Executive Summary

Land Acknowledgement

The Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime (OFOVC) is located on the traditional, unceded and unsurrendered territory of the Anishinaabe Algonquin Nation, whose presence here reaches back to time immemorial. We also thank the Anishinabek, Huron-Wendat, Atikamekw, Cree, Dene, Metis, Sumas, Mathsqui, Kwantlen, Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations whose lands we visited in conducting our investigation.

Content Notice – Sensitive and Potentially Distressing Material

We acknowledge that the content of this report includes references to sexual violence and gender-based violence (GBV). These topics can be difficult to engage with, particularly for survivors, those who have witnessed harm, and individuals who support or care for those affected.

Please take care as you read. You are encouraged to engage with the material at your own pace and in ways that feel safe and manageable for you.

If you would like to access support, consider contacting the following resources:

- Victim Services Directory (to find services near you) https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/victims-victimes/vsd-rsv/index.html

- Support services for those affected by GBV https://www.canada.ca/en/women-gender-equality/gender-based-violence/additional-support-services.html

- Family violence resources and services Find family violence resources and services in your area - Canada.ca

- Hope for Wellness Helpline (available 24/7 to Indigenous people in Canada) www.hopeforwellness.ca, 1-855-242-3310

- Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime (for advocacy) www.crcvc.ca, 1-877-232-2610

- pflag Canada (for the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, family, friends and allies) https://pflagcanada.ca/contact/

If you have experienced criminal victimization and you believe your rights under the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights have not been respected, you can contact us:

Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime

www.victimsfirst.gc.ca

1-866-481-8429

Table of contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

FOREWORDS

INTRODUCTION

Guiding Frameworks

Methodology

Myths and Stereotypes

TOPICS

Reporting to Police and Investigations

R v. Jordan

Therapeutic Records

Cross-examination

Testimonial Aids

Victim Impact Statements, Sentencing, Corrections and Parole

Restorative & Transformative Justice

Legal Representation and Enforceable Rights

Access to Services

Data and Accountability

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

GRATITUDE

ANNEXES

A. Recommendations

B. Myths and Stereotypes in Sexual Assault Caselaw

C. Our Actions on MMIWG Calls for Justice

D. Selected Written Submissions

Canadian Centre for Child Protection

Ontario Native Women’s Association

Survivor Safety Matters

Executive Summary

“Believe us. It’s that simple. When we tell you something happened, don’t blame it on what we were doing or what we were wearing or if we ‘deserved it’ or not. Regardless of what we were doing or how we were dressed, we didn’t deserve what happened to us.” [1]

Sexual violence remains one of the most underreported crimes in Canada. Despite decades of reform, only 6% of sexual assaults are reported to police.[2]

Survivors of sexual violence fear being disbelieved, retraumatized, and harmed if they report. This investigation was prompted by long-standing concerns raised by survivors, advocates, and legal professionals about persistent barriers to justice and the urgent need for reform.

