Restorative and Transformative Justice

“More options for restorative justice, I didn't think that my assaulter would go to jail, nor do I necessarily think he should have… I wanted to make sure that he knew what he had done was not okay and that he would not repeat his actions. I also wanted my experience to be known in case it happened to somebody else by him, there would be a record of it being a pattern. Ultimately, I also just wanted some closure. It would've been really helpful for me to know that he was doing therapy, or regretted his actions, or to have an apology from him.” [1]

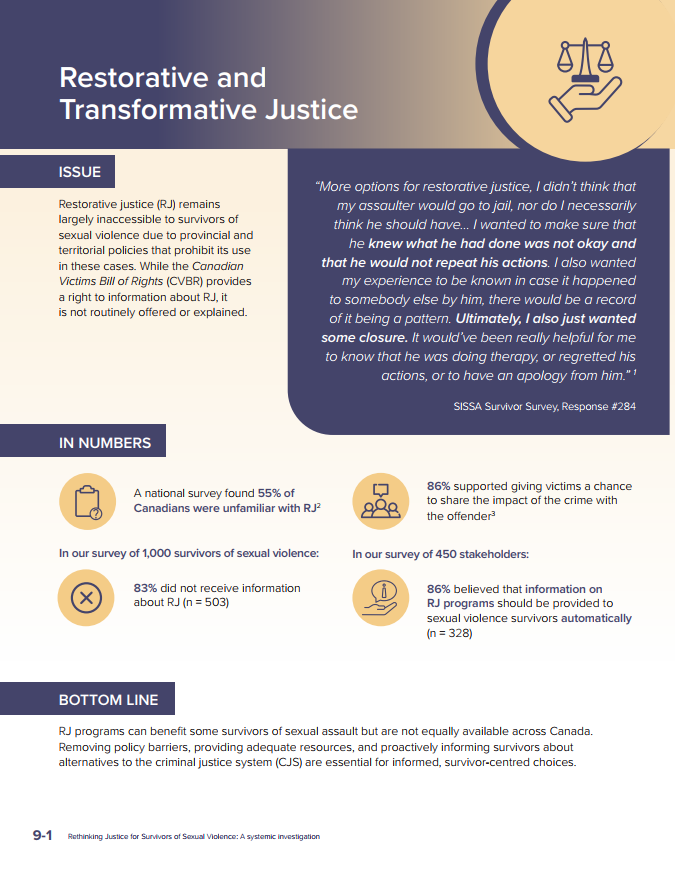

ISSUE

Restorative justice (RJ) remains largely inaccessible to survivors of sexual violence due to provincial and territorial policies that prohibit its use in these cases. While the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) provides a right to information about RJ, it is not routinely offered or explained.

IN NUMBERS

- A national survey found 55% of Canadians were unfamiliar with RJ[2]

- 86% supported giving victims a chance to share the impact of the crime with the offender[3]

In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence:

- 83% did not receive information about RJ (n = 503)

In our survey of 450 stakeholders:

- 86% believed that information on RJ programs should be provided to sexual violence survivors automatically

KEY IDEAS

- RJ can be a consent-driven process promoting accountability to survivors

- Some are concerned that RJ decriminalizes sexual violence

- RJ for sexual violence requires training to address power imbalances

- Policies that do not allow RJ for sexual violence limit survivor choices

- Transformative Justice (TJ) uses community-led practices outside the CJS

- RJ programs are under-resourced, limiting availability and quality

- Survivors are demanding the right to choose

BOTTOM LINE

RJ programs can benefit some survivors of sexual assault but are not equally available across Canada. Removing policy barriers, providing adequate resources, and proactively informing survivors about alternatives to the criminal justice system are essential for informed, survivor-centred choices.

RECOMMENDATIONS

7.1 Review restrictive policies: The federal government should, in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, review policies that prohibit the use of restorative justice models for sexual violence and exchange knowledge on promising practices already used in parts of Canada.

7.2 Expand and stabilize funding for restorative and transformative justice: The federal government should explore joint funding models with provinces and territories to provide adequate and sustained funding to support restorative justice programs and other alternatives to the criminal justice system, such as transformative justice.

7.3 Proactively inform survivors: The federal government should amend the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights to require that victims be automatically informed of available restorative justice programs.

