Toward a Canadian Naval Service (1867-1914)

The establishment of the Canadian Navy is remarkable, both for the lateness of that event and the meagre results. Canada, whose motto translates as “from sea unto sea,” has the longest coastline of any country. Even so, the navy was not founded until 4 May 1910, nearly 43 years after the creation of the modern Canadian state on 1 July 1867. Despite growing tensions in international relations, the new service was so politically controversial that it was nearly stillborn, and Canada remained desperately unprepared when Europe descended into war in the summer of 1914.

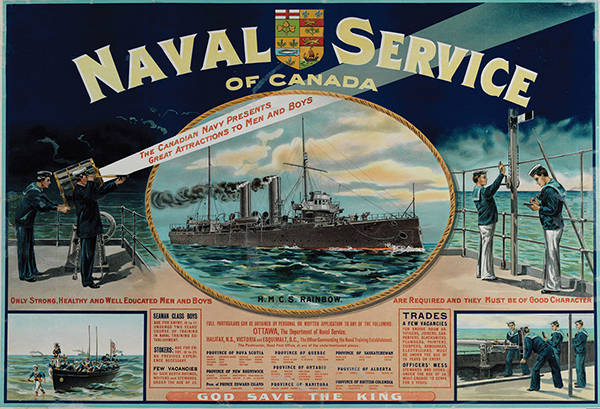

The RCN’s first recruiting poster.

-

Long description of poster

The RCN’s first recruiting poster

Naval Service of Canada. The Canadian Navy Presents Great Attractions to Men and Boys. Only Strong, Healthy and Well Educated Men and Boys are Required and They Must Be of Good Character. Seaman Class Boys – Age for entry, 15 – 17. Undergo two years of course of training at naval training establishment. Stokers – Age for Entry, 18 – 25. No previous experience necessary. Trades – A Few Vacancies for Engine Room Artificers, Joiners, Carpenters, Blacksmiths, Plumbers, Painters, Coopers, Armourers, Electricians. Must be under the age of 28 years on entry. Officers’ Mess – Stewards and cooks, under the age of 28, must engage to serve for 5 years. Full Particulars can be Obtained by Personal or Written Application to Any of the Following: Ottawa, the Department of Naval Service. Halifax, N.S., Victoria and Esquimalt, B.C., The Officer Commanding the Naval Training Establishment. The Post Master, Head Post Office at any of the undermentioned places. God Save the King.

The paradox arose from Canada’s development as a part of the British Empire. The empire owed its creation and expansion to Britain’s Royal Navy, the world’s most powerful from the late seventeenth century until the beginning of the 1940s. Britain was able to seize France’s colonies in North America during the Seven Years’ War because the Royal Navy’s predominance in the Atlantic allowed the British to mass their forces for the assaults on the main French strongholds of Louisbourg in 1758 and Quebec in 1759, while cutting off New France from reinforcements. Britain’s own American colonies were able to secure their independence in 1783 because a European alliance led by France temporarily achieved the advantage over the Royal Navy. Yet, the Royal Navy turned back an American invasion of Canada in 1775-76, and again prevented the conquest of the remaining British North American colonies when the United States repeatedly invaded in 1812-14. It was the menace the Royal Navy posed to the U.S. seaboard from bases at Halifax, Bermuda, and Jamaica that ultimately secured Canada from American Manifest Destiny during crises in the 1830s, 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s.

Military dependency upon Britain and cheap defence were foundation stones of Canada. The primary cause of the revolt of the American colonies in 1775 had been British efforts to tax the colonists to pay the enormous costs of the British forces that had conquered Canada in 1754-63 to secure the American territories against French incursions. Thereafter, Britain did not generally attempt to recoup the costs of its forces on colonial service, particularly in the case of Canada whose French-speaking inhabitants viewed the British military as occupiers, not protectors.

The first recruits of the Naval Service of Canada.

At issue were land, not naval, forces. Since the American invasion of 1775, the southern border of the northern colonies had to be protected by fortifications, garrisoned by troops from Britain’s small, expensive professional army, to prevent the territories being overrun while the Royal Navy conducted offensive operations against American trade and coastal cities. In the 1840s and 1850s, the British government responded to political unrest in the northern colonies by granting self-government in internal matters, but also began to cut back the garrisons sharply, linking self-government to greater responsibility for self-defence—and incidentally, relief to the British treasury. When the American Civil War of 1861–65 threatened to engulf the colonies, the British Army massively reinforced the garrisons, but the steep cost of this effort was an important reason why the British government supported confederation of the colonies to create the Dominion of Canada in 1867. Britain withdrew all of its troops from the interior of the new country in 1871, and defence of the border became the responsibility of the Canadian militia, a force of some 40,000 part-time volunteers administered and instructed by a “permanent force” of full-time professionals that numbered no more than 1,000 until the early 1900s.

