Full report: Mobilizing Public Health Action on Climate Change in Canada

Download in PDF format

(6.40 MB 105 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2022-10-25

Cat.: HP2-10E-PDF

ISBN: 1924-7087

Pub.: 220351

Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2022

On this page

- Message from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

- About this report

- Section 1: Climate change: A threat to health, well-being, and our planet

- Climate change as a global problem

- Health in a changing climate: the Canadian context

- From climate hazards to health impacts: The health risks of climate change in Canada

- Vulnerability and inequitable health risk

- Bringing public health and climate action together to address the threat

- Current public health action in a changing climate

- Section 2: Opportunities to advance climate action in public health

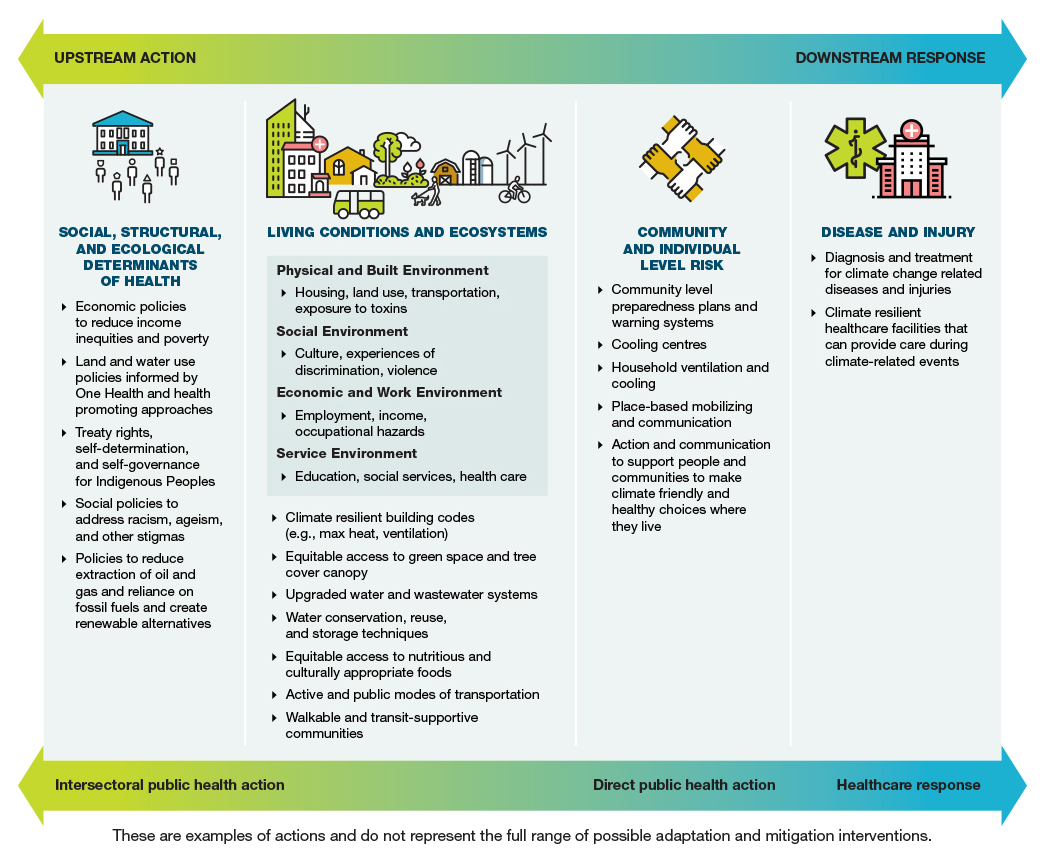

- Implement a range of interventions to address immediate health challenges and prevent future health risks from a changing climate

- Prioritize community expertise and engagement for equitable and effective climate action

- Advance knowledge to understand, predict, and respond to the health impacts of climate change

- Collaborate across sectors for transformative climate-health action and intersectoral co-benefits

- Strengthen public health leadership for climate action and public health building blocks for climate resilience

- Way forward

- Appendix A: Essential public health functions and public health climate action

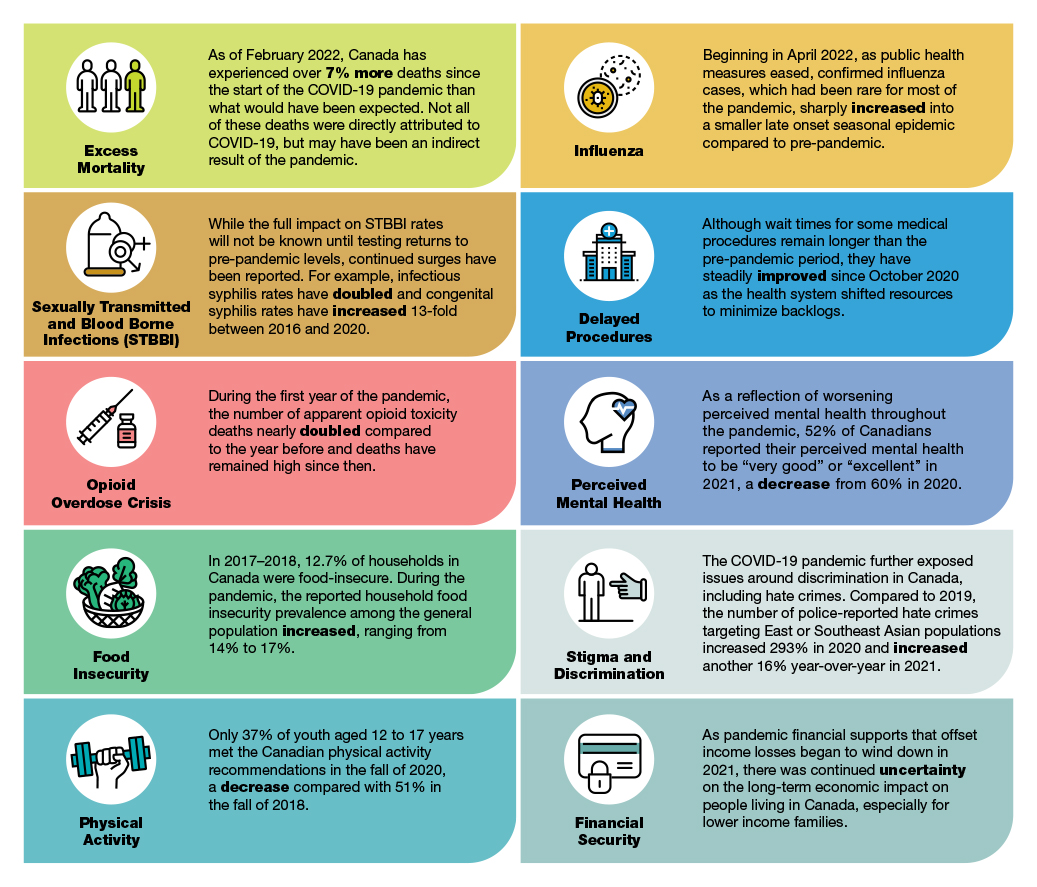

- Appendix B: An update on COVID-19 in Canada

- Appendix C: Methodology

- Acknowledgements

- References

Message from the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

Dr. Theresa Tam

Over the past 2 and a half years, we have been challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic. Through our collective response as a society, we have made tremendous progress across Canada, averting many infections and saving many lives. And while we must continue to evolve our management of COVID-19 and its longer-term impacts, we must also turn our attention to other health threats. This includes what is arguably the largest looming threat to the health of our communities and our planet: the climate crisis.

Climate change is making weather patterns more unpredictable and causing more frequent and intense extreme weather events, like heatwaves, hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires. It also threatens the availability and safety of our water and food.

The changing climate is already having a measurable impact on our health, both physically and mentally. For example, it is exacerbating the spread of climate-sensitive infectious diseases and worsening chronic conditions due to heat exposure or poor air quality. And whether it is weeks of breathing wildfire smoke, or suffering through record-setting heatwaves, or being unable to reach traditional grounds to hunt for food, no one is immune to the impact of our changing climate. Not all communities are affected equally, however. Like COVID-19, some face greater risk of exposure, are less able to adapt and more vulnerable to serious health outcomes.

This is a pivotal time for public health systems to draw on the lessons learned from the pandemic, show leadership, and work collaboratively with other sectors. We must continue to bring climate considerations into public health work to prepare for, and respond to, the now inevitable health impacts. This means supporting communities to adapt to the climate risks they will face.

But we also need to put health at the centre of climate action and focus on efforts that will lead to significant and near immediate health and environmental benefits. By advocating for healthy environments like walkable neighbourhoods, cycling, and public transit, we can reduce chronic diseases, premature deaths and hospital admissions, promote positive mental well-being and reduce air pollution. By supporting more tree canopies and building retrofits, we can promote and protect health while mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

It is clear, climate action is good for our health and public health systems have a critical role to play.

In last year's report, A Vision to Transform Canada's Public Health System, I raised the alarm that, without immediate attention, Canada's public health systems will not be able to respond to overlapping emergencies or carry out essential core functions that keep communities healthy and safe. Even now, as we continue to contend with COVID-19, monkeypox has emerged as a threat globally.

My 2022 Annual Report lays out a roadmap for the broader public health system in Canada to organize and mobilize around climate-health action. It provides concrete direction on how we can use our existing tools and knowledge, while also expanding them to meet new challenges that will come along with a changing climate.

