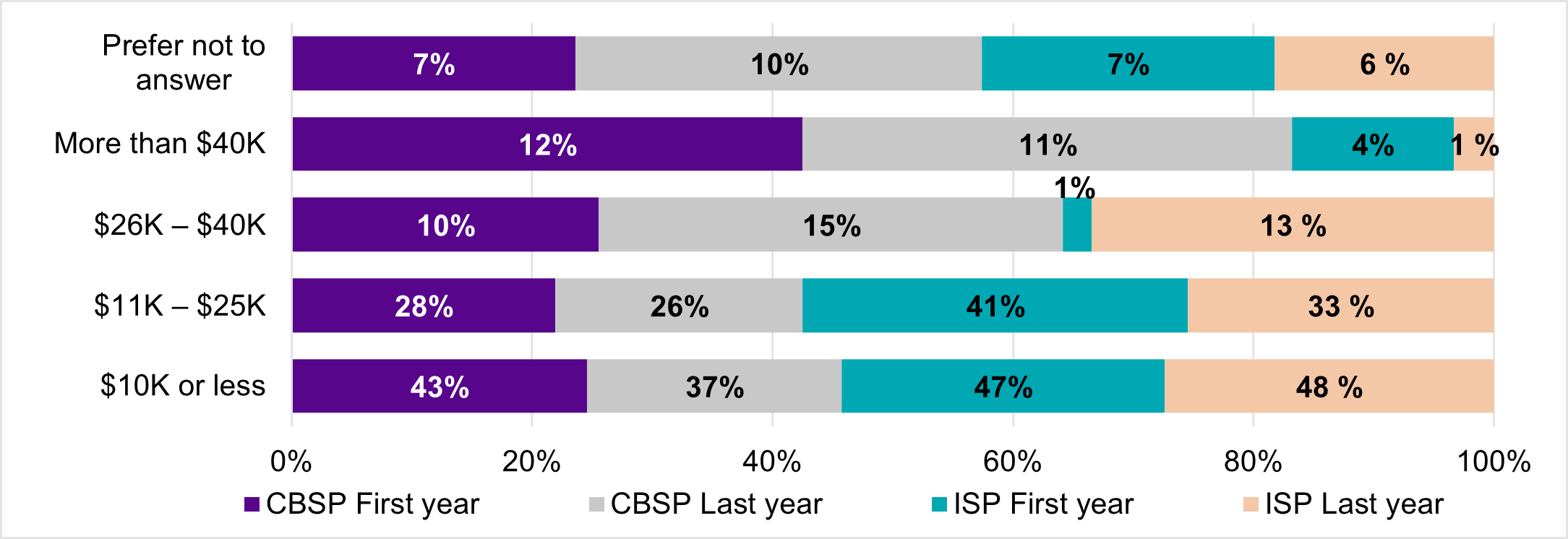

The survey shows that members of the ISP are just as likely to hold employment during their studies as their counterparts born in Canada in the three targeted regions, i.e., Atlantic Canada, Ontario, and Western Canada. However, it is important to mention the differences that exist between these two populations in terms of their occupational status and working conditions.

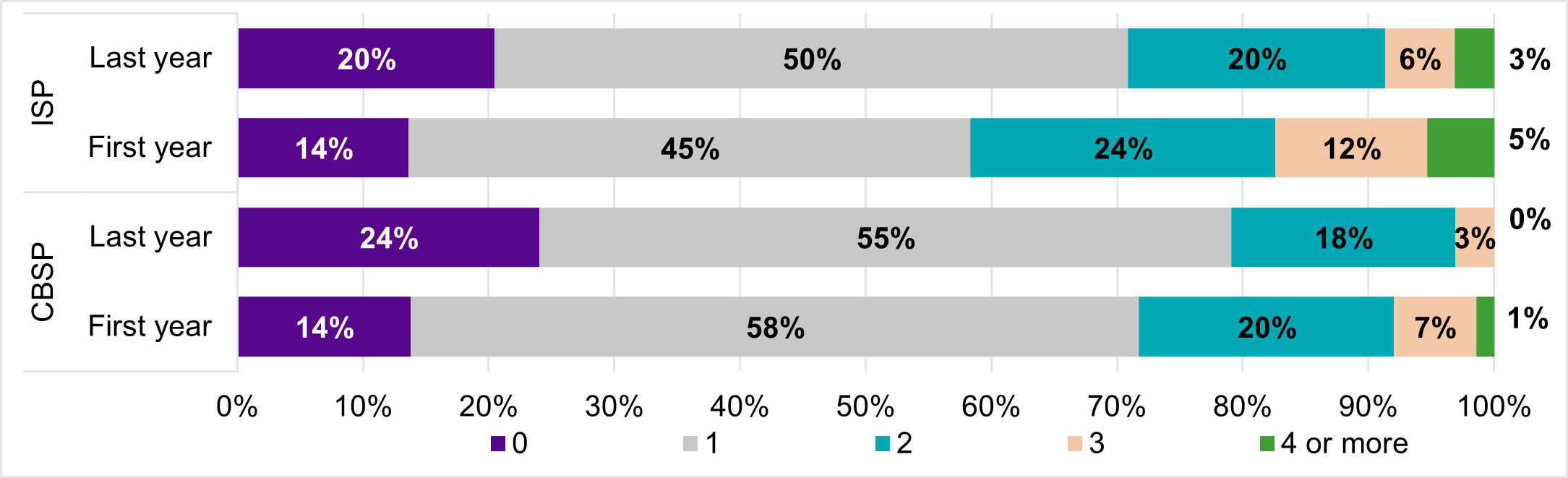

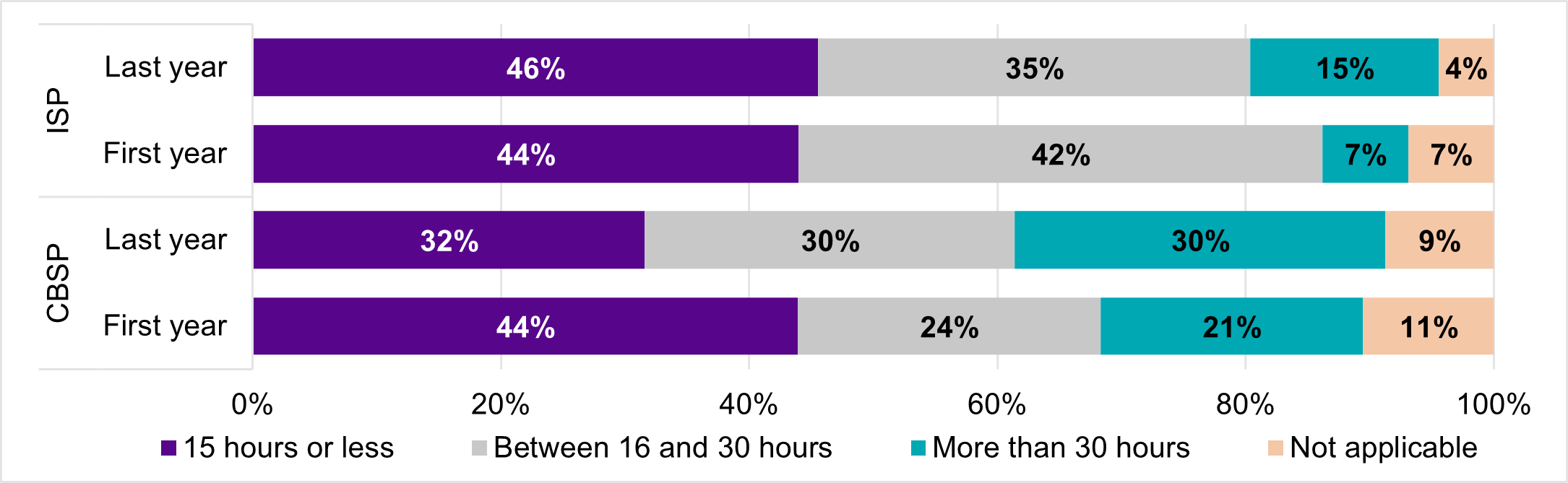

In particular, the ISP:

- Hold a greater number of jobs;

- Work fewer hours per week;

- Have a lower annual income;

- Rate their working conditions more negatively.

Generally, regarding the occupational status and working conditions of ISP members, there are few significant distinctions between the first and last year of studies, except in relation to the following factors:

- A better match between employment and field of study;

- An annual income that is slightly higher, although still lower when compared with individuals born in Canada;

- The explanations put forward by the employer to justify salaries lower than those of their colleagues.

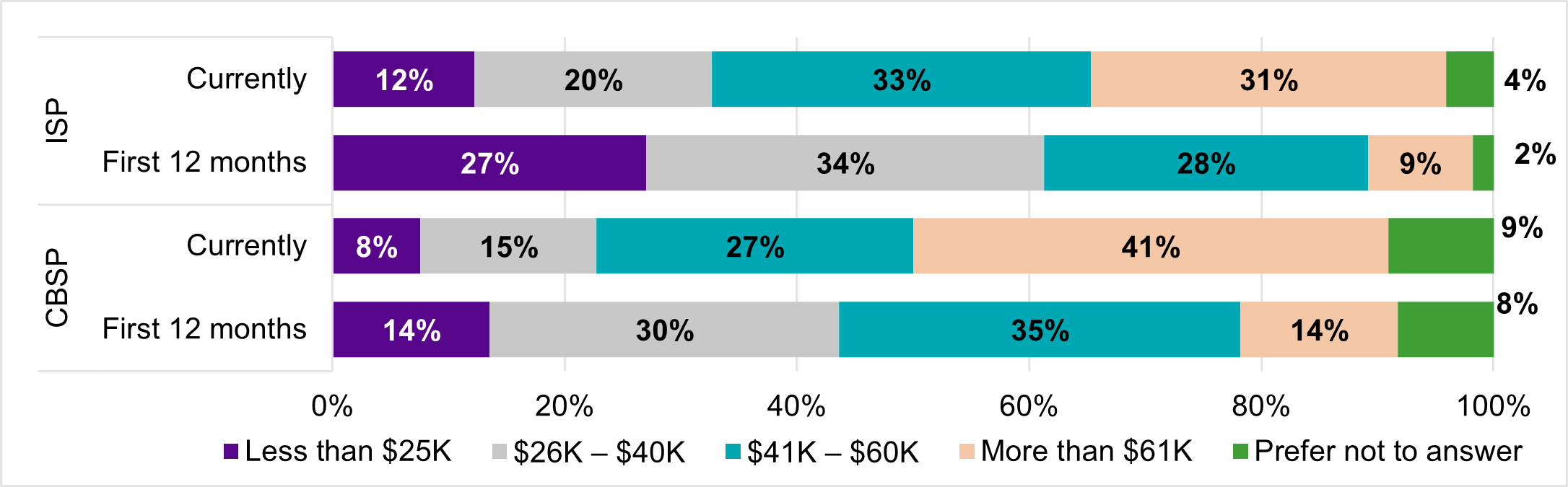

Furthermore, graduates from the ISP are just as likely to work after completing a program of study as those born in Canada. However, in the first twelve months after attaining their degree, compared with graduates from the CBSP, ISP degree holders are more likely to spend a longer period actively searching for employment, have a lower annual income, and have work schedules and benefits that are less satisfactory. These individuals also feel that they are not as well recognized for their work.

More than half of participants (51%), regardless of their status during their studies, were in different jobs at the time of the survey than they were in during the first twelve months after completing their program of study. Generally, the working conditions for the job held by ISP graduates at the time of the interview are better than those related to jobs held in the first few months after graduation and the distinctions between the two populations studied are diminishing. In fact, regarding the most recent job held, members of the CBSP and the ISP are equally likely:

- To make a similar and more positive assessment of their working conditions;

- To consider that they are treated fairly at their jobs;

- To work a comparable number of hours per week;

- To rely on local contacts to find a job;

- To go through a similar period of actively looking for employment;

- To continue to exhibit disparities in annual income.