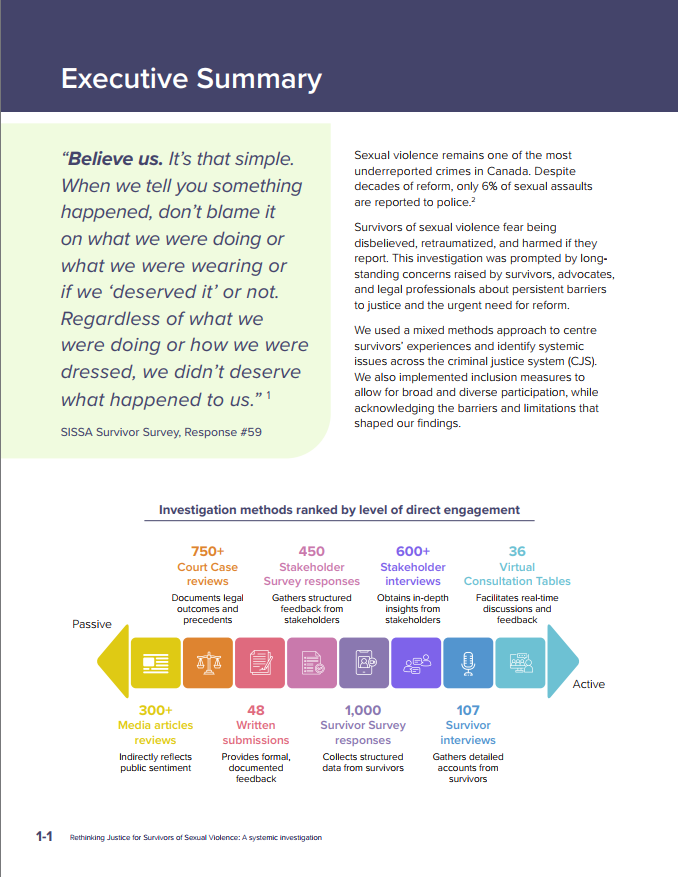

We used a mixed methods approach to centre survivors’ experiences and identify systemic issues across the criminal justice system (CJS). We also implemented inclusion measures to allow for broad and diverse participation, while acknowledging the barriers and limitations that shaped our findings.

These frameworks informed both the design of our investigation and our evaluation of how survivors of sexual violence are treated while navigating the CJS. In particular, we noted:

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

“Steps must be taken to better respond to the needs of Indigenous victims.” [3]

First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, specifically women, girls, and 2SLGBTQIA+ people, are overrepresented as victims of crimes – violent crimes,[4] sexual crimes,[5] and gender-based crimes.[6]

Our investigation sought to incorporate this understanding into every aspect of our work. In undertaking our investigation, we considered the 2019 National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Calls to Justice about health and wellness, Indigenous-specific victim services, sustainable funding for Indigenous-led services, education and traditional knowledge, violence prevention and community safety.[7]

Myths and stereotypes

“A number of rape myths have in the past improperly formed the background for considering evidentiary issues in sexual assault trials.” [8]

The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has condemned the use of rape myths and stereotypes in sexual assault trials, recognizing their harmful effects on survivors and on judicial outcomes.

Sexual assault is a crime of power and control. Most sexual assaults occur between people who know each other.

There is no single or “typical” way a survivor behaves during or after a sexual assault.[10] Reactions such as freezing, delayed reporting, memory inconsistencies, emotional numbness, not telling friends, feeling shame, or maintaining relationships with perpetrators, are misunderstood as credibility issues but they are actually normal responses to trauma.

Pervasive myths and stereotypes significantly harm survivors by undermining their access to justice, safety, and healing. Myths and stereotypes reinforce stigma, silence survivors, and perpetuate systemic inequalities.

Topics of our investigation report

Our report touches on 10 broad topics:

1. Reporting and investigations

“Reporting sexual violence should not open the door to suspicion, delay, or further harm.” [11]

Systemic, practical, and identity-based barriers make reporting unsafe, inaccessible, even unthinkable, and prevent many survivors from reporting. Many survivors do not believe anyone will take them seriously. They have an intense fear of disbelief, shame, and judgment. When they do report, many survivors do so from a deep sense of responsibility to protect others.

Survivors in rural, remote, and northern communities described additional barriers to reporting. Similarly, Indigenous, Black, and 2SLGBTQIA+ survivors, and survivors with disabilities experience additional and intersectional barriers to reporting.

While some survivors had poor experiences with police, others noted improvements in police communication and access to case-related information.

2. R v. Jordan

“I don’t think there is anything worse for a victim than to have a trial stayed.” [12]

R v. Jordan [13] created a regime with specific time frames that protect the right of an accused to a trial within a reasonable time. It has had unintended devastating consequences for survivors and their families. Serious sexual assault charges, even against children, are being stayed, sometimes after survivors have already endured painful cross examinations or disclosure of private records.

The current approach to R v. Jordan is compromising access to justice, violating the rights of victims of crime, and undermining public confidence in the judicial system in Canada.