The ultimate guarantee of Canadian security was still the Royal Navy. Even the most cost-conscious British politicians admitted that protection to Canada was the incidental product of Britain’s need to control the North Atlantic, the heart of the seaborne trade that was Britain’s lifeblood. Britain retained its strongly fortified dockyards at Halifax and Bermuda, together with the permanent naval squadrons that operated in the western Atlantic and the eastern Pacific, including the new British dockyard at Esquimalt, British Columbia. British Army garrisons of about 2,000 troops remained at Halifax and Bermuda, and British troops later developed defences at Esquimalt. Canadian leaders of the late nineteenth century, believing that the British naval presence persuaded the United States not to attempt domination of Canada, avoided naval defence undertakings for fear these would encourage British cutbacks.

The possibility of a distinctly Canadian path to naval development emerged in the late 1880s when an Atlantic fisheries dispute with the United States brought the government to organize a fisheries protection service of six to eight small armed vessels to arrest American fishing craft that illegally entered Canadian territorial waters—waters within three nautical miles (approximately six kilometres) of shore. The vessels and their crews formed part of the Canadian Department of Marine and Fisheries, whose principal responsibilities included lighthouses and other aids to navigation and the regulation of civilian shipping. Ex–Royal Navy officers who the Canadian government hired to run the service and British officials in Canada saw the possibilities for developing the fisheries protection service into a naval force. The Admiralty was not interested. Rapid progress in technology saw the development by the late 1880s of large, fast, long-ranged steel-built warships, renewing confidence that the Royal Navy’s main fleets, centrally controlled from London in their global deployments, could, just as in the days of sail, intercept any but the smallest enemy forces. In 1887 the Australian colonies and New Zealand began to make annual payments to the Admiralty to subsidize the assignment of additional Royal Navy cruisers to their waters.

By the late 1890s the idea that the empire should become a more tightly organized military alliance to meet sharply increasing competition among the great powers won widespread support in Britain and all the self-governing colonies. When in 1899 Britain went to war with the Boer republics in South Africa, the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier, Canada’s first French-Canadian prime minister, was caught between demands for participation from English Canadians and strong resistance from French Canadians. Laurier’s compromise, to send contingents comprised solely of young men and women who volunteered to serve, by no means healed the rift in opinion. The brilliant Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) and journalist Henri Bourassa broke with the prime minister to campaign against military cooperation with Britain; he especially warned against naval initiatives because of the Admiralty’s doctrine of centralized control of the empire’s naval defences. Even Bourassa admitted, however, that there was a need for fisheries protection.

Laurier tried to square the political circle by casting military reforms as national defence measures that enhanced Canadian status, but also strengthened the empire by relieving Britain’s over-stretched armed forces of commitments in North America. He was prepared to undertake naval development of the fisheries protection service, and in 1903–04 the government procured the CGS Canada, a 910-tonne steamer built to naval specifications. Further naval initiatives, however, were put on hold in December 1904, when Britain, as part of its efforts to concentrate its armed forces closer to home to meet growing dangers in Europe, closed the dockyards at Halifax and Esquimalt, and announced that the Royal Navy squadrons that had operated on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America would be withdrawn. The defences at Halifax and Esquimalt would still be needed to provide secure operating bases for the British fleet, so Laurier seized the opportunity for a nationalist initiative warmly endorsed by both French and English Canadians, by offering to take full responsibility for the permanent garrisons and fortifications at both Halifax and Esquimalt. This gesture, which the British gratefully accepted, entailed tripling the size of the 1,000-man permanent land force, and was the main reason why the land militia’s annual budget doubled to some $6 million a year.

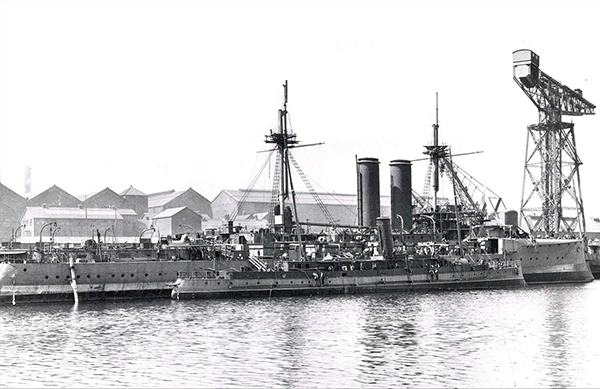

The future CGS Canada fitting out in the Vickers yard at Barrow-in-Furness, 1904, lying outboard of HMS Dominion, also still under construction and whose first captain in 1906 would be Captain C.E. Kingsmill, Royal Navy (RN).