Our investigation

Specific actions

We held three consultation tables discussing alternative, restorative, and transformative justice models. One was a multidisciplinary group comprised of defence lawyers, Crown prosecutors, judges, and community advocates, keen on alternatives to make the process fairer for survivors and accused. We also interviewed survivors who participated in RJ programs and stakeholders working in specialized restorative and transformative justice programs for survivors of sexual violence. We also interviewed academic RJ experts in Canada and internationally. The Ombudsperson attended a national conference on RJ and was able to conduct additional interviews.

People in the field provided us with information about promising practices and emerging alternatives. We had discussions with the Gatehouse, a non-profit organization that provides trauma-informed services and supports to people who have experienced childhood sexual abuse. They are advocates for RJ practices and were instrumental in helping us bring together RJ advocates from across the country to learn from their work and knowledge.

We met with North Shore Restorative Justice Society, a Vancouver-based organization focused on RJ which has Indigenous roots.[4] We also learned about alternatives such as Project 1 in 3 in Sarnia-Lambton, Ontario, a pre-charge diversion program for youth who have engaged in sexual crimes, and who qualify for the program. The program explores topics such as the purpose of diversion, gender norms, consent, emotional regulation, and survivor empathy. Youth must complete all 8 weeks of lessons and write an apology letter to the survivor (delivery pending survivor request) to graduate from the program.[5]

We also met with the Transformative Justice Collective at University of Ottawa and with WomenatthecentrE about their transformative accountability and justice initiative that explores alternative models of justice for survivors of sexual assault.

Background

Restorative Justice is built on mutual consent

RJ is an approach to justice that seeks to repair harm. RJ is a voluntary, consent-based approach, which can allow survivors to participate more safely and on their terms. It models consent, respect, and healthy communication. This process can provide opportunities for those harmed and those who take responsibility for the harm to communicate and address their experiences and needs.[6]

RJ differs significantly from an adversarial, retributive approach to justice:

- Wrongdoers recognize the harm they have done and accept responsibility for their actions.

- Those affected directly by the harm may come forward to share the impact of the harm on their lives.[7]

- A trained facilitator supports the process.

RJ offers many alternative approaches depending on the specific situation. For example, the victim and the person who harmed them are not necessarily required to meet face to face. There are diverse RJ styles.

Many people do not view the CJS as an opportunity for justice to be served. Those who experienced harm from the CJS don’t trust it to offer a just process or just outcomes.

- A leading victim rights organization has said that an overwhelming number of survivors are retraumatized by the criminal justice process.[8]

- RJ can be an alternative to what some view as state abuse and an option to access justice for those who are typically “excluded or discriminated against in the conventional legal system.” [9]

Some of the Principles for Restorative Justice*

- Respect, compassion, and inclusivity.

- Acknowledging and addressing the harm done to people and communities.

- Voluntary participation and informed, ongoing consent (with ability to withdraw).

- Empower and support survivors in making informed choices and ways forward in their lives.

- Safety: Attend to the physical, emotional, cultural, and spiritual safety and well-being of all participants

* Principles and Guidelines for Restorative Justice Practice in Criminal Matters (2018) - CICS

Origins

Many RJ programs draw their theory of change from Indigenous legal traditions, which have been used by Indigenous peoples to resolve disputes for thousands of years.[10] RJ values are consistent with and have been informed by the beliefs and practices of many faith communities and cultural groups in Canada.[11] RJ has been used to some extent in the CJS in Canada for over 40 years.[12]

Varied Approaches[13]

| Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA) | Peacemaking Circles | Healing Lodges | Community-Assisted Hearings | Community Conferencing |

| Healing Circles | Sentencing Circles | Victim-Offender Mediation | Surrogate Victim/Offender Restorative Justice Dialogue |

Community Justice Forums |

RJ is practised differently across Canada.[14] It can be used separately from the system entirely, in addition to pre-charge, post-charge, pre-sentencing or post-sentencing stage of the CJS.[15]

- Referrals may come from police, Crown Attorneys, or victim service workers. In some regions, charges can be withdrawn or stayed if resolved through RJ.

