Guidance: Assessment of Potential Impacts on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Our website is undergoing significant changes to provide updated guidance on the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada's practice on the application of the Impact Assessment Act and its regulations. This webpage and its contents may not reflect the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada's current practices. Proponents remain responsible for following applicable legislation and regulations. For more information, please contact guidancefeedback-retroactionorientation@iaac-aeic.gc.ca

Purpose

This document provides guidance on the methodology for assessing potential impactsFootnote 1 on the rights of Indigenous peoplesFootnote 2 as required in an impact assessment of a designated project under the Impact Assessment Act (IAA). For clarity, this guidance applies to all impact assessments conducted in accordance with the IAA, including designated projects including physical activities that are regulated under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (NSCA) or the Canadian Energy Regulator Act (CERA). The concepts in this guidance is also applicable to regional and strategic impact assessments conducted under the IAA.

Acknowledgements

The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (the Agency) would like to acknowledge the Indigenous people and organizations who have participated in federal environmental assessments over the past few decades and whose contributions have been instrumental in the evolution of federal assessment practices.

The shared experience and work invested by Indigenous peoples in the course of federal environmental assessments have helped the Agency in its efforts for continuous improvement in federal assessments and Canada-Indigenous relationships, and have collectively influenced the concepts in this guidance.

How to use this guidance

This guidance should be interpreted and applied in conjunction with the guidance contained in other sections of this guide. In particular, the reader should refer to the Policy Context: Assessment of Potential Impacts on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples under the Impact Assessment Act, in section 3.3 of the Practitioner’s Guide. The policy context provides important information on guiding principles that should be referenced to support the interpretation and application of the technical guidance in this section.

This guidance is also intended to be consistent with the guidance provided in other sections of the Practitioner’s Guide. In particular, consulting and collaborating with Indigenous peoples is a key component of assessing impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Guidance on the process for consultation and collaboration with Indigenous peoples in federal impact assessments can be found in the following sections of the Practitioner’s Guide:

- 3.1. Policy Context: Indigenous Participation in Impact Assessment

- 3.2. Guidance: Indigenous Participation in Impact Assessment

- 3.5. Guidance: Collaboration with Indigenous Peoples in Impact Assessment

Contents

The content of this guidance is organized into three parts. Part 1 presents the methodology for assessing impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Part 2 explains criteria that can be used in the analysis to understand and evaluate the impacts. Part 3 focuses on how to develop measures to prevent or address adverse impacts and also covers post-assessment follow-up and monitoring.

Roles and Responsibilities

The Agency is responsible for conducting or administering impact assessments under the IAA, and for coordinating consultations with Indigenous groups that may be affected by a designated project.Footnote 3

An assessment of potential impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples will typically require cooperation between the rights-holding Indigenous community, the proponent of the designated project, the Agency, other federal authorities, and, in many cases, the government of another jurisdiction. The roles and responsibilities of each party may vary from one impact assessment to another, depending on the circumstances.

If an Indigenous communityFootnote 4 is interested in doing so, they should lead the assessment of impacts on their rights as they are best placed to understand how their rights and their relationship with the landscape may be impacted by the project. In such cases, the Agency would work with the Indigenous community on the assessment while coordinating the process with other federal authorities and the proponent, as needed.

Other federal authorities have an important role to play in contributing technical information or knowledge within their mandate to inform the assessment of potential impacts flowing from the project. Other federal departments should be involved in the assessment process as early as possible, in order to contribute to the early identification of issues and to provide advice within their mandate on the assessment approach, the evaluation of potential impacts, and the development of potential mitigation and/or accommodation measures.

The proponent’s role is to provide information about their project and participate in discussions as the assessment of impacts on rights progresses throughout the impact assessment process. The proponent is responsible for undertaking studies and preparing the impact statement as required by the Tailored Impact Statement Guidelines (the Guidelines) for the project, and is encouraged to work collaboratively with the potentially affected Indigenous communities in this work. As the owner and designer of the project, the proponent’s participation in the assessment of impacts on rights is also important for developing possible mitigation measures.

All parties have a responsibility to find ways to address concerns about how a project may adversely impact the exercise of rights of Indigenous peoples.

For impact assessments of projects that have been substituted to other jurisdictions under section 31 of IAA, this guidance should be used to the extent appropriate within the assessment process of the other jurisdiction. The jurisdiction that is carrying out the impact assessment is expected to work with potentially impacted Indigenous communities on assessing impacts on their rights, and to work with the Agency as needed to coordinate consultations with Indigenous peoples and the federal Crown.

Terminology

Key terms used throughout this guidance are explained below:

Impact assessment practitioner: For the purposes of this guidance, the term "impact assessment practitioner" is used to refer to anyone working on the assessment of impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. It can include federal government officials, provincial government officials, Indigenous community representatives, proponents, consultants, review panel members, regional assessment committee members, or others working on the assessment.

Impacts: For the purposes of this document, unless otherwise specified, "impacts" refers to potential impacts that may result from a proposed project or physical activity.

Pathway: An impact pathway is a representation, often diagrammatic, of a linked set of cause-and-effect relationships between factors in the analysis such as effects, actions, outputs, and/or outcomes.

Rights of Indigenous peoples: Throughout this document, "rights of Indigenous peoples" and "rights" refer to the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada, as recognized and affirmed in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, consistent with the IAA. The IAA requires that the impact assessment of a designated project must take into account, among other factors, "the impact that the designated project may have on any Indigenous group and any adverse impact that the designated project may have on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 (Section 22(1)(c))."

Part 1: Methodology

This section provides guidance on steps for undertaking an assessment of potential impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. In cases where an Indigenous community has developed its own protocols for consultation and/or methodology for assessing impacts on their rights, this guidance should be adapted to respect those protocols and methodologies on a case-by-case basis, in collaboration with the community.

An assessment of potential impacts on rights is a complex undertaking with considerable potential for variation. The methodology is intended to be flexible and to be adapted as needed, based on context. Each assessment of impacts on rights will be unique, tailored to the particular Indigenous rights-holding community, specific project, specific area or location, and timing.

The federal impact assessment process aims to predict potential adverse impacts before they occur, and can identify potential positive outcomes, including measures that could improve the underlying baseline conditions supporting the exercise of a right. To be effective, the process requires ongoing information sharing and collaboration between the impact assessment practitioner and the Indigenous community. It is important to validate understanding and findings throughout the process. Within each step outlined below, there are sub-steps, and many of these sub-steps may need to be repeated.

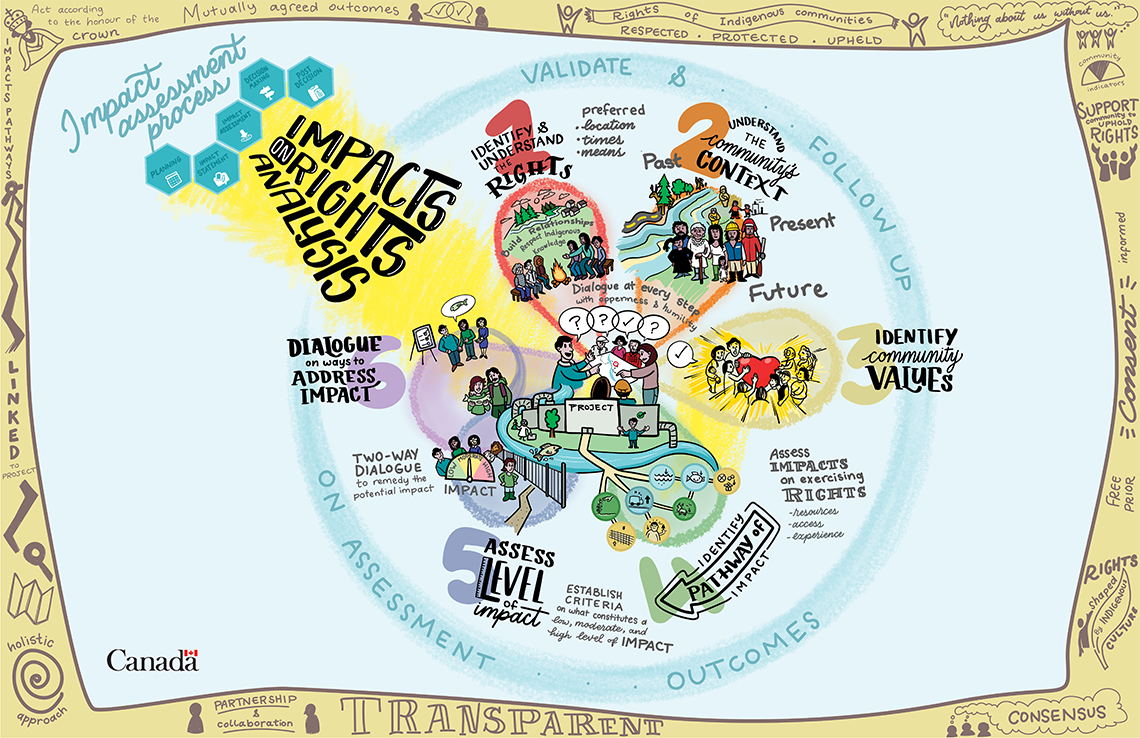

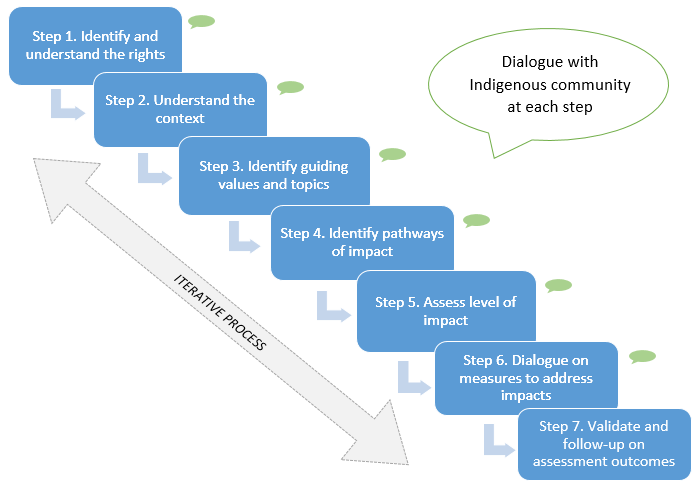

Overview of the Methodology

Impact assessments on the rights of Indigenous peoples can be broken down into seven steps. The following section describes each step in detail.