3. Therapeutic records

“It was the worst part about the entire awful thing... I disclosed other sexual abuse including incest that I never wanted anyone to know about. I was suicidal and severely depressed and desperately wished I had either never done counselling or never reported. In the future I will advise other sexual assault victims to pick one or the other, never both.” [14]

Therapeutic interventions can help people who have experienced trauma. Survivor therapeutic records contain personal information that many people would not want shared with anyone, particularly with the person who harmed them.

The third-party records regimes were enacted to require courts to conduct a balancing exercise before producing complainants’ private records in cases of sexual assault.[15]

The risk of those records being disclosed in court means that many survivors felt like they had to choose between justice or getting mental health help. The threat of an aggressor gaining access to a survivor’s therapeutic records is a risk to the health and safety of survivors.

We believe the current records regime causes disproportionate harm to survivors compared to the potential benefit for the accused.

4. Cross-examination and trial fairness

“To put a bulldog there to rip the person to shreds is barbaric.” [16]

Despite important amendments to the Criminal Code, myths and stereotypes still underlie some lines of questioning of cross-examination. Some survivors reported that cross-examination was worse than the sexual assault itself and that even with a conviction they regret ever having reported.

Cross-examination can be profoundly traumatizing for children, who often have to testify twice because of preliminary hearings. Child and youth advocacy centres provide child-friendly and safe spaces for children to testify and should be more widely accessible.

Complainants with disabilities and with communication needs can experience profound harms from cross-examination. Their Charter right to equality is at risk when they don’t have access to adequate communication aids.

5. Testimonial aids

“Make testimonial aids an automatic practice for all victims of sexual assault (not just children) and enshrined in Crown guidelines.” [17]

Testimonial aids are tools provided in the Criminal Code that help victims and witnesses participate in the criminal justice process more safely, reduce trauma, and enable the truth-seeking function of the court. The SCC indicates that testimonial aids “facilitate the truth-seeking function by allowing a complainant to be able to give evidence more fully and candidly.” [18]

The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) provides the right to request testimonial aids. However, if survivors are not aware of them, they don’t know they can request them.

Access to testimonial aids varies across the country, depending on jurisdiction and location. Survivors and stakeholders shared that testimonial aids should be automatically offered.

6. Victim impact statements, corrections and parole

“Even my victim impact statement was redacted. It was all blacked over. That was my last hope to be heard. I read it like a prayer to the Creator in hopes I would at least be heard by the Creator.” [19]

A Victim Impact Statement (VIS) is a statement from a survivor written prior to sentencing, presented to the Court. It becomes part of the evidence which must be considered by the judge in determining the sentence of the accused.

The VIS regime in Canada has led to increased victim participation, increased victim satisfaction with the criminal justice system, and increased acceptance among criminal justice professionals of victim input.

Victim Impact Statements are often redacted, which limits or eliminates the authenticity of the survivor’s voice. We believe that redactions of victim impact statements should be limited.

Survivors often have little information about their rights during and after sentencing. They don’t know that they have to register with Correctional Service Canada (CSC) or the Parole Board of Canada (PBC) to get information about federal offenders. The onus is on victims and survivors – those who have suffered harm - to navigate a complicated system. We believe that survivors should receive proactive information about their rights during and after sentencing.

7. Restorative and transformative justice

“We see and hear of a need for restorative and transformative justice approaches as options for survivors and as creative responses to survivors’ access to justice needs.” [20]

Restorative justice (RJ) is an approach to justice that seeks to repair harm. RJ is a voluntary and consent-based approach, and can allow survivors to participate more safely, on their terms.

RJ offers many alternative approaches. Many RJ programs have drawn their principles from Indigenous legal traditions, which have been used by Indigenous peoples to resolve disputes for thousands of years.[21] RJ values are consistent with and have been informed by the beliefs and practices of many faith communities and cultural groups in Canada.

RJ remains largely inaccessible to survivors of sexual violence due to provincial and territorial policies that prohibit its use.

Some advocates have concerns that RJ shifts gendered violence back into the private sphere. Others believe it is a much better alternative to the criminal justice process and that survivors should be offered options and information to make informed decisions about what is best for them.