Laurier still maintained that the fisheries protection service was the “nucleus” of a navy, but any grander schemes were effectively scuttled. Further development came as the result of scandal. Early in 1908 a royal commission reported that the Department of Marine and Fisheries was hopelessly inefficient. Laurier and the minister, Louis-Philippe Brodeur, a lawyer whose early career in Quebec nationalist politics gave him credibility in that province, cleaned house immediately. Georges Desbarats, an engineer in the department with a reputation as a talented administrator, became deputy minister. Laurier had already met, and been impressed by, Charles E. Kingsmill, a Canadian who had entered the Royal Navy in 1869 at the age of 14 and risen to the rank of captain. Kingsmill accepted the invitation to take charge of the government’s marine services. Promoted rear-admiral on his retirement from the Royal Navy, his professional credentials were on an entirely different plane than those of his predecessors, who typically had left the British service as very junior lieutenants.

The Conservatives, led by Robert Borden since 1900, were no more anxious than the Liberals to confront the contentious naval issue. They contented themselves with periodically tweaking the government to get on with naval development of the fisheries protection service. In January 1909 Sir George Foster, one of Borden’s senior colleagues and a former minister of marine and fisheries in the Macdonald era, placed on the order paper for the new session of Parliament a resolution that “Canada should no longer delay in assuming her proper share of the responsibility and financial burden incident to the suitable protection of her exposed coast line and great seaports.” The resolution had been inspired by an Australian initiative to end the annual subsidies to the Royal Navy, and instead revive their own naval organization. The Admiralty, holding firm on the need for British control of seagoing warships, allowed that any colonial service could acquire the improved coastal torpedo craft, including destroyers and submarines, that had been developed since the late 1880s.The torpedo craft would make local ports more secure to support strategic deployments of the British fleet.

Before the Foster resolution came up for debate, the politics of the naval issue were transformed by developments overseas. On 16 March, Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty in Britain’s Liberal government, requested additional funds for battleship construction, citing evidence of acceleration in Germany’s building program. In 1905–06 the Royal Navy had stolen a march on competitors by building the revolutionary His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Dreadnought, the first large (16,270-tonne) modern battleship to carry a uniform battery of 10 of the heaviest guns—12-inch—in place of the mix of a few heavy and other lighter guns in existing 9,100-tonne designs. Now, intelligence suggested, Germany might be able to match Britain in numbers of its own “dreadnoughts” as early as 1912.

The news that Britain’s maritime supremacy was so seriously challenged by a single power exploded like a “bomb shell,” in the words of one contemporary Canadian commentator. New Zealand quickly offered to make a special, one-time payment to the British government sufficient to build one or, if necessary, two dreadnoughts. There were wide-spread demands among English Canadians in both the Liberal and Conservative parties that Canada do the same, creating a nearly identical problem for Laurier and Borden, both of whose French Canadian supporters had grave doubts about any form of naval initiative. In the face of these common problems the parties worked out a compromise in a single day of debate of Foster’s resolution, on 29 March 1909. In a new resolution supported by both parties, Laurier promised the “speedy” organization of a coastal defence force in consultation with the Admiralty on the model of the Australian scheme (that, of course, he had always insisted was built on the example of Canadian local defence by forces under Canadian control). Laurier’s draft ruled out any cash contributions to the British government, but at Borden’s insistence the final version rejected only regular contributions and thus did not specifically rule out a future one-time “emergency” payment.

A few weeks later, in fulfilment of the joint resolution’s commitment to cooperation with British authorities, Laurier announced in Parliament in April that Brodeur and the militia minister, Sir Frederick Borden (the Conservative leader’s cousin) would soon visit the Admiralty to consult on Canadian naval development. Admiral Kingsmill prepared a discussion paper proposing the initial acquisition of three small (3,100-tonne) cruisers, two large ocean-going destroyers, and six small destroyers or large torpedo boats.

The British government, surprised at the interest and commitment to action in the dominions, moved quickly to take advantage by calling a special imperial defence conference, which met in London in August. It now dawned on the Admiralty that encouragement of the dominions’ desire for their own armed forces was the only hope for a substantial, long-term commitment that would ease pressure on British defence spending. There was particular scope for action by the dominions on the Pacific, which had been denuded of battleships in the concentration of the British fleet in European waters since 1904. So instead of organizing only the supporting elements of a naval organization, as in the Australian and Canadian coastal defence schemes, the Admiralty presented a new scheme for full-blown imperial cooperation: the dominions should each raise an ocean going “fleet unit” consisting of a single dreadnought battlecruiser (a vessel with less heavy armour plating than a dreadnought battleship, but faster still, and with a similar all big-gun armament), and three large Bristol class cruisers of 4,370 tonnes, together with six destroyers and three submarines. New Zealand’s cash contribution would be used for a third dreadnought battlecruiser that would be stationed in the Far East. The Canadian fleet unit would be stationed on the Pacific coast, ready in an emergency to combine with the Australian and New Zealand ships.

Laurier was appalled at the idea because of the potential opposition in Quebec to “imperial” schemes. Brodeur and Sir Frederick Borden made it clear that any action would have to be based on the Canadian parliamentary resolution. Beyond Quebec, Canadian political realities were that the main centres of population (and voters) were in the eastern part of the country, so any scheme would have to give as much weight to the Atlantic as the Pacific coast, not least because the largest seafaring population and pool of potential recruits was on the Atlantic. The dreadnought battlecruiser was also unacceptable, Borden explained, because “it must be remembered that Canada was only beginning to establish a navy, and that it was desirable to proceed gradually, by gaining experience with vessels of a smaller type in the first instance.”1

Brodeur asked the Admiralty to put forward two schemes, one that would cost £400,000 (approximately $2 million) and the other £600,000 (approximately $3 million).The significant figure was £600,000, which showed Laurier’s commitment to political consensus. Robert Borden had indicated that a suitable Canadian naval effort should involve the commitment of funds at about half of the level of spending on the land militia, then approximately $6 million a year. The request for the smaller, £400,000, scheme signaled Canada’s determination not to be nudged toward the full-fleet unit.

To its credit, the Admiralty provided reasonable responses for the two schemes. The larger one, for an annual expenditure of about £600,000, reached quick mutual agreement. It included six ocean-going destroyers, a flotilla leader (a small cruiser that could act as the command ship for the destroyer force) and four improved Bristol-class cruisers; the whole destroyer force and two Bristols would be stationed on the Atlantic coast and two Bristols on the Pacific. The Admiralty also deferred to the strong Canadian desire that the warships should be built in Canada. Both the Liberals and Conservatives had prominently cited this benefit to industry in the debate on 29 March 1909. The estimated time required to build the destroyers and cruisers in Canada was six years, and the Admiralty agreed to assist the Canadians in building toward this force by supporting the scheme that Kingsmill had drafted in April. Kingsmill, who accompanied Brodeur and Borden, initially asked for two Apollo-class cruisers of 3,100 tonnes and two destroyers: one cruiser for the Pacific coast, and the rest to receive the larger number of recruits anticipated on the Atlantic coast. In November 1909 the Canadian government bought one Apollo, HMS Rainbow, for the West Coast. The Admiralty offered a second Apollo, but no destroyers were available, so Kingsmill arranged for the purchase, in January 1910, of a much larger Diadem-class cruiser, HMS Niobe, to accommodate East Coast trainees. Niobe displaced 10,000 tonnes and had a complement of 705 personnel, as compared to 273 for the smaller Apollos. Niobe was also a more modern ship, having been completed in 1899; Rainbow had been completed in 1893. The funds for Niobe, £215,000, were found by dropping the flotilla leader from the list of modern ships to be acquired.

On 12 January 1910, Laurier introduced the Naval Service Bill in the House of Commons. It was ultimately carried by the Liberal majority, and received royal assent on 4 May 1910, thereby creating the new Naval Service of Canada, and the Department of the Naval Service to administer it. True to its distinctly Canadian roots, the new organization grew out of the Department of Marine and Fisheries. There was no separate minister, Brodeur continuing to head Marine and Fisheries while also taking responsibility for the new department. Canadian politicians had long responded to criticisms of inaction in naval defence by noting that Marine and Fisheries had carried out important functions that in Britain were a naval responsibility. Following passage of the Naval Service Act these “naval” components of Marine and Fisheries—the Fisheries Protection Service, the Hydrographic Survey, Tidal and Current Survey, and the Wireless Radiotelegraph organization of coastal radio stations for ship to shore communications—were transferred to the new department. Desbarats transferred as deputy minister, and Admiral Kingsmill became “director of the naval service,” the department’s professional head. National control was enshrined by the provision that the Canadian Naval Service, or any part of it, could be transferred for service with the Royal Navy under British command only by the explicit action of the Canadian government, which in turn had immediately to seek the approval of Parliament.

What is striking about Laurier’s naval policy is the extent to which it focused on building a political consensus, how closely he constructed that policy on the same nationalist principles as his most dramatic militia reforms, and how quickly and confidently he acted, a direct result of the political success of his militia reforms.

The Admiralty, in consultation with Kingsmill, arranged to loan Canada some 50 officers and over 500 enlisted personnel for secondments of two to five years to operate the cruisers and instruct Canadian recruits. The symbolic inauguration of the Canadian Navy came on 21 October 1910 when Niobe arrived at Halifax and was escorted up the harbour by CGS Canada, the fisheries protection vessel that the Laurier government had touted as the “nucleus” of the Canadian Navy. Rainbow, after a passage of some 15,000 nautical miles (28,000 kilometres) and nearly 12 weeks from England around South America by way of the Straits of Magellan, arrived at Esquimalt on 7 November 1910.

The first members of the Canadian Navy to join the new ships were six officer cadets from CGS Canada who transferred to Niobe the day after it reached Halifax. Two of the cadets had started training in Canada in 1908, and the other four in 1909, as part of the efforts begun with the arrival of Admiral Kingsmill to improve the Fisheries Protection Service. The two cadets from the original 1908 entry included Percy W. Nelles, the son of an officer in the Royal Canadian Dragoons, the cavalry regiment of Canada’s small regular army. Percy, according to a newspaper interview much later in his career, had been raised at Brantford, Ontario, and been fascinated by the shipping on the Grand River. When, as he turned 16, his father asked him what career he would like to prepare for, Percy surprised him by saying he would like to join the navy. Nelles would become chief of naval staff in 1933, and in that position lead the service through its enormous expansion during the Second World War.

Among the 1909 group of entries was Brodeur’s own son, Victor Gabriel. As the latter recounted, he was at home in bed recovering from appendicitis early in October 1909, when his father:

came into my room … and he said: “Victor, how would you like to join the Navy?” Well, previously I had been around the Gulf of St. Lawrence several times in ships and I was very fond of the sea. I just jumped at the suggestion because I had to go back to [Mont-St-Louis] college and give a lecture, and there is one thing that I hated and that was to lecture or make a speech. So he said, “alright . . . next month I’ll take you out and we’ll take you down to Halifax.” And that was that.2

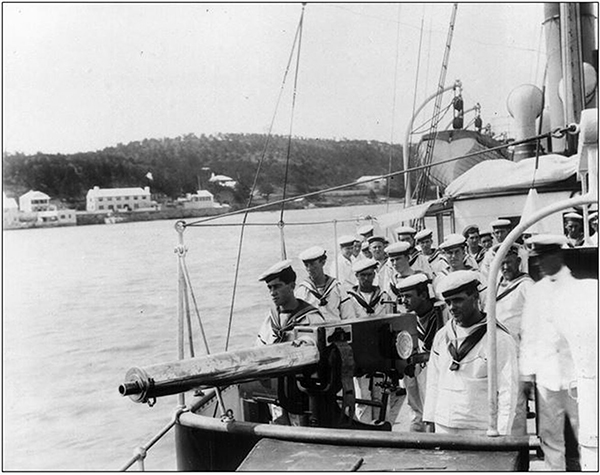

The crew of CGS Canada performing naval militia drills on their winter 1905 cruise to Bermuda.

Victor Gabriel Brodeur, who reached the rank of rear-admiral during the Second World War, during which time he commanded the Canadian Navy on the West Coast and also served for several years as Canada’s naval representative in Washington, was known to at least some in the Canadian service as “the gift.”

This promising start did not last long. What Louis-Philippe Brodeur clearly understood was that the essential element in creating a truly Canadian navy was not ships or dockyards, or guns or state-of-the-art radio equipment, but Canada’s own naval professionals. Despite offers from the Admiralty to admit Canadian officer cadets to the Royal Navy’s colleges, the Naval Service Act included provision for Canada’s own naval college, which had a precedent in the land forces’ Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, established in 1876.The Royal Naval College of Canada opened its doors in the former naval hospital in the Halifax dockyard, with a staff of officers and instructors on loan from the Admiralty, in January 1911 on the entry of the first class of 21 cadets. To man the two cruisers, a national campaign began with posters and notices in newspapers in February 1911. Postmasters were empowered to enter recruits, and local doctors undertook the required medical examinations.

Brodeur’s intention for Niobe to make an extended training cruise to the West Indies in the early months of 1911 was stymied when British legal authorities maintained that the dominions did not have legal powers beyond the three-mile limit of territorial waters. Brodeur complained furiously to a sympathetic Governor General Lord Grey, but to no avail:

I do not see why they would not trust Canada…. Do they fear some illegal acts …? We have for years and years a Fisheries Protection Service which has come constantly into contact with foreign vessels … but we never did anything which brought the Imperial Authorities into serious difficulties.3

Negotiations at an imperial conference held in May-June 1911 resulted in a workable compromise. The British government designated adjacent ocean areas of the northwestern Atlantic and eastern Pacific, including the waters off the seaboards of the United States, as “Canadian” naval stations, where Canadian warships could operate without consulting the Admiralty. Laurier and Brodeur were delighted, for the British had in effect endorsed their argument that the new Canadian Navy was primarily a regional force for the protection of waters adjacent to Canada. In August 1911, the Naval Service of Canada also acquired a new name, when word arrived from London that the king had approved the government’s application to use the term “Royal Canadian Navy.” He also sanctioned the style already adopted by the dominion for its new cruisers, “His Majesty’s Canadian Ships.”

Niobe, as it turned out, did not go anywhere else. On the night of 31 July 1911, while returning from a port visit to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, it ran onto the rocks off Cape Sable. Had it not been for the coolness of the Royal Navy crew and the young Canadian recruits on board, it might well have been lost. It was later towed free and into Halifax, but repairs were not completed until December 1912. By that time the new navy was as badly stranded as the cruiser had been off Cape Sable.

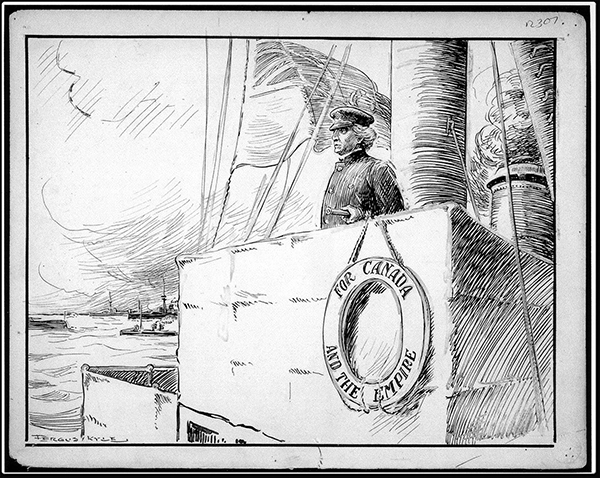

A November 1909 Toronto Globe political cartoon shows Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier at the helm of the future navy, navigating the conflicting nationalist and imperialist sentiments generated by the issue.

Laurier’s naval policy, much as he had tailored it to win political consensus, proved to be a political disaster. The difficulties had started in the fall of 1909, in response to the Laurier government’s position at the London conference. Leading English Canadian Conservatives were appalled that Laurier had refused to procure a dreadnought battle-cruiser, the type that the Admiralty said was most urgently needed. At the same time, F.D. Monk, the leading French Canadian Conservative, denounced the results of the conference for exactly opposite reasons. He charged Laurier with “Imperial drunkenness” for having been goaded by the Admiralty into a naval scheme that was more ambitious than the coastal defence and improved fisheries protection force envisaged in the parliamentary resolution.

From the beginning of the debate on the naval service in the House of Commons in 1910, Conservative leader Robert Borden endeavoured to unite his divided party by going on the attack. Borden now called for an immediate emergency contribution of cash to the Admiralty. At the same time, in a gesture that strongly appealed to both the pro-empire and French-Canadian wings of the party, he flatly rejected Laurier’s Naval Service Act. He particularly denounced the nationalist provision in the legislation that Canadian warships would be transferred to British control only with the explicit agreement of the Canadian government, and he drew a humiliating picture of British ships coming under enemy fire as Canadian warships stood helpless to intervene, awaiting orders from Ottawa. The bill, he concluded, was nothing less than a declaration of Canada’s separation from the empire.

The danger that the political controversy posed to the government became clear on 3 November 1910. A by-election in Drummond-Arthabaska, the former riding of Laurier himself and a long-time Liberal stronghold was lost to a little known nationalist candidate who presented himself as an opponent of Laurier’s “imperial” naval policy. Laurier’s grip on Quebec had been shaken. In the following months the government virtually ceased action for naval development, and did not place contracts for the construction of modern warships even though the complex process of tendering was completed. The Canadian Navy had in fact been overtaken by other events. Laurier’s government had succeeded in negotiating a “reciprocity” free trade agreement with the United States, and the prime minister called an election on the issue for 21 September 1911. Robert Borden’s Conservatives won that election by playing on fears of American economic dominance.

When the new Parliament met in March 1912, Robert Borden had reassessed the European situation and decided there was in fact no pressing need for the emergency contribution. He would, however, get rid of the hated Laurier legislation, and immediately cut the naval estimates from $3 million to $1.6 million. This was intended, as Desbarats noted in his diary, to keep the existing organization going on a “mark time” basis until the government could cooperate much more closely with the Admiralty than Laurier had done in framing a new Canadian naval organization.

Prime Minister Robert Borden leaving the Admiralty with First Lord Winston Churchill, July 1912.

On the very day Borden promised caution and due process in Ottawa, however, the First Lord of the Admiralty, now Winston Churchill, rose in the British House to reveal another, more ominous, expansion of the German dreadnought program. Britain had to make extraordinary efforts to maintain its margin against Germany. When Borden went to London in July 1912 to consult with Churchill on a “permanent policy,” Churchill asked the Canadian leader to make good on his earlier commitments to an emergency contribution. Borden agreed to provide $35 million to Britain, enough to build three of the latest “super dreadnoughts,” and in December 1912 introduced the Naval Aid Bill. The Liberals resisted furiously, and the government introduced closure for the first time in Canadian history to shut down debate. The Conservative majority in the Commons carried the bill on 15 May 1913.The Liberals, however, still had a majority in the unelected Senate, where two weeks later they defeated the bill.

Leading members of both parties had already been trying to achieve a compromise, and would continue to do so into the early months of 1914. Among the English Canadian politicians there was strong agreement that Canada must develop its own navy, and the deals discussed included such measures as the expenditure of part of the Naval Aid funds on expansion of the Canadian service, and the assignment of Canadian personnel to crew the dreadnoughts purchased for Britain with a view to Canada ultimately taking over the big ships. All of these proposals foundered on the Naval Service Act, on which neither party leader believed he could give way: Laurier had staked his party’s unity on that act, and Borden had staked his party’s unity on his promise to revoke it. This intransigence was not mere political posturing, but grew from fundamentally different visions of Canada and its future. Laurier most valued the country’s autonomy and freedom of action: to him, Canada might or might not participate in Britain’s wars depending upon circumstances. Borden by contrast looked to Canada assuming a more prominent role within the empire: in exchange for the automatic availability of Canadian naval forces to the Admiralty and such assistance as the emergency cash contribution, the British government must allow regular and continuous participation by a high-level Canadian representative in the decision-making bodies of the British government. Canada, in other words, although bound to participate in British wars, would have a key say in the policy that led to the British decision for war.

The fiasco of the Naval Aid Bill left the Canadian Navy in a state of limbo. The new government authorized no special efforts to obtain recruits, did not pursue the many deserters, and did not replace any of the borrowed Royal Navy personnel who departed on the completion of their two-year engagements. The strength of the RCN shrank from a peak of over 700 personnel (the borrowed British personnel and Canadian recruits) in the spring of 1911 to 330 by the spring of 1914.The first class of cadets at the college completed their course in December 1912, and did credit to the new service by all passing examinations set by the Admiralty, and achieving an average “higher than usual.” For lack of crew the Canadian cruisers could no longer sail to provide the sea training intended to follow the initial college program, so the Royal Navy stepped into the breach and accepted the cadets in the cruiser HMS Berwick. Already the cadets who entered in 1908 and 1909 and joined Niobe on its arrival had gone to England for further professional experience in HMS Dreadnought, the namesake of the new class of battleship. Even so the numbers of young men applying to the college fell, and there were only four students in the class that started in 1914.

Why maintain the two cruisers at all? The government asked that question of Kingsmill in October 1912. Even if the government decided not to acquire modern warships, he responded, there would still be a need for trained personnel, at the least to carry out basic coastal defence measures, such as the operation of coastal communications facilities, the establishment of “examination” services (small vessels that stopped merchant ships arriving at defended ports such as Halifax to ensure they were not disguised enemy vessels), and to operate armed civilian vessels for such functions as minesweeping and coastal patrols. The cruisers, even if permanently alongside, were good training facilities in peacetime, and, if properly maintained, in war could go to sea to help protect shipping leaving and arriving in Canadian waters.