- RJ is used in cases involving young people and adults, first-time offenders, repeat offenders and for crimes ranging from minor to serious.[16]

Why use restorative justice? Why not?

| Potential Benefits | Potential Criticisms |

|---|---|

RJ has shown positive results for some sexual violence cases, such as survivor healing, participation, satisfaction, and empowerment.[17] Some advocates have argued that flexible approaches are better positioned to empower and heal victims because they provide a safe space for them to confront the person who harmed them and allow them to have input into justice outcomes. RJ allows for more survivor consent, like being able to pause, discontinue, have a change of mind about ways of participation, change location, ask their own questions, etc. An RJ approach also allows space for considering the context surrounding the harm, (social economic), as well as addressing trauma and mental health.[18] Advocates for the use of RJ in sexual violence cases have noted the conventional justice system’s shortcomings in meeting the needs of survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence. “Anything is better than that” [19]

|

Sexual violence is a crime of power. There are concerns that people who perpetrated sexual violence harms could manipulate the process, given the power dynamics involved in sexual violence and GBV There are numerous concerns about using RJ for cases of sexual violence, such as safety, the possibility of revictimization, power imbalances, and that RJ is too lenient a response. [20] There is some concern that if RJ is used as a diversion in sexual violence cases, it is counter to the long-standing goal of women’s rights activists to move violence against women from the private to the public sphere and establish it as a public crime. [21]

|

What we heard

“Currently, police are not likely to refer a more serious sexualized violence as a pre-charge referral to RJ. Many sexual assaults go unreported – wouldn't it be better to do something that is along with the victim's wishes than for no report at all to be made?” []

“We see and hear of a need for restorative and transformative justice approaches as options for survivors and as creative responses to survivors’ access to justice needs.” [23]

During our investigation, we heard:

- Some survivors strongly agree that RJ benefits sexual violence cases, while others strongly disagree. This highlights the need for an individualized approach, with a greater range of options available to survivors.

- In some jurisdictions, police downgrade sexual assault charges to enable RJ referrals.[24]

- Crown prosecutors may face disciplinary actions if they go against their Crown policies and refer sexual assault cases to RJ.

- A survivor had found the criminal justice process retraumatizing and looked for an alternative. A Crown referred her to RJ which became a healing and life-changing process for her, but the Crown was reprimanded for her involvement.

We heard several survivors say that the criminal “justice” system:

- Says to survivors that the system is protecting you but violates your consent in many of its processes, like taking your private records, submitting you to painful examinations and humiliating cross-examinations[25]

- Takes the experience of the survivor away from them and doesn’t allow them to decide[26]

- Is a monolithic approach that will never serve the needs of all victims[27]

Survivor survey: A small group of survivors responded to questions about their experiences with restorative justice (n = 18). The number of responses is too low to provide reliable conclusions but still offers some value.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

The lack of awareness of RJ options limits informed choice

“Really interested in restorative justice, tried to ask for that, but RCMP didn't know

and didn't help me to find out.” [28]

“A big barrier to RJ includes the misconceptions. A person can show up enraged. Doesn’t have to be about forgiveness. Also, the idea that it cannot be used for SA [Sexual Assault] or IPV.” [29]

In our survivor survey, we learned about information gaps

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

Under the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, victims have the right to information, upon request, about services available to them, including RJ programs.[30]

- The problem is that a person would have to be aware of the right and service to be able to ask for it.

- The CVBR should be amended to proactively inform survivors of the availability of these programs.

Qualitative interviews with survivors of violent crime in Canada and Belgium reveal that survivors prefer being proactively provided information about RJ rather than having to ask about it.[31] This allows them to make informed decisions and come back to options at a later time.

Survivor Shamed for Wanting Restorative Justice

We heard from one survivor who was retraumatized by the Crown responsible for her case after expressing her desire to proceed with RJ. Although both the perpetrator and defence counsel agreed to RJ, the Crown told her:

“Feminists fought for years for marital rape laws and that justice won’t be served

because she’s not testifying… [The Crown attorney] yelled at me via zoom and said I was not being brave and courageous because I did not want to testify. I wanted to do restorative justice instead, which the defendant and his lawyer agreed to.” [32]

More survivors, criminal justice actors, and the public need to be informed on RJ

In 2024, a national survey found 55% of Canadians were unfamiliar with RJ and 86% supported giving victims a chance to share the impact of the crime with the offender.[33]

One of our consultation tables noted RJ is often viewed as controversial. Stakeholders noted that some criminal justice actors are not aware of RJ and therefore cannot properly inform survivors of this alternative.[34]

Restorative options for child and youth victims

Child and youth advocacy centres (CYACs) are an important place to implement and pilot restorative and transformative justice given the integrated, multidisciplinary environment, trauma-informed child-centred environment. CYACs' principles of trauma-informed justice (i.e., safety, trust, choice, coordination and collaboration, support, and empowerment) demonstrate a readiness for piloting restorative justice practices. Moreover, CYACs are uniquely positioned to facilitate restorative processes that prioritize healing, accountability, and community involvement, in cases involving children and youth. Their existing infrastructure supports safe dialogue, emotional regulation, and long-term support—key components of restorative justice.

