Legal Representation and Enforceable Rights

“While the substantive law regarding sexual assault in Canada has undergone positive reform over the last 30 plus years in favour of women’s equality, ……the government has failed to implement procedures that provide complainants with consistent protection, information and participation regarding the criminal process. These missing procedures could help prevent retraumatizing experiences, guard against harmful applications of gender stereotypes and rape myths and accommodate psychological trauma. However, the government’s failure to implement these crucial procedures has resulted in a criminal process that is harmful to female sexual violence victims, which make up 86% of all victims of sexual offences. This failure amounts to adverse impact discrimination against women.” [1]

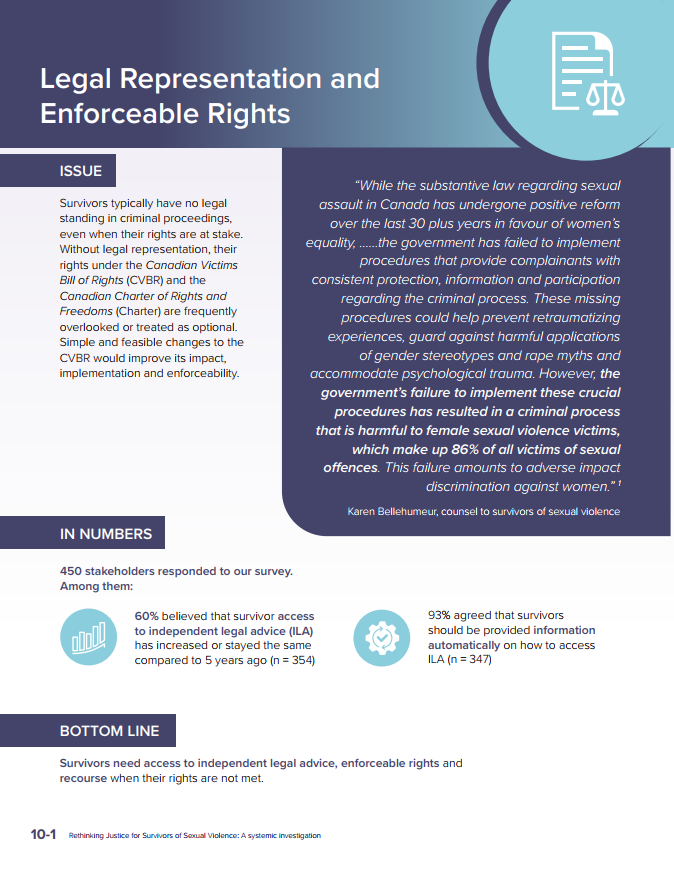

ISSUE

Survivors typically have no legal standing in criminal proceedings, even when their rights are at stake. Without legal representation, their rights under the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter) are frequently overlooked or treated as optional. Simple and feasible changes to the CVBR would improve its impact, implementation and enforceability.

IN NUMBERS

450 stakeholders responded to our survey. Among them:

- 60% believed that survivor access to independent legal advice (ILA) has increased or stayed the same compared to 5 years ago (n = 354)

- 93% agreed that survivors should be provided information automatically on how to access ILA (n = 347)

KEY IDEAS

- Legal representation matters. Survivors need access to independent legal advice (ILA) and independent legal representation (ILR) to meaningfully assert their rights

- Child victims face unique harms. Children are especially vulnerable to secondary trauma when their rights are ignored or unsupported

- The CVBR can be a powerful tool. It needs to be strengthened and enforced

- Rights must be enforceable. The CVBR and Charter rights should not be treated as optional or symbolic

- Federal leadership is essential. The federal government must take responsibility for CVBR compliance and ensure its primacy is respected

BOTTOM LINE

Survivors need access to independent legal advice, enforceable rights and recourse when their rights are not met.

RECOMMENDATIONS

8.1 Fund legal representation when victims’ rights are at stake: The federal government should continue to fund Independent Legal Advice (ILA) and Independent Legal Representation (ILR) programs whenever a victims’ Charter or CVBR rights are engaged within the criminal justice system. This includes for testimonial aids applications, records applications, preparation of victim impact statements, and parole hearings.

8.2 Provide information proactively: The federal government should immediately amend the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) to remove “on request” from victims’ rights to information.

8.3 Create meaningful enforcement powers: The federal government should immediately amend the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) to allow victims to challenge violations to their rights by creating standing, appeal rights and a remedy from federal agencies in order to allow victims to challenge violations of their rights.

8.4 Show CVBR consistency in proposed legislation: The federal government should immediately amend the Department of Justice Act to require that the Minister examine every Bill to ascertain whether any of the provisions are inconsistent with the purposes and provisions of the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights and report any inconsistency to the House of Commons at the first convenient opportunity.

8.5 Show CVBR implementation in proposed legislation: The federal government should immediately amend the Department of Justice Act to require that the Minister of Justice shall table, for every Bill introduced in or presented to either House of Parliament by a minister or other representative of the Crown, a statement that sets out potential effects of the Bill on the rights that are guaranteed by the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights.

8.6 Clarify the analysis of the Charter rights of victims of crime: The federal government should amend the Department of Justice Act to require that Charter Statements include an analysis of how legislation may affect the rights of victims of crime under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Background

Independent legal representation (ILR) is “a retainer in which a licensee (lawyer or paralegal) acts as the client’s legal representative for a specific matter or transaction. Licensees (lawyers or paralegals) providing ILR enter a standard lawyer-client or paralegal-client relationship and must adhere to the same professional obligations owed to all clients.” [2]

Independent legal advice (ILA) is “a limited scope retainer in which a licensee (lawyer or paralegal) provides objective and unbiased legal advice to clients about the nature and consequences of a specific decision to be made but does not otherwise represent the client with respect to their matter or transaction.” [3]

The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights came into force on July 23, 2015, representing a monumental step in acknowledging and upholding the rights of victims of crime within Canada's justice system. Victim rights in Canada have progressed slowly but steadily, with the CVBR marking a key step toward a fairer justice system for all.

- “The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights(CVBR) …. established statutory rights at the federal level for victims of crime. Through the CVBR, victims of crime have the right to information, protection, participation, and to seek restitution. Victims can also make a complaint if they believe their rights have been infringed or denied.[4]

- The CVBR limits these rights: “These rights must be applied in a reasonable manner so that they are not likely to interfere with investigations or prosecutions, endanger someone’s life or safety, or injure national interests such as national security.” [5]

The CVBR is enforced through a complaint mechanism. The OFOVC receives complaints once a federal agency has decided on a survivor’s initial complaint.

- “A victim may file a complaint if they are of the opinion that their rights under the CVBR have been infringed or denied (i.e. not respected) by a federal agency or department during their interaction with the Canadian criminal justice system. When it is a federal government department or agency about which a victim would like to complain, they should use the internal complaint system of that department or agency. If a victim has a complaint about a provincial or territorial department or agency, including police, prosecutors, or victim services, they may file a complaint under the laws of the province or territory.” [6]

Our investigation

Specific actions

We held two consultation tables specific to the issue of ILR/ILA. We asked survey questions about the CVBR including information rights, protection rights, participation rights and enforceability.

In 2024, the Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime published an Open Letter to the Government of Canada: It’s time for victims and survivors of crime to have enforceable rights.[7] Our recommendations include:

- When victims report a crime to the police, tell them their rights – don’t expect them to ask.

- When ILA is available, tell victims so they are better protected.

- When a restitution order is made, help the victim collect the funds.

- Ensure testimonial aids are not unreasonably withheld.

- Monitor the implementation of victim rights through updated statistical measures and commit to ongoing evaluation and training.

“The Act does not provide a comprehensive national solution, in part because it provides a limited complaint mechanism for federal agencies only. This has the effect of promising rights but not providing a means to enforce them.” [8]

What we heard

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Survivors need independent legal advice and representation programs

“Had I left it in the hands of the officer I reported to and not advocated for myself and accessed the free legal advice program, I strongly believe nothing would have happened and my abuser who is in prison currently would still be free on the street harming more people. I had this experience in one of the biggest urban centers in Canada and could not imagine reporting somewhere rural with less resources.” [9]

We heard that stakeholders believe that ILA/ILR can help survivors make informed decisions and be adequately supported in their path forward.

“We hope to see the Federal Ombudsman advocate for an expansion of ILA to ensure that all survivors, regardless of their geographical location across Canada, can have access to free legal advice to assess their options following sexual assault.” [10]

“The most obvious change that is needed is why do victims not have legal representation in the criminal system? The Crown represents the queen, the government, the state etc.” [11]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Positive experiences with ILA and ILR from survivors and stakeholders[12]

“When I was debating about reporting the rape, I researched online and found that BC had an amazing service to provide victims of sexual crimes with up to three hours of free legal advice. I took advantage of that and it was amazing. Phenomenal. The lawyer was so completely helpful and understanding - I can’t even think of all the words to say how supported I felt by them.” [13]

Some survivors told us that they had an excellent experience with ILA/ILR and that it made a big difference for them.

- We heard that having a lawyer to represent them, reduces anxiety and helps them understand the process.[14]

- We heard that it is extremely beneficial for survivors to be given ILA before reporting.[15]

We heard from Crowns that they feel conflicted knowing that their role does not include representing the victim but they can see, from their experience and expertise, the complainant would benefit from legal advice or representation. This adds to the vicarious trauma of many Crowns and court workers in this field.[16]

Without ILR, the Charter and CVBR interests of survivors are not always being heard

We heard a judge at a conference on victims’ rights indicate that they are relying on parties to make submissions about victims’ rights and interests.[17] This judge did not feel empowered to bring this perspective if it was not argued by the parties.

- It is our observation that, if victims are rarely represented in Court proceedings, victims’ rights and interests will be rarely considered by the Court.

- When survivors don’t have standing, courts make decisions without hearing from all the parties who have a genuine interest in the case.

Lack of ILR also means that there are limited opportunities to refine and develop the law about victim rights.

- The current limited jurisprudence from the CVBR has come from represented survivors, Crowns and advocates – not from accused, self-represented or unrepresented complainants

- ILR will add to the body of jurisprudence which refines and explores the rights of victims of crime. In our common law tradition, this is a necessary part of an effective legal system

- ILR will develop jurisprudence to guide an understanding of victims’ rights unique to the Canadian constitutional, bijural and bilingual context

- With ILR, CVBR and Charter rights for survivors will be considered more often and lead to a fairer balance within the criminal justice system. This will increase public respect for the justice system

Justice Canada Pilot Projects

Between 2016 and 2019, several provinces and territories accessed Justice Canada funding to set up their own ILA/ILR projects.[18] In Budget 2021, the Government of Canada announced an investment of $48.75 million over five years through two Justice Canada programs to ensure access to free ILA and ILR for survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual assault.[19]

- ILA: provides survivors with tailored legal advice regarding their options

- ILR: provides survivors with legal counsel to represent their interests in specific instances as provided in the Criminal Code of Canada (i.e., in other sexual history and private records applications in a sexual assault trial)

Justice Canada has two funds supporting ILA and ILR. The Justice Partnership and Innovation Program (JPIP)[20] supports the development and implementation of pilot models of ILA and ILR for survivors of IPV. The Victims Fund[21] supports pilot models of ILA and ILR for survivors of sexual assault.

- This funding expires in March 2026 which will leave thousands of survivors without access to these resources unless it is renewed.

- We recommend that this funding be immediately renewed.

Qualitative Research Results

Justice Canada conducted in-depth qualitative interviews[22] with 18 not-for-profit organizations in five jurisdictions (Prince Edward Island, Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, and British Columbia) who had been funded for ILA/ILR projects. [23]

| Strengths: | Challenges: |

|---|---|

|

|

Innovative ILA / ILR programs

Ontario. The first ILA program for survivors of sexual assault was established by the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General in 2016 across Ontario in several pilot projects.[24] The program is currently delivered by the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic and is open to all women, men, trans, and gender-diverse people, aged 16 years and older, living in Ontario, and where the sexual assault occurred in the province. Eligible applicants can receive up to four hours of legal advice.[25]

- We learned about an effective Justice Canada funded program, Your Way Forward,[26] where nine Ontario legal clinics provide multidisciplinary and holistic legal services to survivors of sexual violence and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV).[27]

- Their overarching goal is to increase access to just outcomes for survivors of sexual violence and intimate partner violence.

- Survivors do not have to demonstrate financial need or meet legal aid thresholds to access these services. These clinics are filling an important gap in access to justice for survivors of GBV.[28]

New Brunswick. We heard of the promising ILA/ILR programs, such as the ILA Plus Program offered by Sexual Violence New Brunswick. The program provides direct advocacy and support for clients who are currently undertaking or thinking about undertaking legal steps relating to sexual violence.[29]

- When survivors are connected with a lawyer for other sexual history or private records applications, advocates and survivors believe they are more likely to have their rights respected.[30]

- When defence counsel issues a subpoena for private records, the client is allowed to have a lawyer, but they cannot always afford to hire a lawyer.[31] These programs make a difference for survivors.

Newfoundland and Labrador. The Journey Project[32] is an inspiring and innovative collaboration between two leading non-government organizations (NGO)s offering free legal information and system navigation to any person in NL who has experienced sexual violence or intimate partner violence.

- Journey Project staff or collaborators may provide legal advice, accompany a survivor to court, hospital or police station, offer referrals to community services and take third party police reports.

ILA/ILR are not accessible to all victims across Canada

We heard that funded legal representation is not available in some provinces/territories.[33]

- In Manitoba for example, we heard that some advocates believe that the application process for ILR is unduly difficult.[34]

- Demographic gaps – some programs limit eligibility requirements to survivors residing in specific areas.[35]

- A survivor who moves from one province to another before a trial takes place can become ineligible for funding.[36]

Funding limitations. We heard that ILA/ILR programs are underfunded, which impacts the quality, scope and reach of services.

- Programs may have to prioritize certain cases over others.[37] Victims may receive support for a limited number of hours (such as 4-5 hrs).[38]

- Some organizations with funded programs have had requests far outstripping their ability to fund.[39]

- We heard that compensation for independent counsel is inadequate, which creates a shortage of lawyers willing to do this work[40] and delays in connecting survivors with independent counsel in an already long and difficult process.[41]

- Victims may feel unsupported if they receive ILA but no ILR. ILA is a good start, but then victims may be left to represent themselves.[42]

Additional benefit

In jurisdictions where there is funded legal advice for other sexual history and private records applications, an inadvertent benefit of these applications is a solicitor-client privileged relationship for a survivor. The survivor can ask questions about the criminal law and criminal procedure and get an understanding of the defence’s actions.

List of ILA/ILR lawyers requires updating. We learned that not all lists of ILA/ILR funded jurisdictions are up to date with legal professionals with training in sexual assault law[43] as well as with knowledge on potentially overlapping issues such as immigration, family, and employment law, and who are willing to take cases.

- We heard that Ontario’s ILA list included lawyers who were not willing or able to take cases or who were retired, and that the list did not allow new lawyers to be added. Recently we learned that the list was updated in June 2025.[44]

Age restrictions. We learned that ILA in Ontario is not available to survivors under 16 and child protection services do not offer legal advice to children.[45]

- We heard that organizations such as Justice for Children and Youth[46] provide services to help address this gap.

Increased awareness is needed. Providers in the gender-based violence service sector may not be aware of ILA programs.[47]

- Some survivors told us they weren’t aware of ILA until they discovered the service online and advocated for themselves.[48]

Prioritizing resources

When considering criminal justice policy options, it is important to consider the relative impact of spending on public safety.

- In 2023-24, the cost to maintain a single offender in a federal maximum-security facility for one year was $231,339.[49]

- This amount is equal to 3 full-time counsellors in sexual assault centres or the costs of ILA for 365 survivors in Ontario.[50]

Wouldn’t another lawyer just add more delays?

“The system cannot handle having a third lawyer present throughout the whole of every trial.”[51]

Stakeholder survey responses. We asked stakeholders for their views on legal representation for survivors. A common concern was that additional legal representation would cause significant delays[52] that would fall on the Crown,[53] lengthen and complicate proceedings,[54] and risk overrunning R. v. Jordan timelines.[55]

We heard that there would be a delay while the complainant’s counsel is appointed, then again when setting dates for hearings and trials in three lawyers’ calendars.[56]

“I instinctively want to agree that victims should have legal representation, but these proceedings are already so complex that even relatively simple cases quickly become unwieldy and risk overrunning the Jordan deadlines. Adding a third voice to the debate exacerbates this problem exponentially.” [57]

We also heard contrasting positions from others who felt ILA/ILR would save time and reduce delays.

- Senior sexual assault Crowns and defence counsel told us that timely and early involvement of counsel for survivors can save time, simplify issues and reduce delays. For example, counsel for survivors can advise survivors on other sexual history and private records applications which can lead to uncontested disclosures, reduce the volume of records, simplify submissions and consolidate applications.

Child victims face additional trauma when their rights are ignored

We heard:

- the CJS is not equipped to take a statement from children and youth with disabilities who are non-verbal, or support them to testify, which causes charges not to be laid[58]

- Crown prosecutors and judges need to be educated on 2SLGBTQI+ children and youth. One judge said to a transgender youth they could not understand how they were sexually assaulted because they did not know what transgender meant[59]

- Special investigative policing teams are available for child victims, but in remote areas the trained specialist would have to travel to where the person is, which causes delay[60]

Children who experience sexual violence often face additional trauma when they engage with the criminal justice system. They may experience isolation, anxiety, confusion, and long-term harm, particularly due to delays, lack of support, or adversarial procedures.[61]

Secondary victimization occurs when the criminal justice response re-traumatizes victims, due to:

- Lack of information provided to the victim

- Absence of enforceable legal rights for victims

- Disregard of the victim’s needs throughout the court procedures by the authorities

- Serious sexual assault charges, including against young children, being stayed

The consequences of secondary victimization might be even greater for children because of their inherent vulnerability.[62]

- One stakeholder noted that, as childhood and teenage years are pivotal times in one’s life, long court processes can become their identity.[63]

Isolation from caregivers

Children are dependent on adults and caregivers. When a child is abused and the CJS gets involved, children are often isolated from their support systems.

- Police and legal professionals may instruct parents not to discuss the abuse with their child to avoid influencing the case. This can be devastating both for the child and their caregivers who feel unable to provide comfort to the child during a time of crisis and emotional upheaval.

- Parents may not know the details of what happened to their child until it is revealed in court.[64]

- This forced distance can dysregulate both the child and the parent, leaving the child without emotional support when they need it the most.[65]

Parents have no legal standing to intervene when procedures become emotionally overwhelming for their child. This forced silencing of their caregiving can last for years while awaiting trial and can have even longer-term repercussions that go far beyond the trial.

Intersectional Barriers

Indigenous children, children with a disability, racialized children, 2SLGBTQI+ children, children in care, children living in rural and remote places face even greater hurdles accessing their rights and are at risk of secondary trauma as they try and adjust to the CJS.[66]

Mother of a youth asked to leave courtroom

“Court happened 2 yrs after the rape. I was 16 years old and being cross-examined by defence. My mother was asked to leave the court room because she mouthed the words, “It's OK, baby.” They said she was coaching me. I learned never to report rape again. I've been raped since but will never go to the police about it ever.”[67]

Emerging practices to safeguard procedural fairness for survivors

Specialized sexual assault courts

- Québec is the first Canadian province to enact a specialized court to exclusively address sexual violence matters. Pilots began in 2022 and rolled across Québec. Québec politicians pointed to the South African specialized court model when they proposed the idea of a sexual offences court for the province in 2018.[68]

- South Africa has a national sexual offences court initiative. Piloted in Wynberg in 1993, early successes included a victim-centred approach, coordination and integration with service providers, and improved processes that contribute to increased reporting and conviction rates.[69]

- New Zealand sexual violence court pilot had positive results: dedicated judges, less retraumatization among survivors, control of cross-examination.[70]

- Rape Crisis Scotland supports the establishment of a specialist sexual offences court, which was under consideration by the Scottish Government in 2023.[71]

Crown review. A Crown review scheme allows survivors of crime to request a review of certain decisions made by the police or a prosecution service. Specifically, it provides a process for victims to challenge decisions like not to prosecute or to discontinue a case. The scheme aims to ensure victims have a voice and a mechanism to seek reconsideration of decisions that may not align with their expectations or the evidence.

British Columbia. The Final Report of the Independent Systemic Review on sexual violence and intimate partner violence recommended that an automatic review mechanism for sexual violence case be implemented, as well as a complaint mechanism for Crown conduct and decisions.[72]

England and Wales. In 2013, England and Wales’ Crown Prosecution Service introduced an internal administrative review process (the Victims’ Right to Review Scheme, “VRR”) for victims to seek recourse when a decision is made not to prosecute.[73] Victims have a right to review decisions not to charge and to discontinue or otherwise terminate proceedings.

Judicial review is also available to victims when a decision is made not to prosecute, but such a request will only be considered if the decision has already been reviewed under the VRR scheme.

- Judicial review is broader than the VRR scheme as it allows decisions to prosecute to be challenged.

- The High Court will intervene “only in very rare cases” involving prosecutorial decisions generally,[74] and when a review has been conducted under the VRR scheme, it is highly unlikely that judicial review will succeed.[75]

- From April 2018 to March 2019, there were a total of 1,930 requests for review received, with 205 of those requests being upheld.

Case Study: The Victims’ Right to Review (VRR) Process in England and Wales

A recent study has shown mixed results about the effectiveness of the VRR process.[76] On the one hand, meaningful input into the process allowed for greater accountability while also giving victims a sense of control.

- Victim support workers noted that the process had benefits for victims – it gave them a voice, validation, and some control – regardless of the outcome of the case.

- It also gave victims information about the reasons behind why the matter did not proceed, and these explanations provided victims with a sense of closure, regardless of what the final decision was.

- Several problems were also identified, which “reduce[d] victim perceptions of legitimacy in the process, thereby hindering the potentially beneficial role of the reform,”[77] including (a) its limited use, (b) issues of accountability/independence (since the Crown Prosecution Service reviews their own decisions), (c) limited data available on the process, and (d) that limited information was provided to victims about the process.

Survivor rights should not be treated as optional or depend on individual advocacy or geographic region

“There are many issues in remote and northern communities that are not considered when central governments make policy and legislation. There are complicated jurisdictional issues with reserves, limited resources to deliver comparable services, and the voices of northern and Indigenous people are often excluded. Also, many judges deny testimonial aids.”[78]

Many survivors receive excellent supports and services. Those supports are, too often, reliant on grassroots organizations with minimal funding or individual service providers who care deeply about survivor rights and make personal efforts to ensure supports are provided. Survivors told us that those people and those services were lifelines for them.

Those excellent services tend to be person-dependent and not system-based.

- We met with a service provider who had been working for 30 years in a northern community with victims of crime. She is getting ready to retire and is worried there won’t be funding to hire someone to take her place and victims will be left stranded

- Survivors are told, apologetically, that they can’t access testimonial aids, or legal advice or representation, or to protect their private documents - all of which are rights as victims of crime

We are able to guarantee an accused’s constitutional rights, no matter where they live in Canada, rightfully so. We should also be able to guarantee the rights of the person who was harmed no matter where they live.

“For all the new initiatives, victims have gotten far less than promised. Rights have been unenforced or unenforceable, participation sporadic or ill-advised, services precarious and underfunded, victims needs unsatisfied if not further jeopardized, and victimization increased, if not in court then certainly in the streets. Given the outpouring of victim attention in recent years, how could this happen?” [79]

Like rights for people accused of a crime, victim rights should be firmly entrenched in law, policy and practice.

Case study: Wrongful convictions, factual innocence

In the 1980s, Ivan Henry was convicted of 10 sexual offences with eight victims, named a dangerous offender, and given an indeterminate sentence. The cases from each woman were similar. These women believed that Mr. Henry would be in jail for his lifetime.

In 2006, the case was reviewed by a Special Prosecutor due to alleged misconduct by the Crown Prosecutor.

- The Special Prosecutor determined the Crown purposely did not disclose documents that could have helped Mr. Henry’s case.

- In 2010, BC Court of Appeal ruled that Mr. Henry was wrongfully convicted and acquitted him on each count.[1]

- The media treated the wrongful conviction as factual innocence. The complainants were not given a voice. Even though there was a wrongful conviction, it was still possible that Mr. Henry committed these crimes.

In 2010, Mr. Henry brought a civil action related to his wrongful conviction.

- The Court found that the Crown breached Mr. Henry’s Charter rights under ss. 7 and 11(d). He was awarded over $7.5 million in Charter damages, compensatory and special damages. The Court did not determine whether Mr. Henry was guilty of sexual offences.

The women filed a lawsuit. Five of the victims did not have the chance to participate in the civil cases brought by Mr. Henry after the review in 2006 of his convictions by a Special Prosecutor.

- The civil lawsuit brought forward by the victims sought to prove that, on a balance of probabilities, Mr. Henry was the one who sexually assaulted them.

- The burden of proof in criminal cases is beyond a reasonable doubt, which is high. Civil cases rely on a different standard, a balance of probabilities, requiring plaintiffs to show that it is more likely than not that the alleged behaviour happened.

Conclusion: The judge found that on a balance of probabilities, Mr. Henry was the person who sexually assaulted each plaintiff. Each plaintiff was awarded $375,000 for general and aggravated damages. An appeal was dismissed by the BC Court of Appeal.

Broader implications

Given the recent adoption of C-40 Miscarriage of Justice Review Commission Act, the media and the public must be careful around the messaging between wrongful convictions and factual innocence.

Karen Bellehumeur, Systemic Discrimination Against Female Sexual Violence Victims, 2023 CanLIIDocs 1244.

The CVBR is a powerful tool that needs to be strengthened and enforced

“It is not unreasonable that victims expect that a government espousing rights for victims will ensure that those rights can be actualized. A false expectation may be worse than no expectation at all.” [80]

We heard from survivors that:

- Survivors continue to fight for their rights to basic information, such as hearing dates.[81]

- Survivors continue to struggle getting publication bans lifted. One survivor shared that the prosecutor in her case told her he was too busy to follow up on lifting the publication ban and that she had to wait. She spent $10,000 to hire a lawyer for the publication ban to be lifted.[82]

- Victims struggle to obtain transcripts of the trials that directly impact them. When they do obtain them, they have to pay for them!

- Victims struggle to get information about plea bargains.

- Victims struggle with the notion that they are sometimes not allowed in the courtroom to observe the hearing that is about them.

- Survivors with intellectual disabilities struggle with accessing rights or knowing what information to request. They may also have difficulty understanding complex legal processes and may find the rapid questioning during interviews or trials overwhelming.[83]

A comprehensive report done in Québec, Rebâtir la confiance, (Rebuilding Confidence), noted that the CVBR speaks in generalities: its wording does not allow victims to know what information they can be given, what their participation in procedures could be, when and how they will be given the opportunity to be heard.

Report Rebâtir la confiance, Québec, 2021.

The CVBR is more powerful than is often recognized

CVBR has quasi-constitutional status.[84] It was a significant advancement for victims and survivors of crime in Canada, marking a culture change in Canada’s legal framework.

- The broad range of rights it endows, along with its primacy over other legislation, gives it the potential for considerable impact.

- Consistently applied, it would provide victims with a stronger voice in the CJS, better access to information, increased attention to their safety, and enhanced opportunities for restitution.[85]

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights (JUST) conducted a study, resulting in the December 2022 report: Improving Support for Victims of Crime. This report reflected input from victims, survivors, advocates, and experts, and showed strong all-party support to improving how victims are treated within the justice system.

Information needs to be provided proactively.

We received a lot of feedback about the CVBR’s lack of proactive information rights and limited enforceability in our investigation. We heard that victims’ needs for information are not being met.[86]

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

We believe that it is problematic to put the onus on the victim to request information about their rights[87]

“Victims don’t know what they don’t know – ‘on request’ in the CVBR is ridiculous.” [88] “This is an obstacle in CVBR rights – makes the bill almost pointless.” [89]

“Victims should be read their rights, similar to how an accused is read their rights.”[90]

In general, we heard that victims and other stakeholders, including some prosecutors, do not have a good understanding of victim rights under the CVBR.[91]

- We often heard the criticism that victim rights are not enforced or enforceable[92] under the CVBR.

- One legal advocacy group pointed out that there is gender disparity when the (male) accused in sexual violence allegations is read their rights and automatically provided with legal counsel while the (female) complainant is provided with no information and no representation about asserting and protecting their rights.[93]

Victims need to be made aware of their rights in plain language.[94]

- One victim described finding out about the CVBR themselves, after 8 years of following up on inaction in response to their own case.[95]

Stakeholders told us that they sometimes struggled with wanting to provide victims with their rights but not having time or other resources. We heard that the CVBR needs funding to be realized.[96]

- Some prosecutors explained that they wished they could meet with survivors earlier in the prosecution process, to fully explain the criminal justice process and their rights under the CVBR.

- One prosecutor stated that they wish they had “More time to meet and prepare them for trial. My heavy workload makes it extremely difficult to meet with survivors more than once to prepare them for trial.” [97] Another stated, “At best, I might have time for a phone call after the first court appearance, and then nothing until 1-6 months before trial.” [98]

The CVBR can help with systemic barriers

The Ontario Native Women’s Association in their written submission to our Office, noted some CVBR limitations.

- It does not include the right to be treated with dignity, compassion and respect by criminal justice personnel and it does not mandate the provision of trauma-informed or culturally competent services or behaviour by criminal justice personnel.

- Systemic racism within the justice system, lengthy legal processes, and re-traumatization from disclosure and testimony frequently discourages Indigenous Survivors from reporting violence or participating in legal processes. There is a need for reforms to the CVBR to require responsive approaches from the justice system that attend to the unique lived experiences of Indigenous Survivors.[99]

Validating Survivor Choice and Agency

Victim rights have recently been strengthened in relation to publication bans.

- Survivor choice is now central. Judges must ask whether a victim wishes to be subject to the order; prosecutors must advise victims of the order, ask whether they wish to be the subject of the order and advise them of their right to modify or lift a ban.

- Survivors can speak freely. They may share their own identity with trusted individuals without breaching the order.

- Easier to lift a ban. Survivors can now apply to revoke the ban without a mandatory hearing unless others’ privacy rights are implicated.

- 96% of stakeholders from our survey (n = 347) agreed that survivors should automatically receive clear accessible information about publication bans and how to remove them.

Bottom line

Bill S-12 marks a necessary shift toward survivor agency. Implementation of these changes – such as proactive information to survivors – will be key.

Federal accountability for the CVBR can be strengthened

“Of all the highlighted flaws regarding Canadian policy omissions, the most flagrant is the complete unenforceability of victims’ rights legislation in Canada. The issue was raised and determined in Vanscoy v. Ontario. In that case, the claimants had not been provided with informational rights contained in the Ontario Victims’ Bill of Rights. The Court dismissed the claim, ruling that no remedy was available under the Bill. The Court interpreted the Bill to contain only a “statement of principle and social policy beguilingly clothed in the language of legislation …”. Consequently, the decision has been applied across the country and victims’ rights bills across Canada are now considered to be legally unenforceable, containing only principles of good practice that are recommendations but not mandatory.”[100]

The Department of Justice Act requires the federal Minister to examine all legislation for inconsistency with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and table in Parliament a statement of the potential effects of the Bill on the rights and freedoms set out in the Charter.

- Justice Canada indicates that “Charter Statements”

- ensure the rights and freedoms of Canadians are respected and considered throughout the law-making process

- identify potential effects that a bill may have on rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- explain considerations that support the constitutionality of a proposed bill

- increase awareness and understanding of the Charter[101]

- We believe that victims’ rights under the CVBR deserve no less attention.

Our scan of the Charter statements from the 45th and 44th Parliaments shows that

- The Charter statements include the benefits to victims of some legislation

- The statements rarely mention the Charter rights of victims

- The statements do not show where legislation will enhance the Charter rights of victims of crime.

In our view, since it was the intention of the federal government to bestow quasi-constitutional status on the CVBR, the Department of Justice should be examining all criminal and correctional legislation for compliance with the CVBR and victims’ Charter rights.

- Respect for Charter rights of victims throughout the criminal justice process does not undermine the Charter rights of accused. If there are conflicting rights, there must be a balancing exercise - as in all situations where there are competing Charter

Why should changes be made?

In our conversations with decision-makers, policy experts and government lawyers, their commitment to doing better for survivors was clear.

- We also know that they are balancing conflicting priorities: shared FPT jurisdiction for the criminal justice system, litigation liabilities for the federal government, stewardship of the criminal law.

- Charter statements which would clearly express a consideration of victims’ Charter rights – and our proposed CVBR Compliance Statements – would allow them to “show their work”.

The CVBR needs a stronger enforcement mechanism

We heard from stakeholders:

“It doesn’t matter how many considerations or words are on paper, if there is no clear process for holding agencies or officials accountable, it ends up just vaporizing.” [102]

Most people (victims, police, crown) do not know about the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR); thus, victims are not being informed of their rights under the CVBR.[103]

“A lot of people enter the court process for the same reasons I did. They are signing up to be hurt, because they know the system is going to hurt them. Willing to take the pain to try and protect the public, but ideally, we shouldn’t have to.” [104]

The seminal Québec report, Rebâtir la confiance, noted that, for victims to complain about a breach of their rights,

“They have to find their way through a maze of procedures that often have the effect of weighing them down, if not discouraging them. Many of them receive no support or guidance. … Lack of knowledge and complexity of the mechanisms in place, cumbersome procedures, lack of follow-up and transparency, a feeling of not having been taken seriously or respected: for the majority of respondents, the experience was disappointing.” [105]

While the CVBR promises certain rights to victims, there is limited enforcement for breaches of these rights.

- Victims cannot go to court to assert or defend their rights

- No oversight body is mandated under the CVBR, although the OFOVC can hear complaints.

- No one can be held accountable for violations

In our view, the CVBR needs to be amended to delete the provisions which remove standing, a cause of action, appeals and judicial review for victims and replace those provisions with a positive duty on criminal justice actors to implement victims’ rights and a remedy if those rights are not respected.

Enforcement must be meaningful

The CVBR has quasi-constitutional status but it is often treated as optional or symbolic.

- Because the remedy for victims is a complaint mechanism to the same agency that conducted the alleged violation, few complaints are made, and fewer are made public.

The Department of Justice received 36 CVBR complaints and 290 enquiries during 2023-2024.[106]

- One of these complaints was under the Department’s CVBR responsibilities around right to information but a review found no infringement of the person’s right.

- The rest of the complaints and enquiries did not go further and over half of these complaints and enquiries were provincial jurisdiction related to administration of justice.

Public Safety Canada released a report, Public Safety Canada Portfolio Report: Victim Complaint Resolution Mechanisms, Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, for the fiscal year 2021-2022.

- For the entire Public Safety portfolio, there were 30 complaints between April 2021 – March 2022 in one year.[107]

| PS Dept. or Agency | Admissible | Inadmissible[108] | Total Received |

|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CSC | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| PBC | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| CBSA | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RCMP | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| Grand Total | 22 | 8 | 30 |

- In the 10 years since the CVBR came into force, there is little jurisprudence to guide its interpretation.

- In 10 years since it was brought into force, there are 102 reported cases. Most of these cases mention the CVBR without analysis.

- In a common law system, which uses litigation and judicial decisions to bring increased understanding to statutes, this is a worrying sign.

In Canada, other quasi-constitutional laws are backed by enforcement mechanisms and oversight bodies. The CVBR stands out as an exception.

| Law | Enforceable | How | Provides remedies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Victims Bill of Rights | ❓ | Limited enforcement through weak complaints process | ❓ |

| Canadian Human Rights Act | ✅ | Enforced by Canadian Human Rights Commission and Tribunal | ✅ |

| Privacy Act | ✅ | Enforced by Privacy Commissioner and courts | ✅ |

| Access to Information Act | ✅ | Enforced by Access to Information Commissioner and courts | ✅ |

| Official Languages Act | ✅ | Enforced by Commissioner of Official Languages and courts | ✅ |

| Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act | ✅ | Enforced by Privacy Commissioner and courts | ✅ |

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve enforceable rights and legal representation

They should be empowered to participate safely, confidently, and meaningfully in the justice system

Endnotes

[1] Karen Bellehumeur, Systemic Discrimination Against Female Sexual Violence Victims, 2023 CanLIIDocs 1244.

[2] Law Society of Ontario. (2024). Independent legal advice and independent legal representation - Lawyer | Law Society of Ontario.

[3] Law Society of Ontario. (2024). Independent legal advice and independent legal representation.

[4] Justice Canada, Fact sheets

[5] Justice Canada, Victims Rights in Canada

[6] Justice Canada, Making a complaint about infringement or denial of a victim’s right

[7] OFOVC. (2024). An Open Letter to the Government of Canada: It’s time for victims and survivors of crime to have enforceable rights.

[8] OFOVC. (2020). Progress Report: The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights.

[9] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #192

[10] SISSA Written Submission #45

[11] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #439

[12] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown; SISSA Survivor Interview #18; SISSA Survivor Interview #26

[13] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #192

[14] SISSA Survivor Interview #4; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #274

[15] SISSA Consultation Table #33: Independent Sexual Assault Centre North

[16] Quoting Dr. Peter Jaffe, in Shutt, S. (2015, February 2). Vicarious trauma: the cumulative effects of caring. Canadian Lawyer. “the empathy that is so critical to working with traumatized people also increases the likelihood of vicarious traumatization”. The same article states, “Ironically, it is the fierce desire to help that can make lawyers helpless.”

[17] Centre international de criminologie comparée. (2025, May). The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights: Where Are We Ten Years Later? Conference, Montréal, Canada.

[18] Ontario began a program of ILR in 2016. Federal funding was used to create pilot projects in Nova Scotia (2017), Newfoundland and Labrador (2017), Saskatchewan (2018), Alberta (2018).

[19] Department of Justice Canada. (2023). Evaluation of the justice partnership and innovation program..

[20] The Justice Partnership and Innovation Program provides contribution funding for projects that support a fair, relevant and accessible Canadian justice system. JPIP supports activities that respond effectively to the changing conditions affecting Canadian justice policy. Priorities include access to justice, family violence, and emerging justice issues. Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2023, September 19). Justice Partnership and Innovation Program.

[21] The Victims Fund provides grants and contributions to support projects and activities that encourage the development of new approaches, promote access to justice, improve the capacity of service providers, foster the establishment of referral networks, and/or increase awareness of services available to victims of crime and their families. Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2024c, July 31). Victims Fund.

[22] McDonald, S. (2024). Accessing justice for victims and survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence. Victims of Crime Research Digest, No. 17. Department of Justice Canada.

[23] The projects had to have been running for 18 months or longer in September 2023.

[24] McDonald, S. (2024). Accessing justice for victims and survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence. Victims of Crime Research Digest, No. 17. Department of Justice Canada.

[25] Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General. (2025). Independent legal advice for survivors of sexual assault.

[26] About YWF - your way forward. (2024, July 18). Your Way Forward.

[27] SISSA Survivor Interview #02

[28] SISSA Survivor Interview #176

[29] Sexual Violence New Brunswick . Services - Sexual Violence New Brunswick

[30] SISSA Consultation Table #21: Independent SAC Maritimes; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #361

[31] SISSA Consultation Table #21: Independent SAC Maritimes

[32] The Journey Project. (2025, March 7). About the Journey Project - The Journey Project.

[33] SISSA Consultation Table #16: Crown ; Consultation Table #21: Independent SAC Maritimes

[34] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #30

[35] SISSA Consultation Table #4: Independent Sexual Assault Centres Ontario

[36] SISSA Survivor Interview #7

[37] SISSA Consultation Table #13: Legal & Independent Legal Advice

[38] SISSA Survivor Interview #113; Consultation Table #28: Women's NGO/Advocacy Organizations

[39] SISSA Survivor Interview #113

[40] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #34

[41] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #225

[42] SISSA Consultation Table #13: Legal & Independent Legal Advice

[43] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #9; SISSA Stakeholder Interview #10

[44] Barbra Schlifer Clinic. (2025, June 9). Independent Legal Advice for Survivors of Sexual Assault Voucher Program: Roster Lawyers.

[45] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #27

[46] Justice for Children and Youth – JFCY – protecting the legal rights and dignity of children and youth. (n.d.). Justice for Children and Youth.

[47] SISSA Written Submission #45

[48] SISSA Survivor Interview #106; SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #998

[49] Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2024). Annual Report 2023-24.

[50] Independent Legal Advice (ILA) Vouchers in Ontario cover $158 in legal fees per hour to a maximum of 4 hours for $632 per survivor.

[51] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #65

[52] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #30, #33

[53] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #50

[54] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #47; SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #130

[55] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #156

[56] Stakeholder Survey, Response #187

[57] Stakeholder Survey, Response #42

[58] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth

[59] SISSA Consultation Table #05: Children and Youth

[60] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #053

[61] SISSA Consultation Table #05: Children and Youth

[62] Elmia M. H., Daignault, I. V., & Hébert, M. (2018). Child sexual abuse victims as witnesses: The influence of testifying on their recovery. Child Abuse and Neglect, 86, 22-32.

[63] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth

[64] SISSA Consultation Table #05: Children and Youth

[65] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth

[66] SISSA Consultation Table #03: Children and Youth; SISSA Consultation Table #05: Children and Youth

[67] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #386

[68] Angela Campbell, A Specialized Sexual Offences Court for Quebec, 2020 CanLIIDocs 1997.

[69] Angela Campbell, A Specialized Sexual Offences Court for Quebec, 2020 CanLIIDocs 1997.

[70] Allison, S. & Boyer, T. (2019). Evaluation of the sexual violence court pilot. NZ Ministry of Justice.

[71] Rape Crisis Scotland. (2023). Specialist Sexual Offences Court.

[72] Independent Systemic Review: The British Columbia Legal System’s Treatment of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence. Final Report. 2025. Recommendations 18A and 18B.

[73] Victims’ Right to Review scheme | The Crown Prosecution Service. (2020, December 16). Crown Prosecution Service UK.

[74] Victims’ Right to Review scheme | The Crown Prosecution Service. (2020, December 16). Crown Prosecution Service UK.

[75] Alan N Young and Kanchan Dhanjal. (2021). Victims’ Rights in Canada in the 21st Century. Department of Justice Canada.

[76] Iliadis, M., & Flynn, A. (2017). Providing a check on prosecutorial decision-making. The British Journal of Criminology, 58(3), 550–568.

[77] Iliadis, M., & Flynn, A. (2017). Providing a check on prosecutorial decision-making. The British Journal of Criminology, 58(3), 552.

[78] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #008

[79] Elias, R. (1993). Victims still: The political manipulation of crime victims. SAGE Publications, Inc., 45.

[80] Karen Bellehumeur, Systemic Discrimination Against Female Sexual Violence Victims, 2023 CanLIIDocs 1244.

[81] SISSA Consultation Table #23: Academics.

[82] SISSA Survivor Interview #197

[83] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[84] Young, A. N., & Dhanjal, K. (2021). Victims’ rights in Canada in the 21st century: Part II: participatory rights. Department of Justice; R. c. Pryczek 2024 QCCQ 7445; R. c. Mund 2024 QCCQ 5149

[85] Young, A. N., & Dhanjal, K. (2021). Victims’ rights in Canada in the 21st century: Part II: participatory rights. Department of Justice.

[86] SISSA Survivor Interview #25; SISSA Consultation Table #19: Human Trafficking QC

[87] SISSA Survivor Interview #25

[88] SISSA Survivor Interview #156

[89] SISSA Survivor Interview #168

[90] SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women's NGO/Advocacy Organizations; Consultation Table #21: Independent Sexual Assault Centers Maritimes

[91] SISSA Consultation Table #23: Academics; Consultation Table #28: Women's NGO/Advocacy Organizations; SISSA Survivor Interview #106

[92] SISSA Consultation Table #31: Victim Services

[93] SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women's NGO/Advocacy Organizations

[94] SISSA Survivor Interview #102

[95] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #94

[96] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #54

[97] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #37

[98] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #54

[99] Annex D, SISSA Written Submission from the Ontario Native Women’s Association

[100] Karen Bellehumeur, “Systemic Discrimination against female sexual violence victims” at p 145

[101] Justice Canada, Charter Statements - Canada's System of Justice.

[102] SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women's NGO/Advocacy Organizations

[103] SISSA Consultation Table #23: Academics

[104] SISSA Survivor interview #004

[105] Report Rebâtir la confiance, Québec, 2021 at p 202, 205. This is our translation. The original French reads « Elles doivent se repérer dans un dédale de procédures qui ont souvent pour effet d’alourdir leur parcours, sinon de les décourager. Bon nombre d’entre elles ne sont pas accompagnées ou guidées dans leurs démarches. … Méconnaissance et complexité des mécanismes en place, lourdeur des démarches à entreprendre, manque de suivi et de transparence, sentiment de ne pas avoir été pris au sérieux ou respecté : pour la majorité des répondants l’expérience s’avère décevante. »

[106] Policy Centre for Victim Issues. (n.d.). Department of Justice’s Canadian Victims Bill of Rights Complaint Mechanism, 2023-2024 Annual Report. Department of Justice.

[107] Public Safety Canada. (n.d.). Public Safety Canada Portfolio Report: Victim Complaint Resolution Mechanisms. Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (fiscal year 2021-2022).

[108] Inadmissible also includes complaints referred to another department or agency.