Step 1: Identify and understand the rights of the Indigenous community

- Identify and work together to understand the nature and content of the rights of the Indigenous community. Indigenous peoples are best placed to identify a project’s impacts on their rights.

Step 2: Understand the context in which impacts on rights would occur

- Identify the environmental and socio-economic conditions that support the community’s meaningful exercise of their rights.

- Understand how historic, existing and reasonably foreseeable future activities have cumulatively affected or could affect the conditions that support or limit the Indigenous community’s meaningful exercise of their rights.

- Identify the importance of specific areas or locations that are important to the community and may be impacted by the project.

Step 3: Identify guiding values and topics (what to assess)

- Often referred to as “valued components” with respect to biophysical assessments, Indigenous communities may identify a set of priority values and topics associated with community well-being, cultural expression, and the preferred means of exercising their rights.

Step 4: Identify pathways of impact from the project

- Identify pathways from project-related activities to the biophysical environment that supports the exercise of rights.

- Identify other relationships between the project and the conditions needed to exercise rights, such as access, quality, and quantity of resources, or the quality of experience of exercising the rights. Impacts to the exercise of a right in preferred locations, at preferred times, and by preferred means should be assessed.

Step 5: Assess level of the impact

- Establish clear criteria with input from the rights-holding Indigenous community on what constitutes a low, moderate, or high level of impact.

Step 6: Dialogue on measures to address impacts

- For impacts that are likely to occur, ensure that an iterative two-way dialogue takes place on measures proposed to address the impact.

Step 7: Validate and follow-up on assessment outcomes

As the impact assessment process unfolds, these steps can be revisited and analysis can be revised based on new information and continued dialogue between all parties.

Steps of the Methodology

This section provides detailed guidance on how to undertake each step of the assessment of potential impacts on rights in consultation with the potentially affected Indigenous community.

Step 1: Identify and understand the rights of the Indigenous community

Protection of Confidential Information

Transparency and public participation are important aspects of impact assessment. For federal impact assessments, information is made available and accessible to the public on the the Registry, unless subject to valid exceptions set out in legislation.

When collecting information for the assessment of impacts on rights, the impact assessment practitioner should note whether the information is already publicly available, and if not, if it is confidential and requires protection. The Agency can provide advice on the protection of information in the impact assessment process.

The first step in assessing how a project may impact the exercise of rights of a particular Indigenous community is to identify and understand the rights that are held by that community.

A respectful relationship based on the recognition and implementation of rights requires that the impact assessment practitioner has, as a starting point, a working-level knowledge of the rights of the potentially affected Indigenous community. The impact assessment practitioner should begin by gathering existing available information about the rights of the specific community, which may exist in documentation such as treaties, agreements, previous environmental or impact assessments, consultation records, research, and/or statements by the community. The Agency also encourages impact assessment practioners to spend time at the outset to establish a relationship with each potentially affected Indigenous community, if the impact assessment practitioners have not already done so or are not a member of that Indigenous community.

Consistent with a respectful and recognition-based dialogue about the rights of Indigenous peoples, information provided by the rights-holding Indigenous community about their rights and how the community exercises its rights should be accepted by the impact assessment practitioner as the basis for dialogue. In some cases, the rights held by a community may be well understood by all parties. In other instances, there may be uncertainty due to lack of information, differing interpretations, overlapping claims, or other factors. In the event of uncertainty or disagreement, it is important to note that the impact assessment process is not a rights determination process. The objective is to identify and understand the activities and resources that are necessary for the Indigenous community to exercise its rights and to then evaluate how those activities and resources might be impacted by the project, in order to protect the ability to exercise rights. While analysis of strength of claim by the Crown may be necessary when considering potential accommodation in accordance with the duty to consult, rights as described by the Indigenous community can be accepted for the purpose of dialogue and analysis in the impact assessment process.

In the event of ambiguity or disagreement about the rights held by an Indigenous group, the impact assessment practitioner should seek the advice of the Consultation and Accommodation Unit at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada via the Agency.

Federal officials are expected to gather existing federal knowledge about the rights of the Indigenous community and the community’s relationship with the Crown. This may require requesting information on recent developments from other federal departments and agencies, and can be facilitated by the maintenance and sharing of organizational consultation records and community profiles. Impact assessment practitioners in the private sector are encouraged to contact the Agency to seek advice and direction to assist them in identifying and accessing appropriate sources of information about the rights of an Indigenous community.

Following initial research and information-gathering, discussions with each Indigenous community can progressively build an understanding of the nature, scope and content of each right, including how a right (or suite of rights) may be exercised, the geographic extent of the traditional territory, and the purpose and importance of the right(s) to the rights-holding community. It is important to note that Indigenous communities may not use the term “rights” to refer to the practices, customs, beliefs, or worldview that underpin important ways of life. Nevertheless, their long-standing connection to, use of, or occupation of an area is indicative of their rights.

Once the impact assessment practitioner has a working-level understanding of the rights of the potentially affected Indigenous community, substantive consultation with the community can begin to verify information that has already been compiled in relation to the project, such as baseline biophysical information. The initial focus should be on information sharing and dialogue to refine and/or adjust the impact assessment practioner’s understanding of the nature of the rights, including how they are exercised in a given area. The desired outcome of this initial dialogue is to reach a common understanding of the rights of the Indigenous community that could be impacted by the designated project.

Step 2: Understand the context in which impacts on rights would occur

The next step in assessing impacts on the exercise of rights is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the contextual factors relevant to consider in the assessment, conducted in consultation with the rights-holding community. Broadly speaking, this entails reviewing information about the conditions necessary to allow a community to exercise its rights and how historical and current cumulative effects may already impact those conditions, or how future foreseeable projects may have an impact. It then requires an evaluation of how the project area and the resources in and around the project are faring related to the exercise of rights by the community.Footnote 5

An important part of this analysis is understanding the lands, waters, and resources necessary to support the meaningful practice of rights, and the relationship that the Indigenous community has with these resources that may be affected by the project.

(a) Identify the environmental and socio-economic conditions that support the community’s meaningful exercise of their rights

The next step is for the impact assessment practitioner to develop an understanding of the conditions and context required by an Indigenous community to support the meaningful practice of rights. It is vital that there be engagement with and direction from the Indigenous community in understanding the conditions that are required for the practice of rights. This engagement should be appropriate to the Indigenous community, and should seek to include all appropriate sectors of the community to ensure that differential impacts from the project are captured in the assessment.

Types of conditions that the impact assessment practitioner should consider include:

- the state of the land base (including biodiversity, ecosystem health, connectedness of tracts of land or waterways, etc.);

- ancestral connection, a feeling of historical or spiritual connection to the area;

- confidence in and sufficiency of resources (including higher weighting for preferred places, resources and times to access them);

- data on wildlife and vegetation baseline (abundance, distribution, population health) data;

- sense of place (e.g., sense of solitude and ability to peacefully enjoy territory in preferred manner);

- customs for transfer of knowledge (including language) to future generations;

- access and patterns of occupation and cultural practice (including community constraints and differential cultural practices by age and/or gender);

- stewardship norms and laws;

- social value of the area to practice culturally significant activities;

- cultural landscape and keystone cultural place delineation; and

- community health indicators using a social determinants of health approach.

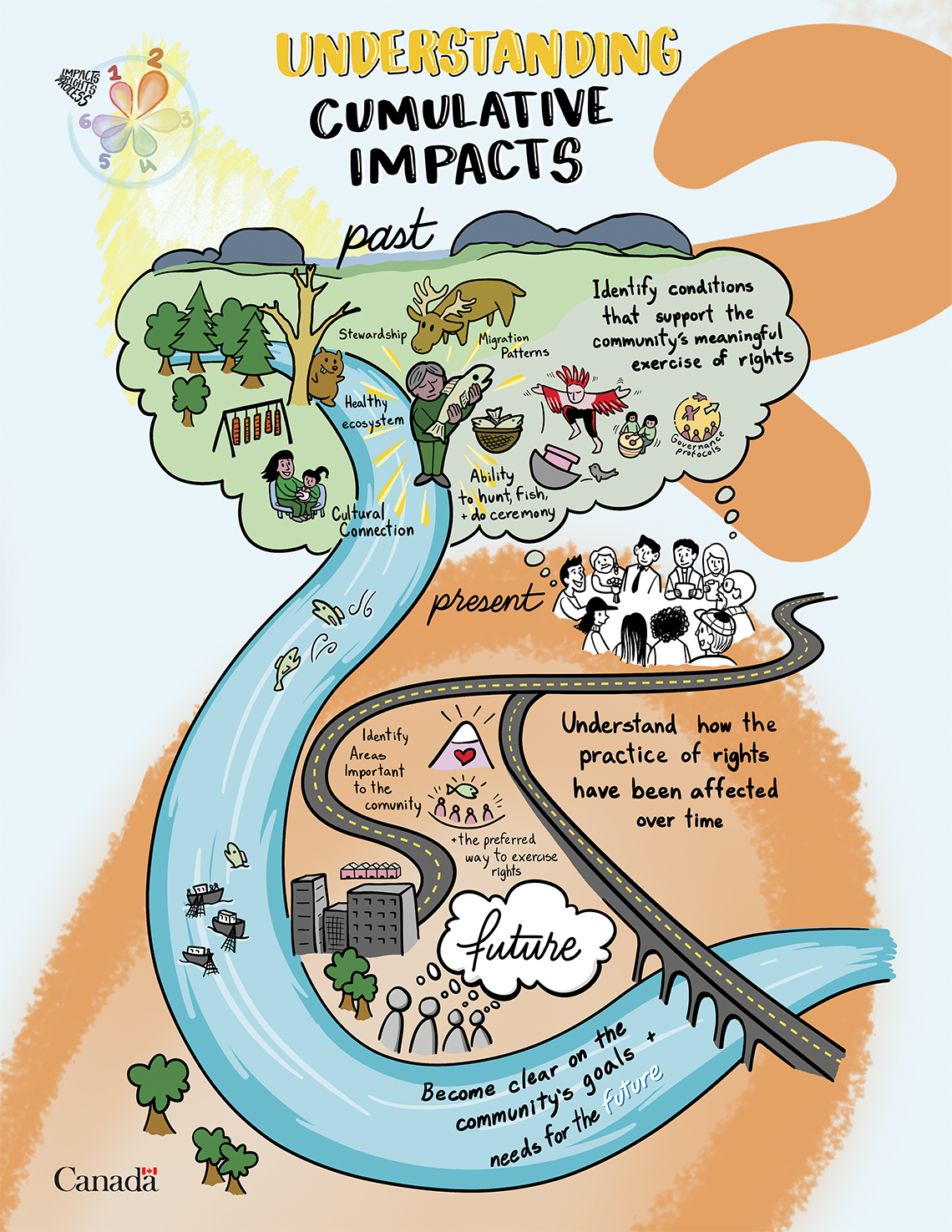

(b) Understand how historic, existing and reasonably foreseeable future activities have cumulatively affected or could affect the conditions that support or limit the Indigenous community’s meaningful exercise of their rights

Once the impact assessment practitioner understands the types of environmental, cultural, social and economic conditions needed to support the exercise of rights, the next step is to evaluate how current environmental and socio-economic conditions, including changes in those conditions, may be constraining or supporting a community’s ability to exercise its rights. Determining this will establish the state of the particular right as exercised and identify cumulative impacts on the exercise of a right. Establishing the context of existing cumulative impacts must be completed before considering project-specific impacts.

A preferred approach to evaluating this context is to obtain an understanding of a community’s view of a temporal period when there were good conditions for the exercise of rights (and what that looked like) as a baseline for assessment, and then compare current conditions for the exercise of rights with those previous conditions and any community-defined thresholds. Community-defined thresholds can be based on social perception scales, constructed scales, existing socially -defined thresholds (such as land use plans or articulations of desired futures) or thresholds established through a jointly defined approach.

(c) Identify the importance of specific areas or locations that are important to the community and may be impacted by the project.

The impact assessment practitioner should work with the Indigenous community to map out how the project and its components could interact with their traditional territory. Note that there does not necessarily have to be direct overlap of the project with reserve lands; a community’s traditional territory is the geographic area in which their rights are practiced. The practice of rights can be fluid and may change with seasons, species, cultural protocol and a number of other factors. Work should be done with the Indigenous community and the proponent to discuss how the landscape could change because of the project and identify what that means in terms of changes within the Indigenous community’s territory.

The following considerations may help the impact assessment practitioner identify the importance of a particular geographic area to an Indigenous community:

- it is located within the Indigenous community’s traditional territory;

- the Indigenous community says the area is important;

- the occurrence of many place names within the project area;

- the intensity and frequency of traditional and cultural uses in the area;

- the diversity of traditional and cultural uses and experiences in the area;

- the uniqueness of the particular area to the cultural practices;

- the role that the location holds in trade and cultural exchange; and

- the role the place holds in the community’s history and culture.

Step 3: Identify values or topics of importance to use as indicators for the assessment of impacts on rights

In this step, the impact assessment practitioner and the Indigenous community should work together to select appropriate values or topics that could be used as indicators for the assessment of impacts on the exercise of rights. This step is similar to the identification of valued ecosystem components in environmental assessment practice. However, for the assessment of impacts on rights, the indicator need not necessarily be a component of the ecosystem. The values or topics of importance that could serve as indicators could include: a specific practice associated with exercising a right; a culturally defined value; a culturally important species; or important cultural landscapes. It must be possible, however, to apply an appropriate method to assess how the project could affect the selected indicator and what those effects on the indicator would mean for the exercise of rights.

Key discussion points to guide the impact assessment practitioner’s work with each Indigenous community in identifying appropriate indicators could include:

- connection of the project area to preferred areas for the exercise of rights;

- relationship of the project to changing or diminishing access to preferred areas;

- preferred or important species in and around the project area,

- the relationship of affected habitat to the well-being of a particular species;

- relation of an affected area to community stewardship vision;

- depth level of concern by the Indigenous community; and

- representation of Indigenous people that value the place for the range of activities and values.

Step 4: Identify pathways of impact from the project

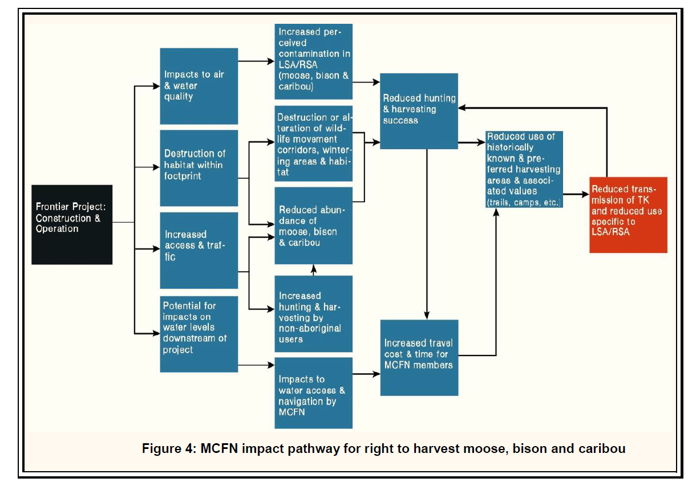

The objective of Step 4 is to identify and describe the pathways by which the project may affect the exercise of rights by the Indigenous community.

The impact assessment practitioner should consider the major impact pathways identified for the project. This should include an initial description of changes to the environment as a result of the project and how they create changes to the exercise of rights. When developing impact pathways, it is very important to consider both tangible values (e.g., wildlife species or traditional plants) and intangible values (e.g., quiet enjoyment of the landscape or sites used for teaching). Intangible values are often linked with spiritual, artistic, aesthetic, and educational elements that are often associated with the identity of Indigenous communities.

The use of visual tools to illustrate pathways is helpful in describing and contextualizing both effects to the environment and identified impacts to the exercise of rights. For example, Figure 1 (labelled Figure 4 in source material) shows an impact pathway for right to harvest moose, bison and caribou that was developed by Mikisew Cree First Nation (MCFN) for the assessment of impacts on their rights caused by the Frontier Oil Sands Mine.

Figure 1: Mikisew Cree First Nation impact pathway for right to harvest moose, bison and caribou

Step 5: Assess level of severity of the impact

The objective of Step 5 is to assess the level of severity of the impacts that the project may have on the exercise of rights. The evaluation of severity should include an assessment of the likely severity of impacts without any mitigation measures, as well as with proposed mitigation measures. As with other steps in the assessment of impacts on rights, an iterative approach should be taken to evaluating the severity of impacts; it may be necessary to update the evaluation as new information becomes available and/or as new mitigation measures are proposed.

The following are some criteria to consider when analyzing the severity of impacts on each value and/or right that is being assessed:

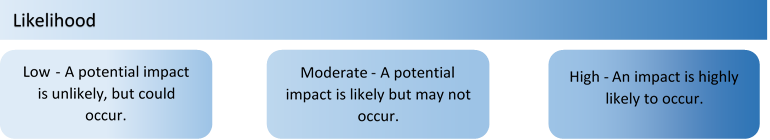

- Likelihood: Estimate how probable it is that the impact will occur.

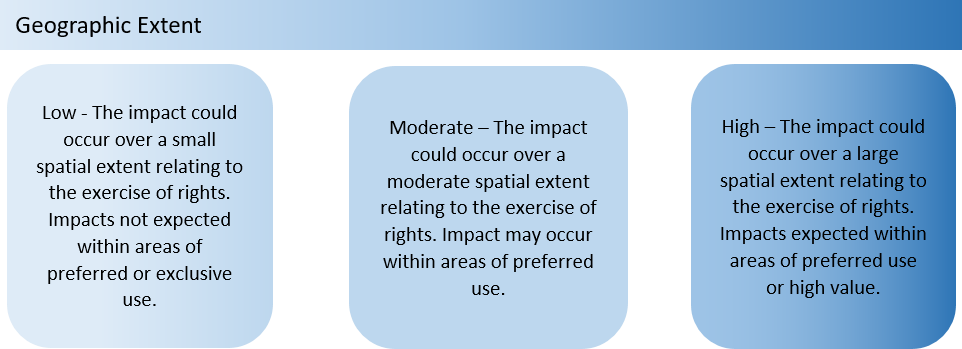

- Geographic extent: Consider the geographic extent of the impacts in relation to the geographic extent of the right, as practiced.

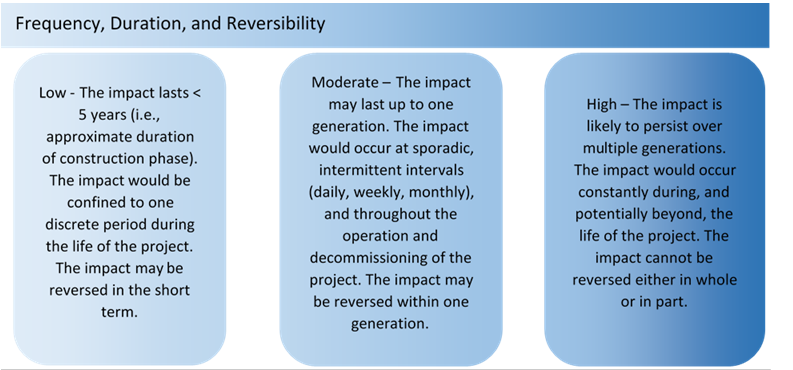

- Frequency, duration and reversibility: Consider how often the impact may occur within a given period of time, the length of time that an impact may be discernible, and whether the exercise of rights is expected to recover from the impact

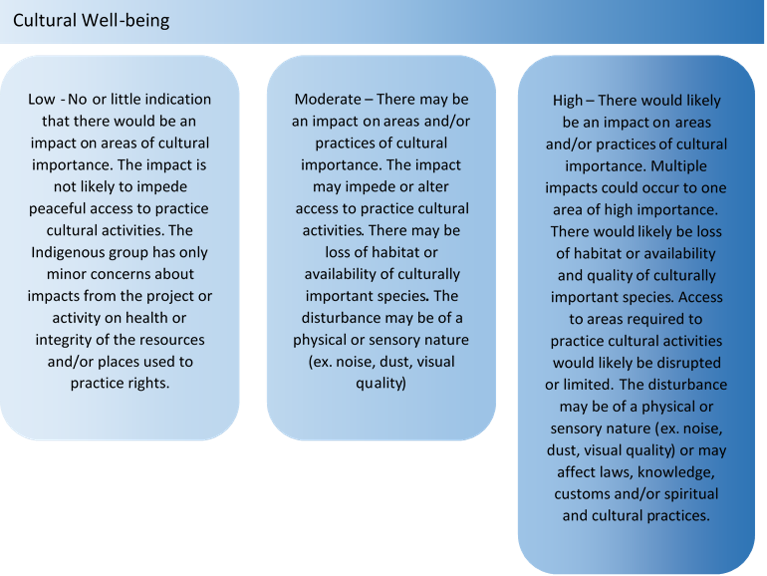

- Cultural well-being: Consider what the impacts of the project are on the ability of a group to continue customs, traditions and practices that are integral to the group’s distinct culture.

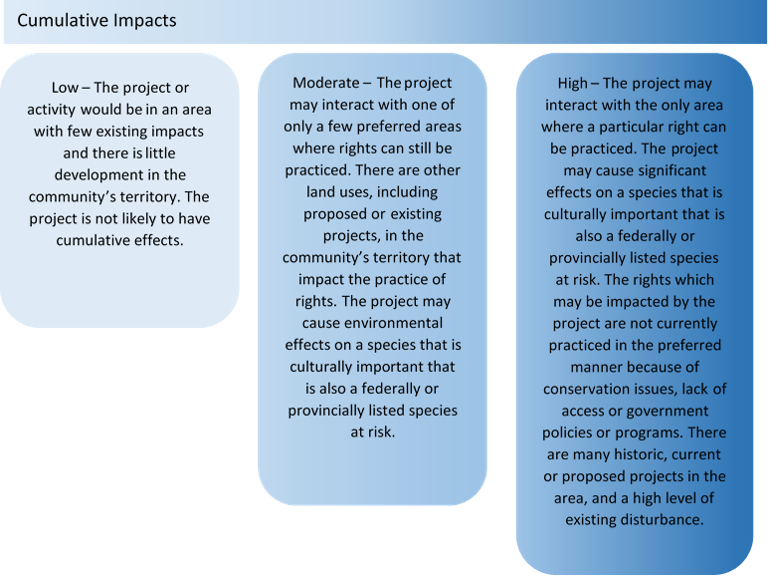

- Cumulative impacts: Identify and understand the degree to which the existing exercise of rights may be more or less vulnerable to the effects of the project when the effects are added to, and interact with, the baseline conditions, including existing cumulative effects from other sources.

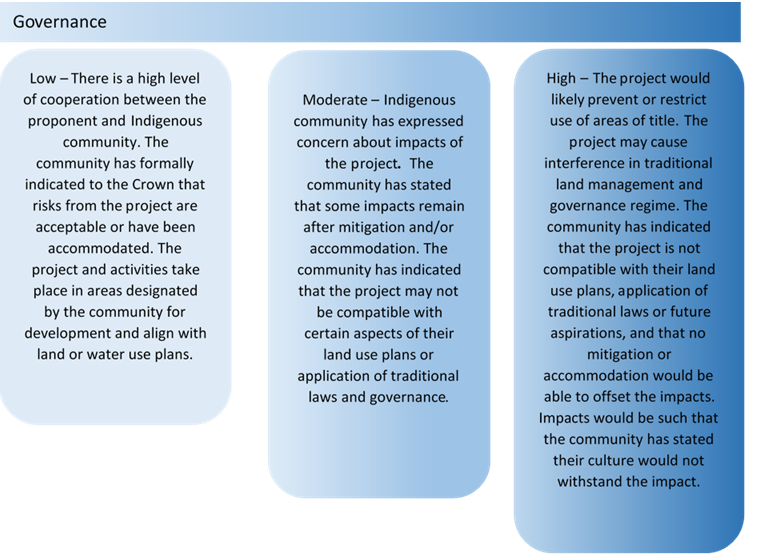

- Governance: Consider whether the effects of the project will affect the community’s ability and systems for self-governance and self-determination with respect to their members (including future generations) and for the management of traditional lands and resources, taking into consideration the laws, customs and structures of the community (including consideration of Aboriginal title);

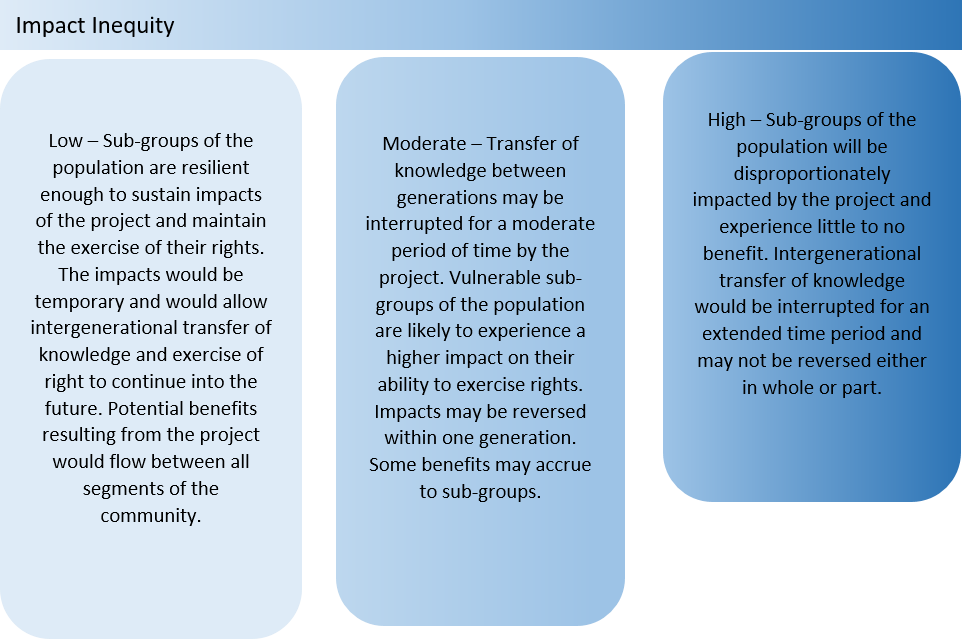

- Impact inequity: Consider the impacts on sub-populations of a community (including women, elders, youth, Two-Spirit individuals, and others) with consideration of risks and benefits for members of the sub-population, and likely resiliency of the sub-population to negative impacts; and