“By embedding restorative options within CYACs, we create a more compassionate justice pathway that not only addresses harm but also fosters resilience and repair."

Stakeholder interview 195

In 2023, Public Safety’s National Office for Victims (NOV) held a roundtable with victim stakeholders and non-governmental organizations around victim rights and federal corrections. The roundtable recommended:[35]

- Expanding public legal education and information

- Increasing the availability of training and online resources about RJ.

- Informing victims of their CVBR right to information on RJ.

Restorative Opportunities Program - Correctional Service of Canada

Under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act section 26.1 (1)[36]:

- CSC must provide registered victims with information about its RJ and victim-offender mediation programs.

- CSC may take steps to offer those services upon request.

Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) offers victim-offender mediation through the Restorative Opportunities Program. CSC receives ongoing qualitative feedback from participants.[37] From 1992 to 2024:

- 317 federal offenders participated in face-to-face mediation.

- 28% of those cases included sexual offences.[38]

RJ programs are under-resourced, limiting availability and quality

- “For the amount of money that's spent on policing and jails – to very little effect and zero repair for those harmed – we could easily fund trauma- and violence-informed restorative and transformative justice initiatives. Shoving someone into jail increases the likelihood that they themselves will experience sexual violence at the hands of corrections officers or other inmates. That is neither helpful nor rehabilitative.” [39]

Access to RJ varies across provinces and territories due to inconsistent practices and funding. We learned that

- Nunavut has no RJ option for sexual violence[40]

- Stakeholders felt that decisions to fund RJ often appear to be based on perceptions of its effectiveness and necessity

- Policies that prohibit the use of RJ, such as moratoriums, impact funding for programs that offer RJ

Limited funding impacts the availability of trained facilitators, the timeliness of any available processes, survivors’ access to culturally or trauma-informed models.

- A stakeholder shared that they wish their organization could support anyone who is looking for restorative options, which they could if they had more funding, and suggested a fully funded pilot project to develop best practices for referrals.[41]

Directory of Restorative Justice programs in Canada

The Department of Justice Canada maintains a Directory of Restorative Justice programs, which currently lists 395 RJ programs across Canada.[42] However, these programs operate at different stages of the CJS and vary in scope, funding, and accessibility.[43] There is also currently no search option for RJ programs specifically for cases of sexual assault.

Policies that prohibit the use of RJ, such as moratoriums, prevent any chance for RJ options

“RJ was amazing. A restorative circle. Incredible. It changed my life. So meaningful. Trauma informed, time for emotions, no expectation to be the perfect victim, supportive and humane. All my needs were met. There was community support. My mom was invited to join.” [44]

“Felt empowered, hopeful, and provided a sense of closure, which was such a contrast to the preliminary hearing where she felt blamed, defeated, and exhausted.” [45]

Policies that prohibit the use of RJ for cases of sexual assault

RJ can only be used in sexual assault cases if the Attorney General of a province or territory allows it. Federal, provincial, and territorial governments have significant variance in which cases are appropriate for RJ and how they should be handled.[46]

In some provinces, policies that prohibit the use of RJ, such as moratoriums,[47] prevent RJ in sexual assault cases altogether.

- Feminist organizations advocated for moratoriums, but many believe they were not supposed to be permanent.[48] They were meant to be temporary to provide more time for provinces to adapt and to explore safe RJ practices for survivors of sexual violence.[49]

- Provinces and territories have the jurisdiction to review and remove these policies.

| Full Exclusion of Sexual Assault Cases | Exclude Certain Cases of Sexual Assault | Consider Circumstances | No Prohibition |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Consequences of moratoriums

LEAF explored these barriers in a 2023 report.[50] This comprehensive report notes that consideration must be given to whether these policies should be lifted as they can restrict survivor choice and access to RJ without providing proper information, ultimately impacting access to justice.

- Some view this as a restriction on survivor agency, which goes against trauma-informed practices.

- This restriction can also impact Crown discretion to divert cases as they see fit. Crowns shared frustrations with the RJ policy, which they thought undermined their ability to do their job effectively.[51]

These policies, including moratoriums have slowed training and capacity-building in the RJ/TJ field.

- Some GBV practitioners do not view RJ practitioners as having appropriate experience for these cases.

- RJ service providers can feel diminished when their approaches are viewed as “more lenient and less legitimate.” [52]

Does the use of restorative justice risk decriminalizing sexual violence?

No - Some advocates argue that RJ does not decriminalize sexual violence. Instead, they see RJ as a better way to address the harm caused by these offences. Key points include:

Survivor Choice:

RJ gives survivors the option to choose between the criminal justice system (CJS) and a restorative process.

Distrust in CJS:

Many survivors have lost trust in the legal system’s ability to take violence against women and gender-diverse people seriously.

Healing and Closure:

RJ can provide a sense of healing and closure that the CJS often fails to deliver.

Alignment with Survivor Wishes:

Some view RJ as reflecting survivors’ needs as part of broader transformative justice approaches. .[53]

Yes - Other advocates believe RJ could undermine accountability and risks shifting gender-based violence (GBV) back into the private sphere. [54] Key concerns include:

Historical Context:

Feminist movements in the 1970s fought for GBV to be treated similarly to other crimes by the state; RJ may be seen as reversing this progress.

Minimization of Harm:

Some anti-violence advocates argue that sexual violence is already minimized by the CJS and fear RJ could worsen this.[55]

Safety Risks:

Unequal power dynamics in GBV cases may make RJ unsafe for survivors. [56]

Decriminalization Concerns:

Critics worry that expanding RJ could lead to the perception, or reality, of decriminalizing sexual violence.

Survivors want the perpetrator to take accountability

“It was not my fault. [The perpetrator] was wrong. And yet his actions made sense. Two things can be true at the same time. The criminal justice system doesn’t allow for two truths to be held at the same time… I knew none of [the RJ practices] would be remotely possible through the criminal justice system. It’s not just a broken system it’s the wrong system. It doesn’t need reformation, it needs replacement.” [57]

Survivors are not always interested in the perpetrator receiving jail time

“In my experience survivors say they want the perpetrator to acknowledge the harm done and take responsibility for their actions. Even with a guilty verdict this may not happen.” [58]

Many view jail as ineffective or not rehabilitative but still want the person who harmed them to take accountability. For some, RJ offers the only path to healing and closure, especially when they have unanswered questions about the offence.[59]

Restitution is a common outcome for RJ

Restitution agreed to during an RJ process is more likely to be paid to the victim than standalone restitution orders issued by a Court.[60]

In fall 2021, OFOVC released a special report, Repairing the Harm: A Special Report on Restitution for Victims of Crime, that discussed restitution, the rights and barriers to accessing support, as well as RJ approaches in which reparations can include restitution. It recommended an increase in the use of RJ programs and that the Minister of Justice launch a public awareness campaign on victim rights to restitution.

RJ can better support the needs of a diverse population in a respectful and healing manner

“I would like to see an explicit path and evidentiary protections for restorative and Indigenous justice options. Remove all doubt that statements by the victim and the accused made in these contexts cannot be used in subsequent criminal proceedings. This could allow for referral of more serious cases if the threat of prosecution could be more effectively maintained.” [61]

Restorative Justice in Indigenous Contexts

We heard the following from Indigenous participants and those working with Indigenous communities:

- RJ can support healing.

- Sexual violence must be approached holistically, with support for both offenders and the community.[62]

- Alternative models must be funded and supported through Indigenous communities to respect the survivor and community needs,[63] as some Indigenous Justice programs are not transferable to a western context.[64]

Pilot Project in Alberta

Justice Beverley Browne was a member of the Queen’s Bench of Alberta and founded the Restorative Justice Committee, also known as Wîyasôw Iskweêw, conveying the meaning of “Woman standing with the law.”[65]

The Committee assesses referral guidelines and can refer appropriate cases in court to restorative justice programs. This committee is comprised of justices from the Court of Queen’s bench and Provincial Court, Crown prosecutors, defence lawyers, Indigenous organizations, victims’ rights organizations, RJ practitioners, police, and other stakeholders.

This pilot project allows all matters coming before criminal courts to be considered (the project hopes to expand to family and civil matters) but specifically matters already before the court (post charge – pre-sentencing).[66]

Figure. Alberta Restorative Justice Pilot Project Timeline of Legal System

versus Court-annexed restorative justice process[67]

Resistance to RJ. We also recognize that RJ is not practised in some Indigenous cultures and there is resistance to having it colonially imposed on Indigenous communities. There are also various views about RJ, for example some Indigenous stakeholders emphasized the cultural value of conversation over a meal instead of a facilitated process.

MMIWG Calls for Justice[68]

MMIWG Calls for Justice include specific recommendations around Indigenous Courts and the use, access to and outcomes of Gladue reports.

“5.11 We call upon all governments to increase accessibility to meaningful and culturally appropriate justice practices by expanding restorative justice programs and Indigenous Peoples’ courts.”

The 2025 Department of Justice Federal Indigenous Justice Strategy[69] discusses the importance of considering individual needs and providing tailored support.

Transformative Justice (TJ) uses community practices outside the criminal justice system

“The Transformative Justice model developed as a grassroots movement by Black people, especially Black women, queer, trans and disabled communities, as well as activist communities, to operate outside of the criminal legal system, because their communities were often the victims of state-sanctioned, as well as inter-personal violence. Therefore, the idea of going to that system expecting justice was antithetical to the system's own ideas of who deserved justice.” [70]

Transformative Justice (TJ) adopts a broader set of strategies than RJ but still uses RJ and restorative practices. Because TJ places an emphasis on structural factors, interventions can include education, advocacy, training, and other actions to counter oppression.[71]

We heard that transformative justice

- recognizes that the systems in place are not keeping survivors safe and cause further harm[72]

- gives more consideration to the influence of structural factors like oppression, marginalization, and privilege, and asks, “Why do we live in a culture where sexual violence happens?” [73]

- aligns with Black, trans, and abolitionist feminism views of the legal and carceral system

- aims to foster accountability outside the criminal “legal” system[74]

Essential Reading: Declarations of Truth[75]

In Declarations of Truth, WomenatthecentrE proposes a model of transformative justice that is responsive to the concerns and unmet needs of survivors.

- WomenatthecentrE is a Canadian incorporated organization created by survivors for survivors, with membership around the world.[76]

- Their research affirmed that “the legal system does not equate to justice or accountability for those who have caused harm, nor does it equate to justice and safety for survivors.” [77]

This three-year project, funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE), focused on finding an alternative model of justice for sexual violence survivors. WomenatthecentrE identified three fundamental principles of justice that need to be embodied in effective responses to sexual violence:

- Aggressor accountability, remorse, and change in attitude and behaviour, having recognized the harm caused by their actions.

- Survivors feel heard, believed, and validated.

- Societal acknowledgement of the role it plays in navigating and negotiating these elements.

Case study – Transformative and restorative justice

“Why would I report someone who did something homophobic to a homophobic system?

For me justice looked like…try to prevent this from happening again to someone out there. It looked like forgiving him while still acknowledging he was wrong.

A restorative justice process could have helped with this. We could have been in circle, and he could have apologized…could have been provided therapy. That would have been even better justice, and it wouldn’t have been put on me to do the work myself… There is a growing population who know retributive justice is not justice and we aren’t seen or served by the existing systems.” [78]

Survivors are demanding a right to choose

Open letter. In June 2025, Survivors 4 Justice Reform, founded by Marlee Liss, published an open letter calling on the Ontario Attorney General to reform Crown Policy D4, which deems sexual violence cases ineligible for community justice programs.[79] They are urging that the Ontario policy be revised to allow survivors of sexual violence to access RJ options when they choose to pursue this path. The letter has over 50 signatures from individuals and organizations in the field.

- Marlee Liss did an interview with CBC News on restorative justice in the context of sexual violence and the limitations of the criminal justice system.[80] She highlights barriers including lack of awareness, lack of funding, and Crown policies banning referrals to RJ process, as well as underscoring the need for informed consent for survivors.

News article[81]. In June 2025, the Executive Directors of the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic and LEAF co-released an opinion piece, “The criminal Justice system keeps failing sexual-assault survivors. There has to be a better way,” about the criminal trial of five hockey players.[82] RJ is highlighted as an alternative that, with increased public interest, could be a beneficial option for survivors of sexual violence. They call for lifting Crown restrictions, further exploration and expansion of these programs, and increased investment to provide survivors with alternatives.

Film: The Meeting[83] [1h 36m]

The film is based on a real meeting that took place in Ireland between Ailbhe Griffith and the man who, nine years earlier, subjected her to a horrific sexual assault that left her seriously injured and fearing for her life.

Griffith, in an extraordinary move, chose to play herself in this unique drama about RJ.

Webinar: Transformative Accountability & Justice Initiative

WomenatthecentrE has a three-part webinar series[84] that provides further context and detail on transformative justice in Canada. The webinar also profiles Salal Sexual Violence Support Centre’s Transformative Justice Pilot Project.[85]

Recommendations from stakeholders

According to the Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF) 2023 report, Crowns shared frustrations with the RJ policy, which they thought undermined their ability to do their job effectively. LEAF recommends that the Office of the Attorney General re-evaluate moratoriums in each province and territory that impact RJ use in sexual violence cases. Anti-violence advocates and RJ experts must be consulted, and collaboration must continue with the goal of providing options to survivors.[86]

In Dr. Kim Stanton’s (2025) final report on the Independent Systemic Review: The British Columbia Legal System’s Treatment of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence,[87] recommendation 21 calls for the Ministry of Attorney General to create a BC working group to examine RJ processes for sexual violence and IPV cases. Dr. Stanton writes:

“If managed carefully and with appropriate safeguards in place, restorative processes have the potential to respond more comprehensively to the needs of both survivors and perpetrators. Restorative processes, if adequately funded and with feminist anti-violence experts involved, may provide survivors with greater control over their pursuit of justice and offer supports to perpetrators in their healing, growth and efforts to make amends.”

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve real choices, and respect,

for the justice paths they choose.

Restorative and community-led models can be more responsive to survivors’ needs.

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #284, emphasis added

[2] Evans, J. (2024). Public Perceptions of Restorative Justice in Canada. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice.

[3] Duff, J. (2024). Perceptions of and confidence in Canada’s criminal and civil justice systems. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice.

[4] Society, N. S. R. J. (n.d.). North Shore Restorative Justice Society. North Shore Restorative Justice Society.

[5] Sarnia-Lambton, Rebound Program in partnership with The Centre and Interval House Sarnia-Lambton Rebound - a caring partner in the successful development of youth.

[6] Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative practice in criminal matters.

[7] The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime (CRCVC). (2022). Restorative justice in Canada: what victims should know.

[8] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence. Smith, D. The Canadian Bar Association. (2023). Survivors need better avenues to justice.

[9] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[10] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[11] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[12] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[13] The Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime (CRCVC). (2022). Restorative justice in Canada: what victims should know. 6-9.

[14] Department of Justice Canada. (2021). Restorative justice.

[15] Bourgon, N. & Coady, K. (2019). Restorative justice and sexual violence: an annotated bibliography. Department of Justice Canada.

[16] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[17] Bourgon, N. & Coady, K. (2019). Restorative justice and sexual violence: an annotated bibliography. Department of Justice Canada.

[18] Jeffries, S., Wood, W. R. & T. Russell. (2021). Adult restorative justice and gendered violence: practitioner and service provider viewpoints from Queensland, Australia. Laws,10(1): 13.

[19] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #194.

[20] Bourgon, N. & K. Coady. (2019). Restorative justice and sexual violence: an annotated bibliography. Department of Justice Canada.

[21] European Forum for Restorative Justice. (2020). Restorative justice and sexual violence.

[22] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #392

[23] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #34

[24] Weingarten, N. & MacMillan, S. (2025). Sexual assault survivors calling on Ontario to lift policy that limits access to community justice programs. CBC News.

[25] SISSA Consultation Table #34: Transformative Justice

[26] SISSA Focus Group #5: Transformative Justice

[27] Consultation Table #34: Transformative Justice

[28] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #436

[29] SISSA Survivor Interview #94

[30] Canadian Victims Bill of Rights, SC 2015, c 13, s 2.

[31] 2016; Wemmers and Van Camp 2011 as cited in Wemmers, J. (2021). Judging victims: Restorative choices for victims of sexual violence. Victims of Crime Research Digest No.10.

[32] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #312

[33] Duff, J. (2024). Perceptions of and confidence in Canada’s criminal and civil justice systems. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice.

[34] SISSA Consultation Table #3: Child and Youth

[35] Public Safety Canada (2025). 2022-2023: National Victims Roundtable on the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights.

[36] Government of Canada (2025). Corrections and Conditional Release Act

[37] Not systematically collected by CSC due to participants’ needs for confidentiality and the personal nature of the experiences.

[38] Correctional Services Canada. (2025). Restorative opportunities victim-offender mediation services correctional results report 2022 to 2023 and 2023 to 2024.

[39] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #883

[40] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #53: Nunavut Sexual Violence Prosecutor

[41] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #229

[42] Department of Justice Canada. (n.d.). Search the directory of restorative justice.

[43] Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (CICS). (2018). Principles and guidelines for restorative justice practice in criminal matters.

[44] SISSA Survivor Interview #94

[45] SISSA Survivor Interview #94

[46] Tomporowski, B., Buck, M, Bargen, C. and V. Binder. (2011). Reflections on the past, present and future of restorative justice in Canada.

[47] A moratorium is a hold. It puts a hold on cases of sexual assault being referred to RJ programs. Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[48] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[49] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[50] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[51] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[52] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[53] Survivors 4 Justice reform. (n.d.). Survivors 4 Justice Reform.

[54] Bourgon, N. & Coady, K. (2019). Restorative justice and sexual violence: an annotated bibliography. Department of Justice Canada.

[55] Bourgon, N. & Coady, K. (2019). Restorative justice and sexual violence: an annotated bibliography. Department of Justice Canada.

[56] Goodmark, L. (2018). Restorative justice as feminist practice. The International Journal of Restorative Justice. 1. 372-384.; Canadian Association of Sexual Assault Centres. (n.d.) Aboriginal Women’s Action Network Restorative Justice Policy (AWAN). (n.d.).

[57] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #938

[58] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #309

[59] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #498

[60] Latimer, J., Dowden, C., & Music, D. (2022). The effectiveness of restorative justice practices: A meta-analysis. Department of Justice Canada.

[61] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #187

[62] SISSA Consultation Table #10: Indigenous Communities

[63] SISSA Written Submission #28

[64] SISSA Written Submission #33

[65] Crescott. (n.d.). Beverley Brown. RJ Pilot.

[66] Restorative Justice Pilot Project. (n.d.). The pilot: A collective approach.

[67] Restorative Justice Pilot Project. (n.d.). Scope of the pilot project.

[68] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

[69] Department of Justice Canada. (2025). Indigenous Justice Strategy.

[70] WomenatthecentrE. (2020). Declarations of truth: Documenting insights from survivors of sexual assault. Women and Gender Equality Canada. 15.

[71] SISSA Focus Group #5: Transformative Justice

[72] SISSA Focus Group #5: Transformative Justice

[73] SISSA Focus Group #5: Transformative Justice

[74] Baird, E. (2023). Transformative justice responses to gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, and sexual violence. University of British Columbia.

[75] WomenatthecentrE. (2020). Declarations of Truth. Funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE).

[76] WomenatthecentrE. (n.d.). About us.

[77] WomenatthecentrE. (n.d.). Transformative accountability & justice: About.

[78] Survivor Survey, Response #938

[79] Letter — Survivors 4 Justice Reform. (June 9, 2025). Survivors 4 Justice Reform.

[80] CBC News: The National. (2025). Restorative justice offers path to personal reclamation, advocate says [YouTube].

[81] Campbell, R. (2025). Survivors of sexual assault fight for access to restorative justice programs. City News.

[82] Mattoo, D. & Hrick, P. (2025). The criminal justice system keeps failing sexual-assault survivors. There has to be a better way. The Globe and Mail.

[83] Gilsenan, A. (2018). The Meeting. Parzival. https://themeetingfilm.com/

[84] WomenatthecentrE. (2022). Leading with abundance: Transformative justice as a framework for change.

[85] At the time of the webinar, Salal went by the name WAVAW.

[86] Burnett, T., & Gray, M. LEAF. (2023) Avenues to justice: Restorative & transformative justice for sexual violence.

[87] Stanton, K. (2025). The British Columbia legal system’s treatment of intimate partner violence and sexual violence. Government of British Columbia. 157.