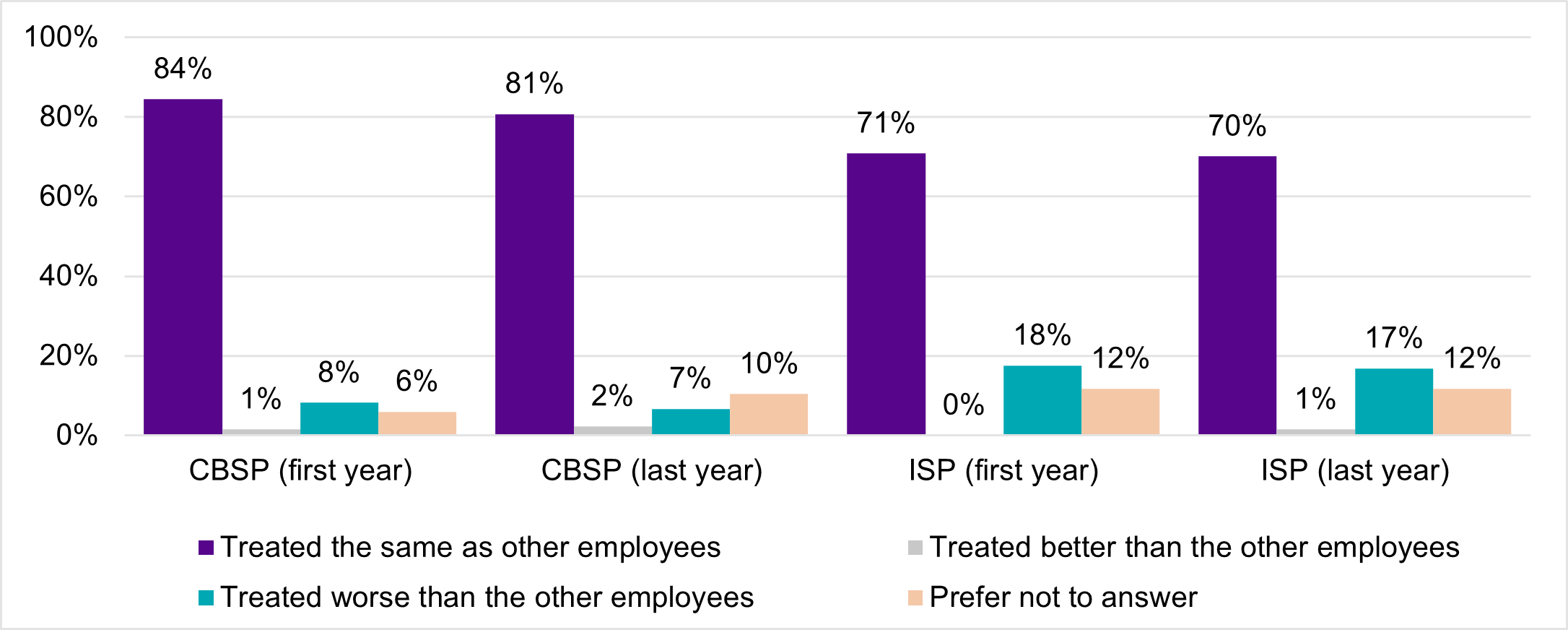

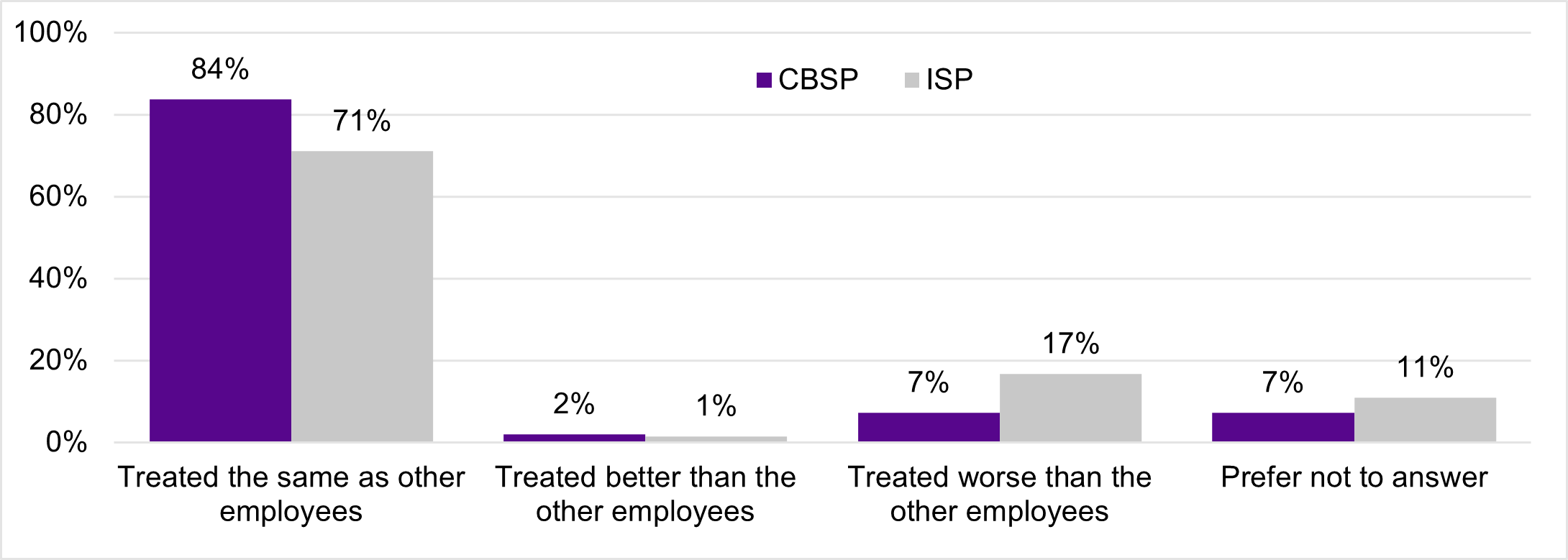

Regarding treatment on the job, nearly one fifth of the surveyed ISP graduates believe that they have been treated worse by their employer than their colleagues in the positions held during and after their studies. People who claimed to have been treated worse than their colleagues were asked to specify why, using a list of about a dozen possible reasons. The only factor that consistently explains poorer treatment in employment at various stages of the ISP's professional careers is belonging to a visible minority. It is worth noting that this issue seems to be resolving regarding the job held during the survey, for which 93% of ISP members consider themselves to be treated the same as other employees.

According to our interviews, the Francophone community is only relatively present in the minds and daily life of those interviewed. For some, their relationship with French is presented as an individual preference. For others, the presence of a Francophone community—its members, institutions and services—greatly contributes to a feeling of security and well-being. However, despite their importance, the opportunities and places that can foster connections between the ISP and the local Francophone community seem limited.

Recommendations

Based on the results of this study, we recommend six initiatives to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada:

- Support postsecondary institutions in adopting a holistic and personalized approach that promotes the economic integration of the international Francophone student population during and after their studies.

- Allow the Francophone ISP to access all IRCC-funded settlement services, including language training and employment services.

- Establish a program with the goal of ensuring the visibility and presence of the Francophone community at Francophone minority postsecondary institutions, particularly among the ISP.

- Create a program with the goal of providing workplace language training to the Francophone ISP and raising employers’ awareness of the specific characteristics and added value of this workforce.

- Relax the rules regarding the study permit and work permit for the ISP, both during and after studies, so that more diverse pathways are possible.

- Ease immigration rules to facilitate the transition of members of the Francophone ISP to permanent residency.

Introduction

Overview

In Canada, the international student population (ISP) has grown significantly since the early 2000s, and this growth has accelerated since 2009 (Usher, 2021). According to Usher, the number of international students has increased from just under 40,000 in the late 1990s to 345,000 in 2018–2019. At the same time, since the early 2000s, the federal government, in collaboration with Francophone minority communities, has been seeking to increase the number of immigrants who settle within these communities (OCOL, 2021). In this context, the ISP seems to be able to actively contribute to the vitality of these communities in terms of demographic, economic, social and cultural aspects.

In fact, this skilled population has been trained in Canada, which reduces the issues related to credential recognition, a significant barrier to successful economic integration. In general, the time spent in Canada during studies increases the opportunities to build networks, acquire Canadian work experience, and experience cultural immersion (Traisnel et al., 2016).

Despite these advantages, research shows that Francophone ISP graduates who are interested in staying in the region where they studied over the longer term are not always able to do so, particularly due to difficulties related to economic integration. While access to employment is one of the main conditions that influence a pathway’s success towards permanent settlement (Díaz Pinsent Mercier Research (DPMR), 2020), research highlights the difficulties associated with finding a job that matches an individual's field of study and skill level (Sall, 2019).

Access to employment is key to promoting retention of the ISP, hence the necessity to examine what factors promote or limit this population’s ability to integrate the labour market in Francophone communities and see how their experiences after graduating differ from those of students born in Canada. This study focuses on these factors and on the school-to-work transition conditions of the Francophone minority ISP. In more concrete terms, it focuses on the following objectives.

General objectives

The main objective of this study is to describe, analyze and compare the school-to-work transition conditions of members of the ISP and CBSP who completed their studies in French between 2015 and 2021 in seven Francophone minority postsecondary institutions. Specifically, it is about determining the success factors for the ISP’s school-to-work transition during and after studies, as well as the obstacles to this transition, while examining how the ISP can have more positive experiences in terms of this transition.

Specific objectives

This research was guided by specific objectives:

- Describe, analyze, and compare hiring experiences and identify obstacles;

- Describe, analyze, and compare employment integration experiences and identify obstacles;

- Explain the differences in terms of economic performance;

- Present community, municipal, and government initiatives, as well as business initiatives, that facilitate the school-to-work transition, particularly for the ISP;

- Describe and analyze the role played by the postsecondary institution and the scope of the initiatives implemented by it in relation to the school-to-work transition;

- Clarify the actions taken and the challenges faced by ISP graduates in both establishing themselves in the labour market and obtaining permanent residence in Canada;

- Explain the experiences and problems faced by employers when hiring and integrating members of the ISP and CBSP who studied in French;

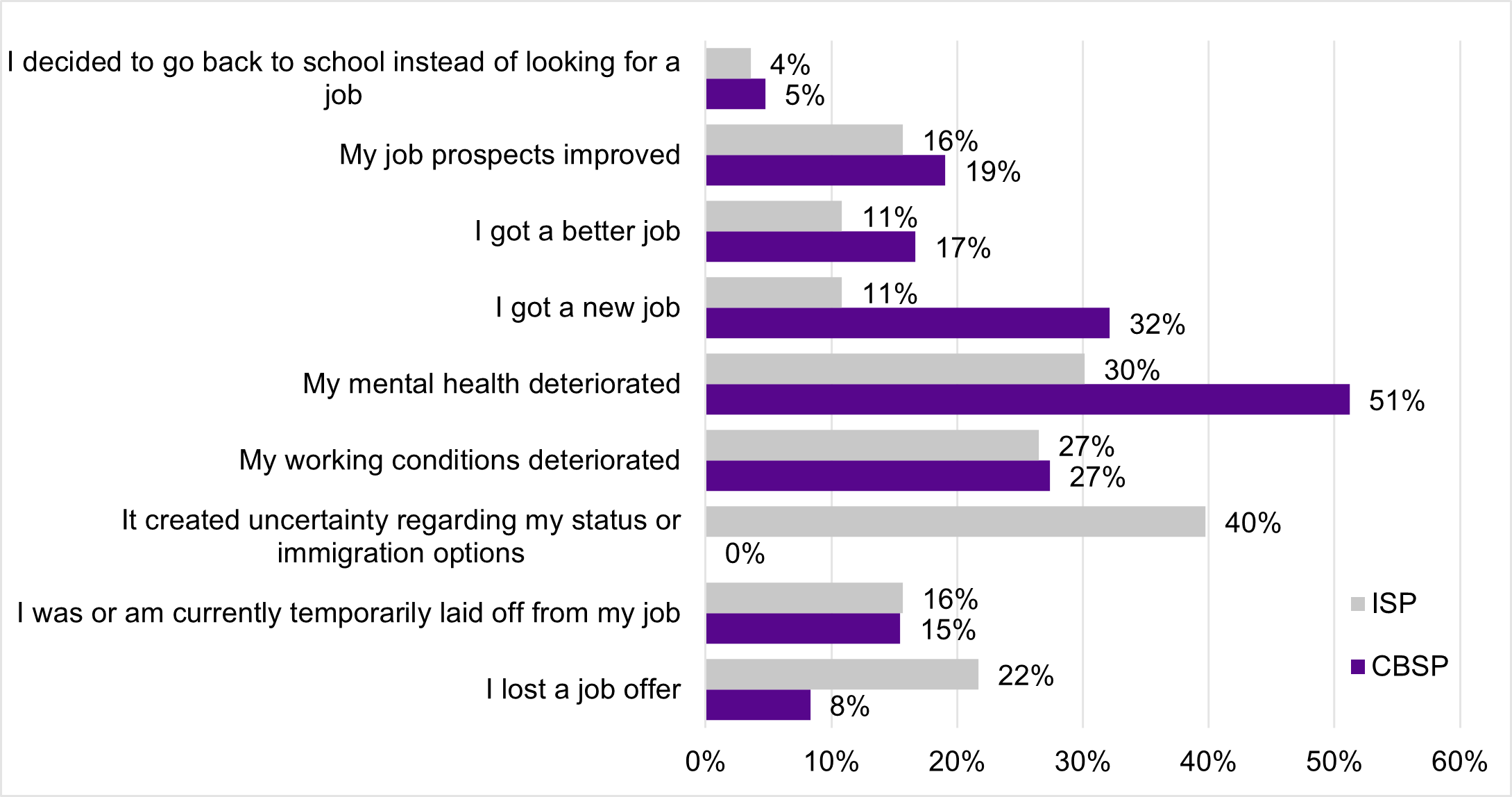

- Describe the perceived effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market experiences of the ISP and CBSP;

- Explore the differentiated relationships with the Francophone community.

Methodology

We adopted a mixed methodology based on various data collection methods carried out at seven predefined postsecondary institutions. This methodology includes a literature review, an online survey, and interviews with the student population, stakeholders and employers.Footnote 1

Selection of establishments

Our study aims primarily to paint a picture of the situation for all of the Francophone communities. However, the different data collection phases allowed us to gain knowledge about various postsecondary institutions and different geographical areas. The choice of specific institutions and regions for the interviews has at least allowed for a comparative perspective between institutions and between Francophone communities. Indeed, based on writings on the vitality of Francophone communities, we believe that the province’s legislative and regulatory framework, the density and size of the community, as well as the institutional completeness of the community can influence the employment integration experience of populations in general and immigrant populations in particular (Langlois and Gilbert, 2006; Belkhodja, Traisnel and Wade, 2012; Esses et al., 2016).

Thus, the online questionnaire and interviews targeted postsecondary institutions that offer French-language training and the respective communities in which they are located. The following Francophone communities and institutions were selected:

- Clare and Halifax: Université Sainte-Anne – Nova Scotia;

- Moncton, Edmundston and Shippagan: Université de Moncton and Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick – New Brunswick;

- Ottawa: University of Ottawa and Collège La Cité – Ontario;

- Saint-Boniface: Université de Saint-Boniface – Manitoba;

- Edmonton: Campus Saint-Jean – Alberta.

Principles that guided the literature review

The literature review was conducted at the beginning of the research so that its findings could be used to develop data collection tools and analytical frameworks. This documentary analysis primarily drew from scientific literature and grey literature from the past 10 years, focusing on the themes of the school-to-work transition of immigrants and the ISP in Francophone communities and in Canada.

Survey

The purpose of the online survey was to understand the economic integration of graduate students aged 18 and older, whether they come from another country or born in Canada. It included 69 closed-ended questions and six open-ended questions. All of the intended participants had studied in French at one of the seven targeted institutions and had graduated between 2015 and 2022. To ensure the quality of the results, pre-tests were conducted before the survey was released. The questions covered five major dimensions:

- Postsecondary degrees obtained in Canada since 2015;

- Occupational status during the first and last year of the postsecondary program;

- Occupational status after completing postsecondary studies;

- Effects of the pandemic on occupational status;

- Demographic profile of participants.

The survey was posted online using the SurveyMonkey platform from June 2022 to October 2022. The invitation to take part in the study was distributed through the graduate associations of the participating institutions, through community partners from the Francophone immigration sector and through IRCC.

Interviews with the graduate population

The purpose of these interviews was to deepen our understanding of the employment transition experiences of ISP and CBSP graduates (see Appendix III for the interview guide). As for the survey, all the individuals invited to participate had studied in French in one of the seven targeted institutions and had graduated between 2015 and 2022. We held semi-structured interviews that took a retrospective, trajectory, and intersectional approach. We aimed for representation in terms of the institution attended, type of degree attained, gender, and field of study. The objective was achieved, as we conducted interviews with a nearly equal number of CBSP graduates (21) and ISP graduates (34), for a total of 55 interviews.

Interviews with stakeholders and employers

These interviews aimed to deepen our understanding of the employment integration experiences of the ISP and CBSP (see Appendix III for interview guides). We wanted to better understand the support available to members of these populations to facilitate their job search and integration into the labour market. We were also looking to highlight promising practices in this regard. In total, 13 individuals were interviewed, and we aimed for a geographical representation of the organizations and companies they represented. At this stage, it was more difficult to recruit employers than other stakeholders. This situation is not unique to this study; it is common in this type of survey (Traisnel and Violette, 2016).

Ethical considerations

This project first received approval from the Université de Moncton’s Comité d’éthique de la recherche avec des êtres humains (Human Subject Research Ethics Board). We have also received approval from the ethics committees of the Université Sainte-Anne, the Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick, the University of Ottawa, Collège La Cité, and the Université de Saint-Boniface. At each stage of the data collection, a consent form (see Appendix II) was provided to the participants to be read and signed. The data processing was carried out with strict respect for confidentiality. The excerpts from the interviews included in this report do not allow for participants to be identified, as they have been anonymized.

Literature review

This literature review examines the specific characteristics of members of the ISP who have pursued postsecondary studies in a minority Francophone context, particularly in terms of their economic integration and the working conditions to which they are often subjected. When possible, comparisons with other populations are outlined.

International student population: a way to stimulate the economy and increase immigration

The Government of Canada's commitment to support the ISP in achieving permanent residency has been realized through the implementation of its International Education Strategy (2014). According to a study led by the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE), in 2021, 60% of ISP members intended to apply for permanent residency in Canada (2022). The same study specifies that members of the ISP consider Canada a preferred destination because it is safe, offers quality training, is an inclusive and tolerant society and provides opportunities to achieve permanent residency and gain professional experience in their field of study.

The presence of an ISP in Canada has positive impacts on society as a whole in several ways (Shu et al., 2020). For example, on the social level, the study commissioned by the Association des collèges et universités de la francophonie canadienne (DPMR, 2020) shows that the presence of the ISP in Canadian universities promotes the development of inclusive communities. In this regard, the study by Traisnel et al. (2019: 4) also highlights that in Francophone communities outside major urban centres, ISP members play a crucial role in the local “multicultural landscape.” In more general terms, the ISP is of interest to remote regions because it has the potential to contribute to their growth and prosperity (Esses et al., 2018).

Beyond the benefits that the ISP represents in terms of immigration, it is also beneficial to the country’s economy. In the short term, the presence of the ISP contributes to the financial development of postsecondary institutions. According to Usher (2021), the main reason the ISP has grown are the high tuition fees paid by this clientele, as they contribute significantly to boosting the revenues of postsecondary institutions. For example, since the 2008 economic crisis, the share of income from governments has stagnated while the share from tuition fees has greatly increased. Furthermore, while the revenue from tuition fees from the CBSP increased by 35% between 2008 and 2009 and between 2018 and 2019, the revenue from tuition fees from the ISP increased by nearly 400% (Usher, 2021). Recently, the aging of the Canadian population has reduced the pool of student population, thereby increasing postsecondary institutions’ interest in an international clientele (Firang and Mensah, 2022).

The economic benefits of this ISP are also felt across Canada. For example, the estimated contribution of the ISP to Canada’s gross domestic product in 2009 was $4.8 billion, while it was $21.6 billion in 2019 (Firang and Mensah, 2022). The contribution of the ISP to the economy is also evident in the fact that these individuals may integrate more easily into the labour market, compared to other categories of temporary or permanent residents.

Various studies show that, compared with immigrants trained abroad, this population presents a number of assets. In particular, individuals born abroad who have completed their postsecondary education in Canada have better success in the labour market compared to those who were educated in another country (Lu and Hou, 2017; Skuterud and Chen, 2018). Among the main factors identified in the literature as promoting the post-graduation work-to-school transition for the ISP, we noted knowledge of (or fluency in) at least one of Canada’s official languages, obtaining a Canadian degree, acquiring work experience in the country, a higher graduation rate in higher education, and opportunities to create a network of local contacts; in addition, ISP graduates encounter fewer problems around recognition of their degrees (Lu and Hou, 2017; Traisnel et al., 2016; Belkhodja, 2011; Chira, 2011; Skuterud and Chen, 2018).

International student population: a shared priority to support Francophone immigration

Given the multiple advantages offered by this immigrant population, the policies and initiatives implemented by various stakeholders—federal, provincial and territorial governments, postsecondary institutions, Francophone communities—perfectly align and demonstrate a shared willingness to facilitate the arrival of the ISP and their retention once they have graduated.

In fact, postsecondary institutions have shown a strong desire for internationalization over the past decade (DPMR, 2020). A study by Statistics Canada (2020: 1) indicates that the entire increase in the number of students in Canadian public universities and colleges from 2014–2015 to 2018–2019 is due to the growth in the number of international students.

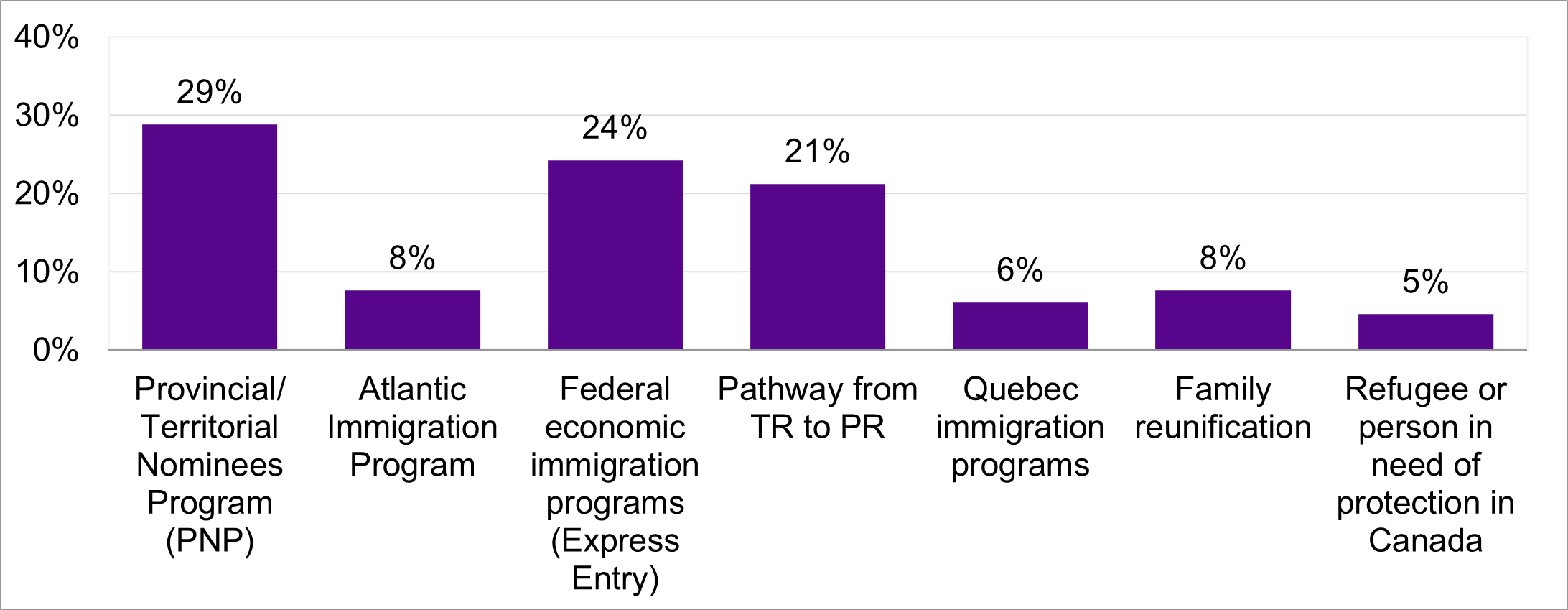

One of the 12 priority areas of the Community Strategic Plan on Francophone Immigration (2018), developed under the auspices of the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne (FCFA) du Canada, is to ensure collaboration between communities and government partners to facilitate the transition of temporary residents to permanent residents, particularly for members of the ISP who have studied in French in a minority context. This priority aligns with the policies of the Canadian government and the provinces.

In recent years, IRCC has made several changes to its programs to facilitate the transition to permanent residence for individuals born in another country and who graduated from Canadian institutions. These measures include awarding additional points to holders of Canadian degrees through Express Entry and extending the length of post-graduation temporary work permits (Esses et al., 2018). In addition, in several provinces, streams have been established under the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) that specifically target recent graduates (Choi, Crossman and Hou, 2021a). Support for the transition to permanent residency is also one of the components of the Government of Canada’s Francophone Immigration Strategy (2019).

International student population in a Francophone minority setting

A study conducted by Forest and Deschênes-Thériault in 2021 on behalf of the Department of Canadian Heritage provides an overview of minority-language postsecondary education. This study reports that members of the ISP made up a significant portion of the individuals enrolled in a French-language postsecondary training program outside Quebec in 2018–2019.

As for university studies conducted in 2018–2019, the proportion of members of the ISP in Canada outside Quebec of the total student population is 16.3%, whereas it is 15.6% when instruction is offered in French. However, significant interinstitutional disparities must be noted. For example, among the institutions included in this study, the proportion of ISP members varies from 2.2% (Campus Saint-Jean) to 30.7% (Université Sainte-Anne). Regarding college studies conducted in 2018–2019, a larger gap is observed between French-language programs and English-language programs. Thus, the total proportion of members of the ISP in Canada outside Quebec is 20.7% in colleges, compared to 12.2% when education is offered in French. Interinstitutional disparities are also quite pronounced between institutions located in a Francophone minority setting. Within the institutions covered by this study, in terms of college education, the proportion of members of the ISP varies between 15.3% (Université Sainte-Anne) and 60.3% (Université de Saint-Boniface) (see Appendix I for more details).

International student population: economic integration

The literature on the retention of international students highlights the fact that a majority of this immigrant population expresses an interest in staying in Canada in the longer term after graduating. For example, according to the study by CBIE (2022), 72.5% of ISP members intended to submit an application for a post-graduation work permit. This finding appears even more significant for individuals who studied in French outside Quebec, considering that 91% of members of the ISP who participated in the DPMR study (2020) stated their intention to seek employment in Canada after their studies.

It is therefore important to focus on the dynamics of this economic integration and the challenges associated with it; these aspects are essential to ensure the success of this population in terms of education, employment and/or migration. First, this economic integration benefits from being aligned with geographical considerations, as most international students intend to stay in the region where they studied (CBIE, 2022). Finding a job that meets a person’s expectations—especially in terms of qualifications, work experience and working conditions—significantly affects their retention (Chira, 2011; Traisnel et al., 2020; DPMR, 2020). For ISP members who studied in Francophone minority settings, language of work is included among these factors: “The ability to find a job, particularly in French, is one of the main factors that motivate the decision by students to stay not only in Canada, but in the region where they completed their studies” (DPMR, 2020: 57).

Some studies highlight the difficulties associated with finding a job that matches their field of study and skills level (Sall, 2019; Scott et al., 2015; Nunes and Arthur, 2013; Traisnel et al., 2020). Other research highlights the working conditions of individuals born abroad, which are rather unfavourable compared to those of their counterparts born in Canada, particularly in terms of discrimination, despite the fact that they hold a Canadian degree (Chira, 2011; Kamara and Gambold, 2011; Skuterud and Chen, 2018). In terms of income, the data also show a generally more negative experience for the ISP when compared with the CBSP (Skuterud and Chen, 2018).

Access to employment is key to promoting ISP retention. Accordingly, it is necessary to examine the factors that limit this population’s ability to integrate in the labour market of Francophone communities. This issue also underscores the importance of explaining how the post-graduation career paths of ISP members differ from those of graduates in the CBSP.

Francophone immigrant population: economic integration

Economic integration is a central theme of multiple studies on Francophone minority immigration. This is explained by the importance of employment as a retention factor, not only for international student graduates, but also for immigrants in general (Madibbo, 2014; Hypolite, 2012; Sall, 2019). This literature helps identify factors that hinder the economic integration of all immigrants and other factors specifically related to settlement in a linguistic minority setting. Some of these factors may contrast with those that influence a person born in Canada (DPMR, 2020; Sall, 2019; Skuterud and Chen, 2018). The six most frequently cited factors in the literature are presented in the following sections.

Importance of English for joining the labour market

Members of the ISP in a Francophone minority context face an additional challenge in terms of economic integration compared to their Anglophone counterparts: the need to be fluent in English in order to be employed. Faced with this linguistic challenge, French-speaking international students who speak little or no English often find themselves facing a choice: accept a more limited range of potential employment or spend more time learning English in order to broaden their field of expertise when searching for work (Madibbo, 2014; Esses et al., 2016; Chira and Belkhodja, 2013; Sall, 2019; Forest and Lemoine, 2020; DPMR, 2020). According to these authors, limited knowledge of English negatively impacts several aspects of the integration process: job search off-campus during studies; research and internship opportunities; employment opportunities related to their academic field; employment opportunities after studies; and professional development opportunities. The study conducted by the C.D. Howe Institute in 2018 highlights that these language barriers can partly explain the income gaps observed between individuals who graduated from a Canadian institution and were born in the country and those who were born abroad.

Despite this interrelation between English proficiency and economic integration in Canada outside Quebec, as documented in the literature, the fact remains that opportunities to learn English during studies are still rather limited for those in the ISP (DPMR, 2020; Traisnel et al., 2016).

Lack of well-established networks within communities

The establishment of a professional network is considered a key factor for the economic integration of all those born outside Canada (Vultur, 2015; Traisnel et al., 2019; DPMR, 2020). However, studies highlight the fact that the mere presence of the ISP on campuses is not enough to create real connections within the Francophone student and professional communities (Dunn and Olivier, 2011; Chira and Belkhodja, 2013; Traisnel et al., 2016). Considerable efforts are needed to build more bridges between postsecondary institutions and the communities around them, especially in terms of employability (Chira and Belkhodja, 2013).

For members of the ISP, limited opportunities to network and build connections with potential employers, and therefore demonstrate their expertise, pose a challenge in obtaining employment in many fields (Chen and Skuterud, 2017; Sall, 2019; Scott et al., 2015). In addition, in Canada, a limited number of job offers are publicly posted; as a result, networking often plays an important role in recruitment (Sall, 2019).

Compared to Canadians, immigrants come up against real challenges in finding internships and jobs that match their expertise and interests. A study on the subject notes that these challenges arise from, among other things, their more limited contact networks, but also to their more limited understanding of cultural codes, which reduces professional networking opportunities (Forest, Duvivier and Hieu Truong, 2020).

Acquisition of work experience in Canada

The lack of Canadian work experience during studies was highlighted in the study by Choi, Hou and Chan (2021) as one of the main factors accounting for the differences in labour market performance between members of the ISP and those of the CBSP.

According to many employers, work experience can sometimes be even more important than a Canadian degree (Hou and Bonikowska, 2018; El Masri, Choubak, and Litchmore, 2015; Minto, 2018). The study by WES (2019) reveals that those born abroad who gained work experience during their studies enjoy a higher rate of employment than those who did not, and they are more likely to have a job that aligns with their qualifications. The research by Lu and Hou (2017) even shows that the wage gap observed between individuals born abroad and those born in Canada narrows when work experience is taken into account in the comparison.

Thus, having less work experience in Canada proves to be a significant barrier to transitioning into the labour market after graduation (Dauwer, 2018; Trilokekar et al., 2014; Sall, 2019). However, as mentioned, networking opportunities between the ISP and employers are limited during studies, making it more difficult to obtain employment off campus. Furthermore, it is difficult for the Francophone ISP to find employment in their language when studying in a linguistic minority setting (DPMR, 2020). In addition, some professional opportunities offered by the federal government are reserved for individuals with permanent residency or Canadian citizenship (DPMR, 2020).

From the perspective of ISP members who studied in a Francophone minority setting, the inability to obtain relevant work experience during their studies influences the decision to settle elsewhere once the study program is completed (Traisnel et al., 2016; Forest, Duvivier, and Hieu Truong, 2020).

Experiences with discrimination

Many studies focus on the various forms of employment discrimination that immigrants may face, including discrimination based on accent, international student status, and ethnicity (Madibbo, 2016; Trilokekar et al., 2014; Mianda, 2018; Chira, 2013; Scott et al., 2015; Arthur and Flynn, 2011; Mulatris and Skogen, 2012). Often, when identity markers combine—for example, if someone identifies as Black, female and having an accent—an intersectional approach is necessary to better understand how patterns of discrimination become more complex (Mesana and Forest, 2020).

Several of these studies encourage us to examine the additional obstacles that visible minority individuals face, particularly those who identify as Black, in relation to their access to employment (Esses et al., 2016; Forest and Lemoine, 2020). Recent data from Statistics Canada highlight this reality: “Racialized individuals are generally more likely than their non-racialized and non-Indigenous counterparts to pursue a university-level education. Despite this, their labour market outcomes are often less favourable” (Galarneau, Corak, and Brunet, 2023: 1). This obstacle is all the more relevant because, in the context of this study, those from sub-Saharan Africa make up a significant portion of the student population in Francophone postsecondary institutions (Traisnel et al., 2016). They are more interested in staying in Canada after their studies than those from Europe (DPMR, 2020). This trend is similar to what has been observed among individuals studying in French or English (Esses et al., 2018).

In addition to the challenges associated with migratory status and belonging to a linguistic minority, visible minority individuals may also experience different forms of discrimination due to their ethnicity (Duchesne, 2018; Chira, 2011; Kamara and Gambold, 2011). The “status of being a minority within a minority is an additional obstacle, particularly for racialized minorities” with respect to integration (Fourot, 2016: 39). For example, Madibbo’s study (2016) on the marginalization experienced within the Francophone community discusses certain comments that highlight a distinction between so-called “native” Francophones and new arrivals of colour. In addition to hindering the development of a sense of belonging to the Francophone community, this differential treatment can lead to discrimination in the labour market and an underrepresentation of visible minorities in various employment sectors of the host community (Madibbo, 2010; 2016; Mulatris and Skogen, 2012; Sall et al., 2022).

Along with these forms of discrimination, there are those associated with being foreign-born. In his 2011 study, Oreopoulos demonstrates this type of discrimination by submitting similar resumes to various employers, some with “foreign-sounding” last names and others with more “Canadian-sounding” last names. The study results show that resumes from individuals with Canadian-sounding last names were significantly more likely to be selected.

Reluctance of some employers

Special attention must also be paid to employers due to the importance of their role in the transition from the ISP to the labour market. In fact, according to Firang and Mensah (2022), employers provide ISP members with jobs that allow them to reduce the often significant debt they incur during their studies (especially since it was contracted with financial institutions in their home country, where interest rates are higher). In addition, employers play an important role in several economic immigration programs in accessing permanent residence (Traisnel et al., 2020; Deschênes-Thériault and Forest, 2022).

While a majority of employers have positive attitudes towards hiring immigrants or members of visible minority groups (Fang et al., 2022), research indicates that some employers are hesitant in this regard (Oreopoulos, 2011; Fang et al., 2021; Chira and Belkhodja, 2013). Among the factors explaining this reluctance, we note the lack of familiarity with hiring individuals born abroad, language barriers, concerns related to retention, and the time investment required for a cultural transition (Fang et al., 2022; Chira and Belkhodja, 2013).

Furthermore, some employers prefer to offer internships to Canadians in order to maximize the chances of retaining them in their company after they graduate, without any administrative constraints related to their required status to work in Canada. In addition, in a linguistic minority setting, most employers and businesses are Anglophone, which can make it more difficult to hire Francophone foreign students (Traisnel et al., 2016).

Access to information and administrative issues

As we will see in the next section, the resources to support members of the ISP in their transition to employment and permanent residence are limited overall (El Masri, Choubak, and Litchmore, 2015). These individuals sometimes have difficulty obtaining information about temporary work permits and pathways to permanent residence. The information is not always easy to access and can be difficult to understand without assistance. During their journey, students may come across conflicting sources of information and make ill-informed choices that can have consequences on their ability to stay in the country after their studies (CCNB and UM, 2013; DPMR, 2020).

International students are dealing with contradictory information, numerous messages being sent without much coordination, as well as a complex and obstacle-filled immigration process, which seems to contradict the government’s immigration objectives (DPMR, 2020: 89).

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic has affected members of the ISP who were in Canada, but it also affected those who were seeking to settle there. Esses et al. (2021) note that members of this group have experienced a loss of income, have been isolated from their families, and have had limited access to emergency social assistance. In fact, just over a quarter of this population reportedly lost their main source of income, while 34% of these individuals had difficulty paying their rent or related expenses (Atlin, 2020). For ISP members who were outside Canada, the pandemic delayed their arrival and reduced their chances of gaining experience in Canada (Sultana et al., 2021). This situation caused high levels of stress, anxiety, and uncertainty (Firang and Mensah, 2022; Firang, 2020).

Gaps between needs and services offered for the school-to-work transition

It is clear that settlement services cannot solve all the problems that immigrants face on their journey. Still, access to French employability services is one factor among others that contributes to a successful school-to-work transition (Ba, 2018).

A gap seems to persist between the government and community’s willingness to promote the sustainable settlement of the ISP and the resources available to properly prepare them to integrate into the Canadian labour market after graduating and to face the challenges described in the literature (Chira and Belkhodja, 2013; Traisnel et al., 2019; Lowe, 2011; Chira, 2011).

The DPMR study (2020) adopts the theoretical life cycle approach regarding the journey from ISP to permanent residence, which helps illustrate the gaps between the actual needs of these individuals and the services available to them. According to this framework, the student’s journey begins with recruitment while they are still abroad and ends with their long-term establishment within the community. This study (DPMR, 2020: 60) outlines the six main stages of a international student's journey, namely:

- Recruitment overseas (before studies);

- Orientation and integration (upon arrival);

- Academic success and integration (during studies);

- Transition to employment or other educational programs (after graduation);

- Transition to permanent residence (after graduation);

- Long-term settlement in the community (after obtaining permanent residence).

Postsecondary institutions provide support to their students in the early stages of their journey until they graduate. However, the services offered by postsecondary institutions are more limited than those offered in the community, particularly in terms of economic integration (DPMR, 2020). The officials of the postsecondary institution services who were consulted in the context of the DPMR study (2020: 33) “believe that they are not able to replace community organizations in providing certain services to immigrants, such as employment services or language courses.” The services offered by institutions have a more limited goal of sharing information, while those offered by community organizations have a broader scope and aim for establishment in the community.

However, quite often, members of the ISP are not eligible for settlement, employment or language training services offered in the community. In fact, settlement services, employment assistance services, and government-funded language courses are reserved for permanent residents. Thus, during their training trajectory, members of the ISP who plan to enter the Canadian labour market after graduating are not able to benefit from all the available resources to help them prepare properly. For example, access to language courses funded by IRCC during the study period would be an asset for ISP members wishing to maximize their chances of a successful school-to-work transition (Traisnel et al., 2019).

This ineligibility for federally funded services also poses a problem during the transition to employment after graduation. New graduates are generally not eligible for the services offered by community providers, as most have a post-graduation work permit that still grants them temporary resident status. Furthermore, since they no longer have student status, they usually lose the benefits they had with their postsecondary institutions. The DPMR (2020) study highlights the limited contact that graduates have with their respective educational institutions after completing their programs.

The resources available for a successful transition into post-education employment are therefore limited, unless there is provincial funding that targets the Francophone ISP and thus facilitates the support that community organizations could offer this population. New Brunswick is one such example (Sall, 2019). The latter, however, is more of an exception. Generally, service providers in the community intervene late on the paths of international students, after they have obtained their permanent residency. However, it is during the study period that the need for resources to support successful economic integration is most important (Traisnel et al., 2019).

In addition to services directly related to employment, it seems that mental health services are limited and not well known by most members of the ISP. This problem seems to have been even more significant in recent years, given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the financial and mental health of this population (Firang and Mensah, 2022). Isolation, anxiety, and depression affect the academic and professional careers of ISP members. Indeed, while this issue affects the entire ISP, social and health services in French are generally difficult to access for Francophone minority communities (Bouchard, Colman, and Batista, 2018).

Profile of student graduate populations who participated in the survey

A total of 844 participants started to complete the questionnaire. After removing duplicates as well as responses from participants who were not eligible or who did not fully complete the survey, 340 questionnaires were included in the analysis. This number exceeds the initial goal of 250 participants.

Among the questionnaires analyzed, there are 173 CBSP graduates and 167 ISP graduates. Such a distribution was desired for a more accurate comparison during the analysis. Sociodemographic characteristics related to the education and employment of these populations are presented below.

Place(s) of study

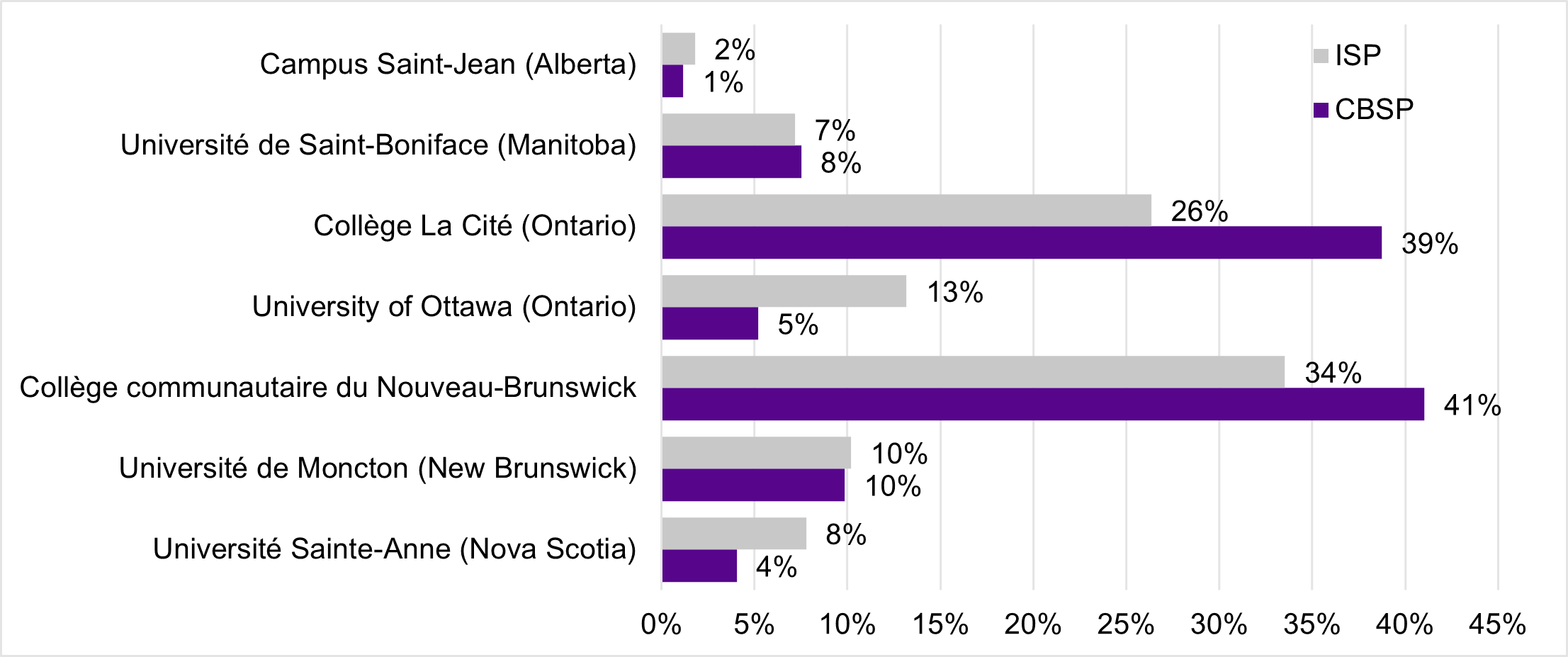

Overall, 52% of the participants graduated from a postsecondary institution in Atlantic Canada, 40% from an institution in Ontario, and 9% from an institution in Western Canada.Footnote 2

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 1

| CBSP | ISP | |

|---|---|---|

| Université Sainte-Anne (Nova Scotia) | 4% | 8% |

| Université de Moncton (New Brunswick) | 10% | 10% |

| Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick | 41% | 34% |

| University of Ottawa (Ontario) | 5% | 13% |

| Collège La Cité (Ontario) | 39% | 26% |

| Université de Saint-Boniface (Manitoba) | 8% | 7% |

| Campus Saint-Jean (Alberta) | 1% | 2% |

Sociodemographic overview

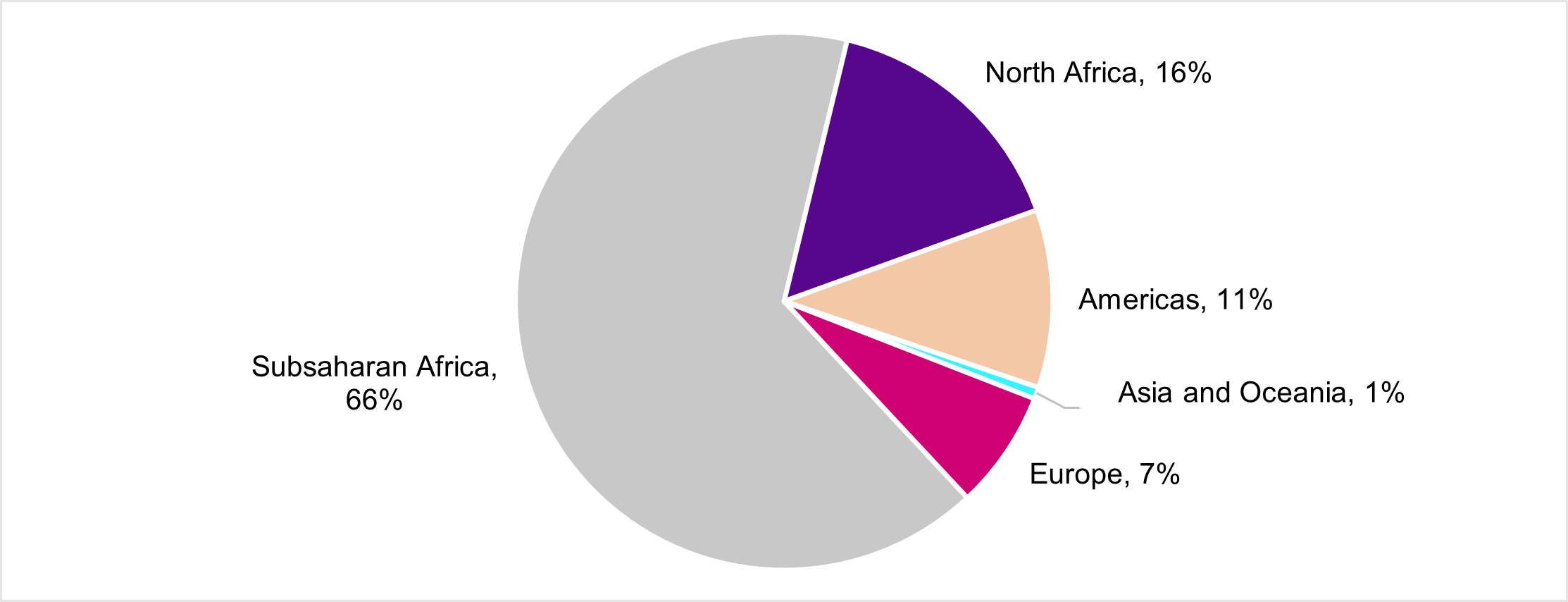

It should be noted that there is a difference between the two study populations regarding visible minority identification. Only 3% of CBSP members identify as visible minorities compared with 60% of ISP members. Among these, 92% identify as Black. Most ISP members were born in Africa, with 66% in sub-Saharan Africa and 16% in North Africa. At the time of responding to the questionnaire, most individuals who are part of the ISP had been in Canada for several years: 2% had been in the country for less than two years, 52% for two to five years, and 46% for more than five years.

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 2

| Subsaharan Africa | 66% |

|---|---|

| North Africa | 16% |

| Americas | 11% |

| Asia and Oceania | 1% |

| Europe | 7% |

Characteristics of programs of study

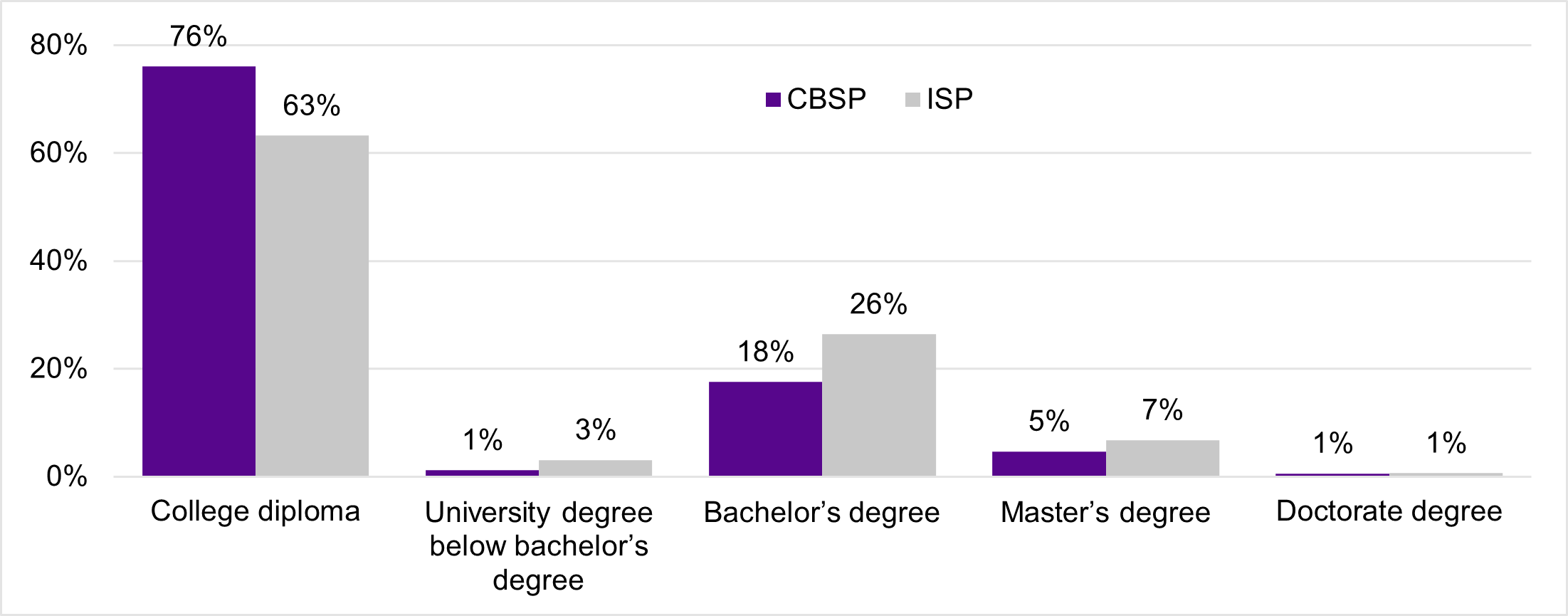

On average, between 2015 and 2022, ISP members had been studying in Canada over a total period of 2.7 years. This compares with 4.3 years among members of the CBSP. Most participants had completed only one study program in Canada (83% of the ISP and 73% of the CBSP). In our sample, individuals who obtained a college diploma at the end of their first study program in Canada are overrepresented compared to those who obtained a university degree for both groups under study.

Regarding the fields of study for the first degree, there are distinctions between the ISP and the CBSP. The five main fields of study for members of the ISP are as follows: 1) Business, management and public administration (37%); 2) Physical sciences, life sciences and technologies (11%); 3) Mathematics, computer science and information sciences (11%); 4) Humanities (10%); and 5) Architecture, engineering and related services (7%). By comparison, the five main fields of study for people in the CNSP are as follows: 1) Health and related fields (24%); 2) Business, management and public administration (21%); 3) Education (13%); 4) Visual and performing arts, and communication technology (8%); and 5) Social sciences, behavioural sciences and law (8%).

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 3

| CBSP | ISP | |

|---|---|---|

| College diploma | 76% | 63% |

| University degree below bachelor’s degree | 1% | 3% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 18% | 26% |

| Master’s degree | 5% | 7% |

| Doctorate degree | 1% | 1% |

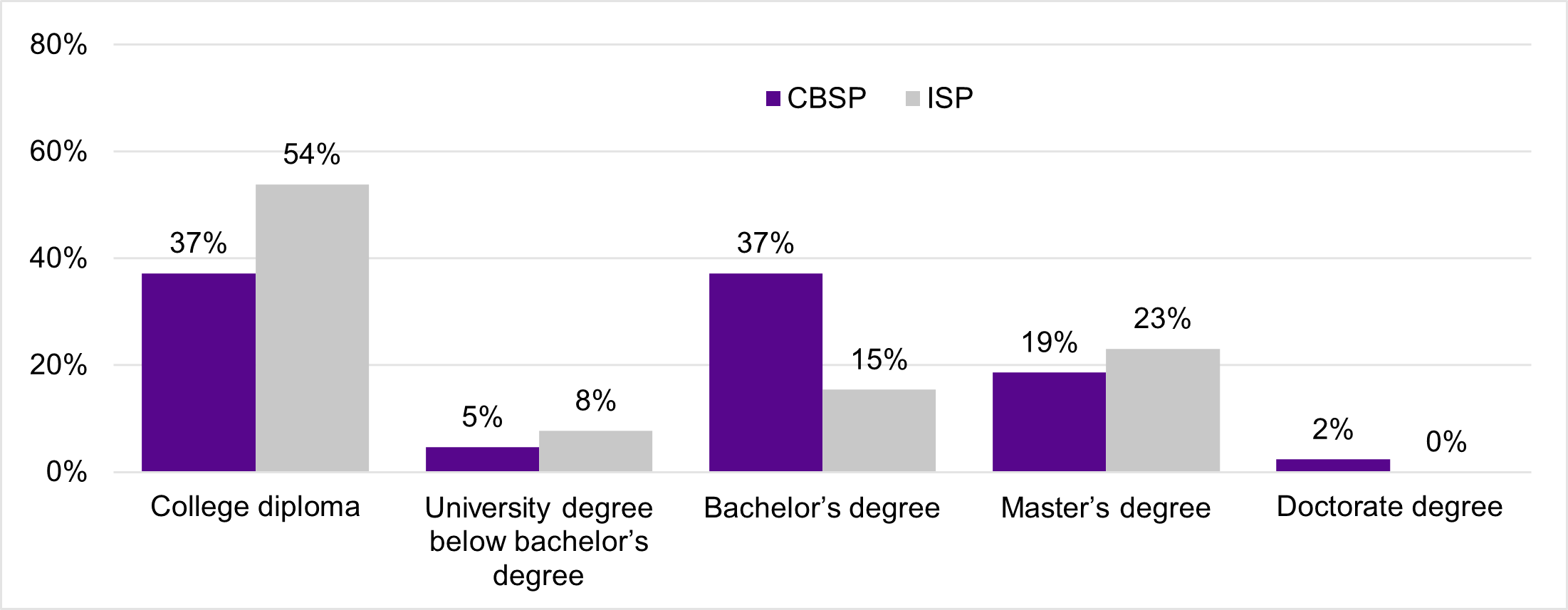

Those who completed a second study program (17% of the ISP and 27% of the CBSP) received more university degrees compared to those who completed a first program of study. Only a small number of participants (less than 2%) had completed a third program of study in Canada since 2015. It should be noted that two-thirds of ISP members (65%) had also obtained a postsecondary degree before coming to study in Canada. Of these individuals, two thirds graduated from an African institution (66%) and one fifth from a European institution (20%).

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 4

| CBSP | ISP | |

|---|---|---|

| College diploma | 37% | 54% |

| University degree below bachelor’s degree | 5% | 8% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 37% | 15% |

| Master’s degree | 19% | 23% |

| Doctorate degree | 2% | 0% |

Job search during and after studies

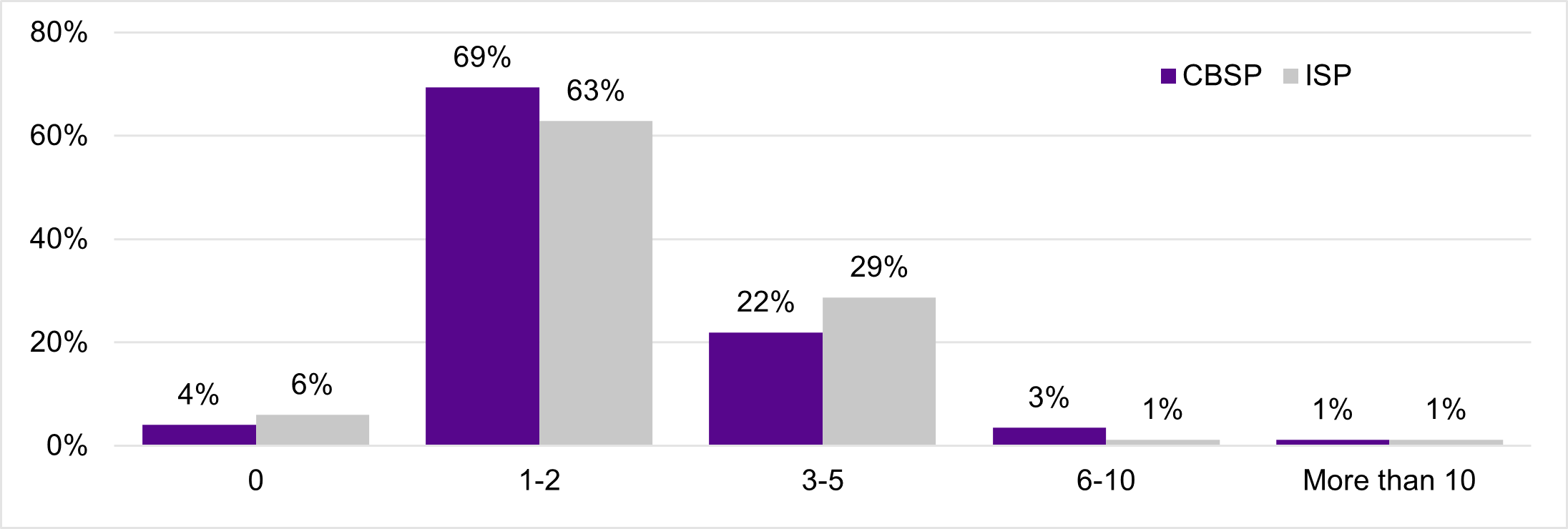

While job searching can be a complex, unsettling, and stressful experience for some, it is a mere formality or an opportunity for others. The interviews and the survey show that ISP members with degrees have encountered more difficulties during their job search. As a result, overall, these individuals had more experience and knowledge in job searching because they searched for longer periods, changed jobs more frequently, and more often held multiple jobs.

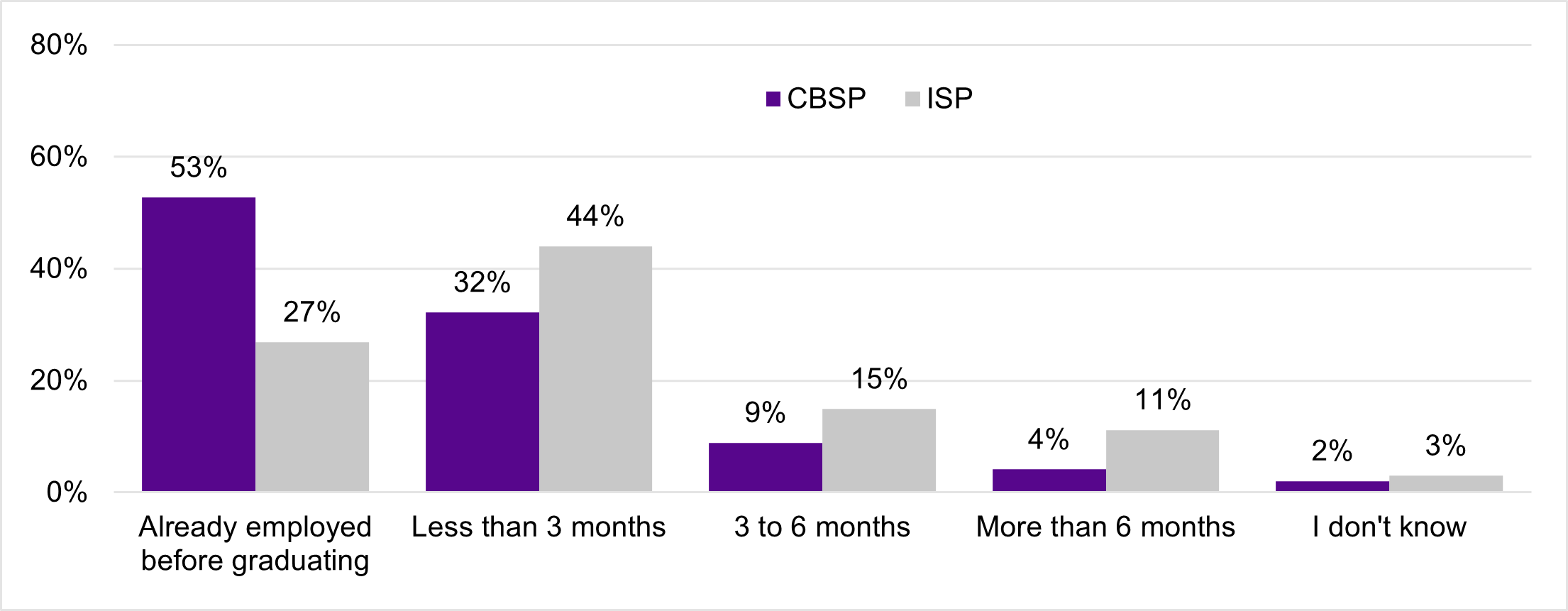

The survey allowed us to deepen our understanding of job search experiences after graduation. The results show that those born in Canada generally worked more months in the year following the completion of their studies than members of the ISP. In fact, 80% of the CBSP worked for 9 to 12 months in the year following graduation, compared with 73% of ISP graduates. This difference may be related to the fact that ISP graduates tend to spend more time actively searching for their first job after their studies. Indeed, just over a quarter (27%) of them already had a job before graduating, compared to over half (53%) of the CBSP.

Another trend worth noting is that ISP graduates (44%) are more likely to change jobs after obtaining their first degree, compared to CBSP graduates (33%). During the interviews, it was mentioned that in many cases, a person may accept a job that does not meet their expectations in order to support themselves, while waiting to find a job in their field of expertise. “I started working at a call centre, but after a while, I continued applying for jobs in my field” (USA-ISP).

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 5

| CBSP | ISP | |

|---|---|---|

| Already employed before graduating | 53% | 27% |

| Less than 3 months | 32% | 44% |

| 3 to 6 months | 9% | 15% |

| More than 6 months | 4% | 11% |

| I don't know | 2% | 3% |

In the interviews, participants shared their job search experiences during and after their studies. These interviews suggest that the duration of active job search is also longer for members of the ISP, particularly because they change jobs more often and more frequently hold multiple jobs. This longer job search is mainly due to the fact that ISP members face more obstacles during the process. These barriers are especially evident when comparing the number of resumes sent, the number of job interviews conducted, the types of experiences encountered in interviews or the employment opportunities they are aware of.

“I didn’t know anyone. I just applied online in response to a job offer with the company and I was hired. It took about three weeks to do the interviews.”

“I sent out [dozens and dozens of] resumes and people weren’t responding. Or I would call and they wouldn’t call back. It was a bit frustrating. I was thinking to myself, ‘maybe because I was an immigrant and had no experience?’ … I was told to adapt my resume for Canada. But that didn’t work. What worked is when I went in person.”

“Before finishing, towards the end of my studies, I had started applying. I was looking for something in communications, but I couldn’t find anything. I finished my studies and continued to apply for communications positions. … Then, I started a job as an administrative assistant. But now that I have permanent residence, I no longer have the same ambitions.”

“I’d printed out resumes and I was walking around town, dropping off resumes to managers of stores and restaurants that I passed by. That wasn’t a very effective method.”

When it comes to job search strategies, what some considered effective seemed not to be the case for others. Furthermore, these obstacles and success factors were presented as being closely interconnected. For example, a lack of knowledge about certain aspects, such as how to write a resume according to the Canadian format,Footnote 3 reduces the effectiveness of job searching. However, this difference is usually compounded by cultural or identity factors, such as being born outside of Canada, speaking English with a distinct accent or belonging to a visible minority. Overall, given the recurrence of similar experiences, we were able to identify the main strategies used as well as the obstacles and favourable factors related to them. These are presented below.

Use of the Internet

The survey shows that for 40% of ISP members and 35% of The CBSP, the main method used to find a first job after graduation is consulting online job advertisements. The interviews show that this method is indeed effective for finding a job, but not necessarily in the desired field. For example, like many in Atlantic Canada, one ISP graduate got his first post-graduation job in a call centre: “I did some research on the Internet in my field, but also in other places like call centres” (CCNB-ISP).

Canadian cultural codes

During the interviews, it became clear that knowledge of various Canadian cultural codes was a key factor in a successful job search, both for the ISP and the CBSP. These cultural codes are ways of being and doing things that are valued by employers in Canada. The surveyed individuals mentioned the importance of knowing how to act, such as smiling during an interview, making eye contact, writing a resume according to the Canadian format, finding companies that may offer them a job or presenting themselves to a potential employer, as a factor for success.

“If you understand the local culture well, you will have fewer barriers to finding a job. Things here are not done like in my country.”

“People didn’t call me because my resume was in French. I wasn’t aware that I had to do my resume in English.”

“It’s all about getting access to hidden job offers.”

“When it isn’t your country, you don’t know too much, you don’t know the right companies.”

“At first, I had trouble adapting to the job interview etiquette.”

The knowledge of these codes was never referred to as problematic for the CBSP, even though many people had very little job search experience and seemed less familiar with best practices in job searching. On the other hand, the answers provided during the interviews highlight that the ISP lacked knowledge of Canadian cultural codes, especially in the first few weeks after their arrival in Canada. A majority of the members of this population mentioned attending workshops that address these cultural codes, either upon arriving or as part of their courses (in college). However, ISP graduates mention that learning these codes also comes from having lived and worked in Canada. For this reason, knowledge of the main cultural codes had become less problematic by the time their studies were finished. However, after completing their studies, ISP graduates seemed to lack a deeper understanding of the cultural codes specifically related to their field of study, particularly because they were less likely to have worked in their field before graduating.

Opening up employers to ethnocultural diversity

The interviews, including those with stakeholders, confirmed that despite effective job search strategies, some employers simply have unfavourable biases towards individuals who have international student status, who were born abroad or who belong to a visible minority. Sometimes, there is no prejudice, but the employers are just not aware of good hiring practices. These prejudices and lack of knowledge of best practices were found to hinder the hiring of ISP members in various ways, such as when:

- Selecting individuals for an interview;

- Selecting one person from those invited for an interview;

- Accepting that people have different accents in English;

- Accepting that English language skills can be improved;

- Recognizing the value of expertise and degrees acquired abroad;

- Recognizing the value of foreign student status.

“All these efforts are made to recruit us at the university. … During our time in university, we are taught a lot of things. And then after we get our education, the province doesn’t benefit from our talents.”

“What really shocked me was that I saw Canadian students working at companies where I had applied for the same position yet never even got a response.”

“For my friends who had to work, they almost all worked in call centres. That’s where international students were able to get hired.”

Furthermore, in a context of labour shortage, a lack of openness or knowledge on the part of employers towards culturally diverse individuals not only seems to reduce these individuals’ likelihood of being hired, but also seems to further reduce the likelihood of being hired at the level of their qualifications. As a result, some non-specialized companies, such as call centres (Moncton, Winnipeg) and delivery services (Ottawa), have developed an organizational culture and procedures that promote the hiring of foreign-born applicants. These individuals make up the majority of the workforce in these companies and are often overqualified.

Conversely, when companies looking for highly qualified applicants develop an organizational culture that values cultural diversity in the workplace, it can be a factor that helps ISP graduates to find a job that matches their skills. Additionally, such an organizational culture, combined with targeted strategies, presents advantages, as this employer points out: “It’s a win-win situation. We have made a commitment to diversity and inclusion, both in our hiring strategies and in the workplace.” For example, a Moncton company conducts recruitment campaigns that highlight several of its employees who have immigration backgrounds to reach members of the ISP. In addition, guides for employers to recruit, hire, and integrate immigrants, such as the one from the Haut-Saint-Jean region, appear to contribute to knowledge-sharing that promotes cultural diversity in the workplace.

English proficiency

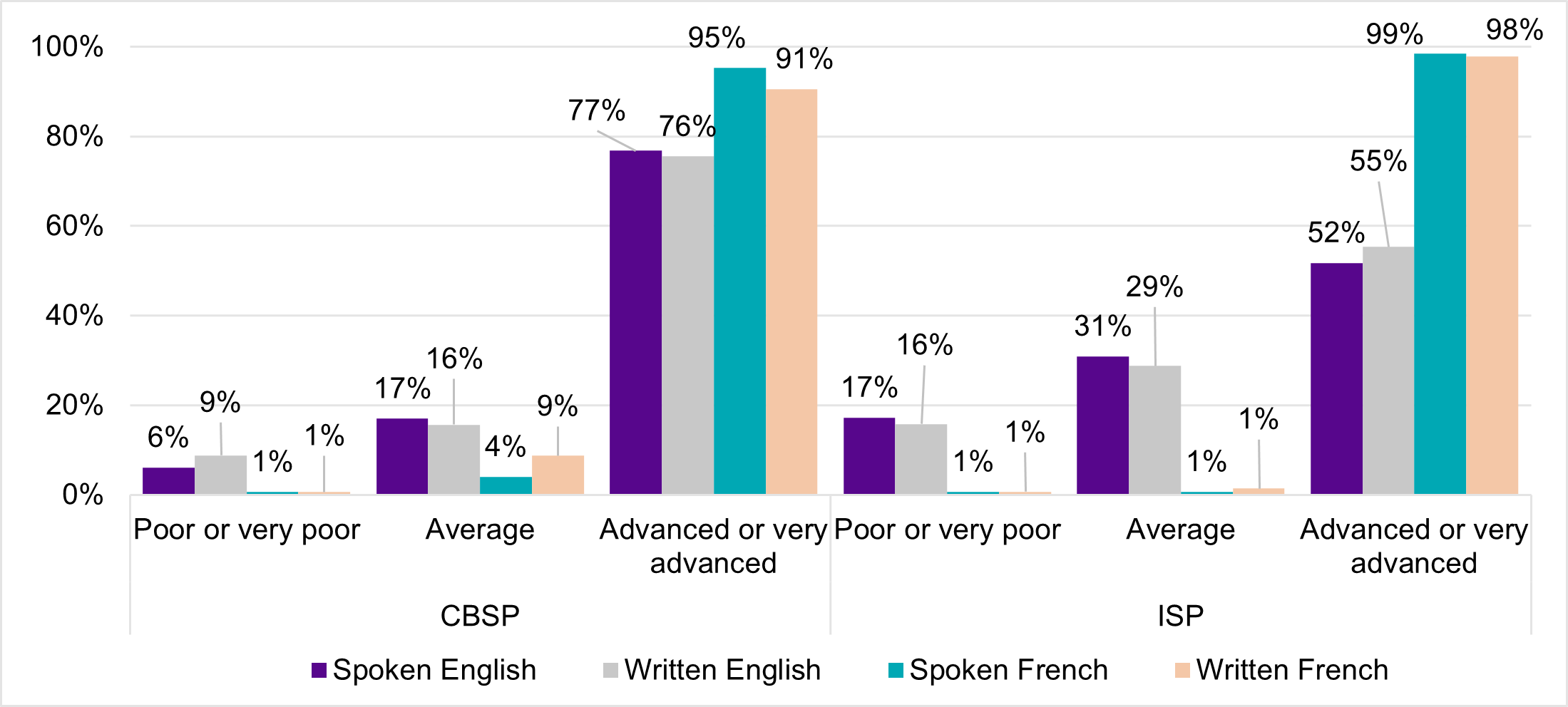

English proficiency is a factor that has a significant impact on the school-to-work transition in a Francophone minority context, as revealed by our literature review. The survey shows that members of the CBSP are more likely to have advanced proficiency in English, both orally (77%) and in writing (76%), compared to ISP members, of whom only 52% are able to express themselves in English and 55% to write in English. Even after completing a postsecondary program in Canada, nearly half of the members of the ISP consider themselves to have poor or average knowledge of English.

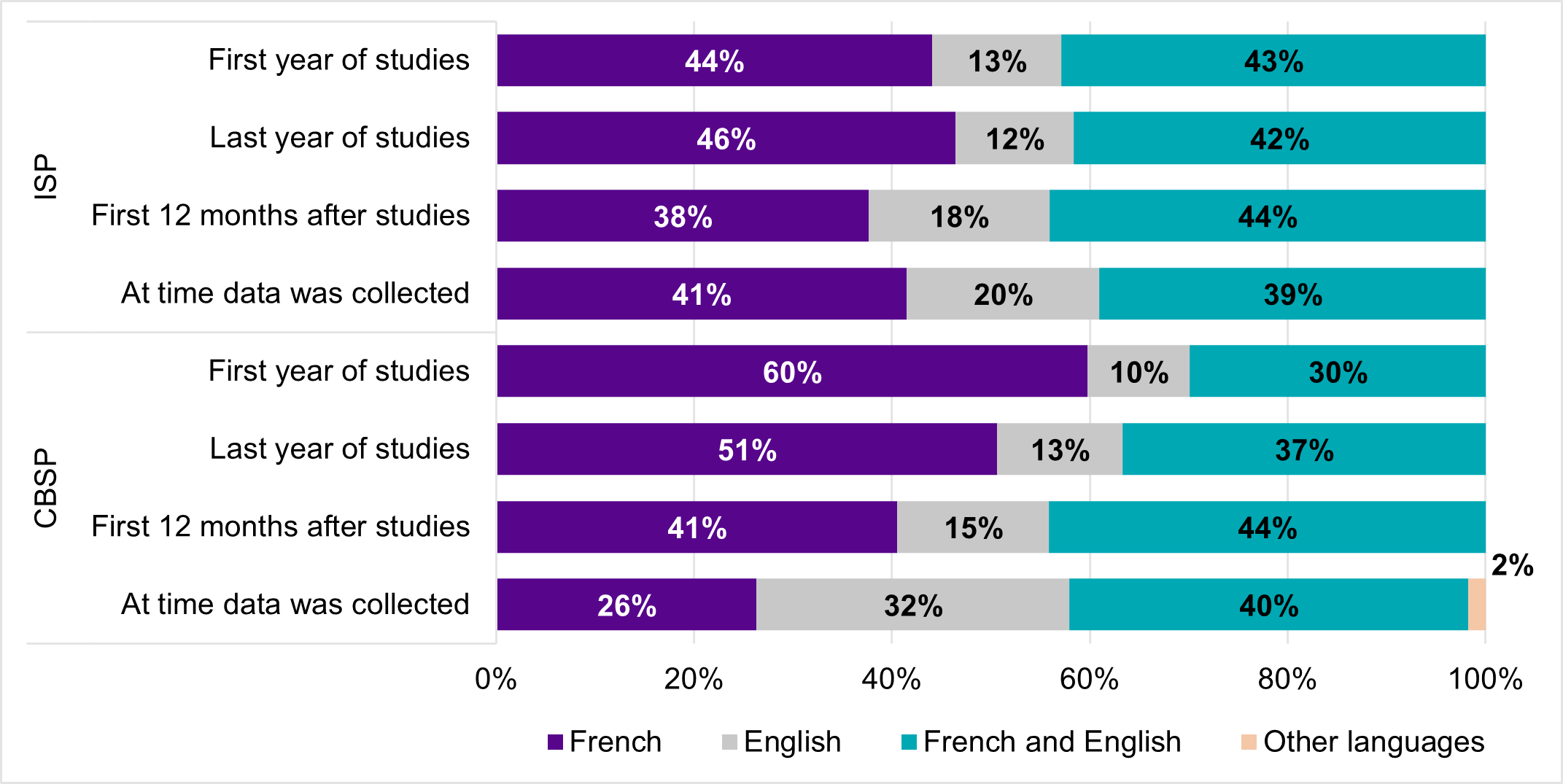

At the time of data collection, one third (32%) of CBSP members were employed in a job where the main language of work is English, compared to 20% of ISP members. The trend is the opposite for the working language during studies, since CBSP members are more likely to only use French at work during this period.

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 6

| CBSP | ISP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor or very poor | Average | Advanced or very advanced | Poor or very poor | Average | Advanced or very advanced | |

| Spoken English | 6% | 17% | 77% | 17% | 31% | 52% |

| Written English | 9% | 16% | 76% | 16% | 29% | 55% |

| Spoken French | 1% | 4% | 95% | 1% | 1% | 99% |

| Written French | 1% | 9% | 91% | 1% | 1% | 98% |

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 7

| CBSP | ISP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At time data was collected | First 12 months after studies | Last year of studies | First year of studies | At time data was collected | First 12 months after studies | Last year of studies | First year of studies | |

| French | 26% | 41% | 51% | 60% | 41% | 38% | 46% | 44% |

| English | 32% | 15% | 13% | 10% | 20% | 18% | 12% | 13% |

| French and English | 40% | 44% | 37% | 30% | 39% | 44% | 42% | 43% |

| Other languages | 2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

The interviews revealed that almost all members of the CBSP had a good level of English language proficiency when they started their postsecondary studies. Furthermore, members of the ISP often developed their English skills during their first jobs. Even by the end of their programs, for some born outside Canada, the fact remained that low fluency in English continued to be an obstacle when searching for work. Some who studied at the University of Ottawa said they had difficulty finding a job on campus because they had to be bilingual.Footnote 4 Others who were studying in Ottawa worked in Quebec, where there are more French-language jobs. Otherwise, only individuals who lived in New Brunswick or who worked for a Francophone community organization could work predominantly in French.

“In Ottawa, not speaking English was a big problem in my search for employment.”

“Well, I didn’t even really look in Ottawa, since I’m more Francophone … I looked for work more in Quebec.”

“The English language was a big problem for me. I was told that we could speak French. But the jobs were much more Anglophone.”

“The lady told me: ‘It’s French that we want for my team.’”

“My resume speaks for itself: right away, they wanted to interview me. But language continues to be a barrier.”

“I don’t speak English, so, really, I would have liked to really know the places where I could have positions that are only in French. I would have liked for those in charge of my program to give us a list of potential employers.”

Networking

Not surprisingly, good networking seems to be a key factor of success in job search, whether during or after studies. Similarly, whether or not they were born in Canada, individuals who are able to make use of their networks seem to have more success. Networking is essential because it allows students to connect with potential employers, find job opportunities, improve their job search strategies and learn cultural codes faster.

During studies

Newly arrived ISP members in Canada are at more of a disadvantage. Considering that a majority of this population are seeking employment in the first few weeks following their arrival in the country, if they manage to make use of a network, it is usually limited to a few foreign colleagues. Conversely, Canadians who start their postsecondary studies and are looking for employment often benefit from larger and more diverse personal and professional networks.

The more ethnically diverse networking of ISP members is notably linked to a broader issue of exclusion, with individuals born abroad often finding themselves among others from their own region of origin, while those born in Canada tend to group together: “Students from Canada create very close relationships and the internationals find their family among the [other] internationals” (USA-ISP). Some people interviewed have denounced this situation and suggest that institutions do more to encourage cultural integration, for example, during teamwork.

“I got my first job for the federal government at the age of 16. … I heard about this program from my mother, who works for the federal government. That’s how I applied.”

“And knowing that I was looking for a job, my friend said: ‘Hey, I gave your name to my supervisor and my manager will give you a call.’ And so I was invited to an interview.”

“We didn’t have someone working here or there who could put us in contact. I think that to quickly land a job here, it mostly depends on word of mouth.”

“Volunteering opens the door to incredible networking opportunities.”

“I was asking the former students from my community. When they had no reply, I asked a CCNB employee and on the Internet. Before coming here, I had already joined a group [on WhatsApp]. There were alumni and [foreign] students from the college in that group.”

“In call centres, it was practically all foreign students working there. It was pretty easy to get a job when you have a bunch of friends working there.”

“We have a network of people from West Africa, so there are always people who can give you information.”

A person benefits from expanding and specializing their networks at the end of their studies, as the nature of their networks will impact their ability to find a job that matches their education and expertise. In fact, at the end of their studies, more people from the ISP had jobs not aligned with their expertise, but ones they had found thanks to their foreign colleagues—for example, in call centres (in Atlantic Canada). Individuals trained to practise a specialized profession or trade required more targeted networking: “Networking between students, towards the end of our program, was very big, because we would approach one another and ask: ‘Ah! You had experience there. How was it?’” (USB-CBSP). In this regard, job fairs organized in colleges and universities are highly appreciated by the ISP, as these fairs allow them to learn about new companies. “A manager from the company had come to a job fair. It was my first contact with [this person]” (CLC-ISP).

During interviews with stakeholders, one employer highlighted the positive outcomes associated with establishing close relationships with the most relevant training program managers in relation to the profiles sought for new employees: “I need employees who have graduated from computer science programs. I am in contact with the department manager for internships. When I have job openings, I circulate the offer through him. These are programs with a lot of foreign students, so I have a lot of them as my employees.” Thus, in addition to hosting interns, this employer shares job offers with ISP members through their respective educational institutions shortly before graduation.

After studies

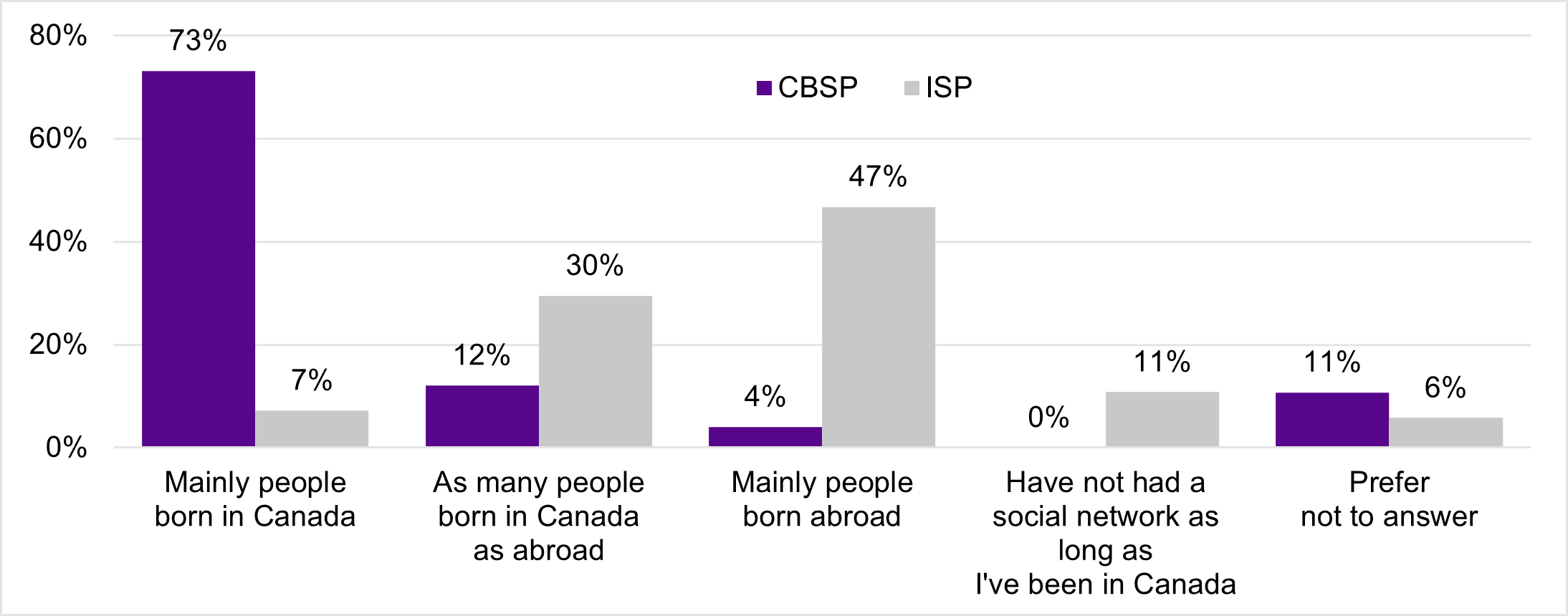

The survey allowed us to address the state of networking among the targeted populations after graduation. CBSP individuals derive the greatest benefit from networking when it comes to job searching, since after graduation, they still have a larger network of local contacts and more relevant Canadian work experience. Approximately one third (36%) of the CBSP found their first job through personal contacts and one quarter (25%) through a former employer. These proportions are 27% and 13% respectively for ISP members. It should be noted that both groups are equally likely to find employment through contacts at their educational institution (14%).

However, there is a difference when it comes to relationships formed outside of postsecondary institutions. This can be explained partly by the fact that for nearly half of the members of the ISP, their social networks in Canada are predominantly made up of people born abroad (47%). On the other hand, three quarters (73%) of the Canadian-born student population have a network made up predominantly of people born in Canada. This problem related to the lack of local relationships seems to diminish over time. With regard to the most recent job found, both ISP graduates and CBSP graduates tend to rely on local contacts (36%). However, it is important to note that a difference persists regarding past work experience: Fifteen percent of CBSP graduates found their current job with an employer they have previously worked for, compared to only 3% of ISP graduates.

Source: Survey of international students and Canadian-born students in seven post-secondary institutions in Canada outside Quebec, June–October 2022.

Text version of figure 8

| CBSP | ISP | |

|---|---|---|

| Mainly people born in Canada | 73% | 7% |

| As many people born in Canada as abroad | 12% | 30% |

| Mainly people born abroad | 4% | 47% |

| Have not had a social network as long as I've been in Canada | 0% | 11% |

| Prefer not to answer | 11% | 6% |

Canadian experience and recognition of prior learning

Canadian experience is often required by employers as part of the recruitment process. It follows that the ISP appears to be at a disadvantage compared to the CBSP. Several testimonies have stressed the importance of this criterion, whether in terms of finding an unskilled job or a job after graduating. In the first year of studies, this obstacle seems to result in ISP members taking longer to find a job or ending up in jobs that do not match their qualifications.

“Maybe they will call you and ask you questions: ‘Do you have any experience in the field?’ And you’ll say: ‘No, but I’m ready and willing to learn.’ But you don’t have experience. So, they don’t want to train someone from scratch. So they’re going to say something nice to you like: ‘OK, we’ll call you back.’ But you know they never will. And that’s exactly what happens. They don’t call you back.”

“Foreign students should be trusted more, even if they don’t have experience here in Canada. If we are given training, we can do the job just like anyone else.”

“As a student in computer science, it really is preferable for us to work part time in our field. But me and the other international students, we really struggled to find opportunities in that field to gain at least some experience before graduating.”

On the other hand, after graduating, the challenge is to find work commensurate with the expertise and qualifications acquired. And when looking for a skilled job, members of the ISP felt that employers were more reluctant to recognize their acquired experiences and diplomas obtained outside of Canada. International students have said it was important to gain experience in their field during their studies. In most fields of study (computer science, nursing, administration), people can work in their specialty before graduating. Thus, once they have graduated, individuals who have already gained Canadian experience directly related to their field of study are given preference. It seems that members of the ISP are not always aware of this requirement and how to find semi-skilled jobs.

Specific aspects of searching for internships

“We don't know anyone. No one replies to you. I was on the verge of cracking. Then someone told me about [company name].”

“Me, I never heard back about the positions that I applied for. … Others, Canadians, had internships before the international students.”

“I never got the internship. I think that, maybe, being born here might have helped.”

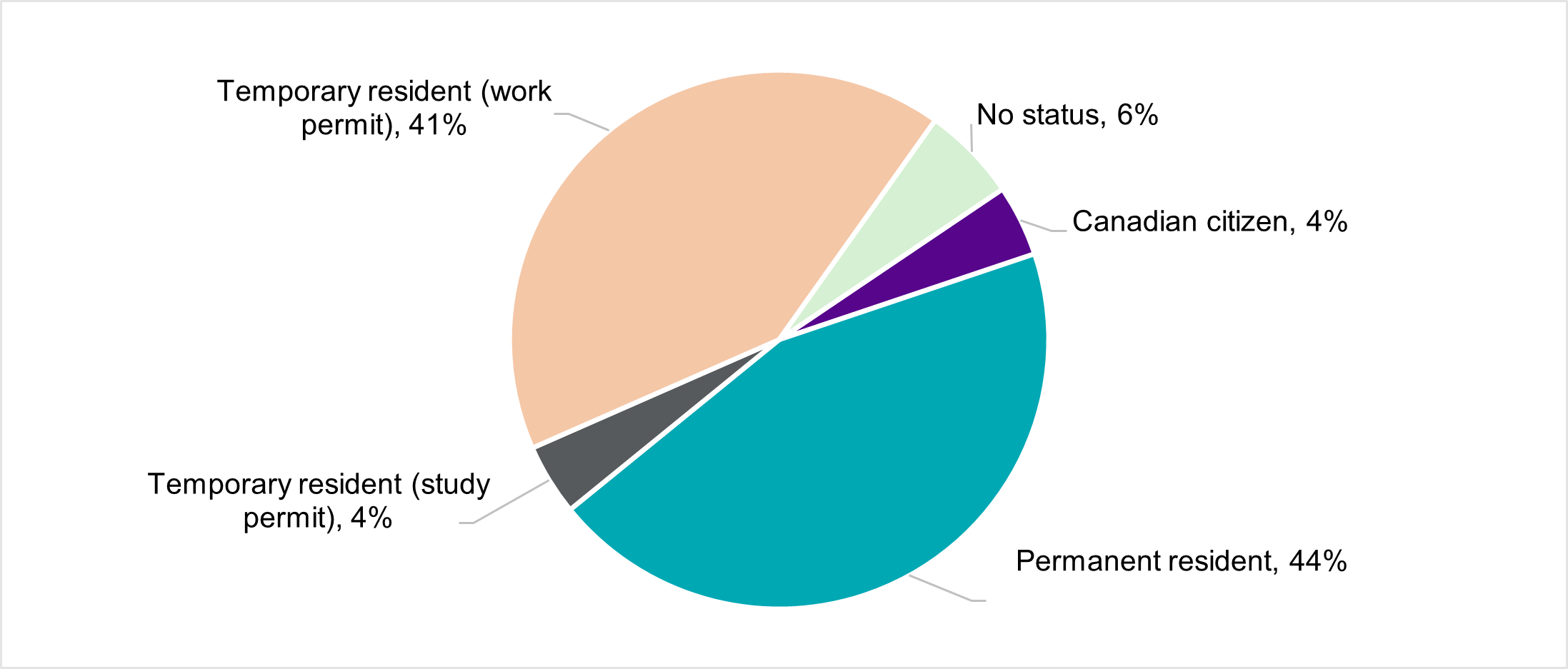

Several people interviewed had to complete an internship during their studies. For the CBSP, finding an internship was not a problem and often led to employment after graduation. The experience of ISP members in terms of internship search has generally been positive. Still, this search has sometimes been anxiety-inducing and laborious, as it was more difficult for these individuals to find internships or receive positive responses from recommended places. It seems that, in these cases, Canadians were given preference.