Climate change will truly test our readiness on all fronts. Our actions now will determine the magnitude of future impacts, how quickly they occur, and the extent to which our communities and future generations are able to recover and thrive.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples have long recognized the interconnected nature of human, animal, and environmental health. This knowledge has been central to Indigenous identity, resilience, and survival and is essential to a healthy and sustainable future for us all. It is time to embrace Indigenous ways of looking at our place in the natural world. We are not separate from our environment. To be healthy, our air, water, land, and ecosystems must also be healthy.

What lies ahead is no small task. But we know climate action works. We have the tools to understand climate change and figure out how to address this complex and growing challenge to our collective health. By acting together now, we have hope.

Dr. Theresa Tam

Canada's Chief Public Health Officer

About this report

Every year, the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada (CPHO) writes a report on the state of public health in Canada to raise the profile of public health issues, stimulate dialogue, and catalyse action. This year's report focuses on the impacts of climate change in Canada and the role that public health systems can play in taking climate action. It builds on the 2021 CPHO Annual Report by presenting the possibilities of what a strengthened and resilient public health system can do in the face of complex and urgent public health challenges.

The following key concepts are central to the report.

- Adaptation

- The process of modifying our decisions, activities, and ways of thinking to be proactive and better prepared, as well as reactive and better able to respond to a changing climate and its impacts on health.Footnote 1Footnote 2

- Adaptive capacity

- The ability to adjust to or take protective measures against climate hazards and respond to or cope with the health consequences of climate hazards. Existing social inequities mean not all communities or populations have the knowledge, tools, strategies, or financial resources to implement needed climate change and health adaptation actions.Footnote 1Footnote 3Footnote 4

- Co-benefits

- The positive effects that a policy or measure aimed at one objective might have on other objectives. For example, climate mitigation efforts across energy, infrastructure, agriculture, and transportation sectors can improve population health by way of cleaner air, improved housing standards, healthier diets, and increased physical activity.Footnote 1Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7

- Ecological determinants of health

- The elements of nature that are vital for life on Earth, including food sources, fresh water, oxygen, materials to construct shelters and tools, abundant energy, and reasonably stable global climate with temperatures conducive to human and other life forms. Maintaining the integrity, stability, and equitable distribution of these natural systems is an essential condition for health, survival, and prosperity.Footnote 8Footnote 9

- Intersectoral work

- Collaborative approaches used between groups, including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and relevant stakeholders that have a common goal in addressing a specific issue. In a changing climate, this refers to the actions of many sectors in collaboration, including the health sector, that benefit health and climate change outcomes.Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12

- Maladaptation

- Deliberate adjustments in natural or human systems that increase vulnerability to climatic impacts, resulting in an adaptation that fails in reducing vulnerability and may, instead, increase it.Footnote 13

- Mitigation

- An intervention that aims to reduce the causes of climate change, remove heat-trapping greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, and stabilize their levels.Footnote 1Footnote 2

- One Health

- A collaborative, multi-sectoral, and transdisciplinary approach to achieving optimal health outcomes that recognizes the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment.Footnote 14

- Social determinants of health

- Forces and systems that shape the conditions of people's daily lives (e.g., income, education, employment) and influence their health and well-being outcomes. These include economic, social, and political policies and systems, as well as social norms.Footnote 15Footnote 16

- System resilience

- The capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with a hazardous event, trend, or disturbance. It involves responding in ways that maintain their essential function, identity, and structure, while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation.Footnote 1Footnote 5

- Vulnerability

- The predisposition for health to be adversely affected by climate change. This is shaped by the degree of exposure to climate change hazards, the susceptibility to climate change impacts, and the ability to cope with the health impacts of climate change. In public health, the concept of vulnerability can be highly stigmatizing, so it is important to recognize that climate vulnerability is not a label for communities or populations.Footnote 1Footnote 5Footnote 17

Orientation of the report

Section one describes the urgency of climate change. It provides an overview of how climate change is impacting the health and well-being of people living in Canada. Like COVID-19, these impacts are disproportionate and compounding, with some communities affected more than others. These far-reaching population health impacts offer compelling evidence for why public health systems must prioritize and mobilize around this issue.

Section two offers a roadmap for public health action on climate change. It explores opportunities to build on and expand current public health activities, while strengthening public health systems to address this and other complex public health issues.

The way forward outlines cross-cutting priority areas with tangible ideas for system-level actions.

The COVID-19 appendix gives a brief update on the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada between August 2021 and August 2022.

This report benefits from the leadership and expertise of many contributors. This includes text boxes provided by partners at the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health that illustrate practical examples of public health action.

What We Heard Report: Perspectives on Climate Change and Public Health in Canada is a companion resource that has informed the development of this report. It is a summary of interviews and focus group discussions with university-based researchers, public health practitioners, non-governmental public health organization leaders, municipal-to-federal government public health system employees, community leaders, and medical practitioners. These experts' voices are woven through the CPHO report.

An additional way in which the report can be actioned is through generating new knowledge or research. Generating Knowledge to Inform Public Health Action on Climate Change provides a list of research opportunities relating to the report to help guide researchers, funders, and others wishing to mobilize research and knowledge.

Land acknowledgement

We respectfully acknowledge that the lands on which we developed this report are the homelands of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples. Specifically, this report was developed in the following cities:

- In Ottawa, also known as Adawe, on the traditional and unceded territory of the Algonquin People, members of the Anishinabek Nation Self-Government Agreement.

- In Halifax, also knowns as K'jipuktuk, a part of Mi'kma'ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi'kmaq People. This territory is covered by the "Treaties of Peace and Friendship" which Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) Peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725. The treaties did not deal with surrender of lands and resources but in fact recognized Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) title and established the rules for what was to be an ongoing relationship between nations.

- In Montreal, also known as Tiohti:áke, the traditional and unceded territory of the Kanien'kehà:ka. A place which has long served as a site of meeting and exchange amongst many First Nations including the Kanien'kehá:ka of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, Huron/Wendat, Abenaki, and Anishinaabeg.

- Lastly, in Toronto, also known as Tkaronto, the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse urban First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples. Toronto is within the lands protected by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes.

We recognize that there is much more work ahead to address the harmful impacts of colonialism and racism that continue to generate inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. We remain strongly committed to working collaboratively to advance reconciliation in Canada.

Section 1: Climate change: A threat to health, well-being, and our planet

"When the WHO [World Health Organization] says it's the greatest threat to health in the 21st century, why aren't we taking them at their word? Why aren't we accepting that? If this is the greatest threat to population health in the 21st century, let's start treating it like that."

Our changing climate is a crisis that threatens all aspects of life. The impacts can already be seen in our environment, our economy, and, crucially, our health and well-being.Footnote 5Footnote 18 Climate hazards will continue to emerge over the next 2 decades and beyond, and without significant action, the livability of the planet is at risk.Footnote 19 Climate change influences the core conditions of life, including the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, and the land we live on.Footnote 5Footnote 18Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23 The rapidly changing climate also multiplies existing population health challenges, including the spread of climate sensitive infectious diseases, and exacerbates health inequities.Footnote 5Footnote 18Footnote 24

Without immediate and effective action, climate change poses catastrophic risks for present and future generations. We must act urgently to reduce these risks, as national and international assessments warn that the window to do so is closing.Footnote 5Footnote 25 Reducing heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions is critical to limiting climate change. However, even with the most stringent mitigation efforts to reduce them, the planet will continue to warm over the next few decades because of the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere.Footnote 19 To ensure continued livability of the planet and reduce the harm to our communities, ecosystems, and economies, we must act now and continue to reduce emissions while also working to adapt to the unavoidable current and future impacts.

For public health systems, the urgency of the situation requires assertive and effective action across jurisdictions and sectors to prevent, reduce, and address the health impacts of climate change. It will also require us to detect and monitor health threats and move forward with direct and collaborative action to address them. Through this work, public health can bring its focus on equity, health promotion, and intersectoral partnerships to the collective effort and contribute to climate action in a way that supports and protects health.

Climate change as a global problem

Climate change refers to the long-term shift in the average weather conditions of a region, such as temperature, precipitation, and winds.Footnote 26 It involves changes in average conditions as well as variability, such as extreme weather events.Footnote 27 The unprecedented heatwaves experienced across North America and Europe in the summers of 2021 and 2022, are recent consequences that have affected the day-to-day lives of many people.

These changes are caused by greenhouse gases, a large portion of which are released as a consequence of our heavy reliance on the burning of fossil fuels.Footnote 5Footnote 28Footnote 29 Every year, the combustion of coal, oil, and gas releases billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.Footnote 30 Other major greenhouse gases include methane, nitrous oxide, and chloroflurocarbons, released through fossil fuel production, agriculture, landfills, and the use of fertilizers.Footnote 31 Increasing concentrations of these gases in our atmosphere have resulted in unprecedented rises in average temperatures.Footnote 29 This warming has intensified weather systems, causing extreme heatwaves, wildfires, rising sea levels, floods, and droughts. Global temperatures will reach critical levels soon unless significant steps are taken around the world to drastically reduce our emissions.Footnote 32Footnote 33

As with COVID-19, the impacts of climate change are global, including threats to the necessities of life. Over 800 million people are currently undernourished, while climate change is increasing food insecurity through rising temperatures, changing patterns of precipitation, and more frequent extreme weather events.Footnote 5Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36 Modelling suggests that 529,000 deaths worldwide could occur between 2010 and 2050 due to reductions in food availability and changes in consumption patterns related to climate change.Footnote 5Footnote 37 Even under a negative emissions scenario, which refers to activities which remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, increased deaths will occur.Footnote 5Footnote 37 These changes will aggravate living conditions broadly and the health of people globally.Footnote 35Footnote 38 Further, it is estimated that by 2050, 200 million people a year could need international humanitarian aid as a result of climate change. This is almost twice the number of people who required assistance in 2018 due to floods, storms, and wildfires.Footnote 5Footnote 39

Climate change threatens the livability of our cities and communities. Almost two-thirds of cities with populations of over 5 million are in areas at risk of sea level rise, while almost 40% of the world's population lives within 100 kilometres of a coast.Footnote 40 Without strong and coordinated action, places like New York, Shanghai, Abu Dhabi, Osaka, and Rio de Janeiro could be underwater within our lifetime, displacing millions of people.Footnote 41

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body of the United Nations responsible for advancing knowledge on climate change, regularly assesses the latest science.Footnote 42 Its Sixth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability assesses the impacts of climate change on ecosystems, biodiversity, and human communities at the global and regional levels.Footnote 43 It projects that under all scenarios, health risks will increase this century, causing injury and loss of life, impacting physical and mental health, damaging infrastructure and ecosystems, disrupting health care and other critical services, and threatening livelihoods.Footnote 44

These impacts will not be equally shared. Those who contribute the most to climate change are the least likely to experience its adverse impacts.Footnote 45 Globally, children will bear 88% of the burden of disease from climate change.Footnote 5Footnote 46 Conditions such as poverty and socioeconomic or political marginalization can put women, children, older adults, and other populations at a disadvantage in coping.Footnote 35Footnote 47Footnote 48 For example, children facing poverty are at increased risk during urban floods and droughts, which can contaminate water and lead to diarrhoeal illness.Footnote 35Footnote 49 People living in low- and medium-income countries, the most vulnerable in high-income countries, and Indigenous communities, are already bearing an inequitable and disproportionate share of climate impacts.Footnote 45

Importantly, the IPCC recognizes colonialism as one driver of climate change vulnerability across the globe.Footnote 19 For that reason, international climate action must acknowledge and respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Worldwide, Indigenous Peoples are particularly sensitive to the impacts of climate change because of their close relationships with and dependence on the land, ecosystems, and natural resources.Footnote 50 Through intergenerational and traditional knowledge, Indigenous Peoples were amongst the first to notice changes in our climate and have critical understanding for navigating and adapting to it.Footnote 51 Globally, Indigenous worldviews are gaining prominence, emphasizing the interconnected nature of the land, animals, plants, and people.Footnote 52Footnote 53Footnote 54 Further, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) sets out the right to the "conservation and protection of the environment".Footnote 55Footnote 56Footnote 57Footnote 58 If we are to take strong and sustainable action on climate change at all levels, it must honour Indigenous rights and expertise.

While the situation is urgent, there is still hope. The global response to climate change is increasingly focused on the health impacts. In 2021, over 200 international health journals published editorials about the catastrophic harm to health, and the critical need for action.Footnote 59 At the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), the World Health Organization (WHO) led a parallel conference focused on health, equity, and climate change. Currently, 60 countries have committed to at least one of the initiatives on climate-resilient and low carbon sustainable health systems promoted under the COP26 Health Program.Footnote 60 The upcoming COP27 is expected to convene the global health community and partners to ensure health and equity are at the centre of the conference's climate negotiations.Footnote 61 Findings from a global survey published by the WHO indicate that over 60 countries have either conducted a climate change and health vulnerability assessment or are currently carrying out one. These assessments are crucial to establish an evidence base to understand health risks, evaluate which groups are more vulnerable, identify gaps in current action, and identify effective adaptation measures to support decision-making.Footnote 62

International public health organizations and communities have also been actively working to bring attention to the climate health issue. The International Association of National Public Health Institutes (IANPHI) released a Roadmap for Action on Health and Climate Change at COP26. It highlights existing and potential roles for national public health institutes in climate action and includes commitments for supporting their adaptation and mitigation efforts and policy development.Footnote 45 In 2020, IANPHI created a climate change working group to promote international collaboration between national public health institutes and other stakeholders.Footnote 63

Health in a changing climate: the Canadian context

There is plenty of evidence that climate change is already impacting the health and well-being of people living in Canada.Footnote 5 In June 2021, Western Canada experienced a historic heat dome, which set a Canadian record high temperature of 49.6°C in Lytton, British Columbia and led to 619 heat-related deaths.Footnote 64Footnote 65Footnote 66 A major heatwave in Quebec resulted in 86 deaths in 2018, which was the hottest summer on record in 146 years of meteorological observations in the province.Footnote 5Footnote 67Footnote 68Footnote 69 Further, the area burned by wildfires in Canada has doubled from the 1970s to the 2000s.Footnote 5Footnote 70 In 2021, a record dry spring across the country fueled an early start of wildfire season which ultimately saw 2,500 more active fires recorded than the previous year.Footnote 65 Millions of people in Canada were exposed to wildfire smoke and nearly 50,000 evacuations occurred in British Columbia alone.Footnote 65

In a country with over 243,000 kilometres of coastline populated by about 6.5 million people, rising sea levels pose serious threats to Canada's coastal areas, ecosystems, and communities.Footnote 71 While sea level changes vary significantly by location some regions, such as Atlantic Canada, are expected to exceed the global average.Footnote 5Footnote 72 This poses immediate and long-term risks, including coastal erosion, increased storm surge risk, saltwater intrusion, flooding, and damage to infrastructure, personal property, and transportation.Footnote 65Footnote 71Footnote 72 Additionally, in the North, where temperatures are warming most rapidly, thawing permafrost, changing ice and snow conditions, and shifting wildlife habitat threaten entire ways of life. The range of impacts include culture, infrastructure, livelihoods, food security, and water quality.Footnote 5Footnote 21Footnote 72Footnote 73Footnote 74 Currently, permafrost underlies 40% of Canada's landmass; however, estimates suggest this could decrease by 16% to 20% by 2090.Footnote 75Footnote 76

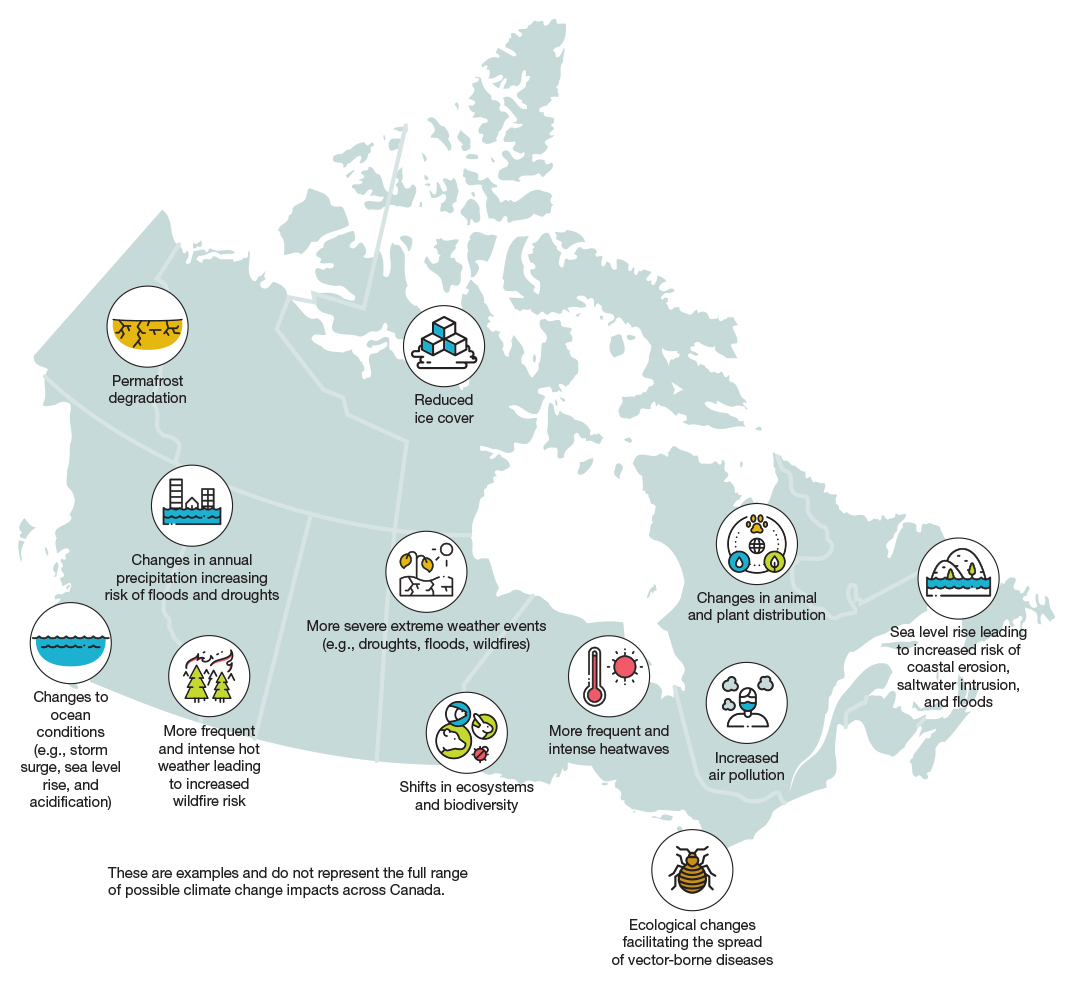

Offshore, the warming and acidification of oceans create irreversible ecosystem shifts that disrupt wildlife populations and food supplies.Footnote 5 Increasing atmospheric temperatures and humidity can worsen air pollution and create favorable conditions that facilitate the spread of vector-borne diseases, such as Lyme disease.Footnote 5Footnote 77Footnote 78Footnote 79Footnote 80Footnote 81 Figure 1 illustrates a few of the wide-ranging climate change impacts experienced across Canada, each of which influences health and well-being. Through interactive maps, videos, and articles, the Climate Atlas of Canada provides further information on projected climate change impacts and how they affect regions differently.Footnote 82 It is important to note, however, that even though many climate hazards are seen regionally, their impact can have far reaching effects.

Source: Figure adapted from Council of Canadian Academies. Canada's Top Climate Change Risks (2019).

Figure 1: Text description

The figure provides examples of climate change impacts, overlaid across a map of Canada. These examples do not represent the full range of possible climate change impacts across Canada.

Western Canada (i.e., British Columbia, Alberta): changes to ocean conditions (e.g., storm surge, sea level rise, and acidification), changes in annual precipitation increasing risk of floods and droughts, and more frequent and intense hot weather leading to increased wildfire risk.

The Prairie Provinces (i.e., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba): more severe extreme weather events (e.g., droughts, floods, wildfires), and shifts in ecosystems and biodiversity.

Central Canada (i.e., Ontario, Quebec): more frequent and intense heatwaves, increased air pollution, and ecological changes facilitating the spread of vector-borne diseases.

Atlantic Canada (i.e., New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador): sea level rise leading to increased risk of coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, and floods.

Northern Canada (i.e., Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut): permafrost degradation, reduced ice cover, and changes in animal and plant distribution.

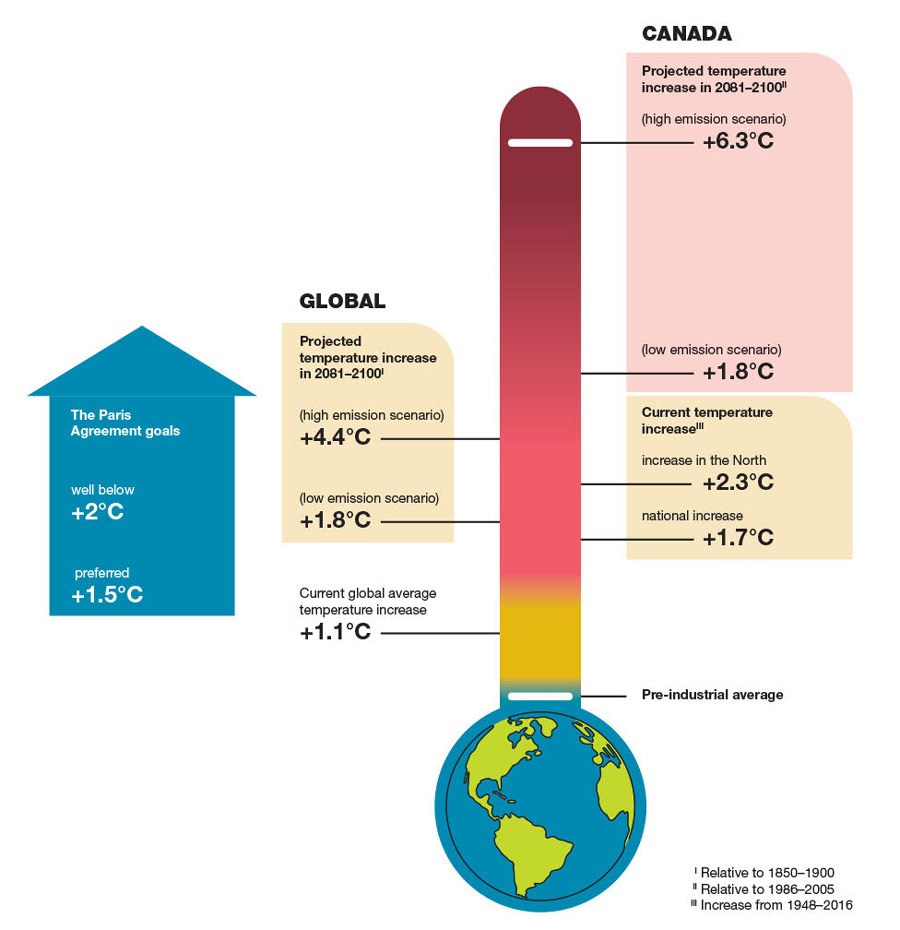

In 2015, Canada ratified the Paris Agreement, along with 195 other countries.Footnote 32 This legally binding treaty sets long-term goals for member states to limit global warming to well below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels, with significant efforts to limit global temperature increases to no more than 1.5°C.Footnote 32 To date, average global temperatures have increased 1.1°C.Footnote 84 If global greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rate, there is a high risk that the world will exceed the 1.5°C target between 2030 and 2052. The current pace of international climate action is too slow. Evidence indicates that global temperatures will exceed the 2°C threshold by the end of this century, unless there are significant and rapid emission reductions across every sector.Footnote 85

Each increment of future warming poses significant risks and increases the probability of compounding impacts to human, animal, and plant health and survival. However, limiting average increases in global temperatures to 1.5°C will reduce the risks of severe climate change outcomes. Exceeding that threshold will lead to numerous preventable illnesses, injuries, and deaths worldwide as a result of disease outbreaks and extreme weather events.Footnote 86 Meanwhile, a 2°C average rise in global temperatures will cause more extreme conditions and dramatic alterations to land, air, and water systems that support survival of all species. The resulting damage will be irreversible in some cases. It is projected that a 2°C increase over pre-industrial levels will regularly expose over one-third of the world's population to health-threatening heatwaves, along with rising sea levels that will increase the risk of flooding for 10 million more people worldwide.Footnote 84Footnote 87

As a whole, Canada is warming at a rate 2 times faster than the global average, while the North is warming 3 to 4 times faster (Figure 2).Footnote 5Footnote 23Footnote 74 Since 1948, average temperatures in this country have increased by 1.7°C, while northern Canada, which encompasses nearly two-thirds of the nation's total landmass, has warmed on average by an alarming 2.3°C.Footnote 23 With a low greenhouse gas emission scenario that is in line with the Paris Agreement, climate models project annual mean temperature will increase in Canada by a further 1.8°C by 2050. In a high heat-trapping greenhouse gas emission scenario, Canada's annual mean temperature will increase by more than 6°C by the end of this century.Footnote 88 The reality is that with even the most stringent greenhouse gas mitigation efforts in place, we are locked into warming patterns for the next few decades because of the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere.Footnote 89Footnote 90 However, the worsening situation in a high emissions scenario will potentially exceed our ability to respond and protect health.

Sources: Government of Canada. Canada's Changing Climate Report (2019). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF) (2021).

Figure 2: Text description

The figure depicts the goals of the Paris Agreement, as well as current and projected temperature increases globally and in Canada by a given year.

The Paris Agreement goals:

- Well below +2 degrees Celsius

- +1.5 degrees Celsius (preferred)

Current global average temperature increase:

- +1.1 degrees Celsius

Global projected temperature increase in 2081-2100 (relative to 1850-1900):

- +4.4 degrees Celsius (high emission scenario)

- +1.8 degrees Celsius (low emission scenario)

Canada's current temperature increase (annual mean temperature increase from 1948-2016):

- +2.3 degrees Celsius in the North

- +1.7 degrees Celsius national increase

Canada's projected temperature increases in 2081-2100 (relative to 1986-2005):

- +6.3 degrees Celsius (high emission scenario)

- +1.8 degrees (low emission scenario)

The health impacts of climate change will become more severe as average annual temperatures increase in the absence of rapidly scaled up adaptations.Footnote 5Footnote 22Footnote 91 These progressive changes also have the potential to limit the effectiveness of available adaptation efforts, making it more difficult to protect the health of the population.Footnote 19 This underscores the importance of international agreements in climate mitigation and adaptation, which can offer significant co-benefits to health. These co-benefits occur when policies aimed at other sectors, such as the environment, also produce positive impacts for health and well-being.Footnote 1 For example, effective mitigation efforts across energy, transportation, building, infrastructure, and agriculture sectors can result in cleaner air, increased levels of physical activity, improved housing standards, healthier diets, lower chronic diseases burden, and lives saved.Footnote 7

From climate hazards to health impacts: The health risks of climate change in Canada

The pathways that connect exposure to climate hazards to health impacts are complex and layered (Figure 3). Vulnerabilities, such as socioeconomic status or geographic location, increase the potential for negative health impacts at individual, community, and population levels.Footnote 5Footnote 43 While some climate hazards, such as severe storms, can result in easily identified negative health outcomes (e.g., injury or death), the health impacts of climate change often do not occur in isolation.Footnote 5Footnote 44 For example, exposure to extreme weather events can cause injury, but may also result in long-term mental health impacts due to displacement, property damage, or loss. Individuals and communities can face multiple and cascading threats at the same time, or compounding impacts over time.Footnote 5Footnote 44 Floods may cause destruction to crucial community infrastructure like power and water supplies, but also lead to food security issues as a result of disruptions or damage to food production processes and systems.Footnote 92 These risks can become more severe if climate threats multiply or repeat. Understanding these pathways, as well as the conditions that create vulnerability, helps identify entry points for public health action and intervention.

Figure 3: Text description

The model describes the impacts of climate change on health. This vertical model works from top to bottom and begins by describing the key drivers of climate change, which influence changes to the Earth's atmosphere and lead to climate impacts. It then describes the pathways from climate hazards to climate sensitive health outcomes.

The key drivers of climate change include a culture of exploitation and belief that nature exists for human use alone, unsustainable economic growth and development, and deforestation and changes in land use.

These drivers influence changes to Earth's atmosphere. Burning of fossil fuels on a mass scale to power homes, vehicles, and agricultural and manufacturing processes leads to the release of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane that trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere. Destruction of carbon sinks (e.g., trees and plants that trap greenhouse gases and keep them out of the atmosphere) leads to Earth losing some of the ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

Changes to the Earth's atmosphere influence climate impacts, such as increases in local, regional, and global temperatures, ocean acidification, and altered weather patterns.

Climate impacts lead to climate hazards, including:

- Extreme weather events: landslides, wildfires, floods, and storms;

- Heat stress: rise in average temperature, extreme hot days, heat waves, and the heat island effect;

- Air quality: rise in air pollutants;

- Infectious diseases: changes in habitat range of vectors and animals, increasing the risk of vector-borne and zoonotic disease;

- Food quality, safety, and security: crop damage from changes in temperature and precipitation, reduced quality or access to traditional foods, and damage to food distribution infrastructure;

- Water quality, safety, and security: water scarcity, contamination of water sources through flooding, and changes in rainfall patterns; and,

- Slow onset climate events: drought, glacial retreat, desertification, and sea level rise.

While specific climate sensitive health outcomes are listed below certain climate hazards, these outcomes can be influenced by a number of different climate hazards, as well as their interconnections.

These pathways ultimately lead to climate sensitive health outcomes, such as:

- Extreme weather events: injury, death, mental health impacts, and limited access to essential supplies and services;

- Heat stress: heat stroke, dehydration, cardiovascular and respiratory impacts, mental health impacts, and pregnancy complications;

- Air quality: exacerbation of respiratory conditions (e.g., asthma), cardiovascular diseases, and allergies;

- Infectious diseases: Lyme disease, West Nile virus, and Hantavirus;

- Food quality, safety, and security: food-borne illness, undernutrition, food insecurity, and cultural and nutritional loss of food;

- Water quality, safety, and security: water-borne diseases caused by parasites or bacteria, and algal blooms; and,

- Slow onset climate events: effects on physical and mental health, increased food and water insecurity, poverty, forced migration, and conflict.

Compounding factors influence vulnerability and increase the potential for negative health outcomes as a result of exposure to climate hazards. These factors include socioeconomic status and other social determinants of health, health and nutritional status, age, and geographic location.

These are examples and do not represent the full range of possible climate hazards or climate sensitive health outcomes.

Climate-resilient health systems that are able to cope with climate change while continuing to deliver essential public health functions are the foundation of an effective response. Resilient public health systems can anticipate, respond, cope, recover from, and adapt to climate-related shocks and stresses.Footnote 5Footnote 93 This goes hand-in-hand with healthcare systems that are more resilient to adverse weather conditions, supply chain disruptions, and service delivery. As the WHO has identified, climate resilience is necessary for health systems to increase their capacity to protect and promote health in an unstable and changing climate.Footnote 94

Climate hazards, exposure pathways, and health impacts

As our climate continues to change, existing health threats will intensify, and new risks will emerge. While we are still learning about the full scope of the health impacts of climate change, existing research has generated important evidence about climate hazards, exposure pathways, and health risks, such as infectious diseases and mental health impacts. This section will summarize key findings on some of the health impacts of climate change.

Exposure to extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and tornados, or natural hazards like wildfires and landslides, pose serious health and safety risks. In addition to the potential for injury, illness, and death, these events can also impact health through isolation, disruption of infrastructure by way of power outages, property damage, evacuations, and associated displacement from homes, jobs, and school.Footnote 5Footnote 72 Extreme weather can also restrict access to food and water supplies.Footnote 72 A major snowstorm in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador in 2020 caused a state of emergency, forcing businesses, including grocery stores, to close for 4 days. This disruption in the regional food supply chain, coupled with high consumer demand, meant many people were unable to purchase basic food staples.Footnote 5

Extreme weather events can also limit or delay vital access to health, social, and community supports and services. Hospitals affected by flooding may need to close emergency rooms, delay medical procedures, evacuate patients, and reduce operational capacity if staff are unable to travel to work. In northern communities, access to medical services can also be compromised by inaccessible roads due to thawing permafrost, flooding, and wildfires.Footnote 95Footnote 96Footnote 97

Heat stress and heat-related health risks are linked to periods of abnormally high temperatures. Extreme heatwaves are already being felt by millions of people each year across Canada.Footnote 64Footnote 98 Direct health impacts linked to heat exposure are extensive and include heat stroke, dehydration, mental health impacts (e.g., mental health-related hospitalizations, suicidality), pregnancy complications, cardiovascular and respiratory disease, and death.Footnote 5Footnote 91Footnote 99 In Ontario, between 1996 and 2010, each 5°C increase in temperature during the summer was associated with a 2.5% increase in death, with a particular link to cardiovascular disease.Footnote 5 The 2010 and 2018 Quebec heatwaves saw increases in daily mortality, emergency room visits, ambulance trips, and hospitalizations.Footnote 67Footnote 68 Other health implications include loss of biodiversity, transmission of diseases, food insecurity, and drought.Footnote 35Footnote 100 Heatwaves and the associated health impacts are projected to become more severe and intense as annual average temperatures continue to rise across the country.Footnote 5Footnote 101

Extreme heat poses amplified risks to many populations, with disproportionate impacts on older adults, children, infants, people with certain pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, people who live or work outdoors, and those with limited financial or social supports to protect themselves from heat.Footnote 102Footnote 103 Many people experiencing homelessness face increased exposure to extreme weather events.Footnote 5Footnote 104 Prolonged exposure to extreme heat can exacerbate pre-existing health conditions and risk behaviours, including mental health, chronic diseases, and substance use.Footnote 5Footnote 104Footnote 105Footnote 106 Additionally, people without safe and consistent housing can experience challenges connecting to heat warning systems, which also provide information on cooling strategies.Footnote 5Footnote 104 People experiencing homelessness may also find it difficult to access drinking water or to keep food from spoiling during extreme heat events.Footnote 5Footnote 104

In Canada, the reality of climate change means that extreme heat events are becoming more frequent and more intense.Footnote 66 Public health research and coroners' reports have indicated that people and groups of people experiencing material and social deprivation are at highest risk, with a clear link between high indoor temperatures and heat-related injury and death.Footnote 66 Specifically, older adults, those who live with disabilities, mental illness, and chronic diseases, and those who do not have access to air conditioning or protection from surrounding green space, are among those most at risk to extreme heat.Footnote 107 There is ongoing work to understand the consequences of extreme heat and the opportunities for climate-health action to address dangerous indoor temperatures (see text box "Evidenced-based policies and the indoor built environment: limiting indoor temperatures to prevent heat-related injuries and deaths").

Evidenced-based policies and the indoor built environment: limiting indoor temperatures to prevent heat-related injuries and deaths

One key step towards climate change resilience will involve setting a national maximum indoor temperature standard. Once this has been set, building codes, building standards, residential tenancy laws, and purposeful urban design can be used to achieve it. At the same time, strengthening social networks and mitigating the risks of social isolation (e.g., performing health checks during extreme heat events) will also be necessary to reduce the number of heat-related injuries and deaths in coming years.Footnote 108

In Canada, we have mandated minimum indoor temperatures to protect health during cold winters; however, there are no maximum indoor temperatures to protect health during hot weather.Footnote 109Footnote 110 There is evidence that exposure to indoor temperatures above 26°C is associated with increases in emergency calls and death.Footnote 107Footnote 111Footnote 112Footnote 113Footnote 114Footnote 115 An upper limit of 26°C indoors has been proposed as sufficient to protect most occupants from heat-related injury and death, including those more susceptible due to age or health conditions.Footnote 107Footnote 111Footnote 112Footnote 113Footnote 114Footnote 115

Keeping buildings cool in a warming climate

Widespread use of central air conditioning is one way to ensure indoor temperatures do not exceed 26°C. However, this also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, strains power supplies during extreme heat events, and creates the potential for mass casualties during a power outage.Footnote 116Footnote 117Footnote 118Footnote 119 A multi-faceted approach is required to promote sustainable healthy indoor temperatures. These approaches must be tailored to different types of housing. Public health can work with the planning, energy, and building sectors to develop systems that protect people without destabilizing the electricity grid or fuelling climate change. Strategies may include localized cooling with heat pumps, as well as non-mechanical options, such as different roofing materials and exterior window shadings, both of which help to reduce the building heat.Footnote 118

New buildings: Indoor temperatures must be specified in building codes

The development of a new climate-resilient national building code is underway and should include a maximum indoor temperature standard.Footnote 120 Changes to the code must ensure that building performance considers human health in the context of other objectives, such as energy efficiency and carbon emissions. Doing otherwise can lead to climate maladaptation, such as airtight buildings that become dangerously overheated during hot weather.Footnote 121

Although changes to the building code are a promising adaptation tool, national and provincial amendments will take time. Municipalities and local governments can act faster through the creation of new standards and building by-laws. Metro Vancouver has already changed its Building By-law to require that all new multi-unit residential buildings have mechanical cooling capable of maintaining an indoor temperature of less than 26°C by 2025.Footnote 114

Existing buildings: Evaluation and retrofitting encouraged through voluntary and regulatory means

The average lifespan of publicly-owned residential buildings in Canada ranges from 40-80 years.Footnote 122 Most of the country's 14 million homes were built for past climatic conditions.Footnote 123 Efforts are needed to evaluate and retrofit existing housing to ensure safe indoor temperatures can be maintained in hot weather. In areas where the baseline climate will remain temperate, it may not be necessary to cool the entire home. One or 2 cool rooms can be adequate to keep occupants safe during heat events and is more feasible.

Assessing individual homes at risk of overheating can be accomplished through low-cost technologies, such as internet-connected thermostats. Programs to incentivize these technologies, combined with public health guidance for extreme heat emergency preparedness, could be used by homeowners, tenants, and landlords to identify environments at risk.Footnote 124

Some voluntary action to reduce heat risk in existing buildings can be incentivized through grants and rebate programs, but these may not benefit the populations most at risk. Regulatory action is likely necessary to address residential overheating equitably. Mandating a maximum indoor temperature in residential tenancy by-laws, as is done for minimum acceptable temperatures, and addressing outdated by-laws and regulations that limit installation of cooling devices in multi-unit residential buildings are two such options.Footnote 125

Thank you to contributing authors:

Dr. Angela Eykelbosh, Environmental Health and Knowledge Translation Scientist and Dr. Leah Rosankrantz, Environmental Health and Knowledge Translation Scientist

National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health

Climate change will increase the level of pollutants and the quantity of pollen in the air. This is expected to exacerbate respiratory diseases, asthma, allergies, and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and death.Footnote 5 Each year in Canada, 15,300 premature deaths and health impacts valued at $114 billion are linked to current levels of air pollution.Footnote 126 The concentration of air pollutants, such as ground-level ozone and fine particulate matter, is expected to increase as climate change increases temperatures and humidity in many parts of the country.Footnote 127Footnote 128 Ground-level ozone, the air pollutant most commonly linked to smog, aggravates the lungs, exacerbates asthma, and increases hospital admissions and premature deaths.Footnote 126

It is estimated that a third of people in Canada have at least one risk factor which increases their susceptibility to the adverse effects of air pollution exposure.Footnote 129 Yet, some face disproportionate health risks related to air pollution and allergens, including older adults, children, pregnant people, Indigenous Peoples, people with pre-existing respiratory and cardiac conditions, people living in households with low income, people living in high air pollution areas, and people who live, work, or are active outdoors.Footnote 130

As a result of climate-driven increases in the frequency and intensity of wildfires, smoke emissions are exposing millions of people to high levels of toxic air pollutants for days and weeks at a time. It is estimated that between 570 and 2,700 premature deaths occur every year in Canada due to long-term exposure to fine particulate matter from wildfire smoke.Footnote 5 In general, the exposure can cause a range of health complications from eye, nose, and throat irritation, to aggravating cardiovascular and lung disease.Footnote 131 People living in areas prone to wildfires may also face an increased risk of developing lung cancer and brain tumours.Footnote 132 However, wildfire smoke can impact air quality over vast distances, possibly affecting the respiratory health of people who live hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away.Footnote 133 In 2018, wildfire smoke originating in British Columbia and Alberta travelled across Canada to affect air quality in Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces, and ultimately reached as far as Ireland.Footnote 134

Increases in temperatures and carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere have shifted the geographic distribution of plants, extending the aeroallergen season in Canada and increasing pollen counts.Footnote 72Footnote 102 Pollens are a major source of allergies, or allergic rhinitis, in North America.Footnote 135

Food quality, safety, and security are essential to health, but are threatened by climate change given the challenges it poses to global and domestic pillars of food systems. Warming temperatures and more frequent high precipitation events can increase occurrences of food-borne pathogens and illness. Droughts and floods can disrupt food supply chains by damaging or diminishing crop yields, reducing the nutritional quality of food, and halting food production processes through associated productivity loss. This can impact food availability, quality, and costs, leading to dietary changes, undernutrition, and food insecurity.Footnote 5Footnote 17Footnote 72Footnote 99Footnote 102Footnote 136

The Prairie provinces are particularly susceptible to these climate change impacts. Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba account for more than 80% of Canada's agricultural land and the majority of the nation's irrigated agriculture.Footnote 137 High temperatures, combined with droughts, floods, and more variable precipitation can negatively affect crop yields across these regions, impacting domestic food supplies. For example, extreme heat can reduce yields of corn, soybean, canola, and wheat.Footnote 137 As the fifth largest exported of agri-food and other seafood in the world, disruptions in Canada's food productions systems could have global consequences.Footnote 138

Climate change may also increase the frequency of chemical contamination of food sources. Flooding and wildfire smoke can carry pollutants onto agricultural land, spoiling or contaminating crops and livestock. Northern communities are particularly at risk, as glacier and sea ice melt can release contaminants that accumulate in food sources, such as fish and mammals.Footnote 5Footnote 36

Indigenous communities that rely on traditional foods are at increased risk of food insecurity, due to significant impacts on food sources as a result of declines in biodiversity and shifting animal migration and population stability.Footnote 139Footnote 140 In northern regions, the rapidly changing environment is altering key species habitat, while melting sea ice is impeding the safe passage of hunters, reducing food accessibility and availability.Footnote 5Footnote 76Footnote 139 Additionally, climate-related declines in marine fisheries are already impacting coastal Indigenous communities that rely on traditionally harvested seafood as an important source of nutrients that are difficult to replace.Footnote 141 This exacerbates the challenges already posed by colonial disruption of Indigenous food systems and loss of access to traditional lands.

Water quality, safety, and security can also be impacted by climate change, as it increases the risk of microorganisms and toxins, which can lead to water-borne diseases.Footnote 17 Heavy precipitation, rapid snowmelts, or sea level rise can reduce the availability of freshwater and damage supply systems, increasing the risk of contaminants in water used for drinking, cooking, bathing, cleaning, and recreational and ceremonial activities.

Communities that already lack access to safe water may feel the effects of climate change more acutely. About 14% of Canada's population, mostly in rural and remote communities, rely on small drinking water systems that serve less than 300 people.Footnote 142 These systems, particularly those in Indigenous communities, are disproportionately affected by water quality and supply challenges. For example, in 2021, 89% of boil water advisories in Canada were for small drinking water systems serving 500 people or less, and as of May 2022, 29 First Nations communities living on reserves were still affected by long-term drinking water advisories.Footnote 143Footnote 144 To mitigate these threats, public health systems can support water system resilience (see text box "Health protection, climate, and small drinking water systems in Canada").

Health protection, climate, and small drinking water systems in Canada

Climate change could exacerbate the inherent challenges associated with small drinking water systems by affecting source water quality, quantity, and water infrastructure.

Source water will become more variable and difficult to treat consistently to an acceptable standard

Changes to precipitation and flooding patterns will cause periodic increases in bacterial and chemical contamination of source water, as well as increased organic matter, which can negatively affect the treatment process.Footnote 145Footnote 146Footnote 147Footnote 148 Increased occurrence of cyanobacterial blooms will increase potential for cyanotoxins in drinking water.Footnote 149 Wildfires will alter watershed hydrology, changing infiltration and runoff. This will affect surface water quality and groundwater recharge.Footnote 150Footnote 151 Sea level rise will worsen saltwater intrusion in island or coastal groundwater.Footnote 148 Drought will reduce groundwater recharge, increase water demand, and cause pollutants to be more concentrated in surface waters.

Water systems infrastructure will be more at risk of contamination and damage

Changing temperature and baseline water quality will affect microbial growth in pipes and storage tanks. Extreme weather events will cause power outages to pumping stations and treatment plants, knocking out supply and treatment capacity. Damage to distribution pipes and storage systems, such as leaks and line breaks from floods or wildfires could cause pressure loss, impairing water delivery and allowing pollutants to enter systems. Wildfires will cause infrastructure damage, destruction, and melting of plastic pipes in distribution systems, causing chemical contamination.Footnote 152Footnote 153 Thawing permafrost will destabilize ground and damage underground pipes and storage tanks, causing contamination of water or infrastructure.Footnote 154

Addressing climate change impacts on small drinking water systems in Canada

Regional, provincial, and federal agencies can help protect health and build water system resilience by encouraging water safety plans to include climate change associated risks to source water and infrastructure.Footnote 155 Agencies can enable better access to water quality data through increased monitoring, surveillance, and tools for sharing data, alongside trend analysis, modelling, and development of water quality forecasting tools and alert systems.Footnote 156

At the community level, strong intersectoral action and training is needed to ensure sufficient emergency prediction, preparedness, and response, including skills in building operations and maintenance.Footnote 157 Support and resources for water quality testing are also needed to assist response to and recovery from extreme events.

Thank you to contributing authors:

Dr. Juliette O'Keeffe, Environmental Health and Knowledge Translation Scientist

National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health

Thawing permafrost, droughts, and flooding caused by climate change will exacerbate and compound the existing health challenges stemming from a lack of access to clean fresh water.Footnote 5 Atlantic Canada is expected to experience the largest local sea level rise, which will lead to increased flooding of homes, businesses, community and marine infrastructure, and pose substantial problems for forestry, fisheries, agriculture, and transportation.Footnote 158 The loss of or damage to homes and belongings means a higher risk of physical exposure to the elements, pathogens, and mold growth, as well as reduced indoor air quality, displacement, and mental health issues.Footnote 158

Climate-related health risks amplify the need to respect water rights, which are essential to health equity and justice. Water rights refer to the inherent right to safe drinking water without discrimination for personal and domestic use, as well as social, economic, and cultural purposes.Footnote 159Footnote 160 The United Nations recognize access to safe water and sanitation as a human right, as the lack of access to it has devastating health effects and impedes the realization of other human rights.Footnote 161

Water rights go beyond safe drinking water and include water sources where people fish for food. Prior to colonization, Indigenous practices guided the use of water. Now, inadequate access to safe and sustainable drinking water increases vulnerability to water-borne disease and exposure to chemical contaminants for some First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities.Footnote 162Footnote 163

Governance gaps make it challenging for Indigenous Peoples to exercise inherent and treaty rights related to water.Footnote 159 Canada's constitutional division of authority over water across different jurisdictions contributes to inconsistent standards for protecting it. Indigenous communities find themselves in a fragmented regulatory system, which increases the challenges related to access to safe drinking water.Footnote 164

The risk of infectious diseases is increasing with a rapidly changing climate. Temperature fluctuations and precipitation changes create expansions and shifts in the geographic range and abundance of climate-sensitive infectious diseases. Moreover, the threat of re-emergence or introduction of zoonotic diseases transmitted between people and animals is exacerbated by climate change, biodiversity and habitat loss, trade, and travel. This elevates the risk of future emerging diseases (see text box "Climate change and the risk for emerging diseases").

Climate change and the risk for emerging diseases

Climate change is affecting life cycles and transmission of viruses and other pathogens because of dramatic changes in weather patterns, water quality, vegetation, population movements, and other environmental factors. Expanded ranges for vectors have contributed to wider dissemination of diseases, such as Lyme disease, and a myriad of mosquito and tick-borne viral pathogens. For example, a 2013 review found a 10 to 50% increase in vector-borne diseases in the northern USA over the median of the preceding 10 years.Footnote 165 The ticks, mice, and mosquitoes that carry pathogens continue to spread into southern Canada.

Climate change's influence on the spread of infectious diseases depends on complex interactions between human behaviour, land utilization, urban planning, vector biology, mitigation strategies, and socioeconomic factors. For example, climate change is leading to certain groups of people, such as displaced or underhoused populations, living in more concentrated situations, such as shelters or community centres, which can facilitate the spread of infectious disease.Footnote 166 Temperature and humidity changes favour viral survival and spread, while shifts in diet may lead to gut microbiome changes that benefit pathogens.Footnote 166 Further, trade and travel can import diseases endemic to other parts of the world.

Climate hazards can also create prime conditions for infectious diseases to spread. For instance, interrupted access to clean water sources and sewage systems damaged by extreme weather events, increase the risk of diarrhoeal and water-borne illnesses.Footnote 167

Thank you to contributing authors:

Dr. Yoav Keynan, Scientific Lead and Margaret Haworth-Brockman, Senior Program Manager

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases

A changing climate also brings risks of new vector-borne diseases as the potential for vectors to establish themselves in new places in Canada grows.Footnote 168 Climate change has already led to greater ranges for ticks and mosquitos, increasing the risk of human exposure to vectors that can transmit diseases, such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus (see text box "Lyme disease and climate change").Footnote 91

Lyme disease and climate change

Tick-borne diseases are increasingly common in parts of Canada due in part to climate and land use change. Since the 1990s, when ticks first arrived in southern Ontario, the Public Health Agency of Canada has been monitoring the movement of tick populations and exposure patterns in people.Footnote 169 Lyme disease is caused bacteria and spread through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. It is one of the most rapidly emerging infectious diseases in Canada, the most commonly-reported vector-borne disease in North America, and incidence has increased more than 17-fold between 2009 and 2019.Footnote 170 In addition to Lyme disease, other tick-borne diseases, such as Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, and Powassan virus, are starting to emerge in Canada and are likely to increase in frequency.

Climate change impacts tick populations through longer, hotter summers and milder winters that promote the ticks' rates of survival, growth, and reproduction.Footnote 171 This means that they can survive and establish populations in areas where they previously could not and increase their numbers where they were already established. Longer summers also mean a prolonged season when ticks are active and people are outdoors, increasing the window of opportunity for the two to physically interact.

Additionally, climate change is expected to expand the range, abundance, and activity of rodent, bird, and deer hosts that carry the disease. These hosts allow the ticks to move through their life cycle and can facilitate tick travel over long distances.Footnote 171

Text partially adapted from the Climate Atlas of Canada.Footnote 169 Learn more about Lyme disease in Canada including prevention measures, symptoms, and risks.

Non-communicable diseases and disability, as well as pre-existing chronic conditions, will also be affected by the changing climate.Footnote 172Footnote 173 Exposure to impacts such as extreme heat, extreme weather events, water-related illnesses, and poor air quality, chronic diseases and disabilities can increase an individual's risk of illness and death.Footnote 5Footnote 174 For instance, older adults with cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, or diabetes are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. The risk factors associated with non-communicable diseases and disability are also affected by climate change. Increasingly, there is recognition that infectious diseases can cause chronic illnesses and that infectious diseases are more severe in those affected by chronic illnesses.Footnote 5 To understand and respond to these health concerns in a time of change we need to strengthen the links between public health efforts.

The relationship between mental well-being and climate change is also complex, as it involves compounding and cascading risks. These can include adverse mental, spiritual, and emotional health impacts from exposure to extreme weather events, emergency evacuations, forced displacement, food and water insecurity, and social and economic disruptions.Footnote 175 Slow-onset climate changes such as increasing temperatures, sea level rise, permafrost thaw, and coastal erosion can impact vital landscapes, cultural practices, and heritage sites, leading to increased mental health challenges, particularly for those deeply connected to the land.Footnote 175 The trauma associated with these events, their impacts, and aftermath can exacerbate existing mental health conditions or bring about new ones. This affects individual mental well-being as well as community social well-being, which is considered an aspect of positive mental health.Footnote 17Footnote 99

"We have, I think, really underestimated the mental health impact of the [climate change] information itself because what we're in essence talking about is a distressing diagnosis that impacts all of us, all of the patients we will ever treat, our family and our friends."

Many people in Canada are already experiencing negative mental health impacts due to current and future impacts of climate change. A survey of 2,000 Canadian adults reported that 49% of respondents were increasingly worried about the effects of climate change, while 25% stated that they often think about climate change and feel "really anxious" about it.Footnote 5 Adverse emotional and behavioural responses, such as worry, grief, anxiety, anger, hopelessness, and fear have been linked to anticipated climate change threats.Footnote 5

Children and youth are particularly vulnerable to climate anxiety, as they will bear the heaviest burden in light of escalating climate threats.Footnote 176 Globally, youth have reported significant distress about the impacts on their daily life, including fear about their future and the future of humanity, lack of government response or urgency, and feelings of betrayal and abandonment by adults.Footnote 176 These feelings can be chronic, long-term, and inescapable, increasing the risk of future mental health conditions in the absence of successful mitigation and adaptation efforts.Footnote 176

At the community level, climate change can disrupt social cohesion and community well-being through deterioration of cultural practices, sense of identity, place attachment, sense of belonging, and intergenerational knowledge sharing and transmission.Footnote 21 These outcomes may be immediate or progressive, burdening future generations and emphasizing the structural and systemic nature of vulnerability.Footnote 177 Climate change is becoming an additional mental health stressor for resource-dependent communities, and in northern regions, such as Nunavut, the disruption of land-based activities, loss of comfort, and cultural identity are negatively impacting mental health and well-being.Footnote 178

Those who have a disproportionate risk of adverse mental well-being impacts from the climate crisis include children, youth, and older adults; Indigenous Peoples; those who have certain pre-existing physical and mental health conditions; as well as low socioeconomic groups and populations facing homelessness.Footnote 179 Additionally, certain occupational groups may also experience disproportionate mental health impacts due to climate change, such as those that rely on weather for livelihoods (e.g., farmers), and work in occupations that respond directly to climate-related emergencies (e.g., firefighters, first responders).Footnote 175

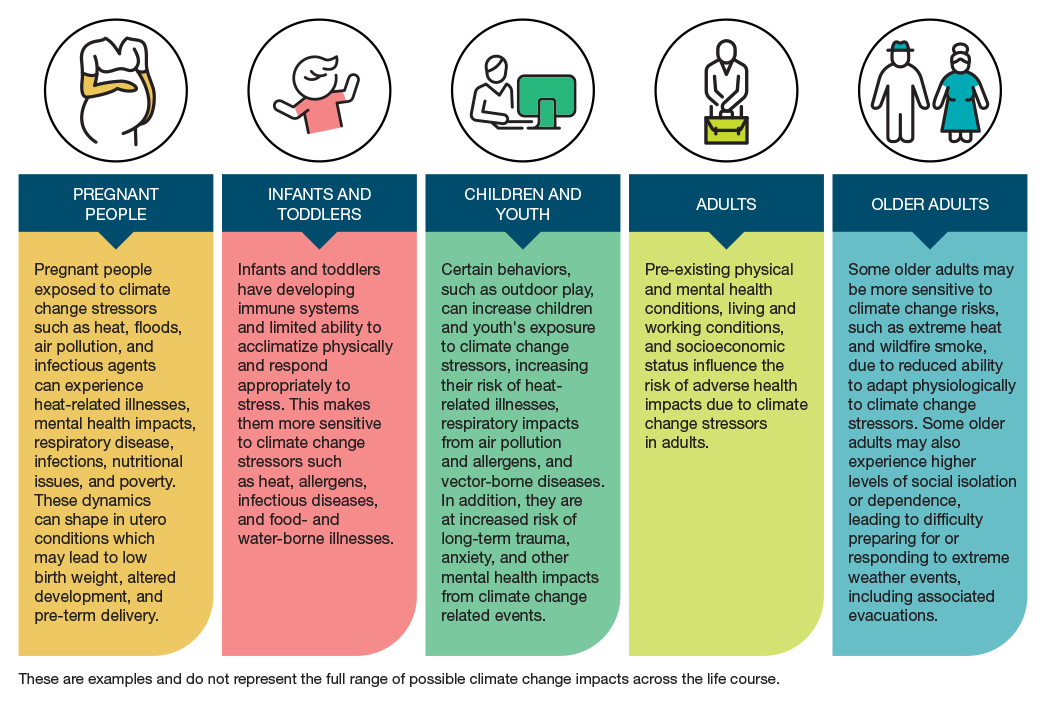

The health risks posed by a changing climate are shaped by a combination of climate hazards, exposure, and adaptive capacity. These hazards and health risks are experienced in different ways, in different places, and by different groups of people. Exposure, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity are influenced by the social, economic, and ecological conditions that determine health at the individual, community, and population levels.Footnote 5Footnote 180Footnote 181 These risks change across the life course (Figure 4).Footnote 5Footnote 17Footnote 176Footnote 182

Figure 4: Text description

The figure describes the health impacts of climate change across the life course.

Pregnant people: pregnant people exposed to climate change stressors such as heat, floods, air pollution and infectious agents can experience heat-related illnesses, mental health impacts, respiratory disease, infections, nutritional issues, and poverty. These dynamics can shape in utero conditions, which may lead to low birth weight, altered development, and pre-term delivery.

Infants and toddlers: infants and toddlers have developing immune systems and limited ability to acclimatize physically and respond appropriately to stress. This makes them more sensitive to climate change stressors such as heat, allergens, infectious diseases, and food- and water-borne illnesses.

Children and youth: certain behaviors, such as outdoor play, can increase children and youth's exposure to climate change stressors, increasing their risk of heat-related illnesses, respiratory impacts from air pollution and allergens, and vector-borne diseases. In addition, they are at increased risk of long-term trauma, anxiety, and mental health impacts from climate change related events.

Adults: pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, living and working conditions, and socioeconomic status influence the risk of adverse health impacts due to climate change stressors in adults.

Older adults: some older adults may be more sensitive to climate change risks, such as extreme heat and wildfire smoke, due to reduced ability to adapt physiologically to climate change stressors. Some older adults may also experience higher levels of social isolation or dependence, leading to difficulty preparing for and responding to extreme weather events, including associated evacuations.

These are examples and do not represent the full range of possible climate change impacts across the life course.

Vulnerability and inequitable health risk

"The poorest, the most vulnerable will be hit harder. So, we have a duty to protect the population, and this is through working on inequities. There are many studies that have shown that the less inequities in societies, the more resilient the population is and less hard it will be hit when a crisis comes."

Understanding the concept of climate change vulnerability is important and requires careful consideration and application in the context of public health. In addition to offering information on increased risks to health outcomes, knowledge about climate change vulnerability can help prioritize where resources and adaptation measures are most needed.Footnote 5

In public health, the concept of vulnerability can be highly stigmatizing.Footnote 5 It is important to recognize that climate vulnerability is not a label for communities or populations. Rather, it occurs when long-standing and systemic patterns of inequity drive differential exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity to climate hazards.Footnote 5 Vulnerability is influenced by factors, such as geography, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, experience of colonization, education, ethnicity, race, disability, income, built environments, as well as living and working conditions.Footnote 183 Collectively, these factors are known as the social determinants of health.Footnote 184Footnote 185Footnote 186Footnote 187 An understanding of these must include structural determinants of health, such as colonization and assimilative policies.Footnote 188 These upstream forces influence policies, programs, and systems that benefit some groups of people over others.Footnote 189

For people who experience gender-based marginalization, there is a higher risk of exposure and sensitivity to climate hazards.Footnote 5 Women may experience increased climate-related anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, while also taking on disproportionate caregiving roles.Footnote 190 Climate change can exacerbate gender-based violence, with increased risk during or after extreme events. In the wake of the 2013 floods in southern Alberta, gendered mental health impacts were observed, including increased anti-anxiety and sleep-aid prescriptions among women, and an increase in sexual assaults.Footnote 191Footnote 192

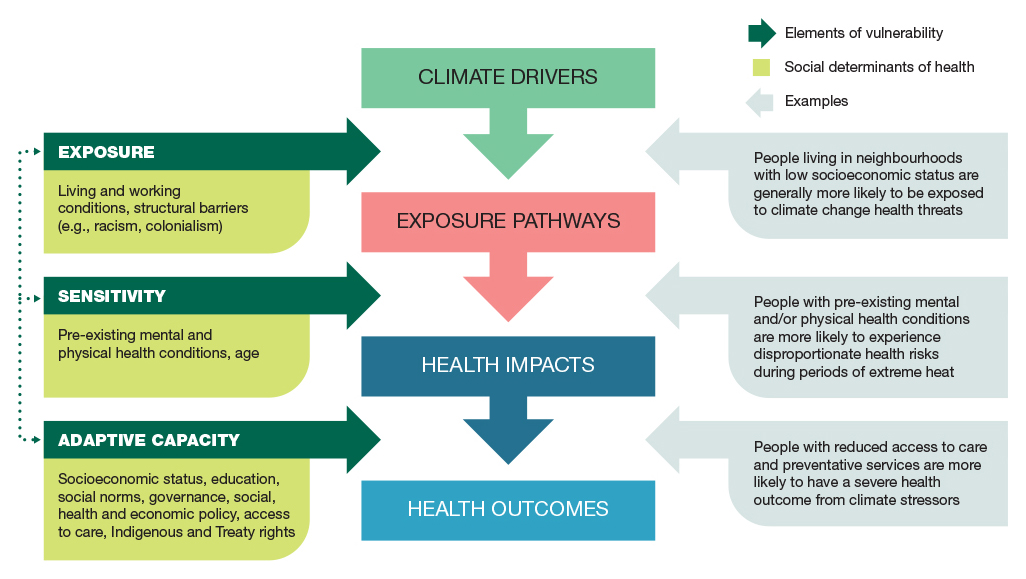

Climate vulnerability is dependent on the degree of exposure to climate hazards, sensitivity to possible impacts, and capacity to adapt. These can be strongly influenced by social and structural conditions (Figure 5).Footnote 5 In the case of coastal flooding, not everyone will experience the same risks and impacts. Housing type and location, access to financial resources to repair damage and pay for expenses associated with temporary or permanent displacement, and the stability of one's livelihood are some of the factors that can influence individual physical and mental health impacts of flooding in a community.

Source: Figure adapted from U.S. Global Change Research Program. The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment (2016).

Figure 5: Text description

The figure depicts a causal chain starting with climate drivers, which influence exposure pathways, which lead to health impacts, and ultimately, health outcomes.

Boxes on the left side provide interconnected examples of social determinants of health associated with each of the elements of vulnerability. These are:

- Exposure (e.g., living and working conditions, structural barriers [e.g., racism, colonialism]);

- Sensitivity (e.g., pre-existing mental and physical health conditions, age); and,

- Adaptive capacity (e.g., socioeconomic status, education, social norms, governance, social, health and economic policy, access to care, Indigenous and Treaty rights).

These elements affect vulnerability at different points in the causal chain from climate drivers to health outcomes (middle boxes). Exposure can influence exposure pathways, sensitivity can influence health impacts, and adaptive capacity can influence health outcomes.

Boxes on the right side provide examples of the implications of the social determinants of health on exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The examples are as follows:

- Exposure pathways (exposure): people living in neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status are generally more likely to be exposed to climate change health threats.

- Health impacts (sensitivity): people with pre-existing mental and/or physical health conditions are more likely to experience disproportionate health risks during periods of extreme heat.

- Health outcomes (adaptive capacity): people with reduced access to care and preventative services are more likely to have a severe health outcome from climate stressors.

Social and economic factors also drive differential access to the material and social resources needed to ease and adapt to the impacts to climate change.Footnote 5Footnote 193 For example, the historic and enduring legacy of colonialism underlies and perpetuates the structural disempowerment of Indigenous Peoples and their health, social, and economic inequity.Footnote 194 Generations of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples have seen land and wildlife destroyed and traditional ways of living degraded by climate change, which has further exacerbated pre-existing health, social, and economic inequities.Footnote 20Footnote 188 This influences the resources available to Indigenous Peoples to respond and adapt to climate risks, such as inadequate community infrastructure, particularly in northern and remote communities.Footnote 20Footnote 91 As noted earlier, climate change disrupts the unique relationship that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples have to the land, which impacts their physical, emotional, spiritual, psychological, and cultural well-being (see text box "Environment: The ecosystem is our health").Footnote 5Footnote 195

Environment: The ecosystem is our health