28th Annual Report to the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada

Letter to the Prime Minister

Dear Prime Minister:

I am pleased to submit to you the Twenty-Eighth Annual Report to the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada, covering the period from April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

This period is overwhelmingly characterized by two themes: the COVID-19 pandemic, and Canada’s confrontation with racism and intolerance. Continuing and recent attention to the horrors of Indian Residential Schools—captured tragically in the finding of children’s remains in unmarked graves—demands that we come to terms with this chapter of profound injustice and racism in Canada’s story.

The targeting of a Muslim family in London, Ontario, underscores that violence and hate continue to terrorize our society. Our country needs deep reflection on who we are and who we want to be. As an important institution in Canada, the Federal Public Service must share in that reflection, and resolve to be better, more just, open, and inclusive.

We must tackle systemic racism and advance the work on diversity and inclusion in our organizations. That is why I released in January the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service. The Call to Action sets clear expectations for leaders at all levels in the Public Service to take concrete steps to achieve a just workplace—one that is truly diverse and inclusive, advanced through training, recruitment, cultural understanding, accommodation, and other workplace practices. I am very grateful to the employee networks and communities for having started us on this path, and being forceful and practical in their advice.

Throughout this period, public servants have continued to work tirelessly to support the Government’s response to the pandemic. While things did not always go smoothly, the Public Service’s contribution to Canada’s management of the pandemic cannot be minimized: procurement of vaccines and personal protective equipment; standing up and delivering economic and social supports; and provision of scientific and technical resources and advice.

Public servants worked equally hard to continue providing non-pandemic services and programs that Canadians rely on and often had to quickly find innovative solutions to ensure seamless delivery.

The sustained and dedicated efforts of public servants across our country and in posts outside of Canada give me a great deal of pride.

We have also begun the work of examining what lessons from the pandemic we want to incorporate into our regular operations. This work represents an opportunity to incorporate different ways of doing things into our institutions—a legacy that will last long after the pandemic.

I am looking forward to the results of this work, as it will represent a lasting contribution to ongoing renewal of the Public Service.

Fully aware that so many Canadians were deeply impacted by the pandemic, countless public servants worked sacrificially to do their part. It has been humbling to lead the Public Service of Canada during this period.

Yours sincerely,

Ian Shugart

Clerk of the Privy Council and

Secretary to the Cabinet

Introduction

Most years are difficult to summarize, as they typically comprise a range of priorities and events both planned and unforeseen. However, perhaps one of the many strange features of this past year is the presence of two very obvious priorities for the Public Service.

One was being called on to support Canadians through the Government’s response to the pandemic. The other was the need to tackle racism within our institution.

These priorities have given rise to both challenges and some uncomfortable truths. Yet both have granted us the ability to open up fundamental conversations on who we are as a Public Service and how we serve. They have the potential to inspire lasting and positive change.

Serving in a time of crisis

This past year saw public servants deliver with resolve the Government’s pandemic response. The development and implementation of a range of economic, social, and health measures required public servants to find innovative ways to deliver quickly in a complex and uncertain environment.

Public servants generally shy away from the spotlight, preferring to quietly deliver on the Government’s agenda. I want to shine light on how public servants were at the front line of managing risk, innovating in real time to deliver supports and services to Canadians during the pandemic.

The response by public servants has been extraordinary:

- Departments and agencies mobilized a whole-of-government and multi-jurisdictional effort to fight the pandemic. This involved understanding the epidemiological characteristics of the virus and how it is transmitted, and providing surge capacity where it was needed most, including testing and contact tracing supports, laboratory processing capabilities, supplies and equipment, and personnel support.

- Departments and agencies quickly designed and implemented programs that delivered billions of dollars in economic supports to Canadians and to businesses, helping them to weather the worst of the financial impacts resulting from the pandemic and laying the foundation for a post-COVID recovery.

- Public servants procured billions of masks, gloves, gowns, medical equipment, therapeutic drugs, testing technologies, and vaccines in the face of unprecedented global competition, in a way that reflected the urgency of the situation at hand, while at the same time respecting the principle of achieving the best value for Canadians.