In fact, one of the main activities of the Canadian Navy in 1912–14 was assisting preparations for coastal defence. The ships and crews of the fisheries protection service, the chain of coastal wireless stations, and resources of other departments, such as customs agents, were vital for these efforts. Starting in 1912, CGS Canada and other fisheries protection vessels began to carry out minesweeping and examination service exercises at Halifax, in conjunction with militia mobilization exercises at the forts, duties these same vessels and militia garrisons would begin to carry out in earnest starting in August 1914.

Commander Walter Hose, captain of Rainbow, was one of a group of seconded British-born RN officers who, despite the poor prospects of the Canadian service, chose to transfer to the RCN and played a crucial role in its survival. He later recalled this period in the Canadian Navy’s history as its “heartbreaking starvation time”:

In the spring of 1912 the Director of Naval Service visited Esquimalt….The old man seemed very depressed and was much afraid that the new Government would carry out the pre-election statement by Mr. Borden that he would repeal the Naval Service Act.

… I told him I thought, from all I had read, that it would be difficult to get popular support for a navy across this continental country, and I suggested taking a leaf out of the militia handbook and creating a citizen navy—a naval volunteer reserve with units across the country. The reply I got from him was “My dear Hose, you don’t understand—it can’t be done.”4

Hose nevertheless gave every encouragement to a group of young men who wanted to establish a naval volunteer unit in Victoria. In a well orchestrated lobbying effort, the unit won support from Sir Richard McBride, the Conservative premier of British Columbia, and groups of supporters for a volunteer force in other cities, including, notably, Vancouver where another unit was forming, and Toronto. The lobbying convinced Borden, who ignored protests from his French-Canadian members, and avoided the political pitfall of implementing Laurier’s legislation by establishing the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserves (RNCVR) by a separate order-in-council in May 1914, even though its terms, for three years’ service, were identical to provisions for a “Naval Volunteer Force” in the Naval Service

HMCS Rainbow watches over the SS Komagata Maru in Vancouver, July 1914.

The volunteers saw active service almost the moment they received recognition. Early in 1914 the Borden government agreed that Canada should take its turn in enforcing a ban on sealing in the Bering Sea that resulted from an agreement between Britain and the United States in which Canada had a strong interest. Rainbow was the only suitable Canadian or British ship available on the Pacific coast, and to augment the cruiser’s depleted crew, a detachment of Royal Navy sailors came from England, another from Niobe, and another from the volunteers in Victoria and Vancouver. Rainbow never reached the Bering Sea. On 20 July Hose received instructions from Ottawa to sail to Vancouver, where the Japanese steamer Komagata Maru had been immobilized for over two months. Aboard were 400 Indian Sikh passengers, who, as British subjects, demanded entry into Canada as immigrants, and refused to accept their ineligibility under Canadian regulations. Police who had attempted to board the vessel had recently been driven back by a hail of coal used by the passengers as projectiles. With the appearance of the cruiser, however, the Indians agreed to depart; the vessel sailed from Vancouver on 23 July, with Rainbow escorting it out of Canadian waters.

The cruiser returned to Esquimalt to complete preparations for the sealing patrol, but less than a week later, on 29 July 1914, Britain dispatched a “precautionary” telegram warning of apprehended war with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire. The frantic preparations that followed in response to reports, mostly false, that fast German cruisers were making for Canadian waters on both coasts had elements of a contemporary music-hall slapstick comedy. There was also courage and the potential for tragedy when, on 2 August, Rainbow rushed south in response to a request from the Admiralty to protect the small British sloop HMS Shearwater, then on passage north from Mexican waters where a German cruiser was known to be operating. Rainbow would have had no chance against the faster, better-armed German warship.

The larger point is that the Canadian Navy was able quickly to undertake basic measures for security of the coasts, particularly at Halifax and Esquimalt, thus providing the defended bases required for the British and other allied warships that soon arrived to protect shipping off shore. Rainbow on the West Coast and, after only a few weeks of recruiting, Niobe on the East Coast were able to take their place in these vital trade defence efforts. These were remarkable achievements for a new service that had effectively been abandoned by the government within a few months of its establishment.

Author: Roger Sarty

1 LAC, MG 26, G, Laurier Papers, Vol. 773, Notes of the Proceedings of Conference at the Admiralty on Monday, 9 August 1909, between representatives of the Admiralty and of the Dominion of Canada.

2 DHH, BIOG file, Rear-Admiral V-G Brodeur interview transcript.

3 LAC, MG 27, II, C4, Brodeur Papers, Brodeur to Lord Grey, 16 March 1911.

4 DHH, BIOG file, Rear-Admiral Walter Hose, “The Early Years of the Royal Canadian Navy,” 19 February 1960.