Settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in a Francophone OLMC: The case of Winnipeg and Saint Boniface, 2006 to 2016

Study on French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg and Saint Boniface.

By Faiçal Zellama, Chedly Belkhodja, Patrick Noël, Moses Nyongwa, Mamadou Ka and Halimatou Ba

February 16, 2018

This project was funded by the Research and Evaluation Branch at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada or the Government of Canada.

Ci4-185/2018E-PDF

978-0-660-28488-0

Reference number: R27a-2016

Table of contents

- Abbreviations

- Abstract

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Research results: The voice of refugees

- 1.1 Profile of refugees

- 1.2 Trajectories of refugees

- 1.3 Appraisal of government policies and programs in light of settlement experiences

- 1.4 Integration of refugees in Francophone communities

- 1.5 Challenges to the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees

- 1.6 Services received by French-speaking refugees

- 1.7 Evaluation by French-speaking refugees of services received

- Chapter 2 Research findings: What practitioners have to say

- Chapter 3 Analysis, discussion and recommendations

- Appendix A: Bibliography

- Appendix B: Interview Templates for Group Interviews

- Appendix C: Facilitator guide for interviews with focus groups

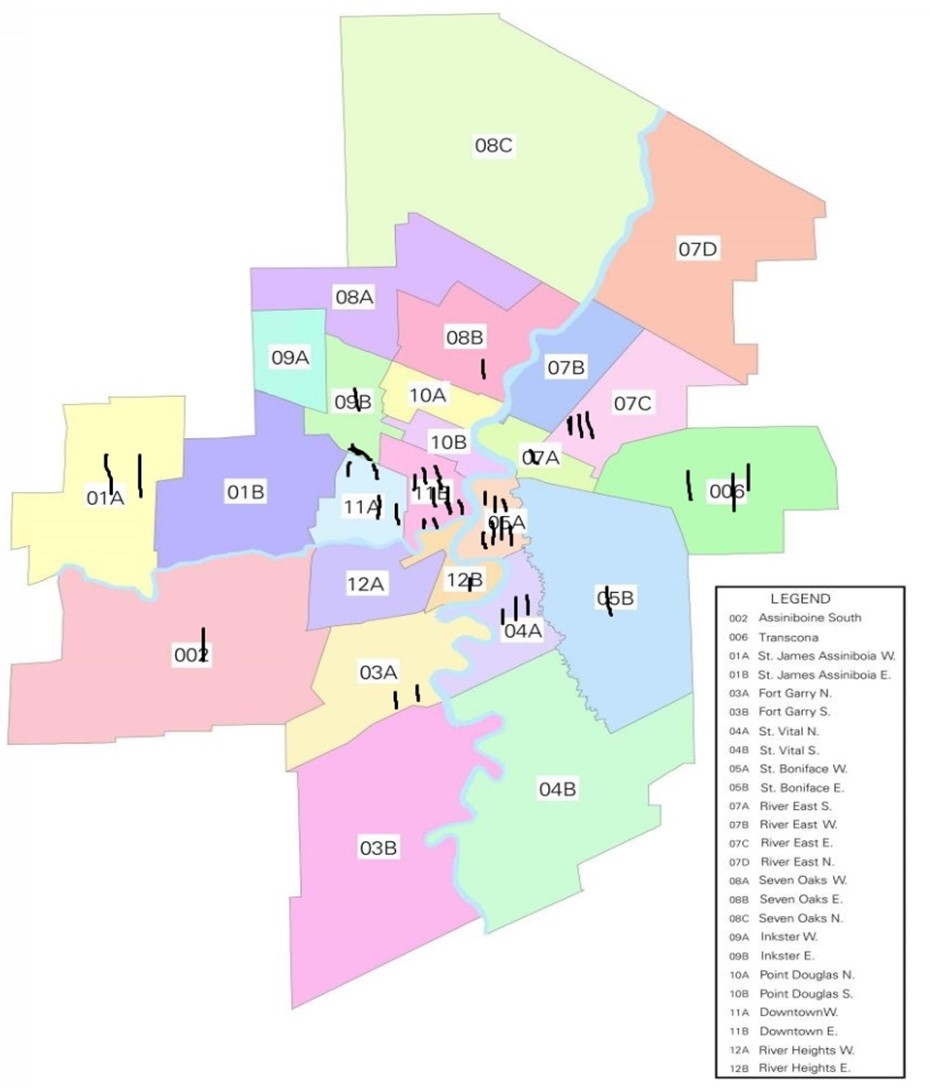

- Appendix D: Distribution of survey participants within the City of Winnipeg

- Appendix E: Description of the agencies participating in our survey

Abbreviations

- AF

- Accueil francophone

- CAMM

- Canadian Arab Association of Manitoba

- CDEM

- Economic Development Council for Manitoba Bilingual Municipalities (Conseil de développement économique des municipalités bilingues du Manitoba, CDEM)

- OLMC

- Official Language Minority Community

- DSFM

- Division scolaire franco-manitobaine

- UNHCR

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees

- IPW

- Immigration Partnership Winnipeg

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRCOM

- Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba Inc.

- MIA

- Manitoba Islamic Association

- RIF

- Francophone Immigration Networks (Réseaux en immigration francophone, RIF)

- SFM

- Société de la francophonie manitobaine

- USB

- Université de Saint-Boniface

- WP

- Welcome Place

Abstract

This research report examines the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In order to better understand this issue, the report starts by contextualizing it historically and conceptually. Chapter 1 focuses on the experiences of refugees. We examine the profile of the French-speaking refugees participating in our research, their trajectories from their home country to Canada, their assessment of government programs relative to their settlement, and their sociocultural and economic integration and challenges. The chapter ends with a presentation of the services received by the refugee participants interviewed, whom also provided an assessment of these services. Chapter 2 focuses on the perspectives of organizations serving newcomers in Winnipeg. After presenting a profile of the organizations that participated in the research, we examine the challenges that these stakeholders have experienced regarding the settlement and the integration of francophone refugees, the services offered by the organizations, their assessment of these services and their view on the government settlement and integration programs for refugees. Chapter 3 analyses and discusses the results presented in the two previous chapters in light of the main issue identified. The settlement and integration of francophone refugees in Winnipeg are examined through six variables in terms of gaps, the issues these raise and the relevant recommendations: housing, employment and training, education, official languages acquisition, health and social integration.

Executive summary

This research report is in response to a request for proposals issued by IRCC in the summer of 2016, for settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In order to understand this issue, the report starts by contextualizing it historically and conceptually. The notions of immigration, of language policy, of official language minority community and of refugees are closely intertwined. We then define the research methodology of the project. It is mostly of qualitative nature, although we have collected some quantitative data through socio-demographic index cards that each refugee participant had to fill before his/her interview. The qualitative analysis draws on individual interviews and group discussions. We conducted 29 individual interviews with French-speaking refugees and two group discussions involving 11 other French-speaking refugees. We also conducted 17 interviews with organizations serving newcomers in Winnipeg. These interviews allowed us to have a more global perspective on the question of the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg, taking into account both the refugees and the organizations serving them. The report has three chapters. The first two present a descriptive analysis. Chapter 1 focuses on the experiences of refugees. After presenting the profile of the refugees participating in our research through a few sociodemographic variables, we examine their trajectories from their home country to Canada, a trajectory that affects their settlement and integration in the host society. We then focus on their perception of government programs relative to their settlement, their sociocultural and economic integration and challenges. The chapter ends with a presentation of the services received by the refugee participants interviewed who also gave us an assessment of these services. Chapter 2 focuses on the experiences of organizations serving newcomers in Winnipeg. After presenting a profile of the organizations that participated in the research, we examine the challenges that stakeholders have experienced regarding the settlement and the integration of French-speaking refugees, the services they offer, their assessment of these services, and their view on government settlement and integration programs for refugees. Chapter 3 analyses and discusses the results presented in the two previous chapters in light of the issues identified. The settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg are examined through six variables, in terms of gaps, the issues they raise and the relevant recommendations: housing, employment and training, education, official languages acquisition, health and social integration.

Recommendations relative:

To housing

- The number of transition housing units for refugees could be increased.

- The federal government could learn from the best practices of private sponsorship of refugees.

- The federal government could invest more in social housing.

- The federal government could create a program to help refugee housing.

- Refugee housing could be more decentralized.

To employment and training

- Training centers for refugees could be created.

- Current employment services could be replaced by job market support services.

- Employment and training services offered to newcomers could be more decentralized.

To education

- The modalities of education given to French-speaking refugees could be logistically reorganized in order to better respond to their needs.

- The content of education could be modified in order to be more relevant to the specific and diverse needs of French-speaking refugees.

- Financial incentives could be created to make it easier for French-speaking refugees to better balance work and education.

To mastery of official languages

- Language courses could be organized in cooperatively to allow newcomers to have a direct contact with the workplace and the language used there.

- Languages courses could be better funded.

- Translation activities in community organizations involved with refugees could be supported.

- French-speaking families could be matched to English-speaking families to allow for exchanges and fast language acquisition.

- Activities could be organized to make French language learning attractive.

- Language instructors could be made aware of the problems experienced by refugees and give them psychological support as soon as they arrive on Canadian soil.

To health

- The federal government could increase the resources in order to provide better care for refugees as soon as they arrive in Canada.

- Organizations offering front-line services could be allowed to direct refugees to health professional as soon as they arrive in Canada.

- Health for refugees could be approached from a holistic perspective; that is by looking at all of the principal determinants of health - employability, environment, mental health – physical health being only the tip of the iceberg.

To social integration

- Some social organizations involved in the social integration of refugees in the host community could receive public funding or be better funded.

Introduction

Background

This study examines the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg and St. Boniface. The study focuses on refugees who settled there over the last ten years (2006-2016). To understand this issue, we interviewed 41 French-speaking refugees and 17 practitioners from agencies serving newcomers. Historical considerations and conceptual explanations are also necessary for a full understanding of this theme.

Canada’s history cannot be understood without taking into account the important role played by immigration in its various forms: economic immigration, family reunification and refugees. Canada has been built in large part by successive waves of immigrants who have contributed to the country’s wealth and diversity. Immigration to Canada has been legislated since 1869, barely two years after the British North America Act created the Dominion of Canada. It would not be until a century later, in the wake of the tabling of the Reports of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism and the adoption of a language policy recognizing French and English as the two official languages of Canada (1969), that proficiency in one of these languages became a selection criterion for immigration. Since that time, Canada’s language policy and immigration policy has been closely linked.

In this regard, Part VII of the Official Languages Act stipulates that the Canadian government must ensure positive measures are taken to not only foster the promotion of official languages, but also to enhance the vitality of OLMCs. One of the ways in which the Canadian government seeks to (re)vitalize OLMCs is through immigration. Yet, according to a recent report by the Commissioner of Official Languages, “Francophone minority communities outside Quebec received little benefit from...immigration” (Fraser et al., 2014: 5). From this perspective, the challenges such communities and the immigrants who decide to settle and integrate in them face must be understood; immigrants and communities alike will benefit.

Winnipeg and St. Boniface are an example of a Francophone OLMC that welcomes immigrants. Winnipeg, proud of its love of French, joined the Réseau des villes francophones et francophiles de l'Amérique in 2015 (Radio-Canada, 2015). In 2012, Chedly Belkhodja et al. produced for IRCC a typology of Francophone OLMCs in which Winnipeg is portrayed as a community which, despite having “significant assets” such as Francophone schools and universities, some government services in French and cultural vitality contributing to a dynamic economy, nonetheless faces a number of specific issues in part related to the fact that French does not have as favourable a status here as in other Francophone OLMCs in Canada, such as those in New Brunswick and Ontario, and that the proportion of Francophones is particularly low (4%) and continues to wane, despite the ongoing migration (Belkhodja et al., 2012).

It is clear that Winnipeg as a welcoming place for immigrants has been the focus of a number of studies that have looked at the role of housing and neighborhoods in the immigrant resettlement process (Carter et al., 2009a and b), newcomers from Francophone Africa and housing (Ba et al., 2011), access to services in French (Buissé, 2005; Nyongwa, 2012), the cultural and linguistic identity of new Francophones (Nyongwa and Ka, 2015) and immigrants’ impressions regarding their new home (Freund, 2015). In accordance with the request for proposals, this study focuses on a category of immigrants that has received little attention in the literature on Francophone immigration in Winnipeg, namely French-speaking refugees. It is even more worthwhile to focus on this category of immigrants to Winnipeg, since they account for a fair share of the immigrants that this city receives each year. This makes Winnipeg a unique case in the study of Canadian immigration issues.

Our definition of “refugee” is a person requiring protection under international law. In Canada, refugees belong to one of three categories of immigrants under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, the others being the “family class” (family reunification) and the “economic class” (economic immigration). Canada is home to two main types of refugees: government-assisted refugees (GARs) and privately assisted refugees (privately sponsored refugees - PSRs).

Since immigration is a shared jurisdiction in the Canadian federation, Manitoba, like other provinces, has an immigration department, Manitoba Labour and Immigration. Immigration has long played a significant role in Manitoba’s growth and prosperity. Manitobans continue to welcome and support refugees from around the world in their communities. In 2014, Manitoba welcomed 16,222 immigrants, accounting for 6.2% of total Canadian immigration. The most recent immigrants to Manitoba come from more than 150 countries. In addition, 9.2% of the province’s immigrants (1,495 individuals) were refugees–the highest number of refugees in Manitoban history. Moreover, 6% of GARs (435 individuals) and 22% of PSRs (1,004 individuals) settled in Manitoba, the highest per capita in Canada. About one-third (29%) of Manitoba’s refugees were government-sponsored, while two-thirds (67%) were sponsored by the private sector. About 57% of the GARs came from Somalia, Iraq, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Eritrea. About 92% of PSRs came from Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia and the DRC.

It is important to take into account the fact that French is not one of the 10 most common mother tongues of immigrants, despite Manitoba having a Francophone Immigration Strategy. While Manitoba has welcomed more than 400 Francophone immigrants each year since the early 2010s, these numbers have never accounted for more than 4% of the total number of immigrants settling in the province—a rate far below the target of 7% set by the province and the community ten years ago (Radio-Canada, 2016). In 2014, Manitoba welcomed 407 Francophone immigrants, mainly from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali and France. Of these immigrants, 60 were refugees, 50% of whom were sponsored by the private sector and 40% of whom were sponsored by the government. Lastly, Winnipeg was the main destination for 85.1% of immigrants to the province (13,850 individuals). Winnipeg ranks 6th among Canadian cities receiving the most immigrants. Our study sought to better understand the place of Francophone refugees in OLMCs in Winnipeg between 2006 and 2016.

A study on French-speaking refugees in the Winnipeg OLMC is important for a number of reasons. First, settlement and integration of refugees is a priority in the Government of Canada’s immigration strategy. Furthermore, it will give policy makers, those at IRCC in particular, better knowledge to ensure optimal social cohesion in the OLMC and to optimize the social and economic prosperity not only of newcomers to Canada, but also of Canadian society as a whole. Moreover, the proposed study is relevant given that the Société de la francophonie manitobaine began a community consultation in 2015 to assess its concerns and major challenges. To this end, various projects have been implemented and we consider our project to be central to the process of redefining the identity of Franco-Manitoban society (SFM, 2017). This process cannot be complete without taking into account Francophone newcomers, including refugees.

Study objectives

The study aims more specifically at understanding the needs of immigrants and their immigration experiences, and at possibly improving existing services and remedying potential shortcomings. We have set six objectives to operationalize the issue:

- Document the experiences of French-speaking refugees in St. Boniface and Winnipeg with a view to deriving recommendations from them to facilitate the settlement and integration of newcomers. We will seek to better understand the specific issues raised by the settlement and integration of these “double minority” refugees in the Winnipeg OLMC. What are the factors and conditions which can influence settlement and integration (needs of refugees and access to services meeting their needs such as health care, religion, housing, child care, education; or incidents of discrimination)?

- Establish a socio-economic profile of the refugees (country of origin, sex, age, education). Identify the cultural, social and religious characteristics of refugees that facilitate or hinder integration as well as the strategies that promote the successful integration of refugees. Do some of these refugees experience more integration difficulties, discrimination and stigmatization according to their origin and their refugee status? Which resources and skills, language for example, do refugees mobilize to overcome difficulties? Do they turn to the Anglophone or to the Francophone community for support? Do Anglophone and Francophone practitioners working with refugees collaborate? What positive experiences have French-speaking refugees had in the communities (in terms of the socio-economic dimension, education, with their children, etc.)?

- Identify the resources available to refugees and measure the availability of services offered in French and access thereto. To what extent does the Winnipeg OLMC serve as a resource and community of belonging for French-speaking refugees?

- Understand how the status of refugees influences their dealings with the agencies and networks of the Francophone community. How are the links and partnerships between refugees and Francophone and Anglophone reception-settlement agencies forged?

- Identify the roles that the Francophone communities of Winnipeg and St. Boniface play in welcoming and supporting refugees.

- Assess the coherence and relevance of the policies and programs of the three levels of government as well as community initiatives benefiting French-speaking refugees.

Methodological considerations

We have used a multi-pronged methodology. We therefore feel it appropriate to identify them in terms of steps and operations.

- The first step of our survey was to obtain an ethics certificate, in accordance with the Université de Saint-Boniface policy on research involving human subjects. This certificate enabled us to interview the participants in our survey.

- Prior to field work and analysis, we compiled existing qualitative and quantitative data to describe the socio-demographic profile of French-speaking refugees. To this end, we identified these refugees by their country of origin, how they were assisted (public or private), their year of arrival, sex, age, marital status, labour force status, their place of settlement and any other available information (see the socio-demographic data sheet in Appendix B)

- We then conducted ethnographic research using a qualitative data collection and analysis approach. By giving voice to Francophone refugees and those who work with them through one-on-one interviews and group discussions, we believe that we have achieved the objectives that we have set out above.

- Location: We met project requirements by working in the OLMC of Winnipeg and more particularly St. Boniface, which has the largest number of Francophone immigrants, while relying on socio-demographic information.

- Population of study: The population is made up of French-speaking refugees and the practitioners who serve them and facilitate their settlement and integration. First, the Francophone refugees among the immigrant population had to be identified. We then adopted the typical sampling technique, which allowed us to draw an accurate picture of the settlement and integration of these French-speaking refugees in St. Boniface and Winnipeg and to understand how the characteristics of the various groups of French-speaking refugees and their backgrounds had an influence.

- After profiling refugee immigrants, we identified agencies, groups (including sponsorship groups) and networks that could be a resource for refugee settlement and integration. Thus, within the agencies, we started by identifying and consulting Francophone practitioners (with the CDEM, AF and DSFM, for example) that facilitate settlement and integration, as well as the people in charge of resources available to refugees, to learn about the availability of and access to services in French.

- Similarly, we found it relevant to consult with Anglophone practitioners supporting refugees in Winnipeg, such as IRCOM or the Manitoba Start program, which is provided in partnership with non-profit agencies and is a nationally recognized best practice in welcoming newcomers, preparing them for the job market and providing them help in finding a job. We should also point out that some refugees are supported and assisted by community or professional associations outside the RIF, such as the CAAM, which played an important role in the reception and settlement of Syrian refugees in 2015-2016, and the MIA. We asked for input from the leaders of this type of agency that is active in this area as well as from the employers of Francophone refugees to get a more complete picture of the settlement and integration process of French-speaking refugees. In this final report, we have linked data from interviews and focus groups.

- Data collection tools: We used one-on-one interviews and group discussions. We conducted 30 one-on-one interviews with refugees chosen to reflect their diversity in terms of sex, age, country of origin and other relevant variables. Thus, according to the criteria that we have selected, our sample is composed of approximately 50% women and 50% men, between the ages of 18 and 30 (40%) and between the ages of 30 and 50 (60%). We also targeted people with children (75%) and others without (25%). In terms of country of origin, the sample is faithful to the population of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg in that Congolese refugees are prominent in our sample. We always strove for a sample that reflected these intersecting characteristics and the full diversity in the people we met and their experiences. We used an interview guide that tracks the migration trajectory, settlement and integration of these refugees. During these interviews, the participants–to whom we gave fictitious names–were given the opportunity to talk about the key moments and milestones in their immigration process (e.g. leaving home, being selected by Canada, arrival, starting the francization process, studies, employment, etc.), the positive and negative events for them and their families (diploma, arrival of other family members, moving, etc.), dealings with service providers, agencies and networks (health, social, education, employment) of the Francophone host community (interview template in Appendix B).

- We identified 17 organizations and groups in three different categories where practitioners work facilitating the settlement and integration of refugees. First, there are agencies that are part of the RIF, then Anglophone practitioners supporting refugees in Winnipeg, and lastly community or professional associations and employers outside the Anglophone and Francophone immigration networks. We conducted ten one-on-one interviews with RIF practitioners, five one-on-one interviews with key practitioners in Anglophone organizations, and two interviews with the leaders of community and professional associations and employers. These interviews focused on the relationships between agencies and refugees, and their accessibility and support strategies. These interviews also made it possible to identify the impact of private sponsorship and volunteering on the reception and integration of refugees in the OLMC. In addition to these one-on-one interviews, we analyzed the grey literature related to refugees produced by these various practitioners (interview template in Appendix B)

- We also used group discussions with these refugee immigrants to gain a better understanding of their behaviour and attitudes. We thereby gained a deeper understanding of the answers given in the one-on-one interviews. This tool therefore allowed us to understand the social behaviours adopted by our respondents to facilitate their integration. (Facilitator’s guide for group discussions in Appendix C).

- Recruitment of participants: Participants were recruited through a contact person in the Francophone and Anglophone organizations providing services to newcomers in Winnipeg, who sent the letter of invitation in writing or by electronic means to refugees, members and practitioners in their organization. This contact person was not the immediate supervisor of these practitioners, so that a hierarchical relationship of power or authority would not influence their participation in this study.

- Data constitution and analysis: Once the interviews were completed, we transcribed them verbatim. We encoded these transcripts with Nvivo speech analysis software. This encoding was done in accordance with the categories and codes stemming from the IRCC request for proposals itself; the codes and categories were in turn modified according to what the participants told us during their interview. This encoding gave us the data on which chapters 2 and 3 of our study are based.

- Limitations and biases of the study: These take different forms. First, the language of the refugees participating in our study posed a methodological challenge and is undeniably a significant limitation of this report. Although they chose French as their settlement and integration language, many refugees had difficulties expressing themselves in French during the interviews. This may be due to several factors. We can assume that their knowledge of French was tested by their migration experience, especially if they went through traumatic events in that language, if they lived in camps or transition countries where French was of little or no use, or if there was a lengthy delay between the time they left their home country and their actual entry into Canada. Of course this limitation is not attributable to refugees alone: it results from the very dynamics of the interview process. Different accents may cause communication problems between the interviewer and the interviewee. We have tried to minimize these problems by having all members of the team read the interview transcripts. Another limitation of our survey is due to the representativeness of our sample. This is actually a double limitation. First, although we strove to have a sample that was as representative as possible of the French-speaking refugee community in Winnipeg, it is clear that refugees who did not seek help from agencies working with newcomers are under-represented in our study. In fact, participants were recruited largely thanks to two such agencies. If these agencies do not know refugees who chose not to seek their help (for any number of reasons), then our sample is unlikely to include these refugees. However, this limitation must be put into perspective since very few French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg have slipped through the cracks of the institutional net. Second, although refugees who did not seek the help of agencies serving them are under-represented, there is a good chance that refugees living in St. Boniface will be over-represented in our study. One of the partners who assisted us with the recruitment of our refugee participants is in fact located in St. Boniface. This agency serves all newcomers in Winnipeg, but those living in St. Boniface are over-represented in its pool of recipients. Here too, this limitation must be put into perspective since the IRCC request for proposals placed the St. Boniface ward front and centre in the development of theme 3 on the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg. A last bias or limitation of our study lies in the very nature of the methodological approach that we have adopted. There is no question that the semi-structured interviews and the group discussions by which we obtained our “data” involve a degree of subjectivity. This subjectivity stems, on the one hand, from the participants who often had to call upon their memory–which can fail or distort–to answer our questions, or who may have been tempted–consciously or unconsciously–to alter the truth to make themselves appear in a better light. Subjectivity bias also originates with the researchers themselves. We know that the relationship of the subject to the object, in any scholarly enterprise, is never immediate or direct. It is mediated in particular by the mind of the researcher–his or her methodological training, values, and experiences–which determines how he or she apprehends his or her object. In concrete terms, this mediation is apparent in the selection and formulation of the questions we asked the participants, and those that we did not. However, this bias also needs to be put into perspective. While the researcher’s involvement in the survey process inevitably introduces subjectivity, it is also a sine qua non of the survey itself. Indeed, without a researcher wanting to learn something, knowledge is impossible. The desire to learn, which is inevitably driven by the researcher’s subjectivity, is what makes knowledge possible. The biases introduced by the qualitative methodology have been corrected, at least in part, by adding socio-demographic data sheets using quantitative data to our methodological framework. Lastly, it should be noted that the very fact that there were multiple one-on-one interviews and that two focus groups were added also helped to reduce the bias stemming from one-on-one interviews.

The report has three chapters. In this first chapter, the refugees we interviewed speak about their background, settlement and integration. This chapter is divided into seven sections: a profile of the French-speaking refugees interviewed (1.1); their trajectories (1.2); government policies and programs related to refugees (1.3); their integration (1.4); their challenges (1.5); the services they received (1.6); and their evaluation of these services (1.7). In the second chapter, practitioners working with agencies serving the newcomers we interviewed speak about the services they provide to French-speaking refugees. This chapter is divided into five sections: Section 2.1 profiles the agencies serving newcomers where the practitioners we interviewed work. Section 2.2 addresses the challenges that these agencies face with respect to refugees. Section 2.3 discusses the services provided by these agencies. Sections 2.4 and 2.5 look at the evaluation, by the practitioners from the agencies interviewed, of refugee settlement and integration services and programs. Chapter 3 analyzes and discusses the findings presented in the two previous chapters in light of the main issue identified. The settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg are examined through six variables based on their shortcomings, the issues they raise and the relevant recommendations: housing (3.1), employment and training (3.2), education (3.3), language acquisition (3.4), health (3.5) and social integration (3.6). Our conclusion will be in two parts. The first part highlights best practices in the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg. The second part opens with some possible directions that future research can take.

Chapter 1 Research results: The voice of refugees

1.1 Profile of refugees

This is where will we profile, using various elements, the 41 French-speaking refugees interviewed in the study. The first element to be emphasized is the representativeness of our sample. The sample reflects the reference population in terms of gender distribution, age distribution and country of origin. We have respected the structure of the total population of French-speaking refugees living in Winnipeg and St. Boniface since 2006. Demographic aspects are the second element of the sociodemographic profile of the subjects in our study. As in the reference population, nearly 29% of participants (12) are under 30 years of age, nearly 59% (24 participants) are between the ages of 30 and 60, and nearly 12% (5 participants) are over 60 years old. In terms of gender distribution, 46% (19 individuals) of participants are female and 54% (22 individuals) are male. It should be noted that the social and economic integration of this generally young population has raised interesting questions and issues for the study.

Our study also reveals that more than one in three people are single (35%), that more than half (52%) of the study participants are married or in common-law relationships and that only 13% are widowed or separated. The marital status of the sample reflects the presence of families. Nearly 3 out of 4 participants have children (73%): 7 have 1–2 children (17%), 17 have 3–6 children (41%) and 6 have more than 7 children (15%). At home, 56% of the interviewees speak French in combination with another mother tongue and 25% speak both Canada’s official languages in combination with another mother tongue.

Knowing that the French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg come from French-speaking Africa, we interviewed 30 refugees (73%) from the Democratic Republic of Congo, 3 from Côte d’Ivoire (7.3%), 3 from Chad (7.3%), 3 from Burundi (7.3%), 1 from Angola (2.4%) and 1 from the Central African Republic (2.4%). It is clear that many of the French-speaking refugees in Manitoba come from the Democratic Republic of Congo. These refugees are fleeing the ongoing civil war that began in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide.

Our study also shows that these refugees had to wait for varying periods of time to enter Canada. Nearly 1 out of 3 interviewees waited more than ten years as a refugee in another country under the responsibility of UNHCR before obtaining permanent resident status in Canada; 1 out of 4 interviewees waited more than two years, but less than ten; and 1 out of 7 interviewees waited less than two years. This variable waiting period between obtaining refugee status and actual entry into Canada determines their settlement and integration experience, as we will see later in the study.

With regard to housing, it should be noted that nearly half of our participants occupied social housing, and at the time of the interviews 95% of the participants were still renting. This is explained by the precariousness of their situation in the job market. We note that 41% of the interviewees are unemployed, 30% are employees, 5% are self-employed or independent, and 7% are students. This precariousness is also evident in the fact that most are doing general work, food service, cleaning, and sales. Furthermore, 3 out of 4 interviewees expressed their intention to go back to school to increase their employability. It should be noted in this regard that 50% say that their diploma is not recognized in Canada, while nearly 30% have a university education, 54% have completed secondary school, and 15% have attended elementary school. Lastly, it should be noted that more than half of our respondents confirmed that their credentials are not recognized in Canada and only 1 in 3 respondents confirmed that their credentials were recognized. Finally, in geographic terms, our study reveals that the majority of the interviewees settled in the city centre and in St. Boniface (see map in Appendix D).

1.2 Trajectories of refugees

In this section, we will describe the trajectories of refugees up until the time they arrived in Canada and obtained permanent resident status. The trajectory on Canadian soil (integration trajectory) will be analyzed from section 1.3 onward.

1.2.1 The journey up to actual entry into Canada

It is relevant to focus on the trajectories of refugees before they arrived in Canada and obtained permanent resident status. The experience of French-speaking refugees before their arrival in Canada is not without impact on their settlement and integration and is even determinative. The journey refugees make before they arrive in Canada is not an easy one. The period of time between the quite often difficult decision to leave their country of origin and their entry into Canada was for most survey participants a long and stressful one. This period is certainly difficult, but one that has been formative for many of our survey participants. The experiences during this transitional phase undoubtedly had an impact on their path after arriving in Canada, hence the interest in giving it some consideration.

This trajectory before obtaining permanent resident status can be examined through five variables: (1) the factors or circumstances surrounding departure from the country of origin; (2) the waiting period between obtaining refugee status and their actual arrival in Canada; (3) the type of journey that refugees made during this transitional period; (4) their knowledge of Canada or lack thereof; (5) the type of sponsorship.

The factors or circumstances that led our survey participants to leave their country of origin are diverse. We have no way of comprehensively analyzing this question. We simply identified a few factors and circumstances that led some of our study participants to seek refuge outside their country of origin. There were essentially two that are interrelated: the violence of war and political reasons. We should note, from the outset, that these factors explain why Winnipeg’s French-speaking refugees are mainly Congolese who fled the civil war that has raged in the Congo since the mid-1990s: [translation] “In Congo we have suffered cruelly from wars.... And, in this case, we had no assurances of safety or survival because we do not know where it will come from or when.”(Odile) But the Congo is not the only country of origin. Some participants come from Liberia (Gaston) and others from Chad (Norbert).

Intimately linked to the factor of war, political reasons were also invoked by our study participants to explain why they left their country of origin.

[translation] I was a human rights advocate when I was at university. ... I was forced to leave the Congo because these people [rebels] came after me. In my native village, the tribal chief gave in to the rebels. And since they were the ones who already controlled everything, then they really had to silence all the people who had already been talking about human rights issues. (Quentin)

With regard to the wait time, it should be noted that 27% (11) of the refugees interviewed waited less than five years, 20% (8) between five and less than ten years, 33% (14) ten years or more, and 20% (8) of the refugees participating in the study were unable to provide us with specific information on obtaining their refugee status. This is probably due to psychological reasons: they may have wanted to repress this traumatic experience. It is significant that while not all of our participants remembered the date they acquired refugee status from the United Nations, all of them could cite the exact day, month and year of their entry into Canada, or in other words when they became permanent residents. The exactness of their answers shows us the importance they attach to that new status. The actual date of entry is in fact a confirmation of their permanent resident status and is, therefore, a momentous milestone in their trajectory.

During this transitional period of varying durations, 41% of the participants came through UNHCR camps. Their migratory experience was marked by the various problems they experienced in these camps, including, for example, problems with violence and rape, access to food and separation of families. Often times, refugees fled violence in their country of origin only to find it in a different form elsewhere.

[translation] ... a woman coming for her registration number who does not have her husband will first be sexually exploited by the interpreter or the local authority so that she can now get access ... to that number. ...there were also clear violations of human rights, especially those of refugees. (Pier)

[translation] I come from a family of 12, but when we got to the camp, there were only four of us. And we went perhaps 2-3 years without hearing from anyone. (Ursule)

In addition, 22% of our survey participants came through transit countries instead of UNHCR refugee camps. That did not make their journey any easier. Many of our participants fled war in their country of origin only to find it in those transit countries. [translation] “So back there, I wasn’t in a refugee camp because there weren’t any in Yaoundé. So, you rent a house in the neighbourhood. Everyone does what they need to do to survive.” (Irène) Some of these participants transited through the United States and then crossed the Canadian border to claim refugee protection here.

The fourth variable in looking at the journey of refugees prior to their arrival in Canada has to do with the representations and perceptions they have of Canada, and Winnipeg in particular, where, we must remember, none of them chose or planned to come. In fact, many of them only learned that they would be settling in Winnipeg the day before they arrived, if not the very same day. What, if anything, do they know of Canada? Do they know anyone in Winnipeg? It appears that participants in general had only a rudimentary knowledge of Canada prior to their arrival. For many, being in Canada came as a “surprise” (Fernand). Fourteen of the participants admitted that they knew nothing at all about Canada. Needless to say, this relative unfamiliarity with Canada and Winnipeg influenced their settlement and integration. It is very difficult to settle and integrate in a country and a city we know nothing about and where we know no one: [translation] “It was the first time I had heard the name ‘Winnipeg.’ We had heard of Canada, we had heard of Toronto and Montreal, but Winnipeg...what’s that?” (Ursula).

The last prism through which we wish to address the trajectory of refugees is their sponsorship. It should be noted that 83% of the participants were sponsored: 46% were sponsored by the government and 37% by agencies, individuals and private groups. The remaining 17% of our interviewees were not sponsored. It is important to focus our attention on this variable, as it influences the refugee’s integration experience, as we will see later. We should also note that the refugees participating in our study did not bring up problems related to the type of sponsorship per se; however, as we will see, some of the problems raised are more persistent in one sponsorship category than the other.

1.2.2 Problems and difficulties on arrival

We will close this section on the journey of refugees before they actually enter Canada and highlight some of the problems and difficulties they encountered upon their arrival. Most of the interviewees experienced–unsurprisingly–a climate shock regardless of what time of year they arrived. Obviously those arriving in the fall or winter were so shocked by Winnipeg’s bone-chilling temperatures that some would have refused to come here had they known about the weather that awaited them. For others, weather would be their first [translation] “challenge” (William) to settlement in Canada: [translation] “When we arrived, I was stressed right at the airport. Because it was cold. ...there was fog. Everything was white. ...I just told my children that if I knew the country was like that, I would not have been able to come. I was stressed right there.” (Élodie) But there is more to climate shock than just the cold, there is the shortness of the days as well: [translation] “I would not say that it was the climate because we had the good fortune to come in the summertime...it was something like ten o’clock at night and it was still light outside; afterwards when winter set in...we said no, no, no.” (Laurence)

In short, the trajectory of refugees from the time they left their country of origin and the moment they arrived in Canada is a difficult journey during which they have had to face challenges and hardship. This experience, as we will see in the next section, has an impact on the refugee settlement and integration process in Winnipeg. Some of the problems encountered on arrival in Canada persist, as we will see in the following sections.

1.3 Appraisal of government policies and programs in light of settlement experiences

The settlement experience of French-speaking refugees cannot be understood without at least a passing consideration of the policies and programs supporting the agencies providing these services. Canadian immigration policies, and more specifically refugee policies, are in fact among the most generous in the world. It is often said that more than 60% of refugee claims are accepted by Canadian authorities, compared to less than 30% in other countries.

All three levels of government (federal, provincial and municipal) have policies and programs for receiving, settling and integrating newcomers. These programs in Manitoba are distinctive in that they must meet a fundamental requirement: the preservation and promotion of the minority Francophone community. To that end, the three levels of government, as well as community agencies, work hand in hand to ensure these programs are successful. Manitoba appears to be a destination of choice for refugees, as it appears to be the only place in Canada, or even in the world, where 30% of immigrants are refugees. It is therefore worthwhile to hear what the study participants had to say about these policies and programs.

Their settlement experiences are diverse. The programs refugees use illustrate this diversity as far as the strengths and weaknesses of programs are concerned.

1.3.1 Government programs: Strengths

The interviews with newcomers and practitioners enabled us to identify a number of strengths and weaknesses of the various programs. In terms of strengths, for example, seven participants said they were pleased with programs such as orientation, financial assistance and medical services. This is what one of the participants we called Kevin said about orientation:

[translation] I think those who come with the government are in a good position where that is concerned. Because the community that starts with them first, like the AF, tries to orient them and give them tips that can encourage them to go into the community. But for us who are, privately [sponsored] for example, I will be with my sister, for example. She will take me to the areas [she] knows. It won’t be the community.

They recognize that there are services that help them acquire basic knowledge essential for everyday life (how to take the bus, look for housing, arrange for phone service, shop, etc.) but they point out that the GARs among them have a leg up. One participant that we called Marthe said this:

[translation] Because for the ones sponsored by the government, I learned that community homes like Accueil francophone provide a lot of help with orientation and how to get settled. They really support them throughout the whole time. But for us, the government is distant. It’s just the person who came with you.

All study participants acknowledged and appreciated the financial, medical and social assistance provided by the government. However, they said that it is unfortunate that the financial assistance abruptly stops after one year. Yet even so, they remain deeply grateful to the government, especially since most come from countries where social assistance is unheard of. Another participant, Robert, said: [translation] “The government has been sending me money every month thus far; that is great and I am very pleased with that.” In the group interviews that we conducted, here is what one participant had to say that summed up the general opinion of all the participants: [translation] “We have financial, medical and social assistance. We were still supported by the government. But a year later, it’s just the province that is starting to support us. Now, I would say that this is the government’s logical continuation...we continue to be supported, and truly, I think that’s pretty good” (Gaston).

1.3.2 Government programs: Weaknesses

The weaknesses of the programs were strongly emphasized by 10 participants. In fact, some participants talked about these government programs’ lack of direction. They add that GARs are left on their own once the twelve-month period has passed. Suddenly, they have to fend for themselves. A participant that we called Quentin gave an excellent summary of the opinion shared by all:

[translation] Those who are privately sponsored, I think they have more advantages than those sponsored by the government... I see that they are oriented, they are shown everything. So they share all the problems they encounter with them. They share everything with them. ... It is their partner who shows them what they are going to do.

Financial resources seem insufficient, given the magnitude of the problems. There is therefore some discrimination, a certain inequality, with regard to access to services (rent, various allowances). One of the participants said the following:

[translation] I was paying more than the ones who were sponsored ... I am supported by the government, meaning the government gives you money, but it doesn’t do the math, it gives you a certain amount, these are your needs, but you have to pay your rent but why is that? So I was paying at least $200 more than the others. (Laurence)

In addition, the participants found that certain government measures undermine the value they place on searching for work. To be sure, the ones in the labour force found these measures to be a disincentive to working. One participant, Robert, says: [translation] “Work is a good thing, but you find a job paying $1500, for example, if you make 1500, the province takes away $1500. You are left with your $1500. You see what I mean. With $1500, the house and who knows what else, there’s nothing left.”

Unequal access to services and citizenship also appears to be a bone of contention in the integration process. Access to services and citizenship is shaped by which category of immigrant the refugee is in. One of the participants (Valérie) shed some light on the issue:

[translation] When it comes to immigration, we are not all equal. Because, for example, when a black man comes here from the Congo, here meaning Winnipeg specifically.... To become a citizen, he must spend five years in Canada. But when a Syrian comes here, he is offered many services straight away and becomes a citizen in a few short years, without living here for the full five.... They are helped to find work straight away.

One other complaint was the lack of a job search service. Participants would have preferred to have support when searching for employment until they find it. Here are Kevin’s thoughts:

If you were sponsored by a community or by some friend, by religion, it can be different because they know. They can find job. Because if someone is friend with someone to bring here, he knows if the guy could come, he can find job for him. So we will come with the government, they don’t care. After one year, they don’t care. Nobody comes. Like if I am here I know that oh if I sponsor someone, I have to look for a job for them.

Participants compared government sponsorship with private sponsorship and reported that they have financial independence with the first. They say that everything is fine, at least for a year, under government sponsorship. But they point out that, after one year, refugees are left on their own and have to fend for themselves. One of the participants, Gisèle, said:

[translation] There is a very big difference because the ones who are sponsored by the government, they are supported by the government right when they arrive, they are given everything they need, and those of us who are sponsored by a private individual, we are dependent on the individual. After all, the individual does not have enough money to meet all your needs.

One participant, Laurence, added:

[translation] As soon as you arrive with the federal government, you are given money to start over, so you have to buy things for the household. That isn’t the case for the sponsored ones. They come with the person who sponsored them there for a year, so he must immediately—, maybe he arrives today and then tomorrow he has to start working, but that’s not the case for us. We were lucky, we had time to rest a while, see things how things go and make decisions; I had time to make decisions.

The security aspect also favours GARs. In terms of looking for housing and the administrative procedures, participants generally share the idea that the GARs among them are better off, at least the first year. One participant, Yvonne, confirms this: [translation] “All I know, when you come through the government, the roof over your head is secure; your papers are secure. You have security; you know that as long as you are sponsored by the government, it will see to it that you are taken care of here.”

The study shows that program and service recipients are by turns satisfied and unsatisfied. First, they are satisfied because these programs are in place and they benefit from them. They have access to various resettlement programs (RAP, IFHP, housing assistance program, financial assistance program, etc.) However, they are frustrated because not everyone has equal access to these different programs. In fact, GARs seem to have more rights than refugees sponsored privately (by individuals, groups, or religious communities). Furthermore, educational reintegration programs, at least in the French-speaking world, do not seem to take into account the different levels of orientation for individuals.

1.4 Integration of refugees in Francophone communities

In our study of French-speaking refugees in Winnipeg and St. Boniface, we have chosen the term integration to be the result of an active process in which at least two interdependent dimensions interact, namely the economic dimension and the social and cultural dimension. In this sense, integration requires the involvement of all parties involved, including the refugees themselves. In this section, we present the socio-cultural dimension of integration (1.4.1) that makes it easier for local communities to adapt to the presence of refugees and also facilitates the lives of refugees among the host population. The economic dimension of integration (1.4.2) shows how integrated refugees are in the job market and, consequently, the extent to which they participate in the host country’s economy.

1.4.1 The socio-cultural integration of French-speaking refugees

The concept of integrating a newcomer into his or her host community can be summed up by the interactions between them, whereby a sense of belonging and identification with community values is formed. In other words, refugees can be considered integrated if they share the values and norms of the community, and especially if they feel accepted in their new environment.

1.4.1.1 Role of the host community

To understand the role of the community, we asked participants whether they thought that they were integrated into the host community. Approximately 50% of participants said that they feel integrated into their host community. They said that they in fact have been well received by the community and have been included in many community activities. Stéphanie conveyed this sentiment well:

[translation] It was very easy for me to feel comfortable. All the people that I approached were nice to me, the people whom I pass in the street, they smiled, or if I couldn’t see a smile, there would at least be a hint of a smile. Some gave a wide smile, others seemed to smile automatically, but I did not sense any hostility. So, I feel right at home here.

To the same question, Gisèle answered: [translation] “Oh, yes. I am integrated, because if we were brought directly to an environment where people spoke only English it would be hard, but we were brought to an environment where people speak French. They look English, but you can still talk to them in French. So it’s good from that point of view.”

Others describe integration as a difficult process. Indeed, many recounted the financial difficulties they had for a certain period after they arrived. This was usually due to the fact that they had not yet found a job and were not able to make ends meet on the allowance they received from the government. From this allowance, refugees must pay rent, buy food and also think about reimbursing the amount paid by the federal government for their airfare. In this regard, PAR3 told us, [translation] “After a while, they will send you letters about starting to pay back the money. And I’m not working, I have no idea, what can I do?”

The obstacle to Fernand’s integration is language, pure and simple. He says: [translation] “I do not socialize with people because I do not speak English. That’s my problem. I speak French and I cannot interact with someone who speaks English. That cannot work; that’s why. If I spoke English, I would have friends, but since I do not speak English I am alone.” In other words, as we will see in the section on challenges, refugees’ lack of knowledge of English is a barrier to their socio-economic integration.

Ultimately, the role of the host community is to develop and provide services to facilitate refugee integration. As we will see, numerous services related to health care, settlement assistance, education, social services have been created to facilitate refugees’ integration in the community.

1.4.1.2 Role of religious communities

Approximately one quarter of study participants stressed the prominent role played by religious institutions. According to some participants, religious groups are central to their integration into the host community. The church is a meeting and gathering place for newcomers and members of ethnocultural associations that are already well-established in Francophone communities. Networks of acquaintances, friends and multi ethnic community members through the church provide material and psychological support to refugees. PAR2 told us: [translation] “I go to church and that’s where we sometimes meet many other people from my community or other communities who speak French. Going to church helped me a lot at first because I could meet other people, and also starting classes here at the university.” Claude was in agreement: [translation] “I’ve integrated, so between the church and the committee, I have friends, a lot of friends. It’s thanks to the friends I had, going from there to here, so even for getting around here, I didn’t have to go out. I have friends who were going to buy things for me, do my shopping and then give them to me.”

It should be noted that the church, as an institution, provides material resources and services to refugees. The church’s concrete actions play a key role in the social integration of newcomers. To that effect, one participant, Marthe, told us: [translation] “the church puts on activities...we play sports every Friday.” Alfred, meanwhile, said that his integration went more smoothly, because [translation] “the church did a lot of work with us; they visited us three to four times per week. I really have to thank them for that.”

The church is a meeting and gathering place for newcomers and members of ethnocultural associations that are already well-established in Francophone communities. The church has also proved to be a meeting place for refugees.

1.4.1.3 Role of communities and ethnocultural associations

Some participants told us they were integrated into their ethnic communities of origin through their ethnocultural associations. They also emphasized how important these associations were to their integration into the host community. Joceline said that participating in the activities of her association helps her a lot because [translation] “I don’t feel alone, I feel at home: because we speak the same languages, I feel at home with the others.” Berthe answered by telling us: [translation] “Yes, I am integrated into the community here. Because the Congolese community knows me, knows that I’m here. Sometimes, when they hold meetings, they ask me to come; it does me good to mingle with the others there.” Laurence told us about the crucial role some members of his community had in his integration:

[translation] When I arrived, the phone would ring, people would say, “Oh, do you know the so and so family? They came from Burundi—do you know them? Indeed we do!” So they were quick to come pick me up and take me to the people that I already knew from back home. Truly, they gave us a lot of support because we didn’t have a car, no means of transportation; how were we going to get around during the winter, get our groceries, I don’t know. In any case, they were there for us whenever we needed to go someplace.

Some participants lamented the fact that there was no ethnocultural community from their country of origin. Norbert told us: [translation] “There is no one here from Chad. There are no Chadians and I know only two Chadians. One who came here about 10 years ago. The other, 7 years ago.” On the other hand, others have voluntarily chosen not to integrate into their ethnocultural community. Alfred says that he has not received help from his community: [translation] “No, no, no. I’m sorry. The community just wants something from you.” And others have chosen to distance themselves from their community of origin in order to learn more about their host community: [translation] “I don’t want this community to be my be all and end all. We get together, we become acquainted, but I prefer to have a larger social circle.” (William). Ultimately, the statements above show us how important community networks are for the integration of refugees.

1.4.2 The socio-cultural integration of French-speaking refugees

This subsection deals with the concept of employment as a factor in the integration of newcomers. The vast majority of participants in our survey (42.5%) stated that they are unemployed. We asked them if their job search was satisfactory. Gisèle told us: [translation] “I can say that it hasn’t been so far. Because I haven’t worked at all since I’ve been here, but I’m trying to find a job and I haven’t found one yet.” Quentin echoed those sentiments, saying: [translation] “I can’t find a job except in construction maybe. But for work and my skills, it is a bit difficult. Because I’m told no, IT is a bit, it’s a bit advanced here.” The unemployed participants pointed out that it is sometimes very difficult to find a job due in part to poor English and a lack of work experience in certain professional fields. Employment, as we know, is an important factor in the integration of refugees, because it allows them to have a good quality of life and ultimately to develop a true sense of belonging to the host community.

Our data also reveals that eleven participants (27.5%) state that they have a job and two others say they work for themselves: [translation] “I own my business; I’m good at filming and I know how to edit video [so] I said to myself ‘OK, I'm going to create that type of company.’ I’ve done a lot of weddings, social documentaries, fiction films, in any case to really penetrate the community in the literal sense of the word.” (Théodore). Two participants (5%) preferred to go back to school, either on the advice of others or of their own volition. Laurence told us: [translation] “I’ve been told, you need training...you cannot start a business here like we would at home.” As for Gisèle, she said: [translation] “I am in school, and when I’m finished, there might be something in store for me here, maybe I will find a good job so I can support myself.”

However, despite the important role employment plays in the successful settlement of refugees, it should be pointed out that the overwhelming majority of participants highlighted the importance of education in the integration process. In fact, 72.5% of the interviewees told us that they want to go back to school, regardless of whether they were employed or unemployed. On this subject, William told us: [translation] “I haven’t started looking for a job yet, because I was advised that as soon as my English improves, I should go to university here to study.” As for Yvonne, she would like to study early childhood education: [translation] “I would like to continue studying child care. To open a daycare.”

The fact is that, although approximately half of the participants feel integrated, and despite the important role of religious institutions and ethnocultural communities, participants nonetheless said that they face many social, economic and cultural challenges.

1.5 Challenges to the settlement and integration of French-speaking refugees

Settlement of French-speaking refugees in a minority setting in Winnipeg is not without its challenges. This section of the report summarizes some of the statements made about these challenges as they were perceived by the refugees interviewed for this study. There are 4 parts. The first describes the challenges refugees in Winnipeg face when settling and resettling. The second presents education-related challenges. The third deals with the recognition of credentials and the fourth presents challenges related to official languages.

1.5.1 Settlement challenges

Factors such as age, employment, and financial management are very important in the refugee settlement process. This part discusses age-related challenges. It relates the meaning that these refugees give to their settlement and resettlement, to finding employment, and to their relationship to money to meet their many needs related to the management of their income.

Refugee age

The age issue is an important factor in the process of immigrant settlement and integration. Refugees of all ages face the same challenge when it comes to finding a job so that they can look after themselves as quickly as possible. Seniors, who usually accompany their families, find themselves in a situation where they are often forced to stay at home, since they are past working age. As this respondent attested: [translation] “Seniors have a hard time finding work and living in our society” (Irène). Since they cannot work, they are often confined to their homes. Depending on the type of dwelling (house, apartment or condo), they may feel isolated and bored. This respondent explained: [translation] “There is no courtyard here, you are in the house, you are shut in, you might go out to go grocery shopping or visit someone. You can’t do activities; how can you teach others? That’s the problem” (Élodie).

However, despite a lack of fluency in English that complicates the plight of these seniors, some attempt to cope with this challenge by trying to combat this isolation. The best way that they have found is to draw on the help and support of some agencies that mentor newly arrived immigrants and refugees. One respondent stated:

[translation] The problem is that you must not stay at home. Because when you stay at home, you start to brood. That’s why we have to create a group here...a seniors group. When you come [to the group], you talk and talk, you laugh, you go home, you can rest easy. Because if you only stayed at home, you could die. (Élodie)

The age of immigrants is therefore a key challenge in the integration process. At a certain age, learning something new is more difficult, especially if the immigrant finds him or herself in a completely different context and culture and if, on top of that, he or she does not speak the language fluently: [translation] “You see, learning a language when you are a senior is not easy” (Élodie).

Settlement and resettlement

As soon as they arrive, most refugees are welcomed by agencies mandated to assist with their reception. These agencies help them in their temporary settlement or resettlement in Winnipeg, while they learn to look after themselves in the city. [translation] “I would still stay that the people at AF helped me get on my feet when I arrived. To help me manage. Since I live alone, my husband is not here. I don’t have a job; I must live within my means. (Gertrude)

Successful settlement starts with adequate and safe housing for the family. This housing can be a house or an apartment and the cost of the housing unit may vary according to the size of the family. Large apartments for large families will be more expensive. [translation] “But someone got a house for me that costs $885. I have to pay for that house; I pay $80 for electricity.” (Gertrude)

Discrimination

Whether during one-on-one interviews or in group discussions, participants reported enduring situations that they said were discriminatory. Experiencing discrimination, racial discrimination in particular, makes it more difficult for any newcomer to settle and integrate. In this sense, discrimination is certainly a challenge to the settlement of newcomers. We therefore believe that practitioners must take this into account.

From the interviews, it was revealed that discrimination can be experienced directly or indirectly. Direct discrimination is part of the everyday lives of refugees. They encounter discrimination in different places, for example on public transportation, in the workplace and in the neighbourhood. It can take many forms: discrimination based on the colour of skin (black/white) or based on origin (First Nations versus newcomers). For example, Élodie says: [translation] “Sometimes there will be a white man sitting in the bus. You go to sit next to him; he gets up because you are black. He gets up, even if there are no other seats, he would rather stand ... There are people who do not like us, because we are black....” Élodie experienced similar discrimination in a café. After sitting at a table where a white man was already sitting, he said, according to Élodie: [translation] “fuck, you couldn’t find a seat elsewhere; did you have to sit here?” In the same vein, Daniel reports that during a flight: [translation] “A white woman didn’t want me to sit next to her. She started staring at me. She made it clear that she cannot sit next to me.” Direct discrimination can also take place in the neighborhood. Stéphanie explained: [translation] “Yes, there is racism among the people in the neighborhood.” Participants also reported origin-based discrimination, meaning discrimination between newcomers and First Nations residents and between older and newer residents. For example, Élodie says that an aboriginal woman asked her [translation] “what do you want in our homeland, what are you looking for here, couldn’t you stay home?”

Indirect discrimination, in contrast, refers to discrimination perceived by participants. This is systemic discrimination. Its sources are language, the job market and the migration system itself. Stéphanie told us that she did volunteer work in French at the Taché Seniors’ Centre. She laments the fact that this Francophone institution hires employees [translation] “who don’t speak one word of French” and gives them the chance to learn French. Stéphanie wonders why the reverse is not true, namely why the Centre does not hire Francophones and give them the chance to learn English: [translation] “This is so discriminatory! From a Francophone centre to boot! On this point, I don’t agree with the Manitoban government.” (Stéphanie)

Valérie felt discriminated against in the workplace. She felt that it was [translation] “like inequality and domination.” Furthermore, other participants addressed the discrimination issue in the process of integration itself. Participants said that they feel that refugees do not receive equal treatment. For example, Syrian refugees in particular are seen as benefiting from preferential treatment due to the speed at which their claims are said to be processed. This creates a sense of frustration and gives some newcomers the impression that there is a two-tier system in which some refugee claims are processed faster than others.

[translation] You tell people that you are helping them. When they get here, you start to pay for visas and then of course it could be understood, but when we arrived at the same time as the Syrians. Syrians do not pay for their visas; that’s discrimination right there. (Quentin)

In the face of repeated acts of direct or indirect discrimination, many participants came to view it as normal and eventually resigned themselves to it. As reflected by Élodie:

[translation] And afterwards, we say among ourselves “that’s the way life is.” We are in their country and if someone is going to be like that, you don’t put up a fuss. You mustn’t react. That’s right. Can we solve anything? Others have already been brainwashed. That the black man is not a human being. You can’t stop them from thinking that. Not everyone is like that, there are those who like us and those who don’t. Who are really, really, really racist. But there are others who even if they don’t like you, they still pretend they do. And in the end, you get used to it.

Employment

Once settled, the first challenge is finding a job to deal with other basic needs. However, finding a job is not an easy thing for immigrants, even though some of them may get lucky as soon as they arrive. Clarence said: [translation] “Two weeks after coming to Winnipeg, I started working. It’s the same job that I have now.” This testimony demonstrates that, with some luck, professional experience can help a refugee work and make a career in Manitoba’s job market. In reality, respondents mentioned the challenges of finding a job in Winnipeg. The majority of these immigrants spend a great deal of time looking for work. After several unsuccessful attempts, the discouragement is palpable, as shown by the language they use: [translation] “I can’t get a job; I have given out a lot of resumes, but no one has called me.” (Irène)

The problem is not only how difficult it is to find a job, it is also what kind of job it is and the number of hours spent working that creates challenges. In addition, it can sometimes be part-time work, often poorly paid: [translation] “it is not even 10% of what he was doing. And, all he has is four hours a week, or even two hours a week. So it depends.” (Rose) For this respondent, these part-time jobs reflect a lack of recognition of credentials and a way for employers to get around committing to offering a permanent job. [translation] “But if you’re given two hours, or four hours a week, it’s just to say, ok. We can’t say no, but we can’t abandon you, but hey, just stay there.” (Rose) Some respondents say that it is often difficult to do the work of their jobs. Such statements often come from seniors for whom this difficulty can be even more distressing, because their health may depend on it.

[translation] I worked in a hotel for just three months; it was hard. The work was really difficult: just housekeeping and making the beds. It was hard for me. I didn’t even have the energy to help the children with their homework. I came home very tired. I started at 6 a.m. and worked until 6:30 p.m. It was hard for me and then I quit. (Berthe)

[translation] Cleaning is not something that I can do. Because I have a bad hip. Even at home, my hip will start to bother me when I just pick up the broom to sweep. I have already had an x-ray at least three times. They found nothing. (Élodie)

However, beyond the difficulties of part-time work, it is job stability that interests our respondents the most. Having a stable and permanent job is a sign of integration. [translation] “I'm not stable yet! You need to find work to be stable. Here, you can say you are stable when you get a paycheque. He earns a salary to support himself.” (Valérie)

Respondents also recognize the deficit of job offers in French, especially in St. Boniface, and the situation frustrates them because it decreases their chances of being integrated into the Francophone minority. They are so aware of it that they make it clear to those taking classes at USB that they are less likely to be hired when they graduate. [translation] “We had to go to St. Boniface to further our studies; we are told that of course you can study there. But when you graduate you will not be hired. ... For example, we are being told us that if you study in French, you will not be hired because the language here is English. We speak French, but the language here is English.” (Quentin)

Indeed, becoming proficient in English, which is essential if they are to integrate into the Winnipeg job market, represents a difficulty for these Francophone refugees. It is also one of the factors that accentuate unemployment in this Francophone immigrant community in Winnipeg. Many of them are forced to go back to school to overcome this challenge. Others use their social networks in the community to get a job, as demonstrated by these two respondents:

[translation] To find that work, there were connections. Someone connected to me told me: “They are looking for workers there. So, if you’re interested, you can apply there.” I applied and that’s when I was lucky enough to be hired. (Valérie)

If you have community, you get a job. If you have friends, you get a job. But if you don’t know anyone, to get a job, only God can provide. (Kevin)