- Departments and agencies engaged with and supported First Nations, Inuit and Métis leadership and communities in order to enable the solutions that best met local needs.

- Public servants implemented travel restrictions and testing and quarantine measures at Canada’s international borders to mitigate against the risk of virus importation, while still enabling the flows of critical goods and services into our country.

The pandemic response could not have happened without the enabling work of public servants in areas such as IT, finance, human resources, procurement, and administration. These are typically not the first jobs that come to mind when we think about our response, but these efforts have been central to the accomplishments of departments and agencies.

Performance, results, and outcomes during the pandemic will be assessed in days to come. Indeed, the Auditor General has recently undertaken relevant examinations. There is no doubt that important lessons will be drawn from these studies. What is clear is that the institutions of government proved capable of rapid and targeted response, demonstrated adaptability in delivering results in unaccustomed work arrangements, and showed creativity in adapting often archaic IT systems to urgent and massive demands. Through all this, public servants proved their dedication and commitment to the mission of public service.

Of course, not all parts of government were involved in the pandemic response.

Public servants have remained equally committed to providing exceptional service beyond directly responding to the pandemic and have continued to look for new ways to get results for Canadians. Some examples:

Acting on the shift to virtual connection, the Correctional Service of Canada increased the number of video visitation kiosks across the country by 70% to facilitate more visits. This resulted in a 412% increase in video calls since March 2020.

Despite the obstacles posed by COVID-19, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency quickly updated guidance to allow inspectors and laboratory workers to deliver critical on-site services that protect food safety, animal health, plant health, and market access.

As scientists and researchers continue to respond to the challenges of COVID-19, public servants at Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada supported the Government’s investment in the Stem Cell Network to advance 16 projects from across Canada that will work to address health challenges including type 1 diabetes, cancer, blood disorders, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, and muscular dystrophy.

Public servants at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada are developing a refreshed digital branding program to help farmers and businesses respond to new opportunities opening up around the world as supply chains have shifted and online sales become more widely adopted.

The signing of the Canada-UK Trade Continuity Agreement in December 2020 represents the culmination of efforts by public servants led by Global Affairs Canada to provide Canadian businesses with continuity of access to the United Kingdom market.

Always looking for new frontiers, public servants at the Canadian Space Agency worked on the Gateway Treaty with NASA. This historic agreement confirms Canada’s participation in the planned Lunar Gateway space station and that a Canadian astronaut will be part of the Artemis II mission, the first crewed mission to the Moon since 1972.

As part of the Action Plan for Official Languages – 2018–2023: Investing in Our Future, CBC/Radio-Canada, supported by Canadian Heritage, created Mauril. This new and free platform offers Canadians access to a virtual learning environment featuring CBC/Radio-Canada content to help basic to advanced language learners improve their second official language.

The Government has presented an ambitious agenda for the coming year. In addition to undertaking measures to continue protecting Canadians from COVID-19, public servants will be delivering on a range of items, including:

- implementing the 2021 Budget

- taking action on climate change

- advancing the important work of reconciliation

- significant pieces of legislation

- responding to the opioid epidemic

- increasing community access to broadband Internet

- accelerating action on gender-based violence

In these ways, and more, public servants continue to deliver on the regular business of government.

Looking after health and well-being

At the same time, we must recognize that our accomplishments have come with costs, not least of which is the toll on mental health. Public servants, like all Canadians, have been taking public health measures to slow the spread of the virus, are attempting to juggle family responsibilities, and finding different ways to connect. This has not been easy.

Canadians are depending on public servants to deliver and to do so as simply and efficiently as possible. The pandemic response is often spoken of in terms of a marathon, but for many Canadians, including public servants, the concept of a normal workday or workweek has lost all meaning. They have been continuously sprinting for over a year. Lives have been put on hold. This way of working is not sustainable.

Public servants are as susceptible as anyone else is to mental health issues, stress, and burnout. As a critical institution in our society, the Public Service has to make sure that its employees are supported, so they can effectively serve Canadians.

That is why we must continue to address employee mental health with resources that can be easily accessed on the Mental Health and COVID-19 hub.