8. Independent legal advice and enforceable rights

“When I was debating about reporting the rape, I researched online and found that BC had an amazing service to provide victims of sexual crimes with up to three hours of free legal advice. I took advantage of that and it was amazing. Phenomenal. The lawyer was so completely helpful and understanding - I can’t even think of all the words to say how supported I felt by them.” [22]

Victims have rights under the CVBR and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Victims need access to independent legal advice and representation to protect and assert their rights.

The CVBR is a significant advancement for victims and survivors of crime in Canada, marking a culture change in Canada’s legal framework. The broad range of rights it endows, along with its primacy over other legislation, gives it the potential for considerable impact. Consistently applied, it would provide victims with a stronger voice in the criminal justice system.

Like rights for people accused of a crime, victim rights should be firmly entrenched in policy and practice, consistent and reliable, no matter who is providing the service or where the survivor lives.

Indigenous children, Black children, children with disabilities, racialized children, 2SLGBTQIA+ children, children in care, and children living in rural and remote places face even greater hurdles accessing their rights and are at risk of secondary trauma in the criminal justice process.

9. Access to services

“I wish the RCMP had a list of supports to give survivors. The responsibility to orient myself and search for help after a traumatic crime has taken so much time and energy. I wish there were more supports for victims to teach us how to build a team and how to ask for help.” [23]

We heard tremendous positive feedback about service providers who sat with survivors through a trial,[24] advocated for them, explained things, listened, and treated them with dignity. In interviews with survivors, several people said they believed the service providers had saved their lives.[25]

Support services for survivors are struggling to keep up with the increase in demand with minimal funding. Survivors of sexual violence should always have access to support services that treat them with dignity and respect – regardless of sex, gender identity, race, culture, language preference, age, geographic location, dis/ability, or other characteristics – consistent with the principles of procedural justice. When victims lack support, they may face significant trauma. A lack of support can also impact their decision to engage in the criminal justice process.

Children are an equity-seeking group similar to other marginalized groups.[26] Whether or not a child has access to justice should not depend on their individual identity or where they live. Child and youth advocacy centres are a vital and evidence-informed model that provide coordinated, trauma-informed support to children navigating the criminal justice system that should be more widely accessible.

10. Data and accountability

“Data collection needs to be improved, and we need to collect data consistently. It is hard to identify gaps

without reliable data.” [27]

Police-reported crime data and victimization surveys have advanced our understanding of victims’ issues across Canada. However, there are big gaps in publicly available data. Data gaps can allow problems to stay undetected.

Enhanced data collection that is accessible and inclusive can help create meaningful solutions and ensure systemic change for the criminal justice system. By capturing disaggregated data and ensuring evidence-based approaches and practices, we can better understand and serve communities, achieve efficiencies, and advance accountability.

There are also important calls to increase the quality of data through an intersectional lens. The Assembly of First Nations released a National First Nations Justice Strategy in June 2025 that calls for sovereignty over data and efforts to increase the quality of data through an intersectional lens.

Sexual violence has no place in our society

Many improvements have been made over the years to the criminal laws, programs, and services for survivors of sexual assault. Lawmakers are careful in their consideration of equity, justice, and human rights when amending and creating laws and policies. We heard from many inspiring people who want to make the system better.

We also know that even with good laws and policies, there are often unintended impacts that are invisible and even unimaginable to lawmakers. We know that depending on where a person lives in Canada, laws and policies are applied differently. We know that depending on a person’s identity or status, laws and policies are applied differently. We know that there is still work to do to address the MMIWG Calls to Justice.

We can do better.

Partners and Contributors

We wish to properly recognize those who contributed to this report; there are so many. Whether by granting us an interview, completing a survey, participating in a consultation table, or providing a written submission, your input was invaluable. We are grateful to all of you for generously lending us your voice. Your willingness to share made it possible for us to learn, reflect, and carry this work forward with greater understanding. We have dedicated a section of this report – Gratitude - to honour and acknowledge your contributions with the respect you deserve.

Our Expert Advisory Circle

An Expert Advisory Circle (EAC), chaired by Sunny Marriner, has been convening to support this investigation, enhancing its effectiveness and inclusivity.

The EAC was composed of 16 members from across Canada, including survivor-advocates, legal professionals, clinicians, frontline anti-violence workers, and academics. The EAC played a central role in guiding the investigation, offering insights on emerging issues, identifying gaps, and validating findings.

The time and expertise of these amazing individuals ensured that voices of survivors remain at the forefront and that a diverse range of perspectives and expertise were included in our investigative process.Realizing the requests for support and the demands you and your respective organizations face, words cannot express how thankful we are to each of you for your advice and contribution.

We were honoured to have Sunny Marriner serve as Chair of the EAC. Sunny brings extensive experience in community and legal responses to sexual violence and has served as an expert witness in sexual assault trials and human rights tribunals. In 2016, she established Canada’s first Violence Against Women Advocate Case Review program, which has since spread to communities across Canada.

| Sunny Marriner | Violence Against Women Advocate Case Review |

| Corinne Otsie | Association of Alberta Sexual Assault Services |

| Deepa Mattoo | Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic |

| Janet Lee | The Journey Project |

| Jessica Bonilla-Damptey | Sexual Assault Centre Hamilton & Area |

| Joanna Birenbaum | Birenbaum Law Office |

| Kimberly Mackenzie | Territorial Nurse Practitioner (Northwest Territories) |

| Maggie Fredette | Centre d’aide et de lutte contre les agressions à caractère sexuel de l’Estrie |

| Mandy Tait-Martens | Ontario Native Women’s Association |

| Naomi Parker | Luna Child and Youth Advocacy Centre (Calgary) |

| Nneka MacGregor | WomenatthecentrE |

| Pam Hrick | Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF) |

| Rita Acosta | Mouvement contre le viol et l’inceste |

| Robert S. Wright | African Nova Scotian Justice Institute |

| Tanya Couch | Survivor Safety Matters |

| Valerie Auger-Voyer | Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada |

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #59

[2] Statistics Canada conducts the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety every 5 years. It is a large victimization survey that collects self-reported data on criminal victimization from all provinces and territories. It includes questions on whether people reported a crime to police.

[3] Policing Services. (2025, April 2). Guiding principles for sexual assault investigations - Province of British Columbia.

[4] Perreault, S. & Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics. (2022). Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada.

[5] The Assembly of First Nations (AFN). (2025b, May 22). Murdered & Missing Indigenous Women & Girls - Assembly of First Nations. Assembly of First Nations.

[6] Heidinger, L. & Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics. (2022). Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada.

[7] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Calls to Justice. (2019). Calls to Justice 1.5, 1.6, 1.9, 4.7, 5.3, 5.5 (iii), 5.11, 5.13, 5.24, 9.1, 9.2, 14.6, 14.8, 14.13.

[8] R v. Osolin, 1993 CanLII 54 (SCC), [1993] 4 S.C.R. 595, at para 670

[9] Canadian Women’s Foundation. (2024, August 16). Sexual Assault & Harassment | Violence prevention | Canadian Women’s Foundation.

[10] R v. D.D., 2000 SCC 43, at para. 65

[11] SISSA Survivor Interview #39

[12] SISSA Survivor Interview #39

[13] R v. Jordan., (2016) SCC 27 (CanLII)

[14] SISSA Survivor Interview #461

[15] Heather Donkers, An Analysis of Third Party Record Applications Under the Mills Scheme, 2012-2017: The Right to Full Answer and Defence versus Rights to Privacy and Equality, 2018 41-4 Manitoba Law Journal 245, 2018 CanLIIDocs 192.

[16] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #21

[17] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #404; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #228

[18] R v. Levogiannis, 1990 CanLII 6873 (ON CA), at para 35; R v. J.Z.S., 2008 BCCA 401 (CanLII)

[19] SISSA Survivor Interview #439

[20] SISSA Stakeholder Interview, Response #34

[21] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[22] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #192

[23] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #222

[24] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #222

[25] Summary of themes from multiple SISSA interviews and survey responses.

[26] SISSA Stakeholder Interview, Response #027

[27] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #169