Statistical Portrait of the French-speaking Immigrant Population Outside Quebec (1991-2011)

Statistics Canada

Ottawa, June 2014

René Houle, Daniel Pereira and Jean-Pierre Corbeil

This project was funded by the Research and Evaluation Branch at Citizenship and Immigration Canada that receives funding from the Roadmap for Canada's Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration, Communities to support research on immigration in official language minority communities.

The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of Citizenship and Immigration Canada or the Government of Canada.

Ref. No.: R8-2014

Table of contents

- Summary

- Introduction

- 1. French-speaking immigrants living outside Quebec

- 2. Geographic origins of French-speaking immigrants

- 3. Age structure

- 4. Interprovincial migration

- 5. Linguistic behaviours at home and at work

- 6. Couples in which at least one partner is a francophone immigrant and the intergenerational transmission of language

- 7. Education and diplomas

- 8. Labour force participation

- 9. Conclusion

Summary

This report examines French-language immigration outside Quebec and its recent evolution, focusing on its numbers, its geographic distribution and its demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. This is an update of the analytical report published by Statistics Canada in 2010, with the financial support of Citizenship and Immigration Canada. This new version uses the most recent statistics on the subject, drawn from the 2011 National Household Survey.Footnote 1 As in the 2010 version, this statistical portrait of French-language immigration is primarily based on the concept of first official language spoken (FOLS), which has been increasingly used in recent years as a criterion of linguistic definition in studies on official-language minorities. The francophone immigrant population outside Quebec comprises two groups: those with only French as their first official language spoken (French FOLS immigrants) and those whose first official language spoken is both French and English (French-English FOLS immigrants).

The francophone immigrant population living outside Quebec is fairly small, both in absolute numbers and in relation to the number of French-speaking persons overall or the immigrant population as a whole. However, the relative weight of francophone immigrants within the French-speaking population as a whole has increased from 6.2% to 11.7% between 1991 and 2011, whereas their weight within the immigrant population varied more moderately, standing at 2% in 2011.

While the 2006 Census enumerated 60,900 immigrants with French as their FOLS in the provinces and territories excluding Quebec and 76,100 immigrants whose FOLS was both French and English, the 2011 National Household Survey found that within those provinces and territories, there were 74,470 French FOLS immigrants and 79,400 with a French-English FOLS.

It is worth noting that of the immigrants who were living in provinces and territories outside Quebec in 2011 and who had come to Canada between 2006 and the 2011 NHS, 18,450 had French as their FOLS and 17,600 were French-English FOLS. Of the recent immigrants enumerated in the 2006 Census, the corresponding numbers were 12,940 and 18,570 respectively.

As seen in the earlier version of this study, the majority—nearly 70%—of francophone immigrants outside Quebec are concentrated in Ontario. Two-thirds of French-speaking immigrants live in three urban centres: Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver.

In some cities, particularly Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary, there are one-and-a-half times more French-English FOLS immigrants than French FOLS immigrants. These two FOLS groups have sometimes very different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

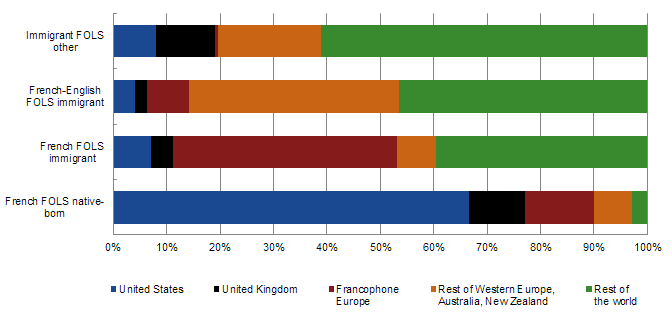

The geographic origin of international immigration to Canada has rapidly changed over recent decades. Immigrants of European origin have tended to give way to immigrants from Asia, Africa and Latin America. In this regard, French FOLS immigrants stand out from other immigrants in that a sizable proportion of them come from the African continent. One of the consequences of this trend has been that the composition of the French FOLS immigrant population has changed; Blacks accounted for 34% of that population in 2011, compared with 10% in the other two immigrant groups.

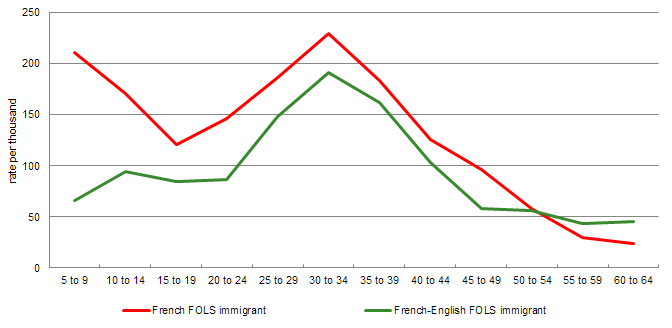

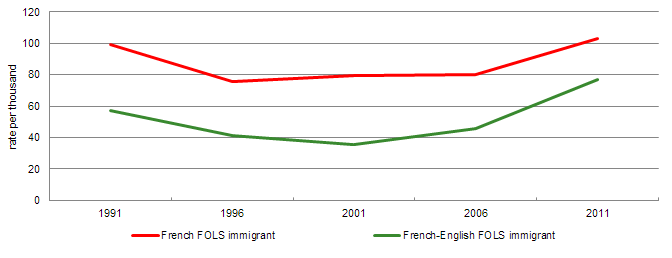

The francophone immigrant population appears to be fairly young (characterized by a large proportion in the 0-to-19 age group) when compared with non-francophone immigrants. This characteristic is partly due to the quite distinctive age composition of the French-English FOLS immigrant population, which includes a large proportion of young persons aged 10 to 24, a much higher proportion than for French FOLS immigrants and non-francophone immigrants.

Interprovincial migration varies greatly depending on whether one is a francophone or a non-francophone living in a province or territory outside Quebec. Whereas francophones tend to settle in Quebec when they migrate within Canada, non-francophones tend to choose one of the other nine provinces, especially Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta. In Quebec, the trends are completely opposite: Quebec francophones, whether Canadian-born or immigrants, migrate relatively little to the other provinces, while a much higher proportion of non-francophones leave the province. Overall, the migratory movement of francophone immigrants from the rest of Canada to Quebec is not sufficient to offset the inverse migratory movement from Quebec to the rest of Canada, and the net interprovincial migration of francophone immigrants markedly favours Canada outside Quebec. In relative terms, the net migration of francophone immigrants is even much greater than that of Canadian-born francophones and non-francophone immigrants.

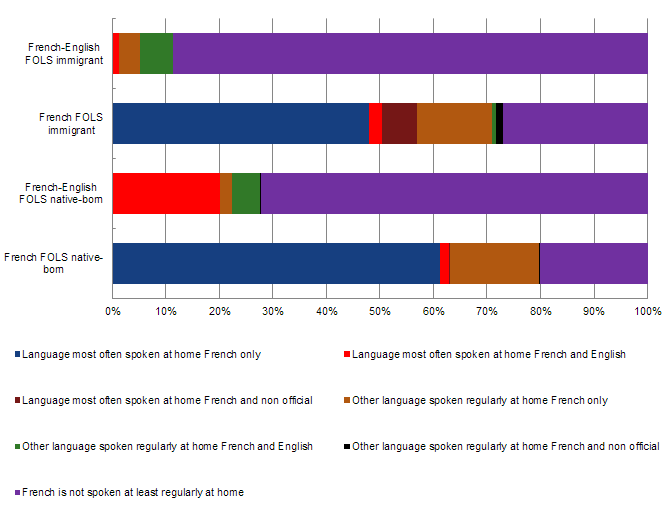

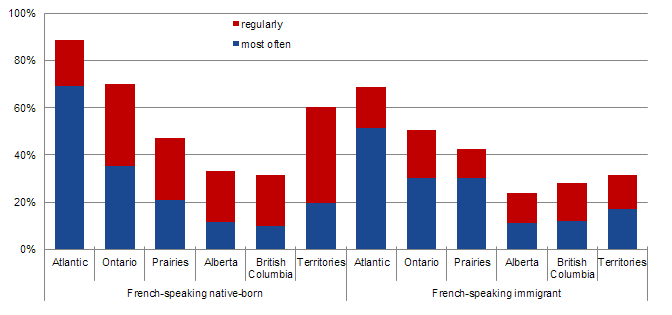

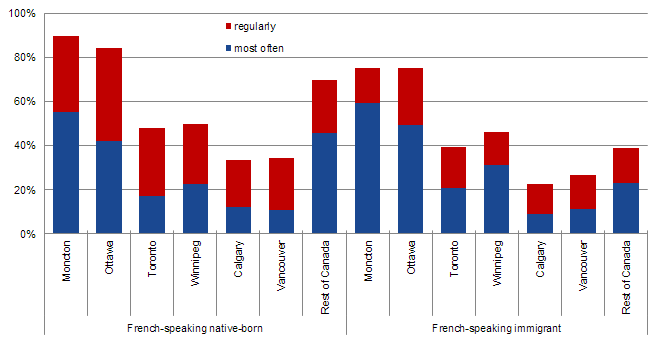

A review of the linguistic behaviours of francophone immigrants at home and at work who have settled outside Quebec reveals that French and English are in competition as languages spoken at home and in the workplace. Among French FOLS immigrants, just under half (48%) report speaking French most often at home, while 30% report speaking English and 10% a non-official language. Among French-English FOLS immigrants, the use of French at home is not very widespread, even when those who report speaking French at home on a regular basis (rather than most often) are included.

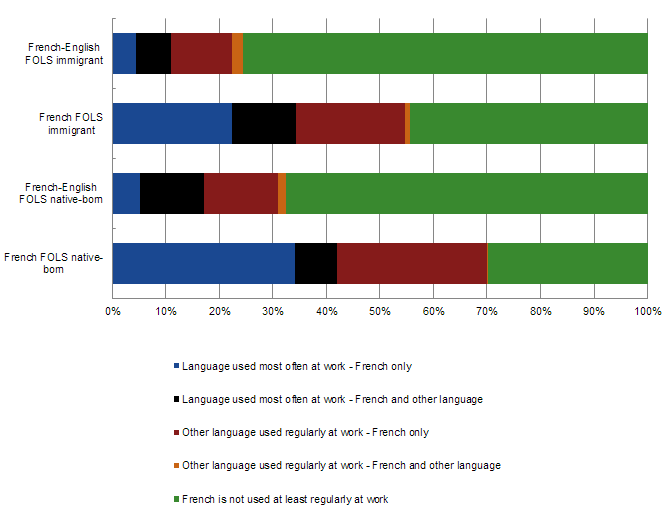

In the workplace, the presence of English is very widespread. For all groups defined by the first official language spoken (FOLS) and immigrant status, English is largely dominant as the language spoken most often at work. Among immigrants with French as their FOLS, 64% report using English most often at work.

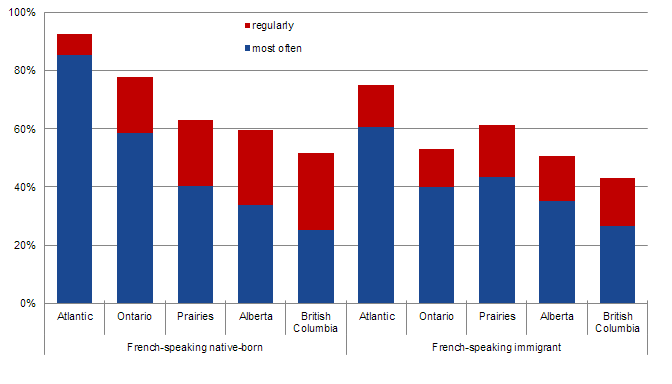

Regional trends show that the use of French diminishes from east to west: it is greatest in the Atlantic region, especially New Brunswick; it remains high in northern Ontario and in Ottawa; and it reaches its lowest level in Toronto (and in southern Ontario in general) and the two provinces of Alberta and British Columbia.

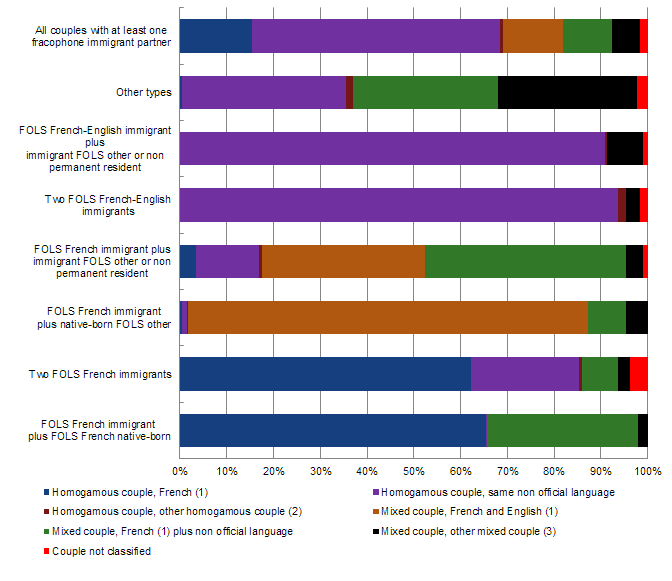

The transmission of French depends on both the type of couple in the household in which the children are living and the context in which French is used. French is primarily transmitted by couples in which both partners have only French as their FOLS. In such households, the majority of children have French as their mother tongue and their first official language spoken and speak it most often at home. The situation is completely different for other types of couples who transmit English or a non-official language. The context is also important. As a mother tongue, French is transmitted to 28% of children living in households comprising couples in which at least one partner is a francophone immigrant; it is transmitted to 38% of children as a home language (language spoken at least on a regular basis at home); and to 41% of children as a first official language spoken (FOLS). Furthermore, the competition of English is very strong in all contexts: as a mother tongue, English (excluding cases where French and English are transmitted simultaneously) is passed on to 29% of children; as a home language, it is transmitted to 61% of children; and as an FOLS, to 54% of children. In the three types of intergenerational transmission, English outranks French in terms of the number of children to whom the language is transmitted. As for non-official languages, their transmission to children is significant and more widespread than French: 43% of children have a non-official language as their only mother tongue, and nearly the same proportion, 47%, use a non-official language at least on a regular basis at home (excluding cases where a non-official language is transmitted simultaneously with French or English).

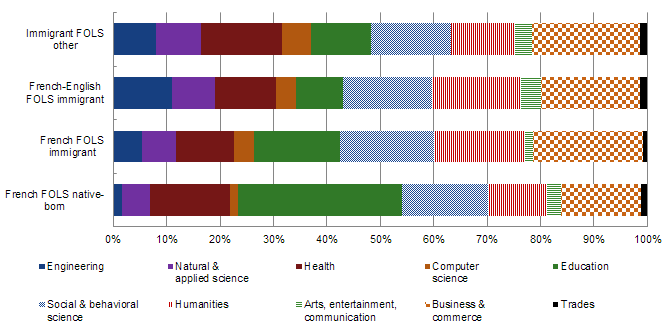

Immigrants with French as their first official language spoken (FOLS) stand out from both Canadian-born francophones and the rest of immigrants (those having both French and English as their FOLS as well as non-francophones) with regard to their highest level of education and the characteristics of the diplomas earned. Both males and females in this group have a level of education similar to French-English FOLS immigrants, but a higher level than Canadian-born persons and non-francophone immigrants. Immigrants with French as their FOLS differ from other immigrant groups in that a larger proportion of them earned their diploma or certificate in Canada. Furthermore, among those who earned their diploma or certificate abroad, a larger proportion got it in Western Europe, in most cases in a francophone country, primarily France.

Also, a smaller proportion of French FOLS immigrants than other immigrants (both those with a double French-English FOLS and non-francophones) acquired a university-level diploma or certificate in engineering.

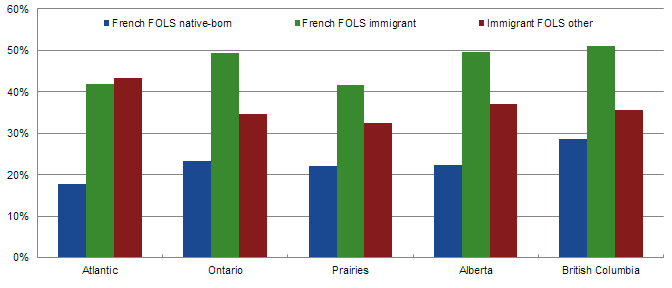

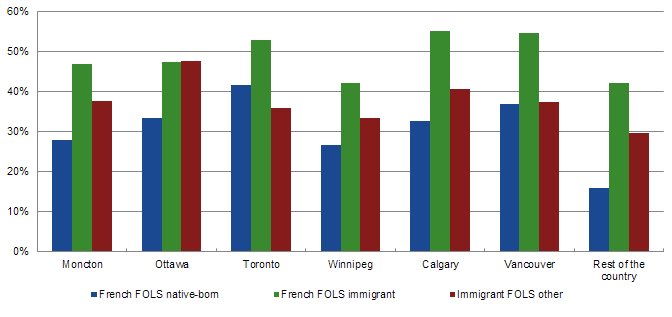

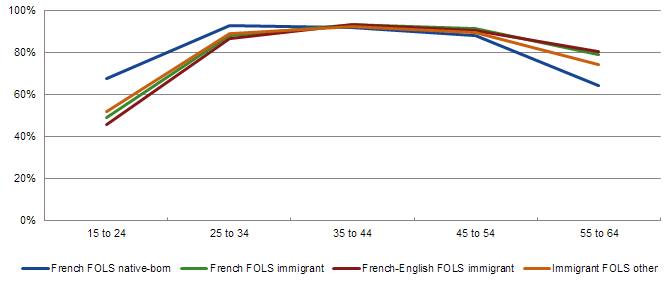

There are few differences between immigrant groups with regard to their participation in the labour force, although non-francophone immigrants have a lower level of unemployment than French FOLS immigrants, and especially French-English FOLS immigrants. Instead, socioeconomic characteristics determine the degree of integration into the labour market. The period of arrival in Canada is key in this regard, as is the continent of birth—African immigrants appear to be at a particular disadvantage.

Introduction

International immigration is one of the factors that contribute the most to the growth of the Canadian population and the evolution of the linguistic situation in Canada. At the time of the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), one in five Canadians, or 6.8 million persons, were foreign-born. Between 2006 and 2011, there were approximately 1.2 million newcomers to Canada, representing a 16.7% increase in its immigrant population, compared with a 3.4% increase in the Canadian-born population.

This report focuses on French-language immigration outside Quebec. In general, francophone minority communities outside Quebec have benefitted little from the demographic contribution of international immigration, due to the strong propensity of these immigrants to integrate into communities with an English-speaking majority. Moreover, the phenomenon of French-language immigration outside Quebec has become a matter of interest fairly recently, as has the question of its contribution to the development and growth of official language minorities.

In 2011, whereas 95.3% of the Canadian-born population outside Quebec had English as its first official language spoken, this was the case for 92% of the immigrant population. Conversely, while French was the first official language spoken for 4.6% of the Canadian-born population, the corresponding proportion for the immigrant population was no more than 2.7%, including 1.4% who had both French and English as their first official language spoken.

On March 28, 2013, the Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages announced the Roadmap for Canada's Official Languages 2013-2018: Education, Immigration, Communities, a five-year plan that brings together 14 federal departments and agencies with the objective of promoting the official languages and enhancing the vitality of official-language minorities communities (OLMCs). Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) receives $149.4 million from this Roadmap, $29.4 million of which is for the ‘Immigration to OLMCs’ initiative.

The CIC-Francophone Minority Communities Committee (CIC-FMCs Committee) was created as part of a new and simplified joint governance structure to promote francophone immigration to FMCs under the ‘Immigration to OLMCs’ initiative. The CIC-FMCs Committee builds on the work accomplished by the former CIC-FMCs Steering Committee. Under the leadership of the CIC-FMCs Committee, the initiative’s objectives are to foster the recruitment and integration of immigrants into FMCs, to increase the proportion of francophone economic immigrants in FMCs from 1.1% (2011) to 4% in 2018, and to improve the settlement and integration of francophone immigrants.

The initiative has four main components: coordinate activities and consult with key stakeholders; conduct promotional and recruitment activities in Canada and abroad; provide settlement services to French-speaking clients (immigrants); and conduct strategic data development as well as research, and develop knowledge-sharing projects for immigration to official-language minority communities. Research activities aim to shed light on the challenges associated with the vitality of both official language minority communities.

This report is an update of the 2010 report released by Statistics Canada, and like that earlier report, provides information on the demographic, linguistic, social and economic characteristics of French-language immigrants to francophone minority communities. The analyses provided are based on Canadian census data since 1991 as well as data from the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS). In 2011, the NHS had no fewer than six questions or sub-questions on official languages, dealing with knowledge of official languages, language spoken most often at home, other languages spoken on a regular basis at home, mother tongue, language used most often at work and other languages used on a regular basis at work.

This analytical report first looks at how the size and relative share of the French-speaking immigrant population outside Quebec have changed since 1991. It also provides information on the geographic distribution of that population in 2011, with particular emphasis on census metropolitan areas. The second section provides information on the geographic origins of French-speaking immigrants and their so-called visible minority status. The third and fourth sections examine the age structure of this population and the importance of interprovincial migration as factors likely to affect the evolution of these populations. Linguistic behaviours at home and at work and the phenomenon of intergenerational transmission are examined in subsequent sections. Finally, two major sections of this report provide information on these immigrants’ education and the different aspects of their participation in the labour market.

Criteria used to define a French-speaking immigrant outside Quebec

Before we present the results contained in this report, it is important to focus on how this analytical document defines the linguistic groups discussed. The question, then, is what criteria were used to define a French-speaking immigrant. For example, how is a francophone defined? The fact is that there is no standard definition of a francophone. For historical reasons,Footnote 2 Statistics Canada has generally used the criterion of mother tongue, or the first language learned at home in childhood and still understood at the time of the census. However, other criteria are also used and help to develop definitions of French-speaking persons that may be either more inclusive or more restrictive. Thus, the question arises as to whether the definition of francophone should refer to persons who have French as their mother tongue, who have French as their first official language spoken, or who speak French either most often or on a regular basis at home. Or should a broader definition be considered that includes all French speakers, or more individuals if we add young children who do not speak French but have at least one parent for whom French is the first language learned and still understood.

Additionally, in choosing a strategy for estimating a linguistic group, it is important to take at least two main factors into account. First, if the goal is to enumerate the population considering all linguistic groups on the same basis, treating them symmetrically and creating mutually exclusive categories to estimate them (e.g., English, French, others), this implies an appropriate distribution of multiple responses. Second, if the goal is to focus on a single linguistic group (e.g., francophones), the criteria for belonging can be broadened without concern for implicit overlaps between linguistic groups.

In this statistical portrait of French-speaking immigrants residing outside Quebec, the main concept used will be the first official language spoken (FOLS), which is now widely used as a linguistic definition criterion in studies on official-language minorities. Changes in the composition of the Canadian population over the years call for the concept of francophone group or community to be redefined or expanded, given that a significant number of people whose mother tongue is neither French nor English use French predominantly or on a regular basis in their daily lives.

The decision to create the concept of first official language spoken was based on a number of considerations. First, the substantial increase in international immigration since the mid-1980s has led to an increase in the population with an “other” mother tongue across Canada (20% in 2011), such persons often being designated by the term “allophones.”

Since an allophone cannot become a francophone based on mother tongue, but can become one by adopting French as the language spoken most often at home or in the public sphere, the question arises as to how to designate individuals’ first official language or, more specifically, how to distribute allophones between French and English based on their reported knowledge of either official language.

It was this line of questioning that led to different definitions of the concept of first official language spoken (Statistics Canada 1989). This concept echoes the spirit of the new version of the Official Languages Act (1988), which stipulates, in section 32(2), that the government may have regard to “the number of persons composing the English or French linguistic minority population of the area served by an office or facility, the particular characteristics of that population and the proportion of that population to the total population of that area.”

The concept of first official language was chosen by the federal government in December 1991 in the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations. Section 2 of the Regulations describes the method used to determine the “first official language spoken,” namely the first of the two variants presented in Statistics Canada (1989), a method that successively takes account of the responses to the questions on knowledge of official languages, mother tongue and language spoken most often at home. The “first official language spoken” variable is thus not a census question, but rather, is derived from three questions in the linguistic module of the census.

This report therefore draws a statistical portrait of French-speaking immigrants outside Quebec, who will also be referred to generally as francophone immigrants, using the “first official language spoken” variable. In keeping with the practice of the Treasury Board Secretariat, the population with French as its first official language spoken (FOLS) includes people with only French as their FOLS and half of the individuals with both French and English as their FOLS; the latter category covers people to whom neither French nor English can be assigned based on the responses to the three variables mentioned above. However, on more than one occasion, we will present the categories “French” FOLS and “French-English” FOLS separately, since these two sub-populations differ in their sociodemographic characteristics and linguistic practices.

1 French-speaking immigrants living outside Quebec

This section examines the demographic weight and geographic distribution, by province and census metropolitan area (CMA), of francophone immigrants who reside in provinces and territories of Canada outside Quebec.

1.1 Demographic weight

French-speaking immigrants (that is, immigrants whose first official language spoken is French) living outside Quebec constitute a small population compared with the total number of immigrants or the total French-speaking population. In Canada, most French-speaking immigrants live in the province of Quebec. Of the approximately 700,000 francophone immigrants living in Canada at the time of the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) (including those with both French and English as their FOLS), more than 650,000 or 81% were living in Quebec. The remaining 153,000 immigrants, or 19% of the Canadian total, were distributed among the nine other provinces and three territories, including a large proportion living in Ontario.

In the 2011 NHS, there were nearly 74,500 immigrants outside Quebec for whom French was the first official language spoken and 79,400 who were assigned both French and English as first official languages spoken (French-English FOLS) (Table 1.1). In relation to the 2006 Census, this was a sizable increase in the population of the first group, which grew by 16,000 (representing a five-year growth rate of 22.3%), while the increase in the second group was only 3,000 (4.3% growth rate). In general, a substantial share of persons with a double official language (French-English FOLS), among both native-born Canadians and immigrants, live outside Quebec. In Canada in 2011, 12% of native-born Canadians and immigrants whose first official language was French were living outside Quebec, compared with 32% of French-English FOLS native-born Canadians and immigrants. These percentages have remained stable over the past 20 years. If French-English FOLS persons are redistributed equally between the French and English groups, as stipulated in the 1991 Official Language (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations, there are 115,000 immigrants living outside Quebec with French as their first official language, representing nearly 17% of all French-speaking immigrants living in Canada (see table in Appendix A).

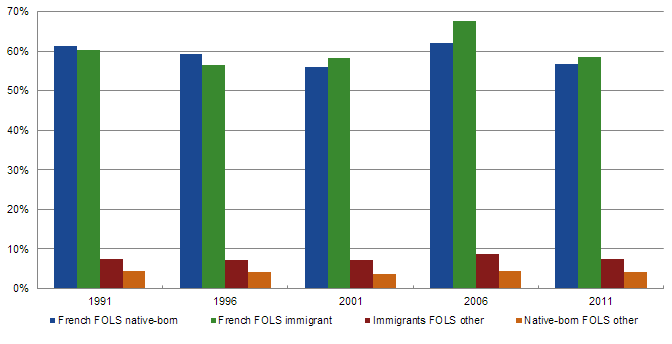

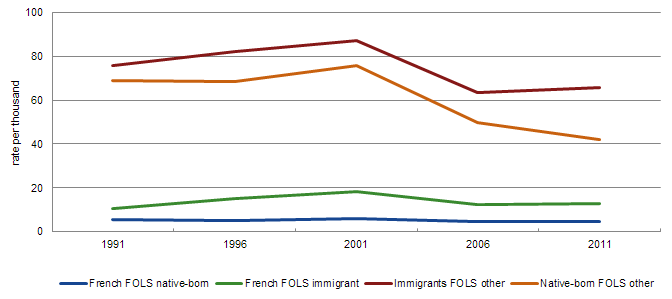

The changing numbers indicate continuous growth between 1991 and 2011 for almost all groups defined by first official language spoken (FOLS) and immigrant status and all periods, both before and after redistribution of the French-English category. However, we observe that the population of non-permanent residents declined between 1991 and 1996, but increased between 1996 and 2011, both in Canada as a whole and in Quebec. The decrease in the weight of the Canadian-born French FOLS population continued in 2011 compared with 2006 (13.0% in 2006 and 12.3% in 2011), a phenomenon mainly attributable to the increase in francophone immigration (Table 1.1). Also, there was a slight decrease from 2006 to 2011 in the proportion of French-English FOLS persons outside Quebec, which stood at 32.2% in 2011.

Table 1.1: Population according to immigrant status and first official language spoken (FOLS), Canada, Quebec and Canada less Quebec, 1991 to 2011

| Population (in thousands) | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French FOLS native-born | 6,399 | 6,534 | 6,594 | 6,705 | 6,806 |

| French-English FOLS native-born | 78 | 88 | 88 | 98 | 92 |

| French FOLS immigrant | 288 | 337 | 379 | 473 | 572 |

| French-English FOLS immigrant | 131 | 161 | 188 | 226 | 246 |

| Immigrants FOLS other | 3,924 | 4,473 | 4,881 | 5,488 | 5,957 |

| Native-born FOLS other | 15,951 | 16,769 | 17,309 | 17,985 | 18,822 |

| Non-permanent resident | 223 | 167 | 199 | 265 | 356 |

| Population (in thousands) | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French FOLS native-born | 5,507 | 5,654 | 5,714 | 5,830 | 5,969 |

| French-English FOLS native-born | 51 | 58 | 58 | 63 | 59 |

| French FOLS immigrant | 250 | 293 | 327 | 412 | 498 |

| French-English FOLS immigrant | 88 | 105 | 118 | 150 | 167 |

| Immigrants FOLS other | 254 | 266 | 262 | 290 | 310 |

| Native-born FOLS other | 617 | 627 | 606 | 642 | 662 |

| Non-permanent resident | 44 | 41 | 40 | 49 | 67 |

| Population (in thousands) | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French FOLS native-born | 892 | 880 | 880 | 875 | 837 |

| French-English FOLS native-born | 27 | 30 | 30 | 35 | 33 |

| French FOLS immigrant | 38 | 44 | 53 | 61 | 74 |

| French-English FOLS immigrant | 43 | 55 | 70 | 76 | 79 |

| Immigrants FOLS other | 3,670 | 4,207 | 4,619 | 5,198 | 5,647 |

| Native-born FOLS other | 15,334 | 16,141 | 16,703 | 17,344 | 18,160 |

| Non-permanent resident | 179 | 125 | 158 | 216 | 289 |

| Population | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French FOLS native-born | 13.9% | 13.5% | 13.3% | 13.0% | 12.3% |

| French-English FOLS native-born | 34.4% | 33.8% | 34.4% | 35.2% | 35.4% |

| French FOLS immigrant | 13.3% | 13.1% | 13.9% | 12.9% | 13.0% |

| French-English FOLS immigrant | 32.9% | 34.4% | 37.1% | 33.7% | 32.2% |

| Immigrants FOLS other | 93.5% | 94.1% | 94.6% | 94.7% | 94.8% |

| Native-born FOLS other | 96.1% | 96.3% | 96.5% | 96.4% | 96.5% |

| Non-permanent resident | 80.3% | 75.2% | 79.8% | 81.6% | 81.2% |

FOLS = Population of groups defined according to first official language spoken.

The category 'FOLS other' includes FOLS groups 'English' and 'neither English nor French'.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 Censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

Outside Quebec, French-speaking immigrants accounted for 11.7% of the French-speaking population as a whole and 2.0% of all immigrants (Table 1.2). According to two other alternative estimates, either counting only immigrants with French as their only official language spoken or adding those with French and English as a double official language, the relative weight of immigrants within the overall French-speaking population varies considerably. Thus, the percentage of immigrants within the French-speaking population outside Quebec was 8.2% in 2011—not considering those with French and English as a double first official language—and 15.0% when including them. The same applies to their relative weight within the immigrant population: 1.3% in 2011 according to the first calculation and 2.7% when French-English FOLS immigrants are included.

Outside Quebec, the relative weight of francophone immigrants within the French-speaking population as a whole has steadily increased since the 1991 Census according to all three estimates. According to the estimate in which there is redistribution of the French-English category, the percentage of French-speaking immigrants rose from 6.2% to 11.7% between 1991 and 2011. However, the change in their relative weight within the overall immigrant population was more moderate. According to the estimate with redistribution, there was a much smaller increase, from 1.6% in 1991 to 2.0% in 2011.

Table 1.2: Percentage of French-speaking immigrants within the total French official language population and within the immigrant population according to three estimations, Canada less Quebec, 1991 to 2011

| Year | French FOLS only | French FOLS (after redistributing the French-English category) | French and French-English FOLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 4.1% | 6.2% | 8.1% |

| 1996 | 4.8% | 7.5% | 9.9% |

| 2001 | 5.6% | 8.9% | 11.9% |

| 2006 | 6.5% | 10.0% | 13.1% |

| 2011 | 8.2% | 11.7% | 15.0% |

| Year | French FOLS only | French FOLS (after redistributing the French-English category) | French and French-English FOLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1.0% | 1.6% | 2.2% |

| 1996 | 1.0% | 1.7% | 2.3% |

| 2001 | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.6% |

| 2006 | 1.1% | 1.9% | 2.6% |

| 2011 | 1.3% | 2.0% | 2.7% |

FOLS = Population of groups defined according to first official language spoken.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 Censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

1.2 Geographic distribution

The francophone immigrant population is unequally distributed among the provinces and territories outside Quebec. The largest pool is found in Ontario, which accounts for almost 70% of all French-speaking immigrants living outside Quebec. Ontario is also the province with the majority of Canadian-born francophones outside Quebec, as well as the majority of immigrants residing outside Quebec (51.9% and 62.2% respectively) (Table 1.3). In the 2011 NHS, the French-speaking immigrant population in that province was 76,600, a much higher figure than in British Columbia, which had the second- largest francophone immigrant population (15,500). Alberta, which saw its share of the French FOLS immigrant population increase (from 8.0% in 2006 to 10.3% in 2011), ranked third with almost 12,000 individuals. The other provinces and territories fell well below this number. In New Brunswick, for example, the 2011 NHS enumerated only 3,500 French-speaking immigrants, or 3.1% of all francophone immigrants in Canada (outside Quebec), although that province accounts for more than 25% of all Canadian-born francophones outside Quebec.

The francophone immigrant population, as a proportion of the entire francophone population, was more than 25% In British Columbia and over 10% in three other provinces: Newfoundland and Labrador (10.9%), Ontario (14.8%) and Alberta (17.5%). After relative stability between 1991 and 2006, with proportions ranging between 3.0% and 5.0%, the Prairie provinces, more specifically Manitoba and Saskatchewan, posted an increase of more than 3 percentage points in the proportion of French FOLS immigrants between 2006 and 2011, from 5.1% to 8.3% in Manitoba and from 4.9% to 8.3% in Saskatchewan.

In New Brunswick—the province with the second largest number of francophones outside Quebec—French-speaking immigrants accounted for only 1.5% of the overall French-speaking population in the 2011 NHS (Chart 1.1, panel A).

Of all the provinces and territories excluding Quebec, New Brunswick has the highest relative share of francophone immigrants in the overall immigrant population at 12.2%. However, this share is smaller than the relative weight of the francophone population in that province, namely one-third. In the other provinces and territories, the corresponding percentage is much lower, mostly under 3%, particularly in Ontario (2.1%) and British Columbia (1.3%), the two provinces with the largest proportion of immigrants in their total population.

Table 1.3: Population and percentage distribution according to immigrant status and first official language spoken (FOLS) after redistribution of the French-English category for Canada, provinces (excluding Quebec) and the territories, 2011

| Province and territory (thousands) | Native-born French | Immigrants-French | Immigrants-Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.5 | 0.2 | 9.0 |

| Prince Edward Island | 4.6 | 0.1 | 7.0 |

| Nova Scotia | 28.3 | 1.4 | 46.9 |

| New Brunswick | 227.6 | 3.5 | 25.0 |

| Ontario | 442.5 | 76.6 | 3,534.8 |

| Manitoba | 35.2 | 3.2 | 181.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 11.7 | 1.1 | 67.7 |

| Alberta | 55.4 | 11.7 | 632.4 |

| British Columbia | 43.7 | 15.5 | 1,176.4 |

| Yukon | 1.0 | 0.2 | 3.6 |

| Northwest Territories | 1.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| Nunavut | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Total | 852.9 | 113.5 | 5,687.3 |

| Province and territory (Percentage) | Native-born French | Immigrants-French | Immigrants-Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 3.3% | 1.2% | 0.8% |

| New Brunswick | 26.7% | 3.1% | 0.4% |

| Ontario | 51.9% | 67.5% | 62.2% |

| Manitoba | 4.1% | 2.8% | 3.2% |

| Saskatchewan | 1.4% | 0.9% | 1.2% |

| Alberta | 6.5% | 10.3% | 11.1% |

| British Columbia | 5.1% | 13.7% | 20.7% |

| Yukon | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Northwest Territories | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| Nunavut | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

The category ‘FOLS other’ includes FOLS groups ‘English’ and ‘neither English nor French’.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 2011 National Household Survey

The change observed since the 1991 Census accounts for the interprovincial contrasts observed in 2011. This change over time reflects the increase in the proportion of francophone immigrants both in the French-speaking population and in the immigrant population. The trend is more marked in the former. For example, in British Columbia, where francophone immigrants made up 18% of the French-speaking population in 1991, that percentage rose to over 26% in 2011. A similar evolution is observed in Ontario, Alberta and the territories, which saw increases, respectively, from 8% to 15%, from 9% to 17.5% and from 5% to 11% between 1991 and 2011.

Chart 1.1: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the population for whom French is the first official language spoken and proportion of French FOLS immigrants in the immigrant population (after redistribution of the French-English category), provinces and territories excluding Quebec, 1991 to 2011

Panel A: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the population for whom French is the first official language spoken

Text version: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the population for whom French is the first official language spoken

| Province and territories | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.L. | 6.2% | 11.1% | 10.2% | 10.9% | 10.9% |

| P.E.I. | 1.3% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.4% |

| N.S. | 3.4% | 3.1% | 3.8% | 4.0% | 4.6% |

| N.B. | 1.1% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Ont. | 7.9% | 9.5% | 11.6% | 12.8% | 14.8% |

| Man. | 3.8% | 3.7% | 4.2% | 5.1% | 8.3% |

| Sask. | 4.3% | 3.9% | 4.0% | 4.9% | 8.3% |

| Alta. | 8.6% | 9.6% | 10.2% | 12.7% | 17.5% |

| B.C. | 17.4% | 21.1% | 23.2% | 23.9% | 26.2% |

| TerritoriesChart 1.1 footnote * | 5.2% | 6.2% | 8.6% | 9.9% | 12.4% |

| Canada excluding Quebec | 6.2% | 7.5% | 8.9% | 10.0% | 13.3% |

Panel B: Proportion of French FOLS immigrants in the immigrant population

Text version: Proportion of French FOLS immigrants in the immigrant population

| Province and territories | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N.L. | 1.9% | 2.9% | 2.6% | 2.5% | 2.0% |

| P.E.I. | 1.6% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 2.6% | 1.6% |

| N.S. | 3.1% | 2.5% | 3.1% | 2.9% | 2.8% |

| N.B. | 10.9% | 11.3% | 11.9% | 12.8% | 12.2% |

| Ont. | 1.7% | 1.8% | 2.0% | 2.0% | 2.1% |

| Man. | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.7% |

| Sask. | 1.5% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Alta. | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| B.C. | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.3% |

| TerritoriesChart 1.1 footnote * | 2.0% | 2.5% | 3.2% | 4.1% | 4.3% |

| Canada excluding Quebec | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 2.0% |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

Immigrants are concentrated in Canada’s major metropolitan areas and the French-speaking immigrant population is no exception. Outside Quebec, the three urban areas with the largest population of French-speaking immigrants at the time of the 2011 NHS are, in descending order, Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver. These three cities alone account for nearly three-quarters of francophone immigrants (after redistribution of the French-English category). Toronto has a population of 39,500 francophone immigrants compared with 52,000 French-speaking persons born in Canada (Table 1.4), accounting for 43% of that city’s francophone population. In Vancouver, more than one-third of French-speaking persons are immigrants. In Ottawa, there are 23,200 French-speaking immigrants compared with 131,500 Canadian-born French speakers, representing 15% of the francophone population. The other cities have much smaller populations of French-speaking immigrants. Calgary ranks fourth with close to 5,700 French-speaking immigrants and Edmonton ranks fifth with 4,900. The rest of the cities follow, none with more than 3,000 francophone immigrants. Some cities with a large francophone population, such as Moncton, Sudbury and Edmundston, have at most 1,500 French-speaking immigrants. These cities also receive relatively few immigrants in general.

Statistics from the 2011 NHS show that for all the provinces and territories excluding Quebec, the number of immigrants with a double official language (French-English FOLS) is larger than the number of immigrants whose first official language is French (79,400 versus 74,500). This is also the situation in British Columbia (11,600 versus 9,600), Ontario (55,200 versus 49,600) and Alberta (8,700 versus 7,500), as well as in some census metropolitan areas (CMAs), including Toronto and Vancouver (Table 1.4). Although this is an important characteristic described in the 2010 version of this study, the extent of the differences between the two sub-populations diminished between 2006 and 2011, especially in the CMAs. In 2011, there were 22,700 French FOLS immigrants and 33,600 French-English FOLS immigrants in Toronto. In Calgary, the gap narrowed to less than 1,000 persons, and in Hamilton, the French FOLS immigrant population was equal in size to the population of French-English FOLS immigrants.

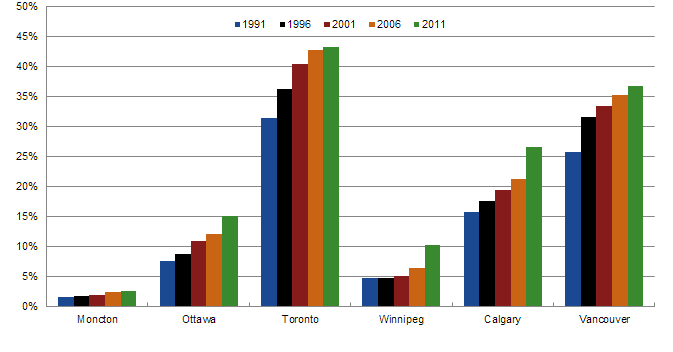

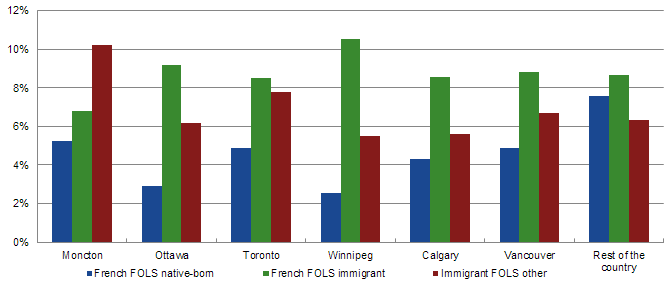

As with the situation at the provincial level, the change since the 1991 Census accounts for the contrasts observed in 2011 between census metropolitan areas. It reflects the increase in the proportion of French-speaking immigrants in both the francophone population and the immigrant population. (Table 1.4; Charts 1.2-a and b). An increase is also seen in four large cities: Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary and Vancouver. Between the 1991 Census and the 2011 NHS, the relative weight of French-speaking immigrants within the total francophone population rose from 31% to 43% in the Toronto CMA, from 26% to 37% in Vancouver and from 8% to 15% in Ottawa. In Calgary, the percentage of francophone immigrants in the total francophone population grew from 16% to more than 25% between 1991 and 2011. When compared with 1991, Moncton and Winnipeg also saw their respective proportions of immigrants increase in 2011, to 2.6% and 10.3% respectively.

An analysis of how the percentage of these immigrants within the overall immigrant population has changed over time reveals great stability over the study period (Chart 1.2 b). However, whereas the 2006 Census showed an increase in the proportion of francophone immigrants within the immigrant population of Moncton, which rose from 15.3% in 1991 to 24.3% in 2006, the 2011 NHS shows a decrease in their proportion to 19.7%. This is due to a larger increase of non-francophone immigration to that city between 2006 and 2011. Steady growth was only seen in the Ottawa CMA. Elsewhere, especially in the largest urban centres such as Toronto and Vancouver, immigrants whose first official language is French make up less than 2% of the immigrant population.

Table 1.4: Population count according to immigrant status and first official language spoken (FOLS) (before and after equal redistribution of the French-English category), and the percentage of French-speaking immigrants within the total French-speaking population and within the total immigrant population, for selected census metropolitan areas, 2011

| Census metropolitan area (CMA) | CMA total population | Native-born French FOLS | Native-born French and English FOLS | Immigrants French FOLS | Immigrants French and English FOLS | Other immigrants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 5,521.2 | 45.9 | 12.2 | 22.7 | 33.6 | 2,481.1 |

| Ottawa | 1,215.7 | 128.6 | 5.8 | 17.3 | 11.8 | 175.3 |

| Vancouver | 2,280.7 | 18.1 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 10.1 | 896.8 |

| Calgary | 1,199.1 | 15.3 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 306.0 |

| Edmonton | 1,139.6 | 20.0 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 225.6 |

| Hamilton | 708.2 | 8.2 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 162.7 |

| Winnipeg | 714.6 | 23.1 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 143.9 |

| Windsor | 315.5 | 8.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 67.8 |

| Kitchener | 469.9 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 106.3 |

| London | 467.3 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 85.7 |

| Victoria | 336.2 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 58.7 |

| Moncton | 135.5 | 44.6 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 4.7 |

| St. Catharines-Niagara | 384.0 | 10.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 62.9 |

| Halifax | 384.5 | 9.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 29.9 |

| Oshawa | 351.7 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 55.3 |

| Kingston | 153.9 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 17.5 |

| Greater Sudbury | 158.3 | 39.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 9.3 |

| Kelowna | 176.4 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 24.0 |

| Edmundston (CA) | 21.1 | 19.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Guelph | 139.7 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 27.2 |

| Census metropolitan area (CMA) | CMA total population | Native-born French FOLS | Immigrants French FOLS | Other immigrants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 5,521.2 | 52.0 | 39.5 | 2,497.9 |

| Ottawa | 1,215.7 | 131.5 | 23.2 | 181.2 |

| Vancouver | 2,280.7 | 19.9 | 11.5 | 901.8 |

| Calgary | 1,199.1 | 15.8 | 5.7 | 308.2 |

| Edmonton | 1,139.6 | 20.6 | 4.9 | 227.3 |

| Hamilton | 708.2 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 163.7 |

| Winnipeg | 714.6 | 23.4 | 2.7 | 144.6 |

| Windsor | 315.5 | 8.9 | 1.8 | 68.5 |

| Kitchener | 469.9 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 107.2 |

| London | 467.3 | 5.5 | 1.4 | 86.3 |

| Victoria | 336.2 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 58.9 |

| Moncton | 135.5 | 44.7 | 1.2 | 4.8 |

| St. Catharines-Niagara | 384.0 | 10.7 | 1.2 | 63.2 |

| Halifax | 384.5 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 30.2 |

| Oshawa | 351.7 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 55.4 |

| Kingston | 153.9 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 17.6 |

| Greater Sudbury | 158.3 | 39.6 | 0.4 | 9.4 |

| Kelowna | 176.4 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 24.0 |

| Edmundston (CA) | 21.1 | 19.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Guelph | 139.7 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 27.3 |

| Census metropolitan area (CMA) | Immigrants French FOLS within the total French FOLS population | Immigrants French FOLS within the total immigrant population |

|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 43% | 2% |

| Ottawa | 15% | 11% |

| Vancouver | 37% | 1% |

| Calgary | 27% | 2% |

| Edmonton | 19% | 2% |

| Hamilton | 26% | 2% |

| Winnipeg | 10% | 2% |

| Windsor | 17% | 3% |

| Kitchener | 22% | 1% |

| London | 20% | 2% |

| Victoria | 20% | 2% |

| Moncton | 3% | 20% |

| St. Catharines-Niagara | 10% | 2% |

| Halifax | 10% | 3% |

| Oshawa | 12% | 1% |

| Kingston | 10% | 3% |

| Greater Sudbury | 1% | 4% |

| Kelowna | 16% | 2% |

| Edmundston (CA) | 2% | 64% |

| Guelph | 12% | 1% |

FOLS = Population according to first official language spoken.

CMA = Census metropolitan area.

The category 'FOLS other' includes FOLS groups 'English' and 'neither English nor French'.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2011 National Household Survey.

Chart 1.2: Proportion of immigrants for whom French is the first official language in the French-speaking population (after redistribution of the French-English category) and in the immigrant population, selected census metropolitan areas outside Quebec, 1991 to 2011

Panel A: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the French-speaking population

Text version: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the French-speaking population

| City | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moncton | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 2.6% |

| Ottawa | 7.5% | 8.7% | 10.9% | 12.0% | 15.0% |

| Toronto | 31.4% | 36.2% | 40.3% | 42.7% | 43.2% |

| Winnipeg | 4.6% | 4.6% | 5.1% | 6.4% | 10.3% |

| Calgary | 15.7% | 17.5% | 19.3% | 21.1% | 26.5% |

| Vancouver | 25.7% | 31.5% | 33.4% | 35.2% | 36.6% |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

Panel B: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the immigration population

Text version: Proportion of French-speaking immigrants in the immigration population

| City | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moncton | 15.3% | 16.6% | 21.4% | 24.3% | 19.7% |

| Ottawa | 8.1% | 8.5% | 9.5% | 10.3% | 11.3% |

| Toronto | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Winnipeg | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| Calgary | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| Vancouver | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.3% |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

1.3 Distribution in four census metropolitan areas (CMAs)

The numbers and proportion of the francophone population in the provinces and territories outside Quebec vary greatly from one region to the next and from one CMA to another. Within a given area, francophone immigrants do not necessarily live in the same area as Canadian-born francophones. These immigrants tend to settle in the same places as most other immigrants, and not always in areas with the greatest concentrations of Canadian-born francophones. Consequently, close to three-quarters (74.3%) of francophone immigrants live in the five largest census metropolitan areas outside Quebec: Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton and Ottawa.

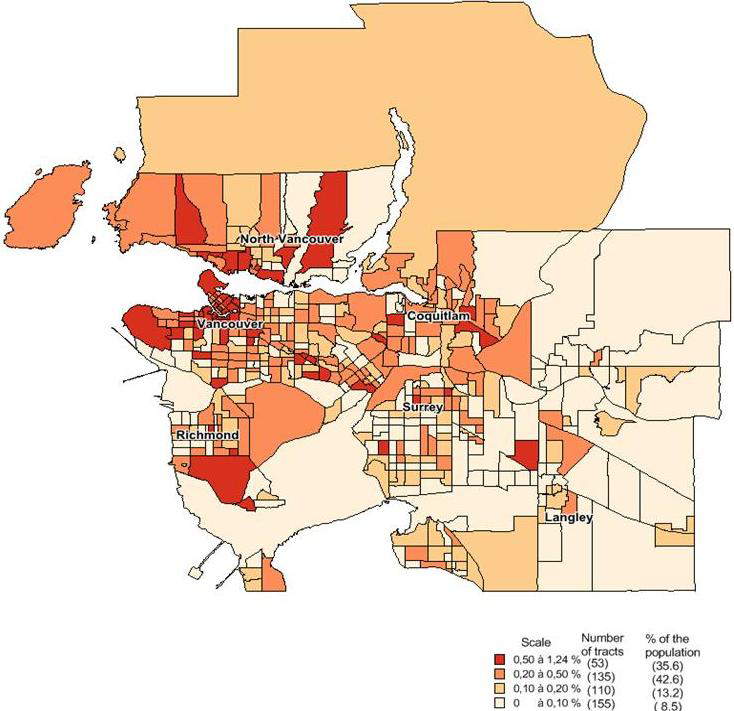

What is happening at a more specific geographic level? In the large cities, do francophone immigrants settle in the same areas as the Canadian-born francophone population? Four metropolitan areas with both a sizable Canadian-born francophone population and francophone immigrant population were selected to examine the distribution of the francophone population within them. These CMAs are Ottawa (Ontario side only), Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver. For each of these CMAs, two maps were produced at the census tract level, with one map showing the geographic distribution of the Canadian-born francophone population and the other showing the distribution of francophone immigrants.

According to the 2011 Census Dictionary, “Census tracts (CTs) are small, relatively stable geographic areas that usually have a population between 2,500 and 8,000 persons. They are located in census metropolitan areas and in census agglomerations that had a core population of 50,000 or more in the previous census.” CTs follow permanent and easily recognizable physical features, such as rivers and roads, as closely as possible; they are as homogeneous as possible in terms of socioeconomic characteristics; and they are as compact as possible. Toronto has 1,076 CTs, Ottawa (Ontario side) has 201, Winnipeg has 170 and Vancouver has 453.

The representation selected for the population distribution by census tract is as follows. The population of each francophone group (Canadian-born or immigrants) in each CT and each CMA was divided by the total population of the group living in the CMA, and the result was multiplied by 100 so that all the CTs for a given group in the same CMA sum to 100%. The percentages were grouped into four intervals specific to each CMA. An advantage of this representation is that the same scale can be used for each city. On the maps, the darker the colour, the higher the number of francophones living in the CT. The legend indicates the scale used, the number of CTs and the percentage of the total population corresponding to each interval of the scale.

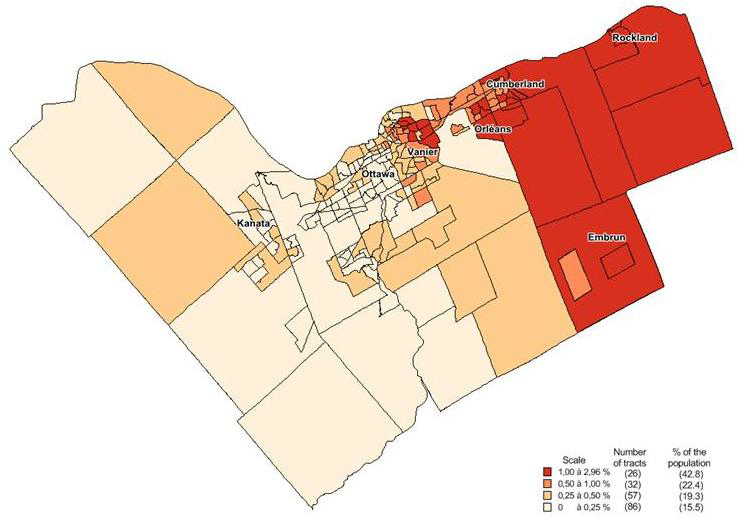

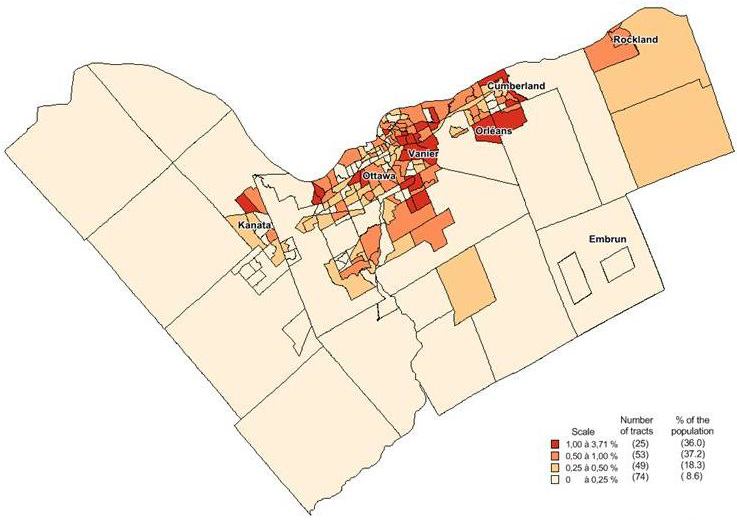

Two maps are provided for each CMA. The first map shows the distribution of the Canadian-born francophone population, while the second shows the distribution of francophone immigrants. The maps are numbered 1.1 to 1.8. The first two maps (maps 1.1 and 1.2) are of Ottawa. A comparison of the two maps shows that Canadian-born francophones are primarily concentrated in the eastern part of the CMA, from Vanier to Rockland in the east and Embrun in the southeast. Francophone immigrants live primarily in the more highly populated areas, and very few of them have chosen the suburbs furthest from the centre.

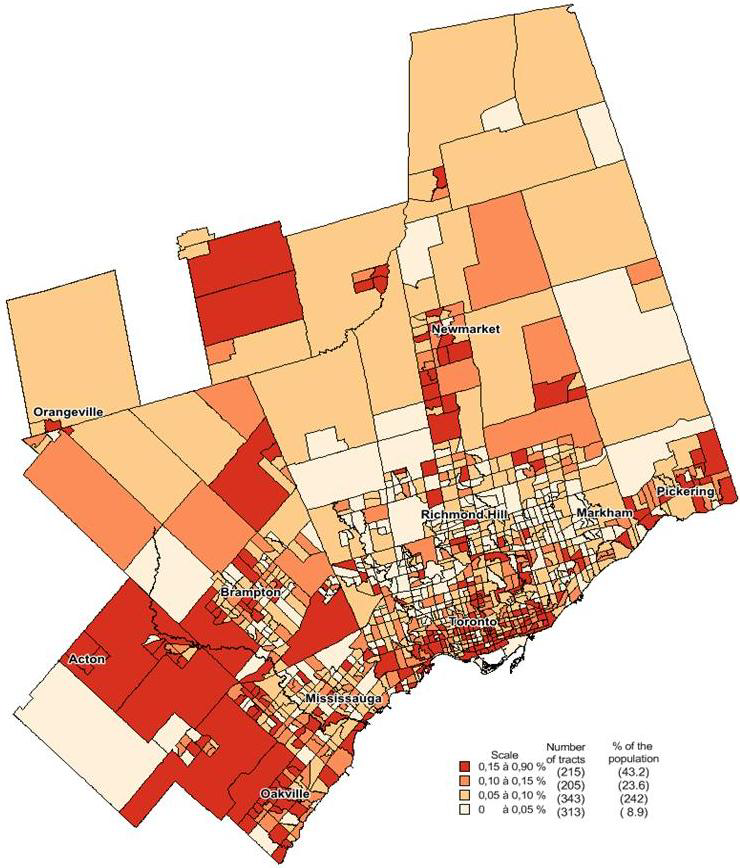

Toronto’s situation is similar to that of Ottawa (maps 1.3 and 1.4). A significant proportion of Canadian-born francophones who have settled in this Canadian metropolis live in suburbs far from the city, in the region of Acton, Orangeville and Newmarket. Other concentrations can be seen in Oakville, Mississauga and Brampton in the south and in Pickering and Ajax in the north. The francophone immigrant population for the most part lives in Toronto itself, as well as in Mississauga and Brampton.

In Winnipeg, Canadian-born francophones are largely concentrated in St-Boniface on the eastern shore of the Red River and in the southern suburbs of the CMA, toward St-Norbert. The immigrants are more dispersed, although they tend to live in the most densely populated tracts (maps 1.5 and 1.6).

Vancouver is different from Ottawa, Toronto and Winnipeg. Unlike in those three cities, the distribution of the two francophone groups seems to be quite similar in Vancouver (maps 1.7 and 1.8). However, as can be seen, a higher proportion of Canadian-born francophones than immigrants are located in the southeastern part of the city, toward Coquitlam, Surrey and especially Langley and the surrounding areas. Francophone immigrants are more concentrated in North and West Vancouver, as well as in Vancouver itself.

In conclusion, an analysis of the types of occupation in the four urban areas studied reveals that Canadian-born francophones are more likely to settle in the remote suburbs than immigrants, which may mean that Canadian-born francophones settled there earlier. Francophones born in Canada tend to form settlement clusters in Ottawa and Winnipeg, and are more spread out throughout the CMA area in Toronto and Vancouver.

Francophone immigrants live primarily in the most densely populated areas of the cities. In this regard, only Vancouver is different from the other three urban centres, in that immigrants also live in the remote suburbs.

In summary, the francophone immigrant population living outside Quebec is relatively small, both in absolute numbers and in relation to the total French-speaking population or the total immigrant population. However, the relative weight of francophone immigrants within the French-speaking population increased from 6.2% to 11.7% between 1991 and 2011, while its weight within the immigrant population saw a more moderate change, at 2% in 2011.

The majority of francophone immigrants outside Quebec (67.5%) are concentrated in Ontario. Also, three-quarters of French-speaking immigrants live in three urban areas: Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver.

We have seen that the francophone immigrant population outside Quebec consists of two groups: those with French only as their first official language spoken (French FOLS immigrants) and, based on the Method 1 algorithm used to determine the first official language spoken, those with both French and English as their FOLS (French-English FOLS immigrants). There are slightly more French-English FOLS immigrants than French FOLS immigrants (79,400 versus 74,500 in 2011). In some cities, particularly Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary, the bigger population of French-English FOLS immigrants is more pronounced. As the following sections will show, these two FOLS groups have demographic and socioeconomic characteristics that are sometimes quite different.

Map 1.1: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Ottawa census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Ottawa census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of Canadian-born Francophones in the Ottawa census metropolitan area (CMA), Ontario side only, by census tract.

The map represents 201 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 26 tracts, representing 42.8% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 1% and 2.96% of the population.

There are 32 tracts, representing 22.4% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1% of the population.

There are 57 tracts, representing 19.3% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.25% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 86 tracts, representing 15.5% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0% and 0.25% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of Canadian-born Francophones are found in the Vanier neighbourhood and in the eastern area of the CMA, including Orleans, Rockland, and Embrun.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.2: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Ottawa census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Ottawa census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of immigrant Francophones in the Ottawa census metropolitan area (CMA), Ontario side only, by census tract.

The map represents 201 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 25 tracts, representing 36.0% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 1% and 3.71% of the population.

There are 53 tracts, representing 37.2% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1% of the population.

There are 49 tracts, representing 18.3% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.25% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 74 tracts, representing 8.6% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0% and 0.25% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of immigrant Francophones are located in the most densely populated areas of Ottawa proper, including Vanier, Kanata, Orleans and Cumberland.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.3: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Toronto census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Toronto census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of Canadian-born Francophones in the Toronto census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 1076 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 215 tracts, representing 43.2% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.15% and 0.9% of the population.

There are 205 tracts, representing 23.6% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.1% and 0.15% of the population.

There are 343 tracts, representing 24.2% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.05% and 0.1% of the population.

There are 313 tracts, representing 8.9% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0% and 0.05% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of Canadian-born Francophones are in the belt around the City of Toronto: Mississauga, Oakville, Brampton, Acton, Orangeville, Newmarket and Pickering.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.4: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Toronto census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Toronto census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of immigrant Francophones in the Toronto census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 1076 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 210 tracts, representing 46.4% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.15% and 0.65% of the population.

There are 210 tracts, representing 24.1% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.1% and 0.15% of the population.

There are 288 tracts, representing 19.7% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.05% and 0.1% of the population.

There are 368 tracts, representing 9.8% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0% and 0.05% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of immigrant Francophones are in the central area of the CMA: Toronto, Mississauga, Brampton and Newmarket.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.5: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of Canadian-born Francophones in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 167 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 28 tracts, representing 63.1% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 1% and 6.57% of the population.

There are 19 tracts, representing 11.7% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1% of the population.

There are 45 tracts, representing 15.9% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.25% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 75 tracts, representing 11.1% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0% and 0.25% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of Canadian-born Francophones are east of the Red River, as in St. Boniface, and in the south, as in St. Norbert.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.6: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of immigrant Francophones in the Winnipeg census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 170 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 37 tracts, representing 67.3% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 1% and 4.53% of the population.

There are 23 tracts, representing 16.7% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1% of the population.

There are 33 tracts, representing 11.9% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.25% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 77 tracts, representing 4.3% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0% and 0.25% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of immigrant Francophones are on both sides of the Red River, which cuts through the CMA from south to north, including St. Boniface, Fort Richmond in the south, and River East in the north.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.7: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Vancouver census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone population born in Canada in the Vancouver census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of Canadian-born Francophones in the Vancouver census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 453 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 35 tracts, representing 21.9% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1.22% of the population.

There are 173 tracts, representing 53% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.2% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 123 tracts, representing 18.1% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0.1% and 0.2% of the population.

There are 122 tracts, representing 7% of the population of Canadian-born Francophones, in which Canadian-born Francophones account for between 0% and 0.1% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of Canadian-born Francophones lie along an axis running from North Vancouver in the west through Surrey to Langley.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

Map 1.8: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Vancouver census metropolitan area, by census tract

Text version: Percentage distribution of the Francophone immigrant population in the Vancouver census metropolitan area, by census tract

Percentage distribution of the population of immigrant Francophones in the Vancouver census metropolitan area (CMA), by census tract.

The map represents 453 census tracts. It illustrates the distribution of the population grouped into four categories.

There are 53 tracts, representing 35.6% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.5% and 1.24% of the population.

There are 135 tracts, representing 42.6% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.2% and 0.5% of the population.

There are 110 tracts, representing 13.2% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0.1% and 0.2% of the population.

There are 155 tracts, representing 8.5% of the population of immigrant Francophones, in which immigrant Francophones account for between 0% and 0.1% of the population.

The zones with the highest concentration of immigrant Francophones are in North Vancouver and Vancouver proper, extending as far as Coquitlam.

Source(s): Statistics Canada, Census of 2011.

2 Geographic origins of French-speaking immigrants

Where do French-speaking immigrants come from, and has there been a change in the source countries of immigration in recent years? In this report, geographic origin refers to the place of birth (a country, geographic area or continent), since the country of birth is the only information that the censuses and the National Household Survey provide on immigrants’ origins. Three themes are of interest here: origins as such, either immigrants’ country or region of birth; identification with visible minority groups; and the period when they received permanent residence (presumed period of arrival in Canada).

2.1 Country or region of birth

The geographic origin of immigrants has changed substantially in recent decades, as new waves of immigrants from Asia and Africa gradually replaced European immigrants. This trend is observed for immigrant groups defined according to French or English as the first official language spoken (FOLS). However, the immigrant population whose first official language spoken is French only (French FOLS) stands out because the same set of countries, led by France, fed this group in both 1991 and 2011 (Table 2.1). During this period, the same eight countries ranked among the 10 countries that contributed the most to the immigrant population with French as their first official language. In addition to France, there is Haiti, the United States,Footnote 3 Mauritius, Morocco, Belgium, Lebanon and Egypt. In 1991, Italy and Switzerland were part of this group, but they were replaced in 2011 by the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) and Algeria.

As for immigrants with a double official language spoken (French-English FOLS), five of the top 10 countries of origin in 1991 were in Europe (Italy, Poland, Portugal, West Germany and Romania); 20 years later, four of them were still a country of origin. While Romania ranked seventh in 1991, it was in first place in 2011 with 6,300 French-English FOLS immigrants. New—and large—source countries of immigration, such as the People’s Republic of China and India, joined the group of the top 10 countries. The geographic origins of other immigrants (non-francophones) also changed between the 1991 Census and the 2011 NHS. In 1991, the top four source countries were the United Kingdom, Italy, the United States and the reunified Germany, but in 2011, the People’s Republic of China, India and the Philippines climbed into the lead alongside the United Kingdom.

Another characteristic of the geographic origins of French-speaking immigrants is that the top 10 contributing countries account for a large portion of all immigrants in this linguistic group. In 2011, two-thirds of these immigrants came from those 10 countries, compared with 77% in 1991. This decrease in the relative weight of the top 10 immigration source countries in relation to all immigration source countries is due to the diversification of the origins of new immigrants from the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. This trend is also observed in the other two linguistic groups, in which the contribution of Asian countries is much greater. In 2011, 54% of non-francophone immigrants came from the top 10 immigration source countries, compared with 60% in 1991. In the French-English FOLS immigrant group, the corresponding percentages were respectively 40% and 56%.

Table 2.1: Top ten countries of birth for immigrants according to first official language spoken (FOLS) and percentage that the top ten countries represent in relation to the total immigrants in each group, Canada less Quebec, 1991 and 2011

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| FranceTable 2.1 footnote * | 11,225 |

| United States | 4,230 |

| Belgium | 2,700 |

| Haiti | 2,225 |

| Lebanon | 1,740 |

| Mauritius | 1,665 |

| Morocco | 1,640 |

| Egypt | 1,450 |

| Italy | 1,250 |

| Switzerland | 1,235 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 76.8% |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| FranceTable 2.1 footnote * | 16,050 |

| Haiti | 7,220 |

| Congo (Democratic Republic) | 6,380 |

| Mauritius | 3,980 |

| United States | 3,630 |

| Morocco | 3,515 |

| Lebanon | 2,555 |

| Belgium | 2,340 |

| Algeria | 2,025 |

| Egypt | 1,905 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 66.6% |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| Lebanon | 4,045 |

| Italy | 3,780 |

| Poland | 3,095 |

| Portugal | 2,930 |

| Viet Nam | 2,535 |

| Germany (FRG) | 1,830 |

| Romania | 1,780 |

| Hong Kong | 1,605 |

| Iran | 1,485 |

| Egypt | 1,165 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 56.3% |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| Romania | 6,365 |

| China (People's Republic) | 4,520 |

| Lebanon | 4,360 |

| Iran | 3,235 |

| India | 3,125 |

| Colombia | 2,310 |

| Russia | 2,075 |

| Viet Nam | 2,065 |

| Italy | 1,945 |

| Poland | 1,940 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 40.2% |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 691,360 |

| Italy | 267,895 |

| United States | 216,790 |

| Germany (FRG) | 165,305 |

| India | 163,090 |

| Poland | 162,240 |

| China (People's Republic) | 146,275 |

| Hong Kong | 145,700 |

| Portugal | 133,325 |

| Netherlands | 125,390 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 60.4% |

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| India | 527,455 |

| United Kingdom | 521,745 |

| China (People's Republic) | 496,725 |

| Philippines | 430,690 |

| United States | 232,375 |

| Hong Kong | 199,070 |

| Italy | 196,295 |

| Pakistan | 146,240 |

| Germany | 139,505 |

| Poland | 138,375 |

| Top 10 countries represent in relation to the total | 53.6% |

FOLS = Population of groups defined according to first official language spoken. The category 'FOLS other' includes FOLS groups 'English' and 'neither English nor French'.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 Census, and 2011 National Household Survey.

As can be seen in Table 2.1, French FOLS immigrants come from countries where French is either the only official language of the country (France) or one of the official languages (Haiti, Belgium, Switzerland), or from countries where there are French speakers mainly on account of the colonial history of France and Belgium (Mauritius, Morocco, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lebanon, Algeria). The Organisation internationale de la francophonie (OIF) classifies its member countries into two major categories: those for which French is an official language (alone or with other languages) and those for which there are a certain number of French speakers. In total, the OIF has over 50 member states, including Canada. For the following analysis by geographic area of origin, we have added countries with a Romance language other than French to these two groups, since the knowledge of a Romance language (such as Italian, Spanish and Portuguese) tends to make it easier to learn French, also a Romance language. The list of countries in these three groups is provided in Appendix B.

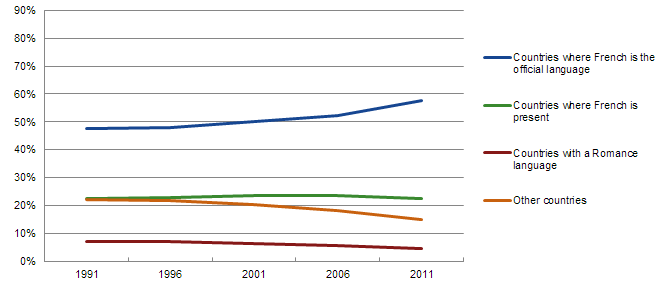

Of francophone immigrants (French FOLS), 58% come from a country where French is the official language (Chart 2.1). This proportion steadily increased between 1991 and 2011. Just under 25% came from countries where French is present, and a smaller percentage (less than 10%) from countries with a Romance language (other than French). There was little change between 1991 and 2011 in the distribution of the immigrant population by geographic area of origin based on the status of French in the country (with a distinction made for countries with a Romance language other than French). However, the period between 2006 and 2011 is an exception, since it was characterized by an increase of more than five percentage points in the number of immigrants from countries where French is an official language, while the other three groups saw a decrease in percentage. Approximately 50% of immigrants with a double official language (French-English FOLS) come from countries where French has no status or where the official language is not a Romance language other than French. However, immigrants from countries where French is present (but without official status) constituted 30% of the French-English FOLS group between 1991 and 2011, while 17% came from Romance-language countries. This latter percentage declined during the period in question, except between 2006 and 2011, when a slight increase is observed. The majority of non-francophone immigrants came from non-francophone and non-Latin countries. Less than 1% of them came from a country where French is an official language, and 7% from a country where French is present.

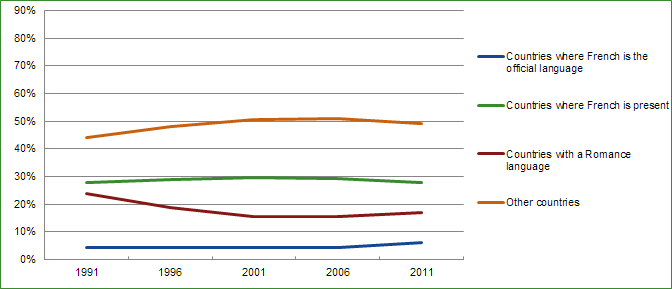

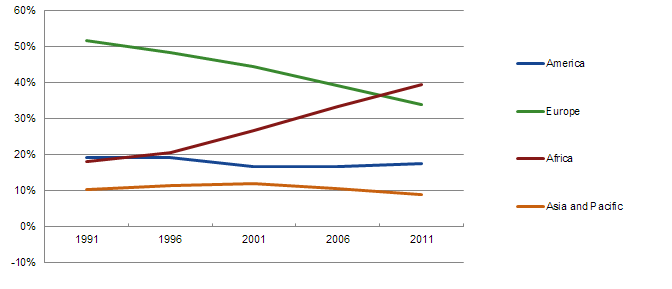

As previously mentioned, the main change observed in recent decades was a considerable reduction in the proportion of immigrants born on the European continent. This trend prevailed in all three groups defined by first official language spoken. For each group, the relative weight of European immigrants decreased between 1991 and 2011, from approximately 50% to less than 35% (Charts 2.2-a, b, c).

The trend for both French-English FOLS immigrants and non-francophone immigrants was marked by a steady increase in the proportion of immigrants from Asia and the Pacific region (from 20% to nearly 50%) and by a slight increase in the proportion of immigrants from the Americas and Africa (approximately 20% of all immigrants in 2011). The sub-population of French FOLS immigrants stands out from the other sub-populations. The weight of Europeans has naturally decreased, but this decrease was mainly in favour of immigrants from Africa. In 1991, Africans accounted for 20% of all French-speaking immigrants, and that percentage steadily rose to close to 40% in 2011, six percentage points more than at the time of the 2006 Census. During the same period, immigrants from Asia, the Pacific region and from the Americas saw their relative share decrease slightly.

Chart 2.1: Percentage of immigrants with first official language spoken (FOLS) according to country of origin, Canada excluding Quebec, 1991 to 2011

Immigrants French FOLS

Text version: Immigrants French FOLS

| Category | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries where French is the official language | 48% | 48% | 50% | 52% | 58% |

| Countries where French is present | 23% | 23% | 23% | 23% | 23% |

| Countries with a Romance language | 7% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 5% |

| Other countries | 22% | 22% | 20% | 18% | 15% |

Immigrants French-English FOLS

Text version: Immigrants French-English FOLS

| Category | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries where French is the official language | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 6% |

| Countries where French is present | 28% | 29% | 29% | 29% | 28% |

| Countries with a Romance language | 24% | 19% | 16% | 15% | 17% |

| Other countries | 44% | 48% | 51% | 51% | 49% |

Other immigrants

Text version: Other immigrants

| Category | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries where French is the official language | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Countries where French is present | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% |

| Countries with a Romance language | 15% | 13% | 12% | 11% | 10% |

| Other countries | 78% | 79% | 80% | 81% | 82% |

The category ‘FOLS other’ includes FOLS groups ‘English’ and ‘neither English nor French’.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

Chart 2.2: Percentage of immigrants with first official language spoken (FOLS) according to continent of birth, Canada excluding Quebec, 1991 to 2011

Immigrants French FOLS

Text version: Immigrants French FOLS

| Continent | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | 19% | 19% | 17% | 17% | 17% |

| Europe | 52% | 48% | 44% | 39% | 34% |

| Africa | 18% | 21% | 27% | 33% | 40% |

| Asia and Pacific | 10% | 11% | 12% | 11% | 9% |

Immigrants French-English FOLS

Text version: Immigrants French-English FOLS

| Continent | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | 8% | 9% | 8% | 10% | 14% |

| Europe | 49% | 44% | 43% | 39% | 33% |

| Africa | 8% | 11% | 10% | 11% | 14% |

| Asia and Pacific | 35% | 36% | 39% | 40% | 39% |

Other immigrants

Text version: Other immigrants

| Continent | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | 15% | 15% | 15% | 14% | 14% |

| Europe | 55% | 48% | 42% | 37% | 31% |

| Africa | 3% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| Asia and Pacific | 26% | 34% | 39% | 44% | 49% |

The category ‘FOLS other’ includes FOLS groups ‘English’ and ‘neither English nor French’.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991 to 2006 censuses, and 2011 National Household Survey.

2.2 Visible minority groups

As a result of the steady growth of the immigrant population from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, the proportion of immigrants designated as visible minorities has increased. French FOLS and French-English FOLS immigrants are no exception to this trend (Table 2.2). Of the 74,500 French FOLS immigrants in 2011, more than half (55%) are classified as belonging to a visible minority. Within this group, the majority “identify” with the Black group, which makes up 34% of all French FOLS immigrants, compared with 26% in 2006. The other visible minority groups each accounted for less than 3% of the total in 2011, except for the Arab group, which represented 8% of the French FOLS immigrant population classified as a visible minority in 2011.

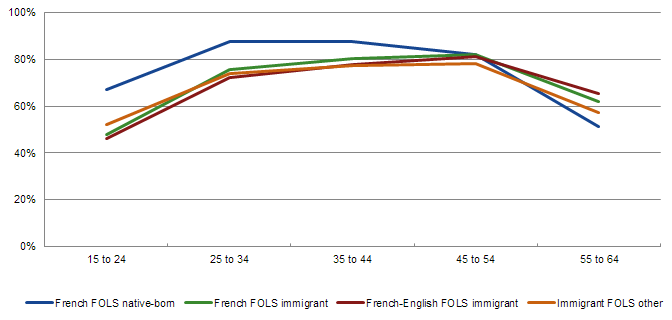

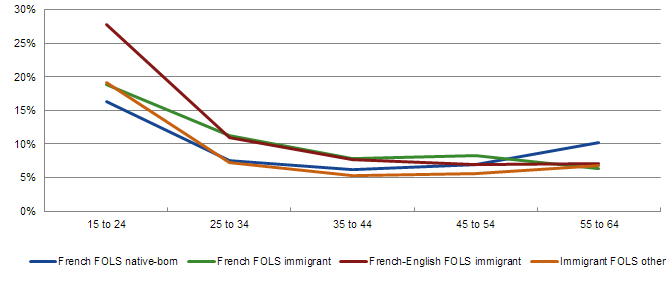

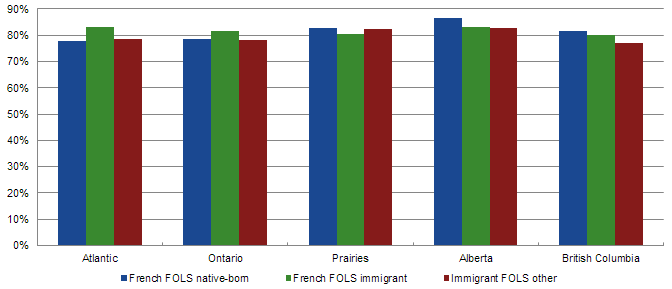

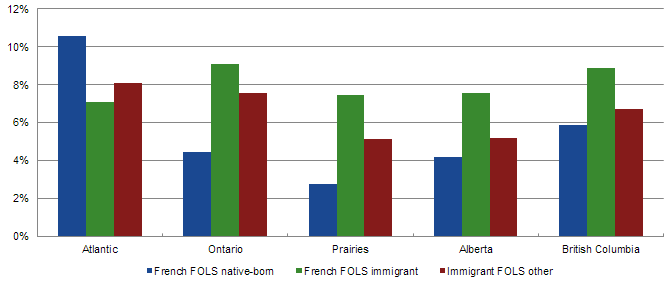

The French-English FOLS group has few Blacks (6.7%), but comprises more Asians, especially from East Asia (China, Korea, Japan) and South Asia (India, Pakistan, etc.). In all, 30.5% of French-English FOLS immigrants belonged to the group consisting of visible minorities of Asian origin, compared with less than 9% of French FOLS immigrants.