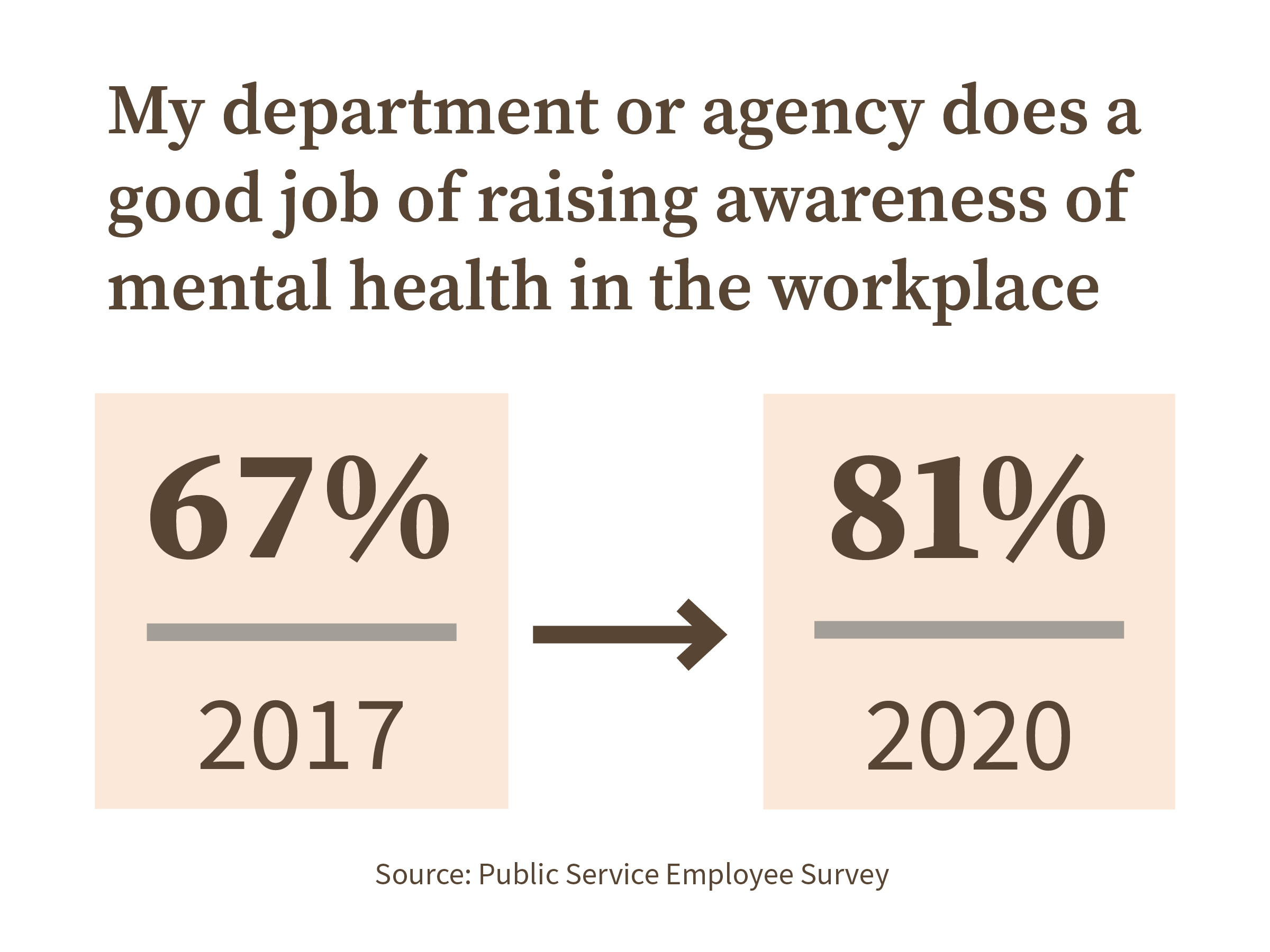

We have seen conversations on mental health shift over the years. It was not that long ago that there was little to no discussion on mental health. We have seen conversations open up and move from a reactive focus on employee mental health supports to proactively looking at prevention and workplace factors influencing psychological health and safety.

The pandemic has underscored the need for connection, for engagement, and for supportive environments. The work of communities within the Public Service deserves recognition. The Federal Youth Network ramped up programming to connect public servants on topics such as mental health and inclusion through their virtual learning series.

Like all Canadians, the ongoing mental health of our employees is going to require sustained attention after the pandemic. There is, unfortunately, no vaccine for the longer-term psychological implications of the pandemic, the full extent of which has yet to be understood.

At the same time, keeping employees physically safe has taken on new meaning during the pandemic. Virtual work capacity has been improved, notably providing IT enabling support. Government-wide guidance, in consultation with bargaining agents, has been provided to organizations. This guidance is used along with consideration of the local public health situation and operational requirements to help organizations determine if and when employees should enter the worksite.

Taking action on racism, diversity, and inclusion

The protests in support of George Floyd across Canada and the world have precipitated deep reflection across our Public Service, and with it, galvanized a need to take action on racism.

The protests further reminded us of our own history in relation to Black people and Indigenous peoples, and the discrimination they continue to face.

We also witnessed very harmful and cowardly displays of increased anti-Asian racism this past year.

These events are stark reminders that despite having made progress to become a more diverse and inclusive society, we have a long way to go. We must make major advances in tackling racism and discrimination and remove barriers to inclusion.

The year under review saw a marked increase in attention, focus and urgency. Racism embedded in our systems and attitudes has been exposed; it is unjust, and it has to stop. It is also clear to ever more public service leaders, at all levels, that discrimination in all its forms, and the harm it causes, will impair the ability of the Public Service to meet Canada’s needs now and in the future. The institution must reflect the country it serves. Efforts were redoubled this year to achieve that dual goal of justice and effectiveness.

Deputy Ministers now have specific performance commitments on diversity and inclusion to make real advancements and measureable change in organizations.

Communities and networks of diverse public servants have been advancing the work of equity and inclusion in our organizations for a considerable time. Their efforts have translated into important recommendations, captured in reports such as Many Voices One Mind: A Pathway to Reconciliation, which are now being implemented by organizations in different ways.

Progress will come in tangible and practical ways. Two examples:

- The Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency is building cultural competency into its hiring practices by developing guidelines for managers on interviewing Inuit candidates. These guidelines call for the inclusion of Inuit panel members and culturally appropriate interview questions, and they encourage questions to be asked in Inuktitut.

- The Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada is creating concerted, system-wide efforts for change. One tangible example is how Shared Services Canada is providing personalized supports for students and other short-term employees across departments and agencies. This Lending Library Service Pilot Project provides access to accommodations, adaptive technology, services and tools for employees with disabilities or injuries so they can quickly get equipped and start putting their talents to work in serving Canadians.

What became clear in the past year is that we need to go farther and faster. Recognizing the need to accelerate efforts, I issued the Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service on January 22, 2021. It sets out expectations for leaders, at all levels, to take concrete steps forward. Its purpose is to speed up work already underway and create momentum for work that is just beginning.

Aimed at increasing representation in our organizations, there are specific calls to recruit, sponsor, and appoint individuals. We also have to look at the work environments we are creating. Every act and every word has the power to create inclusive spaces.

Yet, we know that just because something is within our direct control does not make it easy. Change will require deliberate, sustained attention to undo many of the ingrained practices in our organizations. It is hard, but necessary, work. Discomfort is a necessary accompaniment to progress! There will be emotionally painful conversations. Many public servants, including the most senior leaders, have been entering into that discomfort; after all, far too many employees have been experiencing uncomfortable situations for far too long.

We are hearing that public servants are committed to change. In December 2020, the Human Resources Council issued the Statement of Action Against Systemic Racism, Bias and Discrimination in the Public Service. Heads of human resources pledged to actively promote—through personal actions, decisions, advice, and influence—the achievement of a diverse, inclusive and anti-racist workforce and workplace.

Data has been identified, and embraced, as an essential tool. More disaggregated data is being made available, which helps us further understand where gaps exist. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat released an interactive data visualization tool that creates a better understanding of organizational workforces by providing employment trends and comparative demographics. While a significant amount of data and functionality are already available, ongoing releases will provide further insights on our workforce.

We have existing data pointing to where further action is required. The findings of the Public Service Commission’s Audit of Employment Equity Representation in Recruitment are clear: members of visible minorities, persons with disabilities, and Indigenous peoples do not remain proportionately represented and experience a notable drop-off at various stages of the recruitment process. This Audit is an invaluable tool in pointing the way to the right outcomes.

Our recruitment and promotion processes are based on the merit principle but if we are systematically barring large numbers of people with different backgrounds, identities, and other differences, we are excluding people of merit. Rules, processes, and practices that deny people opportunities because of differences do injury to the merit principle.

We must ensure that everyone has the opportunity to demonstrate their merit. Thinking about these concepts with a new perspective and taking concrete corrective actions must be part of our journey towards equity and inclusion. If we want different outcomes, we need to try different things.

Individual public servants and organizations alike will find themselves at different points along this journey. Some will be closer to the beginning, spending time learning about the realities of different groups and communities. Others will be more knowledgeable and well advanced, looking to share experiences to push us further along.

Spending time really listening and learning from those with experiences different from yours is an important part of the path forward. We would do well to pay attention to those, like the Federal Black Employee Caucus, the Community of Federal Visible Minorities, and the Indigenous Executive Network, who are leading the way.

There are learning resources available. The Canada School of Public Service offers an Anti-Racism Learning Series where public servants can access events, courses, and videos to better understand topics such as anti-Black racism, unconscious bias, and mental health. It is incumbent on each of us to access resources and benefit from the knowledge and wisdom offered.

Communities are sharing valuable information across organizations on practices that can be implemented. The Public Service Pride Network, which promotes inclusion, well-being and community building among LGBTQ2+ public servants, held a series of events from August 24 to 29, 2020, that focused on mental health and well-being.

Organizations are implementing supports that are specific to their context. Anti-racism secretariats are being established across the Public Service, including in departments such as the Department of National Defence; the Department of Justice; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; and Global Affairs Canada who have demonstrated the value of early leadership in this area.

Public servants are also looking for opportunities for system-wide change.

The newly established Centre on Diversity and Inclusion is co-developing initiatives with diverse communities to help improve diversity and inclusion across the Public Service. An early action is the creation of the Mentorship Plus program, which includes a sponsorship component, to support career progression of employees from underrepresented groups.

We cannot lose sight that inclusion extends to combatting linguistic insecurity by creating spaces for our official languages to flourish. While there is an increasing number of tools and supports available, we cannot underestimate the importance of leaders role modelling how they navigate their own insecurity in using their second official language.

Lessons from the pandemic response

As noted, the Public Service responded to the demands of the pandemic with agility and innovation. As we responded to the pandemic, we saw new work models employed. We saw streamlined processes adopted. We embraced the rapid movement of people to priority areas. We looked differently at risk, beyond process to outcomes.

The pandemic has provided insights into the future of how we could work. We can achieve permanent and productive change, if we are determined to identify and exploit those insights.

A big question going forward is which practices will we decide to keep and which will we return to. Like an elastic band, we stretched to support the Government’s response to the pandemic. As the pressure eases, and in time it will, the natural inclination will be to “snap back” to our previous state. That should not happen.

We will want to identify which actions were only relevant in a pandemic situation. Which new approaches we adopted that were better than what was done before. And, we will want to examine the things that we stopped doing and no one noticed.

Fundamental to our considerations will be the role of risk and experimentation. In responding to the pandemic, a strong focus on results led us to be more innovative in design and implementation. There was also an acceptance that we would not get everything right because urgency of response was the priority.

While the future is not yet clear, we do have a good sense of where we are likely to see lasting change. Our business models will be more digital, our workforce more distributed, and the path from idea to delivery shortened. Management practices will need to evolve alongside those changes. The question is one to do with extent.

We have been through an unprecedented period in public administration in Canada because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our institutions and systems of governance and decision-making were tested to the core. If we reflect on this period with an attitude of learning and improving, there are great opportunities to be harvested. But it is complicated.

One of the major features of our decision-making systems is accountability. Fairness, value for money, avoidance of conflict of interest, and other essential principles have to live with timeliness of delivery, relevant outcomes, and innovation. If we can adapt procedures and how we make decisions to enhance all of these considerations, then we will have proven ourselves truly to be a learning institution.

At the end of this reporting period, the pandemic was not over, but the way forward was clear and attainable. Great value can be extracted from this exceptionally difficult time, if we remain focused in the days and years ahead on pursuing reconciliation and justice in our workplaces, innovation and excellence in our service design and delivery, and integrity in our decision-making. I am confident that the professional and capable Public Service of Canada will do just that.

Annex: Key data1

Number of employees2

| Number of employees | March 2019 | March 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| All employees | 287,983 | 300,450 |

| Executives (EX) | 7,070 | 7,376 |

| Associate Deputy Ministers | 45 | 42 |

| Deputy Ministers | 37 | 36 |

Employee types3

| Tenure | March 2019 | March 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indeterminate | 239,645 | 83.2% | 249,973 | 83.2% |

| Term | 31,145 | 10.8% | 33,010 | 11.0% |

| Casual | 8,984 | 3.1% | 8,573 | 2.9% |

| Students | 8,156 | 2.8% | 8,852 | 2.9% |

| Unknown | 53 | 0.0% | 42 | 0.0% |

Age4

Average age of public servants (years)

| Population group | March 2019 | March 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Deputy Ministers | 56.0 | 56.8 |

| Associate Deputy Ministers | 54.4 | 54.8 |

| EX-04 to EX-05 | 53.5 | 53.4 |

| EX-01 to EX-03 | 49.8 | 49.8 |

| Executives (EX) | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Federal Public Service (FPS) | 44.2 | 43.9 |

Age distribution of public servants

| Age band (years) | March 2019 | March 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | 15,661 | 5.4% | 17,195 | 5.7% |

| 25 to 34 | 52,957 | 18.4% | 57,818 | 19.2% |

| 35 to 44 | 79,942 | 27.8% | 82,736 | 27.5% |

| 45 to 54 | 81,730 | 28.4% | 82,927 | 27.6% |

| 55 to 64 | 51,010 | 17.7% | 52,556 | 17.5% |

| 65+ | 6,677 | 2.3% | 7,216 | 2.4% |

| Unknown | 6 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.0% |

Age distribution of new indeterminate hires5

| Age band (years) | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 | 2,596 | 13.5% | 2,821 | 14.6% |

| 25 to 34 | 7,802 | 40.5% | 7,729 | 40.0% |

| 35 to 44 | 4,664 | 24.2% | 4,776 | 24.7% |

| 45 to 54 | 3,034 | 15.8% | 2,819 | 14.6% |

| 55 to 64 | 1,086 | 5.6% | 1,109 | 5.7% |

| 65+ | 60 | 0.3% | 79 | 0.4% |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

Years of experience6

| Years of experience | March 2019 | March 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4 years | 19.5% | 23.3% |

| 5 to 14 years | 38.6% | 36.7% |

| 15 to 24 years | 26.9% | 27.6% |

| 25+ years | 11.8% | 11.0% |

| Unknown | 3.2% | 1.4% |

First official language7

| First official language | March 2019 | March 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| FPS: French | 28.8% | 28.8% |

| FPS: English | 70.3% | 70.1% |

| FPS: Unknown | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| EX: French | 32.7% | 32.9% |

| EX: English | 67.1% | 67.0% |

| EX: Unknown | 0.2% | 0.1% |

Mobility in the core public administration (CPA)

| Mobility in the CPA | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New indeterminate employees | 7,698 | 11,085 | 14,749 | 19,245 | 19,333 |

| Promotions | 11,676 | 15,508 | 18,298 | 22,773 | 24,405 |

| Other internal movements | 15,878 | 14,519 | 16,837 | 18,170 | 19,312 |

| Retirements and departures8 | 9,554 | 9,256 | 8,671 | 8,833 | 9,102 |

Representation (Rep.)9 and Workforce Availability (WFA)10

| 2018-19 | Women | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of visible minorities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | |

| CPA population | 54.8% | 52.7% | 5.1% | 4.0% | 5.2% | 9.0% | 16.7% | 15.3% |

| CPA EX population | 50.2% | 48.0% | 4.1% | 5.1% | 4.6% | 5.3% | 11.1% | 10.6% |

