Access to Services

“Survivors of assault need better access to resources, legal support, counselling, and advocacy. These services should be easily accessible, confidential, and trauma-informed, helping survivors feel empowered to make decisions in their own time and space.” [1]

ISSUE

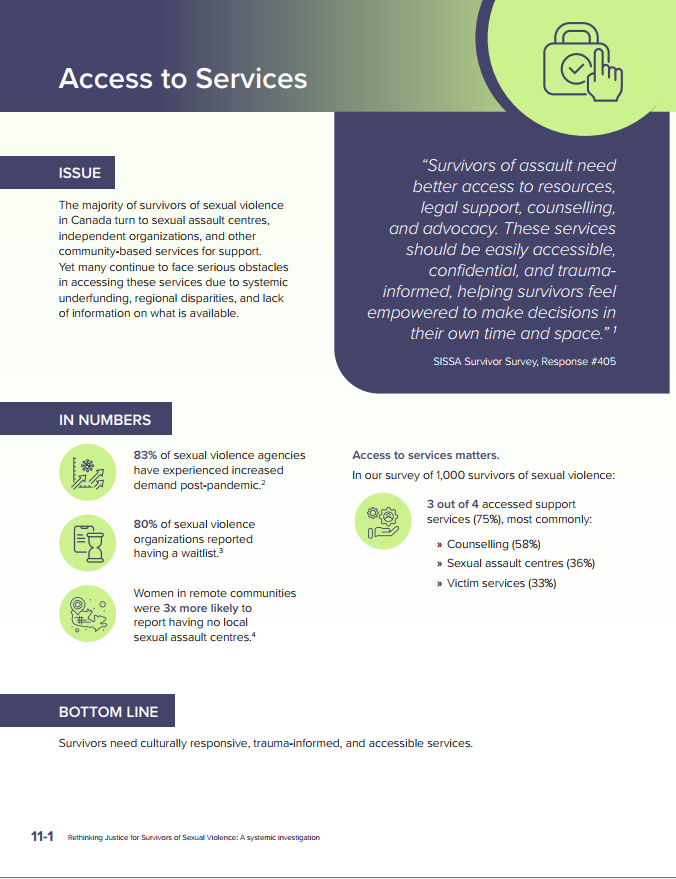

The majority of survivors of sexual violence in Canada turn to sexual assault centres, independent organizations, and other community-based services for support. Yet many continue to face serious obstacles in accessing these services due to systemic underfunding, regional disparities, and lack of information on what is available.

IN NUMBERS

- 83% of sexual violence agencies have experienced increased demand post-pandemic.[2]

- 80% of sexual violence organizations reported having a waitlist.[3]

- Women in remote communities were 3x more likely to report having no local sexual assault centres.[4]

- Access to services matters. In our survey of 1,000 survivors of sexual violence: 3 out of 4 accessed support services (75%), most commonly:

- Counselling (58%).

- Sexual assault centres (36%).

- Victim services (33%).

KEY IDEAS

- Canada lacks national data on access to services and unmet needs

- Barriers to accessing services persist, particularly for underserved communities

- The gender-based violence (GBV) workforce in Canada is under-resourced and overburdened

- Survivors and stakeholders expressed support for integrated, community-based models and wraparound services for victims of sexual violence

BOTTOM LINE

Survivors need culturally responsive, trauma-informed, and accessible services.

RECOMMENDATIONS

9.1 Guarantee a right to assistance. The federal government should amend the Canadian Victims Bill of Rights to add a “right to assistance.”

9.2 Provide independent survivor advocate: The federal government should provide sustained operating funding to sexual assault centres to support access to independent, community-based survivor advocates. It should also fund Indigenous-led survivor advocate programs that reflect the needs of Indigenous communities.

9.3 Sustain Child and Youth Advocacy Centres: The federal government should establish funding partnerships with the provincial and territorial governments, to ensure that Child and Youth Advocacy Centres (CYACs) are available in every region in Canada.

Background

Understanding the Victim Services Landscape

Throughout this chapter we refer to different types of supports and services available to survivors of sexual violence. The following typology describes the main models of victim service delivery across Canada:

System-based victim services

Delivered by provincial and territorial governments, these services support victims throughout the criminal justice system. This may include, but is not limited to:

- providing information, support and referrals

- referrals to short-term counselling

- court preparation and accompaniment

- Victim Impact Statements preparation

- liaising with police, courts, Crown and Correctional Services

Police-based victim services

Typically offered shortly after the victim's first contact with the police, they may be housed within police detachments but are often staffed by civilian coordinators or trained volunteers. In many cases, police may refer the victim to a systems-based victim services or advise victim services to make contact with the victim. Services usually include:

- Crisis response and emotional support

- Referrals to other agencies

- Court orientation and information

Court-based victim services

These services assist victims and witnesses directly involved in criminal proceedings. Support typically includes:

- Explaining court processes and roles

- Preparing and accompanying victims for testimony

- Coordinating testimonial aids

- Assisting with Victim Impact Statements

- Providing updates on case outcomes

Some court-based victim services are only available for certain clientele such as children or victims of domestic violence.

Community-based victim services

These services operate outside the criminal justice system are typically run by non-governmental or grassroots organizations and may include:

- Sexual assault centres and crisis lines

- Indigenous-led and culturally specific supports

- Survivor advocacy

- Peer support and counselling

Note on language: This chapter uses ‘victim services’ to refer to court, police or system-based services affiliated with the criminal justice system. We use terms like ‘community-based supports’, ‘sexual assault centres,’ ‘culturally specific supports’ to refer to services delivered outside of those formal structure.

Canada has international obligations

Canada is a party to multiple United Nations Conventions[5] with provisions about preventing victimization and appropriate support services when people experience violence.

Selected International Treaties and Declarations

United Nations Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power (1985)1, particularly Principles 14 and 15, affirms that victims should receive and be informed of medical, psychological, legal, and social assistance.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)2 requires states to protect Indigenous women and children from all forms of violence and discrimination and ensure that Indigenous peoples have access to social and health services to attain the highest standards of physical and mental health.

United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)3 obliges states to eliminate discriminatory practices and ensure appropriate remedies for survivors.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)4 requires states to ensure that support services for victims of violence are available, accessible, and culturally appropriate.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child5 obliges states to protect children from sexual abuse and provide necessary social supports in cases of maltreatment.

1United Nations. (1985). Declaration of basic principles of justice for victims of crime and abuse of power. Adopted by General Assembly, 40/34.

2 United Nations. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. (Articles 7, 22 & 24). Adopted by the General Assembly, 61/295.

3 United Nations. (1979). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (Articles 2 & 5). United Nations Treaty Series, 1249, 13.

4 United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. (Article 16). United Nations Treaty Series, 2515, 3.

5 United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. (Article 19). Adopted by the General Assembly, 44/25.

Canada and Japan are the only G7 countries in which victims of crime do not have a right to be told about the services available to them.[6]

How does the CVBR fit in?

The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights (CVBR) is quasi-constitutional federal legislation guaranteeing victims of crime across Canada the right to ask for information about support services available to them, including restorative justice programs.

- The federal right to information does not currently provide a proactive responsibility on the state to inform victims about support services.

- Provinces and territories in Canada also have victim rights legislation that apply only to their jurisdictions, and some provide proactive rights to information about victim services.

- For example, s. 3 (1)(b) of the Nova Scotia Victims Rights and Services Act says that a victim has the right to access: “…social, legal, medical and mental health services that are responsive to the needs of the victim and the needs of the victim’s dependents, spouse or guardian.” [7]

- In 2020, the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime released a five-year progress report on the CVBR and made a clear recommendation to Parliament to amend the law to automatically provide victims of crime with information on their rights.[8] The Ombudsperson also recommended adding a right to access victim assistance or support.[9]

A right to services

In 2020, Former Senator Pierre-Hugues Boisvenu introduced Bill S-265 in the Senate, which proposed a series of amendments to the CVBR, including a right to support and assistance services:

13.1 Every victim has the right to have access to legal, social, medical and psychological services that are suited to their needs and circumstances.

- These proposals align with the expectations set out in articles 14–17 in the UN Declaration on Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power.[10]

A right to access services will always depend on the availability and accessibility of services. Some of these gaps reflect larger structural issues: insufficient funding, fragmented service delivery, jurisdictional challenges, and different standards across Canada which have been documented by many studies and stakeholders.

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) acknowledged that Indigenous women face unique barriers to seeking help, including a lack of culturally appropriate supports and inaccessibility of services.[11] Call to Action 40 urges governments to work with Indigenous peoples to establish adequately funded and accessible Indigenous-specific victim programs and services, with appropriate evaluation mechanisms.

- The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG)[12] calls for governments to eliminate jurisdictional gaps and neglect that result in denied or improperly regulated services, particularly for Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people (Call for Justice 1.6).[13]

- Canada’s National Action Plan (NAP) to End Gender-Based Violence aims to address many of these challenges by strengthening support for survivors and their families, investing in prevention, building a more responsive justice system, implementing Indigenous-led approaches, and enabling the “social infrastructure” to support healthy and equitable relationships across society.[14]

- Budget 2022 committed $539.3 million over five years to support provinces and territories in implementing the National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence (NAP).[15] This is a significant investment, but once it is allocated to all provinces and territories to be distributed, there are limits to the level of impact it can have on wait times in front-line services.

- We heard this funding has not consistently been reaching community-based sexual assault centres on the ground and advocates have been calling for these crucial gaps to be filled and for the NAP to be expanded and fully funded for 10 years.[16]

What we heard

It is difficult to measure the demand for services across Canada

Types of services. There are many different types of services for survivors of sexual violence.

- There are services focused on different population groups, such as services for First Nations,[17] Inuit,[18] and Métis[19] people, trans survivors,[20] men,[21] or children.[22]

- There are services specific to types of violence, like sex trafficking[23] or sexual exploitation of children online.[24]

- For survivors living in urban areas, there may be choice in the type of service, but there are fewer options for those in rural or remote areas, and almost nothing in First Nation communities on reserve.

Victim Services Directory (VSD). The development of a national VSD has improved efforts to support access to victim services in Canada.[25] The VSD helps service providers and victims locate services for victims of crime across Canada. Agency information for the VSD is populated by the Policy Centre for Victims Issues in collaboration with victim serving agencies. The VSD includes agencies in all provinces and territories across the country.

Independent sexual assault centres provide crisis support, advocacy, individual counselling, peer support, crisis lines, healthcare, education, independent legal advice, court advocacy programs, and more.[26] There are also legal advocacy programs and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that advance the interests of survivors in policy and law.[27]

- Most provinces and territories have a network of sexual assault services that collaborate nationally through the Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada (ESVA Canada).[28]

- ESVA Canada – getting help. ESVA Canada maintains a detailed resource list of organizations across Canada that serve survivors of sexual violence. It includes information on sexual assault centres, crisis lines, shelters, transition houses, and other supports.[29]

Gaps in data. Given the complex network of organizations working with survivors of sexual violence across Canada, we do not have strong national data on service use. Most services maintain strong client data (often tied to funding requirements), but this information is rarely aggregated across jurisdictions or disaggregated by identity, geography, or other key factors.

- Canadian Victim Services Indicators (CVSI) survey.[30] In 2015, the Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime worked with the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics (CCJCSS) at Statistics Canada to identify data that could be used to measure the impact of the CVBR.

- Phases 2 and 3. The Policy Centre for Victim Issues (PCVI) at Justice Canada funded the next two phases of the project, which included consultations with provincial and territorial representatives to determine what variables should be used and the piloting of a victim services survey. The intent was to map how victims of crime access services throughout the justice system.

- The study concluded that jurisdictional differences in the delivery of victim services make it too difficult to develop standardized measures across Canada.

This highlights a key gap: we still lack national disaggregated data on who accesses support services, who does not, and why. Without this information, it is difficult to ensure that services for victims of crime are responsive, equitable, and effective throughout the continuum of the criminal justice system.

- The significant modernization efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic have increased the use of digital data collection and reporting across government and victim services.

- Modern case management systems and interactive dashboards make it easier to manipulate data and explore different angles. These systems are more adaptable, and the continued evolution of AI-driven technology may increase the possibility of data alignment in the future.

We know the demand for service is increasing

Without clear national data, we need to look at more segmented indicators to understand demand for service. A review of different data sources establishes that there are clear increases in demand for support services linked to greater public awareness following the #MeToo movement[31] and the COVID-19 pandemic, which has created a sustained increase in service delivery.[32]

- A national survey of over 100 sexual violence organizations in 2022–2023 found 83% of agencies saw increased demand compared to pre-pandemic.[33] 80% of sexual violence organizations reported having a waitlist.[34]

- Women in remote areas were 3x more likely to report that there are no local sexual assault centres available.[35]

In our survivor survey, we looked at overall service use and service use grouped by the time period survivors said they last experienced sexual violence.

- Three out of four (n = 969, 75%) survivors accessed support services.

- The most common services accessed were counselling (58%), sexual assault centres (36%), and victim services (33%).

Demand for service has increased. The population of Canada has grown 23% from 33.7 million people in 2007 to 41.5 million in the first quarter of 2025.[36] Over the same time, our survivor survey showed significant increases in the percentage of survivors who accessed services. Demand for

- Counselling services rose from 43% to 69%.

- Victim services rose from 22% to 46%.

- Sexual assault centres rose from 30% to 43%.

The increased demand on sexual assault centres is compounded since they operate many other services as well. The combination of population growth and a higher proportion of survivors seeking help has placed significant demand on services and their employees.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

We saw a corresponding decrease in the number of survivors who said they did not access any formal supports.

(Consult PDF version to see the supporting graph.)

There are barriers to accessing services

“I was not advised of any help, neither victim services, victims’ compensation, counselling supports, or even to have someone discuss the justice process with me (I was 19 when I was raped) – I had no tools or knowledge – just shock.” [37]

The number one barrier to services is information. Without a right to be informed about support services, too many survivors are unaware of what is available.

- “Yes, the information’s on the internet, but it’s hard to find. I don’t think that people know where to start.” [38]

- “I wish the RCMP had a list of supports to give survivors. The responsibility to orient myself and search for help after a traumatic crime has taken so much time and energy. I wish there were more supports for victims to teach us how to build a team and how to ask for help.” [39]

During our investigation, stakeholders and survivors of sexual violence reported these barriers:

- People won’t access services because of fear of being shamed and blamed.[40]

- There are provincial and territorial disparities in services, and a lack of basic services being offered in some rural areas and northern communities.[41]

- Sometimes victims have to travel to reach support services, which can result in transportation barriers.[42]

- Some northern Indigenous communities lack reliable cell service and survivors may need helicopter transport to access a hospital for an exam or sexual assault evidence kit.[43]

- Language barriers are present for two distinct groups of survivors: newcomers who may not speak English or French, and Deaf survivors, particularly those from countries where American Sign Language (ASL) or Langue des signes québécoise (LSQ) are not used

- There is a significant lack of francophone services in rural areas.[44]

A systemic scoping review by Bach et al.[45] found that the “Reasons for underutilizing services are as diverse as the survivors themselves.” The main categories of underserved survivors are:

- Ethnic and cultural minorities

- People with disabilities

- Financial vulnerability

- Sexual and gender minorities

- People with mental health conditions

- People who use criminalized substances

- Older adults

“We know, from our decades of work, the “marginalized of the marginalized” who make up our solidarity networks do not access mainstream anti-violence services”

One of the primary barriers these survivors encountered was insufficient training and awareness among service providers about how to best support them. The review recommended more survivor-centred, culturally appropriate, and trauma-informed services and more attention to survivors belonging in underserved groups in practice.

Stakeholders also flagged the following gaps to us:

- Culturally responsive supports are needed for Indigenous, African, and immigrant communities.[46]

- Greater awareness of how male survivors are affected by sexual violence and better understanding of the needs of men fleeing violent relationships are needed. There is also a need for masculinities-informed programming and male-identifying staff members.[47]

- While there has been an increase in inclusive trauma-informed services for 2SLGBTQI+ people, these services are centred in urban areas.[48]

We also heard about challenges on post-secondary campuses:

- Some campus health, counselling, or sexual violence services would quickly refer the survivors to other services and avoid discussing what happened.[49]

- We also heard about contexts where survivors disclosed sexual assault to authorities and administrators on campus only to find that the perpetrator was better protected than the survivor.

- Survivors are often told that the people who harmed them paid tuition and have a right to be in their classes, even if that means the survivor, who also paid tuition and had a right to be safely in their classes, is unable to attend.

- Some schools took more proactive steps and applied their codes of conduct to ongoing harassing behaviours. There are also contexts where matters were settled with non-disclosure agreements.[50]

- One survivor who was sexually assaulted on campus by another student shared that she had excellent experiences with the university’s sexual assault services. She felt they were responsive to her safety concerns and provided helpful supports, information, and referrals.[51]

Antisemitism and sexual violence on campus

In December 2024, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights released a report, Heightened Antisemitism in Canada and How to Confront It, highlighting the rise in antisemitism felt on university campuses. The Committee heard how sexual violence and misogyny intersect with antisemitism against women. One witness shared their experience as a queer Jew and noted how the campus’ queer club did not feel like a safe space.[52]

- These accounts suggest a need for consistent standards, stronger oversight, and more trauma-informed training across all victim services providers—especially those that serve diverse communities and institutions like universities and colleges.

The GBV workforce in Canada is under-resourced

“Funding for survivor support programs is often short-term and cyclical, creating many challenges both for survivors and those who work in the sector.” [53]

Support services for survivors are struggling to keep up with the increase in demand.

We spoke with more than 500 service providers through interviews, focus groups, and consultation tables. We heard of many service limitations related to resource constraints. These limitations create barriers for survivors:

- Charging for services creates financial barriers.

- Stricter eligibility criteria,[54] such as requiring survivors to report the crime or secure a criminal conviction before accessing certain services, limits access.[55]

- Institutions are often reactive and refuse services until the point of crisis.[56]

- Program availability is limited – not sustained or accessible.[57]

- Victim assistance services can assign a caseworker to a victim in geographic one area, but they may have to start over and be accompanied to trial by another caseworker if they go to court in another area.[58]

The scarcity of services in rural and marginalized communities can lead to overwhelmed service providers and compromised quality.[59]

- Many programs operate with part-time or single staff. This can lead to survivors feeling unsupported, especially early in the reporting process.[60]

- There are often long waitlists,[61] and virtual appointments are necessary.[62] Some services require victims to leave a message and promise to return their call within 72 hours. This poses risks for women in danger or in coercive relationships.[63]

- We heard that the lack of resources makes it difficult to hire and sustain staff and to protect worker wellness. We heard about increased wait times, turning survivors away, and that some services have started charging for their services to offset lapses in funding.[64]

Underfunding of the GBV sector also has a direct impact on the well-being of workers and their families. Research by the Ending Sexual Violation Association Canada (ESVA)[65] found that over half of GBV workers felt emotionally exhausted or burnt out due to their work:

- Over one-third reported that their jobs negatively impact their private lives, and more than 1in 3 reported negative mental health effects from job-related trauma exposure.

- These statistics are disproportionately affecting GBV workers with disabilities.

- Unstable funding leads to low wages and job insecurity, contributing to occupational stress.

- One in four GBV workers and over 1in 3 racialized GBV workers were worried about becoming unemployed.

These conditions jeopardize the availability and quality of services for survivors. The sector lacks stable funding, competitive wages, and longer-term succession planning – all of which are essential to protecting both workers and the people they serve.

Another study on the wellness of victim service providers in Canada highlights care providers’ limitations:

“Our analysis… directly challenges underlying assumptions that women’s caring is boundless, unlimited, and can be taken for granted, that it requires few resources, and that these jobs, whether paid or unpaid, are easy and unskilled. Instead, these workers offered important ways to improve conditions of work and care as they described how they reconcile tensions in their work and live out the contradictions inherent in caring for others in a context that fails to value caring.” [66]

The 2023 Mass Casualty Commission Final Report echoed these concerns, recommending “epidemic-level funding” to end GBV. It urged federal, provincial, and territorial governments to provide stable, long-term core funding for services that have demonstrated effectiveness.

- The Commission emphasized prioritizing funding for community-based, survivor-centred services, especially in marginalized communities, and ensuring that these services are not withdrawn unless proven obsolete or replaced with better alternatives.

Child victims experience inconsistent access to services and information

At the outset, we acknowledge that access to justice for children and youth may also depend on their capacity to report, which could depend on age, ability, having trusted people to report to, or having people adhere to the duty to report.

Whether or not a child has access to justice should not depend on where they live in Canada or on their individual identity. Children are an equity-seeking group similar to other marginalized groups.[67] We heard about several barriers for children and youth survivors of sexual violence:

Barriers in remote and northern communities

Children in rural and remote communities experience increased barriers to support services:

- Resources are sometimes not available or children have to travel great distances

- Circuit courts in remote communities often happen in the local arena and become a community social event

- Children in these communities sometimes have to walk past people they know as they prepare to testify

Intersectional identities impact children’s access to justice

- Children in child protection care experience additional barriers and risk factors related to victimization and criminalization

- Refugees may experience pre-migratory trauma and fear of authority due to past persecution. Their ability to access services in Canada is shaped by their pre-migratory experiences

Unequal access to court supports

There is wide variation in access to testimonial aids across the country.[68]

- Not all courtrooms across the country are equipped with Closed Circuit Television (CCTV)[69] or with resources for other testimonial aids.

- In some rural communities, courthouses do not have a separate room where a child can testify or meet with the Crown. We heard that children are sometimes forced to meet with Crowns or victim service workers in broom closets.[70]

To reduce re-traumatization and support effective truth-seeking, courts need to ensure that survivors of child sexual violence offences are as comfortable and safe as possible when participating in the prosecution process.

Best practices: Child and Youth Advocacy Centres

In 2021–2022, 35 Child Advocacy Centres (CACs) / Child and Youth Advocacy Centres (CYACs) served 10,665 children and youth victims, including 7,436 sexual abuse victims (under 18).[71]

- CYACs are a vital and evidence-informed model that provide coordinated, trauma-informed support to children navigating the CJS.

- Throughout our investigation, stakeholders from different fields have praised the CYAC model and have even recommended it be reproduced for adult sexual assault centres.[72]

- CYACs are not available in Yukon, NWT, Newfoundland and Labrador, PEI.

What CYACs offer

CYACs are safe, child-focused spaces where multidisciplinary teams collaborate to support victims throughout healing and judicial processes. They:

- Reduce the need for children to repeat their story multiple times

- Integrate supports from police, child protection, medical and mental health, and victim services

- Offer child-friendly interview settings and access to trained professionals

- Help children understand what is happening and what to expect

- Provide emotional support to caregivers throughout the process

- Offer wraparound services and reduce re-traumatization[73]

- Advocate for their access to testimonial aids[74]

Sustainability at risk

In 2009, the OFOVC recommended that the federal government, in partnership with provinces and territories, develop a national strategy to expand the network of Child Advocacy Centre models across the country.[75]

- The following year, Budget 2010[76] announced support for the creation and development of CACs.

- While the model has proven to be successful, 15 years later, we’ve reached a point where CYACs are at risk.

Stakeholders have raised concerns that federal funding for CYACs might come to an end.

- Currently, some provinces do not have the resources or infrastructure to sustain CYACs independently.

- The multidisciplinary nature of CYACs creates ambiguity about which provincial or territorial ministry should be responsible for long-term funding.

- A stakeholder in British Columbia emphasized that a lack of clear jurisdictional responsibility can undermine sustainability, even where strong community support exists.

Opportunity for federal leadership

Federal investment in CYACs signals national leadership in child protection, supports provinces and territories in upholding obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and encourages equitable access to child-centred services across jurisdictions.

- In 2017, the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs recommended that the Minister of Justice work with provinces and territories to explore funding proposals to expand the CYAC model of integrated services and advocacy to serve other victims of crime, including adults.[77]

- Some stakeholders suggested that shared funding models, such as the NAP, offer a practical solution.

Survivors and stakeholders support integrated models and wraparound services

“I believe that wrap around support is necessary for survivors to navigate the system. I have seen that done successfully and have seen many times when it doesn't occur, and the difference is outstanding.” [78]

What we heard

Survivors and stakeholders repeatedly emphasized the importance of integrated, wraparound services[79] – models that coordinate health, legal, housing, and social supports in one place – because these approaches reduce the burden on survivors, who are often left to navigate complex systems while experiencing trauma.

- Trauma-informed care for healthcare and other services would better support services, including for aftercare and the legal process.[80]

- Police-based victim services should always be connected to sexual assault centres because some survivors may not trust victim services connected to the police.[81]

We heard that integrated service models could include:

- Sexual assault nurses in hospitals or advocates in police stations

- Adult sexual assault centres mirroring the integrated service model offered at child and youth advocacy centres,[82] while maintaining a community-based, feminist approach to service delivery

- Drop-in centres for victims of human trafficking[83]

- Integrated services (specifically for newcomers) that include housing support[84]

Salal’s New Sexual Assault Clinic in Downtown Vancouver[85]

Since it opened in April 2025, Salal offers an integrated wraparound service model to survivors of sexualized violence. Services are open to women, trans, Two-Spirit, nonbinary, and gender-diverse people. They offer a 24-hour crisis and info line, hospital accompaniment, police and court accompaniment, victim services, counselling and Indigenous counselling, MMIWG2S family counselling, education, and training.[86] The centre expanded Salal’s services to also include:

- A police reporting room that meets the requirements for interview rooms at a police station.[87]

- A room for virtual testimony to allow survivors to testify in court proceedings from the centre.[88]

- On-site medical services, including head-to-toe exams, assessment for drug- or alcohol-facilitated sexual violence, STEP prevention options and screening, reproductive justice options, forensic examinations, evidence collection and storage, emotional support, and referrals. Their existing hospital support program will also continue.[89]

Increase funding and standards

Other recommendations we heard included:

- Increase funding that is not project-based and easier to access for organizations because these organizations are lifelines for some survivors.[90]

- Community-based services need to be adequately funded whether survivors report or not.[91]

- Federal/provincial/territorial standards must be created to ensure victims have access to the same rights and standards regardless of where they live.[92]

- 24/7 access to victim services[93] with reduced wait times for services – more workers, lower caseloads.[94]

- Free counselling for survivors.[95]

- Innovative options for remote areas (like access to transportation and mobile trauma-informed units).[96]

- Navigation support. A multilevel Wayfinder is needed to support survivors because information on the system and support services can be hard to find.[97]

- Expansion of culturally sensitive programs. Services should cover as many languages and backgrounds as possible.[98]

These integrated approaches not only reduce gaps in care but also restore control and dignity to survivors by meeting them where they are rather than requiring them to chase help across disconnected systems.

Survivors of sexual violence should always have access to support services that treat them with dignity and respect – regardless of sex, gender identity, race, culture, language preference, age, geographic location, disability, or other characteristics – consistent with the principles of procedural justice. When victims lack support, they may face significant trauma. A lack of support can also impact their decision to engage in the criminal justice process. Survivors may stop pursuing charges or may not testify if they do not have the support they need.[99] To be effective, support services must be culturally responsive, trauma-informed, and meet the survivor’s language needs.

TAKEAWAY

Survivors deserve access to timely, culturally appropriate, and trauma‑informed services - anywhere in Canada.

Endnotes

[1] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #405

[2] Abji, S., Lanthier, S., & Whitmore, E. (2023). National survey of sexual violence organizations and services in Canada: Research findings. Ending Violence Association of Canada.

[3] Abji, S., Lanthier, S., & Whitmore, E. (2023). National survey of sexual violence organizations and services in Canada: Research findings. Ending Violence Association of Canada.

[4] Burczycka, M. (2022). Women’s experiences of victimization in Canada’s remote communities. Statistics Canada.

[5] Heritage, C. (2024, August 15). Reports on United Nations human rights treaties. Canada.ca.

[6] Crime Victims' Rights Act, 18 U.S.C. § 3771 (2004); Victims' Rights and Restitution Act, 34 U.S.C. § 20141 (1990); Victims and Prisoners Act 2024, c. 21; European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2012).; Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA. Official Journal of the European Union, L 315, 57–73.; Italy adopts legislation implementing EU victims rights directive; Directive - 2012/29 - EN - EUR-Lex; Japan: Support for Victims of Crime | English | 法テラス; Basic Act on Crime Victims - English - Japanese Law Translation.

[7] Nova Scotia. (1989). Victims’ Rights and Services Act: An Act to provide rights and services to victims of crime.

[8] OFOVC. (2020). Progress report: The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights.

[9] OFOVC. (2020). Progress report: The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights.

[10] United Nations. (1985). Declaration of basic principles of justice for victims of crime and abuse of power. Adopted by General Assembly, 40/34.

[11] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

[12] National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (Vol. 1a).

[13] See Annex D for the Ontario Native Women’s Association (ONWA) submission to our report and their recommendations.

[14] Women and Gender Equality Canada (2022). National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence.

[15] Women and Gender Equality Canada. (2024). National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence Backgrounder.

[16] Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada. (2025). Statement and Analysis Grid of the National Action Plan’s Gaps around Sexual Violence (Years 1 & 2).

[17] Ontario Native Women’s Association (ONWA). (n.d.). Home- ONWA.

[18] YWCA Agvik Nunavut. (2025). YWCA-AGVIK-Who we are.

[19]Métis Nation of Ontario Victim Services Program. (2025). Victim Services.

[20]Justice Trans. (2025). Justice Trans Resources.

[21] CRIPHASE. (n.d.). Criphase resources.

[22] Canadian Child Abuse Association. (2025). CCAA-Home.

[23] Canadian Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.). Referral Directory.

[24] Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2025). Canadian Centre for Child Protection – Home

[25] Government of Canada, Department of Justice. (2024a, January 12). Department of Justice - Policy Centre for Victims Issues: Contact us.

[26] Vancouver Rape Relief & Women’s Shelter. (2024, August 29). What We do and Who We Serve - Vancouver Rape Relief & Women’s Shelter.

[27] Women’s Legal Education & Action Fund (LEAF). (2021, October 5). Home- Leaf.

[28] Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada. (2025, February 19). National Coordination and Collaboration - Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada. Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada.

[29] Ending Sexual Violence Association of Canada. (2025). Getting Help.

[30] Allen, Mary. (2019). 2016 Canadian victim services indicators: Pilot survey evaluation and recommendations. Department of Justice Canada.

[31] Mancini, M. & Roumeliotis, I. (2020). Sexual assault centres struggle with limited funding as more women come forward to say #MeToo. CBC News.

[32] Abji, S., Lanthier, S., & Whitmore, E. (2023). National survey of sexual violence organizations and services in Canada: Research findings. Ending Violence Association of Canada.

[33] Abji, S., Lanthier, S., & Whitmore, E. (2023). National survey of sexual violence organizations and services in Canada: Research findings. Ending Violence Association of Canada.

[34] Abji, S., Lanthier, S., & Whitmore, E. (2023). National survey of sexual violence organizations and services in Canada: Research findings. Ending Violence Association of Canada.

[35] Burczycka, M. (2022). Women’s experiences of victimization in Canada’s remote communities. Statistics Canada.

[36] Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2025, June 18). Population estimates, quarterly.

[37] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #915

[38] SISSA Consultation Table #8: Black and Racialized BIL

[39] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #222

[40] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #174

[41] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #223

[42] SISSA Consultation Tables #18: Human Trafficking; #28: Women’s NGO/Advocacy Organizations;#14: Victim Services;#22: Independent Sexual Assault Centre Western

[43] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[44] SISSA Consultation Table #27: Independent Sexual Assault Centre

[45] Bach, M.H., Beck Hansen, N., Ahrens, C., Nielsen, C.R., Walshe, C., and M. Hansen. (2021). Underserved survivors of sexual assault: a systematic scoping review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 12(1):1895516.

[46] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #169; SISSA Consultation Table #22: Independent Sexual Assault Centres

[47] SISSA Consultation Table #24: Men and Boys; SISSA Survivor Interview #157

[48] SISSA Written Submission #28

[49] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #569

[50] SISSA Consultation Table #23 Academics.

[51] SISSA Survivor Interview #20

[52] Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. (2024). Heightened Antisemitism in Canada and How to Confront It.

[53] SISSA Survivor Interview #34

[54] SISSA Survivor Interview #34

[55] SISSA Consultation Table #23: Academics

[56] SISSA Survivor Interview #34

[57] Example: forensic nursing programs in SISSA Consultation Table #6: Newcomers; SISSA Consultation Table #22: Independent Sexual Assault Centres Western; Consultation Table #19: Human Trafficking Quebec

[58] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #188

[59] SISSA Consultation Table #13: Legal & Independent Legal Advice

[60] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[61] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[62] SISSA Consultation Table #6: Newcomers

[63] SISSA Consultation Table #19: Human Trafficking Quebec

[64] SISSA Consultation Table #8: Black and Racialized

[65] Ending Violence Association of Canada. (2024). Roadmap to a Stronger Gender-Based Violence Workforce.

[66] Klostermann, J., Bunting, S., Maki, K., & Przednowek, A. (2025). Care containers: the multilayered politics of boundless work in Canada’s victim services sector. Studies in Political Economy, 106(1), 40–57, 51.

[67] SISSA Stakeholder Interview #027

[68] Hurley, P. (2025). The Use of Closed-Circuit Television: The Experiences of Child and Youth Witnesses in Ontario’s West Region. Victims of Crime Research Digest No.8. Department of Justice Canada.

[69] CCTV allows witnesses to provide testimony through a camera and microphone located outside the courtroom, so that they do not have to face the accused. Hurley, P. (2025). The Use of Closed-Circuit Television: The Experiences of Child and Youth Witnesses in Ontario’s West Region. Victims of Crime Research Digest No.8. Department of Justice Canada.

[70] SISSA Stakeholder Submission 30, Sexual Assault Services of Saskatchewan

[71] Stumpf, B. (2024). A portrait of Canadian child advocacy centres and child and youth advocacy centres in 2021-22. Victims of Crime Research Digest No.17. Department of Justice Canada.

[72] SISSA Consultation Table #21, Independent Sexual Assault Centre Maritimes

[73] Grylls, M. & MacDonald, S. (n.d.). Remote testimony at a child advocacy center: Theory and practice. Luna Child and Youth Advocacy Centre.; Luna Child and Youth Advocacy Centre (n.d). Boost. The-Social-Value-of-Boost-CYAC_Infographic.pdf; Boost for Kids. (2003). Annual report 2023.

[74] Grant, M. (2024). Crown wants judge removed from child abuse cases involving youth advocacy centre. CBC News.

[75] Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime. (2009). Every image, every child: Internet-facilitated child sexual abuse in Canada.

[76] Department of Justice Canada. (2014). Federal Victims Strategy and Victims Fund.

[77] Runciman, B., The Honourable & Baker, G., The Honourable. (June 2017). Delaying justice is denying justice: An urgent need to address lengthy court delays in Canada (Final Report). Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

[78] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #361

[79] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #94

[80] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #357

[81] SISSA Survivor Survey, Response #998

[82] SISSA Consultation Table #21: Independent Sexual Assault Centre

[83] SISSA Consultation Table #18: Human Trafficking

[84] SISSA Consultation Table #6: Newcomers

[85] Salal Sexual Assault Centre. (n.d.). Our centre

[86] Salal Sexual Assault Centre. (n.d.). Our centre

[87] New centre opening for survivors of sexual violence. (2024, April 18). [Video]. CBC.

[88] New centre opening for survivors of sexual violence. (2024, April 18). [Video]. CBC.

[89] Svsc, S. (2024, March 7). Salal to launch Vancouver’s first integrated sexual assault medical clinic. Salal Sexual Violence Support Centre.

[90] SISSA Consultation Table #24: Men and Boys

[91] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #138

[92] SISSA Consultation Table #1: Child & Youth

[93] SISSA Consultation Table #17: Law Enforcement

[94] SISSA Stakeholder Survey, Response #202

[95] SISSA Consultation Table #18: Human Trafficking

[96] SISSA Consultation Table #14: Victim Services

[97] SISSA Consultation Table #8: Black and Racialized

[98] SISSA Consultation Table #6: Newcomers

[99] SISSA Consultation Table #28: Women’s NGO/Advocacy Organizations