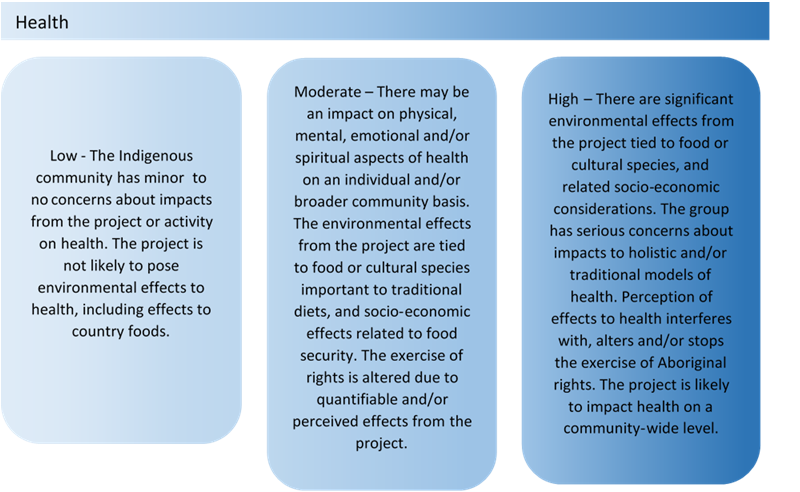

- Health: Consider impacts from the project on the health of the Indigenous community as a whole, or to the health of individual members. Health includes considerations of physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health.

Undertaking sufficient analysis in Steps 1-4 will help prepare the impact assessment practitioner and the Indigenous community to consider these dimensions in the assessment of the severity of impacts.

Additional guidance on how to consider and evaluate each of the dimensions listed above, with suggested criteria to assist with determining severity of impact for each, is provided in Part 2, below. The selection and application of criteria should be informed by input from the rights-holding Indigenous community as detailed in Steps 1-4. A best practice would be to co-develop the criteria with the community.

When considering the severity of a project’s impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples at this step, the impact assessment practitioner should take into consideration any measures proposed to avoid, mitigate or compensate for the impacts identified (measures could include mitigation measures, complementary measures, and/or accommodation measures). This analysis should also take into account the views of the Indigenous community with respect to the proposed measures (i.e. with respect to the appropriateness and likely effectiveness of the measures to address the impact). This step should consider that there is the potential for a scenario whereby no measures are available to reduce or avoid a potential impact on the exercise of rights.

Accommodation, Mitigation, and Complementary Measures

Accommodation, mitigation and complementary measures share a common aim: to avoid, minimize, or compensate for potential adverse impacts that may result from a project. The distinction between the different types of measures is the scope and legal basis of each.

Accommodation refers specifically to a measure to avoid, minimize or compensate for adverse impacts on rights that is owed based on the Crown's duty to consult. Accommodation is part of the duty to consult, grounded in the constitutional obligations of the Crown, and is not limited to the impact assessment process.

Mitigation refers more generally to modifications or additions to a project that are proposed in the course of an assessment in order to avoid or reduce a potential adverse impact (of any type, not necessarily on rights).

Complementary measures are not part of the project, but that are proposed to offset or compensate for adverse effects of the project.

The types of measures are not mutually exclusive. Both mitigation and complementary measures could potentially be accommodation.

The impact assessment process allows for discussion of positive impacts from projects, as well as adverse impacts. Indigenous communities are encouraged to work with proponents and the Agency to identify positive impacts from the project. This could include measures to restore and remediate previously disturbed environments or resources to allow for future harvesting or use by Indigenous communities, economic or social benefits, or any other positive outcome that could contribute to the improved exercise of rights.

Step 6: Dialogue on measures to address impacts

One of the goals of the federal impact assessment system is to foster sustainability. This can include working together with participants in a specific impact assessment to find mutually agreeable solutions to concerns raised about a project, including concerns raised by Indigenous peoples about impacts on their rights. This is an iterative process that can begin as Indigenous communities identify issues in the Planning phase of the impact assessment and should continue all the way through to monitoring and follow-up, should the project be approved to proceed.

Participants working through the impacts on rights assessment should discuss solutions once there is agreement that a project may intersect with the exercise of rights and result in an adverse impact. Under the IAA, mitigation measures include means to eliminate, reduce, control or offset the adverse effects of a project, and include restitution for any damage caused by those effects through replacement, restoration, compensation, or any other means that can address adverse impacts on rights.

Addressing impacts on rights can include a variety of options, such as project design changes, federal conditions, and Crown programs, plans, and policies. The Agency may consider negotiations between the proponent and Indigenous communities when assessing impacts on rights, if the Indigenous community gives explicit direction to the Agency to do so.

As part of the whole-of-government approach to consultation with potentially affected Indigenous communities, federal departments can use complementary measures to help address impacts on rights that cannot be directly addressed through conditions pursuant to an impact assessment Decision Statement. Complementary measures stem from authorities of federal ministers or federal programs outside of the impact assessment process.

Indigenous communities understand their territory and the exercise of their rights the best, so it is important to involve Indigenous communities early in discussions about solutions to address impacts on rights. Solutions proposed by the Indigenous communities should be explored first, and if they are not possible, reasons should be provided to the Indigenous community.

Step 7: Validate and follow-up on assessment outcomes

It is a best practice to consult with the rights-holding Indigenous communities prior to completing the evaluation and finalizing conclusions about the severity of impacts on rights. The Indigenous community should have the opportunity to comment on the content of the assessment, in particular the application of Indigenous knowledge, values, and thresholds. This validation can help to strengthen the analysis and improve the validity and accuracy of the conclusions. The goal is for all parties to agree upon the conclusions based on a collaborative assessment. However, it is possible that parties will not agree. In such cases, all perspectives and rationales for different conclusions should be documented in the assessment report.

Consultation and collaboration with an Indigenous community throughout the process of assessing impacts on their rights is encouraged where and to the extent feasible, such that follow-up and validation may be integrated with each step of the methodology.

Methods

Similar to tools in a toolbox, there are a variety of methods for data collection and analysis that an impact assessment practitioner can use as part of the assessment of impacts. Each method will have its own set of valued components and indicators, and will have its own benefits and limitations with respect to how it can be used to describe and assess impacts on the exercise of rights. The choice of appropriate methods will depend on the nature of the rights, how the rights are exercised, the impacts, the pathways of impact, and the relevant contextual factors.

In the literature and documentation of the practice of impact assessment, there is a broad range of methods that have been used to assess impacts on rights. Good practice is to have the input or collaboration of the rights-holding community on the selection of methods. Employing a combination of different methods and involving a range of types values (indicators to measure) will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the range of potential impacts. Each method has its own set of steps, tools, and rules, and an impact assessment practitioner undertaking the assessment of impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples needs to be familiar with a range of established methods in order to select and employ the appropriate method(s) for a particular assessment.

Part 2. Criteria for determining the severity of impacts

Part 2 provides guidance on how to interpret and apply criteria when evaluating the degree to which the rights of Indigenous peoples may be adversely impacted by a project. The assessment of the severity of impacts should be done collaboratively with each Indigenous community, recognizing that the criteria provided in this guidance is a starting point for dialogue. Other ways of assessing impacts on rights may be used, based on direction from an Indigenous community.

Severity of adverse impacts

In the context of the IAA, the objective of assessing a project’s impacts is to inform the Government of Canada’s decision regarding the project. The findings of the assessment should enable the decision-maker and the public to understand the ways in which people and the environment are likely to be affected by the project.

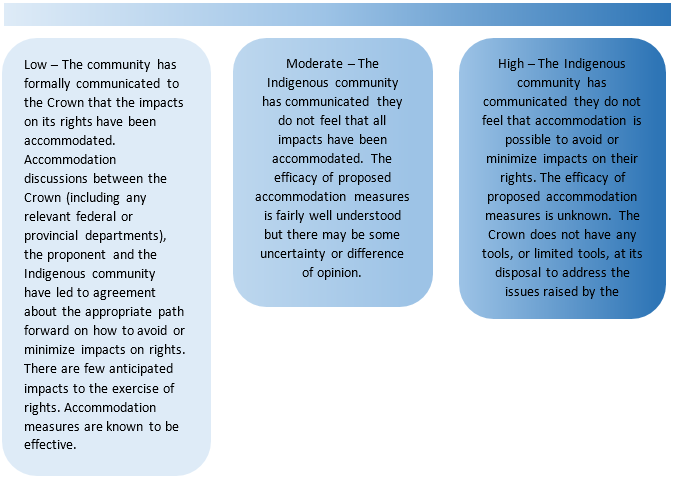

The Agency uses a model of severity as a continuum to indicate the degree to which the exercise of rights may be affected by a project. The levels of low, moderate and high are simply generic markers along the spectrum that are used to provide a relative approximation of the level of severity.

The degree of severity can be described by the defining characteristics laid out in Table 1 (see each criteria for a more robust set of considerations and definitions that would fit within each category). Note that not all characteristics need to be met within one category — for example, in order for an outcome to be “high” only one or some of the criteria need to be met.

Projects generally result in more than one impact. In order to develop measures to avoid or mitigate adverse impacts, and to inform potential accommodation measures, the severity of all impacts identified in the assessment should be evaluated. To rate the overall severity of impacts on rights, the highest degree of severity is used. If one adverse impact is determined to be high in severity, then the overall impact of the project on rights is determined to be high in severity. Impacts may also be linked to a number of criteria. This assessment is meant to be conducted in a holistic manner. Discussions on whether an adverse impact is acceptable to an Indigenous community, given any positive impacts, should occur throughout the assessment process.

This table provides some considerations that could inform the assessment of the severity of impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. The considerations can be adapted based on the project, geographic locations, and guidance from each Indigenous community.

| Low severity | Impacts are likely to be minor in scale, short duration, infrequent, small in spatial extent, reversible or readily avoided or reduced; cultural well-being is minimally disrupted; no or few effects to health and/or country foods; few (or no) existing or proposed developments or historic impacts in group’s territory; project and activities in alignment with group’s development, land or water use plans; sub-groups of the population are resilient enough to sustain impacts and maintain exercise of rights; mitigation should allow for the practice of the right to continue in the same of similar manner as before any impact. |

|---|---|

| Moderate severity | Impacts are likely to be medium in scale, moderate duration, occasionally frequent, possibly/partially reversible, spatial extent affects preferred use areas or disrupts interconnectedness and/or knowledge transfer; cultural well-being is impeded or altered; impacts to individual and/or community holistic health, including perceptions of impacts; project interacts with a few preferred areas where rights can be practiced, and some historic, existing or proposed development and/or disturbance; project may not be compatible with aspects of land use plans or application of traditional laws and governance; vulnerable sub-groups are likely to experience higher impact on ability to exercise rights; mitigation may not fully ameliorate impact but should enable the Indigenous group to continue exercising its rights as before, or in a modified way. |

| High severity | Impacts are likely to be major in scale, permanent/long-term, frequent, possibly irreversible and over a large spatial extent or within an area of exclusive/preferred use; cultural well-being is disrupted, impeded or removed; project interacts with only area where a right may be exercised and many historic, existing or proposed developments and/or disturbance; decision-making associated with governance and title adversely affected; sub-groups will be disproportionately impacted by the project and experience no to little benefit; mitigation is unable to fully address impacts such that the practice of the right is substantively diminished or lost. |

Criteria

The Agency has proposed a suite of criteria that can be used to evaluate the severity of a wide range of adverse impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples. This suite of criteria can be used as an inventory from which to develop the set of criteria to consider for the assessment of impacts on the rights of a particular Indigenous community, based on discussion with that Indigenous community and the methods and valued components that are identified. Criteria and definitions in this guidance are intended to be flexible, responsive, and adaptable. Impact assessment practitioners are encouraged to amend or customize criteria through consultation with Indigenous communities in order to reflect the nature of the impacts linked to a particular project, how the Indigenous community wishes to present their information, the unique context of the landscape, Indigenous knowledge that the community provides, and the rights being impacted.

Below are proposed criteria to use as a starting point in working collaboratively on assessing the severity of impacts on rights:

- Likelihood;

- Geographic extent;

- Frequency, duration and reversibility;

- Cultural well-being;

- Health;

- Cumulative impacts;

- Governance; and

- Impact inequity.

The explanation for each criteria that follows includes a definition, considerations, questions to guide the impact assessment practitioner’s work, and a description of the levels of low, moderate, and high severity of impact. The guiding questions can be helpful to pose to Indigenous communities during consultation to elicit the information needed in order to come to a sound conclusion with respect to the severity of impacts.

As noted above, the impact assessment practitioner can tailor the criteria in collaboration with the affected community. In addition, where community-defined thresholds and criteria exist, those should be included in the assessment-specific set of criteria.

Information on the criteria being used, such as those contained in this document, should be shared with Indigenous communities early in the consultation process to be transparent about how impacts on rights will be assessed and evaluated to determine severity.

Likelihood

The likelihood of an impact on rights occurring can be based on knowledge and experience with similar past impacts. The full lifecycle of a project, including its various stages and lifespan, should be considered in determining the likelihood of an effect occurring.

Considerations

The federal impact assessment is a planning tool to identify the impacts of projects (both positive and negative) before decisions are made. As a predictive exercise, a degree of uncertainty will typically accompany any assessment conclusions. Examining whether impacts could happen because of regular construction, operation, and maintenance, versus a more speculative impact from accidents or malfunctions can help inform a dialogue on how likely it is that an impact would occur. While accidents and malfunctions are inherently unlikely to occur, they still need to be understood and considered. The views of the Indigenous community should be considered regarding acceptable risk levels for more speculative events where there is a greater degree of uncertainty in any impacts that could result.

The perception of the likelihood of impacts occurring should also be considered, as this can result in a behavioural change that affects the exercise of rights, even if there is only a remote probability of the impact. If an Indigenous community is of the view that there is a high likelihood or unacceptable risk that their practices would change because of a perceived impact, that alteration in the exercise of rights should be carried through the rest of the analysis for the purposes of identifying possible solutions to the issue.

In many instances, enabling members of an Indigenous community to learn more about effective risk mitigation strategies or regulatory frameworks in place to address the likelihood of impacts occurring, including through workshops or facility tours highlighting the effectiveness of ongoing monitoring, can help a community feel more confident about the management of risks. The goal of these strategies should be to make people feel safe. It is often insufficient to have technical experts inform concerned citizens that they should feel safe. It is more important to ensure that communities have sufficient information to allow them to come to an informed understanding of the project’s impacts.

Guiding questions

- Is there a direct and causal connection between the project and an impact on a right, or is there a possibility of an impact (e.g., is the construction going to cut down trees with cultural value, or is the threat of an accident the concern)?

- Is there a similar project elsewhere with data to explore in relation to the types of impacts on Indigenous rights that would be likely to occur?

- Can adaptive management tools reduce consequences of impacts that are uncertain to happen?

- How confident is the Crown in any risk assessments (for both likelihood and consequence) available at this stage of the impact assessment?

Figure 2: Severity of impact levels — Likelihood

Geographic extent

Geographic extent refers to the spatial area over which the impact is predicted to occur. Typical qualitative scales for characterizing geographic extent include site-specific, local, regional, provincial, national or global. It is helpful to describe the extent of an impact in terms of how much of the traditional territory would be impacted. Key information required for this criterion includes the location of each Indigenous community’s traditional or treaty territory and interactions with the project’s effects.

Considerations

Review the areas where rights can be, or are currently, practiced within an Indigenous community’s territory and where the preferred areas of practice are located in relation to the project and the project’s effects. Consider whether or not the project and its components will open up access to non-Indigenous populations, and how that will interact with the practice of rights within an Indigenous community’s territory. Understand existing levels of disturbance across an Indigenous community’s traditional territory and the importance of particular areas of harvesting, cultural, spiritual and/or interconnected value.

Guiding questions

- Which airsheds and watersheds could experience adverse environmental effects and in whose territory would they occur?

- Are there migratory species that could be significantly affected by the project?

- If so, within whose territory might they travel?

- Are there concerns with the upstream or downstream impacts of the project?

- Are there areas of high value or significance that may be impacted by the project?

Figure 3: Severity of impact levels - Geographic extent

Frequency, duration and reversibility

Frequency describes how often an impact could occur within a given time period (e.g., alteration of aquatic habitat will occur twice per year). Duration refers to the length of time that an impact on a right is discernible (e.g., day, month, year, decade, or permanent). A reversible impact is one where the exercise of rights is expected to recover from the impact caused by the project. This would correspond to a return to baseline conditions, or other target, through mitigation or natural recovery within a reasonable time scale as defined by the Indigenous community.

Considerations

Frequency can be described using quantitative terms where possible, such as daily, weekly or number of times per year. It may also be described qualitatively, such as rare, sporadic, intermittent, continuous, or regular. Frequency should be looked at in terms of how often disruptions to the practice of rights may occur. It is necessary to consider how often an Indigenous community can practice a particular right in the ‘base case’ (i.e. without the project). For example, if the right to hunt caribou can only be practiced during a specific period due to migration patterns and a project would impede the ability to carry out the right, the impact on the right may be more serious despite the fact that it occurs infrequently.

Duration can refer to the amount of time required for the exercise of rights to return to the baseline conditions against which the changes from the project were measured, through mitigation or natural recovery. The duration of the impact may be longer than the duration of the activity that caused the impact. Impacts may not occur immediately following the activity causing them, but these impacts still need to be considered. For example, when a new reservoir is created there will be a delay before increases in methyl mercury concentrations occur in fish. Similarly, the effect on the intergenerational transfer of knowledge in relation to the exercise of rights may not be observed for many years after a project disrupts the exercise of the right. Possible metrics for duration include short-term in weeks-months, medium-term in months-years, and long-term in years-decades. Impacts may occur over a short period of time (e.g., minutes); however, the length of time it may take to resume the practice of a right and cultural implications of a disturbance from a project should be taken into account when assessing the duration of the impact (e.g. does a ceremony need to be performed before a disturbed hunt can recommence?)

Reversibility can be influenced by the resilienceFootnote 6 of the Indigenous community’s practice of a particular right to imposed stresses and the degree of existing stress on their ability to exercise the right. It also depends on the ability of the Indigenous community to pass on information, practices, language, protocol, stories, etc., that are necessary to practice the right in the preferred manner after a disruption occurs.

Guiding questions

- How and at what times could the project and associated effects interact with the exercise of rights?

- What does the Indigenous community consider a reversible impact?

- What time scale is the Indigenous community using to articulate impacts on their rights?

- Are there rights that are practiced less frequently and could then be more vulnerable to interruptions?

Figure 4: Severity of impact levels — Frequency, duration and reversibility

Cultural well-being

Cultural well-being can be considered as the ability of a group to continue customs, traditions, and practices integral to the group’s distinct culture. The cultural dimension of a right of Indigenous peoples cannot be treated as an add-on; rather, it is foundational to assessing potential impacts to that right. Many rights are based on a unique relationship to the landscape that cannot be replicated elsewhere.

Considerations

When examining cultural well-being and worldview, the following factors may be helpful in understanding impacts on rights:

- safe access to travel routes and safety in areas necessary for practicing rights;

- continuity of traditions;

- cohesion of family groups;

- privacy or peace needed for practicing rights;

- quality of the experience of practicing the right, both spiritually and physically ;

- social organization, customs, traditions, and ceremonies;

- stories and storytelling opportunities;

- use and transmission of language and knowledge;

- seasonality of use for various resources and practices within a territory;

- how resources are tied to ceremonies or regalia;

- reactions of spiritual or cultural entities to changes to the environment;

- Indigenous laws; and

- any other relevant factors the community raises.

The assessment should consider impacts on the following types of areas that could hold cultural importance within an Indigenous community’s territory. Note that the values associated with the different areas may overlap with one another:

- a) Physical heritage areas with certain tangible resources, such as notable densities of archaeological sites or burial grounds.

- b) Harvesting areas where traditional lifestyles are practiced through activities such as hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering.

- c) Sacred sites of particular spiritual importance.

- d) Cultural landscapes with interconnected heritage sites, including the travel routes and spaces between them.

Guiding questions

- What else is happening within the territory from a social, industrial or cultural perspective that could impact the resiliency of cultural practices?

- Is there cultural and psychological stress for members of the Indigenous community due to the fear of losing their ability to exercise rights in their preferred manner because of the project?

- Has the impact assessment practitioner been informed by the Indigenous community about cultural impacts, even if the group is unable to share details because it is not culturally appropriate?

- Will the project impact the ecosystem or cultural values that support an Indigenous community’s way of life and cultural health, including its practices, customs, and traditions?

- Is the project consistent with, and does it support, the preferred expression of an Indigenous community’s rights?

Figure 5: Severity of impact levels - Cultural well-being

Health

Health is included as a suggested criterion, but it also may be identified by an Indigenous community as a value unto itself to be assessed to determine potential impacts on rights. In addition, changes to the health conditions of Indigenous peoples (whether or not specific to the exercise of rights) must also be considered as a factor in an impact assessment under section 22 of the IAA. Thus, there may be considerable overlap between this criterion and other parts of the impact assessment. However, the purpose of including health as dimension for analysis of severity for all impacts on rights is to capture the inter-relatedness of impacts on rights and impacts on the health conditions of the Indigenous community.

For the purposes of this guidance, “health” includes considerations of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health, including Indigenous views of health. Health can be a fluid concept that can be understood in different ways; therefore, it is important to understand the perspectives and working definitions belonging to the potentially affected Indigenous communities and take steps to integrate those perspectives and definitions into the assessment of impacts. For example, the World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,”Footnote 7 while the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia describes health as starting from an individual human perspective and expanding outwards to include the land, family, and the broader community.Footnote 8

Considerations

When examining health during the assessment of impacts on rights, the following factors may be helpful to consider:

- how the project could change the quality, abundance and access to country foods and traditional diet;

- whether community members are concerned about project-based contamination and if that will change their behaviour in practicing rights and consuming food harvested from the project location or areas impacted by the project;

- stress related to participating in the impact assessment process, or ongoing participation in the development of the project, as well as in other federal, provincial, or municipal processes;

- consultation fatigue;

- the current state of community physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health;

- traditional models of wellness;

- health and mobility of Elders and cultural knowledge holders, or other sub-populations of the community;

- connections between health and socio-economic conditions;

- interconnection between impacts to the landscape and the mental, emotional and spiritual health of the Indigenous community and its members;

- community infrastructure, access to health and social services, and health behaviours or awareness; and

- racism and social exclusion.

Guiding questions

- What is the Indigenous community’s definition or model of health? What are their determinants of health (social, cultural, economic and environmental)? How does individual health link to the broader community or landscape?

- Are Indigenous communities concerned about impacts to traditional diets or food security? What are the impacts related to (i.e., barriers to harvesting, quantifiable or perceived effects to quality of harvested country foods, resources and/or ecosystems, reduced harvesting success)?

- What are Indigenous communities observing in relation to overall health and wellness, and how is it changing due to ongoing projects and impacts from the project in question?

- Would the project affect traditional economic or cultural practices, such as a potlatch, Footnote9which support overall health in the community?

- Is there any physical or psychological stress for members of the Indigenous community due to the fear of losing their ability to exercise rights in their preferred manner because of the project?

Figure 6: Severity of impact levels - Health

Cumulative impacts

Cumulative impacts on a right may result from a project in combination with impacts of past, existing and future projects or activities. Cumulative impacts may have a regional or historic context and may extend to aspects of rights related to socio-economics, health, culture, heritage, and other matters tied to an Indigenous community’s history and connection to the landscape. While the outcomes of the cumulative effects assessment, as required under section 22 of the IAA, may and should be included under this criterion, cumulative impacts consider a broader range of impacts and are not limited to a consideration of impacts from projects and activities as defined by the legislation. This criterion is meant to enable an understanding of the existing state of affairs and the complex history of interconnected effects on a holistic level.

Considerations

When considering cumulative impacts on rights, it is necessary to review the various projects or activities that may have already impacted the practice of a right in a particular area. Examining the historical context requires recognition of past events that have contributed to the existing state of affairs. It may be necessary to consider the situation where a right is not presently being practiced due to external factors such as industrial disturbance.

For regional context, it may be important to consider the ability of an Indigenous community to practice rights within their territory at other preferred areas. This assessment should span from the beginning of the project until reclamation. Future projects that are reasonably foreseeable should be considered within this assessment and how they could combine with impacts from the project in a manner that could affect the exercise of rights.

Guiding questions

- What is the Indigenous community’s perspective on how their rights have been impacted by cumulative effects?

- Has the practice of a right been impacted by past government policies such as relocation, residential schooling, laws banning cultural practices, not being allowed to harvest resources off-reserve, effects of a built environment, or resource extraction?

- If so, is the community working to restore the practice of this right, and would the project interfere with the restoration of the practice?

- Are there cumulative impacts to the exercise of rights that may not have been captured when assessing the residual environmental effects after mitigation is applied?

- Are there applicable community thresholds, laws, or norms that have already been crossed or that will be breached by the project?

Figure 7: Severity of impact levels — Cumulative impacts

Governance

The Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (the UN Declaration) affirm the right of Indigenous peoples to self-determination, including the inherent right of self-government. Consideration of potential impacts on the rights of indigenous peoples in the impact assessment process should include consideration of how the project could affect the exercise of rights that are related to governance, including Indigenous laws and governance systems.

Indigenous communities have governance responsibilities to their membership (including to future generations) for strategic planning, management, and stewardship of their traditional lands and resources. Indigenous governance and decision-making authority may be expressed through a community’s specific laws, norms, power, language, and how members of the group are held accountable for their actions. Governance is related to self-determination, jurisdiction, stewardship, and nationhood. Indigenous communities have the right to choose how they are governed, and by whom, in accordance with their laws, customs, structures, and other relevant matters as identified by that community according to their own processes and traditions.

Governance can include consideration of both the acceptability of an impact (to what extent can the group tolerate the impact?) and manageability or resiliency (what level or types of impacts can the Indigenous community absorb?).

Project activities may affect resources, access, and activities in an area traditionally governed by Indigenous laws and practices. The presence of a project may also affect power balances or dynamics within and between communities, as well as the ability of a community to implement their inherent right to self-government.

Considerations

When considering governance, it is necessary to review how a project could affect an Indigenous community’s decision-making processes, including their decisions relating to risks of future impacts.

Project-related decisions by a proponent or governments during pre-impact assessment or impact assessment phases that do not acknowledge or seek to incorporate Indigenous customs, laws, and practices may affect stewardship and nationhood. They may also contravene Indigenous laws and jurisdiction. Indigenous communities may have land and water use plans, and specific protocols outlining how consultation, environmental studies, use of traditional knowledge or resource development should occur. Project planning, data collection and subsequent decision-making that do not consider relevant land use plans and protocols developed by Indigenous communities may be viewed as disrespectful of Indigenous governance, and may result in changes that compromise the goals and objectives of Indigenous communities related to resource management, health and safety, economic development and spiritual practices. If this occurs repeatedly, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities may lose appreciation for Indigenous laws and practices resulting in impacts to stewardship and nationhood.

This criterion can also take into consideration the rights protected pursuant to Aboriginal title. Title rights include the right to decide how the land will be used, the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land, the right to possess the land, the right to the economic benefits of the land and the right to proactively use and manage the land. A project may restrict an Indigenous community’s ability to exercise their title rights by affecting resources, access and ability to enjoy the land. If an Indigenous community views the source of its title as tied to an interconnected landscape through spiritual/cultural connections according to their traditional stories and ontology, the very presence of a project may pose serious impacts to the integrity of or connection to title.

This criterion can highlight impacts on rights including title as they relate to the economic benefits of the land and interests of the exercise of rights (e.g. a location is valuable as it gives access to fish that can be harvested and sold). As stated in Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, “The title holders have the right to the benefits associated with the land — to use it, enjoy it and profit from its economic development.”Footnote 10

Guiding questions

- Who is/are the appropriate rights-holder(s) with whom to consult (e.g., hereditary chiefs with governance responsibilities over different parts of an Indigenous territory)?

- To what extent does the project, impact or process weaken the Indigenous community’s authority over its territory?

- What is the capacity for federal/provincial/municipal government, Indigenous communities, and the proponent to manage the impacts once the project begins? Was the Indigenous community involved in, or have confidence in, the risk modelling for the likelihood of impact and effectiveness of mitigation and accommodation?

- Are there safety concerns that would prevent members of the Indigenous community from accessing and harvesting resources?

- How could the project change the Indigenous community’s ability to derive future economic benefits from or maintain an ongoing relationship with the land or water?

- What is the portion or percentage of the territory that the project could alienate from the Indigenous community’s occupancy and use?

- Are the decisions of a proponent or government, or an impact from a project, in contravention of Indigenous laws and jurisdiction (from the Indigenous community’s perspective)?

- How does the project change or restrict future land and water uses by the Indigenous community?

- What is the current land ownership arrangement (e.g., Crown land, private land, part of treaty process)?

- Does the Indigenous community claim title to any area that could be impacted by the project?

- How does the Indigenous community believe its claim to title could be impacted by the project?

- Is the Indigenous community currently negotiating agreements under the Comprehensive Land Claims or Inherent Right policies, or through Recognition of Indigenous Rights and Self-Determination discussion tables? How could these negotiations inform the assessment of impacts on rights?

- Could the project impact the Indigenous community’s relationship to the land or water, in a way that is incompatible with aspects of its title claim?

- Will the project have an impact on the Indigenous community’s planning, management or stewardship of traditional lands and resources?

- Will the project or process impact the exercise of the Indigenous community’s governance rights?

- Has the Indigenous community provided their free, prior and informed consent for the project?

Figure 8: Severity of impact levels - Governance

Impact inequity

Project impacts could be disproportionately experienced by parts of a population, such as women, Elders, youth, or a particular family group, and benefits may only go to a few individuals or segments of a community. Project impacts could be disproportionately experienced between different Indigenous communities or between past, present or future generations.

Considerations

Project activities resulting in changes to quality and quantity of resources or access to resources may cause impacts to specific resource users and could be more acute for vulnerable populations within an Indigenous community. Project activities may also result in disproportionate impacts to the intergenerational transfer of knowledge between different parts of the community, and across communities. The benefits a community receives from Impact Benefit Agreements, which are meant to offset impacts, may not benefit the entire community equally. The impacts may also be borne by future generations more than the current generation.

Disproportionate impacts or benefits between different Indigenous communities may result in or potentially reinforce regional inequities.Footnote 11

Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+)Footnote 12 would fit within this criterion and may facilitate the identification of impacts that may be largely experienced by Indigenous women.

Guiding questions

- Does the direction of the impact (i.e. positive or negative) shift between different groups and sub-populations? Do some benefit while others do not?

- Are the impacts disproportionately experienced by parts of the population, such as women, Elders, youth, or a particular family group, or do the benefits only go to a few individuals or segment of the Indigenous community?

- How resilient are the potentially affected communities? How vulnerable are they to adverse impacts?

- Are certain family groups more impacted than others (e.g., one part of a traditional territory will bear more impacts and reduce the ability for one family or group to exercise their rights)?

- Are the impacted groups more vulnerable to change?

- Does the project provide an acceptable level of mitigation and benefits from the Indigenous community’s perspective to justify the impacts on the exercise of rights?

- Do the project-specific mitigation measures and benefits further reconciliation and preserve the ability of future generations to benefit from their rights?

Additional questions that the Agency’s guidance poses for the purposes of GBA+ should be discussed with each Indigenous community. These questions include:

- Who might be affected by the project? How do we know? Will these positive or negative impacts be different for sub-groups in the Indigenous community?

- Is there evidence that suggests that the project may impact diverse groups differently based on cultural and ceremonial roles in the community, or based on specific identity factors?

- Does the assessment address this evidence and, where relevant, provide a rationale as to why potential differences are investigated or are not investigated?

- How does the social and historical context of the Indigenous community affect how people may be differentially impacted by the project?

- Are there inequitable structures or systems within Indigenous communities that may affect who participates in the impact assessment process, the views that are heard, or what information is considered? Have steps been taken to create inclusive and safe engagement and consultation opportunities to hear diverse voices (e.g., the provision of childcare at a community event to ensure that childcare providers, typically women, can participate in the meeting)?

- Are baseline profiles of Indigenous communities available, disaggregated by age, ethnicity, sex or other community-relevant factors to support analysis?

Figure 9: Severity of impact levels — impact inequity

Part 3: Addressing impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples

Once the impact assessment practitioner and the Indigenous community have identified important values and the baseline conditions for exercising rights, have identified the potential pathways of impact from the project to those values and rights, and have established and applied criteria for assessing the severity of impacts, then the dialogue can turn to the measures needed to address the identified impacts. Ideally, throughout the assessment, participants should be thinking about options to address the concerns as they are raised. Towards the end of the impact assessment process, when all relevant technical information and Indigenous knowledge has been assessed, consultation on the outcomes of the assessment of impacts on rights should enable all parties to work together to find mutually agreeable solutions to outstanding issues and impacts wherever possible.

Considerations

When determining whether the Crown can rely on the proponent’s mitigation and accommodation to fulfill the Crown’s duty to consult, in whole or in part, the Crown must consider the combined ability of all measures to avoid, minimize, or compensate for adverse impacts. Some proposed mitigation measures may be easy to understand, evaluate and connect to the identified pathways to an impact, while other measures may require technical knowledge and experience, or a review of the effectiveness of similar measures when applied elsewhere or in the past. Indigenous communities should be engaged in a dialogue on their views of the suitability or perceived effectiveness of specific initiatives to mitigate or accommodate impacts.

Economic or other capacity-building opportunities may be proposed to offset impacts on rights. When details on economic or other benefits are included in Impact Benefit Agreements between the proponent and Indigenous communities, they may be difficult for the Crown to evaluate since the contents of these agreements are often confidential.

Accommodation measures such as land offsets, wildlife protections, resource revenue-sharing agreements, and land use planning are often within a provincial government’s jurisdiction. Federal departments may also have programs and policies that can be relied upon to accommodate certain impacts. Information provided by provincial governments, federal departments, and Indigenous communities may assist in understanding the effectiveness of these measures that could complement mitigation or other forms of accommodation.

Within the context of project-based impact assessments, one of the principal tools used for accommodating impacts is the set of conditions attached to the impact assessment Decision Statement and imposed as legally binding on the proponent. Aligned with Step 7 in the impacts on rights methodology, monitoring and follow-up programs may also be needed to assess the accuracy of the assessment conclusions and the effectiveness of mitigation measures.

Although monitoring and follow-up programs typically focus on biophysical components, involvement of Indigenous communities in monitoring and follow-up, including the provision of ongoing advice to regulatory agencies, may serve to accommodate for certain impacts beyond the biophysical. If this is the intent, this should be discussed with the Indigenous community in advance.

Guiding questions

- Has the Indigenous community proposed any mitigation or accommodation measures?

- Has the Indigenous community been consulted on the proposed accommodation, and if so, do they agree that it addresses their concerns?

- If employment opportunities are meant to offset impacts, will training be provided to ensure that many can benefit from the opportunities?

- If accommodation is in the form of environmental or natural resource compensation, is it in the appropriate Indigenous community’s territory and in an area where members can exercise their rights?

- Are the Crown and the Indigenous community confident in the effectiveness of the proposed accommodation measures to avoid or minimize impacts on rights?

- Do the roles and opportunities for monitoring and follow-up align with Indigenous laws and self-governance rights? How may these be adjusted to fit the preferred approach of those involved?

Figure 10: Severity of impact levels

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission stated, “reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country”Footnote 13. This guidance aims to create the space for a mutually respectful relationship between all parties during an impact assessment process when discussing the impact of projects on the rights of Indigenous peoples and working together to find mutually beneficial solutions.