| CPA new hires population | 56.5% | 52.7% | 4.1% | 4.0% | 3.7% | 9.0% | 19.3% | 15.3% |

| FPS population11 | 44.2% | 43.4% | 4.3% | 3.9% | 4.1% | 9.2% | 15.2% | 14.5% |

| 2019-20 | Women | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of visible minorities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | Rep. | WFA | |

| CPA population | 55.0% | 52.7% | 5.1% | 4.0% | 5.2% | 9.0% | 17.8% | 15.3% |

| CPA EX population | 51.1% | 48.0% | 4.1% | 5.1% | 4.7% | 5.3% | 11.5% | 10.6% |

| CPA new hires population | 58.3% | 52.7% | 4.0% | 4.0% | 3.9% | 9.0% | 21.3% | 15.3% |

| FPS population12 | 44.5% | 43.6% | 4.3% | 3.9% | 4.3% | 9.2% | 16.2% | 14.5% |

Disaggregated13 Employment Equity Representation14 and Workforce Availability (WFA)15

| Employment equity group | Employment equity subgroup | CPA population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce availability | March 31, 2019 | March 31, 2020 | ||||

| Number | % | Number | % | |||

| Women | 52.7% | 111,332 | 54.8 | 117,760 | 55.0 | |

| Indigenous peoples | Total indigenous peoples | 4.0% | 10,435 | 5.1 | 10,888 | 5.1 |

| Inuit | 279 | 0.1 | 298 | 0.1 | ||

| Métis | 4,491 | 2.2 | 4,585 | 2.1 | ||

| North American Indian/First Nation | 4,164 | 2.0 | 4,399 | 2.1 | ||

| Other | 1,501 | 0.7 | 1,606 | 0.8 | ||

| Persons with disabilities | Total persons with disabilities16 | 9.0% | 10,622 | 5.2 | 11,087 | 5.2 |

| Coordination or dexterity | 930 | 0.5 | 926 | 0.4 | ||

| Mobility | 1,737 | 0.9 | 1,741 | 0.8 | ||

| Speech impairment | 224 | 0.1 | 235 | 0.1 | ||

| Blind or visual impairment | 767 | 0.4 | 783 | 0.4 | ||

| Deaf or hard of hearing | 1,549 | 0.8 | 1,563 | 0.7 | ||

| Other disability | 6,245 | 3.1 | 6,715 | 3.1 | ||

| Members of visible minorities | Total visible minorities | 15.3% | 34,004 | 16.7 | 38,145 | 17.8 |

| Black | 6,468 | 3.2 | 7,427 | 3.5 | ||

| Non-White Latin American | 1,387 | 0.7 | 1,585 | 0.7 | ||

| Person of mixed origin | 2,568 | 1.3 | 2,999 | 1.4 | ||

| Chinese | 6,042 | 3.0 | 6,505 | 3.0 | ||

| Japanese | 235 | 0.1 | 249 | 0.1 | ||

| Korean | 448 | 0.2 | 535 | 0.2 | ||

| Filipino | 1,231 | 0.6 | 1,410 | 0.7 | ||

| South Asian/East Indian | 5,799 | 2.9 | 6,500 | 3.0 | ||

| Non-White West Asian, North African or Arab | 3,689 | 1.8 | 4,318 | 2.0 | ||

| Southeast Asian | 1,432 | 0.7 | 1,637 | 0.8 | ||

| Other visible minority group | 4,705 | 2.3 | 4,980 | 2.3 | ||

| Employment equity group | Employment equity subgroup | CPA Executive population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce availability | March 31, 2019 | March 31, 2020 | ||||

| Number | % | Number | % | |||

| Women | 48.0% | 2,956 | 50.2 | 3,172 | 51.1 | |

| Indigenous peoples | Total indigenous peoples | 5.1% | 239 | 4.1 | 254 | 4.1 |

| Inuit | * | * | * | * | ||

| Métis | 111 | 1.9 | 117 | 1.9 | ||

| North American Indian/First Nation | 88 | 1.5 | 88 | 1.4 | ||

| Other | * | * | * | * | ||

| Persons with disabilities | Total persons with disabilities17 | 5.3% | 268 | 4.6 | 291 | 4.7 |

| Coordination or dexterity | 23 | 0.4 | 24 | 0.4 | ||

| Mobility | 25 | 0.4 | 28 | 0.5 | ||

| Speech impairment | * | * | 6 | 0.1 | ||

| Blind or visual impairment | 32 | 0.5 | 36 | 0.6 | ||

| Deaf or hard of hearing | 60 | 1.0 | 63 | 1.0 | ||

| Other disability | 133 | 2.3 | 147 | 2.4 | ||

| Members of visible minorities | Total visible minorities | 10.6% | 656 | 11.1 | 714 | 11.5 |

| Black | 96 | 1.6 | 99 | 1.6 | ||

| Non-White Latin American | 18 | 0.3 | 21 | 0.3 | ||

| Person of mixed origin | 84 | 1.4 | 87 | 1.4 | ||

| Chinese | 89 | 1.5 | 97 | 1.6 | ||

| Japanese | 6 | 0.1 | * | * | ||

| Korean | 9 | 0.2 | * | * | ||

| Filipino | 12 | 0.2 | 13 | 0.2 | ||

| South Asian/East Indian | 159 | 2.7 | 174 | 2.8 | ||

| Non-White West Asian, North African or Arab | 100 | 1.7 | 110 | 1.8 | ||

| Southeast Asian | 19 | 0.3 | 23 | 0.4 | ||

| Other visible minority group | 64 | 1.1 | 73 | 1.2 | ||

| * Information for small numbers has been suppressed (counts of 1 to 5). Additionally, to avoid residual disclosure, other data points, may also be suppressed. | ||||||

| Employment equity group | Employment equity subgroup | CPA new hires | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workforce availability | March 31, 2019 | March 31, 2020 | ||||

| Number | % | Number | % | |||

| Women | 52.7% | 13,181 | 56.5 | 14,505 | 58.3 | |

| Indigenous peoples | Total indigenous peoples | 4.0% | 962 | 4.1 | 988 | 4.0 |

| Inuit | 41 | 0.2 | 53 | 0.2 | ||

| Métis | 375 | 1.6 | 293 | 1.2 | ||

| North American Indian/First Nation | 361 | 1.5 | 477 | 1.9 | ||

| Other | 185 | 0.8 | 165 | 0.7 | ||

| Persons with disabilities | Total persons with disabilities18 | 9.0% | 866 | 3.7 | 977 | 3.9 |

| Coordination or dexterity | 55 | 0.2 | 49 | 0.2 | ||

| Mobility | 130 | 0.6 | 140 | 0.6 | ||

| Speech impairment | 18 | 0.1 | 20 | 0.1 | ||

| Blind or visual impairment | 46 | 0.2 | 48 | 0.2 | ||

| Deaf or hard of hearing | 96 | 0.4 | 106 | 0.4 | ||

| Other disability | 597 | 2.6 | 708 | 2.8 | ||

| Members of visible minorities | Total visible minorities | 15.3% | 4,510 | 19.3 | 5,302 | 21.3 |

| Black | 1,045 | 4.5 | 1,236 | 5.0 | ||

| Non-White Latin American | 217 | 0.9 | 227 | 0.9 | ||

| Person of mixed origin | 409 | 1.8 | 532 | 2.1 | ||

| Chinese | 553 | 2.4 | 659 | 2.6 | ||

| Japanese | 21 | 0.1 | 20 | 0.1 | ||

| Korean | 67 | 0.3 | 96 | 0.4 | ||

| Filipino | 156 | 0.7 | 203 | 0.8 | ||

| South Asian/East Indian | 732 | 3.1 | 931 | 3.7 | ||

| Non-White West Asian, North African or Arab | 590 | 2.5 | 725 | 2.9 | ||

| Southeast Asian | 191 | 0.8 | 235 | 0.9 | ||

| Other visible minority group | 529 | 2.3 | 438 | 1.8 | ||

View more statistics: Demographic Snapshot of Canada’s Public Service, 2020

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat